THERE was nothing of the traditional explorer about Jim Craddock. He was not a strong, silent man with a stern brown face and marked absence of flesh, but he was a first "chop" hand at the game, all the same. Moreover, he wrote no books, he contemplated nothing in the way of geographical discovery to London societies, but his knowledge of Central Africa was extensive and peculiar, and if there was a remote corner of the Dark Continent where threepence was to be made, then assuredly Craddock was the man to find it. For the most part he was a freelance, though when times were bad he was not averse to enlisting under the banner of some trading company or as a guide to the sporting "blood" in search of big game. Usually, however, he preferred to work on his own, because this course allowed him to travel about just as he pleased, generally in the company of the humorist who carefully camouflaged himself under the name of Jan Stewer—a sort of left-handed compliment to the county that had given him birth. But, as to the rest, Stewer said nothing, except occasionally to hint that, like the Van Diemen's Land convicts in the old days, he had left his country for his country's good. It was only occasionally and in boastful moments that Stewer ever alluded to the fact, and then only in the presence of Craddock. He was a big strong bull of a man, with a marvellously cool nerve and a certain whimsical humour in time of danger that rendered him invaluable.

Craddock himself was small and lean and brown, with a merry eye and a fearsome taste for music which would have driven anybody but Stewer wild. He travelled the world with a sort of accordion arrangement of his own invention, and it was his proud boast that this weird instrument had had a more soothing effect on the gentle native than anything in the way of melody that had ever been heard on the Dark Continent. And now he was up amongst the Moghis, with an entirely fresh arrangement for capturing the senses of that somewhat turbulent people. It took the form of a gramophone with some exceedingly fine records, mostly of operatic stars.

Craddock and his friend were in that part of the world more or less by accident. They had been having an exceedingly bad time lately, and it had become necessary to seek fresh woods and pastures new, and, moreover, reports had reached Craddock to the effect that there was much ivory in that remote spot. This rumour, however, proved to be false, and, beyond a certain amount of exceedingly inferior rubber, there seemed to be little or nothing to recompense the friends for the risks that they were undoubtedly running. But this fact troubled Craddock not at all, and they wre not having a bad time. There was a prospect of more rubber in the spring, and, moreover, Bomba, the chief of the Moghis, was as friendly as they had any right to expect. They had no camp followers and very little in the way of ammunition, but they managed to make themselves understood, and from the very first the gramophone was the pronounced success that Craddock had confidently prophesied.

Nothing of this kind had ever appeared in those remote wilds before, and the dusky Bomba was amazingly impressed. After the first feeling of terror had worn off, and the tribe had come back timidly to the outside of Craddock's hut, there was a constant clamour for the devil voices. Certainly the great Caruso never had a more flattering or attentive audience.

"It's a real good egg, old man," Craddock told his friend. "I told you it would be, if we could only get the beggars to listen."

They were sitting in the moonlight in front of the hut, smoking their pipes after a most successful day, in which the gramophone had been greatly in evidence, and, consequently, Craddock was in the best of spirits. But Stewer appeared to be just a little dubious.

"Yes, it's all right up to now," he murmured; "but it ain't quite so lovely in the garden as you think. You're such a sanguine beggar, Jim. Old Bomba's all right, but I don't like the look of that chap Sambi."

"What's the matter with Sambi?" Craddock asked. "What can he do? He's only a sort of second-in-command, after all."

"Very likely; but he's got a big following here, and if he can down the old man and take his place, he'll do it. He's got quite a lot of the medicine men of the tribe on his side, and if those chaps like to kick up a bobbery, then the old man's number's up for sure."

"But how should this concern us?" Craddock asked.

"I'm just coming to that," Stewer went on. "About that gramophone of yours. Sambi wants it. He'd give his ears for it. He offered me two elephants for the machine yesterday."

"What's that?" Craddock asked. "Two elephants? Where's he going to get 'em from? Why, there isn't an elephant within five hundred miles!"

"I know, and that's just what makes me so uneasy. I ain't afraid of a shindy, as you know, but seeing that we two are alone, and that we've only got a pair of Mauser pistols between us, I'm not asking for any trouble. And, besides, I don't like that chap's eye. A cross-eyed nigger isn't pretty to look at, and Sambi is a rotten specimen of the breed. Last night, after you were asleep, Sambi came into the tent, and I'm sure he'd have walked off with the machine if I hadn't been awake. Directly I challenged him he was off like a hare, and no doubt he thinks I didn't recognise him, for I didn't mention it to him this morning—I thought it would be wiser not to. But he was after the gramophone all right, and he will stop at nothing to get it."

Craddock chuckled over his pipe.

"The beggar's welcome," he said. "But the machine isn't much good without the records and the needles, and I've taken precious good care of those. I'm not quite so careless as you think, Jan. These chaps don't know even that a needle is necessary, and, as to the records, I put 'em in their waterproof case down our well every night. I don't believe it will hurt them to get wet, but never mind about that. If Sambi gets hold of the goods, he won't be able to make the slightest use of them. Don't you get meeting trouble half-way, Jan. Besides, it ain't like you to talk in this way."

Stewer professed himself to be satisfied, but, all the same, he was anything but easy in his mind. For the next day or two he kept a close eye upon the wily and elusive Sambi, and the more he saw of that oblique-eyed individual, the more sure he was that trouble was looming in the distance. There were many mutterings and whisperings in corners between the second-in-command and the picturesque-looking ruffians who represented the medicine men of the tribe. There were occasions, too, in the evenings, when the natives sat in a circle round the Englishmen's hut and listened enraptured to some of the finest voices in the world, and at all of these Sambi was present, with those oblique, greedy eyes of his fixed with an intense longing on the gramophone. And two days later the gramophone was missing from Craddock's hut.

There was an immense outcry, of course, there were weepings and wailings and loud lamentations, such as usually accompanied the death of the chief, and at the same time Sambi was missing. He had gone up country somewhere, so Bomba said, to hold a palaver with a neighbouring tribe which looked like giving trouble. That there was a good deal of truth in this, Craddock knew, because he had heard the matter discussed before, but in the light of what Stewer had told him he could see plainly enough that the wily Sambi was intent upon killing two birds with one stone. He appeared to be greatly concerned at the disappearance of the devil box, but he knew perfectly well that it must come back to him in the course of a day or two.

"Oh, it's quite all right," he told Stewer. "Sambi's got it right enough, and he's taken it up country with him. He'll come back presently with some fairy story about having found the gramophone in the bush, and probably suggest that a few poor wretches should be sacrificed. Now, you see if I ain't a true prophet. Sambi is no fool, and it won't take him long to realise that 'Hamlet' is a poor play with the Dane left out."

It turned out exactly as Craddock had foreseen, for Sambi put in an appearance three days later with an air of vast importance and a little more obliquity of vision than usual, and proceeded to make a pompous declaration. He told the secretly amused Craddock that he had found the gramophone hidden away in a deserted hut far in a back country, and that he had discovered and punished the culprit, As a matter of fact, there were three culprits altogether, and they had all paid the dread penalty, which, as Stewer subsequently remarked, was probably the only true statement in the veracious narrative.

"Very good, very good, Sambi," Craddock said approvingly. "You have done the State some service—I mean, you are a nut in the detective line. I hope you enjoyed the gramophone. It must have cheered you amazingly on your diplomatic errand."

Sambi grinned somewhat uneasily. He was not entirely deficient of a sense of humour, and he seemed to grasp the fact dimly that his leg was being pulled. Then he shook his head mournfully.

"No spirit make it good," he said. "Me turn and turn the brass god at the end of the box, but no voice he come."

"I hope the fool hasn't broken the spring," Craddock said sotto voce, "Oh, that's all right, Sambi. The gods of the white man are a bit shy of a nigger. Perhaps I'll teach you some day. But look here, old son, what about that mission of yours? How are the Wambas coming along?"

Sambi immediately launched into a long explanation. Literally translated, the Wambas were particularly hot stuff, and never quite happy without their annual dust-up with their good neighbours, the Moghis—in fact, this little excursion appeared to take the same place with them as the annual visit to the seaside in more civilised climes. Sambi had apparently crossed the border with a view to settling some outstanding dispute, which apparently he had failed to do. According to his own account, there had been a violent eruption of party feeling, in which the Speaker of the Wamba House of Commons had lost his head in consequence of some personal remark he had made to the Leader of the Opposition, and, indeed, if Sambi was to be believed, he had narrowly escaped with his own life. Beyond a doubt the annual campaign was near at hand.

"I wonder if the beggar was lying?" Craddock remarked to Stewer, when they were alone again. "Oh, I know these people are always having these little differences of opinion, but somehow I have the impression that Sambi is lying. I can't get out of my head that in some way the gramophone is at the bottom of it, I can't see how, but that's my idea."

But apparently Sambi was telling the truth, for there were a great many signs during the next few days that a crisis was at hand. Bomba called his braves together round the council fire, and for many hours the air was rendered hideous with the din of conflicting opinions. An almost unholy calm fell on the protagonists, after which Bomba made his braves an impassioned speech. He stood there, a fine figure of a man in all his war-paint, with the scarlet cummerbund about his ample waist supporting a veritable battery of obsolete weapons. The women and children were sent to the interior, provisions were collected, and at dawn the following morning the hideous din of tom-toms proclaimed the fact that the motley army was setting forth with a view to putting a proper respect into the thick heads of the Wambas.

"Looks like a Wild West circus," Stewer laughed. "Upon my word, I've half a mind to take a hand at the game myself. Anything's better than loafing around here like this. Don't you think it would be just as well if we made tracks before they get back? It might save a painful parting, and we're not making our salt here."

"Oh, let's see it through," Craddock suggested. "But as to going along, that's quite another story. At any rate, we shall have the village to ourselves for the next week or so, and we shall be able to do as we like. Our friend Sambi is safe for the present, at any rate."

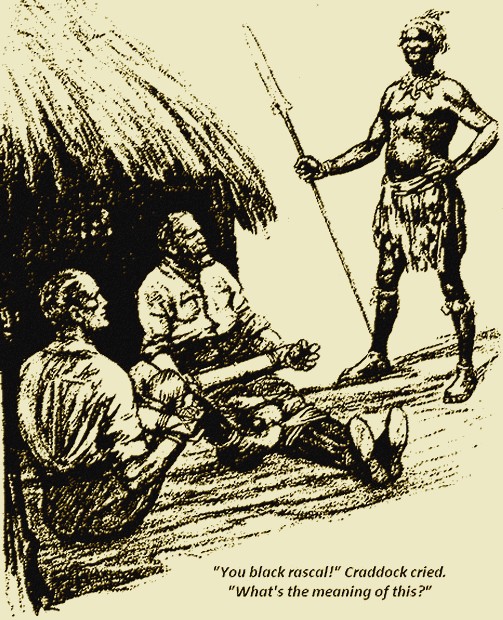

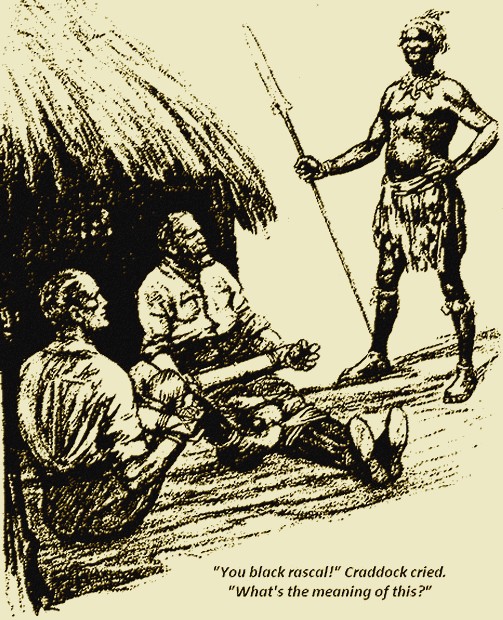

With that, Craddock knocked out his pipe and strolled into the hut for the usual siesta. He was followed a moment or two later by Stewer, and there they lay on their grass beds till late in the afternoon. It was an exceedingly hot day, and they were grateful for the peace and quietness after the constant din that kept the village in a state of turmoil throughout the day. And as Craddock lay there asleep, he began to dream strange things. He dreamt that he was being tortured, that his ankles and knees and wrists were bound with green hide thongs which seemed to be cutting into his very bones. The pain became so great at last that he woke to a dim realisation of the fact that this thing was true. He was lying on the flat of his back, bound exactly in the way he had seen in his uneasy slumbers. A thin rope of green hide was about his feet and ingeniously carried to his hands, which were kept some two feet apart by a piece of tough split bamboo, through which the thong was threaded so that it was impossible for him to get his hands together and work with his fingers on the green hide. It was as if a splint had been placed there, and even Craddock was bound to admire the exceedingly neat piece of work. He was forced to recognise the fact that he was absolutely helpless, and, in addition to this, he was drowsy and heavy, with a racking pain in his head and a bead of moisture on his forehead. He was so overcome that it was some little time before he realised that he was suffering from the effect of a powerful drug. He managed to drag himself to a sitting position presently, and looked somewhat drearily around him.

Presently he caught the eye of his companion, who was in precisely similar case. Then Stewer assumed a sitting position with some considerable difficulty, and the two regarded one another with blank faces.

"Well, we're up against it now all right," the Devonian said. "Great James, what a head I've got on me!"

"Well, we're companions in misfortune there," Craddock grinned. "Say, sonny, what do you make of it?"

"Oh, I don't know," Stewer said. "Looks to me as if we had got an enemy somewhere."

Craddock laughed cheerfully. This was the sort of situation in which he came out at his best.

"Now, that's very bright of you," he said. "But where's the nigger in the fence? There's not a man within miles of the village, and I don't suppose for a moment that the women are responsible for this little jest."

"Then whom do you suspect?" Stewer asked.

"Oh, that's an easy one," Craddock replied. "We've got to thank our ingenious friend Sambi for this. Yes, that's right. Sambi for a million. The more I think of it, the more plain it becomes. He walked off with the gramophone under pretence that he was off on some political mission. If he had understood the thing, he would never have come back; but because he had no records and no needles, he was done, and that's why he came back with that interesting little story about finding the thing in the woods and laying out the chaps that pinched it. The chap's mad to get hold of the machine, and this is how he means to do it. Everybody is away, and his little game is to torture us ingeniously until we are compelled to show him how it will work. Then he'll slope off with the whole apparatus, and probably plant himself down upon some simple unsophisticated tribe, and—well, it's pretty plain, old bird, isn't it?"

Stewer nodded emphatically. He was of entirely the same opinion as his friend, and therefore was fully alive to the gravity of the situation. These were a fairly gentle people they were amongst, but, after all, they were primitives, and both the captives knew only too well what was likely to happen now that Sambi's cupidity was fairly roused. Beyond doubt he had deserted his companions in the field, and had come back to the village with one great object smouldering in the back of his mind. It was just possible, as Craddock explained to Stewer, that there was no trouble with the Wamba tribe at all, but that Sambi had invented the whole thing with a view to getting rid of Bomba and all the rest of the crew whilst he put his plan of campaign into execution.

Meanwhile tney sat there stewing and sweating in the heat of the still afternoon, tugging in vain at their bonds and struggling for freedom. But though it was possible to crawl across the floor until they came in personal contact with one another, the devilish contrivance of those bamboo splints rendered every effort futile. And, to add to their futile fury, they could see on the shelf under the eaves of their hut their two revolvers and case of spare ammunition; but in their present helpless condition the weapons might have been a thousand miles away.

"It's no use," Craddock gasped presently. "We shall have to wait. Sambi is bound to come along presently, and we might be able to compromise with him."

Stewer grunted as he thought reluctantly of the useless pipe and tobacco in his pocket, whilst Craddock dragged himself to the door of the hut and stood blinking up at the sunshine. There was not a soul to be seen and not a sound to be heard, for the women and children had been removed in case of trouble on the frontier, and even the dogs had followed them. In a curious, detached sort of way Craddock stood there watching a colony of great white ants working about the base of a hill of dead vegetable refuse which they had thrown up just outside the hut. It was not a pleasant sight, because it recalled memories of old stories which he had heard in his wanderings. He knew, for instance, that one of the persuasive methods of the natives was to tie up a prisoner to a stake driven in the centre of an ant hill and leave him there to his reflections. If he remained long enough, he would be eaten bit by bit by those ferocious white ants, or driven mad by the torture of them. It was a thought that turned Craddock cold. He could see himself standing there, with those diabolical little brutes crawling all over him and gradually eating into his very vitals. For there were hundreds of thousands of them in one of those big heaps, to say nothing of the fact that they were the best part of an inch long.

And yet, even as Craddock lingered there, contemplating this dread tragedy, something of a plan was forming in his mind. It was when danger stared him in the face that he was at his best and brightest. He just turned to say something of this to Stewer, when the grinning Sambi hove in sight. He appeared to be on the best of terms with himself, for a vast smile seemed to split his face in twain and displayed a set of teeth that a mastiff might have envied.

"Well, you black rascal," Craddock cried, "what's the meaning of this? You cut these cords!"

Sambi grinned pleasantly and shook his head.

"No cut," he said. "We sit down and palaver."

With a murderous feeling in his heart, Craddock complied. There was nothing to gain by a display of passion, and it was just possible that by diplomacy he would be able to achieve his ends.

"Oh, all right," he said. "Now, then. I know pretty well what you want, you rascal, but you can't make us give you the best part of the devil box. Still, I'm ready to make a bargain with you."

"That is all good," Sambi grinned. "You give me the voice of the moon children, and the little god that rubs him on the chest and makes him talk, and presently I send one of the women to free you. You give me those, and the round black things that shine in the sun, and we are friends."

"Yes, and what then?" Craddock asked.

"Why, then I travel to the country beyond the rains with the devil box—to a far country where they make me king and there is much million ivories. You say 'Yes,' and it's done."

Craddock replied vigorously enough, in a sort of vernacular, to the effect that he was not taking any. He half expected some passionate outburst on Sambi's part, but it did not come. The wily nigger merely grinned and pointed significantly to the ant heap outside the hut. It was clear enough to Craddock now that Sambi had lured the tribe off on a wild-goose chase, so that he could work out the plot at his leisure.

"All good," Sambi said. "I give you food, but not the pipe, and in the morning you will think better of it."

He did not express himself quite so clearly, but that was the meaning. He lingered long enough to assure himself that the bonds of his prisoners were sound, after which he lounged out of the hut, to return a little later with food, which he placed on the floor for his captives to assimilate as best they might.

"What was the brute driving at?" Stewer asked. "I can't follow the lingo as well as you do. I know he was trying to drive a bargain with you over the gramophone, and I could see you weren't taking any. If you don't, what's going to be the upshot of the business?"

"Nothing very pleasant," Craddock grinned. "That black scamp's worked the whole thing out in his mind, and very cleverly he has done it. But he's a long way from getting the gramophone yet."

"And if he doesn't?" Stewer queried.

Craddock indicated the ant heap and elaborated the stories he had heard in connection with it.

"Ugh!" Stewer shuddered. "Sounds worse than the torture in the 'Mikado.' But you're not going to let it go as far as that, I suppose?"

"Not quite," Craddock said between his teeth, "but very nearly. I never was beaten by a nigger yet, and I'll be hanged if I'm going to start now. If only one of us could get rid of the hide through this splint, by wearing it away or cutting it, we should be free in five minutes. Once that happened, we should have our revolvers again, and Sambi's path of glory would end in something abrupt in the way of a grave. See my meaning?"

"Oh, I see your meaning plainly enough," Stewer grunted, "but how's it going to be done?"

"But it ain't impossible," Craddock said. "Only the remedy is a desperate one, and I suppose you have heard of the expedient called taking a hair from the dog that bit you? Now, that's exactly what I'm going to do. I am going to suffer a little to save us from suffering a lot, if you understand what I mean. And when the moon goes down this evening, I'll show you. I'm going to teach that confounded nigger a lesson."

With that, Craddock shut his teeth grimly and refused to say any more. But presently, as the night began to wear thin, and the moon slid behind the dense foliage at the back of the village, he crept out into the open and for a moment contemplated the conical mass of rubbish of which the ants' nest was composed. Then quite deliberately he lay down on his stomach and buried his two arms, with the long splint between them, in the crown of the nest. With sudden enlightenment Stewer watched him. He knew that Craddock, with his indomitable pluck and cheery courage, meant to keep his arms buried there until the little white devils in the nest had eaten their way through the thong that had been woven between the two holes at the end of the bamboo cane, and, stolid as he was, Stewer gasped with admiration at Craddock's amazing fortitude.

"Here, come out of it!" he cried. "It isn't worth while. Better let Sambi have the gramophone a thousand times over."

"I never was beaten by a nigger yet..." Craddock began, and then his voice trailed off into a whisper. Already the little white insects, raging furiously at this assault upon their citadel, were swarming all over his arms, until the blood began to stream from a hundred tiny punctures. And still he held on, suffering untold agonies, knowing full well that, if he could only hold up for a little longer, the white foe would cease to rage, and turn its attention to the succulent green hide with which he was bound. It was half an hour or more before Craddock, straining at his bonds, felt them relax like a piece of elastic. Then, with a fine effort, he snapped the last threads of green hide and rose to his feet with a pair of forearms dripping red.

"There!" he said, as he staggered giddily towards the hut. "Didn't I tell you it would be all right? But, my aunt, I wouldn't go through that again for all the gold in Africa! But no nigger—"

With that he fainted, and it was some moments before he came to himself again. He stripped himself to the buff, and, after carefully removing every ant from his clothing, proceeded to cut Stewer's bonds. This being done, he dressed those raw and bleeding arms of his, and then, though writhing in pain, sat down to await the dawn and Sambi's coming.

He came in due course, with a grin upon that ebony face of his, to find his prisoners squatting on the floor much as he had left them the night before.

"You are ready for me now?" he asked.

"That is so," Craddock drawled, as he turned over on his left side and covered Sambi with a revolver. "I guess you've hit it, my friend. I was never beaten by a nigger yet, and I'm too old to begin now."

Sambi, with all the fatality of his clan, folded his hands over his capacious stomach and waited for what was coming to him.

"My lord is a great man," he said, "and his days will be long on the earth. And behold, I am ready"

With that Craddock shot him neatly and artistically through the centre of the forehead, and he collapsed without a sound on the floor of the hut.

"Well, that's a good job done," Stewer said. "And what's the next item on the programme?"

"Well, I'm not quite sure," Craddock said. "Shall we bury him and say nothing about it, or shall we wait here till Bomba comes back, and tell him the whole story? If we bury him properly, those chaps, when they come back, may think that he was killed in battle; but my idea is to clear out altogether and leave them to draw their own conclusions. What do you say?"

"Clear," Stewer said laconically. "Quick!"