THE tragic circumstances in which Professor Egerton Street disappeared from London and the world of science, of which he was such a distinguished ornament, are not generally known to the public. Most people are under the impression that the eclipse followed as a natural consequence on the sudden death of Mrs. Street, but a few people knew that the tragedy was precipitated by the professor himself. He was supposed to have injected a certain serum—previously tried upon his own person—and the death of the lady was due to septic poisoning.

Be that as it may, the circumstances never became public property. Most people looked upon the whole thing as an accident. Anyway, Street disappeared from University College Hospital, and his place knew him no more. He was supposed to be pursuing a series of studies in West Africa with the view to the stamping out of malarial fever, but that, after all, was only a rumour. Street had been a rather dour kind of enthusiast, very secretive, and possessing practically no friends. Basil Warburton, the entomologist, had seen him once at Liverpool Street Station with a variety of cases that gave him the air of a travelling naturalist. The two savants had exchanged a few words, but Street had not been communicative. He looked lean and brown and hollow-eyed; he gave just a hint of certain new discoveries. He wanted to know if Warburton had heard anything of a certain new red spider—locally called the "Red Speck "—an account of which had filtered home from Madagascar. As it happened, Warburton had not only heard of the spider, but he actually possessed a few live specimens. He says that Street's face lighted up in the most extraordinary manner on hearing this.

"You will be doing me—you will be doing the world in general an inestimable service if you will come down to my place at Crawley and bring a 'Red Speck ' or two with you. Warburton, I am on the eve of realising a most stupendous discovery. If my deductions are correct, malarial fever is at an end. Those fellows are quite correct—the mosquito and kindred insects are at the bottom of the mischief. I've been digging at the remedy for two years, and I've touched bottom. It would be an insult to your intelligence to ask you if you have heard of insect grafting."

Warburton replied that he had experimented in that direction himself. Articles on the subject had appeared in several of the leading domestic magazines. The thing was a little flashy and meretricious, and no good was likely to result from it. Warburton proceeded to speak of a hybrid dragon-fly he had grafted, but the larvae had perished, probably had not fructified. Street's eyes gleamed.

"I've conquered that," he whispered. "I've reached the breeding stage of the hybrid. The thing is not ripe for the public gaze yet, but I'll show it to you. Come down on Friday and spend a week-end at Crawley with me, and bring your red spiders along."

The offer was too tempting to be refused. Besides, Street was no pauper genius, but a well-to-do man in a position to carry out his experiments regardless of outlay. Warburton found the house pleasantly situated, the long ranges of glass had been stripped of vine and fern and flower, and given over entirely to the breeding of insects. It was rather a chilly March day, with fitful bursts of warm sunshine, so that Warburton found the glass-houses unpleasantly warm ever and again.

Street had certainly mastered his subject. He seemed to have every kind of insect in his greenhouses. In one warm corner, behind a series of thin muslin cloths, a cloud of gauzy little creatures seemed to sing and buzz in the still air.

"Mosquitoes?" Warburton suggested. "Well, they could do very little harm at this time of the year if they escaped. But where did they come from? I could localise every mosquito known to science, but I never saw any that size before."

"I bred them myself," Street proceeded to explain. "The original stock was grafted. Watch, and you will see that the wings are different. There is a dash of the tsetse fly in those fellows. I've had an arm as thick as your thigh from a hite of theirs. What do you think of them?"

Street led the way into another compartment of the greenhouse. The heat was unpleasant; the floor was of sand with fragments of volcanic rock scattered here and there. With the aid of a stick, Street stirred up the stones, and immediately a colony of tarantulas straddled over the sandy floor.

"Nothing wonderful about them," the professor remarked. "But you will see presently why I need them. Roughly speaking, my idea is to kill malaria by a war of extermination. Devise or breed some insect that will prey on the mosquito et hoc. Of course, you will argue that the remedy is as bad as the disease. That we shall see. What I want to get hold of by grafting is a slow-breeding insect that will be easy to grapple with when he has done his work. But he is to be a ferocious, poisonous fellow, and to a certain extent a clean feeder. I mean he need not be wholly carnivorous. Now suppose we take the Mexican hornet, which is one of the most dangerous of his tribe. Then we want a little of the tenacious ferocity of the spider, and here the tarantula comes in. My ideal warrior must be strong of flight and quick on the wing, and here enters the dragon-fly. This element gives the slow breed—for dragon-flies only come to maturity at the end of three years. Does this sound very weird to you?"

"No," Warburton said thoughtfully. "Nothing sounds extravagant to the scientiflc mind. Yours is going to be by way of a water insect as well. Still, even if you have succeded in producing fruitful hybrids, the ideal insect is the work of a lifetime."

"It is the work of exactly three years," Street said quietly. "The problem is solved, and the warm bursts of sunshine the last few days have done it. I have never mentioned the matter to a soul before, but I am going to let you into my confidence. The third generation, the perfected thing, has hatched out in a glory that was beyond all my dreams. Come and see."

Street led the way to the far end of the greenhouse, where a part of the dome roof had been removed. The heat was tempered by the outer air, yet it stood well up to 80 degrees. In one corner was a large gauze wire cage, not unlike a huge meat-safe, and hanging from the far wall were a series of soft-looking balls that closely resembled the nest of the mason wasp, though they were on a much larger scale. The sides of the blotting-paper structures were honeycombed like a sandbank where a colony of martins had built their nests. There was no sound of life until the little terrier hanging on Street's heels snapped at a fly and struck the wire gauze with his paws. Then the unseen colony set up a short, pinging hum, something like the screams of a flight of rifle bullets. From a shelf behind him Street took a little brown mouse from its cage. Swiftly he lifted the door of the exaggerated meat-safe and deposited the mouse inside.

A moment later and an insect darted from one of the honeycombs. The darting beat of its red wings hummed in the silence of the greenhouse like a hawk. Warburton was loud in his admiration—he had never seen anything like it before.

The creature was some nine inches from tip to tip of those wonderful translucent amber and purple wings. They trembled and flashed like jewels in the light. The body of the insect was some five inches, marked like a hornet for half the distance, the tail being covered with fine, down-like feathers, and tinted from bright red to brilliant peacock blue. The eyes were of deep green, the long legs were curved as the talons of a hawk. Warburton's admiration was absolutely justified and sincere. He had never seen anything like it before. It was so beautiful and yet so repulsive, so soft and noiseless, yet so tigerishly suggestive.

"You have not boasted in vain," he said. "Your hybrid is perfect, if, as you say, this is the third generation. Born here from the parent stock? Then there is no limit to the monsters of scientific creation. Is—is he dangerous?"

By way of reply. Street pointed to the mouse huddled up on the bottom of the cage. The little animal seemed to be half dead with fear. The big hawk poised over him, swooped delicately, and his curved beak seemed to meet for an instant in the fur of the tiny rodent's shoulder. It was all in the twinkling of an eye, the brilliant fly was poising again, but the mouse was dead... Hardened scientist as he was, Warburton could not repress a shudder.

"They're hungry," Street said in his level voice. "What do they eat? Insects mostly. They are particularly fond of mosquitoes. Those fellows are going to exterminate them. They are only a means to an end. But they will eat honey and small grain and fruit. Mind you, there is a crumpled rose-leaf in every couch, and the poisonous quality of those fellows is a little beyond my expectation. I suppose it is the mixture of the acid poisons of the tarantula and Mexican hornet in their blood. Would their bite be fatal to man? Yes, it would. There are over ten thousand of those fellows in that collection of nests, though you would not think it. When I have succeeded in reducing their poisonous qualities, I shall export them to the mosquito swamps, and I'm much mistaken if they don't root out the mosquito and their tribe pretty quickly. Fancy that little beast getting loose in England at this time of year! Fancy a full nest of them in any hedgerow in the autumn!"

Warburton did not fancy it, and shuddered again. But the scientist was uppermost at the time.

"I should like to have a look at that mouse," he said. "I should like to know precisely the qualities and quantities of the poison that killed him. I'll take the body to Longstaff, and let him make an analysis, if you like. I fancy it would be worth while."

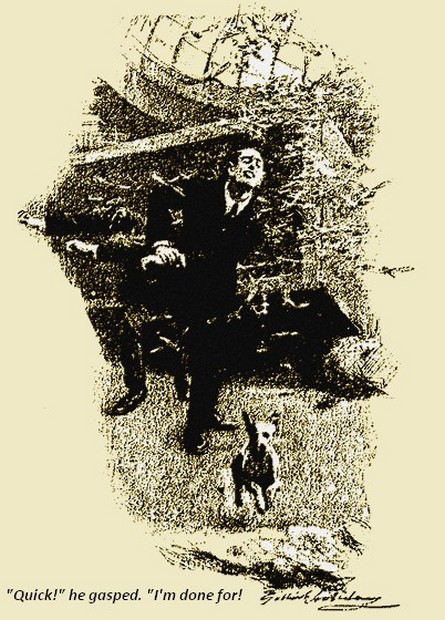

The idea struck Street as a good one. Very carefully he lifted the door of the cage and reached for the body of the mouse. But the little terrier was before him. The dog rushed in, banging furiously against the side of the cage. Street rose, unthinkingly, in his desire to recover the dog, so that the cage rocked and reeled, and with a scream as of a thousand flying bullets, the great quivering insects came pelting from the nests. How it all happened nobody knew. Warburton could never tell, but an instant later the cage was overturned, and the dome of the glasshouse was alive with a swarm of some thousands of the great insects. They rose higher and higher, darting and weaving in and out like a lovely pattern of perfect colouring. The humming scream of their anger was almost majestic. Faint and sick, Street was bending to and fro, holding his arm as if in some deadly pain.

"Quick!" he gasped. "I'm done for! One of them got me through the wrist. I had more or less been prepared for something of this kind. Look at the last few pages of Volume VI. of—"

Street collapsed on the floor, his sentence unfinished. Whether he was dead or alive Warburton did not know—he did not even seem to care. He was too fascinated to be frightened—he could not keep his eyes off that tangled, angry mass of lovely colour up in the dome. Death and destruction and hideous nightmare of terror lurked there. Then one of the amazing creatures darted through the dome light and poised in the air, the great purple and gold and amber cloud followed, and shone in the open air like some glorious rainbow of hues. And Street lay there dead and stark at the feet of his colleague.

Warburton crept outside, feeling sick and faint and shaky from the play of his imagination. Here was a deadly peril, such a peril as was sure to follow sooner or later upon the attempt to destroy the balance of nature. If a thousand or so of man-eating tigers had been let loose in Sussex, the effect, would have been less deadly and more paralysing than the escape of those beautiful insects. They were darting and playing now like a nimbus about the crown of a group of elm trees. Warburton could hear the pinging scream of their wings. They looked unutterably beautiful in the brilliant burst of sunshine, a thing of beauty terribly fascinating. But if they began to attack human life!

It would be impossible to fight the winged queens of the air. They could go like the wind whither they listed, bringing death and destruction everywhere. They were built for rapid flight—they might hold London captive one night and strike terror into Birmingham the next.

But Warburton had to pull himself together, he had to think of Street. The professor was dead enough, there were four or five livid red and white spots on his neck, as if the flesh had been cruelly gripped by a pair of pincers. The victim lay there quite peacefully, with a shadowy smile on his face. Death must have come very swiftly.

With the aid of a gardener, Warburton conveyed the body to the house. It was necessary to go through the formula of sending for a doctor, and that was a matter of time. Warburton would fetch his own man from town. This was outside the ken of the general practitioner. If only the trains had fitted in a little less awkwardly! Was there such a thing as a cycle about the house? The professor's motor-cycle was in its accustomed shed. Warburton grasped at the idea of action. He could ride to town on that. Anything to be doing something. Probably he would be back again before the local man arrived. Warburton sped along by way of Redhill and Reigate in the direction of London. It was borne in upon him presently that the roads were strangely deserted for the time of day. Nothing could be seen or heard for a long time, till the crest of a rise in the road disclosed a motor standing outside a blacksmith's shop. Warburton could hear the car humming as he raced along.

Two men coated in leather and hideously masked, racing men evidently, stood just inside the door. There was an air of excitement about them that Warburton did not fail to notice. One of the grotesque figures hailed him. From the Rembrandt shadows of the smithy a pair of hobnailed boots protruded, as if the rest of the owner had fallen there, overcome with beer.

"He's dead," one of the motor men jerked out. "Pulled up here just now for spanner, and found him lying like that. Have you seen anything of them?"

Warburton guessed what was meant. On the hood of the car he could discern a squashed yellow and red body or two, then caught in the sunshine the flutter of gauzy amber wings.

"Delirium tremens, gone mad," the other man said shakily. "What do you say to the car being attacked by a million of insects as big as a partridge and coloured like a poet's dream? Loveliest sight I have ever seen— at first. I made a grab at one, and he bit through my glove as if it had been a rose-leaf. Then the whole blooming lot made for us—quite a million of 'em. Frightened? Well, I should say so. But we were in armour, so to speak, and managed to beat them off. Got a couple of beautiful specimens, too, as dead as Queen Anne. And then we find the blacksmith dead, too. Perhaps they went for him.

Warburton fought down the physical sickness that seemed to hold him in a grip. As he dragged the dead smith to the light, he did not fail to notice the pincer-like mark on the flesh of the swarthy neck. One of the squashed hybrids was tightly grasped in his hand. Warburton asked feebly which way the swarm had gone. The motor driver pathetically requested to be given an easier one. Despite his forced hilarity, he was shaking like a leaf. He affirmed that he wanted London badly.

"And so do I," Warburton said between his teeth. "As it happens, I can tell you all about the business. Find the spanner and make your repairs. It sounds inhuman, but we must let that poor fellow lie there for the present. Get a move on you. I'll come along."

But the news had reached London first, the whole grotesque, maddening tragedy was being yelled by the newsboys along the Embankment. There was a telegram at his rooms waiting for Warburton from Crawley, saying that the inquest on Street would not be for a day or two, contrary to precedent. Before eight o'clock, the family of the unhappy smith had been interviewed; there was a column from an eye-witness, who had watched the attack on Mr. Cyrus A. Blyder's motor. A taxidermist in Holborn had a specimen of the deadly hybrid in his window, and the police were busy at the spot. Warburton himself was given over to the interviewers, who literally tore him to pieces. He had not meant to say anything, but he did not know the manners of the class. As a matter of fact, he told everything—and a great deal more.

The odd millions who had gone to bed overnight in ignorance of the new terror had it served up piping hot for breakfast next morning. A few more odd tragedies had dribbled in during the small hours. A rabbit-poacher at Esher had blundered into the clutch of a swarm sleeping on an elder bush, and his body, terribly distorted, had been found by a half-imbecile colleague in crime. Such is the effect produced on the nation by a cheap, pessimistic Press that thousands of people absented themselves from work during the day. But as the hours crept on, courage returned till midday, when the news spread like wildfire that a number of insects had been seen in a confectioner's shop in Regent Street. Curiosity overcame fear for the moment, and a rush was made westward. Surely enough, the news was true. Half-a-dozen pretty shop-assistants stood pale and frightened on the pavement, inside the shop something was humming and pinging and darting like a beautiful humming-bird poised over a vase of flowers. Presently something boomed overhead like the zipping song of many telegraph-wires in a gale of wind, and, as if by magic, the smart confectioner's shop was a veritable aviary of the beautiful hybrids. A thoughtless 'bus-driver made a slash at a darting insect with his whip, and instantly the gorgeous thing hummed at him and struck him in the throat.

With a scream of fear and pain, the man dropped from his box and lay writhing in the road. It was a crisp, clear day, but the unhappy driver was bathed in perspiration. He seemed to be frantic, half mad with the pain that he was suffering. He tore wildly at his collar, his lips were dripping with foam. But he did not die, as the professor and the smith had done, though the maddening pain was likely to produce complete physical exhaustion.

"He can't endure agony like that much longer," someone said, pushing his way through the crowd. "I'm a doctor. Bring him along to the nearest chemist's shop. This is a case for the hypodermic syringe and ether. It may be the means of saving the poor fellow's life."

There was no occasion to ask the crowd to stand aside. Fear had overcome curiosity, and the mob had melted into the air. The loot of the confectioner's shop was pretty well done by this time, the darkening air was humming again with the darting hybrids. Like wasps and bees, and others of their tribe, they might have been expected to seek some dark corner for shelter and rest, but possibly the glare of the electric lights had excited them. Never, perhaps, had the streets of the West End been so deserted as they were now. London had scuttled home like a colony of frightened rabbits directly darkness had set in; a creeping policeman or two along the Embankment discovered here and there a solitary hybrid banging his beautiful head against the arc lights, the buzzing of its wings making a weird sound.

All the same, the legislators of the country could not stand still merely because a brilliant and eccentric scientist had invented a new hybrid by the process of insect grafting. Most patriotic members of Parliament walked to their duties, for coachmen generally had flatly refused to turn out in the dark. The theatres might have closed their doors, for all the business they were doing; the music-halls were deserted. Some genius had suggested the arming of the police in Parliament Street with rackets, and this had been done. There had been up to ten o'clock a total bag of sixty hybrids. And there were still some ten thousand of them at large in London.

About ten o'clock the serenity of the House of Commons was marred by sounds of distress proceeding from the direction of the kitchen. A flying squadron of the hybrids had attacked the provisions there, and had been driven off by the pungent smoke of burnt brown paper. They came darting and hawking along the Corridor into the Chamber itself, poising high overhead like a flight of beautiful birds. The hum of their wings spoke of anger. An honourable member paused in his speech, and hastily made a truncheon of the newspaper from which he was quoting. Two of the gleaming terrors came in angry conflict, and dropped flopping and struggling on the table in front of the Speaker.

Dignity could stand it no longer. There was a mad rush from the Chamber. Outside, a big, sweating policeman was vigorously fighting off one of the foe with his racket. Professor Clements, member for St. Peter's, turned the collar of his coat up and called for a hansom. But no hansom was to be seen, so the savant had to make his way to Warburton's lodgings on foot. Warburton, tired and fagged, had just returned from Crawley. He had been down to the inquest on Street, he explained. Of course, the inquiry was adjourned, as it was likely to be many times yet.

"That's what I came to see you about," Clements said. "It is pretty fortunate that there is one man who can tell me the source of this diabolical invasion. What beautiful, Satanic things they are! And yet the whole idea is so disgustingly horrible. Fancy one of those things dropping on your face when you are asleep! The mere idea fills me with terror. Surely, Street must have been mad when he was inspired by this thing."

"I don't think so," Warburton said thoughtfully. "The root idea was logical enough—a way of exterminating the malarial insect with a slow-growing hybrid that man would successfully combat afterwards. I have no doubt that Street foresaw some such danger, and had schemed a way of meeting it. But, unfortunately, he had not time nor opportunity of telling me."

"Then you think that there is some way out of the mess?" Clements said. "If they were wild beasts, or anything of that kind , if they were merely malarial germs that we could fight with recognised weapons! But with those wonderfully flighted insects we are quite powerless. In eight-and-forty hours they will spread all over the kingdom. Having some of the habits of the wasp, they will break up into colonies and build nests. And what human agency have we to fight those nests? The loathsome, lovely creatures may take it into their heads to make an enemy of man. Good Heavens! the mere suggestion throws me into a cold perspiration."

"I dare say we shall find some way," Warburton began feebly. "And no doubt—"

"Yes, but the horror of it! You think that Street—"

"My dear fellow. Street was no blind enthusiast, who let his heart get the better of his head."

"Have you thought of looking amongst his papers and notes for anything likely to?"

Warburton jumped to his feet with a cry. A sudden light had broken in upon him.

"What a dolt I am!" he exclaimed. "I never thought of that. Why, as soon as the accident happened, Street turned to me and said something. What did he say? Ah, yes. 'Look at the last few pages of Volume VI. of—' alluding to his diary, no doubt. Come along, Clements."

"Where are you going at this time of the night?" Clements asked.

"Crawley," Warburton cried. "To inspect Volume VI. of poor Street's diary right away. We must get there at once, if we have to take a special train."

As it turned out, the special train to Crawley was necessary. It was no time for nice ceremonies, and Warburton ordered it without delay. An anxious superintendent stated that the enterprise would cost the voyagers nothing.

"Our directors ought to be glad to place half of our stock at the disposal of you gentlemen," he said. "Anything so long as you are trying to put an end to the state of terror. Why, since early this afternoon our main line of trains have been positively empty. Nobody is coming to London at present. A few insects holding up a big city like this! Seems almost incredible, doesn't it?"

It did, but there it was. Still, there was consolation in the idea that these two scientists were doing something as the special flew on into the darkness. There was a momentary stoppage at Three Bridges owing to a mineral train on the track; there was an unusual bustle going on in the small station, considering the time of night. Warburton leant eagerly out of the carriage windows. A couple of porters were busily engaged in pouring a stream of water from a hydrant into one of the waiting-rooms.

"We've got three of those beastly flies in there," the stationmaster explained. "We're trying to drown them out. There's a nice crisp touch in the air to-night."

Warburton started as a sudden idea came to him, but he said nothing to his companion. They were very silent until Street's house was reached. The place was absolutely deserted, for the servants had vanished. Nobody could be persuaded to face the hidden dangers of the house. Who could tell what dreadful monster would rise next? Street's body had been conveyed to an adjacent hotel, his own place was dark and desolate. Warburton settled the matter by breaking a window and entering the house that way. He fumbled about until he touched the electric switch, and presently the whole place way flooded with light, Street had had a full installation even into the greenhouses.

There were cases and cages all over the house. Even in what was the drawing-room Warburton and his companion could see those great safe-kind of arrangements from which the deadly hybrids had escaped. Clements idly rattled one with a stick, and instantly the whole structure hummed like a hive of angry bees. Quaint things like little flying lizards darted against the bars.

"This is as bad as delirium tremens," Clements murmured. "Now, what are those abortions, for instance? Are they intended to be for some good purpose, or are they as deadly dangerous as the hybrids? We dare not pry too far, because we don't know. And the only man who does know is dead. To clear the place and render it safe—why, good gracious! there may be thousands of eggs and larvse hatching at this house, not necessarily dangerous in their present condition, but—"

"I've found a way to deal with them," Warburton said hoarsely. "It's a desperate, not to say a drastic, remedy, but we shall have the approval of the State. Let us get this creepy business over as soon as possible, Clements. Come to the library and find the diaries. I am hoping that we may discover the balm of Gilead there."

The amateur housebreakers were only concerned with the sixth volume of Street's diaries. There was a mass of figures and calculations there that conveyed nothing to anybody but the writer, but towards the end of the paper-covered volume came something like a concise account of the apotheosis of the hybrids. At some length the origin of their being was set out, and then the measures by which they were to be successfully combated when their work was done.

"By Jove! the thing is fairly simple," Warburton cried. "I can see nothing here that speaks of an antidote to the bite of the creature. But they can be rendered harmless by the application of ammonia and eucalyptus to the skin—in fact, Street says that they will fly in terror before it, I should like to see the experiment tried. Come to the laboratory."

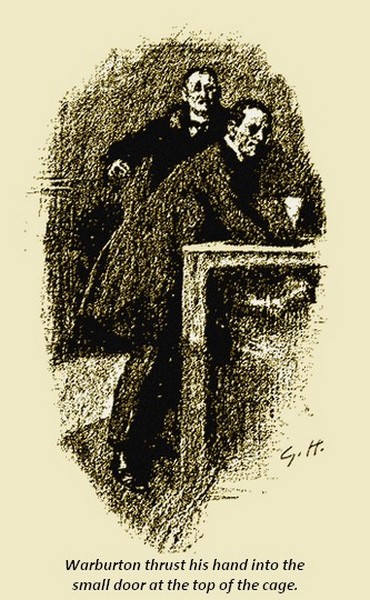

The necessary ingredients were found and mixed in the proportions set out, and then were rubbed by each man on his hands and face and neck. It was just possible that a close search of the greenhouses would discover another case of the beautiful hybrids. There were many cages picked out by the flare of the electric light, and many strange colonies of insects disturbed, before Warburton's eyes lighted on one of the zinc safes with a couple of the peculiar blotting-paper nests inside. A vigorous shaking filled the cage with a tangled, angry knot of dazzling colour. The screams of vibrating wings hummed in the air. Beating down the terror that possessed him, Warburton thrust his hand into the small door at the top of the cage. The insects darted back from him, one hit the top of the cage and fell back upon his sweating, pungent palm. It was all he could do to keep from screaming. It was hard to have full faith in the dead man's remedy.

But nothing happened. The great insect lay on the sticky palm, its wings palpitating gently. The long, beautifully marked body was bent backwards, then the wings were absolutely stilled. Warburton pulled his hand from the cage and dropped the hybrid on the floor.

"Dead," he said calmly. He was outwardly cool enough, though his lip was torn where the teeth had met it. "Dead as a door-nail. Paralysed by the odour given off from the compound, I expect. Clements, we've got to see this thing through now. You keep those diabolical flies stirred up to a pretty passion whilst I get a spray. We'll try it on the whole lot."

Clements nodded his approval of the suggestion. With a stick he kept the hive in a state of commotion. The wings of the creatures screamed angrily, the whole space was a dazzling flash of kaleidoscopic colour. It was very repulsive, and yet strangely, weirdly beautiful. Warburton came back presently with a fully charged bottle of spray in his hand. At a distance of a yard he proceeded to discharge the fine spray into the cage. The effect was like magic, the scream of those opalescent wings ceased, on the instant a cloud of insects sank to the bottom of the cage and lay there, a tangled heap of dead creatures. Warburton broke out into extravagant joy.

"Settled the whole business," he said. "In the cause of science, mind you, it is a pity. In the interests of humanity we should have preserved some of those creatures. But the country wouldn't stand it—the terror is too great. Still, if we can show the people quickly there is a sure and certain way out of the danger, why—"

Better not," Clements said thoughtfully. "No good ever came yet, and no good ever will come, by interfering with the balance of Nature. The demon that scotches the demon is always the worst demon of the lot. The winged terror has been bad enough, especially now that the master hand controlling it is no more. Street was thorough in his methods, he was a fanatic in the cause of science. And Heaven only knows what new horrors are concealed in those breeding-cages, and the larvae we found in those novel incubators in the boiler-house. Street knows, and he is dead. If we destroy everythinig—"

"We are going to," Warburton said grimly. "Let's go and find a bed somewhere— my nerves are pretty steady, but I would not sleep in this house for a V.C. Come along."

Warburton got through to London on the telephone early the next day, and the result of his interview with the Board of Agriculture and Spring Gardens was quite satisfactory. He would be back in town as earlv as possible, he said. But, meanwhile, there was much to be done. He was going to take the law into his own hands. A load or two of straw and a few gallons of paraffin were all that Warburton needed. Half an hour later, and Street's late residence, including his long stretch of glass, was a mass of calcined ruins. What secrets those grey ashes held would never be known...

It was late in the afternoon before Warburton and Clements reached London. There were more people in the streets than there had been yesterday, for the secret of the cure had been proclaimed, and some of the bolder spirits were venturing out again. The air reeked with the smell of mingled eucalyptus and ammonia. One of the evening papers had an account of the manner in which a County Council labourer covered with the mixture had tackled a score of the hybrids in a Mayfair house, and had overcome them with the greatest ease.

But there were nearly ten thousand of the insects to be accounted for, and people generally had not forgotten the horrors of the past few hours. A large concourse of interested spectators had gathered in the operating-theatre of the Metropohtan Hospital to see Warburton deal with a few of the hybrids taken in the butterfly nets for the special occasion. Half an hour later, an eager throng of men were scouring London, prepared to deal with the evil, when met. The run on ammonia and eucalyptus severely taxed the resources of the chemists' shops. Warburton looked thoughtfully contented as he walked to his rooms. He saw that the sky was clear, and that the sun was going down like a red ball in the west.

"The elements are coming to our assistance," he said. "If this weather goes on for eight-and-forty hours longer, the situation is absolutely saved. I'm sending a letter to the Central Press and Press Association to-night, asking them to see that it appears in every morning and evening paper in England to-morrow. See you later."

It was exactly how Warburton had hoped and asked for. His letter called attention to the fact that a severe frost seemed imminent, and that it looked likely to last for a day or two. If the frost maintained itself, it would be the duty of every householder to search his premises, and see that they entertained no specimen of the deadly hybrid. If they were driven out of doors, the first sharp frost would be fatal to them. They were bred practically from tropical insects, and therefore they could not stand cold. At the same time, it would be only prudent to see that the insects were quite dead, and not merely torpid. It was necessary, also, for everybody who found even one of the hybrids to report the fact to the Board of Agriculture. Not one of them must be left alive. An open window and the faintest touch of

ammonia and eucalyptus would be sufficient to drive the insects into the open air.

At the end of twenty-four hours the figures began to come in. Between London and Bedhill over eight thousand five hundred of the insects had been found, either dead or torpid, a great number of them being discovered clinging to the arches of the bridges over the river. The wave of terror rolled back, and London became itself again. To the satisfaction of everybody, the frost continued, so that on the morning of the second day over nine thousand seven hundred and fifty of the lovely hybrids had been accounted for. An odd specimen or two drifted here and there for the next week, and then eight days passed without further result. Beyond the few specimens kept and preserved at South Kensington, none remained.

"I fancy the danger is over," Warburton said to Clements, as they lunched together a few days later at the Athenaeum Club. "And yet it seems a pity, too."

"Great pity," Clements agreed, "It's a thousand pities, too, that Street died in so tragic a manner, for, unless I am greatly mistaken, a great secret perished with him. I would have given much to see the fight between the hybrids and the mosquitoes on the Gold Coast. And yet the situation would not have been without its terrors."

"What do you mean?" Warburton asked.

"Well, those hybrids would have increased in size in that congenial atmosphere. They would have developed habits of their own. And Street, after all, was working on a theory. Fancy a dozen of those hybrids as big as an eagle—"

"Don't!" Warburton shuddered. "The horror was quite bad enough as Street evolved it."