THE strange and tragic disappearance of Eugene Lastaire created quite a sensation even outside musical circles. It was too big a thing for the newspapers to miss, and accordingly they made the most of it. From such meagre information as the Press could gather, Lastaire had left London for a remote village in Devonshire after a somewhat unpleasant interview with Dennie Morthoe at the National Opera House. Everybody knew Morthoe was the lessee of that famous building, and one of the leading impresarios in Europe. A rich man himself and a musician of undoubted power and genius, Morthoe's great ambition was to form a school of opera of his own, and for this purpose he had sunk a vast fortune in the National Opera House, where he had gathered around him a collection of the most famous singers and musicians in the world. And not the least amongst these was Eugene Lastaire.

He had come to Morthoe a few months before, without reputation and without introduction, from one of the big schools of music on the Continent. What his nationality was, Morthoe had never gathered, for on that point Lastaire was both shy and secretive. That there was native blood in his veins Morthoe had not the slightest doubt. All he could gather was that this protegé of his had drifted westward from somewhere on the American coast in the neighbourhood of the Gulf of Florida, and that he had picked up a certain amount of education where he could find it. He was very dark—so dark, indeed, that the suggestion of negro blood in his veins was apparent to most people, which might have accounted for his sensitive nature. But this mattered little or nothing to a broad-minded and cosmopolitan musician and sportsman like Morthoe. It was enough for him that Lastaire was a great musical genius, with an almost boundless future before him. Like most pioneers, he had had to struggle hard; but Morthoe saw to it from the first that he had his chance, so that within a few months the discerning critics began to point Lastaire out as the coming man. And, indeed, one or two of his compositions had already carried him a long way.

It was at this point that he came to Morthoe with a first complete act of a new opera which aroused Morthoe to a high pitch of enthusiasm. The wonderful colour and melody of the work appealed strongly to him, for here was not only a great musical attainment, but a breadth and originality that promised fine things in the future.

Morthoe had literally jumped at it. If the opera finished as it had begun, then without doubt the new work would see the light at the National Opera House. Lastaire was advised to go away and devote his whole time to the completion of his masterpiece.

With this commission in his pocket, he went down to the north coast of Devon, where he worked on the opera day and night, writing and publishing musical trifles in the meantime as a kind of relaxation. And it was one of these slight melodies of his that led up to the tragedy.

It was only a little trifle in the way of a folk song, a weird, haunting, curious bit of work, full of original touches and alive with the fire of genius. It had been published by a West End firm, and immediately jumped into popularity. A few days later a letter from Sir John Follett, the well-known English composer, had appeared in The Times, in which letter Follett deliberately accused Lastaire of stealing one of his own original melodies. Sir John's work had not yet been published, but he was able to prove on pretty conclusive evidence that he was the composer of the work that Lastaire had published. And naturally a man so prominent before the public and of such high standing was believed in preference to the passionate protest made by Lastaire that his melody had been inspired by some rude folk song that he had heard in his youth in the huts of the aborigines on the Gulf of Florida; but as he had no evidence to prove this, and as ho was in direct conflict with the great English composer, he suffered. Works of his were sent back by publishers, and it looked as if Lastaire's star was setting almost before it had begun to rise.

That a man of Lastaire's temperament should take the thing greatly to heart was only natural. Seeing himself baffled and defeated, not to say disgraced, and knowing that what he said was true, he had turned his back on London and gone into Devonshire. He had refused to see Morthoe, who still believed in him, and who, in spite of everything, was quite prepared to carry out his promise so far as the opera was concerned.

A day or two later Lastaire disappeared. He had gone for a lonely walk along the cliffs on a stormy afternoon, and he had never returned. His stick and hat were found, but though the days went on, no single trace of the missing musician had been discovered. Morthoe went down there himself to investigate, but, however, without result. And so a month passed, and Lastaire was beginning to be forgotten.

And then a strange thing happened.

One morning Sir John Follett burst into Morthoe 's office at the National Opera House in a great state of excitement. His kindly, rosy face showed signs of every concern, the eyes behind the gold-rimmed spectacles were full of remorse. He flung himself into a chair opposite Morthoe.

"Well, what's the matter?" Morthoe asked.

"Oh, my dear fellow," Follett said, "I hardly know how to tell you. I have behaved like a scoundrel, an absolute scoundrel! How on earth I came to forget it, I don't know. Look here, Morthoe, I feel like a thief! I am a thief! I have stolen a man's reputation!"

"Ah, you are talking of Lastaire!" Morthoe cried.

"I am. Now, you know what I told you. You know what I wrote to The Times. When I sent off that letter, I honestly believed every word of it. It wasn't true, Morthoe, it wasn't true! I feel as if I had that poor young man's blood on my soul! I murdered him!"

"Tell me all about it," Morthoe said soothingly.

"What is there to tell? You know as much about it as I do. I thought that Lastaire had managed to get sight of that melody of mine one day he called at the School of Music. He could have done so easily enough. And you know I proved that my melody was written before he thought of his. And now I am not so sure. Not so sure! I know that I have done him an injustice. My dear fellow, my melody wasn't original."

"What on earth " Morthoe began.

"Well, it was like this. Late last night I was looking over a pile of yellow manuscript that I bought years ago in Scotland. It's quaint stuff, and must have been written I don't know how many centuries ago—folk melodies from the Hebrides, melodies that go back to the beginning of music, melodies played on a sinew stretched on a bone— and quite unconsciously I must have adapted the disputed song from those manuscripts. You know how things go round and round in your mind till you begin to think they are your own—sort of unconscious plagiarism. Poets and novelists have done it, and why not musicians? I have compared my music with the source from which I obtained it, and the similarity is remarkable."

"That's very strange," Morthoe said. "And yet I don't know. Music, like language, must have come from somewhere. Some genius invented it in the Dark Ages, and it must have spread from continent to continent, very likely in the glacial period, before the great oceans were formed. I shouldn't be surprised if the folk music of the world had come from a common stock."

"Ah, that's the point." Follett said eagerly. "I am an Englishman, and I learnt my music in London. I wonder how much of my work has been inspired by this old folk stuff, if I only knew it? And all the time I have been priding myself that it is my own! I have done Lastaire an injustice. I don't doubt for a moment that he was telling the truth when he said that melody of his had been adapted from an air played on a tom-tom or suchlike instrument in some native village away yonder on the Gulf of Mexico. And here am I, past the meridian of life, cruel enough to kill a genius! That's what it comes to, Morthoe. I murdered that wonderful genius of yours. I am a thief, a charlatan living upon my musical memory! I can't tell you how distressed I am. What can I do? I can only write a letter to The Times, deploring my mistake, and do my best to give the dead man back his reputation. He was a genius, Morthoe."

"He was indeed," Morthoe sighed, "and if things had gone all right, he would have stood before the world as the composer of the most magnificent opera we have had for the last twenty-five years. I say that because I know, because I have the first act in my safe yonder. I have never shown it to a single soul, and I don't suppose I ever shall now—unless, perhaps, I play it as a fragment—because I should never be vandal enough to give anybody the commission to complete it. I was going to take that opera round the world. It was going to be the great new work with which I was proud to identify myself. The tour is all complete. We are going to Paris and Stockholm and Milan, thence to America and Australia, and come back to Long Beach and those famous winter resorts along the coast of Florida. We shall start in about six months' time, and probably be away for three years. It's the biggest world's tour undertaken by an operatic company. And, after what you have told me, I would give half what I possess to know that Eugene Lastaire was going with us. He was to have superintended the production of his own opera and, of course, conduct it. The rest of the time I had engaged him for first violin in the orchestra. This is a shocking business, Follett." "It is indeed," Follett groaned. "I am entirely in your hands, Morthoe. I'll do anything you like." "Yes, but what can you do?" Morthoe asked. "You can only write what you have told me to The Times, and do the best you can to rehabilitate the poor chap's memory." And so itcame about that the musical papers and others were flled for some days with the strange story that Sir John Follett had to tell. Reams were written on old folk songs, and one of the daily papers went so far as to print the facsimile of Follett's song and the crabbed inspiration from which it was derived. Undoubtedly a great reaction had begun in Lastaire's favour, and his memory was held to have been cleansed of all suspicion and dishonour.

But unfortunately all this could not bring the dead man back to life again. Naturally enough, in a few days the incident was forgotten, except by Morthoe and one or two friends who had liked Lastaire, and were genuinely grieved over the mistake that had caused him, in a moment of despair, to lay violent hands upon himself. And so the time went on. Months passed, and the great world's tour of the Morthoe International Opera Company was drawing to a close. They had been all over Europe and the colonies in one long blaze of triumph, and at length they had reached the fashionable town of Long Beach, where all that counts in America had gathered for one of the most brilliant winter seasons that that famous spot had ever experienced. Big as Long Beach was, it was not big enough to detain Morthoe more than three nights.

On the third night it was his intention to conduct "La Bohème" himself, as he had conducted "Pagliacci" at the opening performance, filling up his time during the day with fishing in the bay, a sport of which he was passionately fond. The hotel in which he was staying was full of sportsmen, all of whom were there for the tarpon fishing, and with some of these Morthoe had gone out each morning until the last day of his stay there, when he took a boat and a native, and went out alone.

It was a perfect morning, with a light breeze blowing from the west, an ideal day for the sea. Here and there along the bay little islands and peninsulas were dotted, green oases in that glorious sea, where the few original natives who were left plied their craft and tilled their ground much as their forefathers had done any time since the world began. They were inviting little islands, these—indeed, some of them were of considerable extent—only a mile or two from the mainland, and therefore in close touch with the shore.

Morthoe sat there in the boat with a sort of glad feeling that he was alive, his mind intent on his sport, which, by the contrariness of things, was anything but good. He had not as yet succeeded in hooking one of the big silver fish to his own rod, and, as time was short, he was loth to leave that delectable corner of the earth until he had added to his sporting experiences.

The copper-coloured native working the boat shook his head gently. So far as Morthoe could gather from his jargon, he was deploring the fact that the wind was in the wrong direction for tarpon fishing, and that it would have been better if there had been a ripple on the water. But it lay now in one sheet of gold and opal and pallid blue right away to the misty horizon, where a few smudges of cloud were drifting inland from the sea. There was nothing else to do but to sit quietly in the boat, smoking and idling the time away until perhaps late in the afternoon a breeze would spring up, and then it might be possible to land a fish that was worthy of the occasion.

Morthoe sat there dreaming, with his pipe between his lips, after a luxurious luncheon and a glass or two of champagne. He was seated in the bow of the boat, making himself as comfortable as possible on a pile of sailcloth, and half asleep, when he suddenly sat up and looked at the dusky native in the stern. The man was gazing out to sea with eyes almost as sleepy as Morthoe's own, his lips were parted as he crooned a peculiar melody gently to himself .

And Morthoe recognised it instantly. It was the very air that had been the cause of all the trouble between Follett and Lastaire. Very quietly Morthoe sat there until the last bar was finished. There was no question about it. Beyond doubt, thousands of miles away from London, he was listening to a melody that had cost one man's life, and the melody, moreover, which was common to that languid sun-kissed coast and the rude salt breezes of the Hebrides. With a curious feeling upon him and with a voice not altogether steady, Morthoe addressed his guide.

"Where did you get that from, Sammy?" he said slowly. "I mean, who taught you the song you are singing?"

The native showed his yellow teeth in a grin.

"Nonebody taught me, sah," he said. "We all knows him. Him come from nowhere. Him sung by little piccaninnies as soon as dey knows anything. Fousands and fousands of years they sung him dese parts."

"What's it called?" Morthoe asked.

"Not called nothing, sah. Got no name, same as gentleman an' Sam here. You give me half dollar, an' I sing you more."

"Go on," Morthoe said good-naturedly. "Go on."

For the best part of an hour he listened, with an attention that Sam found decidedly flattering, to little snatches of queer haunting melody that sounded strange and yet familiar. Here and there Morthoe could undoubtedly pick out an air that bore a queer resemblance to more than one classical bit; but all this was as nothing to the startling discovery that there, floating on the heart of the glorious summer sea, he had found proof positive of the truth of Lastaire's statement.

He came back to himself presently, to the realisation of things, and the fact that a strong breeze had come up from behind a bank of black cloud sliding along the horizon, and that the boat was dipping and pitching on the sea, that carried white crests as far as the eye could reach. The whole character of the afternoon had changed, and Sam, deeply interested in a conscientious endeavour to earn his half dollar, had not noticed it. Then he ceased to chant in that monotonous way of his and got the oars out.

By this time there was not a craft in sight—all the rest of the fishermen had put in long ago—and along the beach the surf was screaming and beating in huge waves. Every moment now the sea was getting higher.

Five minutes ago they had been safe enough, and now, to all appearances, they were in dire peril. With the tide against them, they could not beat inshore; there was nothing for it now, so far as Morthoe could see, but to run before the gale and make for one of those little green islands on the sea.

"We're in danger, aren't we?" Morthoe asked.

"Much danger for you, sah," Sam said coolly. "We no get back—can't be done. Then we make for one of de banks, an' when boat bump all to pieces on sand, you swim."

"Oh, indeed," Morthoe said between his teeth. "I'm a fair swimmer, Sam. but I don't think I'd have much chance in a surf like that. What about you?"

"Oh, Sam all right," that worthy grinned. "Sam swim before he walk. You no worry 'bout Sam."

"I'm not," Morthoe said. "Now push on."

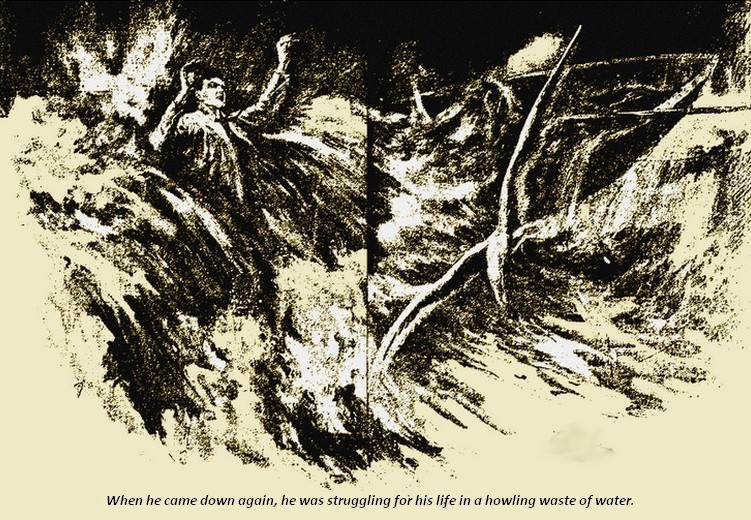

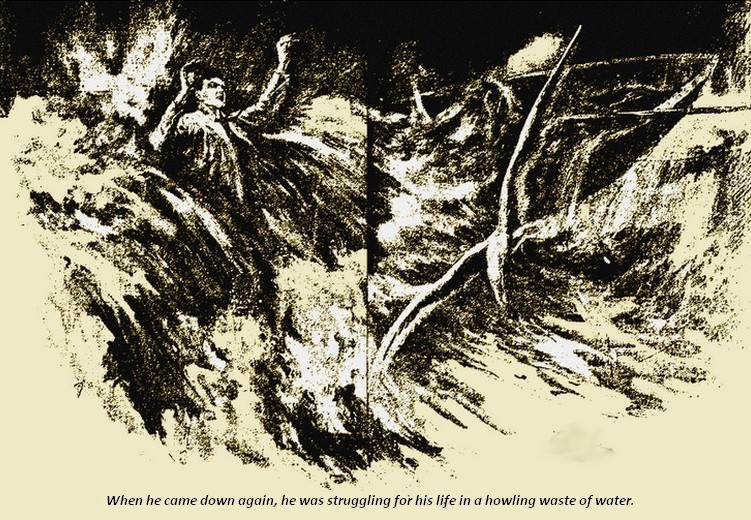

They pushed on accordingly through a white whirl of water in the direction of one of the green patches, which was now blurred and indistinct behind a curtain of flying foam and torrents of rain. They lurched forward, buffeted here and there by the wind, and carried over and over again out of their track by powerful cross-currents, so that a score of times they were swept past the beach that Sam was making for, and where he knew that the shelter of the curving shore might afford a possible landing for his passenger. For himself, he cared not at all; he knew every trick and turn of the tide and every swirl of the ocean current as he knew the palm of his own hand. He might be tossed presently like a cork on the surface of that boiling sea, but he had no doubt that the time would come when he would find himself with his feet on firm ground again. And so they struggled on, drifting here and there until darkness fell and they lay in the heart of the violet night with the storm halloing round them. There was no word spoken, for they were both busy enough in baling out the boat. And then presently, when Morthoe was beginning to wonder how much longer this was going on, something seemed to strike him and toss him as if he had been no heavier than a feather, and when he came down again he was struggling and fighting for his life in a howling waste of water. The boat had come down violently on the sands, and in the twinkling of an eye had been torn to matchwood.

With the desire to live strong within him, Morthoe struck out wildly, fighting in the darkness, half blind and breathless for what seemed to him to be hours. Then his knees encountered something soft and yielding, and a moment later he struggled to his feet. A big wave, rushing up the beach, caught him violently in the back and tossed him headlong on to a dry spit of sand. By some blind instinct he scrambled forward until, so far as he could see, he stood under the shadow of a fringe of palms, and then it began to be borne upon him that he was safe. A little while later he started to make his way inland, with the object of finding some habitation.

He was not in the least cold, for the night was soft and warm, nor was he conscious of any particular feeling of fatigue. He did not know what time it was, he did not much care. It could not be very late yet, because he could see the big electric arcs all along the fringe of the mainland, and the lights glittering redly in the hotel windows. He smiled to himself as he thought of the story he would have to tell on the morrow. Then just in front of him he saw a light glowing in what he took to be the window of a small native house. He hastened towards it, with the idea of food and dry clothing uppermost in his mind, then suddenly paused just outside, as the sound of music struck on his ear.

Somebody inside the hut was playing the violin, and playing it exceedingly well. And, strangely enough, the melody that wailed from those strings was the same that Morthoe had heard that afternoon, and the same that had led up to the tragedy of Lastaire.

With a curious feeling of tightening across the chest and a strange premonition that something was about to happen, Morthoe crept forward and opened the door of the hut. In the excitement of the moment he did not even stop to knock.

He saw a neat little room, lighted by one oil lamp that hung from the ceiling. He saw a heap of MSS. littered on the side-table, and a man with a violin in his hand standing before a sheet of music propped up in front of him. Very silently Morthoe crept forward.

"Ah, Lastaire!"he said. "Thank God, I have found you at last!"