RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

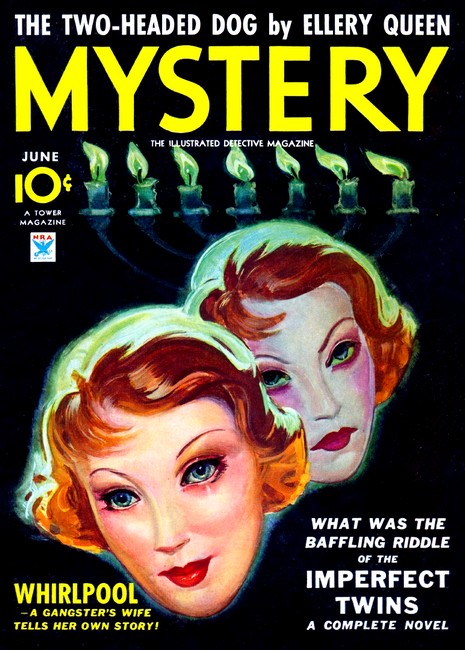

Mystery, June 1934, with "The Woman He Had to Kill!

The editors elect this story as one of the most human, heart-stirring mystery dramas ever published in this magazine! If you don't want your emotions torn to shreds; if you don't want to sympathise with a murderer, don't read this story! A mystery masterpiece by—Francis Beeding.

ALFRED INGLEBY poked the dying wood fire into a blaze and threw on another log. A few sparks shot up the chimney. Ingleby gazed at them resentfully. A fire was about the only thing he could still afford. Wood was to be had for the chopping, plenty of it outside in the forest—that great belt of trees stretching right across the green and pleasant land of Sussex.

He had a letter in the hand that lay listless upon his knee. He had read it many times since eating; the slice of bread and the very small chip of cheese which had done duty for lunch. He hardly ever opened letters now. He wished he had not opened this one. It was terse and to the point. He had it almost by heart. It was from Messrs. Blatchett and Blatchett. solicitors at Haywards Heath, and it informed him that they had been instructed to act for his creditors. His creditors were to meet, it seemed, at The Long Man in three days' time, and his presence was urgently requested. He detected in this last catastrophe the hand of old Burstard. Old Burstard was rich and the rich were always keener after their money than the poor. That was why they were rich. Old Burstard had lent him only twenty-five pounds, though he had asked for fifty. And now, of course, he had stirred the others up, paid a round of visits in that ram-shackled old car of his though they said he was rich enough to run a Rolls if he liked and had got hold of the other victims. Victims... that was the word. He could hear old Burstard using it. There was Popplethwaite, the butcher in Adenham, and Townshend of Wynstead, who supplied agricultural machinery. He owed Townshend a hundred and thirty of the best, the balance of an expenditure of 200 on ploughs and threshers... Crows round the carcass, that's what they were, and a dashed lean carcass it was! Ingleby raised his gaunt face, lit by a sullen »mile. They have got me beat, he muttered to himself; and an odd feeling of satisfaction pervaded him. At any rate, this was the end. He would never have to struggle any more. He had touched rock bottom.

HE rose from the rickety basket-chair with its faded cushions, and crossed the room to the dresser, a stout oak piece... Jacobean, he had heard it said, worth a bit of money; good cottage stuff. Old Burstard would get it now, he supposed.... But not what was inside it. No, by Cod, he would see to that! One hand closed on the neck of a bottle and drew it out of the dresser, while the other sought a corkscrew in the pocket of his old coat.

The cork came out with a slight protesting squeak. Pre-war whisky and seven bottles still left.... The only sound thing his father had left him. He poured a generous measure into a tumbler and, adding a little water, drank it off at a gulp. Then he returned to the fire and sat down with the bottle between his feet.

He ran a thick hand, on which the nails were broken and dirty with hard toil, through his thinning hair, and gazed into the logs, looking over the years of his failure. He had not expected this. Nor had he deserved it.... Three years in the army, an acting sergeant... gassed in that foul show in Sanctuary Wood... Gassed... gassed... invalided out on a pound-a-week pension. Told he was lucky to get that much. The pension had long since been commuted and sunk in the clay and mud of the farm.

Ingleby drank again, long and deep. That was good stuff, the best thing the old man had left behind him.

Why had it come to this? Could anyone have made a better fight for it? He had taken over the farm, commuted his pension, raised money how, when and where he could, worked like a slave, though sometimes that cough tore his chest inside-out and he would start spitting that horrid yellow stuff that he thought he had got rid of in the hospital. And now he was to be put on the mat by old Burstard, and see his home, and what was left inside it, sold over his head. Not that it was much to boast about—little more than a clearing in the woods, five miles away from a decent market, at the end of a mud track half a mile long. But it was all the home he had known. He would have to start again... start again ... He was thirty-eight looked forty-eight, and felt even older than he looked.

Ingleby drank again.

That was better... He would attend that meeting at The Long Man... tell old Burstard what he thought of him... give him something to remember, teach the old Shylock to put the screw on an ex-service man. Yes, by God, he would!

He looked round the room, now very dark. Fantastic shadows played across the uneven walls from which the roughcast plaster was peeling, and the dresser crouching against the wall seemed suddenly menacing. A tall high-backed chair standing in a dark corner raised its protesting arms in the shadows.

A loud knock fell upon the door.

Alfred Ingleby, more than a little drunk, staggered across the room to answer it.

"ADVERTISEMENT?" said Ingleby. "What do you mean by that?"

He was seated at the table. There was a lamp upon it, smoking a bit, for the wick wanted trimming. Opposite him was old Baines, the postman, in his uniform, his beard all wet and straggling, his old eyes misty behind a pair of steel-rimmed spectacles, drinking a glass of the pre-war whisky.

Not a bad chap, old Baines. Always friendly when he met you down at The Long Man.

Old Baines was fumbling in the pocket of his blue jacket. After a bit of a struggle he produced the crumpled remains of a copy of the Times.

"Here you are, lad," he said. "The paper was left behind at The Long Man by a salesman. He was reading it only last night and we came across your name. There you are. Read it yourself."

Ingleby stretched a hand that shook, across the table and picked up the paper. It was a little time before his eyes could focus the small print of the personal column, but there at last it was—his name, in capital letters.

"INGLEBY. If Alfred Ingleby, son of the late John Ingleby of Cripps Corner, Adenham, Sussex, will communicate with Messrs Dutton and Thoroughgood, 418 Lincoln's Inn Fields, W.C.2., he will hear of something to his advantage."

Ingleby stared at the notice.

"It's all right, lad, isn't it?" came the voice of old Baines, seemingly from a distance.

"Seems to be all right," assented Ingleby.

"What we could not understand," continued Baines, "was why they did not write to you direct instead of putting that thing in the paper."

"Perhaps they did," returned Ingleby. "I haven't been opening any letters lately. Too depressing... I just toss them into the fire."

"Well," said Baines, "you never know your luck. If we had not seen that advertisement, you might never have had the legacy."

"Legacy," said Ingleby. "I don't see any mention of that."

"It's sure to be a legacy," Baines cheerfully assured him, getting to his feet and draining his glass. "You must'a lost a rich relative. But I must be getting along. Thanks for the drink, lad. As nice a drop of Scotch as ever I tasted."

It was Irish whisky, but Ingleby did not put the old man right and scarcely saw him go out. He sat there gazing at that astonishing notice in the Times, and weaving pleasant dreams. And the dreams became continually more pleasant as the bottle became continually lighter, till at last he saw himself in a black coat and striped trousers driving a handsome cab to the gates of old Burstard's farm to mock him in his lair.

"Something to his advantage..." Ingleby, after several unsuccessful attempts, struck a match and peered into the face of the grandfather clock. That was another relic of the old days. His watch had long since gone to the pawnbroker... Half-past nine. It was no good trying to get to London that night. Besides he had not even the fare. He counted the coins in his jacket... Four shillings and sevenpence... that was not enough, and he must somehow raise the balance. After some thought he lit the end of a candle which he thrust into a tin lantern and, opening the door, passed out into the night.

There came a furious flutter of wings and a shrill squawking from the henhouse. Presently he returned with something warm and wet flapping in his hands.

Ingleby inspected his prize hen and prodded her in the breast beneath the wings, while she struggled to escape his detaining hand.

"Not much on you, but you're the best of the bunch." he murmured as he wrung her neck.

IT was past eleven when he entered Victoria Station the next morning. He had put on his one moderately decent suit, light brown, bought second-hand at Brighton five years before, pretty shiny in places, but good enough if you kept out of the strong light. Jane, the prize hen, had fetched six-and-eight pence from Swan at Adenham. Six-and-eightpence with the four-and sevenpence he had found in his pocket had bought him a third-class return ticket to London and left him with one-and-four pence to spare. The price of the hen had amused Ingleby all the way up. Six-and-eightpence! It was a lawyer's fee, and he was going to see a lawyer!

Lord, it was good to be in London again. Even though you did feel a hopeless stranger and not a little inclined to scuttle across the traffic-ridden streets with one eye on the policeman. Ingleby sniffed the sooty air with satisfaction as he walked toward the Underground which would bear him to the Temple.

His head was rather thick, and there was an unpleasant taste in his mouth; but that prewar stuff was good and the morning after not, therefore, so bad. The only thing that troubled him was his boots, for he had been obliged to walk three and a half muddy miles to Adenham. Outside the Temple Station he paused and, with reckless extravagance, expended fourpencc in having them cleaned. Then, passing through the garden, he found himself in the square, looking for the front door of Messrs. Dutton and Thoroughgood.

He paused a moment in front of that shiny piece of mahogany. The whole thing seemed suddenly fantastic. What was he doing here in the middle of the City of London (he had not been to London for six years) with the traffic roaring in Fleet Street, a few hundred yards away? He fumbled in the pocket of his shabby overcoat and pulled out the advertisement, reading it again for confirmation. Yes... there it was in black and white.

"Here goes." he said to himself and, pushing open the door, he strode in and dealt briskly with the supercilious clerk who greeted him.

Twenty minutes later he found himself facing Mr. Thoroughgood in person.

Mr. Thoroughgood was neat, small and compact, with carefully-arranged hair, and a red clean-shaven face.

He wasted no time.

"First," he said, "we must establish your identity."

Ingleby was prepared for that. The night before, he had searched amongst his father's papers and among them he had found the certificate of his own birth and of his mother's marriage.

These he produced, to the professional satisfaction of Mr. Thoroughgood.

"Well, Mr. Ingleby," said the lawyer, lapping the certificates with a manicured forefinger, "the facts are simple. The advertisement to which you have replied was inserted at the request of Miss Agatha Ingleby of"—(here he glanced at a memorandum)—"426 Parliament Hill, Hampstead. She was your father's elder sister, I believe."

Ingleby nodded.

"We have dealt with her affair," continued Mr. Thoroughgood, "for over thirty years, but I regret to inform you that we shall not be dealing with them for very much longer. Miss Ingleby has been in poor health for some time and has recently informed me that she is suffering from a fatal disease. It is cancer, Mr. Ingleby, and, I fear, quite incurable." He paused.

"Your aunt," he continued, "has made several attempts, both direct and through ourselves, to get in touch with you. We received, however, no reply to our letters."

Ingleby smiled awkwardly.

"I am pretty bad at answering letters," he said, "and recently I have neglected even to open them." Mr. Thoroughgood looked at Ingleby. Ingleby did not stir. He did not realise it yet. It seemed, however, that the lawyer expected him to say something.

"Er, yes," he said awkwardly, "I quite understand—her heir..."

Then it came upon him suddenly. Old Baines had been right. This was the legacy... No, it was more than that, it was an inheritance! The blood surged to his brain.

"Is she... is she well off?"

The question burst from him. He made no attempt to conceal the eagerness of his tone.

"I am not authorised to discuss with you the private affairs of Miss Ingleby," replied Mr. Thoroughgood dryly. "But I must tell you at once that she is prepared to make you her heir, subject to certain conditions. Miss Ingleby will herself inform you of them. I shall at once communicate to her the news that we have found you, and she will doubtless get in touch with you in due course."

Ingleby gazed blankly at the lawyer. The interview, it seemed, was finished. An inheritance had been dangled in front of him, but there were conditions and he would hear from his aunt in due course. The lawyer had meanwhile risen and was holding out his hand. But Ingleby could not leave it at that. Decency be blowed... He must know more or less where he stood.

It was then that the telephone bell rang—a lucky reprieve, for Ingleby could collect his wits.

Mr. Thoroughgood had put the receiver to his ear and was speaking.

"Yes... yes... Mr. Thoroughgood speaking....

"Indeed ... as serious as that... yes... quite unexpectedly, most fortunate... he arrived here not ten minutes ago.... Yes, we will come at once... yes."

Mr. Thoroughgood replaced the receiver and put a hand to his tie. Ingleby was still wondering which of the many questions he must ask should come first, but Mr. Thoroughgood was coming round the desk toward him and it was the lawyer who spoke.

"Mr. Ingleby," he said, "your arrival here this morning seems almost providential. That was Miss Ingleby'$ doctor who telephoned. Your aunt has taken a turn for the worse; you must prepare yourself for bad news. Miss Ingleby, I fear, is dying. I am taking you to see her at once."

FIVE minutes later Alfred Ingleby, with Mr. Thoroughgood, was speeding in a taxi toward Parliament Hill as swiftly as the flow of traffic would allow, Ingleby, recovering his presence of mind, was trying to remember as much as he could of Aunt Agatha, He had not seen her for nearly twenty years. She had, while he was still at school, quarrelled royally with his father, and her name had not afterward been mentioned. His father had nevertheless been her favorite brother. Now, it seemed, on her death-bed, she desired to make amends. Anyhow, she was seeking him out as his father's son. He ought, he supposed, to feel grateful to Aunt Agatha. All he did feel, however, was a devouring curiosity as to how much money she was leaving and how soon he mighty hope to receive it. She must, he surmised, be pretty well off. Parliament Hill was a good neighborhood. Ingleby saw himself suddenly able to walk into old Burstard's office, rap down his twenty-five pounds on the table and tell him to go to the devil. Then he would settle with his other creditors. Prosperity might bloom at last for Cripps Corner.

The taxi stopped with a jerk outside a tall semi-detached house, one of half a hundred that lined the steep road which ended in the Heath. It was a day of wind and rain in early December. Great clouds scudded across the uncertain sky. There was a smell of soot and damp leaves in the air. He followed Mr. Thoroughgood up the whitened steps.

The door was opened by an elderly maid, her face marred with weeping.

"Come in, sir." she said.

Mr. Thoroughgood passed with Ingleby into the dark hall. They were met at the foot of the stairs by a tall thin man in a short black coat and striped trousers.

He introduced himself shortly.

"I am Dr. Thwaites," he announced. "You, I imagine, are Thoroughgood?"

Mr. Thoroughgood nodded.

"I am afraid you have come too late," said the doctor. "Miss Ingleby died twenty minutes ago. She has signed the will, however, and she asked me to give it to you."

He produced from his pocket a folded document and handed it to the lawyer.

"Thank you, doctor," he said, "This, by the way is Mr. Ingleby, her nephew."

The doctor bowed.

"There is nothing more I can do here, I am afraid," he said. "Your aunt, Mr. Ingleby, has suffered from cancer for some years and I am afraid she had rather a bad time during the last fortnight. We did our best, however. Perhaps you would like to go up. Miss Wildshawe is with her. I will leave the death certificate on the hall table, and you can... Dr... make the necessary arrangements tomorrow."

"I hope you will act for me, Mr. Thoroughgood," said Ingleby, as they mounted the stairs, "until the contents of the will are known."

"Thank you, thank you," said Mr. Thoroughgood absently.

The doctor quietly took his leave and Mr. Thoroughgood took Ingleby to the first floor. They entered together a large bedroom, filled mostly with a huge mid-Victorian mahogany bed and an enormous wardrobe. The air was close and there was a faint smell of drugs, It was very dark, for the blinds were already pulled down. On the bed, covered to the chin with a sheet, lay a silent figure. Ingleby stepped forward and looked down at the quiet face.

"So that's Aunt Agatha," he said.

There was a moment's silence. The lawyer coughed. There came a short sob from the other side of the bed. Ingleby looked across. A woman had risen and was standing opposite him. He peered at her a little through the gloom. It seemed at first that the woman had no face. Then he saw that it was almost covered in bandages which allowed only the nose, eyes and mouth to appear. The mouth twisted itself into a kind of smile.

"I am Miss Wildshawe," it said.

Ingleby bowed.

"Miss Wildshawe," came the voice of Mr. Thoroughgood from the foot of the bed, "has been with Miss Ingleby for the last ten years."

"I was sorry to hear about your accident. Miss Wildshawe," he continued.

"Thank you," replied the mouth, "the scars are healing well. Dr. Thwaites says that the bandages can come off in a few days and that there will be no permanent disfigurement."

"Miss Wildshawe," explained Mr. Thoroughgood, "had an accident with a kettle seme days ago. She scalded herself somewhat severely."

"I am sorry," said Ingleby.

There was an awkward silence. All three stood gazing at the bed.

Mr. Thoroughgood coughed slightly.

"As you are both here," he began, "and as the contents of the will are known to me, I see no reason why we should not settle the formality of reading it immediately. Perhaps when you are ready to do so, you would kindly follow me to the—Dr—downstairs."

He turned toward the door. Ingleby lingered a moment. So did Miss Wildshawe, who had moved now to the bottom of the bed. Two enquiring eyes looked at him from the white mask. She was obviously waiting for Ingleby to speak.

"I—I wish I had come in time," he said at last.

Miss Wildshawe, with a sob, moved toward the door.

IT was more cheerful in the dining-room downstairs, for one thing the blinds were still up and though Miss Wildshawe made an effort to pull them down, she was prevented by the lawyer who said he must have enough light by which to read the will.

They all sat down. Then the lawyer, producing from his pocket the document which the doctor had given him, began to read.

Ingleby, oddly enough, found his attention wandering. Everything was so unexpected. He had suddenly discovered a relative he had not seen for twenty odd years. And she had left him money. Then there was this young woman. She did not look old from her figure. Nothing to write home about, of course.... But, really, he must attend.

Mr. Thoroughgood had finished reading the will, but Ingleby hadn't a notion of what it was all about.

"I'm sorry," said Ingleby, as the lawyer looked up from the paper, "but I'm afraid all this legal wording is rather beyond me."

"It's realty quite simple," said Mr. Thoroughgood. "Miss Ingleby leaves her entire property, which I may say in passing is in the neighborhood of some £500 a year, mostly in war loan, to her nephew Alfred Ingleby should he be discovered, on condition," here he paused and looked across the table at Miss Wildshawe whose expression, hidden as it was by the bandages, could not be ascertained, "on condition that he enters into a contract of marriage with Miss Wildshawe. I will read again the relevant passage of the will."

Mr. Thoroughgood cleared his throat and began to read:

"It is my firm desire that Olive Wildshawe, my devoted companion for the past twelve years, should not go unrewarded for all the care and trouble that she has taken with one who has become increasingly a burden with the passage of time. It is equally my firm desire to repair the wrong which I did my brother, William Ingleby, more than twenty years ago. I therefore desire that my property should pass to his son, Alfred Ingleby, if he be still alive at my death. Should he be unmarried, I make it a condition of the bequest that he should offer marriage to Miss Olive Wildshawe. Should she accept the offer and should the marriage take place, then my entire property will pass at once to Alfred Ingleby. Should either party feel unable to follow my wishes in this respect, then I direct that the property be held in trust for Alfred Ingleby, during the lifetime of Olive Wildshawe, who shall receive the full income from it, but that on her death it should pass absolutely to my nephew, Alfred Ingleby, or to his lawful heirs."

"I think." said the lawyer, laying the paper down, "that this is very clear. I should perhaps add, Mr. Ingleby, that if the proposed alliance is not contracted, that is to say, if your aunt's property is to be held in trust for yourself and the income paid to Miss Wildshawe during her life, you are to receive £100 free of legacy duty."

There was a long pause. Ingleby looked across the table. He had been getting used to the idea that he was the heir of Aunt Agatha. But now it seemed that he was to be annoyed with preposterous conditions—perhaps defrauded of his rights.

"You are sure this is legal?" he inquired.

"Perfectly legal," replied Mr. Thoroughgood. "The terms are usual. In fact, I may say that my client, the late Miss Ingleby, did not take my advice in the phraseology of the matter, but there can be no question of the validity of the will, and I can tell you at once that any suit brought in the courts on the ground of undue influence would undoubtedly fail."

Mr. Thoroughgood rose.

"I think you both understand the position," he said, "and I shall be grateful to receive your decision us soon as possible. I will see about probate and the death duties. You can rely on me for that."

Already he was moving toward the door and, an instant later, it closed with a click behind him.

Ingleby cleared his throat nervously as a faint slam denoted that the front door had shut upon the departing lawyer. He was not, however, the first to speak. Miss Wildshawe was leaning across the table.

"This is rather a ridiculous situation, is it not, Mr. Ingleby," she was saying. "But I assure you that it is none of my seeking. I had no idea of the terms of your aunt's will. I only knew that your aunt had in some way or other provided for me."

"Well," said Ingleby, "it can't be helped. But it's rather sudden, isn't it?"

"And now you are wondering what to do about it, I suppose," said Miss Wildshawe. "But I am going to tell you straight out that it is no good thinking of marriage."

"You are married, perhaps, already?"

Miss Wildshawe shook her head.

"No, but I am engaged. I have been engaged for five years."

There was a short pause.

"Do you mind if I smoke?" asked Ingleby.

"Not at all," she said mechanically.

"Jacob Broadbent is his name," she continued. "He is an electrician and now with Alister and Hancocks, the big firm in Holborn, and doing quite well. You would not want me to give him up, would you?"

"Er—no, Miss Wildshawe—of course not. I would not dream of it."

"I am so glad you see it like that, Mr. Ingleby," replied Miss Wildshawe. "But I quite realize that for you it is a little—hard."

Ingleby looked at her and suddenly he realized the position.

"Excuse me." he murmured, "but how old are you?"

"Thirty-one," came the answer.

Ingleby gave a short laugh.

"And I," he said, "am thirty-eight. It doesn't look as if there was much chance of the Ingleby war loan coming my way, does it. Miss Wildshawe?"

"But what can I do, Mr. Ingleby? The revenue is left to me, and Jacob is not what you might call exactly rolling."

She was speaking fast now, holding to the table with both hands.

"He's doing well, of course." she continued, "but he has not had a raise yet this year and £500 a year—we could marry at once.... I shall have to think it out."

"Not much thinking required," said Ingleby shortly. "You get £500 a year... and I got £100 free of legacy duty."

He paused. "I am glad it's free of duty," he added bitterly.

"Please. Mr. Ingleby. Nothing is yet decided."

"Humbug." he said. "You will take that legacy. You would be a fool, if you did not. You never set eyes on me before. I'm nothing to you. And there's Jacob to be considered. You will be bringing him a nice big fat dowry all of a sudden. Funny, isn't it? Damned funny."

He strode round the table. She shrank from his approach.

"A hundred pounds," he said. "And my aunt was worth how much...? Put it at a cool ten thousand. And you... you...."

He stepped back from her and looked round the room, his anger wilting as suddenly as it had grown. There was a large sideboard standing by the wall. He moved quickly toward it and pulled at the door of the cupboard in the lower half of it.

"What do you want?" demanded Miss Wildshawe.

"Damn it." he said shakily. "Isn't there even a drop of whisky in the house?"

MR. BURSTARD looked round the table.

"I think you understand the position, Mr. Ingleby." he said, thrusting forward his big beard, stained with tobacco juice. "The sheriff's officers will wait upon you tomorrow morning, and if we have not had a satisfactory settlement by this day week we shall distrain. We've waited long enough and there is no more to be said."

Ingleby stared at the advertisements for chemical manures and tractors upon the walls of the dining room of The Long Man at Adenham. He said nothing. He wanted to leap over the table, smash his fist into the red face of Mr. Burstard just above the beard, then take little Blatchett, the lawyer, by the scruff of his neck, shake him till his false teeth fell out and fling him through the window. But he only stood breathing heavily. Turning at last, he made for the door. On reaching it he faced about.

"You can go to hell," he said to the assembled company. "I have done my best for you. I've offered you a hundred pounds, which is all I am ever likely to get. Put your damned officers in when you like. It won't take them long to take an inventory of Cripps Corner."

He pushed through the door and slammed it behind him.

Now he was on the road, trudging wearily back to his farm. His brain was swimming a little, for the pre-war whisky was strong, and he had taken little else for the last two days. He had needed it, too. It kept him from brooding over that business of the legacy....

He pulled a letter from his pocket. It was in a large round feminine hand, and he read it again as he walked.

Miss Olive Wildshawe was full of the noblest sentiments. But she was sticking fast to the money. She had gone over the whole business with the lawyers who had assured her that there was nothing to be done. She had only a life interest in the money, and even if she had wished to do so, she could not pay a cent of the capital to him.

So you see, Mr. Ingleby, there is nothing I can do. I feel I must take the income. You do not realize, perhaps, what marriage means to me. I have waited five years, and when a woman is past thirty—well I am sure you will understand. I feel this is my only chance, and, after all, you are still young. You have your farm and your work to do.

Ingleby crushed the letter into a ball and made to fling it away. But he thought better of it and stuffed it with shaking fingers into the side-pocket of his coat.

To be sure he had his farm and his work to do.... And there in fancy he saw old Burstard with his little eyes, his great beard and his thick gaitered legs.

Ingleby stood suddenly still and shook his fist at the sombre trees that almost met above his bead.

He was now in the thick part of the forest, moving along the track which led to his farm. It was very dark here, for it was afternoon and the tired December day was drawing to a close. His mind, too, was dark. There seemed to be no ray of hope. Four hundred and fifty pounds he owed and he must find it in a week.

HE sat in the room for two days, rising only to replenish the fire from a great stack of logs that he had cut some weeks before, piled in the scullery outside. During that time he ate three pieces of bread and two pieces of cheese, but he drank two bottles of his father's pre-war whisky. From time to time he was vaguely aware of two little men with pencils behind their ears, who bothered him by taking stock of the contents of the house—a Landseer engraving of the Monarch of the Glen; eight copper sauce-pans in bad repair; one bedspread, torn; and so forth.

It was on the second night that the great idea came to him as he sat before the fire gazing into the glowing depths, Every man for himself now and the devil take the hindmost. It came to him suddenly, a gorgeous plan, a superb plan... copper-bottomed. Olive Wildshawe was thirty-one and he was thirty-eight. No use waiting for Olive Wildshawe to die. She might easily live another fifty years.

The idea, of course, must have been growing in some dark corner of his brain for days like a seed in the ground, out of sight and knowledge. Or had it been put there complete and ready? Almost it was as though someone had been whispering in his ear, and now at last he heard and understood. His mind had seemed to be blank and then... he was aware of the whole thing... every difficulty solved. He knew now what he must do and how he must do it.

He rose from the fire and took from the dresser a penny bottle of ink, an old pen and a sheet of paper. Then he sat crouching over the table for two hours composing the letter. That was the first part of the plan. There was only one piece of paper in the house, so he made a rough draft on the kitchen slate, for the letter must be carefully worded. He sighed with satisfaction when at last it was finished, and he read it in the light of the candles.

My dear Miss Wildshawe:

I feel that your letter of the 15th calls for some reply, but I have not answered it before because I have been taking steps, I quite realize all you say and your difficulties, especially re Mr. Broadbent. I can scarcely blame you for taking your chance. On the other hand, it would be useless for me to pretend that a small capital sum of money would not be very useful to me now.

So I have taken the liberty of consulting a young lawyer friend of mine, who was in the army with me, and we have carefully considered the whole position. He has hit upon a plan whereby we can both, I think, mutually benefit from my aunt's will with no unfairness or unpleasantness on either side. I am not too anxious, however, to put the proposal on paper at this stage. I would rather discuss the whole position with you fully and frankly before making any definite proposal. I feel sure you will understand my position in the matter, especially as you tell me that your fiancé has some scruples about this legacy. I accordingly suggest that you come down here and see me at your earliest convenience, perhaps Wednesday would suit if you have nothing better to do?

So I shall expect you, my dear Miss Wildshawe, on Wednesday, at Adenham Station. There's a train leaving London (Victoria) at 3:15 p.m. which is due here shortly after 4:30. I shall be at the station to meet you and we can come back to the farm here, meet my friend and discuss his suggestion.

I shall, of course, meet the train, but if by any chance we miss each other you have only got to follow the plan I have drawn on the back of this letter and you will find Cripps Corner easily enough. I am. Yours faithfully,

Alfred Ingleby.

P.S.—There is a fast train back from Haywards Heath at 8 p.m. I should wear some galoshes if I were you as the road to the farm is very muddy.

Ingleby sat back with a smile on his lips. It was a clever bit of work—specially that bit about the plan on he back of the letter. For she would naturally bring it with her in case she needed it to find her way. And the postscripts were killing... galoshes and a fast train back from Haywards Heath... killing!

Ingleby posted the letter that same night, staggering down the main road half a mile to a pillar box to do so. And now he must wait. It rained all next day, and only half a bottle of whisky remained. He held it up to the light.

"I must keep that," he muttered. "I shall probably need it... afterward."

AT 8 o'clock next morning Ingleby stood at the end of the track leading to his farm where it joined the main road. He waited a quarter of an hour before old Baines showed up. There he was at last, and he waved cheerfully to Ingleby as he got off his bicycle.

"Here's a letter for you, my lad," he said, and stood in the road holding it out.

Ingleby took it eagerly.

The plan was going well. Miss Wildshawe intimated that she would be at Adenham station at 4:30 on the following afternoon. It was some time since she had been in the country and she would much enjoy walking to his farm.

Ingleby smiled.

THE next day at 8 o'clock in the morning, Ingleby was once more at the junction of the main road and the track leading to Cripps Corner. He had in the meantime been busy. For this was the second part of the plan. This, in fact, was the masterpiece—as time would show, but it was a pity he was obliged to wait... and wait again. Waiting took it out of a man. His hands, pressed against the handle of a stout ash plant, were not as steady as they might be.

He looked, however, with complacency at his right foot. In place of the ordinary heavy boot he was accustomed to wear, it was covered with the remains of a felt slipper and a soiled bandage of large proportions, showing in parts a dull red.

Thus he stood leaning on the stick and gazing eagerly down the road. It was raining, a thin drizzle. The morning was raw. He shivered and pulled his overcoat closer about him. Where was old Baines? Wasn't he going to pass that morning of all mornings? It was essential that old Baines should pass.

There was not a sound except the quiet drip of water from the bare trees. Five or ten minutes passed and Ingleby felt his feet growing numb. He shifted his position slightly. Then, at last, he heard a sound on the wet road, and there was old Baines pedalling along in a clinging black government waterproof with a hood to it, the cape spread well over the handlebars.

"Nothing for you today, lad," he said.

Then his glance traveled to Ingleby's right foot.

"Eh. lad," he added, "what's come to you?"

He bent and inspected the blood-soaked bandage with concern.

"I've had an accident," said Ingleby. "I want you to take a message from me to the station."

"That looks bad to me." said the postman. "You ought to have a doctor."

Ingleby shook his head.

"I've no money for doctors." he said, "and I'm quite able lo look after myself. I've found a use at last for the old field dressing. It's a clean cut with the chopper. I hit my foot instead of the billet. But it will be some time before I can walk as far as the station. It's a bit of a job getting to the corner here."

Baines nodded solemnly, and the rain drops fell from the peak of his cap.

"Were you then wanting to go to the station?" he asked.

Ingleby nodded.

"I was to meet a young lady coming to see me on business this afternoon," he replied. "She will arrive by the 4:32. She has never been here before and I intended to meet her. Would you take a message from me to Tibetts, the station master?"

"What will I tell him?" demanded Baines.

"Tell him to look out for a young lady and tell her of my accident."

"What is she like?" asked Baines.

Ingleby hesitated a moment. He had never seen the face of Miss Wildshawe.

"A very ordinary young woman." he said, "name of Wildshawe. I will write it down for you."

He produced from his pocket an envelope and a stump of pencil, wrote down the name in block capitals and handed it to the postman.

"Ask Tibetts to tell her to come straight up. I will be waiting for her at the farm with tea."

"Wouldn't it be best for her to take a cab, or something?" suggested Baines.

Ingleby appeared to consider the suggestion a moment.

"Of course," he said, "if she wants to do so. But I don't suppose she will find one, and she will have to walk the last half mile. You could not get a cab down this filthy ditch of a road."

"Very well, lad," said Baines, preparing to mount his bicycle. "I will see that she gets your message. And you had better look after yourself, lad. Don't get that foot of yours poisoned."

"I shall he all right," said Ingleby.

"And see here, lad"—Baines hesitated a moment—"best go a bit steady on the whisky, if you don't mind my saying so."

"Don't you worry about that," replied Ingleby. "There isn't much more of it left."

INGLEBY, left to himself, turned his back on the main road and began walking down the track leading to Cripps Corner. He leaned heavily on his stick. The mud was deep and the rain persistent, which was bad for the chest. He coughed nearly all the way to the farm and soon grew tired of his hobbling gait. It was then that anyone watching him would have noted that for the last 200 yards he walked without any limp, his right foot seemingly as strong as his left.

On arriving at the farm, he sat down by the kitchen fire. Then he bent forward and removed the bandage, stretching his foot to the blaze, for it was cold with constriction. He turned it this way and that and smiled upon it indulgently. There was no cut or mark to be observed.

His last bottle of whisky stood on the table beside him. He drank a little and put the bottle down.

Suddenly he started in his chair.

"Gloves," he said aloud, for he had contracted the habit of talking to himself in his loneliness. "I must get a pair of gloves."

He got shakily to his feet. Was all his scheme to go awry? He pulled himself together and, standing by the table, did some hard thinking, He could not go into Adenham to buy gloves—not with a wounded foot. Besides, to buy gloves would be dangerous and in any case he hadn't any cash.... Nevertheless, gloves were important. Everyone wore gloves.

Suddenly he remembered. A smile stole over his face as he lumbered across the room and up the stairs to the attic. There he opened a ramshackle trunk and began to turn over the pile of musty clothes which it contained. Petticoats, bodices, old serge skirts—these he flung aside. But here it was at last—a small packet done up in faded paper. He tore it open. A pair of white cotton gloves, rather yellow, lay in his hand.

"I thought Ma had kept her wedding gloves," he muttered. "It's lucky she had large hands."

IT was almost dark. The rain had ceased about an hour before, but the clouds were low and it might start again at any moment. The woods dripped monotonously.

Ingleby stood in the shelter of a big bush some 200 yards from the turn leading to Cripps Corner. He had thought very carefully about his ambush, and had finally decided to wait near the main rood. The risk was slightly greater, though at this time of day, five in the afternoon, there was very little traffic. It was, however, better to wait there. Miss Wildshawe might miss the turning. You never could tell with women; they had no sense of locality. And that would not do at all.

Besides it would be better for her to be found not too near the house.

He waited for her perhaps half an hour. The train, he imagined, must be late, but that was nothing new. From time to time he peered out down the road, but soon he could see nothing. The gloom of the December day had fallen upon the land.

Had the woman missed her train? Or was she hiring a cab after all? Ingleby strained his ears. These dripping boughs got upon the nerves... drip... drip. No, by God, that was a footstep—a light step on the hard road.

Ingleby felt his mouth go dry. He fumbled in his pocket and produced the white cotton gloves. He slipped them on. His hands were trembling.

"Keep cool, you damn fool," he muttered. "Cool... cool... five hundred a year for life."

The footsteps were coming nearer. Ingleby drew back into the shadow of the holly bush. There at last she was... walking upon his side of the road. She was wearing a silk mackintosh and there was the outline of an umbrella over her head. But it was getting very dark. He could scarcely see her. She was almost abreast of him now.

Summoning up all his courage he called by her name.

"Olive," he called.

He had decided that the Christian name would better serve his turn. It sounded more intimate, reassuring. But his voice was strangely thin and weak.

"Olive." he called again.

The figure in the rood paused. Then Ingleby heard a little gasp of fear and the quick pattering of footsteps.

"Damn the women..." She was running away down the road. Ingleby sprang after her. It was darker every minute. He could scarcely see where he was going. But there—at long last—she was, almost in the ditch. In a flash Ingleby was upon her. Was it anger or the fumes of whisky? It was impossible to tell. An overwhelming passion of rage was shaking him. He had her now. She gave a cry, instantly stilled by his right hand. He felt her teeth close upon his forefinger, Then she kicked out, catching him a sharp blow on the shin as he swung her off her feet. He lurched sideways. There was a crash and crackle of boughs as he stumbled into the thicket. A holly branch scored his face. It was even darker here... dark... and what he had to do was dark. He shifted his hands to her throat. Her neck was warm under the thin stuff of the cotton gloves. His grip tightened. She had ceased to struggle now. She was lying still enough, limp in his arms. Dare he relax? Carefully he let go. The light body swayed against him and she fell in a heap at his feet. He bent down, feeling desperately till at last he had his hand on her heart. But his own was beating so fiercely that for a moment he could not tell whether she lived or not. With a violent effort he forced himself to be calm. Yes... that was better... not a movement... dead all right... dead as a doornail. He had felt men's hearts during the war. He knew what death was like.

"The letter." he muttered to himself, "where is the letter?" He felt about in the darkness. Was there nothing but this damned umbrella? Ingleby put a foot upon the umbrella and heard the ribs crack. He was cold and wet, and drops of moisture fell upon the back of his neck where he stooped. And yet, though shivering, he was on fire. Beads of sweat ran along his forehead and trickled into his eyes.

HAD she not even a handbag? Had she hidden the letter in her clothes? He began to feel again for it when his foot struck something. He fell on one knee and a faint crackle showed that he had broken something. Here was the bag at last. He retrieved it from under him. Then he pulled out the contents but could not see them in the darkness, There was a mirror broken by his knee. He could feel that. There were also a couple of envelopes, a powder puff, some loose money and a note-case. He thrust the lot into a side-pocket, then took the bag, stuck it into the woman's clothing, picked up the smashed umbrella and the still body, and carried them, grunting with the effort, as far as his strength would take him, into the wood. It was worse than he had anticipated but it would never do for her to be found too close to the road. Fortunately he knew every inch of the way. He could not get lost. So he staggered on until, quite spent, he let the body fall into a thicket beneath a clump of fir trees. There could be no better place. It might lie there for weeks.

Then he threw the umbrella into a bush nearby and, turning, made his way back to the farm.

INGLEBY looked round the kitchen. It was just as he had left it hardly two hours ago. But why should it be otherwise? Nothing much had happened. He had merely done what he had set out to do. He did not feel essentially different himself. He had committed a murder, but murderers were probably, a good many of them, much as other men. There were more of them than was ever suspected. Himself, for example. No one would ever know that he had murdered Olive Wildshawe. At least he felt that they wouldn't.

But there was still a good deal to be done—the most important thing of all, in fact, remained—the great idea which had sprung from the shadows and made all the rest of the plan feasible. He had asked himself before ever he had started whether he would have the nerve to do it. But that, of course, was evident. He had done worse things than that in the wood an hour ago.

He rose and walked to the corner of the room. There stood the chopper, a fair-sized chopper. The blade was clean and sharp. It gleamed at him reassuringly.

He picked it up and balanced it a moment in his hand.

Then, with sudden resolution, he put his foot upon the chopping block and struck himself a hard blow. The chopper cut through the flesh to the bone. The blood spurted and the pain for a moment was sickening. He found himself propped against the wall.

"Mustn't faint," he muttered.

The pain passed after a little, to be succeeded by dull throbbing. He felt very sick, but he staggered and hopped to the table where the bandages lay all ready. In great pain and difficulty he cut away the boot and the sock and wrapped the bandages round his foot. He would have preferred to have cut his foot with the hoot off, but that might have given him away.

Then he wiped the chopper clean and threw it back into the corner. He drew off the cotton gloves and flung them into the blaze.

HE was safe now, safe as a house. They could suspect what they liked but they could never prove it. Old Baines would testify. Old Haines had seen him with his foot in that identical bandage at 8 o'clock in the morning. Old Baines was to be trusted, This was the perfect murder. Five hundred a year for life. No more farming for him after this. He would go traveling somewhere in the warm South where there were sun and palm trees and no licensing hours. He would rest and enjoy some much-needed comfort.

But still there were things to do, things which might connect him with the murder, things sufficiently damning to throw doubt upon his alibi. There was that letter for example, with the bit about his lawyer friend and all those clever instructions which had lured the woman to her death. The police, with that letter in their hands, would soon put two and two together and have the rope round his throat in a brace of shakes.

He fumbled in his pocket. Something soft met his fingers—a powder-puff. Then came a mirror. He threw the puff into the fire. It blazed up and was reduced to ashes in a second. He would get rid of the mirror later. And now here, at last, was the letter. There were, in fact, two letters. Ingleby in his eagerness almost flung them into the fire. But his hand stopped short on the way to the flames and he found himself staring et the envelopes. He sat very still gaping at them for some time. Then he pressed a hand to his forehead. It was damp and his hand was shaking. He steadied himself as best he could.

Neither of the envelopes was the one he had addressed to Olive Wildshawe. Had she, after all, left the letter at home? And what was she doing with letters addressed to another woman? Who, in any case, was Mrs. Beacher, 110 Elm Grove, Haywards Heath?

WITH fingers that shook and trembled he opened the envelopes. They both contained bills... bills.... He knew a bill when he saw it—one from Messrs. Thursby, grocers, and the other from... yes, it was from old Burstard.

Ingleby sat by the fire. He could not think very clearly. Something had gone wrong. There was a letter somewhere and it was a letter that might hang him yet if he were not very careful.... Miss Wildshawe was dead, as he had every reason to know... and there was not even a drop of whisky in the house. Nothing stirred in the room except the logs on the hearth which were blazing fitfully. The little cracked mirror on the table beside Ingleby twinkled back at the flames, but Ingleby had completely forgotten the little mirror.

A knock sounded abruptly on the door. The shock pulled Ingleby together. He flung the two letters into the fire and watched them burn. Again there was a knock, and then another louder knock. A hand was fumbling at the latch. Old Baines stood in the doorway.

"There you are." said the old man smiling. "I have brought you a telegram. It will likely be from your young lady. She was not at the station."

Ingleby took the telegram and stared so straight and so long in front of him that old Baines was quite obviously alarmed.

"Aren't you going to read it, lad?" he asked.

"Of course," said Ingleby.

But his hands were trembling so much that he could not manage the orange-colored envelope.

"Here," offered Baines, "let me open it for you."

"There you are." said Baines handing him the flimsy paper.

"Read it, read it." said Ingleby nervously.

Old Baines bent down so that the light of the fire shone on the telegram. His beard as he leaned forward brushed the little mirror from the edge of the table. It fell with a light crash to the floor. Baines stooped to retrieve it.

"Leave that." said Ingleby harshly, and in a sudden passion he snatched the telegram from the hands of the old man.

"Sorry," he read, "caught touch of 'flu'. Will come some day next week if convenient. Wildshawe."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.