RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

"Sandi the King-Maker," Ward Lock & Co., London, 1922

IN the village of P'pie, at the foot of that gaunt and hungry mountain which men called Limpisi, or Limbi, there lived a young man whose parents had died when he was a child, for in those far-off days the Devil Woman of Limbi demanded double sacrifices, and it was the custom to slay, not the child who was born upon her holy day—which was the ninth of the new moon—but his parents.

Therefore he was called by acclamation M'sufu-M'goba—'the-fortunate-boy-who-was-not-his-own-father'. All children who are born of sacrificed parents are notoriously clever, and M'sufu was favoured of ghosts and devils. It is said that when he was walking-young he climbed up to the cave of the Holy Devil Woman herself, passing through the guard of Virgins, who kept the hillside, in a most miraculous way, and that he had tottered into that dreadful cave whence no human had emerged alive, and had found the Old Woman sleeping.

He came forth alive and again reached the village. So it was said—and said secretly between husband and wife, or woman and lover (for these latter trust one another). Aloud or openly not one spoke of such a fearful exploit or even mentioned the Old Woman, save parabolically or by allusion.

But to this visit and the inspiration of The Cave-of-Going-In were ascribed the wonderful powers which came to him later in life.

It is told that, seated at food with one of the families which had adopted him, he suddenly broke an hour's silence.

"K'lama and his goat are dead by the deepstones."

"Silence, little child," said his indignant foster-parent. "Are you not ashamed to talk when I am eating? In this way all devils get into a man's body when his mind is thrown all ways."

Nevertheless, a search-party was sent out, and K'lama and his goat were found dead at the bottom of a rocky bluff; and one old man had seen this happen, the goat being suddenly mad and leaping with K'lama at the leash of it, just as the sun rim tipped the mountain-top. At such an hour had M'sufu spoken!

Then another miracle. One Doboba, a gardener, had flogged M'sufu for stealing bananas from his garden.

"Man," said M'sufu, rubbing his tingling seat, "a tree will fall upon you in two nights, and you will be with the ghosts."

And two nights after this Doboba died in such a way.

The story and the fame of M'sufu spread until his name was spoken even in the intimate places of the Old King's hut. And there came one Kabalaka, Chief of all the Tofolaka, this being the country which is separated from the Ochori by the Ghost Mountains, and Kabalaka was a great man in the king's eyes, being his seni-seni, which means Chief Minister.

"Oh, prophesy for me, M'sufu," he said, and before the whole twittering village—aghast at the advent of this amazing prince and his ten companies of spearmen and his dancing women—M'sufu stood up.

"Lord," he said "the crops of the land will be good and better than good. But the crops of the Fongini shall die, because no rain will come and the earth will crack."

"What else?" said Kabalaka, not displeased, for he hated the Fongini and Lubolama, their chief, and was jealous of his influence with the Old King.

"Lord," said the young seer, sweating greatly, "the son of your wife is sick and near to death, but on the rind of the moon he shall live again."

Kabalaka bent his brows, for he loved the son of his wife, and made a forced march back to Rimi-Rimi to find the child already laid for death, with clay upon his eyelids.

"Wait until the rind of the moon, for this child will not die," said Kabalaka in a confident tone, but inwardly aching.

So they waited, watching the fluttering breath of the boy, the women-folk going out every morning to pluck green leaves to deck their bodies in the death dance. But on the rind of the moon the child opened his eyes and smiled and asked for milk.

And then a week later, when the people of The True Land, as Rimi-Rimi was called, were labouring to get in their mighty crops, there came to the city Lubolama of the Fongini, begging remission of tribute.

"For my crops have failed, Old King," he said, "and there has been no rain, so that the fields are cut with great cracks."

That night the Old King sent for M'sufu, and the prophet, wearing a beautiful brass chain which the grateful Kabalaka had sent him, arrived in the city at the very hour the king's guard pulled down Hughes at Hughes Lloyd Thomas, Inspector of Territories in the service of the British Government.

Lloyd Thomas, in the days before he entered the Service, had been an evangelist—a fiery Welsh revivalist who had stirred the Rhondda Valley by the silvery eloquence of his tongue. Something of a mystic, fay as all Celts are, he had strangely survived the pitfalls which await earnest men who take service under Government. It was the innate spirituality of the man, the soul in him, and his faith, that made him smile whimsically up into the lowered face of K'salugu M'popo, the Old One, Lord and Paramount Lord of the Great King's territory.

They had staked him out before the Old King's hut, and his head was hot from the king's fire which burnt behind him. His travel-soiled drill was stiff with his blood, great rents and tears in his coat showed his broad white chest and the dark brown V of his shirt opening; but though he lay on the very edge of darkness, his heart was big within him, and he smiled, thanking God in his soul that there was no woman whose face would blanch at the news, or child to wonder or forget, or mother to be stricken.

"Ho, Tomini," said the Old King mockingly, and blinking down at his prisoner through his narrow eye-slits, "you called me to palaver before my people, and I am here."

Lloyd Thomas could turn his head, did he desire, and see a sector of that vast congregation which waited to witness his end—tier upon tier of curious brown faces, open-eyed with interest, children who desired sensational amusement. Truly he knew that all the city of Rimi-Rimi was present.

"I came in peace, K'salugu M'popo," he said, "desiring only to find Fergisi and his daughter: for evil news has gone out about them, and his own wife came to my king, telling of a killing palaver. Therefore my king has sent me, bringing you many beautiful presents, and knowing that you are strong for him, and will tell me about this God-man."

The presents were stacked in a heap by the side of the Old King's stool—bolts of cloth, shimmering glass necklaces, looking-glasses such as kings love, being in gift frames.

The king withdrew his eyes from the prisoner and bent down to pick up a necklace. He held it in his hand for a moment, and then, without a word, tossed it into the fire. At a word from his master, Kabalaka picked up the remainder and flung them into the blaze.

Lloyd Thomas set his teeth, for he knew the significance of this.

"Lord, since I am to die, let me die quickly." he said quietly.

"Let Jububu and M'tara, who skin men easily, come to me," said the Old King, and two naked men came from behind the fire, their little knives in their hands.

"O king—" it was Lloyd Thomas who mocked now, and there was a fire in his eyes which was wonderful "—O skinner of men and slayer of little girls, one day and another day you shall live, and then shall come one in my place, and he shall smell you out and feed your bodies to the fishes."

"Let the skinning men work slowly," said the Old King, rubbing his scrubby chin, and the two who knelt at Lloyd Thomas's feet whetted their little knives on the palms of their hands.

"He shall come—behold, I see him!" cried the doomed man. "Sandi Ingonda, the tiger, and the cater of kings!"

The king half rose from his chair, his puckered face working.

"O men, let me speak," he said huskily, "for this man has said a wicked thing, Sandi being dead. Yet if he lived, who can cross the mountains of ghosts, where my regiments sit? Or can his iron puc-a-puc force a way through the swift waters of the river?"

"He will come," said the prisoner solemnly, "and he shall stand where I lie, and on that hour you shall die, K'salugu M'popo."

The Old Man blinked and blinked.

"This is evil talk, and this man is a liar, for Sandi is not. Did not the man of the Akasava say that Sandi went out upon the black waters and fell through a hole in the world?"

"Lord king, it was said," agreed Kabalaka.

The king sat back on his stool.

"If Sandi comes, he dies, by death," he swore uneasily, "for I who sent the daughter of the God-man, into the earth and delivered the God-man himself to the Terrible Woman of Limbi, even I have no fear. O M'sufu!"

And there came from amongst the women behind the king a youth wearing a glittering chain.

"O M'sufu, see this man. Now prophesy for me, shall Sandi come to this land, where he has never come before, for is not this land called Allimini*, and was there not held a great palaver because the white Frenchis came, cala cala and how may Sandi, who is neither Frenchi nor Allimini, but Inegi, put foot in this land?"

[*German]

M'sufu realized the splendour of the moment, and strutted forth, his head thrown back, his arms extended.

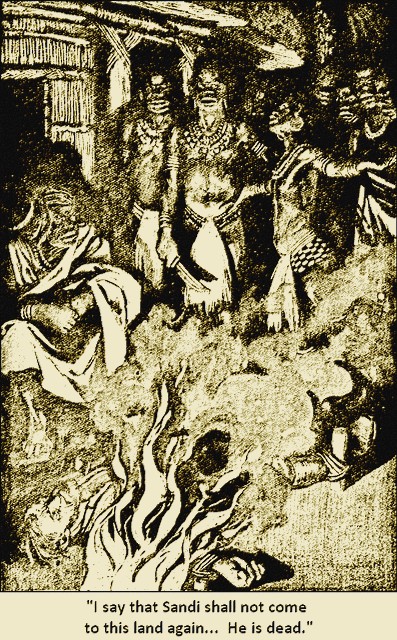

"Hear me, Great King. Hear M'sufu, who has strange and lovely powers. For I say that Sandi shall not come to this land again—neither to the king's country, nor to the lands of the base people on the lower river. He is as dead."

The Old King was on his feet, his legs trembling.

"Hear him!" he yelled, and snatched his killing spears from the ground beside him. "O Tomini, hear this man—liar—liar—liar!"

And with every word, he struck, though he might have saved himself the trouble, for Lloyd Thomas died at the first blow.

The Old King looked down at his work, and his head was shaking.

"O ko," he said, "this is a bad palaver, for I have killed this man too quickly. Now, M'sufu, your voice has been beautiful to me, and you shall build in the shadow of my hut. For I know now that Sandi will not come. But if a devil is in your heart, and you have spoken lies, you shall lie where he lies, the Cold One, and my skinning men shall know your voice."

THERE is something in the atmosphere of the British Colonial Office which chills the stranger to an awed silence. The solemnity of lofty corridors and pale long windows is oppressive. Noble and sombre doors, set at intervals as regular as the cells of a prison, suggest that each door hides some splendid felon. There are in these corridors at certain hours of the day no manifestations of life, save for the occasional ghostly apparition of a solitary clerk, whose appearance in the vista of desolation is heralded by the deep boom of a closing door, sounding to the nervous visitor like a minute gun saluting the shade of a mourned official.

A tanned, slight man came into one of these corridors on an October afternoon, and the sound of his halting feet echoed hollowly. He was consulting a letter, and stopped at each doorway to examine the number. Presently he stopped, hesitated, and knocked. A subdued official voice bade him enter.

The room was occupied by two sedate young gentlemen, whose desks had been so disposed that each had an equal opportunity of looking out of the window, and at sight of Sanders one of the youths rose with a heaviness of movement that suggested premature age—this also being part of the atmosphere of the Colonial Office—and walked with a certain majesty across the room.

"Mr. Sanders?" he whispered rather than said. "Oh, yes, Mr. Under-Secretary was expecting to see you." He looked at his watch. "I think he will be disengaged now. Won't you please sit down?"

Sanders was too impatient and too nervous to sit. He had all the open-air man's horror of Government offices, and his visits to the headquarters of his old Department had been few and at long intervals. The young man, who had disappeared into an adjoining room, returned, opened wide the door, and ushered Sanders into a larger room, the principal features of which were a carved marble fireplace and a large desk.

A gentleman at this latter rose, as Sanders came hesitatingly into the room, and welcomed him with a smile. The humanity of that smile, so out of place in this dead and dismal chamber, did something to restore the visitor's vitality.

"Sit down, Mr. Sanders." And this time Sanders did not refuse.

The Secretary was a tall lean man, thin of face and short-sighted, and Sanders, who had met him before, was as near ease as he was likely to be in such surroundings. Mr. Under-Secretary did not seem to be anxious to discuss the object of Sanders's summons. He talked about Twickenham, about the football games which were played in that district, about life in the Home Counties, and presently, when Sanders had begun to wonder why a Colonial Office messenger had been detailed to deliver a letter to him that morning, the Under-Secretary came suddenly to the point.

"I suppose you're out of Africa for good, Mr. Sanders?" he said.

"Yes, sir," said Sanders quietly.

"It's a wonderful country," sighed Sir John Tell, "a wonderful country! The opportunities today are greater than they have ever been before—for the right man."

Sanders made no reply.

"You know Tofolaka and the country beyond the Ghost Mountains, of course," said Mr. Under-Secretary, playing with his pen and looking intently at the blotting-pad.

"Yes, very well," smiled Sanders. "That is, as well as anybody knows that country. It is rather terra incognita."

Sir John nodded.

"You call it, I think—?" he said suggestively.

"We called it the country of the Great King," said Sanders. "It lies, as you know, beyond the Ochori country on one side of the river and the Akasava on the other, and I never went into the country except once, partly because the mountain roads are only passable for three months in the year, and I could never get sufficient, steam or speed into the Zaire—that was my ship, you remember—to pass through Hell Gate."

"Hell Gate?" said Sir John reflectively. Oh, yes, that is the narrow canyon beyond the Ghost Mountains. There is a terrific current, isn't there?"

"Ten knots," said Sanders promptly, "and no slack water. Hell Gate has done more to keep the Great King's country free from inquisitive visitors than any other cause. I should imagine. By—the way, that was German territory, was it not?" he asked, with sudden interest.

"It was and it wasn't," said Sir John carefully. "There were two or three nations which marked the territory on their colonial maps, although none can claim either to have conquered or occupied the country. And that is just why I wanted to see you, Mr. Sanders. At the Peace Conference, when the question of the redistribution of Germany's colonies came up for decision, the Great King's territory gave us more trouble and caused more—er—unpleasantness than any other of her possessions which we took over. You see"—he shifted round and faced Sanders, leaning back in his chair and crossing his legs comfortably—"it was never admitted by any of the great nations that the Great King's country belonged to anybody. It is now virtually under the dominion of the—er—League of Nations." he said.

Sanders smiled.

"That means it's still No Man's Land." he said bluntly.

"In a sense, yes," agreed the Under-Secretary. "As a matter of fact, we have received a mandate from the League to straighten out matters, put the country on a proper footing, and introduce something of civilization into a territory which has hitherto resisted all attempts at penetration, pacific or otherwise."

He stopped, but Sanders made no comment.

"We think," said Sir John carefully, "that in six or seven months a strong, resolute man with a knowledge of the native—a superhuman knowledge, I might add—could settle the five territories now under the Great King, and establish law and justice in a country which is singularly free from those ethical commodities."

Again he paused, and again Sanders refrained from speaking.

Sir John rose and, walking to the wall, pulled down a roller map.

"Here is a rough survey of the country, Mr. Sanders," he said.

Sanders rose from the chair and went to the other's side.

"Here are the Ghost Mountains, to the west of which are your old friends, the Ochori; to the cast is Tofolaka, and due south on the other side of the big river is Bubujala. Here the river takes a turn—you will see a lake, very imperfectly charted."

"What is that island asked Sanders, pointing.

"That is called the Island of the Golden Birds—rather romantic," said Sir John.

"And that." said Sanders, stabbing the map with his forefinger, "is Rimi-Rimi, where the Old King lives."

"And north is a mountain—Limpisi." said the Under-Secretary. "That would be new country for you, Mr. Sanders; you're not used to mountains and plateaux. It is very healthy, I'm told, and abounding in big game."

"Very probably it is," said Sanders, returning to the table with his superior, "but I really know very little about it, Sir John, and if you have sent for me to give you information, I'm afraid I'm going to disappoint you."

The Under-Secretary smiled.

"I have sent for you to give you some information, Mr. Sanders," he said quietly. "I have told you we want a resolute man, a man who has authority over natives, such as you possess, to go out and settle the country."

"I'm sorry—" began Sanders, shaking his head.

"Wait." The Under-Secretary stopped him with a gesture. "The Government is most anxious that this should be done at once, because—" he hesitated "—you may have heard the news, we sent a man to interview the Old King and make inquiries about the poor Fergusons, the missionaries, and—", He shrugged.

"They chopped him?" said Sanders. "Who was it?"

"Lloyd Thomas."

Sanders nodded.

"I knew him, poor chap. But it is a fairly dangerous proceeding to send a man into the Great King's country alone."

"Ye—es," agreed the other, "it was an error on the part of your successor, Mr. Sanders, but one for which, of course, we must take full responsibility. This is what I want to say. The war in Africa has passed the king's territory untouched. There was neither the need nor the occasion for either side to penetrate in that direction, so that the Old King has neither had the salutary lessen which the passage of troops through his country might have afforded, nor such supervision as Germany was able to exercise. The result is—" his voice was grave "—there is serious trouble threatened to your old territory. From what we have been able to discover, Lloyd Thomas was received in the haughtiest manner, and the gifts he took with him to propitiate the Old Man were burnt at the king's great fire!"

Sanders made a little grimace.

"That's bad. Poor Thomas could not have had the opportunity, or he would have cleared when he saw that happen. It is a tradition, you know, that wars in the Northern Territory start with the burning of gifts—it is so with the Northern Ochori and with the Akasava."

He was silent for a while, then drew a long breath.

"I should like to help the Government, Sir John," he said, "but honestly I am out of Africa for good!"

The Under-Secretary scratched his chin and again avoided Sanders's eye.

"We have sent a beautiful little ship to the river," he said; "it is a great improvement on the Zaire and with three times her power."

Sanders shook his head.

"I'm sorry," he said.

"Of course, we shouldn't object to your choosing your own officers and advancing them one grade in their ranks—even if they have left the Service," he added significantly. "I understand that your brother-in-law, Captain Hamilton—"

"He's out of it, too," said Sanders quickly, though here he might have hesitated, for Hamilton at that moment was nursing a sore heart. Women are proverbially fickle, and there had been a certain Vera Sackwell, who had married a man better favoured than Hamilton in the matter of riches.

"And Mr. Tibbetts?"

Sanders smiled.

"Mr. Tibbetts is a very rich man now," he said, "and nothing would induce him to leave London—of that I am perfectly sure," he said.

The Under-Secretary shrugged his shoulders and rose.

"I'm sorry, too," he said. "Anyway, think it over for a couple of days, Mr. Sanders, and let me know what you think. You are already Commander of St. Michael and St. George, I believe?"

"Yes, sir," said Sanders, with a ghost of a smile on his tanned face.

"Six months' work," said Sir John absently, "and the Government would not be unmindful of its obligation to the man who accomplished that work, Mr. Sanders. To a man like you, of course," he said, with a deprecating smile, "a knighthood means nothing. But the ladies rather like it. You're married, are you not, Mr. Sanders? Why, of course you are! Good-bye." He held out his hand, and Sanders shook it. "By the way," said Sir John, "that Ferguson case was a bad one. We have inquiries every week from the poor mother."

Sanders nodded. He had met the wife of the murdered missionary, and he wanted to forget her.

"She has a theory that the girl, her daughter, is still alive in the hut of one of the king's chiefs."

"Perfectly horrible!" said Sanders shortly. "Please God, she's dead! Good-bye, sir. I'm sorry—"

The aged youth from the room outside appeared from nowhere and opened the door, and in a few minutes Sanders was walking along Whitehall, a very preoccupied man.

It so happened that that night there was a little dinner-party at Twickenham. Mr. Tibbetts, late of the City, and now devoting his great mind to intensive agriculture, was present, and with him a pretty girl, whom he addressed with extravagant and solemn deference; and Hamilton was there, sometime captain of Houssas, a little peaky of face, for he had taken the loss of the lady who was now Mrs. Isadore Mentleheim very badly; and, above all, Patricia Sanders, in Sanders's eyes the most radiant being of any.

It is perhaps incorrect to say that Bones was present, because he had not arrived when the dinner started, and his late arrival added something to the restraint for which Sanders was mainly responsible. He had returned silent and thoughtful, and his wife, who had half-guessed the object of his call to the Colonial Office, did not press him for an account of what had transpired, knowing that in good time he would tell, She guessed what the object of that summons had been, did he but know.

"Come on, Bones," growled Hamilton. "Do you know you've kept us waiting for half an hour?"

Bones had burst into the room, straightening his tie as he came, and bowed reverently to the girl who sat at his right, respectfully to Sanders and affectionately to Patricia, before he had taken his scat.

"Dear old officer!" said Bones. "Tomatoes!"

"Tomatoes?" said Hamilton, looking at his soup. "It is consomme."

"When I say tomatoes, dear old thing." said Bones loftily, "I imply the trend and tendency of my jolly old studies. As dear old Hamlet said—"

"Shut up and eat your soup," said Hamilton.

"Give me the jolly old farm," said Bones ecstatically, pausing with his spoon half-way to his mouth, heedless of the drip, drip, drip of consomme julienne which fell upon his immaculate shirt—front. "Give me—"

"Give him a table napkin and a bib," said Hamilton savagely. "Really, Bones, don't you recognize there's something in the air? Haven't you any sensibility?"

"None, dear old thing." said Bones firmly, and turning to his partner. "Lovely old child," he asked, "have you noticed any of that jolly old nonsense about poor old Bones?"

"Have you decided to stick to farming, Bones?" It was Sanders who asked the question.

"Yes, sir," said Bones promptly. "I've got the jolliest old scheme for raising cabbages in hot-water bottles—in the off-season, dear old Ham, you understand," he said, turning to his friend. "It's funny that nobody ever thought about hot-water bottles. You fill them with hot water."

"Why not hot air?" asked the offensive Hamilton.

"It's a pretty good job you've decided to stick to farming," said Sanders, "because what I'm going to tell you won't worry you. I've had an offer to go back to the Territories. Not exactly the Territories," he corrected, "but to the Great King's country, beyond the Ochori."

Bones and Hamilton put down their spoons together.

"Dear me," said Bones mildly.

"Of course I turned it down," said Sanders indifferently.

"Of course," said Bones.

"Naturally." said Hamilton.

"The idea was for us to go out for six months—"

"Us?" said Bones. "Did you say 'us', dear old Commissioner?"

"I said 'us' for it amounted to that," smiled Sanders. "They offered to let me choose any officers I liked, and to give them a rank one grade higher than that at which they retired. That would make Hamilton a major, and you, Bones, a full-blown skipper."

Bones coughed.

"As I say, I turned it down," said Sanders. "I don't want to go back—even for six or seven months."

"Would it mean anything good for you?" asked Patricia quietly.

Sanders smiled.

"Well, I suppose they'd be grateful, and all that sort of thing, but I told them I was finished with Africa, and I told them, Hamilton, that you were also settled down, as you are, now you're running Bones's business."

"Quite," said Hamilton. "Of course this is rather a slack time of the year, and we are taking up nothing new for another six months."

"Besides," Sanders went on, "I don't see the fun of upsetting one's life even for six months. It isn't as if we were going back to the humdrum old Territories again. Apparently the Old King's up in arms, and there would be all sorts of trouble until we got him tamed."

"Would there be any danger?" The girl on Bones's left looked at him apprehensively.

"Danger, dear old fiancée!" said the excited Bones, "Danger doesn't worry us, dear old thing. Danger is the neth of my brostrils—I mean noth of my bristrils. Danger?" He was preparing to elaborate, but a warning glance from Sanders stopped him. "Danger? No, dear old friend and partner," he said soothingly. "When I said 'danger', I was talking figuratively. Danger! Ha, ha!"

Bones had a laugh which made you wince.

"Absolutely none, charming old child, and soon to be, I hope—ahem! A jolly old lion or two, a few naughty old cannibals, a wicked old king who wants to cut your jolly old head off, and there you are! Nothing startling!"

"Anyway," said Sanders, after a pause, "I told the Secretary that I can't possibly go. So that's that."

"Quite," said Hamilton, and Bones coughed again.

"I shall have quite a lot of work to do, clearing up the mess that Bones has left," Hamilton went on, "and Bones has pretty well decided on his farm. But it is rather an interesting offer."

"Very." said Sanders.

And then distraction came, and the tension broke. A maid came into the room and bent over her mistress.

"Mrs. Ferguson?" she said in surprise. "Isn't that the poor woman who lost her husband and child, dear?"

Sanders groaned. He saw the hand of a cunning Under-Secretary in this visitation.

"Yes—er—I'll see her."

"Show her in here, Mary," said Patricia, and before Sanders could protest the girl was gone.

"Why, what is the matter?" Patricia asked anxiously.

"Oh, nothing—nothing, dear."

The men rose as the visitor entered the room. She was a slight, frail woman in black, and two deep sad eyes fastened upon Sanders, and he quailed before them.

"You know Mr. Hamilton—Mr. Tibbetts—er—miss—" he stammered.

She took the chair he offered her.

"Mr. Sanders, are you going?" she asked.

Sanders flushed.

"I want you to believe—" he began, and his wife watched his confusion in astonishment.

"Mrs. Sanders, will you let your husband go?" said the woman in a low voice. "You have always been kind and sweet to me, and I know how great is the sacrifice I ask."

"My wife will let me go if I wish to," said Sanders and so quiet was the room that his voice sounded loud.

Mrs. Ferguson was silent for a while.

"I saw it," she said. "They came when we were at breakfast—though the Old King had eaten salt with my husband—and Mofobolo, the king's hunter, led them. Henry told me to run to the river, where our little steamboat was. I saw them drag him out covered with blood, and I saw Mofobolo running after my—my darling—into the bush. Oh, my God, Mr. Sanders! He has her, that man! She will be nineteen on the first of the month!"

"Mrs. Ferguson, please!"

Sanders's face was drawn, and in his eyes there was a look of agony.

"She's there—there now!" the woman almost screamed. "Every hour you defer your decision is a crime, a crime!"

The women took her out, and the men sat in silence each with his separate thoughts. They heard the thud of the front door closing, and the grind of a cab's wheels on the gravel of the drive, and then the two women returned.

Patricia, as she passed her husband, dropped her hand upon his shoulder, and he caught and kissed it.

"I am leaving by the next Coast steamer," he said simply. "Who goes with me?"

There was no need to ask. Hamilton was smiling savagely, and as for Bones, he was swaying backwards and forwards in his chair, his eyes half-closed, like a man in a trance, and he was uttering strange sounds. Strange to the two women was that raucous chant of his, though Patricia caught the rhythm of it, for Bones was singing the song of the fighting Isisi, the song that they used to roll forth in deep-chested chorus as the little Zaire came round the bend of the river in sight of its landing-place.

"Sandi, who makes the laws, Sandi, who walks by night, Sandi, the slayer of Oosoombi. And the hanger of N'gombo. Who gives health to the sick, And justice to the poor..."

ACROSS the Ghost Mountains came the shrill rataplan of a lokali, and the signal drummer of the Ochori, who sent the message, put his whole heart and pride in it.

"SANDI, THE BUTCHER BIRD, THE SWIFT GIVER OF LAWS...SANDI IS!"

They carried the message to the Old King, and he foamed at the mouth.

"Bring me M'sufu, the prophet," he howled, "also they who skin men! By death, there shall be one magician less in the land this night!"

And they brought M'sufu, and they killed him before the morning.

A LONG broad-beamed boat was pushing her way through the black waters which swirled and eddied against her bow. She was painted a dazzling white, and her two high smoke-stacks were placed one behind the other, giving her an appearance of stolidity which was very satisfactory to the young man who had constituted himself her chief officer. The open lower deck was a few feet over the water-line, and seemed at a distance to be decorated with bright scarlet poppies. Near at hand these resolved themselves into the new red tarbooshes of the native soldiers who crowded the iron deck. Above was another deck, from which opened the doors and latticed windows of a dozen cabins. Two or three deep-seated wicker chairs and a light table were disposed on the clear space under the big awning aft, but this space reserved for the hours of leisure was deserted. Three men in white duck trousers and coatless stood on the little navigating bridge where the shining brass telegraphs stood, and behind them, raised on a grated dais, a native, bare to the waist, held a polished wheel.

The ship was named Zaire II, and the big searchlight on the bridge, the quick-firing guns which were swung out over each side, the tiny ensign which fluttered at her one mast, all these things stood for the expectation of war.

The ship was running between sheer rock walls, and the passage was growing narrower. Already the water at the Zaire's bow was piled up to the height of three feet above the level of the river, and the hull shivered and strained at every thud of the engine.

"We're only making five knots," said the troubled Sanders, "and we're nowhere near the worst part of the rapids."

He pointed ahead to where the flanking walls of the canyon rose to a greater height.

"Hell Gate properly begins at that bend." he said. "They've a full head of steam below, Bones?"

Bones was mopping his steaming face with a handkerchief coloured violently.

"A swollen head of steam, dear old Excellency." he said solemnly, and added unnecessarily: "Trust old Bones."

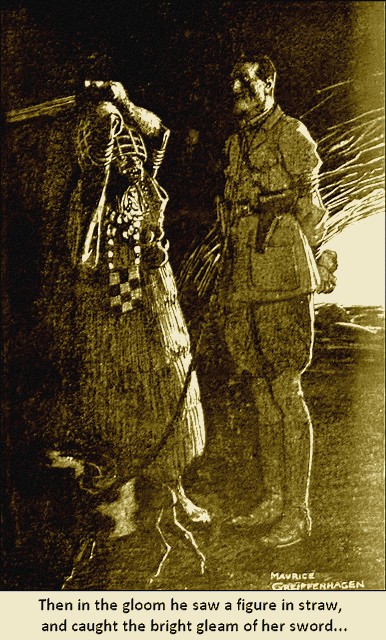

Behind the steersman was the broad open door of a cabin. It was plain but pleasantly furnished, but for the bizarre Thing which stood by the side of the white-covered bed.

Hamilton, major of Houssas, lolling with his back to the rail, caught a glimpse of this gaudy ornament and smiled, though he was in no smiling humour, for the country had brought afresh to him all the dreams he had dreamt in olden times, and, since those dreams and memories revolved about a capricious girl who had found her happiness in material things, they brought him little comfort.

"At least Guy Fawkes is enjoying the trip, sir." he said.

"Guy Fawkes?" Sanders was startled from his own thoughts. "Oh, you mean my bete?"

With a glance at the river ahead, he walked to the door of his cabin, Hamilton at his elbow, and looked in.

Held by two iron brackets in the wall was the most uncouth idol that Hamilton had ever seen. Its head, carved in wood, was painted green, save for its scarlet lips, and from the sides of its head sprouted a pair of ears which might be—and were, in fact—used as handles to lift the monstrosity. The body, painted fantastically, was pear—shaped, and the three squat vermilion legs on which it was supported added to its grotesqueness.

"Guy Fawkes ought to create a sensation in the Old King's country, if we—" He stopped.

"If we get there," finished Sanders quietly. "Well, the next few hours will decide that. Yes, he's rather beautiful, isn't he?"

"I don't quite understand, sir," said Hamilton. "It isn't like you to—er—"

"'Descend' is the word you want," smiled Sanders of the River.

"Well, yes. I've never known you to attempt the placation of a chief by mumbo-jumbery. That sort of thing is usually done in story-books; it isn't done on the river."

"We're going to a new country and a new people," said Sanders, "and that is my excuse. And Guy Fawkes will not burn," he added meaningly.

"Not—Oh, I see! You mean the Old King is burning his gifts....Guy Fawkes is made of iron, and will not burn. And you think that if it doesn't burn he'll be impressed?"

"They have never had a steel bete in this country before," said Sanders, and turned back to the bridge.

"Bones, come here." Hamilton beckoned him. "What do you think of Guy?"

Bones shook his head.

"He's a pretty old dear," he said, "but I wish I'd had the painting of him. Have you ever thought, dear old major and comrade, what I could have made of him with a few jolly old art shades?"

"Sanders thinks that when the Old King discovers that he won't burn—"

Hamilton was on the point of unburdening himself of his troubles, but changed his mind, and at that moment Sanders beckoned him.

"We're near to the crux of our situation," he said grimly. "Set twenty of your men at each side of the ship, and give them the poles I took aboard at the Isisi city. The current will probably drive us against one or the other wall of this ravine. Your men are to pole off the ship from the side."

Hamilton disappeared down the iron ladder which led to the lower deck.

The precaution was taken only in time. Ten minutes later the Zaire pounded slowly round the bend of the "gate" and the fierce current caught her. Slowly but surely she drifted over until the crest of the high cliff hung above her mast.

Nearer and nearer to the wall she drifted, her stem swinging the quicker. Then, when it seemed certain that she would smash against the smooth yellow rock, a dozen poles were thrust against the wall, a dozen sweating men grunted and strained, and the stern came out again.

The pressure of the river was now beyond anything Sanders had seen. The bows of the Zaire gathered water as a broom gathers snow. It sloped down almost from the rail above the bow like a big fluid hillside.

"More steam," said Sanders laconically, for the Zaire was practically at a standstill.

The smoke-stacks flamed, bellowing huge clouds of sparks, and slowly the boat moved forward. They pushed into what was by comparison slick water, and gathered their strength for the next bend. Here, so powerful was the force of the current, the river literally canted to one side, being, as Sanders judged, fully three feet higher on one bank than the other. 'Bank' was a courtesy term, for the cliffs fell sheer, and where the river ran to the left, the waters had scooped out a huge hollow, so that in places the river's edge disappeared from view. Though the sun was still high in the western sky, the canyon was in semi-darkness, so high were its walls.

"We'll run the searchlight off the storage batteries," said Sanders. "Be economical, Bones. I can't afford an ounce of steam for the dynamo, and as likely as not we'll be in this infernal hole till nightfall."

He was worried, yet felt the thrill and exhilaration of the fight. No boat had ever passed upstream through Hell Gate, though many had come down with the current. He remembered with a wince the half-mad wife of the dead missionary Ferguson, who had fled through this canon in a crazy little launch. Just then he did not want to think of missionaries—or their golden-haired daughters.

"The next bend is the worst," he said to Hamilton. "If we get through, we shall be at Rimi-Rimi tonight. I have an idea that the river is not watched as is the mountain road, and we ought to fetch up at the king's city without his being any the wiser."

The safety-valves of the Zaire's engines were hissing ominously as he put the nose of the boat to the last bend.

Then came Bones from below, Bones in soiled duck and with patches of black grease on his face.

"Cylinder leakin', sir," he said lugubriously, and Sanders could have wept.

ON the great hog-back crests of the Ghost Mountains at certain seasons of the year the spirits of chiefs come to eat salt with the most powerful ju-jus. Here comes M'shimba-M'shamba, who munches great swathes of forests and swallows whole villages for his satisfaction, and M'giba-M'gibi, who transforms himself into any manner of thing his fancy dictates. He is the one who walks behind you on dark nights, and though you turn ever so quickly, he vanishes. His is the face you remember and then do not remember. So that when you meet a man on the highway and stop suddenly, half raising your hand in salutation, and as suddenly you discover that his is the face of a stranger, spit once to the left and once to the right, for this is M'giba-M'gibi, "He Who Is Not."

Men travel many miles to watch the cold salt spread upon the ranges. It comes in a night, a thin powder through which the black and brown of rock show in piebald patches, and some there are who have seen the Ugly Ones gather in the dawn hour, and some, a daring few, have climbed to the peaks to steal ghost salt, only to find that, by the magic of the ju-ju, the salt has turned in their hands to water of terrifying coldness.

Through these mountains runs one road which winds upwards to the saddle of the highest ridge. Here in the right season the salt of the spirits drifts thigh-deep, and for just so long as the season lasts—never more than a month—no man ventures to cross the great barrier. Yet in such a time came a tall man who feared neither devils nor snows, for there was a greater fear in his heart which urged him onward, and bare-legged, bare, breasted, naked but for the kilt of monkey-tails about his middle, and having no other protection from the chill winds but his oval wicker shield, he trudged through the drifts.

He carried three short fighting-spears, and hanging from his belt was a broad-bladed sword fitting into a scabbard made from an elephant's car. He crossed the mountains, setting his face to the Great King's country, and the spies of the Great King saw him and beat out the news upon their signal drums.

None molested him, for the Great King's drum had rattled incessantly all one night with this instruction, and he who disobeyed the Old One did not wait for death, neither he nor his family.

He reached the first village on the wrong side of the mountain—for him—as the first flush of dawn lay pinkly on the snows. The village was awake and assembled, every man and woman and even the young children.

"I see you!" he boomed before the little chief. "I am a tired and a hungry man. Let me sleep and eat."

The chief said nothing. He gave the stranger the flesh of a young goat and a mess of mealies and fish, and then took him to a hut.

The stranger slept like a log for five hours, then walked to a little river and swam for a while. The sun dried him, and the chief again fed him. But none spoke to him, for all the village knew that he was the king's meat.

The guest asked for no information and gave none. He waved his farewell, and the chief nodded silently and watched him disappear round a bend of the narrow path into the forest. Then he called a palaver of all his people.

"Who saw a stranger?" he intoned.

"None saw him," the whole village chanted.

"Did he come?"

"He did not come."

"Did he go?"

"He did not come; he did not go; none saw him."

So passed the stranger—a nothing.

Up in Rimi-Rimi, the city of the Great King, the evening came down redly, and the seven hills of the city crawled and swarmed with life, for in the shallow about which the squat hills rise the big fire of the king was burning, and his carved stool stood before the hut of his chief wife. Here in the shadow of his palace the Old One had delivered justice for innumerable years. He was older than memory, and some said that he had begun with the world. Yet it was agreed that he was not so old as the Devil Woman of Limbi, who was immortal.

As the sun's edge tipped the mountain, his war drums volleyed their summons, and K'salugu M'popo the king showed his gums. Thus he smiled always when the drums rumbled, for was not the skin of one the skin of Oofoobili, his brother who had risen the Territories in rebellion against him, and was not the other the skin of M'guru, the Akasava chief who had carried off the king's daughter?

The crazy grass huts that covered six of the hills—the seventh was bare and sacred to the processes of the king's justice—gave forth their members to the number of fifty thousand, the aged and the young and those who were dying, these latter being carried on litters, for when the Old King's fire burnt and his war-drums rumbled, the searchers of the king's guard slew all that was living within the huts.

They sat in a great half-moon of faces, divided straightly by five paths that radiated from the king's chair like the spokes of a wheel, so that his ministers and servants might have free access to evil-doers, and witnesses a clear way to the throne, and they sat in a solemn unbroken silence,

An hour, two hours he kept them waiting and then, without warning the drums ceased and sixty thousand hands were raised in salute—even the hands of those in the litters on the fringe of the great assembly being held up by their friends and relatives. The Old Man came from his white hut and walked slowly to his chair. There was a grizzle of grey at his chin, and the faintest powder of white on his bony head. About his shrunken form was wrapped a cloak of native silk of a certain colour.

Helpers threw great logs of gumwood on the fire, and it blazed up with a roar.

"Let my wives be numbered," said the Old Man with a cracked voice, and his minister Lubolama, Chief of the Fongini, seni-seni, and commander-in-chief of his armies, walked behind the king's chair and counted the king's wives, for they were not exempt.

"Lord, all your women are here."

The Old King nodded. He sat with his foot on a stool, his elbow on his knee, and his chin resting on the palm of his hand, looking at the fire moodily, and thus he sat for a long time, and none dare break the silence.

"Let her come," he said at last, and Lubolama made a signal.

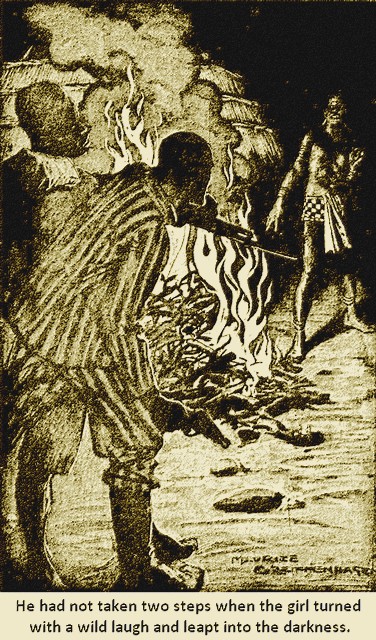

Through the last of the lanes came four of the king's guard, and in the midst of them a prisoner Presently she knelt before the king's majesty a slip of a woman, obviously a foreigner, for her nose was straight, and her lips were thin, and her skin of a light chestnut colour.

The king stared down at her through the slits of his eyes. "O Woman," he said, with the halting deliberation of an old man, "this night you die."

"Lord, I do not deserve death, for I have done no harm to your people," said the girl. "Also I am not of your race."

The king chuckled and half-turned in his chair.

"He was not of my race, and yet he died." And she lifted her eyes and saw by the king's hut a straight pole where something hung—something that was dried and shrunken by the month's sun, something to which thin rags still hung. She shivered and cast down her eyes.

"He was not of my people, yet he came. By the road over the mountains he came, a little chief showing him the way."

He stroked his chin thoughtfully.

"Now, it is not good that I, the Great King, shall be betrayed by little foreign chiefs who show the white man secret paths to my country, and I have waited very long, woman, before I sent my young men into your land to take you and bring you to me. And they waited long also, for they are young and cunning, and presently, when your little chief had gone to the forest, hunting, they came upon you at night and brought you from the land."

The girl licked her dry lips and said nothing, for her abduction was ancient history to her.

"Therefore I set these two great sticks that you and your man might follow together the way the white lord went."

Again she raised her eyes and saw for the first time in the gloom two great poles which flanked the pitiable Something which once had been a loving, laughing, thinking man. She drew a long breath.

"My lord, you have not got him," she said with spirit, "for he is too great for you and too cunning. Your young men would not cross the mountains and meet his army on the plain-by-the-forest."

The Old King chuckled again and waved his hand. "He comes!" he said. "He comes!"

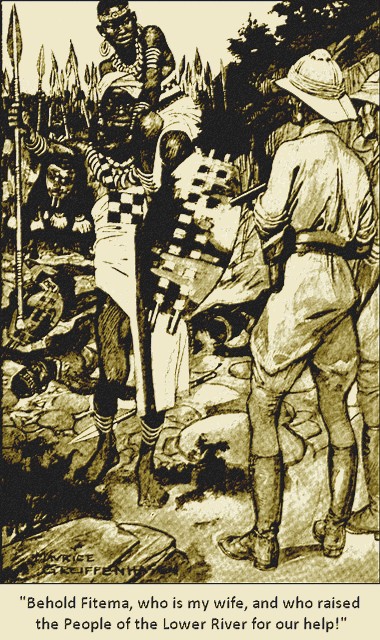

The girl twisted her head and stared. Down one of the lanes a tall man was striding toward her unattended, his wicker shield on his arm, the steel tips of his fighting-spears glittering in the light of the fire.

"Lord!" she wailed, and ran to meet him as he reached the clear space before the king, falling at his feet and clasping his knees.

Instantly four giant guards were about him, but, tall as they were, he topped them by inches. He made no resistance, but offered his shield and his spears. Unarmed he came before the king's face, holding the girl by the hand.

"Lord," he said boldly, "what shame is this you put upon me and my master? For behind me are the spears of a million men and guns that say 'ha ha', and men drop dead."

The king's eyes were hardly visible now, so tight were his lids held together. He screwed his neck to look up at the big man's face.

"There is no king in this land but K'salugu M'popo," he said. "Where is M'siti?" he asked, and the guards and ministers who stood about him chanted:

"His hut is broken."

"Where is Goobini, the mighty one?"

"His hut is broken."

"Where is B'lili and all his forest of spears?"

"His hut is broken."

He was wide-eyed now, and there glared within their depths a cold fire.

"This night, little chief, you die," he said, "for you sent a white spy into my land that you might poison me and my people. And, because of you, Sandi is come to the land with his soldiers. And, chief, you shall not see him or tell of the white man Tomini. Therefore by my great cleverness have I brought you here, where Sandi cannot come because of the swift waters. O cunning one, where is your cunning now, for did not I lead you here without a spear behind you when I took your woman?"

The big man nodded his head.

"Lord, that is true." he said simply. "This woman is life to me, and I would rather die at her side this night than live with my people. This also Sandi will know, for I left him a book saying I was gone into your country. But, lord, because I come in peace and love I brought you these."

He took from his waistband a heavy bag, and, kneeling down, spilt the contents at the king's feet. They were coins of gold and silver, and they made a little heap.

The king looked at the presents with avaricious eyes, for he knew that these strange round pieces brought many desirable things from an outside world, and that from the Portugisi he could buy square bottles full of hot delight. Only for an instant did he waver, then he made a gesture, and Lubolama, stooping, scooped up the coins and, walking to the edge of the fire, threw them in, and the big man stiffened. The king had burnt his gifts before his eyes, and that meant death.

He turned to the woman at his side and caught her up in his arms, speaking to her in a language which the king did not understand. Then almost instantly they were torn apart and thrown to the ground. The big man made no resistance. The gangways now were blocked by armed men, and behind the king's hut the circle was completed by rank after rank of guards.

Those whose office it was to sacrifice bound wrist and ankle, and, lifting them up, laid them with their feet at the king's feet. Above them stood the sunburnt naked figure of the executioner, his broad knife in his hand.

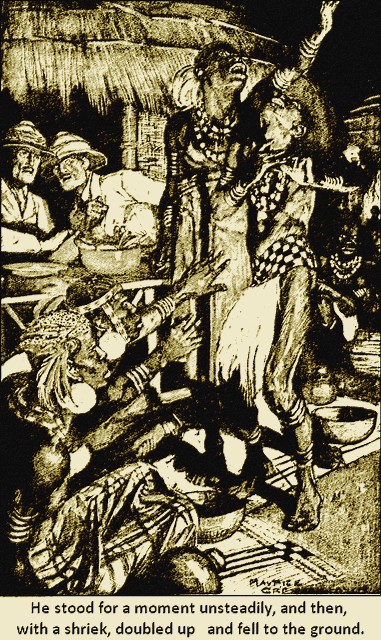

"Speak well of me to the spirits, to the ghosts, and to the great ones of the mountains," the king repeated the formula monotonously, "also to M'shimba-M'shamba, and speak kindly of me to all ju-jus—strike!"

The executioner measured, touched the throat of the big man tentatively with his knife, as a golfer all but touches the ball he is about to strike, and then raised the keen blade about his head.

And there it remained, for a soul-piercing shriek, a terrible sound which ended in a howl, momentarily paralysed all within its hearing. The king half-started from his carved stool, his mouth agape, and, regardless of the doom which awaits all who take their eyes from the king's face, fifty thousand heads turned in the direction of the sound.

"O Lubolama, what sound was that?" asked the king in a high voice.

"Lord, I do not know," said the trembling man.

It was the captive on the ground, his eyes blazing, who might have supplied the solution, but an interruption came from another quarter.

Clear in the light of the fire a group of men were walking down one of the lanes toward the king's chair, and the armed guard melted out of their way. Two were native soldiers, carrying something which they deposited within a few paces of the dumbfounded king's feet, the other two were indubitably white men, and it was the smaller who spoke.

"O king," he said, "know me."

"Who are you, white man?" The king found his voice with difficulty, for he knew.

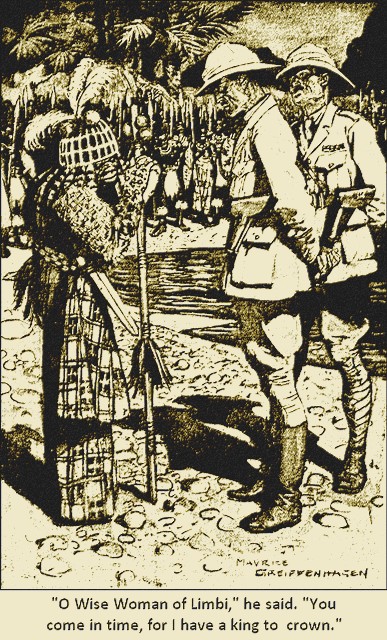

"I am he they call Sandi of the River, and I have been sent by my king to be the overlord of these lands, and I have brought you a rich gift which will bring happiness to you, and shall protect me from evil."

The king's eyes strayed slowly from Sanders's lean face to the thing at his feet. It was a hideous figure straddled on three scarlet legs, and surmounted by a head of peculiar hideousness. The pear-shaped body was painted with flaming designs, and the big wooden head bore the tribe marks of the Tofolaka people, and had ears which the Houssas had used for handles as they straightened the monstrous, pot-bellied thing under the king's gaze. Nor was this all the decoration, for stuck in the hideous wooden head were four small flags which were unfamiliar to the king.

"O Sandi," he said—he was still shaking as much from the effect of the Zaire's syren as from this tremendous visitation—"I—"

Again that shrill shriek arose, sobbing and wailing and echoing against the high bluffs of the plateau on which Rimi-Rimi was situated, and the king shrank back in his stool.

"I hope to Heaven Bones isn't overdoing it," said Hamilton in Sanders's ear, and Sanders shook his head slightly.

"What was that?" whispered K'salugu M'popo, the Old One.

"That was my spirit, king." said Sanders. "Now I have come to talk to you as king to king, and I have brought you a wonderful present, and there are many things I would say to you."

He had seen the captives as he came in, but had not looked down at them.

"First, O great one," he said, "there shall be no sacrifices in this land." And he stooped down swiftly and with his knife cut the grass ropes which bound the two captives.

He did this so quickly and so skilfully that the old man was startled to silence.

"Lord!" whispered the big captive, and Sanders nearly dropped his knife.

"Bosambo, by heavens!" he gasped. "Go quickly, Bosambo," he whispered; "there is death in this city."

By now the king had recovered himself.

"Sandi," he said harshly, "you have come to my city, but who knows when you shall go?"

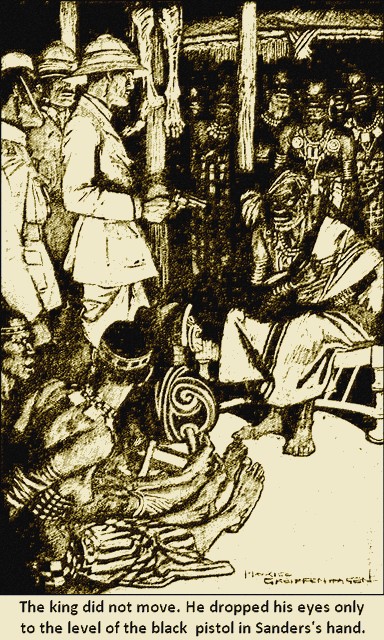

"I alone know, king," said Sanders softly, "for I go now, and, if you move, my little gun which says 'ha ha' shall spit at your stomach, and you will have many days of agony, and none shall give you ease until you die."

The king did not move. He dropped his eyes only to the level of the black pistol in Sanders's hand. Had the white man whose dried skin now rattled against the crucifix come so into the king's presence, he might have lived—for a while—but they had pulled him down at the entrance to the city.

"O Sandi," said the king mildly, "I will do you no harm, and you shall have a hut in my city, for I see you are a great one and very cunning. Who but a man of magic could walk through the swift waters? As to this man and woman—"

"They come with me," said Sanders equably.

The king hesitated. "Let it be," he said.

Sanders gave an order and started to back away, and Bosambo, gathering up his wicker shield and spears, which lay where they had been thrown, covered the rear.

"O king," said Sanders, in his deep Bomongo tongue, "see I walk like a crab, and all the time my little gun is looking into your heart, and if you move or speak you will die."

The king said nothing, and the little party moved backwards through the clear alleyway, and nobody stopped them. They had reached the lines of litters before Sanders turned.

"There is no possible chance of getting to the boat," he said. "The old ram will remain friendly so long as he's covered by my gun. As soon as he gets into the hut, we shall have the whole guard after us."

"Can't we make the landing and the boat?"

Sanders shook his head. "That would be impossible now," he said. "Look!"

A line of figures was leaping into the bush. He saw them dimly by the flickering light of the king's fire.

"They are going to head us off. It is the hill of execution, as I expected," he said. "We can hold that for an hour."

"And after?" asked Hamilton dryly.

"All things are with God," said Sanders piously, as he raced through one of the flimsy suburbs to the bare hill where no house stood and where only the bones of innumerable martyrs lay.

"They'll hardly come to the hill tonight," he said breathlessly, as they gained the top; "There are too many ghosts about even for the king's guard."

From where they stood they looked down into the basin, and could see the commotion their escape had produced. Through his night-glasses Sanders saw the old man still sitting in his chair of state, and chuckled.

"I'm afraid Guy Fawkes isn't going to do us much good," said Hamilton. "But the old man seems to be examining our god with three legs."

"Wait," said Sanders.

"Suppose the Old King isn't impressed by the unburnable Guy?" asked Hamilton.

Sanders did not reply. From the basin below rose a hubbub of sound. The people were scattering, and long orderly lines of soldiers were filing before the king.

"I thought it was worth trying," he said, "and it struck me at the time as rather amusing." And he chuckled.

"What is it supposed to be, sir?"

"The ju-ju of the League of Nations," said Sanders, without a smile.

The Old King had risen. They saw that from the hill.

"O people," he was saying, and the sound of his voice came faintly and unintelligibly, "O soldiers, you have seen this night a shame upon my house. Now you shall go and seek out these devils, and tomorrow we will have a great palaver."

He pointed to the three-legged idol, and two of his men lifted it and threw it upon the fire.

Bosambo needed no night-glasses. He stood at Sanders's elbow.

"Lord," he said in a whisper, "they have burnt your present, and that is death."

"So I think," said Sanders, and as he spoke there leapt from the fire a white tongue of blinding light, and there came to their ears a roar louder than any man had heard, and a shock that almost threw them from their feet.

"Good heavens!" gasped Hamilton. "What was that?"

"That was the body of Guy Fawkes—an aeroplane bomb!" said Sanders softly. "Somehow I didn't think it would burn very well."

He stood looking down at the havoc and the fury of flame which sent thousands wailing to the edge of the river.

"Do you know, Hamilton,"—he turned to the other with great seriousness, for the niceties of official matters worried Sanders—"I'm rather troubled about those flags I stuck on Guy Fawkes's head. Is America in the League of Nations?"

FROM the city of the Great King to the city of Bubujala is a day and a night's journey, but Balaba, sometime the Old King's servant, made the journey in a night, and fell, smothered with dust and half dead with thirst, at the feet of Fomba, paramount chief of all the Bubujala people. Fomba was sitting in his palaver house amidst his counsellors and headmen when the messenger staggered from the edge of the forest and wearily climbed the hill on which the palaver house was situated.

"O Balaba," said Fomba shakily, "what lies do they tell of me to the Great King?"

He had reason for apprehension, it seemed, and when the breathless messenger did not reply—for in truth he could do nothing but pant—he went on:

"All my people here know that I have lived very humbly in the king's sight. I have sent him my gum and my rubber to the last load, and if any man says that I have spoken against him, I will sew a snake in his mouth."

By this time Balaba had recovered his voice.

"Lord," he said hollowly, "the king is dead!"

"Waa!" gasped Fomba, and sat down heavily.

"The night before the night there came two white men and some soldiers," said Balaba rapidly, "and another white man sat in his great canoe, which makes a noise like a devil, and the two came bearing a ju-ju of great strength, and this they placed before the Old King."

"Did the Old King chop them?" asked Fomba, interested.

"No, lord, he did not chop them, because they had in their hands the little guns that say 'ha ha'."

Fomba of the Bubujala looked at his counsellors, scrutinizing each face.

"The Great King is dead," he said softly. O ko! And these white men killed him, and you chopped them quickly?"

"No, lord, we did not chop them, for the white men had gone away, taking with them two people—the chief of the Ochori and his woman—before the killing order came, for the Old King was afraid of the little guns which the white men carded. But when they had gone off, he sent his fine regiments to cut them away from the river; also he sent his women away, that being his custom when he made a war palaver."

Fomba nodded impatiently as the man stopped to take breath.

"Lord." Balaba went on impressively, "these men brought a powerful ju-ju with a terrible face, and this they gave to the king, saying that it would be good for him, and when they had gone, running swiftly, it was the order of the king that the gift should be burnt."

His voice faltered.

"Lord," he said in a hushed voice, "who knows what great ju-ju these white men brought? For no sooner had the king put this shame upon them, casting it into the fire, when lightning struck with a terrible noise, and many of the king's guard were thrown down and killed, and all the king's big huts were swept away by a mighty wind, and the houses also on the hills, so that there is nothing in Rimi-Rimi but leaning walls without roofs."

He did not explain that the powerful ju-ju had been an aeroplane bomb which Mr. Administrator Sanders had brought all the way from London, that the terrifying face had been created and painted and its steel legs riveted by an enthusiastic officer at the War Office, because this he did not know. The chief stood in dismayed silence.

"O ko!" he said. "This is bad news, Balaba, for if the white men have come, and they have a ju-ju so powerful—"

"Lord," said the man eagerly, "where he stood, and where the fire was, there is now nothing but a great hole in the ground in which twenty men could lie."

The chief shook his head and thought long, for he was a cunning man, though no great warrior.

"What of Masaga, the king's son—did he die also?"

"Lord, no," said the man. And then, standing first on one bare foot and then upon the other, to evidence his embarrassment, he blurted forth: "Lord, who is king now of all these people? I think it is you, for the king's son is a fool."

Again a silence long and, for the messenger, ominous.

"Go, Balaba, to my hut," Fomba said. "But tell me first—what of the white men, and where are they now?"

Balaba was dusting his hands in proof that his mission was done, a custom of the folk of Bubujala.

"The soldiers sit in two deep ditches near the landing-place, and before them they have made a fence of wire which is filled with sharp and evil pins," he said; "also they have many guns of great size, and the people, who are afraid of them, do not go near them."

Fomba nodded his head.

"Go to my hut, Balaba," he said kindly enough, and the man trotted off.

The chief waited until he was out of bearing, and then turned to his own hunter.

"Go follow Balaba and chop him down," he said. "Let no man hear him speak, for it is good that the city should not know the truth, if he spoke the truth. And if he spoke a lie, then I go to our lord and say that I killed him because of his wickedness."

The hunter slipped silently in the trail of the unconscious messenger, and in full view of the city and of the counsellors upon the hill he struck Balaba down and Balaba went to his death, not knowing how.

All these things Sanders heard later. For the moment he was less engrossed in the tragedy which was occurring in the depths of the forest than in the prospect of tragedy nearer at hand. He sat under the white awning of the Zaire II and sipped a cup of cold coffee, his eyes never leaving the landing-place, where forty Houssas overawed the fifty or sixty thousand people of Rimi-Rimi.

The Great King's own territory, and that of which for hundreds of years his family had been titular kings, was bounded on two of its sides by the river, which here took a wide bend. Rimi-Rimi and the country about was set upon a plateau, the bluffs of which fell steeply to the water and presented no accessible or scalable point, save at the landing-spot opposite which the Zaire was anchored. Here the uncompromising level line of the cliffs sloped into an obtuse V.

Before him squatted one N'kama, and this philosophical prisoner, though there were handcuffs about his wrists, was a small chief whom Sanders had noted, on the night of his arrival, as being of the king's suite.

Sanders brought his eyes back from the two posts which were held by Hamilton and Bones, and stared coldly down at the hunched figure at his feet.

"N'kama," he said, and he spoke in the language of the Upper Bomongo, "for twelve hours you have been on board my fine ship, and though all men say you are a great talker, yet you have told me nothing."

"Lord," said N'kama, shifting a little uneasily under the gaze, "I do not think that you will go alive from this country; but if I speak to you of the great secrets of my people, I shall die most surely, and my skin will hang where the white man's skin was hanging when my lord took it down and put it in a hole in the ground, saying certain Mysteries from a book."

"O ko," said Sanders softly. "Then it seems, N'kama, that you are worse off than I, for I may yet escape; but it is certain that you are a dead man unless you speak to me, and you are as surely a dead man if you do! Now, I think they will kill you more painlessly upon the land than I shall, for I shall hang you up by the heels on two sharp hooks and I will light a little fire under your head."

The involuntary grimace on the prisoner's face told that the threat had been duly appreciated.

N'kama was silent, and when he did speak, it was to recall some of the legendry which was associated with Sanders's name.

"I have heard of you, lord, from Akasava prisoners we have taken, and they say you are most cruel, and that you have no pity in your stomach. Often I have heard the drums of the Lesser People speaking of Your wickedness. The prisoners said you were dead, but now it seems you are alive, and my heart is full of sorrow."

Sanders did not smile. There were times when he doubted if he would ever smile again, and there was reason for his doubt, could he but foretell the future.

"You shall speak," he said.

"Lord, I cannot speak," said the man, "and I wish to go back to my house, for I have a wife who is very sick. Also I would not be here," he added naively, "but that one of your soldiers hit me on the head and then struck me in the back with his spear."

Sanders knew the value of those intervals of silence which mean so much in native palavers, and resumed his scrutiny of the beach. Two nights before, in the confusion occasioned by the explosion, he and his companions had not only made their way through a panic-stricken people, but in the night he had established a bridge-head which served the double purpose of covering the Old King's city and maintaining the inviolability of his steamer, for the canoes of Rimi-Rimi were beached to the left and right of the gap.

"Sandi," said N'kama, having apparently digested the situation, "what can I tell you that you, so wise and wonderful, and Bosambo, the chief of the Little People, who is more cunning than ghosts, do not know?"

"First you shall tell me about the white man who came here five and five moons ago."

"Lord," said the other frankly, "there is nothing to tell, for he came and was chopped by the Old King's hand, and we had a great feast, and hung his skin upon the trees, as is the custom, for we people are very proud, and do not like the white man who is neither white nor black, and for this reason the Devil Woman of Limbi, who is very holy and a woman of great mystery, even she spoke death for white people in the days of Fergisi."

"Fergisi?" asked Sanders, with a frown.

"He was white also," nodded N'kama, "and a God-man; also his woman, she also was white, and the small woman was white, having hair which was very ugly, being the colour of corn."

Sanders sat up. In the excitement of the past days he had forgotten the murdered missionary and the horror of his daughter's fate.

"How did they die?" he asked softly.

"Lord, I do not know," said the man, "for I was hunting. But the Devil Woman of Limbi came to the king and spoke for his life, and it was a terrible happening, for the old Devil Woman has never left the mountains for twenty years; but because she hates white people, the king's guard came upon the house of the God-man and slew his small woman. But his own woman ran away in a little puc-a-puc, and it is said that she died in the swift waters."

"And what of Fergisi?" asked Sanders.

"Him they took to Limbi, where the old and holy woman lived, and she put her sword under his chin and cut his throat."

He said this so calmly and in so matter-of-fact a tone, as though he had been discussing some amusing social event, and Sanders, despite his experience, shivered.

"Who is this woman of Limbi?" he asked.

The man looked right and left and lowered his voice.

"Lord, she is older than the gods and the ju-jus, and wiser than the great ones of the mountains. They say she has lived a thousand years, and buried her own mother under Limbi, piling up the rocks upon her until they reached the sky. Lord, she is terrible," he said earnestly, "and all men fear her."

He spat left and right in propitiation.

"Therefore I say, lord, that you will never leave this country, because she sends her tchu to guard our people."

"Tchu!" repeated Sanders, with a puzzled expression, for this was a new word to him.

"Lord, tchu is a ghost who walks so that none see him."

"Where may I see this terrible woman? asked Sanders.

"She will come," was the surprising reply.

"She will come?" repeated Sanders. "O man, I do not understand you."

"Lord, she must come when we make the new king, for she alone knows the mysteries. It is said that she made the Old King, whom your lordship made to vanish, and all men know that he was older than the hills!'

"So she will come, will she?" said Sanders gently, and beckoned the sentry. "Take this man below, Ahmed," he said. "Let none speak to him on your life."

"On my head and my soul," said the Houssa conventionally, and led the passive captive away.

Later in the morning Sanders withdrew his posts from the shore. His force was too small to split, and Fomba might come in considerable strength. When they sat at tiffin on the after-deck of the Zaire, Sanders related his talk with the man.

"Who is this woman, anyway, and where is Limbi?" asked Hamilton.

"I rather suspect it is the native's word for Mount Limpisi, and if that is the case, it must he the mountain we can see, or we saw as we were coming up the river."

Bones, who had come aboard hungry, had in consequence kept silence; but now he rolled his table napkin briskly and smirked, and Hamilton, seeing the smirk, groaned.

"Bones has got a suggestion, sir," he said in despair.

"Dear old Ham is unusually right," said Bones, smacking his lips. "It's one of the grandest little ideas, sir, that's ever penetrated my jolly old noddle. In re Devil Lady, why not chop off her naughty old head?"

Sanders looked up.

"You can't kill a woman in cold blood," he said. "Besides, she might take it into her head to help us along. You never know. One hates to miss any opportunity," he said half to himself. "But I can't reconcile my conscience to what might be a senseless assassination. If she gives trouble, and if she does instigate the people against us, that is another matter."

His smile was unpleasant, and Patricia Sanders would never have recognized the quiet, soft-spoken man who picked caterpillars off his roses with tweezers in this hard-featured arbiter of Fate.

"What we have to expect," he said, "is for the various territories that make up this kingdom to start warring with one another, because I rather think there are about a dozen rival claimants to the throne. There's Lubolama, chief of the Fongini; there is Fomba, chief of the Bubujala; there is the chief of Kasala and friend Kabalaka, who, I suspect, is not without his hopes of succeeding; he was a cousin of the king."

"Who wasn't?" said Bones. "Who wasn't, dear old sir and Excellency? And perhaps this naughty old lady, the girl of the Limbi lost—if you will pardon the jest—perhaps she's his aunt. You never know. Why, I remember a dear old friend of mine—"

"Let us confine ourselves to local barbarians, Bones, if you don't mind," said Hamilton wearily.

"Rude, Ham, rude!" murmured Bones, shaking his head. "Rude, old officer, very rude indeed, deuced rude!"

"Well, there we are," said Sanders, leaning back in his chair with a wry face. "Six months we have to settle this territory, and I rather fancy that we are going to be very fully occupied."

It was two days later that the first of the claimants came upon the scene, and never was there a claimant less aggressive, more respectful, more frank and considerate in his attitude to all the world than Fomba, chief of the Bubujala. They saw him came in the dawn, twenty-four canoes that came down the river six abreast and keeping perfect line, and the whole crew and company of the Zaire stood to arms, anticipating an attack. But the canoes swept round the bend and made for the shore, and at ten o'clock that morning Fomba presented himself on the ship.

He was a big man, broad of shoulder and inclined to rotundity. His cheeks were round and his eyes and expression intelligent. Unerringly he came straight to Sanders and saluted in the fashion of the territory.

"Lord, I see you," he said.

"I see you, Fomba," said Sanders, who had had tidings of the visitor.

"Lord, I come with peace in my heart," said Fomba, "and I bring you salt."

He turned to a waiting servant who carried a bowl, and scooped up a great heap in his two palms. He offered it to Sanders, who wetted his finger-tips, touched the salt and tasted it, an action which the guest imitated.

"Lord, I have come along journey to see you," said Fomba, "though my heart is heavy because of my cousin and my nearest relation. He has been smitten by your great ju-ju."

Sanders's eyes never left the man's face.

"It is good that you should come, Fomba," he said. "I know that your stomach is sorrowful because the Old King is in hell, but you tell me news when you say you are his nearest relation, for is there not a son?"

"Lord, that son is mad and silly, as every man knows," said Fomba eagerly.

"And is there not a brother, Lubolama, and yet another cousin? I do not dwell in this country, and yet my spies bring me news, and I have heard these things."

"Who knows his father, and are not uncles as many as goats?" quoth Fomba easily. "And who shall say how nearer one person is than another? Yet it seems to me, lord, that I who am here am nearer than they who are far."

"You cannot measure right with a string," said Sanders, giving proverb for proverb. "Now, I tell you this, Fomba, that I am not strong for you. For if I set you up in the king's place, all manner of men will hate you, such as Kabalaka and Lubolama and the many sons of the Old King. Also there is a certain son of the king's second wife who sits with the evil men of the Bad Village."

Fomba looked from Sanders to the shore, and back to Sanders again.

"Lord, why do you come to these lands?" he asked bluntly.

"To bring the law," said Sanders.

Now, in the Bomongo language there is only one word for "law" and "power", and for unbiased "justice" there is no other word than "vengeance". So for "law" Sanders used the word 'lobala', which means "right" as distinct from "wrong".

Fomba was frankly puzzled. "Lord, what is right?" he said. "What you do, or what I do? When two nations are warring, is he not right who has the most spears and the bravest young men?"

Sanders hid a smile. It was queer to bear the paraphrase of Napoleon's dictum that Providence was on the side of the big battalions from the lips of an untutored savage.

"What is right, lord?" repeated Fomba.

Sanders had need to go back to old Rome and quote as best he could the greatest of jurists.

"This is right, Fomba," he said "—to keep faith, to harm none, and to give every man his due."

This Fomba pondered.

"Lord, how can a man keep faith and harm none?" he asked. "For if I keep faith with the king's sons, I harm myself, and if I give Masaga his due, then I rob myself of mine."

Sanders watched the canoe in which Fomba left for the shore with a stony face.

"That man is going to give us trouble, Hamilton," he said, turning to his lieutenant.

"Why not set him up?" asked Hamilton quietly.

Sanders was rubbing his chin—a sure sign of worry.

"The Old King named his son before the great council of the land," he said. "The traditions here are much stronger than in those old territories of ours, Hamilton, or I'd retire his majesty like a shot. But to do that now means to bring the whole of the council against me; for whatever might be the individual ambitions of the chiefs, and although they all separately may desire the throne, yet it is certain that if I put one of them up, I should have the others in arms against me, and probably a rising here in Rimi-Rimi itself. We are facing problems now which we've never met," he said seriously. "The sooner we get Masaga crowned or anointed, the better for all concerned."

"When does the Devil Lady make a dramatic appearance?" asked Hamilton.

"Not before a week," said Sanders. "She, apparently, is the custodian of the insignia, whatever it may be."

"A week?" said Hamilton. "Anything may happen in a week."

What did happen seemed the most innocent of all possible occurrences. Fomba gave a great feast in honour of his kinsman and sovereign. It was to be a feast of a thousand pots.

"That's a new idea, though the N'gombi people have some similar method," said Hamilton, bringing the news. "Every family brings its own fire and its own cooking-pot, and the philanthropic Fomba provides its contents. And Fomba desires that we should join the royal circle."

"I think not," said Sanders decidedly. "I draw the line at native meals."

"I conveyed that fact to his nibs," said Hamilton. "Really, he is the most adaptable man. He said we may all dine in the white style, and be of the royal circle, though not in it."

"A rum bird," said Sanders thoughtfully. "I'll think it over."

It was decided that Hamilton should go alone to the feast, but at the eleventh hour Sanders changed his plan.

"Bones," he said, "I'm going off with Hamilton. Keep a searchlight on the beach, and let the men stand to arms."