THE thing savoured of mystery and possible adventure, and Drenton Denn, Special Commissioner, was ready for the fray. Anything was better than loafing in the forest behind Shaz waiting for the transports that never seemed to come, in company with Glasgow, who was engaged in the up-country trade and had just returned from one of his adventurous expeditions.

"Here is the back door of Central Africa," remarked Glasgow. "There is no occasion to knock. Will you come in?"

"Got anything fresh on show?" Denn asked.

Glasgow smiled. Not in vain had he taken his life between his teeth for the last five years. The brawny Scot was burned a deep copper bronze; his beard was ragged as a goat's.

"I can promise you the sight of a thing or two you have never seen in your life before," he said. "And this is about the last trip I shall make through the great forest of Ulu. It has been dangerous work, but I have done pretty well. What do you think of this?"

From a cowhide bale amongst his stores Glasgow produced a feather. It was a magnificent white plume, some two feet in length and of the most perfect texture. It was soft, almost elusive, to the touch, and as Glasgow shook it out the thing gleamed like a gossamer spray of falling water.

From a cowhide bale Glasgow produced a feather.

Denn was loud in his admiration.

"My word," he cried, "the finest ostrich tail in the world is a mere scrubbing- brush compared with this. Got any more?"

"Got ten thousand of them in that bale. Oh, you can laugh. Though that feather when shaken out covers a small table-cloth, you can put half-a-dozen of them in your waistcoat pocket easily. See."

The exquisitely beautiful plume was rolled up into a ball no larger than a marble. When shaken out the shimmering gloss and dainty loveliness of its down were absolutely unimpaired.

"Takes eight of them to weigh an ounce," Glasgow went on. "Nothing injures it. I calculate these things will make a sensation in England."

"You can pile up the stamps on that," Denn replied. "I'd give a trifle to see the bird that feather came from."

"Man, that feather came from no bird at all. What kind of creature it belongs to I know no more than the dead. The Ulu natives are on the best of terms with me now; they bring me these feathers, but whence they come I can get no information. My man Chan will do anything for me, but one question touching feathers sends him muttering an incantation to some Obi god and reduces him to sulky silence for the day."

Denn sat up briskly, despite the heat that beat down in waves.

"Bully for you," he said. "I'll come to Ulu with you and I'll see that bird, or whatever it is. This is going to be an adventure after my own heart."

Glasgow was quite agreeable. He little realized the peril and danger his volatile companion was breeding for him, otherwise the cautious Scot would have traversed the forest alone.

"Have you never tried to see the bird?" Denn asked.

"Not I," Glasgow replied. "I came out here for money, and I have made it by leaving the natives alone. There are queer things, evil things, out yonder, and there are bones of white men bleaching in the sun who have sought to know too much. Curiosity doesn't pay yonder."

They started at dawn the next morning, leaving the camp in charge of two trusty natives, and taking Chan, Glasgow's faithful servant, with them. The latter was a fine specimen of his class, yellow of skin and lithe of limb, with hair straight and black as ebony.

It was cooler in the forest, but the track was narrow, and there were many snakes about. Denn could hear them writhing and wriggling in the dry scrub, and caught the sullen flash of scales from time to time. He had no regret for his leather gaiters.

"That chap of yours will get into trouble in a moment," he muttered to Glasgow. "Seems like asking Providence to tread on the tail of one's coat to come through a snake-infested jungle like this with nothing on but a loin-cloth. Hanged if that isn't a cobra."

It was. The wicked head was raised, the hood uplifted to strike at Chan as he strode carelessly on at the head of the procession. Denn felt the hair pricking and bristling on the back of his scalp.

"Look out, you fool!" he yelled. "Don't you know a cobra when you see it?"

Chan turned with a sweet yet pitiful smile. As he did so the cobra struck, and Chan caught him coolly by the throat. The next instant the slimy back was broken and the limp body cast aside.

The cobra struck.

"Well, I'm dashed!" Denn exclaimed. "But the brute struck you."

The statement was correct. There were two red punctures in the thick of Chan's thigh. Already the limb was commencing to swell. Half an hour at the most and Chan would cease to be. Denn's face was expressive of sickening horror. Glasgow smiled, and Chan showed two glistening rows of teeth in the grin of the man who courts approval successfully.

"No make fuss," he said; "me all lite in minit gone by."

From his loin-cloth he took a tiny brown substance about the shape and hue of a dried bean. This he wetted with his tongue, and proceeded to rub the bean more or less carelessly on the punctures, after which he resumed his onward march with absolute easiness.

"Some fetich, of course," Denn muttered. "But nothing can save him."

Denn resigned himself to melancholy and the development of the tragedy. But, in his own vigorous metaphor, the tragedy didn't develop worth a cent. The hours went on and the camp was fixed for the night, and, like the monks and the friars at Rheims, Chan did not seem one penny the worse. Denn watched Chan with a glassy eye. Pipes once lighted and the native moved out of earshot, Denn began to speak.

"It seems to me you have missed a pretty short cut to fortune," he said. "Chan's got an infallible cure for snake- bites. If you could get hold of the recipe, you could afford to give those feathers away."

"If I could get hold of it. But I can't. All the Ulu natives carry one of those little brown beans; in fact, I have one myself. Chan gave it to me, and he took his life in his hands in so doing, let me tell you. The thing is mixed up in a way with the feathers, and some religious ceremony with a little tin god of sorts tacked on to the end of it. It's a kind of freemasonry. I'd give all I possess to obtain that recipe, but I know when I am well off, and so keep my fingers out of that pie. If you take my advice you will keep this discovery to yourself."

Denn fell back on a policy of silence. As a matter of fact he had not come all this way to see and be dumb. The New York Post did not pay him the salary of an ambassador for that. Besides, it was a distinct duty to humanity to obtain that recipe.

A six-bladed knife and a promise of an apocryphal revolver later on shook Chan's dense religious fanaticism to the marrow. Denn was fishing for secrets it was peril to the soul to reveal, and Chan was troubled. Still, Heaven was far off as yet, and the revolver was so near.

"No dare tell," said Chan. "God Gnew make the juice that keep the snake fangs out. God Gnew have the papyrus in um belly and the priests guard it in the temple at Ulu. Every full moon they make more juice in the temple, then um put papyrus back in Gnew belly again."

"Let me have a squint at that show and you shall have a silver watch, Chan."

Chan shivered and his lips grew grey. His bony knees clattered together and his mouth watered.

"Say that again and me kill you," he said, hoarsely. "Big fool white man; he not know what he talk about palaver so."

And Chan flatly refused to say any more. Still, he was clearly shaken to the pith of his soul, and many a longing glance did he cast at the chain Denn had displayed across his canvas shirt. That the poison was getting in its work the astute Yankee knew well. He had quite made up his mind to see that ceremony. Secret rites, freemasonry, and papyrus in the internal economy of a god called Gnew! The smartest "special" on earth was not to be baffled by a fanatical native with no clothes on. Denn said no more till over in the valley towards night on the third day the huts and stockades of Ulu rose in sight.

Denn stood up alongside Chan.

"What about that watch?" he whispered.

Chan's teeth clicked and his lips quivered with a sort of nervous paralysis. His eyes gleamed as a cat's might in the dark. Then he fell to sobbing, and the big tears rolled down his cheeks. It was not a pretty spectacle, and Denn was not without a sense of shame.

"So it's to be," he said. "The question is, when?"

Chan's lips framed rather than said, "Tomorrow afternoon."

GLASGOW lay in the hut assigned to him with the air of a man who mourns for wasted hours and yet bears the loss of them philosophically.

"No business done to-day," he said. "They've got one of their bobberies on, some fool nonsense or other at the temple which takes place once a month. They're quiet and peaceful chaps as a rule, but when the periodical madness comes on they are apt to be dangerous. It is only by lying low and not evincing the slightest curiosity that I have got on with the Ulus so well."

"I should have pulled all the inside of the business out by this time," said Denn.

"Yes, and by this time you wouldn't have any inside to pull out," Glasgow replied, drily. "I'm going to have a siesta."

A minute later and Glasgow was asleep. Denn crept quietly out of the hut and made his way to the spot where he had arranged to meet Chan. Not a single Ulu was in sight anywhere.

Chan was looking downcast and troubled, with a furious gleam in his eyes that caused Denn to slap his hip-pocket significantly.

"None of your confounded nonsense," he said. "This is a case of no song, no supper. The question is, how are you going to disguise me so that I can watch the circus procession without any chance of being fired out of the show?

"You go as pilgrim," Chan explained, sullenly. "Pilgrim come from beyond Shaz to the shrine of Gnew. Holy things for pilgrims to do like Mahomet fellows down Cairo way say of what call Mecca."

"That's all right. But I don't look like a pilgrim to any considerable extent. What are you going to do with my face?"

Chan proceeded to unfold a long robe made of coloured grasses fashioned like a sack. This he placed over Denn's head, leaving him with two holes wherewith to see. A pair of moccasins of the same material completed his outfit.

"There pilgrim's dress for you," Chan remarked. "Taken from a dead pilgrim, un had cholera. No other one get. Perhaps you die cholera too."

Denn shuddered slightly. A natural desire to tear the flimsy structure in fragments came over him.

"There is a drawback to every pleasure," he said, grimly. "What time do the doors open?"

With a swift critical glance at his companion, Chan pointed the way. Up to the present a strange silence had been observed, and no single Ulu could be seen. Then a queer, grotesque figure came forth into the main street of the village and commenced to blow vigorously on a horn.

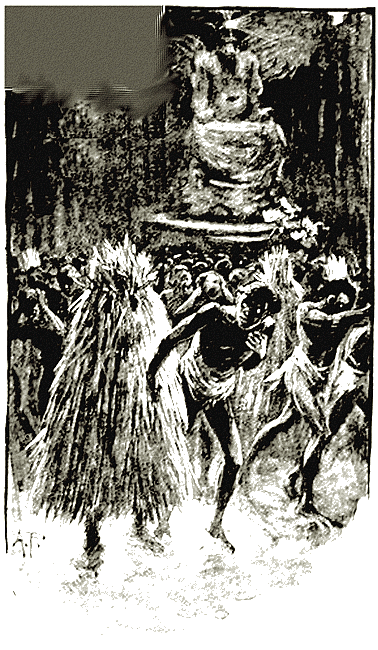

From the huts, up from the grass, out of the shelter of the forest, men and women seemed to rise as from the dead. The fierce mob, uttering yells and cries, pushed forward. Their gleaming eyes and set faces were eloquent of the frenzy of fanaticism that possessed them.

An ugly crowd—no mistake about that; a crowd drunk with religious fervour, which is a dangerous thing to the scoffer even in civilized climes. No reason to warn Denn that he would be torn limb from limb on the slightest suggestion of his presence.

It was therefore some comfort to him that there were hundreds of pilgrims besides himself. He and Chan were soon in the thick of the stream, and a greasy, evil-smelling stream it proved to be. As the crowd surged along the cries and yells ceased and a strange, strained silence followed. They were eager and yet strangely reluctant, as a man who is compelled to witness an execution. Fear and curiosity were mingled. Denn could hear his companions breathing heavily, like runners who have come far and fast.

Presently the procession arrived at a huge mass of rocks that thrust themselves out from the hillside. Carried on by the living stream, Denn found himself hustled down a flinty gorge and thence through a pair of massive bronze gates, beautifully modelled and finished.

"Well, this beats everything," he muttered. "Now, where on earth do those magnificent gates come from? Nothing finer was ever cast in Greece or Rome. It seems to me I'm going to have value for my money."

The gates closed right up to the rugged arch of the roof. Inside was a huge natural temple, faintly illuminated by a dozen or more windows cut through the living granite. And each one of the windows u as filled with the most delicate bronze tracery.

The place was so vast that there was room and to spare. Denn found a gloomy corner, where he stood with Chan by his side so that he could observe everything without being seen. No previous adventure had been more fascinating than the present one.

Denn's keen eyes took everything in. One surprise tripped over the heels of another so fast that the American grew quite accustomed to the whirl of sensations. He looked down from the roof to the floor at his feet. He saw that he stood ankle-deep in some white feathery substance that glistened purely in the filtered light.

The whole temple was carpeted with the marvellous feather that Glasgow had shown him a day or two before. There were literally hundreds of them, the pilgrims and Ulus trampling them under foot as if they had been grass. As Denn bent for closer inspection Chan grasped his arm.

"Nothing touch; dead certain fool white man," he whispered.

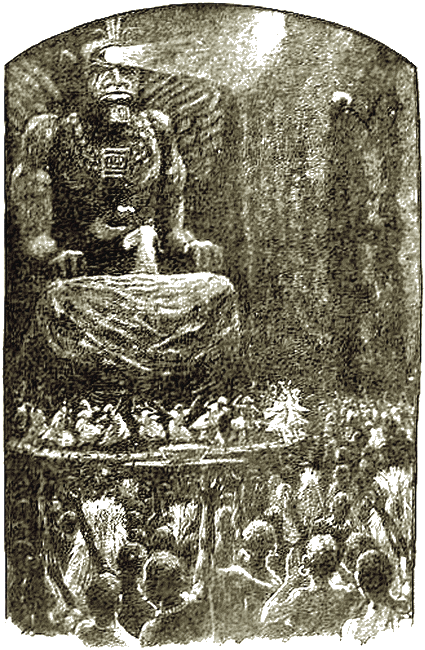

Denn accepted the hint. And, indeed, there was something else to occupy his attention beyond the beautiful feathers. At the back of the temple there stood a gigantic idol of unusually repulsive aspect. In the centre of the forehead was one gigantic eye behind which a lamp had been lighted. The whole thing was grotesque to the last degree.

At the feet of the idol on a platform a mass of priests, or medicine-men, had gathered. They were old and withered, every one of them, and clad from head to foot in some coarse white cloth. On a table at the foot of the idol Denn could see a wicker basket containing a dozen or more cobras in a state of lively indignation.

Then the priests began to sing, grouped in a semi-circle. At first their chant was low and wailing and monotonous, and to Denn's great surprise he recognised it as familiar and Gregorian. A dreamy sensation of having been there and having done it all before came over him.

"Nothing new under the sun," he muttered. "White men must have been here before. Otherwise, how on earth did those gates get here?"

Presently the chant grew louder and more fierce. Up and up it rose until there was one screaming cry of passion and supplication, till finally the rocking, reeling priests prostrated themselves before the altar.

Instantly the whole assemblage did the same. Denn felt himself dragged down by Chan's powerful hand. After the fearful din the silence was strange and almost painful. And yet Denn had never seen anything more thrilling and impressive before.

Denn lay half smothered in those luscious clinging feathers, soft as down and diaphanous as sea-foam, wondering what was going to happen next. He had some dim conception. of the way in which the ceremony pointed. This music was doubtless an incantation and an appeal for mercy from the god. They were waiting before they had courage to proceed.

A quarter of an hour passed, and then the leader of the priests raised his head cautiously. Another and another, till at length they were all on their feet once more. Loud yells of triumph followed.

Slowly, by reason of the weight of his years, the chief priest proceeded to climb up the frame of the great idol. He looked like a white fly on the head of a Sphinx. The action was nothing in itself, apart from the feebleness of the chief performer, and yet it was followed by almost painful silence. Then the arm of the priest was plunged up to the elbow in an orifice in the idol, to emerge a moment later waving a faded strip of parchment.

The arm of the priest was plunged in an orifice in the idol.

Instantly the throbbing silence was broken by a manifestation of mad delight. The pilgrims tossed, and rocked, and yelled in a species of intoxicated delirium. Denn knew enough to grasp the meaning of this. The parchment was doubtless the sacred papyrus containing the recipe for the snake cure. Probably these poor folk always gathered there under the impression that some day the great god might destroy the papyrus in a fit of rage.

However, here it was, passed from one priest to another and perused eagerly. Then fires were lighted on the platform, and upon them gourds were placed, and filled with some liquid that caused a great and acrid smoke to rise. Whilst the gourds were boiling and bubbling the priests danced around them with a solemn, stilted step that tried Denn's gravity to the utmost. The absolute wooden stolidity of those around him did not tend to seriousness on the part of the volatile American.

Presently the dance ceased and no further smoke arose from the gourds. The contents of the whole of them were poured into a large brass vessel to which water was added. A big reddish lump like putty was extracted from the brass pot and handed from priest to priest for inspection.

A great burst of triumph followed. The religious function had been eminently successful. Denn felt that the end had come. Then, as he looked about him, he became conscious of the fact that night was coming on. A minute later and it shot down like a blanket on the place.

As if in a paroxysm of fear the whole of the audience made a rush for the gates. Chan plucked at Denn's sleeve.

The whole of the audience made a rush for the gates.

"Come!" he whispered, hoarsely. "The white dumb devil! Quick!"

Denn eluded the grasp. If there was anything more to be seen he made up his mind to see it. He drew back into a dark corner so that the stream of frantic, perspiring humanity might pass him by and leave him high above the flood.

The flood went roaring on. Denn, by the feeble light in the eye of the idol, watched the stream ebb away. He saw the papyrus restored to the body of the god, and the stuff the priests had made carried away. And he also saw as the pilgrims hurried out that every eye was turned upwards with shuddering fear.

"Something gone wrong with the works," Denn said, sotto voce, "or why should they clear out like that with the darkness? Doubtless the ceremony took more time than usual. If I do happen to come across the white dumb devil I shall have had a pleasant afternoon."

By this time the place was absolutely quiet. Denn felt no uneasiness. Chan, of course, would imagine that he had been swept out with the crowd. Even when Denn discovered that the great bronze gates were fast and that he was a prisoner he felt no fear.

If the worst came to the worst he could remain there for the night and trust to luck to slip out when the temple was open in the morning. That nobody would molest him till dawn he felt certain, for the fear of the darkness had been on priest and layman alike.

Therefore Denn felt at leisure to explore about him as he pleased. It did not take him long to discover that behind the great idol was a huge cavern going right away into the hillside. So far as he could see the whole floor was carpeted with those peerless white feathers. They had been trodden under many a score of grimy feet, and yet they were still as light as thistledown and seemed to shake off corruption as water runs off a rose.

"I never saw anything more exquisitely lovely," said Denn. "I would give a trifle to see the creature they came from. Now, I wonder if this bird or beast lives in the cavern behind me? It looks like it."

It did indeed, for high above Denn's head, where no human being could possibly go, one of the feathers hung on a jagged ledge of rock.

"Extraordinary thing," Denn went on. "It must be a bird, unless there is such a thing as a flying beast. Upon my word, it begins to look like it. If the creature is here I shall most assuredly drop a card on him."

The idol still glared down at Denn. The idea of taking possession of the papyrus instantly possessed him. It might be useless; on the contrary, it might be in a formula known to science. There was just the chance.

As Denn started forward to carry out his intention something seemed to glide by him and brush his cheek softly, gently, as the touch of a mother's hand. And yet the rush of air that followed was as a strong breeze. In the feeble light of the gleaming eye high overhead something darted like a swallow in the twilight. It was vague, ghostly, yet tangible.

Denn forgot all about the papyrus. A treasure was there beyond rubies, but it slipped from the American's mind. The great white shadow swooped down and stood still in the air quivering before Denn's astonished eyes.

What was it? Something greater than an albatross, more massive in the body and wider across the wings, which vibrated so swiftly that their motion was impossible for the eye to follow. Not a bird or a beast, but a great white moth with an eye soft and mournful, and yet so vaguely terrible that Denn stood paralyzed before it.

This, then, was the dumb white devil that Chan had spoken of. But surely the thing was harmless. The soft, mournful eye, the noiseless, snowy wings, pointed to a gentle, timid thing. Yet as it quivered closer and closer to Denn he backed away. He had heard before of a huge moth unseen by any white man's eye, and here it was.

He backed farther and farther away. The thing followed in the same terribly noiseless manner as if it were floating on the air. Denn could see into the soft, mournful grey eye, he could catch a faint perfume like musk, and with a flash the wings were about him.

There was no pressure, no cruel claws cut into the flesh, no serried teeth met in the flesh of the affrighted man. A certain weight bore him to the ground, and then his eyes and throat and ears seemed to be filled with something that seemed like warm snow, exquisite and glowing to the touch and yet soft as satin.

A certain weight bore him to the ground.

Denn fought it off as best he might. As a matter of fact, he knew quite well that he was being suffocated to death in a mass of feathers. Try as he would he could find no way out of the white sea surrounding him. He gripped for the body, but only succeeded in burying his arm to the shoulders in the tangle of silken plumes. He could hear a heart beating under it all. Still, it was no time for speculation. A little longer of this and Denn's interest in mundane matters would be finished.

He fought and gasped and struggled for breath. His heart was hammering painfully against his ribs, a cold sweat broke out over him. He began to feel himself floating away on a boundless sea towards oblivion. The strong man was growing weak as a little child.

Then, without warning, the white, fluttering mass lifted. Denn, dazed and confused, lay on his back, looking upwards. He saw the cause of this diversion. High over his head he could see, not one of the great moths, but two of them. They were darting round one another in dazzling flashes faster than a swallow cleaves the air, and yet without the slightest noise. Denn crept away to the shadow and made his way on all fours to the gates.

He looked up again. As he did so he saw the two moths come with a flashing wheel and dazzling circle in full contact with each other. For an instant it seemed as if they had burst like two bombs, for a white cloud, growing wider, enveloped them. As the cloud commenced to fall it resolved itself into a shower of feathers,

The moths were fighting a duel. Great as the rain of plumes had been, there was no sign of loss of plumage in either insect. Again and again they came together with the same wheeling motion, and again and again the showers of diaphanous plumes flecked downwards. Then, as they charged once more, one of the moths avoided the other and darted with amazing swiftness into the purple gloom beyond the great idol. A fraction of a second later and the other moth had disappeared also.

Denn crouched there, gasping and panting. Idol, papyrus, the boon to mankind, everything was forgotten in the mad desire to be beyond those bronze gates. Tangible dangers Denn knew and appreciated—dangers he could grapple with and hold on to; but the silent terror of this danger frightened him. Small wonder that the Ulus had fled at the coming of the night.

Doubtless in the caverns beyond were hundreds of those ghostly moths. And they might return to the attack at any time. One was bad enough, but to be beset by a score of them—to be buried under the crushing weight of those white plumes that filled eyes and throat and ears—

Denn cast the thought shuddering from him. The thing was to get away now before danger returned. Still, that was easier said than done. There was no escape save by the great bronze gates, glittering now in the moonlight that bathed the whole place in a silver flood.

Denn looked outside as a prisoner does through his bars. As he did so a figure crept out of the long grass. To Denn's delight he saw the white, fearful, sweat- bedabbled face of Chan.

"White dumb devil not there?" he whispered.

Denn hastened to reassure the other. Chan pressed on one of the ornaments of the great gates, and they slowly yawned open far enough for Denn to step through. There was no further danger now.

"Fool white man no want any more go yonder," said Chan, recovering himself, as the temple was left behind. "Guess you stay there when others gone. White dumb devil stay in, hide in daylight, and only come out at night. Lots um in cavern yonder. You see um?"

Denn responded that he had done so. Then he fell to asking questions. Some years before, he found, the big white moths had come to this temple. More than one priest had been found mysteriously suffocated before the real truth had come to light. Then it was discovered that the big white moths only dared to come out after sundown, and there was consequently no occasion to leave the temple. After dark it was a different matter. Hence the flight of the Ulus and pilgrims at the fall of night, the ceremony having taken longer than usual.

"But where do those moths come from?" Denn asked.

Chan pointed towards the distant hills.

"Over there," he said, "in the valley of caverns. No dare go there after dark. Many mans killed there. Sen um self every times. No go there time some more not for revolver no, not for silver watch."

Denn laughed at the pointed speech. He laid upon Chan's shoulder a hand that still shook slightly.

"No occasion for the hint, my simple savage," he said. "You shall have the best watch and the best revolver that money can procure."

Chan smiled and he sighed. For he was fearful for the anger of the gods, and his soul was heavy within him.