DESPITE the bitter blight of it, a little knot of curious passengers stepped out into the corridor to see what was the matter. The biting cold struck them like a blow, a flurry of snow lashed and stung. Overhead the clouds were hurrying onwards, the white battalions came streaming down the gale, the pine trees rocked and swayed before the force of it. The autocratic guard, master of the train as absolutely as a captain on board his own ship, waved the eager questions on one side.

"There's nothing the matter at all," he said, "and if you want something in the way of a snow-up, I guess I can't give it you. Fact is, the driver saw a man lying on the track, and he sorter pulled up. We've taken him on board now, and a doctor is setting his leg. And that's all!"

The passengers were glad enough to get back to the warmth and comfort of the train, and Pete Morran himself was beginning to conclude that there was something in life, after all. He lay there on a heap of cushions, his teeth set and clenched, and a grey pallor under his tan, as the doctor worked away at his injured limb.

"Calculate I'm all right now," he said presently, "but it was just a chance. My horse died under me, and I slipped in crossing one of these trestle bridges, and bust that darned old limb. Much as I could do to get on the track, with the off-chance of holding up your express. But it came off all right, and it looks as if luck was turning the glad eye on me. Happen that Mrs. Bruce Evershed is on the train, and I guess the glad eye is fairly winking at me."

"Oh, I'll go and see," the doctor said good-naturedly. "Yes, you can have a pipe, if you like, but no whisky."

Pete accepted the situation with philosophy. He seemed particularly anxious to see Mrs. Bruce Evershed without delay.

"I guess she's on the train," he said. "I had a letter from my little girl to say that she and the missis were travelling West to-day on the North-Eastern Express, and my intention was to board the car at Overton. Then I got this bust, and I had to take all the chances that were lying around."

Mrs. Bruce Evershed, small and dainty and alluring, and a perfect picture of graceful beauty, looked up from her snug nest of furs as the doctor addressed her. She seemed to be the last word in luxury and extravagance. It would have been hard to picture her in any other attitude besides that of the ballroom and the theatre. Yet with it all there was just a suggestion of power in her eyes and the firm lines of her mouth. Her beauty was slightly marred by her petulant expression, which had in it some hint of pathos and unhappiness. She suggested a woman who was trying to get away from herself, a woman bored and satiated with the sweets of life, and hungry for a more healthy atmosphere.

"What is the matter?" she asked.

"Well, I hardly like to trouble you," the doctor apologised, "but there's a man in one of the brake vans who is asking for you. He was lying on the track when we pulled up and took him on board. He has sustained a nasty fracture of the right leg. I think his name is Pete Morran."

The bored, discontented look was wiped from Mrs. Evershed's face as if a sponge had been passed over it. Her brown eyes grew alert and eager. She threw aside her costly furs and prepared to follow.

"This is very startling," she said. "The man you speak of is my maid's father. What is he doing here? But perhaps I had better go and see."

Pete greeted the dainty figure, with the brown eyes and sunny hair, with a broad smile of the friendliest description. Mrs. Evershed held out a hand to him that looked like one of the snowflakes on the window as it lay in his brown fist.

"I am glad to see you, Pete," she said. Her voice trembled suspiciously as she spoke. "You are like a link with the past. But tell me, is there anything wrong?"

"Guess we will come to that presently," Pete said. "If you are under the impression that I'm out looking for you—well, you've guessed it first time, because I am."

"Did—did he send for me?"

"Well, I can't go so far as to say that. But he wants you, and cruel bad, too. You see, I heard from my little girl that you were on your way to England on this train, and I concluded to chip in at Overton. Then I threw up against this little trouble, and had to call a fresh deal. You see, at Overton I expected not only to meet you, but to get help."

"Help? Pete, you frighten me! Don't tell me that there is anything wrong with Bruce. If he died—"

"Oh, I guess it isn't so bad as that," Pete said cheerfully. "But he's in danger. You see, him and me we were mining up the Sierras—same old spot where you and him had that honeymoon of yours two years ago."

Mrs. Evershed sighed gently. She had good reason to remember her solitary six months in a mining camp. It all rose vividly to her eyes now. Put her on the right track, and she could have found her way to the camp blindfold.

"Oh, do go on!" she said impatiently.

"Well, there was him and me alone together, and we'd struck it real rich. We buried the stuff in the floor of the tent until we was fairly rocked asleep on a gold mine. And some of those galoots down Red Creek way found it out, and there were we all alone, on the chance of being murdered in our beds. But, after all, there were two of us, and we were armed, and there never was any real grit in that lot. They didn't come out in the open and fight; they just waited for their chance, like a set of cowardly vultures. Then your old man he gets down with an attack of malaria, and I tell you I was hard put to it, what with the cooking and the watching, and one thing and another. And old Bruce he says to me: 'Pete, lad, you've got to go out and get some reinforcements. You're pretty tough, but you can't stand the strain much longer.' And I figured it all out—I figured it as I could get up the reserves in about thirty hours. And we laid a little trap for 'em. We made it look as if we'd cleared out altogether. I fed Bruce up and kinder buried him under half a ton of hay in the corner of the tent, and let the snow drift in so that the place looked fair deserted. There wasn't any smoke, and there didn't appear to be any food, and I guess I played it up on those chaps properly. Then again perhaps I didn't. They might have smelt the trick, and they might at this moment be giving your old man—But I don't like to think of that."

"Oh, this is dreadful!" Mrs. Evershed cried. "You ought to have been back there by this time. What am I to do? The idea of my husband lying there at the mercy of those ruffians drives me mad, and you are useless for the present. Tell me what I can do. I would go myself now—I'd ride every inch of the way alone—if I thought that I could save him."

"I believe you would," Pete said admiringly. "Now, it's no use worrying anybody here. I guess there's nobody on the train who's made of the right stuff for our purpose. There's no help for it, Mrs. Bruce. But here am I like a darned great log, more in the way than anything else. Now, you get off the train at Overton and tell this little yarn to the station hands. It's only twenty miles up the valley from here, and a good horse will get you through before dark."

Mrs. Evershed set her little teeth together.

"I'll go," she said. "I'll find Elsie, and change my clothing at once. Everything necessary is in my baggage. But you must stay on the train and wait for us at the other end. When I start for England, I shall take my husband with me."

"Bully for you!" Pete cried. "That's the best I've heard for many a day, not but what I shall miss him, for a better pard no man could ever wish for. But you've come first, and you always did. And he just aches for you as much as ever. And if you haven't greatly changed yourself—"

"I shall never change, Pete," Mrs. Evershed said simply.

"Then you go to him, and this darned old broken leg of mine will be a blessing in disguise. I'm a plain man and not much of a scholar, but when you live all alone like I do, you learn to think. And he treated you in the right way. And I bet a dollar that you'd be the first to admit it."

Mrs. Evershed held out her hand without a reply. There was something like a frown upon her forehead, and in her eyes a blend of laughter and tears. All the listlessness and languor had left her now; indeed, it might have been a different woman who stepped out on to the howling platform dressed for a perilous journey through the snow. She had been through all this kind of thing before, and her heart was full of courage despite the cold and the stinging lash of the gale in her face. Just for a moment she was conscious of a sense of desolation as the express disappeared in the white, whirling mists.

There was cold comfort here, too. There had been trouble somewhere down the line, and one solitary express man remained in the station. He looked at Grace Evershed with a certain rugged pity in his eyes.

"Mean to say you're going alone?" he asked.

"If I have to," Grace said between her teeth.

"Well, I calculate it will have to be just that way. So far as I know, I'm the only thing that walks on two legs within ten miles of this location. I'd come if I could, but that means the wreck of a train or two. I can find you a horse and a saddle and a bridle. You can have a couple of guns, too, but I guess they won't be much use to you."

"Well, I guess they would," Mrs. Evershed snapped. "I calculate that I'm pretty useful with a revolver."

She set out presently, armed for the fray. She was beginning to realise the peril and danger that lay before her. And yet only an hour or two ago she had lain snug and warm in her furs, with no drear prospect like this before her. As she rode along, with the white flurry raging around her, her mind was busy with the past. She remembered the time when she had first met Bruce; she recalled to mind his peculiar views on the subject of women and their duty to the world. Until she and Bruce had first come together, she had lived a frivolous, selfish life—the only child of a doting father, who had left her more money than was good for any single girl to possess.

She had never meant to marry Evershed, though she admired his courage and his manliness and that strong, resolute face of his. She was never going to call any man master. And then, somehow, it came about that she did marry him, and from that moment the trouble began. Not that he ever upbraided her—there were no 'scenes' in the vulgar sense of the word—but his brow grew darker, and he became more silent as the days went on, until the project for a long trip to the Sierras came up. Grace was jaded and tired with the brilliant social whirl, and she clutched eagerly at the notion. She would have started out with a retinue of servants and all the pampered luxury of her clan, but Evershed had put his foot on that. She found herself roughing it as a daughter of the soil would have done. She found herself rising at dawn, washing and cooking and doing all the menial work of the household. She found herself clad entirely in homespuns, cut off, as it seemed, ten thousand miles from civilisation, with a taskmaster of a husband who worked her like a slave. She had not as yet learnt to face the solitude of the woods. She had all the town-bred girl's horror of the wild solitude and Nature unconfined. She would have turned her back upon it had she dared. But Evershed had refused to accompany her; he refused to turn his face towards civilisation, and if she wanted to go back to the other butterflies, she must find her way there unaided.

It was a somewhat grim and cruel plot which Evershed had evolved as a means of working out his wife's salvation. He made no disguise of what he had done; there was no pretence about it whatever. And, if Grace did not like it, she could go. There were days and weeks together when husband and wife hardly spoke, and when Pete Morran was like a godsend to both of them. And despite her wild rebellion against Fate, Grace Evershed was gradually falling under the fascination of snow and pine and glorious air, and all that goes to the making of a perfect country. She had lost all her lassitude and boredom. There was elasticity in her limbs, and joy in the knowledge of her strength. And there came a time when she could hunt and shoot and fish with the best of them—a time when she could have saddled her own pony and ridden off home by way of Overton without a qualm. But if Evershed had his pride, so also had she found her own. She had promised to come for a year, and she would see it out to the bitter end. Her husband should never brand her as a coward. And gradually, too, she began to see that Evershed was right. There came a time when she could no longer disguise from herself that she owed a debt of gratitude to Bruce for teaching her how to live. And there came a time, too, when she was glad, not perhaps that she had married him, but glad that he belonged to her, and that no other woman in the world could possess him.

But, all the same, at the end of the year she rode away without a word of farewell or even the intimation that she was going. Her year was over and the lesson was finished. Probably she would never look upon Bruce Evershed again. She tried to persuade herself that it did not in the least matter. But that attitude had been abandoned long ago. She stood face to face with herself and argued the matter out calmly. She loved Evershed, and she knew now that she had given him her heart from the first. She had good health and good looks and unlimited means, but she would have cheerfully bartered these to feel Evershed's arms about her and his lips on hers. If she could only find a way, if she could only provide herself with some bright and shining weapon wherewith to break down the barriers of pride, the day was won. And Pete had been quite right—she loved Bruce, and Bruce loved her, and the rest of the world mattered nothing.

And lo and behold, here was the weapon in her hand! Every step of the way was taking her nearer and nearer to her happiness. But would she be in time? That was the question which was racking her. Even under the mantle of snow she could recognise the outline of familiar landmarks. She drew a long, deep breath as the little camp came in sight.

Pete had told her to expect nothing but solitude and desolation. But here were fresh footprints in the snow; a thin wreath of smoke whirled and drifted in the tempest—there was a fire in the tent, beyond a doubt. In the pines behind the tent Grace could see three horses tethered. Assuredly the vultures were getting closer. Had they been bold enough to attack their prey? she wondered. A ribald laugh came to her ears down the gale. She dismounted and tethered her own horse, then crept round to the back of the tent and unhobbled the other three. The half-broken ponies broke into a gallop and disappeared behind the white, whirling curtain of snow.

There were three men in the tent, no doubt, for Grace could hear them talking eagerly. She gave a little gasp of thankfulness as she recognised the voice of her husband. It seemed a little weak and tired, but there was no note of surrender in it.

"I tell you no," Evershed was saying. "You can kill me if you like, but you'll benefit nothing by that. You'd never get from me where the stuff might be hidden. Besides, you don't know for a fact that it is hidden. Do you suppose that Pete went away and left me here without taking something along with him?"

"Oh, that's all very well," one of the other men exclaimed, "but you don't kid us with a story like that. Now, see here, Mister Evershed. We've got you properly whacked. Pete may come back to-morrow, and, on the other hand, he mayn't come back at all. If this storm makes good, it'll be days before the trail's open again. And you've got no food, and you ain't likely to get any unless it comes from us. We don't want to let you starve, but, seeing as you've got the rocks, you must pay for the tucker."

"And pay handsomely, too," the second man growled.

"You're a fine, soft-hearted lot," a third voice broke in. "What's the good of throwing away chances like this? Our game is to get the stuff and clear out before the storm begins in earnest. If he won't speak, perish me if I wouldn't make him. Take him up and roast him. Tie him up before the fire till his clothes scorch on his back. He'll open his mouth wide enough then, I'll promise you. Anybody'd think you were a lot of women!"

The other men growled ominously. It was plain enough that their comrade's suggestion was finding a certain amount of favour in their eyes.

"D'you hear that, Mister Evershed?" the leader asked. "D'you tumble to what Jim was saying? Because I'm game if Red Head here likes to join up. Here, Jim, go out and get some more firewood. There's a pile of dry stuff outside."

"You'll get nothing out of me, you cowardly blackguards!" Evershed cried. "Torture me if you like, but you shall never make me speak. And if you think—"

Evershed broke off abruptly, for the two men were upon him, and he wanted all his strength for the struggle. Weak and spent as he was, he made a fair fight of it, but he was bound at length and dragged to the centre of the tent. It seemed to Grace listening outside that she had come just in the nick of time. There was no fear in her heart, no wild prayer for assistance escaped her lips; she was not even conscious of the cold which was piercing her through and through. But she would have to proceed warily, or her aid and the revolver in her hand might prove useless. There was a second revolver in her pocket, and she had twelve shots in all. If her hand had not lost its cunning, she would know how to use them. It was long odds, too, that these ruffians were not armed. They had come down in this cowardly fashion, feeling sure that Evershed was too weak and ill to put up any sort of a fight. By this time their weapons were, no doubt, far down the valley in the holsters of the stampeded horses.

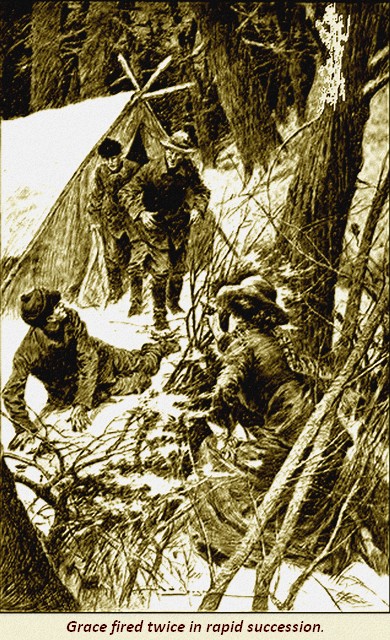

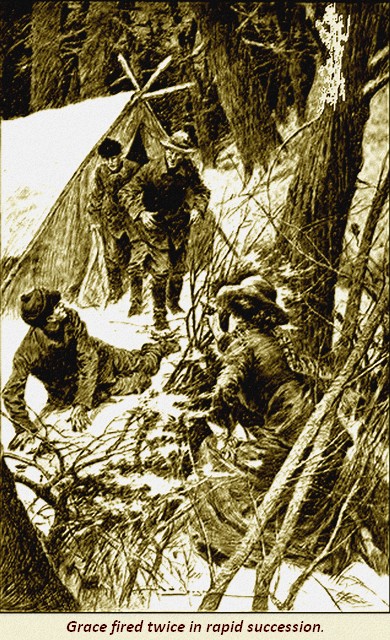

Grace Evershed crept a few yards away, and crouched down behind a mass of undergrowth covered in snow. From here she could watch the movements of the three desperadoes actually inside the tent. She saw the man who had been addressed as Jim come out, presumably with the object of collecting firewood. He stood there for a moment clear-cut as a cameo against a bank of snow. Grace raised the revolver and fired. She saw the man throw up his hands, she heard the yell of execration that rose from his lips as he collapsed in the snow. She had not killed him—she had not the slightest intention of doing so. She had aimed carefully just below the thigh, and she knew that she had broken the ruffian's leg as surely as if a doctor had told her so.

"I'm shot! I'm shot!" the ruffian screamed. "Get a move on you, boys, or we're done for! Where are the guns?"

"With the ponies," a hoarse voice came from inside the tent. "What's up there? You, Jim, what's wrong?"

But Jim answered never a word. He lay there groaning in the snow, absolutely incapable of further mischief. As the other two men rushed to the door of the tent, Grace fired twice in rapid succession. But she was not firing to kill now; she had thought the whole thing out calmly and collectedly. It might be days before relief came to their aid from Overton; the snow might lie deep and the trail be wiped out. If she wounded any more of these rascals, she would have to tend them, and have them on her hands, and, for aught she knew, the tent was none too well provisioned.

There was no occasion for further strategy. The trio were only too anxious to get away out of the zone of the deadly fire. With oaths loud and deep, it dawned upon them that the ponies were gone.

"It's an ambush!" the leader groaned. "It's all over with us, boys. Better put up your hands."

They stood there with hands uplifted, looking dejectedly miserable in the falling snow. But no answering voice bade them surrender, no further shots broke the silence. The stillness and the uncertainty of it all was perhaps more terrible than a volley of shots would have been.

Gradually their hands dropped, and presently, from her hiding-place, Grace could see two of the ruffians moving slowly away, carrying their wounded comrade with them. She had no fear that they would return; they would never risk the unseen danger again. Her heart was beating fast as she hurried to the tent and let down the flap behind her. Evershed lay bound upon the floor, his back towards her. She drew her hunting knife from its sheath and cut the raw-hide thongs. Evershed scrambled painfully to his feet.

"That was a close call," he gasped. "Those shots came just in time. I'm infinitely obliged to you. Why, it's a woman!"

"And one you have met before, Bruce."

"Grace!" he cried. "Now, I wonder what guardian angel sent you here just in the nick of time? Do you mean to say you came—"

His voice trailed away to a whisper. He was ill and weak, but the smile on his face and the look in his eyes was enough for Grace. He was glad, frankly and undisguisedly glad, to see her. On the impulse of the moment he stretched out his hands, and she snatched at them before he had time to withdraw them.

"Speak to me like that," she said. "Look at me as you are looking now, and I shall have courage to proceed. I don't want my pride to get the best of me now. Because Pete was right, Bruce. He said that you loved me and I loved you, and that we ought never to have parted. Because it's all beautifully true. I tried to make myself believe that it wasn't, but I was deceiving myself all the time. It has all turned out like some delightful romance. Pete broke his leg, and he managed to stop the train that I was on. Then he told me everything. He told me the danger you were in here, and, because there was no one to help me, I came alone. And in my heart of hearts I was glad that I was alone. And I feel proud of what I have done. It is the best way I can find of showing you how sorry I am. And I'm not going to ask you to forgive me, because you love me still, and it is not necessary."

"Oh, I shall wake up presently!" Evershed cried. "It's like some beautiful dream that comes to one during an illness. And do you really mean to say that you've come back here to stay?"

She reached her arms about his neck and laid her cheek lovingly against his.

"I've been longing for the chance ever since we parted," she confessed. "I'm quite cured, Bruce. I want nothing better than to be a good wife. That will be happiness enough for me. And now let me make you comfortable. Let me cook your food and make your coffee as I used to. Are there plenty of provisions? Splendid! So that we shall be quite right till help comes. And, do you know, I feel as if I was just beginning life to-day?"