IF Lord Rupert Tintagel had not put into the harbour of Minchin, the true story of Montague Disney would probably never have been written. Disney says himself that he could not have held out much longer, and that he was fed up with it, which, being translated into the English of his clan, means a dark hint to the effect that he would have blown his brains out. And when you come to hear what happened to him, you will be inclined to extend to him a certain measure of sympathy. As a matter of fact, the port that Tintagel put into was not really called Minchin, neither was his patronymic Tintagel. For the matter of that, the Right Hon. Sir Eben Aza, with half the alphabet after his name, is a nom de plume also. One has to tread lightly in these troublous political times, especially in view of the fact that the Right Hon. Sir Eben Aza was, and is, a pillar of a great political party, and an Empire builder of the first rank.

Now, Tintagel put into Minchin for the sole purpose of procuring a certain herb, without which the 'morning glory' cocktail is a delusion and a vain thing. The herb in question can only be obtained in its virgin sweetness from the mountains behind Minchin, and this important truth had been impressed upon Tintagel by his friend, Bill Venables, who had come out yachting in those seas on the distinct understanding that he wasn't expected to rough it.

"Not that I can't," he said. "But hang me if I see any reason for being put on rations when there's no occasion for it. If you're out for a scrap, then you can count me in it. But this is a pleasure cruise, and I'm not hankering for anything picturesque in the way of Oriental surgery."

So the 'White Woman' put into Minchin, and the lamentable hiatus was duly filled. As most people know, Minchin is a town containing nearly a million souls, and boasts the most cosmopolitan population in the world. It is a delightful, beautiful, utterly wicked and alluring city, as Venables knew; and as Tintagel had never been here before, it was only natural that he should suggest a round of sight-seeing. For the next day or two there was no break in the flow of Tintagel's education, and by the end of the week his clean mind began to hanker for the pure atmosphere of the sea—a little Minchin goes a long way.

"Don't you think that we'd better chuck it?" he suggested.

"There's one more place you've got to see," Venables said. "Now, we're simply bound to look in for an hour or two at Sin-Li's. In a way, it's as good as Monte Carlo."

Tintagel was fain to admit that he had forgotten Sin-Li. Every traveller in the East knew the place by repute, and many thousands of them had visited the shrine. That most of them bitterly regretted the visit afterwards does not in the least matter. It was useless to complain that the odds in favour of the bank were sinfully long. It was also childish to say that Sin-Li was making the income of a Queen of Sheba, and to contend that the authorities ought to interfere. The fact remained that Sin-Li was making that princely income, and the authorities did not interfere. No doubt Sin-Li could have explained their exquisite politeness so far as he was concerned.

The Casino, so called, was situated in the Chinese quarter. It was a long, low building, cunningly surrounded with an air of mystery, and impossible of admission without the token and the password and all the rest of it. There were secret passages and hidden doors and villainous-looking janitors, all calculated to thrill the traveller and fill him with the wine of adventure. It never occurred to him, in his bland innocence, that Sin-Li's tokens might be obtained from any loafer along the beach. The little game was to impress every traveller with the pleasing delusion that he himself was exceptionally favoured, and cause him to be swindled out of his money joyously and without complaint.

Therefore it was on a Saturday evening that Tintagel and Venables found themselves in the big room, where a form of roulette was being played. Down both sides of the table twenty or more people were seated. They represented every nationality under the sun. Taking out some half-dozen of them, it might have been fairly assumed that there was not an honest sixpence in the room. But Sin-Li was too wily a bird to judge by appearance, and many a battered-looking wayfarer there had left the nucleus of an income in the Chinaman's pocket.

"Pretty thick lot," Tintagel whispered.

"Oh, they've got the rocks, all right," Venables muttered in reply. "Look at that chap yonder in the blue overalls. He hasn't been washed for a week, but his pockets are full of dust, all the same. And that little Jew opposite—you wouldn't think he's one of the biggest bill-discounters in Europe. But look here—we shall have to have a dash, you know. Sin-Li's got no use for mere spectators. Put your money down."

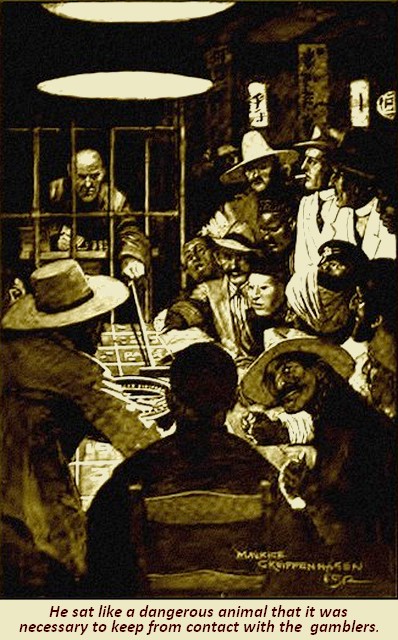

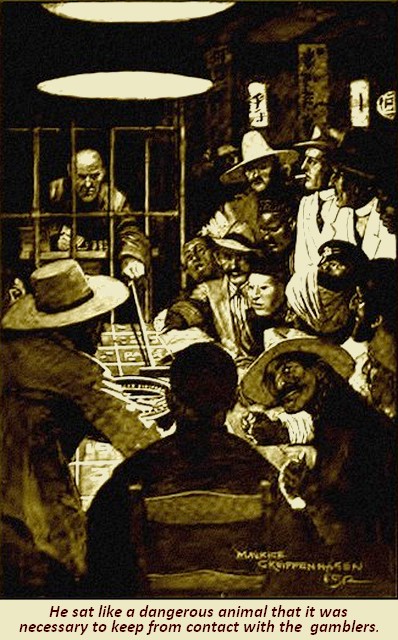

Tintagel carelessly covered a number with a few sovereigns. It was a matter of indifference to him whether he won or lost. He did not doubt for a moment that the roulette wheel had been the subject of some ingenious mechanical manipulation. He was more concerned with the hebdomadal crowd about him. At the top of the table, raised above the floor, sat the cashier, who seemed to combine that duty with that of a croupier. His long, thin hands extended through the bars of a veritable cage, wherein he sat like a dangerous animal that it was necessary to keep from contact with the gamblers. He paid the winners and collected the losses of the losers by means of an expanding rake capable of reaching to the far end of the table. On the little desk in front of him lay a pile of notes and gold. With his dead-white face and bald head, with his absolutely expressionless eyes, he reminded Tintagel unpleasantly of a trained ape rather than a human being. The man appeared to be devoid of emotion of any kind; his mask-like face was as blank as that of a statue.

"Is the chap dangerous?" Tintagel asked.

"No, but the gamblers are sometimes," Venables said drily. "This place has been raided by desperadoes more than once, but Sin-Li doesn't mind that much, because it is an advertisement for the house. Sometimes the police come here, but it's only a dress rehearsal, after all. At the first sign of trouble, the lights go out and the cashier lowers himself into a sort of vault down below. He's in a kind of lift, as you see for yourself, if a revolver appears, he presses a button, and he's not there any more."

Tintagel was barely listening. The white-faced man in the cage fairly fascinated him. He paid no heed to the fact that his third venture at the table had won him a small stake, and then on his little pile of sovereigns the man in the cage had deposited a clean, crisp Bank of England note. The face of the note was folded inward, but it was impossible to doubt what it really was. Venables brought his elbow sharply into Tintagel's ribs.

"Don't you want that fiver?" he asked. "That little Kanaka boy in the canary-coloured waistcoat will nick it to a certainty if you don't pick it up. Don't scatter it, my boy. If you get a reputation of that sort, you may find a knife in your ribs before morning. Pick it up, you ass!"

Tintagel pulled himself back to the affairs of the moment. He reached out for his gold and paper with the intention of cramming them carelessly into his pocket. His glance fell upon the clean white bank-note, then his teeth came together with a snap. Just for an instant there was a startled look in his eyes as he folded the note and deposited it with more than usual care in his cigarette case. Venables smiled at the action.

"Keeping it as a souvenir?" he asked.

"You can put it that way, if you like," Tintagel replied.

He turned away, as if still deeply interested in what was going on around him. But the only really fascinating thing there was the man in the iron cage. He seemed to see everything without looking; he appeared to do everything like one in a dream. Every now and again he swept the table with his almond-shaped eyes—eyes that had no vision in them, or so it seemed. The atmosphere was getting oppressive—a longing for fresh air came over Tintagel. He turned eagerly to Venables.

"Let's get out of this," he said. "It's pretty vulgar and commonplace, after all. I've had far more fun than this at San Francisco. What do you say to a supper at Pinsuti's, on the balcony?"

"And some of those little green oysters done in cream," Venables suggested. "You can count me in."

They sat presently on the flower-decked balcony in front of Pinsuti's, lingering over their coffee and cigarettes. It was a glorious, scented night, with a great moon like a silver shield hanging in the blue, and a powder of diamond-pointed stars gemming the heavens. At their feet lay the city, picked out with a thousand points of orange-coloured flame. It was a night to sit silent and at peace with all mankind. But Tintagel was restless and moody, so that the easy-going Bill noticed it at last.

"Not feeling up to the mark, old chap?" he asked.

"Oh, I'm all right," Tintagel replied. "I was thinking. Did you ever hear the story of poor old Montague Disney, and his strange disappearance from London three years ago?"

"Oh, nothing but club gossip. I was away shooting in the Rockies at the time. I never knew much of Disney, but he always struck me as being a particularly good sort. A fine sportsman, too. Not the sort of chap you'd expect to commit forgery, and all that kind of thing. Didn't he rob the West Asian Bank of a lot of money? Had a post of trust there, hadn't he?"

"Well, that's what they said," Tintagel went on. "One fine morning Disney suddenly vanished, and from that day to this no soul has ever seen or heard of him. His father, old Sir Thomas Disney, was terribly cut up about it. He always swore there was a misunderstanding somewhere. But the money was gone, and Disney was gone, too, and there was no other conclusion to come to. The Right Hon. Eben of that ilk was chairman of the bank, and he did his best to hush the thing up. I understand the old man behaved very well, especially seeing that he was not at all on good terms with Disney. You see, Disney and Beatrice Aza—"

"Oh, I remember now," Venables interrupted. "Lady Frances Aza told me something about it. Weren't Disney and the girl secretly engaged, or something of the sort? I know that Lady Frances liked him, but old Eben had a German Prince up his sleeve for the girl."

Tintagel rose from his seat and began to walk up and down the balcony.

"There's something infernally wrong about the whole business," he said, "and, so far as I'm concerned, I should like to hear Disney's side of the story."

"You'll never do that," Venables muttered.

"Now, there, my dear chap, is where you're wrong. I'm going to hear Disney's story if I stay here a month to get it."

"Do you mean to say he's here?" Venables demanded.

Tintagel came back to the little table with the shaded lights, and laid his cigarette case on the cloth. He took from it the folded bank-note and handed it to his companion.

"Your winnings." Venables smiled. "Is there any particular virtue about that fiver?"

"Turn it on its back," Tintagel said curtly, "and tell me what you think of what you find there."

Venables fairly started as he looked at the paper.

"It reads like a message," he said. "'If you have any spark of the old friendship left, for Heaven's sake get me out of this. Prisoner. Caution. Dangerous.' Now, what on earth does it all mean, Rupert? Do you mean to say that Disney—"

"Wrote that message on the back of the note," Tintagel said firmly. "My old pal, and the one-time lover of Beatrice Aza, is the poor devil in the cage at Sin-Li's. There can be no question about it. And now what are we going to do?"

"It seems incredible. Why, the man in the cage looked a Mongol to the life! It can't be Disney."

"I'm equally convinced that it is, Bill. He's been cleverly made up for the part, and he's a prisoner, too, if that message means anything. I wonder how long the poor wretch has been there? Just think of his agony of mind, waiting day by day and month by month for the sight of a friendly face and the chance of communicating with the owner of it! We've got to get Disney out of this, my boy. There's an ugly story behind it all, and I'm going to get to the bottom of it, or perish in the attempt. I need not ask if I can count upon you, Bill."

Venables smiled. It was the kind of invitation that specially appealed to him.

"Oh, rather!" he said. "But how are we going to work it, old son? We can easily kick up a diversion in the gambling saloon, but that chap's in a cage for all the world like a captive tiger."

"We shall have to try and communicate with Disney in some way. I don't see why we shouldn't send him a message in the same way as I got mine. If we go back there, he will be certain to know that we have returned for the purpose of giving him a hand. How long does the gambling go on?"

"My dear chap, practically it never stops. I believe at three o'clock in the morning, for a couple of hours, things are slack. Now, the best thing we can do is to sit down and write a brief list of questions on another bank-note, so that we can get Disney to answer them. He'll tumble at once to what's going on, and he'll take precious good care that you back one winning number, at any rate. When shall we start?"

"Why not now?" Tintagel asked.

An hour later and the two were back in the saloon again. The plot called for caution, and Tintagel lost three mains running before he ventured to put the bank-note on the number he was backing. A weary half-hour passed, then the rake shot down the table, and Tintagel eagerly grabbed at the piece of paper. There were but a few words scribbled on it, but they sufficed—

"Make a disturbance—the message ran—both stand close to cage. When lights go out jump on top."

Venables nodded approvingly as Tintagel whispered the words in his ear. To stroll to the top of the table was an easy matter and devoid of suspicion, but to get up an altercation was a different thing altogether. An inspiration came to Venables. He turned and caught the eye of the man in the cage for an instant. His lips framed a word or two, the left eye of the man in the cage drooped slightly, and then deliberately the rake placed a pile of gold on a wrong number. Instantly the hairy claw of a pirate in a red cap reached for it, only to meet the fingers of a gaudy Malay, who was, in truth, the rightful owner. Like a flash, the whole room rose in confusion. A sea of angry faces was turned in the direction of strife. A knife flashed out, there was the quick crack of a pistol-shot, and instantly the place was in darkness.

Not a moment did Tintagel and Venables hesitate; they reached for the cage, and climbed like cats to the top. The cage gave a convulsive jerk, and, as they sank into the unknown, they could hear the tornado of cries and yells. Revolvers were being used freely now.

"I guess those chaps will be busy for a bit," Tintagel said, as the cage stopped with a jerk. "This looks like our opportunity. For Heaven's sake, light a match!"

The little spot of flame flared out in the gloom and fell on the face of the man in the cage. He was striving with all his strength to force back the grating.

"Give me a hand!" he whispered hoarsely. "Pull at the third bar. This infernal thing opens from the outside."

Tintagel needed no further bidding. He laid his hand on the bar and wrenched the door of the cage open. The man inside fairly tumbled into his arms. Overhead the hideous din was still going on.

"Now, then, wake up, old man!" Venables cried. "This glorious chance can't last much longer. I suppose that rascal Sin-Li and all his gang are upstairs by this time. The question is, do you know the way out? It's no use asking for trouble. Do try and pull yourself together, Disney."

Disney checked a sob in his throat.

"I'll try," he whispered. "I'm just a bit dazed by this good fortune of mine. I can't tell you how good it is of you to come and help a poor devil—"

"Oh, forget it!" Tintagel snapped. "Do you know the way out, or not? And shall we manage to get into the street without appearing unduly offensive?"

"I know the way," Disney explained. "We shall have to fight, though. Sin-Li's not the man to keep all his eggs in one basket. If we had a revolver amongst us—"

By way of reply, Tintagel pressed a neat little Webley into his hand. Disney reached for a switch, and instantly the narrow passages were flooded with light.

"This way," he said. "Come quickly."

They emerged presently into a wide corridor, where two coolies lay on a mat smoking. Before they could rise, Venables had dashed forward. He caught each by the nape of the neck, and brought their heads together with a smash. A snore from one, a kind of whine from the other, and the figures lay there as if asleep. At the top of a flight of stairs a Chinaman strutted. As he looked down and opened his mouth to give the alarm, Tintagel fired. The man threw up his arms and rolled down the steps. It was no time to stop and inquire what had happened to the Chinaman, for here was the door leading to the street, and safety was beyond. The lock gave at the third revolver shot, the door fell back, and the sweet, cool night breeze came refreshingly to a trio of heated foreheads.

"My word, it's like Heaven!" Disney said. "But what are you fellows going to do with me? I couldn't show up at any decent hotel in this plight; and even if I did, Sin-Li would have me in his clutches before night. The police? They are all in his pay. If I could find a hiding-place—"

"I've got the yacht here," Tintagel exclaimed. "I came on shore with Venables in the dinghy, and she's now tied up at the wharf. As they will all have turned in by this time, it won't be a difficult matter to smuggle you on board. Then you can have a bath, and we'll fit you up in some Christian clothes. By this time to-morrow we shall be far enough away from Minchin."

An hour or so later, Disney emerged from his cabin, clothed and in his right mind. It was not till he had supped and drank some champagne that he began to talk.

"Well, it's a long tale," he said, "and perhaps you'd better let me tell it in my own way. I'm not used to sympathy and kindness, and, when I think what you chaps have done for me, I am inclined to feel a bit hysterical. Now, don't you run away with the impression that I was hiding in that devil's parlour where you found me, because I wasn't—I was a prisoner there. Neither did I run away from England when that money disappeared, because I didn't. I was sent here on a secret mission by Sir Eben Aza, and no one was to know what had become of me. Now, tell me, how is that moon-faced son of a Pathan getting on?"

"Still high in the councils of the nation," Tintagel said drily—"still one of the pillars of his party. But you must not sit there uttering libels against so distinguished a philanthropist as the Honourable Eben."

"A greater rascal never drew the breath of life!" Disney said vehemently. "Oh, I know he's as rich as Croesus, I know he's the respected chairman of a dozen prosperous companies, and I also know where he started the nucleus of his fortune, and from whence he derives a princely income to-day. Sin-Li is only a paid servant—a mere blind. The owner of the place we've just left is Sir Eben Aza, and I can put my hand on three men who remember him when he first started.

"Now, I found this out three years ago. I was always fond of fiction, and I used to go pottering about down Shadwell way, getting local colour from the sailor scum from all over the world. And that's the way I tumbled upon the story of Eben Aza's early history. When he tried to prevent me from marrying his daughter, I was fool enough to tell him what I knew. I admit it wasn't playing the game exactly, and if I did wrong, Heaven knows I have suffered for it. The old blackguard behaved all right at the time—at any rate, he thoroughly deceived me. Fancy that man being the husband of Lady Frances and the father of such a girl as Beatrice! Well, he laid a pretty trap for me, and I walked into it with my eyes open. When I realised the truth, I was stranded here absolutely penniless, my good name was utterly gone, and no one would have believed my story. What was the good of going back to a certain term of penal servitude? At any rate, I would spare the old people that indignity. I suppose I lost my nerve—anyway, I sank till I was literally starving. One of Sin-Li's blackguards gave me a meal one night and a drink, and when I came to my senses, I was in that den, where I have remained all these years. And Sin-Li had the audacity to tell me that he kept me there because I was the only cashier he could ever trust with money. Just think of the irony of it! There I was, day by day, hoping against hope, and praying for some friendly face under the lights of the tables! It was that hope alone that saved my reason. Then at length you two good fellows came along, and I took my chances. If I could once get away from that den, my idea was to make my way back to England and tell my father everything. I've got a weapon in my hand now, and every word I say I can prove to be true. Heaven knows I have suffered enough, but it isn't vengeance I want. For the sake of the girl I love, and who loved me, I am prepared to keep her father's shameful secret. But he must wash his hands of that gambling den, and he must give my good name back to me. And that's about all. I needn't insult two real good fellows like yourselves by suggesting that this is a sacred matter between us, because it would be merely wasting my breath to do so. All I ask you to do is to lend me a bit to go on with, and land me at some port from whence I can get a quick passage home. And I won't try and thank you, for, when I think of your kindness to me, it makes my eyes feel queer and—oh, dash it, you chaps know what I mean!"

* * * * *

IT was six months later, and the 'White Woman' was sunning herself off Corfu, and Venables and Tintagel were sprawling on the deck to the accompaniment of post-prandial cigarettes and coffee plus some recent newspapers. A queer little chuckle broke from Tintagel's lips, and Venables looked up inquiringly.

"Anything special in the paper?" he asked.

"Well, what do you think of this?" Tintagel responded. "Give me your ears. 'An engagement has been announced, and a marriage will shortly take place between Miss Beatrice Aza, only child of Lady Frances and the Right Hon. Sir Eben Aza, of 725, Grosvenor Square, and Marion Castle, Bucks, and Mr. Montague Disney, son of Sir Thomas Disney, of Tower House, Devon.' What do you think of that, my friend?"

"Then that's all right," Venables said lazily.