THE island of Bavia lay fused like some rare pearl in the heart of the golden Java Sea, that stretched away to the trembling horizon, with Ketapang looming out of it like a broken harp. Sea and sky blended together in a golden mist that lay light as thistledown upon an ocean of pathless blue, and everywhere was a suggestion of that golden land where it is always afternoon. And, looking down upon it from the back of the sloping beach, where the great tree-ferns trembled overhead, a man and a woman sat, as they had been sitting the last hour or more. He was young and lean and brown, with the sanguine eyes of youth that is ever seeking something, and not discouraged because so far he has not found it. And the girl by his side was small and dark and exquisitely made, a sort of Spanish Venus, in fact, with the dreamy sleepiness in her eyes that she inherited, perhaps, from some Velasquez ancestress. She was plainly dressed enough, in a linen skirt and jacket, and her luxuriant mass of dusky hair was innocent of any covering; her feet were bare, too, and the skirt of her dress came only a little below her knees, for she and her companion had been paddling in the lagoon at their feet in search of rare anemones, and, anyhow, it was Inez Barrington's mood never to wear shoes if it could possibly be avoided. She was at heart a creature of the fields and the woods, but there was breeding and pride of race in every line of her. She could speak freely enough, if she liked, of those Spanish ancestors of hers, and time had been when she had known the restrictions of school life in San Francisco; but that was before she had come out there to look after her father's house and keep that dreamy widower under some sort of affectionate subjection.

All that had happened five years ago, and in that time she had seen John Barrington's more or less prosperous tobacco plantation drifting into decay, and the army of workers driven away, one by one, till not more than half a dozen of them remained. She had been long enough there to see the hacienda become little better than a creeper-clad ruin, picturesque enough, no doubt, behind its luxurious blaze of blossoms, and still comfortable in a Bohemian sort of way. For, sooth to say, John Barrington was a dreamer and a visionary, and ever a seeker after the will-o'-the-wisp.

The two sitting there, looking out over the lagoon, had been discussing the shiftless Barrington, and, incidentally, the girl's future. There was just a tiny cloud now in those glorious dark eyes of hers, and a droop of the proud scarlet lips.

"Oh, this is a paradise, all right," Frank Preston said—"a paradise where I should be quite prepared to linger on, but for thought of the future. You know, we are all alike, Miss Barrington—all of us ever grasping for the phantom fortune and ignoring the chances that lie at our feet. I am the last man in the world to reproach your father."

The girl laughed gently and turned those velvety eyes upon Preston's face for a moment. There was something in that glance that stirred his heart just a little.

"I know," she said simply, "and sometimes I have meant to speak to you about it. Do you know, I never quite understood why you came here at all, and, for some reason, I have always regarded you as a man of independent fortune."

"Haven't a cent," Preston said lazily. "I am a sort of object-lesson, a kind of idle apprentice. For ten years I have been floating about the world, seeking my fortune, but not very strenuously, I must own. I drifted here through Burma and Siam, looking for the Dawnstar."

"So I have heard you say before," Inez smiled. "Mr. Preston, what precisely is the Dawnstar?"

"I am not altogether sure that such a thing exists," Preston explained. "It's a sort of religion, I believe, like the famous gold mines in the Yukon, or the fabulous diamond that someone is always going to find in South Africa. They talked of it in Siam, under a different name, and they whisper of it in Borneo. It's like those pearls your father is always talking about—the pearls that he firmly believes lie at the bottom of the lagoon at our feet."

"But his late partner found them," Inez said.

"Blind luck," Preston replied—"absolutely blind luck. There! Now listen to me. What right have I to blame your father because he has wasted his life trying to find pearls that don't exist, when I am doing exactly the same thing with regard to the Dawnstar? In our heart of hearts, neither of us believes that there are either pearls or Dawnstars."

"And yet my father's late partner found the pearls here," Inez said. "Not that I believe there are any left. But tell me— what is the Dawnstar?"

"Well, it's a fabulous orchid. Wherever I go in this archipelago, I can always find some superstitious native who has heard of it, or who has heard of somebody who has seen it. No doubt there is some basis to the legend, and I have been fool enough to spend the best part of a year in these parts trying to verify it."

There was a good deal of truth in what Preston said, but it was not the whole truth. He would never have stayed there so long, with the wanderer's virus in his veins, had it not been that he had given his heart to Inez Barrington, and that he was lingering there awaiting events. He perfectly understood how near the dreamy Englishman was to the verge of ruin, and how near he stood on the edge of the grave, and what would become of Inez afterwards was a problem that troubled Preston a great deal more than his search after the elusive Dawnstar. He had come there to investigate the legend, but it seemed to him that he had found something much more precious instead. And gradually his whole mind had become absorbed in Inez's future. He had been there for months, staying in the ruined old hacienda, seeing Inez day by day, studying all the beauties of that open mind of hers, and vainly regretting all his lost opportunities. There were the nights, of course, when he went out looking for the visionary Dawnstar, that was supposed to bloom only in the early hours between dusk and dawn; but so far he had not found it.

He smiled with an air of superior wisdom when he saw Barrington wasting his time and neglecting his property over the brooding hours he spent on the lagoon in search of those mystic pearls, and occasionally he was conscious of a certain contempt for his own weakness. And day by day he could see that the dread consumption that was sapping Barrington's life was advancing nearer and nearer, and the problem of Inez's future troubled him more and more.

"Let us be practical for once," Inez said. "What real good would the Dawnstar do for you if you found it?"

"Well, it would make my fortune, for one thing," Preston said. "It might be worth anything up to a hundred thousand pounds. There are men in England who tbink nothing of paying twenty thousand pounds for a new orchid. If I could get a few Dawnstars and distribute them judiciously, I should be a rich man. And, mind you, the thing actually does exist, because an Indian raja had one. It was destroyed by fire, but the thing undoubtedly was there, because a German collector I once met actually saw it. A lovely thing, Inez. Picture to yourself a plant that blooms in the early dawn or by artificial light, a plant that grows on slender threads no thicker than a cobweb, but strong enough to carry a cloud of blooms that resemble a collection of tropical butterflies. Twenty different blends of gorgeous colouring on one plant, and every separate bloom distinct. It rises in the primrose dusk from a handful of flat leaves, much as the Rose of Sharon blooms before it drops back into nothingness and leaves behind it what appear to be a few dusty, dead leaves. I believe it is an epiphyte—that is, a tree parasite—in other words, it clings to a dead stump. Or possibly it is a tuber. But I don't know. I am only telling you what I have been told. We might even be sitting on it at the present moment. You may laugh at me, if you like, but I believe it is here somewhere, and, if it is, I am going to find it. I wonder if your father has heard of the thing?"

"I think it is exceedingly probable," Inez smiled. "He has never mentioned it, but then he knows I have not much sympathy with those dreams of his. He is full of all sorts of stories of that kind—pearls in the lagoon, buried treasure, and all that sort of thing. I am perfectly convinced that, if my father had lived in the time of Jason, he would have volunteered to go off in search of the Golden Fleece. We will ask him, if you like. I am sure he will be enthusiastic."

They turned their backs on the golden sea presently, and wandered through the tree-ferns to the verandah of the house, where, amongst the bowery blooms that hung like dazzling jewels, they found Barrington, with his coffee and cigarettes, awaiting them. He was a small, slender man, with an eye of a dreamer and the peculiar waxen complexion of one who is far gone in consumption. With his scientific knowledge, it was patent enough to Preston that the end was not far off. For a little time they sat there talking, before Inez introduced the subject of the Dawnstar. Barrington's eyes lighted eagerly as he listened. At the same time his smile was one of toleration for the weakness of another.

"I have heard something about it," he said. "Indeed, I am not so sure I haven't seen the thing. When I go down to the lagoon in the early morning, dredging for those big oysters, I seem to notice certain flowers that are not familiar to me; and, when I come back, they are no longer there. But it is only in one place—as you go down ^ the path by the spring where Inez grows some of those rare ferns she is so fond of. There used to be some trees at the back of the spring, and I believe that the stumps of them are there still. But it's no use asking me. You are only wasting your time, Preston. Now, if you will come with me some night down to the lagoon—"

The dreamer was mounted on his hobby now, and for some time he babbled more or less incoherently of the treasures that lay in the depths of the lagoon, if only it was possible to find them. He told his audience for the fiftieth time how his partner had accidentally come upon a strata of pearl-bearing oysters in the lagoon, where it had been possible to dredge them up, and how that aforesaid partner had returned to England with a fortune in his pocket. But he did not know, or he forgot to say, that for a year or two afterwards every idle native who could command a canoe and a dredge had raked the floor of the lagoon until there was not a single bivalve left. It was all very pathetic and a little ridiculous, but Preston, looking across at that beautiful face opposite him, could see nothing but the tragic side of the situation.

And it did not seem ridiculous to him, as he lay awake that night; to think that Barrington's story had been the means of stirring his own latent hopes. Surely the Dawnstar was there somewhere, if he could only find it. And, if he could, then his problem and the problem of Inez's future would be solved. If he could once come upon the track of the Dawnstar, he would be able to speak the words which had been trembling on his lips for months, and put his fortune to the test. Not that he was afraid of what the answer would be, for Inez's nature was too frank and free to leave him with any illusions on that score. But come what may, and poor as he was, he was not going to turn his back upon the island of Bavia until he knew what was going to happen with regard to the woman whom he loved.

As he lay on his bed, waiting for the dawn, his mind was troubled with many things. He had not been quite candid with Inez when he had spoken to her in that detached way about the Dawnstar. He had not told her, for instance, that the search for that elusive flower was almost as great an obsession with him as the treasures of the lagoon were with John Barrington. He had not told her that he had been following up a legend for years. He had tracked it in various ways and in various languages half through Asia and, by way of Siam, to the island of Borneo. He believed in its existence thoroughly, though he would have been ashamed to admit it. Indeed, a certain deceased German collector had actually seen it.

Therefore, in all the months that Preston had been on Bavia, he had been looking for the Dawnstar night after night. Ever since the first day that he had entered the hacienda and had become a member of that somewhat Bohemian household, he had been out before dawn in the swamps and round the lagoon, always looking for the Dawnstar. And yet he was deeply sorry for Barrington, whom he could not but regard as a fool and a visionary. He was the only man about the place who knew that Barrington spent half his nights in secret visits to the lagoon, where he was wearing out the little strength that remained to him in dredging up oyster shells, and, apparently, never tired of his pursuit. If Barrington had devoted a tithe of his time to his estate, he might by this time be a prosperous man. But the pathetic part of the tragedy lay in the fact that Barrington had no illusions on the matter of his health, and that he was doing all this in the forlorn hope of being able to leave a competence to his only child.

And this was going on night after night; it went on still for weeks after the day when Preston had told Inez the history of the Dawnstar. It went on till one early dawn when Preston was out on his eternal search, and hanging more or less disconsolately around the spring, at the back of the lagoon, from whence the house derived its water supply. It was still dark, with the first suggestion of pallid rose in a morning sky, as Preston wandered down towards the lagoon in the aimless fashion that had become habitual to him—the aimless fashion of a man who begins to despair of his object. As he sat there, with a half-made cigarette between his fingers, Barrington passed him so closely that he could actually have touched him. The elder man was carrying some appliance on his back, and then, as Preston looked at him, he saw that the other was walking in his sleep.

So it had come to that, Preston thought. Barrington was obviously worn out; his face was pale and drawn, and ever and again a hollow cough broke from him. It was bad for him to be out there in the dews of the early morning—fatally bad, no doubt—but he crept along down to his boat like a man in the last stages of exhaustion, a man whose will was evidently stronger than his body. He made his way slowly and laboriously into the middle of the lagoon, and from the bank Preston watched him for some time until suddenly he saw the dark figure collapse and crumble as if it had been an empty sack, and then there followed the sound of a faint splash.

Preston was on his feet in a moment. He plunged headlong into the lagoon and swam out to the floating figure. It was a strenuous fight, but he had Barrington on the sand at length, still breathing, so he gathered the shrunken figure in his arms and carried him towards the house like a child.

His mind was set now only on getting Barrington into bed, so that any thought of the Dawnstar was very far away just then. But as he was passing along the little hollow amongst the tree-ferns at the back of the spring, a solitary flower, all gold and azure, that seemed to be floating invisibly in the air, a foot or two from the ground, caught his attention and held him there for a moment absolutely motionless. Then he turned his face resolutely away and plodded on doggedly in the direction of the hacienda.

He would not think of it. He would not believe anything till he had the burden in his arms safe between a pair of blankets. It must have been some figment of imagination, some phantasm born of the early dawn.

So presently he laid Barrington on his bed and warmed him, and forced brandy between his lips until the sick man opened his eyes and feebly asked what had happened. Preston made him comprehend presently— indeed, told Barrington how he had been watched night by night, whilst the latter listened and nodded before he sat up and grasped Preston by the hand.

"Not a word of this to Inez," he whispered. "I am a fool, perhaps, but then I have always been a fool—ever grasping for the shadow and neglecting the substance. Did you ever know an Irishman who did anything else? But I shall find it—I shall find it before I have done—yes, long before you find that Dawnstar that you were telling me about the other night."

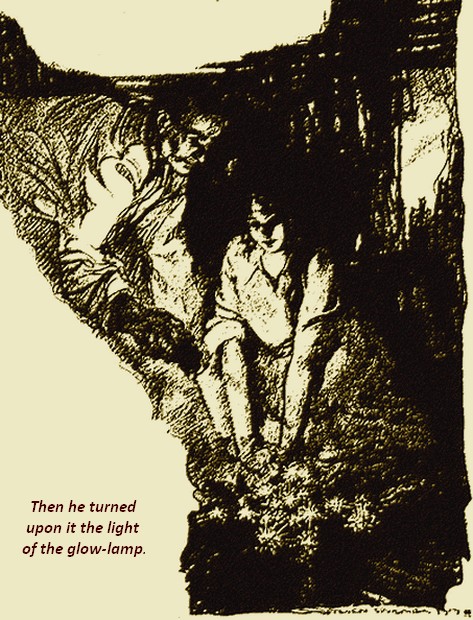

Preston smiled almost bitterly. He knew that hopeful outlook only too well. He crept away presently to his own room, and slept far into the morning. For the rest of the day he seemed rather to avoid Inez. He sat on the verandah in the evening, listening whilst she sang to him, and retired early to bed, but not to sleep. He tossed about from side to side till it seemed to him that the window frame in his bedroom began to stand out sharply against the darkness, and he arose and crept from the house like a thief, and made his way down to the spring. For a long time he sat there watching, as far as possible, the dusky area where he had seen that spirit blossom the night before. He watched until the ebony dusk turned to violet, and the tree-ferns behind him looked like gigantic feathers grotesquely painted on the sombre sky. He watched until his eyes began to ache and water stood in them. Then very slowly and gradually, like an amazing conjuring trick that he had witnessed in some Eastern bazaar, a faint intangible something—a collection of intangible somethings—began to materialise slowly and mysteriously against an opaque purple background.

They came one by one, darting here and there like spirits, intangible, floating in nebulous space, and yet arranged in a sort of symmetrical order, one above the other, like so many painted blooms indented by an unseen hand in a great vase. They were detached, and at the same time formed, part of some harmonious whole, as if a painter had placed them there without supports. And, as Preston watched, he stiffened with an excitement that seemed to paralyse his very breathing.

He could see the colours of the blooms by now—azure, purple, violet, pink, all the hues of the rainbow with their various blends and shades. There must have been five-and-twenty blooms at least, magnificent, glowing, full of life and beauty, and yet apparently living alone in the air. There must be a support somewhere, as Preston knew, but the stems were so fine and slender as to be absolutely invisible. They were flowers of Paradise, nothing less, a gleam of beauty and colouring surpassing naturalist's dreams.

Preston dragged himself to his feet and took from his pocket a tiny glow-lamp to which a small dry battery was attached. Still trembling from head to foot in his excitement and admiration, he examined his treasure carefully and with the critical eye of the expert. He could see now, by the aid of the lamp, that those black filaments binding the glorious bouquet together were as fine and yet as strong as the metal filaments in an electric lamp. And then, as the dawn suddenly broke like a violet bombshell from behind the morning mists over the lagoon, those amazing blooms collapsed like a soap bubble, and nothing was left but a handful of tight green leaves clinging to a log of wood about the size of a man's thigh. Preston knelt almost reverently and raised the rotting log in his arms. A few minutes later it was hidden away in a dark corner of his bedroom and covered with a damp cloth.

He had found it now, the search of years was finished, and the future lay plainly before him. Being a naturalist, he had seen quite enough to know that the plant he had secured was a large one, and that, in the hands of any wise horticulturist, the thing was capable of subdivision. It meant that, once he was safely home again, a fortune awaited him. And yet, even in that moment, he was conscious of the fact that he probably owed his amazing luck entirely to the other man, whose failure had brought about his own splendid chance.

He said nothing about his find for the moment, and all the more so because Barrington was still confined to his bed, and likely to remain there for a day or two. But when dinner was over, and night had fallen at length, Preston expressed a desire to have his coffee on the verandah, and there, in the dusk, with Inez by his side, told her what he had seen the night before.

"You quite understand what I mean," he said. "We must get your father away from here. If he doesn't go, he will die. He must go back to England; he must have a winter in Switzerland. If we could get him back to some bracing climate, he might live for years. As it is--"

"Oh, I know, I know!" Inez sighed. "But what can we do?"

"You must let me do it for you," Preston said. "You really must. Did it never occur to you how kind you have been to me? I have been here for a year. I came as a total stranger, and you took me at my own valuation. I shall never forget it, Inez. And I believe I can help you."

"You have found the Dawnstar?" Inez asked demurely.

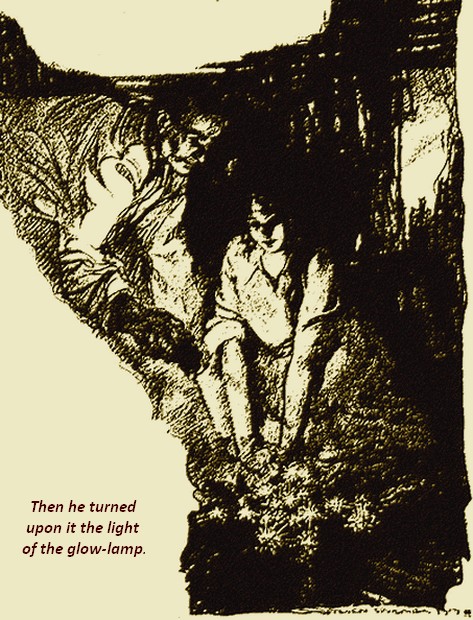

By way of reply, Preston rose and, going to his room, returned presently with the log, which he laid carefully down on the verandah. Then he turned upon it the light of the glow-lamp, which gleamed in the darkness through a violet shade exactly like the rays of the early dawn.

"Watch!" he whispered. "Watch!"

Very gradually the mass of dusty leaves on the log began to expand until they turned over and showed their glossy undersides uppermost. Then a bloom appeared, followed by another and another a little higher up, until the whole glorious thing leaped into life, a creation of such beauty and tenderness and exquisite colouring that Inez cried aloud.

"It is wonderful," she said. "There was never anything like it since the beginning of the world. Tell me all about it, Frank. How did you find it, and where? I wonder if I might touch it, or would it fade away like a dream?"

Preston snapped off the light, and in a few moments the dusty leaves lay at his feet again. He carried the log into his room, and returned presently to the lighted dining-room, where Inez eagerly awaited him.

"You have seen it now, and must believe,"' he said. "Inez, you have seen our fortune and our happiness."

As he spoke he looked into the girl's shining eyes, and she came forward and threw an arm around his neck.

"You mean that, Frank?" she whispered. "And you know—oh, yes, I have been waiting to hear you say that for a long time. And you know it, too."

Preston drew her close and kissed her. "Yes," he said simply, "I did. But can't you see that I could not speak before? I had no right to speak. But now it is all different. Now I have found something that is infinitely more precious to me than all the Dawnstars that ever bloomed. Not that I am indifferent to it, either, because it means happiness and fortune to us, and, I hope, many years of life yet for your father, because he is going to share it, because without him there would never have been you, and without him there never would have been a Dawnstar to light us on our way."