GORDON HARLEY was thinking it over. He sat there alone outside the camp, on the high ground overlooking the fever-stricken valley, where that distinguished patriot Don Miguel del Carados was constructing the railway which was eventually to make the State of Tigua prominent amongst nations. But that was a long way off yet—as far off as was the civilisation that the soul of Gordon Harley coveted. Just at that moment—in fact, at any moment during the last month or two—he was fed up with the man who had lured him away from Western joys to this, the most beautiful and at the same time the most monotonous spot on the continent of South America.

And that fat and oily Spaniard had been so plausible about the whole thing, too. He had painted Tigua as a sporting paradise—just the very place for a man of means who was looking for things to kill; just the sort of thing for a man who had recently come into a lot of money, and who had turned his back joyfully on the medical profession, and who hoped never to handle a stethoscope or study the colour scheme of a human tongue again. This had all taken place one starry night in the patio of a Charlestown hotel, where Del Carados was taking in stores for his pet railway. And, besides, he wanted a doctor badly. There were fifteea hundred workmen of sorts on the railway, mostly natives, with a few Europeans gathered without testimonials from various quarters of the globe, and if there was one drawback to that earthly paradise in question, it was an occasional outbreak of malaria in the rainy season.

"You come, along with me, my friend," the Spaniard had said. "You come and stay just as long as you like—a week, a month. I will put you up, and you shall be my honoured guest. The valley is a sporting paradise."

And Harley, having nothing else to do, and in the first flush of his new fortune, had gladly consented. He had come there by sea, of course, and up a yellow river flowing through a swampy country to the valley where the few miles of rails were under construction. It was a tedious journey, and a somewhat intricate one, but Harley had not worried himself much about that at the time, for his mind was full of jaguars and crocodiles, and such wild game, and, indeed, for the time being, he had all the sport he needed.

And then gradually the truth began to dawn upon him. Those fifteen hundred or so of men who toiled and sweated in that mango swamp, where the miasma rose at evening, and the whole universe reeked with the smell of rotting vegetation, were no more than so many prisoners. They were well fed, it was true, they had strong things to drink and pungent tobacco to smoke, and, as to the few Europeans, they were perfectly happy in the knowledge that they were well outside the long arm of the law. But without money it was impossible to get away. Even if they had possessed the necessary funds, it would have been equally difficult, because nobody but Del Carados and one or two of his trusted Mexicans knew the secret of the way down the river, for the Rava had many tributaries, and all but one of them led to the mud swamps, which meant desolation and death and the feasting of the vultures that abounded there.

But all this had come to Harley gradually. There was nothing brutal about the Spaniard, nothing of the slave-driver, for he was inclined to be fat and scant of breath, and, moreover, possessed a fine fund of humour of his own. He was candid, too. The scheme was to complete the railway up there into the mountains, and bring the copper ore down to the coast to be smelted. Once this was down, then the copper proposition was placed on a paying basis. This represented considerable wealth to the little tin Repubhc of Tigua, and in time much kudos for Del Carados, who began to see his way to the presidency of that delectable Republic, For Del Carados was a politician more than a statesman, which comes to much the same thing, and is a better paying proposition in the long run. And Del Carados had no ambitions. He did not want statuea in his honour, he did not hanker to become permanent President of the Republic—six months' manipulation of the national treasury funds filled up the measure of his ambition. In fine, he was a cheery, fairly good-natured rascal, who loved but two things in the world—his own comfort and a particularly fiery brand of Scotch whisky which was known in violent circles as the Clan MacTavish.

It was impossible, therefore, for anyone to leave the valley of the Rava River and the work on the railway save at the Spaniard's good-will and pleasure. He was essentially monarch of all that he surveyed, and before very long, it became quite plain to Harley that he might, unless some extraordinary piece of luck came his way, regard his appointment as medical officer to the forces as a permanent one. In other words, he was as much a prisoner as the humblest labourer who wielded a pick or a spade.

So far, there had been no outbreak of hostilities between the two men, though they perfectly understood one another, and Del Carados would smile his most genial smile when Harley crept back into the camp after three days' absence, a mere mass of skin and bone. Despite his weakness, and the fact that he had been looking death in the face for the last twenty-four hours, he had spoken his mind quite freely to Del Carados as they sat in the latter's hacienda over the evening meal. A bottle of the Clan MacTavish stood hospitably on the table, but Harley had waved it aside contemptuously.

"Now, listen to me," he said. "I have had about enough of this. I came here for two or three weeks as your guest, and to do a bit of shooting, also to act generally as a doctor until you could get someone to replace me."

"I could never do that," the Spaniard said genially. There was a menace in his tone at the same time.

"Oh, that's what you mean, is it?" Harley said between his teeth. "Well, it's just as well we should understand one another. I am a prisoner here. You know I can't get away without your consent, and I suppose I can stay here and rot, for all you care. I am not concerned with your native workmen, because they are happy enough, and as to your European scum I hold no brief. But you're a blackguard, Del Carados, and you know it. If you have no sort of sympathy with me, you might, at any rate, send those Americans down to the coast."

"And do without my evening's entertainment," Del Carados said, with a pained expression. "They came here cheerfully enough. I found them at Charlestown, stranded high and dry, with not a dollar between them. And am I not paying them fifty dollars a week? What more would you have?"

"Well, you are promising them fifty dollars a week, but Mrs. Vansittart tells me that neither she nor her husband have ever seen the colour of your money. Send them off, at any rate."

Del Carados smiled as he rolled himself a fresh cigarette. The humour of the situation evidently appealed to him. The Americans in question were two vaudeville artistes who had found themselves stranded owing to the backsliding of a manager and the subsequent disappearance of the treasury. They had been literally starving in Charlestown when the genial Spaniard had found them, and were only too glad to avail themselves of his glowing offer, which, it must be confessed, had been painted in alluring colours by one who was an artist in words. They sang and danced and played the Spaniard's jangling piano for his amusement night after night, what time he sat listening, soaked in his beloved Clan MacTavish, and applauded with large-hearted generosity and fine discrimination. The engagement of these people had been a stroke of genius on Del Carados's part, and he was not anxious to see the last of them.

"No, no, my friend," he said. "They are quite happy here; they have been happy here for nearly a year. What more could they have? They are well paid and well fed, and they have only to amuse me for an hour or so after dinner. And look you, Senor Harley, don't you go too far. We have been good friends up to now, but—"

And so for the moment Harley gave it up as a bad job. He was sitting out there, in the afternoon, under the shade of a big palm tree, chewing the cud of sweet and bitter reflection. He was contrasting himself, in his soiled and ragged linen suit, with the happy man who had set out, a year ago, to see the world, rich in health and pocket. And here he was, just as much a prisoner as if he had been legally sentenced to a long term of imprisonment. And there was no escape; he had tried that once, and he had no stomach to repeat the operation, for the horrors of that eight-and-forty hours in the mango swamps, with the snakes and the mud and the dull speculation in the eyes of the crocodiles, was still upon him. It was no wonder, therefore, that Del Carados was prepared to take risks, for he was safe enough, and far beyond the reach of any pro-consul.

Harley took a photograph of himself from his pocket and gazed at it with the sentimental eye of one who regards the features of some beloved dead-and-gone departed.

"And so that's me!" he murmured. "Good Heavens, impossible!"

"I was just asking myself much the same question," a voice broke in, as a woman came down the slope and seated herself by Harley's side. "I don't think my friends in New York would recognise me, Mr. Harley."

It was the vaudeville artiste who called herself Muriel Vansittart who spoke. She was slight and pretty enough, light-hearted and vivacious in the ordinary way, but pale and thin now, though there was a certain gleam of courage in her eyes that Harley had learnt to admire.

"Yes, it's pretty rotten, isn't it?" he said. "But what can we do? Try and escape? I have had some, thank you. I prefer to stay where I am."

"Yes, I know," the woman said. "Bill and myself—that is, my husband, Vivian Vansittart—have had over a year of it. Mr. Harley, I am going out of my mind. I can't put up with this much longer. You don't know what it's like when the rainy season comes on. The weather breaks up suddenly, the glass drops about twenty degrees in five minutes, and half the camp is down with ague. They would have been all dead long before now if it wasn't for the quinine. Why, I've seen them swallow as much as would stand on a dollar! I haven't had it, and Bill hasn't had it, because we are both absolutely T.T. But it's dreadful, and I can't stand another rainy season here."

"Pretty close now, isn't it?" Harley asked.

"Yes, the rains may come at any time. Now, Mr. Harley, listen to me. I have got an idea. You're a doctor, and know all about drugs. You have the run of the store, and you do pretty well what you like. Oh, I have worked the whole thing out; I have been lying awake at night, thinking it over for a week. Now, supposing one of these early nights, when that fat old scoundrel is enjoying himself and is full of whisky, you drop a few grains of something soothing in his glass."

"What good would that do?" Harley. asked.

"Oh, I am coming to that presently. Now, I've been making inquiries, asking artless questions, and I have discovered that Del Carados has only got two cases of whisky left. In about a week he will be sending down to the coast for another supply."

"You mean we might try—"

"Oh, no, I don't mean anything of the kind," the actress said impatiently. "Now, whisper!"

For a minute or two Mrs. Vansittart murmured eagerly into Harley's sympathetic ear. Gradually a smile that was cousin to a grin creased his lean, brown features.

"Well; it's worth trying," he said at length. "It's risky, but Del Carados would do anything rather than go short of the Clan MacTavish. We'll try it the very first day that the weather shows signs of breaking up."

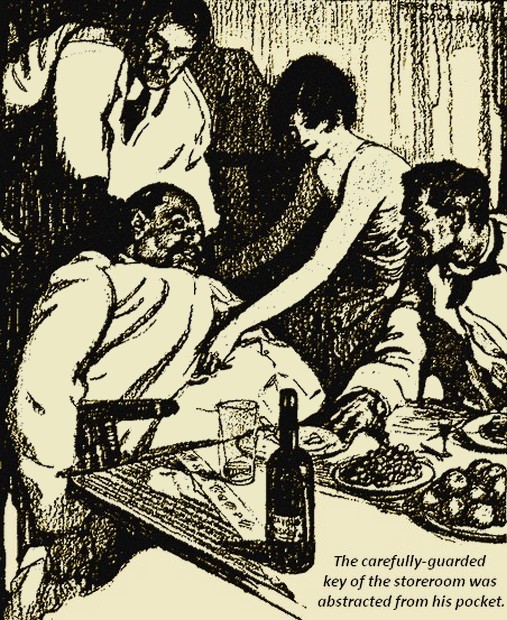

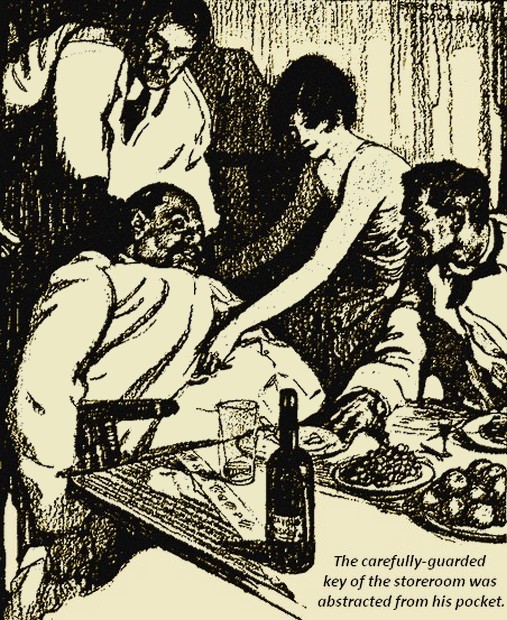

That night, as they say on the cinematograph picture screens, the thermometer dropped nearly a score of points, and for a space Harley was busy in handing out doses of quinine to the shivering natives who clamoured about his hut. Then he crossed over to the hacienda and dined more or less riotously with his genial host and the two American artistes. It was nearly midnight before the Clan MacTavish had got in its genial work, aided by a few drops from a bottle in Harley's drug store, and the Spaniard slept peacefully in his chair. A few moments later the carefully-guarded key of the storeroom was abstracted from his pocket, and for the next hour or two Harley and his companions were exceedingly busy. Then they went off to their respective quarters, hoping for the best.

It was well towards midday before the Spaniard burst into Harley's hut. He was wild and unshaven, untrussed as to his points, and generally bearing about him the unmistakable signs of what is graphically described as "the morning after the night before." The illuminating metaphor can go no further.

"What you've done?"he foamed. "You've robbed me, you've swindled me! You break into my storeroom, you steal all my Clan MacTavish, you evaporate every grain of quinine! Is it a joke? Because it is like to be expensive. You dog, you tell me where those go, or I shoot you!"

The Spaniard's careful English had disappeared in the stress of his emotion. He was truculent enough, but at the same time there was an imploring gleam in his eye that was not distasteful to his prisoner.

"Oh, so you've found out, have you?" he said coolly. "Well, now, listen to me. You can shoot me, if you like, you yellow dog, and you can murder that plucky little American woman and her husband, but it won't bring your whisky back again, and you can't live without it. You'll be dead in three days without your diurnal bottle of Clan MacTavish. And that's not the worst of it, my cheerful old sport. You let those peons know that you've run out of quinine just at the beginning of the rainy season, and they'll tear you in little bits. Now, take my advice and look at the thing in a rational light. You lured me here under false pretences, and made a prisoner of me, just as you did those two American artistes. You haven't the least intention that any of us shall see the coast again until this railway of yours is finished."

"You will never see the coast again!" the Spaniard hissed " You will all be shot in an hour!"

"Oh, I don't think so, dear old thing. You daren't do it. Just think of having to live without your beloved whisky for a whole fortnight! No more long amber-coloured drinks dashed with soda and cooled with chunks of ice, no more happy evenings when you are beautifully fuddled with that comfortable Charles Dickens sort of feeling under that big yellow waistcoat of yours! My dear chap, you really couldn't do it. Now, don't check that natural humour of yours, but try and recognise the funny side of the situation. No drinks and no quinine, and a big riot amongst the peons the first time the glass goes down! Look here, I'll make a bargain with you. I've worked the whole thing out, and it's just like this. You send us down the river this morning as far as the Great Mango Delta. Give us a canoe and some provisions and one of your paddlers to put us on the right way. When we get down to the delta, we shall be all right. Now, if you'll do that, I'll promise on my word of honour to send you back word where the quinine and whisky are to be found. If you like to refuse, and you think you can do without your beloved Clan MacTavish for a fortnight, and you don't mind running the risk of being torn to pieces by the peons, well and good. It's for you to say."

Del Carados swore and threatened, he wept and cursed, and called down the vengeance of all the saints in his calendar on Harley's head, but the latter merely smiled. Then the Spaniard went away with a final threat of instant dissolution, only to return in an hour or two, looking more haggard and dejected than before, and prepared to make terms. He came with the Americans, possibly in the shape of hostages, but they were both as determined as was Harley himself. And so another hour or two passed in fruitless negotiation, till lunch-time arrived, finding Harley still master of the situation.

"It's no use," he said. "We've had this over half a dozen times already. And my friends here are just as determined as I am. Now, sit down, like a sensible man and the born humorist that you are, and talk the matter over. Have some lunch; help yourself to some of that chicken."

"I could not eat a mouthful," Del Carados said, in hollow tones. "I have eaten nothing to-day. My mouth, he is parched, and my tongue, he is dry as a piece of leather. Now, come, my dear friend, this joke has been carried far enough. Tell me where that whisky is, and where you've hidden the quinine, and all shall be forgiven."

"It is forgiven now," Harley said drily. "Even your bitterest enemy would be sorry for you if he caught sight of that face of yours at the present moment. But it's no good, Del Carados. We can't die more than once. Neither can you, but your death promises to be a lingering one."

Del Carados collapsed into a chair and openly bewailed the day that he was born. He tore his hair, he lapsed into strange tongues in a vocabulary that suggested the past master in the art of profanity, but all to no avail,

"If I could do that," Vansittart drawled, "guess I could command a record salary in one of the New York theatres. Say, Don, what's your figure for a course of lessons?"

Del Carados sat up suddenly. There was a certain air of dignity about him now as he spoke.

"I am beaten," he said., "Other great men have been beaten before me, but few of them know how to recognise it. Ladies and gentlemen, you have got the best of the future President of the State of Tigua. Behold, I capitulate—it shall be just as you desire. But before I accompany you myself as far as the Great Mango Delta, in the name of Heaven, I implore yon to find me one little drink, a ghost of a one "

"Not a drop," Harley said firmly. "No, the sheen of Clan MacTavish shall not shine for you until you have earned it. Now go off and get everything ready."

It was barely an hour later before a properly equipped and provisioned canoe dropped down the river, past the alligator swamps, in the direction of the delta. At the prow two stalwart paddlers were being urged on by the dejected Spaniard, whose melancholy, however, did not seem to interfere with his flow of expletives, so that it wanted still an hour to sundown when at length the Mango Delta was reached. From this point the Spaniard and his peons would make their way back on foot, and Harley calculated with grim amusement that Del Carados would have earned the cherished Clan MacTavish before he got it.

"We shall be quite all right now, Don, thank you," he said. "The way is clear enough. Now, you and your men had better get out, and we will tell you where to find that which is lost. You tell him, Mrs. Vansittart."

There was a pleasant smile on the little actress's face and a sparkle of amusement in her eyes as she leant forward and addressed the man standing on the bank.

"You won't have very far to look," she said sweetly. "You'll find your two cases of whisky hidden away in the storeroom behind other empty cases; and, as to the quinine, it is packed up in blue paper parcels and mixed with your sugar rations. You'll know it by the taste easily enough. You see, we hadn't any time to hide the stuff anywhere else, and we knew perfectly well that the storeroom was the last place where you would look for it. Good-bye, Don Miguel del Carados, good-bye, and, if we ever meet again, then I'll probably stand in the witness-box and give evidence against you. You don't look particularly happy now, and you'll look less happy still when an American gunboat comes nosing up the river, asking awkward questions."

Del Carados, from the bank, made a profound bow in his best Spanish manner, but the smile on his face was a sickly one, and the language that he used under his breath is, perhaps, best left to the imagination.