Note: A small part of the text in the copy of "The Strand Magazine" used to prepare this story is missing. The lacunae are indicated with square brackets.

IT wanted but ten days to August Bank Holiday, and already the great watering-place of Sandmouth was packed with visitors. Within the next few days the numbers would be augmented by perhaps another two hundred thousand, but Sandmouth made nothing of that, for they boasted that there was ample provision for half a million immigrants, and the boast was justified.

The Empire Palace of Varieties, that huge and luxurious theatre attached to the Winter Gardens, was packed with people from the stalls to the gallery. Not one popular favourite, but a dozen came forward one after the other and did their best, and, indeed, only the best was good enough for Sandmouth.

In the third row of the stalls Gilbert Lockhart sat with his eyes on the stage. He was by way of being an artiste himself, but for the moment, at any rate, he was free to indulge in a little well-earned leisure. He had come down to Sandmouth for a brief rest before appearing in the Winter Gardens on the evening of August Bank Holiday. He would be the star on that occasion in the character of Señor Romano, the world's greatest exponent on the high wire. At ten o'clock on the Monday night he would go through his marvellous performance on a single strand of copper wire running from one lofty water-tower surmounting the huge glass dome of the Winter Gardens to the twin tower at the other end. Others have done this sort of thing before—the great Blondin, for instance—but then Blondin's performance took place on a rope, and Señor Romano traversed a taut strand of wire two hundred and fifty feet above the ground and absolutely invisible to the great audience down below.

There was not much in the performance, perhaps, as such, but it was a fine exhibition of cool courage and daring. Moreover, it took place in the dark, save for the fact that the performer for the most part was surrounded by a blaze of fireworks, and at any rate the management held the entertainment cheap at the fee of five hundred guineas which they cheerfully paid for it. They got their money back twice over, for of all the draws at that moment attracting huge audiences, Señor Romano was the greatest. It was positively his last performance, too, on any stage, and the Palace people were making the most of it.

Lockhart had not gone into this business from any love of it, for, as a means of making a living, he hated it from the bottom of his soul. But what can a young man do who finds himself at twenty-three utterly penniless, without any profession or business training and face to face with poverty after a public school education and a successful career in the world of athletics at Oxford? The sudden collapse of his father's huge business and his subsequent death had brought about this catastrophe. How Lockhart had drifted into it he hardly knew himself; probably his passion for Alpine climbing had been the main incentive. He had discovered that he had the art of balancing himself on a rope at dizzy altitudes, and thus, little by little, he had found his way into the business. And now, under an assumed name, and unknown to his friends, he had become the greatest wireman of his time. And in the last eight years he had amassed the nucleus of a fortune. His appearance at Sandmouth would be his last, for he had purchased a ranch in Canada, and his intention was to go out to it in the spring.

But he had not met Mlle. de Lara, the famous French dancer, at that time. And this was largely the cause of his sitting there in that packed audience with a moody frown on his forehead and a certain anxiety gnawing at his heart. He was watching the lady in question going through that graceful performance of hers in a little sketch founded on the Mexican rebellion which had been written round her and the other star performer in the shape of Leon Diaz, who claimed, not without justice, to be the champion rifle and revolver shot of the world. In it she had to meet first one and then two fencers armed with rapiers and overcome them in a hand-to-hand combat, holding the position till the hero turned up with his revolvers and his world-famed rifles.

Lockhart was watching the slim, graceful, girlish figure in the white shirt and black silk knee-breeches with something like a dog-like devotion in his eyes. He was fascinated by the wonderful swiftness and dexterity and moved by the exquisite beauty of that fair face. And when it seemed to him that Diaz as the lover was carrying his privileges a little too far something like a smothered groan escaped him.

Sitting by his side was a little man in loud checks, with "low, comedian" written all over him. But Billy Jenks was a kind-hearted soul in spite of his native vulgarity, and Lockhart had a genuine liking for him. Jenks was not performing this evening; like all the rest of his profession, he found it impossible to keep away from the atmosphere of the theatre. And the look on Lockhart's face and that smothered exclamation were not lost upon him.

"Diaz is a beast," he said. "But there is no denying that he is easily first in his own particular line. But she don't care anything about him, laddie."

"I wish I could think so," Lockhart groaned.

"Well, I know I'm right. He's fascinated her, and you are a bit slow, ain't you, old man? No business of mine, of course, but there isn't one of us behind who can't see how the land lies. And he is clever. You've never seen what he can do with a rifle, have you? Of course, there isn't much scope for a gun inside a theatre. But I was in a big circus with Diaz three years ago in California, where we gave evening shows in the moonlight, and, by Gad, that chap can make a gun actually talk as long as there's any light at all. And there's no fake about it either. He can judge the range up to a thousand yards as easy as a man judges the points of a horse. But don't you worry about that. You just go in and win, old man. I'm not a gentleman like you, but I know a lady when I see one, and the girl we call Mlle. de Lara was never brought up to this sort of thing."

Lockhart was silent. He knew that perfectly well. He knew that Mlle. de Lara had been born Lucille Dare, that she was the daughter of a man who had at one time had a high commission in the British Army, and that the art she had learnt as a child for her amusement and the state* of her physical training had become later on her one means of obtaining a livelihood. And Lockhart knew, too, that she hated and loathed all this publicity as much as he did himself. He had met her more than once during the last eighteen months, and all had looked like going well until Lucille had been persuaded to accept one of the leading parts in the sketch which had originally been written for Diaz alone.

[* "sake" in the original; probably a typographical error. ]

The entertainment came to an end presently, and the huge audience filed slowly out. Lockhart found himself presently waiting outside the stage door for a chance of a few words with Lucille. He had not yet shaken 0H Billy Jenks, who was hanging about as if waiting for someone himself.

"All right, old man," he said, "I'1l be off. I can see that you don't want me. But I am your friend, as you know, and if you take my advice you won't quarrel with Diaz. There used to be some nasty stories told about him in California; as a matter of fact, he dared not show his face there. I don't believe the beast would stick at anything. And don't forget that a man like yourself who risks his life on a bit of copper wire might form a tempting object for a bit of treachery on the part of a reckless devil like Diaz. Well, so long, old man, and remember my advice is well meant."

Lockhart drew a deep breath as he saw Lucille coming towards him. There was cold surprise in her eyes as she saw him standing there. It was his own fault, perhaps—he had been somewhat shy and laggard in his rôle of a lover—but he did not stop to think of that at the moment. He felt the blood rising to his temples and tingling to his finger-tips as Diaz emerged from the shadows and laid his hand familiarly on Lucille's arm.

"Don't forget," he said, with an insolent glance at Lockhart, "that you are engaged to me for to-morrow afternoon."

Lockhart kept his temper with an effort.

"I—I was going to ask you to come as far as St. Everards in the side—car," he stammered.

"But if I am too late, why, then, I must go over there alone."

It seemed to him that Lucille yielded for a moment, and then the cold look came back into her eyes again.

"I'm very sorry," she said. "But as you did not mention it this morning I thought you had forgotten. Besides, Señor Diaz is going to drive me over to tea at St. Everards in his dogcart. He has promised to let me drive a little way myself. It isn't often nowadays I get a chance of driving a good horse, and I should be foolish to lose such a chance."

Lockhart turned away without another word; he was hurt and sore, and none the less so because he knew he had largely himself to blame. But he would go to St. Everards and have tea at that charming little seaside village alone. And he had, too, an uneasy feeling that perhaps Lucille would need him.

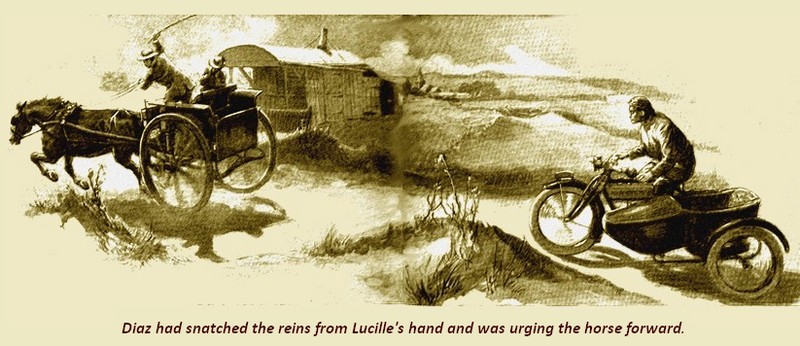

Accordingly, the next afternoon he set out on his motor—cycle about half an hour after he had seen the dog-cart depart and Lucille driving the fine thoroughhred horse of which Diaz was exceedingly proud. Presently he saw them before him on the lonely road over the sand dunes. And then it seemed to him that something was wrong, Evidently the big black horse had got out of hand, for he could see that Diaz had snatched the reins from Lucille's hand and was urging the horse forward. Then, when the danger was past, Diaz began to thrash the high-spirited animal unmercifully. So far as Lockhart could judge, the Mexican was blind with rage and fury, for he suddenly stood up in the cart and, reversing the whip, began heating the terrified animal over the head with the loaded end of it. It was as if some lunatic had suddenly flared out into one of his cyclones of passion.

On and on the helpless horse dashed until, absolutely exhausted, he sank between the shafts and lay in the road. As Lockhart quickened his pace, he saw Diaz jump from the cart and approach the prostrate animal with something in his hand. But it was something that shone and gleamed in the sunlight, and then the full horror of the situation burst on Lockhart. He quickened his pace and threw himself off his motorcycle by the side of the cart. He was just in time to see Diaz, with a face distorted with fury and eyes blazing with rage, stoop down in the road and deliberately cut the throat of the exhausted animal from ear to ear. In the cart Lucille sat like a frozen statue. She was evidently petrified and stricken dumb by this exhibition of raging fury. As Lockhart put out his hands to her she placed her cold fingers in his and he lifted her to the ground. Had he not placed his arms about her she would have fallen. Then she found her speech.

"Oh, take me away, take me away!" she said. "I—I am frightened. Did you over see anything so horrible?"

Diaz rose from his knees and came forward. But not a word did Lockhart say as he fairly lifted Lucille in his arms and placed her in the side-car, which he had not detached from his cycle. There had been just the chance that he might bring Lucille home with him, and he congratulated himself now upon his prudence.

"Don't say anything," he cried to Diaz. "And don't come a yard nearer me, or I'll strangle the life out of you."

A few minutes later and Lockhart, with his precious burden by his side, was racing along the road in the direction of St. Everards.

He [found a] little empty alcove in the tea-[room] and placed Lucille in a seat. [...] dumb, though now she shook [....]ness. Then the blessed tears came—and for a long time she sobbed un[res]trainedly.

"I don't know how to thank you," she said at length. "Oh, why did I come out with that dreadful man? From the very first I have hated and loathed him, and I have been warned against him more than once. I was told that he was dreadfully cruel to his animals. Now, if you—"

"Oh, I know, I know," Lockhart said.

"It was all my fault, Lucille. Only I thought you didn't want to come with me, and I was jealous. I dare say you will say that I have no right to he jealous." She smiled at him gloriously through her tears.

"And I thought you didn't eare," she whispered. "I thought that you were only amusing yourself. Are you quite sure even now, or is it only that you are sorry for me?"

Lockhart acted on the impulse of the moment. They were all alone in the arbour and no one was in sight. And, besides, she was looking at him with those tear-wet eyes of hers in a way there was no mistaking, and her soul was shining in them. He drew her to his side and kissed her passionately.

"There are going to be no more misunderstandings," he said. "Lucille, I never cared for anyone till I met you, and there will never he anybody else. And we are made for one another. You drifted into this the same as I did; you suddenly found yourself without your comfortable home and facing the world as I had to face it. But that is all over now. After Monday I turn my back on this life for ever, and I am going to take you to Canada with me. We both hate the life."

"I've done with it," Lucille said. "At any rate, when I have finished here. And nothing will induce me to appear with that man again. I couldn't do it, Gilbert. I shall tell the management exactly what happened."

The scandal was too great to be concealed; the management was sympathetic; and during the rest of the week the sketch was abandoned. But Diaz brooded, and the expression in his eyes when he looked at Lockhart was bad to see.

"Look to yourself," he threatened, the first time they met. "That is a great performance of yours on the wire, but see that it does not prove a barbed wire for you. I will make that girl my wife yet, in spite of everything."

"Do your worst," Lockhart said. "I'm not afraid of you."

Nevertheless, Lockhart was far from easy in his mind, a fact that he confided to the sympathetic Jenks later in the day.

"It isn't that I'm afraid," he said. "But I'm fearful of my own happiness. Now, just consider, Billy. I've made a good deal of money, I am going to marry the sweetest and dearest girl in the world, and it looks as if a glorious future lay before us. And for the last time on Monday night I am going to risk my life. And it is a risk—a dozen times I have been within an ace of death. The mere thought that it is the last time makes me uneasy. There's more than a chance, too, that Diaz will do me a mischief. I heard just now from one of those Japanese jugglers that the fellow was actually in a lunatic asylum in Nevada three years ago. I tell you I don't like it a bit, Billy."

Billy Jenks was duly sympathetic.

"Look here, laddie," he said. "I believe you are in danger, and the best thing to do is to realize it. I'm all with you, I am. I am only a red-nosed comedian, but I have had my dreams, and I want to help you if I can. You can't go to the police and get them to arrest Diaz, because he has never really threatened you. You can't get that chap locked up till after Monday, anyhow. But you can take precautions, and these are all the more necessary because I know that Diaz will do you a mischief if he can. I found out this morning that he has changed his bedroom to the back of the house where he has his lodgings in Vernon Terrace."

"I don't quite understand," Lockhart said.

"Let me explain. I also, as you know, lodge in the same house; in fact, there are a whole lot of us there. The top back bedrooms in Vernon Terrace overlook the Winter Gardens right between the two water-towers. Anybody up there would have a grand view of your performance on Monday. They could see the fireworks, too, and, of course, there will be a deuce of a noise going on whilst you are on that high wire. Now, our performance will be over at nine, so that we shall be free for your big show. I don't propose to be there at all. I am going to stay at home and keep an eye on Diaz. And I can get one or two of the other chaps to help."

"You think Diaz made that change designedly." ·

"Of course he did. And he's got some deep-laid scheme, too. If he gets you then, nothing matters afterwards, so far as you are concerned. And he won't lose any time about it either. I was thinking about it all last night. And I think I can see a way to get the better of that ruffian and lay him by the heels for many a year to come. Now, listen to me."

As Jenks proceeded to unfold his scheme the frown on Lockhart's face gradually gave way to a smile. He was looking quite himself by the time the comedian had finished.

"That's a good idea," he said. "There's plenty of time to carry it out, too. If nothing happens nobody will he any the wiser, and if, by any chance, Diaz gets to know, then you will be able to prevent him doing anything dangerous."

"I'll see to that," Jenks said, grimly. "I'll use violence if necessary. But if you do get through Monday night all right, then he'll he pretty sure to have another go at you. But if we give him a certain amount of rope, then we shall be able to prove an attempted crime against him and hand him over to the police. You needn't worry, old chap. You must see that everything should come out all right."

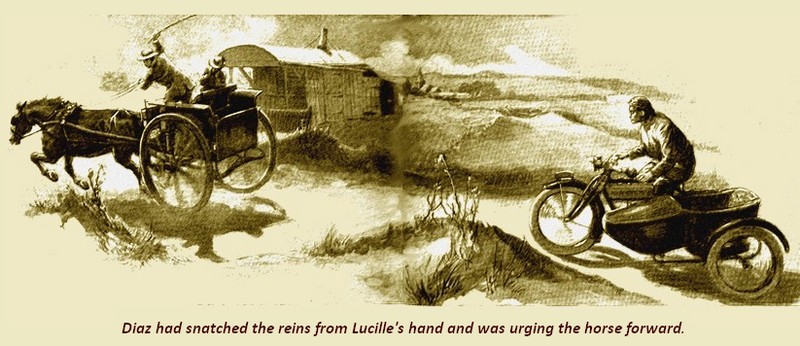

It was nearly ten o'clock on the night August Bank Holiday, and something like two hundred thousand people had gathered there in the grounds to watch the most sensational performance before the public that England perhaps had ever seen. The two big water-towers loomed out high into the sky, and between them, as the spectators knew, was a slender copper wire on which Señor Romano, as they knew him, was to perform the marvellous feat which many of them had come miles to see. He would appear presently through one of the windows of the right-hand tower and cross on that spider web to the far side, a matter of some six hundred feet, and should anything happen to him, he would be dashed to pieces on the glass dome beneath him. In itself the performance was not, perhaps, particularly clever, but it was the peril and danger and the superb exhibition of human nerve and courage that the holiday-makers had come to see.

There was no noise now—no word was spoken. It was as if all the people there were aware how necessary it was that there should be no outburst of feeling and no clamour or hurricane of applause to disturb the performer on his terrible joumey. And so they waited moment after moment, tense and silent and strung up to a pitch that had something of pain in it. Then a rocket soared high into the sky and burst like a bombshell high overhead into a cascade of falling stars. It lit up that white ring of faces for a moment as if they had been so many corpses staring up out of a sea of blackness. There followed another rocket and yet another, and after that a blaze of flares picked out the two great water-towers as if they had been cameos cut out against a background of solid bronze. And then, high up overhead, something seemed to drift away from the edge of the tower and move slowly along the unseen wire. Its outline was blurred and dim, but it was a human figure plainly enough, a human figure with hands outstretched swaying gently from side to side.

A sort of murmur rose from the audience, dull and subdued like the sigh of the incoming tide on a midnight beach. And after that there was a silence more tense and painful than before. From the street outside the walls came the hoot of a motor and the clang of an electric tramcar as it swung along. It seemed like an unseemly interruption, something that was vaguely resented by the packed mass of humanity down there below.

Then silence again, a silence like the darkness of Egypt, inasmuch as it could be felt. Strong men were there, not given to emotion, who swallowed down something in the back of their throats. A woman tittered hysterically and then bit her lip as someone gripped her arm with a force that filled her with pain. The mere fact that this grip came from a stranger mattered nothing. And gradually and carefully the figure on the wire slipped on until it paused half-way between one tower and the other, as if looking down on the pallid faces there—and at the same moment hundreds of fireworks, rockets, and Roman candles and squibs began to play all about the human spider on his copper web up there so far over their heads. Presently came a little whip-like crack faintly audible about the reverberating din and unnoticed by the ears of everyone there. A fraction of a second later the figure on the copper wire swayed backwards and forwards, then before the horrified eyes of the overwrought audience pitched headlong downwards and crashed through the dome of glass into the Winter Gardens below.

It was all done in a flash, a minute fragment of time so short as to be infinitesimal, and yet in that pinch from the duration of a second a people's holiday was turned into a tragedy of mourning. It was petrifaction for a breath, paralysis for a second, and then a letting loose of the simple emotions that broke like a fiood and carried that vast human tide with it. Men groaned and shuddered and women cried aloud as they covered their eyes. And down there on the bandstand amidst the fireworks somebody in authority jumped to his feet and began to roar authoritative words through a megaphone. For a second or two it was as if the man down there was raising his voice against the tumult of a nation. Then first one and another caught the gist of what he was saying and whispered it to his neighbour. The tale fiew from ear to ear quickly as a flash of summer lightning. There was silence again, deep and impressive, then the megaphone spoke once more.

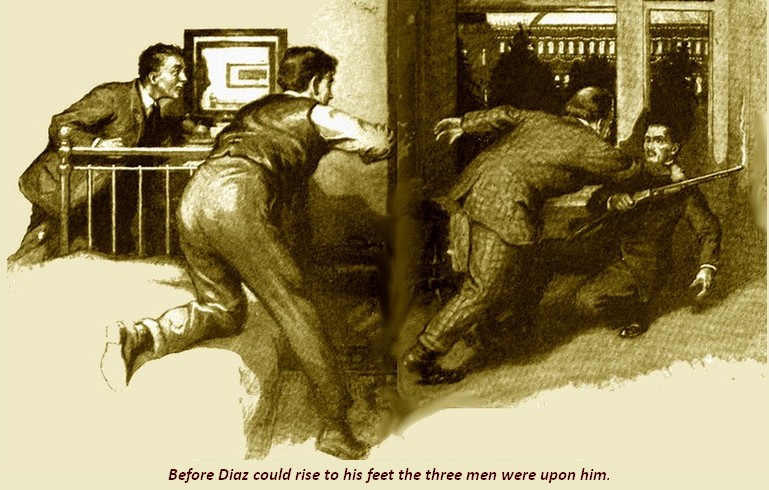

Billy Jenks stood in the darkness of a bedroom in Vernon Terrace looking out anxiously on to the packed gardens below. Behind him in his sitting-room with the door closed two men were waiting for him to give the signal. They knew exactly what they had to do, and they knew, moreover, that when the time came not a moment must be lost. And so Jenks stood there straining his eyes into the darkness, waiting one tense minute after another until he saw that diminutive figure beginning to slide its way from one tower to the other opposite. Jenks was holding his breath now, every nerve in his body thrilling and every sense in him at its highest tension. He saw the first rocket soar high into the sky, he watched the play of the gathering sheets of flame down below. And then from somewhere close by him, almost in his own ear it seemed, he heard a sharp crack like the lash of a whip, and before the sound had died away he moistened his dry lips and whistled. He had just time to see the figure on the wire sway and fall before he realized that two men were behind him.

"It's done," he said, hoarsely. "Now, come on, there's no time to be lost."

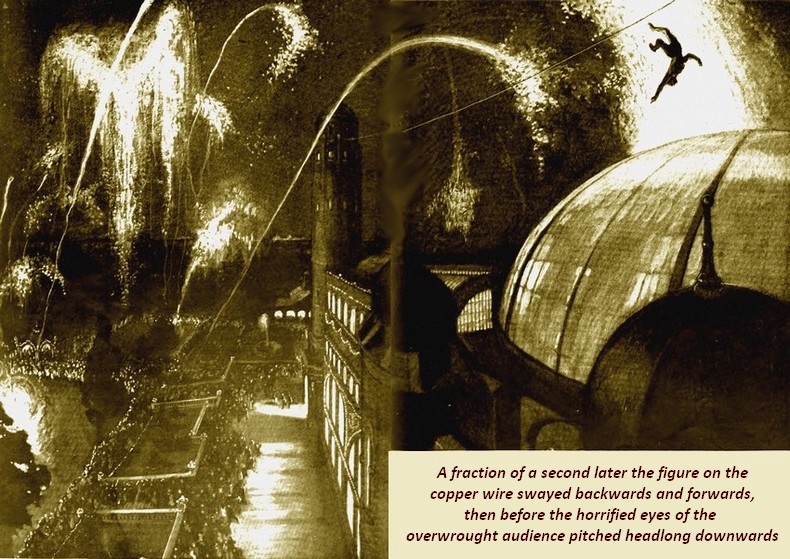

As Jenks said this he opened the bedroom door next to his own. He fumbled inside for the switch of the electric light, and flooded the room with a warm glow. The bedroom window was wide open, and leaning by the sash with a riflc in his hand was Diaz, It had all been done so quickly that even yet a thin vapour of smoke was trickling from the barrel of the Winchester rifle. Before Diaz could rise to his feet the three men were upon him and he was disarmed. He had been caught absolutely in the act, caught within twenty seconds of firing that fatal shot, and he knew plainer than words could tell him that his fate was sealed.

"You murderous scoundrel!" Jenks cried. "Now, what have you got to say for yourself? I saw everything from my bedroom window, and now we have caught you with the weapon in your hand. Anything to say?"

"Not a word,” Diaz replied between his teeth. "I planned it well and carefully, but fate has been too strong for me. And if you want to know if I'm sorry—well, I'm not. If it had not been to-night, it would have been another time."

"We are wasting time here," Jenks said. "Bring the scoundrel downstairs, and I'll telephone for the police."

The man with the megaphone had his audience well in hand now, and every word that he said carried true and clear to the farthest part of the grounds.

"Ladies and gentlemen," he yelled. "There is no cause for alarm, and the tragedy you have been witnessing is no tragedy at all. It is only a little idea on the part of Señor Romano which he has adopted of late to test the safety of his wire. Sometimes the atmosphere makes a difference, as it generally does to high tension wire, so by means of a slender steel cord a dummy figure, the weight of a big man, is worked along the main cable merely to see that it is absolutely safe. By some means or another the dummy must have become detached from the steel cable and, as it swung downwards, tore itself free from the copper wire. We deeply regret that we should have caused you all this distress, but it has been an accident, as you see, and Señor Romano is up there now waiting to begin. If you look up, you will see him for yourselves."

A great hurricane of cheers broke from two hundred thousand throats, cheers of relief and enthusiasm as Lockhart slid along the wire and started his daring perfomance. He had waited up there watching eagerly until he had seen the flash of an electric light three times repeated from a certain house in Vernon Terrace, which told him that the danger was past and that now he could satisfy the demands of his audience without any further fear. He had finished at length in a last blaze of rockets, he was drawing nearer and nearer to safety, and then he took one deep, shuddering breath as his foot left the wire and he stepped through the window on to the upper stage of the tower, a free man, sound in life and limb, a man who saw the long years of happiness and prosperity looming before him from behind the violet darkness of the warm August night.

"We owe everything to the ingenuity of Jenks," Lockhart told Lucille, as the three of them sat at supper an hour later. "I told you that I should be quite safe, but Billy swore me to secrecy, and so I couldn't tell you exactly how it would be done. All the same, I'm glad you kept away from the gardens, for it must have been at painful scene; in fact, I hardly liked to face it myself. Still, thats all over and done with now. Diaz is out of the way and he will never threaten our happiness again. They will probably certify him as a lunatic, which the man undoubtedly is, and he will very likely never be free again. But I don't want to talk about him. I want to talk about our friend Billy here. It was he who guessed what Diaz was going to do, especially when he found out that the Mexican had changed his bedroom, and it was he who hit upon the happy idea of that dummy. It was any odds that Diaz would take it for me, and hehave exactly as he did."

"But suppose he had found out?" Lucille shuddered.

"Oh, I'd arranged for all that," Billy Jenks said, modestly. "If he had tumbled to our little scheme we were going to enter his bedroom by force and keep him a prisoner till the performance was over. We might have done that in any case, but that wouldn't have helped us. We had to prove that Diaz had murderous intentions or we should never have been abe to have kept him out of mischief for the future. Otherwise, he would certainly have had another try. Neat little dodge, wasn't it? And some day, when I have got time, I think I shall turn it into a play. It ought to make a good one."

"Make it a comedy," Lucille smiled. "We have been too near the edge of tragedy to-night."