RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

Roger Vane, ace dick of the B.P.A., was up against the most ghastly spectacle of his career. He saw a man with an empty skull. That living-dead man had walked the streets without a brain. And when that man died, the medical examiner could not call it murder. For it was merely an accident. The police were baffled, helpless. But Roger Vane played a hunch— and was plunged into a grisly hell-hole of horror.

"Secret Agent 'X', March 1934, with "Satan's Scalpel"

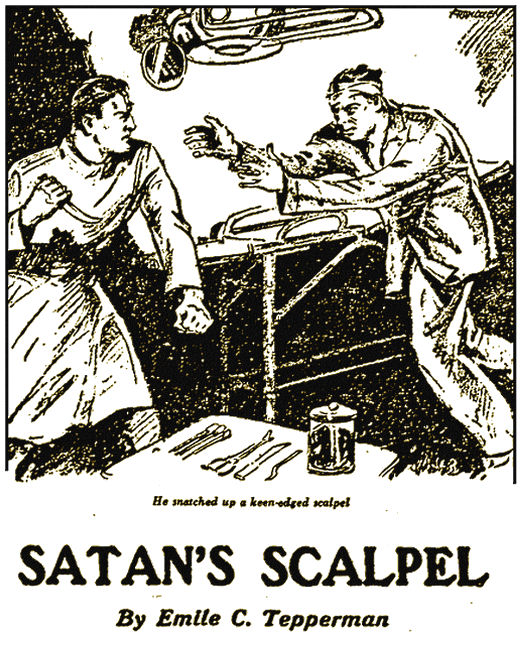

Headpiece from "Secret Agent 'X'"

WHEN Red "Killer" Dolen escaped from the death house in state prison by the absurdly simple device of walking out of the exercise corridor, apparently unscathed himself while every other inmate and official was rendered unconscious by a swiftly vaporizing gas, not a single line of news was allowed to reach the general public.

The keepers recovered their senses a half-hour later to find that Dolen, the most brutal stranger of the decade, had cheated the electric chair. How he must have laughed, they thought, as he drove through the gate, unchallenged, in the warden's personal car.

A small quantity of the gas was found where it had settled in a damp pocket of the cellar. The police chemist had difficulty in analyzing it, but thought it showed traces of a hitherto impossible combination of ethyl chloride and scopolamine.

An intensive undercover search was conducted, but at the end of a week no single trace of the escaped convict had turned up. The whole business gave evidence of having been planned and carried out by a highly scientific mind endowed with devilish ingenuity.

Now, Roger Vane, special investigator for the Bankers' Protective Association, knew about the Dolen escape all right. There was little in criminal activities that slipped past his notice. Yet the knowledge lay fallow in his mind for a week until the day he looked at the man with the empty skull.

At that particular time Roger was working on the biggest case of his career—the disappearance of three million dollars in gold from the Empire City Bank. The B.P.A. paid him a very comfortable salary for that kind of work—not to hunt for escaped murderers.

The events leading up to that disappearance, as Roger outlined them in his mind, were, briefly, as follows: Courtlandt Spears, the middle-aged president of the Empire City Bank, had returned to his office after a short vacation which he had taken for the purpose of undergoing a minor operation.

It was a bright Monday morning. The special officer in the lobby of the bank greeted him warmly. But he got only a sour nod from the president, who went straight through and up to the mezzanine where his private office was located.

MR. SPEARS' first official act was to summon the cashier. "Mr. Hubble," he said, sitting behind the immaculate glass top of his broad desk, "under this new National Recovery Act we are compelled to turn our gold in to the Government. What are we doing about it?"

Hubble shuffled from one foot to the other and arranged his tie with nervous fingers. Though he had been with the bank for twenty-two years he always felt slightly awed by "Old Man Spears" of whose moods he was wary. "We now have three million dollars in gold in the vaults, sir, all earmarked for the Treasury. We were awaiting your return, as we have no authority to move it without your formal signature."

As he summarized the situation for the president, his fascinated eyes focused on his superior's left cheek where that old familiar birthmark flamed brightly red. He called it a birthmark for want of a better term. In reality it was a discoloration of the skin about the size of a dime in diameter, just below the cheek bone. It usually flared up when Spears was laboring under some undue excitement. And now it was flaring to a brilliant hue.

"Funny," Hubble thought. "I wonder what's biting the old man now?"

Spears said to him calmly, as if ordering a chicken sandwich sent up for lunch, "Make the gold ready to be moved, Hubble. It is now ten-thirty. At eleven-thirty an armored car will be here to pick it up."

"B-but, Mr. Spears," Hubble stammered, "this is very irregular. We have no arrangement with the Treasury. They won't be ready to receive it. And besides, there should be an adequate guard. Three million—"

Courtlandt Spears interrupted him coldly, very low-voiced. "Make out the proper order and I will sign it. Do you understand me, Hubble?"

The cashier knew that tone. When the boss talked like that it was safest not to argue. So he went out and dictated the form. He brought it into the office and watched the president affix his signature—the signature with that inimitable curlicue, at the end.

"That's a signature nobody in the world can imitate, sir," Hubble said, with the proper tinge of admiration. This was one of the boss's weak points, and the cashier liked to play on it. He always made the same remark, and he always got the same satisfied smirk in response.

This time, though, Spears only peered at him in silence, lifting his eyes from the paper—and Bubble felt his chest contract with a queer, clammy coldness. The eyes of Courtlandt Spears seemed to mask some strange, grotesque personality.

Still feeling cold and creepy, he went down to the vault and superintended the moving of the gold into the armored car that appeared shortly.

When he told his story later to Roger Vane and Inspector Cummins, his face was white and his hands were cold. He could tell them nothing further to aid the investigation except that there seemed to be only one guard with the driver of the armored car, and that at the last moment Spears himself had come down and announced that he was going to ride with the gold. No one had dared to argue with him for he appeared to be in a vicious mood.

The reason for the investigation was, of course, that the armored truck never showed up at the Treasury, and that Courtlandt Spears vanished from the earth.

ROGER VANE spent a week following up the most far-fetched of clues and the thinnest of leads. The Bankers' Protective worked closely with the police, but nobody could even get to first base on it.

Roger was going over every fact at his command, hoping to catch something that had been previously overlooked, when he got the phone call from Inspector Cummins. The inspector's voice, for all, his kidding, held a strange overtone of excitement. "If you're not too busy drawing pay from the B.P.A. for nothing," he said over the wire, "come up here to Pelham Parkway. I'll show you exhibit number one in the Empire City job. And it's some exhibit, believe me!"

"Okay, Mike," Roger said. "I'll be up there in twenty minutes."

"Don't call me Mike, you lanky beanstalk!" Cummins roared over the 'phone. "Inspector to you!"

"All right. Mister Inspector Michael Cummins," Roger murmured sweetly. "Just where are you at?"

He got the exact location, then put his mouth close to the instrument. "Thanks. I'll be up there pronto, Mike—you hippopotamus!" He hung up, cutting off the inspector's bellow.

Roger Vane's cab driver, enticed by the promise of double the meter reading, made it to Pelham Parkway in eighteen minutes flat.

Just past the intersection of Eastchester Road there was a good-sized crowd—and it was growing bigger by the second. The Parkway was cluttered with radio cars. An ambulance, stood near by. There was a cleared space in the center of the crowd.

Roger used his elbows ruthlessly. A couple of neck-craners got sore ribs, but he fought his way to the inner circle. He was greeted by Inspector Cummins whose double chin shook as he said, pointing to the stretcher on the ground. "There's your exhibit one. Get ready for the shock of your life."

An interne was kneeling beside the stretcher. On the canvas lay a man, naked under a white sheet. Roger's gaze traveled up the supine body to the head, and his eyes bulged. Suddenly he felt sweat on the palms of his hands. His jaw opened but he said nothing. For once he was speechless.

Cummins nudged his elbow. "You wouldn't believe it if you didn't see it, Roger!"

In the top of the man's head was a gaping hole. And the inside of his skull was empty.

The young interne's face had a greenish tinge. He was holding the man's pulse. But the other hand, that held the watch, was trembling so that the numerals on the dial seemed to be doing a macabre jig.

Roger swallowed and asked, "What killed him?"

The interne looked up from the watch. Something sounded in his throat that was meant to be a laugh. "Nothing killed him," he said in a wet voice—the kind of voice you use when your salivary glands are discharging freely, "He's not dead yet!"

"Not dead!" Roger shouted down at him. "How can a man live with his brain gone?"

The interne waved widely, nervously, with the hand that held the watch. "Did you never see a chicken stagger around without its head? Or a snake? This is the same—only it's a man!" He squeezed his eyes hard shut, and opened them swiftly. "God! I never saw anything like this!"

"How did it happen?" Roger demanded. "Where did he come from?"

But the interne hadn't heard. He bent swiftly to the stretcher, watching the man's face tautly for seconds. Then he sighed deeply and put the watch away. He allowed the wrist he had been holding to drop to the canvas.

He arose and dusted his knees. He took out a handkerchief and brushed his lips, then carefully wiped his hands. "He's dead," he announced. He fumbled for a cigarette and lit it after losing the light from three matches.

Roger waited till he got a deep inhalation out of his lungs, and repeated his question in a kindly tone. "Now, doctor, tell us something about this. Where did he come from?"

"I was in the rear of the ambulance," the interne related, "when I saw him. We were coming down the Parkway and I just happened to glance out across the field there. Do you know what he was doing?" He jabbed a finger at Roger and then at Inspector Cummins. "He was running! The field is at least half a mile wide. He must have run that far—without his brains!"

Roger Vane let his eyes travel to the gruesome form on the stretcher. "Go on," he urged. "What happened?"

"Well, I yelled for the driver to stop. And this chap came running toward us. Then he dropped right here, alongside the road. He might have lived longer, but the undue exertion severed the membranes that had been sewed together at the ends of the intraventricular channels in the cerebellum. This permitted the cerebrospinal fluid to escape. Death followed."

Roger had dabbled in many things in the course of his career. He had a smattering of the elements of surgery, and he knew enough of anatomy to understand the interne's labored explanation. But Cummins boomed out in his bull's voice, "Never mind why he died. Anybody can see he was overdue to cash in. What I'd like to know is, how he stayed alive—how he could run without a brain!"

The interne's eyes were bright with an unhealthy light. "I'll tell you, inspector. This man has had an operation performed on him—one that has never before been attempted on a human being! Do you know what was done to this man?" He gulped and went on, the words coming feverishly. "Whoever cut him up is probably the greatest surgeon in the world—and a ruthless devil!

"He trephined this poor chap's skull, turned up a flap of scalp and bone, then lifted out bodily the whole cerebral cortex—the thinking part of a man's brain. He left in the cerebellum, which is that part of our brain controlling the reflex actions. A man with only a cerebellum can perform physical actions such as feeling, tasting, smelling, running. He can know fear and hate. All these faculties are governed by the cerebellum which that surgeon of hell left to this poor devil. But he took out the cerebral cortex, which is what makes man superior to animals!"

They were interrupted by the arrival of the medical examiner.

The inspector drew Roger aside. "You know why I got you up here?"

Roger nodded. "I do, Mike."

"Dammit!" Cummins growled. "Don't call me Mike!" Then, anxiously, "Well?"

Roger inclined his head again, this time very somberly. "It's Spears, all right. He's so emaciated it's almost impossible to recognize him at first glance. But that birthmark is there. You can't mistake it."

"What's the answer?" Cummins demanded.

Roger was reflective. "I don't know, Mike. It's big, whatever it is."

Cummins' laugh grated. "Sure! Three million bucks is big in any language. Whoever that surgeon is, he's a lot smarter than you and me! Can you figure out what he wanted the old man's brain for?"

Roger suddenly snapped his fingers. "Listen, Mike. Spears had just come back from an operation before he pulled that disappearing act. You looked into that end of it. Who was the surgeon?"

Cummins thumbed through a note book and read off the information. "Operated on for appendicitis at Doctor Felix Gassner's Private Sanitarium, 1800 Eastchester Road, New York City. Operation successful. Dr. Gassner is noted surgeon. His patients among wealthiest in country. He came here from Vienna five years ago. Has international reputation. Gassner states he discharged Spears in good health. Has no suggestions to offer."

Roger gripped the inspector's sleeve. "I think," he said, "that things are beginning to clear up."

Cummins scoffed. "Don't get all het up."

"Listen," Roger insisted. "1800 Eastchester Road is less than a mile from here. Spears might have come from the sanitarium."

"Sure, that's bright! And if Gassner is the one who cut out his think tank he's too smart to send him out to be found in this vicinity! And anyway, what would he want to do the whole thing for? If Spears had the gold he could just have taken it and killed him."

"Just the same," Roger replied, "let's get a warrant and go up there."

The medical examiner had finished his task. He came over to them.

"What say, Doc," Cummins asked.

Doctor Evans was putting away his stethoscope. He shook his head in a puzzled manner. "The ambulance doctor is correct. The man's cerebral cortex has been removed by a most cunning operation. The surgeon who did it is a wizard."

"How long," Roger inquired, "would an operation like that take?"

"About five hours. It is first necessary to cut through the bone of the skull. This is done nowadays with a drill and burrs. Under the bone is a layer of tough, fibrous membrane. Then below that we find the thin web-like tissue that is the envelope of the brain. All this is familiar territory. Modern surgery has occasion very often to penetrate this far in order to relieve pressure on the brain.

"But that was only the beginning for this surgeon. He had to sever all the membranes connecting with the cortex, and then he had to sew them at once to prevent the escape of the brain fluid which is contained in little hollows known as ventricles. The job has always been considered impossible."

Roger said, motioning to the body on the stretcher, "it's murder, isn't it?"

Doctor Evans shook his head. "Not technically. The operation was entirely successful. He could have lived indefinitely. His death was accidental. A membrane was severed and the brain fluid escaped."

"You mean to say," demanded Roger, incredulous, "that you're calling this accidental?"

The examiner shrugged. "What can we do? Inspector Cummins will agree with me. The evidence here points to nothing but the fact that an operation was performed. We cannot even say that it was illegal. I don't care if Spears made away with three million or thirty million. I have nothing to do with any other crimes that may be connected with this. My business is to determine how this man died, and I tell you I can't call it murder!"

Cummins grinned. "Well, Mr. Vane, how about that warrant you were going to get? What would the charge be?"

"Go ahead," Roger snapped. "Have fun! I'm going to pay a visit to Doctor Gassner anyway!"

"Your privilege," Cummins said nastily. "You're a high-class investigator. You can follow hunches and things. Me, I'm just the police. So I'm starting a house-to-house canvass of the neighborhood. Maybe we'll find some one who saw where Spears came from."

ROGER dismissed his cab a block from Dr. Gassner's sanitarium and approached the three-story brownstone on foot. He did not, however, go up the steps to the front door, but walked around and proceeded down the auto runway that ran along the side of the building.

There was a big brick garage in the rear that covered the full width of the lot.

He did not see the car that pulled up at the curb a minute behind his cab, nor did he see the figure that followed him down the block on foot and then stole up the steps into the house.

He was interested in that garage. The front of the garage consisted of four sliding doors that went up to the roof. Set in one of these doors was a smaller door that swung on hinges. This smaller door was securely fastened by a huge padlock. Roger drew a set of keys from his pocket. The padlock snapped open after a moment's work, and he stepped through the doorway into the darkness of the interior.

He snapped on his fountain pen flashlight, and his eyes narrowed. An expensive small coupe stood in one corner. But it was dwarfed by the immense moving van that occupied most of the rest of the space. This was the type of van that is used for transcontinental trips. Its rear doors were also padlocked.

He brought his keys into use again, and swung open the doors. He whistled as his flash played on the armored car within the body of the van.

He peered closer and saw that the van had a double floorboard. The lower leaf slid out when pulled, and sloped down to the ground on hinges, forming a perfect runway on which the armored car could have been driven into the body of the bigger car!

That was all he needed to see. He clicked off the flashlight and turned to go. Then he stopped, rigid, his hand arrested on its way to his shoulder holster.

The lights blared on in the garage. A man stood just inside the doorway, covering him with an automatic. The man was big. He towered over Roger's five feet ten. The hand that held the automatic was hairy, tremendous. The face was a potpourri of broad, flat features and expressionless eyes. He said to Roger in a dull voice, "Come out."

The two words were plenty. Roger came out.

"Up the back steps and in the house." his captor ordered.

Roger had more a feeling of curiosity than of fear as he let himself be herded into the house and along, the corridor into a room that was manifestly the office of the sanitarium.

A small wiry man with a hair-line mustache and keen black eyes sat at a desk. The big fellow closed the door behind them and stood with his back to it. Roger couldn't see him now. He faced the other.

The little man arose and made a signal to the one with the automatic. Then he bowed to Roger. "You are," he said in a smooth, precise voice, "the well-known Roger Vane, investigator for the Bankers' Protective Association?"

Roger nodded. "And you, I suppose, are the famous Doctor Felix Gassner?"

"Correct. You are very clever, Mr. Vane.

I am glad that I sent Ivan, here, to watch the crowd over at the Parkway. Had it not been for that, you might have surprised me."

Roger was only half listening. He was gauging the possibility of springing aside and drawing his gun before the big Ivan could attack him from the rear.

Doctor Gassner seemed to read his mind. He smiled. Roger saw that those thin lips could be utterly cruel. The black eyes stared at him like two soulless disks. "It'll do you no good, Mr. Vane. Don't you feel it already? There is a gas in this room. Look behind you and you will see the tank alongside the door. Ivan just opened the valve at my signal."

Roger cast a quick glance behind and saw that it was true. Ivan grinned at him mirthlessly.

Doctor Gassner went on. "That gas is a development of my own. It is a compound of ethyl chloride and the basic anesthetic, urethane. Your police chemists were unable to break it up, I noticed. They thought it contained scopolamine."

Roger was dazed. He felt giddy, but suddenly he saw the connection. "Then you—"

Gassner nodded with a self-satisfied smile. "I am the one that arranged Dolen's escape. But we will go into that later. I have plans for you. About the gas, though. I used urethane because I have perfected a serum which I find renders me immune to its effects. Ivan and I have both taken injections of the serum. You, of course—"

The room, and Doctor Gassner's face, suddenly lit with the anticipation of unspeakable horrors, seemed to be reeling farther and farther away from Roger's dimming senses. He tried desperately to raise his hand, to get at the automatic. His brain ordered, but his muscles were numb—they failed to react. Everything seemed to grow dull. He saw the doctor's face fade to a grotesque shadow. Then his legs gave under him, and he went to the floor under a wave of blackness.

WHEN his eyelids straggled open he was not in the same room. It was still light. His head seemed clear enough. The gas had left no aftereffects.

He tried to move but couldn't. He was strapped to an operating table. The thick leather straps were buckled tight about his elbows, wrists, thighs, and ankles. He was naked, but a sheet had been thrown over his body from the chest down. He shuddered. What plans did that fiend have in mind for him?

His eyes wandered across the room. Along the opposite wall stood a row of tall glass cabinets with glass shelves. On the shelves lay a multitude of glittering steel instruments. Among them were many knives, some straight and long, others curved and short and ugly, but all with razor-keen edges. What dreadful things those knives could do to the human body. His face blanched as he realized that he lay helpless in the operating room of Doctor Felix Gassner's sanitarium.

He tore his gaze away from that glittering array of chilled steel instruments. He turned his head in the other direction. And suddenly every fiber in his body contracted. He could feel the sheet that covered him grow wet from the sweat that began to run from every pore of him.

It was a man, yes. And it sat rigidly in a chair by the window, staring at Roger. Its eyes were dull, but behind them could be discerned a primitive killer's instinct, lurking, waiting for the spark that would bring it forth!

The top of its head was swathed in bandages.

Roger knew what he was seeing. It was another man with an empty skull.

But how different it was from viewing a body on a stretcher.

Roger forced himself to return the stare of those eyes. He inspected the face, and recognized it. He had seen Red Dolen's picture. This was Red Dolen.

It was only minutes, but to Roger it might have been hours that he lay that way while Dolen, the Strangler, stared at him with an expression impossible to fathom. And they might have been etched in bronze, for neither moved. Roger felt the sweat running down into his eyes, but he dared not remove his glance from that man who had been turned into an animal by a devilish operation.

And then the tension was relieved by the sound of a cool, precise voice from the doorway. It was Doctor Gassner.

"Have no fear, Mr. Vane. Dolen's murderous instincts are quite under my control. I have no doubt that you recognized him, of course?"

Gassner came into the room and closed the door behind him. He wore rubber gloves and was covered completely by an operating robe. He approached the operating table.

Roger gulped, and forced himself to ask with a semblance of levity, "I suppose I'm the next candidate for your skillful scalpel?"

Gassner put his hands on the table and looked down at his prostrate prisoner. "I regret to say that you are, Mr. Vane. Yours will be my third successful brain removal!" His eyes glittered. They had a trace of madness. "Such operations as have never been imagined by the profession! I experimented much in Vienna. Here I reap the rewards!" He sighed regretfully. "It is too bad I cannot write reports for the American College of Surgeons!"

Roger shrank mentally from the fanatical gleam in those wildly bright, piercingly black eyes. He asked, "Is my—er—operation necessary to your plans, Doctor?"

"It is. Would you be interested in hearing them—before I begin?"

"Nothing would interest me more," Roger murmured. And then fiercely, yielding to the terrible strain on his nerves, "Except getting my hands on your throat!"

There was a slow rustle of motion from the animal-like figure of "Red" Dolen. The strangler shifted in his chair and grunted deep in his chest. His hairy, ugly hands came away from his knees and clawed into talons.

Gassner looked sharply at the man with the empty skull. He snapped his fingers. "Be quiet!" he ordered curtly.

Dolen subsided sullenly.

Roger thought he had detected a little note of apprehension in the doctor's voice. Wildly his mind strove for a scheme. He recalled that Dolen had been convicted of choking a man to death—unnecessarily. His brain seemed to be vainly groping for something—a key to escape. In the meantime he made conversation.

"Why did you help him to escape, Doc? You might as well satisfy my curiosity."

Gassner beamed with pride. He nodded, and said, "Gladly, Mr. Vane. There are so few I can confide in, and you—are safe, now. You see, my plan was of the very essence of genius. First, I offered Dolen his liberty in exchange for the use of his brain!"

Roger started. "The use of his—brain?"

"Exactly. I smuggled a hypo of serum into him in prison, so that he was immune to the gas. Ivan did that when he visited him. Then he drove out of the prison grounds. That was how Ivan spread the gas in the prison. The exhaust of the car was fitted to a tank under the floor boards—a tank of my ethylene-urethane. In that manner everybody was gassed while Dolen walked out, a free man!"

"Marvelous," Roger gasped. "You're a genius, Doc!" He said it, partly to lull the other by the flattery which he obviously yearned for, and partly to cover up the wild light in his own eye. For he had just thought of a wild, impossible scheme to frustrate this madman—a scheme that might well end, though, in his own destruction.

Gassner went on. "That was only a single step. It happened that Courtlandt Spears, the president of the Empire City Bank, was here at the time, for an appendectomy. I timed Dolen's escape carefully to coincide with that. I removed Mr. Spears's appendix. But I went further. I also removed his cerebral cortex!

"Dolen came here from prison. He had enough confidence in my ability as a surgeon to submit to the same operation—with three million dollars of loot in sight!"

Roger looked at Dolen. The recital seemed to be making no impression on the animal part of the brain that he had left. Only in his eyes was there a hint of the smoldering instincts that had finally sent him on the road to the electric chair. Roger turned his head back to Gassner, who was going on.

"And then, my friend, I reached the pinnacle of wizardry in the profession of surgery! I placed Dolen's brain in the skull of Courtlandt Spears! Can you imagine the delicacy of such a transplantation? I had worked for years to perfect a protoplasmic substance which would knit the membranes together. This is what I used.

"The result was that when the president of the Empire City Bank returned to his office, he carried back the brain of a criminal! But the body was the body of Courtland Spears, with all his instinctive reactions. You recall, perhaps, that the cashier noted the birthmark, and that he commented on the signature? Spears was in a position to order the gold shipped out without opposition. It was, my friend, the perfect imposture!"

Roger was astounded. Merely to follow this recital taxed his imagination. But many things became clear.

"So you and your man, Ivan, drove the armored car, eh? Then you drove out to some lonely spot and ran it up the runway into the van. I see it now. That was why it looked as if Spears and the gold had vanished from the face of the earth!"

Gassner nodded enthusiastically. Then he sighed. "But I was careless. When Spears returned, I operated on him once more and removed Dolen's cerebral cortex. I left the operating room unguarded for a moment, and Spears, with the instinct of fear which was governed by his cerebellum, ran out, naked as he was, and fled across the field, to the place where he was found by that ambulance doctor."

"And now," said Roger, "you are going to replace Mr. Dolen's cerebral cortex?"

Gassner leaned closer, his lips a thin straight line of heartless cruelty. "No," he confided. "This is where you come in. I am going to put Dolen's brain in your skull!"

Roger's throat was parched. "But why?" be demanded in a hoarse whisper.

"Because then the renowned, the trusted Roger Vane, special investigator for the Bankers' Protective Association, will escort the van of gold out of the city to the boat I have chartered! Gold, my friend, is good all over the world!"

Incredible as it sounded, Roger knew that this madman could do just what he threatened. He knew, too, that Gassner would destroy him and Dolen after he was safely away. He wasn't going to split that three million with Dolen or anybody else.

This was the time, he decided, to try his almost hopeless plan. He took a deep breath. "I should think," he said, in a loud, sharp voice, "that Red Dolen would choke the life out of you, Doctor!"

Gassner started. His eyes narrowed suspiciously.

From the chair by the window came a low animal growl.

"Yes," Roger repeated, "he ought to get his two hands on you and choke you—choke you!"

Dolen half rose from his chair, eyes glued to Gassner. He was responding to the suggestion.

Gassner was pale. He snapped his fingers. "Sit down, Dolen, you fool!" he barked. The strangler seemed to hesitate. He was deeply under the surgeon's influence.

Roger desperately raised his voice to a shout "Choke him, Red! Get your hands on his throat! Choke him! Kill! Kill!"

Little red spots appeared in Dolen's eyes. He was like a bull before whom a red flag is waved. A low roar came out of his throat. Slowly he rose and walked around Roger's table. A fierce grin spread over his mouth, saliva drooled from the ends. His big hands with the red hair showing on their backs opened and closed with grim deadliness as he made for the doctor.

Roger's voice was hoarse. "Choke! Choke!" he urged in a desperate monotone.

Gassner's eyes distended with fear. He retreated to the instrument cabinet, fumbled behind, and snatched up a keen-edged scalpel. With that in his hand he faced the advancing killer. "Get back!" he croaked. "Get back!"

But Dolen came on, ponderous, inexorable. He needed no more urging from Roger. His open pajama jacket showed the red hair of a heaving chest. His brutish features were contorted into a terrible mask of killing lust. With the bandages of that inhuman operation on his head, he was the ghastliest thing that Roger had ever seen in his life.

Gassner, with his back to the cabinet, lashed out with the steel scalpel, leaving a deep gash in Dolen's chest, from which the blood oozed horribly. But he seemed not to feel it. His hands came up, his fingers encircled the doctor's throat in a terrible grip.

Gassner lashed out again and again with the scalpel, and brought blood in a dozen places. But those implacable fingers clung to their grip. Gassner's face grew purple; he gagged; his eyes bulged. A strangled scream like the bleating of a sheep escaped from his mouth, then he sagged limply.

Roger had been unable to tear his eyes from the awful picture. Now he saw Dolen drop the doctor's body as a child would drop a discarded toy. Then he turned slowly and advanced upon Roger, hands opening and closing spasmodically.

This was what Roger had feared. The killer deep within him had tasted the sweet taste of blood and would not be stopped now. Blood gushed from a dozen wounds left by Gassner's scalpel. The bandage on his head had come askew. But he came on, his murderous eyes feasting on Roger.

Roger squirmed in his straps. He could do nothing but wait for those hungry hands to close on his windpipe.

And then while Dolen's feet brought him slowly closer, Roger heard the doorbell outside ring. As in a haze, he heard Ivan going to answer it, heard a familiar voice saying, "We're canvassing the neighborhood. Did anybody here see a little old guy running around naked? He was found on the Parkway. Came from this direction."

And he heard Ivan's answer as Dolen's claws were reaching for his throat "I'm sorry, sir, I can't help you."

Desperately, Roger shouted. "Up here, Mike! Up here, for God's sake!" His own voice sounded like a stranger's—weird, unnatural.

From the outer hallway came an angry bellow. "Don't call me Mike, dammit!"

Heavy feet in the hallway, the sounds of a scuffle.

Roger's eyes closed against his will. A hot breath was in his face. Dolen's hands were tightening on his throat. "Too late," he thought. Through his head went the refrain, "Too late, too late, too late!"

He gasped for air. Dolen's beastlike fingers were searching under his neck, to snap it. The door of the operating room was locked; he remembered that the lock had snapped when Gassner closed the door. Mike could never make it in time.

"Coming, Roger," Inspector Cummins shouted from the corridor.

Then there was a pounding at the door, and Cummins' voice raised in profanity.

And suddenly a great gust of air swept into Roger's lungs. The fingers about his throat relaxed. A great weight fell on his naked chest. He opened his eyes. Dolen lay across his chest, soaking him in his blood!

Roger breathed deeply, his lungs burning with each intake of air.

A panel of the door crashed in. A hand was inserted and turned the catch. Cummins barged into the room. He stopped short. Two uniformed men crowded in behind him.

The inspector took a look at Roger, then put his hands on his hips and roared with laughter. "Well, Big Shot," he taunted, "I never saw you look so pale before! What's happened here?"

His eyes swept the room, took in Gassner's broken body, and settled on the form of Dolen.

"This guy is Dolen," Roger whispered through a burning larynx. "He finished Gassner, over there, and he was doing the same for me."

Cummins dragged Dolen's body off Roger and started to undo the straps. "What happened to him?"

"He must have collapsed from his wounds, or else he caved in the same as Spears did. He had the same kind of operation. Gassner was our man, all right. He operated on them."

Cummins helped Roger up. Roger flexed his stiff muscles, and looked up to see the inspector grinning at him. He glanced down at himself and flushed. The two cops who had come in behind Cummins snickered.

"Just like Adam," the inspector jeered at him. "Did you forget your clothes?"

"Okay, Mike," said Roger. "Laugh! Go ahead! Give me the ha-ha for the rest of my life. Only get this—my hunch was right! And you'll find the gold in the garage in back of the house. Go ahead and laugh now!"

He had some measure of satisfaction as he saw Cummins scoot out the door for the garage. But the vision of the brainless Dolen with fingers on his throat, still clung to the retina of his eyes. As long as he lived he felt he would never be able to purge himself of the memory of that apparition out of hell!