RGL e-Book Cover 2018©.

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©.

DRENTON DENN lounged into the editorial sanctum of the New York Post, his hands plunged into the pockets of a Norfolk jacket. In one corner of his mouth he wore a green cigar, which he took no trouble to remove. The great man opposite carried a short pipe between his teeth, also he was minus coat and vest. All the same, Peregrine Pryde was a great man, and some day might be president. Meanwhile he preferred to control the destiny of perhaps the smartest paper on earth.

"Halloa, you turned up again?" he remarked.

"Cuba," Denn said, parenthetically. He slanted a dingy straw hat over his left eye. "Got at scare article or two for you. Costly work, though. That last cheque of yours for exes went no way."

"Hang the money, so long as you get the stuff" said Pryde. "I'm glad you've come back. all the same. "That your dog?"

Denn nodded and slightly beamed in the direction of a rough nomadic terrier coiled up near his chair.

"Name's Prince," he explained; "does anything but talk, in which he has the advantage of you and me. Got a job for me, eh?"

"Rather. Wants lot of pluck and daring, but danger is one of your weaknesses. You've heard of the 'Fire Bugs,' of course? No! Well, at any rate, you are aware that the annual number of fires in New York are out of all proportion to those in London, for instance. Rumours have reached me from time to time that there is an organized gang of ruffians, who make it their business to set fire to premises in such a way that the brigade are unable to prevent anything short of total loss. Of course, the game is to insure a bogus stock, and then bleed the insurance companies."

"And I'm to find out whether this is true or not?"

"Oh, it's true enough," Pryde exclaimed. "One of the gang told me all that in this very office. That little bit of information cost our old man five hundred dollars, and cheap at the price."

"Why didn't the chap go to the police?"

"Said the sight of an officer always made him faint," Pryde said, drily. "Besides, there was money in coming here, and revenge, too, because Jacob Reski has quarrelled with the gang and means to expose them—or, rather, he proposes to leave the exposure to us. There's all the material for a big thing here; and I'm putting it in your hands to exploit."

Denn was interested. There was all the material ready for a pretty adventure, to say nothing of rare journalistic kudos at the finish. And Denn was always ready to sacrifice his dinner for an adventure. His sheer love of danger made him the pearl of correspondents that he was.

When the Post people lent themselves to these classic exposures money was quite a secondary consideration. With his straw hat tilted over his eyes, Denn rapidly thought the matter out.

"I shall have to take the role of a German Jew trader," he said. "You must set me up in business with a bogus stock and a big insurance. I shall leave you to make it all square with the insurance people. All I ask you to do now is to bring Reski and myself together."

In the course of a day or two the matter was arranged. In the purlieus of New York Denn discovered a Semitic gentleman anxious to return to Germany, and who was only too glad to dispose of his lease and stock for a consideration. The insurance people were naturally ready to fall in with any scheme calculated to put a stop to the progress of the "Fire Bugs." Not only did they issue a heavy policy to Nicholas Mayer—Denn's nom de guerre—but they also considerately dated the policy three years back, and gave Denn receipts for all premiums.

Denn deemed it prudent to potter about his newly-obtained premises for a few days before he took any further steps. Business troubled him not at all, for the simple reason that there did not seem to be any. And the sixth evening, after dark, Jacob Reski appeared.

He was a little man with a glittering, evil eye, and the liquid speech of a born histrion. Within the hour he had imparted to Denn information that caused the latter to long for immediate action.

"I'm afraid I can't assist you any further," Reski concluded. "I'll show you where Moses Part and the rest of the gang make their head-quarters. You'll easily manage it if you know your way about."

Denn hastened to assure the speaker that his bump of locality left nothing to be desired. An hour later, carefully disguised, he found himself seated alone in one of the most evil and unsavoury saloons in the Bowery. Some time elapsed before Denn began to spot his men. They were exceedingly shy and suspicious to begin with, but Denn was an adept at the game, and ere the evening had passed he had convinced them that he was as great a blackguard as anyone there.

It was an evening or two later before Denn dared to come to the point. Moses Part, a picturesque ruffian with one eye, gave him the lead. Altogether the "Fire Bugs" were five in number. Taking them by and large, a more repulsive quintette it would have been hard to imagine.

Denn listened to their exploits with a smile which concealed a longing to whip out a revolver and clear the party on sight. If all they said was true, the insurance companies must have been robbed of millions of dollars. Many fires resulting in serious loss of life were openly owned to by the ruffians around Denn.

"I've half a mind," he said, hesitatingly, "to get you to grease my little lot."

Moses Part pricked up his ears.

"And what have you got?" he asked, eagerly. "Ach, I knew it was coming. I guessed what you was after the first night you was here."

Denn admitted his store in Tiffany Street. There was practically no stock, though at one time the business had been a flourishing one, which statement Denn concluded with a cocking of his little finger.

"Have you a bolicy?" Part asked, nasally.

"For ten thousand dollars," Denn responded. "A policy three years old and all the premiums paid. You can see it for yourself."

Part's eye gleamed over this treasure. Everything appeared to be perfectly in order. And a policy three years old was a gem rarely handled by the "Fire Bugs."

Part's eye gleamed over this treasure.

"Mine friendt," he said, earnestly, " dose dollars was already in our bockets. Half for you and the rest between us. Not dat we trust you altogether, ach no. You assign your stock and bolicy to a friendt of mine first, and then we get to work. I will come to your little place to-morrow after dark and plan out the thing exactly."

DRENTON DENN's professional instinct led him on to a good thing as surely as a steady hound on the trail. And he was now on one of the biggest "scoops" of his career. How deep and wide were the ramifications of the "Fire Bugs" the New York authorities never dreamed. That there was something wrong somewhere they were vaguely aware, and more than one insurance corporation writhed uneasy before the spectral dividend. Arson was steadily gaining in popularity, being at the same time remunerative and exceedingly hard to prove. That an organized gang were working the thing scientifically was known only to the select few.

Nor was Drenton Denn aware what a big thing it was until he went carefully into figures. Per head of the population, the New York fires were as four to one compared to London, even with the latter handicapped by the deadly low flash-point, and the loss of life owing to the conflagrations was in a still more startling ratio.

Indeed, the "Fire Bugs" seemed to rather like sacrificing a life or two. It lent realism to the crime and averted suspicion. The more Denn dwelt on the matter, the clearer did he see that he was on the brink of a tragedy calculated to move continents.

With the omnivorous appetite of the Pressman he wanted everything for himself and his paper. The exposure of the doings of the "Fire Bugs" and the hunting down of the gang must be all his own. He knew quite enough now to cause the arrest and conviction of Moses Part and his merry men, but, as to their methods, Denn had yet a great deal to learn.

But that was all coming. In the part of Nicholas Mayer, Denn could see everything when his establishment in Tiffany Street was primed for the destroyer. The assurance policy had been duly assigned, and, this being done, Moses Part set to work at once. Two nights later a cart drove up to 611, Tiffany Street, and deposited certain innocent-looking packages at Denn's ostensible business premises. A little later on Part came along, followed by the rest of the infamous gang. The packages contained a drum or two of petroleum, some scores of yards of thick hay-bands, a few shallow wooden tubs, and a basket or two of corks. Evidently the "Fire Bug" business was an art.

"We'll get to work at once," said Part. "In a couple of hours' time there won't be much left of this crazy old show."

Denn watched the proceedings with the greatest interest. The four men worked silently together as if drilled to the part. There were three floors to the house altogether, and it speedily became evident to Denn that the idea was to set them aflame instantaneously.

In the centre of the shop—or warehouse, rather—situated at the back of the premises, Moses Part placed one of the flat, shallow tubs. Into this one of his confederates proceeded to pour a quantity of petroleum. On the top of the blue spirit he sprinkled corks until the surface was covered. Then the end of the fluffy hay-band was placed in the tub and dragged across the floor. Into the hay-band naphtha had been rubbed. Like a scaly snake the hay-band was carried up the stairs and twisted in and out of the banisters until the next floor was reached, and here another tub of paraffin, corks and all, was similarly placed as below. Once more the same programme was gone through, until the hay-band ended in a tub of petroleum on the top floor. Around these two latter tanks Part and his men collected shavings, pieces of paper, cardboard boxes, and the like.

"All done," Part growled. "There's only one more thing now."

Dunn looked up at the speaker. His hooked nose was curved over his thick upper lip in a horrible smile. It seemed to Denn that his eyes were aflame with anger. Then Part looked down again, and the evil flame died out like a passing fire.

"What's that?" Denn asked, suspiciously.

"It's to set fire to the show," Part hastened to respond. "That's all."

"It's to set fire to the show. That's all."

Denn remarked that he hadn't quite got the hang of it. He was vaguely conscious that things were not altogether right, but as a conscientious journalist he could not afford to neglect detail. The popular voracity for detail he fully understood.

"Come down to the basement, and I'll show you," said Part. "What we want to get is a fire in three places at once."

"I think I understand," said Denn.

Again that terrible smile came flashing over Part's face.

"I'm sure you will presently," he muttered. "Leading up to yonder tub is a slow match. This will burn for half an hour before it reaches the petroleum, and give us all a chance to get away in safety. Directly the flame gets to the oil those casks begin to blaze, and the sides of the tub are on fire also. As they burn down the blazing oil runs all over the floor. Meanwhile the hay-band carries the flame rapidly upstairs to the next tub, and so on to the top floor of the house. Within ten minutes there are three roaring fires going on three floors. You see, my friendt?"

"Precisely," Denn responded, not without enthusiasm. "A most ingenious idea! No wonder that your movements are hard to follow."

"And there is nothing else we can tell you?"

Denn looked up suddenly. There was an ominous change in the timbre of Part's voice, a ring that clearly spoke of danger. And it seemed to Denn that the rest of the gang gathered threateningly around him. As he glanced to the door, Part smiled grimly.

"There is nothing else," said Denn.

"So; then you are completely satisfied? Now you know everything of the method of the 'Fire Bugs.' As what you call merely a guarantee of good faith, and not for publication."

"What on earth do you mean by that?"

"Ach! What a question to be asked by Mr. Drenton Denn!"

Every muscle in Denn's body drew taut and trembling. He wasted no time in words, for he was essentially a man of action. Almost before Part had ceased to speak, Denn had flown at him like a cat. A small, compact fist, shod with knuckles like steel, caught Part fairly on the point of the jaw, and down he went like an empty sack.

Denn flashed round, and another ruffian dropped sideways before a tremendous blow behind the ear. Denn slipped for the door. As he did so a foot shot out and locked his instep, and Denn staggered and fell. Instantly the other two dropped a-top of him.

Denn flashed round, and another ruffian dropped sideways.

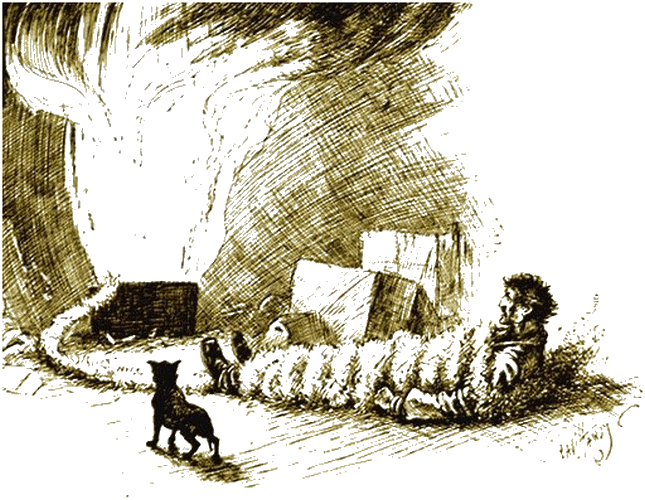

It was a hopeless struggle from the first—a grim silence, broken only by the heavy breathing of three panting bodies, and the · whining barking of Denn's dog quivering in a distant corner. Denn fought with all the tenacious courage of despair, till a bash, fairly between the eyes. caused the stars to flash and dazzle, and induced a tendency to drowsiness.

When Derm came to himself again his hands were securely fastened by a thong of rawhide, as also were his feet. Part, with an ugly grin on his face, and a mat of blood in his beard, was busily engaged in hammering two strong staples into the black, oaken floor.

"What's your game?" Denn asked, between his teeth.

"You'll find that out presently," Part retorted. "We've known who you were for a day or two, for all your clever disguise. And so you thought you were going to fnd out our secrets, and give us away as you did Dick Daly's boys? Ach, you are a very clever man, but not clever enough to know we should keep a close watch on Jacob Reski. And when he went to your office—"

"Enough said," Denn interrupted. "What are these staples for?"

"To fasten you down to the floor. Oh, we are going to give you every opportunity of seeing how it's done. And we are going to wind part of that hay-band round your body so that the fire will pass all round you on its way to the next floor. A bit painful, perhaps, but it's going to be done, And when the house is burnt down and you with it, we shall just go and collect your insurance money, Mr. Denn."

Denn checked a sudden desire to speak. Then he smiled grimly. If he was to he tortured first and burnt alive afterwards, he would die with one satisfaction in his heart. The man who called to collect the insurance money on that assignment would have an unpleasant surprise.

Bitterly Denn cursed his own imprudences. He might just as well have had assistance close to hand in case of accident. But professional pride and jealousy, the desire to do everything off his own bat, had been his undoing. There was no help for it now. Of fear, Denn gave no sign whatever. Nor was he afraid. The dominating emotion was rage and anger at his own folly.

"Very well," he said, "do your worst. For the present I am quite helpless. I am not afraid of you."

"Oh, you're not that," muttered Part. "Seems a pity to waste so good a man. I only wish I'd got a dozen like you."

DENN offered no opposition to the scoundrels. Such a thing would be futile and childish, and might, moreover, result in a tap on the head that would render him independent of this mundane sphere for all time; whereas, whilst there is life there is hope, and some chain of fate might yet temper the wind. Denn's nature was, above all things, buoyant.

The loose slack of hay—band was twisted round and round him up to the shoulders, so that presently he would be in a zone of seething flame, and utterly powerless to arrest its progress on its errand of destruction. He would have to lie there quivering with the anguish of the diabolical torture until the collapse of the house would bring merciful oblivion.

At the expiration of five minutes Denn was stretched out on the floor taut and rigid, his feet and shoulders extended painfully by the raw-hide straps that were attached to the staples in the floor. His arms were pinned to his sides. There was a touch of the tortures of Tantalus in this. The hope that Denn might get his hands free would only add to his mental agony. Part regarded his handicraft with grim satisfaction.

"I fancy you'll do now," he said. "If you do manage to escape you'll have something to write about that will do the Post good. Quite comfortable? "

Denn's eyes flashed like frosty stars. "I cannot sufficiently thank you for all this attention," he snapped. "Do you think I am going to show the white feather, you dog? Go and leave me to die like a man. Be off with you."

Part backed away, with a mocking bow.

"Good night," he said. "It's a cold evening, and perhaps I ought to have thrown a rug over you. Now, do you think you will be warm enough?"

Denn laughed aloud—he would have been puzzled to say why. In dire peril as he was, the grim humour of the speech was not lost upon him. Then he heard footsteps echoing over the bare floor, and the sullen bang of a door.

A sudden change of mood came over Denn. He tugged at his bands until a chafed crimson outlined his wrists; then he desisted, and burst into a fit of tears. Terrible tears they were—tears of blood, of anger, and not of fear. Denn wept out of sheer passionate impotence. Something warm lapped up the brine from his cheeks. The slobbering, caressing touch soothed Denn strangely, though he would have found it hard to say why. There was some comfort in the unexpected presence of his terrier, but under the circumstances a dog was not altogether an ally in the face of danger.

"How did you get here, Prince?" Denn asked.

The dog whined and quivered from head to foot. His canine intelligence told him that his master was in bad case.

"You are a comfort, certainly," Denn Went on, "the same as a chaplain might be to a convict on the morn of his execution. Your presence, Prince, may enable me to retain my senses—always a valuable possession even to a man in extremes like myself There is just a chance even for me. You are a clever dog, an exceedingly clever dog, Prince, but there are limits to your sagacity. If I could only make you understand the necessity of gnawing away these thongs of mine, all would be well. As it is, you can do nothing for me."

Out of the tail of his eye Denn noticed the sullen red spark of the slow match Creeping on towards the tub of paraffin. In the intense silence of the place he could hear the splutter of saltpetre. Surely it must be more than an hour since Part's departure.

The flame crept along like a snail. Denn watched it in a dazed, fascinated kind of way. The slow monotony of it was getting on his nerves. He caught himself almost longing for the flash and the flare which sooner or later must come from the tub.

Then another paroxysm of frenzy shook him to the soul. When the desire to struggle had passed away, Denn was dripping from head to foot. He smiled in bitter mockery of himself. Never had his senses been so preternaturally clear as they were at that present moment.

Taking his master's struggles as part of a game, Prince had commenced to frisk around, barking loudly. Denn's endeavours had caused the hay-band to wriggle slightly, and upon this Prince pounced, shaking it as if it had been a rat. The acrid taste of the paraffin was not pleasing, but Prince went at it again quite angrily.

"Good God!" Denn cried. "The one hope lies there!"

There was a fizz and a flash, and immediately the room was filled with a huge yellow flame. A dense black smoke rose to the ceiling; fatty, smutty flakes fell like black snow. The first tub of petroleum was on fire, and broke the silence with a sullen roar.

There was a fizz and a flash...

Denn grated his teeth together. He saw the end of the hay-band slide from the edge of the tub and lie on the floor. There was just a faint chance that it might not have caught the flame.

But that hope was instantly dissipated. A hissing blue flame came dancing along in Denn's direction. Just for a moment the whole universe reeled around him. The reaction threatened to swamp his senses.

But only for a moment, and then his intense nervous energy returned to him. A buoyant and virile nature like Denn's is not easily crushed out. Hope, hope—there was always hope whilst life lasted.

That he was about to be burnt, and badly burnt, Denn knew perfectly well. The shock might kill him. But though this poor human machinery of ours is easily thrown out of gear, it is surprising what humanity can endure and still draw the breath of life.

Denn could not die; he would not faint. The petroleum still blazed fiercely; the blue popping flame from the corks rose and fell. The dense cloud of smoke drifted round the room, eventually finding an outlet by means of a window or skylight rather high up in one corner. Part and his gang knew their business thoroughly, and fully appreciated draught as an aid to their endeavours.

As the blazing point of flame struck his leg, Denn shivered. Near and round him went the blaze, scorching his clothing and leaving a huge white bladder spirally round his frame.

The agony was intense: so keen, and incisive, that Denn was dripping from head to foot. Still he retained his senses. As the zone of fire rose to his waist he controlled himself by an almost superhuman effort to be still. Then he deliberately held his hands to the blaze. There was a smell of singed leather, and immediately the thongs that bound his wrists gave way. Only the lierce exultation in the knowledge that he had won something kept Denn going.

When his hands were free Denn threw his arms apart. With his hands above his head he had no great difficulty in getting his shoulders free.

Hope spurred him on like generous wine. He had only to rid himself of the green thongs that confined his ankles to the staples, and he would be free. Unfortunately, these bonds had not suffered from the flames. Try as he would, Denn could not rid himself of these. He had no knife in his pocket, and to try to loosen the light, damp knots with fingers like white bladders was impossible.

"Done, after all," Denn groaned. "I'm as fast bound here as a convict fettered to the floor of his cell."

All this had been, more or less, the work of seconds. He saw now that the first tub of oil was burning away, and the lighted fluid was flowing over the hard oak floor. On the other side the hay-band was carrying a red cone of fire towards the staircase.

As it progressed, Prince followed, barking furiously. A sudden idea occurred to Denn : there was just a chance yet.

"Worry, worry," he cried. "Rats, rats; pull him down, Prince!"

The dog barked more furiously than ever. He grasped the hay—band some way beyond the point of flame, and began to tug vigorously. Prince had evidently made up his mind not to be defeated. His sharp teeth mumbled and worried at the rope: there came a sound of something tearing, and then—the band parted!

A terrible, hoarse cry came from Denn's throat. Prince set up and howled. Denn called the dog to him and kissed the shaggy head.

"My lad," he said, hoarsely, "I guess you've about saved my life. You shall have a gold collar set in diamonds and jewelled in sixteen holes. What nonsense I am talking! At any rate, there will be no fire now, since you have cut off the communication. Yonder flowing petroleum wont do much harm upon the hard oak floor. If you could only worry the thongs off my ankles for me—"

Denn said no more. The floor seemed to rise miles upwards and then fall again, shooting the hapless man down into bottomless space. Ten millions of stars danced before his eyes; there was a roar like the sea in his ears.

The reaction had come, and Denn had fainted. Prince sat there still and silent, his black nose quivering. The small body of the terrier absolutely bristled with excitement and expectation.

WHEN Denn came to himself it seemed to him vaguely as if several years had elapsed since he had slipped from consciousness. He passed his hand over his chin to feel for his beard, as Rip Van Winkle might. But no beard was there, and no flame was in the room either. The "Fire Bugs" had made a misealculation so far as the ground floor was concerned, for the paraffin in the tub had burnt away with no greater effect than a deep excoriation of the stout oaken boards. A smell of burnt wood came pungently to Denn's nostrils, but the air was clear of smoke and the danger past.

The pain Denn suffered from his wounds was something dreadful. But nothing could crush down the fierce exultation at his heart, the knowledge that by sheer grit and fortunate chance he had baffled his enemies.

Still, Denn was not out of the wood yet. The thongs about his ankles still held him prisoner to the staple. Had his hands been less swollen and blistered he might have freed himself, but with all his pluck he could grasp nothing whatever, so far as his left hand was concerned. The right was not so badly scorched.

"It's very disheartening," Denn muttered. "Those fellows are not far off, and ere long one or more of them are certain to turn up and investigate into the postponement of the fireworks. Then where shall I be?"

All the same, Denn did not relax his efforts. An hour passed with no very definite results, and then a draught of air proclaimed the fact that the front door had been cautiously opened.

Prince sat up quivering, his ears a-cock, and his teeth displayed in a snarl.

Denn cuffed him gently.

"Down," he whispered, "down, sir. Not a sound."

Prince crouched obediently. Denn lay sideways as if dead. A figure crept in, making no noise, in his india—rubber slippers. He approached Denn and stood over him. The latter never moved.

"He's done for," Part, for he it was, chuckled grimly. "The charred remains of the unfortunate proprietor were found mit der ruins! That is what the papers will say. No suspicion after that. I suppose that hay-band must have parted in some way. A match will put that all right. Good-bye, Mr. Drenton Denn."

And Part spurned the prostrate figure with his foot. A fraction of a second later, and a yell of agony rang through the house. The hidden vein of ferocity lying dormant in every man rose in Denn at this moment.

There was just one tiny chance of safety, and Denn grasped it. Like lightning, he grabbed Part by the feet and buried his teeth like a dog in the ruffian's tendon Achilles.

With his other foot Part lashed out savagely. Denn caught him by the instep and brought him crashing to the ground. Not for an instant did the tension of those jaws relax on Part's heel.

Denn caught him by the instep.

"Mein Gott, what agony!" Part screamed.

"And it's going to be agony," Denn mumbled, "until you cut the strip that binds my ankles. I've got you at a disadvantage now, you hound, and I mean to keep it. Out with your knife and do as I tell you."

Trembling with anguish in every limb, Part drew a knife from bispocket. As he was fumbling with the green hide, Denn dexterouslyi managed to extract Part's revolver from his hip pocket.

Denn's limbs were free at last. Stiff and sore as he was he managed to regain his feet, only to see Part rushing upon him knife in hand. But he was instantly covered with his own revolver.

"Stand back or I fire," Denn cried. "It's my turn now, my friend. You have some matches in your pocket, of course. On the window-ledge you will find some candles. Light one."

Part sullenly obeyed. There was something crisp and metallic in Denn's voice that precluded any debate upon the point. If Part had only known how sick, and dazed, and dizzy Denn was feeling, his discomfiture might have been less. As it was, the ruffian was completely cowed.

"Now take a scrap of paper and a pencil. There's one on the table. Of course, the other ruffians are awaiting your return in the den of the Bowery. Now write what I tell you. Say: 'Something wrong at Nicholas Mayer's. Come to me all of you as soon as you get this!' By heavens, if you don't do as you are told I'll let daylight into you." Part obeyed, sullenly. The letter was folded and addressed to his second in command. Denn opened a window looking on a side street, and hailed the first likely-looking gutter-snipe that passed.

"Do you Want to earn a dollar?" he asked.

The arab raised no particular objection, and was sent on his errand. He was simply to deliver the note, and nothing more. A police-oliicer lounging down the street looked at Denn suspiciously.

"Anything wrong here?" he demanded.

"You've got it first time," Denn responded. "There's something so wrong here that all America will be ringing with it in a day or two. Go on to Patrick Road police-station and send four of your best men here. And for the love of Heaven, lose no time about it."

Ten minutes later four stalwart men were gathered round about Denn and his discomfited companion, listening to the former's tale.

Denn fainted twice during the recital, but he minded that not in the least now. All the same, he had been terribly afraid of this sickness during the time that he had found himself alone with Part.

Hardly was the recital finished when Part's satellites came bursting into the house, eager to know what was wrong. Before they could realize the nature of the cruel trap laid for them the whole gang were secured. The chief officer would have grasped Denn eagerly by the hand.

"No, thanks," the latter said, hastily. "I'm not feeling quite up to social amenities of that kind. You have your men and you have your evidence, and when you find that insurance policy, your case will be complete. And you now have the satisfaction of ridding New York of perhaps the cleverest gang of pestiferous scoundrels that ever disgraced civilization. God knows how many innocent lives have been sacrificed to satisfy their greed."

"And meanwhile, Mr. Denn," said the inspector, "you—"

"Will go straight to Barnabas Hospital," Denn said, promptly. "I want a strong tonic to pull me together, and a smart type- writer will do the rest. Once the Post is in possession of all these facts, I shall take a rest. And I want you to know that I need it."

The Post had it all the next morning, thanks to Denn's pluck and determination. At what time New York was thrilling over these revelations, Denn, with head shaven and temperature up to 103, tossed on his hospital bed babbling of strange things. The "special" was there all the same. And as to the subsequent career of the "Fire Bugs," are they not written in the annals of the New York police, so that he who wills may read?