RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

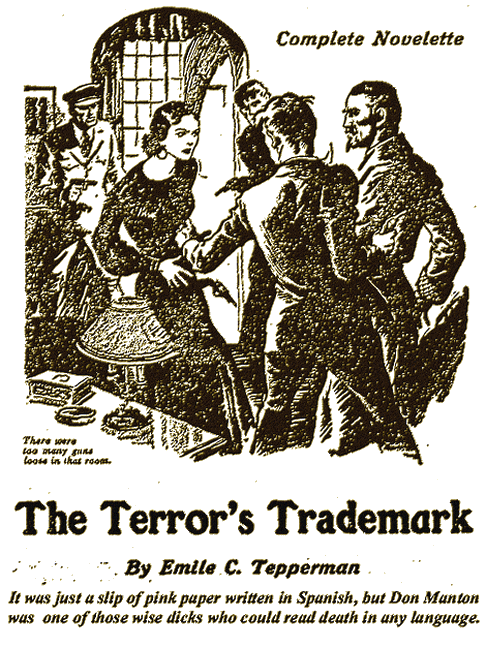

It was just a slip of pink paper written in Spanish, but Don Manton was one of those wise dicks who could read death in any language.

Headpiece from "Secret Agent 'X'"

MY full name, which I now reveal publicly for the first time, is Donald Faversham Manton—not such a hot name for a case-hardened private dick like me. But let it ride. I've struggled through thirty-two years with the name. Some people call me Don Manton; a few call me Don—very few, because I'm choosey about my friends. And a great many people have called me other things, ranging from short, sharp, ugly four-letter words to longer, just-as-ugly, seven, ten and eleven-letter words.

But nobody has ever called me a sap—which this Spanish dame in the bank must have figured me for.

The way it started was like this. I was down in the vaults of the Inter-City Trust, for the purpose of getting my life insurance policies out so as to make a loan on them. Business had not been so swell of late, what with a couple of my star financier clients getting sent to jail for this and that; so I needed a little ready cash for operating expenses until I could dig up new customers.

Well, I had taken the safe-deposit box into one of those cute cubbyholes they provide for so-called privacy. It had no door, and I could see out into the corridor, across into the cubbyhole opposite. There was a gent in there with a trim moustache and a carefully clipped Vandyke. He was pawing through his box, apparently looking for some certain paper, and he looked plenty nervous and excited.

I'm always interested in people who are nervous and excited—like a bloodhound, scenting business. So I kind of kept my eye on him while I got my own stuff. I took out the policies I needed, and closed the box. As I left my cubbyhole to return it to its niche, I saw this bearded gent snatch up a small strip of pink paper and examine it avidly, sort of muttering to himself as he did so.

I had to go down the length of the corridor to get to the grilled door where you return the boxes when you're through with them. And on the way back I saw this gent coming out of his own cubbyhole, bringing his box back, too. It was a big box—one of the thirty-dollar-a-year ones—and was clumsy to carry. He had it under his arm, and was evidently laboring under some great agitation.

Well, there was nothing remarkable about a middle-aged guy carrying a safe- deposit box back to the vault—even if he was a little excited.

It was the thing that happened next that pulled me into the whole nasty nightmare.

Out of the cubbyhole next to the one I had been in, came this Spanish dame that I mentioned before. She must have been watching him, because she stepped out at the same minute that he did, and naturally, the two of them bumped in the narrow corridor.

The dame lost her balance, and stumbled, against him, grabbing his shoulder with her black-gloved hand. The old gent had a hard time of it for a second, holding on to the box and trying to support the dame. But they finally got themselves straightened out, and the dame said, in a sweet, soft voice, "A thousand pardons, señor. I am so clum-zee!"

The old gent swept off his hat and made a nifty bow. "But no, señorita. The fault is of my own boorish awkwardness!"

I could see the old gink perking up. And this dame, I can vouch, was something to perk up for. She was in her middle twenties, not over five feet four. She had a white, smooth, creamy skin. And her hair, which was coiled up in back under her wide-brimmed hat, was so black and soft-looking it made your fingers itch to run through it, sort of caressing like. Her face was a long, delicate oval under that hat, and when she smiled she was the most gorgeous thing a man could want to lay his eyes on.

She smiled at him, nodded, and passed on. And the old gent sighed deeply as if regretting his lost youth, and came down the corridor past me, with his box. He was so entranced, he didn't even notice me.

As for me, I went after the dame fast and furious.

Why?

Because I had noticed what the dame did when she stumbled against him. Her left hand had slipped into his right hand coat pocket, and came out; clutching that pink slip of paper!

Now there were a number of things I could have done at that minute. I could have told the old man that she had his paper; I could have shouted after her to come back and fork over; or, I could have gone after her the way I did. Maybe the reason for that was her looks. I'll leave it open.

Well, I got to the stairs that led up to the street level, and she was at the top, walking calmly, as if she hadn't done a thing in the world to be worried about. If I had been endowed with more of a romantic strain and less experience. I might have been tempted to believe that my eyes had deceived me. But there were no two ways about it—I had seen her lift the paper from his pocket, and what's more, I knew where she had put it—she had tucked it into the right-hand cuff of the coat of her trimly tailored navy blue suit.

And there she was, walking out of the bank as cool as a lady cucumber.

I am seventy-one and a half inches tall, and my legs are plenty long. So I took those stairs four at a time, and got to the top just as she was stepping out on the sidewalk, nodding to the doorman as if she was the queen of China or something.

She turned to the left, and I could see her walking down the street along the bank's plate glass window. I knew I had her then, so I slowed up a little and took it easy on the way out. These days, what with hold-ups and things, it doesn't do to run out of a bank—there are too many nervous guards with guns stuck in the holsters of their cute Sam Browne belts; and a nervous guard with a gun is a dangerous combination.

OUT in the street I speeded up a little, and caught up to her as she was turning the corner. I put a hand on her shoulder and spun her around. She flashed me a look as if I was dirt under her feet, and threw a disgusted glance at the paw I had on her. Boy, she was a swell actress. She had all the appearance of outraged dignity and refinement, though she must have known damn well that she was in a spot.

I beamed at her, and said, "Hello there, Gertie! Gee, it's swell to see a girl from the old home town!" And with that I grabbed hold of her hand and started pumping it up and down.

She tried to wrench her hand away, saying, "I do not know you, señor—do you not make a meestake?"

"No, sister," I told her. "This is no mistake." And I yanked the pink slip out of her cuff. "You were just about nine seconds too slow. You should practice up. I can give you the address of a good pickpocket school, if you want it."

She started to claw for the paper, but stopped when she saw we were attracting attention. She said low and earnestly, "You will return to me at once my paper, or I call the policeman upon the corner!"

I grinned at her. "Okay, sister. Then we'll all go back to the vault and ask the old gent there if he's lost anything." I dragged at her arm. "Let's do that anyway."

"No. Wait." She held back, looking me over then dropped her eyes to the slip of paper which I was holding onto now. "Perhaps, señor, I can explain."

I grunted. "Go ahead, girlie. I wish you could."

"This paper," she said, "ees to me of great import-ance. Eet belongs to me. That man in the vault—" she shuddered prettily, "ees a what-you-call, Shy-lock, he have loaned to my brother much money, and now he weesh to blackmail heem." She stopped, asked eagerly, "You read Spanish perhaps, señor?"

I shook my head.

She went on swiftly, apparently relieved. "That paper ees my brother's note. My brother have paid heem the money, but this Shy-lock, he refuse to return thee note. He demand more money, and more money." She shrugged prettily. "So I am force' to do this for my poor brother."

"Gee, lady," I said, "I'm sorry for you." I raised the paper and glanced at it.

At this point I must stop and be ashamed to relate that I had lied to the lady. I do understand Spanish, as well as a few more lingoes that I picked up in the course of a four-year stretch in the marines a good while back.

And the first few words were, "La vida es mala—," which, in good American, means, "Life is an evil thing—"

Well, no matter how gullible a guy may be, he is sure to know that that is not the way to begin a note or any other document which promises to pay a sum of money at a future date.

I didn't get a chance to read any more of it, because she started working on me again, right away.

"You see, señor, what terreeble things a girl is sometimes force' to do! I blush with shame. But what would you have—a brother is a brother—"

"Very true, lady," I told her. "And a cat is a cat, and picking a pocket is picking a pocket. So let's go back and talk to this old gent, and see does he want to prefer a charge against you." I shoved the slip of paper in my vest pocket, and bowed, still holding on to her hand. "Or, if you prefer it, shall I take it back to him myself, and tell him I picked it up on the floor by mistake. I'd hate to see a pretty girl like you in a jam with cops and courts and so forth."

Why did I do that?

Well, I always was a softy for pretty dames, even when I knew they were putting one over on me. It's a weakness, I admit, but at least I can say that I never let it go too far. Plenty of other guys have the same weakness—in fact, I would say that ninety per cent of the male population under sixty suffer from it more or less, so why not me? It's about the only thing where I'm a softy, and I like to indulge it. So what are you going to do about it?

This time though, I was sorry I had said it. Because I saw a venomous look come into that dame's eyes that changed her whole appearance. For a half a minute she wasn't beautiful any more. Then that look went out of her eyes, and she said softly, "I see that you are more clever than you seem, señor. You will not give me the paper?"

I shook my head. "You ought to be glad I'm letting you go."

"You are generous, señor," she said mockingly. "But not generous enough. Perhaps next time—"

And she turned coolly, and walked down the street. I watched her, kind of puzzled, until her trim figure disappeared in the lunch hour throng. I didn't like that last crack of hers; it seemed, now, to contain a veiled threat.

I shrugged, and turned back toward the bank. The whole thing was more or less goofy. I wanted to catch the old gent with the Vandyke before he went away. Somehow I had a funny feeling as if this was only the beginning of something. I've had those feelings before—and there's always been trouble.

DOWNSTAIRS in the bank vaults, I looked around for the old gent, but he was not in sight. I walked down the corridor, looking in all the cubbyholes, and finally asked the guard at the vault door about him.

"He went out just after you did. Mr. Manton. He was all through with his box."

I took out a cigar which had been given to me gratis the week before, and handed it over. "Maybe," I asked, "you could tell me his name and address?"

The guard took the cigar, smelled it, rolled it in his fingers, and put it in his pocket. Then he gave me a dirty look. "I'll tell you, Mr. Manton—jobs is scarce, an' I can buy a cigar for a nickel. You know I ain't supposed to do anything like this. Thanks for the smoke, but—"

Well, I had thrown out more than one sawbuck in the past which had been charged up to advertising, goodwill, et cetera, so I said to myself, "What the hell, this may turn out to be business," and I peeled a ten-spot off my very thin roll, and slipped it to him.

"You can't buy that for a nickel," I told him. He grinned all over. "You're damn tootin' I can't, Mr. Manton." He stuck the bill in his vest pocket, sighed, then shrugged. "On twenty-two dollars a week they can't expect me to turn down a sawbuck."

He went inside to the big book they keep on the table, thumbed through the pages, and wrote a name and address, copying it from the book, on one of the bank's folders advertising the advantages of naming them the executors of your estate.

Then he came out and handed it to me. "He's Spanish, Mr. Manton. He's a gentleman, all right, but tight as hell. Used to be a big shot in Barcelona—I heard the vault manager say one day that he was police commissioner of Barcelona back in Spain."

I took the folder, and went upstairs. Outside, I took a look at it. The name the guard had written was, "Don Seguro Garcia, 14 Esplanade Terrace."

I went across the street to the drug store on the corner and consulted the phone book, but couldn't find any listing for Don Seguro. So I went in a booth and dialed information, asked for a phone at 14 Esplanade Terrace.

She said, "That is the Hotel Terranova, sir. The number is Fogarty 4- 8210."

I thanked her and hung up, dialed Fogarty 4-8210. I had heard of the Terranova. It was a small, exclusive, residential hotel that catered a lot to the Spanish aristocracy that had departed when King Alfonso abdicated.

When I got the number, I asked for Don Seguro Garcia. The clerk said, "Don Seguro has not yet returned, sir. He is expected in one hour."

I didn't leave my name, but said I'd call later, and hung up.

Just before pushing open the door of the booth to step out, I saw something that stopped me. I had a good view of the street through the drug sore window, and there at the curb was one of those long purple town cars that are supposed to cost about eight or ten grand; a wizened looking, olive-skinned chauffeur sat at the wheel, looking straight ahead of him. And on the sidewalk, just beside the car, stood a man in morning clothes, who would take your attention anywhere.

He was over sixty, that was a cinch—and maybe over eighty, for all you could tell. His face was absolutely white and expressionless, and wax-like. No one would blame you much if you mistook it for the face of a walking mummy—except for the eyes. They were black and sharp, glittering; and they peered through the window of the drug store in the direction of my booth.

Ordinarily I wouldn't have paid any more attention to this bird than to wish I didn't have to meet him some dark night in a spooky house. Only—I got a glimpse of the occupants of the car, and that was a different story. There was another man in there who kept his face in the shadow, being on the far side. But on the near side, looking out through the glass, was the pretty face of the Spanish dame from whom I'd taken the pink slip of paper just a while ago.

That put a different complexion on things. I was sure they could see me, because there was a little bulb in the booth that lit when you closed the door.

I PUSHED the door half open until the light went out, and went through the motions of pretending to put another nickel in the phone slot. What I did in reality was to hold the receiver to my ear while I dug out that slip of paper and held it up in the palm of my hand so I could read it.

It started out the way I told you, and this was how the whole thing went:

"La vida es mala, pero toda queremos viviria!"

That was at the top, as a sort of heading. I recognized it as an old Spanish proverb, which means something like this: "Life is evil, but all men cling to it!"

Well, I had no argument with that, because you can't argue with proverbs. And I had seen the truth of that particular sentiment demonstrated too often. It was what came next that revealed that there was something extremely odoriferous in Denmark. It read like this:

"por viejo que eseas, guieres vivir; lastima que dentro de viente dias tendras que morir! "

Now the gist of that last was as follows: "Though you are an old man, you still are anxious to live; what a pity that you must die within twenty days!"

Now that is a big mouthful for anybody to swallow. The note was written in a crabbed sort of handwriting, and bore no signature. There was no doubt that it was valuable to some people for some reason, aside from the nasty prophecy it contained. In view of the efforts that dame had made to get her dainty hands on it, it would not be assuming too much to anticipate that a strenuous attempt would be made to separate me from it now.

So, not being an accommodating sort of cuss, I turned my back on the door of the booth, as if I was carrying on a heavy conversation into the phone. Then I lowered the receiver, and unscrewed the circular piece that fits on the end. I stuck that pink slip of paper on the inside of the cap, and screwed the whole thing back on the receiver. That piece of paper would stay there for a long time, provided it didn't interfere with the operation of the instrument. I had to take that chance.

Then I hung up, killing the dialtone that had been buzzing all the time that I was working with the receiver, and walked out of the booth into the store.

I saw the waxy-faced gentleman near the car, sort of tense, but I took my time. I stopped at the cigar counter, bought a pack of cigarettes, lit one in leisurely fashion at the counter lighter, and then strolled out. So far I was having some fun out of this business, even if I wasn't making any money. And I was interested in who had written that threatening note, why, and to whom. If it had been written to Don Seguro Garcia, why had he kept it in his safe deposit box, and why had he been so anxious to get it out today? Was today the twentieth day?

I could have thought of a lot more questions, but by this time I was out in the street, and the gentleman with the wax-white face had stepped away from the car and was bowing to me, though his sharp, black eyes never left my face. He spoke a little stiffly, but without a trace of accent.

"I trust you will pardon the intrusion, señor. Permit me to introduce myself—I am Julian Molina."

I didn't say anything. I was busy watching him and at the same time keeping an eye on the dame and the man inside the car. Also, I couldn't seem to get over the feeling that Mr. Molina was a walking corpse or something. That white, bloodless face of his could give you the creeps on the brightest day.

Mr. Molina was standing about three feet from me, and his voice, which was very low, just barely reached me. He said, "You are the famous detective, Donald Manton, are you not?"

I grinned at him. "I see you work fast, Mr. Molina. Did you get my name from the guard down in the bank vault?"

He shrugged, his face never changing expression. "That is beside the point, Mr. Manton. The point is, I find myself in need of the services of a private detective—at an extremely generous remuneration; shall we say—one thousand dollars?"

I blinked a couple of times. "This is so sudden, sir," I told him. "When did you discover you needed my services—when your girl friend told you about me?"

"That is immaterial, Mr. Manton. I invite you to come with me to my home. There, I shall be glad to pay you the sum I mentioned. And the service which I shall require of you is trivial—merely that you hand me a certain pink slip of paper upon which are written some Spanish words. Do you agree?"

Now, a thousand dollar fee for nothing would have been the height of my ambition at nine o'clock that morning. But at this minute I didn't feel that way—especially in view of the threat of death contained in that note. I like money as well as the next man, but I learned a long time ago that a thousand bucks acquired as easy as this might cost you ten times as much in the long run, in cash, trouble, and gray hairs. And murder, threatened or accomplished, is nothing to fool around with under any circumstances.

So I said, very courteous, "I am sorry, Mr. Molina, but I am afraid I cannot accept your kind invitation."

My idea was that I'd get in touch with Don Seguro Garcia first, and then, maybe, turn the note over to Sergeant MacGuire at headquarters, if I found I couldn't make an honest dollar out of it somehow. If there turned out to be no dough in this at all, I wasn't going to be in the position of having held out on the cops. I'd done that often enough, and incurred MacGuire's animosity by doing it—but that had been only when I could profit by it. I'd be sappy to get Mac's dander up by pulling something that didn't even net me a profit.

MR. MOLINA, however, had other ideas. He didn't crack a smile on his pallid face, but he gave a jerky little bow, and said with a faint trace of mockery, "You are mistaken, Mr. Manton—you are going to accept my invitation. Observe," he went on, "what the gentleman in my car is holding." He jerked his head toward the auto.

The guy who had been sitting next to the dame was now close up to the window, and I could see that he was holding a long-barreled revolver to which was attached a silencer. The muzzle was pointed at me.

Anybody who was passing would never have noticed that revolver, because it was inside the car, and in the gloom. But my eyes are keen, and besides, I'd been told to look. Even if I hadn't seen it, I could guess what it was. People were passing on the sidewalk, and I could have taken advantage of that to make a quick jump for Mr. Molina while somebody was between me and the car.

But the eyes of the man inside convinced me that he would shoot anyway. I'd only cause the death of some innocent person.

Molina seemed to read my thoughts. For he said, "Observe further, that at the first move you make, you will not only endanger your own life, but also the life of anyone who may be passing. You will surely be killed. The car will then depart slowly, while I remain here to inform the police that you were shot from a passing taxicab. It will be far wiser, my dear Mr. Manton, to enter my car and come with us."

Now I saw why he had stayed the three feet away from me. This bird, Molina, was no amateur—he knew all the tricks of the game. And I didn't need any more evidence for that than his face. If these people had been amateurs, I might have taken a chance with them on the theory that they'd lose their nerve at the last minute. But not Molina and Company—no sir.

So I gave him a thin grin. "You win round one, old boy. Let's go."

There was no trace of emotion or relief on his face as I stepped over to the car. He had been sure of himself.

The girl opened the door, and I got inside.

The man with the revolver pushed back in the seat to the far end, leaving room between me and the girl. He was a swarthy guy with a long face, and there was a little nick at the bottom of his chin. It's funny how you notice things like that when you're all keyed up.

He didn't talk, just motioned with the revolver toward the space between them.

I sat down, and Mr. Molina got in after me, put up one of the folding seats, and sat down facing us. He closed the door, and the car started. I hadn't watched closely, but I could have sworn that the chauffeur hadn't even turned his head all this time. But he knew just when to start.

The car rolled through the streets, made a left turn and headed uptown.

The man with the nick in his chin was at my left, and he held the revolver in his left hand, pointed at me, across his chest. He was giving me the once-over. So was the dame, I discovered, when I looked at her.

"Well, Gertie," I said, "it looks like you got substantial boy friends."

She lifted her chin haughtily, and stared ahead. Mr. Molina said gently, "The lady's name is not Gertie, Mr. Manton. She is Señorita Elvira da Luna." He addressed her, "Elvira, this is Mr. Manton. You have met before, of course, but you did not have the benefit of an introduction."

"Glad to know you, Elvira," I said. "How's the pocket-picking these days? And how's your poor brother—did he ever get that money paid to the old Shy- lock?"

She raised her shoulder at me, said to Molina, "Can not you silence him, oncle? He ees very eensolting!"

Medina's face didn't show an iota of what he was thinking. He said a little sharply, "Patience, Elvira! Soon our friend will be very silent—and for a long time!"

Elvira started to say something, but he gave her a nasty look, and she shut up quick. It didn't look as if it was healthy to argue with Uncle Moley; and from what he said, it didn't look as if the future was going to be very healthy for me—whether I argued or not.

Everybody was quiet for a while, and I looked out and saw that we were crossing the Queensboro Bridge. After a time we got out into a thinly populated part of Queens, and Molina said, "Now, if you don't mind—" he nodded at the man who sat at my left—"if you will proceed as planned, Eustachio—"

My instinct worked one split second too slow that time. I started to twist away, but I was too late. Something hard and solid came down and smacked me on the side of the head with awful force.

I started to say, "What the hell—" but that was all I could get out. My arms and legs felt like lead, there was a rumbling and roaring in my head, and I felt myself floating around in air like a disembodied soul. And then I didn't know a thing. I was out cold.

I DESERVED it, of course—had no excuses to offer to myself. A guy in my line of business shouldn't go horning into other people's troubles. What I should have done back there in the bank vault was to tell that old gink, Don Seguro Garcia, that the girl had picked his pocket, and let it go at that.

But I had to go and chase her. And now, where was I?

That was one I couldn't answer. It was a room, all right, because it had four walls. But it was so damned dark that I couldn't see anything else: I knew I was on the floor, and the side of my head was sticky where Eustachio had hit me. They hadn't tied me up, which was something.

I started to feel for my fountain pen flashlight, and I suddenly got the jitters. Because my hand encountered my own bare skin where my vest should have been. I explored further. Boy, you ought to have the feeling that I had at that moment. I was absolutely and indecently naked. Not a stitch of clothing on me!

A guy can be brave if he's facing odds with a gun in his hand; or even if he's facing death without a gun in his hand. But just try to keep a stiff upper lip if you should wake up some grisly morning or night—I couldn't tell which it was—in a dark room, with no clothes on, and you can't tell where you are. Swell feeling. Nit!

My next reaction was to get mad. I'd break the necks of the dirty so-and-so's who'd taken my clothes away. Imagine if it ever got around that Don Manton had been taken for the works by a couple of foreigners, and left without his clothes. I could just picture big, red-faced MacGuire giving me the razz the next time I showed my face in headquarters—and would that face be red!

The question was, would I ever get the chance to show my face in headquarters again—or anywhere else, for that matter, except out of the head-opening of a black casket in an undertaking parlor. The way it sized up was this—I knew too much to be safe for Mr. Molina or his charming niece while I was alive.

Cheered on by this last thought, I began to feel around in the dark in an effort to discover what kind of place this was, also, if there was a way out. I got to my feet, found a wall, and guided myself along it until I bumped into a solid piece of furniture.

It was a bed.

A bed meant that there would be sheets; and sheets meant only one thing to me—something to cover myself with. I reached out a hand, felt a nice, cold sheet, and yanked it off. It resisted a little, probably where it had been tucked under the mattress, but I heaved till it came free.

In the dark I wound the thing around me like a Roman toga, and tied the two ends at my right side. It wasn't very handy if I should find myself in a hurry or in a fight, but you can't imagine how many hundred per cent better I felt with the sheet covering me.

That is, I felt better for just about one half of a minute. And then I didn't feel better any more—I felt blood!

I've been around enough to be able to tell blood when I feel it—even in the dark. And this was nice, fresh, sticky blood—and plenty of it—all over the sheet that I had just wound around myself.

Now I knew why the sheet had resisted when I yanked it—it had probably been partly under something on the bed—something like a dead body, for instance.

I didn't feel much like investigating in the dark, so I felt my way around the bed, and made for the door. My eyes were becoming a little accustomed to the dark, and I could now discern the huddled, still form on the bed, but couldn't make out who it was.

To tell you the truth, I wasn't so much interested in the identity of the corpse, as in getting out of there fast. I let go of the bed, started across the floor, and—plop! I tripped over something soft.

I landed on my hands and knees, and the sheet got untied and fell off me. I wriggled around, trying to get a grip on what I had tripped over, and I let out a sigh of relief. It wasn't another corpse. It was just a pile of clothes. My clothes. I knew they were mine, because the first thing I felt was my shoulder holster, which had a tear in it where a bullet had once slammed into it. Also, I felt my gun in the holster. They had left me my automatic!

I pawed through the rest of the clothes, and found that all the pockets had been turned inside out, and that the lining of the coat and vest had been cut to pieces. My clothes had been searched thoroughly and skillfully.

Well, I didn't mind that at all. All I wanted was to get my clothes on. I can truthfully say that I have never dressed so fast as I did then—and I never expect to again. I did it in the dark, and didn't bother to lace the shoes or put on the tie. The tie was there, all right, but I could feel where it had been ripped open.

Whoever had done it had certainly been anxious to get hold of that pink slip of paper. Well, I mentally chalked one up for Don Manton, thinking of the paper, safely tucked away in the telephone receiver. In spite of the corpse in the bed, I felt fine, let me tell you, with the automatic in my hand. Now I was in business again.

Do you know how long that fine feeling lasted? Right. You guessed it. Less than one minute. Why?

Two reasons.

First, I thought to take the clip out of the automatic. Well, they hadn't been as dumb as I thought they were—the clip was empty. Also, the spare clip was gone from my pocket, together with everything else.

Second, I heard heavy steps outside in the hallway. The steps were those of a big man, but they were kind of stealthy. And then I heard other steps. There was more than one person out there, and they were stopping in front of the door.

IF these birds were coming back to finish up the job on me, they'd know my gun wasn't loaded, and I wouldn't stand any sort of chance whatsoever. I began to think that retreat was a very great part of valor, and looked around the room for windows, kicking myself figuratively for not having thought of that before. I could see pretty well now, and made out two windows on either side of the head of the bed.

I made a quiet dash for the nearest. I stood beside the bed, not a foot from the corpse, and pried up the window. But that was as far as I got. Because there were shutters on the outside, and they were fastened with padlocks. That was why it was so all-fired dark in here—not a speck of light got in through them.

Well, thought I, here is where Donald Faversham Manton goes out in a blaze of glory, with his shoe laces untied, his pockets inside out, dying in a noble cause that he doesn't know the first thing about.

I swung around, crept back to the door, took up a position right behind it, and clubbed my automatic.

Some one on the outside was trying the knob, turning it slowly.

The door was unlocked! If I had been wider awake, not so dazed by that sock on the bean, I might have walked out before they got here! Now it was too late.

The door started to move inward, a half inch at a time. The muzzle of a heavy revolver stuck in between the door and the jamb.

Well, Napoleon had the right idea—the best defensive is a snappy offensive. I always made that my motto, and I acted on it this time. I yanked that door open fast, and the party on the other side came tumbling in. I didn't wait to see who it was, but I brought down the butt of my automatic fast and hard. It went through a derby hat, socked against a head underneath, and that party dropped his revolver and just kind of sagged down to the floor, half in and half out of the doorway.

I made a flying dive for that revolver, figuring I had one chance in four or five hundred of getting to it before whoever else was in the corridor could slam some lead into me.

And I made it.

The reason I made it was because my room was in darkness and the corridor was lit. There was a big, bulky guy out there, and I saw him holding a gun in one hand and a flashlight in the other, snapping on the flashlight.

I could have shot him right then, in that split second before he bathed me in light. I had the revolver up, leveled at him. It would have been a cinch to nick him in the arm or in the shoulder.

But I didn't.

I didn't because I recognized him. That big, flabby bulk couldn't be anybody else but Detective-sergeant MacGuire, of Homicide. And that, believe it or not, is who it was.

I yelled out, "Hold it, Mac. It's me—Manton!" He saw my face in the beam of his light then, and let out an astonished yelp, came into the room slowly.

I put down the revolver on the floor beside the bird I had knocked out, and stood up, wiping sweat from my face.

MacGuire growled, "You slammed Casey pretty hard!" But he didn't lower his gun. He kept it trained on me while his flashlight roved the room, and settled on the body on the bed. MacGuire had never liked me especially, though he had had to work with me many times on account of the connections my clients used to have. Now I knew I was going to be in for it.

He said very soft, in a purring sort of way, "This is very nice, Manton—ver-y nice!"

He came into the room, and saw the light switch alongside the door, which I had been unable to find in the dark. Then he walked over to the bed and stood on the opposite side so that he still faced me, and looked down at the body.

And I looked down at it, too.

And it wouldn't have taken a feather to knock me over. In fact, I almost keeled over from surprise anyway. I guess I had been expecting anything but this.

That body lay on its back, eyes open, staring up at the ceiling. There were six or seven bullet holes in it, two of them through the head. It had stopped bleeding, but there was plenty of congealed blood on the bed.

And you see, the thing that socked me between the eyes was that it was the body of my waxy-faced kidnaper, the gent who had snatched me from in front of the drug store. In short, it was nobody else but Mr. Julian Molina, the very last one I expected it to be—which shows that I'm not so smart after all.

Now, while MacGuire was holding the gun on me and throwing his glims on that corpse at the same time, I suddenly got a flash of intuition that gave me little cold prickles all along the spine. Molina was dead—pumped full of slugs; and my gun was empty. It had been full when I had it. Can you add two and two together? I could. And it gave me a pain in the neck.

MacGuire had the same idea about the same time. Because he walked around the bed, picked up my automatic by the barrel from where it lay near the body of Casey, who was beginning to stir about on the verge of coming to from the sock I had given him.

MacGuire flipped out the clip of my gun, saw that it was empty, and looked up at me with a kind of self-satisfied expression. He waved my gun at me. "Yours, Manton?"

There was no use denying it. I nodded. "Thirty-two," he said. "Looks like seven shots've been fired out of it, an' there's that many slugs in the corpse. What about it, Manton?"

I said, "Hell, Mac—he might have been shot with my gun, but I was cold when it happened. How'd you come to get here?"

MacGuire regarded me for a minute thoughtfully. Then he said slowly, "I got a buzz at headquarters to come to this address if I wanted a line on a certain case I'm workin' on that's just come up. So I brought Casey, an' here's what we find. Looks like a tough spot for a certain guy by the name of Donald Manton!"

I WAS inclined to agree with Detective-sergeant MacGuire.

I didn't like the way he was looking me over, either.

I said, "See here, Mac, lemme tell you what this is all about."

He grinned a little, said, "I wish you would. But maybe you'd rather get yourself an attorney first. A murder rap is a serious—"

"Damn it!" I broke in, "lay off that! You know damn well I didn't kill this guy. I was snatched across the street from my bank, by him and another guy and a dame. They sapped me, and brought me here. When I woke up, this is what I found."

MacGuire's grin broadened. "Can't you just imagine a jury listening to that story. I'm surprised at you, Manton. Is it the best you could think up? You'll have to do better. Maybe you can tell me what case you were working on. Remember, I'm not makin' you talk—you're doin' it of your own free will."

"All right, all right. I wasn't working on any case. I happened to see a dame lift a piece of paper from, an old gent's pocket, and I went after her and took it away. Then she got this bird here, and they came after me. But I cached the paper in a telephone receiver."

It sounded foolish to me as I told it, and I didn't blame MacGuire for bursting out laughing the way he did. I would have done the same to anybody that told me such a dopey story—especially if I liked him as little as MacGuire did me.

He waved with his gun. "Come on with me. I'm gonna find a phone. Maybe you didn't do this, Manton, but you'll have to do a lot of tall explaining to prove it. In the meantime, I'll hold you."

"Wait a minute, Mac," I said desperately. "I can prove it about that paper. You'll find it in the telephone receiver in the drug store. It's pink, and it's got Spanish writing on it—all about how some guy is going to kick off inside of twenty days—"

I stopped, because MacGuire was looking at me queerly.

He said. "You don't say so!" He still held the gun on me, while with his left hand he fumbled in his vest pocket, brought it out, holding a pink slip of paper! "Is this it, Manton?"

He held it out, open, so I could read it. And there it was, the same message in the same crabbed handwriting. It even had folds in it the same as I had folded the slip that I had stuck in the telephone receiver.

I exclaimed, "Good God! Where did you get that?"

"That's what I'm working on," he told me. "This was received by a wealthy member of the Spanish consulate here in New York, less than an hour ago, and he reported it to me. It seems that all Spaniards know all about this when they get it. It's a funny kind of handwriting that can't be copied, if you notice how it's written. Anybody who gets that note knows that he has to pay through the nose, or else—Back in Spain, everybody pays when they get it. This is the first time it's appeared in this country."

"You mean—" I asked, "it's some kind of extortion racket?"

"That's it. The handwriting is authentic, because it's been reproduced in the newspapers, and everybody knows it. Only this feller in the consulate had the guts to come to the police with it instead of paying up."

I was too dizzy to be able to think straight. If that was the same piece of paper that I had hidden in the phone, how had it got to this member of the Spanish consulate?

Suddenly I asked, "Mac—what time is it?"

"Stop kiddin'!" he snapped at me, and bent to feel Casey's head, though he still kept an eye on me.

"I'm not kidding, Mac. What time is it?"

He grumbled, "Casey won't come to for a while yet. I hate to be you when, he does." Then he added grudgingly, "It's three-thirty."

Three-thirty! I had been out for two hours! Plenty of time for a lot of things to happen. I demanded, "Listen, Mac—does the name of the guy in the Spanish consulate happen to be Don Seguro Garcia?"

"It does not! It's Andrea da Luna."

DA Luna! Sure. Elvira da Luna. I remembered Molina, who lay on the bed now, so bloody and quiet, saying quietly in the car, "The lady's name is not Gertie—she is Señorita Elvira da Luna!" Connections, yes. But all around the mulberry bush. I was in this now, and I had to get myself out of it.

I had to get around—get to people who would know what this was all about. Elvira da Luna was one. Eustachio, the bird who had hit me, was another. And so was Don Seguro Garcia, the old gent from whom that paper had originally been stolen. I had to get around.

MacGuire was saying, "Now we'll go phone, if you're through cross-examining me. And then you'll do a little answering of questions. You seem to know more about this than you let on, Manton. An' to me you'll be no different from any other suspect. You'll talk plenty. Come—"

It was then that I hit him. There was no sense arguing with that thick cop, and I had to get around if I wanted to pry myself clear of a neatly framed murder rap.

MacGuire wasn't really expecting that I'd try anything like that. I don't think he really believed that I had killed Molina. He was just taking it out on me, trying to be nasty. So it was a surprise to him, I don't doubt, when that right of mine came up from the floor and crashed him.

As you have already heard, I am big. And when I hit, the hittee stays hit—which MacGuire proceeded to do, joining Casey on the floor.

Maybe it was a damn fool thing to do. They'd be hot after me in no time. But I wasn't one to stay in the can while the case was tightened on me. I always did the first thing I thought of, and worried about it afterwards. That's why I've done pretty well in my racket—getting a reputation for working fast and crashing through cases that might have taken another man weeks; because I'm smarter than the others, but not because I'm a simple guy that always does the first thing he thinks of doing.

And the first thing I thought of at that minute was hitting MacGuire and scramming; which I did—after thoughtfully taking Casey's revolver to shove in my shoulder holster.

So I went out of there, knowing that in about fifteen minutes or more or less—depending on how well MacGuire could take it—there'd be an alarm out for me. But my main object right then was to interview Don Seguro Garcia and see what did he know about the business.

If I'd been smart, my main object would have been to arrange for a good mouthpiece against the time I'd be picked up again. But I wasn't smart, so I went to see Don Seguro.

The last thing I did before locking the door of the room, with the key I found on the outside, was to take the pink slip of paper from MacGnire. So many people were interested in it that I thought I might as well be interested in it myself. If it was the same one I'd put in the telephone receiver, I figured I was entitled to it by this time; if it wasn't the same one, I wanted to compare it.

I went down a flight of stairs, going pretty fast, not bothering about how much noise I made; I was sure there was nobody else in the place. Outside, I took a look up at the house. It was a two-story frame proposition, and I could see that every window in the place was closely shuttered. Over to the left I could see Queens Boulevard, and straight ahead was the Queensboro Bridge. I knew just where I was now.

As for means of transportation, I solved that quick. Right in front of the door was the squad car in which MacGuire and Casey had come, with the motor running.

Nothing could be sweeter. There'd be particular hell to pay later on—but that was something to worry about later on.

I got in the car, and headed for the bridge.

THE Hotel Terranova was a quiet place that didn't seem to make any great effort to encourage transient trade. It was no more than seven or eight stories, and the entrance was sandwiched in between a row of refined stores on the street front. Then you had to go through a long hall before you got to the lobby, which was small, with a restaurant opening on the left. The restaurant was really one of the stores, and this was a sort of back entrance.

There was very little life here—only a couple of old fogies sitting around reading papers, and a clerk behind the desk. The clerk was a small fellow, dark and Latin in appearance, and he kept his eyes on me from the minute I came into the lobby to the time I got to the desk, looking at me with disfavor.

The old fogies also looked up from their papers and gave me the once over. I realized that I did not show up so hot, what with my tie missing, and my shoes unlaced, with the strings flapping. I'd clean forgotten those matters, being engrossed on the drive over the bridge, in figuring all the possible angles of this business—mainly, who the hell had killed my pal, Julian Molina, and tried to hang me on the wall in a neat frame for the job.

I stopped and laced my shoes in the middle of the lobby, and then went up to the desk.

"I'd like to see Don Seguro Garcia," I said. The clerk reached a languid hand toward the house phone, acting as if my being there gave him a bad taste, and asked, "What is the name?"

"Manton—Donald Manton."

He wiggled around on a keyboard in back of him, and pressed the key for room 403, and said into the phone, "Don Seguro, there is someone asking to see you. He gives the name of Manton."

I could see that the clerk was expecting to have the satisfaction of telling me that Don Seguro didn't know me from a hole in the wall, and that I should get to hell out of his hotel.

But he got fooled. Because after listening a moment to the voice from upstairs, he said to me, as if he still doubted it, "You may go up to suite Number 403—Don Seguro will see you."

I grinned, and crossed the lobby to the elevator.

When I knocked on 403, the door opened and I nodded at the now familiar mug of the old gent who'd had the pink slip lifted from him in the bank vault.

He bowed very courteously, and waved me in without even asking my business—this old Spanish courtesy was the nuts, thought I.

Inside, he said, "Will you not be seated, señor? Your name—I do not recall where I have heard it before—"

I sat down opposite him, and gave him the once-over. He'd just had a shave, and his smooth skin, though dark, stood out in sharp contrast to his moustache and Vandyke. He wore a dressing gown over his vest and trousers. Behind him, another door, partly opened, revealed another room. We were in a sort of sitting room, and I figured the other was a bedroom.

I said, "Don Seguro, you don't know me, but I've had occasion to look you up. This morning you were at your safe deposit vault, weren't you?"

He looked at me blankly. "I, señor? This is strange. I have no vault. You are, perhaps, mistaken?"

He rose, and though his aristocratic face showed no discourtesy, his whole attitude indicated that as far as he was concerned, the interview was over.

I stared at him for a minute. "You mean to say, Don Seguro, that you didn't take a pink slip of paper from your safe deposit box this morning—and that you later missed the paper?"

He shook his head slowly. "I do not know to what you refer, señor." He talked like I was a lunatic, and he was humoring me. "Perhaps we can go into this at some other time, if you do not mind; I am somewhat occupied—"

"Wait a minute!" I barked. I took the paper out of my pocket, held it out in front of him. "You mean to say you never saw this?"

His eyes scanned the writing, and I detected a trace of fear in them—maybe it was fear, maybe it was something else, I don't know, because things started happening fast.

He said, "If I may, señor," and extended his left hand for the paper. I snatched it away. "Nix! Everybody seems to want it. You can look at it, but don't touch it."

He smiled. "Perhaps this will induce you to give me the paper." He said it very softly, and I found myself looking into the hole of a nasty little snub- nosed automatic that had come out of his dressing-gown pocket, in his right hand.

The smile disappeared from his pan, and he just stood there, not saying anything else.

As for me, I started to curse him—under my breath. Here I'd gone and got into plenty of messes on account of feeling sorry for him losing that paper in the first place, and what does he do to show his gratitude, but make me out slightly batty, and then pull a gun on me.

Here I was, hunted by MacGuire, suspected of murder, and finally held up by the very guy I had been trying to help. Let this be a lesson to everybody in our business—never do anything for anybody unless you're paid for it. That way, at least, you have the consolation of knowing that there's a little change coming to you if you crash through. But this way—nuts to this helping hand stuff, say I.

The way I felt now, a little thing like an automatic wasn't going to stem me. This old gent couldn't be so awful fast, and I was just setting myself, figuring my chances on smacking his wrist aside, when that dame appeared in the opposite doorway.

Which dame?

Why you ought to know—Señorita Elvira da Luna, of course. The very dame who had lifted the paper from this gent in the bank! Do you feel surprised? So did I!

SHE was holding a gun, pointing it at me, and laughing sort of happy-like, like a cat that finally corners a rabbit after having chased him all over the lot.

Behind her there appeared this bird Eustachio, that had socked me in the car, and the wooden chauffeur who had driven us out to Queens. They both had guns too, and handled them awful careless like, as if they didn't care if they went off or not.

Some party, huh? And all in honor of yours very truly, Donald Manton. Oh, I like it a lot—nit!

Señorita Elvira da Luna came into the room, and stood alongside of Don Seguro. Eustachio and the chauffeur spread out on either side, in back of them, and there I was, still holding on to the paper, and feeling foolish.

The dame kept her eyes on me, and said to the old gent, "How deed he get those paper, uncle?"

Uncle! Was this dame the niece to all Spain? She'd called Julian Molina uncle, too. And Molina was dead back there in Queens, with seven slugs in his carcass. I was beginning to be sorry for Don Seguro, now—and hoping she wouldn't start "uncl'ing" me next.

Don Seguro said very quietly, "I do not know how he got the paper; I thought perhaps you could explain that. Was it not you who thought of the telephone after we had searched him? Was it not you who suggested that we use it to force money from your own husband, Señor da Luna, at the consulate? You must have known that your husband would not pay—you perhaps even expected that this detective would not be held for killing Molina." His voice got a little higher in pitch with each accusation.

Now he swung around so that his gun was pressing against her side. "And now," he went on, the señor comes here with the paper in his hand. Did you expect this too?"

I was starting to enjoy this a lot. I was getting information, and it wasn't costing me a nickel. Also, I liked the way things were turning out, though it was still mostly Greek to me.

Elvira didn't seem to take it so nice, however, with Don Seguro's gun in her side. Her face got a little pale. Don Seguro moved over a bit, grabbing hold of Elvira's arm with his left hand, while he kept the gun on her with his right.

That put Elvira between himself and Eustachio and the chauffeur. He said to her in a very unfriendly way, "Perhaps you expect even that your husband will come here to this place? You were playing with us all the time!"

Husband! Besides having uncles all over the lot, this dame also had husbands. A very versatile dame.

This all began to look more or less like a joke to me. I couldn't imagine these grown-up people shooting each other up over a slip of pink paper with some Spanish writing on it—especially in a hotel where the first shot would bring down the house.

But then I remembered Mr. Molina, all full of holes. It seemed they did shoot each other up.

The dame was keeping silent, although from the way she looked it seemed she knew she was in one hell of a spot. And to sort of encourage her to say something, Don Seguro poked her with the gun. He nodded to Eustachio and the chauffeur, and said to them, "If it becomes necessary to shoot, do not hesitate. This hotel is solidly built, and the walls have been made sound proof; nothing will be heard outside."

I could see that lots of action was coming. There was more at stake in this business than I had guessed.

Well, that was all right with me. Because now was a good time to start it.

You see, in poking that gun into the dame's side, Don Seguro had moved over just a trifle, so that I was at his right, and slightly to his rear. He must have figured that the other two had their eyes on me. What he didn't figure was that he himself would make a swell shield.

Which he did.

I flipped Casey's revolver out of my shoulder holster, moved over about six inches so he was between me and the other two birds, and let him have a feel of the muzzle in his side, just as he was doing to the dame.

"Suppose we get back to normal, ladies and gentlemen," said I.

I GUESS I was too optimistic. There were too many guns loose in that room for the party to proceed peacefully.

Don Seguro was all right. He stiffened, started to let out a very naughty Spanish cuss word, and then, when I jabbed him a little harder, he got meek and submissive, and lifted the gun away from the dame's ribs, let it drop to the rug as I requested him to do.

But the dame still had hers, and she jerked it up with a nasty look in her eyes at him. I had to reach past Don Seguro with my left hand and smack her wrist hard. She let out a yelp, and dropped the gun.

But Seguro's pal, Eustachio, swung into action at the same time, and slugs from his revolver came slamming my way. But I had given Don Seguro a quick yank to the left, and a couple of those slugs caught him with a nasty, smacking sound, and he was thrown backward, almost knocking me over, and getting in the way of my own gun hand.

I dropped to my knees, and Don Seguro fell over me, but I had a clear field now, and snapped a shot up at Eustachio that caught him over the heart. That was the end of Eustachio.

The chauffeur had been afraid to shoot, because he was a little to the left of Eustachio, and Seguro was in his line of fire. He was dancing over toward the window, from where he could get a clearer shot, but I didn't give him any chance at all to do damage. I swung Casey's revolver around, and fired, just a half-second before he did.

When I'm shooting at a guy who-seems to have a desire to sling lead my way, I never go easy. So I gave it to him right between the eyes, and the heavy slug from the service thirty-eight carried him backward, slapped him hard against the wall. He slid down to the floor. Naturally, he was dead.

I swung around just in time to kick the gun on the floor away from Senorita Elvira's hand, as she was reaching for it. She raised her eyes to me, mad as hell, and did a swell leap up at my face, both hands clawing for my eyes.

Believe me, that was a bad two minutes. Before I got hold of her two hands, she had raked her fingernails down my face a couple of times. I wouldn't be able to shave for a week now, until those furrows she made were healed.

I gripped her two hands all right, but she wasn't licked yet. She started to kick me in the shins, struggling like a wildcat.

I let go of Casey's gun, swung her around with her back to me, and got both her hands behind her. She tried to kick backward, but I held her away from me at arm's length, and her heels didn't reach.

After a minute or two she quieted down, and stood there, breathing hard, with me holding on to her, and not knowing what to do about it.

I took a glance down at Don Seguro on the floor. He was looking up at us, holding a handkerchief over his left side. Blood was also seeping up through his coat from his left shoulder.

The room was kind of smoky, but nobody came to the door. The sound of the shots had not penetrated the sound-proof walls.

I said, "Well, lady, you're certainly death on uncles!" Don Seguro had not long to live. From the location of the wound in the side, I judged that it had got him in the lung.

He glanced at her venomously. Blood frothed to his lips as he snarled. "I am no uncle of hers."

I guess I looked kind of blank. "So will some one kindly tell me what all the shooting is about?"

The dame swung around as far as my grip on her arms would allow her, half facing me. She looked weak and helpless now. All the fight seemed to be out of her.

"Please—please," she begged me, "destroy that note. I have been mees- taken about you—you are but an honest fool. Believe me, you will do a great service to a noble family if you destroy that note!"

Don Seguro began to laugh bitterly. It must have wracked him painfully to laugh, for he stopped suddenly, and his face became contorted with agony. But he managed to say, "A very honorable family. Her uncle, Julian Molina, is a murderer ten times over—the man who wrote that note, and those other notes that terrorized all Spain. He—"

The old gent couldn't say any more; his mouth was full of blood. His head dropped back, and he closed his eyes. He was breathing heavily, with a horrid bubbling sound.

I glanced at the dame. She looked wilted, licked. Her whole body drooped. However, I didn't trust her; I kept my hold on her hands. Those fingernails could do plenty damage.

"Eet ees true," she said, almost under her breath. "I was trying to save the family honor by stealing that note from Don Seguro. And now my hos-band he comes here, and he will learn all!"

"Maybe he will, lady," I told her. "But yours very truly is still in the dark. How about—"

And then there came a heavy pounding on the door. And MacGuire's voice. "Open up in there. This is the law!"

I SHRUGGED. No sense in delaying it any longer. If there had to be a showdown, it might as well be now.

I pushed her across the room, slipped back the latch. The door was shoved in. But MacGuire wasn't the first one in. The first one in was a tall thin guy with a little mustache and a look of class. He had eyes for nothing in the room but the dame I was holding on to. He croaked, "Elvira! Cara mia!" And then he sees her arms are behind her and I'm holding on, so he barks at me, "Let go of my wife, you!"

I let go of her. MacGuire was in the room now, and so was Casey, and from the nasty way they were grinning I saw that I'd have my hands full.

The dame fell into the arms of this tall thin guy, and started to moan, "Andrea! Andrea!"

MacGuire and Casey walked around them toward me. MacGuire had a red spot on his jaw where I had hit him, and Casey wasn't wearing any hat—on account of the lump on his head.

MacGuire was swinging his huge paws. "So, Mr. Manton," he said very sweetly, "you bump off a guy, and then you attack two officers of the law! I am surprised at you. Mr. Manton—surprised— and—gratified!"

His paws reached out for me, and I got ready for what was coming.

But the dame suddenly broke away from her husband, and rushed in between us.

"No, no!" she cried. "He did not keel my uncle, Julian. Eet was Don Seguro!" She pointed dramatically at the old gent, who was lying very quiet, but still alive.

MacGuire stopped very reluctantly, and for the first time he took in the rest of the room—the two bodies, and Don Seguro. He looked questioningly at the dame, and she stepped back into her husband's arms, buried her head in his shoulder, and started to sob.

I don't have to tell you I was glad of the interruption, because MacGuire and Casey looked mad enough for anything, and I couldn't blame them much.

MacGuire barked at her, "Lay off the sob-stuff, lady, and give us the straight of this!"

Her husband patted her hair, and said, "That is right, Elvira. These officers but wish to know the truth. Speak without fear. How do you come here—and who are these dead men?"

She stopped sobbing and stood up straight. Boy, she was beautiful, with her eyes full of tears. "I weel explain." She tugged her husband's lapel lightly. "Andrea, you must forgive me. I did not wish you to know, for the sake of the family honor. Julian Molina is my uncle! It was he whom all Spain feared; he whose pink notes extorted so many thousands of pesetas from the aristocracy of Spain."

He smiled down at her. "It makes no difference to me, cara mia. "

MacGuire grunted. "Yeah, but it makes a difference to me. So what about it?"

She went on. "Don Seguro, there, but recently arrived from Spain. While Alfonso was king, Don Seguro had been police commissioner in Barcelona, and that pink note which the tall detective holds had been turned over to Don Seguro by a family that had received it. Seguro brought that note to this country with him, among his other papers."

I was beginning to see a light, but it was a very dim light, I will admit.

MacGuire still couldn't see a thing. He kept throwing me nasty glances. I could see that all he wanted was a couple good cracks at me.

Señora Elvira continued. "While in this country, Don Seguro made the acquaintance of my oncle, who had also come here, likewise compelled to leave Spain upon Alfonso's abdication. Don Seguro saw my oncle's handwriting, and noted the resemblance to the writing upon the pink slip. He blackmailed my Oncle Julian—demanded a so-great sum of money for the note. Julian came to me, and insisted that I give him the money to pay to Don Seguro. I had not the money, and—" she glanced shyly at her husband, "I feared to ask you, Andrea—"

MacGuire was now looking at me in a puzzled way. Also, he was feeling his jaw. I could see that the only thought on his mind was that it was taking a hell of a long time for him to get in that sock at me.

I said desperately, "Don't you see yet, Mac? What I told you was the truth. This dame lifted the paper from the old gent there, and I caught her doing it, took it away from her. Molina must have been waiting for her around the corner somewhere, with the car, and they came back and picked me up. Isn't that right, lady?"

She nodded, raised her head miserably. "But Don Seguro must have followed us there. He killed Julian, and then he spoke to Eustachio and the chauffeur like- what-you-call-a Dutch oncle. He tol' them that he knew their records from Spain, and that they would hang if he deed not choose to save them. He tol' them he would save them from the law if they would throw in with heem. So they swore to obey heem in all things, and he promised that he would pay them well."

"Yeah," said MacGuire, "but about that note. Manton is tryin' to tell me he stuck the note in a telephone receiver. How come it got sent to your husband?"

SHE looked up at her Andrea and shuddered. She spoke to him, as if she didn't care if anyone else understood or not. "Don Seguro searched Meestair Manton, and could not find the note. He was like a wild man. He threatened—" she blushed beautifully—"to search me, to torture me! I was desperate, and I cast my mind back over the last hour. I told Don Seguro that I thought Meestair Manton had dropped that note in the telephone booth, while Julian and I watched him from the car. I deed not think it so, but I hoped that Don Seguro would go to look for it, and that so I would be spared the indignity of being—searched. I thought to gain a little time."

MacGuire looked at me disgustedly. "Can you beat it? It took a desperate dame to guess what a half-wit did with that paper!"

The dame went on breathlessly, "Eustachio and the other brought me here, while Don Seguro went to the telephone booth. Eemagine my wonder, when Don Seguro returned weeth the note! When he had arrived at that booth, he had found a repair man from the telephone company, for the paper had caused the phone to become out of order. Don Seguro saw the repair man take from the receiver the pink paper, and he claimed it as his own!"

She went on with a rush, "Don Seguro was a wicked man. He planned to use that note to extort money from Spaniards of wealth!" She swallowed hard, and dabbed her little lace handkerchief at her eyes.

"Oh, Andrea, how shall I tell you what I deed next? I pretended that I had been an accomplice of Julian's. I suggested that he should try to extort the money from—you! I said that I no longer loved you, that I wanted but your money." She raised her eyes to the ceiling. "God forgive me, I wished no one but you to receive that note. Then I could destroy it so that the shame of my Oncle Julian might remain a secret within the family!"

Andrea da Luna stooped and kissed his wife. "Cara mia, you should have told me all in the beginning. Much would have been avoided."

He held her tight, and looked up at us. "Gentlemen, those who have died, deserved to die. We Spaniards are a proud race. Can we not spare my wife and her family the disgrace that would weigh down their heads if Julian's rascality became known? That pink paper with his handwriting is the only evidence against him. He has paid with his life. Is it necessary that the pink paper should be made public? Perhaps—"

MacGuire interrupted him, red-faced. "Nothing doing. That paper—"

"What paper?" I asked.

MacGuire spun at me, scowling. "You know damn well—"

He stopped, his face went red, and his fists clenched. Because he knew what I meant. He could see plainly what had happened to it, because he saw my gullet working over it where it stuck for a second in my throat before going down. I had swallowed it.

Andrea da Luna was smiling broadly. Before MacGuire could get out the flow of profanity that was gathering within him, Da Luna said, "Sir, that was a most happy thought upon your part. Your wits are quick indeed. I shall show my gratitude by arranging for you to receive the reward."

MacGuire had been about to use more than profanity; he was towering over me, and I could almost feel those two hamlike fists of his landing in my solar plexus. But at that word reward, he stopped short. It's a very intriguing word.

Da Luna saw us look blank, and explained. "I have some influence with the present government. As you know, I am attached to the consulate. The Spanish government has offered a standing reward, which is equivalent to ten thousand dollars in United States money, for the death of the terrorist who wrote those notes. I shall see that you receive it, sir."

MacGuire bellowed, "You mean his executors—" and swung at me.

I blocked the blow, danced away grinning. "Wait a minute, Mac. You don't think I'd hog it all!"

He looked at me funny, getting all set to follow me up.

I said desperately, "Three ways, Mac—you, me and Casey. And we forget about the pink slip of paper. It's diplomatic courtesy, you know."

Mac hesitated. Thirty-three hundred and thirty-three dollars and thirty-three and a third cents is a lot of dough. He looked at Casey, and Casey looked at him, and then they both looked at me and grinned.

And did I heave a sigh of relief!

Da Luna had let go of his wife for long enough to step over to Don Seguro. "He's dead," he announced. "There will be no difficulties."

He went back and took her arm. "You see, cara mia, all has turned out well."

She smiled up at him happily, then came over and kissed me on both cheeks. "I took you for a fool, señor. I have learn' now that looks are deceiving."

Did I blush!

I said, "See here, señora—there's one thing I'd like some enlightenment on."

"Yes?" She would have told me anything I wanted to know at that minute.

"I understand about that Molina egg—but why did you call this Don Seguro 'uncle?'"

She said shyly, "He is so old. In Spain we call all old men oncle. It is an old Spanish custom!"