RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

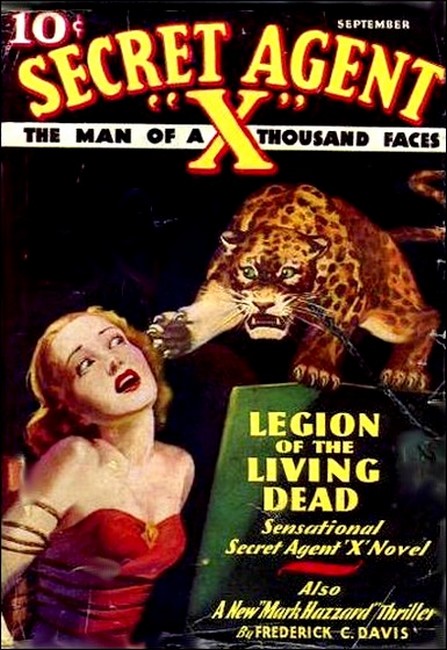

"Secret Agent 'X', September 1935, with "Paid in Slugs"

Roger Barclay had faced death many times—at the point of a gun, in the grip of a strangler's fingers. But now he was to learn what it meant to die—artistically. For the tall, thin man with opaque eyes who towered above him like a snake about to spring boasted that he was an artist without equal—in the fine art of exquisite torture.

Headpiece from "Secret Agent 'X'"

I SAID to the taxi driver: “You better slow up. It's in the middle of this block.”

And then I noticed Helene Rondheim, standing at the curb and motioning desperately to me. The cab driver threw back over his shoulder: “That lady wants you, I guess. Should I stop?”

I sighed. “All right.”

He pulled in to the curb several yards past her, and not far from the house of Mr. Lagurian down in the middle of the block—which was where I was going.

I paid him off and turned to Mrs. Rondheim who had come running over, a bit breathless. The exertion had brought a flush of color to her cheeks, enhancing her dark beauty a thousandfold.

She clutched my sleeve almost feverishly as the taxi pulled away, and exclaimed: “Mr. Barclay! You must not go to see Lagurian!” And she glanced with apprehension toward the house down the street.

I frowned. “Did you purposely come here to waylay me, Mrs. Rondheim, in order to tell me that? Didn't I instruct you and your husband to remain indoors? Some one may see you and follow you back to the apartment.”

She rushed on, unheeding. “Mr. Barclay, you are my husband's lawyer, and you are not paid to risk your life. If you go into that house you—you will be taking your life in your hands!”

I raised my eyebrows. “Surely, Mrs. Rondheim, you don't mean that physical harm will be offered me? What is your purpose in trying to prevent this interview between myself and Mr. Lagurian?”

She lowered her long lashes over her dark eyes, bowed her head. “I—I cannot tell you that—except that you are going into danger. My husband had no right to send you here.”

“He didn't send me,” I retorted hotly. “He merely gave me to understand that there was some sort of feud between himself and Lagurian, and that it is probably Lagurian who is suppressing the evidence that may mean your husband's acquittal when we go to trial. I hardly see—”

She put a long, slim hand on my shoulder, said huskily: “There is more, much more, Roger Barclay. The girl, Mary Consello, whom you have been trying to locate—”

“Yes, yes,” I retorted testily. “Your husband thinks Lagurian is also hiding her so that she cannot testify at the trial. That is ridiculous. However, I owe it to my client to investigate every possibility, and that is why I am here. If Lagurian has those ledgers, I am prepared—”

“You mustn't—you mustn't go there. Please—”

I raised my hat. “I am afraid I am already late, Mrs. Rondheim. If you have nothing better to tell me, I must ask you to excuse me. Please go back to the apartment and do not leave it until I tell you to.”

I left her there, staring after me with the look of one who sees a sacrificial victim going to the altar.

As I rang the bell of Mr. Lagurian's house, I glanced back down the street, and saw her, still standing there in the darkness, looking after me as if she were seeing me for the last time.

All of which, I confess, did not contribute to my peace of mind as the door was opened to my ring.

The Chinese house-boy who admitted me, and who shufflingly conducted me along a dimly lit, quiet hall to the room of his master, did nothing to diminish my disquiet.

His expressionless face betrayed nothing of the thoughts that went on behind those almond eyes of his.

To my surprise, he led me, not into a sitting room or library, but down to the end of the hall and into a blue-walled breakfast room off the kitchen.

At a table under the electric light sat the man I had come to see—Mr. Lagurian. There was an empty orange juice glass on the table, and he was eating dry toast and sipping black coffee.

Mr. Lagurian was a very thin man, and when he arose, I saw that he was also very tall. He wore an embroidered, silk dressing gown over a pair of blue pajamas. He was freshly shaven, and his coal black hair was slicked smoothly back from a high, narrow forehead.

It was his eyes that disturbed me. There was a bit of a slant to them, not unlike those of the servant, and they were opaque, suggestive of an immense force for evil. Doubtless there was more than a touch of the oriental in his ancestry.

He said: “How do you do, Mr. Barclay? You are punctual. Will you join me in a bit of breakfast?”

I glanced at my wrist watch, raised my eyebrows. “At eight-thirty in the evening?”

My tone must have conveyed to him the impression that I thought him a little mad, for his lips curled back in something that was probably intended to be a smile.

“Forgive me,” he said. “I forget that my ways must seem odd to a stranger. You see, my day begins almost when yours ends, I— er—work at night.”

I stood with my hat in my hand, not knowing what to answer. I felt I was going to be at a distinct disadvantage in transacting the buiness I had come to transact with this peculiar man.

He said sharply to the servant, “It is well, Wang Mun. Take Mr. Barclay's hat, and go.”

Wang Mun reached ever deferentially and extracted the hat from my fingers. Then he backed from the room, closing the door behind him.

MR. LAGURIAN motioned to a chair opposite him at the table, and seated himself. “We can talk here while I finish my breakfast—if you don't mind.”

“Not at all,” I said hastily. The sooner I was through with him, I felt, the better I would like it. I sat down facing him. Looking into his eyes, I wished I had brought a gun. There was a hint of mockery in those eyes as he regarded me across the table.

“Now we can discuss our business. Let me see—on the phone you said you were an attorney, didn't you?”

“That is correct,” I informed him. “I represent Mr. Alvin Rondheim, who has asked me to interview you.”

“With what purpose, please?” he asked softly, holding his slice of toast in mid-air and staring at me intently, unblinking.

“I stated my purpose on the phone.” I told him impatiently. “Mr. Rondheim has reason to believe that you have tampered with a material witness. He believes that you have bribed a young lady by the name of Mary Consello to disappear with certain ledgers and records which she had charge of in my client's banking house. Those ledgers—”

Mr. Lagurian interrupted me. He was leaning forward a little now, his toast still poised, the long white fingers of his left hand drumming on the table top. He had the look of a hawk that is about to swoop down upon a victim. “Why hasn't Mr. Rondheim come in person, Mr. Barclay?” His red lips framed each word slowly, clearly.

“You know well enough why Rondheim cannot come himself,” I replied hotly. “There are four indictments against him in the County Court in connection with the failure of his bank. If you read the papers at all, you will know that I have advised him not to surrender himself to the district attorney until we are ready to go to trial.”

“He is in hiding then?”

“If you want to call it that. I have searched all over the city for Miss Consello. She has not been at her boarding house, and her friends have not seen her. Either she has been bribed to leave town, or else she has been kidnaped. The ledgers that she took with her will prove without a shadow of doubt that Mr. Rondheim did not divert any of the funds of the bank to his own use. Until the records are found, my client dares not stand trial.”

I had grown warmer as I expounded the case of my client. Mr. Lagurian grew cooler. He nibbled at the toast, took a sip of the coffee. “Quite so,” he murmured, “quite so. He dares not stand trial.” Suddenly he put down his cup with a bang, and his eyes bored into me.

“Where is Mr. Rondheim at this time?” he demanded.

I frowned. “I came here,” I told him frostily, “to ask about those ledgers, and about Miss Mary Consello; not to answer your questions. Even if I were to admit that I know where he is, legal ethics would forbid my divulging the place.”

Mr. Lagurian appeared to give thought to what I had said. His eyes strayed to a large calendar on the opposite wall, seemed to study it. I was totally unprepared for his next statement.

“Crime, my friend,” he said suddenly, “is an art!”

If he was deliberately trying to impress me, he was succeeding admirably. There was nothing I would have liked better at that moment than to leave Mr. Lagurian's house and give up the idea of acting as intermediary for Alvin Rondheim.

My host's eyes had lost their opaqueness now, and they were glittering like those of a snake preparing to strike.

But I wasn't going to give him the satisfaction of knowing how I felt. I held on to myself and said coldly: “As you know, sir. I am a criminal lawyer of repute. I am familiar with the aspects of crime. I have not come here to listen to a lecture on the subject, but to ask you whether you are holding the person of Miss Mary Consello.”

He nodded as if thinking to himself. “I see that you are a man of courage—or else a fool!” Abruptly he pushed back his coffee cup, and arose. His tall, cadaverous frame towered over me. “I was coming to the question of Miss Consello—but in my own way.”

He rested his delicately veined hands on the table, spoke down at me. “If crime is an art, Mr. Barclay, then you must put me down as a great artist. Few men know how to commit crime in an artistic manner; commit it in such a way that the victim suffers untold agony, dies a thousand deaths—yet can do nothing, nothing, nothing!”

My hands were beginning to get a little clammy. I could feel beads of perspiration on my forehead. I stared, fascinated, at Mr. Lagurian.

And abruptly that thin face of his was contorted in grim lines of passion. He leaned far over the table and said with repressed venom: “Mr. Barclay, there is nothing in the world I want more than to get my hands on Alvin Rondheim. You know where he is. And you are going to tell me—in one way or another!”

I felt my face growing a dull, stubborn red. I am a member of the Bar, and I have always practiced my profession in an honorable manner, to the best interests of my clients. To disclose the whereabouts of Rondheim to this man who obviously meant him harm would have been unthinkable. Many men have retained me as their attorney when in trouble, knowing that their secrets were inviolate with me. I could never face the world if I should betray a trust reposed in me.

Lagurian was watching me, and he must have read my thoughts perfectly. For he said: “It would be better for you to tell me at once. No one will know. And I have ways of—er—making obstinate men less obstinate.”

I pushed back my chair, and stood up, facing him. It would have been a pleasure to take that scrawny throat of his in my hands and squeeze it hard. After all, why not? I was as tall as he, and heavier. I'd been something of a boxer in college, and had also come close to making the All-American one year.

I said: “Since you refuse to give me any information about Mary Consello, I shall leave. Good-night, Mr. Lagurian.”

He smiled thinly, and shook his head. “You are mistaken, Mr. Barclay. You are not leaving—just yet. Pray look behind you, and you will see why.”

I swung about, and started in surprise. I had heard no one enter. I had thought myself to be alone with my host. Yet, unbelievably, there stood, just within the doorway, Wang Mun, the house-boy, together with another high- cheeked, raw-boned North-of-China man. Their arms were folded across their chests, hands hidden in the capacious sleeves of their black jackets. Their almond eyes were fixed unswervingly upon me.

I turned back to my host, and said hotly: “I warn you not to attempt to use force with me. I am not a weakling.”

MY mind was working fast. There might be more than these two in the house. As it was, the odds against me were great, even though I felt quite sure that they would not wish to use firearms; the neighborhood was a quiet, residential one, yet the explosion of a revolver would surely attract attention.

The two Chinese stood impassively in the doorway, and Mr. Lagurian began to speak. But I did not hear what he had to say, for I had decided upon action. If I could move quickly, I might be able to effect my escape. I therefore raised the chair beside which I was standing, took two steps backward toward the window. The blind was drawn, but I disregarded that. I swung the chair above my head, crashed it against the blind, hoping to smash the glass and leap through the window.

Neither Mr. Lagurian nor his two yellow men made a motion to hinder me; and I discovered why. The chair crashed into the blind, but there came no shattering of glass. Instead, a leg of the chair splintered under the impact as it struck something hard, unyielding. I was left standing there, with the broken chair in my hands, looking rather foolish, I expect.

The two Chinamen did not move, did not show by so much as the fluttering of an eyelash, that anything out of the ordinary had taken place.

Mr. Lagurian's red lips were curved into a thin smile. “You see, Mr. Barclay,” he explained softly, “I have steel shutters on the insides of all my windows. I assure you that this house is very difficult to leave—without my consent. You—”

He stopped as the doorbell sounded from outside. Wang Mun glanced at him inquiringly, but he said impatiently: “Disregard it. Ling Sin will answer it.”

We heard the shuffling of padded feet, heard the front door open, and I was about to shout, when it closed almost at once. My hope fled. It must be one of Lagurian's own men.

I gripped my chair firmly. “All right.” I said, and I was surprised at the steadiness of my voice, “I haven't been in a good fight in years. There are three of you, but you daren't use guns. Here's where I break a couple of heads. Yours will be the first, Mr. Lagurian!”

My host raised a deprecating hand. “You are courageous, Mr. Barclay, but, as I observed before, also something of a fool. You have cleverly guessed that it would be—undesirable to use revolvers here. Surely you must understand that I have foreseen that. Let me show you.”

He swung his eyes a little, addressed the Chinese who stood next to Wang Mun: “Wang Lee, today is the first of August. Please indicate the date to Mr. Barclay.” He nodded toward the calendar on the opposite wall.

Wang Lee bobbed his head in a jerky bow. For a half-second he did not move.

My eyes were fixed on him, my hands gripping the chair. I suspected some trick, and I tensed my muscles. Then, as I watched, Wang Lee's hand emerged from his sleeve, flashed up and forward. A knife blade glittered for an instant, and sped through the air so swiftly that my eyes could not follow it. Unerringly the point of the blade struck the numeral one on the calendar, remained there quivering, embedded in the wall.

I shuddered. I was sure that a gun could not have been faster.

Mr. Lagurian said pleasantly: “Wang Lee and his brother are both experts with the knife, Mr. Barclay. If the situation is not yet plain to you, I suggest that you imagine that knife blade being directed at your throat instead of at the calendar!”

I could very well imagine what my host suggested, and it caused me a queer, prickly sensation in the neighborhood of my Adam's apple. I swallowed hard and said: “What do you want, Lagurian?”

He said tensely: “You know what I want—the hiding place of Rondheim.”

I shook my head.

He nodded to the two Chinese, ordered them: “Take him upstairs.”

The Wang brothers stepped toward me. Their hands came out of their sleeves, and I saw that each of them held a knife about eight inches long, with a bone handle. The knives were straight, and tapered to a point. Those points were directed toward me.

I took two swift steps backward, swung the broken chair up again. I was within a foot of Mr. Lagurian now, and on his side of the table. With the chair poised as I now held it. I could bring it down on Mr. Lagurian's head without stretching my arms.

I felt the blood racing to my head as I said: “If those two try to come any nearer, I'll crack your skull, Lagurian. They may get me, but I'll get you, too!”

As I tell it now, it may sound like something heroic. It wasn't. It was purely the action of a man at bay. I knew that once I was helpless in the hands of those two Wangs, there were going to be unbearable things in store for me if I did not reveal Rondheim's hiding place. I might as well die now.

The two Chinese stopped in their tracks. They glanced at Lagurian for instructions.

My host said very, calmly: “I underestimated you, Mr. Barclay. You are a man of resource. It looks like a stalemate. But how long can you keep that chair in the air?”

HE was right. I was out of condition, and my arms were beginning to tire already. I could, of course, bring it down on him now, knock him out. But that would destroy my only protection against the two knife- throwers. From the looks of them, they'd surely send those blades of theirs whizzing into my body.

I made as if to lower the chair, flexed my muscles, and hurled it straight at the face of Wang Mun. He ducked, but it caught him in the side of the head, sent him hurtling into his brother. Wang Lee was thrown off balance, which was the only thing that saved me from a blade in the throat. For he had just flicked his wrist as Mun staggered into him, and the knife which he flung at me missed my neck by a couple of inches.

Wang Mun was still a little dizzy from the blow of the chair, but a fresh knife appeared as if by magic in the hand of Wang Lee, even as he was recovering his balance.

I didn't wait for him to hurl it, but dived sideways into Mr. Lagurian, crashing him into the table, which in turn struck the knees of the dazed Wang Mun.

Lagurian frantically strove to get to his feet, shouting swift, sing-song orders to the two brothers in Cantonese. I took advantage of the momentary confusion which I had created to leap across and push open the swinging door to the kitchen.

I ducked to one side in the darkness here, just as the blade from the hand of Wang Lee sped through the air. The knife struck something that rattled—probably a pot hanging on the wall, and dropped to clatter on a porcelain sink. The door swung shut, leaving me in utter darkness.

I could still hear Lagurian's cold-voiced orders in the next room, knew they would be in here after me in a second. I put out my hand, touched a kitchen table. Upon the table I felt a heavy object. It was a flatiron.

I gripped it by the handle just as the door was pushed violently open, revealing the crouching form of Wang Lee, with Lagurian behind him, holding a flashlight.

Instinctively I raised the flatiron, crashed it against the forehead of Wang Lee. He fell backward, uttering a choked cry, crumpled to the floor, and the kitchen door swung to.

I was unused to such bloodthirsty business, and I stood there in the dark, breathing hard, but with a feeling of exultation which I could never have imagined myself experiencing at the thought of doing violent injury to a fellow man.

However, I did not intend to remain there and do battle with Mr. Lagurian and his retainers. Still clutching the flatiron, I felt my way past the table, along the wall, until I found another door. This was not the swinging variety, and I turned the knob, pulled it open. Through the swinging door, I could hear Lagurian and Wang Mun in a low-voiced colloquy.

I slipped out of the kitchen, found myself in the hall along which the house-boy had conducted me. My one desire now was to get out of this place and go and phone Mr. Rondheim and ask him a couple of very pertinent questions—such as why he hadn't told me what sort of set-up he was sending me into.

I made my way as silently as possible toward the front of the house. Behind me I heard some crashing sounds back in the kitchen, and I surmised that my host and his remaining assistant had pushed through the swinging door again.

I reached the vestibule, and stumbled over something, bent and touched a warm body. My hand came away sticky. I moved a bit so the dim light from the rear would show me who it was, and I gasped. It was a dead man—a Chinaman, and he had been stabbed through the heart. He lay in such a way that I would have to move him in order to open the front door.

I recalled what Mr. Lagurian had said about the difficulty of leaving the place; I also recalled how my chair had splintered against the steel shutter on the kitchen window. And I decided not to try for the front door.

I heard movement in the rear of the hall, turned and saw the head of Wang Mun peering out of the kitchen. When he saw me, he sprang, catlike, out into the corridor, and I saw the flash of his knife blade. He had to get clear into the hall to fling his knife, and in the second that it took him to do that, I hurled my flatiron at him. He ducked, and the iron missed, but it gave me enough time to sprint about six feet back to the staircase which led upstairs.

Before he could set himself once more, I was halfway up the flight. I heard him running down below, heard Lagurian calling after him still in Cantonese.

The upper floor was in total darkness, and I was glad of that, became I heard men coming down from the third floor. There were at least two of them, and one called down, speaking in Chinese.

Wang Mun, who was running up after me, called back excitedly, and the men above started to run down. I was cornered. Wang Mun coming up, the others coming down, all with razor-keen knives, I supposed.

I felt along the wall, touched a door knob, felt a key in the hole beneath it. I turned the key, pushed open the door, and stepped through.

There was no light in the room which I had just entered, but I closed the door behind me after extracting the key from the outside. I inserted it in the keyhole, locked it from the inside, and stood with my back to the door, listening to Wang Mun and the others from upstairs, who had met in the hall just outside, and were chattering away in their sing-song dialect. After a moment, Lagurian joined them, and I could hear his voice, chill with anger. I gathered that he must be rebuking them for having allowed me to escape thus far.

While I listened, expecting every moment that they would try the door behind which I stood, I strained my eyes in an effort to pierce the darkness of the room I found myself in.

Suddenly I stiffened, held my breath.

Clearly, distinctly, I had caught the sound of quick, labored breathing. Someone else was in this room with me!

OUTSIDE the door, the footsteps of the Chinese seemed to recede and then to die away entirely. I could hear nothing from the corridor. And within the room that slight sound of breathing had ceased, as if my entrance had been a signal for silence.

The darkness became oppressive. I expected momentarily to feel a cold knife driving at me. I strained my eyes to pierce the gloom, and gradually I began to discern bulky objects—the vague outline of a bed, a dresser.

I kept my back to the wall, with my elbows spread out on either side of me, to keep a possible assailant as far away as I could.

At last I could stand the silence no longer. I gulped, said in a hushed voice: “Miss Consello—is that you?”

I tensed, my blood racing. If it wasn't Miss Consello, I'd know it soon enough.

But nothing happened. The silence became oppressive. I repeated: “Miss Consello. This is a friend.”

No answer.

I could have sworn that I had heard breathing when I had at first entered. It had given me the creeps then; now I would have welcomed it. I would, in fact, have welcomed anything—even the sound of Mr. Lagurian's Chinese trying to get at me from the corridor with their knives. But there was no noise from the corridor. I couldn't fathom it.

My hand shook as I extracted a book of matches from my pocket, tore one out and lit it. Its glare revealed the small room to me, including the thing that lay upon the bed.

The match burned my fingers, and I hardly felt it; for I had been looking at the body of Mary Consello upon the bed; Mary Consello, lying on her back, white in death, with one of those Chinese knives in her throat!

Mr. Rondheim had shown me her picture, and I knew her—knew her in spite of the way in which fear and terror had distorted her pretty face.

I licked my scorched fingers, and felt behind me for the light switch, clicked it on.

My eyes searched the rest of the room quickly for the murderer, but there was no one. The room was empty save for myself and the dead body of Mary Consello.

I stepped closer to the bed, steeled myself, and touched her cheek. I drew my hand back quickly. She was still warm. The terrible truth impressed itself upon me. It was she whom I had heard breathing just before. She had died while I crouched there in the darkness. It was her death rattle I had heard.

She was dressed in a trim little tan sports suit, with tan stockings and shoes to match. The jacket of the suit was torn open at the throat where the killer must have gripped her before driving home his merciless blade. Thick red, clotted blood stained her soft, white flesh.

I moved backward in revulsion. My pulse throbbed more in anger than horror. But I felt violently nauseous.

My eye fell on the open fireplace at the left. Scraps of burned paper lay there. Even before I bent over them, I knew what they would be. There were the covers of several ledgers that had not yielded to the fire. The gilt lettering showed plainly: “HURON TRUST COMPANY, Loan Account.”

The pages had been torn out and burned. Nothing was left but the gutted binders of the books. These were the ledgers that Rondheim and I had been searching for—they were the books that Rondheim had told me he needed in order to establish his innocence. They were destroyed now.

Mary Consello, who had worked in the bank and could testify to all the transactions, was dead; the ledgers were destroyed. Mr. Lagurian must have been laughing up his sleeve at me all the while that he was talking to me downstairs.

I started as the bell downstairs burst out into a loud jangle. Someone was at the front door.

I waited tensely for Lagurian's servants to answer the bell. I wondered vaguely if they had moved the body of the dead Chinaman from the hallway. I wondered if I might chance a quick rush downstairs while the front door was being opened.

With that in mind, I cautiously opened the door of the room, casting a single backward glance at the still body of Mary Consello. I peered out into the corridor, saw no one. The light from the room illuminated the corridor, showed me it was empty.

I couldn't understand that. Lagurian's Chinese should have been here, breaking down the door, coming after me. Were they so sure that I was helpless in their power that they were waiting for me to come down to them?

I glanced down the stair well, toward the front door. The body of the Chinaman still lay there, just as I had seen it before. But no one came to open the door.

The bell rang again, this time more insistently. And a voice shouted:

“Open up in there, or we'll smash in the door! This is the police!”

I heaved an immense sigh of relief. I called out in a loud voice that must have been a little shaky:

“Smash it in. It's locked. And be careful. There are murderers in this—”

My voice died away, and I felt a sort of freezing process taking place within me. For I had distinctly heard a footstep in the darkness behind me.

I started to turn around, and a dark body crashed into me. I could feel hot breath on my cheek; my hands went out blindly in the dark, clutching at my unseen assailant. I felt a throat beneath my grip, began to squeeze—and something hit the side of my skull like a meteor. A terrific pain shot through my head, and I was sinking to the floor against my will.

Like those of a drowning man, my swiftly numbing fingers clawed wildly at the air, and I felt my fingernails raking my assailant's skin; the nail of my index finger broke against his stiffly starched collar. Another blow descended on my head, and I could keep my senses no longer.

The last thing I heard was the shouting of the officers outside: “Shoot the lock in, boys—” and then everything got blank for me.

WHEN I came to, I was on a couch in one of the downstairs rooms. I could tell by looking out into the hallway to the front door which was a wreck.

The room was filled with newspaper reporters and police, and I smiled faintly at Assistant District Attorney Gross, whom I knew quite well. It was he who had charge of the prosecution of my client, Alvin Rondheim.

Gross was a little, stocky man with a bald head and eyeglasses, and he carried himself with quite an air of importance. I knew that his secret ambition was to be governor some day.

He was standing over me now, and his stenographer was just a little behind him, with notebook ready.

Charley Holmes, from the Daily Tabloid, asked eagerly. “What happened in here, Mr. Barclay, after you called to the police? Who socked you?”

Gross turned on him, frowning. “Since when have you become District Attorney, Holmes? Be so good as to let me do the investigating here!”

Holmes grinned insolently, winked at me, but kept quiet.

I got to my feet, a little wobbly, but thinking fast for all that. I said to the D. A.:

“Look here. Gross, this is tied up with the Rondheim case, and it's damned fortunate that you came out on this call. That dead Chinaman in the hall—”

Gross stopped me. “What dead Chinaman?”

I said: “The one you found at the front door. What did you do—move him?”

Captain Snell of the Homicide Squad looked queerly at me. “There wasn't any such thing. Barclay. That sock on the head must have been harder than the doctor thought—”

I exclaimed: “Listen, that Chinaman was dead—I can trust my eyesight. I suppose the next thing you'll be telling me is that you didn't find Mary Consello up there with a knife in her throat.”

Snell nodded somberly. “We found her, all right.”

Gross pushed forward. “That's what I want to question you about, Barclay. Who killed her? What's been happening here?”

“Nothing, at all,” I said bitterly, “except that this man, Lagurian, tried to have his Chinese knife-throwers murder me, and I got away from them up into that room, and found Mary Consello dead. Then I heard the police downstairs, and when I came out in the hall, some one hit me on the head. Did you catch Lagurian and the Chinamen?”

Snell shook his head. “There's not a soul in the house, Mr. Barclay. There's a cellar door open downstairs—they might have got away through that while our men were breaking in the front way. The crew of the squad car didn't think to watch the rear of the house. They were just answering a phony telephone call into headquarters to the effect that some one was killed here. They thought it was a hoax till they heard you shout.”

I took a couple of steps, feeling none too steady, and said: “Mary Consello was the only person whose testimony could have helped Rondheim. She's dead. The ledgers that were stolen from the Huron Trust Company are burned.” I gripped Gross' coat lapel.

“I want your men to leave the papers upstairs in the fireplace alone till I can get somebody up here to photograph them. When Rondheim's case comes to trial, I'm going to show those photographs to the jury, and that will permit me to get in Rondheim's testimony as to what was in the ledgers.”

Gross' stenographer and the reporters were writing as fast as we were talking. Charley Holmes looked up from his notes with a gleam in his eye.

“That's clever stuff, Mr. Barclay. No jury will convict Rondheim in the face of the story of how Miss Consello was murdered.”

“That's right,” I said smugly. “Lagurian planned to leave my client in a bad spot, but he didn't realize he was providing me with first class legal ammunition.”

Gross broke in impatiently: “Never mind the legal ammunition. I'll ride Rondheim if I have to spend a million dollars of the state's money. You think because you're Roger Barclay, you can get away with anything!”

Charley Holmes interjected slyly: “He hasn't lost a case yet, Mr. Gross. That's more than we can say for the D. A.'s office!”

I tried to change the subject. “I've got to go now, Gross. You ought to work on this murder case now. Find Lagurian, and you'll have a murder conviction in the bag. I promise not to defend him.”

“Sure,” said Charley Holmes. “It'll get you a hell of a lot more publicity. It's first class murder cases that make governors out of district attorneys!”

I went out under the baleful glare of Gross, who threw after me: “Be down at my office at nine in the morning without fail. I'll want to take you before the Grand Jury. We'll indict Lagurian in record time.”

He was already thinking of the headlines with his name in them.

“It'll be a pleasure,” I told him grimly.

WHEN I got out on the street there were several press and police cars, and a crowd of loiterers. I looked for a cab, but turned as some one tapped me on the shoulder.

It was Charley Holmes, and he was grinning.

“What's funny?” I asked, frowning.

“Take a look at yourself when you get a chance,” he told me, “and you'll see.”

I put my hand up to my head, and flushed. I must have been a pretty awful sight, with that bandage tied all around me. I pulled it off, and Charley glanced at the side of my head, said:

“You'll do. There's a small patch of adhesive, and the doctor must have shaved off more hair than he needed to, but it's not so bad.”

He took my arm. “I'll walk you to the corner. You won't be able to get a cab here anyway, and I want to talk to you.”

I walked down with him silently, expecting him to ask me for an exclusive interview with Rondheim or something1 like that. He startled me by saying:

“You've got to pull me out of a jam, Mr. Barclay.”

I raised my eyebrows. “Don't tell me you need a lawyer, Charley.”

“I may.”

He pulled something bulky out from under his coat, where he had been holding it with his elbow. We were well away from the house of Mr. Lagurian by now, yet he looked about him guiltily before showing it to me.

He grinned as he saw my look of amazement. The thing that he was showing me was a small account book, about eight and a half inches long by six inches wide. It was made of expensive tooled leather, and was equipped with a small, silver plated padlock. It was the kind of fancy thing that is made to order for the personal use of important executives, and in fact it bore on the face of it, in gold letters, the inscription:

“Personal records of

MR. ALVIN RONDHEIM

President

HURON TRUST COMPANY”

I gasped: “Where did you get that?”

“That's what you've got to help me out on, Mr. Barclay. I got here right after the squad car, and I looked around in the room where Mary Consello was found. Well, this book was up on the top shelf of the closet. Whoever burned the rest of them must have overlooked this. I figured if the police got this, they might kind of mislay it by accident, you know, and that would about finish Rondheim. You've always given me a break, so I thought I'd return the compliment and hold this out for you. Here it is. But you've got to cover me up, or I'll be in one hell of a jam with Sneil and Gross. They'd bar me for the rest of my life if they found out.”

I took the ledger from him. “Charley,” I said, “you've made me ten years younger. There's nothing I wouldn't do for you right now.”

“Okay, Mr. Barclay, take me with you, if that's the way you feel about it.”

I tried to look blank. “Why—”

“Aw, lay off. Mr. Barclay. You're probably making tracks back to Rondheim's hideout to tell him what happened. Take me along, give me an exclusive with him. It'll knock the competition silly.”

I hesitated.

“You don't have to worry, Mr. Barclay,” he urged. “Nobody can make me talk. I'll never give away his hiding place till you're ready. The worst they can give me is thirty days for contempt if I refuse to talk.”

I said: “I'll tell you what, Charley. The day before I'm ready to bring him in for trial, I'll take you to see him. I give you my word on it.”

Charley glowered. “That's a bargain, Mr. Barclay. And I hope you find enough in that ledger to knock the props out of that swell- headed Gross baby.”

I said dubiously: “It's a self-serving document, Charley, and as such it is not admissible as evidence in a court of law. However, if the entries were made by Mary Consello, I could get it before the jury—”

I stopped to flag a cab that had just swung around the corner, but Holmes wouldn't let me get in.

“Wait a minute, Mr. Barclay. Hold the cab here. There's something else I want to show you.”

He dug into his inside pocket, pulled out a sheet of paper that had evidently been torn from some kind of scrap book. It was heavy brown paper, and a yellowed newspaper clipping was pasted to it.

“I did a little more snooping while the cops weren't looking,” he explained, “and I found this in a book of clippings on the desk in the library. I was almost caught tearing it out. This will interest you if you don't already know it.”

The clipping was from the Paris Tribune of May 11, 1928, and read as follows:

Mrs. Helene Lagurian today filed an action for a bill of divorcement from her husband, Sundelius Lagurian, in the Superior Court of the 8th Arondissement. Mrs. Lagurian, who is a resident of Chicago, instituted the action one week after her arrival in Paris. It is rumored that upon securing the final decree, she intends to marry the well known American banker, Alvin Rondheim, who has been at her side during her entire stay in Paris. The suit, of course, is uncontested.

A number of things became very clear to me with the reading of that item. I said:

“Charley, if you ever lose your job on the Tabloid, I'll give you one investigating for me.”

He grinned. “That isn't all, Mr. Barclay. Do you happen to know how Lagurian—and, for that matter, your client Rondheim, made all their money in the first place?”

I shook my head. “I assumed they had made it in their respective lines of business. I had never known Mr. Rondheim until he retained me in this case. It is true that the district attorney has been very unwilling to show me his files on the case. Perhaps—”

“I'll tell you,” said Charley. “Lagurian and Rondheim got rich in China, selling contraband arms to the revolutionary forces. There's been a story going around that they came back from the orient hating each other bitterly. It seems that Lagurian double-crossed Rondheim by tipping off a certain war-lord in Kwan-tung Province about a shipment of arms, and Rondheim was captured. He only escaped death by a miracle. They've been gunning for each other ever since, and it's no fooling, either. Lagurian is still in the gun- running business, though he's supposed to be an importer. There's always a half dozen Chinks in his house.”

“I know,” I said bitterly. “I met some of them.” My mind was working fast. What Charley Holmes just told me made me see why Lagurian should want to wreck my client's chances of acquittal. Rondheim took his wife away in Paris.

Charley chuckled. “Wait'll tonight's paper carries that story splashed all over the front page. Will Gross be sore! He's still hunting for a motive, and here it is, in black and white—Lagurian never forgave your client for taking his wife away from him, so he kills the only witness that will clear Rondheim, and destroys—or thinks he does—all the records that might help him in the trial!”

I nodded doubtfully. From what I had seen of Lagurian, I judge he was too smart a man not to have seen that the very fact of Miss Consello's being murdered would give me a powerful edge with any jury, would, in fact, almost ensure Rondheim's acquittal.

I said nothing about that to Holmes, however, but got into the cab, clutching tightly to the ledger. I waved good-by to Holmes, told the cabby: “Drive uptown to the Bronx, and then go east to Pelham Parkway.”

I saw that Charley Holmes was straining his ears to get the address, and I spoke loudly enough for him to hear.

When we were a block or so away, I tapped on the glass, told the driver: “Never mind about Pelham Parkway. Take me to Eighty-sixth Street and the East River.”

TWENTY minutes later I was on the way up in the elevator to the penthouse apartment where Rondheim was staying till I would be ready to produce him. It was the apartment of a friend of mine who was away for the summer, and I had gotten the rental of it for my client for a short term, completely furnished.

I had advised them not to employ any servants, to send down to one of the restaurants for their meals, and Mrs. Rondheim herself admitted me. I looked at her with new interest in the light of the knowledge I had gleaned from the Paris Tribune clipping. She was attired in a charming, silky negligee, and she seemed a bit startled to see me—though she had first inspected me through the little grilled peephole in the door.

I tried to act as if I didn't know any more about her past than I had known earlier in the evening. I said:

“Good evening, Mrs. Rondheim. I hope I didn't get you out of bed.”

She forced a smile, wrapping the negligee closer about her.

“Not at all, Mr. Barclay. Alvin and I were—er—discussing some matters.” She made no reference to our earlier meeting, and I guessed she hadn't mentioned it to her husband.

I noticed now that she seemed strained, under the influence of some sort of tense emotion. Perhaps I had interrupted a family quarrel.

She led me into the living room, and Mr. Rondheim arose to greet me. He was fully dressed, and puffing one of his huge cigars, as usual. I had never seen him without one.

He eyed me curiously. “You look like you've been to war, Barclay. Who hit you on the head? I hope—”

He stopped, gulped, and flushed as he saw the ledger I was carrying. He pounced on it, studied the gilt lettering. “This is one of my books!” he fairly shouted. “Where did you get it?”

“It was found in a room in Mr. Lagurian's house,” I told him. “The others are all destroyed. Who made the entries in this one?”

“Mary Consello,” he informed me. “But tell me—what happened at Lagurian's house?”

“You must prepare yourself for a shock, Mr. Rondheim. Miss Consello is dead.”

If Mr. Rondheim felt much emotion at the news, he did not show it. I hadn't seen him show much feeling even when he learned that he was indicted by the Grand Jury. He was in his late forties, and of a naturally swarthy complexion. As a banker he must have developed the knack of keeping a poker face.

But Helene Rondheim was made of weaker stuff. She uttered a quick, nervous cry, and would have fallen if I had not sprung to her assistance. I led her to the couch, deposited her there gently.

Mr. Rondheim did not move to help me, though obviously it was a husband's business to take care of a fainting wife.

But Mrs. Rondheim didn't faint after all. She shuddered, and raised her long black lashes. “I—I'll be all right, thank you, Mr. Barclay.”

I turned to my client. I was feeling vaguely irritated toward him.

“Now,” I said, “we can get down to business. Let's see what that ledger shows. Have you got the key?”

Rondheim was turning it over in his hands. “No,” he said, vaguely. “I can't seem to remember where it is.”

Mrs. Rondheim broke in nervously: “Why, of course you have it, Alvin. Don't you recall having a duplicate made in case Mary should lose the original? It's right on your key ring.”

Rondheim frowned at her. “I wish you'd leave us alone, Helen. I want to discuss some matters with Mr. Barclay.”

She arose from the couch reluctantly, and there was almost something like fright in her eyes. “I—I'll be in the music room,” she said.

We watched her as she moved gracefully to the door. Before leaving, she turned and looked at me—in much the same way as she had done before I had disregarded her advice and entered Mr. Lagurian's house. I was puzzled, but said nothing.

When the door had closed behind her, Mr. Rondheim crossed the room and seated himself at the small walnut desk which stood near the window. He placed the ledger upon the desk, and looked up at me.

“You don't need this ledger to get me acquitted. Barclay,” he said. “With Mary Consello dead, the jury will guess that her testimony would have cleared me.”

“You're right about what the jury would believe, Rondheim—provided this ledger had also been destroyed. But the jury will want to see the one book that was preserved—”

“Provided—” he interrupted me with a sly look— “provided we tell them it was preserved.”

I flushed. “If you're suggesting that I connive at suppressing evidence—”

“Wait!” he stopped me, holding up his hand. “How much am I paying you to defend me in this case?”

“You know very well how much you're paying. You gave me a retainer check of ten thousand, and you're to give me fifteen thousand more before going to trial. The fee is twenty-five thousand altogether, win or lose.”

“Very well, Barclay. I'll double the fee, and we'll forget about this ledger. The additional twenty-five thousand ought to salve your conscience as far as suppressing evidence is concerned.”

I restrained my anger, and shook my head in as dignified a way as I could. “I don't practice law that way, Rondheim. I either get you off in a legitimate way, or I don't handle the case. I don't understand your attitude about the ledger. You were eager to locate it—you said it was one of the books that would clear you. And now—”

“Let us go no further, Mr. Barclay. I think I can find a lawyer who will play my way. I'll give you a check for fifteen thousand more, and you can withdraw from the case. That ought to satisfy you, eh? Just let me keep the ledger.”

HE opened the drawer of the desk to reach for his check book, but I halted him. “Sorry, Mr. Rondheim, but I can't do that either. The ledger was found under circumstances which make it the temporary property of the law. A girl has been murdered, and there may be something in that ledger which will aid the district attorney. Even if there isn't, it must be shown to him. My thought in bringing it here first was that we might have a look at it to determine its value to ourselves, perhaps have photostats made of the pages so as to use them in the trial.”

Mr. Rondheim seemed to be thinking that over.

Finally he asked me: “The district attorney doesn't know about this yet?”

“Not yet,” I told him.

Mr. Rondheim heaved a sigh. “In that case—” his hand slid into the drawer and emerged with a small nickel-plated automatic which he pointed at me—“in that case, Barclay, he will never know!”

I looked into his suddenly hard countenance, and exclaimed:

“What are you going to do, Rondheim?” What I saw in his eyes was distinctly a shock. I read there a ruthless purpose that was almost terrifying.

“You are a fool, Barclay,” he said. “I offered you fifty thousand dollars. Now all you are going to get is a slug through the heart.”

I began to laugh nervously. “You are the one who is the fool, Rondheim. Instead of being tried for larceny, you would be tried for murder. You can't just shoot me in cold blood—”

He smiled thinly. “Not in cold blood, Barclay, not in cold blood. I will be very angry and excited. You see, I have just come home, and found you together with Helene—and Helene is in negligee, to bear out my story. Imagine my anger. And what do you do? You draw a revolver.”

He reached further into the same drawer, pulled out another weapon, which he placed upon the desk.

“This will be found in your hand. You see, Barclay, I will have killed you in self-defense. Do you understand? You yourself, as a criminal lawyer, would undertake to get me off scot free, wouldn't you?”

I understood very well. I tried to bluster: “Your wife would never support that story!”

“My wife, Mr. Barclay, will be dead, too. You will hare killed her, by accident, in firing at me!” He said it softly, almost triumphantly. Then he added, still keeping the automatic pointed squarely at me: “Can you find any flaws in the plan?”

I couldn't take my eyes off the mouth of his gun. “No,” I said a bit dully. “No. I can't find any flaws. But why do you bother to explain?”

“Because, Mr. Barclay, if a clever criminal lawyer like yourself can't find any flaws, neither will the district attorney. And now, my friend—” the automatic moved up significantly, and I heard the ominous snick of the safety.

“Wait!” I exclaimed desperately. The gun stopped moving, he raised his eyebrows inquiringly.

“Do you mean to tell me,” I demanded, “that you're going to kill me and kill your wife too, merely because you want to keep the existence of that ledger secret?”

He nodded. “Also, Mr. Barclay, because my wife knows too much about me.”

“Then the ledger wouldn't clear you?”

“No. The ledger wouldn't clear me.”

“I see. The other books wouldn't have cleared you either. Mary Consello's testimony wouldn't have cleared you. You never wanted to find Mary Consello!”

“I did. I wanted to find her before the district attorney's office found her. I knew she had gone to Lagurian with the books and her story, and I knew also that Lagurian would keep her there. He wouldn't be satisfied to let the law deal with me. He hated me in a different way.”

“Yes, I know,” I told him. “You took his wife away from him.”

“Yes. Not because I loved her, but because I hated him. I wanted to hurt him badly. And he loved Helene.”

HE leered at me, and in his eyes there was a gleam of spiteful hate that almost approached fanatic madness. I shuddered at this raw glimpse of the man's soul that was revealed in his eyes.

I stared at him, hardly crediting the depth of his passion; and suddenly I noticed something that had escaped me all this time—something that I had been seeing ever since I had come into the room, but the significance of which just drove home at me:

There were two long scratches on the left side of his neck!

And there were flecks of blood on his collar.

I took a step closer to the desk, almost forgetting that automatic in his hand.

“You killed Mary Consello!” I fairly shouted at him. “It was you who rang the doorbell while I was in there arguing with Lagurian. You stabbed the Chinaman. You burned those ledgers—only you did it hastily, and you overlooked this one!”

He kept nodding his head at each, accusation of mine, smiling in hateful triumph.

“That is so. Lagurian's boy, Wang Mun, was in my pay. I knew he had the girl there. Wang Mun gave me the plans of the house, and he was supposed to open the door for me, but when the other boy appeared, I had to stab him.”

I was gazing at him as one might who suddenly awakens from a gruesome nightmare only to find that the nightmare is true. “So it was you who made the phony telephone call to headquarters. You planned to incriminate Lagurian and at the same time turn the murder of Mary Consello to your own advantage at the trial!”

He continued to smile. “You are very clever. Barclay. It's a pity you have to be so—ethical.” He sighed in mock regret. “You are too honest to live.”

I saw his hand tauten on the automatic. I could almost feel the slugs tearing through my body.

And then the buzzer sounded at the rear of the apartment, at the tradesmen's entrance.

He frowned. I uttered a gasp of relief.

We both remained as we had been—I standing, he sitting at the desk with the automatic trained upon me.

Helene Rondheim's footsteps sounded as she went through the corridor to answer the buzzer.

She called through the door: “It must be the waiter from the restaurant with our supper.” She was passing the door of our room, but the door was closed, and she could not see us.

I raised my voice, called out: “Mrs. Rondheim, for God's—”

But Rondheim rose, reached across the desk, and whipped the barrel of his pistol along the side of my head. He had moved so quickly that I had not had time to duck out of the way.

I staggered backward, and the room swam. His blow had been vicious, and it had served its purpose. I was half stunned, could not finish my warning.

Vaguely, as I clutched at a chair for support, I heard him call out: “Tell the waiter to leave the tray in the hall. When he goes, come in here.”

I wiped the blood which had started to run down the side of my face, raised my head. He had come around in front of the desk, and the automatic was less than a foot from my heart.

But I disregarded it, called out: “Mrs. Rondheim! He means to kill you!”

I thought I was going to be dead in a moment, for Rondheim's face was a vicious mask of fury. But he didn't shoot.

For Helene Rondheim had already opened the rear door, and we heard her utter a cry of terror, heard a scuffle out there. The door of our room was thrust open, and Rondheim swung away from me to face Mr. Lagurian who stood there with a gun in his hand. Mr. Lagurian was no longer the suave, self- contained man who had held me prisoner in his house.

There was a fanatic gleam in his eye, and he was breathing hard.

He said: “Thanks, Barclay, for leading me here. I knew you'd be coming to see your—client!” All the while his eyes were on Rondheim, sparkling dangerously. “And now, Mr. Rondheim, we can settle—”

He had wasted too much time in talking. Rondheim fired from his hip, and he kept his finger on the automatic while eight slugs buried themselves in Lagurian's body. The whole thing took less than a minute, then the noise and the shooting were over.

Mr. Lagurian's face was contorted in astonishment as his body sank slowly to the floor, He jerked once, then sprawled on his back across the threshold, and lay still. His jacket was all bloody.

Rondheim turned on me, snarling like a beast. He knew his gun was empty, and he started to swing at me with it.

I was dazed by the spectacle of sudden death, but instinctively I blocked his blow with my left arm, jabbed him hard in the face with my right.

He went over backward, awkwardly, and landed on top of Lagurian's body. I saw his hand go out, and touch the gun Lagurian had dropped, saw him grin viciously as he gripped it.

I had never thought myself capable of such quick thinking, such swift action. I reached over, snatched up the revolver from the desk—the one he had planned to plant upon my dead body—and I fired it at Mr. Rondheim's face.

The report of the revolver mingled with the bark of the gun Rondheim had picked up. Rondheim had had to twist about to shoot at me, while I had fired almost pointblank.

I saw Rondheim's face disappear as the slug tore through his head. He was hurled violently backward, and lay, horribly bloody, upon the body of the man he had killed.

I threw the revolver from me in revulsion, clung to the desk for support.

Mrs. Rondheim appeared in the corridor, staring with fascinated eyes.

She raised her eyes to mine, and I thought I saw infinite relief in them.

“Madame,” I said insanely, “I am afraid you are a widow—and I no longer have a client!”