RGL e-Book Cover, 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover, 2018©

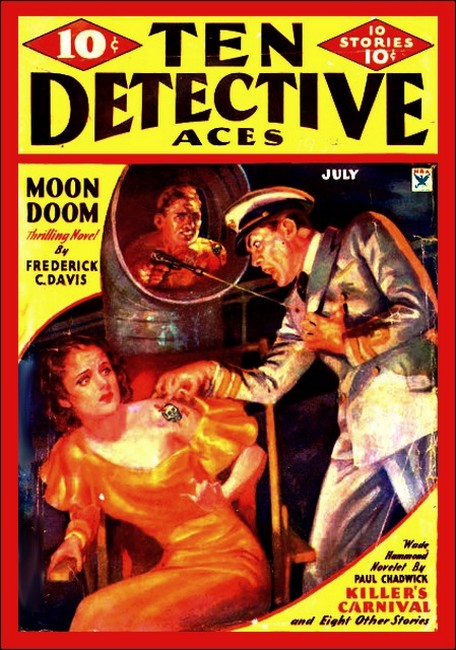

Ten Detective Aces, July 1934, with "Coffin Cache"

Marty Quade, private dick, gets a kidnap job to run down. His manhunt is tangled with double-crossing gunners—and ambitious cops who resent his taking over the case. Marty plunged down Murder Row, but was checkmated at the—Coffin Cache.

IT was an open trolley car, and Marty Quade had shoved over to the middle of the seat to escape the heavy slantwise rain that lashed in.

He spread his evening paper open and made a pretense of reading. He grinned. He had got in the last seat of the car, and the man in the belted overcoat, who had followed him from Raynor’s house, had had to take a seat farther front. The man was fidgeting around now, making believe to look out into the night, but in reality trying to keep an eye sidewise on Marty. Marty took out the package of twenty-dollar bills. It had rested in the right-hand pocket of his coat. That was no place for it. He stuffed it into the left-hand coat pocket. It was surprising how small a package fifty thousand dollars in twenties could make—the whole thing was six inches square; and there were twenty-five hundred of them.

Marty had manipulated the change of the package while still holding the paper in front of him. Now, he slipped the automatic out of the shoulder clip and laid it loose in the right-hand coat pocket.

The man in the belted overcoat had given up trying to keep tabs on him, and was facing forward. He wore a soft hat like Marty’s, and the coat, though of the same style, was of a much cheaper quality.

The car bowled along Boulevard Avenue, and Marty, peering out at the signposts, saw that Waverly Street was only a couple of blocks away. He put his paper down, and just before reaching the corner, he got up and yanked once at the bell cord. The car slowed up, and Marty jumped off the running board.

He turned up his collar and bent his head against the rain, crossed to the curb, and stopped under the street light for a second. The trolley rumbled away.

Marty started up Waverly, but took only two or three steps, then ducked back and peered around the corner. The trolley had reached the next crossing. The man in the belted overcoat got off and started to hurry back toward Waverly.

Marty stepped into the doorway of a jewelry store. It was after eight, and the store was closed. He heard the feet of the man who had just got off the trolley. They came up close to the corner, hurrying, then slowed, approached cautiously.

They didn’t come around the corner, but crossed the street diagonally.

Marty risked a glance, and saw his man entering the lighted drug store opposite. He waited a minute, then crossed over and looked in through the plate glass. The clerk was behind the counter. No one else was in sight. Marty went .in. The clerk looked at him brightly, then turned away in disgust when he saw that Marty was headed for the telephones.

The first booth was occupied by the man in the belted overcoat. He was talking sharply into the mouthpiece, with his back three-quarters to the door.

Marty lowered his head, and slipped past into the second booth.

The other man’s voice came to him pretty clearly through the so-called “soundproof” wall. He had apparently just got his number, and was saying, “Oppenheim! This is Joe Wurtzel. Quade is on the way over with the dough. He just got off the car as per instructions. He ain’t followed, I made sure o’ that. You’ll know him all right—he’s wearing a soft hat and a dark belted overcoat like mine. Better snap it up—it’s only two blocks, an’ he’s got a long stride. I’ll follow him down. So long, see you right away.”

The man hung up and left the booth. Marty waited a minute, then came out after him. He looked out of the store window, and saw the man crossing the street.

Marty killed time in the store, stopped at the counter to buy a couple of cigars. The clerk said, trying to be funny, “It’s kind of wet out tonight, ain’t it?”

Marty took his change, lit one of the cigars. He said, “Yeah. Wet.”

He came out on the sidewalk, frowning at the cigar.

He crossed over, followed after Wurtzel, who was already part way down Waverly. Marty hugged the building line, saw the other reach the end of the block, cross over, start down the second block, bending into the rain, collar turned up and shoulders hunched.

Marty spat out a leaf of the cigar, made a face, flung the rest of it away. The rain was coming down pretty fast. Marty put his right hand in his pocket to keep it dry. He couldn’t do the same with the left, on account of the money package. He walked a little faster, got a little closer to his man. His own feet made no sound, but Wurtzel’s made a sort of plopping noise with each step, as if there were holes in the soles of his shoes.

They were getting close to the river, now; the row of four- story houses had ceased, their place being taken by bulky warehouses that lined the street, bleak and uninviting.

Wurtzel was walking along uncertainly, as if puzzled.

Marty was less than fifty feet from him when the car came around the corner from River Avenue, swung into Waverly, and approached them with the brights on. Wurtzel seemed a little confused, stopped, and started to wave. But he never finished the gesture, for the car came abreast of him at that moment. A short length of muzzle with an ungainly contraption on the end was stuck out from the rear window; a single long streak of flame jetted from it to the accompaniment of a nasty plop.

Wurtzel took the slug full in the chest. He must have been dead while still on his feet. He toppled over in a manner so ludicrous that it seemed unreal—like a movie killing.

The rifle was withdrawn into the interior. The car swept past the dead man, braked alongside Marty.

Marty stood still, a half-grin on his face. His eyes, slate- gray and narrowed, gleamed over the tip of the turned-up collar. He slipped the safety off the automatic, held it in his pocket.

The driver of the car leaned out, shouted, “Get the dough off him, Wurtzel—what the hell you waiting for? Goldie’ll cover you with the rifle.”

Marty saw a dim figure in the rear of the car. The rifle came out again. The one who held it poked a thin face out after it. The face had a pointed chin and two little black eyes. “Speed it up,” the one with the rifle said. “Don’t worry—if anyone comes along I’ll give it to him the same way!”

Marty kept his face buried in the coat collar. He went over to the body of Wurtzel, knelt beside it. He pretended to fumble with the pockets of Wurtzel’s coat, and managed to slip the money package out of his own coat pocket. Then his hands worked fast, going through the rest of Wurtzel’s clothes. There was a wallet containing four or five singles. He left that, but took a notebook and several slips of paper with scrawled memoranda.

From behind him came the impatient voice of the driver: “Step on it, Wurtzel. What you doin’—sayin’ a prayer over ’im?”

Marty had kept his back to them so as to screen his movements. They were quite a distance from the street light, and there was little chance of the two men in the car seeing his face if he kept it down in the coat collar.

Goldie, the one with the rifle, laughed thinly, sharply. “Nicky’s gettin’ shaky. You better hurry up. You got the dough, ain’t you?”

Marty put his right hand in his coat pocket, and stood up. He turned and started for the car.

Goldie had the rifle muzzle pointing out, in his general direction, but made no move to open the door for him. The driver was facing back toward him, and had a gun in his hand.

Goldie stuck a hand out of the window, alongside the rifle muzzle, and said, “Give us it.”

Marty handed him the package. He was taut, on the balls of his feet, his big shoulders hunched a little forward.

The package disappeared inside, then the rifle muzzle swerved a couple of inches, and pointed right at him. The sharp voice of Goldie said, “Sorry, Wurtzel. Oppenheim said to do this.”

At the same moment, Marty’s left arm swung up and brushed the rifle barrel aside. It exploded. The slug sent a shower of plaster cascading from the wall of the warehouse.

And Marty had his automatic out almost with the flash of the rifle, and fired once at the face of Goldie. The rifle clattered to the sidewalk, and Goldie’s face disappeared. Marty swung his gun in a short arc—and shot Nicky, the driver, just as he was lining up his gun. The gun exploded in the car, and Nicky was jarred backward against the windshield.

The shooting had made a lot of noise.

Marty slipped the safety catch on again, put the automatic back in his pocket, and opened the rear door. He poked around a minute, pushed Goldie’s body over, and picked up the money package from under him. Then he closed the door and raced down the street toward the corner. As he turned into River Avenue he heard the scream of a radio-car siren from the direction of Boulevard Avenue.

There was a coffee pot in the frame building around the corner, and Marty stuffed the bundle of money back in his pocket, went in.

There were no customers, only the counterman, a bull-necked sort of fellow, with a face that had seen a lot of battering in its day. There was a scar on the left side of his forehead where a cut had been sewed a long time ago, and he had a nice new shiny set of upper teeth—too even and white to be his own. He looked at Marty, said, “Pretty wet, huh? What’s all the shootin’?”

Marty shrugged, let the water drip from his hat, and sat down on a stool. He said, “Who cares. A guy only gets in trouble by being nosey. Give us a cup of coffee and a slice of cocoanut pie.”

The counterman gave him the coffee, and deftly slid a piece of pie from the tin tray onto a plate. “You’re right,” he remarked as he placed the plate on the glass counter before Marty. “Nowadays my motto is: ‘See nothin’, hear nothin’, tell nothin’.’ It’s a good way to keep your health.”

Marty drank half the coffee, though it scalded his mouth. Then he speared two big chunks of pie and ate them. It left about half the pie.

The counterman grinned. “Jeez—you musta been hungry.”

Marty took a roll of bills, passed up several singles, a couple of fives, and pulled out a twenty, laid it on the counter. The other said, “I see you got smaller, mister. If you don’t mind—”

“You don’t have to change it,” Marty told him. “Just put it in your pocket.”

The counterman grinned quickly. “Oh, yeah? The pleasure is all mine. But—”

Marty flashed his badge, took out a card and passed it to him. “Everything’s on the up and up, see? Only—”

The counterman lowered his eyes, slid the twenty and the card off the counter just as there was a loud noise outside, and the door banged open to admit a policeman. The policeman looked the place over, frowned, and came in. He stood over Marty. “How long you been here, guy?”

Marty looked up at him with a big piece of cocoanut pie in his mouth. He masticated the pie thoroughly while the policeman got red in the face. Then he said, “About ten or fifteen minutes, if it’s anything to you.”

The cop glanced at the counterman. “That right?”

“Sure,” said the counterman. “We heard the shooting, and figured somebody’d be in here, soon.”

The cop frowned, swung his gaze back to Marty, considered the almost finished pie and coffee; then he asked, “See anybody go by here after the shooting?”

Marty shook his head. “Nope.” He put another forkful of pie in his mouth, chewed stolidly, watching the cop.

“Stand up,” the cop ordered suddenly. “I’m gonna search you.”

Marty stayed seated. He put the last forkful of pie in his mouth, ate it, drank it down with the coffee.

The cop said, “Did you hear me?”

Marty wiped his mouth with a paper napkin, and stood up. He topped the cop by several inches, “I heard you. But you made a mistake. You ain’t gonna search me—not unless this is a pinch. An’ if it is you sweat for it. So make up your mind.”

The cop was young, excited. He put a heavy hand on Marty’s arm. “Wise guy, huh? I’ll show you—”

He stopped and turned. The door had opened. Detective Sergeant Sayre walked in, swept his eyes over the place. He said. “Hello, Quade. You in this?”

Marty said, “Hello, Dave. No, I ain’t in this. But your pal here seems to want to drag me in.”

Sayre looked at the cop inquiringly. The cop said, “Patrolman. Nevins, —th Precinct. I found this guy eatin’ in here, and he puts up a squawk when I want to search him!”

Marty squeezed past the cop, approached Sayre. “I told him to make it a pinch if he wanted to frisk me. He better read up on the rules.”

Sayre kept his eyes on Marty. “Three guys were just killed around the corner— in a sort of funny way. Must have been a fourth man who skipped. You been here long, Quade?”

The counterman came down behind the counter, toward them. “He’s been here about fifteen minutes, sergeant. He was here when the shooting started.”

Sayre looked obliquely at the counterman, then back at Marty. “I have a hunch, Quade—”

“Don’t play hunches, Dave. Go find the killer some place else. If you can’t find him, call it suicide. That’s one of your old stand-bys, isn’t it?”

THE cop interrupted. “Look, sergeant, this guy is fresh. Why let him get—”

“Cut it!” Sayre barked at him. “This guy is Marty Quade, the private dick. We can always get him if we want him. And he has a good story here. Think I want to make a fool of myself?”

Marty murmured, “Attaboy, Dave. That’s sensible.” He turned to the counterman. “How much I owe you, Jack?”

The counterman looked innocent enough to let butter melt in his mouth, which was quite an accomplishment with that face of his. “Let’s see—that was tomato juice, small steak, two coffees, and pie. Seventy cents.”

Marty glared at him. But he took out a dollar and laid it on the counter. The counterman grinned, rang up fifteen cents, and gave him thirty cents change. Marty said, “You only rang up fifteen cents. Trying to gyp the boss with two cops around?”

The counterman flushed. “Gee, that’s funny—how I made that mistake!” He reluctantly rang up fifty-five more.

Marty flipped a nickel on the counter, said, “So long,” and pulled open the door.

There was a thoughtful look in Sayre’s eyes as he watched him go out.

Marty walked north on River Avenue, away from Waverly. There were people around now—police, curiosity seekers, reporters, photographers. He turned right at the next corner and went swiftly till he got to Boulevard Avenue. He caught an empty cab there, and said, “Boulevard and Maple.”

When they got to the corner of Maple, Marty tapped on the window, said, “Stop here.”

He paid off and got out, surveyed Raynor’s house from across the street. His lips tightened. There was a police car in front of the door. He walked through the rain for a block and a half till he came to a stationery store. He went in, consulted the telephone book, then called the number of Raynor’s house.

Raynor’s voice, tense, anxious, snapped at him, “Hello, hello!”

Marty said, “Look, Mr. Raynor—don’t let on to the cops that it’s me—”

But Raynor was shouting into the transmitter, “Quade! Did you make the contact? God, tell me, quick!”

Marty cursed. “Now you gummed the works, all right!”

There was the sound of angry voices at the other end, Raynor’s protesting, another, drowning him out. Then a voice, crisp, authoritative: “Quade? This is Inspector Hanson. Come right up here. I want to talk to you!”

Marty said, “Hello, inspector. Sorry, I can’t make it. I’m calling from out of town. Let me talk to Raynor, will you? I’m in a rush.”

Hanson sputtered. “I won’t have it, Quade! I won’t have a private operative mixing in this. It’s a matter for the police. If we got a little co-operation once in a while we’d nab these kidnapers—”

“Yeah!” Marty cut in. “Like you got the Robinson kid’s snatchers last week. All you got was the kid’s dead body in the apartment!” He pressed his lips close to the mouthpiece, talked forcefully. “Get this, Hanson—I’m retained on this case. I’m gonna get Raynor’s girl—and I’m not lettin’ the police break in on me and gum the works. Understand? Make what you like out of it!”

Hanson exploded. “Why! I’ll—”

“Yeah, sure! You’ll do a lot. Have me pinched for obstructing justice? And if Raynor’s girl turns up dead afterwards, won’t you look sweet! I’d make it so hot for you, Hanson, you’d have to resign. And you know I could do it! There’s a lot of papers would print the story of how you wouldn’t let me play with the case. So what is it, inspector—dice, or no dice?”

Hanson said, “Wait a minute,” in a flat voice.

The wire was quiet for two minutes. Marty could hear heated voices at the other end—Raynor’s and Hanson’s.

Then Hanson barked, “Look, Quade— I’ll stretch a point. I’ll leave you alone for three hours more; till midnight. By then you got to have the girl, or I’ll jump on you with both feet. Is that clear?”

“Fair enough, inspector. It’s a bargain.”

“I’m only doing it because Raynor insists. He says you were supposed to pay over fifty thousand. What happened?”

“No soap. They wanted the dough, but didn’t want to give up the girl. They tried to get me out of the picture.”

“So?”

“Well, you see I’m still on the scene. But I figure they intended to collect that fifty grand just as a down payment, then come back for more. In the end they might bump the kid anyway. They’re a lousy crowd—they double-cross themselves.”

“What’s the objection—”

“To lettin’ the police in on it? They’d bop the kid at the first hint of cops. I stand a better chance. They know I’ve still got the fifty grand.”

Hanson said, “Hold it a minute, Quade.”

Marty heard Raynor’s voice talking emphatically to the inspector. Then Hanson said into the phone, “Raynor says to tell you that he wants the girl, but if you save the fifty thousand you get ten per cent of it in addition to your fee; and an extra thousand for everyone of the gang that gets killed in the process. This is unofficial as far as I’m concerned.”

Marty said, “You can tell Raynor he owes me three thousand already.” He hung up and went out grinning.

THE rain hadn’t let up any, and it was hard to find

a cab. He stood at the curb, and saw the figure that was hurrying

on the other side of the street, from the direction of

Raynor’s house. He cursed under his breath, waited till the

man came up opposite him, and watched him suddenly slow down and

dawdle before a store window. He caned across the street:

“Hey, Sweetser!”

When the man turned around he shouted, “Come on over here—it’s just as wet on this side.”

Sweetser hesitated, then crossed. When he came up close, Marty said in a thick, angry voice, “What the hell sort of heels are you cops, anyway? 1 thought Hanson was going to leave me alone for three hours!”

Sweetser grinned in a conciliatory way. “I can’t help it, Quade. The old man had the number traced while he was talking to you, an’ he told me to get out here an’ tail you.”

“All right,” said Marty. “I tagged you. You’re it. Go back and tell Hanson I said he’s a louse.”

Sweetser shook his head. “Sorry, Quade. The old man covered that, too. He said if you got wise I was on your tail, to go right along with you anyway—an’ if you didn’t like it to take you in. So there.”

Marty looked at him murderously. “You guys are bound to queer this deal, aren’t you? You know damn well that those snatchers will knock off the Raynor girl as soon as they smell cop. But you will be thick-headed about it!”

Sweetser spread his hands. “What can I do about it, Quade? Orders is orders.”

Marty suddenly shrugged, said, “Okay.” He turned back into the stationery store. “As long as I got to stand for you, you can make yourself useful.”

He led the way to the telephone booth, took out one of the slips of paper he had taken from the body of Wurtzel. On it was written nothing but a telephone number. “Here,” he told Sweetser. “Get in there and use your influence to make the telephone company tell you the address of that subscriber.”

There was a cunning look in Sweetser’s eyes as he took the slip of paper and stepped into the booth. He picked up the· receiver and asked for the supervisor. When he got the supervisor, he gave his shield number, and requested the name and address of the subscriber at the penciled number.

Marty crowded into the booth beside him, and heard the supervisor say, in a minute or so, “The name and address of the subscriber at Leighton 4-8323 is Ben Oppenheim, at four-two- six River Avenue. They have another six listing under the name of Sheldane Rooming House.”

Marty caught the words, made a mental note of the address.

Sweetser hung up, said over his shoulder, “It’s only a public telephone, Quade. I guess you got a blind lead there.”

Marty said, “Yeah. Too bad.” He took out his automatic, and tapped Sweetser on the side of the head—medium hard.

Sweetser said, “Un-nh!” and collapsed, with his forehead resting against the instrument.

Marty held him erect, pried the door open with his foot, and eased him to the floor. The proprietor of the store came around from behind the counter. He had not seen the blow, but had heard Sweetser’s groan. He said, “Ach. Vat giffs it?”

Marty said, “My friend has indigestion. Watch him while I get a doctor.” He left the storekeeper gaping, and sped out.

He saw a cab passing, and flagged it, said to the driver, “Shoot across to River, and straight out, about a block past Waverly.” He settled back in the seat, and put a fresh clip in the automatic.

HIS guess was fairly accurate. Four twenty-six was in the middle of the second block after Waverly. They passed a small crowd in front of the coffee pot—the excitement about the three bodies hadn’t died down yet.

The Sheldane was a cheap rooming house. There was a sign projecting from the discolored three-story building that read:

>SHELDANE ROOMING HOUSE

B. OPPENHEIM,

Prop.

Rooms by the Day

Week or Month

Marty gave the driver a dollar and a quarter, and watched him pull away. Then he crossed the street and went in through the scratched-up, unwashed entrance. The ground floor consisted only of a narrow hallway with a foul smell. A steep flight of stairs led up.

Marty mounted to the first floor. Here there was a row of rooms along one side of the hall. The other side was taken up by the stairs. A woman with cold cream on her face, and her hair done up in curling pins, looked out of one of the rooms, smiled, and when she failed to get a rise, disappeared into her room and slammed the door.

Marty walked down the hall till he came to the end room. A piece of cardboard was tacked on the door jamb.

On it was penned sloppily:

Office—Ring for Service.

Marty didn’t ring for service. He put his hand on the knob, and shoved the door open, stepped halfway in, and leaned with his left side against the doorjamb. His right hand was in his coat pocket.

The man and the woman who had been playing casino at a table in the “office” dropped their cards and stared at him. The man was big and heavy, with a paunch that hung over in his lap. He had very small eyes, which were almost invisible in the tissues of fat that constituted his face. He was in his vest, and his shirt sleeves were rolled up.

The woman wore a negligee over cheap pink lingerie. Her hair was manufactured blonde, and reflected several shades under the electric light. Her face was rouged to the limit, and her lips were painted so heavily in the middle that the edges of her mouth looked dirty by contrast. She dropped her cards, cried out hoarsely, “God! It’s Quade!” She drew her negligee together with an instinctive gesture, and raised a hand with long red, pointed nails to her mouth.

The man laid down his cards slowly, picked up a cigar from the table and put it between his teeth, rolled it. He put his hand on the drawer in the table.

Marty said, “Hello, Oppenheim. Hello, Lena.” But he didn’t smile. He closed the door behind him, without turning his eyes from the two of them.

OPPENHEIM opened his mouth to talk; he was so upset the cigar fell out. He caught it awkwardly in his right hand, shifted it to his left, then put his right hand back on the handle of the table drawer. He said, “Quade! How’d you git here?”

Marty said, “I got a riddle for you, Oppenheim—what would a guy named Nicky, and a guy named Goldie, go gunning for me for? Answer me that one.”

Oppenheim tried a sick grin, but it turned into a leer. “That—that’s a kind of a funny one to ask me, Quade. I don’t know them guys you mention.”

“No? That’s funny, all right, but not the way you mean. They mentioned your name. Also, while we’re on it, how about a guy named Wurtzel—the one that called you up a little while ago, the one that puts me on the spot for you?”

Oppenheim started to stand up. Under cover of his big body he pulled the drawer out a little, his fat hand felt inside.

Marty snapped, “Stand away from it, Oppenheim!”

Oppenheim, with a desperate set to his face, dragged a gun out of the drawer.

Marty took his automatic out, and covered him. “Now that you got the gun, what are you going to do?” he asked quietly.

Oppenheim, very pale, put the gun down on the table, and faced Marty. The gun was now within the woman’s reach.

Marty said to him, “Too bad you didn’t try some kind of a play with that gun. You’re worth one thousand berries to me—dead!”

Oppenheim tried to bluster. “What the hell do you want here, Quade?”

Marty said quietly, “I’ll tell you, Oppenheim. I’m not a guy to hold a grudge; so I’ll forget about you having tried to get me bopped. But there’s something else—I want the Raynor girl!”

Oppenheim gasped, “You’re crazy!”

“So now I’m crazy,” said Marty. “Okay, I’ll act crazy. I’m gonna put a slug right in the middle of your vest—right now!”

Oppenheim cried, “Wait, wait!”

The woman spat out, “Shut up, you fool! He ‘ain’t gonna do it! He’s just talkin’.”

Marty smiled bleakly. “Oppenheim knows better. Don’t you, Oppie?”

The fat man nodded. His face was ashen. “He will, Lena. You don’t know his rep like I do. Wait—” as Marty raised the automatic. Then in a whisper, “I’ll take you to her.”

The woman snarled, “You dumb cluck! He ain’t got a thing on you—an’ you’re givin’ it all away on account he talks big!”

She snatched at the gun. Marty was too far away to reach her without shooting. He shouted, “Grab her, Oppie, or I give it to you!”

Oppenheim brought his big paw down on the woman’s arm, while with the other hand he swept the gun off the table. “I tell you,” he whined, “he’ll kill me! I know him!”

Marty smiled grimly. “All right. Now we understand each other. Let’s go.”

Oppenheim said, “She’s upstairs. We got her in a coffin. No, no!” he exclaimed, as he saw the blank look come into Marty’s eyes. “She ain’t dead. It’s just a stall. Nobody’d think of lookin’ in a coffin. It’s supposed to be my uncle who’s gettin’ buried tomorrow. We dumped his body in the river with some lead weights on it last night.”

Marty opened the door. “Lead the way.”

Oppenheim went out, past Marty. Marty looked at the woman. “You, too.”

The woman glared at him. “You go to hell!”

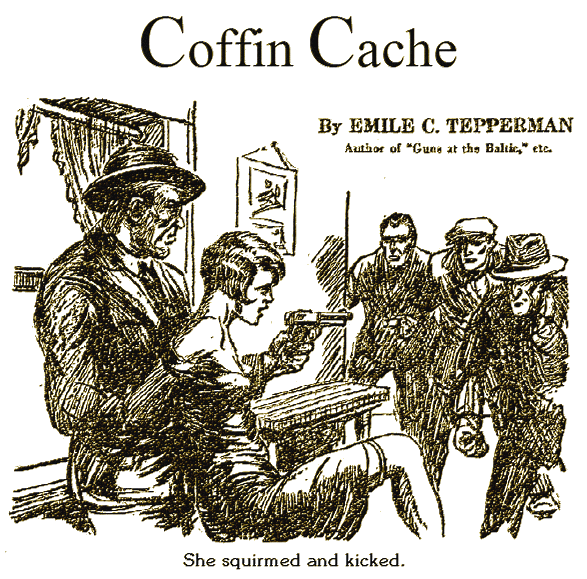

Marty shrugged. “You will have it!” He went into the room, grabbed the woman about the waist. She kicked as he lifted her, scratched at his face until he pinioned her arms. Then he carried her bodily to the closet, thrust her in, and shot the catch. Her voice came through the door, muffled but virulent.

Marty left her there, went out in the hall, and swore.

Oppenheim was gone. He could hear the fat man’s feet pounding up the stairs. He jumped up the stairs after him, caught sight of him at the top. Oppenheim was shouting up, “Jake, Jake! Shoot the works!” A couple of people opened doors, then closed them quickly. They were minding their own business.

Marty took the stairs three at a time. On the next landing he just saw Oppenheim turning up for the last flight. He followed.

Oppenheim was at the top of the last flight, Marty down toward the middle, when a door on the top floor, at the head of the stairs, opened, and a short man in shirt sleeves, with a close- cropped head, came out. He held two guns, and was scowling.

Oppenheim dropped to the floor, shouted, “Take him, Jake! It’s Quade! He’s on to us!”

Jake said nothing. He looked down at Marty on the steps, raised both guns. Marty slanted his automatic upward, and kept his finger pressed down. Seven slugs jerked out of the automatic, filling the house with mad reverberations. Jake’s face assumed a look of amazement. He dropped both guns, then started walking backward, unsteadily, into the room he had just come out of. Then tiny fountains of blood began to spurt from his chest, and he suddenly sat down on the floor. Then he rolled over and twitched. His eyes stayed open, glassily.

Marty hit the top landing just as Oppenheim struggled to his feet. Marty swung his gun viciously, caught Oppenheim in the jaw with it. Oppenheim collapsed without a word.

Marty stepped over Jake’s body and went into the room. It was furnished like the others, but on the floor in the middle, lay a coffin. Strange kicking sounds came from its interior.

Alongside the bed were five ten-gallon tins of gasoline. Long strips of twisted newspaper ran out of the open top of each tin, to the floor. Each strip was burning merrily. The ends on the floor had all been lighted. When they burned down to the gas in the tins, the fire department would have its hands full.

Marty yanked the strips of paper from the cans, stepped on them till the flames were out. He heard a confused milling out in the hall, and looked to see a dozen of the boarders clustered about the entrance.

“Scram!” he barked at them. “The cops’ll be here in a minute.”

Then he went to work on the coffin. When he started to unscrew the bolts, the kicking ceased.

He said, “It’s all right, kid. Just relax. You’ll be out in a minute. You must feel pretty bad in there.”

He got a single little kick in answer.

He got the last bolt off, and lifted the lid. He recognized Madge Raynor from the pictures. She was no more than sixteen. Her hands were held at her sides by a heavy length of hemp that had been wound around her body a dozen times. There was a vicious gag in her mouth; it kept her jaws distended. She had long hair, dark brown, and it formed a sort of cushion for her head. Her eyes were wide open, darting about the room—as much of it as she could see from the bottom of the coffin.

Marty lifted her out, set her in a chair, still tied, and removed the gag. “Now don’t get hysterical, kid,” he soothed. “Everything is all right. Your dad will certainly be glad to see you again. Just take it easy.”

Her wide mouth shaped itself into a happy laugh. “Hysterical? Why, mister, I haven’t had a better time in all my life. This is just the thrillingest experience I’ve ever had! Untie me, will you. I’m a little stiff.”

“Hell!” Marty muttered, as he bent to untie the knot.

They heard a commotion downstairs, the sounds of feet pounding up, and the voice of Detective Sergeant Sayre: “This is a hell of a neighborhood! I’ll never get home tonight if they keep on shootin’ each other up! Where’s the bodies?”

“That’s the cops,” Marty told her.

“Oh, swell!” exclaimed Madge Raynor. “Will they take my picture?”

Marty got the knot free.

“Stand up,” he ordered, “while I unwind you.”

Sayre and a couple of uniformed men shoved into the room while he was doing the unwinding.

Sayre said, “‘Well, if it ain’t my friend Marty Quade again! I suppose you don’t know a thing about this shooting, either!”

Marty got the last coil of rope off the girl. “This is Miss Madge Raynor. You cops couldn’t find her, so I had to attract your attention by shooting off a gun.”

Sayre exclaimed, “I’ll be damned!” His eyes swept the room, lighted on the gasoline tins.

“That,” explained Marty, “would have been a classy stunt. They had it fixed so that if the police raided the place, they could start a fire and burn up the evidence—the evidence being Miss Raynor.”

Sayre said grudgingly, “Nice work, Quade.”

Madge Raynor looked at the gasoline tins without interest. “I could stand a cup of coffee,” she said.

Sayre glowered at her, grumbled, “What a generation these kids are! Nothing fazes them!”

But Marty grinned suddenly. He took her arm. “Come on, girlie, I know where we can get coffee. There’s a bird on the next block owes me fifty-five cents’ worth of eats!”