RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

Roy Glashan's Library. Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

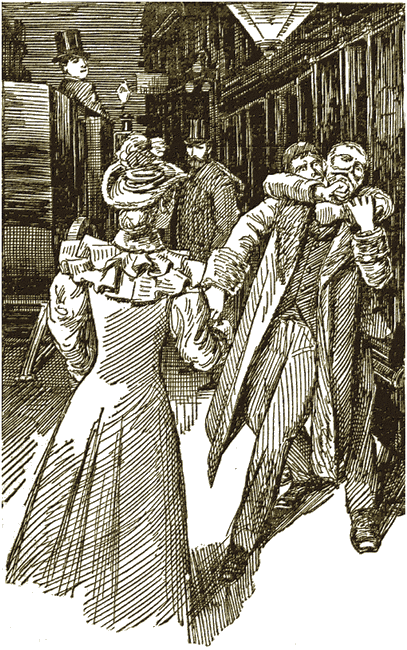

Frontispiece

A pair of huge arms were around his throat holding him as though in a vice.

"PORTER!"

"Yes, sir."

"What time does this train leave Liverpool?"

The man who had a trolley-load of lamps to clean before he went off duty, and who was not in the best of tempers, was on the point of giving a curt reply when he caught the gleam of silver between the questioner's fingers. He pulled up short and touched his hat.

"Should have left at five, sir, but she was 15 minutes late. She's bringing some boat passengers, I think, sir."

His questioner, a tall, black-bearded man, heavily clad in a long ulster, nodded, and consulted a piece of pink paper which he held in his right hand.

"I have a telegram here from a friend handed in at the Alexandra Docks at 4.25," he remarked. "It says: 'All well. Just through customs. Trying to catch five o'clock from London and North-Western Station.' Would he do it, do you think?"

"Four-twenty-five," the man repeated doubtfully. "Was he on the Cunarder, sir?"

The gentleman—his voice and dress seemed to denote that he was one—nodded.

"Yes, he was on the Umbria."

"He's almost certain to have caught it then, sir. It was for some Cunard passengers that the express was put back 15 minutes. It's just about 50 minutes' drive from the Alexandra Docks to the station. You'll find your friend on this train right enough, sir. The agent who met the Umbria telephoned up from the docks to hold the express, as there were some gentlemen who particularly wanted to get through to London, and the Midland would have run a special if our people hadn't done it. Thank you, sir. Much obliged, sir."

The porter touched his hat and passed on with his lamps. Before he had gone a yard, however, he looked round.

"There goes the signal, sir. She'll be in in one minute."

The man in the ulster nodded and threw away his cigar, which had long burnt out. The night was cold, but there were great drops of perspiration breaking out upon his forehead, and his face was curiously pale. He took out a silk handkerchief and touched his temples lightly with it. Then he set his teeth hard and frowned.

"I'm getting as nervous as a woman," he muttered.

"What a d——d fool I am! The thing's as simple as A B C! Pluck up heart, John Savage! You're as well disguised as any actor that ever trod the boards! What is there to fear? Be a man!"

He lit a fresh cigar with fingers that trembled as though he were on the verge of an ague.

"Bah! I must get over this. The thing's got to be done! It is the consummation of everything—of my life's work, of my whole desire—and it is so simple too! I am prepared against every emergency. I must succeed! There is no weak point in the whole chain! Once more, John Savage, be a man!"

He thrust his hands deep into the pockets of his ulster and walked restlessly up and down. The express had been rung in from the signal-box, and the broad arrival platform was crowded with a motley group of railway porters, hotel servants in their smart liveries and peaked hats, and a sprinkling of men and women, who had evidently come to meet their friends. He took up his stand a little apart from the rest, and waited.

The minute seemed a long one, but it came to an end. There was a slight commotion in the waiting crowd. The strangers stood still and the porters left off chattering in little groups and stood on the alert. Two red fiery eyes came flashing along the track and a moment later the express swung smoothly along the platform side.

Fortune favoured the man who had called himself John Savage. When the train came to a standstill, he found exactly opposite to him, leaning head and shoulders out of a first-class carriage, and eagerly scanning the faces upon the platform, the man whom he had come to meet. He threw away his cigar, and advanced at once to the carriage window, standing aside only for a moment while a porter threw the door open.

"Mr. Hovesdean, I believe," he exclaimed, holding out his hand. "My name's Savage—John Savage! I daresay you've heard Lord Harborough speak of me. He asked me to come and meet you."

The new comer returned his greeting courteously enough, but evidently without any recognition.

"I can't say that your name is familiar, but I'm very glad to meet you, Mr. Savage," he said, in a pleasant, but rather high-pitched tone. "I hope Lord Harborough is well. Is he here?"

Savage shook his head.

"No; he was awfully sorry to be prevented—I'll tell you all about it in the carriage. Have you got all your small things out?"

Mr. Hovesdean turned round. For the first time Mr. Savage became aware that a tall, fair-haired girl was standing in the interior of the carriage. He could see nothing of her features under the thick gauze veil she was wearing, but her long, perfectly-fitting travelling ulster revealed the lines of a slim, graceful figure.

"Everything's out, papa," she said, in answer to his look. "Why isn't Reggie here?"

"This gentleman will tell us presently, dear," Mr. Hovesdean answered, taking her hand and assisting her to alight. "Mr. Savage," he continued, "will you allow me the pleasure of introducing my daughter to you, Miss Sadie Hovesdean. Sadie, this is Mr. Savage, a friend of Lord Harborough's."

Mr. Savage's behaviour was a little extraordinary. He stood quite still, and forgot even to remove his hat. For a moment he seemed like a man who has received a sudden blow. As a matter of fact, he was completely taken aback. His plans had been laid with the utmost care, but the possibility of anything of this sort happening had utterly escaped him. His brain was in a whirl. He could not even think—speak he dared not. The idlest sentence might betray him.

Mr. Hovesdean laughed. "You see the effect you're going to produce upon the Britishers, Sadie," he said, good-humouredly. "It was a little too bad, perhaps to spring such a surprise upon Lord Harborough and all of you, but really I only made up my mind a few hours before the boat sailed to bring my daughter."

Mr. Savage recovered himself in a measure. He took off his hat and bowed in a dazed manner.

"Then Reggie does not know—"

"Not a word," Mr. Hovesdean interrupted. "It's a surprise for him; now I guess I'd better see about those trunks. Mr. Savage, I'll leave Sadie in your charge for a minute."

Mr. Savage was delighted. He turned to a man who was standing like a dark shadow behind him.

"Put these smaller things in the brougham, Mason," he ordered, "and then show Mr. Hovesdean—that gentleman standing there—where the cloak-room is. Your larger trunks had better be stored for to-night, I think," he remarked, turning towards his companion. "You're coming will naturally alter the arrangements. To-morrow you will go to Lady Mary's, of course."

"Just as you and papa think best," she answered. "Tell me, Mr. Savage—Lord Harborough isn't ill, I hope?"

They were standing underneath the lamp, and he could see something bright glistening underneath her veil. She was bitterly disappointed. All the way over she had dreamed of this meeting, so unexpected on his part. He would come to the station—perhaps to Liverpool—never dreaming of seeing anyone but her father, and then she would step out and hold out her hands, and, ah, how glad he would be. She had leaned over the side of the great steamer as it thundered its way across the Atlantic, and with her idle eyes gazing on the sea. She would think of the times when they had met after only a day's separation; how his face lit up and his eyes shone bright with joy; and then how grave and sad he had been at parting, even though the separation was to be but a sort one and its end was to bring her to him for good. Her heart had ached many a time when she had thought of that dreary morning. To-day was to have wiped out its memory for ever, and to-day so far was a very great disappointment. There had been just a faint, delightful hope that he might have run up to Liverpool! Alas, that hope had been futile. She had laughed it off bravely, however, when her father had rallied her, but this was different. They had sent their telegram from the docks, she had seen it despatched herself, telling him even by what train Mr. Hovesdean was coming. All the way down she had kept looking at her watch, and saying to herself in three hours, in two hours, in one hour, in twenty minutes, I shall see him, see his face change from blank surprise to bewildered joy, feel the clasp of his hands, perhaps—these Englishmen were bold lovers—even he would kiss her. And after all there was only this stranger to meet them—a man for whom, from the moment of stepping out of the carriage, she had formed a woman's unreasoning and instinctive dislike. No wonder Mr. Savage saw what he did under her veil.

"No, he isn't ill," he answered. "Nothing to be alarmed about at all. Fact is, he met with a slight accident this morning. He was thrown out of a hansom and hurt his ankle. That is why he sent for me, and asked me to meet you."

"Oh, I am so sorry," she exclaimed. "Poor Reggie," she added softly. "Papa, have you heard about Reggie? He's hurt his foot."

"I'll tell you what there is to tell as we go," Mr. Savage said, walking between them down the platform and out into the yard. "Here is my carriage. The man has put all your smaller things in."

"Where are we going to—the hotel?" asked Mr. Hovesdean. While Mr. Savage handed his daughter in.

Mr. Savage smiled. Somehow it was not altogether a pleasant smile.

"That was what I had intended," he said, "but I daresay Mr. Hovesdean would like to see Lord Harborough, and it really is not far out of the way to call there first."

"Let us do so, by all means," exclaimed Mr. Hovesdean. "Eh Sadie?"

The young lady said nothing. After all perhaps Mr. Savage was not such a very disagreeable man.

THE carriage was driven rapidly out of the station yard and turned eastward. Mr. Hovesdean and his daughter sat with their faces to the horses. Mr. Savage sat opposite to them, leaning back in a corner, and with his head and shoulders completely in the shadow. Directly they got into the Euston road Mr. Hovesdean bent forward.

"Now I guess Sadie would like to hear what there is to hear about this accident of Lord Harborough's," he remarked. "Is his foot seriously hurt, or will he be able to get about in a day or two? This is my daughter's first visit to London, you know, Mr. Savage, and there's a good deal for her to see."

"I sincerely hope, then that Lord Harborough will be able to be showman," Mr. Savage answered with a slight bow towards the young lady. The movement brought his features for a moment into a stray gleam of light from a passing carriage. Both father and daughter started slightly. There was a curious glitter in the black eyes, and his face was almost ashen. Mr. Hovesdean was politely concerned. The girl with a quicker instinct, was conscious for the first time of a vague uneasiness.

"I fear that you yourself are not quite well," Mr. Hovesdean commenced.

"A trifle of neuralgia. It is nothing," interrupted Mr. Savage. "We were speaking of Reggie's accident. Really it is more inconvenient than serious. He was driving right across London in a hansom, and as ill-luck would have it, in one of the very worst parts down went his horse and Reggie was pitched out. He tried to jump, but got his foot doubled up under him somehow and sprained his ankle. They helped him into a low public-house just opposite where the accident occurred—a vile place—and he scribbled a note to me at once. Fortunately I was in my chambers, owing to this neuralgia, and I went down to see him, and promised to meet you, Mr. Hovesdean; but he, of course, said nothing about your daughter. Naturally I was a good deal surprised to see her. I couldn't for the moment decide whether Reggie had been playing me a trick or whether it was a genuine case of surprise."

"It's the latter, I can assure you," Mr. Hovesdean said, smiling. "Lord Harborough hasn't the vaguest idea that I am bringing my daughter. I daresay you know what the arrangement was. He was to come out to the States in the spring. But something has happened, something very unpleasant in itself, which induced me to change my mind. I wanted to get out of the country and settle in Europe somewhere for a while, and so here we are—in England for the present, at any rate. I fancy the young people won't object to seeing a little of one another."

"So far as Lord Harborough is concerned, he can have but one feeling in the matter." Mr. Savage remarked in a low tone. "He will naturally be delighted."

"By-the-by," Mr. Hovesdean asked, leaning a little forward and looking into as much of his vis-a-vis' countenance as the unlit carriage revealed, "have you ever been in the States, Mr. Savage? I fancied when I saw you on the platform that your features were vaguely familiar to me. Here we haven't much opportunity for studying one another's faces."

It was well for John Savage that he sat in darkness, for if his companions had seen the look which flashed across his face it is more than likely that their little excursion together would have been brought to an abrupt conclusion. As it was, it was fully five seconds before he answered, and then his voice was low and thick. The shock of Mr. Hovesdean's innocent question had not been slight.

"No, my travels have been always eastwards," he said. "I have never crossed the Atlantic. That was a pleasure which I might have experienced in the spring." he added, turning to Miss Hovesdean.

She looked at him with a slight smile.

"You and Lord Harborough are great friends, then, I suppose?" she remarked.

"Yes. I may say that we are intimate friends," he answered.

There was a short silence. Mr. Hovesdean looked out of the window.

"What a pace your horses travel at along these narrow streets!" he remarked. "I must confess that I am completely out of my bearings. I know my London fairly well, too—better I expect than some of you Londoners."

"We are in the slums," Mr. Savage answered. "Five minutes more and we shall be at our destination."

Mr. Hovesdean rubbed the window with his coat sleeve and looked out again.

"I should have said that we were getting near the river," he went on. "What filthy looking houses, and what creatures. I'm not sure that we ought to have brought you, Sadie dear," he added, turning towards her.

"It won't hurt me, papa," she answered gaily. "I went into some fearful places in New York with Mr. and Mrs. Fairlie."

"What sort of people are they at the place where Lord Harborough was taken to?" Mr. Hovesdean asked.

"A trifle superior to their neighbours," Mr. Savage answered. "If they were not I should never have dared to have suggested your daughter accompanying us. As it is I am afraid your first impressions of London cannot be very favourable ones, Miss Hovesdean," he added, turning towards her.

"I am afraid," she answered laughing. "I have not even looked out of the window. I'm not going to believe I'm in London until the proper time arrives. Isn't that discrete?"

"Very," answered Mr. Savage. "I should advise you to close your eyes very carefully just now. We are there."

They had turned into a dark squalid street only just wide enough to admit the carriage. On one side was a plot of miserable looking waste ground covered with black mud and puddles and sloping down towards a dark chaos which from the gleam of some far away richly looking lights seemed to be a river. On the other, the side on which they were to descend was a row of high smoke-blacked tenements, nearly all apparently empty and many with the windows smashed to pieces and in the last stage of dilapidation. The one before which the carriage had stopped was a story lower than the rest, and there were several dim lights in the lower windows. Mr. Savage jumped out first, and assisted the girl to alight; Mr. Hovesdean followed.

About a couple of yards to the left of them was a swing door opening into a room from which came the sound of tipsy voices. Hovesdean being a tall man, glanced in, and drew back at once with an expression of horrified disgust.

"Mr. Savage, I am sorry," he said, quickly, "but I cannot allow my daughter to enter such a place as this. Forgive me if I add that I am surprised that you should have bought us. Sadie, get in the carriage. Mr. Savage, kindly give your man instruction to drive to the Langham Hotel."

Mr. Savage shrugged his shoulders. He laid his hand upon Miss Hovesdean's arm and prevented her re-entering the carriage.

"It does look bad, certainly," he said, "but there is a back way in, up this court."

Mr. Hovesdean's eyes followed the outstretched finger. There was a dark entry almost opposite to them. Something which he fancied he could see through the gloom attracted him. He lent forward and then stepped hastily back.

"Neither my daughter nor myself will enter this place," he declared hastily. "Sadie, give me your hand! Mr. Savage—Oh, my God!"

He had turned his back for a moment to the entry, meaning to re-enter the carriage, and in that moment two dark figures had stolen out. A pair of huge arms were around his throat holding him as though in a vice, and something hard was thrust between his teeth. He was a powerful man, and his daughter's half-stifled shriek maddened him. He dashed his fist out, and struck one of his captors on the head, and bending backwards, he made a fierce attempt to wrench himself loose. For a moment he had almost succeeded. Then there was a flash of some dull metal in the dim light and a sudden awful pain in his head. He felt himself sinking down, down, down, and then lifted up. He was being carried along the entry, and the last thing he saw was Sadie's pale face convulsed with horror as she stretched out her arm frantically towards him, herself being half-pushed, half carried. Then he closed his eyes. It was their welcome to England.

Mr. Savage stood for a moment outside breathing hard, and ghastly pale. Then he sprang into the carriage. The door was banged to, and he drove away into the night.

AN Englishman of breeding as a rule knows how to control his features. When Lord Harborough left his club in St. James' at the unusually early hour of half-past ten and turned down into Piccadilly, none amongst the throngs of people amongst whom he threaded his way could have guessed his secret. It is true that for a cold night it seemed a little odd that his overcoat should be flying open, disclosing his thin evening clothes, and there was also a certain vacancy in his expression which rendered him oblivious to the greetings of several of his acquaintances whom he passed. But these were the only signs. It would have been impossible for any passer-by to have gathered from his appearance or expression that here was a man who had said farewell to his fellows, who already saw himself head over ears in the dark waters of ruin and dishonour.

Where was he going? He had not the least idea! After the tension of the last week the tension of concentrated and absolutely unceasing thought upon one subject, his mind suddenly quitted hold of it and began to wander. He was conscious only in a dim uncertain way of the stream of faces which hurried past him. Before he had gone half the length of Piccadilly, however they began to vaguely annoy him. He crossed the street to the Park side, where the lights were less brilliant and the pedestrians fewer. Here he slackened his pace.

"Harborough! a word with you if you don't mind!"

Lord Harborough turned quickly round. A tall man in a long Inverness and smoking a cigar, had laid his hand upon his arm.

"Massinger," he exclaimed, "why, what do you want with me? I thought I left you in the smoking-room at the club?"

"I was there," the other answered, walking slowly beside him, and not yet releasing his arm. "To tell you the truth, Harborough, I followed you out."

A week ago Lord Harborough would have elevated his eyebrows in a manner peculiar to himself, and in some occult way would have made it very clear that he considered such a step an infernal liberty. To-night he simply stared listlessly ahead of him and answered in a perfectly spiritless manner.

"What did you do that for? I wanted to be alone."

"I saw that you did," the other answered quietly. "On the other had, there are times, you know, when it isn't good for a man to be alone. It seemed to me that it was one of those times with you."

A shadow of his former self returned to Lord Harborough.

The man who had addressed him, although they were fellow clubmen and had met constantly during the last seven or eight years, was not one of his intimates. There was nothing against him. His family was excellent, although he was almost the last representative of it, he had the reputation of enormous wealth acquired through shrewd foreign investments, and had a sure footing in any society which he chose to enter. He had also another, and more fascinating reputation, the reputation of a man of brains! He had written a book, remarkable for its curiously blended morbidness and cynicism. He was a Member of Parliament, and reputed to be one of the shrewdest and keenest of debaters. But for all that he was a comparative stranger to Lord Harborough, and in some surprise he drew himself up and frowned.

"Much obliged to you, Massinger," he said. "If you'll excuse me—"

Mr. Massinger held up his hand.

"Half a minute," he exclaimed. "Hear what I have to say first! I daresay you think I'm taking a liberty. My only intention is to do you a kindness. I admit that the acquaintanceship between us scarcely amounts to friendship. Against that I put the fact that since Mountford went to Rome and Dudley got married your set broke up, and you haven't an intimate friend left in England. That's so, isn't it?"

Lord Harborough nodded. It was true.

"That's why I'm presuming a little," Mr. Massinger continued. "Fellows will talk, you know, and everyone knows about your losses on Thursday night, and over the Leicestershire Handicap last week. There's a rumour, too, that you're interested in this Hovesdean affair. To-night, when you left the club you looked pretty well cut up. Now I want to know whether I can't be of any assistance to you. Remember you may not think much of me personally, Lord Harborough, but I'm rich, and if it's a temporary affair, and I can help you, well, I'm willing."

Lord Harborough turned and looked at his companion. There was a curious vein of earnestness in what he had said, but the tone itself was peculiar. For a moment he hesitated. In a vague sort of way he had disliked the man—had disliked his flippant cynicism and a certain hardness in his manner. Perhaps he had misjudged him. Just at that moment, at any rate, he felt inclined to think so.

"You're a good fellow, Massinger," he said, wearily. "I'm in a devil of a hole, and I'm nearly mad. But neither you nor anyone else can help me."

"That remains to be seen," Mr. Massinger answered. "Tell me all about it. Here, have a cigar. That's right. Now, fire away."

Lord Harborough was astonished at his own obedience. He had just arrived at that pitch when notwithstanding a natural and ingrained reserve, it was necessary to speak of his trouble or grow mad. Of his own accord, this man was the last whom he would have chosen for a confidant. He had had no choice, however, and he was in the humour to drift with the tide. So he lit a cigar and commenced:

"I've been a d——d fool, I suppose, Massinger! Everyone will say so, at any rate. You can judge for yourself. You know I was in California and Mexico the year before last—went out by a P. and O. to India and Japan and on to San Francisco. I came back through New York and Boston, and people would send me out letters to friends there, and it seemed ungracious not to leave a few, so I made a good many friends there. Mr. Hovesdean was one of them. I became engaged to his daughter."

Lord Harborough paused for a moment and knocked the ash from his cigar. If this man had been a friend he would have talked about her. As it was, he avoided the subject. Mr. Massinger's opinion of and bearing towards the sex was well known.

"I did not find that Mr. Hovesdean was overjoyed at the prospect of having me for a son-in-law, at any rate he did not appear so. He would have preferred an American, I think, but he did not offer any formal objections. He asked me no questions as to my means, and this a little irritated me, I think. One night he was explaining to me how rapidly he had made some part of his huge fortune, and I asked him whether he could invest any money for me to advantage. He should be very pleased, he told me politely, and with some surprise. I was a little nettled—one doesn't care to be thought a pauper—and I cabled the next day to my solicitor, and instructed him to mortgage the whole of the Lillroot and unentailed Harborough property on special terms, redeemable in twelve months. It was done, and just before I left the States I handed Mr. Hovesdean a draft for forty-eight thousand pounds, and begged him to let me have the result of his investment within twelve months."

"Forty-eight thousand pounds," Mr. Massinger repeated in a wondering tone. "My God!"

"Yes, it's a good deal of money, isn't it?" Lord Harborough continued quietly. "I had not the slightest apprehension, however, for Mr. Hovesdean was everywhere spoken of as being one of the richest men in America, and personally I had every confidence in him. The mortgage falls on the day after to-morrow. I told Mr. Hovesdean by what date I wanted the money, and he called three weeks ago to say that he was coming on the Umbria. The Umbria arrived in Liverpool a week to-day, and I have not seen or heard of Mr. Hovesdean. The day before yesterday, as you know, the papers were full of the gigantic Hovesdean failure."

"Isn't there a report that Mr. Hovesdean actually did come to England by the Umbria?" Mr. Massinger asked, flashing a keen sidelong look at his companion. "I suppose you have made some inquiries?"

"That is so," Lord Harborough answered. "I have been to Scotland Yard and I have employed a private detective. A Mr. Hovesdean certainly did cross on the Umbria, accompanied by a lady, who was called his daughter. What has become of them since they landed is a mystery. It is possible that he is in England, and, under the circumstances cannot bring himself to let me know his whereabouts; on the other hand he may have gone straight to the Continent."

"Pardon me," said Mr. Massinger a little diffidently, "but I presume you corresponded with the young lady—"

"Naturally," Lord Harborough interrupted. "Her letters ceased abruptly three weeks ago. I have called six times and had no reply."

"Did her last letter hint at any trouble?" Mr. Massinger inquired.

"She merely remarked that her father had met with some unexpected annoyance I think was her word, and would possibly leave for England a week earlier than he intended."

Mr. Massinger threw away his cigar.

"You've been treated villainously, Lord Harborough," he said. "Of course you've read the papers. You've seen that the firm of which Hovesdean was the head have been hopelessly insolvent for years."

Lord Harborough bowed his head. He had no words at his command.

"So that he must have known that he was simply robbing you when he took that money," Mr. Massinger continued calmly.

Lord Harborough winced. Could not the man see that every word was a stab?

"Exactly," he said, coldly. There was a moment's silence. It could not be said that Mr. Massinger's sympathy was overpowering. The two men had turned and were walking back again down Piccadilly. At Mr. Massinger's instigation they turned into a side street.

"Don't think me inquisitive," he said, "but are you as heavily hit as men say over the Leicestershire?"

Lord Harborough bit his lip.

"Are they talking about it?" he said quietly. "Well Lady Flora's beating lets me in for about four thousand. There's no doubt at all that West pulled her. She must have won on her merits. They tell me the fellow will be warned off."

"There's no doubt your mare was pulled," Mr. Massinger remarked, with a quiet, invisible smile. "That doesn't help your money being lost though, does it? And how about Tulch?"

Lord Harborough closed his eyes for a moment. This cold-blooded narration of his miseries was scarcely the relief he had hoped it might be. What an odd, quiet fellow Massinger was.

"Well, several seasons ago I won about eight hundred pounds from Tulch one night at the Club des Étrangers at Homburg. I've never met him since till Monday night. You know, I've given up play altogether, but I couldn't refuse him when he asked for his revenge. I was worried and excited, and I played altogether wretchedly. In the end I lost a couple of thousand."

"What beastly luck," Mr. Massinger exclaimed. "I'd no idea things were so serious with you. But perhaps you have friends. Let me see, how do things stand? You owe six thousand pounds to be paid in hard cash, and unless you pay something like fifty thousand the day after to-morrow you lose a great portion of your estates."

"The only part that brings me in a copper," Lord Harborough remarked drily.

"Exactly. And you have?"

"Absolutely nothing. My horses and carriage will only just cover my private debts. I went to the bank this morning, and found that my balance was exactly one hundred pounds. I drew that out, and have it in my pocket."

"But your people. The Earl of Wendover—"

"He is as poor as a man in his position can be, and he has nine daughters. There is not one of my relations to whom I can go."

Again a peculiar light flashed across Mr. Massinger's features. Lord Harborough did not see it. There was a short silence. Mr. Massinger lit another cigar and commenced to smoke it deliberately.

Lord Harborough was too steeped in despair to be by any means observant, but even he thought his companion's manner a little singular. There was something almost approaching irritation in his manner as he broke the silence.

"Well," he said, stopping abruptly, "you have heard everything—the whole catalogue of my woes! Now give me your advice. Just put yourself in my place. Tell me what you would do!"

The two men faced one another. Lord Harborough with a calm despair written into his fair boyish face, Mr. Massinger with close drawn lips, and a curious glitter in his dark, deep-set eyes.

"My advice!" he repeated slowly. "I cannot offer any. Your case is too desperate. No one can help you."

A sharp little cry of pain only half suppressed escaped from the other's lips.

"I know it," he said bitterly. "I did not expect help. But you call yourself a man of the world; you have a philosophy of your own. I have heard you admit it. Men speak of you as having strange notions. You live, you have said yourself, by a fixed rule. Now tell me, if you were in my position whither would your philosophy tend. You boast of having a resource for every emergency in life, rules which meet and answer every case. Now tell me plainly, if you were I, what should you do?"

Mr. Massinger threw away his cigar. The light which had glittered in his eyes seemed to have spread over his face. He was strangely agitated.

"Lord Harborough, your question is a challenge," he answered in a low, deep tone. "Come with me and you shall know."

He crossed the street, Lord Harborough following closely. A tall, gloomy building faced them, and Mr. Massinger with the air of one familiar to the place drew a latch key from his pocket. He thrust it in the keyhole of the door before which they were standing, but before he turned it he looked Lord Harborough in the face.

"Lord Harborough, before I admit you here you must swear upon your honour as a nobleman and a gentleman that all that you may see, or hear, the names of all you may meet, and everything connected with this place shall remain so far as you are concerned an inviolable secret. Do you promise?"

"I promise," Lord Harborough answered.

Mr. Massinger turned the key. The two men entered the house together.

THE hall or passage into which the two men passed was only dimly lit, and Lord Harborough, though he looked about him curiously, was not able to see anything of his surroundings. They passed along it without a pause, and Mr. Massinger led the way up two flights of stairs, and along a passage to what seemed to be the rear of the building. A swing door opened before them, and Lord Harborough, taken altogether by surprise, uttered a little exclamation of wonder. They had passed in an instant and without any preparation from gloomy and depressing darkness, into a warm and brilliantly-lit chamber of most singular appearance. For the first time since entering the place he spoke, turning towards his guide in a bewilderment which he did not attempt to conceal.

"Where on earth are we?" he exclaimed. "Is this a private house, or a club, or what?"

Mr. Massinger laughed softly.

"It is a chapter from the Arabian Nights of Modern London," he answered. "Dynock," he added, looking down the room, "our friend here wants to know whether this is a club. What do you say?"

A tall, slim man rose from an arm-chair at the other end of the room, and turned to greet them. Lord Harborough recognised him with surprise.

"Something of the sort, I suppose," he answered, nonchalantly. "How d'ye do, Harborough. Tolerably well-housed, aren't we, for such a gloomy pessimists as we profess to be?"

Lord Harborough took advantage of the remark to glance around him. The appointments of the chamber were at once odd and magnificent; they were altogether and inevitably depressing. The walls were wainscotted with either genuine or clever imitation of black oak, leaving only a narrow band of deep sage green between the top of the wainscot and the ceiling. Every piece of furniture in the room, handsome enough in its way, was of the same colour—jet black. The carpet was of thick black felt, and at the upper end of the apartment was a dining-table covered with a profusion of tastefully arranged glass and silver upon a black tablecloth. There were about half a dozen men in the room, all wearing black ties with their evening clothes, and mostly lounging in easy chairs, upholstered in black leather.

Lord Harborough glanced from one to the other of them with ever increasing surprise. There was not one whose face was not perfectly familiar to him. A distinguished barrister was drinking black coffee and reading The Times in the chair directly opposite to him. A man of letters, whose fame as an essayist and novelist was almost unsurpassed, was writing at a small table in a recess. The man called Dynock was a connection of his own, and a peer of the realm. He had been deep in conversation with a Cabinet Minister.

"Yes, you are comfortably housed enough," Lord Harborough said after a brief pause, "but you will excuse me if I don't altogether admire your style of decoration."

"It is a little trying until you're used to it," Lord Dynock admitted. "I never found a stranger admire it yet. Have a glass of wine and a cigar."

He poured out a glass of champagne from a bottle which stood by his side. A waiter in immaculate black livery glided from the lower end of the room, and noiselessly proffered a box of cigars. Lord Harborough accepted both, emptying the glass before he put it down.

"If your cooking is as good as your wine," he remarked to Massinger, who was standing by his side, "this is the best club in London. May I ask what you call yourselves?"

Mr Massinger and Lord Dynock exchanged swift glances.

"He has passed his word," the former said.

"In that case we will tell you—presently," Lord Dynock said. "First hear our motto. It is 'Mors cum Dignitate.'"

"Death with dignity," Lord Harborough repeated. "I do not understand."

"Naturally you do not," Dynock answered. "The question is, are you sufficiently interested to desire an explanation? Massinger—"

"I brought Lord Harborough here not as a casual visitor, but in answer to a challenge of his own," Mr. Massinger interrupted. "I wish him to know everything."

"And I also desire to know—everything," Lord Harborough added firmly.

Dynock rapped on the table by his side with a silver pencil, and looked around the room.

"Gentlemen," he said quietly, "we have a stranger here properly introduced, and for whose honour I myself can answer. He desires to know something of us. Will any of you enlighten him?"

There was no immediate response. The barrister laid down his paper and yawned.

"Go ahead yourself, Dynock," he said. "Look sharp, and we'll have a rubber of whist afterwards."

Lord Dynock shrugged his shoulders and pushed an easy chair towards their visitor.

"I shan't keep you a minute," he said, leaning against one of the marble pillars which supported the mantel, and stroking his long moustache. "You want to know what we call ourselves and who we are. Well, I'll tell you that to commence with. You are within the august portals of the 'Suicide Club.'"

Lord Harborough started and sat upright upon his lounge. Was Dynock chaffing? His tone and his manner had been perfectly grave. He glanced half fearfully around the room. There was not a smile upon the face of any man there.

"Perhaps you did not even know of our existence?" Lord Dynock continued. "Few people do. Nevertheless we do exist, and the rolls of our membership are being continually added to. If you wish to know the principles of our foundation and justification, there is a small but carefully selected library in yonder ante-room which I think will be of service to you. All that I can say is this. We are men of the world—philosophers up to a certain point, and with a special bias towards the philosophy of individualism. We say that if there should come into our lives a crisis, whether of our own making or not, which, as it were, cuts a clean line of demarcation through our career, dividing all that is to come from all that is gone; that if by reasons of financial ruin, or social disgrace, or crime, we are confronted with dishonour or degradation—we say then that we are justified in refusing to continue our lives upon an altered and a lower level. Life comes to us not at our own bidding, and often remains with us without desire. Therefore, we see no sin, nor any shame, in having some voice ourselves as to its continuance. Mind, the text of our justification is hopelessness. If retrieval of name or fortune be possible, we do not sanction suicide. Any member proposing to take this final step must state his case to three members of the club, and only with their consent must he take his life. Further, we do not accept as members married men except under special circumstances, or men having families or relatives dependent upon them. Our object is simply to prevent moral and physical retrogression. We say that we owe it to ourselves to die in the same status as we have lived. The natural bent of all our lives should be development. When circumstances decree that development must cease and retrogression commence, then comes the time when we sanction and, in fact, advocate suicide. That is our position, as clearly as I am able to state it on the spur of the moment, and in a few words. As to the more material part of the business, the entrance fee and subscription of our club is a trifle high. Massinger can tell you the figures. If you wish to join us you can be proposed to-night, and there are enough here to elect you; but you are not allowed to avail yourself of any of the privileges of the club for at least 24 hours. Have I left out anything, Grimshaw?"

The barrister shook his head.

"You have spoken like an oracle," he declared. "You should explain to Lord Harborough though that we are properly registered as a private club under the name of the 'Epicureans.'"

"That is so," Lord Dynock assented. "We are in reality a secret society, but outwardly we are orthodox and have a recognised existence. Is there any question you would like to ask?"

Lord Harborough stood up. His eyes were very bright and his cheeks were flushed

"Do you often have suicides in connection with the club?" he asked.

His kinsman shook his head.

"Not very often. There has been one this year. You remember Captain Blackmore's affairs?"

"Of course."

"He was a member! Three of us sat on his case, and authorised the extreme measures. He came for our decision, gave a princely dinner here, took a hansom home, and blew his brains out. Of course we do not allow anything of the sort upon the club premises."

"And supposing a member commits suicide without consulting anyone?" Lord Harborough asked.

Dynock shrugged his shoulders.

"Of course we can't prevent it! The rule exists so that the thing may not become abused, but naturally no one is bound by it."

"And can I be elected to-night?"

"Certainly, do you wish to join us?"

Lord Harborough drew a deep breath

"Yes."

"Kindly turn your face the other way for a moment then," Dynock said. "Our method of election is simple but effectual! Gentlemen, are you unanimous in voting for Lord Harborough's election? A nod is quite sufficient. Thanks; Harborough, I congratulate you! You are elected a member of a club unique, I believe, in Europe! Stay and have a devilled bone and a bottle of wine!"

Lord Harborough shook his head.

"Not to-night!" he said, "I must go. The day after to-morrow in all probability I will sup with you."

IT was midnight when the two men passed out into the street. Massinger paused to light a cigar, and as he struck the match he glanced curiously into the other's face.

"Well," he said simply.

Lord Harborough laughed a hysterical little laugh, and passed his arm through his companion's. He was labouring under a curious excitement. His eyes were bright, and there was a spot of red colour on his pale cheeks.

"Excellent," he cried. "Why didn't you tell me of this club before? I might have been a member before instead of having to wait."

Massinger shrugged his shoulders.

"You forget that we have never been exactly intimate, Lord Harborough," he remarked quietly. "I could not take a man to a place like that unless I was prepared to answer for his honour as my own. Until to-night you have never offered me your confidence. By the by, are we not going out of our way?"

They stopped short on the pavement and looked around them. The street in which they were was a silent one, and almost deserted. From behind there came to them the dull muffled roar of a great thoroughfare, blocked with streams of carriages and the restless ebb and flow of crowds of pleasure lovers. Lord Harborough turned his face towards it and listened.

"Come, let us get back," he cried, drawing his companion round. "I'm afraid of quiet places to-night! My brain's a little unsteady. If it weren't too absurd, I should say that that single glass of champagne had got into my head. Do I look wild?"

Massinger looked him steadily in the face. Then he coolly knocked the ash off his cigar.

"A little," he admitted. "Come, what shall we do? Do you want to go back to your rooms or what?"

"Not I," muttered the other hoarsely. "I want to keep away from myself. There is a thought in my brain—it is like a nightmare. I want to get away from it. Massinger, you'll stay with me? I don't want to be alone; I've had a week of it. I'm afraid of going mad. Is there nowhere else you can take me? Who knows, it may be my last night. You know life, Massinger; show me something new."

Massinger laughed softly.

"You talk like a country man," he said. "There is nothing new! There has been nothing new for a thousand years. It is our bane that we men of to-day wear ourselves out body and nerves in search of a new sensation. The world is as stale and flat as yesterday's champagne. The only brave and sensible men are those who quit it."

"And yet to-night I have found something new!"

Massinger smiled cynically.

"The idea is nigh as old as the ground we tread. Read your classics, Harborough. There were philosophers in those days who dared to leave a world that disgusted them; and plenty of them. It is only to-day when art and philosophy have given place to sordidness and commerce that men cling on to the frail thread of life like a set of drowning vermin! Bah!"

He threw his cigar away with a gesture of contempt, and suddenly laid his hand upon the other's shoulders.

"Come," he said, "the night is young, and we are neither, I take it, very much in the humour for the society of civilised beings. Let us take a look at the seamy side—dig under the surface a little, and see what an accident of birth, the possession of a few gold pieces divides us from! I am in the mind to play showman! Come with me, and I will show you London."

"Anywhere! Anywhere away from the faces of the men I know and who know me," answered Lord Harborough bitterly. "I'm in your hand, Massinger; don't leave me just yet."

A slight drizzling rain was covering the pavement and blurring the gas lamps. Massinger stopped and looked around. There was a hansom following them close behind, the driver attracted by the sight of two gentlemen in evening clothes and without an umbrella. They stopped it and got in. Massinger stayed behind for a moment to give his instructions to the driver.

"Where are we going to?" Lord Harborough asked as the apron fell to, and they drove off smartly.

"Never mind," was the grim answer. "If I told you you would be none the wiser. It is not geography we are interested in to-night. I am going to show you a parable!"

To Lord Harborough that long drive seemed in after years more like a vague shadowy nightmare than an excursion really planned and undertaken. So long as their hansom formed one of the countless streams of vehicles passing over the broad bosom of well-to-do London, his companion leaned back in his corner and spoke not a word. But by and by they penetrated into a different region. The roar of Piccadilly and Regent street lay far behind. The streets had become narrow and the paving worse. There were still people passing and re-passing, but people of a different class, people in a different style of clothing, with curiously altered bearing. Pleasure seekers, a good many of them, for the hour was late, but pleasure seekers with white faces and hurrying footsteps. Massinger leaped forward and laughed softly.

"Behold, Lord Harborough," he exclaimed, waving his hand out of the cab, and with his deep-set eyes intently fixed upon the other's face, "behold the Utopia of the city club and drudge, the paradise of middle-class suburban London. See the new streets and the miles of new houses—faugh! how they smell of mortar and the watering can. This is the refuge of the man who wears a black coat—the man who has come down in the world. It is to breathe this air and mix with this society that he hugs his respectability, dines at a vegetarian restaurant for sixpence, and walks backwards and forwards to the city. There goes the type. See how his coat shines, how wan and pale are his cheeks. They have kept him late at the office, and he is hurrying home. See, then, it is that dingy little house with a broken gate. No lights, you see, no fire with coals at twenty-five shillings a ton; perhaps a little Dutch cheese and a crust of dry bread for supper. If he has a wife, depend upon it she is as thin and worn as he is, and lacking every feminine grace. Want will crush them one by one as surely as day follows day. She probably has a tongue and for certain a temper. She has had a great many more children than she had any right to, and the last shred of grace and the last vestige of good looks have gone with the last baby. The gentility that was in her dies out like an unfed fire. She becomes a sloven and a scold, and her children destroyed by the curse of cheap education simply multiply the breed! See, there is another. The pitiful scraping, the toil by day, and his miserable bare home at night have driven him to the public-house. Now he has to sneak in home, and bear the storm as well as he may! Poor devil! Poor devils all of them!"

"Amen," echoed Lord Harborough, with a shudder. "How on earth did you get to know all about those people and their lives?"

Massinger laughed cynically.

"In my small way, I am an interested observer of men and their lives," he said. "I think that I have a sense of the dramatic! Man struggling against fate fascinates me! Some day I think I shall write a novel. If I do, I promise you that it will not be popular."

Lord Harborough shrugged his shoulders.

"You are a rank pessimist, Massinger," he declared.

"All men with a single grain of philosophy are pessimists. The more one knows of man and appreciates his cowardly fear of death, the deeper grows one's scorn of him. Look at this wilderness. Think of the thousands and thousands of heart-broken men clinging on to life with a desperate nervous tenacity which seems to be the ruin and end of all their strength."

"Their wives and families!"

"Bah! In half the cases their wives and families would do better without them. They would rise to their level and earn an honest living. But I speak of the other half, the great army of men who must know that the world has no need of them, and that every step forward in life must be on the downward grade."

Lord Harborough made no answer. He sat forward, watching the passers-by in the streets with a sad, gloomy face. Massinger from his corner never looked away from him. He was trying to read how the parable worked.

By degrees the character of the neighbourhood through which they were passing changed. Dinginess became dirt, shabbiness squalor. The corner public-houses became glaring gin palaces. The shops became open stalls, and the streets narrower. The dark silent misery of the suburb was changed into the flaunting coarseness of the slums. Fighting men and wrangling women formed little knots at every street corner. Massinger put up his hands and stopped the cabman.

"We will walk from here," he said. "Button up your coat, Lord Harborough."

The cabman, much overpaid, touched his hat and drove off with a curious look over his shoulder. Massinger took his companion's arm, and they walked off together down the narrow street.

It seemed to Lord Harborough that the horrors increased. At every step they were jostled and confronted by creatures from whose drunk sodden features every spark of womanhood seemed to have died out. The air, foul enough itself, was full of shrill oaths and threatening cries. Once, at a crossing, a girl flitted like a shadow out of the darkness and touched him on the elbow. She could not have been more than fifteen or sixteen, and but for her hollow cheeks and terribly deep set eyes she would have been pretty. As it was the pleading light in her eyes, and the quivering mouth, brought a great lump into Lord Harborough's throat. He thrust a sovereign and some silver, all he could find for the moment, into her hand. He felt her fingers close upon it, and he hurried on. But she made no attempt to follow him. Presently as he heard no footsteps he ventured to look around. She was leaning against the wall crying bitterly.

"My God! surely this is hell!" he muttered. "There can be nothing worse than this."

Massinger shot a quick glance at him.

"How do you know? Evolution is illimitable. You have seen these men's faces. Would it surprise you to hear that not half of them were born in this condition? They have drifted here from all classes of society, many if not from yours, at least from mine. Remember that in this world, the unsuccessful and the criminal rank together; and fall together."

They strode on together in silence. Suddenly Massinger stopped short in the middle of the pavement.

"D——n," he muttered.

They were underneath a gas-lamp, and Lord Harborough glancing carelessly up, himself started. Massinger's face was suddenly ghastly. He was staring across the road toward a high block of seemingly uninhabited houses in the last stage of dilapidation. On the opposite side was a plot of waste ground, a ruined wharf and the river.

"What is it?" Lord Harborough asked impatiently.

Massinger shuddered palpably as he answered.

"Nothing! I'd no idea we were coming out here though. Let us take this turn."

He laid hold of his companion's arm as though to draw him away. But Lord Harborough did not move.

"Why were you looking so intently at that block of houses over the way?" he asked curiously. "What a God forsaken hole it is!"

"Aye, and good reason for it," Massinger answered quickly. "There is not one of those gaunt hideous looking houses that has not witnessed a murder. They call the place Hellside. Come away; we are deeper in the heart of this region that I had imagined. See how the people watch us."

Lord Harborough laughed recklessly.

"Who cares. I'm going to walk down and look at that place."

"We are in danger even here," Massinger whispered, glancing over his shoulder. "Let the place alone. There's nothing to see."

"I'm in the humour for horrors," Lord Harborough answered grimly. "Stay where you are if you like. I shan't be a minute."

He crossed the street, and strolled slowly down the miserable sloppy lane which fronted the houses. Massinger with his right hand firmly clenching something in his coat pocket, followed a few steps behind. There was a grey shade in his face and an evil glitter in his eyes.

Lord Harborough walked about half way down, and then turned abruptly round. He confronted Massinger.

"Faugh! what smells!" he exclaimed in disgust. "I've had enough, come."

They walked rapidly away, but Lord Harborough had only taken a few steps before he stopped short.

"Wasn't that a cry?" he exclaimed. "Listen."

Massinger shook his head.

"I heard nothing," he declared impatiently. "Come along; there's a whole crop of fevers in that swamp."

Lord Harborough had turned round and was gazing up at one of the topmost windows of the block of houses. A light was burning there, and the faint outline of a woman's figure showed against the window pane.

"That's odd," he exclaimed. "I could have sworn that woman cried out. See, she's waving her arms. Come on, Massinger."

He would have plunged across the street, but his companion detained him.

"Lord Harborough, if you enter that house, it will be to a shameful death," he said firmly. "The woman is a decoy. Your own common sense ought to tell you so! I can understand you not shrinking from death, but at least you owe it to your family and your order to die like a gentleman, not to be found in a common house in the vilest quarter of London."

Lord Harborough dropped his arm.

"You are right," he said sadly. "Come."

As they moved away he glanced once more half fearfully up to the window. He stopped short and gave a little cry. Then he turned round and hurried away, faster even than Massinger could keep up with him.

"My God!" he said, half to himself, "I am going mad! I must be going mad! It was her face! I could have sworn it! Massinger, let us get out of this awful place as quickly as we can!"

Massinger stopped and lit a cigar, then he took Lord Harborough's arm.

"There's a cabstand in the next street," he said. "My parable is over. Have you read it?"

And Lord Harborough said nothing; but in his heart he knew that he had!

THE early sunlight stole through a slight opening in the heavy curtains, and commenced to play strange antics upon the floor and on the furniture of one of Lord Harborough's suite of rooms in St. James'. Presently it reached the heavy oak writing table, glanced upon a pile of papers and a little heap of gold, and finally smote the closed eyes of Lord Harborough himself, who sat there with his head dropped upon his folded arms.

He woke with a little start, and looked wildly around him for a moment. Then he remembered what had happened. He had come in about midnight, and had commenced sorting these bills. He must have fallen asleep.

He got up and threw back the curtains. It was a bright clear morning, and the sunlight came streaming into the room. For a brief while he stood there looking half wistfully, half sadly out into the broad handsome street. Then he turned away with a sigh and rang the bell.

A manservant answered it almost immediately. Lord Harborough was sitting at his desk addressing an envelope, but he glanced up as the man entered.

"Groves," he said quietly, "I want you to go round to the stables and tell Carver that he must put the clothing on the horses and take them round to Mr. Leadbetter some time to-day. I have sold them."

"All of them, my Lord?"

"Yes, Groves, all of them. When he has done that he must make arrangements with Poultney and Adams to fetch the carriages. I have sold them too. You will give Carver this letter. It contains both the men's wages and a twenty-pound note between them. I shall not require either of them after to-day. You can tell Carver that in case I should be out of England—I am going away—when he wants it, I have enclosed a testimonial for him."

"Very good, my Lord."

Lord Harborough hesitated for a moment. Then he took a handful of letters from the table.

"I want you to go round with these, Groves, and get receipts. The fact is—I am going away—for some time, and I can't square off everybody, as I should like. I have gone through my accounts, however, and have selected those whom I thought the poorest for immediate payment. There are only one or two left over, and they must wait. Now the only question is whether I have omitted anyone. Do you remember any account I owe which ought to be paid?"

"No, my Lord," Groves answered, sturdily. "I shouldn't pay any of 'em, if you'll pardon my taking the liberty of saying so, my Lord. Let 'em wait. You're going to travel. We shall want the money ourselves, my Lord. There isn't one of 'em as wouldn't be willing. Your Lordship has always dealt with the same people, and paid 'em punctual, and there's not one of them that hasn't made more money out of you than you owe them now."

"That isn't quite the way to look at it, Groves," his master answered. "By the bye, you asked my permission to have your last livery made at a small tailor's—a distant connection of yours, I think. He must certainly be paid. Do you know how much it was?"

Groves looked as near embarrassed as a perfectly trained servant could.

"I hope your Lordship will pardon the liberty, but I paid him myself about a week ago. He seemed to be wanting the money, and—"

"And you knew that I was hard up and didn't like to ask me for it," interrupted Lord Harborough, a slight flush stealing into his wan face. "Thank you, Groves. Now tell me, have you paid any other account in that manner?"

"Certainly not, my Lord," was the prompt reply. "I should not have taken the liberty in that case, but the man happened to be a connection of my own."

"How much was the livery, Groves?"

"Nine guineas, my Lord."

Lord Harborough counted out ten sovereigns from the little pile before him, and held them out to Groves with a letter.

"You will find your wages in that letter, Groves, and a trifle over—also a testimonial. I am sorry to have to part with you, but under the circumstances it is quite unavoidable. You have been an excellent servant, Groves. Shake hands."

The man bowed low over the white shapely hand which Lord Harborough held out to him. His voice seemed a trifle husky.

"If your Lordship would permit me to accompany you I should be no expense whatever," he said. "I—I have some money, and I need a change."

Lord Harborough looked away for a moment.

This was the man whom he had looked upon and heard quoted as the typical fin de siècle type of the human automaton—grave, dignified, and precise, without feelings and without sensibility. The words of a modern French writer flashed across his mind—"It is only when one is about to leave the world that one begins to appreciate its goodness."

"I thank you, Groves," he said. "The nature of my journey would make such an arrangement as you propose quite out of the question. Go and do those errands and come and see whether I am in when you return."

The man bowed, and withdrew, closing the door after him. Lord Harborough was alone.

LORD HARBOROUGH sat for fully ten minutes without moving. Then he opened a drawer at his right hand and drew out handsome shining revolver. He examined it mechanically, but carefully. Every chamber was loaded. Then he laid it down by his side.

"There seems to be nothing else," he said to himself—"letters to Massinger, Lady Agnes, and Mary, and—and Sadie."

"I wish it could all have been kept from her; but of course that is impossible. She is bound to hear it; better from me than anyone . . ."

"I wonder if I should ever have thought of this if it hadn't been for Massinger. I don't think so. It seems very clear now though. I couldn't meet that fellow Tulch and ask him to wait. If only I could see Sadie again once—just for a moment. I'd like to tell her that I don't blame her father, and that she isn't to mind. Sadie! What an odd name it sounded when I first heard it, and yet I've grown very, very fond of it, too!"

There was a photograph on the table beside him. He took it up and looked at it thoughtfully. When he put it down his lips quivered a little and his eyes were dim.

"It's hard not to see you again, dear," he said softly. "Yet your face shall be the last in my memory. Shall it be as you stood on the docks in Boston Harbour waving your handkerchief to me as I leaned over the steamer's sail, and the distance between us widened and widened until your face was lost in a sea of faces, and only the memory of it was left? I thought of you a good deal on that voyage, Sadie, my love. What glorious nights those were. I used to lean over the rail at twilight, with my face turned westwards, and watch the grey shadows riding on the waters, watching them so long that I could almost see your face then and your handkerchief waving, and tears glistening in your eyes. And at night, when every one had gone below, and there was no sound but the dull throbbing of the engines, I used to think of you then, too—of our life together in England, and how you would love my old castle and the country lanes, and the old-fashioned folks! There was so much to show you that would have been new and delightful. How happy we should have been—you with that wonderful joie de vivre of yours which seemed to turn everything you saw to happiness and laughter, and I in having you always with me. What music there seemed in the salt wind, and the rushing of the sea, away from the bows! And this is the end of it! I shall feel your soft white arms around my neck no more, dearest, or your dainty hesitating kisses upon my lips. I wonder whether someone else—"

A little sob checked his speech. He rose abruptly, and thrust the photograph away.

"What a consummate fool I am," he muttered. "What on earth possessed me to sit down and brood upon the one thing likely to unnerve me! Poor little woman, I hope she will never know that it was her father who has ruined me. I have done all I can to keep it from her."

He took up the revolver again with a firm hand, and sat down. In the act of leaning back his eyes fell upon the little pile of money still left on the table. He hesitated for a moment.

"I wish I could do some more good with that money," he said, thoughtfully. "There must be hundreds of poor devils who would be thankful for it. It might save someone even from despair. I wonder—"

A thought flashed across his mind. He put down the revolver and counted the money. There was one hundred and eight pounds. He thrust it all into one little pile, and commenced hastily to change his clothes. In a few minutes he was dressed for the streets. He locked up the letters and put the revolver and the money into his pockets.

"I can be back in two hours," he said, looking at the clock. "After all, there was something that reminded me of Sadie in that girl's white face. If money can take her out of that vile region and give her a fresh start, she shall have it. I don't think she can be altogether bad, or she wouldn't have had that look of Sadie in her face. Anyhow, I'll risk it."

"AT last," muttered Lord Harborough to himself with a little sigh of relief. "I began to think that the whole thing must have been a dream."

It was nearly three o'clock in the afternoon, and since early in the morning he had been searching amongst the maze of Eastern London for that block of houses and narrow little bit of street. Its proximity to the river and its sobriquet "Hellside" had been all the clue he had held, and for hours he had been making inquiries and starting off on a fresh scent, only to find himself disappointed. Strange to say, the length and tediousness of his search had not in any way discouraged him. If anything, he was more bent upon his enterprise than when he had started.

He crossed the road and walked down the gloomy little street. By day its appearance was even less prepossessing than by night. The houses were encrusted with filth and there was scarcely a window that was not riddled with stones. He hurried along, picking his way amongst the black puddles and refuse of all sorts until he came to an ash heap. Exactly opposite was the window at which the girl had appeared. He stopped short and looked around.

The bottom part of the place was evidently a public-house. Upstairs there was not a sign of habitation. The windows were all blank and uncurtained. Yet he had made no mistake—he was sure of that. It was at the fourth window that the girl had appeared.

He crossed the road and pushed open a swing door. There were two deep steps down, and he found himself in a sort of drinking cellar. Two men were sitting on stools drinking, and another with a dark, villainous face and earrings in his ears was leaning over the counter. All three gazed at Lord Harborough, who had forgotten in the hurry of starting to make any change in his ordinary style of dress, in blank amazement.

Lord Harborough crossed the sanded floor, and addressed the man at the bar.

"Do you let lodgings?" he inquired.

The man's jaws came to with a snap.

"No," he answered shortly, "I don't! What if I did?"

"May I ask then whom you have living upon the fourth floor? I saw a woman's face there the night before last. I want to speak to her. I shall not trouble you for nothing."

Lord Harborough put his hand in his pocket, but instead of drawing out the money he had intended, his had closed upon the butt-end of his revolver. A curious vivid colour had stolen into the brown swarthy face of the man whom he had addressed, and he had seen a sign pass to the two men behind him. He stood a little on one side so as not to be taken unawares, and waited.

"You must have been drunk," the man growled. "There's no one but rats upstairs here. The floors are rotten and the houses are coming down. No one could get to the fourth floor. The staircase has fallen through."

"I was not drunk, and I am determined to see the girl," Lord Harborough announced firmly. "She seemed to be in distress, and tried to attract my notice. If you tell me any more lies about it I shall be obliged to have the place searched."

A stealthy sign passed from the man behind the bar to the two who were drinking. Just in time Lord Harborough leaped back towards the door, and the shining barrel of his revolver flashed out upon the gloom of the place. One of the men whose hand had been extended to pass round his neck from behind leaped back with an oath. The other got up and came forward growling.

"Not an inch further!" thundered Lord Harborough. "Now, then! Are you going to—"

The rest of the sentence was lost in a general uproar. The landlord, leaning all his weight upon a brown, naked arm, had leaped over the counter.

"Spring at him, you b——y fools," he yelled. "Don't let the b—— go."

Lord Harborough raised his revolver and fired harmlessly at the wall. In the momentary confusion, and hidden by the smoke, he dashed his fist into the face of the man nearest to him, knocking him backwards, and leaped through the door into the street.

No one followed him. He reached the corner of the street and ran almost into the arms of a policeman.

"Quick!" he cried. "You're wanted down at the public-house there! Can you whistle for another constable. There are three men down there."

The man stared in astonishment.

"What's wrong, sir?" he asked.

"They've got a girl there, she tried to attract my notice from the window. I've just been to ask and they set on me—three of them. It's some villainy I tell you, and while I'm gone they'll kill her. Listen, I am the Earl of Harborough, and here's a twenty-pound note."

The man drew his whistle and blew it.

"I want no money for doing my duty, sir," he answered promptly. "If there's anything really wrong at Hellside Jan's I'll get my stripes for being in the know. We want to get the place shut up. Come on, sir. There'll be three more on 'em on our track."

He started off running vigorously, and Lord Harborough followed at his heels. Long before they had reached the door three other policemen and a sergeant in plain livery had joined them. Behind them came a motley rabble of men and women breathless with excitement.

One by one the policemen stooped down and filed into the gloomy cellar. Lord Harborough followed. Outside was a sea of bobbing heads.

The sergeant's eyes travelled round the place like lightening. Two men, seemingly drunk, were sitting in a corner. The landlord raised a sleepy head from behind the counter, and glared at them in well-affected astonishment.

The sergeant turned towards Lord Harborough.

"What's the charge?" he asked.

Lord Harborough answered, speaking rapidly.

"The night before last I was down with a friend, who wished to show me the East end. At a window in the fourth floor of the house I saw a girl who tried to attract my notice. I was persuaded that it was only a decoy and I went away. To-day I feel somehow uneasy about it, and came here. I asked civilly to see the girl. That man denied that anyone was here. I persisted, and they all three set on me. Here is my card. I am the Earl of Harborough, and I beg you to make the most searching inquiries."

The sergeant saluted. "We shall do so, my lord," he said. "This man has given us a great deal of trouble already. Now, men," he added, turning round, "Martin, hold those doors and see that none enters or leaves the place. Saunders, go through to the back and remain there. No. 89 and 90 stay here with Martin, and if either of these three men move blow your whistles and handcuff them. Dick, you and the gentleman come with me. Have you anything to say Mr. Berger?"

The man glanced at them sullenly.

"No."

The sergeant led the way, and they passed behind the bar into a dark stone passage. Opposite them was a crazy staircase from which the banisters had been torn away, and even some of the steps.

"One at a time," cautioned the sergeant. "You go first, Dick. Don't be in a hurry, sir. It's a regular caution that staircase is. Looks like a trap."

It bore them all, however, and so did the next. On the second floor they left the policeman and hurried on to the fourth. The whole place seemed to be deserted. The doors of the rooms stood wide open, and the walls and floors were bare. They did not pause, however, until they reached the top floor.

"This would be the room looking out into the street," said the sergeant, walking on to the end of the passage and kicking open a door. "H'm! seems empty enough."

They stood together in the middle of it. There was no sign whatever of any recent occupation. The paper was hanging down from the walls in long forlorn strips, and the windows were broken and thick with dirt.

"We'll look at the others on this floor," said the sergeant shortly.

They entered them one by one. Before they had finished, however, the sergeant drew Lord Harborough back into the room they had entered first.

"Anything strike you here?" he remarked, pointing downwards to the floor.

Lord Harborough followed his fingers. His heart gave a great jump.

"They've swept the floor," he cried, in a low excited whisper. "In every other room the boards are thick with dust!"

"Exactly," the sergeant remarked.

He walked to the wall opposite to the door, and sounded it carefully with his knuckles. After a few attempts he stopped, and turned round. There was a crimson flush on his face.

"I wouldn't have been out of this for a year's pay," he said quickly. "There have been rumours for years of a hidden chamber somewhere in this quarter with an iron door. No end of undetected crimes have been set down to its existence; and we've searched and searched till I'd despaired of ever finding it. There it is, my Lord—found."

He strode out on to the landing, and blew his whistle softly. The man who was on the landing below came hurrying up.

"Take my compliments to Mr. Jan Berger," the sergeant directed, grimly, "and ask him to step this way and bring the key of the iron door."

IN less than two minutes the man was back again, accompanied by the landlord of the place. A great change had come over the latter. His face was ghastly and the perspiration stood out upon his forehead in great beads.

The sergeant who had been on his knees examining a certain part of the wall, rose and faced him.

"I am Berger," he said sternly, "the game is up. Unlock the door there!"

The man shook from head to foot.

"Sergeant," he said hoarsely, "this ain't been my game; I'll confess every thing. I've only kept the key."

"Unlock it!"

The man dropped on his knees and pressed a button. A small portion of the wall, about an inch square, flew back. He drew a curiously shaped key from his pocket and fitted it into the crevice. There was a click, and an iron door of wonderful thickness slowly rolled back. The handcuffs were over his wrists in a moment. Then all three men rushed forward, into the inner room.

The first sensation of each of them was not horror, but blank amazement. They found themselves in a moderately large room, furnished handsomely and even with taste. A soft turkey carpet covered the floor, the walls were hung with an expensive wallpaper, there were lounges and chairs, books and even flowers. A lamp was burning on a table, and a girl, who had risen to her feet at the sound of the opening door, had evidently been reading by its light. Stretched on a sofa beside her, was a man apparently just awakened from his sleep.

Lord Harborough felt his heart stop beating, and then suddenly beat into rapid tumult. He was looking into the face of the girl who had beckoned him from the window, a pale face, with coils of fair hair, parted in the middle, waving about her head. Her lips were a little parted, and a glad light was glistening in her eyes.

"Reggie," she cried. "Oh, thank God, thank God!"

Lord Harborough took one rapid step forward, and clasped her in his arms.

"Sadie," he whispered hoarsely. "My God, it's Sadie!"

It was Sadie, and it was Mr. Hovesdean who struggled up from the couch a moment later and caught hold of his hand energetically.

"I'm thankful you've found us out, Lord Harborough," he cried. "Another week of this and I should have gone mad."

Lord Harborough took a deep breath and drew back. He looked from one to the other! It was no dream! There was no possibility of any mistake. It was Mr. Hovesdean and Sadie!

"How on earth did you get here?" he asked. "I don't understand. I—"

Mr. Hovesdean, calm and methodical, drew out his pocket-book and rose superior to the general bewilderment.

"First of all," he said, "I cabled you on the 20th of last month that I was leaving by the Umbria—"

"I never got it."

"Exactly. I telegraphed you from the docks at Liverpool to meet me at Euston—"

"I got no telegram!"

"The plot thickens. At Euston we were met by a tall, gentlemanly man who called himself Savage—Mr. John Savage—and apologised for your absence. He told us that you had been thrown from a hansom cab earlier in the day and had hurt your ankle. Was sorry that it was in a low part of London, but he evidently expected us to go straight to pay you a visit. Well —"

"Good God! I was never in a hansom—"

"Don't interrupt," Mr. Hovesdean continued. "The whole thing is a plot of course. We were shown into a private carriage and driven here. Just as we got out I began to feel a little suspicious. I drew back, declined to enter the place. The gentleman who had conducted us here immediately hit me on the head with a life-preserver, two great brawny ruffians rushed out, and in a twinkling we were bundled up a dark alley and into this room. Here we've been ever since."

The sergeant stepped forward with sparkling eyes.

"It's a lovely case, sir," he said, saluting. "Any robbery, sir, or threats?"

Mr. Hovesdean turned towards him

"That is the most extraordinary part of the whole affair," he declared. "There has not been the slightest attempt at doing anything of the sort. A polite note in a disguised hand was brought me on the first morning—I have it here—simply saying that we should not be harmed or robbed in any way, and regretting that a certain matter connected with the writer rendered our temporary absence from the world advisable, or something of the sort. I have in my pocket nearly a thousand pounds and a letter of credit for another two thousand. Neither have been touched. We have been waited upon by an old ship's steward, a villainous-looking fellow. I beg his pardon, but I did not observe that he was present," he added grimly, noticing for the first time the handcuffed man. "The food he has brought us has been excellent and plentiful. There is a case of fine wine in the corner, and a box of Laranaga cigars came with it. Our chief inconvenience has been want of light; the room, as you see, has no window, and lack of sleeping accommodation, besides these couches. Now I should be glad to know how you found us out?" he wound up, turning to Lord Harborough.