RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"Fields of Sleep," Hutchinson & Co, London, 1923

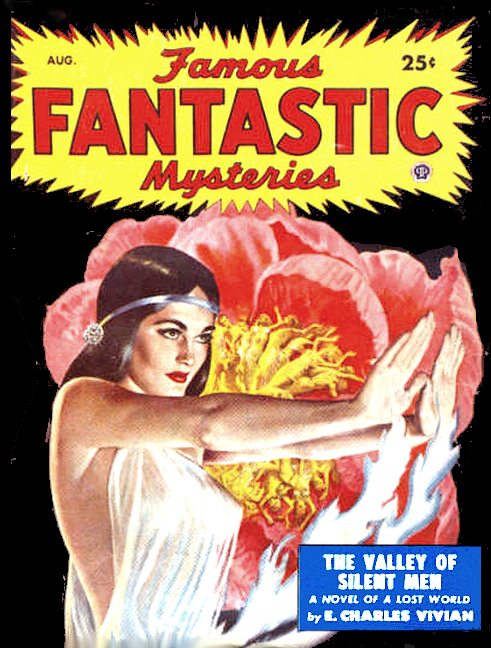

Famous Fantastic Mysteries, August 1949,

with

"The Valley of Hidden Men" ("Fields of Sleep")

THE warmth of the room, obviously one in a private suite, was in keeping with its ostentatious magnificence: both were oppressive. Marshall, coming in from the chill of a late November afternoon, flung back his sleet-moistened overcoat, which had been none too much protection against the temperature of London streets. A tall girl stood to face him—she struck him as more than tall, at a first glance; then he got the quality of her grey eyes, and the soft, deep note of her voice.

"Mr. Victor Marshall?" she asked, supplementing the hotel page's announcement by the Christian name.

Mr. Marshall bowed assent. "With regard to your advertisement—my letter," he answered.

"My step-mother, Madame Delarey, put the advertisement in," the girl corrected. "She will be here in a minute." She looked past him. "This is Mr. Victor Marshall." she ended.

He swung round to face a little, faded-looking old lady who stood just within the room, leaning on a heavy ebony stick. She was small and white-haired and very wrinkled, and the hands on the stick were gnarled and ill-kept, as those of one who works always; the magnificence of the rings she wore was incongruous with her hands, as was she with this garish hotel sitting-room. She peered at Marshall for long seconds, and then came forward, seating herself stiffly on the very edge of one of the plush- covered chairs, as if she feared to disturb the fabric.

"You will sit down—yes? When you have remove your coat, Mr. Victor Marshall."

"Thank you—the coat doesn't matter," he answered, seating himself so as to face her.

"This—my daughter Stephanie—she know," Madame Delarey explained, accounting for the girl's presence. The girl herself made a little gesture of dissent, but did not speak. Marshall merely bowed his head assentingly.

"I advertise for a man, young, resourceful, strong, who know the languages of Malay. You answer—you?"

"I answered," Marshall said. "I don't know what you want of the man, but—well, I answered."

Stephanie Delarey, as Marshall judged her name to be, went and sat down by the window, looking out into the street. Her manner was that of one who had heard all before, and thus was little interested.

"I pick out your letter, for you say little—there were many letters," Madame Delarey pursued. "Now I see you, I think I pick right. Two men come here before you today, and they go away. I do not like them. I am Frainch, Mr. Victor Marshall, and quick, vairy quick, to like or not to like. You, I like."

Marshall waited. Then: "What is the service—what is it that you want of your man?" he asked.

"You listen, I tell," said the little old lady. "It is what you call a story, and all that story I must tell. You listen—yes?"

"Certainly," Marshall answered, gravely.

"Bon! Then I tell you my story, and you see if you laik my proposal. You are not married—no?"

Marshall shook his head, smiling. The little old lady was so misplaced here, bourgeoisie in a salon of utter exclusiveness; she was like a washerwoman at a court drawing-room, and all the magnificence of her jewellery and rustling silks could not make her other than incongruous. It struck him that, uncertainly as she pronounced her English, she knew it well.

"The man I want shall be free, able to go where I want, do what I ask, and he shall be of those who know the islands of the East, and the talk of the islands. You are that man—yes?"

"I am that man," Marshall said. "I gave you my experience of the islands in my letter of application."

"Bon! Then I tell you my tale. You listen."

She settled herself very gingerly on the edge of her chair, as if she feared to sit on it too heavily. Again Marshall smiled; she was so evidently an intruder on the ultra-magnificence of the furnished suite. The girl by the window looked out into the street.

"I 'ave my 'usband, my son Clement, and my daughter Stephanie—this is my daughter Stephanie," said Madame Delarey, indicating the girl by the window, who again made that little gesture indicative of dissent or denial. "My 'usband was a good man, but at business not good—you understand? 'E was ancien régime—aristocrat—you understand?"

Marshall bowed rather than nodded. The grace and dignity of the girl Stephanie, so much at variance with the manner and appearance of the little old lady, might be due to her father's stock, he thought.

"One day," Madame Delarey pursued, "my 'usband come to me and 'e say, 'Annette, there is one month, and I must raise three 'undred thousand francs. Else it is disgrace, and 'ow shall I, a Delarey, be disgrace?' And the month go past, but the money do not come. My 'usband write to 'is brother Armand, and Armand write back to say that since my 'usband disgrace 'is people by marrying me, 'e shall lie on the bed 'e made. And when that month is ended, my 'usband shoot 'imself, and I am widow."

It was stated quietly, unemotionally; Marshall looked across at the girl Stephanie, but she sat with her face averted, gazing out into the sleet-swept London street. The little old lady plucked thoughtfully at her rich black silk, and then smoothed it down carefully.

"I send for Stephanie from her convent school, and for Clement my dear son from 'is school, and Armand my 'usband's brother come to me with tears in 'is eyes. I tell 'im no tears can give me back my 'usband, and I spit on 'im. So 'e go away.

"After the burying, when it come time for my dear son Clement to go back to school, 'e come to me and put 'is 'ands on my shoulders, and 'e say it is not fit that 'e go back to school to waste more time. 'E is then nearly nineteen years old. 'E say, 'I will work till all the money is paid, and my father's name is once more a name of honour. 'E could not pay, so 'e die as a Delarey should die, but for me it is to restore 'is name.' So with my blessing 'e go out to Pierre Delarey, 'is cousin in Sapelung. For my 'usband 'ave two brothers, Armand who would not 'elp and I spit on, and Jean, who die and leave 'is business to 'is son Pierre, 'is son in Sapelung. And I bid good-bye to Clement when 'e sail for Batavia, six years ago, and against my wish 'e take an oath to the Blessed Virgin that 'e will not come back till the last sou of the three 'undred thousand francs is paid."

She paused in her recital. The girl Stephanie stirred restlessly and settled to immobility again. Marshall felt the airless heat of the room as utterly oppressive, and wondered whither this strange story was tending.

"That was six years ago," the little old lady went on. "For two years Clement write to me from Sapelung, and say 'ow Pierre was good to 'elp 'im, and altogether 'e send me five thousand francs, which I pay to my 'usband's creditors.

"Then one day come a letter. Armand, my 'usband's brother, die, and leave to my dear son Clement six million francs, 'to atone,' as 'e say, in 'is will that leave the money. But I do not even forgive 'im dead, for it would 'ave been so easy to save my 'usband when 'e ask. Six million francs, of which the notaries say I 'old in trust for my dear son, and so I write to Clement, but no word come back. I write to Pierre, and 'e write that Clement went with American man, 'e think, shooting, and from that day I 'ave no word of my dear son. I 'ear no word, and 'e is all I 'ave, my Clement."

The girl Stephanie rose, went to a Japanned dispatch box, and took thence a photograph which she gave to Marshall.

"That is my step-brother," she said. She appeared not to notice the implied slight in the old lady's last words. Perhaps she had grown used to it.

"You understand?" Madame Delarey pursued. "There is no need for 'im to stay away, if 'e only knew. Pierre say 'e cannot trace Clement, and no more word come to me, so I advertise, three years ago. I send two men out to Batavia and on to Pierre at Sapelung, to go on to find my dear son. What names were they, Stephanie?"

"Henry Benson and Jean Pernaud," the girl answered. It seemed to Marshall that the story was so familiar as to have lost all interest for her.

"Yes," Madame Delarey said, "Benson and Pernaud. To each of these I pay the passage to Batavia and on to Sapelung, and to each I give five 'undred pounds, with the promise of five 'undred pounds each if they bring back my dear son. And I write to Pierre, and tell 'im. The man Pernaud die at Sapelung, and Benson 'e go pearl fishing—So Pierre write to tell me. That was two passages and one thousand pound—for nothing! Then another year I advertise again, and a man with a funny name, Erasmus Whauple, I pick 'im to go. I give 'im five 'undred pounds, and I promise other five 'undred if 'e bring back my dear son, and 'e go. Beyond Sapelung 'e go, to where they grow rubber and there is country not yet fit for growing, and once 'e write back to me that Clement is gone to the valley of silent men. I sent the letter to Pierre, and ask 'im, and 'e write back to say that Erasmus Whauple, when 'e say the valley of silent men, mean death. 'E know no other meaning of 'silent men' so 'e say when 'e write back to me. And from Erasmus Whauple come back no more word to me—'e is lost, like my dear son. So again I advertise, and of all men who answer I tell you this story, and see if you go."

Marshall considered it silently. Already he knew that he would go, but there was more to learn, first. This was but a bare outline.

"Pierre Delarey—you know him well?" he asked at last.

Madame Delarey shook her head. "I 'ave not seen 'im," she answered, in a frightened way, as if this cross-questioning were unexpected. "My 'usband was 'is father's elder brother, and Jean Delarey was agent in Sapelung before I was married—I 'ave not seen 'im too, ever."

"Why are you, French, in England?" Marshall queried, abruptly.

"Armand Delarey 'ave English estates—I cannot sell—I 'old in trust for my dear son," the little old lady answered.

Again Marshall reflected. Clement, not his mother, was beneficiary; he might be merely lost, and again there might be those who would benefit by his disappearance.

"If—forgive me—if your son were proved dead, who is the next heir?" he asked next.

"To Stephanie, 'ere, two million francs, and to Pierre Delarey four million francs," Madame Delarey answered unhesitatingly. "But my dear son is not dead—it is just that 'e is somewhere so 'e do not know, and do not earn money to send as at first."

It was hope against hope, rather than belief, that spoke. The probabilities were strongly against such a conclusion.

"No, of course not," Marshall said, gently.

Madame Delarey looked at him earnestly, searchingly. "Mr. Victor Marshall," she said, and her tone was almost timid, "you are young man, strong, of course—you will go for me and try to find my dear son?"

"I will go," Marshall answered, slowly. "You can book my passage and give me five hundred pounds, like the others, and I will sign any agreement you like, within reason, for a year's service. If possible, I will bring him back."

"'E is all I 'ave," Madame Delarey said, and her lip quivered. "All I 'ave."

"But," Marshall said, speaking more slowly still, "you shall not tell Pierre Delarey one word of me, nor give him any hint that any man is following the others you sent."

She gazed hard at him. "You think—?" she asked.

"Nothing," Marshall said, "for I have nothing to think—no cause to think. But if Pierre Delarey is to be told my errand, I will tell him myself."

"Then you will go?" she asked, eagerly.

"I will go—when you like," Marshall answered.

The little old lady rose from her chair. "You shall 'ear from me tomorrow, Mr. Victor Marshall," she promised. "I will tell my notary—solicitor, you call 'im, and you shall 'ear."

Marshall shook hands with her, bowed to the girl who had risen and stood silent by the window, and went out.

Going down the stairs from Madame Delarey's suite to the carpeted, settee-spotted entrance hall of the great hotel, Marshall buttoned his coat, for, though the revolving door kept from him the full chill of the outer air, there was great difference between the normal temperature of the place and Madame Delarey's apartments.

"Childe Roland up to date," he murmured to himself as he went, "and what a dark tower!"

"Mr. Marshall?" The words came at him as he reached the last stair—Stephanie Delarey's voice. The thick pile of the carpet had permitted of her coming to him inaudibly; he turned and stood facing her, waiting.

"You will go—you will take up this search for Clement?" she asked; he saw that she looked fluttered, nervous, almost fearful—far different from the immobile being who had sat by the window while he talked with Madame Delarey.

"I will go," he answered. "I told your—I told Madame Delarey I would go."

She noted his faint annoyance, realized that it was to him as if she had questioned his word with regard to going. She looked to him somewhere in the early twenties, slight, tall, and—he would have said—daintily formed, but most of all he noted her agitation, nervousness.

She leaned toward him ever so little. "Will you take me with you?" she asked.

A pistol fired by his ear would not have startled him more than that abrupt request. "No," he answered promptly. "Why?"

Stephanie Delarey stood thoughtful; flung back on realities by the bald denial and equally bald query, she knew that the refusal had been inevitable, and blamed herself for the lack of tact that had led her to make such a request without preface, without explanation. But, at times, the little old lady whom she had just left drove her to tactless expedients.

"Unless you are in a hurry, I will tell you why," she answered.

"Your mother—won't she need you?" he asked.

"She is not my mother, and for the present she will not need me," Stephanie answered. "Let us sit down—here."

She led the way to one of the plush settees, and took a corner, smiling up at Marshall and inviting him to a seat by patting the cushion. The trepidant nervousness of the first minute had passed, and now, assessing him more coolly, she saw him as a personable man, exceptionally attractive by reason of the strength his face showed—and she liked his grey eyes. But she saw him more as a means to a possible end than as a man, and calculated her smile in exact proportion to the impression she wished to create in his mind.

"So she is not your mother?" Marshall suggested.

"My father married twice," Stephanie told him. "I was three months old when my mother died. Clement is my half-brother. For me, there were two beings, God and my father, both past questioning. I loved him, and in my sight he could do no wrong. It was his blood in the boy Clement, his fine sense, that sent him to Pierre at Sapelung instead of back to school. Little as I like Clement—"

"So?" Marshall said thoughtfully, not realizing that he interrupted her explanation.

"I want to be just!" she exclaimed, with almost fierce insistence. She felt that she must convince him of her utter sincerity, and he might yet reverse that initial refusal. For him, seen once, she cared nothing—for the chance of escape from her present life, everything.

"I think you would be, anyhow," he commented.

"Here—as I live now—it is not easy," she went on. "I, my father's daughter, am that woman's servant. I am bi- lingual, capable, penniless, dependent on her for everything—you know how difficult it would be to break away—for a girl—"

Marshall began to understand. "Worse than difficult," he agreed.

"And"—she felt it almost impossible to make real to him the hatefulness of her position, dependent on a woman whom she disliked—"you see why I want to escape? Oh, I have tried, again and again, and come to the conclusion that there is nothing but the streets. I am"—she laughed, nervously—"too attractive. They will not take me seriously. And I am a Delarey—she was a factory girl!"

There was something either magnificent or absurd in that claim—"I am a Delarey." With the quickness of intuition she saw its effect on him. "We are antithetical," she went on, before he could comment, "and life with her is not life. I have tried to get away—"

She felt that she had put her case badly—it was just another failure. Later, when she could look back and assess the matter coolly, she saw how impossible the thing she asked must have seemed to him, with only that little explanation to justify it.

"And so," she ended, "I want you to take me with you."

"No," he said again. "Consider it—I came in answer to your—to Madame Delarey's advertisement, and accepted a business proposal. It entails heaven knows what in the wilds—one man has got lost on it already, and to burden myself with a woman at the outset—I put this frankly as you have put your request to me. How could you come—sister, fiancée, wife—"

Suddenly she saw him as man, rather than as a means to an end. "I have not explained all," she said, hastily. "I wouldn't have you think of me as imposing—"

Marshall smiled. "I'm intensely sorry I see no way of helping you, that's all," he said.

"But—it is difficult to explain it all," she insisted. "Listen—if Clement had been living, she would have heard, she would have had word from him. Since he is dead, when there is proof of his death I shall inherit two million francs. You go to get that proof—when you have got it and so have made my inheritance mine, I will pay you to take me, as she pays you to go. It is that I may get away—this life is unbearable—you understand?"

"Fully," he answered, "but—"

"When I asked you, without explaining first, I did not consider the personal side. I—"

She paused, leaving him to guess what she would have said.

"It cannot be done," Marshall answered.

"Even if I could finance the two of us on those lines, which I can't, still it couldn't be done. I don't see—you don't know where a hunt like this may lead—I don't know myself, till I get there."

She sat silent, and from the quality of the silence he could sense her disappointment.

"Look here," he went on. "We're talking pretty frankly, for a first meeting. I'll make a suggestion, if you'll listen. It's a gamble, I know, but you might like to try it. I gather I shall be sailing for Batavia in about a fortnight."

Stephanie nodded. "In about that time," She agreed.

"Supposing you sold all the jewellery you have, raked up every penny possible, how much money could you lay hands on—of your own?" he asked bluntly.

She looked up at him, and down to calculate. "About three hundred pounds, I think," she answered.

"Not nearly enough to finance you out with me, in a suitable way," he commented, "but enough to last you a year in this country, going carefully. Now, as you said, I reckon that if I succeed on this search of mine, I shall come back with news of Clement's death. He'd not have kept silent so long if he had been living."

"He would not have kept silent," she agreed, speaking slowly. It was not of Clement that she was thinking, but of what might lie at the end of this train of postulates.

"And," Marshall went on, "if Clement Delarey is proved dead, you get your two million francs under your uncle's will?"

"That is so," she agreed.

"Then I suggest"—he paused to find words to clothe the suggestion—"that I find you a home for the time I'm away, of some sort that will let your three hundred pounds keep you for the year. I have a sister who would like you, and you might like her—it's easy to get you a little circle of friends and interests, through her. I suggest that you and I go through the ceremony of marriage before I go to hunt for your half- brother—the ceremony only—and when I come back with word of Clement Delarey's death you give me one fourth of your two million francs, and we get the marriage annulled. It won't be divorce, in all probability—only annulment. That is a way out for you."

She thought for a little time. "You may wish for other ties—regret it," she suggested.

"I believe that one woman is just as good as another, and as bad," he reported, cynically. "I've never fallen in love yet, and never shall. This is a business deal, to help you out."

"It is very generous," she said, "very good of you, Mr. Marshall, but I cannot accept it. I would have gone with you—"

"No," he said firmly, for the third time.

"Then"—she rose—"I shall see you again, when you come to settle with Madame Delarey about going out. I—I thank you for your offer, Mr. Marshall—good-bye."

Walking through the slush of the streets, Marshall smiled to himself. Adventurer from boyhood, he had never stumbled on such an adventure as this promised to be, and he felt glad that he had been free to embark on it. His thoughts reverted to Stephanie; the unthinking impulsiveness behind that "take me with you" was almost incredible, yet he could understand it. He pictured years of petty irritations, the girl's whole life reversed from the time of her father's death, and now an unreasoning impulse to seize on anything, any way out. Yet she had refused a far more reasonable way: assuming, as she might safely assume, that her half-brother was dead, a safer, easier way—

Stephanie Delarey went slowly back up the carpeted stairway, and as she went—

'"One woman is just as god as another, and as bad,'" she quoted to herself. "It is not true—clever, but not true."

She entered the room in which the little old lady had interviewed Marshall.

"Why are you so long away, girl?" her step-mother asked, querulously, with a vindictive look at her.

"There are no letters—I stayed for a while in the cool," Stephanie answered.

"Do not be impertinent—I will not 'ave your superiority—your insolence!" Madame Delarey announced, loudly.

Stephanie went to the window, making no answer.

"Why do you not speak—can you not speak?" Madame demanded. "This Marshall—'e is a good man—yes?"

"He is a man," Stephanie agreed, listlessly.

"'E will bring my dear son back—I feel 'e will succeed—not like the others. 'E is not like them."

"Perhaps," Stephanie said, with faint interest. The heat of the room oppressed her.

"Ah!" said the little old lady, vindictively. "You think of the two million francs for yourself if Clement die—you wicked girl!" Growing furious, she lapsed to her native tongue—"You have no heart, no affection—you are hateful, and the very bread you eat is at my expense! Clement shall judge your ingratitude, dependent as you are, when he comes—"

She paused to take breath, and then, staring at the closed door beyond which Stephanie had passed, called—

"Come back—come back—I need you!"

But, for almost the first time in their ill-assorted relationship to each other, Stephanie did not come back. She had gone to think things over, out of hearing of that nagging, persistent voice.

Three days later Marshall was ushered into the presence of the little old lady—he came in answer to a letter which enclosed voluminous instructions and information drawn out by a firm of solicitors, together with an agreement—he had already signed it—binding him to a year's undivided service in quest of Clement Delarey, dating from the sailing of the S.S. Sanjredim a fortnight hence. Stephanie bowed to him as he entered—coolly, he thought. In reality she was trepidant, not cool.

"Mr Victor Marshall, 'ere in this envelope is your passage ticket, with return," the little old lady said, without preface, placing her heavily jewelled fingers on the papers before her, "and 'ere is five 'undred pound bank notes. You 'ave the full instructions I tell the notary to send to you?"

"Yes," he answered. "Here is your agreement—signed. I suppose you know it is waste paper when I reach Sapelung—quite useless?"

"I do not know," she answered. "It is form—the notary 'e will 'ave it so, and I do not mind. You 'ave said you will go—I trust you, Mr Victor Marshall."

The reiteration of the full name annoyed him vaguely. "I will do my best," he promised.

"Then that is all." She stood up and held out her hand to him. "Bon voyage, and you take my prayers for success. You must bring 'im back to me—'e is all I 'ave."

"I will do my best," he repeated.

He paused at the foot of the stair on his way out, and there again Stephanie overtook him, as on his first visit. "I feared to miss you." she said, rather breathlessly.

"Well, you haven't," he answered, smiling.

"I wish"—she hesitated nervously—"to accept your proposal, since you will not take me with you."

Marshall stood silent for what seemed to her a long time. "To accept," he repeated at last.

She held out an envelope toward him.

"I have written it all down here—the half-million francs, the promise to annul—all, and signed it. If you will arrange, and let me know, I will be ready when you wish."

"I'm not sure—" he began thoughtfully.

"No—don't humiliate me so far—don't refuse!" she broke in. "Don't you see—it's not easy to say—I am driven—" She paused, inarticulate, almost desperate.

"My dear lady, I never dreamed of refusing," Marshall assured her. "A reasonable prospect of half a million francs in return for a mere formality is too good a chance to refuse. I'm not sure about the arrangements, that's all. As quickly as I can I'll make them, and I'll write and let you know, shall I?"

His matter-of-fact air restored her calm. "Thank you," she said. "I shall be ready at any time. But—it is not easy—will you make it as easy as you can for me?"

"I'll be consideration itself," he promised, smiling. "Regard it as what it is, a formal business deal, and you'll find it isn't very difficult. Look at it in that light."

She smiled back at him. "I am grateful," she said, holding out her hand. "Will you forgive me—I must go back, now."

"Then—au revoir, and I will write to tell you when," he said, and let her go.

She had come down to him fearful, dreading refusal. She went back smiling, almost happy, seeing a way out from the life she hated. And, as Marshall had bidden, she regarded it as a formal business deal.

IT wanted four days of Marshall's date of sailing when, having taken her morning cup of chocolate to Madame Delarey (which the fractious old lady would never allow a servant to bring into the room, since she had not put in her false teeth at that early hour), Stephanie rang the bell for the hall porter. She indicated a small trunk and a large suit case in her own room—

"A taxi for Charing Cross station, and put these on it, please," she said. "I shall be down in a minute."

When he had gone, she put on her coat and hat, collected a few personal belongings for which she had reserved an attaché case, and went down to the waiting taxi. At Charing Cross she saw her baggage safely into the cloakroom, and the next hour she spent shrunk into a corner of the chilly waiting-room. Marshall had appointed eleven o'clock for their meeting, but she had had to leave the hotel before Madame rose and made her toilet; this meant a full hour in the waiting room, a time of deadly fear lest somebody should track her out, take her back, and deliver her up to the terrible old woman from whom she was about to escape, with Marshall's help. Viewing her situation sanely, she knew full well that nobody had the power to take her thus, but yet there was the feeling, due to the years of subservience which her step-mother had imposed on her; it was an unreasoning fear, but not less real for that, and she felt that the time of waiting would never pass.

But nobody came to trouble her, until Marshall himself stood before her.

"Have you been waiting long?" he asked, by way of greeting.

"Fear made it seem long," she answered, smiling as she rose, "but it is all right, now. Where do we go first?"

"Registrar's," he answered. "The first thing is to alter your surname, so that everything's legal and straight. I gave your age as twenty-four—was that right?"

"A good guess," she answered, "only a year short of reality. And the other particulars?"

"Near enough—there's nobody to question. There'll be no informalities—unfortunately for you, it must be binding."

"Not more unfortunately for me than for you," she said, with some asperity. "It couldn't be a change for the worse."

"Thank you," Marshall said drily. He put up a hand for a taxi in the station yard.

Inside the taxi, she laid her hand on his arm. "Please, I am grateful to you, really," she said. "But you say things which sound so bitter—I can't help retorting."

"Well," he answered, reflectively, "you won't hear them much longer. As a matter of fact, it's I who ought to be grateful to you, really. A chance of half-a-million francs for a mere day of formalities—with a very charming companion to share them—is some cause for gratitude, you know."

There was a hint of satiric amusement in his way of uttering the compliment, and Stephanie made no answer. She felt that she almost hated him for this coolness, this utter disregard for all but the business deal involved in the adventure; she had yet to realize that he adopted the only attitude such a situation would admit.

She was never able, after, to determine the location of that registry office. She retained a memory of passing St. Pancras station, and another memory of spoken words, shabby witnesses signing, somebody speaking a formal and unmeaning phrase of congratulation, and of emerging to the cold of the winter day and finding the taxi driver stamping back and forth to warm himself.

"An' a fine pair you make, sir, if I may say so," he told Marshall, as he held the door of the cab open.

"My good man," Marshall said, "every couple is not a pair, as you ought to know. Make for Gennaro's."

At the little restaurant, where they seemed to know him very well, a secluded corner table was reserved. Marshall consulted Stephanie as to her taste in wine, ordered lunch with discrimination, and eyed the initial cocktails approvingly. He took up his glass—

"Mrs. Marshall," he said, lightly, "I'm glad to have the honour of drinking your health on this auspicious occasion—" He put the glass down, again, suddenly. "Why, child, what on earth's the matter?"

For, instead of responding as he had expected, she pushed her glass away and sobbed, almost noiselessly, till the tears trickled between her fingers in spite of her handkerchief. Marshall got up and stood beside her.

"Go away—I'll call you," he said to the waiter who appeared. "Stephanie—child—I wouldn't hurt you for the world—it's all to help you through—"

Suddenly he realized how much he wanted her through, and in the realization gathered something of the cause of this outbreak. But Stephanie, controlling herself, showed him a wet, smiling face—

"It's all right," she said, "just a fit of nerves. You can't—you wouldn't understand, if I told you."

After a pause he went back to his seat. "Perhaps I do understand," he said, soberly. "Anyhow, I'll drink to your happiness when the real day comes and this muddle is over."

"And I to yours," she answered. "May it reward you for your kindness to me."

Marshall beckoned to the waiter. "Fully paid, don't forget," he reminded her. "A purely business deal."

She let it pass in silence, His insistence on the point might be due to consideration for her, but it was none the less irritating.

"Where do we go next?" she asked, after a silence.

"To my bank, before it closes, to open an account for you," he answered. "You brought your capital with you, I hope?"

"It's not all money," she explained. "Most is jewellery that I want you to sell, for me."

"And how do you know I won't bolt with the proceeds of the sale?" he asked.

"If I did not know, I should not be here," she answered, coldly. "I wish you would be yourself—not pretend."

"You'll trust less easily after being deceived a few times," he commented, more seriously. "There's something about you so youthful, inexperienced—as if you had been bottled away somewhere instead of living. You seem too trusting."

"Some people one can always trust—you are one," she answered. "Shall we take that for granted?"

"Consider it done," he agreed. "Well fix up your account at the bank under your new signature, and then, unless you have any calls to make, there'll be time for tea and a cinema or any other wild dissipation that may appeal to you, before I take you up to my sister and spring the surprise of her life on her."

Stephanie stared at him. "You have not told her?" she asked.

Marshall shook his head and grinned like a schoolboy. "It would have been bad policy," he said. "Confront her with the deed accomplished, and the trick's done. A woman always hates the girl her brother is going to marry, unless she chooses that girl for him. She may like his wife, if she's wise as well as clever—like my sister."

"Is she married herself?" Stephanie asked. For the first time she realized that she knew absolutely nothing about the man before her, nothing about his life and people—

Marshall nodded. "Not so much as her husband is, poor chap," he said. "They live up at Golders Green, and I keep two rooms in the house while I'm in England. I leave it to you to decide whether you retain those two rooms for my time away, or find others. You'd better see my sister first, to judge whether you can stand her."

Stephanie reflected, and shook her head slowly. "It would not be wise," she said, "we shall be better friends in the end if we keep quite apart."

"It doesn't apply," he pointed out. "There is only the matter of my year away—after that, you needn't bother about my sister, or about me—you seem to forget that."

"I had forgotten it," she agreed, smiling.

Growing used to her presence, he felt that he had no great wish for her to remember the temporary nature of their contract. "Well, anyhow, I'll have a talk over things with her before I go, and get her to help you in finding a place for yourself—if you still think of doing so after you've seen her."

"There was one thing, arising out of your bargain with my stepmother," Stephanie said, "that I wanted to remind you of. You insisted that Pierre, at Sapelung, should not know you were going out to search for Clement."

"Well?" he asked. "It may be unnecessary, but on the other hand it may be very necessary. Don't forget that three men went by way of Pierre, and they have all vanished. It may be coincidence, but—"

She made a little gesture that implied he had misunderstood her intent in speaking. "Not that," she said. "It occurred to me—the solicitors who drew up the agreement—I do not know, but Pierre is joint heir with me, and they may be in communication with him. If they are, I don't see how you can go without his knowing—to Sapelung."

Marshall considered it, silently.

"Thanks," he said at last, "it was good of you to point it out—I had overlooked that possibility. I think I see a way round it, though."

"And—you'll write to me if anything happens?" she asked.

"Not unless?" he asked in turn.

"Why should you?" she countered, quickly.

Marshall looked steadily at her. "Do you happen to have a pocket mirror about you?" he inquired.

"But that," she said, "is foolishness. Besides, it is outside our compact."

"Technically," he agreed, "but it's a bit annoying that a man mayn't—never mind, though."

She did not ask him to complete the sentence. Instead, she looked at him in a rather scared way, as if she feared lest she had merely exchanged one disability for another. He smiled when he saw the look.

"Don't worry," he said. "In four days' time you'll have nothing to worry about."

For the rest of the day he was consideration itself, and he kept her occupied to the exclusion of thought, even resorting to the threatened cinema entertainment.

Then he took her up by taxi to Golders Green, and on to the house in Bearnais Road where his sister lived, a smaller and more alert copy of himself. She stared, voicelessly, at sight of the strange girl and her trunk and suitcase.

"Stephanie," Marshal said, "this is my sister Elizabeth, always called Bob for short. Bob, I have the honour to introduce my wife."

Bob looked at him as if unwilling rather than unable to believe it of him, but he nodded confirmation. Then she laid her hands on Stephanie's shoulders and kissed her.

"I do not understand," Stephanie said, the tears in her eyes. "Why are you so good to me!"

"Come," Bob said. "I'll show you the way to Victor's room while he gets rid of the cab. You'll soon get used to our little habits. I'm used to his trick of springing surprises, though this is a little bit out of the ordinary, even for him."

She took Stephanie off, and Marshall, after dismissing the cabman, went to inform his brother-in-law in the dining-room of his latest venture.

"What did Bob say?" asked Harry Crawford, Bob's husband.

"Just nothing," Marshall answered. "She seemed to be doing a power of thinking."

Crawford observed, "Bob beats you in some ways, Victor."

Then Stephanie and Bob came back. The four of them had a rather constrained meal together, and, after, Marshall took Stephanie up to his sitting-room.

"Well," he said "you're fixed. I think everything's settled, isn't it?"

She nodded assent. "You have been more than good to me," she answered. "If you knew what it felt like to know that I shall not go back there—to her—"

"Nothing more you want?" Marshall asked.

"Nothing."

She faced him in these new surroundings, smiling, more content and at rest than he had seen her, before. She seemed to take for granted that all would be well, now. Marshall half turned away, and swung back toward her—

"Supposing—supposing—Stephanie—" he said, awkwardly, and hesitated. "If it were real—"

Her smile vanished. She looked at him steadily.

Marshall made a curious gesture, half of negation, half of dismay.

"Good-night, Stephanie." He offered his hand.

Before he could prevent her, she had bent and kissed it.

"You make me ashamed," she said.

Marshall laughed, lightly. "Wait till I claim my half- million," he said, and left her.

"Well?" he asked his sister, down in the dining-room.

Bob laughed. "Give me time to find out," she answered. "I like the first impression."

"You had to say that much," he observed. "Now—look after her, Bob. I've got to leave. I may see you more than once again before I sail, and I may not—there's much to be done."

"You're not leaving her here alone?" she asked, incredulously.

"Just that," he answered, "and it may be of the utmost importance—it may mean as much as half a million francs to me—that you should be absolutely certain I left her here alone, tonight. Remember that."

She looked her questioning, but did not voice it. Victor was always making mysteries, though this looked by far the most mysterious of any in her experience.

"She'll tell you all about it, probably, if you ask her," he said. "Take care of her—she's a bit unworldly, in some ways. Help her if she needs help"—he looked past her to the clock on the mantel—"good-night, Bob—I'm off."

THE S.S. Sanjredim had a good deal of cargo to discharge at Colombo, and Mr Victor Marshall, in common with the great majority of the passengers, filled in time by going ashore. He went in company with Mr Obadiah S. Fetherboom, a very talkative American who was on his way to revolutionise Rangoon—for a start—by means of internal combustion engine pumping sets, lighting sets, haulage sets, and various other sets. Obadiah, who had yet to see Rangoon, guessed it was an unenlightened village, and calculated that a couple of his pumping sets would make a dry ditch of that little creek, the Irrawaddy. Marshall, who thoroughly enjoyed Obadiah, solicited the honour of his company for a look round Colombo, and got it.

The hatches were on again, and there were but twenty minutes to go before the Sanjredim should turn her nose seaward, when Obadiah came up the side again, two coolies helping. His panama hat had suffered a three-cornered tear, and his hair stuck through the hole; he had the beginnings of a black eye, and his tussore coat looked as if a vacuum cleaner would be more use on it than a mere clothes brush; a dingy bath towel, tied round his left knee, announced that his trousers had not escaped the cataclysm, but still he stated sonorously and repeatedly that he desired to be taken back to old Kentucky—he had a fine baritone voice—and seemed content to stay on deck without alterations. The purser, in his capacity of universal friend and helper, tried to persuade Obadiah to retire for repairs, and thus was first to learn that if Obadiah were bad, Marshall was worse, for he had not come back at all—this as the Sanjredim went out.

He was a son of a snipe and a broken-toothed buzz-saw, a cock- eyed, rubbernecked, misbegotten rum barrel. He had lured Obadiah to a shack in a block down in the never-never district, where they found lovely ladies who offered lovelier bottles with a twist that would make any guy gargle. Obadiah himself had not so much had a drink as been struck by lightning, and Marshall had got stuck up with a fellow who handed out the glad mit and froze to him like a bronco buster to a bottle of old rye. And the fuller they got the thicker they got, till Obadiah got his dander riz because Marshall was too sozzled to think about quitting the picnic before sailing time.

They had a little discussion, and Marshall managed to stop on his feet long enough to sock Obadiah one in the optical apparatus, but he fell down again before Obadiah could sock him one back, and went to sleep. Gabriel's trump wouldn't wake him till he'd slept off some of the bottled earthquake they'd been drinking; Obadiah tried to get a gharry, or a traction engine, or something, but they were in an alley so narrow that a fly couldn't crawl down it sideways, and he had to go nearly half a mile before he found a wooden mouse-trap on wheels. When he came back in that to where he judged he had left Marshall, there were seventeen alleys up which a thin guy would have to go edgeways, and Marshall had blazed no trail. So Obadiah had to come away lest Rangoon should remain uncivilized, and, anyhow, Mr. Marshall was old enough and healthy enough to come in out of the rain without being pulled.

By the time all this story had been told, the Sanjredim had got to open sea, minus a passenger. The purser overhauled such belongings as Marshall had left on board, and decided that they were not worth bothering about; apparently, said the purser with some contempt, this was the sort of man who travelled with his toothbrush in his hatband and bought a clean handkerchief once a week, the day he turned his collar. He could apply to the agency of the line at Colombo, or to the police, or to the devil—it was his own fault, anyhow. Obadiah, his elation replaced by deep and dyspeptic gloom, nursed a thunderously black eye and agreed, heartily.

All over the East, from the Straits to the Solomons and down to Viti Levu, Sapelungs abound, differing from each other in size and in the quality of their trade, replacing the Eurasians in the north by aboriginal races in the south, but serving each the same purpose as the rest, and monotonously beautiful—from a distance in fine weather—after two or three have been visited. The navigators of old time, as they touched at each of the islands, found and noted its best natural harbour, and there the chief port of each island has accreted as needs have directed.

Sapelung itself spread round the upper end of an inlet, with Government House nestling white and splendid in the foliage that clothed the first rise of the hills at the back of the port. A solidly built jetty gave accommodation for the fortnightly steamer which brought the mails, and for such tramps and traders as had occasion to visit the place, and the main trading avenue went up, a white and dusty highway of which the refracted glare was almost painful in the dry season, from the end of the jetty toward Government House.

To right and left of this avenue, palm-bordered roads extended transversely; to the left, toward the point where the lighthouse stood, were the houses of the few white people of the town, the club buildings, and the inevitable race-course; to the right was the cosmopolitan rather than native quarter, tenanted by de Souzas and Martinezes from Goa, by Ah Lings and Foo Chengs from anywhere between Hankow and Peking, by coolies from the docks, Kanakas, labourers from the rubber plantations, and all the wash and waste of peoples that eddy into and out of the harbours of the East.

Sapelung, with rubber for its chief industry and hopes of an infant sugar-growing enterprise, was no better than the rest of its kind, and no worse; no busier, and no lazier. It was the sign manual of the West set on this fragment of the East, as indication that the hinterland beyond was marked for subjugation. Already the rubber plantations stretched for miles, and the plans were out for a railway, while after-dinner speakers at Government House no longer spoke of the place as an Outpost of Empire, but as One of the Bright Gems which add lustre to the Heritage of Our Race. Put into plain English, this meant that the aborigines—round about Sapelung itself, for the country beyond the first range of hills was still largely unexplored—had forgotten the tastes of long pig, and knew which end of the human frame a pair of trousers was designed to cover, while commercial travellers were more welcome than missionaries.

On the left of the white highway leading up from the jetty toward Government House, a straggling edifice of wood and plaster bore, in big black letters sprawled across its front, the legend—Jean Delarey et Fils, Agents. The vague description covered practically every branch of trading; Pierre Delarey, young, dark, almost too alert for this climate, presided over a couple of score of clerks of many colours and languages, and through them he would procure anything from a stamp album to a steam shovel, from a pie dish to a pickaxe. Jean Delarey, his father, had come to Sapelung in the days when one was borne ashore on the shoulders of coolies through the surf, and had contracted for all the material of which the jetty was built.

Pierre, at his death, had come to full ownership of the principal business of its kind in Sapelung, and, since he followed his father's rule of never refusing a commission, Delarey's remained the chief agency of the place. There was a legend to the effect that Pierre Delarey had once, at the request of an eccentric client, indented for a pair of dental forceps for an elephant and submitted blue prints of different patterns, but, since there were no elephants in or near Sapelung, they told this tale to newcomers, and followed it up with a description of the pipe line through which the raw rubber was pumped from the plantations at the back into tank steamers.

As was his custom, Pierre Delarey went down to the jetty to see the mail boat in—the particular mail boat which brought a solitary passenger transferred from the Sanjredim, a rubber man back from leave. Pierre took him up to the club, with a view to learning the news of the voyage, and anything else he could.

"We lost a man at Colombo," the rubber man told him, among other things. "Nice, quiet sort of man he seemed—chap named Marshall. Must have been a holy terror when he got loose, though—he took a Yankee ashore to show him round, and when the Yankee came back he looked as if Marshall had stood him on one ear and twirled, him."

"What became of Marshall?" Pierre asked, carelessly—almost too carelessly, except that the rubber man could know nothing.

The rubber man shook his head, "Strayed," he answered. "Too drunk to get back—cleaned out and jailed, probably."

Pierre nodded, contentedly. "Funny thing," he said.

"Not a bit," said the rubber man. "I judged him a born beach- comber, after that, though he seemed quiet enough before we got there. Probably he was about three days in advance of a warrant for bigamy, or something."

Pierre, who let the subject drop, haunted the jetty for weeks after, if the smoke of a steamer showed out beyond the point, but no Marshall appeared. But one day there dropped off a tramp from Penang a quiet Englishman who limped slightly—the rubber man had long since gone back to his work—one who moved slowly, as if he were convalescing after illness. His name, Pierre ascertained, was Walker, and he intended to recuperate in Sapelung, and then go up the country at the back, shooting. As he wanted a gun and equipment, he came to Jean Delarey et Fils.

"Any old gun," he explained, "so long as you've got stuff to fit it. I can't afford high prices."

They sold him a rather ancient second-hand breach-loader with one barrel rifled and one for shot, a plain and serviceable gun. They sold him, too, revolver cartridges, and leggings, and meat lozenges, and quinine and simple medicines. Evidently, from the way in which he made his purchases, he was no greenhorn, and Pierre, after a business chat, invited him to lunch at the club; such a man was worth cultivating, in view of possible future business—Pierre never neglected chances.

For a man of French descent, Pierre was very English; he was sympathetically interested in Walker's project of shooting out back from Sapelung, and gently discouraging.

"It is not often done," he said, over the liqueurs. "Possibly half a dozen men have tried it, but—well, Mr. Walker"—in a burst of confidence—"the fact is that there is practically nothing to shoot."

"A slight drawback, certainly," Walker answered, thoughtfully. "Then, I conclude, my predecessors came back disgusted?"

"When they came back—yes," Pierre agreed.

Walker let the implication pass. "What is the country like?" he inquired. "I had heard that there were some good game tracts."

"There were, this side the hills, but they are under rubber, now," Pierre told him.

"You must cross inland by the pass, there"—he indicated a wedge-shaped cut in the hills beyond Government House, visible from where they sat—"and then you get lost. There is scrub for a few miles, and then thick jungle, with no paths but wild pig and leopard tracks—"

"Leopards don't make tracks," Walker interrupted gravely, ignoring Pierre's previous statement about the non-existence of game.

"And not all the others came back," Pierre concluded, with thoughtful irrelevance.

"Dead?" Walker asked.

Pierre gestured, non-committal. "How shall we know, here in Sapelung?" he asked. "We are business men—they came here like you, as men of leisure. They may have gone off from some other point along the coast, they may be hunting yet, settled in native villages, lost in jungle—anything. One might search for years, in the country back of the hills, and find nothing at the end."

He seemed anxious to convey an impression, rather than to make a definite statement, to disapprove without showing any desire to influence the man before him.

"Who were these others?" Walker asked point-blank.

"There was a man—a man named Whauple," Pierre answered slowly—perhaps reluctantly. "And there was another man, Pernaud. And—"

He paused on the word. Walker waited vainly for him to continue.

"No," he said at last, "it is not good shooting country."

"Is it interesting?" Walker asked. "I heard it was."

Pierre shook his head. "There are tales," he said, "but here—we grow rubber, hope to grow sugar, buy and sell—we know up to the pass, there. Beyond, there are tales. A volcanic belt—hot springs, they say, and a crater or two, very dusty. Impassable jungle, fever, marshland, malaria, uncivilized natives—some of them still use poison for tipping their arrows, I believe—"

Again he paused, watching his auditor's face narrowly; the scrutiny told him nothing.

"If you change your mind, I will buy back your outfit," he concluded, with an engaging smile.

"I will let you know if I change my mind," Walker answered.

They sat silent for quite a long time, though the liqueur glasses were empty.

"In any case, you will not go alone," Pierre suggested.

Walker considered it. "I think I shall take a local," he answered. "Maybe a Chinese guide. They are cheap, and very good, and they don't sicken easily. Know any?"

"I think I can recommend you one or two," Pierre offered.

"'Many thanks," Walker said. "It is very good of you—that is, if I don't change my mind."

Pierre, due back at his store, looked at his watch. "If you will excuse me—?" he suggested.

Walker, with a half-smile on his face, watched this very English Frenchman walk alertly down toward his place of business, from the end of the club veranda. Then he came back, and, sitting down again, looked up at the wedge-shaped cut in the hills through which, if Pierre spoke truly, the man named Whauple had gone—had any other gone that way?

There was a medical missionary, Mackeller by name, at the club, and Walker got into conversation with him. He was merely waiting for a boat from Sapelung, he said, but he had worked in the place when the rubber planting industry was just beginning—that was years before. He remembered how chicken- pox had first come as a scourge; the natives had died like flies, and they said that out at the back, beyond the hills, a white man would be more hunted than hunter still, if he got into the uncivilized areas; such villages as there were in the lowlands had the chicken-pox as a legend of death that the white men carried, and it was odd, in Mackeller's opinion, that Delarey had not mentioned this.

Walker spoke of Pernaud and Whauple; Mackeller had heard of Pernaud, who, it was generally supposed, had died inland. Sapelung was a place of comings and goings, apart from its rubber interests; if a man chose to go inland, they told him what he was up against, and (here the missionary confirmed Pierre) it was nobody's business to go after him, for the nature of the country made search hopeless. Mackeller believed Pernaud had gone looking for somebody else, but knew little about that; Pernaud had first come out to Delarey with another man, Benson, and Benson had gone off to Java in Delarey's employ—he was in Java yet, Mackeller believed, though he was not certain. Then there had been Delarey's young cousin, a boy who had come out and gone off on that ridiculous old story of Mah-Eng.

Here Walker grew very interested. "Who is Mah-Eng?" he asked.

Mackeller smiled. "It is a place, not a person—if it exists," he said. "So far as one can tell. It is a mere legend that has grown up out of lack of knowledge of the native dialects. People misunderstand words and phrases, build up a myth."

"Probably," Walker said, with a note of doubt.

Mackeller smiled. "Mah-Eng is as mythical as Kir-Asa, or any other of the yarns they tell in Pacific ports. It was a fairly common story in the early days, but rubber planting has proved that the further you clear the country inland, the less you find. There is not so much talk about it, now."

"What was the story?" Walker asked.

"They used to say that Mah-Eng was a mine of some sort, I believe, and then there was another belief that it was a temple in the jungle, hidden treasure house, or something of the sort. Then they said it was a mine the early navigators of these seas had worked, but there is no trace of any such working, and no trace, either, of gold or gems along the hills at the back—no geological indication of anything of mineral value, with the exception of a thin stratum of mica. Mineralogists put that story of Mah-Eng with the squared circle and the sea serpent, and so do I."

"And Delarey's cousin didn't," Walker commented, thoughtfully.

"It seems rather strange," Mackeller said, "that Delarey didn't mention him, when he was telling you of the men who have gone inland. The facts about the boy were enough to call for mention."

"Yes?" Walker asked.

"Yes," Mackeller said. "It was generally known in Sapelung, a month or two after the boy had gone—his name was Delarey, too—that he had inherited millions. Evilly disposed people say that Pierre Delarey is waiting for a full seven years for the time of his cousin's disappearance to elapse, since he can't get proof of his death, and when the time is up he will go to France, or perhaps it is England, and claim the inheritance. He is entitled to it at his cousin's death."

"They say that, do they?" Walker commented.

"It is common knowledge in Sapelung," Mackeller answered.

They talked for a while longer, Walker deeply interested in all that Mackeller had to tell. He gathered, more by manner than through statement, that Mackeller had no great love for Pierre Delarey. Before they parted he asked Mackeller to come and dine with him that evening.

"You've told me a good deal that I wanted to hear from an unprejudiced source," he explained, "and I think I want your advice."

"And," said Mackeller, smiling, "if it agrees with your inclinations, you'll follow it."

Walker smiled too. "Anyhow," he said, "if you'll come, I have a tale or two to tell, and Mrs. Martinez—my landlady—is a good cook. It seems that you know more about this place than anyone I've met so far—we can have a talk—"

Mackeller agreed. He had nothing to do but wait for his boat, and out of this first meeting he had acquired a liking for Walker.

MRS. MARTINEZ produced a duck as pièce de

résistance, and when Walker and Mackeller had laid bare the

skeleton the missionary leaned back and confessed that one big

dish for dinner, like this, was a relief after picking over

unsatisfying courses at the club. Later, the two went out on to

the bit of veranda apportioned to Walker's use, and mused awhile

in rocking chairs.

"You spoke of asking advice," Mackeller suggested.

"There's a story first," Walker answered. "It's about a man named Marshall."

"Who got himself jailed in Colombo—that's the Marshall you mean?" Mackeller half-questioned. The rubber man, up at the club, had told the story of Obadiah's amusing return to the Sanjredim, many times.

"Perhaps," said Walker. "Marshall was engaged by Clement Delarey's mother to find Clement. Pernaud and Benson were first employed by her, then Whauple was employed, and then Marshall. And though the old lady hadn't begun to suspect Pierre of any designs on his cousin Clement, Marshall had, as soon as he heard the story of the others."

"If Pernaud and Benson were her men, there's ground for suspicion," Mackeller commented thoughtfully.

"Therefore, Marshall got very carefully and thoroughly lost at Colombo, with a very capable man to advertise the fact, and came on here as Walker to save Pierre Delarey the trouble of plotting his disappearance. I believe you're a straight man, Mr. Mackeller, and so don't mind telling you, and in any case Pierre has shown his own hand to me enough to draw his claws. You told me some few things up at the club—"

"It was a clever move, that piece of acting at Colombo," Mackeller said. "Clever, that is, if you mean to carry this thing any further."

"Why the doubt?" Marshall asked.

"Clement Delarey has been lost nearly, four years, now," Mackeller explained, "and so it's a cold trail. You surmise that Pierre is responsible for Clement's disappearance—death, perhaps—and now you tell me that Clement's mother sent those other three men I'm inclined to agree with you. But you can't prove anything against him—Pierre Delarey is a very able man, and something of a power here as well."

"Probably that's all true," Marshall agreed composedly.

"Then what can you do—what steps can you take?"

"I can find Clement, or his bones, or the pot he was cooked in—I don't for one minute think I shall find him living, but I can take the road he took to this myth of yours, Mah-Eng, and get as far along that road as he got, most probably. Anyhow, I gave my word to his mother, and I don't turn back while there's a chance."

Mackeller considered it. "Do you know what you propose?" he asked. "Remember what I told you about chicken-pox inland, and the attitude of the natives toward any white man in consequence of it?"

"I have it all stored away," Marshall answered quietly, "but I'm not frightened. Either there's a man—or maybe two men—somewhere on the other side of the hills and unable to get back, or else there's a bill for two deaths to be presented to Pierre Delarey. Either there will be another death to go on the bill, or, more likely, I will present it to Pierre as it is—or else I'll bring Clement back. I want your advice as to the best way to find where Clement believed he would find Mah- Eng."

Mackeller was silent for a long time. Marshall lighted a cigarette and waited; there was light enough out on the veranda to show him the thoughtful frown on the missionary's face.

"I think," Mackeller said slowly, "you've bitten off a very large piece—you'll need strong jaws to chew it. Remember—all Pierre had to do was to let Clement go inland, a boy on a treasure hunt—the first native village he came on would do the rest. As for Mah-Eng, it's a myth, a superstition."

Marshall smiled. "Very probably," he agreed. "What do you suggest I ought to do?"

"Frankly, I don't know," Mackeller answered. "You have no real ground for accusing Pierre, you have nothing definite to take you on from here—what do you propose to do?"

"To put it more colloquially than politely," Marshall said, "I intend to see this thing through or bust. I've undertaken a contract, and it will be fulfilled to the limit of my ability. The first thing is to look for traces of Clement, settle what happened to him."

"I like to hear a man talk like that," Mackeller observed.

The bulky figure of Mrs Martinez came out of the shadows. "Mr. Walker, there is a gentleman wishes to speak to you," she said, in the clipped, unpunctuated English of her kind.

"Name, please, Mrs Martinez," Marshall answered. "I am already engaged with this gentleman here."

"His name, too, is Walker and he wishes to see you about your shooting trip he is a verree good young man," the lady intoned.

Marshall turned to Mackeller. "This may be interesting," he said. "Do you mind if I have him up here?"

"Not a bit," Mackeller assured him. "I'm interested."

"Show the gentleman out here, Mrs Martinez," Marshall said gravely, "and I'll deal with him."

She waddled away, to return with a slim, dark youth, obviously Eurasian—the faint light of the veranda gave no more detail—who faced the two men with perfect assurance.

"You wished to speak to me, Mr Walker?" Marshall asked.

"Yes, Mr. Walker," said the new arrival. "My friend, Mr de Souza, up at the club, told me you were looking for a man to go on a shooting exploration." He threw out his chest and made the most of his inches. "I, sir, am that man."

Marshall smiled; Mackeller nearly laughed outright; the perky, dandified little figure before them—its duplicates may be found by the score on office stools throughout the East—looked so utterly incongruous with Marshall's requirements.

"And what are your qualifications for a shooting trip?" Marshall asked, amusedly.

"Failed. B.A., sir," the applicant answered promptly—he was used to putting that qualification first in applying for clerkships. "Also, sir, patrol leader, Boy Scouts, verree good shot, cook, make camp, much tracking experience—" He hesitated, confused, for Marshall was smiling more and more broadly. Mackeller got up and went to the edge of the veranda, so that his face was in shadow.

"Sir," said this other Walker, in a tone of injured dignity, "I did not come to you for one gentleman to insult another, but in good faith to offer you my services. I have the honour, sir, to wish you good-night."

"Wait a bit," Marshall advised, more seriously. "I want a guide to Mah-Eng—have you ever heard of the place?" He judged that the instinct for romantic adventure that is grained in every Boy Scout, no matter what his nationality may be, would make this youngster a useful informant on that subject.

"I will show you the direction of Mah-Eng, sir, if you will engage me," Walker promised, with less of offended hauteur.

"But you won't go there with me," Marshall commented, carelessly, "because there is no such place."

"On the contraree, sir, it is a verree real place," the youth assured him, "but I do not wish to go, because nobodee who goes to Mah-Eng ever comes back, and my young lady would not hear of my engaging on so dangerous adventure:"

Mackeller came back to his rocking chair, and, seating himself, looked fixedly at the youth. Marshall indicated another chair, back in the shadow. "Draw that up and sit down, Mr. Walker," he invited. "You are a most picturesque exponent of romance, to put it mildly, and good stories always interest me, but don't be offended if I shout for the salt cellar." He waited while the slim youngster brought the chair forward and seated himself gingerly. "Now tell me—why don't they come back?"

Walker looked rather scared at what promised to become an inquisition. "Sir," he said, "I do not know. But when I was a boy, before I assumed the responsibilities of manhood and failed B.A., I took my patrol out to camp in the rubber plantations, and as good scouts should, we tried to learn anything that might be learned about this verree mysterious place. One of the labourers on the plantation, investigated by one of us, told us what we asked about the country on the other side of the hills, where the ground will not grow rubber, and he told us that there is a place called by the natives Mah-Eng, a place from which nobodee ever comes back. The natives inland know of it and will not go near it, but he could not tell us why nobodee ever comes back. But he said that nobodee ever comes back, and—" He left the obvious conclusion of the sentence unspoken.

"And nobody ever comes back," Marshall ended it for him, gravely.

"Carbon dioxide, or some sort of poisonous gas pervading a sunk valley," Mackeller suggested, "or pure romance."

Marshall reflected over it. "What is your Christian name, Walker?" he asked abruptly.

"Henry Aloysius, sir, failed B.A.," Walker answered promptly.

"I should recommend you to forget that failure. Do you know any of the native dialects about here—apart from bad English and cuss words—any of the talk they are likely to use on the other side of the hills?"

"I am conversant with the languages of the countree," Walker replied, again with a hint of offended dignity.

"Well," Marshall concluded. "One word to any person at all, even to your young lady, will damn your chance of coming with me on a shooting trip—I require absolute silence of you till you come to me at three o'clock tomorrow afternoon for my final decision."

"I will be dumb, sir, as a whited sepulchre," Henry Aloysius promised. "And I may conclude that my application has impressed you favourablee?"

"You may conclude anything you like, till three o'clock tomorrow," Marshall answered. "Meanwhile—your friend de Souza—how did he get to know about this?"

"Mr. de Souza is a waiter at the club, sir—he had the honour of executing Mr Delarey's orders at lunch."

"Thank you—I shall expect you at three," Marshall told him.

"Well?" he asked Mackeller, when the youth had bowed himself away with elaborate obsequiousness.

"The most erratic race on the earth," Mackeller answered. "Besides, he wouldn't last half a day in bush country—the breed has no stamina, and he'd sicken at once."

"Possibly—it was because of that I wanted to see him in daylight. Anyhow, we know a little more about Mah-Eng, now."

"Carbone dioxide, or pure romance," Mackeller insisted. "Mr. Marshall, my advice—not as Pierre Delarey advised you, but because I'd hate to see a man like you thrown away—is that you don't risk going inland on a cold trail. It's folly."

Marshall smiled. "I intend to look for this Mah-Eng," he said. "It's my job, obviously, and—would you back out, now?"

After a minute or so of silence, Mackeller laughed. "I wish I were coming with you, instead of catching the next boat south," he answered. "The country behind this coast line has always had an attraction for me, but I've never been able to go inland."

"I'd sooner have you with me than any man in Sapelung," Marshall reflected. "Take a month off, and try it."

Mackeller shook his head. "I wish I could," he answered with a sigh of regret, "but, like you, I have to stick to my job. I want to hear your story, though—you wont' find any Mah-Eng, in spite of Henry Aloysius Walker and his account of it, but you'll have a tale to tell."

"The tale of Clement Delarey, I hope," Marshall said, soberly.

"I notice you expect to bring back the tale—not the man," Mackeller observed.

"You have formed a theory?"

Marshall nodded. "You saw how the vague legend of Mah-Eng had gripped this Eurasian boy, Walker?" he asked.

"As it would any boy," Mackeller agreed.

"Clement Delarey came out to his cousin—he wanted to make enough money to redeem a debt incurred by his dead father," Marshall said, slowly. "Pierre got the news of his cousin's inheritance in some way and instead of passing it on he told Clement this romance of Mah-Eng—buried treasure, or something of the sort that fired the boy's Imagination and made him eager for the adventure. Pierre encouraged him in it, got him to go, and sat tight. Then Pernaud and Benson came. Pierre managed to buy Benson, because two might have got through where one couldn't. Since neither Clement nor Pernaud came back, Pierre trusted in the chicken-pox scare and let Whauple go on, probably quite alone. Perfectly simple and perfectly safe—and Pierre has about three years more to wait before he lays hands on a fortune that will make his store look like a hawker's tray by comparison."

Mackeller nodded thoughtfully, repeatedly. "I agree," he said.

For a time they smoked in silence; a little breeze from off the water rustled the tamarisks in the compound and cooled the tropic night; beyond the veranda edge fireflies gleamed transiently in the darkness; they faced inland, and the late moon, not yet risen above the range of hills before them, silhouetted the distant crests against the night sky, and showed up the wedge-shaped cut of the pass. Marshall Imagined the boy Clement going up through the pass with all the rash confidence of youth, perhaps turning to look back and down on Sapelung as he went, in utter confidence that he would return with his task accomplished, and bearing the means to clear his father's name.

"Why do you refuse to believe in this place, Mah-Eng?" he asked.

"Why should I believe in it?" Mackeller asked in return, lazily.

Marshall gazed up at the pass. "It's sixty miles across from here to the sea, in a straight line the way we're facing," he said, "and that pass is a bare ten miles from here. You've got a belt of rubber plantations this side of it, where the soil admits, up and down the coast, but neither you nor any other man seems to know what actually lies behind that range of hills—everybody is so busy this side that they haven't time to look over."

"The soil is no use for plantations, east of the hills," Mackeller explained, "and there are no minerals—no metals."

"There's forty miles of unmapped jungle, which may hold anything on earth."

"You might say the same of Western Australia, or of any unsurveyed tract," Mackeller pointed out, with obvious scepticism. "I've been first man over a good deal of new country, and I've heard yarns without end from Singapore to the Solomons, but I never heard of one being proved yet."

Marshall did not answer. From behind the hill crests the moon came into view, making silver magic of the night. Mackeller rose, reluctantly.

"It has been a really refreshing evening," he said, with sincerity. "If I can help you in any way, by advice—or by anything—you have only to let me know—"

* * * * *

BOB CRAWFORD, frowning over a crochet pattern and counting inaudibly, made a sign to impose silence as her sister-in-law entered the room. Stephanie, a radiant being compared with the girl Marshall had first met—six weeks of freedom from Madame Delarey had caused the difference—came to look at the work.

"Now," said Bob, putting the pattern down, "what is it? Stephanie, you grow prettier every day."

"This is mail day," Stephanie answered. "You don't think anything has happened to him, do you?"

Bob laughed at the suggestion. "I might have thought it if he had written," she said. "My dear, Victor is quite capable of taking care of himself, and after all"—she looked at the tall girl beside her with a sparkle of mischief in her eyes—"why should you worry?"

Stephanie coloured at the implication, rather than at the actual words. "If he does not come back—he provided for me for the year, and no more," she answered.

"And—Stephanie, dear—is that all?"

But Stephanie looked steadily at the would-be-match-maker, her own self-possession fully regained. "He and I made a bargain—that is all," she answered. "Your interpretation of the bargain has been very generous, Bob—"

Bob put up a hand to silence her. "Don't you worry—Victor will be back in time," she prophesied, confidently. "If he's not, we'll find a way over the interval for you, my dear."

By the next mail came a letter for Bob, from Colombo. "A word to you lest I may not get another chance to write," Marshall wrote her. "I get lost here, in case cousin Pierre should be awaiting my arrival at Sapelung. Probably you will hear no more of me for months, but make no inquiries, either of the shipping company or anybody else, and in case Stephanie should be worried by my probable silence, show her this." Here he came to the end of a sheet of paper; Bob turned to the next. "I have a very lively interest in that young lady, Bob, quite apart from her cash value in the event of her step-brother's death. Keep an eye on her—as your brother, I need say no more. And you need not show her this."

Bob handed both sheets on to Stephanie and watched her read them.

"'Cash value,'" Stephanie quoted, caustically, as she handed the letter back to Bob.

"Apart from it, dear, he says," Bob answered, sweetly.

"Bob," Stephanie asked, with a suddenness that had something of fear in it, "do you think he will come back? I've told you about the others—three men who tried and were never heard of again. Do you think he will be heard of again?"

Bob looked at her and smiled; Stephanie was good to look on, and Bob could well understand that her brother, with all his apparent cynicism with regard to women, might be interested in such a one—more than interested, given the opportunity for seeing her as she was now.

* * * * *

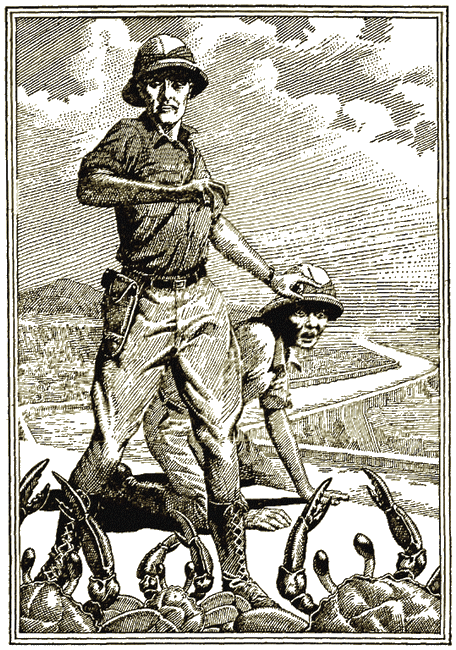

WHERE the track that had been nearly a road in character degenerated to a mere rough path, on the way to the cut in the hills, Marshall turned aside to the shade of a big bush and announced that they would lunch. Henry Aloysius Walker, dripping with perspiration, gave silent concurrence by stepping into the shade, where he dropped his pack like a man exhausted, and crumpled down beside it to mop his face with a rag of a handkerchief that was already soaked.

Marshall regarded his henchman a trifle anxiously. Henry Aloysius had been so anxious to make the trip, had pleaded so earnestly and put forward his qualifications so desperately, that almost against his better judgment and in spite of Mackeller's warning Marshall had engaged him. Now, in drill jacket and shorts, with stout, serviceable boots, a hunting shirt under his jacket and a wonderful wide brimmed felt hat on his shaven head, he looked like collapsing on the first march.

"Tired?" Marshall asked him.

"Not verree, sir," said Henry, trying to look perky and unconcerned. "I am not in condition, as yet. When we have covered some few miles, my natural robustiousness will assert itself—wow!"

The final exclamation was due to the acute penetration of some large black ants—Henry had been sitting on the exit from their underground abode. He gave them the right of way, hastily, and chose another spot with more care.

"Quite right—never argue with ants," Marshall remarked, with complacency—the way in which Henry had jumped proved that there was a good deal of robustiousness in him yet. "Now you can unpack all your belongings for a kit inspection while I get the grub out. I want to see exactly what you're carrying to make you drip so much."

Henry stared, while Marshall set about unwrapping the food Mrs Martinez had packed according to his directions; he stopped his task in response to the stare. "Well, what about that kit inspection?"

"Sir," said Henry, humbly but firmly, "much of my property is intimate and personal."

"And therefore not to be desecrated by the gaze of the vulgar," Marshall said. "Henry, my boy, remember the first duty of a good scout. Much of your property is obviously weighty—kit inspection, please."

Henry trembled with a great resolve. "I must respectfully decline, sir," he replied, with a sort of timid defiance.

Marshall unwrapped a sandwich and began to munch. "Better have something to eat before you start on your way back, Henry," he observed kindly. "It's downhill, I know, but you'll be hungry before you get back to the roaring traffic of Sapelung."

Henry gazed at his master until the invitation had fully sunk in. Then, with tears in his eyes, he began to unfasten his knapsack.

"Have some grub first," Marshall advised. "Plenty of time for that later. But there's one thing for you to remember, my young friend. As long as our ways lie together there is one will—mine. If I make a mistake I take the blame, and as long as you save me the trouble of turning a request into an order we shall be quite a friendly little party. When you think you know better than I do, it is time to kiss me once on the brows and part—you for Sapelung, and Mah-Eng for me."

Henry listened patiently, and a trifle doubtfully. Then he took a sandwich, bit twice, and reached for another. "Sir, I will obey in future," he said with his mouth very full.