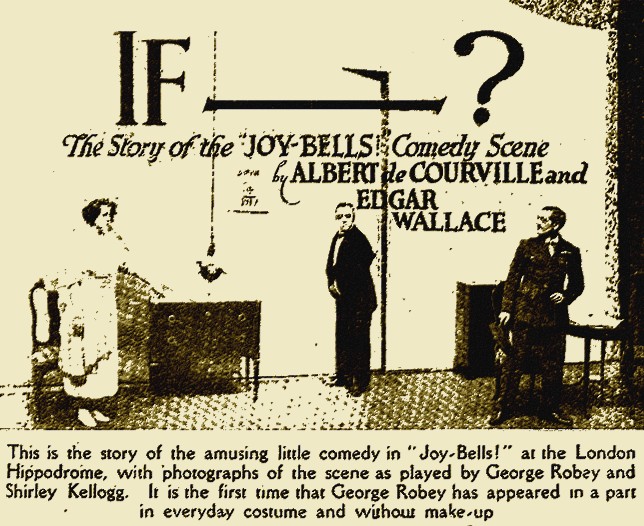

This short story is based on a comedy scene featured in the long-running musical review Joy Bells, which premiered at the Hippodrome Theatre in London on March 25, 1919. The review was written by Albert de Courville, Wal Pink and Thomas J. Gray, and the music was composed by Frederick Chapelle. It ran for a total of 723 performances.

THE war had soured Hector Smith. It had drawn a line between comparative youth and comparative middle-age. It had burst inconveniently, as wars have a habit of bursting, upon more than one half-matured scheme of his, and had scattered them to bits and left him the poorer. To be exact, it had left Mary the poorer, because it was Mary's money that went, of which fact it had become a habit of hers to remind him.

But more souring, bits of boys, the merest urchins, to be patronized or ignored in the old days, had obtruded themselves upon his and the public's attentions. The balance of life was over-set. The inconsiderable factors (in which category he included these boys who now strutted consciously be-ribboned through his world) had grown to such importance that they overshadowed the real big things of life, such as his handicap at golf, his bridge hands, the remarkable poverty of intelligence on the part of his partners, and the like.

There was a time when Arthur, for example, would have been carried to the seventh heaven by a timely half-sovereign, and would have run his long legs off in his haste to reach the confectioner's before the cream buns were sold. Now Arthur was a straight-limbed youth with "wings," and a record of good service in France.

And Arthur and Mary—

Pshaw! It was absurd! Why, he remembered this dirty little kid when he was so high! Yet, it was a fact that Mary spent most of her time with Arthur, raved about his dancing, his beautiful manners, his perfect sympathy. Pshaw!

Hector Smith cursed the war that forced him to listen to gruesome stories in which he was not interested.

He opened the drawing-room door and stalked in, then stopped with a little grimace. The inevitable Arthur was there, and the inevitable Arthur with an embarrassed giggle made his escape with a mumbled reference to the weather. As for Mary, she looked too good to be true.

"Hasn't that bird got a perch of his own?" snarled Hector.

"How can you speak of a man who has been wounded—?" began his indignant partner.

Mr. Smith laughed contemptuously.

"Wounded! The first time he tried to fly he crashed, and the second time he tried to fly he crashed, and the third time he tried to fly he crashed!"

She tossed her head.

"I'd like to see you do it!"

Mr. Smith shrugged.

"Oh, I know it's a mistake to talk disrespectfully of your hero," he sneered.

He was not feeling at his brightest.

"What do you mean?" she demanded with ominous calm.

"I mean, I'm fed up, that's what I mean," he snapped, and she flamed round on him.

"And so am I!" she cried. "You're vulgar and stupid and tyrannical. The life I've lived with you is abominable. When I married you I had money—"

He bowed.

"That's right," he said, encouragingly, "throw that in my face! Didn't I invest it for you?" It was an unfortunate question.

"Yes, you did," she said, bitterly. "You put it into a luminous sign business. Luminous signs! And a month after war was declared! And the only thing you could get out of showing a luminous sign was six months' imprisonment!"

"How did I know there was going to be a war?" asked the exasperated man.

"You might have guessed it," she replied, illogically.

"Could I guess that London was to be plunged in darkness? I did my best. I should have made a million out of that fuse factory I started this year—"

"Yes, if it hadn't been for the armistice," she scoffed.

"How did I know there was going to be peace?" he roared.

She flounced past him on her way to the door.

"Oh, you never know anything!"

"There's one thing I know," he shouted after her.

"What's that?"

"One of these fine days I'll run away to America!" Her scornful laugh came back through the slammed door. He threw himself upon the settee. The money was gone and the wife remained. That was his luck. If it had been the other way about—! If only it had been the other way about! If he could only live the years over again! If he could only be five years younger and knew what he knew!

He sat staring at the newspaper in his hand. There was a critique of a new play, a fairy play.

Bah! Fairies were nonsense!

He laid the newspaper down on his knees.

But suppose there were such things as fairies, and suppose they moved about this prosaic, industrialized world as in the old days they moved through the woodland glebes; suppose by a wave of a magic wand a man could be transplanted back, back, back; and suppose that it were possible that the clock should be put back, and one had consciousness of all the things that were going to happen, the horses that were going to win races, the stocks which were going to rise, all the great events which must occur!

He heaved a deep sigh and looked up. He half-rose from the couch, for there before him, a bright and radiant figure in the dusky room, stood a brilliant presence. He knew it was a fairy because it was dressed as fairies should be dressed, and bemuse she was bathed in a flood of silvery light which seemed to come from nowhere in particular. The little hands grasped a wand which twinkled and glittered with light.

Recovering from his initial astonishment he looked at her aappraisingly. He felt it would be undignified and ill-bred to regard her as a phenomenon.

"Hector Smith," said a sweet, low voice,

"I am your fairy godmother!"

"Oh, yes." said Hector Smith, politely.

"You have expressed a wish to be five years younger. Be happy, for to-morrow you will awake in 1914."

"Eh?" said Hector, sitting up. "I say, do you really mean that?"

She inclined her head.

"Wait a moment," said Hector, eagerly. "I must be the only one who knows it. D'ye understand? Because if everybody else knows it I shall be in the cart again."

She raised her wand and waved it slowly above his head.

"I must be the only one who knows that there's going to be a war and all that sort of thing," said Hector, drowsily. A sense of languor was rapidly overcoming him. "I don't want...."

His head fell on his chest.

He did not know how long he had slept when he awoke with a jerk. He had a confused dream in which figured fairies and brilliant wands, and low, sweet voices mingled, and then he remembered that he had to see Tomkins who was liquidating his ill-fated fuse factory. He went to the study and 'phoned Tomkins, but, amazingly enough, Tomkins was not on the 'phone. He asked Exchange to connect him with Smith's Patent Fuse Factory, but Exchange was ignorant that such a place had ever existed.

"The telephone service," said Hector Smith, as be hung up the receiver, "is becoming more and more abominable."

He decided to write to the newspapers on the subject. He paused outside the drawing-room door, for he heard his wife moving about inside, and it was necessary to brace himself up for the ordeal. He was a little scared of Mary in her tantrums, and more scared that his apprehension should be known to her. But the girl who came across the room to meet him had no frown, no reproaches. She was one beaming smile, and she ran towards him and laid her hands upon his shoulders.

"Dearie!" she kissed him, ecstatically: then noting the gloom in his face, "darling, whatever is the matter?"

"Matter?" he answered, suspiciously. "What's that you did? What's the matter with you?"

She looked at him in wonder.

"Nothing is the matter with me. I just kissed you, that's all."

He heaved a sigh. How did she know he had received his directors' cheque that day?

"How much do you want?" he asked, with resignation.

"Naughty boy, why do you say that?" she pouted. "Don't you love your diddlelums any more?"

He stared at her.

"Look here. What's up?" he asked, desperately. "I'll buy it! What's wrong with you?"

"Wrong?"

She was frankly astonished.

"Everything has gone wrong to-day," he growled. "I went to call up that fellow about the fuses—"

She frowned.

"Fuses? What are fuses?"

His suspicions returned. "Don't pull my leg," he said, coldly. "I'm not in a mood for it. Try it on the other fellow."

"What other-fellow?" He jerked his head to the door.

"He was heme just now. I heard his voice."

A smile of understanding dawned on her face.

"Who, little Arthur?"

"Yes, little Arthur," he snarled, "the little hero!"

"Don't be silly, Hector," she laughed.

"Arthur a hero!"

His rising wrath moderated. Evidently what he had said to her had done some good. Still suspicious, and with a horrid sense of unreality, he slipped his arm about her waist and led her to the couch. It was all unreal and unexpected, he thought, as her golden head rested on his shoulder.

"It's a. long time since we did this," he said. "It reminds me of the raid nights."

She straightened herself up.

"The what nights?"

"The raid nights."

She laughed. Hector in the full ardour of that period which was neither youth nor middle-age, had been a tempestuous lover.

"Dear, you use such queer expressions!"

"Do you remember the siren?" he asked, after a pause, and her head nodded vigorously.

"Yes, the cat—but I got you away from her."

"And how we used to go down into the cellar?" he mused. It seemed a thousand years ago. She straightened up. It was she who was suspicion.

"We never did," she protested. "Really, Hector! I hope you're not thinking of somebody else?"

Before he could answer Jane came in, and Jane, curiously enough, looked much younger.

"Will there be three to dinner, madam?" asked the maid.

Mary nodded.

"Who is the third?" demanded Mr. Smith.

"Oh, no one," said his wife, airily. "I asked Arthur to stay."

He sprang to his feet.

"Arthur! Confound the fellow, hasn't he gone? I won't have him. Do you understand. Marv. I-won't-have-him!"

Again the look of blank astonishment on her face.

"But why not?"

"He's such a nice little gentleman, sir," pleaded Jane. "He sat on my knee and told me such funny stories."

Hector glared from the maid to his wife.

"There you are!" he said, triumphantly. "That's the sort of fellow he is! Sits on her knee and tells her funny stories!"

To his amazement she laughed.

"It's not worth while getting angry—he can dine in the kitchen."

"In the kitchen!"

"Of course, he doesn't care," Mary went on, calmly, "so long as he goes to the White City."

"With whom?"

"Well, I'll take him," said Mary, indifferently. "I rather like the Roly-Poly and the Wiggle-Wag."

With a mighty effort Mr. Smith controlled himself.

"You can't go to the White City. It's been requisitioned by the Government four years ago," he said. "The White City is closed, I tell you. It's where the C3 men get their A1 gratuity—everybody knows that."

There was a strained silence, during which Jane tip-toed from the room.

Hector saw something in his wife's eyes that looked like fear, and failed to diagnose its cause.

"I'm sorry I lost my temper," he said, penitently; "the fact is I'm jealous."

The fear was replaced by a gleam of interest.

"Jealous? Of whom?"

He made a little gesture to cover his discomfort.

"Of you—and Arthur."

"But you're mad," she gasped; "at his age—"

"At his age." said Mr. Smith, icily, "I had been thrown out of the Empire twice."

He did not explain the degree of worldliness which this experience implied, but he left her to gather that it represented a particularly lurid form of precocity.

"I don't understand you to-night," she said, shaking her head.

"I don't understand myself," said Mr. Smith, rising. "I think I'll run down to the club, I promised to meet an ace."

"An ace? I thought you'd given up cards."

"You don't understand me—this fellow brought down thirty."

"Thirty what?"

"Boche."

"It isn't 'bosh'!" she exploded. "How did he bring them down?"

Hector groaned.

"He got on their tails and crashed them," he explained, patiently.

She was shocked.

"Poor things! I suppose they broke quite easily?" she asked.

He looked at her.

"I don't know what you are talking about," he said, irritably. "I am speaking about a fellow who has been 'mentioned' six times."

She shook her head.

"This is the first time you have mentioned him to me," she said; "what has he done?"

"Done? Why, in the early days before he started flipping, he took a pill-box all by himself!"

Her mouth opened.

"A whole box?" she gasped.

"You see," he explained, "he was in a tank, and when they went over the top—"

"Over the top of the tank?" she asked, hazily.

"No, the tank went over the top and a minnie dropped in front of him."

She was interested again.

"Poor girl," she said, sympathetically, "and did he help her up?"

"No; you see, a dying pig burst just behind him."

"But what did he do with Minnie?" she demanded.

She could not grapple with pigs that flew, but Minnie was someone tangible.

"Oh, she got him in the leg," he stated, carelessly.

She was grave now.

"I see, she wasn't a lady?"

"Of course she wasn't a lady," he wailed.

"I have told you it wasn't a lady! It was a minenwerfer."

She did not want to hear about Miss Werfer or even of a low person to whom he made glib reference—a Miss Emma Gee. This friend of her husband's seemed to have low tastes. He crashed people, he got on their tails.

"And Big Bertha—" Hector was saying when she stopped him.

"I don't think I want to meet your friend," she said, and made for the door.

He didn't understand her. Usually she was as full of the jargon of the war as the most ardent subaltern. Now she professed ignorance and demanded an elucidation of the most commonplace phrase.

He was pondering on this fact when the maid came into the room. She stood nervously waiting, and Hector guessed her errand.

"Well?" he growled.

"I-I thought I would ask you, sir," she faltered; "I was going to ask the mistress if-if she would give me a little rise."

"A rise again!" he groaned. This was the third or was it the fourth time...?

"But, sir?"

"Now listen to me," he said, severely, "I know that living is expensive, and coals are dear, and I am willing to give you another rise. But this must be the very last time. You can have five pounds a month, but not a penny more."

She did not swoon. She was too well-bred a servant.

"Five pounds a month! Oh, thank you, master, thank you! Oh, you are most good—"she grew incoherent.

Hector raised his eyebrows. He thought she was unusually grateful. His wife returned at that moment to hear his news.

"By the way, dear, I've just raised Jane's wages."

Usually she objected to his interfering in her domestic affairs, but now she was most amiable.

"I promised her I would—she seems a nice girl."

"Yes," said Hector. "I'm giving her five pounds a month."

His wife grasped a chair for support.

"Are you mad?" She beckoned Jane, for her earlier suspicions were now certainties.

"Fetch a doctor," she said, under her breath. "The master isn't well. I only pay her eighteen pounds a year."

She tried to say this in a light conversational tone, but her voice shook.

"You only—?" Something was very wrong, and he called the maid to him. "Ask Dr. Sawyer to step round. Mrs. Smith isn't quite herself," he said.

"Get Dr. Thomas." demanded Mary, sharply.

Thomas! Thomas was in Mesopotamia! It was clear now. The worry of the past years had turned her brain. It was a flattering explanation for the preference she had lately shown to Arthur. They watched one another apprehensively after the girl had gone, then:—

"Feel better, ducky?" he asked, huskily.

"Has that nasty wuzzy feeling gone, lovey?" her voice was a nervous squeak.

Dr. Thomas had the flat opposite, and Dr. Thomas was coming out of his flat when the frightened maid had literally flung herself upon him.

"They're both mad," she babbled, and the startled doctor followed her to where two people, each standing at the extreme end of a long drawing-room, were watching one another in silence. Hector saw him and uttered an exclamation of astonishment.

"By Jove. I thought you were in Bagdad?"

The doctor laid his soothing hand on the other's shoulder.

"Of course—Bagdadl Ah, that's the place—we'll soon put you right, old man."

Ignoring the implication that he wasn't right, Mr. Smith whispered something in the other's ear.

"Of course she is," replied Thomas, indulgently, and caught Mary's eye and Mary's significant signal.

It was at that moment that Arthur came in—Arthur in his Eton suit, with his cherubic face stained with jam. Hector looked at him and his jaw dropped.

"What the devil have you dressed like this for?" he demanded.

"Because I'm going to school, Mr. Smith."

"To school? How old are you?"

"Fourteen—nearly."

"Fourteen!" repeated Hector, hollowly.

"Is it possible—?"

On Mary's desk was a calendar and to this he walked.

"Nineteen fourteen! Mary, I understand all. I will explain. You're not mad—it was the fairy—who put back the clock!—my wish was granted!"

The doctor looked at Mary and Mary looked at the doctor. "I'm going to prophesy," Hector went on, excitedly. "We are going to war! The Kaiser will abdicate! The British Army will be seven millions strong! We shall win the war, thanks to Beatty, Haig, and Foch!"

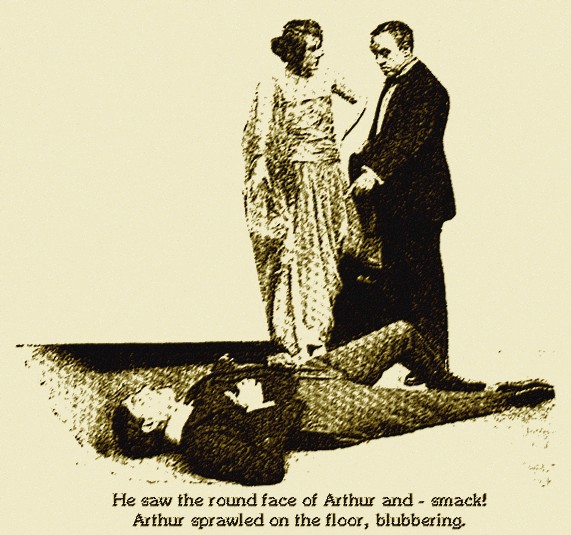

He saw the round face of Arthur and—smack! Arthur sprawled on the door, blubbering.

"Why did you do that?" asked the terrified Mary.

"He's going to cause me a lot of trouble," said Hector, prophetically