RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Popular Detective, March 1936©

Tense, Dramatic Moments in a

Courtroom—

When a Fiend of Murder Faces Grim

Accusation!

"NOW, Mr. Witness, will you just tell the Court and the jury what you saw on the corner of West Street and South Broadway at six P.M. on the evening of the 25th of July? Tell them in your own words."

"Well, Mr. District Attorney, the way I told you, I was standing just outside the pool room, and I seen this sedan come around the corner. Louie Link was just comin' out of his house across the street, and he seen the sedan and started to duck back in his doorway, but a man stuck his head out of the back window of the sedan, and let loose with a typewriter—I mean a tommy gun.

"He sprayed the whole street for about fifty feet on both sides of Louie Link's house, and Louie Link was just about cut in half. There was two kids comin' out of the grocery store next door, with a bottle of milk, and they got it too. Both of them was killed."

"What happened after that, Mr. Witness?"

"The driver of the sedan stepped on it, and they swung around the corner."

"Did you see the face of the man who fired the sub-machine gun?"

"Yes, sir, I seen it."

"Would you know him if you saw him again?"

"I think so."

"Have you seen that man since the 25th of July?"

"Yes, sir. He's right here in the courtroom."

"Point him out."

"That's him, sir—Nick Marco, the defendant in this case. He's sitting right there at the counsel table."

The earnest young assistant district attorney heaved a sigh. This was the last witness for the People, and though the man's testimony had been positive enough, his reputation was none too good.

"Your witness, Mr. Benson," he said to the suavely smiling counsel for the defense.

Jerome Benson leaned back in his chair next to his client, lids half lowered over his eyes. He knew that a hundred people in the spectators' benches behind him were watching his back breathlessly.

Lazily, negligently, he waved his hand.

"No questions!"

The judge frowned, puzzled. A buzz of comment rippled through the courtroom from the spectators. Benson always glittered in cross-examination; but in this case he had not questioned a single one of the People's witnesses.

NICK MARCO, the defendant, scowled, said hoarsely out of

the corner of his mouth: "Hey, Mr. Benson! What sort of gag is

this? You taking me for a ride? I ain't paying you fifty grand to

sit here—"

Benson said, very low: "Shut up. I'm handling this case!"

The young district attorney was plainly worried. One of his investigators made his way quietly through the courtroom, whispered in his ear. The district attorney listened for several minutes, then nodded, addressed the judge.

"The People rest," he said.

Benson arose languidly, while judge, jury and spectators waited eagerly to see how he would open the case for the defense. There could be no doubt that he had some sort of trick up his sleeve.

The lawyer winked at his client. "It's in the bag, Nick," he whispered. Then he stepped around the counsel table, approached the bench.

"Your Honor," he said smoothly, with that characteristic air of having his tongue in his cheek, "in view of the fact that it is close to noon, I will ask that court be adjourned for lunch at this time. I find it necessary to interview a witness whom I have not yet met. As your honor knows, I was only called into this case today, and I should like to acquaint myself with this witness' testimony."

The judge nodded. "The court stands adjourned until two o'clock."

Benson said: "Thank you," and walked back to the defense table.

Nick Marco looked up at him anxiously. "Look, Mr. Benson. You—you sure this is in the bag?"

Benson patted his shoulder. "Psychology, my boy—did you ever hear the word? The jury doesn't think much of the state's witnesses; one of them admits he hangs out in a pool room all day, the other is a cokey, and they know it. I could break both of them down in no time, but by not cross-examining them I've convinced the jury I don't attach any importance to them. Now, when I bring in this witness after lunch, they'll forget all about the state's evidence. If the D.A. tries to break him down, the jury will think it's not sporting of him—I left his witnesses alone, and he should do the same for mine. Get it?"

He grinned at the blank expression in Nick Marco's face. "Too deep for you, eh?"

"I guess you know what you're doing, Mr. Benson." Marco glanced around furtively at the bailiff, who sat on his other side. "But what's this witness gonna say?"

Benson stooped, brought his lips close to Marco's. "Did you know you were a hundred miles from this town on the day of the shooting?"

Slowly a smile spread over the defendant's face. "I get it." His lips were twitching nervously. "Believe me, I had the willies when that D.A. put his witnesses on." He added fiercely: "You got to get me outta this, Benson!" He passed a moist hand across his mouth. "I'll never let them burn me. God! I get cold all over when I think about walking to the chair with my head shaved and my pants ripped up the legs!"

Benson shrugged. "You'll be forgetting all about it inside of an hour. But not the other half of my fee—don't forget that. It costs like hell to shoot up kids—even by mistake."

He grinned, and sauntered out, fingering the flower in his buttonhole.

THE young district attorney had been watching him

closely. As soon as the courtroom had emptied of spectators, he

hurried up to the bench. "Your Honor!" he blurted.

The judge set down the glass of water he had been sipping, scowled at him. The jurymen stopped in the act of filing out, attracted by the note of appeal in his voice.

Nick Marco said to the bailiff who was preparing to conduct him back to the detention pen: "Wait a minute, will you? Let's hear what the squirt's got to say."

"What is it, Mr. Anders?" the judge demanded of the young prosecutor.

"If your honor please," Anders said, speaking quickly, breathlessly: "I have just received definite information that the witness Mr. Benson is going to meet for lunch will testify that the defendant, Marco, was in a town a hundred miles from here at the time the crime was committed!"

The judge flushed, glanced at the jurymen, frowned at the prosecutor. "Mister Anders! I am surprised. The defense could claim a mistrial—"

"Wait, your honor," Anders hurried on desperately. "This witness is going to commit perjury. Marco shot those children down callously. But that witness' perjured testimony will be unimpeachable. I am informed that he is a man of substance and standing. Benson is going to prime him on just what to say. I—"

He was interrupted by the outraged expostulations of Benson's two assistants, who had been sitting at the counsel table with Marco. One of them was Tyler, Marco's attorney of record, who had engaged Benson as trial counsel; the other was a clerk from Benson's office, who had prepared the notes that Benson used. The clerk was worried, didn't know exactly what to do; his textbooks had never coached him for such an unprecedented situation. But the older attorney exclaimed:

"Judge, I never heard of such a thing—"

From behind him came Marco's frenzied shout: "Hey! What's this—frame-up? Get Benson back here!"

Anders kept on talking, ignoring the interruption. "Your honor, my investigator tells me that Benson has reserved a private dining room in the Grand Hotel, across the street, where he will interview this witness."

The judge was interested, despite his annoyance. He raised his hand to silence the attorney of record. "Let Mr. Anders finish, Mr. Tyler. I presume he is sane. The case is a mistrial already, so we might as well listen."

Tyler shrugged, smiled sourly at Anders, threw a knowing look at the jury.

Anders went on: "My investigator has installed a dictograph in that dining room in the Grand Hotel. I want you to let the jury listen in on the conversation between Benson and his witness. The People's case will stand or fall by what we hear!"

Marco, who had been leaning over the counsel table to hear better, started to shriek frenziedly. "You can't do that to me, damn you. You can't. You want to burn me, don't you? I'll never let you burn me!" He turned toward the door and screamed: "Mr. Benson! Mr. Benson! They're framin' us!"

The bailiff and one of the court attendants forced Marco back into his chair.

The judge waited until he had quieted down, then said to the young prosecutor:

"Surely you must realize that you have ruined your case, Mr. Anders. If I should permit such an unheard-of procedure it would without doubt be viewed as a reversible error by the higher court—"

THE foreman of the jury, who had been listening intently,

whispered with his colleagues, then raised his voice:

"If I may suggest it, your honor, the jury would like to listen to that conversation between Benson and his witness."

Tyler, the attorney of record, said: "Your honor, in behalf of my colleague, Mr. Benson, I object to this procedure. It is so self-evidently contrary to the code of criminal practice that I need not even state my grounds—"

He halted as a knock sounded at the door of the courtroom.

Marco shouted: "That's Mr. Benson. Let him in." His voice rose to an hysterical pitch. "They're framin' to burn me, Benson! They—"

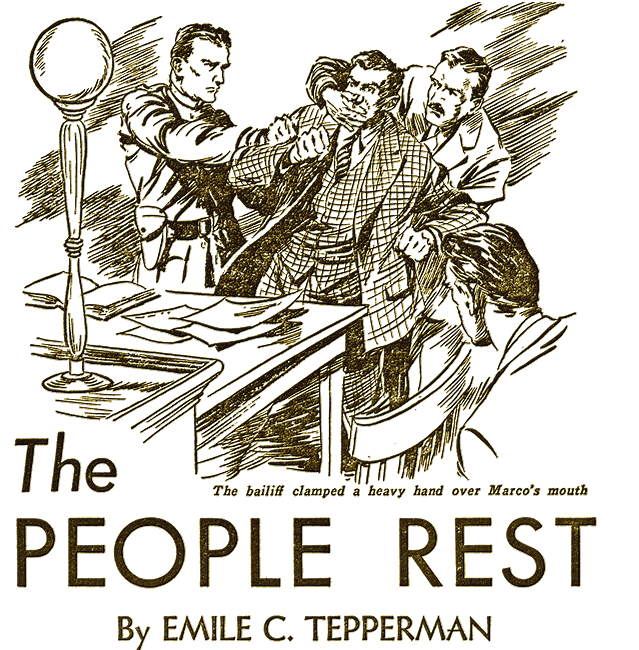

The bailiff clamped a heavy hand over Marco's mouth, and Marco bit him, struggled up from his chair. He drove an elbow to the stomach of the court attendant on his other side, got free for a moment, and leaped toward the window, his face twisted into a mask of fear.

Before he had taken two steps the bailiff was upon him, assisted by several of the court attendants, and the investigator from the district attorney's office. It took almost five minutes to subdue him, and at the judge's order he was dragged out of the courtroom through the grilled doorway at the side, which led to the detention pen.

During the mêlée the door of the courtroom had opened, and an elderly man entered, sidled over to Tyler, and handed him a slip of paper, then made his way out. Tyler read it quickly, frowned, and read it over again.

Then he put it in his pocket, watched dispassionately while Marco was forcibly led out, still shrieking.

The judge pounded with his gavel for order. He was at the end of his patience. "Damn it, Anders," he exploded, "I'm going to have you barred from this court. You—"

Tyler stepped up close to the bench. "If it please the court," he broke in, "I have a suggestion to make. The defense will waive any objection to this procedure. We will agree to be bound by what the jury hears over Mr. Anders' dictograph—" he glanced covertly at the jury to see the effect of his words—"provided Mr. Anders will agree to be likewise bound!"

The judge said, puzzled: "You mean—"

"That I have sufficient confidence in my colleague to feel that he is not suborning perjury. As an officer of this court, I feel that the jury should know everything that bears on the case; therefore I am willing to have them listen in. But if the conversation between Mr. Benson and the witness proves to be bona fide, I want the district attorney to nolle prosse the case."

Anders nodded quickly. "Agree."

The judge hesitated, then shrugged. "As long as the defense consents, I see no further objection. Very well, gentlemen of the jury; you shall listen."

Anders said: "The dictograph is connected in my office, judge. No one will warn Benson—we have a man posted outside the dining room door." He led the way out.

ACROSS the street, in a private room in the Grand Hotel,

Benson was talking to a thin, silver-haired man, over a liqueur

that had completed a highly satisfactory lunch.

"Now, Mr. Hedges," the lawyer said, "we can get down to business. I am not going to ask you any leading questions. I am convinced that my client is innocent of that shooting, and I want to hear what you know about it."

"Why," the other man replied slowly, "I know nothing of the actual crime. But I am as certain as I am of my name, that Nick Marco was not in this city on the 25th of July, at six o'clock in the evening."

Benson said: "Go on, Mr. Hedges." He sipped his liqueur appreciatively, waited for the other to proceed.

"As you are aware," Hedges continued, "I am the president of the Midland State Bank of Midland City. July 25th fell on a Thursday this year, and we always keep our banking offices open until eight o'clock on Mondays and Thursdays for the convenience of depositors. Well, I recall distinctly that it was at about five-thirty when this man, Marco, came in to see me. He wanted to open an account with us, making a substantial initial deposit."

"And did he open the account, Mr. Hedges?"

"He did not," the banker stated emphatically. "It so happened that I was familiar with the gentleman's reputation. Our bank is an old one, and our family has run it conservatively for three generations. We do not care to do business with racketeers!"

"I see," said Benson. "Did you tell that to Marco?"

"I certainly did, without mincing words. He could not believe that we would actually refuse to accept a cash deposit, and I finally made it plain to him what my feelings were in the matter. I was alone in the bank, my teller having gone home for supper, and I was rather nervous, glad to see him go at last. He left at about five minutes to six, and though I entertain a deep scorn for persons of his calibre, I must say that he could not have committed this particular crime for which he is being tried today. You see, Midland City is a hundred miles from here."

"Quite so," said Benson in a pleased voice. "And, Mr. Hedges, are you positive—remember, I say positive—that it was Nick Marco himself who was there?"

"Absolutely so. I would not have gone to the trouble of phoning you from Midland City this morning had I not been positive. I never forget a face, Mr. Benson; it is a quality that a banker must cultivate."

"What prompted you to phone me, Mr. Hedges?"

"I disliked very much to see a miscarriage of justice. Whatever other crimes this Marco person may have committed, he is quite innocent of this one. I would feel almost as if I had murdered him with my own hands if I let him go to the electric chair without interfering. How is it that he didn't try to get in touch with me?"

"Marco has been telling me about some bank he stopped in at that day. But for the life of him he couldn't remember the name of the town. He said he had been driving aimlessly for a few hours, had seen the bank open late, and it had struck him as a good place to leave some money in case he needed to draw it out in a hurry some evening. My men have been conducting inquiries among the banks in the nearby towns, but we have confined ourselves to a radius of fifty miles from the city. We had no idea he had driven so far. And besides, I just came in on the case."

He sighed. "I almost thought I was licked. I'm sure the district attorney thinks I'm putting one over on him, and it's probably the only time I haven't. Suppose we get over to the court now."

They finished their liqueurs, and left.

Outside, Mr. Hedges took Benson's arm. "Listen, Benson," be demanded. "Are you sure I won't get in trouble on this thing?"

Benson shook his head. "Not a chance. You won't even have to testify. The D.A. will have to nolle prosse the case. It's a good thing I have connections in the D.A.'s office that tipped me off about the dictograph. You put up a good spiel."

Hedges asked anxiously: "And—about the other thing?"

"Don't worry," said Benson. "I promised you that I'd square up the shortage at the bank, and I will. I know the examiners. You just sit tight when they come, and they won't notice a thing."

"I'll owe you a lot for that," Hedges said fervently.

"You don't owe me anything. You've paid off in advance with that spiel of yours. I'm getting plenty from Marco."

BACK in the courtroom, the jury filed into the box,

slightly bewildered. The judge scowled from the bench, and Tyler

winked at Benson, who had entered with his banker witness in

tow.

Young Anders, the prosecutor, was glum-looking and shame-faced. He hurried over to Benson, drew him to one side. "I'm going to nolle prosse this case," he confided.

Benson raised his eyebrows. "Really?"

"And, Benson, I want to apologize to you. I judged you wrongly. I did a terrible thing—"

Benson lifted his hand. "Tut, tut. We've all done terrible things. Don't let it make you feel too bad." He glanced toward the door of the detention pen. "Here comes Marco. He'll be glad to hear you're dropping the case."

Marco entered, his right hand was handcuffed to the bailiff's left. His head was lowered, and he walked with a shuffling, reluctant step.

Benson left the prosecutor, went over to his client. "Marco," he said, "something has happened—"

Suddenly Nick Marco raised his head, and Benson recoiled at the mad light in the man's eyes. Words came tumbling out of him.

"I know damn well something's happened!" his voice rasped. "They was too smart for you. They heard you framin' that witness—"

Benson exclaimed urgently: "Shut up, you fool—" but Nick's hysterical accusation drowned him out.

"So it was in the bag, huh? An' now I burn! Well, I don't, see! They'll never get me in the chair!"

His right hand flashed to the bailiff's holster, snatched out the heavy service revolver. Before the stunned courtroom could grasp what was happening the revolver roared, belched once, and Benson tottered, an amazed expression on his face. Once more Marco fired, but this time he had turned the muzzle against his own temple. He fell in a heap over the body of his attorney, dragging the horrified bailiff after him by the handcuffs.

And while pandemonium took charge of the courtroom, Mr. Tyler, the attorney of record in the case, quietly tore up the note that had been handed to him by the elderly messenger. Tyler preferred that its contents be not known. The note read:

Agree to whatever the district attorney proposes. I have the situation well in hand. But don't tell Marco; that moron won't know how to act.

Benson.