RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

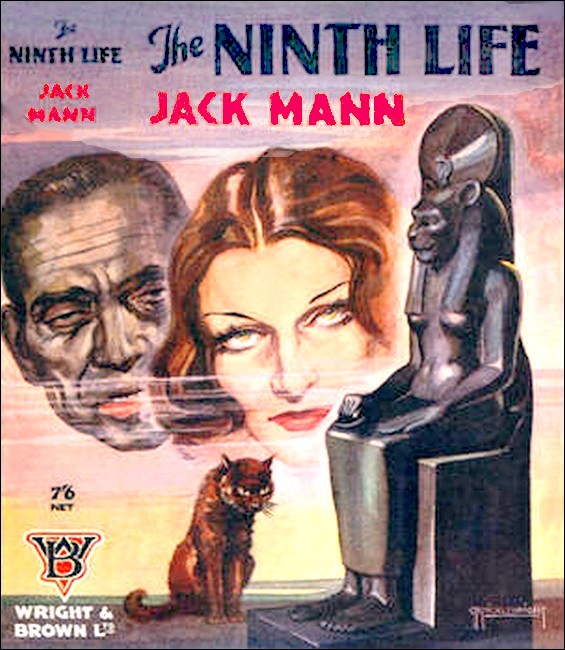

"The Ninth Life," Wright & Brown, London, 1939

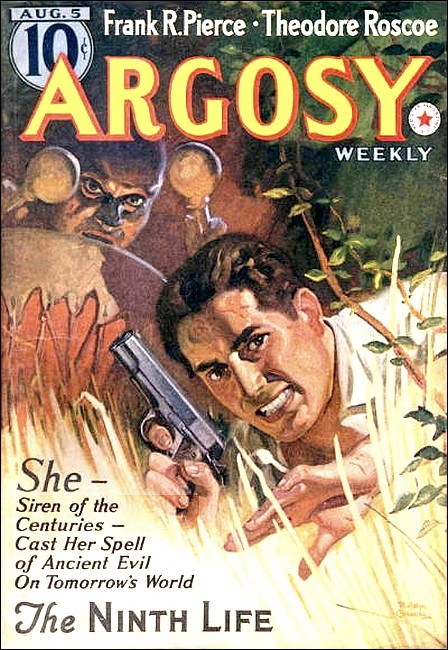

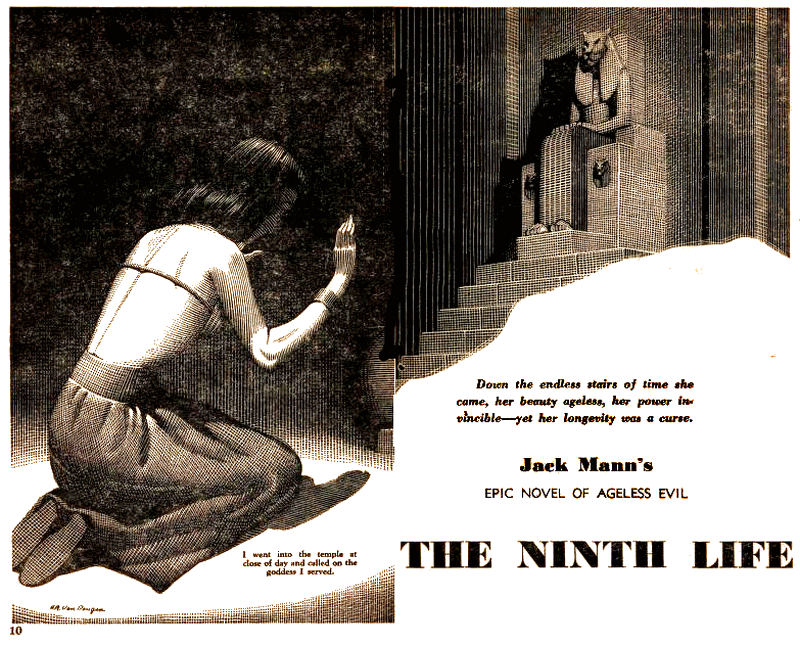

Argosy, 5 August 1939, with first part of "The Ninth Life"

A. Merritt's Fantasy Magazine, April 1950, with "The Ninth Life"

Down the endless stairs of time she came, her beauty ageless, her power invincible—yet her longevity was a curse.

Headpiece from A. Merritt's Fantasy Magazine.

ALTHOUGH more than two years had passed since Gregory George Gordon Green—known as "Gees" for obvious reasons—had established his confidential agency, he still gave himself an occasional mental pat on the back over his choice of a secretary. She was not only useful, but decorative too, a tall girl with blue eyes and brown hair with reddish lights in it, and a face attractive more through its expressiveness of eyes and lips than through regularity of feature.

She faced him, this mid-morning of January, from the doorway of his office, and dropped her bomb calmly enough. "Inspector Tott would like to see you, Mr. Green."

He took his well-shaped but unduly large hands from his pockets, and stared at her incredulously. "Tott?" he echoed. "All right, Miss Brandon," he said at last. "I'll see him."

Presently she ushered in a well-set-up, alert-looking man who might have been a stockbroker or a shopkeeper—but who actually was a trusted officer of the Special Branch of the C.I.D. For a few seconds the two men gazed at each other in silence. At the conclusion of Gees' last case, they had agreed to bury a certain hatchet, but their expressions indicated that part of the handle still stuck out.

"Come in, Inspector."

"Before I do, Mister Green—" the inspector laid a heavy emphasis on the Mister—"I'd like to be sure that microphone of yours is not working. Because I'm speaking unofficially."

"Whatever you say, Inspector," Gees assured him blandly, "will not be used as evidence against you."

"I wish we had you back in uniform again," Tott observed, rather wistfully.

Gees shook his head. "My fee for an initial consultation is two guineas. I wouldn't get that in uniform."

"I know what you'd get from me," Tott replied grimly.

"We both know," Gees assured him.

For a few seconds the inspector simply glared. "You remember that Kestwell case?" he asked eventually.

Gees nodded. "You wanted to arrest me."

"Yes—that's the point," Tott said. "You got Mr. Briggs to come along and prevent that arrest." Tott paused. "I believe they think a lot of Mr. Briggs at the Foreign Office." Again Tott paused. Finally, as if the words were torn from him, he blurted: "I suppose you've heard that Mr. Briggs has got engaged to be married?"

"I have, now. From you. Who is the lady? I must ring up Tony and congratulate him."

"It's because he's not to be congratulated that I'm sitting here," Tott said slowly. "You've heard of Lady Benderneck, I expect?"

"There is also a Buckingham Palace," Gees observed pensively.

"Yes, I thought you had. Well she sponsored this Miss Kefra—Cleo Kefra. Mr. Briggs met her and—well, lost his head over her. And the engagement was announced day before yesterday."

"The old hag would sponsor anything, at a price," Gees remarked. "Cleo Kefra. Sounds a bit exotic."

"Is, I assure you," Tott said, and made a grim comment. "Well, I've got a great respect for Mr. Briggs, and I've seen the lady," Tott told him. "I'd hate to see a gentleman like him trapped."

"What is wrong with Miss Kefra?" Gees asked.

Tott shook his head. "You'd better see her for yourself," he answered. "Mr. Briggs is a friend of yours, I know. There's nothing wrong with her—nothing that I can put a finger on, but—"

"Inspector, Briggs is pretty levelheaded, and I don't see any possibility of interfering, even if I felt like it."

"Well, I've got it off my chest," Tott said, and stood up.

Gees delayed him with a gesture. "Who is Cleo Kefra? The name isn't English, for a start."

"She looks Eastern to me," Tott said. "She's got a passport issued by the British consulate in Alexandria describing her as a British subject aged twenty-three; and apparently she's very wealthy. No relatives, as far as I can gather. Came to this country five months ago, and she's leased Barnby-under Hedlington Grange, furnished—that's in the Cotswolds. Also runs a swagger flat in Gravenor Mansions."

"It sounds as if Mr. Briggs is to be congratulated," Gees remarked.

"The flat is number thirteen," Tott added.

"My grandmother died of pneumonia," Gees said.

"What's that got to do with it?" Tott almost barked.

"As much as the number of the flat, I think," Gees told him. "Don't get peeved. I appreciate your interest, and I shall certainly make a point of seeing the lady as soon as I can. But what is your grievance against Miss Kefra?"

Tott shook his head. "I can't pin it down," he answered. He turned toward the door. "Thank you for listening to me," he added. "It's not—as I said—a matter over which I can do anything."

"Thank you for talking," Gees said. "I'm glad you feel like that about Mr. Briggs, Inspector, though I don't see—"

"No," Tott remarked in the pause. "But I must get along."

After closing the outer door, Gees went into his secretary's room, seated himself on the end of her desk, and produced the inevitable cigarette case. He said, "If Tott were a fool he wouldn't be where he is." The girl waited.

"And yet," he went on, "it's apparently possible for Tott, even, to acquire a wacky notion. About Briggs. Foreign Office. He's just got engaged. The girl it seems, exotic, slinky, and hails from Egypt. Also appears possessed of a healthy wad of dough. And Tott wants me to break the engagement since he can't do anything about it himself."

"But that's absurd," she said.

"Quite. Now I suggest we lunch at the Berkeley, Miss Brandon. I'll fix it for Tony to bring Cleo Kefra along. A woman's view of another woman is always worth having."

"So is a lunch at the Berkeley," she remarked. "But what name was that you called her?"

"Exactly, Miss Brandon—it hit me just like that. Cleo Kefra—something to do with the great pyramid, by the sound of it. Not an alias, either—she'd have chosen something less conspicuous."

Tony Briggs, over the phone, said he'd be delighted to bring his fiancée to lunch on Wednesday. No, he had not seen Tott recently—not for over a fortnight, in fact.

"And when is the wedding?" Gees inquired.

"Oh, we haven't got as far as that yet," Tony protested.

"Just as well. I'd better pass judgment first."

"Oho!" And Tony laughed. "I've no fear of anybody's judgment."

"Probably another Tony said that about another Cleopatra, old son," Gees observed.

He hung up, and went along to Miss Brandon's room again. She looked up from her typing at him. "It just occurred to me that history is doing another of its repetitions," he said.

"History—?"

"Anthony Briggs—and apparently Cleopatra Kefra," he explained.

"I thought of that some time ago," she said.

"Well, the other one threw the world away, but I expect chucking the Foreign Office will be this one's limit."

"Sacred mackerel!" Gees ejaculated, as he entered the Berkeley lounge on Wednesday with Miss Brandon. "The old man's getting gay."

The white-haired, soldierly-looking man, seated with another of his kind over two dry sherries, got on his feet and came toward them. There was enough facial likeness to declare the relationship between him and Gees—though his father was better looking and had neatly proportioned hands and feet, while Gees had large hands and very large feet.

"How d'you do, Miss Brandon?" he said courteously. "How are you, Gordon? Lunching here?"

"Meeting Tony Briggs and the girl he's going to marry, Father," Gees explained. "You know Tony, of course. Would you and—and that friend of yours care to join our party?"

General Sir George Green shook his head. "Thank you, Gordon, but—"

He broke off to stare toward the entrance, where Briggs and a tall, very slim girl were poised. "Gordon," he said, hurriedly, "I met that girl, exactly as she is now, when I was on my honeymoon in Egypt. A Miss Kefra."

"Mother to this one—no, though—it's the same name," Gees said. "An aunt—father's sister, probably. You'll be introduced?"

"Not now. No, I must get back to Farebrother."

With a slight bow he turned away—turned his back almost pointedly on Tony Briggs and his companion. Past question the girl's appearance had disconcerted him.

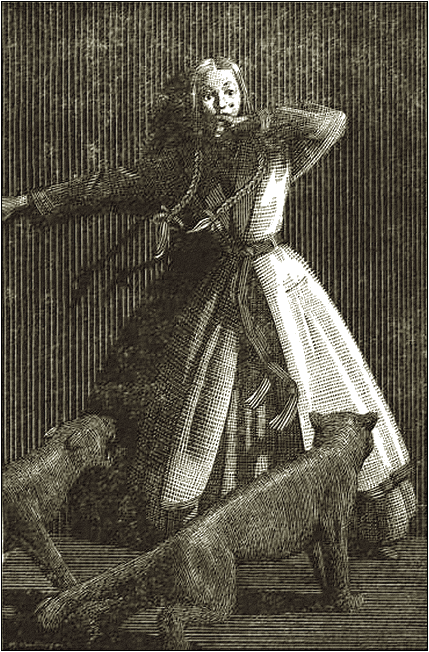

SHE was wearing a coat of undyed black panther fur, the five- group markings showing distinctly in its satiny gloss, and under it a closely fitted frock of shining gray, with a moonstone set in platinum pinned at her breast. Except for her fiancé's ring, she wore no other jewelry. A little black hat fitted closely to the red-brown of her hair, and under it her unusually pale face was perfect in feature.

Her eyes were amber flecked with green, and the pupils appeared almost abnormally small—yet they were very lovely eyes. She was bizarre, un-English—and queenly. Tott had said that her passport declared her as twenty-three, but in poise and dignity she appeared far beyond that age.

Unusually slender, she was sinuous, too; she flexed in movement to an unusual degree. His first thought as she neared them was that Tony had won a first prize out of life; his second that, before she spoke a word, he disliked the girl—or woman. Beside him Miss Brandon made an utter contrast, as of normality facing the almost-impossible he felt that he had never liked Miss Brandon quite so well, and trusted her so fully, as in this moment—and the green-flecked, amber eyes read all his thoughts and feelings, he realized, while their pupils dilated suddenly, rendering them darkly lustrous as she gazed at him.

"We're a trifle late, I'm afraid," Tony Briggs began. "Cleo, my two very good friends, Miss Brandon, and Mr. Green—"

The strange girl's hand, Gees realized as he held it for a moment, was very cold. She smiled at him, confidently—as might a duellist coming on guard. "I have been looking forward to meeting you, Mr. Green."

Perfect English, with no trace of accent. And a perfect voice, low-pitched, soft, and yet resonant. Her smile was the smile of—Gees faltered—of eternity.

AT the corner table, Gees faced Tony Briggs with Cleo Kefra on his right, and Miss Brandon facing her. Some dozen tables away, he could see his father and Colonel Farebrother, and noticed that the general kept staring at them, uneasily.

Cleo Kefra talked well, with the assurance of a woman of the world; Tony Briggs' gaze at her proved him hopelessly, fatuously in love—Gees felt rather grimly that he had never seen a worse case. Miss Brandon appeared divided between nervousness and amusement.

A mention of Egypt, toward the end of the meal, evoked from Gees the remark that he had never been there, and Cleo's dark eyebrows lifted in slight surprise.

"I gathered from Tony that you had been everywhere," she said.

"I was going to Egypt the year I joined the police force," he answered. "As it is, I haven't been there in this incarnation."

"Then you believe we live more than once?" she asked.

"An open mind," he answered, "is always useful."

"What do you do—your work, I mean," she asked. "Tony said something about an agency, but he was terribly vague about it."

"I've got a four-roomed flat within shouting distance of the Haymarket, and half of it is my office. I started by advertising that I'd tackle anything from mumps to murder."

"And how many cases of mumps have you attended?" she asked.

"I've had one murder—two murders, in fact," he said. "The others—the ones worth considering, that is—have been worse."

"Do go on," she begged. She spoke lightly enough, but Gees heard a challenge in her tone.

"Well," he said slowly, "there was a man who made shadows."

Her fine brows drew down. Then she smiled and nodded. Every movement, every gesture, was graceful.

"I know," she said. "I saw it once at a party, a man who made shadows of ducks and giraffes and all sort of things with his hands."

"Not that, Miss Kefra," he said. "I mean that old shadow magic—older than Egypt, even. Each shadow's a life."

"I—" She began, and stopped. Again he saw the pupils of her eyes dilate, and knew he had, as he had intended, roused fear in her. "You—what did you do?" she asked, after a pause in which the other two, silent and listening, sensed the tension.

"That man will make no more shadows," he said, rather grimly.

"How very thrilling!" She had recovered her composure, and even managed a laugh. Tony Briggs drew an audible breath of relief, and scowled fiercely at Gees, but said nothing.

"Mr. Green is very mysterious about that case," Miss Brandon observed. "It's the only one of which I don't know the end."

"How do you mean a man made shadows, Gees?" Tony fired out with abrupt harshness. "And each one a life?"

"He took lives to prolong his own," Gees said seriously. "It was old magic, the sort of thing nobody believes nowadays. No more credible than—well, someone told me today that he saw Miss Kefra exactly as she is now, thirty-five—no, thirty- eight years ago."

"Which is quite possible," Cleo said calmly.

"Quite—darling, what do you mean?" Tony demanded.

"Merely time-traveling," she explained. "The man's sight might have gone forward thirty-eight years, just as memory can go back to childhood—or even beyond, in some cases."

"This is much too deep for me," Tony remarked glumly. "I'd say the man saw somebody like you, except that there's nobody like you."

"Who is the man Mr. Green?" Cleo asked abruptly.

"It happens to be my father," Gees answered. "Thirty-eight years ago he was on his honeymoon in Egypt—so he tells me—and saw you just as you are now—with the same name, Miss Kefra. I told him an aunt, probably. It's a more likely explanation. People don't go time-traveling on their honeymoons. At least, I wouldn't."

She smiled once more, her perfect lips triangular.

"It appears that you and I are interested in the same subjects," he remarked. "Will you get Tony to bring you round to my place for tea some time?"

"Willingly," she assented. "I should very much like to hear more about this shadow magic you mentioned."

"The man who practiced it," he said, slowly and looking full into her strange lovely eyes, "was very old. There were many shadows."

"I don't understand." But Gees knew beyond any doubt that she did understand.

"I'm sorry to seem like breaking up the party," Tony cut in abruptly, "but being a wage-slave under the Government I ought to be back in time for tea. And if I'm to take you along first, Cleo—"

With Tony holding the door of a taxi outside, a little later, the girl gave Gees her hand and gazed full at him.

"I'm so glad we have met," she said. "Tony must bring you to see me, next time. For tea, one of his free afternoons."

"It will be a great pleasure," he assured her.

With Miss Brandon beside him, he watched the taxi go, and saw how its two occupants sat well apart from each other in their corners.

"We'll walk back, I think, Miss Brandon," he said.

"Just as you wish," she assented. "It's a beautiful afternoon."

"On second thoughts—" he lifted a crooked finger at a taxi-driver—"you take this and charge it to petty cash, while I run along to the British Museum for an hour or two."

She gave him an inquiring look as the taxi drew beside them.

"Never mind. I'm probably crazy. Both of us—Tott and I..."

THE winter dusk was well advanced when, returning to his flat in Little Oakfield Street, Gees let himself in and entered Miss Brandon's office. She looked up.

"You have been a long time," she said. "I have been thinking, since coming back here, Mr. Green. In over two years here, I have done about two months' real work," she explained. "You don't really need me—a girl in from an agency occasionally could take your dictation and—"

"You mean you want to give notice?" he interrupted incredulously.

"I might even go as far as that," she admitted, smiling.

He reached out to flick an ash into the tray beside her typewriter. "Finding it monotonous?" he suggested.

"Not that. But my being here like this, filling in time by reading novels, is not fair to you. This—your agency—is a one-brain enterprise."

"What about that lunch today?" he demanded abruptly, without hesitation.

"Well, what about it?" she echoed.

"I arranged it," he said slowly, "because of Tott's visit here—because of Tott's notion. And I had an idea, while I was groveling in the dust of the British Museum, that it might have struck you too. Instead, you brood over this preposterous idea of yours—it is preposterous, my girl! I've got used to your being here, a wall to throw my thoughts against and watch 'em bounce, and I'd hate to lose you."

"For one thing, Mr. Green," she retorted rather acidly, "I am not your girl. For another, the wall feels itself as the end of a cul-de-sac. The hours I waste here—waste!"

"Then to you," he asked, "that lunch was a mere social function?"

"Hardly," and she shrugged slightly. "It was most uncomfortable."

"Oh! Now we're getting somewhere! Carry on, Miss Brandon."

"That—that Miss Kefra was afraid of you."

"I meant her to be, on sight. What about Tony?"

"He won't be your friend much longer, if she has her way over it."

"No? Well, do you think I could get any girl from an agency that I could take to the Berkeley on a footing of equality, and count on the sense you showed with those two remarks? Moreover, I've been doing some thinking too. I'm going to make a case of this Miss Kefra, turn myself into a purely honorary and unsolicited nuisance as far as Tony Briggs is concerned—for his good, of course—and to drag you in and give you all the work you want."

"I don't understand, Mr. Green," she said, after a pause.

"No. I've got to explain. You know, of course, that I've dabbled a little in the occult."

"Then you consider Mr. Briggs—or Miss Kefra—an occult problem."

"When did it strike you that she was afraid of me?" he countered.

"When you talked about the shadow-maker," she answered, after a brief pause.

"Exactly. Miss Brandon, Cleo Kefra is a lamia of some sort—uncanny in some way," he said. "Tony Briggs is my friend, and I'd go a long way to keep him out of trouble. And that girl—woman, rather—spells trouble for him."

"She is—unusual," she conceded thoughtfully, "but what have you against her? What is there to justify interference?"

He stubbed out his cigarette, and lit another.

"I don't know. She hails from Egypt. She's paid old lady Benderneck to get her an entry into the circles Tony frequents, but she's—she's no background, really. At the best, an adventuress, and at the worst—but I want more than the mere impression I got at lunch before saying anything about that. Did you like her?"

She smiled. "We detested each other on sight," she answered.

"There you are! Intuition—on both sides."

"I don't understand any of it, yet," she said, "except that you seem determined to do exactly what you tell me Inspector Tott asked, merely because Mr. Briggs has—well, because he's in love with her rather than loves her. You see, I must discount my own dislike of her."

"Trying to be fair—yes, but—"

The telephone interrupted him. It was his father's voice he heard.

"Oh, it is you, Gordon? Can you dine with me tonight?"

"With all the pleasure in life, Father."

"Good. I'll expect you at seven-thirty."

"Thank you very much, Father. I'll be there."

He replaced the receiver, and nodded thoughtfully.

"May get a line on the lady," he said. "That was my father, asking me to dinner."

"And you think—yes—over his having met a relative of hers."

"I'm not so sure about that," he dissented slowly. "In fact, I'm not sure about anything. But I want you to do some scouting for me, round Gravenor Mansions. A little work for a change."

"Not to interview Miss Kefra?" she asked quickly, doubtfully.

"Far from it. No. Just nosing around. Maybe there's a caretaker with a thirsty wife, or a man on the lift who'd take you to the pictures in his off time—anything, as long as you find somebody with a waggly tongue. And then—anything at all about Miss Kefra. People who come to see her, the establishment she keeps, how she impresses the underlyings—but don't run the risk of meeting her. She's seen you once—had you sitting facing her, and those eyes of hers would look through anyone."

"When do you want me to go?" she asked.

"Well, unless you're doing anything this evening—"

"I hope to have something to report tomorrow morning," she said.

"And don't talk any more about giving notice," he said emphatically. "I'd never get another secretary to fit my ways as you do."

"My dear—" she whispered it to the closed door after he had gone out—"I wonder which is the greater, my folly or your blindness."

"WELL, Father, it's good to see you again, and it must be quite a while since I had the honor of putting my feet in the family trough."

The general frowned, heavily. "I detest this modern slang, Gordon, as I think you know," he said.

"I'm sorry, Father," Gees apologized, with—for him—unusual meekness.

The old man stared uncomfortably at his plate, puffed out his cheeks, raised his eyes to his son's face. "Gordon," he began abruptly, "I wanted a word with you about that luncheon party of yours today. Perhaps you may be able to tell me something about that—er, that remarkable resemblance I noticed. About the lady with Mr. Briggs, I mean." He cleared his throat loudly, and Gees held grimly on to his own patience. "I have the highest regard for Anthony Briggs, as I think you know," the old man went on.

"You have given me that impression," Gees admitted.

"Yes. Yes. And—er, on thinking the matter over, after ringing you this afternoon—but was today your first meeting with the lady?"

"My first sight of her. Yes."

"Ah! Then probably, as far as she herself is concerned, you know little more than I do. As I was saying, on thinking it over, I decided to tell you the story of my meeting with the one who resembled her so very strongly. Not that there is anything to be done, as far as I can see, but knowing Anthony Briggs as you do, you might show by your attitude—"

"Yes. But show what, Father?" Gees inquired, after waiting vainly for the end of the sentence. He had never seen his father less at ease over anything than over this thirty-eight-year-old meeting with somebody who, then, had resembled Cleo Kefra and bore the same name.

"Disapproval of the entanglement," the general said with asperity.

"And make him more set on it than ever," Gees pointed out.

"I am not thinking only of Anthony Briggs," the general said. "I have in mind his—er, his position, and his access to things not in the knowledge of the public. I may be entirely wrong in anticipating—I may be doing him a grave injustice in suggesting that he is capable, under any circumstances, of—er—"

"Spilling the beans," Gees suggested, after waiting in vain.

"Confound those slang phrases!" the general snorted. "I was going to say, of disclosing confidential matters even to those whom he felt he could trust implicitly."

What amounted, Gees thought but did not say, to exactly the same thing. He waited for his father to go on.

"But, as I said," the general continued, "I decided to tell you my story, which concerns, beyond any question in my mind, a member of this lady's family. You will then do what you choose—probably nothing, I gather."

He was getting more and more ponderous, Gees reflected, and made no comment. All the signs pointed to embarrassment over the story he had determined to tell.

"I think I told you I—er, I was on my honeymoon when the incident occurred," the general said. "I had got my captaincy over a year before, and had been seconded for Intelligence, which, let me tell you, was not then what it is now."

"I can well believe it," Gees remarked gravely.

The general gave him a long look, but decided not to pursue that angle of the subject. "It was a starved service," he said. "The South African war was in being, and Omdurman was still a remembered campaign. Egypt, then, was what today would be called a propaganda center, Cairo especially, and you may or may not know that an intelligence officer is never off duty, even for one hour in a year."

"Then why take a honeymoon in Egypt?" Gees murmured.

"Why? My dear boy, my marriage formed an ostensible reason for going there, rendered the real reason inconspicuous. Your mother knew what she was doing—it was that or wait another year or more for marriage, and neither of us wanted to wait. Neither of us regretted it, either. My work—even now I do not intend to define it—left us the greater part of our time, and—well, I need say no more on that head.

"We had been there six weeks and then your mother developed some gastric trouble which I understand is rather common there in the spring months."

"I've heard of it. Commonly known as 'Egyptian tummy,'" Gees said.

"Vulgarly known, you mean," the general reproved him. "Your mother became so ill as to need a nurse, though the doctor assured me there was no real danger. She ran high temperatures, and needed careful attention, that was all.

"One night the nurse assured me I was better out of the way, as my wife was sleeping and ought not to be disturbed, and I went for a walk in the Kasr-el-Nil direction and met—well, even at this length of time I will withhold his name.

"Another Intelligence man, say, who was very glad to see me, since my connection with that service was far less suspected than his own—not suspected at all, in fact.

"It was then between ten and eleven o'clock, and we agreed that I should go out to Mena House, which is almost under the Pyramids. To find and bring in a—well, I will say a dangerous person. An agent provocateur, whose capture would eliminate a very great part of our troubles. I was to make contact with a woman who had been put on his track, and arrest him."

"So you had women in Intelligence, then?" Gees asked.

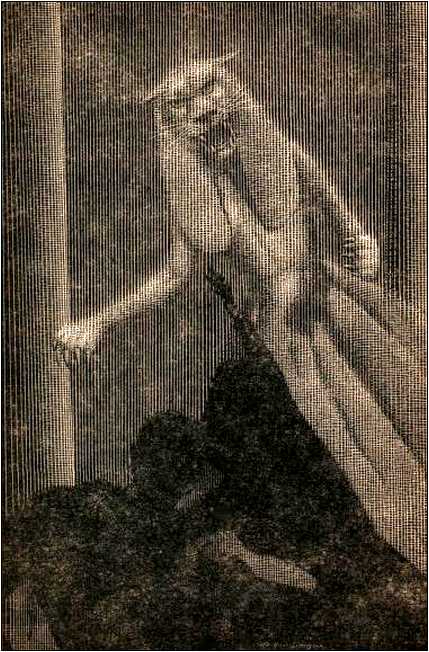

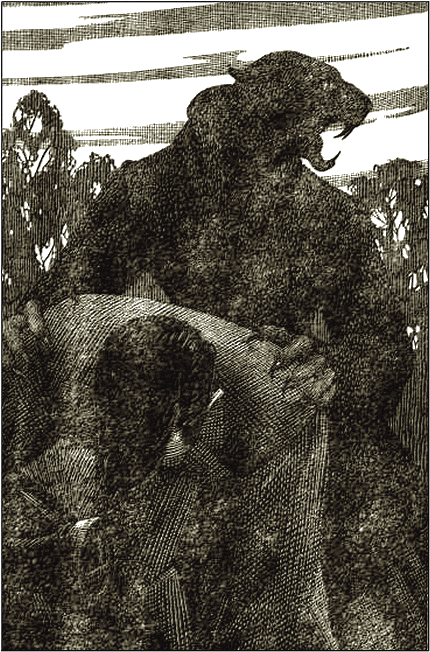

Before us was a woman with the head of a lioness.

"I cannot tell you what or whom we had," his father retorted stiffly. "Only that this woman, whom I had never seen before, would be at Mena House, dressed in a certain way, and I was to assure myself of her identity by a series of pass words.

"I got to the gardens of Mena House and found her, as I thought, alone at one of the tables. I joined her with an apology—which was a part of the passwords. In all, I remember, we had six sentences each to say and she made no mistake whatever in her replies. I was fully satisfied."

He sat silent for so long, then, that Gees ventured a: "Well?"

"SHE said we must wait, and we did." the general resumed. "It was very late, then. I—I had all the confidence in myself that one loses with experience, and—this part I doubt if you can understand—I found that woman very attractive. She seemed so utterly sincere, and dependent on me for the ultimate outcome of the night's work—"

"And she was the living image of Cleo Kefra," Gees said in the pause.

"What made you suspect that?" his father demanded.

He shrugged. "I don't know. But she was, eh?"

"She even gave me that name—Kefra, not the other. Colonel—the man who had sent me there had not told me her name, I realized later. In that service, we used not to deal very largely in names among ourselves. Perhaps she and I sat there an hour, talking on various subjects, and then one of the waiters came and spoke to her, in Arabic. Then she told me it was time to go, to make the capture, and we went to my gharri.

"She showed me a small revolver she carried in her bag, and insisted on coming with me, for my safety, she said.

"And that is very nearly all I can tell you, except that I was taken to Sherhard's two days later, in a complete amnesia, and the woman I should have met was found dead on the bank of the Nile with her throat torn to pieces as if a tiger had mangled it. Oh, and the agent provocateur we should have captured made a clear escape."

"Drugged," Gees observed thoughtfully. "And that is all?"

"Nearly. For the period of amnesia, I shall never be sure whether dreams came back to my mind, or whether—but they must have been dreams.

"One I'm certain was a dream—a woman with the head of a lioness, purring like a cat. Another of the woman who told me her name was Kefra, with her arms round me, holding me back from something—or holding me to keep something off from me. And another of my being intensely grateful to her—heaven only knows why!—and embracing her passionately.

"I would not have told you that last one, except that when I saw your Miss Kefra today it was forced back into my mind as a reality, not as a dream, and I'm so far away from youth and all it means, now, as to confess that it may have been real. For I'm perfectly certain that girl could tempt Saint Anthony himself, if she wished."

"And is tempting the Anthony without the Saint," Gees commented.

"Undoubtedly! But now you see. The amazing, perfect likeness, as if that girl who fooled me—oh, she fooled me completely!—as if she had been resurrected exactly as she was then. Gordon, she's no wife for your friend, whatever her own record may be. With the same name, she belongs to a family that only a generation back consorted with your country's enemies, and belonged in a gang which could kill another woman by mauling her as might a tiger. No, it's a tainted source."

"And if the taint persists, Tony Briggs is in no state to perceive it," Gees added. "A woman with the head of a lioness, purring like a cat. Yes. Yes, I see."

"That was obviously a dream, though a vivid one," the general said.

"One that you were not meant to remember," Gees told him.

"You mean—confound it, boy, what do you mean?"

"I mean this is the most interesting thing I've struck since Hector was a pup," Gees answered with sudden and incautious enthusiasm. "If I told you, you wouldn't believe it. Father, my confidential agency is going to work free gratis and all for nothing—it's started already, as a matter of fact. What you've told me convinces me that this engagement has got to be smashed, though I started by thinking it a fool idea. It isn't."

"Then what do you intend doing?" his father inquired interestedly.

"I'll hear what Eve Madeleine has to say in the morning."

"Eve Madeleine? And who in the world is Eve Madeleine?"

"She's only that when she's absent. To her face, she's Miss Brandon. She'll have a report of some sort for me tomorrow."

"You're not going to tangle her in an affair like this?"

"She's in it up to the neck already, Father, and glad of the chance. She's no fool, I assure you."

"She's a very charming girl, Gordon."

"Quite. I often pat myself on the back over choosing her."

"Yes, you showed good taste," the general said dryly. "In view of my experience with this Miss Kefra's relative, though, you had better be careful not to expose Miss Brandon to any risks."

"Such as a woman with the head of a lioness, purring like a cat."

"Don't talk balderdash, Gordon! I merely told you that to illustrate the impossibility of separating dreams from reality, while in a state of amnesia. To show that all may have been dreams."

"Quite so, Father—and is life anything else?"

"You mean—you attach importance to those fantastic visions?"

"I mean, for any man to tell his own son things like that takes courage, and though I've never doubted yours this is my first chance of seeing it. You're playing high for Tony's sake, Father, and I've got a liking for him, too. On top of which, the cow in the fairway is my special meat, so what have you?"

"I don't know," Sir George Green confessed solemnly, as if the final sentence had been a real question.

"No. Nor me, either." They spoke no more about it until Gees was about to go. Then the old man gripped Gees' arm tightly.

"Good night, Father."

"Good night, my boy, and take care of your Eve Madeleine."

"SWAGGER," Miss Brandon whispered to herself. "Oh, very swagger! But why the police inspector?" She loitered by the railings of the square gardens, just across the road from the high, bronze-and-plate-glass entrance to Gravenor Mansions. By moving a few steps in ether direction, she could see nearly all of the spacious, high-ceiled entrance hall, decorated in mauve and silver, marble-floored, with a sort of Grecian-urn frieze high up on the walls, and here and there plaques of classic design.

There were two elevators. By one of the two massive pairs of outer doors, just inside the hall, stood an obvious police inspector, talking earnestly to a six-foot attendant in a silver- braided mauve uniform.

Miss Brandon moved on a few steps, halted, and turned, wishing the police inspector out of the way.

Rough lipstick and powder, skilfully used, had made wondrous changes in her face; she looked, as she had intended, rather down on her luck; an ancient fox-fur coat showed bare patches on its deep lapels and cuffs; she had bought it earlier in the evening at a Berwick Market stall. Her shoes were good, but both silk stockings were badly laddered, as her short woollen skirt revealed.

When the police inspector emerged, she began walking away from her post, in the direction that he took, until he had got far enough ahead to disregard her. Then she faced about and, crossing the road, went to Gravenor Mansions' entrance, where the tall attendant in uniform swung the door and looked down at her hat rather sourly.

"And what might you be wanting, miss?" he inquired.

"Could I see the caretaker, please?" she asked in reply.

"About little Ernie, is it?" he demanded, with a change to eagerness.

"Little Ernie?" she echoed. "No, it ain't about little Ernie, it's about meself. Who is this little Ernie, anyhow—uh?"

"He's the caretaker's little boy, an' he's lorst," the attendant informed her, with a return to cold aloofness.

"Well, could I see the caretaker?" she persisted, after a pause.

"You couldn't," he answered decidedly. "'E's hout—I mean, he's out. Nigh off his rocker about the kid, too."

"Ow," she said dubiously.

"What chew want the caretaker for?" her interlocutor demanded.

"I thought—" she gave him a swift, coquettish glance and lowered her gaze again—"you see, Lucy Parker—she's a friend of mine—she told me they sometimes want maids here, and I thought—" She broke off and twisted her gloved fingers together in apparent nervousness.

He moved away to swing the heavy door for a couple entering—a couple on whom Miss Brandon instantly turned her back. Mauve-and-silver solemnly escorted Cleo Kefra and Tony Briggs to one of the automatic elevators. The attendant returned to her.

"You can't stand about in 'ere, you know," he said, not unkindly.

"Why, what's the harm if I do?" she demanded, smiling saucily.

"Well, y'know, this place is clarss, that's what it is."

"An' I ain't clarss. Is that what chew mean?"

"I dunno about that." He looked uncomfortable at her half- smiling, satiric gaze. "I come off at ten," he said.

"Ow! An' it's only a little after nine, now. I could do with a little refreshment, too. D'you know anywhere round here?"

"Baker's Arms—private bar," he answered, with a certain eagerness. "It's quiet, an' quite refined. Sid'll serve you, an' if you tell him you're a friend o' Phil Vincent's, he'll look after you."

"Ow," she said again, rather solemnly.

"You will be there, won't you?" he asked anxiously.

"Ten o'clock ain't long," she answered.

"I told you my name—you ain't told me yours," he pointed out.

"Grace Pottert—that's me. An' you're sure there ain't no places goin' here? I was parlormaid in me last place."

"It ain't no use your lookin' for the caretaker. Mr. Katzenbaum hisself engages all the staff, an' you'd have to go to his office. But will I see you at Baker's Arms? You'll be there?"

"I'm going there now." She moved toward the door.

But then she halted, for the door in the corner almost crashed open, and Tony Briggs strode, even clattered, across the marble floor toward the entrance. Hurrying, Phil Vincent got the door swung open for him, and received no reply to his: "Taxi, sir?"

Phil turned back to Miss Brandon as the door swung slowly and silently into its place. He said—"She ain't 'arf combed 'is hair for 'im. I reckon she ain't, by the look of it."

"Why, who are they?" she asked, with evidently intent interest.

"Now, look 'ere," he said persuasively. "If I was to be ketched, talkin' 'ere with you for hours an' hours like this, Mr. Katzenbaum'd ring up the Labor Exchange. I'll tell you all about 'im an' 'er, if you want, round at the Baker's Arms, but not in 'ere, see?"

He held the door for her, as she passed out and remembered to turn to the left.

SO far, she reflected, the intuition which she had let guide

her had produced a possible source of information, but she had

got little out of it. Phil Vincent, too, might prove of more

trouble than use, but fully three-quarters of an hour, at least,

remained before she would see him again, and she determined to

try the Baker's Arms.

She found the private bar door on the first corner, and entered to a clatter of voices. A shirt-sleeved, red-nosed man behind the glass-shuttered bar leaned toward her.

"Any sandwiches?" she inquired.

"Course we got sandwiches, ducky. Wadger like?" he asked.

"I'd like a little politeness, being a friend of Phil Vincent," she told him icily. "And if you've got sandwiches—ham."

"Sus-certainly, miss," he said, with a complete change of manner, "I didn't know you was one o' the Gravenor bunch. Anything to drink?

"A small port, please." Previous experience had taught her it was the least noxious compound she could order in a place of this sort. So she always had it.

She reflected, as she seated herself on a leather-covered bench against the wall opposite the bar, that the Gravenor people demanded, or in any case obtained, respectful service. A flaming- haired damsel moved a half-empty stout glass to make room for her and said, "Pardon, ducks," and Sid—if it were Sid—came from behind the bar with a wet rag with which he scrubbed off the area of long table in front of her.

"Nice evening, ain't it?" said the red-haired girl.

"Quite mild for the time of year," Miss Brandon responded pleasantly.

"We don't have the winters they used to get," the other pursued.

"It ought to be snowing, this time of year," Miss Brandon said.

"Yes, and we don't seem to get no snow, do we?"

Miss Brandon leaned forward and began innocently: "What's this about the caretaker's little boy round at the Gravenor? I've been away, and only just heard about it."

Red-hair was evidently astonished. "Why, it oughter be in all the papers! Little Ernie kidnapped—anyhow, he's lorst. Four o'clock today. You see, Miss—" She paused, invitingly.

"Oh, just Gracie," Miss Brandon said recklessly.

"And I'm Eileen. Well, you see—do you know Gravenor Mansion, though?"

"I've only been there once, to make an appointment with Phil."

"Then you don't know the Parkoots—the caretaker and his wife?"

"I believe Phil did mention some name like that," Miss Brandon lied gravely. "But I didn't know they were the caretakers."

"Oo, yes! They are! And little Ernie—well, you wouldn't believe! That kid ain't only just over two, but—" She lifted her glass, tilted it, and gurgled once.

"As I was sayin'," she went on, "little Ernie's the apple of his mother's eye. She do look after that kid. But little Ernie's lorst, an' the pleece is on it now, an' Parkoot is ravin' distracted, runnin' up an' down since four o'clock today. You'd think half London was lorst, the way he's carryin' on."

"How did it happen?" Miss Brandon asked, and, taking another bite at her sandwich, realized that she had a long way to go.

"Happen?" Eileen echoed, in high treble. "Why, there wasn't any happen about it! Mrs. Parkoot left the door on the jar—they're basement, but the door is top of the steps, leadin' into the vestibule—where you go in—you know! An' little Ernie must of got out. Sweet kid, he is. Why, they all make a fuss of him. There's the Earl of Batwindham in number three. There's him, and that Slugger Potwin—him which used to be the heavy champ, which has the flat opposite the earl's—he'd lay down his life for little Ernie, if it wasn't too expensive. And that Miss Kefra, which they say got so much money she don't know what to do with it—why, Mrs. Parkoot herself told me in here Miss Kefra took that kid up in her arms an' kissed him. An' since four o'clock today little Ernie is lorst, nobody knows where."

Another bite—the ham was delicious, but the bread was thick—and Miss Brandon put down the wreckage of the sandwich, finally. "But somebody must know where," she said, as soon as she could speak.

"That's just it!" Eileen declared, with some excitement. "Phil is on all this afternoon, as I reckon you know! Little Ernie must've come up into the vestibule with the door on the jar, like it was, an' Phil must've seen the kid—but he didn't. And you know, being a friend of Phil's—you know he'd see if as much as a mouse come into that vestibule—couldn't help seeing. And yet he didn't see Ernie, which has disappeared."

"Supposing Mrs. Parkoot left a window open?" Miss Brandon suggested.

"My dee-ear!" Eileen's negative was final. "In a basement well with a twenty-foot wall, an' no way out! An' the kid not three yet!"

"It all sounds very mysterious," Miss Brandon said, and, perforce, moved a few inches nearer her companion. For Phil Vincent, although it was not yet ten o'clock, loomed on her other side, and crowded down into the small available space beside her, grinning widely.

"Darlin', I knew you was a sport!" he said. And, with no more preface, in sight of all the habitues of the private bar, he thrust out an arm, snatched her close, and kissed her full on the lips, blatantly, vigorously—and sickeningly.

She thrust free of his hold, and stood up. Struggling, she got past Eileen, and, unresponsive to Phil's—"'Ere, I say!" got clear and made her way out to the street. There, lest Phil should follow, she ran until she reached the security of the square in which Gravenor Mansions radiated respectability, and thrust out a hand at a crawling taxi. Somebody came out of the shadows to halt beside her and take her arm.

"I say!" he said sympathetically.

She turned on him, tigress-wise. "I've been kissed!" She exclaimed. "Do you hear?"

He asked, unemotionally, "Do you wish to lay a charge, Miss Brandon. The name, I conjecture, is Philip Vincent."

"The name! I want to go home—do you hear? Nothing else, but to go home! If I'd known!"

Inspector Tott opened the door of the taxi, which had stopped beside them. Still holding her arm, he helped her in, and then gave the driver her address. Then, before closing the door, he looked in on her.

He said, "Green ought to have known better—tell him so. And he'll get nothing on the Kefra woman this way. If he wants to know anything about that kidnapping, tell him I've got the whole story. Except—there ain't any, apart from the kid's disappearance."

"Oh, tell him to go on!" she begged desperately.

"Righty-ho, miss." He closed the door on her, and the taxi moved away, leaving him at the pavement edge, a melancholy, unperturbed figure of a man.

A SLIGHT shudder marked the end of Miss Brandon's recital. Gees, perched on the end of her desk with a folded newspaper under his arm, eyed her sympathetically, and offered his open cigarette case.

"No, thank you. I don't feel like smoking."

"Philip Vincent, eh?" he reflected. "Well, Philip Vincent is going to get it and get it good. Oh, yes! I'll attend to him myself, shortly. I'm very sorry, Miss Brandon."

"And all of it so absolutely futile!" she exclaimed bitterly.

"I'd say, very far from futile!" he dissented. "Two things stick out, to me. One, that Tony and Cleo Kefra had a peach of a row, from what you tell me of his exit. The other—well, I don't know, quite. But the evening papers may tell."

She gazed up at him, questioningly. "Tell what, Mr. Green?"

"Little Ernie, you say, was missing since four o'clock, with only one available way out from the caretaker's quarters. They'd have their own entrance somewhere round the side or at the back, naturally, and he might have got out that way, but on the scrappy evidence you got it's not likely. Apparently that door 'on the jar' let him into the entrance hall, where this Philip Vincent was on duty."

"And therefore must have seen him, if he had gone that way," she pointed out. "The entrance hall is absolutely bare, and it was quite impossible for the child to appear in it without Vincent seeing him."

"The child is so small that Miss Kefra took him up in her arms and kissed him. Just over two years old, according to your Eileen. Could a toddler like that push one of those metal and glass doors open?"

"No," she said decidedly. "But somebody might have—"

"Let him out, you were going to say," Gees finished for her. "One of the tenants there? They all know the child, apparently, and the worst sort of moron would not let a two-year-old into the street alone.

"Even then, kidnapping in the street is practically out of the question—small kids aren't such valuable commodities in these days that people risk picking 'em up on sight and running off with 'em. Also, that square in the middle of the afternoon has got taxis on a rank nearly opposite the Gravenor entrance, I happen to know, and there are chauffeurs with cars waiting about—somebody would have seen the child if he had been snatched up in the street, and since the police are on to it they'd have got information about it."

"You mean—little Ernie is somewhere in the building?" she asked.

He shook his head. "Not now," he said very gravely, and, unfolding his newspaper, put it down before her. "Take a look at that."

He put a finger on a staring headline and, after a glance up at him, she read:

GHASTLY DISCOVERY ON WIMBLEDON COMMON

Shortly after midnight, P.C. Ambrose Wright discovered a fiber suitcase, half-hidden among some gorse bushes on Wimbledon Common, nearly opposite the pond beside the Kingston Road. On opening the case, he was horrified to discover the nude and terribly mutilated body of a male child, apparently about two years of age. The child's throat was fearfully lacerated, and this and other injuries made it appear that the tragedy was due to an attack by some large, carnivorous animal of the cat species.

P.C. Wright, at the time of the discovery, was patrolling from Kingston toward the top of Putney Hill. The point at which he found the case is within a dozen yards of the main road, which, even at that late hour, is far from deserted. Three cars, Wright states, passed him, going in the direction of the Kingston by-pass, between the entrance to the cemetery and the top of the hill, a distance of about four hundred yards—more or less. Rime on the grass went to prove that the case had been thrown toward the bushes from the road, since it had fallen into position after the ground-frost had whitened the grass, and there were no footprints, except for those made by the constable himself, in the vicinity. In all probability the case was thrown from a passing car, since, if a pedestrian had been carrying it, he would almost certainly have attracted notice from others using this road.

A far greater number of people, both children and adults, is missing at any given time than is generally supposed, and, so far, no clue is available as to the identity of this unfortunate infant. The suitcase, a cheap, fiber-and-cane article, well worn, bears no labels or distinguishing marks by which it might be traced. There is a possibility that a child belonging to some traveling menagerie might have strayed too near the cages containing savage beasts, and that the parents disposed of the body in this way to avert inquiries and subsequent trouble. Against this is the fact that no menageries are known to have been on the roads in this district for weeks past.

Medical examination will, of course, reveal more fully the way in which the child came by his death, but it already appears certain that no human agency is responsible.

Miss Brandon looked up. She said,

"Very—badly—written," rather shakily, and Gees saw

that she had lost color.

"I'd dissent, by the effect it's had on you," he said. "But with this—the ability to connect up these two things before any others make the connection, your trip last night was very far from futile, you see. It enables me to get on to Tony Briggs before he can connect up."

"But—but what on earth do you mean?" she asked fearfully.

"I don't know myself." he confessed. "Between the British Museum and my father, and what I already knew—and this Cleo Kefra herself—I'm utterly puzzled. Only—it's all wrong—all wrong!"

Abruptly he snatched up the telephone receiver from its rest on her desk, put it to his ear, and dialled. "Mr. Briggs—Mr. Anthony Briggs, please," he said, when he got his response. Then—"Mr. Green."

After a pause, "Hullo, Tony. Gees speaking. I suppose you're not available for lunch today?" He frowned. "No, I thought you wouldn't be. Too bad. Well, look here. The nearest Lyons to the Parliament end of Whitehall—blow in and look for me in about twenty minutes, and I'll buy the coffee. Right?"

Miss Brandon watched him nod and smile at the response he got.

"Ah! Yes, I see! Leaving you desolate, is she? Well, that accounts for it. Yes. In twenty minutes."

He replaced the receiver, and again took out his cigarette case Miss Brandon took one this time. He said, "I can walk it in ten minutes, from here," and lighted one up for her and himself.

"She ought to have been dark," she said abruptly.

"I believe the mummies go to show they were not all dark," he dissented. "The early dynasties. Besides—" he broke off, thoughtfully. "Probably in all Egypt today there are not more than half a dozen families—maybe not more than one or two—of the pure-blooded race that was, in the days of the Pharaohs. The present race is mongrel, more Arab than anything else, and she's got no Arab blood in her, by my reckoning."

"Mr Green, you're not thinking of connecting her with the murder of that child?" she asked, with sudden fear.

"I tell you I don't know a thing!" he exclaimed, with equally sudden irritation. "Sorry, Miss Brandon—I didn't mean to bark. I'll get along, now, and—do forgive me for landing you with that mess last night, won't you?"

"Why, of course, Mr. Green! It wasn't your fault in the least."

Two minutes later, with his hat in his hand, he paused again in the doorway. "I may have another commission for you, Miss Brandon," he said. "Tony Briggs tells me she's going away for a few days, and I may want you to keep track of her. I'll know better after I've seen him, though. I'll be back in an hour or so."

Tony Briggs was prompt and unruffled. There was just a suggestion of pouter pigeon in his bearing, and his pink-and- white face wore the expression of virtue rewarded.

"Quite a cheery party yesterday, wasn't it?" he said, patting the tablecloth. "I thought your Miss Brandon was looking remarkably attractive. Have you fallen for her yet?"

"With you an object lesson in falling, I'm keeping on my feet," Gees said gravely. "And to anticipate your next remark—she is."

"What?" Tony asked.

"All that, and then some. Did you take her back after lunch?"

"Well, naturally!"

"Took the whole of the afternoon off, huh?"

"I did not! I took her as far as the Gravenor and then came back to work—in the same taxi. You seem to think I never work!"

"Didn't even go up to her flat with her for a quiet good-by? Tony, don't strain my credulity too far!"

"Honestly, old man! I saw her to the lift, and left her."

"I must have independent evidence on that. Get the one-headed Cerberus in that entrance hall to testify to it on oath."

"Oh, cut it out! Besides, he was nowhere in sight—we had the entrance hall to ourselves."

"Oho! Let me see... Three o'clock or thereabouts when you left the Berkeley, quarter of an hour to Gravenor Mansions, and call it twenty minutes from there to your office. Bet you a bob, Tony, with that entrance hall to yourselves, you weren't back before half past four."

"Hand over," and Tony stretched out his hand. "I was well settled at my desk when I heard Big Ben chime a quarter past. Fast and honor, Gees. One shilling, please."

With apparent reluctance Gees took a shilling from his pocket and handed it over. He said, "Even allowing for traffic holdups, that gives you twenty minutes to say good-by in that entrance hall."

"What the blazes is it to you if it does?" Tony demanded irritably.

"Sorry, Tony—you know I was only clowning. But you said on the phone she's going away today. Where's she off to—back to Egypt?"

"If she were," Tony said decidedly, "I'd find some excuse for going there too. No, she's got a place she rented, furnished down in Gloucestershire, and I'm seeing her off for Cheltenham after lunch. Staying there till Tuesday week, and I go down for two long weekends and come back with her after the second."

"Uh-huh! What's your lady mother say about it?"

"Oh, blast it, Gees, you've got a nasty mind! And this isn't the Victorian age, either. Besides, she's having Lady Benderneck to stay with her, and other people as well, probably."

"Cheltenham, eh? Sleepy place. I don't care for it."

"But she's not in Cheltenham," Tony said "Her place is miles out—Barnby-under-something Grange, it's called, but if she didn't take an express through to Cheltenham she'd be pottering about half the day at wayside stations on a slow train. Her man meets her there with the car—meets me, too, tomorrow evening when I go down. So there you are. Do I step down from the witness box, or do you cross-examine further?"

"M'lud, no further questions."

Tony smiled. "You haven't told me what you thought of Cleo."

"What could I tell you?" Gees countered. "You had only to see the way other people took her entry to realize you had far the most interesting woman—girl—in the place. She's got a brain like—like a linotype machine, which they say is seven men's brains, and she dresses as well as you do, which is saying much. I've never seen such eyes, and her voice is a revelation in perfection of tone. Anymore?"

"That's quite enough," Tony said, rather grimly.

"What's more important to me is her opinion of me."

"To be absolutely frank," Tony told him, "you did not make a good impression. In fact—well—never mind, though."

Back to Gees' recollection came Miss Brandon's account of the way in which Tony had charged through that entrance hall and out from the block of mansions the night before. He nodded, gravely. "I won't," he said, and drank the last of his coffee.

"I thought you were rather bristly, somehow," Tony said. "Not quite your usual self, when you were talking to her."

Gees said nothing and presently they finished their coffee, paid up and separated.

Gees meandered thoughtfully along Whitehall, came to a full stop and made for a telephone booth, inserted two pennies, and dialed. After a brief delay he got Inspector Tott, who demanded very irritably what he wanted.

"To stand you lunch at the Junior Nomads, Inspector," he answered. "Today, one-fifteen. Can do?"

"Can not do, thanking you all the same, Mister Green," Tott snapped at him. "I told you when I came to see you that this was not an affair for any official action, and that's that."

"Then why were you hanging around the Gravenor last night?" Gees demanded.

"None of your business."

Gees laughed softly into the transmitter. "Don't hang up for a second, Inspector. You heard about the missing child, of course?"

"Being investigated by that division."

"Has Parkoot—I believe that is the name—has he been to Wimbledon yet to see if he can identify the body found last night?"

"Here! What on earth are you getting at?" Tott demanded sharply.

"One-fifteen, at the Junior Nomads. Change your mind, Inspector," Gees suggested. "I really need official backing for something I want to do in that case, not the other."

"All—right, Mr. Green," Tott answered, after a long pause. "But if you are thinking of leading me up on some blasted—"

Gees mumbled his entire innocence of subtlety, hung up and emerged from the booth to gaze at a "Lunch Edition" poster, sight of which prompted him to buy a copy. The late news column gave him:

SUITCASE MYSTERY

The body of a male child found in a suitcase just after midnight on Wimbledon Common has been identified by Mr. Edwin Parkoot, of Gravenor Mansions, as that of his son Ernest, whose disappearance was reported to the police yesterday afternoon. It is understood that figures on the suitcase indicate that it was purchased recently, and inquiries are being pursued with a view to tracing the purchaser.

"Bah!" said Gees to himself. He handed it back to the man from

whom he had bought it.

"Finished with it," he said. "You can have it."

He walked on toward Charing Cross. "Oh, Lord, be good to them, somehow!" he murmured. "It must be hell to lose a child any way, but that way—be good to them somehow!"

"This is Mr. Green, Crampton." Tott introduced the quietly dressed man who joined them after lunch. "Inspector Crampton, Mr. Green. And I might tell you, Crampton, that what he's got to say might be worth hearing, though he's got no official standing. He was in the Force for two years some while ago, and a damned nuisance he was, too, but he's got an indirect line on this kidnapping business that neither you nor I has a chance of getting. It's your case, so I'm handing him over to you, as he asked."

"Yes, I know your agency," Crampton said. "And you think you might be able to give us a helping hand over this Parkoot business?"

"Well, thank you very much, Mr. Green, for my good lunch, and I'll leave you to Crampton," Tott put in. "See you soon, Crampton."

"I don't know that I can give you much, Inspector," Gees said, "but I may clear up a point or two. Is it possible to have a word with Parkoot, or is he—"

"He's cold fury," Crampton said, "and only too anxious to get his hands on whoever did it, poor chap. She's down and out—you can't see her. But you want—"

"To find out things," Gees finished. "Can you come along with me and see Parkoot? He'll be at the Gravenor?"

"We'll go right along," Crampton promised. "But—" as they went toward the street—"do you mind telling me where you come in? I mean—what's your angle on a case like this?"

"A possible lead to an inquiry of my own," Gees answered, "and since my inquiry couldn't possibly be a police affair—at least, for the present—I shall have to ask you to leave it at that."

"What's good enough for Inspector Tott is good enough for me," Crampton said.

MISS BRANDON'S description was enough to convince Gees that it

was Philip Vincent who swung the heavy door for them when they

reached the Gravenor; and he noted Vincent's respectful salute to

the inspector. He halted just inside the door to watch it slowly

close against the pneumatic cushioning cylinder, and then,

grasping the handle, swung it open again.

"You see, Inspector," he said, "that child couldn't have opened it. It's a sixty-pound pull, at least."

"They're kept open in the warm weather, sir," Vincent put in.

"Was any door left open yesterday afternoon?" Gees asked him.

He shook his head. "No, sir," he answered with finality. "Never, in the winter months. Them cylinders have to be taken off, for that."

"And they're all on." Gees gave the man a steady, appraising look, and then turned to the inspector again. "Let's go. Best to get it over with."

But when Parkoot, a middle-aged, heavily-built and tall man, faced them in the doorway, Gees saw that he had no uncontrolled victim of a tragedy to face. The man was grimly impassive.

"This is Mr. Green, Parkoot," Crampton told him. "He thinks he may be able to help in—well, our investigation."

"If that's so, Mr. Green," Parkoot said slowly, "God will bless you. I know you can't give him back to us, but—Pleased to meet you, sir."

Gees shook his hand heartily, and felt respect for the man's courage. "A few questions, if you don't mind," he said.

Parkoot came out into the basement corridor, and closed the door softly behind him. "The missus is asleep," he explained.

The cigarette case appeared as Gees leaned against the polished marble wall. Gees lighted up. "As good here as anywhere," he said. "A first question, Mr. Parkoot. That entrance hall is in charge of an attendant. Is he supposed to leave it?"

"No, sir."

"Meal times?" Gees asked laconically.

"Relief," Parkoot answered.

"Then that's that. What sort of man is Vincent?"

"Oh, quite reliable, sir, if that's what you mean. He was on yesterday afternoon, when—when it happened, and what I can't make out is how it happened that Ernie got out, because the missus was lying down, and our own door at the side was locked. And the door at the top of the stairs was on the jar, but Vincent'll take his dyin' oath the kid never went that way. So—well!"

"Not well," and Gees shook his head, while Crampton maintained an interested silence. "Not much doing up there in mid-afternoon, as a rule, is there, Parkoot?" he asked casually.

"I'd say it's a dull job, but—" He broke off, gloomily.

"How many flats are there in the block?"

"Twenty-two, sir. But if you think—" Again he broke off.

"We've got to prove, not think," Gees told him, and Crampton nodded. "Service here, or do the tenants keep their own servants?"

"Either way, sir. There's accommodations for one servant in each flat—two at a pinch—and our own restaurant and staff."

"I see. Tell me this, then. Why was Vincent absent from that hall for at least twenty minutes, between three-thirty and four yesterday afternoon?"

"That's impossible, sir," Parkoot said firmly. "He wasn't—and he knows it'd cost him his job, too. No, he wasn't."

"Very well, he wasn't. How many of the tenants have their own attendants—living in the flats, I mean?"

"Very few, sir. The trouble of getting servants makes most of 'em rely on our staff for everything. There's—let me see. Lord Batheum—they say that's how you ought to pronounce his name—he's got a maid: that boxer chap, Potwin, keeps an old army man to look after him, and Miss Kefra in number thirteen's got a foreigner, sort of chauffeur and houseman and everything else—but they're away. So is Lord Batheum, as far as that goes, though his maid is still here."

"And the rest depend on your staff, eh? Do the staff have rooms here, or live out? I've a reason for asking."

"The chef and his two kitchen lads live in—not the others," Parkoot answered. "Though I don't see how they—"

"Come into it—no. But now I want to take a long chance—a very long chance—and I wish you two'd come with me while I take it. Up to Lord Batheum's flat, if you will."

"I get it," Crampton said quietly. "Yes—let's go."

The caretaker led them along the corridor to the foot of the stairway and pressed a button beside a door. A lift descended almost inaudibly, and stopped. He opened the door, ushered the two in, and followed them. The lift went up, stopped, and they emerged to a carpeted corridor.

"That's his door, sir." Parkoot pointed as he spoke, and Gees advanced and pressed a bell beside the door.

He pressed again after a long interval, and the door swung open to reveal a tall, pert-looking, rather attractive girl in a black silk uniform.

"His lordship is notatome," she said, sharply, before Gees spoke.

"So I understand." He slipped his foot into the door-opening. "You are, I see, just as you were yesterday afternoon. But quite on your own, I take it, today. Are you all alone?"

"Mr. Parkoot, are you going to stand there and see him insult me?" she demanded shrilly. "Let me shut this door, you! I—" Then he caught sight of Inspector Crampton, and stopped, open- mouthed.

"How long was Vincent in here with you yesterday?" Gees drawled.

"Oo-h! You liar!" she cried, and, reddening, gulped.

"Was it one hour, or two?"

"It wasn't half an hour—" she began—and stopped.

"That's enough, Sir," Parkoot said, and turned toward the lift. Inspector Crampton said, "Here!" and went to follow him, but he slid the door closed and went down alone. Gees and the inspector made for the stairs and raced down: but they knew the lift would beat them.

They came to the main floor just in time to see Parkoot swing Vincent about. From a half crouch he landed one tremendous blow with his right on the point of the jaw, with plenty of weight to back it. Lifted off his feet, Vincent crashed to the marble floor, and Parkoot stood over him. The other two came beside the caretaker, and all three stood waiting until Vincent opened his eyes.

"Get up!" Parkoot's admonition was an almost animal growl. "Get up! Strip that uniform off, and get out, before I kill you!"

"Again they waited. Presently Vincent managed to get on his feet, and staggered uncertainly toward the basement stairs and down them.

"Will he come out this way, Parkoot?" Gees asked.

"No, sir. By the side door—it's spring-latched." He held up his hand to look at his skinned knuckles, and even smiled.

"I'd like you to come along with me, Inspector, if you will," Gees said. "I haven't finished with Vincent, yet."

"YOU said you were taking a long chance," Inspector Crampton remarked as he followed Gees down to the basement. "You did, too, with that girl. A longer one than I'd care to take."

"And yet it wasn't so very long," Gees told him. "She squealed before she was hurt, gave herself away hopelessly before I accused her of anything. Besides, it was acting on information received—from two entirely independent sources."

"That's his locker room, sir." Parkoot pointed at a door along the corridor. "D'you want me to stay?"

"I think not, Parkoot." Crampton answered, and smiled slightly. "You might kill him, if we didn't hold you back."

"Then I'll go along and ring up the agency to send a man in at once to replace him," Parkoot said, and entered his own quarters, closing his door gently. Crampton pointed at a half-glazed door at the end of the corridor.

"That's the only other way the kid could have got out," he said. "Been taken out, rather, for you can see he couldn't have opened that door himself—couldn't have reached up to that Yale knob to turn the latch."

"How did the child get into this corridor?" Gees asked.

"Mrs. Parkoot left her door open so he could play about in it—he couldn't come to any harm," Crampton explained, "and somehow that door at the top of the stairs, leading to the entrance hall, happened to be left ajar. But how he got out of that hall—"

Gees almost said, "He didn't," but thought better of it. They waited, and finally Vincent, sullen and tight-lipped, appeared in street clothes.

"We want a word or two with you, Vincent," Crampton said.

"Oh, do you? Well, for a start, I want you to arrest Parkoot for assault. And I'm goin' to get damages out of him, too."

"Quite a good idea," Gees cooed softly. "Oh, quite a good idea! And don't forget to call that girl in his lordship's flat as evidence."

"So she spilt, did she, the—"

"Stow it!" Gees barked. "What time was it when you left the hall to go up to that flat yesterday afternoon?"

"Whatever she told you," Vincent mumbled, "I was in the hall till over a quarter past three, and I was down again by four o'clock."

"Contradicting each other already, you see," Gees observed.

"I don't care what she told you!" Vincent almost shouted. "I'll take oath on it—I wasn't away more'n forty minutes at the outside."

"Three fifteen to four o'clock, call it," Crampton commented. "The period in which the child disappeared."

"Nobody asked me to keep an eye on the kid," Vincent said sullenly.

"Many people in and out during the afternoon, as a rule?" Gees asked him.

"Hardly anyone, between three and five," he answered.

"Did you stay in the entrance hall all the rest of the time yesterday?"

"Yes, I did, except when I give Miss Kefra's man a hand with her trunks, because he was takin' 'em down to her car, so's to be there to meet her today. An' goin' outside to get taxis for people. Her, for one, when she went out to dinner."

"Did you leave the hall to help with the trunks before or after getting a taxi for Miss Kefra?"

"Before—no, it was after, a good quarter an hour after. Why—what's that got to do with it? The kid wasn't in the trunks—the police was lookin' for 'im, by that time. After eight, it was."

"Now what gave you the idea of connecting the child with the trunks, I wonder?" Gees mused.

"I didn't do nuthin' o' the sort!" Vincent protested indignantly. "I said he wasn't in the trunks, that's all. I seen Miss Kefra pick that kid up an' kiss him, one day when the door was left on the jar before an' he happened to stray up into the hall when she was comin' down in the lift, an' that old dofferer of a man of hers couldn't swat a fly if he tried. An' the kid was snatched away out of here."

"Yes, snatched away out of here," Gees mused aloud again. "I expect you'll see the suitcase at the inquest, and be able to tell if it went out of here yesterday while you were in the hall."

"No suitcase of any sort went out!" Vincent protested. "An' that kid was snatched out alive, not took out dead in a case. Kidnappers, that's what it was."

They left the man to himself and ascended to the empty entrance hall. There Gees paused.

"Do you happen to have any list of the people here?" he asked.

Crampton felt in his breast pocket and brought out a small, folded, white sheet.

In silence Gees looked down the list. Beside No. 13 he saw the names of Miss Cleo Kefra and Saleh ibn Nahor, personal attendant. He refolded the paper and handed it back.

"Thank you," he said. "No, it couldn't be anyone here."

"Well, I'm much obliged to you, Mr. Green," Crampton said. "Now do you wish to make any more inquiries?"

Gees shook his head. "Not now, thanks," he answered. "If—if the business that's interesting me just now should happen to cross any of your line, I know where to get in touch with you."

As he went on his way, he murmured to himself: "Saleh ibn Nahor—" Then he took out an envelope and pencil, and wrote the name down. Then he hailed a taxi to take him to Little Oakfield Street for tea with Miss Brandon.

BUT tea with Miss Brandon was not the peaceful function Gees

anticipated. He had just seated himself on the corner of her desk

when the doorbell began a peal that suggested a desire to run the

battery down. Gees got on his feet.

"I'll go, Miss Brandon." He went to the door and opened it. "Easy, man," Gees admonished, ignoring the ominous expression on Tony Briggs' face.

"I want to know," Tony began coldly, "why you—"

"Not here," Gees interrupted. "Come inside."

In angry silence Tony followed him to his room. He pointed to the deep-seated, leather-upholstered chair.

"I don't want to sit down," Tony said stubbornly.

"I do," Gees observed, and did. "Now, go ahead."

"I want to know what you—" Tony paused to correct himself, and went on with meticulous care—"what was the idea of Miss Brandon, in obvious disguise, masquerading in the entrance hall of Gravenor Mansions last night. Spying there, in fact. By your orders?"

"Oh, the Parkoot business," Gees said. "That missing kid. Yes. Wait a second—I'll get Miss Brandon herself along to explain." He pressed the buzzer on his desk, and offered his cigarette case.

"No! Not now!" said Tony savagely.

Gees took one for himself. "Oh, Miss Brandon," he said as she entered, "You've met Briggs. He wants to know what you mean by being at Gravenor Mansions last night. I'm just back from my talk with Crampton, and you'd better tell him how we're interested in this case of the missing child—and the finding of the body out at Wimbledon, and all the rest of it." He gave her a long look.

"I went to Gravenor Mansions last night, Mr. Briggs," Miss Brandon said coolly, "and obtained some information about the missing child—long before it was connected with the Wimbledon tragedy—which Mr. Green was good enough to say was very useful. Is that all, Mr. Green?"

Gees got on his feet. "You see, Tony? There's no connection between Miss Brandon's visit to the Gravenor and you or anyone you know there. Now what's the trouble?"

"I—well—Miss Kefra recognized Miss Brandon, obviously disguised, last night—" Tony broke off.

"And chalked another dark stroke against my already unattractive name," Gees finished for him. "You ought to realize, Tony, that my agency goes in for all sorts of investigations. So there you are, Tony, blaming me for a sheer coincidence. Why?"

"Miss Kefra thought—" Tony began, and stopped.

"Supposing I started thinking?" Gees exclaimed with angry energy. "Supposing I alleged that one of Miss Kefra's trunks, taken out of her flat last night by her man, had inside it the suitcase which held the body of that child—No, shut up, Tony! I've got just as much right to allege an absurdity like that as you have to come here and accuse me of setting Miss Brandon on to spy on Miss Kefra. Now you can either apologize and stay for a cup of tea, or get out."

"I apologize humbly to you both," Tony said. "But I mustn't stay now."

"Look here, Tony, what time do you go to her country place tomorrow?"

"By the same train she took today," Tony said. "Cleo's meeting me at Cheltenham with her car, and Lady Benderneck is traveling down with me."

"Well, then—when do you start back? Monday?"

Tony nodded.

"Well, look here. I shall be down Shropshire way myself on Sunday. Suppose I pick you up at ten Monday morning? Then I could have a word with Miss Kefra and wipe this blot off my 'scutcheon."

"Ye-es," Tony assented, very dubiously.

"Fine!" Gees exclaimed. "Now what's the address?"

"It's the Grange, Barnby-under-Hedlington. I've never been there, so I can't tell you anything about the road—"

"Leave it to me," Gees interposed, "and count on seeing me somewhere round ten on Monday morning."

"I really must go now, Gees," Tony said, glancing at his wristwatch. "Awfully sorry about this misunderstanding—"

"I'll clear it all up before I fetch you away on Monday morning," Gees interrupted, accompanying him out into the corridor.

"But if you're looking into this affair of the missing child—" Tony half-questioned, pausing in his stride.

"Oh, my part in that is finished, now—I've handed it over to Inspector Crampton."

He went into Miss Brandon's room after closing the door on Tony. She said: "So I was futile, after all."

"On the other hand, Miss Brandon, this bee in the lady's bonnet—the one that fetched Tony here with murder in his eyes as soon as he had said good-by to her—it clinches things. People don't imagine they're being shadowed like that unless there's some reason for shadowing them."

"You suspect—what?" she asked. "Not that she had anything to do with the disappearance of that child, surely?"

"An open mind," he answered, "is as useful as a pocket corkscrew." He held one up as he spoke. "I might be able to tell you more when I get back next Tuesday."

"But I thought it was to be Monday."

"You'd be surprised. Meanwhile, Miss Brandon, Vincent took the count in the Gravenor entrance hall today, and is now one of the unemployed, thanks to me."

She put the teapot down on the tray and stared at him, silently.

"Well—that's something," she said nervously. "But—but I wish you'd tell me—about Miss Kefra—"

"I assure you there's absolutely nothing to tell—yet," he said. He smiled at her, but she found no smile of her own with which to answer.

SLENDERER, even, than she normally appeared, and to Tony Briggs bewilderingly alluring, Cleo Kefra let him hold her close for almost a minute, and then drew away.

"Your friend will be here at any moment," she said. "Have you had breakfast—" she glanced at the table—"or did you wait for me?"

"Of course I waited, darling," he told here. "As if—but there's a wire from him. I shall have to ask you to turn the car out to take me to Cheltenham, after all. He's broken down. He may get here this afternoon. There's the wire."

Glancing at the top of the message, she saw it had been handed in at Ludlow at 8:38 A.M., and put it down to turn to Tony.

"I will order the car for you, dear," she said, and, advancing one slippered, tiny foot, set it on a bell-push in front of her. After that, she seated herself, and gestured him to the place opposite her.

"So—I must tell him you have gone," she said. "Or leave word for him, perhaps. Darling, get me one kidney, and no bacon."

Going to the sideboard, he uncovered the dish, and hesitated.

"They look badly underdone, to me, Cleo," he said dubiously.

"But they are not, really," she said. "One, please."

Carefully, even distastefully, he transferred two halves of kidney from the dish to a warmed plate, which he put down before her. The service gave him opportunity to lean down and kiss her.

"You're so lovely, Cleo! I hoped you'd have been down sooner, since it's my last morning here."

She laughed. "Until Friday—five days! Darling, this is very early for me. I come alive at night, not with the morning."

A wizened, wrinkled, five-foot-nothing, white-haired, clean- shaven man, with startlingly youthful blue eyes entered noiselessly. He said: "You rang, madam?"