The house-steward looked at the first footman, and the footman turned to the chamberlain. The latter was clinging to the Praxiteles bust for support. A row of silk-stockinged lackeys stared helplessly. Nothing like this had happened since the House of Ravenspur was first founded by William of the Ravenspur in the year of our Lord 1491. That the thing could have taken place at all in Ravenspur House, Grosvenor Square, was incredible. In a vague way the chamberlain blamed The Courier. Possibly The Comet had something to do with it. If not, why had this riot suddenly broken out in the West End?

It was five minutes to eight, and somebody had rung the hall bell. This was natural enough, seeing that his Grace was expecting five friends to dinner. The door had been opened with a rigid regard for high ceremonial by the exactly proper functionary. Then there had appeared, not the traditional gentleman in a fur coat and white tie, but five gentlemen minus the fur coat and also minus even a tie as well. To make the thing complete, they had not so much as a collar amongst them. To put it plainly, they were loafers of the worst type. Save that they appeared to be clean, there was nothing to be said in their favour. The leader of the little band swept the great glittering hall comprehensively with his resolver.

"Better not move, any of you," he commanded crisply. "Mr. Nobby, will you kindly remove the telephone receiver I see on the bracket yonder, and nip the wires? Now, my good men, listen to me. Pampered menials, lend me your ears. We are here to-night to dine with his Grace. The fact that he does not expect us adds piquancy to the situation. The anticipated guests are not coming, so that there is not likely in be any coldness between our noble host's fellow-diners. So far as I can ascertain, there are only two exits from the house, and the first one of you who opens the door is pretty certain to collect something in the shape of a bullet. Nobody is likely to call at this time of night, and nobody is likely to go out. You won't find it healthy to make the attempt. Now, which of your noble army of the unemployed is nearest in contact to the Duke? Whose fatiguing duty is it to take messages to your noble master?"

The chamberlain relaxed his hold on the Praxiteles and swallowed something. The ringleader of the little band smiled. His clothes were shabby to the last degree, his boots were in holes, he had a muffler round his neck in lieu of a collar; and that in itself would suffice to make the Apollo Belvedere look like a blackgard. Yet his face was clean, his eye clear, and he had that indefinite something about him that suggested power.

"Very well," he said. "Go and tell the Duke what has happened. Assure him that five men are here, prepared to do fall justice to his hospitality. Pâté de foie gras, quails on toast, ortolans à la Grosvenor Square, ham and cheese and onions—anything. Fetch your master."

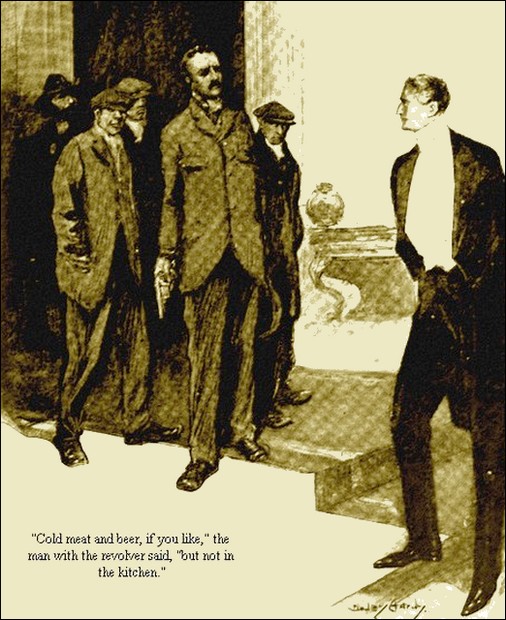

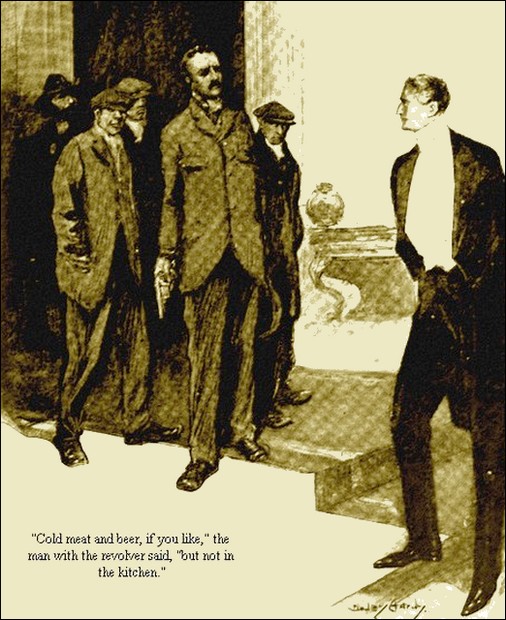

The chamberlain staggered towards the grand marble staircase as if he were picking his way over the fragments of a broken and crumbling universe. He came back presently, followed by a tall, spare man, with a brown, hatchet face and a square, clean-shaven jaw. The firm mouth suggested humour, as, indeed, did the grey rather sunken eyes. The man with the revolver nodded approvingly. Here was something like an athlete, somebody not likely to stand any nonsense. The Duke did not appear to be in the least angry; there was nothing of the outraged patrician in his flashing eyes. On the contrary, a grim smile played about his lips.

"You have come to the wrong door," he said. "Wilkinson, take those good fellows into the kitchen and give them some cold meat and beer."

"Cold meat and beer, if you like," the man with the revolver said, "but not in the kitchen."

"No? Really, there is no satisfying you people nowadays—the influence of an incendiary and revolutionary press. You will want to be coming into the dining-room next."

"We are going into the dining-room," the leader said crisply. "In fact, we came on purpose. The little scheme occurred to us a day or two ago. We were reading The Daily Post in the library of the particular Rowton House* that we honour with our patronage. I may say that two of us, at any rate, have seen better days, your Grace."

* Rowton Houses were a chain of hostels built in London, England, by the Victorian philanthropist Lord Rowton to provide decent accommodation for working men in place of the squalid lodging houses of the time. Wikipedia

"I gather that from your accent," the Duke said. "Pray proceed"

"The other three have seen—well, worse. There was a paragraph in The Daily Post to the effect that, as usual,you were dining a select party of bosom friends to-night, on the occasion of your birthday. The names of your guests were given. I was asked if I had ever dined with a duke before. I replied, with truth, that I had. A polite query to les autres elicited the response, with truth, that they hadn't. Two of them added that they'd (luridly) like to. On the spur of the moment I promised them that they should. The outlay of a few coppers—my last—at a public telephone call office, some hour or so ago, cleared the way so far as your expected guests were concerned, and the rest was easy. We may be shabby, but we are clean. Two of my friends, in their keen anxiety not to do violence to your feelings, have gone so far as to have a bath. With the rest of us that kind of thing is still a habit. To be candid, we have eaten practically nothing for the last day or so. We have no desire to disturb the peace, but after taking all this risk—"

"Pray say no more," the Duke interrupted politely. "I am delighted to meet you. To tell the truth, I was feeling nervous about General Sir Thomas Brabazon and the prawn curry. It is borne in on me that you are not likely to be hypercritical. Gentlemen, I am delighted to meet you. Kindly follow me to the drawing-room. Wilkinson, let dinner be served as soon as possible. And you need not be afraid of awkward consequences. If you will withdraw your outposts, Mr.—er—"

"Jones," the man now without the revolver said. "Your Grace's implied assurance is sufficient. Nobby, step outside and call off the militia. Say their faithful services will he rewarded—well."

"Now," the Duke said, "Wilkinson, 're Mr.—er—Nobby half a sovereign, then show Mr. Nobby upstairs. What have I done to earn this priceless privilege? This way, gentlemen."

The man called Jones led the way. Now that all danger was past, he was feeling a little uneasy. He would have been annoyed had anybody told him that he was a trifle ashamed of himself. He had not expected the Duke to behave quite like this. There was no longer anything to fight for, no grim pleasure in watching his host's annoyance. He strolled along quite casually, forgetful of his attire and inclined to revert to the past. The big picture over the doorway was a Velasquez; he had never seen a finer pair of Corots than those over the Louis Seize commode. And surely that was the Millet? Where had he last seen it? Was it at Chateau D'Algon that shooting season, when—? But what was the use of thinking of that sort of thing?

It was much more amusing to watch Nobby, also the man called Ginger. They sat down on the edge of a couple of brocade and gilt Empire chairs and breathed heavily. All the fight had gone out of them for the moment. They were torpid in the presence of so much splendour. One other man, in a greasy frock-coat and ragged trousers, was critically studying a cabinet of famille verte china. The "Captain," as he was called, had an eye for form. The big doors were thrown back, and dinner was announced with a solemnity befitting the occasion. Nobby eyed a pair of resplendent footmen truculently.

"One sniff," he said, "and you gets it in the jaw! Savvy?"

No sniff broke the solemn silence. Here was a small room, cedar-panelled, in the centre a round table resplendent with glass and silver and flowers. In the velvety semi-darkness measures of silver and gold flashed their glowing facets from the sideboard. Nobby gave a little sigh. Like Blucher, he was feeling that here was a splendid city to sack. He sat on the edge of a chair, confronted and sustained by the near proximity of Ginger. What were all those bloomin' knives and forks for? What did any man want with more than one of each. The little cluster of glasses looked more promising. but some of them were distressingly small. A large pewter pot might have been the harbinger of better things. Nobby helped himself liberally to hors d'oeuvres. An indiscriminate mixture of anchovies and olives came as a shock to his unsophisticated palate. Still, not so bad.

"Champagne, sir?" asked as small and oily voice in his ear.

"If you must 'ave one on the jaw—" Nobby begun. "Champagne? Yes. Fill up all the bloomin' glasses so's to save time, and come back again when I rings the bell! Histers? I don't think!"

Oysters! Oh, reminiscences of Southend in purple patches, sunny glimpses of Margate, but never such oysters as those before. But why only six? And what was that stuff smothered in white sauce? At the suggestion from Ginger that it might be onion sauce, Nobby's eyes glistened.

"Tastes more like cheese, don't it, mate?" Ginger asked. "Fish o' some sort. And spinach. How'd I know it's spinach? Didn't I 'ave a coster's barrow once? Say, this champagne does me a treat! Well, what you got there? Roast pears? Not taking any. Snipe? What yer gettin' at?"

"They don't smell 'alf bad, Ginger," Nobby said. "'Ere, give me a 'andful. Prime!"

There are bones in snipe even when they are cunningly braised and sent up in a thick gravy, the base of which is old Madeira; but Nobby did not seem to be aware of the fact. A dreamy sense of happiness was stealing over him. He demanded, somewhat curtly, a second helping of the most delicious beef he had ever tasted. He informed the Duke amicably that it was impossible to get beef with such fat nowadays. It was not for the Duke to remark that Nobby was commenting favourably on a fine haunch of venison from his place in Yorkshire. Nobby was not particularly interested in the fruit, and the fount of champagne had suddenly dried up. In one of the tiny glasses by his elbow a footman had poured out a glass of amber fluid. Nobby took it at a gulp.

"If that's whisky," ho said, "why, it cops the bakery! Take some more? Why, yes, and give it me in one of those tumblers. If that don't make you feel good inside, Ginger— Shartons, is it? Try it, cully —try it, my lad!"

Ginger winked approvingly. He found himself presently behind a large cigar which, in his humble judgment, would have been better for the addition of a gold-lettered band. Very possibly the pampered menials had removed the band. There was coffee presently, but Nobby found it hard to recognise. There was some subtle difference between the black fluid in the thin cup and the turgid beverage of the stalls. Nobby watched his host dexterously tilt a small liqueur glass of old brandy into his cup. Common politeness called for a following of the suits. Nobby grabbed for the decanter and filled up his cup. He smacked his lips approvingly.

"These dukes know a bit," he whispered. "I do feel good, mate! If you brought me a church now on a hand-barrow, I wouldn't rob it! Tell me I was going to he hung to-morrow, and I wouldn't care!"

"Shall we adjourn to the drawing-room," the Duke asked, "or sit and chat here?"

Ginger propounded a conundrum.

"What do you think?" he asked with emphasis.

"We will look upon the proposal as carried," the Duke laughed. "Mr. Nobby, I trust that you have had a good dinner? You are enjoying yourself?"

"I'd like to take on the job regular," Nobby responded—"six days and Sunday! Mr. Jones, 'ere's to you good 'ealth. Reminds me of at story I read the other day—"

"I'd rather hear your own story," the Duke said. "Come, gentlemen, you owe me something. Tell me your own story. Mr. Nobby, if you please."

Nobby permitted himself to smile. He was feeling at peace with all mankind. His somewhat crude platform in the matter of dukes had shifted slightly. His views on the subject had been largely gathered from flamboyant posters at election time. Dukes were usually thin, elderly men with long, lean faces, and given to the rakish wearing of coronets with morning dress. Apparently there was another brand of duke altogether, and Nobby had struck him. Come to think of it, the Duke had good cause for annoyance. The whole thing was what Nobby would have called "a bit thick." Yet he had played the game like a man... And what a dinner!... That yellow stuff in the little glasses was fine. Nobby had had quite enough, and he was not blind to the fact. But somehow the Duke's liquor seemed to touch another spot. Nobby did not feel in the least quarrelsome, not at all disposed to defy the police and rage against the statutes. On the contrary, he was thinking of his boyhood days, of primroses and patches of sunlight in the woods, and his first rabbit —of illicit hares and partridges.

"Beg pardon!" he stammered. "Your Lordship's Grace asked me a question. If you takes me for a bloomin' Cockney, you're a—you're mistook. Bred and born in the country, I was—Wiltshire way. Always fond of it... birds' eggs, to begin with, then beating in the winter when Sir George had his big shoots. Mind you, I didn't care a 'ang for the stuff. Give the birds and rabbits away as soon as look at you. It's the sport as I liked. Regular gets into your blood, it does. If you say as a working chap ain't as fond of a hit of sport as a gentleman, then I say you're a—well, you're wrong. Anyway, there was precious few of them as could touch me at the game. And Sir George offered to make me a keeper, 'e did. But not me.

"Dare say it would have come out all right in the hend if it hadn't been for—Annie. I call her Annie, but that wasn't her proper name. And it was a toss up between me and Jim Baynham, the second keeper... When the big row came, and Baynham got his head laid open, they swore it on to me. I never touched him—never. I wasn't the sort of chap I am—I mean I was. But Baynham swore as it was the butt of my gun, and I got seven years. Of course, he knowed as I never touched 'im, and he knowed who did. But I got my seven years, and he got Annie. After you get seven years, you don't have much chance with the police. And that's all about it, your Dukeship. And that's why I see red when I gets into liquor. Pass the decanter, can't you?"

"Much the same as Nobby," Ginger burst out. He jerked his words like a school-boy repeating a lesson. "'Osses is my case, and my choice, too. Wanted to get rich too quick. Did the trick at Newmarket once too often, and got before the stewards. My owner he go off all right,and so did the bookmaker I was working for. Everything put on to Little Willie, of course. I suppose must have been worth a matter of ten thousand pounds at one time. How did it go? Don't ask me. 'A1f of it was swallowed up defendin' a case where me and some pals was charged with nobblin' a favourite for the Liverpool Cup. Did we get off? We did. Was we lucky? We was. Anyway, I'm selling race-cards to-day and gettin' a living—somehow. That's all."

Ginger helped himself defiantly to brandy. He wondered in a vague way why he had told this story. He had never mentioned it before to a soul amongst his associates. But then he knew nothing of the generous influence of good wine, though in a dim fashion he approved of his surroundings.

"And the gentleman on your left?" the Duke suggested.

The individual in question turned with a start. With his face on his hands, he was demurely contemplating the artistic confusion of the dinner-table. How well those peaches looked, with the tender flush of pink on them, against the flash of silver and the feathery droop of fern! He raised a long, lean face and regarded the Duke steadily.

"There is something in the atmosphere of this room that invites confidence," he said. He spoke with the manner and accent of one who new his world and understood it. "It is a great pleasure to me to sit down to a dinner like this once more. It is probably for the last time, but no matter. Would your Grace credit the fact that eight years ago I had a good practice in Harley Street?"

The Duke bowed. The look on the thin, intellectual face, with its clever, cynical mouth and the eyes with a certain sombre horror in them, appealed to him. Men show the signs of dissipation in many ways, as the Duke knew. He nodded with a smile of sympathy.

"I am quite prepared to believe you," he said.

"I am obliged to your Grace. I made my own way in the world. I took an open scholarship at Oxford from an obscure country grammar school. I did well there. It was a very hard struggle, and I was never robust. I got to Harley Street at length and married. You can't do any real good in Harley Street unless you are married. I am not going to blame her, but I married the wrong wife. I ought to have checked her extravagances at the beginning. I didn't. The struggle was worse than ever, and I wanted a holiday. Heavens, how I wanted that holiday! There were times when I was on the verge of absolute collapse. I had to stimulate myself. At first it was wine. But that didn't do. For a doctor in Harley Street that kind of thing is fatal. So, just to bridge over the gulf, I took the first dose of morphia. That year I made eight thousand pounds. That year I perform two operations that brought me in touch with the world, and at the end of that year I was taking five grains of morphia a day. It was the next year that I made that blunder over Lady— I mean I gave a wrong prescription. Then there was another operation followed by an inquest. It was in all the pagers, and I took all the blame. The morphia bottle was found in the bedroom, and I had to admit that it was mine. A year later and my place in Harley Street was sold under a distress for rent. Another few months, and I might—for, yes, sir, I had cured myself. I do a little writing for the medical papers. I dare say, if I put my pride in my pockets and went to some of my old colleagues—"

"I'm sorry," the Duke interrupted. "Pray don't say any more. If you will send me a card with your name and address on, I might—er—possibly—you understand. This has been a remarkable evening, gentlemen. Believe me, the pleasure has not been entirely on one side. Now, Mr. Jones, we should like to hear something from you, if you please. Seeing that you are, so to speak, the founder of the feast, it is only fair that you should contribute something to the harmony of the evening. I think that is the phrase they use at these unconventional gatherings. Silence, gentlemen, for Mr. Jones! Our popular colleague will now oblige."

Jones looked up almost with an air of defiance. For the moment he had almost forgotten. He had heard little or nothing of what was going on about him. He had forgotten his shabby, seedy clothes, the life that he had been leading; he was back in the past, and the surroundings were congenial.

"I gather that you have been telling stories," he said. "I listened and yet I did not hear. Adversity makes us acquainted with strange bed-fellows. If you look around you, I shall not he accused of any narrow or uncatholic taste in the selection of my companions. Like the doctor, I have seen better days, Curious that we should have nick-named him 'The Doctor' without knowing anything of his history."

"And you are 'The Captain,' though we know nothing of you," the last narrator intimated.

"I am," Jones went on. "I had forgotten that. As Mark Twain says, I was born of parents neither particularly poor nor conspicuously honest. Well, they were not poor, at any rate. They were in a position to send me into the Army, and keep me well supplied with money. But the Army, after a time, got too monotonous for me, and I went to Australia. I got a commission in the police there, and for four years I had the time of my life. Then I married. It's only four years ago. Just to think that so much can happen in so short a time! I'm speaking about the gold rush at Marrawatta, and the lawless scenes that followed. I dropped out of the force at that period, for I had done well, and my intention was to take up a station. If I'd lost money then and there——but I didn't. There was as chap I knew quite well, who was called the first mate, because he had something to do with a trading steamer. Well, he found gold, and a lot of it, and so did I. Unfortunately, perhaps, I kept my secret. The first mate boasted of his luck. And then he disappeared, and two months later his skeleton was found picked clean by the crows, and— well, they said I had murdered him for his money. They got to hear of my money, and by the skin of my teeth I escaped lynching. I got away without a rag to my back or a penny to my name. For years they hunted for me, until they discovered that I was drowned in the Parrawa river."

"The Parrawana river, isn't it?" the Duke asked.

"Perhaps. Come to think of it, you're right. I had to change my name and identity. I got back home, and nobody recognised me. I have no name, no friends, and no way of getting a living. I've done my best, but it's quite useless. The fear of arrest has never gone from me. My wife is in a situation in London, and I see her sometimes. Ah, what a pal that woman has been to me! But for her, I should have put 'Paid' to the account long ago. And if anybody had told me this morning that I should be talking like this before a lot of strangers—I suppose it's the old association, the dinner and the wines. If you ask me—"

"I do," the Duke said. "What was the first mate like? A man with beard and moustache and hair all over his face? Would you recognise him if he was clean-shaven? Didn't he have a peculiar toast when you drank with him? Didn't he cock his finger like this? Steady, my dear fellow—you have knocked your glass over!"

The man called Jones had risen to his feet, and stood regarding his host with dilated eyes. The Duke rose in his turn and glanced at his watch.

"Gentlemen, it is getting late," he said. "I shall hope to see you all again some day. Doctor, don't forget what I asked you. Messrs. Ginger and Nobby, we shall meet before long, when I may have something to your advantage. Mr. Jones, I'd like a ward with you when the others here gone."

They filed out presently, leaving the Duke and Jones alone.

"Is—is it possible?" the latter stammered.

"My dear Jocelyn," the Duke replied, "nothing is impossible. The first time I saw my face in the glass after I shaved, l did not know myself. Neither did anybody else. I didn't want them to. I never expected my present position. I should never have got it if the Majestic Queen had not gone down with five male relatives of mine aboard. I got the news by accident, and I left the old camp without telling a soul. With a clean-shaven face I walked through the camp, and nobody knew me I wanted to leave the old life behind. Till this moment I never guessed that there might he inquiries made. And you have suffered all this for my sake! And you were the best pal I had! Oh, I'll put it all right! I'll let them know that the first mate is still alive—

"Dick, where is your wife? What is she doing? In rooms of her own, working late typewriting? Let's go round there now. I won't sleep till I've had her forgiveness for all the trouble my silly conduct has caused her. Take my cheque-book and fill it in for what you want for the present. Only let us go and see your wife now."

Jocelyn swallowed something hard in the back of his throat.

"A|l right," he said—" only let me go first, Bill. You won't mind waiting half an hour outside in the cab?"