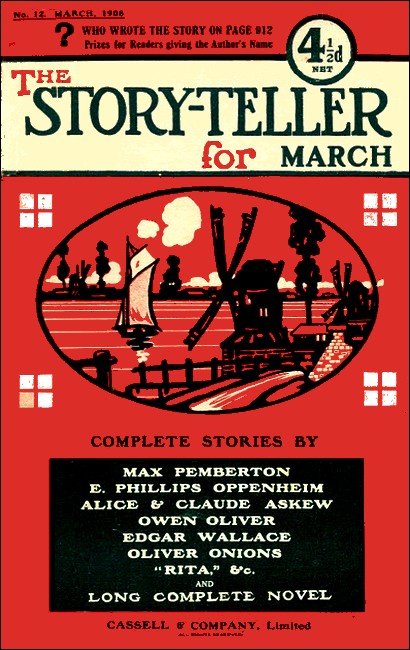

This story made its first appearance in The Story-Teller in March 1908, and was evidently syndicated. The version given here, for example, was found in the issue of The Timaru Herald, New Zealand, published on November 18, 1916. It was later reprinted under the title "The Monkey and the Box" in the 1984 collection The Sooper and Others.

The Story-Teller, March 1908, with "The Monkey and the Box"

WHEN Christopher Angle went to school he was very naturally called "Angel" by his fellows. When, in after life, he established a reputation for tact, geniality, and a remarkable equability, of temper, he became "Angel, Esquire," and, as Angel Esquire, he went through the greater portion of his adventurous life, so that on the coast and in the islands and in the wild lands that lie beyond the It'uri Forest, where Mr C. Angle is unknown, the remembrance of Angel, Esquire, is kept perennially green.

In what department of the Government he was before he took up a permanent suite of rooms at New Scotland Yard it is difficult to say. All that is known is that when the "scientific expedition" of Dr Kauffhaus penetrated to the head waters of the Kasakasa River, Angel Esquire, was in the neighbourhood shooting elephants. A native messenger en route to the nearest post, carrying a newly-ratified treaty, counter-signed by the native chief, can vouch for Angel's presence, because Angel's men fell upon him and beat him, and Angel took the newly-sealed letter and calmly tore it up.

When, too, yet another "scientific expedition," was engaged in making elaborate soundings in a neutral port in the Pacific, it was his steam launch that accidentally upset the boat of the men of science, and many invaluable instruments and drawings were irretrievably lost in the deeps of the rocky inlet. Following, however, upon some outrageous international incident, no less than the—but perhaps it would be wiser not to say—Angel was transferred bodily to Scotland Yard, undisguisedly a detective, and was placed in charge of the Colonial Department, which deals with all matters in those countries—British or otherwise—where the temperature rises above 103 degrees Fahrenheit. His record in this department was one of unabated success, and the interdepartmental criticism which was aroused by its creation and his appointment, have long since been silenced by the remarkable success that attended, amongst others, his investigations into the strange disappearance of the Corringham Mine, the discovery of the Third Slave, and his brilliant and memorable work in connection with the Croupier's Safe.

To Angel, Esquire, in the early spring came an official of the Criminal Investigation Department.

"Do you know Congoland at all, Angel?" he asked.

"Little bit of it," said Angel modestly.

"Well, here's a letter that the chief wants you to deal with—the writer is the daughter of an old friend, and he would like you to give the matter your personal attention."

Angel's insulting remark about corruption in the public service need not be placed on record.

The letter was written on notepaper of unusual thinness.

"A lady who has had or is having correspondence with somebody in a part of the world where the postage rate is high," he said to himself, and the first words of the letter confirmed this view:

"My husband, who has just returned from the Congo, where he has been on behalf of a Belgian firm to report on alluvial gold discoveries, has become so strange in his manner, and there are, moreover, such curious circumstances in connection with his conduct, that I am taking this course, knowing that as a friend of my dear father's you will not place any unkind construction upon it, and that you will help me to get at the bottom of this mystery."

The letter was evidently hurriedly written. There were words

crossed out and written in.

"Humph," said Angel; "rather a miserable little domestic drama. I trust I shall not be called in to investigate every family jar that occurs in the homes of the chief's friends."

But he wrote a polite little note to the lady on his "unofficial" paper, asking for an appointment and telling her that he had been asked to make the necessary enquires. The next morning he received a wire inviting him to go to Dulwich to the address that had appeared at the head of the note. Accordingly he started that afternoon, with the irritating sense that his time was being wasted.

Nine hundred and three Lordship Lane was a substantial-looking house, standing back from the road, and a trim maid opened the door to him, and ushered him into the drawing-room.

He was waiting impatiently for the lady, when the door was flung open and a man staggered in. He had an opened letter in his hand, and there was a look on his face that shocked Angel. It was the face of a soul in torment—drawn, haggard, and white.

"My God! my God!" he muttered: then he saw Angel, and straightened himself for a moment, for he started forward and seized the detective by the arm eagerly.

"You—you," he gasped, "are you from Liverpool? Have they sent you down to say it was a mistake?"

There was a rustle of a dress, and a girl came into the room. She was little more than a girl, but the traces of suffering that Angel saw had aged her. She came quickly to the side of the man and laid her hand on his arm.

"What is it—oh, what is it, Jack?" she entreated.

The man stepped back, shaking his head. "I'm sorry, ver' sorry," he said dully, and Angel noticed that he clipped his words. "I thought—I mistook this gentleman for someone else."

Angel explained his identity to the girl in a swift glance.

"This—this is a friend of mine," she faltered, "a friend of my father's," she went on hesitatingly, "who has called to see me."

"Sorry—sorry," he said stupidly. He stumbled to the door and went out, leaving it open. They heard him blundering up the stairs, and after a while a door slammed, and there came a faint "click" us he locked it.

"Oh, can you help me?" cried the girl in distress. "I am beside myself with anxiety."

"Please sit down, Mrs Farrow," said Angel hastily, but kindly. A woman on the verge of tears always alarmed him. Already he felt an unusual interest in the case. "Just tell me from the beginning."

"My husband is a metallurgist, and a year ago, he was commissioned by a Belgian company interested in gold-mining to go to the Congo and report on some property there."

"Had he ever been there before?"

"No; he had never been to Africa before. It was against my wish that he went at all, but the fee was so temptingly high, and the opportunities so great, that I yielded to his persuasion, and allowed him to go."

"How did he leave you?"

"As he had always been—bright, optimistic, and full of spirits. We were very happily married, Mr Angel—" she stopped, and her lips quivered.

"Yes, yes," said the alarmed detective; "please go on."

"He wrote by every mail, and even sent natives in their canoes hundreds of miles to connect with the mail steamers, and his letters were bright and full of particulars about the country and the people. Then, quite suddenly, they changed. From being the cheery, long letters they had been, they became almost notes, telling me just the bare facts of his movements. They worried me a little, because I thought it meant that he was ill, had fever, and did not want me to know."

"And had he?"

"No. A man who was with him said he was never once down with fever. Well, I cabled to him, but cabling to the Congo is a heart-breaking business, and there was fourteen days' delay on the wire."

"I know," said Angel sympathetically, "the land wire down to Brazzaville."

"Then, before my cable could reach him, I received a brief telegram from him saying he was coming home."

"Yes?"

"There was a weary month of waiting, and then he arrived. I went to Southampton to meet him."

"To Southampton, not to Liverpool?"

"To Southampton. He met me on the deck, and I shall never forget the look of agony in his eyes when he saw me. It struck me dumb. 'What is the matter, Jack?' I asked. 'Nothing,' he said, in, oh, such a listless, hopeless way. I could get nothing from him. Almost as soon as he got home he went to his room and locked the door."

"When was this?"

"A month ago."

"And what has happened since?"

"Nothing; except that he has got steadily more and more depressed, and—and—"

"Yes?" asked Angel.

"He gets letters—letters that he goes to the door to meet. Sometimes they make him worse, sometimes he gets almost cheerful after they arrive; but he had his worst bout after the arrival of the box."

"What box?"

"It came whilst I was dressing for dinner one night. All that afternoon he had been unusually restless, running down from his room at every ring of the bell. I caught a glance of it through his half-opened door."

"Do you not enter his room occasionally?"

She shook her head. "Nobody has been into his room since his return; he will not allow the servants in, and sweeps and tidies it himself."

"Well, and the box?"

"It was about eighteen inches high, and twelve inches square. It was of polished yellow wood."

"Did it remind you of anything?"

"Of an electric battery," she said slowly. "One of those big portable things that you can buy at an electrician's."

Angel thought deeply.

"And the letters—have you seen them?" he asked.

"Only once, when the postman overlooked a letter, and came back with it. I saw it for a moment only, because my husband came down immediately and took it from me."

"And the postmark?"

"It looked like Liverpool," she said.

He questioned her again on one or two aspects that interested him.

"I must see your husband's room," he said decisively.

She shook her head.

"I am afraid it will be impossible," she said.

"We shall see," said Angel cheerfully.

Then an unearthly chattering and screeching met their ears, and the girl turned pale.

"Oh, I had forgotten the most unpleasant thing—the monkey!" she said, and beckoned him from the room. He passed through the house to the garden at the back. Well sheltered from the road was a big iron cage, wherein sat a tiny Congo monkey, shivering in the chill spring air, and drawing about his hairy shoulders the torn half of a blanket.

"My husband brought one home with him," she said, "but it died. This is the fifth monkey we have had in a month, and he, poor beastie, does not look as if he were long for life."

The little animal fixed his bright eyes on Angel, and chattered dismally.

"They get ill, and my husband shoots them," the girl went on. "I wanted him to let a veterinary surgeon see the last one, but he would not."

"Curious," said Angel musingly, and, after making arrangements to call the next morning, he went back to his office in a puzzled frame of mind.

He duly reported to his chief the substance of his interview.

"It isn't drink, and it isn't drugs," he said. "To me it looks like sheer panic. If that man is not in mortal fear of somebody or something, I am very much mistaken."

The girl had given him some of the earlier letters she had received from Africa, and after dinner that night Angel sat down in his little flat in Jermyn Street to read them. In the first letter—it was dated Boma—occurred a passage that gave him pause. After telling how he had gone ashore at Flagstaff, and had made a little excursion up one of the rivers, the letter went on to say:

"Apparently, I have quite unwillingly given deep offence to one of the secret societies—if you can imagine a native secret society—by buying from a native a most interesting ju-ju or idol. The native, poor beggar, was found dead on the beach this morning; and although the official view is that he was bitten by a poisonous snake, I feel that his death had something to do with the selling of the idol, which, by the way, resembles nothing so much as a decrepit monkey...."

In his search through the letters he could find no other

reference to the incident, except in one of the last of the

longer epistles, where he found:

"...the canoe overturned, and we were struggling in the water. To my intense annoyance, amongst other personal effects lost was the coast ju-ju I wrote to you about. A missionary who lives close at hand said the current, not being strong about here, the idol is recoverable, and has promised to send a boy down first, and if he finds it to send it on to me. I have given him our address at home in case it turns up...."

"In case it turns up!" repeated Angel. "I wonder—"

He knew of these extraordinary societies. He knew, too, how strong a hold they had in the country that lay behind Flagstaff. These dreadful organisations were not to be lightly dismissed. Their power was indisputable.

"The question is, how far are they responsible for the present trouble," he said, discussing the affair with his chief the next morning, "how far the arm of the offended ju-ju can reach. If we were on the coast I should not be surprised to find our young friend dead in his bed any morning. But we are in England—and in Dulwich to boot!"

"The yellow box may explain everything," said his chief thoughtfully.

"And I mean to see it to-day," said Angel determinedly. He did not see it that day, for on his return to his office he found a telegram awaiting him from Mrs Farrow:

PLEASE COME AT ONCE. MY HUSBAND DISAPPEARED LAST NIGHT AND HAS NOT RETURNED. HE HAS TAKEN WITH HIM THE BOX AND THE MONKEY.

He was ringing at the door of the house within an hour after

receiving the telegram. Her eyes were red with weeping: and it

was a little time before she could speak. Then, brokenly, she

told the story of her husband's disappearance. It was after the

household had retired for the night she thought she heard a

vehicle draw up at the door. She was half asleep, but the sound

of voices roused her, and she got out of bed and looked through

the Venetian blinds. Her room faced the road, and she could see a

carriage drawn up opposite the gate. A man walking beside her

husband, who carried a box, which she recognised as the yellow

box, and in the strange man's arms she could discern, by the

light of the street lamp, a quivering bundle which proved to be

the monkey.

Before she could move or raise the window her husband entered the carriage, taking with him the monkey, and the other man jumped up by the side of the driver as the vehicle drove off, and, as he did, she saw his face. It was that of a negro.

Angel suppressed the exclamation that sprang to his lips as he heard this. It was evident that she had not attached any importance to the story of the ju-ju, and he did not wish to alarm her.

"Did he leave a message?"

She handed him a sheet of paper without replying. Only a few lines were scrawled on the sheet:—

"I am a moral coward, darling, and dare not tell you. If I come back, you will know why I have left you. If not, pray for me, and remember mo kindly. I have placed all my money to the credit of your hanking account."

The girl was crying quietly.

"Let me see his room," said Angel; and she conducted him to the little apartment that was half laboratory and half study. A truckle bed ran lengthways beneath, the window, and a heap of blackened ashes were piled up in the fireplace.

"Nothing has been touched," said the girl.

Gingerly, Angel lifted the curling ashes one by one.

"I've known burnt paper to..."—he was going to say "hang a man," but altered it to "be of great service."

There were one or two pieces that the fire had not burnt, and some on which the letters were still discernible. One of these he lifted and carried to the window.

"Hullo!" he muttered.

He could not find a complete sentence, but, as he read it: ... very bad ... monkey ... take you away ... your own fault....

There was a blotting pad upon the little table, and a square dust mark, where he surmised, the mysterious box stood. He lifted the pad; underneath were a number of strips of paper.

He glanced at them carelessly, then:

"What on earth?" he said.

Indelibly printed on the slips before him were a dozen red thumb prints.

He looked at them closely.

The thumb prints were of blood!

Then, in the midst of his mystification a light dawned on Angel, and he turned to the girl.

"Has you husband bought a methylated spirit lamp lately?" he asked.

She looked at him in astonishment.

"Why, yes," she said, "a fortnight ago he bought one."

"And has he been asking for needles?"

She almost gasped.

"Yes, yes, almost every day!"

Angel looked again at the charred paper and smiled.

"Of course, this may be serious," he said; "but really I think it isn't at all. If you will content your mind for a day, I will tell how serious it is; if you will extend your content for four days, I would almost undertake to promise to restore him to you."

He left her that afternoon in an agony of suspense, and three hours afterwards she received a telegram:

FOUND YOUR HUSBAND—EXPECT HIM HOME TO- MORROW.

To his chief Angel explained the mystery in three minutes.

"I thought the ju-ju had nothing to do with it," he said cheerfully. "The whole thing illustrates the folly of a man who had never been further from home than Wiesbaden penetrating God's primaeval forest. Farrow, on the Congo, surrounded on all sides by the disease, must needs be suddenly obsessed by the belief that he has sleeping-sickness. So home he comes, filled with dread forebodings, and visions of the madness that comes to the people, with trypanosomiasis. Buys microscopes—our yellow box—and jabs his finger day by day to examine his blood for microbes. As soon as I heard he had got the approved spirit lamp for sterilising purposes, I knew that. He corresponds with the Tropical Schools of Medicine in London and Liverpool, boring those poor people to death with his outrageous symptoms. Jabs his blood into monkeys, and when they die—of cold and bad feeding—fears the worst. So, at last, some wise doctor at the London School, after writing and telling him that he was an ass, that he couldn't be very bad, and that the monkey's death wasn't any sign—except of cruelty to animals—offers to take him into hospital for a few days and put him under observation. So along comes the hospital carriage, with their nigger porter, and away goes our foolish hypochondriac, with his monkey and his box of tricks. They are turning him out of hospital to-morrow."