APART from numerous novels, most of which are accessible on-line at Project Gutenberg Australia and Roy Glashan's Library, Fred M. White published some 300 short stories. Many of these were written in the form of series about the same character or group of characters. PGA/RGL has already published e-book editions of those series currently available in digital form.

The present 17-volume edition of e-books is the first attempt to offer the reader a more-or-less comprehensive collection of Fred M. White's other short stories. These were harvested from a wide range of Internet resources and have already been published individually at Project Gutenberg Australia, in many cases with digitally-enhanced illustrations from the original medium of publication.

From the bibliographic information preceding each story, the reader will notice that many of them were extracted from newspapers published in Australia and New Zealand. Credit for preparing e-texts of these and numerous other stories included in this collection goes to Lyn and Maurie Mulcahy, who contributed them to PGA in the course of a long and on-going collaboration.

The stories included in the present collection are presented chronologically according to the publication date of the medium from which they were extracted. Since the stories from Australia and New Zealand presumably made their first appearance in British or American periodicals, the order in which they are given here does not correspond to the actual order of first publication.

This collection contains some 170 stories, but a lot more of Fred M. White's short fiction was still unobtainable at the time of compilation (March 2013). Information about the "missing stories" is given in a bibliographic note at the end of this volume. Perhaps they can be included in supplemental volumes at a later date.

Good reading!

Heaven and earth seemed blended together in a great whirling wheel. Nurse Clare was conscious of a faint smell of burning wood; in a dreamy kind of way she sat up, and asked what was the matter. Then it came back to her that there had been an accident, and that she was not in the least hurt. The carriage had run off the rails, had pitched sideways down a sloping bank, the feeble oil lamp was out, one frosty star indicated the angled window and the serene silence beyond.

Nurse Clare's first thought was for her patient. A dim black bundle loomed opposite her. The resolute-looking, clear-eyed nurse was herself again. She fumbled for the silver match-box at the end of her chatelaine, and struck a vesta. The carriage had fallen over at an angle of forty-five, the dark bundle opposite with a smaller bundle in its arms was fast asleep.

"There has been an accident," Nurse Clare said. "Our slip coach has run off the line. I haven't the remotest idea where we are, but I fancy that we have the coach to ourselves."

"And I slept through it," the other woman said. "I was utterly worn out. I was up all the night with my boy."

She hugged the bundle in her arms closer.

A few hours before these women had been strangers. They had drifted together half-way through a long railway journey, and gradually the story had been told. It was a tale of struggle and misfortune, a runaway match, and a stern, unforgiving father. Then, when things had been getting better, the young husband had been stricken down with smallpox, and the young wife's last desperate resource was a distant relative in the West of England.

The slip coach had fallen clear of the line. Clearly there was nobody else in it. And there was comfort behind that distant red gleam. Nurse Clare sped rapidly along the sleepers till she could see the great crimson star directly overhead, and the outline of a signal box beneath it.

"There has been an accident," she said. "The slip coach to Longford has gone off the rails. Nobody has been hurt, only I thought—"

A big bearded man came rattling down the stairway.

"I was getting anxious, Miss," he said. "My mate, who has just gone off duty, is telegraphing for assistance. Can I do anything?"

"We must make use of your box for the present," the nurse said. "Anything is better than the railway carriage. Is not Grinstead Priory close by?"

"It's no use you going over to Grinstead Priory," the big man said. "If you crawled up the drive at the last gasp it 'ud just please Squire to set his dogs on you and drive you away."

"That poor little body isn't going to have a case of pneumonia on her hands if I can help it," said Nurse Clare. "And as to his dogs, why I just love them."

Nurse Clare pushed her way along until she came at length to a deserted lodge, a pair of moss-clad gates leading into the throat of an avenue. By the light of a crescent moon Nurse Clare could make out a big sign, "Beware of the Dogs." There was a deep-mouthed baying not far off.

But Clare had little time to picture what might have been. She was suddenly transformed into a female Daniel in a den of lions. The frosty air boomed with the deep baying of hounds. Clare caught herself thinking of Topsy and Eva and Uncle Tom.

The great brutes raced towards her, howling as they came. Clare's heart gave one great bound, and then seemed to stop still. She was honestly and sincerely afraid now; she had fully expected to hear the huge hall door fly open at the first note of danger. But though lights blazed in every window, the house was ominously still and silent.

The little nurse stood rigidly there as the great hounds bounded towards here.

"Come here," Clare commanded. "Come here, sir."

The dog came with a shamed gliding movement. The others followed. Clare could see the lights gleaming on rows of polished tooth. She moved very slowly towards the hall door, she laid her fingers resolutely on the handle. Then she staggered into the hall and closed the door swiftly behind her.

Clare marched resolutely into one of the rooms—a noble dining-room with the table laid for dinner. There were covers for at least a score of guests. There were wines of the finest quality, an elegant repast, but everything, to the dishes on the sideboard, cold.

A fire of ripe acacia logs roared up the wide chimney. Before it there sat a man in a deep beehive chair, one foot resting on a stool. He was a grey man, grey as to his hair and eyes, and hard, clean cut features.

"Good evening!" he said in a deep sarcastic note. "I heard you outside. My hearing is good. You don't lack courage."

"If I had," Clare said; "those dogs of yours would have torn me to pieces. You heard me; and yet you took no steps—oh! shameless!"

"I cannot take steps of any kind at present," the man said grimly. "I have sprained my ankle badly. As to servants, there are none in the house. To-morrow a fresh set will arrive. What do you want here?"

Clare explained briefly. She would bring her charge there, whether Grinstead liked it or not.

"Mind you it is contraband of war," he said. "If I were not helpless, I tell you frankly I would have none of this. It is my mood at this time of the year to deck my table out as if I had a house full of people. The last happy time I had before I lost all faith in humanity was a Christmas. You see I have been decorating the walls with holly and the like. That is how I slipped and hurt my ankle. In doing so I displaced those pictures that lie on the floor. I shall be greatly obliged if you will replace them on their hooks. No, no, not that way—the face of the portraits to the wall."

Clare propped the portraits against the table. As her eyes fell upon them she gave a gasp of astonishment. They were beautifully painted, and must have been excellent portraits. Evidently, too, they were mother and daughter.

Clare hurried her companion up the avenue, and into the house, lest some misfortune should baulk her plans. Grinstead looked up grimly; then the black cloud shut down upon his face again. He would have risen only the pain in his foot brought him down again with a groan. Clare's companion stood there, as if dazed by the light.

"My daughter," Grinstead cried. "If you think to fool me like this—"

"Marmion knows me," Mrs. Lestrange said unsteadily. "See how he fawns upon me, and lick's my hand. Father don't send me away to-night. Let me stay here till the morning. Then I will go, and you shall see my face no more. My child—"

"Your child is safe," Nurse Clare said. "We shall stay here to-night. Give the boy to me."

Clare took a pillow from a chair, and laid the boy on it before the fire. His cheeks were rosy and flushed, the streaming firelight glistened upon the shining curls. With a sudden curiosity, Grinstead bent down to look. The big hound growled ominously.

"When I was in South Africa, I met a nurse. Head of a special mission, and called Ursula," said Clare, apropos of nothing apparently. "She was the head of a band of nurses equipped and sent out at her own expense. We all knew there was a sad story somewhere, and we all felt that she was not to blame. But we had to work too hard in those dark days to think of anything but our duty. Still, if ever there was an angel, Sister Ursula was one. Then enteric broke out, and she was one of the first to fall.

"I nursed her for a week, but it was obvious what the end would be, and just before she died she told me something of her history. She had married a man that she respected rather than loved, but he proved a good husband so far that she grew very fond of him in time. Then, some time after her little girl came, she made a discovery. By means of a deliberate lie her husband had separated her from the first love of her heart—"

"Ah," Grinstead said, hoarsely, "so she found that out?"

"Yes, she found it out. And that was why she left her husband and child without a word to go into a kind of convent. It was a dreadful shock to a proud nature like hers, and for years she nursed her sorrow alive. She might have forgiven that man had he sought her out, but he did not do so. And just before she died, before she had time to tell me who she was, she gave me this to give to her husband as a token of forgiveness. I am glad that I can hand it over to him at Christmas time."

From her purse Clare drew a simple wedding ring. "Now what do you think of this man?" Clare went on. "Because his wife leaves him he loses all faith in human nature. He looks upon himself as betrayed. And yet all those years he never thinks of the cruel lie by which he parted a woman from the man of her heart. He had only one point of view, for his own sin he can feel nothing. Why when his daughter gives him a lesson that love is better than all the world besides, he sees nothing in it but another personal grievance."

Grinstead had nothing to say: his sharp tongue was silenced, for all that Clare had said was positively true. He had forgotten that dishonourable lie, he had deliberately ignored everything but his own wrongs. Even after the lapse of years his face flushed as he thought of his wife's feelings when the truth came home to her. It was amazing now to realise that he had never for a moment dreamt that the fault might have been his.

"I should have looked till I found you," Clare said. "As it is I have found you quite by accident. Sir, the play is played out. It is for you to say what situation the curtain shall rise upon."

It was some time before Grinstead spoke. He was cast down and humiliated, a prey to bitter feelings, and yet his heart was lighter than it had been for years. He pointed to the blank pictures on the walls.

"Will you do me a little favour?" he asked. "You were so good as to hang up those portraits for me just now. I shall be very glad if you will please put them in—in a more favourable position."

The words cost Grinstead an effort as Clare could see. Without a word she turned the pictures round and dusted them.

"And now," she said. "We had better see what bedroom accommodation there is for us. I presume there are fires laid upstairs. And when that is all over I will look to your injured ankle. Come along."

She swept Eleanor Lestrange out of the room, leaving Grinstead to his own troubled thoughts. At his feet the boy lay looking up with dreamy eyes. They looked up at him from the floor; they seemed to smile down at him from the walls.

"Ain't you afraid of me?" he said clumsily. The boy rose and climbed on to Grinstead's knees.

"I'm not afraid of anybody," he said, "because everybody loves me."

Clare laid a hand upon Eleanor Lestrange's shoulder and drew her into the shadow. The firelight danced and flickered, and in the centre of it was Grinstead with the boy on his knees and his slim hands in the little fellow's curls.

"Your troubles are over," Clare whispered, "and I fancy I shall be here long enough to see your husband and your father shake hands yet."

And she did.

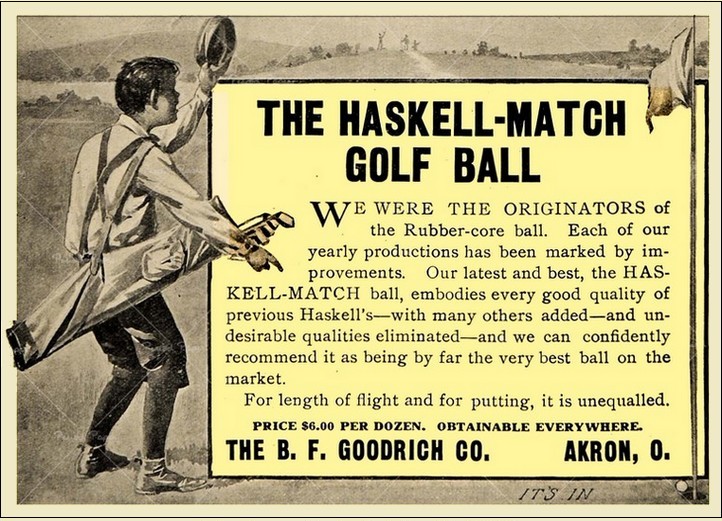

THE members of the Royal Crossboro' Golf Club were suffering from a periodical lack of incidents. For instance, nobody had done any holes "in one" lately, the merits and demerits of the "Haskell"* et hoc had been thoroughly thrashed out, so that the select smoking-room company were actually forced back upon quite mundane matters. The afternoon was too wet and windy even for golf, and the half-dozen members round the fire had finished the usual after-lunch abuse of the Green Committee.

"Nor'-west gale for the last week," growled one. "I suppose that's why we are kept on the back tee at the eighteenth hole. Old Seddon to blame, of course."

"Of course," said another of the smokers. "It means that every ball that's fairly well played falls in the Mole brook, and consequently is carried past Seddon's house and into his private grounds, where he collects them all. He hasn't bought a new ball for years."

One of the fathers of the club, smoking gravely in his favourite armchair, smiled meaningly. There was a deadly feud between Mr. Chorsley aforesaid and the wily Seddon, whose residence was quite close to the home green.

"I've stopped that," Chorsley said. "I had a wire grating fixed across the brook just as it passed through the hedge into Seddon's grounds. No more annexed Haskell's now. Did I ever tell you how Seddon served me the last time we played together in the Spring?"

The assembled company shuffled uneasily. They had all heard the story times out of number, how Seddon had played with his opponent's ball, and declared it to be his own. But then Mr. Chorsley was a real good fellow, and widely hospitable to boot, and the old old story was endured in silence. And Seddon was no favourite in the club.

"It's a strange thing," another member said, thoughtfully. "For the last month Frank Bruce has never made one decent drive over the Mole brook at the last hole. He is playing a better game than he has ever played in his life, and yet every time he comes to the last tee he slices his drive over the boundary into the brook, as it passes into Seddon's property."

"And never misses when he drops another ball down for a second drive," added another member.

"One way of getting round old Seddon," a further member remarked. "It's love for Mary Seddon, the old boy's niece, that upsets Bruce's nerve at the last hole. When he is in sight of the house he is thinking of the unattainable and other things."

"Is that really a fact?" Chorsley asked eagerly.

"Absolutely," the last speaker replied. "And whatever may be the faults of old Seddon, his niece Mary is really a nice girl. She'll have a fair amount of money, too, not that Bruce calculates on that. But Seddon's got a sorry nephew who comes down from the City now and again, and he's trying to force the little girl to marry him."

"Why doesn't Bruce take matters in his own hands?" Chorsley growled.

"Well, he can't quite do that. His prospects are good, and he is a really smart fellow, but as yet his income is small. Seddon has put his foot down. There is to be no more intercourse, nothing till Frank can show a clear income of £500 a year. When that comes Seddon magnanimously offers to withdraw all opposition. So it's long odds on the nephew."

Chorsley nodded thoughtfully. He was an easy going kind-hearted old gentleman, but he had a pretty temper of his own, and he hated Seddon heartily. He would have gone a long way to thwart the miserly man who laid traps for golf balls. His eyes twinkled as he looked into the fire. He began to see his way. He was not yet retired from the stockbroking firm from whence he derived a large portion of his big income.

"You'll see Bruce when he comes down to-night, Partridge," he said. "I wish you'd make up a match with him for me on Saturday, if he has nothing else on. Then you can both come afterwards and have dinner with me."

Partridge promised to arrange the matter if possible, and evidently meant it. Chorsley's little dinners were by no means to be despised. And though Frank Bruce was an infinitely better player than his elderly opponent, and though he was consumed by what looked like a hopeless passion for Mary Seddon, he fixed up the match without the slightest hesitation.

They came along well enough till the last teeing ground was reached. It was an interesting match, for at this point the rivals were all square. Everything depended upon the last hole. Below the tee was a broken sloping ground ending into the tiny but swiftly running Mole brook. Beyond was the fair green course and the red flag fluttering in the distance.

"My honour," said Bruce, as he seemed to be selecting a ball with unusual care. "My drive first. I must try and not miss this one. Latterly I can't manage this hole at all,"

He made his tee carefully, and placed a perfectly white new ball upon it. Mr. Chorsley made as if to get out of the way, and in doing so kicked the ball off the tee, so that it rolled into some heather. With a muttered apology, he replaced the dismantled ball.

"Now go on," he said. "Give me a good lead."

Bruce swung very slowly up, then his driver came down with a smashing force. Away went the ball, not straight across the course, but sliced away to the right well over the boundary fence and down till it hopped into the Mole brook in Seddon's grounds.

"Funny thing, isn't it?" Bruce said without the slightest emotion.

"Very," Chorsley said gravely. "But you'll do better next drive. Of course, you can tee up another ball and play three strokes. Go ahead."

Chorsley got a good drive, and Bruce a beautifully long raking shot. But the handicap was too strong, and he lost the hole by a stroke. He bore his defeat with singular philosophy.

"No use getting out of temper," he said.

"Not a bit," Chorsley chuckled. "See you later on at dinner time. Partridge has to leave early, but don't you hurry. I have a word or two for your private ear afterwards."

A LONG bubbling glass stood at Frank Bruce's elbow, and a long cigar between his teeth. The smoking-room was comfortably and not too brilliantly lighted; the glowing fire invited confidence.

Partridge had departed, and Bruce and his host were alone together. For a long time the former stared thoughtfully into the fire.

"Why don't you make up your mind to marry her in spite of him?" Chorsley asked.

"It wouldn't be fair," Bryce said, in the most natural manner, and as if there had been a long conversation on the subject nearest his heart. "I couldn't afford it yet, and, confound it, Mr. Chorsley, how could you possibly guess what I was thinking about?"

"So what the fellows at the club house say is perfectly true," Chorsley went on coolly. "Old Seddon plays the magnanimous, and what he'll do when you can show a clear £500 a year. Meanwhile, there is a rival in the path."

"Yes, confound him!" Bruce growled.

"Who has the ears of the wicked uncle. This wicked uncle watches the niece so carefully that she can't get a line out of the house, and you can't get a line into it. And yet you can put her on her guard when the rival is coming down, and if you want an interview when you come down here on Saturdays you know how to arrange it, don't you?"

Bruce looked up anxiously, and Chorsley smiled.

"Oh, I'm not going to give you away," he said. "It's one of the smartest tricks I've ever come across, and that is saying a good deal. A young fellow who can invent a dodge like that is certain to get on in the world, and I can give him a good start. Here is a golf ball. It is the one that you first put upon the last tee this morning. When I kicked it off the tee I replaced it with another. I know your secret, young man, and I congratulate you. Go up to the last tee in the morning, and drive that ball off in the way it should be driven, and when you see Miss Seddon at night ask for an interview with her uncle. Tell him you have your £500 a year all right, and, if he is incredulous, give him this letter. Now finish up your cigar, and be off."

* * * * *

At a quarter past nine the following night Frank Bruce was sitting in a secluded part of Mr. Seddon's grounds, and he was not alone. A pretty girl with dark eyes was by his side, and his arm was about her waist.

"I expected your message last night," Mary said.

"Well, I thought I had sent it," Bruce replied. "Mary, our little scheme has been found out. Mr. Chorsley took the marked ball, and substituted another for it."

"And I saw you drive off, and when I picked the ball up it was quite clean," Mary said, "But surely Mr. Chorsley would never have been so ill-natured--"

"Old Chorsley is a brick. And between ourselves, he would give a great deal to put a spoke in your uncle's wheel. On the whole we shall have no occasion to regret--"

An acid voice breaking in on the lovers' sweet converse thought otherwise. The tall, thin man demanded to know why he had been deceived like this, to which Bruce coolly responded that there had been no deception whatever. There was a stipulation as to an income of £500 a year--

"Which remains to be fulfilled," Seddon said, coldly.

"Perhaps when you read this letter you will think otherwise," Bruce said. "It is intended for you."

Seddon tore open the envelope contemptuously. His face changed as he read, and he bit his lip.

"I suppose you are aware of the contents of this letter," he said with an effort. "But, of course you are. In it Mr. Chorsley informs me that he is going out of the firm of Chorsley and Martin, and that the present manager comes in. Therefore you are offered the managership, with good prospects at a salary of £600 a year."

Bruce nodded coolly. But he was absolutely taken by surprise. All the same his enemy was utterly routed. He dropped the letter on the grass, and walked away with his hands behind him. Mary bent over her lover, and kissed him with delighted tears in her eyes.

"Do explain, Frank," she said, rapturously. "Do tell me how it happened."

"When I've seen Chorsley," Bruce muttered, "but not before, because I'm hanged if I know."

"Easiest thing in the world," Chorsley said, as he waved his cigar in front of him. "Why did you always slice it in the same direction? Why did you always get your ball off so clean? Because you were doing it on purpose. Again why? Because the object of your affection was near at hand. You wanted to signal to her. Then it occurred to me that if you wrote a message in blue pencil on a new golf ball, it wouldn't come out for some time. You do so, and you drive that ball into the brook, and Miss Seddon finds it. I got hold of a ball of yours, and I read the message making an appointment. By Jove, a splendid dodge--never heard of better. And so that's the way you managed your love affairs, eh. Well, If you can do so well with one thing you may do well with another, and that's why I gave you the chance of filling the new opening in our office. No, you need not thank me, I shall have a good servant, and I get even with Seddon at the same time. But there will be two things that I prophesy."

"And what are those?" Bruce asked.

"That you will miss no more drives on the last tee," Chorsley chuckled, "and that you will not be so prodigal with your 'rubbers' in the future."

THE little woman clung impulsively to Jim Stacey's hands as if they were buoys in a tempestuous sea and she drowning in the social gulf for want of a friend. And, indeed, Mrs. Arthur Lattimer was in a sorry case, as her pleading eyes would have told a less astute observer than her companion.

As to the scene itself, it was set for comedy rather than tragedy. Down below a new Russian contralto was delighting the ears of Lady Trevor's guests; the rooms were filled with all the best people; the little alcove where Stacey was sitting was a mass of fragrant Parma violets and cool, feathery ferns; the electric lights were demurely shaded; indeed, Lady Trevor always made a point of this discretion in her illuminations. There was no chance for the present of interruption, so that Stacey was in a position to listen to his companion's story without much fear of the inquisitive outsider. Gradually the look of terror began to fade from the grey eyes of Mrs. Arthur Lattimer.

"My dear lady," Stacey said, in his most soothing tones, "I shall have to get you to tell it me all over again. You see, I have been out of town for the last two or three days, and only received your hurried note an hour ago. You will admit that stating a case is not your strong point."

"What did I say?" Mrs. Lattimer asked. "I am half beside myself with trouble. Did I make it quite clear to you that I had lost the great Asturian emerald?"

"I gathered that," Stacey said. "I am also under the impression that the emerald was stolen."

"It was stolen, "Mrs. Lattimer affirmed. "I was wearing it—"

"Wearing it?" Stacey echoed. "Surely that was a little indiscreet. But how came the Empress of Asturia's jewel in your possession at all?"

"I had better explain, "Mrs. Lattimer went on. "As you know perfectly well, my husband is a dealer in precious stones. He is probably the greatest man in this line in Europe. You are also aware that the Empress of Asturia is in London at the present moment. She has a fancy to try to match that priceless stone; in fact, if possible, she wants two more like it. She came very quietly to our house in Mount Street and saw my husband on the subject. Of course, he held out little hope of being able to execute the commission, but he said that he had heard of a couple of likely stones in Venice, and that, if Her Majesty would leave the emerald with him, he would see what he could do. To make a long story short the stone was left with him, and up to three or four days ago was locked away in his safe—a small safe that he keeps in his study."

"Lattimer showed you the stone, of course?"

"I have my husband pretty well in hand," Mrs. Lattimer laughed. "He showed me the emerald the next day, and a sudden fancy to wear it came over me with irresistible force. It was no great matter for me to get possession of the key of the safe. My husband was away, too, for a night, and on Monday evening I went to a bridge party at Rutland House, wearing the emerald as a pin. I was just a little frightened to find my borrowed gem so greatly admired. We were having supper about twelve o'clock—a sort of informal affair at a sideboard in the drawing-room—and I was induced to hand the stone round. Without thinking, I unscrewed it from the pin and stood there laughing and chatting keeping my eyes open all the same."

"Knowing something of the kind of woman who is a professional bridge-player?" Stacey laughed.

"Precisely," Mrs. Lattimer said. "There were one or two present whom I would not trust very far. Well, in some extraordinary way the stone was lost. Nobody seemed to know where it was; nobody would confess to having taken it. I am afraid I lost my head for the moment. I know I said a few hard things; but there it is—that stone is gone, and unless I can recover it by midday to-morrow I am ruined, absolutely ruined."

"Your husband?" Stacey hinted.

"Knows nothing. I have not dared to tell him. I have waited till the last possible moment on chance of the stone being recovered. You see, I stole the key of the safe and made my husband believe that he had lost it. It is a wonderful safe of American make, and no one in London can unpick it. My husband telegraphed to New York to the makers to send a man over, and he arrives by the Celtic to-night. Unless the stone can be found first—"

Stacey nodded sympathetically. He quite appreciated the desperate condition of affairs.

"I see," he said, thoughtfully. "If the stone turns up, you will contrive to find the lost key and restore the gem to its hiding-place. And now I must ask you if you suspect anybody."

The pretty little woman flushed slightly. She glanced about her as if afraid that the Parma violets might become the avenue that leads up to a libel action.

"Yes," she whispered. "It is Mrs. Aubrey Beard."

"Oh!" Stacey muttered. "So the wind sets in that quarter. My dear lady, this is a serious thing. Mrs. Aubrey Beard has a high reputation. She is the wife of a Cabinet Minister, and, so far as I know, has none of the society vices—"

"Oh, hasn't she?" Mrs. Lattimer sneered. "Why, that woman is one of the most inveterate gamblers in London. It is an open secret that her bridge debts amount to over five thousand pounds—at least, they did last night, and I haven't heard that they were paid to—day. But this seems to be news to you?"

"Well, yes," Stacey admitted. "If Beard knew this there would be a separation. Now tell me, what grounds have you for making this accusation?"

"My dear Mr. Stacey, I am making no accusation whatever. I am merely telling you whom I suspect. To begin with, Mrs. Beard hardly touched the stone at all, though I could see her eyes flash strangely when she saw me wearing it. I have very little doubt that she guessed my little deception. You will remember that Mr. Aubrey Beard was in the Diplomatic Service at the Asturian capital, and that his wife would have every opportunity of becoming acquainted with the Royal jewels. At any rate, she hardly touched the gem, and seemed a great deal more interested in a dish of chocolate bon-bons in front of her. She is passionately fond of sweets."

"I suppose, practically, your supper consisted of that kind of thing?" Stacey asked. "Being no men present, you would naturally think very little—"

"Oh, of course," Mrs. Lattimer said, airily. "We had very little else besides a few grapes and a sandwich or two. Mrs. Beard was nibbling at her chocolates up to the very time we left. It was then that she dropped a remark which aroused all my suspicions. She said she hoped that I should find my emerald again, and that if the Empress of Asturia was seen wearing one very like mine I should not accuse her of theft."

"Really, now," Stacey said. "This is most interesting to a society novelist like myself. In other words, Mrs. Beard practically accused you of stealing the very thing that you charge her with appropriating. She let you know quite clearly that she guessed exactly what had happened. It was a hint to you that if you saw anything you would not dare to make it public. You have honoured me with a difficult problem to solve, and I have solved many. Mrs. Beard is a cleverer woman than I imagined; but suppose she has already disposed of the emerald?"

"But she hasn't," Mrs Lattimer whispered, eagerly. "If she had done so, she would have paid her bridge debts. You know how necessary it is to discharge obligations of that kind. I feel quite sure that the emerald still remains in Mrs. Beard's possession."

"Meaning that she has found no way of disposing of it?"

"Not yet. I have had her carefully watched, and I have come to the conclusion that her cousin, Ralph Adamson, is in the conspiracy. Of course, you know he is a great admirer of Mrs. Beard's; there is nothing wrong, but I am certain that he would do anything for her. I know he was at her house for a long time the day before yesterday, and that he subsequently paid a hurried visit to Amsterdam, where, I understand, it is a fairly easy matter to dispose of stolen jewels. If he had been successful with his errand, Mrs. Beard's bridge debts would have been paid by now. But what is the use of our talking like this? You know the whole story; you can see the dreadful position I am in. Is there any possible way of getting me out of the difficulty before to-morrow afternoon?"

"I have worked out some sort of a theme," Stacey said, thoughtfully. "Your letter was very incoherent, but now that I know all the facts I begin to feel sanguine. Tell me—"

"Oh, I will tell you anything. Your very presence gives me courage. I see that you are going to ask me a question of the utmost importance. What is it?"

"It is important," Stacey said, gravely. "I want you to try and remember exactly what sort of bon-bons Mrs. Beard was eating on the night that the robbery took place."

Mrs. Lattimer laughed in a vexed kind of way.

"What a frivolous creature you are!" she said. "As if a trivial thing like that could possibly matter."

"My dear lady," Stacey said, in a deeply impressive manner, "the point is distinctly and emphatically precious. I pray of you not to speak at random. Was it not somewhere in the Far East that the accidental swallowing of a grape—stone changed the destinies of a nation? Think it out carefully."

"You are a most extraordinary man," Mrs. Lattimer said, almost tearfully. "So far as I can recollect, the sweets in question were chocolate fondants filled with almond paste. Yes, I am quite sure that that is a fact, for I remember Mrs. Beard saying that almond paste was her favourite sweet."

"We are getting on," Stacey said. "My education on the head of feminine gastronomy is somewhat limited, but I have a hazy kind of idea that these particular dainties are fairly large in size. They would be nearly as big as my thumb, I suppose?"

"Quite that," Mrs. Lattimer said, gravely.

"Ah! then your humble maker of romances is not to be baffled. My way lies clear before me. Now, one more question. Did I not understand from Lady Trevor that Mrs. Beard is going to put in an appearance here to-night?"

"So I believe," Mrs. Lattimer replied.

"She is giving a dinner to semi—Royalty and will not be here till comparatively late. I feel certain she will come, because I saw Ralph Adamson just now listening to the new contralto."

Stacey rose gaily from his seat and fell to admiring the banks of violets with which the room was lined. He caught Mrs. Lattimer's reproachful eye and smiled.

"À la bonne heure," he said. "Give yourself no further anxiety. The curtain is about to go up, the play will commence. If that emerald is still in the possession of Mrs. Aubrey Beard, I pledge you my word it shall be restored to you before you sleep to-night. Smile as you were wont to smile, and come with me."

THE great contralto had finished her song amidst the tepid applause which passes for enthusiasm in society, and for a moment the proceedings seemed to languish. In the great salon some two hundred of the chosen ones had gathered, waiting like children for someone to amuse them. A social entertainer followed, only to be received and dismissed in chilling silence, which it is to be hoped was somewhat compensated by the size of his cheque. Stacey came cheerfully forward and shook hands with his hostess.

"I began to think you were going to throw me over," she said. "So awfully good of you to offer to come here and amuse these people. Upon my word, society nowadays is worse than a set of school-children. What should we do without our society entertainers? You have such clever ideas! Is it possible that you have a new sensation for us to-night?"

Stacey intimated modestly that it was just on the cards. He noticed the reproachful way with which Mrs. Lattimer was regarding him. He sidled up to her presently.

"It is all part of the system," he said.

"Like Mr. Weller's reduced counsels. It is not when I smile that I am at my joyous zenith. I am here to-night exclusively on your business, and if I do play the clown there will be a good deal of the tragedian behind it. I promise you that there is a large percentage of method in my madness."

There was a murmur among the languid audience, a kind of electric thrill which was in itself a compliment to Stacey. Apart from his literary fame, as an originator of novel and frivolous amusements he had a reputation all his own. There was a good score of men and women present who could have told stories of his marvels, and who could have risen up and called him blessed had it been discreet to do so. There were others present who looked upon Jim Stacey as a mere society scribbler and charlatan, but these only added piquancy to the situation.

At the earnest request of Lady Trevor, Stacey proceeded to do a few simple experiments in the way of thought-reading. An immaculate youth, utterly bored and blasé, lounged up to him and remarked with casual insolence that he had seen this kind of thing just as well done, if not better, at a country fair. Stacey smiled indulgently.

"I dare say," he said. "But, you see, I have apparently mistaken the intellectual level of a portion of my audience. If you like I will endeavour to read your thoughts, provided always that you can concentrate your mind long enough upon any given topic."

"Tell me what is in my pocket, perhaps," the other said. "There is a challenge for you, Stacey."

"Which I accept," Stacey said, promptly.

"If anyone will blindfold me, I am prepared to give a strict account of the contents of Mr. Falconer's pockets, only he must promise me that he will think of nothing else during the whole of the experiment"

There was a ripple and stir amongst the audience, a kaleidoscope whirled and flashed on many-coloured vestments, and a sea of white faces turned in Stacey's direction. One of the ladies present emerged from the foam of fashion and whipped a cambric handkerchief across Stacey's eyes. His victim stood a little way off, so that the performer could just touch the tips of his fingers. There was a long, tense silence before Stacey commenced to speak.

"I begin to see," he said, in a thrilling voice, which began to carry conviction to a section of his audience. Whatever the man might have been, he certainly was a consummate actor.

"I begin to see into some of the secrets of the typical gilded youth of our exclusive society. Imprimis, in the vest-pocket, a gold cigarette-case; the cigarette-case is set with diamonds and bears in one corner two initials which are certainly not the initials of the fortunate owner. Inside the case are three cigarettes and half-a-dozen visiting-cards, which also do not bear the impress of the carrier's autograph. If Mr. Falconer likes I will read out the names printed on those cards, beginning at the bottom and working backwards to the top. The first card is that of a lady——"

"Here, I have had enough of this," Falconer burst out in some confusion. "I don't know who has been playing this trick upon me, but I consider it anything but good form, don't you know."

A ripple of laughter ran over the sea of eager faces as Falconer backed away from the table, his face a healthier and rosier red than it had been for some time past. Stacey's challenge to his victim to complete the experiment was met with a direct negative.

"Then you won't go on?" Stacey said, in his most insinuating manner. "Pity to break it off just at the interesting stage, don't you think? I was just about to tell your friends the story of that cheque in your waistcoat-pocket—"

Something like a cry of dismay broke from the unhappy Falconer, and the brilliant red of his face turned to a ghastly white. As he slipped away, Stacey turned to the audience and inquired if anybody else there would like to try the same experiment. Quite a little knot of men came forward.

"Cannot I induce some of the ladies to give me a chance?" Stacey pleaded. "It seems to me manifestly unfair—"

"Fortunately for us we have no pockets," Lady Trevor cried. "We keep all those things in our conscience. Positively, we shall have to send Mr. Stacey to Coventry if he does not hold his wonderful powers a little more in hand. I dare say there are men present who are so marvellously honourable and pure-minded that they have nothing to disclose. If there are any such here, let them come forward for Mr. Stacey to experiment upon."

"My dear Ada, what would be the use of that?" a frisky dowager shrieked at the top of her voice. "We don't want to sit here and listen to the simple annals of the good young man who died, so to speak. Won't someone kindly come forward—somebody with a terrible past——and let Mr. Stacey reveal the scandal for us?"

A frivolous laugh followed this suggestion, and somebody maliciously suggested that the speaker herself might afford information for many piquant revelations. A tall, military-looking man came forward and suggested a new variation of the interesting séance.

"Wouldn't it be much better," he said, "if we changed possessions with one another and gave Mr. Stacey a chance of guessing who the different articles belong to?"

"Wouldn't it be better," another man remarked, "to drop all this nonsense and proceed to something more rational? After all said and done, if Mr. Stacey can do this, he can forecast where things are hidden at a distance."

"Of course I can," Stacey said, with cheerful assurance. "Would you like to try me? Will somebody be good enough to give me a sheet of paper and envelope? I should prefer to have Lady Trevor's own letter-paper, so that there could be no suggestion of confederacy in the business. Will anybody come forward and write a note for me——only just a few words?"

As Stacey spoke he glanced significantly at Mrs. Lattimer, and indicated the man who was standing by her side. She seemed to understand by instinct exactly what he meant, for as the paper and envelope came along she snatched eagerly for it and placed it in the hands of the man by her side.

"You do it, Mr. Adamson," she said. "We can always trust you, because you are so cool and clear-headed, and if there is anything wrong you can easily detect it."

The tall young man with the dark eyes and waxed moustache shrugged his shoulders and smiled. Someone pushed forward a small table, on which stood an inkstand and a pen. The would-be writer gave Stacey a supercilious glance, and intimated that he was ready to begin.

"That is very good of you," Stacey said.

"Just a few words. Write—'It is not safe where it is. Bring it with you to-night.' No; there is nothing more. Lady Trevor, will you be good enough to hand me that little silver basket of sweetmeats which I see on the china cabinet behind you? All I want now is a small box—a cardboard box, about four inches square."

The whole audience was following the experiment breathlessly by now. It was almost pathetic to see the childlike way with which they gaped at Stacey. They watched him with breathless interest as he folded the note and placed it in the cardboard box. Then he very carefully picked out a chocolate fondant from the silver basket of sweetmeats and gravely placed it inside the box.

"This particular confection is not exactly what I wanted," he said, with the greatest possible solemnity. "I should have preferred a fondant tilled with almond paste. This I imagine to be Russian cream, but no matter. I will now proceed to tie up the box and place a name upon it. I will ask Lady Trevor not to look at the name, but to get one of the footmen to take it to the house for which it is intended. That is all, for the present."

Lady Trevor signalled to a passing servant and intimated that Stacey had best give the box into his custody direct.

"You are to go at once," she said, "and deliver this package at the address written on the outside; but perhaps Mr. Stacey would prefer that you placed it direct into the hands of the person for whom it is intended?"

"That was the idea, "Stacey said. "I shall have to crave your patience for half an hour or so, and, meanwhile, I shall be only too pleased to show you another form of entertainment. Before doing that I should like to have something in the way of supper and a cigarette. Surely Mr. Adamson is not going! Oh, come, seeing that you are part and parcel of my experiment I really cannot permit you to go in this way. Come along with me as far as the supper-room and join me in a glass of champagne and a cigarette."

Adamson turned and Stacey took him in a friendly way by the arm. Once in the hall the latter's manner changed and his face had grown stern. His eyes were hard and brilliant.

"Not yet, my friend," he said. "There are many things I can do, and many things I know which would astonish you if I were disposed to betray the secrets of the prison-house. If you are discreet and silent all will be well, but if you elect to defy me—well, there are certain episodes connected with a period of your life which would be just as well—"

THE supper had been over for some little time, and most of the guests who were not playing bridge or otherwise frivolously engaged had gathered in the salon intent upon seeing the sequel to Stacey's experiment. Mrs. Lattimer sat there with flushed cheeks and glittering eyes. The suggestion of the military-looking guest that an interchange of pockets should be made had been carried out. If this had been intended, as doubtless it was, to give Stacey a fall, it had been a long way from being successful.

He had snatched the handkerchief from his eyes and was just getting accustomed to the glare of the room when his glance met that of Mrs. Lattimer. She turned her head swiftly in the direction of the doorway, where stood a handsome woman, whose cold, beautiful face was watching somewhat critically the scene in front of her. It did not need a second look on Stacey's part to recognise Mrs. Aubrey Beard. He could see, too, that under that cold surface something in the nature of a volcano was raging. He could see that cold, icy bosom heave tempestuously, for the diamonds on her breast flashed and trembled like streams of living fire. Stacey quickly turned and whispered something in the ear of Ralph Adamson. The latter seemed to hesitate a moment; then, with bent head and lips that trembled, disappeared slowly through a doorway leading towards the conservatories. In the same cold, stately way Mrs. Aubrey Beard came forward and languidly asked the source of all this amusement.

Her glance at Stacey was icy enough—indeed, there was no love lost between them. It seemed hard to believe that this placid, emotionless creature could have been the reckless gambler that Mrs. Lattimer had proclaimed her.

"Ridiculous," she said, in her stately way. "It is preposterous to believe that Mr. Stacey could do these things without the aid of a confederate."

"Oh, they have their uses," Stacey said, airily. "For instance, I don't mind admitting now that some of this business to-night has been what I may be allowed to term a game of spoof. I have half-a-dozen friends here to—night who gave me all the information I wanted and acted as my lieutenants, and very well they did it, too, as you all must admit. But it is not all nonsense, as I am prepared to prove, if Mrs. Beard but challenged me."

"Is it worth while?" the fair beauty sneered. "I don't think anybody would accuse me of being Mr. Stacey's confederate. If he can guess—for it could be no more than guesswork —what is in my pocket he is welcome to his triumph."

Stacey's keen eyes blazed for a moment, then he resumed his normal expression. He asked for someone to blindfold him; he stood with the tips of his fingers touching the shoulders of his victim. The flesh, cold as it looked, seemed to burn under his touch.

He could hear the quick indrawing of the woman's breath. Every nerve in her body was quivering.

"I do not see much, "he said, in a dreamy kind of voice. "Nothing but a handkerchief in Mrs. Beard's corsage. But stop! There is a small object wrapped up in that handkerchief—a small cardboard box. I can see through that cardboard box now. Inside is an oblong object, brown and sweet to the taste; it is nothing more or less than a chocolate, an ordinary common chocolate filled with Russian cream; at least, I suppose it is filled with—Russian cream. Good heavens, some of you will remember—"

Stacey paused abruptly and tore the handkerchief from his face. He seemed to be greatly moved by some overpowering emotion; he glanced almost with horror into the eyes of the cold, stately woman opposite. She had not moved, she had not changed, save for a burning spot on either cheek and a peculiar convulsive twitching of her lower lip.

"This is more or less part of my experiment with the chocolate creams," Stacey said. "You will remember that a chocolate cream was the simple object that I placed in the cardboard box which was to be dispatched to an address known only to mysel£ I was challenged to discover a certain object hidden somewhere at a distance, and in my own mind I decided where that object was and what it was. Presently I will show you. Meanwhile, I ask Mrs. Beard to admit that I have been absolutely successful, and to produce the small box which she has wrapped in her handkerchief.

The speaker turned just for a moment and his eyes flashed a stern challenge into those of the woman opposite. Very slowly and reluctantly she placed her hand inside the bosom of her dress and produced a lace handkerchief in which lay the small cardboard box which Stacey had dispatched by hand of the footman. The breathless audience watched Stacey as he opened the box and took therefrom apparently the same bon-bon which he had placed in the receptacle some half-hour before.

"I see you are all utterly mystified," he said. "Indeed, I am quite sure that Mrs. Beard is as mystified as the rest. Before successfully concluding my little comedy I should like to have a few words with Mrs. Beard alone. I flatter myself that Mrs. Beard is just as anxious for a few words with me."

The woman bowed coldly. Not for an instant had she betrayed herself She led the way in the direction of the library, and once there Stacey closed the door. He wasted no time in words; he raised the chocolate fondant to the light and snapped it in two. From the inside there fell a wondrous green shining stone—none other than the famous emerald belonging to the Empress of Asturia. Stacey spoke no word: he stood there waiting for the inevitable explanation. Then Mrs. Beard began to speak.

"You are a wonderful man," she said, hoarsely. Her breath came fast, as if she had been running far. "I stole that emerald the night of the bridge party at Rutland House. I managed to conceal it, without being seen, in that chocolate fondant. I had my bridge debts to pay; I dared not tell my husband. I pass before the world as a cold, unfeeling woman, but my love for my husband has hitherto been the one passion of my life. I will not ask you how you have discovered all these things, for you would not tell me if I did. You seem to have guessed that my cousin, Ralph Adamson, was in the conspiracy, and you are correct. By what means you tricked him into writing those lines to-night, and getting me to place myself red-handed in the lion's jaws, I cannot pretend to understand, but there is the emerald and here is my confession. I have said a great deal for a proud woman like myself; all I ask you to do is to make it as easy for me as you can. If there is any exposure—"

"My dear madam, it is entirely in your hands to say whether there will be exposure or not," Stacey explained. "If you leave it to me,I will show you the way out. Mrs. Lattimer came to me with the facts, and I carefully engineered this little comedy with a view to saving my fair friend's reputation and sparing you a humiliating scandal. Still, it was not fair of you to try and close Mrs. Lattimer's mouth by letting her know that you were aware to whom this magnificent stone really belongs. By doing so you thought to frighten her and place her in such a position that she dare not accuse you of the theft. What we have to do now is to go back to the salon and make the dramatic announcement that I have been entirely successful in the matter of my experiment. If you could smile a little I should be greatly obliged. Yes, that is better. Now let us pretend to be talking upon quite indifferent topics. Anything will do."

There was a sudden hush in the conversation and a rustling of skirts as Stacey and Mrs Beard entered the salon. Mrs. Beard was smiling now; she beamed quite graciously upon her companion, though the brilliant red spots still burnt upon her cheeks like a stain.

"You will all be glad to know that my experiment has been a perfect success," Stacey said. "I was challenged to-night to say where some object was which was hidden at a distance. It is an open secret to you all that a few nights ago Mrs. Lattimer lost a valuable emerald; it occurred to me that the finding of this stone would be a fine trial for me, and incidentally an exceedingly good advertisement. I cannot betray the secrets of the prison-house and tell you the inner significance of the bon-bons, for that would be revealing my occult science. Sufficient to say I divined the hiding-place of the missing stone. It was carried away quite by accident that night in a fold of Mrs. Aubrey Beard's dress. Perhaps she was coming here to bring it back; at least, I will not insult the lady by any other supposition. At any rate, here is the missing emerald. It may have been a case of mental telepathy; it was very strange that it should occur to Mrs. Beard to search the folds of that dress at the very moment when I turned my will-power in the direction of the hiding-place of the stone."

Not a soul there but believed every word that Stacey uttered. His manner was complete and convincing. He turned towards Mrs. Lattimer and pressed the shining jewel into her hand.

"Not a word," he whispered. "Take it all for granted. If there were not so many fools in the world I could not have carried this thing off as I have to-night. I will call upon you to-morrow and explain everything. Meanwhile, go up to Mrs. Beard and thank her. Gush at her—kiss her, if you are not afraid of being frozen. Above all, be discreet and silent."

Stacey turned away and walked in the direction of the refreshment-room. He found Adamson there, moodily smoking.

"The play is over," he said. "The comedy is accomplished, and you will understand that this is emphatically a case where the least that is said is the soonest that is mended."

THE men stood facing each other, the one quick and eager, sanguine as to his eyes behind gold-rimmed glasses, the other bent and twisted with the reflection of some great tragedy on his face. A clock somewhere lazily chimed the half past eleven.

"What do I look like, Brownsden?" the twisted man asked hoarsely. "I know what a marvel you are in the indexing of the emotions. What do I look like?"

"Like a man who has done something years ago and just been found out, Ramsay," the other said. "It is almost a new expression to me, though I did see it once before in South Africa. He was a well-to-do, prosperous man, long married, respected, his crime twenty years old. And he was expecting hourly arrest Strange how those old things come to light. Make no mistake—yours is the face of an honest man. And yet!"

"Wonderful!" Ramsay muttered under his breath. "As a criminal psychologist, you have no equal in the world. It was your marvellous book on the ramifications of the criminal mind that first attracted you to me. And it was my privilege to do you some trifling service "

"To save my life and my reputation. If only I had your scientific knowledge!"

"Yes, yes," Ramsay said impatiently. "If ever I found myself in trouble, you promised to come and help me. Hence my telegram this morning. Brownsden, I am in the deepest distress—nobody but you can save me. Look round you."

The criminal specialist Brownsden looked around accordingly. Ramsay's dining-room in Upper Quadrant, Brighton, was an artistic one. It had evidently been furnished by a scholar and a man of taste. There was a marvellously carved oak sideboard, then a Queen Anne bookcase; a fireplace carved by Grindley Gibbons himself; the electric lights Were demurely shaded, only the flowers looked faded. The artistic reticence of it all struck the proper, soothing, refining chord.

"All mine," Ramsay said almost fiercely. "Gathered together bit by bit, pieced like some perfect old mosaic. It has been the one delight in a hard and gloomy life. All the house is the same. And the name of Dr. Alfred Ramsay is becoming known. Then it is all kicked away by a sudden and unexpected tragedy. Sit down."

Brownsden sat down obediently in a Cromwellian chair upholstered in speaking tapestry. It was his cue to get the other to talk. The deformed figure bobbed up and down over the soft red of the Persian carpet—words began to stream from him.

"I have been here now for four years," he began. "It was a hard struggle at first, but I had only myself to keep, and I managed to pull through. Then my books began to sell, but I did not get many patients—not that they mattered much. I kept to myself, with the result that I know nobody, and nobody here knows me except by name and sight. Yet I was not unhappy. I was making money until a month ago, when a sudden attack of nervous sleeplessness warned me that I was going too far. I decided on a month's cycling in the country—it has been very pleasant this Easter—and I went.

"A week before my departure it struck me as a good idea to let the house furnished, so I put an advertisement in the Morning Post. In reply I received a letter from a gentleman in London. I saw him by appointment, and—to make a long story short—he took the house for a month and paid the rent. Like me, my tenant was a man of the closet, an American, and he wanted a change. I was to leave the house just as it was, and my tenant would find his own servants. I gave my old housekeeper a holiday and started on my vacation.

"At the end of three weeks I was quite myself again, and longing to be in harness once more. Two days ago I was rather pleased to get a telegram from my tenant, saying that he had been called back to the States again by urgent business, and that he was leaving at once. He had sent the key to my agents. I telegraphed to my agents to send for my old housekeeper and explain to her what had happened, and to give her instructions to go home, saying that I would follow to-day. All this seems very bald, but I have not finished yet.

"I came back to-day, expecting no evil. I opened the door with my latch-key and came in here. To my surprise, I found the place dirty, the fire out, the flowers left by my tenant still in the rooms as you see them. Now, this is all so unlike my housekeeper that I was vaguely alarmed. I looked all over the house, finding nobody, until I entered my study and laboratory, which is at the back here. That was half an hour before I sent you my wire. As you are a man with no nerves, I will show you what I found. Come this way."

Brownsden rose and followed without a word. The laboratory and library had evidently been an artist's studio at one time —a large room with a dome-glazed roof. There was no carpet on the floor, the electric lights had not been turned on yet, so that Brownsden almost stumbled over some soft object that lay at his feet. He started back as the room suddenly flooded from the great arc light overhead and his eyes met the object on the floor. It was the body of an old woman in a neat black dress. Her silver hair was dabbled with blood; the scalp had been laid half open by a blow from some sharp instrument; the gnarled, knotted, hard-working hands were vigorously clenched. With an appearance of callousness, Brownsden bent over the body.

"This is your unfortunate housekeeper?" he asked. "How long has she been dead?"

Ramsay controlled himself with an effort; perhaps his companion's manner restrained him.

"I have not dared to. make a close examination," he said. "But there is little doubt that that brutal murder was committed between eighteen and twenty-four hours ago. Every symptom points to that being about the period of the crime."

"You have not discovered anything in the way of a clue, I suppose?"

Ramsay replied that he had not done so; in fact, he had not looked for anything of the kind. He had been too stunned at his discovery to be able to do anything logical. As soon as he had pulled himself together, he had stepped out and despatched his telegram to Brownsden.

"One more question," the latter said, "and that is an important one, as you will admit. Don't you think that it is a serious omission not to call in the police?"

"Well, yes," Ramsay said slowly, as if the words were being dragged from him. "Of course, I thought of that. A man like myself, who knows nobody, and who could not give anything very satisfactory in the way of a personal reference... But seeing that the crime is a day old "

"What does that matter?" Brownsden asked somewhat impatiently. "Of course, your hands are clean enough; one has only to look at the radiation of your eye-pupils to see that. But what with fools of officials and irresponsible cheap journalism--"

"I know, I know. But I wanted to have your views first. I could easily say that I got home at a later hour than was actually the truth; that you came with me--"

The old, strange terror was stealing over the man again, and Brownsden's manner changed. He was in the presence of no common fear; no ordinary case was here, he thought.

"All of which would be very unwise," he said. "Suppose somebody saw you come in? I dare say you rode from the station on your cycle? You did? Of course, you can get out of it by saying that you had no occasion to enter your study till a little time later. Also you would account for not seeing your housekeeper by the suggestion that she had mistaken your instructions. When did your tenant leave?"

"My tenant left at the time stated, or Mrs. Gannett would not be back at all. You need not speculate on my tenant, Brownsden. He was a man of standing; indeed, I met him to discuss terms, so he made the appointment at the American Legation in London. You may be sure that he does not count as a card in the game."

"Then we can rule that out," Brownsden muttered as he bent down to examine the body. "But one thing is quite certain—we must lose no time in sending for the police now. Hallo!"

The speech was broken off by the sharp intaking of the breath. As Ramsay drew near, he saw that Brownsden was gently opening the left hand of the murdered woman. A sharp edge of metal had caught his eye. Very gently he drew three coins from the knotted fingers, three half-crowns that seemed to be fresh from the Mint. On the face of it there was nothing unusual in their discovery, save that the suggestion that the murderer might have been fighting for some such small gain as that, for human life before now has been held more cheap. But there was a further discovery under the keen eye of Brownsden that gave the thing a deeper significance.

"This is very strange," he said, as he moved towards a shaded lamp on the table close by. "Here we have three brand new coins taken from the poor creature's hand, the bloom of the mould is still on them. Three perfect half-crowns with the head of Queen Victoria upon them. New coins fresh from the Mint, with the late Queen's head on them, and dated 1899!"

"Ring them," Ramsay burst out in a hoarse cry; "ring them!"

Brownsden proceeded to do so. But the coins rang true and clear—even the test by weight failed to prove them anything but perfect. Ramsay wiped his damp forehead and sighed in a kind of a subdued way. Brownsden's face was still corrugated in a frown.

"I don't understand it at all," he said. "These are genuine silver half-crowns, with never so much as a scratch on them, and yet dated nearly four years ago. Unless-- Ramsay, what kind of woman was your housekeeper? I mean as regards temperament."

"Hot-tempered and obstinate," Ramsay explained. "Inclined to have her own way. Very literal, too. You see, she had a lot of Scotch blood in her."

"I see. If anybody had come to her after your tenant had gone, to fetch some forgotten thing, she would not have given it without proof of the messenger's veracity, I suppose?"

"Indeed she wouldn't, not if it had been an empty sardine-tin."

"Um, that is quite what I expected. There is a pretty problem here, and I am already beginning to see my way clear. Your tenant departed in a breakneck hurry. Let us assume for the sake of argument that there was some pressing need for this. He either forgets something in his hurry, and somebody else who comes along is after the same thing. He tries to persuade your old housekeeper Gannett to part with that something, and she refuses. Hence the crime."

Ramsay nodded in a vague, unconcerned kind of way. Already Brownsden was on the way to the telephone that hung in a distant corner.

"The police," he explained tentatively. "There must be no hesitation any longer. You see--"

At the same moment the purring ripple of the telephone-bell rang out. Ramsay pulled himself together with an effort and took down the receiver. When he replaced the instrument, there was a particularly sickly green smile on his face.

"You ring up the police and explain for me," he said. "I have to go out at once. It appears that the East Sussex Hospital people are at their wits' ends for a surgeon for a case that came in half an hour ago. I must step round. Do you mind? I begin to wish I had never written that book on brain troubles."

Brownsden averred that he did not mind in the least. It was good to Ramsay to feel the fresh air on his face again. The house-surgeon apologised profoundly—he knew that Dr. Ramsay did not take cases like this as a rule; but operation-surgeons that were up to the particular case like this were few in Brighton, and unfortunately it had been impossible to get anyone of them on the telephone. It was a case of a motor accident. The gentleman had been driving his own car and in some way had come to grief. There was no wound to be seen, nothing to account for the deathlike trance in which the patient lay. Ramsay had forgotten his own troubles for the moment. He would be very pleased to see the patient at once.

The patient lay like a corpse on the bed— to all appearance he was dead. Ramsay's examination was thorough. He turned with a half -smile to the house-surgeon.

"No operation is necessary at all," he said. "There is nothing at all the matter with the brain. What the poor fellow is suffering from is paralysis of the spinal cord, due to the shock; I am prepared to stake my reputation upon it. An application of the battery will be all that is necessary. In three days your patient will be out again. Look here!"

Ramsay raised the lid of the sufferer's right eye. As he did so, he checked an exclamation. In an eager way he raised the lid of the other eye, and a half-puzzled, half-relieved expression crossed his face.

"You have run up against a stone wall?" the house-surgeon suggested.

"Indeed I have not," Ramsay said quickly. "I fancied that I had recognised the patient, but I appear to be mistaken. Try the battery, and let me know the result. Not that I have the least doubt what it will be, The spinal column is not injured; it is merely in a state of suspense. You will not mind if I run away now? I have a very unpleasant task before me."

Something like an hour had elapsed between the time that Ramsay had left Upper Quadrant and his return there. There were lights all over the house, and seated in the hall were two policemen, who sat stolidly nursing their helmets on their knees.

Inspector Swann was in the study, and he had many questions to ask. So far as Ramsay could see, very few of them were to the point. But to the relief of the doctor, no questions were put as to the time when the body was found in the house when the police were sent for. The inspector was puzzled over the matter of the half-crowns, which were apparently genuine. Brownsden stood alone, smiling grimly as Ramsay answered the flood of questions poured over him.

"And now as to this tenant of yours, sir," Swann said. "When did he go away?"

"Probably the day before yesterday," Ramsay replied. "He sent the key to my agents, as you will find on inquiry at their offices; otherwise Mrs. Gannett could not have made ber way into the house—I am quite sure that you will find that she called at my agents' offices and got the key. If you expect to discover anything in that direction, you will be disappointed. But perhaps I had better give you the letter which opened negotiations—I mean the first letter my tenant wrote to me."

Swann nodded approval. All the time a couple of detectives in private clothes were making a thorough search of the house. There was a long French window at the back of the study, leading into a square yard, and here a man was looking with the aid of a lantern. He tapped on the ground, and a hollow sound rang out. Swann's sharp ears caught the clang.

"What's that?" he asked. "Have you any well or anything of that kind?"

"Only the inspection-chamber," Ramsay said carelessly. "You could hardly expect--"

Something between a snarl and a cough came from the detective outside. He pulled up the cover of the chamber and dragged out a square box. It seemed to be heavy, for he staggered with the weight of it as he carried it into the study. Swann looked inquiringly at Ramsay, who shook his head— assuredly the box was no property of his.

"This grows interesting," he said. "I have never seen that box before. What have you there, officer?"

A box full of broken scraps of white metal, a box full of plaster moulds and files, and chemicals of various kinds, some iron discs, and a press were handed out, until the whole contents stood confessed upon the table. The detective grinned and wiped his heated forehead. "The finest coining-plant I've seen, sir," he said; " and I've had some experience, too. Never saw anything so perfect in my life. What shall we do with it, sir?"

Swann was of opinion that a cab had better be called, and the stuff carried away. He took his own departure a little later, with the suggestion that nothing further could be done to-night. He carefully locked up the study and sealed it. He hinted that there was a deeper mystery here than met the eye; he would come again in the morning. Ramsay closed the door behind him and then staggered like a drunken man into the dining-room. With a shaking hand he poured himself out some brandy.

"There is more here than meets the eye," Brownsden quoted from Swann significantly. "You asked me to come down and help you. If you will confide in me--"

"I am going to," Ramsay broke out hoarsely. "I am going to do so. But it is far worse than I anticipated. You spoke a while ago of a man in Africa who lived cleanly for years, and yet whose past rose up against him at a time when—my God! it is my own case all over."

"If you will confide in me," Brownsden repeated, " I dare say that "

"I am going to confide in you," Ramsay whispered. "Great Heavens! the ghastliness of it! For I have served my time—three years for counterfeit coining!"

"THERE you have it," Ramsay said, as Brownsden merely nodded. The half-defiant snarl in his voice was almost pathetic. "Here is my story in a nutshell. I am a gentleman by birth, by education, by instinct. Never mind what the temptation was—under the same circumstances I would do it again. After that I met with this accident, that has crippled me for life; but even that had its compensations, for it indirectly gave me a fresh start in life—under my proper name this time."

"I fancy I see what you are afraid of," Brownsden said.

"Of course you do. I am a solitary man; nobody knows anything about me. In any case, after the death of poor Gannett, my past would be dragged up. That is why I asked you to come here. But the thing is even more hideous than I imagined. The discovery of that coining-plant was a catastrophe that I did not anticipate. Questions will be asked. I shall be invited to clear myself. It is fortunate that owing to my accident that cursed Bertillon prison system cannot be applied to me. None of my old associates would recognise me. And yet the peril to my social and literary name is very great. Can you help me without—without--"

"Letting your name be mentioned?" Brownsden said. "I fancy so. To-morrow you must do nothing and leave everything to me. I am going to London, and you must give me the name of the man who took your house. Be guided entirely by me and think of nothing but your hospital patient. Is it a bad case?"

Ramsay replied that the case was not nearly so bad as it looked. His further services would hardly be required. He was more interested in the fact that the patient's one eye was a blue and the other brown than anything else. Brownsden smiled behind his cigarette.

"Different-coloured eyes, with largish red veins in the whites?" he suggested. "Ah! you need not be surprised. I have made eyes my study as much as anything else, and I have noticed that that peculiarity is common when the eyes are of different colour. Now you had better go to bed. And mind, you are entirely in my hands."

Ramsay gave the desired assurance. He was utterly tired and worn out, and he slept far into the next day. Brownsden seemed equal to the occasion, for he managed to get breakfast of sorts; and he volunteered the statement that he had been out since daylight. Pulling a blind back, Ramsay could see a couple of policemen outside, moving along the idle crowd of curious loafers that collected there from time to time.

"I suppose it is useless to ask if you have done anything?" Ramsay said moodily.

"Well, I have," Brownsden said. "For instance, I am every minute expecting the cabman who drove your tenant, Mr. Walters, to the station from here. Of the two servants who were in the house, I can hear nothing, not even from the domestics next door. It appears they kept themselves to themselves very much indeed."

The cabman came a little later with a little surprise in store. He had been called to Upper Quadrant two days before. He had been called by a grocer close by, who had been requested to send a cab from the rank near him by telephone from Upper Quadrant.

"I presume you went to the station?" Brownsden asked.

"No, I didn't, sir; I didn't go nowhere. I put two bags and a case that looked like one of them typewriters a-top of the cab, and I waited for the gentleman to come out. I hadn't any notion then what I was wanted for. Just as the gentleman got on the step, with his rug over his arm, a motor comes up—regular swagger affair--"

"Stop a minute," Brownsden asked. "Did she look like a racer? Tell me how many men were inside and how they were dressed?"

"She did look like a racer, sir," the cabman went on. "The gents inside had furs and goggles same as they most have on good cars... Recognise 'em again, sir? No, can't say as I could."

"Excellent idea for disguise," Brownsden said half aloud. "Quick way for a man who wanted to get about the country. What happened after that?"

"Well, a few words passed, sir, that I could not hear. Then the bags were transferred to the motor from my cab, and I was told that I wasn't wanted. I got a couple o' bob for my trouble, and there was an end of the matter as far as I was concerned."

Brownsden seemed to be satisfied with this explanation, but he vouchsafed no further information. He hurriedly turned over the pages of a time-table.

"So far, so good," he said. "Now I am going to London. If you take my advice, you will not stir out of the house all day, because I may have to telephone or telegraph you. And don't forget that you are entirely in my hands."

"I could not wish for a more capable man," Ramsay said gratefully.

It was nearly five before the telephone rang out in the startled house, and by instinct Ramsay seemed to know that Brownsden was calling him from London. Brownsden's voice was low and clear, but there was a certain pleased ring about it that the listener liked.

"That you, Ramsay?" the voice asked. "Very good. I'm calling you from an office in Hatton Garden where they deal in raw metals. Before you do anything else, call up the East Sussex Hospital and ask how your patient is. Don't go and see him in any case; even if they ask you to do so, make some excuse. Ring up the hospital now I'll wait."

There was some little difficulty with the Exchange, owing to the main-line trunk connection, but the voice of the house-surgeon was heard at last. His information was a startling confirmation of Ramsay's diagnosis on the night before. The electrical treatment had acted like magic. The patient had so far recovered that he had insisted on leaving the hospital an hour before, though, of course, he was still very white and shaky. The main point was that he had gone off in a cab, presumedly to the Hotel Metropole.

Brownsden heard all this subsequently with somethinglike a chuckle. He would like to know if the Hotel Metropole people had seen a guest arriving answering to the same description. An inquiry elicited the fact that the caravansary people had not.

"All this is excellent," Brownsden called down the long wire. "I was quite right to turn my attention in the direction of your late tenant, Ramsay. The address that your letters went to was merely a place where communications may be addressed at a penny each, and where they are called for. The American Legation has known nobody by the name of Walters. The apparent puzzle that you met him there is quite easy. Any American subject can see the Ambassador by waiting long enough in the anteroom; and your man probably knew that, hence he fixed a certain time to meet you there. After he had seen you, he had only to slip away, telling the porter that he would call again. There is no doubt that you have been the victim of a gang of swindlers."