THEY said in Verolstein that the young Queen was sorely afflicted with distemper; gossips had it that she could do no more than paint red roses, that she lived in a bower of red roses, and that she spoke and thought of nothing else. All of which was bad, for Verolstein was disturbed over the outbreaks on the frontier, whence the rebel Count Arnheim, the Queen's cousin and a strong pretender to the throne, was making much headway. Verolstein appeared to be loyal enough, and there was a strong disposition to give the sweet young Queen her chance. But then, Verolstein had ever been fickle as a courtesan, and the thoughtful growled under their breath for want of a king.

And for once rumour spoke the truth. Perhaps there was some method in the young Queen's madness, for this was the eve of St. Agnes—Queen Agnes's patron saint—and all good and true Verolsteiners and Arturians generally would don the red rose of royalty to-morrow. Up amongst the hills yonder were white roses by the hundred, where Arnheim's followers lay; for to-morrow, strange to say, was Arnheim's birthday, and every follower of his would don the white rose as a matter of course. The same thing had happened a year ago, and the streets had run red with the blood of those who carried the white rose. It is a slippery throne that rests on a foundation like this.

There would be no white roses to-morrow—at least, so far as the province of Verolstein was concerned. And it would go hard with anyone who was seen without a red one. Therefore, towards afternoon, the giddy and heedless were scouring the gardens far and wide for the wine-dark blossoms. Before nightfall there was no such thing to be found in the whole fair province. Even the Queen's roses were exhausted. She crossed the studio where she was painting the typical red flower, and looked out into the wide, wild, beautiful jungle of rocks and gorges and ferns that formed the castle garden. She was very slight and very pale and very fair, with the most wonderful red-gold hair in Europe, and her blue eyes, if filled with trouble, had no glitter of madness in them. It was hard to be young and enthusiastic and tender for one's people, and yet to be thwarted at every turn by traitors thinly veneered as friends.

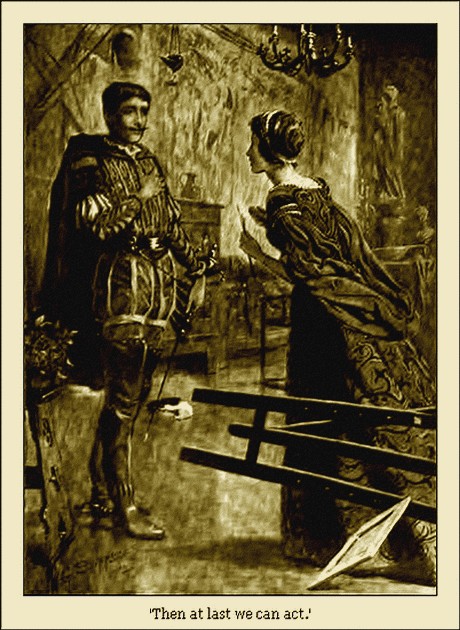

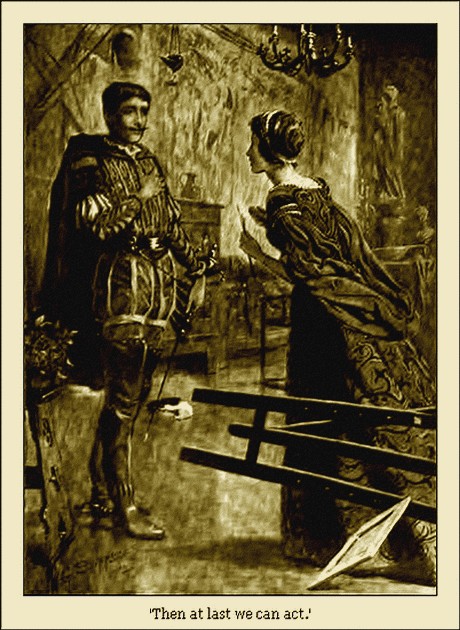

A slight, handsome little fellow crept into the studio with something of the timidity of a brown mouse. He picked his way daintily between the artistic confusion of bronze and silver and statuary, his absurd little moustaches were faintly cocked.

"Ambrose!" the Queen cried, "you have been successful?"

The other bowed till his rapier started from the scabbard.

"Even I, your Majesty," he replied. "Your poor troubadour has accomplished this thing. I am going to show my sweet mistress yet that I am capable of more than a rondel or a neat couplet in praise of a set of drooping lashes."

"We must not quite lose our fascinating minstrel, Count."

"Ah! that you never shall, madam. But as to the Duchess. De Mignon was pleased to be flattered by my attentions. She is fifty, and the language of love is my mother tongue. Therefore when I pressed a note into her hand imploring an assignation, she consented. At lovers' perjuries they say Jove laughs. That is well for my future state. She came, that painted spy of Arnheim's, that creature of D'Arolles the infamous. We rambled hand in hand over the heath, in the rocky ways, and behold! love's dalliance was cruelly wrecked by a fall on the part of the Duchess. By my dear saint! one of those slim ankles of hers is now as the knee-pan of a kitchen-maid. De Mignon is like to keep her couch for three days to come."

The Queen came hastily forward, knocking her easel over on the way. The crimson smear on the canvas lay there unheeded.

"Then at last we can act," she said. "We are free at length to move without being observed. De Mignon is an ally of Arnheim's and D'Arolles'. See here."

From the bosom of her dress Queen Agnes produced a roll of paper. From it fell a few withered petals of white rose.

"Natalie brought me this just now," she went on; "she found it in the pocket of one of the Duchess's dresses. Ah! if she only knew how regularly her rooms were searched! There is the conspiracy for eyes to read. Do you know what is going to happen, Ambrose? To-morrow my dear old friend and tutor, Cardinal Marmaison, holds a service in the Cathedral at Rems in honour of my fete-day. All my ministers and friends will be bidden to attend. As the State Convocation will be sitting at Rems, nearly everybody devoted to my cause will be there. Rems is my great stronghold. And yet every one of my followers will wear a white rose."

Ambrose stared at his mistress with respectful amazement. For once his eyes expressed more than he intended to convey.

"No, no," the Queen cried, "I am not mad! Nobody should know better than yourself why I have assumed this malevolent distemper. What I say is true. To-morrow D'Arolles gives a dinner to my ministers and others devoted to my service. Afterwards he will present them with the rose, which is my badge, and then they will proceed to the Cathedral. D'Arolles will feign illness and go out. Then every red rose will become a white one, and all these good men and true will be slain as they stand by my infuriated burghers of Rems."

"But, madam," Ambrose stammered, "if those red roses—"

"Will really be white ones. The matter is foreshadowed in this letter. To-morrow the Duchess is to lure me out into a distant part of the grounds. From thence I am to be spirited away. In the anarchy following my disappearance and the death of my faithful ones, Arnheim will sweep down from the hills and make a bid for power."

"Yes, madam; but those changing roses," Ambrose persisted.

"Man of little wit!" the Queen cried. "Is not D'Arolles one of the most subtle chemists in Europe? Did he not come near to the stake at Vamprey for his witchcraft?"

"I have always been sorry for that escape," Ambrose said regretfully.

"Those roses will be chemically treated. A certain exposure to the air. and the red will fade and the white come through. A whisper will go forth in the streets of Rems that my ministers are bearing Arnheim's colours on their breasts. Even if they destroy them and appear without badge at all, it will make no difference. They must be saved."

Ambrose flushed. The pretty spoilt darling of the Court, the squire of dames, the butt and sport of ruffled gallants, he saw his chances now.

"I am ready to die for you," he said proudly.

"Do better than that," the Queen exclaimed. "Live for me. Ambrose, I have every confidence in your courage. And you are quick and smart, some of my devoted fellows are not. You will have to ride far and fast in time to spare the tragedy. You will be barely able to reach Rems Cathedral before three of the clock to-morrow."

"I pledge my word on it, madam."

"Then go. Two of my guard shall accompany you. Choose for yourself."

"Then I will have Ulric and Eric Sarnstein," Ambrose replied. "Right swordsmen both, and distant kinsmen of mine. They know that my rapier is gilded goose-quill. Ah! here will be something to sing of by winter firesides."

He stooped, caught the Queen's hand to his lips, and swaggered away, looking a little more like an audacious brown mouse than usual. To the peril of the way and the danger of the journey he gave no single thought.

Out from the jaws of the western gate of the castle three cavaliers rode away with the jaunty air of men on pleasure bent. On Ambrose Valery's saddle-bow was a small packet which he secured with careful attention—a small box of wet moss in which the Queen had packed the blood-red roses for her followers to wear on the morrow. There would be none to be got in Rems, and without them there would be short shrift for the three anywhere within a league of that city.

"Safe from all prying eyes!" Ambrose cried. "The cat has pinched her foot, and the cream is safe on the shelf. It is a fete, not a fight, that lies before us."

"Cats have nine lives," said Ulric. "And we have not done with the Duchess yet."

"It is D'Arolles we have to deal with," Eric observed more quietly. "Until his twig is limed for good and all, our lives are in jeopardy. I fancy there may be a fight to-morrow. I pray by my patron that I may be near D'Arolles when the steel is stripped, and that my arm may be as ready as my heart. Scotch that black snake, and our sweet Queen is safe for many a long day hence."

The three men looked one to the other swiftly. The bolder Eric had merely voiced the thoughts that ran rampant in the minds of the others. Of all the unscrupulous scoundrels in that fair province, none could compare with D'Arolles. No son of the sword or brother of the rapier was he, but a cunning diplomat ever playing for his own hand and purse, and possessing a fatal faculty for clearing foes from his path. Man or woman, it was all the same to him. He quarrelled not with them, he smiled fairly in their eyes, and then they died of plagues of fever, suddenly and awfully sometimes. Heaven alone knew the secrets of that sealed laboratory of D'Arolles.

"We shall have him unawares!" Ambrose cried. "He little guesses our errand. So he is going to feign illness and creep from the Cathedral unseen. Ha, ha!"

He laughed gaily as he whipped up his sorrel pony. Ulric and Eric stretched along at a hand-gallop, as fine a pair of reckless soldiers as a maid's eye could fain to see.

"He will go out feet first," said Eric. "A vengeance—a vengeance, swift and unexpected and terrible as the death of one of his own foes."

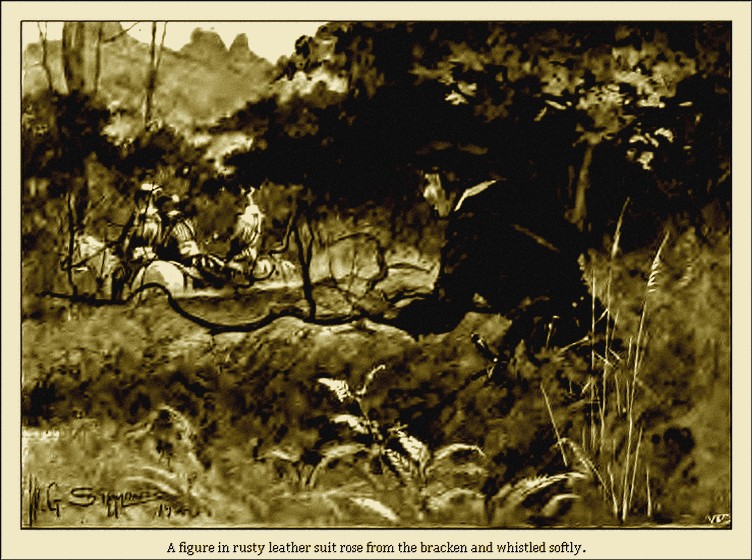

As they swept down the road in a cloud of dust, a figure in rusty leather suit rose from the bracken and whistled softly. The next moment the bushes parted, and a fine, up-standing black horse came out. With an approving pat of the glossy neck, the shabby wayfarer flung himself into the saddle and dashed headlong down a bridle-path so that he emerged presently on the high road some miles or so ahead of the Court rufflers pressing in his rear.

They road on gaily through the mountain paths, clamouring as they went. There was no fear before their eyes, they were on the Queen's business, and it would have gone hard with any man who said them nay. Not that they had any fear—nor, indeed, hope of this, seeing that their mission was secret even from D'Arolles' ally, De Mignon, now happily held from mischief by reason of her afflicted ankle. Ambrose told the tale in his own inimitable manner until the others creaked in their saddles with laughter.

On, on they rode, sparing not their horses till the curtain of night fell from the silent, everlasting hills. They were up on the crest of the ridge now, and far away across the plain they could see the brown haze where Rems lay. They had forty miles to travel, yet they would be there in time.

"A plague on it!" Ulric cried. "My mare has gone lame!"

"And mine," said Eric, "sobs like a maiden for a faithless lover. Do I dream, or is there good entertainment for man and beast hereabouts?"

They came to an inn presently, a long, low, beetling building, where lights were flashing in every window, and the din of voices and the crashing of flagons smote on the uneasy air. A crowd of rufflers and helpers hung about the doorway, the long taproom was crowded with the low, swaggering type only seen where trouble and strife are in the air. A fat, greasy man in a leather cap and blue apron accosted the travellers with surly impudence.

"A bed!" he chuckled in an oily wheeze. "Not for our gracious Queen herself."

Eric rattled the handle of his rapier significantly.

"Our mistress would indeed be sore pressed before she came here," he said, with a contemptuous glance for the company and the reeking walls of the low room, where some two-score adventurers were carousing. "Clear a table yonder, sirrah, and get us supper at once! We shall want a change of horses, too."

Boniface protested more civilly that a horse could not be procured for love or money. There had been a great call for them lately; besides, Arnheim's followers had been raiding the hills in search of likely cattle. Their Excellencies might make inquiries, of course, but no horses would be found. The man was lying fluently, with his tongue in his cheek all the time. Even Ambrose grew grave.

"Someone has been before us," Eric muttered, as he pushed his way none too civilly to their table. "No horses in the hills! Did ever man hear the like?"

"The horses will be found," Ambrose smiled. "We can travel no further on our own. Do you stay here and keep your ears open whilst I see to our steeds' comfort. Mayhap I may see something likely in the stables yonder."

Ambrose returned presently with the air of a man whose exertions have not been in vain. He came with the intelligence that the horses were utterly foundered, and that if Rems was to be reached in time to avert the calamity, they must needs be unfettered by anything nice in the way of scruples.

"There are those about here who are used to finer quarters," he said. "There are four black beasts in yonder stables that might belong to a prince, and their harness to a coxcomb of neighbour Louis' court. What are they doing here? And what is his business?"

By the door sat the man in shabby leather, the man with the black horse who had preceded our three cavaliers a league or so on the journey. With a big leather 'jack' before him, and a long Dutch pipe between his lips, he seemed to be heedless of everybody.

"Do you know him?" Ulric asked, carelessly stretching his legs.

"Aye, marry I do. The rascal is one of D'Arolles' familiars. An evil-looking fellow, who can be mighty agreeable amongst the kitchen louts when he has the mood. Sings a good song and has a fine ear for a keyhole. And there is Wandering Will, too. Hi, Will!"

The new-comer took no heed. He was dressed fantastically in a cast-off Court suit, which was reduced to a neutral tint by exposure, and torn to rags by reason of the owner's wanderings in the bypaths of the hills. His long, matted hair hung on his shoulder's, behind him was a kind of rude minstrel's harp. A rollicking rattle of ironical applause greeted his entrance, to which he bowed with profound gravity.

"Have a care for the Queen, have a lip for the cup,

Keep your rapier polished wherever you go,

And take care for your horses, yet other men's steeds—"

He flashed over a bright, meaning eye at Ambrose as he flung himself into one of the benches. Also with a gesture he indicated the man behind him in the rusty leather suit. The look and the gesture were not lost on Ambrose. And Wandering Will was a mine of information ever. Tossing off a brimming cup of somebody's, Will began to sing.

His fine bass voice rolled round the room and rang in the smoking rafters. A roar of applause followed the singing of the song.

"A mere nothing," Will muttered. "There is one here who is my master. Come, Excellency, will not you put up with us for once and let us hear what singing is?"

"I believe the varlet is speaking to you, Ambrose," Eric growled. "Give him the flat of your rapier for his insolence."

Ambrose shook his head. Assuredly there was some deep scheme behind Will's audacity.

"He speaks between lines," he said. "There is mischief afoot. Did you hear what he said about the horses? I'm going to sing, I tell you. When I start, do you step out and get saddles on to those three black horses. There is only one dolt of a helper in the stables. Wait for me outside. I'll join you as soon as possible."

With some assumption of hauteur, Ambrose hummed a song. Presently his fine tenor voice broke out fresh and clear as a lark. Keen and convivial as the company were, they had never heard anything like this before, this simple little love song like a gem on a dust-heap. In the breathless silence, Ambrose could hear the jingle of bit and bridle outside. As he finished, and the last pure note died away, there was a yell for another.

"One at a time, my friends," Ambrose laughed. "I see one by the door whom I have heard trill a jocund ditty before now. Come, Leather-jacket, it is my call. Give 'em the song of the Five Horsemen."

"I will see you all on the rack first," the leather-jerkined man growled.

Something like a threatening growl followed. The last speaker put down his pipe and slid towards the door. Wandering Will stood before it, his arms outstretched. A dozen dirty hands were laid on the fellow, and he was hoisted on the table.

"Sing, sing!" they roared. "Sing, or we'll tickle the notes out of you with our blades!"

Leather-jacket started hastily to comply in a rolling voice that filled the room. It was a long song that Ambrose had purposely chosen. He slipped out in the uproar, glad when the fresh, pure air smote on his lungs again. Eric and Ulric were already mounted, a third horse stood pawing the ground close by.

"That was neatly done!" Ambrose cried. "We shall not be missed for a good ten minutes yet. I set my fellow a task, and Will will see that he does not move too soon. And you?"

"Our task was easy," Ulric explained. "There were the horses, and no more than the oaf of a stableman to say us nay. He protested that the cattle belonged to men of position, and, in faith! he was not far wrong. See the crest?"

In the shimmer of light Ambrose could just make out the design on the harness. Then he felt hastily in his own saddle-bag. The precious packet of wet moss was safe.

"Arnheim!" he cried. "Arnheim in that very house yonder! It seems to me, gentlemen, that we have had a narrow escape."

"And that our mission is understood," Eric smiled.

"Also that Wandering Will's ready wit saved us," said Ambrose. "Hark! We had better press on before yonder brawl gets worse."

There was a roar as of angry bees inside the inn, stamps and yells, and the sound of blows, as the three cavaliers dashed into the darkness.

It was long past noon when the three drew rein before the 'King's Arms,' in Rems high-street. As they came into the city they did not fail to notice the strange feverishness that seemed to possess the town like a plague. The streets were thronged with people moving to and fro in twos and threes, partly as if for protection, and partly as if furtively suspicious of everybody else.

They were troubled times, and strange rumours were in the air. The Queen's malady and the story of the painted red roses was on every lip. Arnheim was coming down from the hills, like one of his wolves, with twenty thousand swords behind him. The Court and ministers had turned against Queen Agnes, and were only awaiting the signal to declare themselves. D'Arolles' agents were everywhere, and they had circulated their poisonous reports cunningly.

More than once during the century the cobble-stones of Rems had run red with blood. The citizens were getting sick of intrigue and slaughter. They had only lately seen a young girl succeed to the throne, and they had hoped for peace and tranquillity to develop their prosperous trades.

They were all for the Queen, but they did not know her well enough, as yet, to carry their loyalty to the sword's point. If D'Arolles came down from the hills sufficiently strong to carry the city, the city would submit. Not that they loved Arnheim, but anything was better than that hideous slaughter.

All the same, every man, woman, and child sported the red rose. D'Arolles, ruling the city as a blight, and cursed by every citizen under his breath, had ordered it so. If only they could be rid of the dark, little, sardonic man and his constant intrigues! All bowed down to him, all feared him, as he was trusted by none. All the same, those armed rufflers in the narrow streets were his agents, and it was they who stated covertly that the Court and ministry were going to throw off the yoke to-day and appear at the grand Cathedral service wearing the white rose of Arnheim. And if they did, those assumed friends of the Queen swore to massacre the lot, including his Eminence Cardinal Marmaison, on the very altar-steps. No wonder that Rems was uneasy and restless; no wonder that they would have heard of D'Arolles' dissolution with complacent satisfaction. The trap might be set for them, after all.

A score of armed ruffians were swaggering before the 'King's Arms' as the three dismounted. More than one of them glanced curiously at the black barbs. But the three sported the crimson roses on their breasts, and no questions were asked, nothing more than insolent stares on the part of the ruffish crew.

"D'Arolles' lambs to a man," Ambrose muttered. "There will be stiff work for us presently. It would be well to be at the Cathedral early."

"It would be better to line the inner man first," Eric muttered. "It is but sorry work fighting on an empty stomach. Fellow! take these horses and see to them."

Eric swaggered into the hostel, followed by the rest. Here all was quiet enough, for they had the great dining-hall to themselves, and in the mullioned window fared royally on a haunch and a flagon of red wine each, after which they smoked a pipe of Virginia each at leisure.

Meanwhile the crowd outside was increasing. Red roses could be seen on every side. Presently a small cavalcade rode down the centre of the street, the populace making way respectfully and yet with no signs of heartiness or warm greeting.

"Who's the devil's disciple in the centre?" asked Ulric. "The little man with the eye of a hawk and the skin of dirty parchment? By the rood! I should be loth to trust him far."

"D'Arolles himself!" Ambrose said quietly. "Evidently the banquet to ministers is a thing of the past, and he is on the way to the Cathedral. And there goes the Cardinal. Our Lady keep him! He little knows how near he is to death."

"Or D'Arolles, for that matter," Ulric growled, as he touched his rapier.

"Messieurs, the game commences in earnest. If we are going to get a good seat at the play, it seems to me that we had better be up and doing."

"The man in the corner sees most of the game," Ambrose observed. "Our place will be a lowly one, near the north porch."

"And what shall we do there, my cheerful bard?"

"Why, intercept D'Arolles' escape, of course. Stay where we can watch the infernal juggling from start to finish. We will want to see the roses turn from red to white, want to see D'Arolles rush out with simulated horror to tell his armed assassins outside what has happened, so that they may rush in and murder everybody there in the name of Queen Agnes and the sacred call of loyalty. Wait there, my brothers, and stop that part of the tragedy, and—turn the roses from white to red again."

Ambrose's head was flung back, his whole aspect changed. He was no longer the sprightly Court dandy, the squire of dames, the pet of a circle. He spake in ringing tones; his eyes flashed with a strange, grim purpose.

"There is a plan in that clever head," cried Ulric, not without admiration. "Glad am I that you came along, Ambrose."

"What would you have done without me?" Ambrose laughed.

"I' faith!" Ulric confessed frankly, "I do not know. Died with the Queen's name upon our lips—"

"And left D'Arolles to his triumph! We shall see something presently that Time will write in red, large letters in the history of Europe. Allons!"

They swaggered out into the street as if they had no care in the world. Yet their red roses were displayed conspicuously on their doublets, and the rapiers were ready. All Rems seemed to be out of doors to-day—anxious-looking citizens, eager students pushing the mob this way and that, wolfish-eyed men with the brown stains of the hills on their faces, men who seemed ready for anything.

"D'Arolles' parasites, these," Ambrose whispered, "and followers of Arnheim to a man. Their hands will be red presently, or so they think. My faith! it is a poor sort of greeting that waits for her Majesty's ministers to-day."

Through the jostling, pushing crowd a statesman thrust his way. The ministers were greeted with a faint murmur and hostile looks. Small wonder, when the good people of Rems had been told that ere long one and all would be traitors to their Queen. The poison had been poured steadily into willing ears.

The Cathedral was reached at length. In the large open square a dense mass of people had gathered. The lean-flanked men from the hills were well to the fore. Only those invited had entered the Cathedral. Ambrose and Eric and Ulric swaggered past the guard with the easy assumption of invited guests.

There were not more than two hundred guests altogether, but a glance on the part of the adventurers disclose the fact that they constituted the cream of Queen Agnes's following. Without them, she had been a rudderless ship on a stormy ocean; without them, Arnheim might push his way to the throne unaided. And they were doomed every one of them by a plot as infamous as any ever conceived by the Borgia.

The doors closed presently; the organ boomed in the fretted roof, the service commenced. Outside came a rocking, uneasy din, as an angry sea on a rocky coast. Ever and anon could be heard a sound as of the clashing of arms. In the gloomy niche of a high tomb near the great north porch, the adventurers watched and waited. Higher and higher grew the din outside, so that the good old Cardinal paused in his sermon with a gesture of pitiful patience. Ambrose could see the expression in that grand, broad face, he could see the heaving of the shoulders and the fall of the breast. Then he saw more; he saw the red rose over Marmaison's heart change from crimson to drab, to white.

Others had seen it, too, for there was a cry of astonishment. The Cardinal paused and looked down in amazement. He could see white roses everywhere. For a moment hands sought rapiers, for every man fed upon a deep distrust of his neighbour. Each man had been tricked he knew not how, but each deemed the rest to be traitors.

From the great stone pulpit Cardinal Marmaison looked down helplessly. At the same time a slight figure with pale face and gleaming black eyes was hastening to the door—the only man save our adventurers who wore a real red rose on his breast. He reached a hand for the lock, but Ulric had him in a grip of steel.

"Not yet, traitor and murderer!" he hissed. "This is your doing. Your hired assassins wait outside for the signal that the red roses have grown white. And so you would destroy all those who are on the side of our gracious Queen."

"I am D'Arolles," the other said hoarsely. "Out of my way!"

"If you were ten times D'Arolles, and ten times the abandoned scoundrel that you are, no!" Ambrose said. "If you would save your skin, go back."

The Cardinal looked down uneasily from the pulpit.

"Ruffling in the house of God!" he cried. "Shame on you, whoever you are! Surely the fiend has been at work enough here already."

"Help! help!" D'Arolles cried. "There are traitors here! Traitors! traitors!"

Immediately there came a thundering on the doors, the clash of steel, the shrill yells and cries of the hillmen. Ambrose strode up the aisle.

"There is no time to waste!" he screamed. "D'Arolles is the traitor—the arch-traitor, and the most cunning chemist in Europe! It was he who gave you all the red roses so deftly treated that the crimson turned to white on exposure to the air. You are all for the Queen, but the people here have been told that you would dare to come here to-day wearing the white rose of the House of Arnheim. A pack of Arnheim's wolves wait outside to destroy you all; they will point to the white roses on your breasts as their justification, and the people of Rems will hang you in chains. Bah! cannot you see that if this thing is done, Arnheim's path to the throne is clear?"

As Ambrose spoke, his own rose seemed to go out to a pale drab. The other two noted the change in their own badge.

"At the inn last night," Ambrose whispered. "The man in the leathern suit. He must have tampered with my saddle-bag."

A cry from within the Cathedral rose noisy and rampant as the din outside. The big oaken doors were giving under repeated blows.

"No murder here, I beg of you!" the Cardinal cried. "Consider, consider—"

He came down amongst them, his flowing robes rustling. He might as well have addressed a pack of hungry wolves with the quarry in sight.

"D'Arolles!" they cried. "The blood of D'Arolles!"

"I will have no murder here!" Marmaison thundered.

"Then we are all to be murdered here," a voice cried. "D'Arolles, or all of us! He dies!"

A hundred voices took up the echoing cry. From outside came answering yells, half a yard of rapier came through the splintering door. D'Arolles fled hastily, made to fling his body across the altar. He would be safe there. But a nimble-footed gallant headed him off, so that, perforce, he was compelled to fly for the chapel of St. Mark's, with the faint hope of reaching the cloisters beyond.

"Put your poor, faded roses in your pockets, comrades," Ambrose said between his teeth. "I will show you a good use for them presently. We will defend this door. Meanwhile, unless ill befalls us, D'Arolles is doomed. Then we shall know how to act."

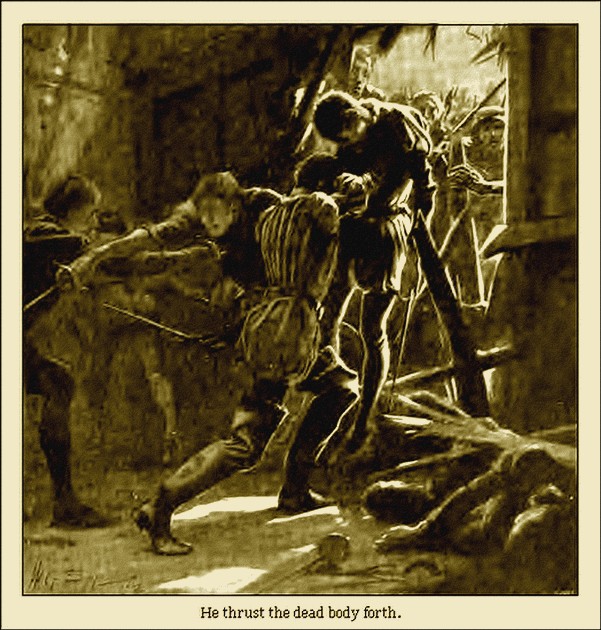

A panel in the door burst like a pistol-shot, and three figures staggered in. Two of them were instantly transfixed, the third rolled upon the floor. He scrambled to his feet and turned with flashing, dazzling blade. A cry of delight burst from Ambrose.

"Arnheim!" he yelled. "The white wolf himself! Engage!"

He fell on the man with incredible dash and fury. Beaten back and taken absolutely by surprise, Arnheim fought but feebly. There was a slip—a stagger—and he went crashing to the ground; Ambrose's weapon passed clean through his heart.

He raised the slim, wiry figure with a grunt of triumph. As another panel of the door gave way, he thrust the dead body forth.

"There is your leader!" he cried. "We have scant use for traitors here. We are all for the Queen, as we shall prove to Rems presently."

A strange lull in the outside tumult followed. The whole thing had been so terrible and so unexpected. The townspeople had fallen back when the news had reached them, hardly knowing what to think. They had been innocent of the fact that Arnheim had been amongst them. Did it not point to the collusion between the dead rebel and D'Arolles? And how could those folk in the Cathedral yonder be traitors when they had struck such a blow for the Queen? And yet they had been told that they should see the white roses for themselves.

Clearly, it was, after all, no concern of theirs. They fell back uneasy and ashamed, leaving Arnheim's followers to fight for the Cathedral. Meanwhile, D'Arolles had reached the cloisters; he turned and kissed his hand to his foes. He was free. Then a fleet shadow seemed to rise from the brown walls, there was a flash and a cry, and D'Arolles lay back with his heart's blood pouring out into a hollow cup in the flag-stones worn by countless feet down the dim avenue of past generations.

"Fate well deserved!" Marmaison murmured. "Praise God he died not in the Cathedral itself! And what are we to do now, gentlemen?"

Ambrose stepped forward. He had come swiftly along at the cry that D'Arolles was no more. He took from his doublet his faded rose.

"They said outside we were not for the Queen," he cried. "They said that they should see the white roses of Arnheim's on our hearts. But the traitor has died so that we can drive the lie back to their lips. My lords, behold the red rose of Queen Agnes!"

He stooped, dipped the pallid flower in the blood of the traitor, shook it, and held it aloft. The thick, crimson fluid dyed it to the deepest crimson. A rocking, thundering murmur of applause followed. Five minutes later, and the red roses glistened in every breast. Then the doors of the Cathedral were flung open, and five-score of gallant gentlemen, with the badge of the Queen over their hearts, emerged.

One instant, and then Rems burst into a mighty cheer. Taken utterly by surprise, leaderless, their cause hopelessly lost, the wolves turned and fled and were seen no more. It was a day of fierce excitement and wild enthusiasm, but the good people of Rems slept that night with a tranquillity they had not known for years.

* * * * *

The Duchess de Mignon avowed herself to be better. Positively she felt able to stand the strain of a walk from her own closet to the studio of the Queen. Her elderly cheeks were painted, her wig reflected every possible credit upon her perruquier, the smile on her red lips was good to see.

The Queen was painting her flowers, her everlasting red roses.

The Duchess chattered gaily. She stopped presently, as hoofs clattered into the court-yard, and after a pause Ambrose and Ulric and Eric entered unannounced. The Duchess was outraged.

"This is an insult!" she said. "And—and when it comes from you, Ambrose—"

"We are from Rems, madam," said Ambrose. "It was as you said. The plot has failed."

"The plot!" the Duchess gasped. "What plot is that?"

"Your Grace's plot with D'Arolles," Ambrose said coolly. "We found the letter in your pocket; we have found other letters on the dead body of D'Arolles."

"The dead—dead body. Oh! I do not understand."

"D'Arolles is dead. The scheme of the juggled roses failed," said Ambrose. "Every man who emerged from Rems Cathedral had a red rose over his heart. Ah! your Grace turns pale. I will tell you presently how that was done. So sure of his position was Arnheim that he dared to lead the attack upon the Cathedral in person. I slew him with my own hand, and I glory in the deed."

The Duchess could say no more. She lay back half swooning in her chair, regarding the three travel-stained cavaliers between her half-closed eyes. The Queen had risen to her feet, pale and trembling, yet with a great resolution shining in her eyes. The easel had fallen to the floor, her foot had torn through the canvas, but she heeded it not.

"You have all fresh red roses," she said. "Show me how it was done."

"With pleasure, your Majesty. The first part you knew; the Duchess knows also. If I have your Majesty's permission to order a bowl of warm water—"

The Queen rang the bell with her own hands.

"I could deny you nothing," she cried. "You have saved my happiness and my throne, and may God bless you for it! Rene, a bowl of warm water here."

The water came, and Ambrose solemnly soaked his rose in the clear fluid. As deliberately and solemnly the others proceeded to treat their flowers in similar fashion; and when the flowers were shaken, they came out a streaky, faded white.

"Will you explain the enigma?" the Queen asked, with a smile.

"I will, madam," Ambrose went on. "All the roses in the Cathedral were white. The wolves were ready for us. Rems had believed the slanders. We caught D'Arolles as he was about to leave the Cathedral. We exposed his scheme; and in the cloisters someone killed that arch-fiend.. .. . When we left the Cathedral, we all wore red roses."

"Still I don't quite see," said the Queen.

"Madam," Ambrose said solemnly, "they were red, and white, and red again, and the last red was the crimson, treacherous blood of a traitor."

He laid the rose at the Queen's feet; so did Ulric and Eric. Her face was pale and agitated; she spoke no word for some time. Then she held out her two hands.

"My friends," she said brokenly. "My friends, if ever I could—"

"Madam," Ambrose said shortly—"madam, the Duchess de Mignon has swooned."