APART from numerous novels, most of which are accessible on-line at Project Gutenberg Australia and Roy Glashan's Library, Fred M. White published some 300 short stories. Many of these were written in the form of series about the same character or group of characters. PGA/RGL has already published e-book editions of those series currently available in digital form.

The present 17-volume edition of e-books is the first attempt to offer the reader a more-or-less comprehensive collection of Fred M. White's other short stories. These were harvested from a wide range of Internet resources and have already been published individually at Project Gutenberg Australia, in many cases with digitally-enhanced illustrations from the original medium of publication.

From the bibliographic information preceding each story, the reader will notice that many of them were extracted from newspapers published in Australia and New Zealand. Credit for preparing e-texts of these and numerous other stories included in this collection goes to Lyn and Maurie Mulcahy, who contributed them to PGA in the course of a long and on-going collaboration.

The stories included in the present collection are presented chronologically according to the publication date of the medium from which they were extracted. Since the stories from Australia and New Zealand presumably made their first appearance in British or American periodicals, the order in which they are given here does not correspond to the actual order of first publication.

This collection contains some 170 stories, but a lot more of Fred M. White's short fiction was still unobtainable at the time of compilation (March 2013). Information about the "missing stories" is given in a bibliographic note at the end of this volume. Perhaps they can be included in supplemental volumes at a later date.

Good reading!

The North Otago Times, New Zealand, 23 Jun 1890, describes this piece as follows: "Fred M. White contributes to this month's Home Chimes an amusing dissertation on 'A Bad Cold,' and the many means of curing suggested by friends. Here are some of them: All you want is a porous plaster, flannel, medicated soap, gin and soda, and laudanum, mustard and cress, Hudson's extract, eau de Cologne, old brandy, Taunus water, Banting, tracheotomy, sugar pills, vinegar and bran, saffron, extract of ginger, oil of vitriol, prussic acid, lemon kali, Bath, Buxton, Scarborough, sea kale, asparagus, antibilious pills, electricty, Everton toffee. Do everything. Do nothing. Lie in bed for a week. Keep from between the sheets as long an possible. Drink everything. Drink nothing. Eat what you like. Don't eat anything. Stuff yourself. Starve yourself. Anything. Nothing. Semolina, suicide, Burton beer, bigamy, and the use of the globes."

The story is taken from the on-line version of the bound edition of The Gentleman's Magazine, Volume CCLXIX, July-December 1890, at www.archive.org.

IT was getting late: the last omnibus had gone, and the few remaining pedestrians in the Euston Road were hurrying homeward, anxious to leave that dismal thoroughfare behind. The footsteps, gradually growing fainter, seemed to leave a greater desolation, though one man at least appeared to be in no hurry as he strode listessly along, as if space and time were of one accord to him. A tall, powerful figure, with bronzed features and a long brown beard, betrayed the traveller; and, in spite of the moody expression of face, there was a kindly gleam in the keen grey eyes—the air of one who, though he would have been a determined enemy, would doubtless have proved an equally staunch friend.

A neighbouring clock struck twelve, and Lancelot Graham increased his pace; anything was better than the depressing gloom of this dismal thoroughfare, with its appearance of decayed gentility and desolate grimy pretentiousness. But at this moment a smart pull at the pedestrian's coat-tails caused him to turn round sharply, with all his thoughts upon pickpockets bent But what he saw was the figure of a child barring his path, as if intent upon obstructing further progress.

"I'se lost," said the little one simply; "will you please find me."

Graham bent down, so that his face was on a level with the tiny speaker. They were immediately beneath a gas-lamp, and the astonished man, as he gazed carefully at the child, found her regarding him with eyes of preternatural size and gravity. There was not one particle of fear in the small face, in its frame of bright, sunny hair—nothing but the calm resolute command of one who issues orders and expects them to be obeyed: a child quaintly but none the less handsomely dressed, and evidently well cared for and nourished.

Graham pulled at his beard in some perplexity, and looked round with a faint anticipation of finding a policeman. Like most big men, he had a warm corner in his heart for children, and there was something in the tiny mite's imperiousness which attracted him strangely.

"And whose httle girl are you?" he asked, gravely.

"I'se mamma's, and I'se lost, and please will you find me"

"But I have found you, my dear," Graham responded helplessly, but not without an inward laugh at the childish logic.

"Yes, but you haven't found me prop'ly. I want to be found nice, and taked home to mamma, because I'se so dreffly hungry."

The ingenuous speaker was without doubt the child of a refined mother, as her accent and general air betrayed. It was a nice quandary, nevertheless, for a single man, said Lance Graham to himself, considering the hour and the fact of being a prisoner in the hands of an imperious young lady, who not only insisted upon being found, but made a point of that desirable consummation being conducted in an orthodox manner.

"Well, we will see what we can do for you," said Graham, becoming interested as well as amused. "But you must tell me where you live, little one."

She looked at him with quiet scorn, as if such a question from a man was altogether illogical and absurd. But, out of consideration for such lamentable ignorance, the child vouchsafed the desired information.

"Why"—with widely-open blue eyes—"I live with mamma!"

"This is awful," groaned the questioner. "And where does mamma live?"

"Why, she lives with me; we both live together."

Graham leaned against the lamp-post and laughed outright. To a lonely man in London—and Alexander Selkirk in his solitude was no more excluded from his fellows than a stranger in town—the strange conversation was at once pleasant and piquant. When he recovered himself a little, he asked with becoming and respectful gravity for a little information concerning the joint-author of the little blue-eyed maiden's being.

"He's runned away," she replied with a little extra solemnity. "He runned away just before I became a little girl."

Lance became conscious of approaching symptoms of another fit of laughter, only something in the fearless violet eyes checked the rising mirth.

"He must have been a very bad man, then," he observed.

"He runned away," repeated the child, regarding her new-found friend with reproachful gravity, "and mamma loves him, she does."

"And do you love him too, little one?"

"Yes, I love him too. And when I say my prayers I say, 'Please God, bless dear runaway papa, and bring him home again, for Jesus' sake, amen.'"

Graham, hard cynical man of the world as he was, did not laugh again.

A man must be far gone, indeed, if such simple earnestness and touching belief as this cannot move him to the core. All the warmth and love in his battered heart went out to the child in a moment.

"I do not know what to do with you," he observed. "I do not know who your mamma is, but I must look after you, young lady."

"I'se not a young lady; I'se Nelly. Take me home to mamma."

"But I don't know where she is," said Graham forlornly.

"Then take me home to your mamma."

"Confiding," said Graham, laughing again, "not to say com- placent, only unfortunately I don't happen to have one."

"I dess you're too big," said Nelly, with a little nod, and then, as if the whole matter was comfortably settled, "Carry me."

"Suppose I take you home with me?" Graham observed, having quickly abandoned the idea of proceeding to the nearest police-station, "and then we can look for mamma in the morning. I think you had better come with me," he added, raising the light burden in his arms.

"All right," Nelly replied, clasping him lovingly round the neck, and laying her smooth cheek comfortably against his bronzed face. "I fink that will be very nice. Then you can come and see mamma in the morning, and perhaps she will let you be my new papa."

"What about the other one?" asked Graham.

"Oh, then I can have two," replied the little lady, by no means abashed; "we can play at horses together. Where do you live?"

The speaker put this latter question with great abruptness, as children will when they speak of matters quite foreign to the subject under discussion.

"Not very far from here," Lance replied meekly.

"I'se so glad. I'se dreffly hungry. And I like milk for supper."

Mr. Graham smiled at this broad hint, and dutifully promised that the desired refreshment should be forthcoming at any cost.

The walk, enlivened by quaint questions and scraps of childish philosophy, proved to be a short one, and, indeed, from Euston Road to Upper Bedford Place can scarcely be called a long journey. So Graham carried his tiny acquaintance to his room, and installed her in state before the fire, bidding her remain there quietly while he retired to consult his landlady upon the important question of supper.

Little Nelly's remark was not beside the mark, when she confessed to the alarming extent of her appetite, for the bread and milk disappeared with considerable celerity, nor did the imperturbable young lady disdain a plate of biscuits suggested by Graham as a follower. Once the novelty of the situation had worn off, he began to enjoy ihf pleasant sensation, and to note with something deeper than pleasure his visitor's sage remarks and noticeable absence of anything like shyness. When she had concluded her repast, she climbed upon his knee in great content.

"Tell me a tale," she commanded; "a nice one."

"Yes, my darling, certainly," Graham replied, feeling as if he would have attempted to stand on his head, if she had called for that form of entertainment. "What shall I tell you about?"

"Bears. The very, very long one about the three bears."

"I am afraid I can't remember that," Lance returned meekly. "You see, my education has been neglected. If it had been tigers now—"

"Well," said the imperious Nelly, with a sigh of resignation, and perhaps a little in deprecation of such deplorable ignorance, "I dess the bears will have to wait. Only it must be about a real tiger."

Graham, obedient to this request, proceeded to relate a personal adventure in the simplest language at his command. That he should be so doing did not appear to be the least ludicrous. As if he had been a family man, and the child his own, he told the thrilling story.

"I like tales," said Nelly, when at length the thrilling narrative concluded. "Did you ever see a real lion?"

"Often. And now, isn't it time little girls were in bed?"

"But I don't want to go to bed. And I never go till I'se said my prayers."

"Well, say them now, then."

"When I'se a bit gooder. I'se got a naughty think inside me." When the naughty think's gone, then I'll say my prayers."

"But I want to go to bed myself."

"You can't go till I'se gone," Nelly returned conclusivel<. "Tell me all about lions."

"Don't know anything about lions."

"Then take me home to mamma."

"My dear child," said Graham, with a gravity he was far from feeling, "can't you understand that you must wait till morning. They have made you a nice bed, and it's very late for little girls to be up."

"Let me see it. Carry me."

The imperious tones were growing very drowsy. When at length Graham's rubicund, good-natured landlady called him into the room, he stopped in the doorway in silent admiration of perhaps the prettiest picture he had ever seen. With her face fresh and rosy, her fair golden hair twisted round her head, she stood upon the bed and held out a pair of arms invitingly.

"What, not asleep yet?" he asked, "and nearly morning, too."

The old look of reproach crept into the child's sleepy eyes. "Not till I have said my prayers. Take me on your lap while I say them."

Graham placed the little one on his knee, listening reverently to the broken medley of words uttered with the deepest solemnity. Yet every word was distinctly uttered, even to the plea for the absent father, till the listener found himself wondering what kind of man this recalcitrant parent might be. Presently Nelly concluded. "And God bless you," she exclaimed lovingly, accompanying her words with a kiss. "And now I will go to sleep."

* * * * *

WHEN Graham woke next morning he did so with a violent pain at his chest, and a general feeling that his beard was being forcibly torn from his chin. It was early yet, but his tiny visitor was abroad. She had established herself upon the bed, where she was engaged in some juvenile amusement, in which the victim's long beard apparently played an important part in the programme. As he opened his eyes the child laughed merrily. "Don't move," she exclaimed peremtorily; "I'se playing horses. You'se the horse, and these is the reins," and giving utterance to these words, she gave a sharp pull at his cherished hirsute appendage, and recommenced her recreation vigorously.

A man may be passionately fond of children, but when it comes to healthy child lying upon his chest, and a pair of lusty little arms tugging at a sensitive portion of his anatomy, the time has arrived when a little admonition becomes almost necessary.

"Nelly, you are hurting me," Graham cried sharply.

She looked in his face a moment, apparently seeking to know if he spoke with a dual meaning, as children ofttimes do. Then, deciding that he spoke the truth, there came an affectionate reaction in his favour.

"Poor, poor!" she said soothingly, rubbing her cheek against his. "Nelly is a naughty girl, and I'se so sorry."

"You are a good little girl to say you are sorry."

"Give me some sweeties then," Nelly answered promptly. "Whenever I tell mamma I'se sorry she says 'good little girl,' and gives me sweeties."

"Presently, perhaps. And now run away while I dress."

Obedient to this request, the child kissed him again, and after one regretful glance at the beard, and a sigh for the vanished equestrian exercise, jumped from the bed and disappeared. Graham was not, however, destined to be left long in peace over his toilet, which was not more than half completed when Nelly returned again, and seating herself in a chair, watched gravely every movement of this deeply interesting ceremony.

"Isn't you going to shave?" she asked reproachfully, as Graham with a smile indicated that his labour was complete.

"I never shave," he answered. "What would you have to play horses with if I did?"

This practical logic seemed to confound Miss Nelly for a moment, but with the pertinacity worthy of a better cause she replied:

"All gentlemans shave. There is one in our house, and I go to him every morning. I like to see him scrape the white stuff off—I'se dreffly hungry."

But by this time Graham had grown quite accustomed to these startling changes in the flow of Miss Nelly's eloquence, though he could not fail to admit the practical drift of the concluding observation.

"Nelly," he asked seriously, when the healthy appetite had been fully appeased. "Let us go to business. Now, what is mamma's name?"

"Nelly, too," the child replied. "Pass the bread and butter please."

"And you do not know where you live?"

"No. But it isn't far from the stason, where the trains are. I can hear them all day when mamma is out."

"Not a particularly good clue in a place like London," reflected the questioner. "What is mamma like?" he asked. "What does she do?"

"She is very beautiful, beautifuller than me, ever so," she answered reverently. "And she goes out at night—And once she look me. There were a lot of people, whole crowds of them, and when mamma came in her beautiful dress they all seemed very glad to see her, I thought."

Evidently an actress, Graham determined—and some clue, though still a very faint one. Still, by the time breakfast was concluded, he had matured his plan of action. He hailed a passing cab, and drove away with the intention in the first place of visiting the nearest police-station in the neighbourhood of the Euston Road, as the most likely place to glean the information of which he was in search.

"Are we going back to mamma?" Nelly asked as they drove away.

"Yes, darling, if we can find her," Graham replied gravely. He began to comprehend how much the involuntary little guest would be missed. "She must have been terribly anxious about you."

"She will cry then," Nelly observed reflectively. "She often cries at night when I am in bed, and says such funny things. Did your mamma cry when she put you to bed?"

"I can't remember," said Graham carelessly. "I dare say she did, I used to be very naughty at times."

"But big people can't be naughty—only little boys and girls; mamma says so, and she is always right."

"I hope so. What will she say to her naughty little girl?"

"I know," came the confident reply: "she will look at me as if she is going to beat me, then she will cry, like she does when I ask about papa."

But any further confidences were checked by the arrival of the cab at the police-station. The interview was not however entirely satisfactory. A stern-looking but kindly guardian of the peace, replying to Graham's questions, vouchsafed the information that no less than five people had visited the station during the previous night in search of lost children. It was a common occurrence enough, though usually the children were speedily found. In his perplexity Graham suggested that if the officer saw Miss Nelly he might perchance be able give some information; in answer to which the constable shook his head doubtfully. Directly he saw the child his stolid face lightened.

"Bless me, of course I know her!" he exclaimed. "My wife keeps lodging-house, and this young lady's mother lives in the same street. I can give you the address if you like, sir, or I will take charge of her."

Graham demurred to this proposal for two reasons: first, because he felt a strange reluctance in parting with his tiny friend; and, secondly, he felt some curiosity to see the mother.

The house to which he found himself directed was by no means a striking-looking one, nor by any stretch of imagination could it be called aristocratic. There was about it a general air of pretentious seediness—dingy curtains and windows more or less grimy in contrast to a new red front: a house to be summed up in the expressive expression "shabby-genteel"—such an abode, in fact, as is usually affected by those who have "seen better days." In answer to the bell, and on inquiring for Mrs. Gray, a swarth domestic vouchsafed the information that she was in, coupled with a side-whisper to Miss Nelly conveying the dire intelligence that she would "catch it."

Mrs. Gray was not yet down, Graham discovered, having been out very late the previous night in search of her child. In answer to an invitation, Graham followed the dusky maid up the innumerable stairs leading to Mrs. Gray's room.

He had ample time to note the common hard furniture, the never-failing neutral-tinted Brussels carpet, and the dim-looking glass, termed by courtesy a mirror, above a mantel decorated with those impossible blue shepherdesses, without which no London lodging-house is complete. Some wax flowers under a glass-case and a few play-bills scattered about completed the adornment of an apartment calculated to engender suicidal feehngs in the refined spectator, Graham had time to take in all this; and at the moment when man's natural impatience began to assert itself, a rustle of drapery was heard, and Mrs. Gray entered.

She was tall and fair, in age apparently not more than five-and-twenty years, with a fine open face, its natural sweetness chastened by the presence of some poignant sorrow. As she saw the child, a bright smile illuminated every feature, and she snatched Miss Nelly to her arms, covering her with kisses; indeed, so absorbed was she in this occupation that she failed to note Graham's presence until Nelly pointed in his direction. Then, and not till then, she looked up to him, her eyes filled with tears. His back being to the light, his features were to be seen but indistinctly.

"I have to thank you deeply," she said, and her voice was very pleasant to the listener. "You will pardon a mother's selfishness. All night—"

Graham, at first half-dazed, like a man in a dream, came quickly forward, and with one bound stood by the speaker's side. He had turned towards the light. She could distinguish every feature now.

"Nelly!"

"Lance!"

For a few moments they stood in a kind of dazed fascination, the eyes of each fell upon each other's face. But gradually the dramatic instinct inherent in woman, and carefully trained in her instance, came to Mrs. Gray's assistance. With a little gesture of scorn, she drew her skirts a little closer round her, and as her coldness increased so did Graham's agitation.

"Well, what have you to say to me?" she asked, with quiet scorn. "Have you any excuse to offer after all these years? What! no words, no apology even, for the woman you have wronged so cruelly?"

"I did not wrong you—not intentionally, at least," said Graham, with an effort. "No, there has been no forgetfulness; my memory is as long as yours. It seems only yesterday that I returned from Paris to find my home empty, and proofs, strong as Holy Writ, of your flight."

"And you believed? You actually believed that I— Shall I condescend to explain to you how I received a letter to say you were lying there at the point of death, and that I, in honour bound, came to you—only to find that a scoundrel had deceived us both."

"But I wrote no letter. I—"

"I know you did not—all too late. I know that I was lured to Paris by a vile schemer who called himself your friend. And when I returned, what did I find? That you had gone, never giving me a chance to clear myself. Deceived once, you must needs fancy deceit everywhere."

"But I was ruined," cried Graham. "That scoundrel Leslie had disposed of every penny of our partnership money. I must have been mad. I followed him, but we never met till last May; out in California that was. He was dying when I found him; and before he died he told me everything. Nelly, I only did what any other man would have done. Put yourself in my place, and say how you would have acted."

"How would I have acted?" came the scornful reply. "I would have trusted a little. Do you think, if they had come to me and shown me those proofs, I would have believed? Never!"

"Helen, listen to me one moment. I mad then, mad with despair and jealousy, or perhaps I might hesitated. Let us forget the past and its trials, and be again as we were before. I was wrong, and bitterly have I atoned for my hasty judgment. I am rich now."

"You are rich! Who cares for your riches?" Helen Graham answered passionately, conscious that his words had moved her deeply. "What is wealth when there is no love, or which has been killed by doubt? There would always be something between us, some intangible—"

"My dear wife, for the sake of the little one." Graham had touched upon a sympathetic chord, and he continued, " It was no mere coincidence which led me to find her last night Nelly, never at any time during the last four miserable years have I forgotten you. By hard work I have found my lost fortune, but I have not found forgetfulness."

He pointed to the wondering child, who stood regarding the speakers with eyes of deep intense astonishment. The tears rose unbidden to the mother's eyes, but she dashed them passionately away.

"Do you think I have never suffered," she cried, "all this time, with a taint upon me, and the hard struggle I have had to live? As you stand there now you doubt my innocence."

"As Heaven is my witness, no!" Graham answered brokenly. "I am no longer blind."

"I thank you for those words, Lance," came the reply with a certain soft cadence. "I know you loved me once."

"And I do now. I have never ceased to love you."

"Do not interrupt me for a moment. For the sake of your kindness to my child I forgive you. Friends we may be, but nothing more. She is your child as well as mine. I cannot hinder you from seeing her, for the law gives you that power, I know."

"The law! " Lance returned bitterly; "things are come to a fine pass when husband and wife, one in God's sight, can calmly discuss the narrow laws of man's making. In this little while the child has twined herself round my heart more than I dare confess. I cannot come to you as a friend, you know I cannot. I will not take the little one away from you, and there is no middle course for me to adopt."

There was another and more painful silence than the last. All the dramatic scorn had melted from the injured wife's heart, and left nothing but a warm womanly feeling behind. Strive as she would, there was something magnetic in Graham's pleading tones, conjuring up a flood of happy memories from the forgotten past. Graham, throwing all pride to the winds and perfect in his self-abasement, spoke at length, speaking with a quiet tender earnestness, infinitely more dangerous than any wild exhortation could be.

"Nelly, I must have the truth," said he; "I am alone in the world, nay more, for I am beginning to realise what I have lost. If you will look me in the face and tell me that all the old love is dead, I will go away and trouble you no more."

"But as a friend, Lance. Surely if I might—"

Graham beckoned the little Nelly to his side and took her on his knee. "Little sweetheart," he asked, "tell me all you told me last night about your wicked runaway father. Who taught you to say 'God bless dear papa and send him home again,' as you said to me last night?"

"Mamma," said Nelly confidentially, "and she says so too." Graham looked up with a smile. There were tears in his wife's eyes beyond the power of control, and a broken smile upon her face. "Let the little one decide," she said.

Lance leant down and kissed his child with quivering lips. Then with one of her imperious gestures, she pointed to her mother and bade him kiss her too. There was a momentary hesitation, a quick movement on either side, and Helen Graham was sobbing unrestrainedly in her husband's arms.

"As if I could have let you go," she said at length. "Oh, I always knew you would find the truth some day, Lance."

"Yes, thank Heaven," he said gravely. "Providence has been very good to us, darling."

He turned to little Nelly. "Do you know who I am?" he asked.

"Oh yes, yes," she cried, clapping her hands gleefully, "You are my own dear runaway papa. Mamma, you mustn't let him run away any more."

"You will find him if he does," said Helen, with a glorious smile. "but I am not afraid."

"SUNNY APRIL" of the poet's fancy had faded into May; and at length had succumbed to the warmth of early summer. Though the season had been a late one, hedges and sloping woodlands glowed with a tender mass of greenery against a snowy background of pear-blossom and pink-flushed apple-bloom. The fortunate "ten thousand," dragged captive behind the gilded chariot of Fashion, turned their faces from the fresh born beauty, now at its best and brightest, to slave and toil, to triumph and be triumphed over; for the first drawing-room was "ancient history," and the lilacs in the Park were fragrant with pink flowers. Town was very full—that is to say, the four odd thousands of suffering, struggling humanity were augmented by the handful of fellow-creatures who aspire to lead the world and make the most of life. The Academy had opened its door for nearly a month, and the dilettante, inspired by the critics, had stamped with the hall-marks of success the masterpieces of Orchardson and Solomon, had dwelt upon the vivid classicality of Alma Tadema, and listened in languid rapture on opera nights to Patti and Marie Roze. Already those who began to feel the heat and clamor of "the sweet shady side of Pall Mall" sighed in secret for the freshness of green fields, and were counting the days which intervened between them, and "royal Ascot."

It is a fine thing, doubtless, to be one of Fortunatus's favorities, to rise upon gilded pinions, and to soar whither one listeth; to be in a position to transport the glorious freshness of the country into the stifled atmosphere of towns. Down the sacred streets, sun-blinds of fancy hues and artistic arrangement repelled the ardent heat, filtered the light through silken draperies of pink and mauve on to pyramids and banks of fragrant flowers, gardenias and orchids, and the deep-blue violets fresh and dewy from the balmy Riviera itself.

A glorious day had been succeeded by a perfect night. Gradually the light deepened till the golden outlines of the mansions in Arlington street gave promise of the coming moon, rising gradually, a glowing saffron crescent, into the blue vault overhead. From every house there seemed to float the sound of revelry; a constant line of carriages filtered down the street; and many outcasts, drifting Heaven alone knows where, caught a passing glimpse of fairyland between the ferns and gleaming statuary, behind doors flung, with mocking hospitality, open.

There was one loiterer there who took slight heed of those things. His shabby raiment might at one time have been well made, but now it was no longer presentable in such an aristocratic quarter; his boots, trodden down at heel, were a scant protection against the heat of the fiery pavement. The face was that of a man who had seen better days, a young face, not more than 30 at the outside, a handsome countenance withal, but saddened by care and thought, and the hard lines of cultivated cynicism, peculiar to the individual who is out of suits with fortune. For a moment he stood idly watching an open door, before which stood a neatly-appointed brougham; and within the brilliantly lighted vestibule, half in shadow and half in the gloom, a tall graceful figure loitered, a haughty-looking woman, with a black lace mantilla twisted round her uplifted head. It was a striking picture— the dainty aristocrat within, the neglected wanderer without; he half shrinking in the shadows, she clear-cut as cameo against the blazing light, a background of flowers and ferns to show off her regal beauty. As she swept down, the steps at length towards the carriage, something bright and shining fell from her throat, and lay gleaming on the marble tiles at her feet. Apparently the loss was unnoticed, for the brougham door was closed behind her before the stranger stepped forward and raised the trinket from its perilous position.

"I think you have dropped this," he said quietly, with a tone and ease of manner in startling contrast to his appearance. "May I be allowed to restore it to you?"

The haughty beauty, disturbed in some pleasant reverie, looked up almost without catching the meaning of the words. She saw nothing more than a humble individual of a class as distinct from her own as the poles are apart, who, perhaps in the hope of a small reward, had hastened to restore the lost property to its rightful owner.

"Oh, thank you," she replied, half turning in his direction, at the same time, taking the brooch, and placing a piece of money in the stranger's hand. "I should have been greatly distressed to have lost this."

"The miniature, must be valuable," returned the stranger, mechanically regarding the coin in his hand. "But you will pardon me in calling attention to another mistake— You have given me a sovereign."

"You scarcely deem it enough," said the girl, with a half-smile, as the strange anomaly of her position flashed across her mind. "If—"

"On the contrary, madam, I am more than rewarded."

"No," as she once more opened the little ivory purse.

Again the palpable absurdity of her situation struck the listener. That she was speaking to a man of education there was no longer reason to doubt. And yet the fact of his accepting the sovereign severely militated against the fact of his being what his language implied.

"You surely are a man of education, are you not?" she asked.

"Really, I can hardly tell you," he answered with some confusion. Then, suddenly pulling himself together, he said: "But I am presuming. It is so long since a lady spoke to me, that for a moment I have forgotten that I am what I am."

He had lost himself for a moment, thinking himself back in the world again, till his eyes fell upon the silver harness glittering in the moonlight, and the marble statuary gleaming in the vestibule behind. But the listener drew herself up none the higher, and regarded him with a look of interest in her dark dreamy eyes.

"I do not think so," she said, "and I-I am sorry for you if you need my pity. If I can do anything—"

Some sudden thought seemed to strike her, for she turned half away, as if ashamed of her interest in the stranger, and motioned the servant to close the carriage door behind hor. The loiterer watched the brougham till it mingled with the stream of vehicles, and then, with a sigh, turned away.

"281 Arlington street," he murmured to himself. "I must remember that. And they say there is no such thing as fate! Vere, Vere, if you had only known who the recipient of your charity was."

He laid the glittering coin on his palm, so that the light streamed upon it, and gazed upon the little yellow disc as if it had been some priceless treasure. In his deep abstraction he failed to notice that standing by his side was another wayfarer, regarding the sovereign with hungry eyes.

"Mate," exclaimed the mendicant eagerly, "that was very nigh being mine."

The owner of the coin turned abruptly to the speaker. He beheld a short powerful-looking individual, dressed in rough cloth garments, his closely- cropped bullet-shaped head adorned by a greasy fur cap, shiny from long wear and exposure to all kinds of weather.

"It might have been mine," he continued "only you. were too quick for me. With a sick wife and three children starvin" at home, it's hard."

"Where do you live?" asked the fortunate one abruptly.

"Mitre Court, Marchant street, over Westminster bridge. It's true what I'm telling you. And if you could spare a shillin'—"

The questioner took five shillings from his pocket and laid them on his open palm. As he replied, he eyed his meaner brother in misfortune with a shady glance, in which sternness was not altogether innocent of humour.

"I have seen you before," he observed, "and so, if I am not mistaken, have the police. You can have the five shillings, and welcome, which just leaves me this one sovereign. I am all the more sorry for you becouse I have the honor of residing in that desirable locality myself."

So saying, and dropping the coins one by one into the mendicant's outstretched hand, and altogether ignoring his fervid thanks, John Winchester, to give the wanderer his proper name, walked on, every trace of cynicism passed from his face, leaving it soft and handsome. His head was drawn up proudly, for he was back with the past again, and but for his sorry dress, might have passed for one to the manner born.

Gradually the streets became shabbier and more squalid as he walked along; the fine shops gave place to small retailers' place of business; even the types of humanity began to change. Westminster Bridge with its long lane of lights was passed, till at length the pedestrian turned down one of the dark unwholesome lines leading out of the main road, a street with low evil-looking houses, the inhabitants of which enjoyed a reputation by no means to be envied by those who aspired to be regarded as observers of the law. But adversity, which makes us acquainted with strange bedfellows, had inured the once fastidious Winchester to a company at once contemptible and uncongenial. He pursued his way quietly along till at length he turned into, one of the darkest houses, and walking cautiously up the rickety, uneven stairs, entered a room at the top of the house, a room devoted to both living and sleeping purposes, and illuminated by a solitary, oil-lamp.

Lying on a bed was a man half asleep, who, as Winchester entered, looked round with sleepy eyes; fine gray eyes they might have been, but for their red hue and bloodshot tinge, which spoke only too plainly of a life of laxity and dissipation. In appearance he was little more, than a youth, a handsome youth but for the fretful expression of features and the extreme weakness of the mouth, not wholly disguised by a fair moustache.

"What a time you have been!" he cried petulantly. "I almost go mad lying here contemplating these bare walls and listening to those screaming children. The mystery to me is where they all come from."

Winchester glanced round the empty room, all the more naked and ghastly by reason of certain faint attempts to adorn its native hideousness, and smiled in contemptuous self-pity. The plaster was peeling from the walls, hidden here and there by unframed water-colors, grim in contrast; while in one corner an easel had been set up, on which a half-finished picture had been carelessly thrust. Through the open windows a faint fetid air percolated from the court below in unwholesome currents, ringing with the screams of children, or the sound of muffled curses in a deeper key.

"'Tis sweet to know there is an eye will mark our coming, and grow brighter when we come.' Poverty calls for companionship, my dear Chris. Why not have come out with me and seen the great world enjoying itself? I have been up west doing Peri at the gates of Paradise."

"How can I venture out?" exclaimed the younger man with irritation. "How can a man show himself in such miserable rags as these? It isn't every one who is blessed with your cosmopolitan instincts— But enough of this frivolity. The first great question is, have you had any luck? The second, and of no less importance, how much?"

"In plain English, have I any money? Voilà!"

Winchester drew the precious coin from his pocket and flung it playfully across to his companion. His eyes glittered, his face flushed till it grew almost handsome again then he turned to the speaker with a look nearly approaching gratitude, or as near that emotion as a weak selfish nature can approach. Winchester laughed, not altogether pleasantly, as he noticed Ashton's rapidly-changing expression of feature.

"'Pon my word, Jack, you are a wonderful fellow and what I should do without you I dare not contemplate. Have you found any deserving picture-dealer who had sufficient discrimination to—"

"Picture-dealer!" Winchester echoed scornfully. "Mark you, I have been doing what I never did before—something, I trust, I shall never be called to do again. I told you I had been up west, and so I have, hanging about the great houses in expectation of picking up a stray shilling; I, John Winchester, artist and gentleman. And yet, someway, I don't feel that I have quite forfeited my claim to the title."

"You are a good fellow, Jack, the best friend I ever had," said Chris Ashton after a long eloquent pause. "I should have starved, I should have found a shelter in jail, or a grave in the river long ago, had it not been for you. And if it had not been for me, you would be a useful member of society still. And yet, I do not think I am naturally bad; there must be some taint in my blood, I fancy. What a fool I have been, and how happy I was till I met Wingate."

The melancholy dreariness of retrospection, the contemplation of what might have been dimmed the gray eyes for a moment while Winchester, his thoughts far away, pulled his beard in silent rumination.

"When you left the army three years ago—"

"When I was cashiered three years ago," Ashton corrected. "Don't mince matters."

"Very well. When you were cashiered for conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman, you came to me, and I saved you from serious consequences. You were pretty nearly at the end of your tether then, and Wingate was quite at the end of his; you had spent all your share of your grandfather's money, and your sister had helped you also. When Wingate stole that forged bill of yours, that I had redeemed, from my studio, you thought it was merely to have a hold upon you, in which you are partly mistaken. He kept it because he imagined that, by making a judicious use of the document, your sister might be induced to marry him to shield you."

"At any rate, he profited little by that scheme. There was a time, Jack, when I thought you were in love with Vere."

Winchester bent forward till his face rested on his hands.

"I always was; I suppose I always shall. If it had not been for your grandfather's money— But there is nothing ito be gained by this idle talk. That is the only thing I have to regret in my past, that and my own fruitless idleness. Carelessly enough, I sacrificed all my happiness. Little Vere, poor child! What would she say if I were to remind her of a scertain promise now!"

"Marry you!" Ashton replied with conviction. "Ay, in spite of everything."

"Winchester laughed joylessly, bitterly, as he listened. He, a social outcast, beyond the pale of civilisation almost; she, with beauty and fortune, and if rumor spoke correctly, with the strawberry leaves at her feet, if she only cared to stoop and raise them to her brows. A sweet vision of a fair pleading face, lighted by a pair of dark brown eyes, looking trustingly into his own, rose up with faint comfort out of the dead mist of five years ago.

"Some day I fancy you will come together again, you and she, Jack, when I am no longer a burden to you. If I could, rid, myself of my Frankstein, my old man of the sea, I wouid have one more try. But I cannot my nerve is gone, and I am, after all, a poor, pitiful coward— I must tell you, I must: Wingate has been here again."

There is something very terrible in the spectacle of a strong man crushed by the weight of an overwhelming despair. Winchester crossed over and laid his hand in all kindness on his friend's shoulder, though his face was black and stern. For a moment it seemed that he would give way to the passion burning in every vein, but by a great effort he controlled himself.

"And what is the latest piece of scoundrelism, may I ask?"

Ashton's face was still turned away from the speaker. His reply came painfully, as if the words cost him an effort. "At first I refused, till he held that bill over my head and frightened me. It is bad this time, very bad, for, disguise it how he will, it is nothing but burglary. They want me to help them; they say I can if I will. And if not—"

"Ah, so it has come to that at last. You know something of the plans, of course. Where is the place they propose to honor with a visit?"

Somewhere in the West End—Arlington street, I fancy anyway, it is some great house, the residence of a well-known heiress. Wingate did not say whose, but the number is 280 or 281."

Winchester's face was very grave now, and almost solemn in its intensity. A dim glimmering of the vileness of the plot began to permeate his understanding. That Wingate, the before-mentioned scoundrel, knew well who the heiress was, he saw no reason to doubt.

"Chris," said he, with quiet earnestness, "turn over and look me in the face;" which the unhappy youth did with a strange feeling of coming relief.

"I told you I had been loitering in the streets to-night, and one of the streets I happened to choose was Arlington street— by chance, as some people would say. By the same chance, as I was waiting there, a beautiful girl came down the steps to her brougham, arrayed for some gaiety or another. In so doing she dropped a beautiful ornament and passed into her carriage without noticing her loss. I hastened to restore it to her; my back was to the light, so she could not recognise me. But I did recognise her. She gave me the sovereign lying there, and what was better, she gave the her sweet womanly sympathy. It was not out of any idle curiosity that I made a note of the number of the house. I hope you are listening to me, Chris?"

"Yes, dear old fellow, I am listening."

"It was 281, and she was the heiress Wingate mentioned. You think the coincidence ends here, but not quite. I said that I recognised her; I also said she could not recognise me. Can you guess who it was?'

"Not-not Vere!" Ashton exclaimed brokenly—"my sister?"

"It was Vere, changed, more beautiful, but the same Vere. Now, cannot you see the whole fiendishness of Wingate's plot? Cannot you see that if anything is discovered, he will get off scot-free, when you are implicated? My boy, I am going to play a bold stroke for your freedom. I am going to break the vow I made five years ago, in the hope that good may come o£ it. Treat Wingate for the present as if you are still his tool, and trust me, for beyond the darkness I see light at last."

THERE are some of us born and reared far enough beyond the contaminating influences of evil, who, nevertheless, take so naturally to rascality, that one is prone to ask a question as to whether it is not the outcome of some hereditary taint or mental disease. To this aberrant class, Anthony Wingate, late of Queen's Own Scarlets, naturally belonged.

Commencing a promising career with every advantage conferred by birth, training, and education, to say nothing of the possession of a considerable fortune, he had quickly qualified himself for a prominent position amongst those cavaliers of fortune who hover on the debatable land between acknowledged vice and apparent respectability. In the language of certain contemporaries, he had once been a pigeon before his callow plumage had been stripped, and it became necessary to lay out his dearly-bought experience in the character of a hawk. Five years of army life had sufficed to dissipate a handsome patrimony; five years of racing and gambling, with their concomitant vices, at the end of which he awoke to find himself with an empty purse, and a large and varied assortment of worldly knowledge. Up to this point, he had merely been regarded as a companion to be avoided; as yet, nothing absolutely dishonorable had been laid to his charge, only that common report stated that Anthony Wingate was in difficulties; and unless he and his bosom friend Chris Ashton made a radical change, the Scarlets would speedily have cause to mourn their irreparable defection.

But, unfortunately, neither of them contemplated so desirable a consummation. In every regiment there are always one or two fast young 'subs' with a passion for ecarté and unlimited loo, and who have no objection to paying for that enviable knowledge. For a time this pleasant condition of affairs lasted, till at length the crash came.

One young officer, more astute than the rest, detected the cheats and promptly laid the matter before his brothers-in-arms. There was no very grave scandal, nothing near so bad as Ashton had suggested to Winchester, only that Captains Wingate and Ashton resigned their commissions, and their place knew them no more. There was a whisper of a forged bill, some hint of a prosecution, known only to the astute sub and his elder brother and adviser-in-chief, Lord Bearhaven, and to Vere Dene, Ashton's sister, who is reported to have gone down on her knees to his lordship and implored him to stay the proceedings. How far this was true, and how Vere Dene came to change her name, we shall learn presently, But that there was a forged bill there can be no doubt, for Wingate had stolen it from Winchester's studio while visiting Ashton, after the crash came and, moreover, he was using it now in a manner calculated to impress on Ashton the absolute necessity of becoming the greater scoundrel's tool and accomplice. Since that fatal day when he had flown to careless bohemian Jack Winchester with the story of his shame, and a fervid petition to beg, borrow, or steal the money necessary to redeem the fictitious acceptance bearing Bearhaven's name, he had not seen his sister, though she, would cheerfully have laid down all her fortune to save him. But all the manhood within him was not quite dead, and he shrank, as weak natures will, from a painful interview. Winchester had redeemed the bill, and Wingate had purloined it.

Winchester had been brought up under the same roof as Vere Ashton, by the same prim puritanical relative, who would hold up her hands in horror at his boyish escapades, and predict future evil to arise from the lad's artistic passion. It was the old story of the flint and steel, fire and water; so, chafed at length by Miss Winchester's cold frigidity, he had shaken the dust from his feet, and vowed he would never return until he could bring fame and fortune in his train. There was a tender parting between the future Raphael and his girlish admirer under the shadow of the beeches, a solemn interchange of sentiments, and Jack Winchester started off to conquer the world with a heart as light and unburdened as his pocket.

But man proposes. Vere's mother had been the only daughter of a wealthy virtuoso, who had literally turned his only daughter out of doors when she had dared to consult her own wishes in the choice of a husband and for years, long years after Vere and Chris had lost both parents, he made no sign. Then the world read that Vavasour Dene was dead, and had left the whole of his immense fortune to his grandchildren three-fourths to Vere on condition that she assumed the name of Dene, and the remainder to Chris, because, so the will ran, he was the son of his mother. Presently, Winchester, leading a jolly bohemian existence in Rome, heard the news, and decided, in the cynical fashion of the hour, that Vere would speedily forget him now. And so they drifted gradually apart. Winchester had been thoughtless, careless, and extravagant living from hand to mouth, in affluence one day, in poverty another but he was not without self-respect, and he had never been guilty of a dishonorable action. He hated Wingate with all the rancour a naturally generous nature was capable of feeling, and set his teeth close as he listened.

"Of course it was only a matter of time to come to this," he said. "Well, of all the abandoned scoundrels— And that man once had the audacity to make love to Vere, you say. I wish I had known before."

"That was a long time ago," Ashton replied, "before— before we left the army, when you were in Rome. Remember, Wingate was a very different man, in a very different position then. Do you suppose that he knows whose place it is that he contemplates—?"

"Knows! of course he knows. Now listen to me, Chris, my boy, and answer me truthfully. I believe, yes, I do, that if you had a chance you would end this miserable life. You say you are in Wingate's power. What I want to know is whether he carries that precious paper about with him?"

"Always, always, Jack. With that he can compel me to anything; the only wonder is that I have never forced it from him before now. Still, I do not see what that has to do with the matter."

Winchester smoked in profound silence for a time, ruminating deeply over, a scheme which had commenced to shape itself in his ready brain.

"I don't suppose you do understand," he said dogmatically. "Do you think if I were to see Vere she would acknowledge me, knowing whom I am?"

For answer Ashton laughed almost gaily. "Your modesty is refreshing. Do you think she has forgotten you, and the old days at Rose Bank? Never! There are better men than you; handsomer, cleverer by far; she meets daily good men and true, who would love her for her sweet self alone. She is waiting for you, she will wait for you till the end of time. Whatever her faults may be, Vere does not forget."

A dull red flush mounted to the listener's checks, a passionate warmth flooded his heart almost to overflowing; but even the quick sangumeness of his mercurial disposition could not grasp the roseate vision in its entirety. Its very contemplation was too dangerous for ordinary peace of mind.

"One more thing I wish to know," said he, reverting doggedly to the original topic. "Of course the dainty Wingate does not intend to soil his fingers by such an act as vulgar burglary. Who is the meaner rascal?"

"So far as I can gather, a neighbor of ours, a very superior workman, I am told, who is suffering from an eclipse of fortune at present. The gentleman's name is Chivers— Benjamin CHivers. Is the name familiar?"

"Why, yes," Winchester answered dryly, "which is merely what, for a better word, we must term another coincidence. The fellow has a most respectable wife and three children, who are distinguished from the other waifs in the street by a conspicuous absence of dirt. I thought I recognised the fellow's face."

"Recognised his face? Have you seen him, then?"

Winchester gave a brief outline of his interview with the individual he had chanced to encounter in Arlington street. A little circumstance in which one day he had been instrumental in saving a diminutive Chivers from condign chastisement had recalled the ex-convict's face to his recollection. Perhaps—but the hope was a wild one—a little judicious kindness, and a delicate hint at the late charitable demonstration, might sufficiently soften the thief's heart and cause him to betray Wingate's plans. That they would not be confided entirely to Ashton he was perfectly aware, and that the meaner confederate had been kept, in want of funds by his chief the fact of his begging from a stranger amply testified.

"Which only shows you that truth is stranger than fiction," said he, as he rose to his feet and donned his hat. If I only dared to see her and even then she might— but I am dreaming. However, we will make a bold bid for freedom. And now you can amuse yourself by setting out the Queen Anne silver and the priceless Dresden for supper;" saying which, he felt his way down the creaky stairs into the street below.

The 10 days succeeding the night upon which this important conversation was held were so hot that even Ashton, much as he shrank from showing himself out of doors in the daytime, could bear the oppressive warmth no longer, and had rambled away through Kennington Park Road, even as far as Clapham Common, in his desire to breathe a little clear fresh air. Winchester, tied to his easel by a commission which, if not much, meant at least board and lodging, looked at the blazing sky ahd shook his head longingly. Despite the oppressive, overpowering heat, the artist worked steadily on for the next three hours. There was less noise than usual in the street below, a temporary quiet in which Winchester inwardly, rejoiced. At the end of this time he rose and stretched himself, with the comfortable feeling of a man who has earned a temporary rest. In the easy abandon of shirt sleeves he leant out of the window, contemplating the limited horizon of life presented to his view. There were the usual complement of children indulging in some juvenile amusement, in which some broken pieces of oyster-shells formed an important item, and in this recreation Winchester, who had, like most warm-hearted men, a tender feeling towards children, became deeply engrossed. One or two street hawkers passed on, crying their wares, and presently round the corner there came the unmistakable figure of a lady, followed by a servant in undress livery, bearing a hamper in his arms, a burden which, from the expression of his face, he by no means cared for or enjoyed.

"Some fashionable doing the Lady Bountiful," Winchester murmured. "Anyway, she has plenty of pluck to venture here. If she was a relation of mine—"

He stopped abruptly and stared in blank amazement, for there was no mistaking the tall figure and graceful carriage of Vere Dene. She passed directly under him, and entered a house a little lower down the street with the air of one who was no stranger to the locality. In passing the group of children, she paused for a moment, and selecting one or two of the cleanest, divided between them the contents of a paper parcel she carried. Directly she had disappeared, a free fight for the spoils ensued. The interested spectator waited a moment to see which way the battle was going, and then hurried down the stairs and out into the street towards the combatants. The presence of the new ally was sorely needed. The three representatives of the house of Chivers were faring sorely in the hands of the common foe. In that commonwealth all signs of favor were sternly discountenanced.

"What do you mean by that?" Winchester demanded, just in time to save the whole of the precious sweetmeats. "Don't you know it is stealing, you great girls, to rob those poor little children?"

"They don't mean it, bless you." said a voice at the mediator's elbow, "and they don't know any better. It's part of their nature, that's wot it is."

Winchester turned round, and encountered the thickset form and sullen features of his Arlington street acquaintance. As their eyes met, those of Chivers fell, and he muttered some incoherent form of thanks and acknowledgment for the past service. Presently he went on to explain.

"You see, my wife is better brought up than most of them about here, and she do try to keep the childer neat and tidy; and that makes the others jealous. They ain't been so smart lately," he continued, with a glance half kindly, half shameful, at his now smiling offspring, "'cause mother has been poorly lately, and I've been out o' luck too."

In spite of his shamefaced manner and the furtive look common to every criminal, there was something in the man's blunt candour that appealed to Winchester's better feelings. Besides, knowing something of the ex-convict and his doubtful connection with Wingate, it was to his interest to conciliate his companion with a view to possible future advantage.

"It must be a miserable life, yours," he said not unkindly. "Better, far better, try something honest. You will not regret it by-and-bye."

"Honest, sir Would to heaven I could get the chance! You are a gentleman, I can see that, though you do live here, and know what misfortune is. If I could only speak with you and get your advice. You have been kind to me, and good to my poor little ones, and I'm-I'm not ungrateful. If I could help you—"

Winchester laid his hand upon his companion's shoulder with his most winning manner. He began to feel hopeful. "You can help me a great deal," said he; "come up to my room and talk the matter over."

It was a very ordinary tale to which he had to listen.

"I was a carpenter and joiner, with a fair knowledge of locksmith's work, before I came to London. I was married just before then, and came up here thinking to better myself. It wasn't long before I wished myself back at home. I did get some work at last, such as it was, a day here and a day there till I became sick and tired of it, and ready for anything almost. I needn't tell you how I got with a set of loose companions, and how I was persuaded to join them... I got 12 months, and only came out 10 weeks ago. I have tried to be honest. But it's no use, what with one temptation and another."

"And so you have determined to try your hand again. You run all the risk, and your gentlemanly friend gets all the plunder."

It was a bold stroke on Winchester's part; but the success was never for a moment in doubt. Chivers' coarse features relaxed into a perfect apathy of terror. He looked at the speaker in speechless terror and emotion.

"We will waive that for the present," Winchester continued. "What I wish to know is how you have contrived to live for the past 10 weeks?"

"I was coming to that, sir, when you stopped me. You see, when the trouble came, my poor wife didn't care to let her friends know of the disgrace, and tried hard to keep herself for a time. But illness came too, and she and the little ones were well-nigh starving. Mary, my wife, sir, remembered once that she was in service with an old lady, whose niece came into a large fortune. Well, she just wrote to her and told her everything. And what do you think that blessed young creature does? Why, comes straight down here into this den, of a place and brings a whole lot of dainty things along. And that's the very lady as is up in my bit of a room at this very minute."

"I am quite aware of that," said Winchester quietly. "Miss Dene, as she is called now, and myself are old friends. I remember everything now. Your wife was once a housemaid at Rose Bank; and you are the son of old David Chivers, who kept the blacksmith's, shop at Weston village. —Ben, do you ever remember being caught birdnesting in Squire Lechmere's preserves with a ne'er-do-well fellow called Jack Winchester?"

For answer, Chivers burst into tears. Presently, after wiping his eyes with the tattered fur cap, he ventured to raise his eyes to his host.

"You don't mean to say it's Mr Winchester?" he asked brokenly.

"Indeed, I am ashamed to say it is. This world of ours is a very small place, Ben, and this is a very strange situation for you and me to meet. But before we begin to say anything touching old times, there is something serious to be discussed between us. Remember, you are altogether in my hands. I might have waited my opportunity and caught you red-handed. Don't ask me for a moment what is my authority, but tell me"—and here the speaker bent forward, dropping his voice to an impressive whisper—"everything about the Arlington street robbery you have planned with that scoundrel Wingate."

Once more, the old look of frightened terror passed like a spasm across the convict's heavy features. But taking heart of grace from Winchester's benign expression, he, after a long pause, proceeded.

"I don't know how he found me out, or why he came to tempt me—not that I required much of that either. It seemed all simple enough, and I was very short of money just then, and desperate-like, though I won't make any excuse. I don't know all the plans—I don't know yet whose house—"

"Whose house you are going to rob," Winchester interrupted with a thrill of exultation at his heart. Then I will tell you as an additional reason why you should make a clean breast of it. Perhaps you may not know that Miss Dene lives in Arlington street and that Miss Dene, whose name, I see, puzzles you, is Miss Ashton, once of Rose Bank?"

"I didn't know," Chivers exclaimed with sudden interest. "If it is the same—"

"It is the same. She changed her name when she inherited her grandfather's fortune. Come, you know enough of Wingate's plans to be able to tell me if No. 281, Arlington street, is the house?"

"As sure as I am a living man, it is," said Chivers solemnly. Mr Winchester, I have been bad; I was on the road to be worse; but if I did this, I should be the most miserable scoundrel alive. If you want to know everything, if you want me to give it up this minute—"

"I want to know everything, and I certainly do not want you to give it up this minute. You must continue with Wingate as if you are still his confederate. And of this interview not a word. I think, I really think, that this will prove to be the best day's work you have ever done."

Chivers answered nothing, but drew from a pocket a greasy scrap of paper cut from a cheap society paper, and placed it in Winchester's hand. As far as he could discern, the paragraph ran as follows

"The delicate and refined fancy of a 'jewel ball,' designed by the Marchioness of Hurlingham, will be the means of displaying to an admiring world the finest gems of which our aristocracy can boast. Starr and Fortiter, et hoc genus omne, are busy setting and polishing for the important event, not the least valuable parure of brilliants in their hands being those of Miss Dene, the lovely Arlington street heiress, who, rumor says, intends to personify diamonds. Half a century ago the Vere diamonds had become quite a household word. Certainly they never had a more lovely mistress to display their matchless beauty."

"That," explained the penitent criminal in a hoarse whisper, is about all I know at present. But if I made a guess, I should say it would be the night after the ball."

IN POINT of artistic beauty and delicacy of floral arrangement throughout Arlington street, No. 281 certainly bore away the palm; for Miss Dene, like most country girls, had a positive passion for flowers—a graceful fancy she was fortunately in a position to gratify. Many an envious eye fell upon that cool facade with its wealth of glorious bloom; many a darling of fashion paused as he passed on his listless way, and forgot his betting-book and other mundane speculations to wonder lazily who might some day be the fortunate man to call that perfectly-appointed mansion and its beautiful mistress his own. For Vere Dene could have picked and chosen from the best of them, and graced their ancestrai homes; but now she was five-and-twenty; so they came at last to think it was hopeless, and that a heart of marble pulsed languidly in that beautiful bosom.

The hall-door stood invitingly open—more, perhaps, in reality to catch the. faint summer breeze, for the afternoon was hot, and inside, the place looked cool, dim, and deliciously inviting. On a table there lay a pair of long slim gauntlets, thrown carelessly upon a gold-mounted riding-whip, and coming down the shallow stairs, against a background of feathery fern and pale gleaming statuary, was Miss Dene herself. A stray gleam of sunshine, streaming through a painted window, lighted up her face and dusky hair—a beautiful face, with creamy pallor, overlaid by a roseate flush of health. The dark-brown eyes were somewhat large— a trifle hard, too, a stern critic of beauty might have been justified in saying; the tall graceful figure drawn up perhaps too proudly.

Vere Dene was, however, no blushing debutante, but a woman who knew her alphabet of life from alpha to omega who was fully conscious of her power, and the value of her position well enough to discern between honest admiration and studied flattery, and to gather up the scanty grains of truth without mistaking chaff for golden corn. There was no reflection of wistful memory on the heiress's face as she rode slowly down the street some time later, the cynosure of admiring eyes. There was a rush and glitter of carriages hurrying parkwards, as she rode on her way alone, bowing to one acquaintance or another, and dividing her favors impartially.

"A beautiful face," murmured a bronzed soldierly-looking man to his companion as they lounged listlessly against the rails of the Row, watching the light tide of fashion sweeping by.

"A perfect face, wanting only soul to make it peerless. Who is she, Leslie?"

"Who is she?" laughed the other. "Is it possible you do not know Miss Dene?— But I forgot you had been so long in India. You remember old Vavasour Dene, of course, and his son, the poetical genius, who married some demure little country maiden, unknown to Debrett or Burke, and who was cut off with the traditional shilling accordingly. You can imagine the rest of the story a life-long fend between father and son, ending, as it usually does, in the parent's dying and cheating condemnation by an act of tardy justice. That handsome girl is old Dene's heiress, a woman with all London at her feet, a quarter of a million in her own right, and never a heart in the whole of her perfect anatomy."

Wholly unconscious of this storiette, and apparently of the admiration she naturally excited, Miss Dene rode, on down the Mile, with many a shake of her shapely head as one gloved hand after another beckoned her to range alongside barouche or mail-phaeton till at length a slight crush brought her to a standstill. Almost in front of her was an open stanhope, wherein was seated a delicate fragile-looking lady, exquisitely dressed, and apparently serenely indifferent to the glances and smiles in her direction. By her side sat a child of six or seven, a diminutive counterpart of herself, to her fair golden hair and melting pansy-blue eyes. Vere would fain have pushed her way through the crowd and passed on but the child had seen her, and uttered her name with a cry of innocent delight and Vere, like many another who is credited with want of heart, had a tender love for children.

"Really, I owe Violet my grateful thanks," murmured the owner of the stanhope as Vere ranged alongside. "Positively, I began to fear that you meant to cut me. I should never have forgiven my brother, if you had. My dear child, I warned him that it was useless; I did indeed. And now he says that his heart is broken, and that he shall never believe a woman any more."

Vere looked down into the Marchioness of Hurlingham's fair demure face with a little smile.

"So Lord Bearhaven has been abusing me?" she said. "I am disappointed. I did not think he would have carried his woes into the boudoir."

"My dear Diana, he has done nothing of the kind. Surely a man might be allowed to bewail his hard lot with his only sister. —Violet, my darling child, do be careful how you cross the road."

"This warning, addressed to the diminutive little lady, who had succeeded unseen, in opening the carriage door came too late; for by this time the volatile child had recognised some beloved acquaintance over the way, and indeed was already beyond the reach of warning. Vere watched the somewhat hazardous passage breathlessly, then, satisfied that her small favorite had made the dangerous journey in safety, turned to her companion again.

"I have a genuine regard for Lord Bearhaven," said she, speaking with an effort, "too great a regard to take advantage of his friendship under false pretences. I shall never forget the kindness he once did me in the hour of my great trouble Will you tell him so, please? and say that perhaps for the present it will be well for us not to meet."

"Now, that is so like both of you," Lady Hurlingham cried, fanning herself in some little heat. "Why will you both persist in making so serious a business. of life? At anyrate, you might have some consideration for us more frivolous-minded mortals. Vere, if you do not come to my Jewel Ball on Thursday, I—I— well, I will never speak to you again."

"So, I am to be coerced, then. I am morally bound to be present, since the Society papers have promised the world a sight of the Vere diamonds; besides which, I simply dare not incur your ladyship's displeasure!"

"I wonder if you have a heart at all," said the other musingly. "Sometimes I almost doubt it; and the times I generally doubt it most are immediately after those moments when I have flattered myself that I really have begun to detect symptoms of that organ. The romantic ones have been libelling again. Would you like to hear the latest story?"

"You stopped me for this, I presume. Positively, you will not know a moment's peace till you have told me. I am all attention."

"They are saying you have no heart, because it was given away long ago; they say there is a rustic lover somewhere in hobnails and gaiters who won your affections, and is afraid to speak since you became a great lady."

Vere did not reply or glance for a moment into her friend's sparkling mischievous face. A deeper tinge of colour flushed the creamy whiteness of neck and brow, like the pink hue upon a snowy rose.

"They do me too much honor." she replied. "Such a model of constancy in this world of ours would indeed be a peril amongst women. Pray, do they give a name to this bashful Corydon of mine?"

"Naturally, nothing but the traditional second cousin, ma chère. Really, it is quite a pretty romance the struggling, artistic genius who is too proud to, speak, now you are in another sphere. Surely you are not offended?"

In spite of her babyish affectations and infantine innocence, mere mannerisms overlaying a tender kindly heart, Helena, Marchioness of Hurlingham, was not entirely without an underlying vein of natural shrewdness. She was clever enough to see now that the innocently-directed shaft of a bow drawn at a venture had penetrated between the joints of Vere's armour, in spite of her reputation for being perhaps the most invulnerable woman in London.

"I am not offended," Vere answered, recovering from her chill composure at length; "only such frivolity annoys one at times. What a lot of idle scandal poor womankind has to endure—What is that?"

Gradually above the roll of carriages, the clatter of hoofs, the subdued murmur of voices, and light laughter, a louder, sterner hum arose. Borne down on the breeze came distant sounds of strife, and now and then a shriek in a woman's shrill notes; it seemed to swell as if some panic had stricken the heedless crowd further down the drive. Every face, restless and uneasy with the sudden consciousness of some coming danger, was turned in the direction whence the evidence of trouble arose, as a carriage and pair of horses, coming along at lightning speed, scattered pedestrians and riders right and left, like a flock of helpless sheep, in a wild medley of confusion.

As if by magic, a lane seemed to have opened, and coming along the open space tore a pair of fiery chestnuts, drawing after them in their fear and fright a mail phaeton as if it had been matchwood. With a feeling of relief, the helpless spectators noticed that the vehicle was empty, save for its driver, who, with bare head and face white as death, essayed manfully to steer the maddened animals straight down the roadway, a task rendered doubly dangerous and difficult from the crowded state of the Row, and the inability of certain tyros to keep the path sufficiently clear.

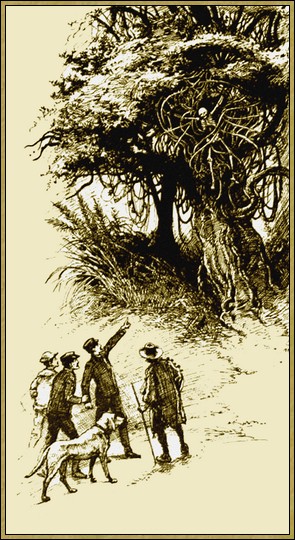

In the midst of the turmoil and confusion there arose another cry, a shout of fear and unheeded expostulation, for, crossing the roadway smilingly, without the semblance of a fear, came a little child, bearing in her hand a bunch of roses; a little girl with sunny golden curls and laughing blue eyes, standing like a butterfly before a sweeping avalanche. There was another shout, and again the tiny passenger failed to note her danger as nearer and nearer came the horses, till through the now paralysed, helpless crowd burst the figure of a man who without a moment's hesitation sprang forward and caught the child just as the pole of the carriage threatened to strike her to the ground. There was no longer time for an escape, a fact of which the heroic stranger was perfectly aware and grasping the laughing maiden with one powerful arm, with the other he made a grab for the off-horse's head, and clung to the bridle with the bulldog tenacity of despair. For a moment the animals, checked in their headlong career, swerved to the right; there was a crashing sound of broken panels, and a moment later child, rescuer, horses, and driver lay in an inextricable struggling confusion. For a second or two there followed a dread intense silence, as each butterfly of fashion contemplated in fascinated horror the struggling mass; then, before the nearest could interfere, it was seen that the stranger had risen to his feet, his garment soiled and stained, and a stream of ruddy crimson slowly trickling down his face. Just for a brief instant he reeled from very faintness, till, dashing the blinding blood from his eyes, he stooped swiftly, and at the imminent risk of his brains drew the now thoroughly frightened child right from those terrible hoofs, and taking her in his arms, staggered rather than walked to a seat.

Meanwhile, Lady Hurlingham, beside herself with grief, and terror, the lady of fashion merged for the moment into the mother, had descended from her carriage, her face pale and haggard, and hurried with Vere to the seat where the stranger reclined. It was no time for ceremony or class distinction. With a gesture motherly and natural, as if she had been moulded of meaner clay, she snatched little Violet from the arms still mechanically holding her, with a great gush of thankfulness to find that, with the exception of the fright, not one single hair of that golden head had been injured.

By this time the crowd had sufficiently recovered from the threatened realisation of sudden death, and, with regained wit, sufficient society veneer to murmur the usual polite condolences and congratulations to the now elated mother. Still the rescuer sat, his face buried in his hands, a whirling, maddening pain in his head, and a mist before his eyes as if the world had suddenly lost its sunshine. Vere, with tears in her eyes and a tremble in her voice, pushed her way through the too sympathetic crush and laid her hand gently oh the sufferer's arm.

"I am afraid you are hurt," she said. "Can I do anything for you?"

Winchester, for he it was, looked up vaguely, the words coming to his ears like the roar of the sea singing in a dream, a dream which was not all from the land of visions. He wondered dreamily where he had heard that voice before. With an effort, he looked up again. For the first time in five years their eyes met in the full light of day. She knew him now, recognised him in a moment. But it was scarcely the same Winchester who had restored her lost ornament a fortnight ago. The old shabby raiment had disappeared, giving place to a neat suit, such as no gentleman had been ashamed to wear. Fourteen days' steady work, inspired by a worthy object, had met an equal reward. It was no longer Winchester the outcast that Vere was addressing, but Winchester the gentleman, and in his heart he rejoiced that it was so. For a moment they were no longer the centre of a glittering host of fashion; their thoughts together had gone back to the vanished past, as they looked into each other's eyes, neither daring to trust to words.

"Jack," said Vere at length, "Jack, is it really you?"

"Yes, dear, it is I," Winchester responded faintly. "You did not expect to meet me like this—if you ever expected to meet me at all."

"Do you think I forget—as some people do? You did not always judge me so harshly. How could we meet better; how could I feel more proud of you than I do at this moment?"