RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

After three days of chasing around town as bodyguard to a beautiful girl—at a hundred bucks a day and all expenses paid— Don Manton was beginning to feel that life had its moments after all. But it wasn't long after he looked into the gaunt, parchment-like face of a man named Borchard that he realized how few these moments can be.

Headpiece from "Secret Agent 'X'"

I WAS sitting in a box with Anne Seymour, viewing a revival performance of “Emperor Jones” when I became aware that the man, Borchard, was in the house.

It was a sweet job, and I had begun to appreciate it after three days of acting as bodyguard for Miss Seymour. When her old man had hired me, he said, “Mr. Manton, expense is no object. You understand that Anne is our only daughter. Whatever this thing is that threatens her, it will be your duty to guard her against it, to find out the nature of the danger. We ourselves have been unable to get any information from her. All we know is that she's deathly afraid of something, that it is rendering her melancholy, is reducing her to a mere shadow of herself.”

Well, if you can't soak millionaires, whom are you going to soak? So, for the past three days I had been going to parties and shows, riding in taxis—in short, living on the fat of the land, with all expenses paid, and a hundred bucks a day salary.

That was all to the good, except that it was a little monotonous. It's not bad racing around all over town with the most beautiful girl in the city, if she'd only loosen up and talk a little. But in all the three days, Anne Seymour hadn't said more than about fifteen words to me. Always there was that queer sort of haunted, frightened look in her eyes. Whenever I took her arm to lead her to a table in a restaurant, or to guide her down the aisle of a theatre, she felt cold and clammy to my touch. I guess it was beginning to get on my nerves.

And on top of this we had to be seeing this goofy show that takes place in the African jungle or some place, with this guy running away through the forest, chased by natives who want to stick pins and needles or something into him and make him miserable in general. And all through it there's this queer, insistent beating of the tom-toms, like water dropping on your forehead, drip, drip, drip.

Anne Seymour was sitting straight and still next to me, her proud, beautiful profile seeming to be cut out of marble.

And then I got the funny feeling that there was somebody in the house staring at us. I looked around quickly and, as if drawn by a magnet, my eyes found the eyes of a man who was sitting in the fourth row of the orchestra. He was lean, and his face was like parchment. If it weren't for his eyes, you'd think he was a mummy in evening dress. Those eyes were deep and black—and bad. Somehow or other, I got the idea that this guy might be the devil himself, all dressed up. He hadn't been looking at me; he had been staring all the while at Anne Seymour in a curiously appraising sort of way.

I swung my eyes away from him as if I hadn't noticed him particularly, looked toward the stage, and nudged Anne Seymour, whispered to her out of the corner of my mouth, “Don't turn now. But see if you know that man in the fourth row.”

“I've already seen him,” she said huskily. She hadn't turned either, was still sitting straight, erect, and was whispering with hardly any motion of her lips. “I told dad it was no use getting me a bodyguard. You'll only be killed. I can't escape that man.”

“Listen, Miss Seymour,” I said earnestly, “my name is Don Manton. I'm no baby, and I'm no youngster at this game. You tell me what it's all about and I'll fix that guy's wagon for him. What's he got on you?”

Suddenly a shudder seemed to rack her body. “I suppose I ought to tell you all about it. It's not fair to you not to. Will you promise not to tell dad or mother?”

“Okay,” I said. I'd have promised her anything right then, if it meant getting the truth out of her.

She went on tensely. “His name is Borchard. He's been at several places where I have been in the past week or two—theatres, night clubs, parties. Nobody knows his business, but he's extremely wealthy. And—he always looks at me like that. I seem to feel the blood freezing within me when his eyes are on me.”

“Is that all?” I asked.

“No. One thing more. Monday night—that's four nights ago—I woke up, from a sound sleep. It must have been three or four o'clock in the morning. I had felt a sudden pain in my arm—like a pin prick. I opened my eyes, and there was his face, leaning over me. And—God—it was the most horrible thing in the world. He seemed to be exuding evil. I started to scream, but my muscles were frozen. And then I suddenly became weak, and lost consciousness. I woke up in the morning, weak and dazed. I might have thought it was all a dream, except for a little red spot on my left arm. He must have done something to me—given me some sort of injection.”

“Why have you kept all this a secret?” I asked her, raising my voice a little so as to be heard above the terrified shrieks of the man on the stage who was being haunted by the ghosts of his past crimes.

Miss Seymour said, “I don't know. I suppose I was afraid of being laughed at. And since that night I've had all sorts of queer feelings. Perhaps a dozen times I've had a sudden desire to leave everything and run out into the night. It seemed that this Borchard was calling to me, calling to me, always calling to me.”

Her face was white, drawn, tense. “He—he's calling me—now.” Her little hand was clenched in her lap as if she were resisting some powerful, magnetic urge.

And just then the curtain dropped on the stage. Intermission had come. I looked down to the orchestra. The man, Borchard, was not staring at her now. He was getting up from his seat.

I turned back to Anne Seymour. She seemed to be more at ease. She managed a faint smile. “I'm—better now.”

I got up, and excused myself. “I'm going to see what's to be done about this. You stay right here, Miss Seymour, and don't move. Wait till I come back.”

She nodded meekly. Somehow, she seemed to feel better for having unburdened herself to me. “Be careful, Mr. Manton,” she said.

“Don't worry about me,” I grinned. “I've taken care of myself for a long time now. You just take it easy, and leave everything to me.”

I have to laugh now, when I think of my swell-headedness. Leave everything to me! I thought I was good. I wouldn't have thought so, if I had known what kind of a bird this Borchard was.

DOWNSTAIRS in the lobby, I looked around for him. He wasn't there. I started for the smoking room, thinking maybe he had gone down there, when suddenly somebody tapped me on the shoulder, and a cool voice with a hint of a nasty laugh in it asked, “Were you seeking me, sir?”

I swung around and looked into the long, gaunt face of the man named Borchard. He was very tall—as tall as I am, and that's saying a good deal, because I'm five feet, eleven myself. And he certainly was one to give you the creeps. If you looked at him, you couldn't help feeling sort of scared. His skin seemed to be stretched on his head as if it had been taken off at some time and shrunk, and then put back on. It was of a pale, white, sickening color—like the color of death. But the man had poise, power. You could see it in his eyes, in his whole bearing.

His face twisted into a mean sort of smile that I didn't like at all. I had a feeling suddenly that this guy had lived for ages and ages; that he would go on living forever, as long as evil lived in the world.

He said to me, “I knew, of course, that you would come looking for me. I wanted to meet you. I have a proposition for you.”

I sort of gulped, and put on a bold front. “Go ahead, mister, but talk quick. I got plenty to tell you.”

“There is no need to talk quick. There is no need for hurry, my friend. We have ages and ages before us.” Borchard put his hand on my arm, and I winced, surprised. Because his grip was like steel. “But I forget,” he went on, “that to you, time is fleeting. I will not keep you long. In brief, my proposition is this—you are receiving one hundred dollars per day plus expenses to act as bodyguard to Miss Seymour. You are a private detective, and you are interested in making money. Say you are employed for ten days. That will be a thousand dollars plus expenses. All right, I will give you a cash sum of five thousand dollars. You will notify Miss Seymour's father that you can no longer continue on the job.”

I started to laugh, but stopped quick, when I saw those eyes of his boring into me. He had talked with the assurance of one whose word is law. Now he went on in the same vein. “When you return to your hotel, you will find the money in an envelope in the top bureau drawer of your dresser. Take it, and live in peace, my friend. Otherwise, you will learn what—terror is!”

Well, I'm no saint, and five grand is five grand—especially when turning it down means bucking up against a guy like this Borchard. But I'm a pretty stubborn sort of egg, and in spite of what people say about me, I have principles of my own. Also, I remembered the beautiful curve of Anne Seymour's throat.

So I said, “Nix. Your proposition is rejected. Now listen to what I have to say.”

Borchard had been holding on to my arm all this time. Now he let go, and bowed, smiling ironically.

“I know what you have to say, Mr. Manton. You wish to tell me that you are a very honest, capable and efficient private detective; that if I do not leave Miss Seymour alone, you will break my neck, or do me other serious physical injury. I understand all that, and I wish you a very good night.”

With that, he bowed again, and turned away, walked out into the lobby of the theatre.

For a minute you could have knocked me over with a feather. He had taken the words out of my mouth, stolen my thunder. What was I going to do—sock him in the jaw right there in the crowded theatre? That wouldn't have helped any. I would only have gotten myself into a jam, and left him free to work on the girl. I began to figure that I would be earning my hundred bucks a day in the near future.

The bell rang for the end of the intermission, and I started across toward the box. I looked up in that direction, and stopped short with a cold sensation in the pit of my stomach.

Anne Seymour wasn't up in the box. She should be visible from here, but she wasn't. The box was empty.

I guess it was instinct that made me swing out through the doors into the lobby. And there I saw it.

If I hadn't seen it, I wouldn't have believed it. There was a swell looking, maroon-colored limousine drawn up at the curb, chauffeured by a huge negro in a uniform that matched the color of the car.

The man, Borchard, was stepping into the car just as I caught sight of it. Another negro, who had been holding the door open, slammed it shut and swept around into the front seat beside the driver. The limousine got into motion.

But the thing that made me jump after it headlong, pushing a couple of bewildered theatre patrons out of my way without any consideration, was the glimpse I had caught of the white, proudly tilted face of Anne Seymour—sitting quietly inside that car as if she belonged there!

The car was already moving when I got out to the curb. I sprinted, came up alongside it. The windows were closed. I put my hand on the handle of the door, twisted it, but it didn't open. It was locked.

I yelled, “Miss Seymour! Miss Seymour!” But she didn't even seem to hear me.

Borchard was sitting next to the window, and I started to pound at it with my fist. The glass was shatter-proof. Borchard didn't even turn to look at me. He merely leaned over and whispered a few words to Anne Seymour. She finally turned her head, gazed at me impersonally, as if she had never seen me before, and then looked away again and stared straight ahead.

Suddenly the car gathered speed, leaped away, and the handle was torn out of my grip. I stood there in the middle of the gutter, panting, and I must have looked like one awful sap.

I STARTED to curse out loud, and then I realized that that wouldn't do any good. There was a cab across the street, and the driver was sitting there and looking at me as if I was pulling some sort of freak advertising stunt.

I sprinted across, swung inside the cab, and yelled, “Follow that limousine, guy. Twenty bucks if you don't lose it!”

I needn't have promised him the twenty dollars. The limousine made no effort at all to lose us, though Borchard must have known that I was after him. On the contrary, they seemed to slow up accommodatingly so as not to get too far away from us.

A left turn, then five blocks west through the night toward the express highway; here the speed of the limousine increased so I figured we were making fifty or sixty miles an hour.

The express highway ended, merged into Riverside Drive. The pace slackened, there were halts for red lights, and I was burning up, trying to figure what to do. I could have cut them off and had a showdown. But I remembered the way Anne Seymour had sat there in the car, not making any effort to get away, as if she wanted to be there. Borchard would probably have me arrested for disorderly conduct if I tried to start anything. The only thing was to keep on their tail, and see where they went.

At the northern extremity of the Drive, the limousine swung around in a wide curve and entered Van Cortlandt Park. Through the park we followed them slowly, then up through Yonkers and into a quiet, dark section of Westchester along dimly lit roads where there were very few houses.

And then suddenly the limousine spurted ahead, and we lost them. My driver slowed up alongside the mouth of a road that led away at right angles from the one that we were on. He turned around and said to me, “They must have swung in here, boss. They ain't up ahead.”

“Go ahead then,” I told him. “Keep after them!”

The driver shook his head. “Not a chance, boss. This thing looks phony to me. I got my own troubles, and I don't want no part of other people's. This here neighborhood is dead and God-forsaken; there could be a dozen murders happen up here, and nobody would know about them.”

“Where are we?” I asked him.

He pointed to the side road. “That there path leads up to an old cemetery that ain't been used in thirty years. The people up around here keep away from it at night. And this is as far as I go, mister.”

I shrugged, got out and handed him his twenty dollars. There was no use arguing about it.

“All right,” I said to him. “As long as you're afraid to go any further, you can wait here. I might be going back.”

He didn't say whether he'd wait or not. I left him there and worked my way along that path, guided at first by the headlights of the cab. Then there was a sharp curve, and I lost the benefit of the lights. I went along slowly, carefully, feeling my way. Ahead, there was impenetrable darkness.

Back at the road I caught the sound of a taxicab's motor racing, heard the clash of gears. The driver wasn't waiting, and I didn't blame him much.

I was in evening clothes, and I had no gun. Miss Seymour had been rushing me around like mad for the last couple of days, from parties to theatres and back again to parties, so that I'd been a little dizzy—and in changing to the tux that evening, I'd clean forgotten to take the little twenty-two that I usually lugged around with evening clothes.

I swung around another curve and saw a white wall ahead. It was a cemetery wall all right, and the gate was open. Inside, there was no sound, no hint of motion or life.

There was no other place that the limousine could have gone, so I worked my way in among the white stones which rose stark and bleak all around me. You will probably laugh at me when I tell you that I had worked up a nice little sweat by this time, and that it wasn't because of any physical exertion. I was just a little bit scared. And if you think I'm a sissy or anything, you are hereby invited to go up to that cemetery without having met a guy like Borchard in advance, and wander around in there for a half hour. I'll give you the address any time you ask for it.

Well, I guess I wandered around through that spooky place for about fifteen minutes before I found the limousine. It was standing in front of a faded, granite mausoleum, with the lights out. It must have been a couple of hundred years old; probably one of those crypts where they put whole generations of some family that was probably extinct by this time. The name, which had been carved in the stone above the doorway, was indistinguishable in the dark.

But one thing I saw that didn't make me feel much better. It was the wrought iron handle on the door. It had been fashioned into the likeness of the head of a snake!

I suppose ordinarily I wouldn't have noticed it, but all my senses were keyed up now, extremely acute.

Everything was quiet now, except for the rustling of leaves falling in the pathway from the overhanging trees. They stirred and seemed to whisper, to cackle hoarsely.

I took a peek in the limousine, saw that it was empty. Then I swung around to the door of the mausoleum, grabbed hold of that disgusting looking snake head, and swung the door open.

THE interior of the vault was in absolute darkness. And I knew that I was in the right place. Because, though there was no hint of life, neither was there any hint of death. You know what I mean—that musty smell, which is peculiar to vaults of the dead, was lacking here. This place had been opened recently. Fresh air had entered here earlier in the night.

I left the door, stepped inside cautiously, and groped around.

I felt a wall at my right, started to follow it like a blind man, touching it with my right hand while I kept my left hand extended in front of me in case I should meet somebody or something in the dark.

And suddenly I stopped still. I had the chilling knowledge that there was someone else in the vault with me. It was nothing I saw, nothing I heard; just that strange feeling that you get sometimes.

And almost at the same minute my outstretched hand touched a living being; I saw two eyes staring at me—right in front of me. I slammed out at those eyes with my right fist, and felt the crunch of bone under my knuckles, heard a gasp, and a grunt of rage.

Fingers reached out and gripped my shoulder, a fetid breath brushed my cheek. I slammed out again, this time a little lower, hoping to find a chin. And I guess I did, because the grip on my shoulder was suddenly relaxed.

But it was my unlucky night. Because from the left a flashlight suddenly clicked on, glared in my face. I started to swing toward the light, but something crashed against the side of my head.

That was an awful sock, and for a minute I staggered, weaving dizzily on my feet. And that was the minute that licked me. Because two massive arms gripped me from behind, twisted my hands in back of me, and held me helpless like a baby.

I'm no weakling, and I've been able to put up a pretty good fight in the past, even when I was groggy. But I made no headway at all against whoever it was that had this grip on me.

My head started to swim from that blow. I could feel the left side of my face wet where the blood trickled down from the split in my scalp. It had been a harder sock than I thought it was. I kept my senses all right, but I was kind of woozy, I guess for a few minutes the only thing that kept me on, my feet was this guy that was holding on to me.

As if in a daze, I was aware of figures passing in the darkness, of whispered orders, and shuffling feet.

I was suddenly lifted up in the air by the man who held me, carried a few steps and then lowered.

The guy let go of me, and I dropped—but not just a foot or two to the floor. I had been dropped through some sort of trap door, and I traveled about a dozen feet before I landed with a jar that sent the breath whistling out of my body.

Above me I could see the opening through which I had come. And even as I watched, it disappeared; a slab of stone had been shifted into place up there.

I rested on my back, breathing hard, trying to regain my wind. It was absolutely black here, but I had an idea that something was moving around—there was a kind of gliding, scraping sound not far away.

I got to one elbow, tried to stare through the darkness. And I caught a whiff of something—a noxious sort of stench. This was something I could recognize; it was snake stench. Some place around here there was a snake.

Once more I caught that slithering, scraping sound.

I put out my hand and touched some sort of wire mesh screen. There was a swift, vicious, hissing noise, and something struck that screen close to my hand.

I jerked my fingers away, took out a book of matches, and shakily lit one. I raised it up high, and I can tell you that that light was doing a waltz. My hand was certainly not steady. By the flare of the match, I saw what I was up against. Right beside me was a sort of wire mesh cage, about five feet square and as many feet high. Inside that cage were two tiny pin points of eyes that squinted redly at me. Those eyes belonged to a squirming, wriggling reptile that was about twice as long as I. And somebody must have figured that it wasn't horrid looking enough, because they had painted, its entire length in red with, some ghastly design that seemed to move and have life as the snake wriggled.

The match flickered and went out. I lit another one, raised it high and took a look all around. This wasn't just some sort of pit under the mausoleum. I was on the gallery of a vast, cleverly constructed chamber. If I had been unwise enough to take four steps forward, I would have fallen from the ledge to the floor of the chamber below; and that would have been a drop of about thirty feet. This place must have been cut into the ground away back when the mausoleum was built—and that had not been done haphazardly, for the walls, floor and ceiling were of brick, solidly constructed. I began to wish that I was in some peaceful business like the Chaco War.

I started to inch away from the cage next to me, feeling in the darkness for some way to get off the gallery. My head was throbbing now, and I started to have burning pains flashing across my eyes. My hair was matted at the spot where I had been hit, and it was cloyed with blood. I put my head down on the brick floor of the gallery, which felt nice and cool, and I lay there quietly for a few minutes to let the cold stone draw the fever out of the wound.

In back of me, the scraping at the wire mesh of the cage seemed to grow louder. I guess the snake was kind of sore at me for not coming inside and providing him with a meal.

AND then all of a sudden, things began to happen. There was a glare of light from the floor of the chamber below, and I caught the sound of measured footsteps. I crawled to the edge of the ledge, raised my head and stared over at the singular procession that was marching in through a door at the far end of the chamber below.

Two negresses, immensely fat, dressed in long, red flowing robes, came in first. Each of them carried a tall taper whose flame flickered, casting weird shadows on the wall.

Behind them came a man who was dressed all in black, with a peaked cowl over his head, and a flowing robe that hid his feet. Out of the cowl peered a gaunt face. It was Borchard's face all right, but there was something different about him. He looked like a high priest—reminded me somehow of strange, outlandish African rites.

The two negresses crossed to a sort of dais in the middle of the floor, and set their tapers in two tall sconces on either side of the raised platform.

Then they turned around and faced toward my ledge, standing immovable.

Borchard marched solemnly across the room until he stood directly below the ledge. Then he raised his face toward the cage in which the serpent lay, and began to recite a kind of invocation in a voice that gradually grew louder and louder until he was talking so fast that the words seemed to trip over each other. He was using some sort of strange, outlandish language that I didn't recognize.

By the light of the flaring tapers, I could see the snake in his cage, and he must have been used to this sort of ceremony, for he rested his head against the wire mesh and seemed to be listening.

Suddenly Borchard's voice dropped to a whisper, and then became silent. As if it had been a signal, one of the two negresses produced a flute from under her robe, put it to her lips and started to play the weirdest, creepiest kind of tune I'd ever heard. The tune was so swift that my ear could scarcely follow it. The snake responded to that music by wriggling its gruesome, sinuous length faster and faster. The hideous red marks with which it was painted made me dizzy to watch them.

Borchard reached over and pulled a chain down below there, and the cage began to move slowly. I noted for the first time that there was a kind of pulley fitted to the top of the cage, and that the pulley rode on a cable extending from the ledge down to the platform near which the negresses stood. Slowly the cage descended via the cable, until it came to rest upon the dais on the floor below.

The negress continued to play that damned flute of hers even faster, and Borchard strode across the room and unlocked a small door in the cage. The serpent was writhing frenziedly now, in tune with the music, but made no attempt to slip out of its prison.

Borchard turned and faced the doorway through which he had entered the room, and stood in an attitude of expectancy. I looked in that direction, too, and started to feel a cold sweat all over me, forgot all about the pain in my head.

Anne Seymour had come into the room.

But let me tell you how. She was crawling.

Like the two negresses, she was wearing a long red gown. She wriggled across the room slowly, sinuously, as if she were some sort of reptilian being, keeping time to the wild strains of the flute.

Her face was changed, somehow distorted. Of course, she was under the influence of some sort of drug. And she was crawling straight toward that lividly painted serpent in the cage.

And then I found out what this dizzy business was all about. Because I happened to turn my head, and there, right near me on the ledge, were these two tall negroes—still in the livery which they had worn while driving the limousine. I had been lying so quiet, with my head on the stone, that I guess they thought I was still unconscious. The face of one of them, I noticed with satisfaction, was kind of marked up. I guess that was the one that I had slammed into in the dark up in the vault.

This one was setting up a camera on a tripod, focusing it on the scene below. The other was watching him and holding a large flash-bulb overhead.

Now I got the whole picture. And was it a laugh? It was not!

I turned around, grabbed a quick look down below. Anne Seymour had crossed the floor, had reached the top step of the dais. She was resting on her elbows, so that her head was on a level with that of the serpent. Slowly, those long, powerful coils oozed out of the cage. The snake reared its ugly little head high, arched itself over her. The flute was still playing.

And it was at that minute that the flash- bulb went off.

The two negroes had taken the picture of Anne Seymour and the snake.

A lot of things happened at once. Anne Seymour screamed—screamed loud and sharp and clear. It was a scream of mortal fear and agony; and though it didn't sound so nice, it indicated at least that she had come back to her senses. Then I made a flying leap at that camera from my position on the ledge, sent it smashing over the side to crash into pieces on the floor below. The plate of that picture would never be developed. And the third thing that happened was that the flute stopped its infernal music. Why the negress stopped playing, I'll never be able to figure out for sure, but I think she'd seen me lunging for the camera up there on the ledge; or else Anne's scream had made her quit.

Then all of a sudden those two negroes were on me like a ton of bricks. I wasn't dizzy any more now. I was just mad—good and mad. And I used a couple of stunts on them that I would have hesitated to use under ordinary circumstances. In any boxing or wrestling ring in the country they would have been declared fouls, and the guy who pulled them would have been forever barred and black-listed.

Well, I confess I used them. And though I got a bad cut under my left eye, and a long knife gash in my side from one of those two boys, I had them on the floor, dead to the world inside of what must have been about sixty seconds. One of them was altogether out, having cracked his head against the stone ledge when he fell, and the other one was just doubled over, holding onto his middle and moaning with agony.

I didn't wait to offer them any consolation, but turned and raced along to the end of the ledge. I had noticed a flight of stone steps that led down to the chamber below.

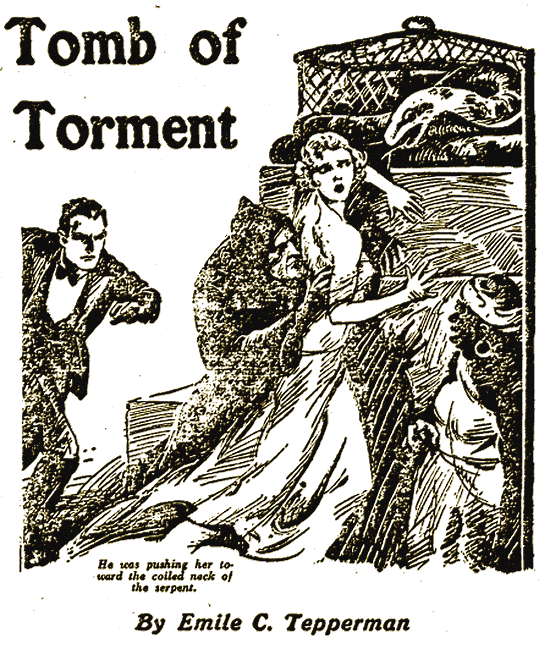

I GOT down there in time to see Borchard standing at the foot of the dais with a vicious, hateful look on his face, and pushing Anne Seymour toward the cage. She was trying to get away from there, trying frantically, striving to get away from the coiled neck of the serpent which was arched above her. And Borchard wouldn't let her.

Borchard was standing as far away from the damned snake as he could, and he was holding Anne Seymour at arm's length, gripping her shoulder with those powerful fingers of his. He was afraid of that snake, I could see, for the reptile was no longer under the spell of the flute's music. Borchard hadn't intended letting the thing go so far, of course, but now that the snake was really after some supper, he figured the girl would make a better tidbit than himself.

He must surely have heard the camera smash, must have heard the sounds of the scrap I had up there on the ledge with the two negroes; but he had his hands full trying to sell the snake on the idea that the girl would make a tastier dish than himself.

Well, anyway, it's funny how one million thoughts and pictures will fill your mind in the space of about thirty seconds, because I think that's all it took for the whole tableau there by the dais to register with me.

And then I was across that floor in nothing flat, sprinting the way I had done many years past when I hung up a record for the hundred-yard dash in the Marine Corps—only I did it faster this time.

I had to stop short, or else I would have slammed into Borchard, and he would have slammed into Anne, pushing her right up against the serpent.

So I slid the last five or six feet, reached across his shoulder, shoving him sideways, and yanked Anne out from under that serpent.

Anne went sprawling on the floor, and Borchard came for me, his thin, parchment- like lips pulled back from his snarling teeth, and his hands raised like two claws. We tangled, and his hands went for my throat. I could see that snake's pin-point eyes watching us as Borchard dragged me to the floor, slammed himself down on top of me, driving the breath out of my body, and clamped those powerful fingers of his around my throat. His breath was in my face, and it smelled foul, fetid, like the stench of death.

I squirmed around, trying to break that grip, but it was no use. His hands were powerful.

I began to gasp for air. My head was getting dizzy again. I slammed out with my fist, kicked him in the shins, but he held on.

His face was close to mine, and he snarled, “Damn you—damn you! You have robbed me of a fortune!”

I couldn't talk any more, and I felt myself getting kind of weak. I wanted to yell out to Anne Seymour to get the devil out of there, but I couldn't make any sounds come out of my throat. Things began to get spotty in front of my eyes. I figured I was about through.

And then, without warning, Borchard's grip on my throat relaxed. He shrieked—again and again—while I drew great gulps of air into my lungs. I rolled away weakly, groped to my feet. And I stood there, staring stupidly, uncomprehendingly, at the struggling, threshing body of Borchard, about which was wound coil upon coil of the sinuous body of the great snake. The serpent had picked him for its supper. And I wasn't going to do anything about it except to hope that it choked on him.

A hand clutched at my sleeve, and I looked down to see Anne Seymour. She was sane now, scared out of her drugged trance.

“Take me away!” she gasped. She took one look at Borchard, just as some of his bones started to crunch. She closed her eyes and swayed, would have fallen if I hadn't caught her.

I picked her up, started for the staircase leading up to the ledge. Borchard kept on screaming behind us, but his screams were getting weaker and weaker.

WE weren't out of the woods yet, by any means. I found out that the two fat negresses could do something else besides play the flute. The last glimpse I'd gotten of them was when Borchard had me down; I had seen them standing, each at her corner of the dais, rooted to their places with fear of the serpent, afraid to come any closer than they were.

Now, as I made for the staircase, I suddenly heard the wildest, most frenzied sort of shrieking that yours truly has ever had the privilege—if you want to call it that—of listening to. I took one quick, startled look behind, and, sure enough, it was my flute playing pal and her girl friend.

They were coming after us.

Their hair was streaming out behind them as they ran; they were drooling at the mouth and shrieking at the same time; and their eyes were wide, mad, rimmed with red. They had long nails, and their hands, flourishing knives, were sort of reaching out after me as if they wanted to rip me apart and take me home for souvenirs. They looked like the pictures I had seen of those mythological dames who are known as “The Furies.”

Well, believe me, I put on a burst of speed. If I had been clocked then, I bet I would have broken not only the record for the Marine Corps, but the world record. The only thing that saved us from those two dames with the long nails and knives was the fact that they were fat, and waddled.

I beat them to the stone staircase, swung Anne Seymour over my shoulder, and raced up.

On the ledge I stumbled over one of the unconscious blacks, almost fell, but recovered my balance by a miracle. The stone slab was in place in the opening above.

I set Anne on her feet, let her lean against the wall, and climbed the few steps of the short wooden ladder that led up to it. I pushed hard with my shoulder, the slab gave, and I had it opened in a moment.

Those two fat negresses were waddling up the stairs, still screaming, but no sound came from Borchard. And I didn't look over there to see how he was getting along.

I reached down, gave Anne a hand, and fairly dragged her up the ladder into the vault.

The two negresses were paddling across along the ledge now, and I literally slammed the slab down in their faces. We were up in the darkness of the mausoleum now. I turned, found Anne Seymour's hand, and raced with her out into the night.

We didn't stop till we got out onto the highway.

Behind us we were able to see the two shadowy figures of the negresses, still coming after us.

I had no desire to tangle with them, and I looked up and down desperately for some sort of vehicle.

And there it came.

My taxi driver!

And out of the cab leaped a couple of State policemen.

The driver got out, explained sheepishly, “This business looked phony, mister, so I went back and got a couple of cops.”

“Boy,” I exclaimed, “you're Santa Claus!”

I said to the two cops, “We'll have company here in a minute—two negresses. Grab 'em.”

I couldn't be of any assistance to them, because Anne Seymour was leaning heavily against me, and I had to hold her up.

I fairly carried her into the taxicab, sat down alongside her. We watched while the two State policemen subdued the negresses.

“What—what did Borchard want with me?” Anne Seymour asked. She was still trembling. “I—hardly seem to remember what happened.”

“It was just a blackmail racket,” I explained to her. “He had a couple of guys there ready to take a picture of you as a snake worshipper, and then he would hold your old man up for plenty of jack—make him buy the picture back. It's an old racket: I've been up against these cults before; but I never saw it worked in just this way.”

“But—but what was I doing there, with that snake?” She shuddered as she asked.

“Just forget about it, kid; just forget about it,” I told her. “It's, all over now.”

I wasn't going to tell her what she had looked like to me as I saw her from up there on the ledge. Better to let it stay in the limbo of her subconscious.

The only thing I regretted was that my hundred dollar a day job was over. I consoled myself with the thought that maybe old man Seymour would come across with a bonus.

And he did. And it was a fat one.

But I didn't tell the old man about a little secret that I'm going to let you in on now—provided you promise to keep it to yourself. This is it: Borchard might have been a pretty screwy kind of blackmail artist; but he was as good as his word, and I guess he had been pretty sure of himself.

Because when I got back to my hotel, I took a chance and looked in the top drawer of my dresser. And sure enough, there was a neat little package. When I opened it, I found that it contained fifty brand new one hundred dollar bills—just as he had promised!