RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"Accessory After," Ward Lock & Co., London, 1934

"IT should be easy enough," Inspector Head said to himself, as he set out to follow the trail of the old boots from the doorway of Westingborough Grange.

"But it isn't," he observed some twenty minutes later.

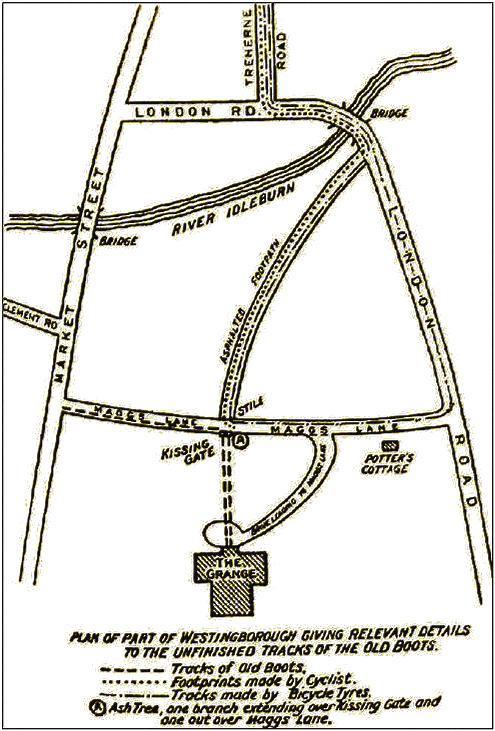

At the start, the trail was obscured to some extent by the marks of car-wheels and other footprints, both of men and women, for the late Mr. Edward Ensor Carter, as owner and occupant of the Grange, had given a party the preceding evening, and his guests had made a confusion of tracks round the doorway when they left, somewhere between one and two in the morning. But, since the trail of the old boots was superimposed on these others, both in approaching the house and leaving it, the muddle round the door gave Inspector Head very little trouble. He sorted out the track he wanted from all the rest, and followed it, slot-hound-wise, across a lawn, through an opening in the laurel hedge, and thence across the three hundred yards or more of meadow-land which divided the Grange garden from the road. As boundary between meadow and road, there was a seven-foot brick wall, topped with broken glass set in cement, but this precaution against trespassers was negatived by a break in the wall where what is usually known as a kissing-gate gave access to the road: Carter had had the break made and the gate put up when he bought the place from its previous owner, who had been a misanthropic hermit lamenting the passing of spring guns and man-traps.

Between the gate and the house was no regularly made path, but a sort of depression in the grass showed that the way was often used. Even at this present time, with an inch and more of snow veiling the earth, the trodden track showed, and along it went the prints of the old boots in two sets, one toward the house, and one returning away from it. And there was, Head noted, a slightly inebriated vacillation about those tracks: sometimes the toes of the boots pointed straight along the path; sometimes they inclined inward to an extent that might have indicated a broncho-buster as the wearer, and then again they would turn away from each other nearly to an angle of forty-five degrees each. There was no consistency about them.

Since the wearer of the boots had got away for the time—only for the time, Head felt convinced—a slow and thorough investigation was preferable to haste. Before he passed beyond the laurel hedge at the far side of the lawn from the house, he signalled to the man who had acted as chauffeur for himself and his party, a uniformed constable in a peaked cap who still sat at the wheel of the big police car. When the man got down to cross the lawn, Head gestured him to go round outside the laurel hedge, and then gestured a halt when he had his man within hearing distance. There was thus no muddle of tracks across the lawn, nothing beyond the two sets of prints made by the old boots, and Head's own marks, well away to the right of the others.

"See that nobody walks across this lawn, Jeffries," Head ordered, "and tell Williams—no, though—tell Sergeant Wells to go along the drive, out by the main entrance, and along to the kissing-gate, but not to obscure any footprints between the gate and the road."

"Very good, sir," said Jeffries.

"And tell him to stop anybody from coming through that kissing-gate, or even coming near it from the road," Head added.

"Right, sir."

"That's all, thanks."

He stood to watch while his man called the sergeant and transmitted the order, waited till he saw Wells set out from the doorway of the house. He appeared, then, as a kindly looking man, probably in the late forties, with greying hair showing from under his soft felt hat, and no indication of his calling either in his bearing or in his well-cut lounge-suit and overcoat. Long, dark lashes gave his brown eyes a rather sleepy expression, and his easy, deliberate habit of movement gave no hint of the almost abnormal physical strength and alertness he could bring into use at need. A certain cat-burglar, with whom he had coped single-handed successfully, had described him as a blinkin' thunderstorm disguised as a sofa cushion: the simile had been intended to define his physical prowess, but it fitted his mentality equally well.

Now, before turning again toward the gap in the laurel hedge, he counted both sets of footprints made by the old boots, and found that in crossing the lawn toward the edge of the drive—that is, toward the house—there were forty-three prints: returning, the wearer had covered the distance in forty steps, a natural discrepancy in view of the fact that he went to his task carefully and trepidantly, and hastened, taking longer strides, on the return journey. Then Head, who had kept well away to the right of the tracks, counted his own footsteps from the edge of the drive to this point, and found the total thirty-seven.

But, he knew, he had not been walking normally; he had been looking at those footprints all the time, and might have taken either longer or shorter strides than usual. He passed through the gap, taking care to leave the two footprints there quite clear, and, stepping off to the right again, walked steadily toward the kissing-gate, counting the footprints leading away from the lawn as he went, and ascertaining that there were two hundred and thirty-three separate prints. Then, as Wells had not yet arrived at his post at the gate, Head went back, treading in the prints he had made, and found that he had taken two hundred and fifteen steps for the distance.

Thus the difference between his length of pace and that of the wearer of the boots was fairly consistent: since he was six feet in height, and took thirty-seven steps to that other's forty, what was the height of the wearer of those boots? He trod in his own footprints yet again on his way back to the gate, where Wells was awaiting him now, and realised that he had no practical data for the solution of this problem. Some men of five feet nine took as long paces as his: length of leg in relation to that of the body counted for much, habit and exercise—or the lack of it—for more. But he was safe in assuming that the wearer of the boots was shorter than himself.

So he came to the gate, and there gave vent to his second conclusion regarding the two sets of footprints.

"What isn't, sir?" Wells inquired gravely.

"Stop where you are," the inspector bade. "Just so, out there on the road, you'll see that somebody wearing boots a tramp might have discarded stepped from where you are up to this gate, passed through, and went to the Grange, all since the snow fell last night. Also you can see the tracks of those same boots returning as far as the gate—my side of it, that is—and there they stop. Did he hook up on a passing aeroplane? I refuse to believe that the man who murdered Mr. Carter like that was an angel."

"Well, I'm damned!" Wells remarked wonderingly.

"Sorry to hear it," Head retorted, looking over the railings beside the gate. "Don't come any nearer—don't tread on that snow, whatever you do! Wells, hustle back to the car while I stay here and keep people off, and bring back the camera. I want photographs of this, at once."

The sergeant set off on his errand, and Head, leaning on the railings, took stock of his surroundings. There was a big ash tree growing just inside the wall, and from it a horizontal or nearly horizontal branch stretched out over the kissing-gate, but the most agile of men could not have caught hold of the branch by leaping up at it, since it was a good fourteen feet above the ground. And, even if one had caught at it and lifted himself up, he would have had to come to ground again and display footsteps within sight of where Head stood. A slack-wire walker would have found it almost impossible to keep foothold on the cement-bedded broken glass that topped the wall, which was angled, roof-wise, and not flat. Leaning over the railings, Head could see that the footprints were not continued anywhere within the circumference of the tree, and there was no other near it to afford a continuance of aerial progress. No, the footprints away from the house came just to the gate, and there ended. On their way toward the house, they came in from the road—from where Wells had been standing—and by the turn there showed that the walker had come from Westingborough. And, Head knew, within half a mile of this spot he would lose them: milkmen and other early workers would have trodden them out of existence.

He knelt beside the last of the prints, heedless of wet knees or damage to his clothes. There were a right and left close together, as if the wearer of the boots had come to a halt there, putting both feet together, and then had taken a leap into space. For there was absolutely no continuation of the track, and the maker of it could not have leaped over the gate and cleared the twelve or fourteen feet (later, Head ascertained that the distance was fourteen feet six inches) of untrodden snow to the nearest tyre-mark in the road. And, had he done this, the print of a boot would have showed in the tyre-track, but Head had already seen when he looked over the railings that there was no such print, nor any sign of the boots having trodden there except in coming toward the gate on the way to the house.

These two final prints, side by side, revealed the boots as of the heavy kind worn by agricultural labourers and the like, but worn to a point that would cause any self-respecting labourer to discard them. The heels had been iron-shod, but half the metal of the right heel had either worn or broken away altogether: the print of the nail that had held it to the leather showed clearly in the snow, while two-thirds of the hob-nails that had protected the sole were missing, and the leather forming the sole had completely worn through in the middle and toward the outer edge. It was a boot that would let in water, a boot that a tramp would hardly wear in such weather as this.

The left boot was in little better case. Its heel-iron had survived whole, but was evidently worn thin on its outer edge, and there were not more than half a dozen hob-nails left in the sole. Studying this print as he knelt, Head deduced that the sole itself had come partly unstitched, and probably flapped as the wearer walked. This might account for the irregular way in which the wearer had placed his feet—and again might not.

Finishing his inspection, Head rose to his feet again and dusted the snow off his knees. He looked at his watch, and saw that it was just half-past seven; the sky was leaden, and there was a threat of more snow or perhaps rain in the clammy air, and, since the snow already fallen was softening, it was urgently necessary to complete his knowledge of these tracks as quickly as possible. He looked up at the ash tree, and at a sudden thought stripped off his coat, removed his hat, and, hanging both on the railings before him, bent and then leaped with all the strength he had in an effort to grasp the lateral branch extending over his head. He missed it by a good two feet.

"Not that way," he told himself, and donned hat and coat again.

Wells came along the road with the camera, and halted, waiting for directions as to how to use it.

"A general photograph from there, first," Head bade, "Take two shots for certainty, and mind your exposure is long enough. Then come along and take a close-up of each print between the road and the gate and get another close-up of this pair inside. I wonder—could we get a cast, by any means?"

Wells shook his head. "Not in snow, sir," he said. "It'd ball on to the plaster, or clay, or whatever we might use."

"Well, then, make your photographs tell the tale. Meanwhile, I'm going up this tree. That chap hadn't got wings."

Leaving his man to take the photographs, he removed his hat again and swarmed up the trunk of the ash, to the grave detriment of his overcoat until he could get a grip on the lowest branch, when he lifted himself to a foothold and stood to observe what evidence the tree might provide. And, at what he saw, he save a little "Ah-h!" of satisfaction, and then, as he looked down at the road, cursed.

The snow, adhering to the upper sides of the leafless branches, had been rubbed off the bough running out almost horizontally and parallel with the railings on either side of the gate. Similarly, it had been rubbed off, another bough extending out over the road, showing that the wearer of the boots had by some means drawn himself up from where the final pair of footprints showed, and had lowered himself into the road from the other, rather higher bough.

But, Head concluded then, he must have had a car waiting, or something of the kind. For there was no footprint anywhere in the road corresponding to the tracks made by the old boots along the path—no sign of any kind that the wearer of the boots had descended to the road. And, assuming that he had been absent a mere half-hour or less on his errand of death, a standing car would have made impressions altogether different from those made by moving wheels. Had he by any chance an accomplice, who had driven slowly along the road to permit of his dropping into a car from the tree?

However that might be—Head put the problem aside for future consideration—he had not dropped on his feet from the tree, evidently. Nowhere within range of a jump or a descent by rope was there any trace of the old boots, and it was in the last degree unlikely that a murderer, unless he were altogether careless of his own safety, would leave an unattended car in the middle of a public road while he went to commit his crime. Four sets of wheel-tracks had been made here since the snow had fallen, and all were in the middle of the road: moreover, Head knew enough to account for all four sets, for those four cars had conveyed Carter's guests to the Grange the evening before, while there was no snow on the road, and had returned this way after the snow had fallen. Which went to prove that the wearer of the old boots had not continued his journey from this point by car—unless some one of Carter's guests had been an accomplice in the crime.

"That's the last of the second roll of film, sir," Wells said from the ground. "Twelve snaps, altogether. Will that do?"

"It'll have to do," Head answered rather irritably. "I've found out—he swung himself up into this tree with a rope. There's the mark of it out along this branch, where he slung it over."

"Pretty clever, slinging it over in pitch dark," Wells observed.

"We are not dealing with a fool, by a long way," Head said.

"But if he got up there, sir, he had to come down again."

"By the evidence of the boots, he didn't," the inspector retorted. "No, he spread his wings and flapped away, without touching ground. And who the devil's been along there, on that footpath? Two of 'em, by the look of it. No—don't go. I'm coming down to see."

He swung himself down from the tree on the inner side of the wall, and went through the gateway on to the road, still taking care to obliterate none of the footprints, though he knew that a record of them was in the camera that Wells had closed and put away in his overcoat pocket.

"I make 'em tens, sir," Wells observed. "My foot fits perfectly for length, and I take tens. He's a bit wider, though."

Head nodded acknowledgment of the statement, and surveyed the road thoughtfully. Then he looked up at the ash branch extending out over the road, and shook his head as he turned to his sergeant again.

"There must be an explanation," he remarked.

"I expect you'll hit on it, sir," the sergeant ventured.

"Problem." He stated it with a note of irritation in his voice. "X—we'll call him X, for convenience—X walks from Westingborough, presumably, or at least comes from the direction of Westingborough, goes into the Grange grounds by way of this gate, and walks up to the house, after this snow had finished falling. That is, after one o'clock this morning. At the house he commits his murder, presumably again, and then walks back as far as this gate. By means of a rope slung over a bough—I've seen the marks of the rope up there—he hoists himself up into the tree, and according to the visible evidence he doesn't come down again. Ergo, he must still be up that tree—and he isn't."

"Along the top of the wall, sir?" Wells suggested.

"The snow on it is undisturbed far beyond the reach of the tree in both directions—undisturbed as far as I can see," Head asserted. The sergeant gazed anxiously up the road and down the road, in quest of more than the one set of tracks approaching the gate: had there been another corresponding set going away from the gate, he must have seen it, for apart from wheel-tracks the snow was undisturbed. He pointed at the stile giving access to a footpath, almost opposite the kissing-gate, and leading past Westingborough churchyard into the town.

"There's two lots of footmarks, and a bicycle," he remarked. "If they have anything to do with it—but that man's set is smaller boots, and I know who it is, too. Potter, the man that works at Parham's garage, lives up in his cottage just past the Grange, and he's due at work at half-past six every morning. That's his feet."

"We'll put Potter down for an inquisition," Head decided. "He may be able to tell us something. The other set—it's a woman's, probably with brogue shoes, by the wide, flat heels. She got off her bicycle just here"—he was standing, as he spoke, almost in the tyre-marks on the side of the road farthest from the kissing-gate—"and wheeled it up to the stile and lifted it over. Then, by the look of it, she wheeled it along the path without mounting again—which she would do, since there was snow on the asphalt and it was still dark. Potter's tracks are superimposed on hers. Here's where she stepped down off the bike and began to wheel it, and she dumped it down well to the right of the stile to give herself room to get over. Then she—yes, Potter's left us enough to see what she did. Just got over and wheeled the bike along the path. I don't see—" He broke off to cogitate.

"What she's got to do with a man wearing a pair of tens a tramp wouldn't look at," Wells suggested thoughtfully.

"M'yes. Look here, Wells, I'm going back to the house, now, and you stop here and keep everyone off those wheel-marks and footprints round the stile—don't let them be obliterated or damaged. Take measurements of that woman's feet—if it was a woman. It might have been a small-built man, for all we know. And keep it all as clear as you can. I'm going to send you another roll of film, and you can take me half a dozen good exposures of those feet- and tyre-tracks, and get one of where she or he dropped down off the bike and began to wheel it to the stile, and the rest on the path there. One good general one showing the feet beside the tyre-tracks as she wheeled the bike—if it happened to be a she, and the rest I leave to you. Get the average length of pace over thirty or forty yards, and then go through this gate and take another average of the length of pace in the old boots. Don't worry about Potter's tracks. We can check him up easily enough."

"Right you are, sir. You think the woman—?" Wells paused.

"Possibility of accessory before or after," Head pointed out. "It was a clever devil who threw the rope over that branch in the dark, without making a miss and leaving the mark of it in the snow anywhere, or making any extra footprints over it. It was a clever business altogether, and done by somebody more than usually resourceful, because X couldn't calculate beforehand on snow falling last night. That murder was calculated exactly to time, planned out to the last detail, and we're up against brains, good brains. I'm not what you'd call happy about this case, yet."

Wells shook his head gravely. "It may turn out quite simple, sir," he observed hopefully. "'Ullo! Do I stop him?"

"You do not. But mind where you step out of his way."

A big, six-wheeler lorry, laden with milk-cans, bore down on them, going toward Westingborough. Head looked down at its tracks after it had passed, and then gazed toward the Grange gateway, the direction from which the lorry had reached this point.

"He did us all the damage he could do, before he reached here," Head remarked, "and if X went that way, those wheels won't have wiped out all his tracks. I'll walk back round by the drive and send you that roll of film as soon as I get to the car. Don't let anyone mess up those footprints and tyre-marks by the stile there."

THE front door of the Grange stood open as Head approached it from the drive, and the pendent electric light switched on inside showed him Constable Williams standing on guard over the place where the body of the murdered man had been found, a matter of three or four paces inside the doorway. But, as Head entered, he saw that the body itself had been removed: Williams was mounting guard over the two clear impressions of the old boots that the inspector had tracked through the snow, a right and left as clear as photographs on the polished parquet. The mysterious X had left other prints as well, but these two, as X had stood beside the spot where the body had been found, were the best, and evidently Superintendent Wadden had thought it worth while to preserve them. Head, entering, gave the constable a questioning look.

"In there, sir," Williams said, pointing to the doorway on the left of the entrance hall. "All of 'em."

Head directed him to send Jeffries with another roll of film to the sergeant by the kissing-gate, and entered the room indicated. It was a long, low-ceiled apartment, with no less than three windows giving on to the front of the house. On a long heavy highly polished mahogany dining-table in the middle of the room still remained nine empty champagne bottles, one empty decanter and another less than a quarter filled with whisky, several empty syphons, and a dozen or more glasses and tumblers. A still, sheeted figure lay on the floor between the table and the window nearest the door. The three living occupants of the room, two seated and one standing, looked round at Head as he entered.

The nearer of the two seated figures, that of Superintendent Wadden, was almost too fleshy for comfort; his neck lay in rolls over his tightly hooked uniform collar, and his fierce grey eyes under bushy brows gave him an aggressive appearance totally at variance with his real character, for a kinder man never put on a uniform. Beyond him Bennett, the doctor who had examined the body, looked rather disconsolate: the room was chilly, and the littered table gave it a depressing look; also Bennett, having finished his work, wanted to get away.

"I've been holding everything up till you got back, Head," Wadden said. "Jones"—he turned to the constable in attendance—"go and see if they've got a paraffin stove or something—this room's like the North Pole. Y'see, Head, I'm due to retire the beginning of May, and just in case this business isn't finished by then, I want you to be conversant with all of it. So we've just fetched the body in here—what have you got since you went out?"

"A man climbed a tree, and apparently flew away," Head answered composedly. "That is, I can't see that he came down again."

Wadden took a pair of handcuffs from his pocket and held them out. "Take these and put them on him," he suggested. "If he didn't come down, he must be still up there."

"That's my trouble," Head said. "He isn't."

"It's your case," Wadden said. "I'm too old to climb trees. D'you want to go through that part of it first?"

Head gestured a negative. "I'll go over it with you later. Wells is on the spot, finishing off taking the photographs I want. What have you at this end? I see you've brought the body in."

"Ye-es, the doctor's finished with it. We deduce he was shot from the doorway the first time, and that bullet went clean through him just under the shoulder and fixed the time of the murder. Then he fell on the floor, and the shooter came and stood beside him, put the pistol down on to his right eye, and pulled the trigger a second time. The eye is completely obliterated, you'll see."

Head went to the still figure on the floor and turned down the sheet from the face. It was that of a middle-aged man, almost white-haired; the sickening appearance of the eye-socket robbed it of all normal expression, and Head drew the sheet back and turned to the superintendent again as Jones entered, carrying a lighted paraffin stove.

"That's better," Wadden said. "Put it down here, between me and the doctor. Questions, Head?"

"What did you mean when you said the first shot fixed the time?" Head inquired, after a thoughtful pause.

"It went clean through, and ended up in a clock on the mantelshelf at the back of the hall, stopping the clock at two minutes Past four," Wadden answered. "That is, if the clock was going. I've questioned nobody, waited for you to come back."

"Which means it was done with an automatic pistol," Head pointed out. "A revolver wouldn't have put enough force behind the bullet."

"We'll go through the arms register and check up on it," Wadden promised. "There can't be many of either, in Westingborough district."

"Somebody must have heard the shooting," Head suggested.

"There are four servants and a chauffeur," Wadden observed. "Jones, fetch in Arabella Cann—she's the one who found the body, Head."

They waited, and presently the constable escorted into the room a stout, middle-aged, frightened-looking woman. Wadden nodded at her, and gestured her to seat herself in the chair that Jones drew forward.

"Sit down, Miss Cann," he said, "and we promise not to eat you. We just want to know all you can tell us about this business."

"Only just—I found the master, sir," she said shakily. "And telephoned the police station at once. I don't know any more."

"Oh, yes, you do," Wadden said encouragingly, "but you don't know you do know it. Let's go back a bit, as far as the party last night. What was it—dinner, or just a social razzle?"

"We had six to dinner, sir," she answered. "Five and the master, that is, and the others came in about half-past ten—"

"Just a moment," Wadden interrupted. "Who were the five?"

"Well, sir, there was Mr. and Mrs. Quade, Mr. Pollen and his young lady, Miss Hurder, and that young Mr. Denham."

"Yes. They came to dinner. Now who came after dinner?"

"Miss Perry—the one that gives dancing-lessons, and her sister Miss Ethel Perry. Mr. Frank Mortimer fetched them in his car."

"And took them back?" Wadden suggested.

She shook her head. "I don't know, sir. The master rang for me about midnight and told me we could all go to bed after I'd brought in some more soda syphons. I asked if he'd want Adams—that's the chauffeur—and he said no, he could go to bed too. They'd look after theirselves, he said, and we wasn't to stay up."

"And did all five of you go to bed?"

"As far as I know, sir. I know we all went up-stairs."

"Will that be up to the floor above this?"

"No, sir, the next one—the top floor of all. We all sleep up there. Adams was glad to go because Minnie—that's his wife—she's poorly. She'd gone up about half-past nine."

"Minnie is the cook, I understand?"

"Yes, sir."

"Now, Miss Cann, you know there's a clock on the shelf at the back of the entrance hall. Does it keep good time?"

"Very good time, sir. It's always within a minute or two."

"Was it keeping its usual good time last night?"

"It was just right, sir, when I heard the wireless signal from the drawin'-room and looked at it."

"You wind it every night, I expect?"

"No, sir. It's an eight-dayer, and I wound it Saturday night as usual, and to-day's only Tuesday."

"Made for us, Head," Wadden observed, looking at his inspector. "Carter was shot the first time almost precisely at two minutes past four this morning. How does that fit your examination, doctor?"

"I placed death as between three-thirty and four-thirty," Bennett answered. "Do you want me any more before the inquest?"

"No. I'll ring you and give you the time for that. To-day."

"Then I'll leave you to it." He rose and went out.

"Well, Miss Cann," Wadden pursued thoughtfully, "didn't you do anything at all when you heard the shots? Mr. Carter was shot at four o'clock, and it was five-forty when your telephone call came through."

"I didn't think it was shots, sir," she explained. "You see, sir, Mr. Denham's got one of these sports cars, and it goes bang just like a gun. It did when he started away, and I got up and went to my window to look then. I heard a lot of laughing round the front door, and heard the master say Mr. Denham—Dennie, he called him—mustn't point that car at anyone. So when I heard two more bangs downstairs I thought it was Mr. Denham come back for something, and didn't take any more notice."

"And all the others thought the same, I suppose?"

"Minnie—that's Mrs. Adams—she said she did, and didn't take any more notice than I did. The others say they didn't hear anything."

"Two floors up—no. Well, Miss Cann, how did all you get on with Mr. Carter? Was he a good sort of master in the house?"

"Well, sir, he never bothered us or took much notice of us as long as we got our work done. Never took much notice of me, I mean."

"I see," Head said, slowly and thoughtfully. "What is your position here, Miss Cann? What do you call yourself—housemaid?"

"Head housemaid, sir. Hetty is the second, and Phyllis is the parlourmaid. Then there's Minnie I've told you about, the cook."

"Any questions, Head?" Wadden shot out the query after a brief silence, looking up at the inspector.

"Not now. Possibly at the inquest," Head answered.

"Then we won't trouble you any more, Miss Cann," Wadden said, "unless by any chance you could produce a spot of hot coffee. And you might tell Phyllis—Miss Taylor, that is—that I'd like a word with her if she'd be so good as to step in here."

"I think there'll be some coffee ready now, sir."

"Excellent! Just ask Miss Taylor to come in for a word with us."

Jones ushered her out, and presently ushered in the parlourmaid, to whom both Wadden and Head devoted appraising glances. She was not in uniform, but wore a dark grey silk blouse and black skirt, both very well cut, while in the matter of shoes and stockings she was above criticism. There were marks of tears on her cheeks, and her pretty, piquant face showed deathly pale where the rouge failed to cover—she had made up hastily and none too well that morning. As she entered and caught sight of the sheeted figure under the window she reeled and appeared about to fall, and Head took her arm and led her to the chair that Arabella had vacated. Wadden gave her time to recover composure.

"Miss Taylor, I think?" he asked at last.

She nodded a silent assent, and crumpled a handkerchief even more tightly in her hand. Wadden nodded gravely, sympathetically.

"I suppose you were on duty here last night, Miss Taylor?" he inquired. "Waiting on Mr. Carter and his guests, I mean?"

"Ye-yes." She nodded again, and choked back a sob.

"How long have you been in service here?" he pursued.

"Four—four months. Since September."

"Do you belong in this district—have you lived here long?"

"I—I came from London," she answered shakily.

"Engaged there by Mr. Carter—is that so?"

Again she nodded, and gave no verbal reply this time.

"What salary was Mr. Carter paying you?"

"Si-sixty pounds a year." She looked slightly surprised at the question, though she answered it readily enough.

"Umm-m! Where were you in service before you came here?"

Again her expression registered surprise. "Nowhere," she replied.

"This was your first place, you mean?"

"First time in service," she assented.

"I see. And what were you doing before then?"

"I was—I was in the chorus at the Quadrarian—in revue."

"Miss Taylor, did you hear those shots fired when Mr. Carter was killed, at four o'clock this morning?" He leaned toward her and put the question with a sort of tense abruptness.

She shook her head. "I was asleep," she answered.

"Have you a room to yourself?"

"Yes."

"The first one at the top of the stairs, isn't it?"

She gave him a frightened look, and Head, standing a little behind her, nodded silent approval of his chief's astuteness.

"Yes, but on the top floor," she answered.

"What time did you go to bed?" Wadden pursued.

"About one o'clock, I think."

"In your own room, and alone?"

"Yes. Of course I was in my own room, and of course I was alone!"

"There isn't any 'of course' about it, Miss Taylor," Wadden said gravely. "I want to tell you, anything you say here and now stays inside these four walls, but if I have to instruct for questioning you at the inquest to-day, it may be a very different matter. I'm not accusing you of any connection with Mr. Carter's death, but I want to know all I can, to help me in finding who killed him, and though the things I ask you may seem silly, they've all got a reason behind them. Parlourmaids with no experience don't get sixty pounds a year round here, as you know very well. Now we'll carry on. You saw as much of Mr. Carter as anyone in this house, didn't you, and more?"

"I suppose I did," she admitted.

"What was the time when you last saw him alive?"

"About half-past eleven last night," she answered.

"You neither saw nor heard any more of him after that?"

"I—no." But she hesitated a little too long on the negative.

"Ah! Not good enough. What was the time when he came to your room at the top of the stairs, Miss Taylor? Don't lie about it, or I may floor you from another source. Be careful, now—what time was it?"

"He—he knocked at my door after everyone had gone," she admitted in a low voice, gazing down toward the floor.

"And you got up and let him in?"

"I didn't!" She looked up at him again. "I told him to go to hell."

"By the look of it, he's—never mind, though. How often did he come up to your room after everyone else had gone to bed?"

"Not often, lately." Again she looked down toward the floor.

"Was this the first time you'd refused to let him in?"

She tried to look at him, and failed. "Yes," she whispered. "And now—Oh, he's dead! He's dead!"

She forced herself back to composure as Arabella entered with three cups of coffee on a tray. Each of the men took a cup, and by the time Wadden had sipped his and put the cup down Phyllis was composed again.

"Why wouldn't you let him in last night?" Wadden demanded quietly.

"He—he'd been carrying on in the drawing-room with that Miss Perry, the fair one—Ethel, her name is. I caught 'em at it when I went in. I didn't want him coming to me, after that."

"A pretty business—oh, a pretty business!" Wadden mused aloud. "Now I want to know, Miss Taylor, do you know any reason why Mr. Carter should be down at the front door at four in the morning? Somebody might have rung the bell, of course, or thrown a stone at his window, but do you know of anything or anyone he'd go down for?"

"Yes, I do," she answered, more readily. "Him and me was in the drawing-room yesterday afternoon—I'd taken tea in to him, and the 'phone went. I stopped in when he answered it, and he said—'Four o'clock—yes. I'll come down myself, since you want to be so secret.' It was either 'secret' or 'secrecy' he said. I think it was 'secrecy,' though. I know he said he'd come down himself."

"At four o'clock in the morning?"

"No, just four o'clock. I thought he meant come down to Westingborough at four next day, or something—it didn't strike me till you asked just now that he meant come down to the front door. Of course, that was it! He meant come down to be killed, at four this morning."

"He didn't know he meant that," Wadden suggested. "Could you hear the voice in the telephone—hear what it was like?"

"Only the sort of mumble you always hear. Just a noise."

"Was it a squeaky noise, or a rumbling one?"

"Just a mumble. It wasn't squeaky, and it wasn't a rumble. Just an ordinary little noise, so you couldn't tell in the least who was talking or what they said, not even if it was a man or a woman."

"What time was this?"

"Eddie—Mr. Carter always had his tea at half-past four if he was in, and this was just after I took it in."

"Immediately after? I mean, you hadn't been billing and cooing before the telephone bell went and he answered it?"

"There's been precious little billing and cooing for me the last two months," she answered bitterly. "I'd made up my mind to go if things didn't alter, and I hadn't any hope they would."

"D'you get on well with the other servants?" Wadden inquired, with an appearance of kindly solicitude over the point.

"No, I don't! I hate the lot of them."

"Well, Miss Taylor, you've given us some very valuable information, and that bit about the telephone call will have to come in at the inquest, but I see no need to disclose your intimacy with the deceased man, for the present. Thanks very much, I won't keep you any longer. Head, d'you think we can find out anything about that telephone call?"

"I'll see what can be done," Head assured him.

"Ah-h!" He yawned widely. "We all knew what he was, of course, but that doesn't alter the fact that it's a dirty murder. Now there's the other housemaid, Hetty Fraser, and Adams and his wife Minnie to be seen, though it's my opinion we won't get another thing out of any one of them. Then we can get down to your side of it, this chap who climbed a tree and flew away. Jones, push that chauffeur bloke in here to us, and tell the gentle Arabella that coffee of hers is so good I'd like some more, if she's got any handy."

He looked up at Head as the constable went out.

"I've got it in my bones—and that's a long way down—that you won't get to the end of this case either to-day or to-morrow, Head," he remarked. "You'll have to use your wits if you don't want to find yourself up a tree."

"I've been up one already this morning," Head answered ruefully. "Look at my overcoat!"

RAIN had begun to fall steadily when Superintendent Wadden and Inspector Head seated themselves in the back of the big car after instructing Constable Williams to remain in charge at the Grange, until Sergeant Wells could be sent to relieve him. Wadden lowered himself into his corner with a grunt; Jones was already seated beside the man Jeffries, who was at the steering-wheel.

"Now what d'ye make of it?" Wadden inquired, as Jeffries turned the car about to go along the drive to the road.

"Nothing, yet," Head answered, "except that X, the man in the old boots, committed the murder. Puzzle, find X."

"Let's see what we've got," Wadden suggested. "State it, man."

"In sequence, eh? Not a bad idea," Head concurred. "Well, then, four months ago Carter took a fancy to this girl Taylor while he was in London, and fetched her down here ostensibly as parlourmaid. The other servants didn't like the arrangement, but they like their jobs too well to make a fuss, and at sixty pounds a year she wasn't a mere parlourmaid, while the clothes she was wearing this morning prove sixty wasn't all she was getting. Lately, Carter was getting a bit tired of her, and had rather a crush on this Ethel Perry—and we know already he was that sort of man, eh? How's that for groundwork, chief?"

"Go ahead—but the Taylor girl had nothing to do with the shooting. She didn't hate him enough for that, yet."

"That's obvious. Yesterday afternoon, she took in his tea to the drawing-room, and overheard his end of a telephone conversation, in which he arranged to come down to the door at four o'clock this morning to interview X—it was X put that call through, for a certainty. And we want a far more detailed account of that telephone conversation—Carter's end of it, at least, from the girl Taylor."

"I know. I left that for the inquest. She'll have got her wits more about her by this afternoon, and from what I make of her she's regretful enough over his death to help us find out who killed him. We already know that he made the appointment to come to the door himself, for secrecy, and that she hasn't any idea who it was calling up. Go on—Wells can wait. We'll stop here while you finish."

"Next, then," Head pursued, "Carter had that dinner-party and the razzle after it. I've been over the guests in my mind already. The Quades—we can practically rule them out. Quade is a racehorse trainer, I know, and a harmless sort. Young Pollen wouldn't hurt a fly, and he's lived in Westingborough all his life, and Betty Hurder would travel miles to get a smell at a champagne cork, and sing for her supper too—any old song that was asked of her. Denham—I don't see him at all in that galley. He's a lot better than the type Carter generally had round him. The Perry girls are much more in Carter's line, and Frank Mortimer is the darkest horse of the eight people Carter had at the Grange last night. But it appears from what the cook said that the party didn't finish till just past three, so any one of the eight would have had to hustle to get into those boots and come back and do the shooting at two minutes past four."

"You can go round the lot of them to tell them they'll be wanted at the inquest—give the summonses yourself," Wadden suggested.

"If I fix it for three this afternoon, can you do the lot?"

"Easily, I should think," Head assented.

Jeffries had drawn the car to a standstill in the road about twenty yards short of where Sergeant Wells waited by the kissing-gate. Wadden made no move toward getting out, yet. "Go on," he urged.

"Me, sir?" Jeffries asked from the driving-seat.

"No. You sit here, and listen to the rest of this story, if you like. We'll get out when I'm ready. Carry on, Head."

"Some time between three and four, just after the party had left, most probably, Carter went up to the girl Taylor's room. I think he wanted to persuade her that he was only fooling with Ethel Perry, and she was still the light of his eyes, but however that may have been she wouldn't let him in. You see, he had to keep awake till four o'clock, since he was due to go to the front door himself and open it, and it would be well past three when he knocked at Taylor's door. And at that time, or a little later, X in the boots must have begun moving. He came along this road from Westingborough, went through that gate, and up to the Grange. Carter opened the front door to him, and he fired two shots, as we know, the first of them at about two minutes past four. Then he came back and climbed that ash tree by means of a rope slung over the branch, and he didn't come down again, but he isn't still up there. That is, he didn't come down to make any impression on the snow with those boots, and there's no other footprint near that corresponds remotely to the boots. All that's visible is a woman who cycled as far as the stile and wheeled her bicycle along the path after she'd lifted it over the stile, and the marks left by Alfred Potter on his way to Parham's garage—and he came later than the woman cyclist."

"And which way did X go?" Wadden inquired ironically.

"No way at all," Head asserted. "He climbed the tree, and the snow shows that he didn't come down—shows it far beyond the radius of the tree. And he didn't go along the top of the wall—I've made sure of that, while I was up the tree. No marks of any kind."

"Which is absurd," Wadden commented. "Good old Euclid! Let's see."

He got out from the car, and Head followed him. With an order to Jeffries to stay where he was, the two went to where Wells stood beside the road. Wadden looked up at the sky and shook his head.

"In a couple of hours all these tracks will be washed out," he observed. "You took photographs, I understand, Wells?"

"Eighteen altogether, sir," the sergeant answered.

"It should be a pretty complete record then. Yes, I see. He came from the top end of Market Street, and when you get to that road junction round the bend there's not a hope in Hades of trailing him further. Nevile's works are running two shifts this month, and the first lot goes in at five-thirty, which means that snow will be churned to mud a quarter-mile farther on. Potter—yes, that'll be his feet. Now the bicycle—yes, she dropped off here, if it was a she. It's doubtful, with those heels—might have been a small-built man. Wheeled the bike to the stile and lifted it over—yes. And Potter came along and planted his clumsy foot right over hers where she stood to lift the machine over. Walked it along the path—what's that other set coming and going, off to the left there?"

"Mine, sir," Wells explained. "Mr. Head told me to—"

"All right, sergeant. I want to see all I can before the rain distorts the prints too much. Now through the gate—yes. Both going to the Grange and coming back, and the coming back ones stop just as you said, Head. Swung himself into the tree, eh?"

"I found the mark of the rope on that branch over the gate," Head answered. "From there, he shifted the rope to the branch sticking out over the road, as if he meant to lower himself down by it from there. But you can see for yourself the boots don't come down there."

"Dropped into a car, then."

"If so, it was one of the four cars from Carter's place, only those four had left tracks in the snow when I got here,"

"Why didn't they leave tracks going to the house?"

"Because there wasn't any snow before midnight."

"Kick me, Head. Never mind, though. Have you made any cast round to pick up the prints of those boots?"

"Not yet. When I was up in that tree, I could see clean snow for a good two hundred yards in every direction, and apart from what we have here there wasn't a print on it. Nothing at all. You see, this Maggs Lane isn't overmuch used—there's only the Grange and Potter's cottage beyond it, and then you get Market Street and its continuation that way, and behind us, the other side of the Grange, the main Westingborough-London road."

"That cyclist. What's she or he doing here between midnight and four o'clock—or five o'clock, or whatever time it was?"

"We've got to find out," Head answered. "Evidently she came off the London Road—I traced her wheelmarks as far as the Grange gateway—and dismounted here to take the path and rejoin the road just before you get to the river bridge—Gosh! Chief, she's in it!"

"Why?" Wadden asked interestedly.

"Else why should she cycle down this lane from the main road, lift her bicycle over the stile, and walk along the path with it only to rejoin the road she'd left just before you get to the bridge? It's a good road for cycling, all the way, and by coming round this way and walking the path she puts a quarter of an hour on to her journey."

Wadden shook his head. "Maybe," he said, "and maybe not. Don't jump to conclusions, Head. Are you going to suggest that X dropped out of the tree on to her bike? If so, what happened to him and his feet when she lifted the bike over the stile? I'll grant she might have piggy-backed him along the path, and might have climbed over the stile with him on her back while he held the bike, but if that had been so she wouldn't have left this one even track. Look at it, man—as plain as print, though the footsteps are going a bit saggy in the rain. He'd have had to drop down on her shoulders, retrieve his rope, and sit tight while she wheeled the bike to the stile. Then one or other of them would have had to lift it over, and she'd have had to climb the stile with him on her shoulders and make that walk along the path. And that steady, regular set of footprints brings Euclid in again—it's absurd. Accessory in some way, perhaps, but not accessory after in that way. It would be far too damned conspicuous, for one thing."

Head went to the stile and gazed down at the footprints in the soggy snow. They retained enough character to tell their tale.

"You're right," he said disappointedly as he returned. "It wasn't done that way. But he went, somehow. Wells, did you get those measurements of the two sets of paces?"

"Yes, sir. The old boots average twenty-nine inches going to the Grange, and twenty-nine and a half coming back to the gate here. I took both averages over eighty paces. The feet beside the bicycle average just on twenty-eight inches over another eighty paces along that path. I'd just finished working the three sets out when you came along in the car. There's been nobody along here since the lorry."

"How far have you been along the path?"

"All the way, sir, up to where it goes out to the road between the white posts. It's a consistent track all the way."

"Right. Now hand me that camera and the films, and you go back to the Grange and take over there for the present. Tell Williams to report back at the station. Chief, we've got to find that cyclist."

"Also, a man who climbed up a tree and flew away," Wadden retorted dryly. "Well, I've seen all I want here. We'll get back, I think."

THEY went back to the car. At Wadden's instruction, Jeffries drove very slowly past the kissing-gate and along the lane to the point where it emerged to Market Street, and all the way they saw the prints of the old boots on their left, showing how the mysterious X had come along the lane, but no sign of his returning. Wadden gazed out, registering each footprint in his mind, but after a hundred yards or so Head appeared to lose interest, and sat deep in thought. Jeffries turned then into the churned slush and wakened activity of Market Street, and there put on speed until he slowed again to draw up outside the police station, where all three of his passengers descended.

"I'm coming in," Head announced. "It's too early to go round after Carter's guests, yet, and I've got an idea."

He retired to his own room, where he took a large sheet of paper and set to work on it with his fountain-pen. A quarter of an hour or less passed, and then he entered the superintendent's office. Wadden had had breakfast sent in there to save time, and Head laid his sheet of paper down beside his chief's plate on the flat-topped desk "How's that?" he asked. "Do you agree?"

Wadden took a drink of coffee, and then read—

Police Notice

To All Cyclists

Any cyclist who passed along Maggs Lane from London Road to the path leading from Westingborough Grange grounds to the Idleburn bridge, and went along the path toward the bridge, between midnight of January 19th and 6 AM. of January 20th, is requested to communicate at once with Superintendent Wadden at Westingborough police station. Also any person who may have seen a cyclist in the vicinity of Maggs Lane or of the path between the above hours is requested to inform the police at once.

"Umm-m!" Wadden commented. "Might be worded better. D'you think it's going to fetch your cyclist here?"

"I don't," Head answered decidedly. "It's going to prove that cyclist accessory to the murder by showing that he or she is afraid to come forward. We can have it posted all over the town by noon, and it's pretty evident that the cyclist who came round by that path in the dark knows Westingborough well—is no stranger to the district. Whoever it is will see the notice, and if we get no response that person is either accessory or even the murderer himself."

"Accessory, yes," Wadden said thoughtfully, "but the footprints and the tree branches put the other out of our possibilities, I think. Here, you'd better have some breakfast, man. You'll think better on a full tummy, and this is no five-minute job. It's a pity about this rain, but you'd got pretty much all you could out of those footprints."

"We'll have the films developed," Head said. "Wells can be trusted for a complete record. It doesn't matter if the tracks are washed out, now. Yes, I do feel rather like eating, now you speak of it."

"HEAD! Head! Come back here, out of that car!"

Head, about to set out on a round of interviews with all who had been guests at the Grange the preceding evening, descended to the pavement again in response to the superintendent's agitated summons.

"What's happened now, chief?" he inquired.

"I haven't got apoplexy hurrying out to catch you, but that's not your fault," Wadden answered. "Come inside with me. I rather think we've got what used to be called a clue."

Head followed to the superintendent's office, and saw, standing by the desk, a young constable in uniform. Wadden blew out his lips and gave the man one of his fiercest looks, and then sat down.

"Story, Borrow," he commanded. "Tell Inspector Head what you saw, and make it a witness-box report. He's in a hurry."

"Very good, sir. At three A.M. to-day, sir"—he turned to address his report to the inspector—"I passed Parham's garage in Market Street as I patrolled my beat, and turned to go along London Road, toward the bridge. It would be five minutes later, or seven minutes at the most, when a woman on a bicycle passed me, coming from the direction of the bridge. She was in nurse's uniform. That is, sir, she had on one of those long capes nurses wear, and a little bonnet with strings. I saw that much clearly as she cycled under a street lamp, but she was on the far side of the street from me, and kept looking at the pavement on her side of the street, so I didn't see her face. She appeared tall, something between five feet eight and five feet ten, and as nearly as the cloak or cape would let me see, I should say she was slim too. I didn't take particular notice of her, knowing that nurses are out all hours, but I looked back after she'd passed me, and saw she'd turned into Treherne Road. The bicycle was fitted with an electric lamp—and that's all I can tell you about her, sir."

"You didn't see her till she was over the bridge—on your side of it, that is?" Head queried.

"No, sir. I'd stopped a lorry soon after turning into London Road to make the driver relight his off-side lamp—he was fitted with oil-lamps, and it had gone out. I looked back when I heard him start his engine again, and when I looked in front of me again, here comes this nurse on her bicycle. It would be between five and ten minutes past three, then—certainly not more than ten minutes past."

"Carry on, man," Wadden bade. "This isn't all, Head."

"I went on over the bridge, sir," the constable proceeded, "and saw the track of a bicycle coming out from the path that leads across a field to Westingborough Grange—"

"And footprints beside the bicycle track on the path?" Head interrupted questioningly, "Did you see them?"

The man looked puzzled. "I couldn't say, sir. I didn't look along the path. It was pitch-dark then, and what little light there was from the nearest street lamp only showed me the wheel tracks close to the side of the road—there's no pavement beyond the bridge, you know, sir. I just thought to myself—that's the way that nurse has come, and turned about to come back over the bridge."

"You didn't notice any footprints, then?" Head persisted.

"No, sir, but they may have been there all the same. I'm not sure."

"I am, though," Head said, with a note almost of exultation.

"Sure of what?" Wadden asked sharply.

"Never mind, chief, for the minute. It's a theory, no more, and it needs testing, but down in my mind I feel sure I've got this clear. Is that all you have to report, Borrow?"

"No, sir, not quite. I'd gone back along Market Street and up Clement Road, and turned back to come into Market Street again. I could see Parham's clock, and the time was three thirty-five. I could just see a young man on the far side of Market Street from me, coming from the direction of London Road—"

"That is, going toward Maggs Lane—the end of it," Wadden interjected. "The way the old boots went, in fact."

"How could you see it was a young man?" Head asked the constable.

"He passed under a street lamp before I lost sight of him, sir," Borrow answered. "He was dressed in riding-breeches and either gaiters or knee-boots, and carried something under his arm, something that made him draw his hand up and keep the arm close to his side. Under his left arm, and I was on his right as I saw him, so I don't know what it was he was carrying."

"It was a pair of boots, size ten, and possibly a coil of rope as well," Head said with conviction. "Go on, though. What was he like?"

"Not very tall—five feet eight or nine, I'd say. He was walking quickly and keeping to the shadows all he could, I thought. Looked a gentleman, as nearly as I could tell—didn't carry himself like a groom or stable hand. What made me think of that was that I'd seen Mr. Quade, the racehorse trainer, driving the opposite way before I turned into Clement Road. This man was rather like Mr. Quade in build, thin and active, and light-footed, and he was hurrying for some reason. He had no overcoat on, only what looked to me like a double-breasted jacket, and a cap, not a hat. When I got to the junction of Clement Road and Market Street again, he was out of sight."

Head thought it over. "Is that all?" he asked at last.

"That's all, sir. When Jeffries told me about the murder at the Grange I thought I ought to report this to Mr. Wadden at once."

"Quite right, Borrow. Are the nurse and the young man the only two people you saw on your beat between three and four o'clock?"

"They are, sir, except for the lorry driver and his mate."

"Chief"—Head turned to Wadden—"has that notice I drafted gone for printing yet, do you know?"

"I sent it off while you were wolfing sausages," Wadden answered.

"Well, they'll send a proof. If you wouldn't mind adding 'And Nurses' to the second line in heavy type, and after 'Any cyclist' in the text add 'or lady in nurse's uniform with bicycle,' it'll make our check still more complete, especially if she doesn't come forward."

"And put her still more on her guard," Wadden pointed out.

"Not more," Head dissented. "The people concerned in that murder are very fully on their guard already. No fingerprint on the Grange door-handle or anywhere else, though the murderer must have closed the door after the shooting, since there was nobody else to close it—we start this without a single clue of the conventional kind, apart from those footprints, and the rain's washed them out by now. If she's innocent, she'll come forward. If she doesn't, we know we've two people to find, and that may be easier than finding one."

"Probably will be," Wadden assented. "I'll alter the notice to fit a lady cyclist in a nurse's cloak and hat, anyhow. Or do they call it a bonnet? I must get that from the hospital before I alter the proof. Strings under the chin, Borrow?"

"Yes, sir, as nearly as I could see. She kept her face turned away from me, though, and the street lamps don't give much light."

"And you didn't look for footprints beside the tyre marks?" Head inquired, returning to the point again.

"No, sir. You see, I should have had to focus my belt lamp, and for what looked like a nurse coming back from some job it didn't appear worth while. I'd no idea there'd been a murder, sir."

"Neither had we, then," Wadden remarked. "Well, Head, I thought you ought to have this under your thatch before you start your round. Meanwhile I'll have every nurse in Westingborough investigated, and find if there's one of any sort living in or near Treherne Road. Leave all that to me. And get on to Carter's past life as soon as you can. There's some old grudge behind a planned job like this."

"I hope to come back with a history of him," Head said.

"Old boots, nurses on bicycles, young men in riding-breeks, and a chap who flies up out of trees and doesn't come down—Gee-whiz!" Wadden soliloquised, and blew gustily ceilingward. "Head, it's a packet, and no bloomin' error! Off you go, man. Borrow, I don't want you any longer. Keep on the way you're going, and you'll be a credit to us yet, but be a bit more nosey, man. No matter whom you see out between one and five in the morning, conclude they're up to no good, and act accordingly—in a quiet way, of course. There'll be a whole series of promotions on my retirement, and your name might get in among the recommendations somehow or other. I'm keeping an eye on you."

"Thank you, sir."

"That's the first time I've ever been thanked for keeping an eye on anyone. Now you go off duty and remember what I've told you."

He took up a sheaf of reports that had been lying on his desk, in token of dismissal, and blew at them as if he hated them.

IN place of the steady rain of early morning, a chill drizzle caused Head to set his windscreen-wiper to work when he set out on his round of visits, not in the big car in which he and Wadden had gone to Westingborough Grange, but in a fast little coupé which he drove himself, and used for visits to village stations in the district. He went out, first, to Quade's training establishment, which was situated on the far side of Westingborough from the Grange.

He saw four stable lads walking rugged and bonneted horses round a yard as he descended from the car, and Quade himself, gaitered and horsey-looking, turned from watching them in the gateway of the yard as Head approached him. Borrow's description of the young man he had seen as resembling this man recurred to the inspector's mind. He nodded a casual greeting: Quade was the hail-fellow-well-met sort with whom such a form of salutation would pass.

"'Morning, inspector. Come to see whether my crocks exceed the speed limit? I forgot, though—there isn't one, now."

"Good morning, Mr. Quade. No, I've come to warn you to attend the inquest on Mr. Carter at Westingborough Grange at three o'clock this afternoon. He was shot dead there at four o'clock this morning."

"Good God! Inspector, you're joking!"

If he had had any doubt regarding Quade's innocence, this reception of the news would have dispelled it: but he had had no doubt.

"I'm not," he said. "Carter has been murdered."

"At four o'clock? Why, we only left the place at three—about three, that is. My wife and I, I mean."

"I know. That's why you may be wanted for evidence. I don't know that you will, but both you and Mrs. Quade must attend. Shall I see her and tell her, or may I rely on you?"

"I'll—Oh, rely on me by all means! I'll tell her. Three o'clock, at the Grange. But who—who did it? Have you got him yet?"

The inspector shook his head. "You may hear something at the inquest," he said evasively. "And you left at three or thereabouts. Were you the last of the party to leave?"

"No. We all went pretty much together—I drove off first with my wife, and the rest followed us. At least, I believe they all did. I know Hugh Denham was just behind me coming along Maggs Lane."

"Alone in his car?"

"Yes. He'd left his hood down, and had to shake and wipe the snow off the driving-seat before he started up—it hadn't started snowing when we got there for dinner."

"And after," Head suggested, "nobody thought to see if it were snowing—or anything else, for that matter."

"Well, to tell the truth, inspector, I shouldn't have taken my wife there if I'd known it was going to be that sort of a party. Not that she didn't enjoy herself, but—still you say he's dead, and I'd better not say any more about that. I can't believe—" He broke off.

"On the other hand," Head said gently, "the more you say, the more help you may give. We've got to get his murderer, you know."

"You mean—yes, I see. Well, I'd only met him in the hunting field, till then—he followed the Westingborough, you know—and rode like a sack on a barrel, if I may say so much of a dead man. He invited my wife and me last week, and told me Hugh Denham would be there. It was that made us accept. I thought Denham—well, you know, it was a sort of warranty. Mrs. Quade thought so, at least. It was a good dinner, with the bubbly flowing free, but everything quite all right. I thought Fred Pollen had quite as much as was good for him, and that Miss Hurder made one or two remarks I wouldn't care to hear from my wife, but it was pleasant on the whole. Then, after dinner, that Mr. Mortimer do you know him, though?"

"I've seen him," Head assented. "Never spoken to him, though."

"Well, he came in with the Perry girls. Carter ordered out another case of champagne—another case!—and said something about making a night of it. By that time I was—well, a bit elated, if you like to call it that, and Mrs. Quade was quite safe with Mr. Denham, I knew, so—well, there we were. I thought of leaving about midnight, but couldn't find Carter. He'd strayed off and got lost with the younger Miss Perry somewhere, and she looked rather rumpled when they came back. By that time I'd forgotten about wanting to go. Somebody had set a gramophone going, one of the sort that changes its own records, and we were dancing out in the big entrance-hall—it's parquet, you know, and they rolled the rugs out of the way. And none of us left till three. It all broke up suddenly, then—I thought Carter wanted to get rid of us."

"Did you hear him say anything about an appointment for the morning—for any time in the morning?" Head asked.

Quade shook his head. "No—I hardly spoke to him after dinner, till we said good-bye to come away. He was too busy with Ethel Perry for any of us to get many words with him."

"Quite a cheerful party, eh?" Head suggested.

"Very nearly what the Yanks call a petting party," Quade responded. "There was Carter carrying on with Ethel Perry, and going off with her away from the rest of his guests, and I saw Miss Hurder sitting on young Pollen's knee after a dance, and Mortimer and the other Miss Perry tried out some steps as they called it, but it wasn't the sort of dancing you expect to see off the stage—or on it either, in this country. As a matter of fact, I got my hair pulled when we got home."

"Mrs. Quade didn't enjoy it, I gather?" Head inquired sympathetically. "That is, she didn't quite approve?"

"You've said it!" Quade assented, with earnest gravity.

"And you all left at about three?"

"Somewhere about then, as nearly as I can tell. As I said, Denham followed us in that open Bugatti of his—and it sounded like a machine gun out of order when he started up. Mortimer had his coat on, and the two Perry girls had got into their wraps, and I saw Pollen hand Miss Hurder into his car as we were leaving. About three o'clock."

"Ah! Thanks for all you've told me, Mr. Quade. Don't forget, three this afternoon at the Grange. I must get along, now."

He drove back into Westingborough, and drew up at a block of business offices at the corner of Market Street and London Road. On the first floor he found a door which carried a brass plate stating that "Hugh Denham, F.R.I.B.A.," occupied that particular office. A lean, elderly clerk took his name, and ushered him into a comfortably furnished inner office in response to his request to see Mr. Denham.

A tall, well-set-up man in the early thirties turned from a drawing-board at Head's entry, inquiry in his clear grey eyes.

"What have I been doing, inspector?" he asked. "And what can I do for you? Do sit down, won't you?" He indicated a chair.

Head took no heed of the invitation. "I want you to tell me what's wrong with the exhaust of your sports Bugatti, Mr. Denham," he opened.

"Ah! Forty shillings and costs for having an improperly silenced exhaust, eh? Well, if it's got to be, it's got to be. But I assure you it will be all right after to-day. I dropped some water on the exhaust manifold while it was nearly red hot and cracked it, but Parham himself told me this morning that the new manifold he put on order has arrived, and he's putting it on for me to-day. So I throw myself on the mercy of the court. Do sit down and have a cigarette."

He offered his case. Head accepted a cigarette and a light, and seated himself. Denham leaned against the stand that held his drawing-board, and in turn lighted up.

"Meanwhile, you've been making a noise like pistol-shots," Head affirmed with thoughtful gravity.

"Guilty, and I know it's an offence. But I have to use the car." He smiled pleasantly. "Can't you let me off?"

"If it hadn't been for that noise, Mr. Denham," Head said, without smiling, "we might be nearer than we are to catching the man who murdered Mr. Carter at four o'clock this morning."

"WHAT?" Denham almost jumped, and dropped his cigarette.

"The shots that killed Carter were mistaken for the explosions from your exhaust by the servants who heard them," Head pursued unmovedly, "so they made no attempt at finding out who fired the shots."

"Do you mean to say Carter's dead?" Denham gasped.

"Quite dead," Head assured him. "Shot, at four this morning."

"But—but I was up at the Grange last night!" Denham pointed out. "I didn't leave there till the early hours of the morning. I—inspector, you haven't come here because you think—" He paused, almost fearfully, staring at the seated man before him.

"If it were that," Head said, "I shouldn't be here alone, and you'd have had handcuffs on before now. No. You left the Grange at about three o'clock, and Carter was murdered at four—never mind that, for the present, though. Mr. and Mrs. Quade drove off first, and you followed them. Were you alone in your car?"

"Yes—except for a packet of snow, that is. I'd left the hood down when I went there—to the Grange—and had to clean some of the snow out before I got in myself."

"Did you put the hood up before you left?"

"No—it wasn't snowing, then. The car was open. I drove it to Parham's this morning for the new manifold, and told them to clean it out and dry it as well. I had to sit on my folded overcoat."

"You know the kissing-gate in the wall, opposite the path leading to the Idleburn bridge—in Maggs Lane, I mean?"

"Yes. What about it, though?"

"When you passed that gate, did you see anything or anybody?"

"Nobody and nothing," Denham assured him. "Not a sign. Why?"

"Did you slow up there at all?"

Denham shook his head. "No. I was just behind the Quades' car, and another—Pollen's I think it was—was close behind me. We all left at about the same time. But about Carter being murdered—"

"You'll hear all about that at the inquest at the Grange at three o'clock this afternoon," Head interrupted. "I'm here to warn you to attend the inquest. What sort of party was it last night?"

Denham hesitated. Then he looked his questioner squarely in the eyes, and shook his head gravely.

"I didn't want to go," he said. "But I don't know if you know that Carter employed me as architect for the new wing he gave to the Westingborough hospital. He made a point of my accepting this invitation. He's been trying to get in with Westingborough people ever since he took the Grange. And it needed only that party to prove that he'd never get in, if he tried for a thousand years."

"Like that was it?" Head inquired interestedly.

"The man's an utter bounder—God forgive me! You've just told me he's dead. I ought not to have said that."

"Mr. Denham, I want you to say everything you can, to help me in laying hands on the man who murdered him."

"Have you any idea who it might be?" Denham asked.

Head did not answer at once. He was utterly certain of the innocence of the man before him. What he wanted to say, he reflected, would in all probability be said at the inquest, and Denham might be able to help in some way if he said it now.

"I think," he answered at last, "it was a young man of about five feet eight to ten—not as tall as you, you realise—who passed along Market Street not long after you left the Grange this morning. He was dressed in riding-kit, and carried a pair of boots and a rope under his arm, and he walked from outside this office, I think, to where Maggs Lane comes into Market Street just outside the town."

In turn Denham was silent, gazing down at the floor.

"Why from outside this office?" he asked at last.

"By, that, I mean that he walked along Market Street," Head answered. "I don't particularise this office any more than, say, Parham's garage, or the Duke of York Hotel. He walked along Market Street at about half-past three, or a little later, on his way to the Grange."

Denham turned away and went to the window of his room, where he stood looking out for some seconds. His manner, Head noted, had completely changed. Abruptly he turned back toward his seated visitor.

"What can I tell you, inspector?" he asked.

"Did you see that young man, or anyone else, as you drove back from the Grange this morning?" Head demanded quietly.

"Except for a policeman here in Market Street and the Quades in the car ahead of me, I didn't see a living soul as I drove," Denham answered, with utter, patent sincerity.

Head thought over the reply. It was truthful, obviously, but he scented a reservation in it somewhere. But further questions on the point, he felt, would only put Denham on his guard: they might be put at the inquest, where the man would be on oath—he was the type that would heed the sanctity of a promise to tell the whole truth.

"So you didn't think much of the party?" he suggested.

"I—well! Quade got squiffy"—Denham appeared to answer more easily now—"and poor little Mrs. Quade almost turned to me for protection—not from her husband, but from the general rowdiness. And—yes, amorousness. Pollen and Betty Hurder cuddling openly, and that man Mortimer with Lilian Perry—there was dancing on the parquet out in the entrance-hall, and—I felt it served me right for accepting the invitation. Think me a prig if you like, though I've no objection to a general frolic, but it all seemed to me like a bad night-club being unusually suggestive—immorally suggestive, if you understand."

"Oh, I understand," Head agreed, "and we've had you up for speeding in the Bugatti, and know it was you put the pyjama-jacket on the statue in the square on New Year's night. A pretty lively prig, altogether. And you say Pollen was close behind you, driving home?"

"Up to the end of Maggs Lane. He turned left, there, and I turned right to follow the Quades along Market Street. He lives along to the left there, and the Hurders live next door to him, you know."

"Yes, I know." Head rose to his feet. "I'll go and warn him for the inquest. Three o'clock at the Grange this afternoon, Mr. Denham. You can take this as the official notification that you are to attend."

"I'll be there," Denham promised. "It seems impossible to realise this, though. Only an hour after I left him—"

Driving out to the Pollens' house, on the outskirts of the town, Head reflected over this last interview. Denham had kept back something: he had, Head felt almost certain, recognised or thought he recognised somebody in that description of the young man in riding-kit, and meant to keep whatever knowledge he possessed to himself. It might be possible to make him reveal something at the inquest, though.

A clean-living, high-spirited youngster, a general favourite in the town, well-connected, and doing well in his profession, he was neither murderer nor accomplice, Head felt certain. And, going over all the men whom Denham might know, the inspector could think of nobody in the least like that young man in riding-kit, with something under his arm, out at half-past three of a wintry morning.

There were not so many young men in Westingborough of the class and type with which Hugh Denham associated that they could not be placed. Yet Denham's change of manner, his momentary unease, pointed to some knowledge.

Head braked the car to a standstill outside the Pollens' gate, got out, and went along the path to the double-fronted, rather pretentious-looking house with its stucco-pillared portico. It marked the type of people, he reflected, who would be willing to associate with such a man as Carter: probably young Pollen had been quite pleased with his invitation, and evidently he had enjoyed the party.

"Yes, Mr. Fred is in the study," the maid informed Head as she stood back for him to enter the house. "I'll tell him, if you'll wait."

He waited, amid a collection of pseudo-artistic trifles with which Fred's mother had seen fit to deck the tiny entrance-hall. Fred himself, son of a retired builder who had made much more money than he ought, out of erecting rabbit-hutches to house people of the working class, was supposed to be reading for the law. He was a terribly slow reader, having been at it now for more than four years. Head followed the maid to the study after a period of waiting, and found Fred Pollen standing before a good fire in his dressing-gown. An empty cup stood in its saucer on the table, and though Fred might have gone so far as to wash, he had neither shaved nor brushed his hair. He looked thoroughly unappetising, Head decided.

"'Mornin', inspector. Take a pew if you feel like it. What's up?"

"So you've not heard what happened this morning?" Head inquired.

"Just got up," Fred answered. "Have a heart, man. I've been having a bit of a thick night—spun it out a bit."

"And evidently reeled it home," the inspector retorted sourly. "I merely want to warn you to attend the inquest on Mr. Edward Carter, which will be held at the Grange at three o'clock this afternoon."

Fred reeled to the armchair beside the fireplace and slopped down in it. "Dead?" he gasped. "Carter dead?"

"Dead," Head confirmed, standing immobile by the table.

"But—but he was alive when I left there a few hours ago!"

"He's dead now," Head insisted. "I want to know, Mr. Pollen, when you drove away from the Grange, who was in the car in front of you?"

"The car in... why, let me see. That racehorse man—no, it wasn't, though. He went first, with that prim wife of his. No, he'd gone. It was an open car—I know! Denham in his Bugatti sports. But you say Carter is dead?"