RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Woman from the East, Hutchinson & Co., London, 1934

"OVERTURE and beginners, please!"

The shrill voice of the call-boy wailed through the bare corridors of the Frivolity Theatre, and No. 7 dressing-room emptied with a rush. The stone stairs leading down to the stage level were immediately crowded with chattering chorus girls, arrayed in the fantastic costumes of the opening number.

Belle Straker lagged a little behind the crowd, for she had neither the heart nor the inclination to discuss the interminable nothings which were to fascinating to her sister artistes.

At the foot of the stairs a tired looking man in evening dress was waiting. Presently he saw the girl and raised his finger. She quickened her pace, for the stage manager was an irascible man and somewhat impatient.

"Miss Straker," he said, "you are excused tonight."

"Excused?" she replied in surprise. "I thought—"

The stage manager nodded.

"I didn't get your note saying you wanted to stay off," he said. "Now hurry up and change, my dear. You'll be in plenty of time."

In truth he had received a note asking permission to miss a performance, but he had not known then that the dinner engagement which Belle Straker was desirous of keeping was with the eminent Mr. Covent. And Mr. Covent was not only a name in the City, but he was also a director of the company owning the Frivolity Theatre.

The girl hesitated, one foot on the lower stair, and the stage manager eyed her curiously. He knew Mr. Covent slightly, and had been a little more than surprised that Mr. Covent was "that kind of man." One would hardly associate that white-haired and benevolent gentleman with dinner parties in which chorus girls figured.

As for the girl, some premonition of danger made her hesitate.

"I don't know whether I want to go," she said.

"Don't be silly," said the stage manager with a little smile. "Never miss a good dinner, Belle—how are those dancing lessons getting on?"

She knew what he meant, but it pleased her to pretend ignorance.

"Dancing lessons?" she said.

"Those you are giving to the Rajah of Butilata," said the stage manager. "What sort of a pupil does he make? It must be rather funny teaching a man to dance who cannot speak English."

She shrugged her shoulders in assumed indifference.

"He's not bad," she said, and turned quickly to run up the stairs.

The stage manager looked after her, and his smile broadened. Then, of a sudden, he became grave. It was no business of his, and he was hardened to queerer kinds of friendship than that which might exist between a chorus girl and an Eastern potentate, even though rumour had it that His Highness of Butilata was almost white.

Even friendships between young and pretty members of the chorus and staid and respectable City merchants were not outside the range of his experience. He too shrugged, and went back to the stage, for the strains of the overture were coming faintly through the swinging doors.

Belle Straker changed swiftly, wiped the make-up from her face, and got into her neat street clothes. She stopped on her way out of the theatre to inquire at the stage doorkeeper's office whether there had been any letters.

"No, miss," said the man. "But those two men came back again this evening to ask if you were playing. I told them that you were off."

She nodded gratefully. Those two men were, as she knew, solicitors' clerks who had writs to serve upon her. She had large and artistic tastes which outstripped her slender income. She was in debt everywhere, and nobody knew better than she how serious was her position.

The theatres were filling up, so that there were plenty of empty taxicabs and with a glance at the jewelled watch upon her wrist and a little exclamation of dismay, she gave directions and jumped into the first cab she could attract.

Five minutes later she was greeting an elderly man, who rose from a corner table in Penniali's Restaurant.

"I am so sorry, Mr. Covent. That stupid stage manager did not get my note asking to stay off, and I went to the theatre thinking my request had been refused. I hope I haven't kept you waiting?"

Mr. Covent beamed through his gold-rimmed spectacles.

"My dear child," he said pleasantly, "I have reached the age in life when a man is quite content to wait so long as he has an evening paper, and when time indeed runs too quickly."

He was a fine, handsome man of sixty-five, clean-shaven and rubicund. His white hair was brushed back from his forehead and fell in waves over his collar, and despite his years his frank blue eyes were as clear as a boy's.

"Sit down, sit down," he said. "I have ordered dinner, and I'm extremely grateful that I have not to eat it alone."

She found him, as she had found him before, a very pleasant companion, courteous, considerate and anecdotal. She knew very little about him, except that he had been introduced about two months before, and all that she knew was to his credit. He had invariably treated her with the deepest respect. He was by all accounts a very wealthy man—a millionaire, some said—and she knew, at any rate, that he was the senior partner of Covent Brothers, a firm of Indian bankers and merchants with extensive connections in the East.

They came at last to the stage when conversation was easier. And then it was that Mr. Covent opened up the subject which was nearer to his heart, perhaps, than to the girl's.

"Have you thought over my suggestion?" he asked. The girl made a little face.

"Oh yes, I've thought it over," she said. "I don't think I can do it, I really don't, Mr. Covent."

Mr. Covent smiled indulgently. In all the forty-five year in which he had been in business he had never approached so delicate or so vital a problem as this; but he was a man used to dealing with vital problems, and he was in no way dismayed by the first rebuff.

"I hope you will think this matter over well before you reject it," he said. "And I am afraid you will have to do your thinking tonight, because the Rajah is leaving for India next week."

"Next week!" she said in surprise, and with that sense of discomfort which comes to the opportunist who finds her chance slipping away before her eyes. "I thought he was staying for months yet."

John Covent shook his head.

"No, he's going back to his country almost immediately," he said. "Now, Miss Straker, I will speak plainly to you. I happen to know, through certain agencies with which I am associated, that you are heavily in debt, and that you have tastes which are—just a little beyond your means, shall I say? You love the good things of life—luxury, comfort and all that sort of thing; you hate sordid surroundings—er—landladies, shall I say?"

Belle shivered at the thought of an interview she had had that morning with "Ma" Hetheridge, who had demanded with violence, the payment of two months' arrears.

"Here is a man," John Covent went on, ticking off the points on his fingers, "who is madly in love with you. It is true that he is an Indian, though he would pass for an European and is admitted to the very best of English society. But against his colour and his race there is the fact that he is enormously wealthy, that he can give you not a house but a palace, a retinue of servants, and the most luxurious surroundings that it is humanly possible to imagine. He can give you a position beyond your wildest dreams and make you famous."

The girl shook her head, half in doubt, but did not reply.

"I know the kingdom of Butilata very well," mused Mr. Covent reminiscently. "A gorgeous country, with the most lovely gardens. I particularly remember the Ranee's garden—that would be you, of course, and the garden would be your own property. A place of marble terraces, of fragrant heliotrope, of luxurious growths of the most exotic plants. And then the Ranee's Court! That, of course, would he yours, Miss Straker—a columned apartment, every pillar worth a fortune. A Wonderful bathing pool in the centre, lined with blue tiles. And then, of course, you would have riding, and a car of your own—the Prince has half a dozen cars in his garage, and has just bought another half a dozen...and all the best people in India would call upon you. You would be received by the Viceroy...and all that sort of thing."

The girl fixed her troubled eyes upon the man, who sketched this alluring picture.

"But isn't it true," she said, "that Rajahs have more than one wife? What would be my position supposing he got tired of me and—"

"Oh, tut, tut! Nonsense!" said Mr. Covent, smiling benignly. "Don't forget that you are an English girl, and you would have special claims! No, no, the Government of India would not allow that sort of thing to happen, believe me."

She twisted the serviette with her nervous fingers. "When would he want—"

"The marriage ceremony should be performed tonight," said Mr. Covent. "It is a very simple ceremony, but of course quite binding."

"Tonight?" she said, looking at him in consternation, and Mr. Covent nodded.

"But couldn't I go out to India and marry there?"

"No, no," said John Covent. "That is impossible. Here is your opportunity to marry a man who is worth millions, occupying one of the most wonderful positions in India, tremendously popular with all classes—a man who loves you—don't forget that, my child, he loves you."

The girl laughed—a short, bitter laugh.

"I'm not worrying about that," she said. "The only thing that concerns me—is me."

"That I can well understand," said that grave man. "It is of course a very serious step in a girl's life, but few, I think, have been faced at such a crisis of their career with so pleasant a prospect."

He took from his pocket a note-case and opened it.

"It is a very curious position," he said. "Here am I, a very respectable old gentleman who should be in bed, engaged in a West End restaurant negotiating the marriage of an Indian Rajah."

He laughed pleasantly as he took from the case a pad of folded notes. The girl looked at the money with hungry eyes, and saw they were notes of high denomination.

"There is two thousand pounds here," he said slowly, "much more really than I can afford, although the Rajah is a great client of mine."

"What is it?" she asked.

"This was the wedding present that I was giving you," he said. "I thought of many presents which might be acceptable, but decided that after all perhaps you would prefer the money. Two thousand pounds!"

The girl drew a deep breath. Two thousand pounds!...and Butilata was not more unpleasant than the average young man. He had already treated her decently, and—

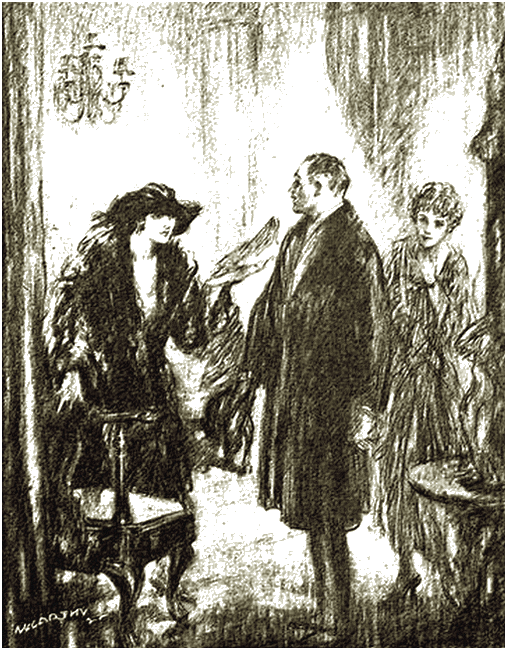

"All right," she said recklessly, and jerked on the squirrel cape which lay over the back of her chair, "Produce your Rajah!"

They left the restaurant together and drove in Mr. Covent's handsome little electric brougham to a big house off Eaton Square, and were instantly admitted by an Indian servant. She had been there before, but never so late. She expected to find the big saloon blazing with light, for here the Rajah loved to sit. She was surprised, however, to find only a small reading lamp placed by the side of the big blue divan on which he lolled.

He rose unsteadily to his feet and came towards her, both hands outstretched.

"So you have come," he said. He spoke perfect English, but there was a thickness in his speech and a glaze to his eye which suggested that he too had dined well.

He took her by both hands and led her to the divan, then turned to the waiting Englishman. The girl looked across almost appealingly to John Covent. Strange it was that in that dim light the mask of benevolence should slip from his face, and there should be something menacing, sinister in his mien. It was a trick of the light perhaps, for his voice was as soft and as kindly as ever.

"I think you're doing very wisely, Miss Straker," he said, "very wisely indeed."

Yet she seemed to detect a hint of nervousness in the voice, and for a second became panic-stricken.

"I don't think I'll go on with this, Mr. Covent," she said unsteadily. "I don't think I want to—go on with this."

"My dear child,"—his voice had a soothing quality—"don't be foolish."

The Rajah was looking down at them, for John Covent had seated himself on the divan by the girl's side, and on the Rajah's brown face was a little smile. Presently he clapped his hands.

"There shall be a ceremony," he said. "It shall be a small ceremony, my beautiful child."

A man appeared at the far end of the room in answer to his summons, and he fired a volley of sharp, guttural words at the attendant.

Half an hour later John Covent was rolling smoothly westward, leaning back in his car alone. A long cigar was between his white teeth and there was a smile in his eyes.

"Very satisfactory, very satisfactory," said John Covent.

Thus, on the 14th day of May, 1909, was Isabelle Straker, who, had she been married in a prosaic registry office, would have described herself as 'Spinster, aged 17½, married to His Highness Dal Likar Bahadur, Rajah of Butilata, by the custom of his land. She was his eighth wife—but this she did not know.

In the year of grace 1919 there were two partners to the firm of Covent Brothers. John Covent had died suddenly in India, and the business had passed into the hands of his son and his nephew, the latter of whom had inherited his mother's share in a business which had been in the same family for two hundred years.

Martin Covent was a tall, well-dressed man of twenty-seven. He had none of his late father's genial demeanour. The lips were harder, the brow straighter and the face longer than the expansive representative of the firm who had preceded him.

He sat at his great table, his elbows on the blotting-pad, and looked across towards his junior partner. And a greater contrast between himself and his cousin could not he imagined. Tom Camberley was two years his junior and looked younger. He had the complexion of a man who lived an open-door life, the eyes of one who found laughter easy. He was not laughing now. His forehead was creased into a little frown, and he was leaning back in his chair regarding Martin Covent through narrowed eyelids.

"I hate to say so, Martin," he said quietly, "but I must tell you that, in my judgment, your scheme is not quite straight."

Martin Covent laughed.

"My dear boy," he said, with a hint of patronage in his tone, "I am afraid the mysteries of the banking profession are still—mysteries to you."

"That may be so," returned Tom Camberley coolly. "But there are certain basic principles on which I can make no mistake. For example, I am never mystified in distinguishing between right and wrong."

Martin Covent rose.

"I have often thought," he said, with a hint of irritation in his voice, "that you're wasted on the Indian banking business, my dear Tom. You ought to be running the literary end of a Bible Mission. There's plenty of scope in India for you if your conscience will not permit you to soil your hands with sordid business affairs."

The other laughed quietly.

"You're always suggesting I should clear out of the firm, and I should love to oblige you. But, bad business man as I am, I know the advantage of holding a position which brings me in the greater part of ten thousand a year. Anyway, there's no sense in getting angry about it, Martin. I merely offer you an opinion that to employ clients' money for speculative purposes without having secured the permission of those clients is dishonest. And really, I don't know why you should do it. The firm is on a very sound basis. We are making big profits, and the prospect is in every way healthy."

The other did not immediately reply. He paced the big private office with his hands in his pockets, whistling softly. Suddenly he stopped in his stride and turned.

"Let me tell you something, Tom Camberley," he said, "and stick this in your mind. You think you're on a good thing in holding shares in Covent Brothers. So you are. But ten years ago this firm was on the verge of bankruptcy, and your shares would have been worth about twopence net."

Tons raised his eyebrows.

"You're joking," he said.

"I'm serious," said the other grimly. "We're talking as man to man and partner to partner, and I tell you that ten years ago we were as near bankruptcy as that." He snapped his fingers. "Fortunately the governor got hold or that fool Butilata. Butilata was rich; we were nearly broke. The governor took his finances in hand and rebuilt the firm."

"This is news to me," said Tom. "I was at school at the time."

"So was I, but the governor told me," said Martin. "It was touch and go whether Butilata put his affairs in the hands of Covent Brothers or not. Happily the governor was able to render him a service. Butilata was staying in this country, and when he wasn't drinking like a fish he was mad keen on dancing, and fell in love with a girl—an actress at one of the theatres here, who taught him a few steps. He married her—"

"Married?" said Tom incredulously. "Is the Ranee of Butilata an English girl?"

Martin nodded.

"It was the governor who brought it about. Clever old devil, God rest him! was the governor. Of course, he had his qualms about it. He often told me that he thought it wasn't playing the game. He knew the kind of life that she was going to; but after all, she was only a chorus girl, and probably she had a much better time than you or I."

Tom Camberley made a little face.

"That sounds rather horrible," he said. "What happened to the girl?"

Martin shrugged his shoulders.

"She survived it," he replied. "They were married and went out the next week to India. The governor never saw her again, though he frequently went to Butilata. When the rajah died she came to England. She doesn't suspect that we played the part we did, or we shouldn't have her account."

Tom shivered.

"It is not a nice story," he said. "I could wish that we had made our money in some other way."

"What do you mean?" asked Martin gruffly. "We didn't make it out of the girl. It is true that the governor put himself right with the Rajah over that business."

Tom laughed again, but this time there was a little note of hardness in his merriment.

"Butilata died a comparatively poor man though his wife seems to have plenty of money—probably she bagged the Butilata pearls—good luck to her, poor girl. But if the Rajah of Butilata became poor, the firm of Covent Brothers became correspondingly rich. Did your father oblige the Rajah in any other way?"

The other shot a suspicious glance at him.

"If you're being sarcastic you're wasting your breath. I merely want to point out to you that this business, which you regard as the safest investment you could find, was re-established by a fluke. Now be sensible, Tom." He came round the desk and sat on a corner, looking down at the other. "Here we have a prospect of making a million by the use of a little common sense. I tell you, Roumania is a country of the future, and these oil properties which have been offered to us will be worth a hundred per cent more than we can get them for today—and that in a year's time."

Still Tom Camberley shook his head.

"If you want to invest money, why not approach your clients?" he said. "We have no right whatever to touch their reserves or engage in any speculation which is not to the advantage of those who trust us with their balances. I notice too from the memo you sent me that you have earmarked the balance of this very woman—the Ranee. Surely you have done that woman sufficient injury!"

Martin Covent slipped down from the table with a snort.

"Anyone would think, to hear you speak," he said sarcastically, "that we were the Bank of England or one of the big Joint Stock concerns. Can't you get it in your head that we are bankers and merchants, and being bankers and merchants, we are necessarily speculators?"

"Speculate with your own money," said the other doggedly, and Martin Covent slammed out of the office.

His cousin sat deep in thought for five minutes, then he pushed a bell. A little while later the door opened and a girl came in. He noticed with surprise that she was wearing a coat and hat, and looked up at the clock.

"Gracious heavens!" he said in comical despair. "I hadn't the slightest idea it was so late, Miss Mead."

The girl laughed. Tom noticed that she had a pretty laugh, that her teeth were very white and very regular, and that when she laughed there were pleasant little wrinkles on each side of the big grey eyes. He had duly noted long before that her complexion was faultless, that her figure was slim, and that her carriage and walk were delightfully graceful. Now he noticed them all over again, and with a start realised that he had got into this habit of critical and appreciative examination.

The girl noticed, too, if the faint flush which came to her cheeks meant anything, and Tom Camberley rose awkwardly.

"I'm awfully sorry, Miss Mead," he said. "I won't keep you now that it is late."

"Is there anything I can do?" said the girl. "I have no particular engagement. Did you want me to type a letter?"

"Yes—no," said Tom, and cursed himself for his embarrassment. "The fact was, I wanted to see the Ranee of Butilata's account."

The girl smiled and shook her head.

"Miss Drew has the accounts, you know, Mr. Camberley. I only deal with the correspondence."

Tom Camberley did know. When he had pressed the bell he had had no plan in his mind, and was as far from any definite scheme now.

"Where does the Ranee live?" he asked.

"I can get that for you," said the girl, and disappeared, to return in a few minutes with a slip of paper.

"The Ranee of Butilata, Churley Grange, Newbury," she read.

"Do you know her?"

The girl shook her head.

"All her business is done by Miss Drew who goes down to see her," she said. "Miss Drew told me that she is always veiled—she thinks that there is some facial disfigurement. Isn't it rather dreadful an English girl marrying an Indian? Would you like to see Miss Drew in the morning?"

"No, no," he said hastily. He had no desire to discuss the matter with Miss Drew. Miss Drew had complete control of the accounts, and he suspected her of enjoying more of his partner's confidence than he did. To him she was a statuesque, cold-blooded plodder with a mathematical mind, who was never known to smile, and he was a little in awe of the admirable Miss Drew.

"Sit down," he said, and after a second's hesitation the girl obeyed.

Tom walked to the door and shut it—a proceeding which, if it aroused any apprehension in the girl's mind, did not provoke any objection.

"Miss Mead," he said, "I am going to take you into my confidence. In fact, I am going to ask you to do something just outside your duty, and I am relying upon you to keep the matter entirely to yourself."

She nodded, wondering what was coming next.

"The Ranee is not one of our richest clients," he said. "But she has a large deposit account with us, and she has frequently invested money on our advice in certain speculative propositions which have been put before her. My partner and I have a scheme for buying up a block of oil properties in Rumania, and he—Mr. Covent—has told me that her highness is willing to invest to any extent."

He was doing something which he knew was unpardonable. Not only was he suspecting his partner of a lie, but he was conveying his suspicion to an employee in the firm. In his doubt and uncertainty he had blundered into an act which had the appearance of being dishonourable; for he was now within an ace of revealing the secrets of partnership, which should not go outside.

He looked round apprehensively toward the door through which his partner had disappeared. He knew, however, that Martin was a creature of habit, and by now would be driving away in his car, and that there was no fear of interruption. The girl was waiting patiently. To say that she was not curious would be to mis-state her attitude. She had need of patience, for it was some time before he spoke; but when he did speak, his mind was made up.

"I want you to do me a favour," he said, "and undertake an unusual mission. Will you go down to Churley Grange to-night and see the Ranee?"

"To-night?" said the girl in surprise.

He nodded.

"I have told you that this business is confidential, and I don't think it is necessary to emphasize that fact. I want you to see her as from me, and ask her the amount she wishes to invest in Rumanian Oils. You can say we have mislaid her letters, and that I have sent you down before the office opens in the morning so that no mistake shall be made. If she expresses surprise, and cannot recollect having authorized us to invest money in Rumanian Oils, I want you to pretend that there is some mistake and that you were not quite certain whether she was the client concerned, and use your native wit to get out of the situation as well as you can. You quite understand?"

She nodded slowly.

"I understand a little," she smiled. "But wouldn't it be better to see Miss Drew in the morning? She deals with the Ranee."

Tom shook his head.

"No, no," he said. "I want you to get down, and I don't want Miss Drew to know anything about it, nor my partner."

He looked at his watch.

"The trains to Newbury are fairly frequent, I think," he said, "and at any rate we will look up the time-table."

There was a train down in an hour; the last train back reached Paddington at half past eleven.

"I will be waiting for you at the station with a car," he said. "Here is five pounds for expenses. Now will you do this for me?"

"Certainly, Mr. Camberley," said the girl, and then, with a smile in her eyes, "It sounds horribly mysterious, but I just love mystery."

"And I just hate it," said Tom Camberley.

Churley Grange was five miles from Newbury Station—a piece of information which Dora Mead received with mixed feelings. Fortunately there were taxis at the station, and Tom Camberley had given her sufficient money to meet any contingency.

It was dark when she turned from the main London road into a side road which bore round in the direction of Reading. Churley Grange was a Georgian mansion which stood on the main London road. It was a big house with very little land attached, and that enclosed by a high brick wall which hid the house from the road. A pair of big green gates, flanked by a smaller wicket gate, gave admission to the grounds, and these were closed when the cab drew up. Dora Mead looked for a bell, and for some time failed to find one. Then she discovered a small knob by the side of the wicket gate, and painted the same colour so as to be almost indistinguishable, and pressed it. She had to wait a few minutes before the gate was opened by a dark-looking man, evidently an Indian.

He wore a blue uniform coat with small metal buttons bearing some sort of crest. This she noticed in the brief time he stood surveying her.

"Is this the Ranee of Butilata's house?" she asked. The man nodded.

"I have some important business with her," said Dora.

"Have you an appointment?" demanded the gatekeeper. He pronounced his words so carefully that she knew for certain that he was not English, even if his swarthy countenance had not already betrayed the fact.

The girl hesitated.

"Yes," she said boldly.

"Where are you from?" asked the man.

She was about to say "London" but changed her mind.

"Newbury," she replied.

"Come in," said the man curtly and locked the door behind her.

She found herself in a beautiful garden and was conducted across a well-kept lawn to a flight of steps leading to the main door of the building. Here she was handed over to another servant, also a man, and, like the first, an Indian. The gateman said something to the other in a low voice, and the second servant led her through a wide hall into the drawing-room.

It might have been the drawing-room of a palace. It was certainly the home of one to whom money was no object. The room was illuminated by lights concealed in the cornices, the ceiling was beautifully carved in plaster in the Moorish style, and long blue silk curtains covered its three windows. The floor was of polished parquet, on which a number of costly rugs were spread, and one gorgeous screen of exquisite workmanship, which she judged to be Eastern, was so arranged that it hid a second door in one corner of the room.

She was admiring the taste and beauty of the furnishings, when she heard a rustle of garments behind her and half turned. Instantly there was a cry, a click and the room was in darkness.

The girl stepped back in alarm.

"Please don't be afraid," said a muffled voice. "The fuses have broken."

"I could believe that if I hadn't seen your hand turn the light out," said Dora, making an heroic attempt to keep her voice steady. "Are you the Ranee of—of Butilata?"

"That is my name," said the voice. "Wait, I will get candles."

The door opened and closed, and she heard voices in the hall. Then the mysterious hostess returned.

"Why have you come here and what do you want?" she asked.

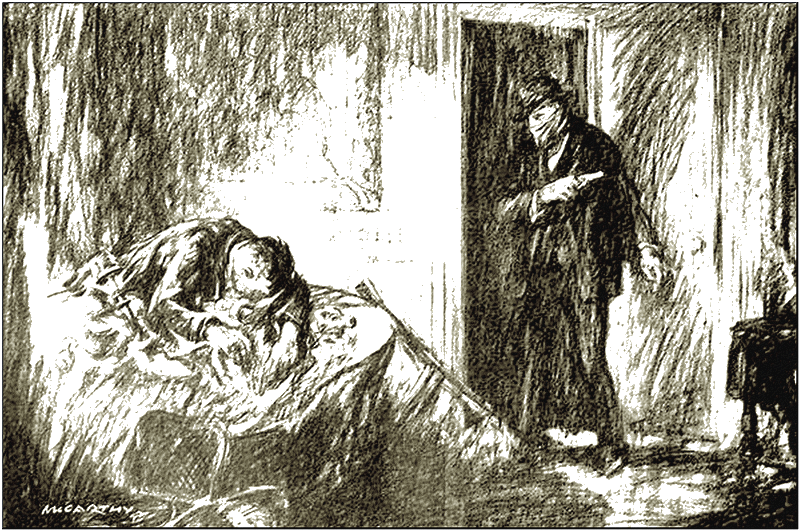

"I will discuss my business in the light," said Dora. She was shaking from head to foot, for there was something about this house and its gloomy servants which had struck a chill of terror to her soul—something now in the strange conduct of the mistress of the house which filled her with blind panic. She heard the creak of the door opening, but this time she did not see the dim light in the hall, and she knew that it had been purposely extinguished.

The hair at the nape of her neck began to rise, her scalp tingled with terror. Springing forward, she pushed the door aside and groped for the switch. Her fingers were on the lever, when a cloth was thrown over her head and she was jerked violently to the floor. She opened her mouth to scream, but a big hand covered it, and then she fainted.

Tom Camberley paced the arrival platform at Paddington in an uncomfortable frame of mind. He had cursed himself for sending the girl on such an errand and had consigned his partner, who had aroused these suspicions and doubts in his mind, to the devil and his habitation.

When the train drew in, a little of this discomfort vanished.

The girl was in a carriage at the rear of the train, and when he saw her at a distance, he quickened his step. It was not until he was half a dozen paces from her that he saw her face in the light of an overhead electric lamp.

"My God!" he said. "What has happened?"

She was as white as death and swayed when he took her arm so that she nearly fell.

"Take me home," she whispered.

His car was waiting in the station yard, and it was not until the girl was approaching her Bloomsbury lodgings that she could find her voice to tell him of the evening.

"When I recovered consciousness," she said, "I was in the cab. The driver told me that the gateman had brought me out and said that I had fainted, and that the lady thought I had better sit in the open air for a little while until I recovered."

"You don't remember what happened after you fainted?"

She shook her head.

"Oh, it was dreadful, dreadful! I never felt so afraid in my life," she whispered.

"Did you see the Ranee?"

"No, I did not see her. Please God, I will never see her again! She is a dreadful woman."

"But why, why?" asked the perplexed young man. "Why did she do this?" Then, remembering the girl's distress: "You don't know how sorry I am, Miss Mead, that I have exposed you to this outrage. I will see the Ranee myself and demand some explanation. I will—"

He remembered that he was not in a position to demand any explanation, and that it was more likely, if this matter was exposed, that he would be called upon to furnish some account of Dora Mead's mission to the Anglo-Indian Princess.

"Please don't speak about it," said the girl, laying her hand on his arm. "I want to forget it. I was terrified to death, of course, but now it is all over I am inclined to see the humorous side of it."

Her obvious distress belied this cheerful view, but Tom Camberley was silent.

"I don't understand it," said the girl, returning to the subject herself. "It was so amazingly unreal that I feel as if I have had a very bad dream. Here we are," she said suddenly, pointing to a house, and Tom leaned forward and tapped the window, bringing the car to a standstill.

The sidewalks of the street were deserted, and the girl shivered a little as she descended from the car.

"Do you mind waiting a little while," she begged, "while I open the door? My nerves have been upset by this business."

"Isn't your landlady up?" he asked, and she shook her head.

"This is a block of tiny flats," she said. "Mine is on the second floor."

Her hand was shaking so that he had to take the key and open the door for her.

"I insist upon coming up to your room at any rate," he said, "to see that you are all right. You can't imagine how sorry I am that you have had this unhappy experience."

She demurred at first to his suggestion that he should go upstairs with her, but presently agreed, and he followed her up two flights, until they came to the door of the little flat. Again he had to use the key for her.

"I'll wait here while you put your lights on," he said. "Lights are great comforters."

She went inside, and suddenly he heard an exclamation of surprise. Without waiting for an invitation he followed her in. She was in a small sitting-room and was staring helplessly from side to side, as well she might, because the room had evidently been ransacked. The floor was covered with a litter of papers which had evidently been thrown from a small pigeon-holed desk against the wall. The drawers were open and articles of attire were scattered about; pictures were hanging awry as though somebody had been searching behind them.

They looked at one another in silence.

"Somebody's been here," said Tom unnecessarily, then stooped to pick something from the floor. It was a small brass button, bearing on its face an engraved design.

Tom Camberley turned it over and over in his hand. "This crest seems familiar," he said and the girl took the button from his hand.

She looked from the button to her employer.

"It is the crest of the Ranee of Butilata," she said.

Dora was early at the office the next morning but there was one before her, a slim pretty girl of 26 who looked up under her level black eyebrows as Tom Camberley's secretary came into the office. She noted the girl's tired eyes and white face but made no comment until she had hung up her coat and hat, then waiting until Dora was seated at her desk she lit a cigarette and swung round in her swivel chair.

If Dora saw the movement she took no notice. Martin Covent's confidential stenographer could not by any stretch of imagination be described as her friend. At the same time she always felt that Grace Drew was not ill-disposed towards her and had she been in a less perturbed frame of mind she would have responded more quickly to this unaccustomed action on the part of her fellow worker.

"You went to the Ranee of Butilata's last night," said Grace quietly and Dora looked round startled.

"Yes," she confessed. "I did. How do you know?"

Miss Drew laughed, a quiet little laugh that might have meant anything or nothing.

"She's been through on the 'phone this morning apologising for her rudeness to you. Was she very rude by the way?"

Briefly the girl related what had happened to her on the previous night and Grace Drew listened with interest.

"She's a queer woman," she said when the other had finished. "A little mad, I think."

"Have you ever seen her?" asked Dora with interest.

Miss Drew shook her head.

"She is usually veiled or else speaks to me through a curtain," she said. "Mr. Martin thinks that there is some deformity of face."

Dora nodded.

"It was dreadful, wasn't it?" she said.

"What was dreadful?" asked Miss Drew puffing out a cloud of smoke and following its flight ceilingward.

"She was an English girl," said Dora, "and was trapped into a marriage with an Indian."

"Who told you that?" asked Miss Drew quickly, and Dora laughed.

"I don't know it for certain," she said. "I do know she married the Indian and somehow I have a feeling that she was trapped."

"I don't know that I should be sorry for her," said Miss Drew after a pause. "She has plenty of money."

"Money is not the only thing," said Dora quietly. "I think you've got rather a wrong view of things, Grace."

"Maybe I have," said the other turning to her work. "Anyway you'll have to explain to Mr. Covent why you went to Newbury last night. I shall have to tell him because it was a message to him."

Dora shrugged her shoulders.

"I don't know that I shall tell him anything," she said. "I simply went—" she hesitated, "on instructions."

"On instructions from Mr. Camberley, I presume!" said Grace without raising her eyes.

The girl made no reply.

Miss Drew opened a little ledger on her desk and ran through the pages with deft touch. It impressed Dora that she was doing this more or less mechanically and that her object was to gain time.

"The Ranee is coming up today," she said.

"To the office?"

Miss Drew nodded.

"She generally comes up once a month," she said. "Oh no, she never comes actually into the office but poor I have to go out and interview her in her car. Would you like to meet her?"

Dora shuddered.

"No thank you," she said promptly and Grace Drew laughed.

Tom Camberley and his partner arrived at the office almost simultaneously and Tom went straight to his room with no more than a brief nod to his secretary. Through the glass partition she saw him come out again after a few minutes, and go into his partner's room. Grace Drew was also watching, it seemed, for a little smile was playing about the corner of her mouth.

"I don't think there will be any need for me to make my report," she said without stopping her work, and her surmise was justified.

Tom Camberley walked into Martin's room and closed the door behind him.

"Hello," said Covent, "what's the trouble?"

Tom drew up a chair to the big desk and sat down.

"Martin'," he said, "I'm going to be perfectly frank with you."

"That's a failing of yours," replied the other with the suggestion of sarcasm.

"Last night," Tom went on ignoring the interruption, "I was worried about this Roumanian Oil deal of yours and particularly in reference to your scheme for applying clients' money."

"Are we going to have that all over again?" demanded Martin Covent wearily.

"Wait," said the other, "I haven't finished. I wasn't quite satisfied that you were playing the game with the Ranee of Butilata and I sent Miss Mead to Newbury—"

"The devil you did!" said Martin flushing angrily. "That's a pretty low game to play, Camberley."

"If you come to a question of ethics," said Tom, "I think the balance of righteousness is on my side. I tell you I sent Miss Mead to Newbury to interview the Ranee and she was most disgracefully treated."

Martin was on his feet, red and lowering.

"I don't care a damn what happened to Miss Mead," he said. "What I want to know is what do you mean by sending a servant of the firm to spy on me and give me away. You must have taken the girl Mead into your confidence or she would not have known what inquiries to make. The most disgraceful thing I've ever heard!"

"I daresay you'll hear worse," replied Tom coolly. "But that also is beside the question. I want to see the Ranee's account."

Neither man heard the gentle tap at the door nor saw it open to admit Grace Drew.

"You want to see the Ranee's account do you?" snarled Martin, "Well, it's open to you any time you want. And I guess you'd better see all the accounts, Camberley, because I'm not going to carry on this business on the present basis much longer."

"In other words you would like to dissolve the partnership," said Tom quietly.

"I should," was the emphatic reply and Tom nodded.

"Very well, then," he said. "We can't do much better than call in a chartered accountant to straighten things out and see where we stand. I am not going to be a party to these queer business methods of yours."

"What do you mean by queer business methods?"

"You told me yesterday," said Tom, "that the firm was built up on the suffering you brought to an innocent girt. You boasted of the fact that the firm of Covent Brothers took up slavery as a side-line."

"Innocent!" laughed the other harshly. "A chorus girl!"

"So far as you and I know, that girl was as straight and as pure as any," said Tom sternly, "but if she were the worst woman in the world I should still regard the transaction as beastly."

"Remember you are talking about my father," stormed Martin.

"I am talking about the firm of Covent Brothers," said Tom Camberley, "and I repeat that you have done enough harm to this unfortunate woman without risking her money in your wildcat schemes."

Martin Covent was pacing the room in a fury and now he turned suddenly and for the first time saw Miss Drew standing by the door. There were few secrets which he did not share with this girl and possibly her presence was an incentive to his fury.

"I tell you, Camberley," he said, "that you have gone far enough. This woman—this Ranee—was business. I don't care a curse whether she was happy or unhappy—she saved the firm from going to pot. And I tell you too that if the same opportunity occurred to me as occurred to my father and I could save the firm by sacrificing a thousand chorus girls I should do so!"

Tom Camberley shrugged his shoulders and amusement and disgust were blended in his face.

"That is your code, Covent," he said, "but it is not mine and the sooner you bring in your chartered accountants the better."

Turning he left the room. There was a silence which the girl broke.

"I don't think so," she said.

"Don't think what?" asked Covent in a surprisingly mild tone.

"I don't think we'll call in the chartered accountants," said the girl coolly and helped herself to a cigarette from the open silver box.

He stared gloomily through the window and followed the girl's example lighting his cigarette from the glowing end of hers.

"If this had only happened in three months' time," he said, "when Roumanian Oils—"

She laughed.

"Roumanian Oils will have to bounce to get you out of your trouble, Martin," she said.

He sat at his desk, looking up at her from under his lowered brows.

"You know a great deal about the business of this firm," he said.

"I know enough to make it extremely unpleasant for you if you do not keep your promise to me," said the girl. "I know that you have been raiding your clients' accounts and that the last person in the world you want to see in this office is a representative from a firm of chartered accountants."

"The firm is solvent," he growled.

She nodded.

"It may be solvent, and yet it would be very awkward if the accounts were examined."

She puffed a ring of smoke into the air, a trick of hers, and then asked:

"Why not offer Mr. Camberley a lump sum to get out?"

"What good would that do?" he asked.

"It would save an examination of the accounts," she repeated patiently, "and I rather fancy Mr. Camberley would accept if the sum were big enough. At any rate, you cannot push him off until the half-yearly audit."

"That's an idea," he said thoughtfully. "If the worst came to the worst, I know a pretty little villa in an Argentine town and a pretty little girl—" he reached out his hand for hers and caught it, but she made no response.

"I think there's an idea in what you say," he went on. "At any rate, I'll see Camberley and try to get him out for a fixed sum—I can raise the money."

"I wonder," said the girl.

"You wonder what?" he asked quickly.

"Oh I wasn't thinking about the money but I was wondering whether you meant what you said, that you would sacrifice any woman for the firm's interest?"

"Any woman but you, darling," he said and, rising, kissed her. "Now, be a good girl and help me all you can. Some day you shall be Mrs. Covent, and who knows, Lady Covent?"

"Some day," she repeated.

Tom Camberley went back to his office and rang for Dora Mead.

"I'm leaving the firm," he said.

"Have you quarrelled?" she asked anxiously.

"Yes, I've quarrelled all right," said Tom grimly.

"Did he say anything about—?"

He shook his head.

"No, I didn't go very deeply into the question of your unfortunate adventure at Newbury," he said, "and I am as much in the dark today as I was last night. Why on earth did the Ranee treat you so badly?"

He followed the new train of thought musingly.

"I've been wondering too," said the girl. "I was telling Grace Drew and she said that the Ranee was a little mad."

Tom nodded.

"There's something in that, but it isn't a nice thought that the firm has a lunatic for a client."

He laughed.

"However, I shan't be a member of the firm much longer," he said.

He dictated some letters, but he was not in a good mood for business and the rest of the morning was idled away in speculation. Once he walked to the window and looking down into the busy street, saw a car drawn up before the main door. It was a beautiful car and from the angle at which he surveyed it, he saw that the windows were heavily curtained. He was wondering who the owner was when Dora came quickly into the office.

"The Ranee is here," she said, "I wonder if she has come to complain—"

"The Ranee," he repeated quickly, "I should like to see that lady."

He put on his hat, walked out of his office and down the broad stairs to the main entrance. As he reached the pavement the car was moving away. Miss Drew, bare-headed was nodding her farewell to the occupant. Tom had a glimpse of a slight figure in black behind the curtain and then a hand came out to pull up the window. It was a curious hand and Tom looking at it gasped.

He turned to Miss Drew.

"That was the Ranee, Mr. Camberley. Have you ever seen her?" said the girl pleasantly.

"The Ranee, eh?" said Tom. "No, I have never seen her. I thought she was a young woman?"

"I think she is," said Miss Drew. "She is rather a trying woman. But what makes you think she is not young?"

"I saw her hand," said Tom, "and if that was the hand of a young English woman then I am a Dutchman."

The girl raised her eyebrows.

"I've never noticed her hands," she said. "What was curious about it?"

Tom did not reply immediately.

"Have you ever seen a native's fingernails?" he asked.

"I don't remember," said the girl.

"Well, have a good look at the next native's you see. You will find a blue half-moon on each nail and there was a blue half-moon on the nails of the hand that came to the window. I know that the girl who married the Rajah of Butilata has lived in India for some years but I'll swear that she had not lived there long enough to display that characteristic of the native."

He left the girl standing in the street looking after the disappearing car.

Many things happened in the next six hours to make the day an eventful one for Tom Camberley. He received from his partner a formal offer of a very handsome sum on condition that the partnership was terminated then and there. At first he was for refusing this and then, acting on impulse he took a sheet of paper, wrote an acceptance and sent it by hand to Martin Covent's office. He was impatient to be done with the business. There was something unwholesome in it all. A formal audit of the books would take weeks and those would be weeks charged with impatience and annoyance. And the sum was a large one, larger in fact than he expected to get as his share. He walked into Dora office and found her alone.

"Miss Mead," he said, "I'm going to make a suggestion to you and I wonder if you'll be offended."

She laughed up at him.

"I shall be very much offended if you ask me to go to Newbury again," she said.

"Nothing so interesting as that." said he. "I was going to suggest that you came and dined with me tonight," and then at her quick glance of distrust (or was it merely embarrassment?) he added quickly "I should hate you to bring a chaperone but if you like you can. I want to tell you something of what has happened today. I am leaving the firm."

"Leaving the firm?" she said in such frank dismay that a pleasant little glow went through him. "Oh no, Mr. Camberley, you don't mean that!"

"I'll tell you all about it. Will you dine with me?"

She nodded.

They dined modestly and well at the Trocadero and Tom told all that had happened that day.

"Curiously enough," he said, "the dissolution of our partnership is less interesting to me than my discovery this morning."

"Your discovery?"

He nodded.

"You remember I went dawn to the street intending to have a word with the Ranee of Butilata. The car was just moving off as I arrived and I could only catch a glimpse of the lady inside. But just as the window came abreast of me I saw a hand come out to grip the strap which raised the window. And it was not the hand of a refined English woman or even of a woman who was not refined."

"What do you mean?" asked the girl.

"It was the hand of a native," said Tom emphatically, "and I should say a native of between 40 and 50. The hands were gnarled and veined and very distinctly I saw upon the finger-nails the little blue half-moon which betrays the Easterner."

"But I thought the Ranee was—"

"An English girl?" nodded Tom. "Yes. I thought so too. Now I've got an idea that there's some queer work going on and that the so-called Ranee of Butilata is not the Ranee at all."

"What is your theory?" she asked curiously.

"My theory," said Tom, "is that the Ranee of Butilata is not in England. She is probably dead, Somebody is impersonating her for his or her own purpose. This afternoon I got her account and it is a curious one. She arrived in England two years ago and opened an account with us for six thousand pounds. I have very carefully checked the incoming and out-going money and it is clear to me that six thousand pounds was expended on the house at Newbury and its furnishing. In fact, the lady only had a balance of a few pounds when, after the account had been opened some six months, the second payment was made to her credit. Since then, however, she has been receiving money from India pretty regularly and has now a very respectable balance."

"But it's impossible that she can be anything but English," said Dora shaking her head. "Miss Drew has often told me she has spoken to her and that her English is perfect."

"But she has never seen her face?"

"No," said the girl, after a moment's thought, "I believe the Ranee is always veiled."

"You are sure she always spoke good English," insisted Tom with a puzzled frown. "I wish I could speak to Miss Drew."

"Why not call on her?" asked the girl. "She has a little flat in Southampton Street."

Tom looked at his watch.

"Nine o'clock," he said. "I doubt whether she would be home."

"She always spends her evenings at home," said Dora. "She has often told me how dull she found time in London. I think she is studying accountancy in her spare time."

Tom hesitated.

"Do you know the address?"

"Yes," said the girl. "Kings Croft Mansions, No. 123."

"We'll go," said Tom, and called the waiter.

They took a taxi to Kings Croft Mansions and found that they were a big block of very small flats obviously occupied by professional people. No. 123 was on the fifth floor but happily there was a lift. There were in fact two lifts as the lift-man explained when they asked if Miss Drew was in.

"I don't know sir," he replied. "Sometimes she comes up this way and sometimes through the other entrance, and it's very difficult to know whether she is in or out. She hasn't been up this way for a long time."

They rang the bell at 123 and there was no response. Tom knocked but there was no reply. Accidentally he pushed the flap of the letter-box and uttered an exclamation.

"Why, the box is full of letters!" he said. "She has either a big correspondence or else she hasn't been here for days."

The mat beneath his feet felt uneven and he pulled it up. There were three on four newspapers all the same but of different dates and he took them out.

"Five days' newspapers," he said thoughtfully. "That's queer."

He went along the passage to the other lift.

"No sir," said the liftman, "I haven't seen Miss Drew for several days. She hasn't been home and sometimes she's away for weeks at a time. In fact, sir," he said, "Miss Drew very seldom stays here."

Then, realizing that he was betraying the confidence of one of the tenants of the house, he added hastily:

"She's got a little cottage down in Kent, sir, and I suppose she spends her time there in the pleasant weather."

Tom parted from the girl and went home that night more puzzled than ever.

The night for him was a sleepless one. He was up at five in the morning working in his study and at seven o'clock was in the street. The mystery of Miss Drew was almost as great as the mystery of the Ranee of Butilata. The solution baffled him and he had thought of a dozen without finding one which was convincing. His feet strayed in the direction of Southampton Street and he was within sight of the building when a mud-stained motor-car passed him like a flash and pulled up before the flats. The door opened and a girl jumped out. There was no need to ask who she was. It was Grace Drew. She wore a long black travelling cloak and her face was veiled but he knew her.

She turned to the driver of the car and said something. Without another word the car moved on.

"Excuse me."

Grace Drew was in the hall when Camberley's hand fell on her arm. She turned with a little cry.

"Mr. Camberley," she stammered.

"I'm sorry to bother you at this hour of the morning," said Tom good-humouredly, "but I called to see you last night."

"I wasn't in, of course," she said hurriedly. "I've got a little cottage down in Kent. One of my friends there was sending this car up to town and suggested that I should use it."

"You're a lucky girl to have such friends," said Tom. He could see through the veil that the girl's face was white.

"Perhaps I'd better postpone my inquiries," he said, "until later in the day."

"Thank you," she replied.

He was turning away, lifting his hat, when she came after him.

"Mr. Camberley," she said, "I've no doubt you think it is very extraordinary that I should drive to this place in a motor-car."

She spoke quickly and he could sense her agitation.

"I suppose you think also that this dress," she threw aside the beautiful cloak she was wearing and revealed a costume which even to his inexperienced eye must have cost more than a month's salary, "and all that sort of thing. But perhaps you know...I wanted to keep it a secret...Mr. Covent and I are going to be married."

"I'm awfully glad," said Tom awkwardly, and felt a fool. Though he had stumbled upon an affaire of his partner and the mystery, so far as Miss Drew was concerned, was a mystery no more.

"You won't say a word will you—not for a day or two," she said.

"I will not say a word even in a year or two," smiled Tom and held out his hand. "I congratulate you, or shall I say I congratulate Covent."

He heard her laugh, a queer little laugh he thought.

"Wait and see," she said mockingly and ran up the stairs towards the lift.

He had promised secrecy but there was one person that he had to tell and that for an excellent reason. If he had felt embarrassed at the interview in the morning, he felt more embarrassed that afternoon as he strolled with Dora Mead through Green Park. It was a glorious sunny Saturday and the park was filled with people, but for all he knew or saw there was only one other but himself, and that the flushed girl who walked by his side.

"You see," he was saying, "we have an excellent precedent. I am going to start another business. Covent has been very prompt and sent me his cheque today and I have finished with the firm—and I want somebody with me, to work with me, somebody who will put my interests first."

He felt he was growing incoherent, and the girl who was surprisingly cool, for all the fluttering at her heart, nodded gravely.

"So you see, dear," said Tom more awkwardly than ever, "the least you can do is to marry me right away."

"Isn't this—" she faltered, "a little quick?"

"Sudden is the word you wanted," he murmured, and they both laughed.

If the next few days were dream days for the two people who had lately been members of the firm of Covent Brothers they were hectic days for Martin Covent. Something had happened to the market. A rumour of trouble in Persia had changed the government in Roumania, shares had wobbled and collapsed and even gilded securities had lost some of their auriferous splendour.

One morning Martin Covent went the round of his bank, and methodically and carefully collected large sums or money, and these had been changed in an American bank in Lombard Street into even more realisable security. In the afternoon he called Miss Drew into his private office and locked the door.

"Agnes, my dear," the said flippantly though his voice shook, "you may pack your bag and get ready for a quick move to Italy."

"What has happened?" she asked.

"I am catching the Italian mail from Genoa to Valparaiso. All the passports are in order—"

"So it has come to that, has it?" she asked, biting her lips thoughtfully.

"It has come to that," he repeated.

"And we are to be married when?" she asked.

He shrugged his shoulders'

"My dear girl, we shall have to postpone the marriage for a little while, there is no time now."

"You expect me to go with you—unmarried?" she asked.

He took her by the shoulders and smiled down into her face.

"Can't you trust me?" he asked.

"Oh yes, I can trust you," she replied and there was no tremor in her voice. "What train do we catch?"

"The train leaving Waterloo and connecting with the Havre boat," said he. "Will you meet me on the platform at nine?"

She nodded.

"What of your clients?" she said.

He laughed.

"I'm afraid we'll have to take liberties with their accounts. The unfortunate Ranee of Butilata is going to suffer another injustice at the hands of the firm," he chuckled.

"But suppose it is found out that you have bolted," said the girl.

"How can it be? It is Friday today, I am never at the office on Saturday, by Sunday I shall be on the boat and it will be difficult for even the most skilful firm of accountants to discover that the firm has gone bust, for a week. No, my dear, I've thought it out very carefully. You will meet me tonight at nine o'clock?"

She nodded and went back to her work, as though the firm of Covent Brothers stood still high in the stable traditions of the City.

It was all so very simple. The plans went so smoothly that it was a very high-spirited Martin Covent who stepped into the boat-train as it was moving and sat down by the girl's side. They were the only occupants of the compartment.

"Well, darling," he said exuberantly, "we're off at last. You're looking pale."

"Am I?" she said indifferently. "If I am, is it extraordinary?"

He laughed and took out of his inside pocket a bulky black leather portfolio.

"Feel the weight of that," he said putting it into her hand. "There's happiness and comfort for all the days of our lives, Agnes."

She took the portfolio and put it down between them.

"And a great deal of unhappiness for other people," she said. "What about the Ranee of Butilata. She will be ruined."

"That doesn't worry me a great deal," smiled the man. "People of that kind can always get money."

She took a little silver cigarette-case from her bag, opened it and chose a cigarette.

"Give me one," he asked and she obeyed. She struck a match and held it for him, then lit her own, and slipping away from the arm which sought to hold her, she took a place facing him on the opposite seat.

"Now you're to be good for a little while," she said, "You've got to keep your head clear."

He puffed away at the cigarette and she watched him.

"After all," he said, "the firm is fairly solvent. We have a lot of outstanding debts and I suppose they'll call in Tom Camberley to straighten out the mess. I'm only taking my own money."

"That's a comforting way of looking at it," said the girl "It seems to me that you've taken some of your customers' money too."

"And that doesn't worry me either. Now, my dear, the object of life is to find as much happiness as one can and—"

He took the cigarette out of his mouth and looked at it.

"What weird stuff you smoke, Grace," he said.

"Get up!" Her voice was sharp and peremptory and in his surprise he attempted to obey her, but his legs would not support him and it seemed that no muscle of his body was under control.

"What the devil is this?" he asked stupidly.

"Dracena," she said coolly. "You have never heard of Dracena. That is because you have never been to India."

"Dracena?" he repeated.

"It is a very simple drug. It paralyses the muscles and renders its victim helpless. In a quarter of an hour you will sink into a condition of insensibility."

She spoke in such a matter of fact tone that he could hardly grasp the import of her words.

"This train will stop at a little wayside station," she went on. "You would not think it was possible to stop a boat express but I have fixed it. One of my servants, the one who used to masquerade as the Ranee of Butilata, has arranged to board the train at that station and I have arranged to get out. My car will be waiting and I hope to be back at Newbury in the early hours of the morning."

"At Newbury?" he gasped. "Then you—you—"

"I am the Ranee of Butilata," said the girl. "I am the woman your father sold into captivity, into a life which by every standard and by every test was hell! I was sold to a drunkard and a brute and an Indian at that, to save the firm of Covent Brothers and when my husband died I had to steal the money to bring me to England.

"I did not waste my time as the wife of Butilata," she went on quietly, but with a hardness in her voice which brought a twinge of terror to the paralysed man. "I learnt bookkeeping because I thought one day I would come back to the firm of Covent Brothers and worm my way into its confidences. Butilata made no secret of the part your people played."

"You are the Ranee of Butilata! You lived a double life!" he said slowly as though in order that he should hear and understand.

"I lived a double life," she said. "By day I was your clerk. In the evening I was the Ranee of Butilata who gave parties to the countryside. My car was always waiting round the corner for me and brought me back the next morning. Once I was nearly betrayed. Dora Mead came to Newbury unexpectedly and would have recognized me but I switched out the lights and had her removed from the house. By day I slaved for you for three pounds a week, using my position to rob your firm systematically and consistently. Yes I robbed you," she went on. "All the thousands standing to the credit of my account were transferred from the profits of the firm. I came into your business to ruin you," she said, "and to ruin Tom Camberley too, but he was a decent man. And because he expressed his pity for the poor girl who had been sent out to Butilata, I persuaded you to buy him out and save his money from the wreck."

"You—you!" hissed Covent. He made an attempt to lurch forward, but fell backward and the girl rising to her feet lowered him to the seat. She covered him with a travelling rug and presently the train began to slow down.

It was a dark and rainy night and when the train came a stop at the little platform she slipped out, closing the door behind her and disappeared into the gloom.

They found Martin Covent at Southampton and brought him back to town to face his outraged clients and the inexorable vengeance of the law. But the stout black wallet that carried the proceeds of his robbery was never recovered and the Ranee of Butilata vanished as though the earth had opened and swallowed her.

LAWYERS who write books are not, as a rule, popular with their confrères, but Archibald Lenton, the most brilliant of prosecuting attorneys, was an exception. He kept a case book and published extracts from time to time. He has not published his theories on the Chopham affair, though I believe he formulated one. I present him with the facts of the case and the truth about Alphonse or Alphonso Riebiera.

This was a man who had a way with women, especially women who had not graduated in the more worldly school of experience. He described himself as a Spaniard, though his passport was issued by a South American republic. Sometimes he presented visiting cards which were inscribed 'Le Marquis de Riebiera', but that was only on very special occasions.

He was young, with an olive complexion, faultless features, and showed his two rows of dazzling white teeth when he smiled. He found it convenient to change his appearance. For example: when he was a hired dancer attached to the personnel of an Egyptian hotel he wore little side whiskers, which, oddly enough, exaggerated his youthfulness; in the Casino at Enghien, where by some means he secured the position of croupier, he was decorated with a little black moustache. Staid, sober and unimaginative spectators of his many adventures were irritably amazed that women said anything to him, but then it is notoriously difficult for any man, even an unimaginative man, to discover attractive qualities in successful lovers.

And yet the most unlikely women came under his spell and had to regret it. There arrived a time when he became a patron of the gambling establishments where he had been the most humble and the least trusted of servants, when he lived royally in hotels, where he once was hired at so many piastre per dance. Diamonds came to his spotless shirt front, pretty manicurists tended his nails and received fees larger than his one time dancing partners had slipped shyly into his hand.

There were certain gross men who played interminable dominoes in the cheaper cafés that abound on the unfashionable side of the Seine, who are amazing news centres. They know how the oddest people live and they were very plain spoken when they discussed Alphonse. They could tell you, though heaven knows how the information came to them, of fat registered letters that came to him in his flat in the Boulevard Haussman. Registered letters stuffed with money, and despairing letters that said in effect (and in various languages) "I can send you no more—this is the last." But they did send more.

Alphonse had developed a well organised business. He would leave for London, or Rome, or Amsterdam, or Vienna, or even Athens, arriving at his destination by sleeping car, drove to the best hotel, hired a luxurious suite—and telephoned. Usually the unhappy lady met him by appointment, tearful, hysterically furious, bitter, insulting, but always remunerative.

For when Alphonse read extracts from the letters they had sent to him in the day of the Great Glamour and told them what their husbands income was almost to a pound, lira, franc or guider, they reconsidered their decision to tell their husbands everything and Alphonse went back to Paris with his allowance.

This was his method with the bigger game; sometimes he announced his coming visit with a letter discreetly worded, which made personal application unnecessary. He was not very much afraid of husbands or brothers; the philosophy which had germinated from his experience made him contemptuous of human nature. He believed that most people were cowards and lived in fear of their lives, and greater fear of their regulations. He carried two silver-plated revolvers, one in each hip pocket. They had prettily damascened barrels and ivory handles carved in the likeness of nymphs. He bought them in Cairo from a man who smuggled cocaine from Vienna.

Alphonse had some twenty "clients" on his books and added to them as opportunity arose. Of the twenty, five were gold mines (he thought of them as such) the remainder were silver mines.

There was a silver mine living in England, a very lovely, rather sad-looking girl, who was happily married except when she thought of Alphonse. She loved her husband and hated herself and hated Alphonse intensely and impotently. Having a fortune of her own she could pay—therefore she paid. Then in a fit of desperate revolt she wrote saying: "This is the last, etc." Alphonse was amused. He waited until September when the next allowance was due, and it did not come. Nor in October, nor November. In December he wrote to her; he did not wish to go to England in December, for England is very gloomy and foggy, and it was so much nicer in Egypt; but business was business.

His letter reached its address when the woman to whom it was addressed was on a visit to her aunt in Long Island. She had been born an American. Alphonse had not written in answer to her letter; she had sailed for New York feeling safe.

Her husband, whose initial was the same as his wife's, opened the letter by accident and read it through very carefully. He was no fool. He did not regard the wife he wooed as an outcast; what happened before his marriage was her business—what happened now was his.

And he understood these wild dreams of hers, and her wild uncontrollable weeping for no reason at all, and he knew what the future held for her.

He went to Paris and made inquiries: he sought the company of the gross men who play dominoes and heard much that was interesting.

Alphonse arrived in London and telephoned from a call box. Madam was not at home. A typewritten letter came to him, making an appointment for the Wednesday. It was the usual rendezvous, the hour specified, an injunction to secrecy. The affair ran normally.

He passed his time pleasantly in the days of waiting. Bought a new Spanza car of the latest model, arranged for its transportation to Paris and in the meantime amused himself by driving it.

At the appointed hour he arrived, knocked at the door of the house and was admitted.

Riebiera, green of face, shaking at the knees, surrendered his two ornamented pistols without a fight.

At eight o'clock on Christmas morning Superintendent Oakington was called from his warm bed by telephone and was told the news.

A milkman, driving across Chopham Common, had seen a car standing a little off the road. It was apparently a new car and must have been standing in its position all night. There were three inches of snow on its roof, beneath the body of the car the bracken was green.

An arresting sight even for a milkman, who at seven o'clock on a wintry morning had no other thought than to supply the needs of his customers as quickly as possible and return at the earliest moment to his own home and the festivities and feastings proper to the day.

He got out of the Ford he was driving and stamped through the snow. He saw a man lying, face downwards, and in his grey hand a silver-barrelled revolver. He was dead. And then the startled milkman saw the second man. His face was invisible; it lay under a thick mask of snow that made his pinched features grotesque and hideous.

The milkman ran back to his car and drove towards a Police station.

Mr. Oakington was on the spot within an hour of being called. There were a dozen policemen grouped around the car and the shapes in the snow; the reporters, thank God, had not arrived.

Late in the afternoon the superintendent put a call through to one man who might help in a moment of profound bewilderment.

Archibald Lenten was the most promising of Treasury Juniors that the Bar had known for years. The Common Law Bar lifts its delicate nose at lawyers who are interested in criminal cases to the exclusion of other practice. But Archie Lenten survived the unspoken disapproval of his brethren and concentrating on this unsavoury aspect of jurisprudence was both a successful advocate and an authority on certain types of crime, for he had written a text-book which was accepted as authoritative.

An hour later he was in the superintendent's room at Scotland Yard, listening to the story.

"We've identified both men. One is a foreigner, a man from the Argentine, so far as I can discover from his passport, named Alphonse or Alphonso Riebiera. He lives in Paris and has been in this country for about a week."

"Well off?"

"Very, I should say. We found about two hundred pounds in his pocket. He was staying at the Nederland Hotel and bought a car for twelve hundred pounds only last Friday, paying cash. That is the car we found near the body. I've been on the 'phone to Paris, and he is suspected there of being a blackmailer. The police have searched and sealed his flat, but found no documents of any kind. He is evidently the sort of man who keeps his business under his hat."

"He was shot you say? How many times?"

"Once, through the head. The other man was killed in exactly the same way. There was a trace of blood in the car, but nothing else."

Mr. Lenten jotted down a note on a pad of paper.

"Who was the other man?" he asked.

"That's the queerest thing of all—an old acquaintance of yours."

"Mine? Who on earth—?"

"Do you remember a fellow you defended on a murder charge—Joe Stackett?"

"At Exeter, good Lord, yes! Was that the man?"

"We've identified him from his finger prints. As a matter of fact, we were after Joe—he's an expert car thief who only came out of prison last week; he got away with a car yesterday morning, but abandoned it after a chase and slipped through the fingers of the Flying Squad. Last night he pinched an old car from a second-hand dealer and was spotted and chased. We found the car abandoned in Tooting. He was never seen again until he was picked up on the Chopham Common."

Archie Lenton leant back in his chair and stared thoughtfully at the ceiling.

"He stole the Spanza—the owner jumped on the running board and there was a fight—" he began, but the superintendent shook his head.

"Where did he get his gun? English criminals do not carry guns. And they weren't ordinary revolvers. Silver-plated, ivory butts carved with girls' figures—both identical. There was fifty pounds in Joe's pocket; they are consecutive numbers to those found in Riebiera's pocket book. If he'd stolen them he'd have taken the lot. Joe wouldn't stop at murder, you know that, Mr. Lenten. He killed that old woman in Exeter although he was acquitted. Riebiera must have given him the fifty—"

A telephone bell rang; the superintendent drew the instrument towards him and listened. After ten minutes of a conversation which was confined so far as Oakington was concerned to a dozen brief questions, he put down the receiver.

"One of my officers has traced the movements of the car, it was seen standing outside 'Greenlawns', a house in Tooting. It was there at 9.45 and was seen by a postman. If you feel like spending Christmas night doing a little bit of detective work, we'll go down and see the place."

They arrived half an hour later at a house in a very respectable neighbourhood. The two detectives who waited their coming had obtained the keys but had not gone inside. The house was for sale and was standing empty. It was the property of two old maiden ladies who had placed the premises in an agent's hands when they had moved into the country.

The appearance of the car before an empty house had aroused the interest of the postman. He had seen no lights in the windows and decided that the machine was owned by one of the guests at the next door house.

Oakington opened the door and switched on the light. Strangely enough, the old ladies had not had the current disconnected, though they were notoriously mean. The passage was bare, except for a pair of bead curtains which hung from an arched support to the ceiling.

The front room drew blank. It was in one of the back rooms on the ground floor that they found evidence of the crime. There was blood on the bare planks of the floor and in the grate a litter of ashes.

"Somebody has burnt papers—I smelt it when I came into the room," said Lenten.

He knelt before the grate and lifted a handful of fire ashes carefully.

"And these have been stirred up until there isn't an ash big enough to hold a word," he said.

He examined the blood prints and made a careful scrutiny of the walls. The window was covered with a shutter.

"That kept the light from getting in," he said, "and the sound of the shot getting out. There is nothing else here."

The detective sergeant who was inspecting the other rooms returned with the news that a kitchen window had been forced. There was one muddy print on the kitchen table which was under the window and a rough attempt had been made to obliterate this. Behind the house was a large garden and behind that an allotment. It would be easy to reach and enter the house without exciting attention.

"But if Stackett was being chased by the police why should he come here?" he asked.