RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

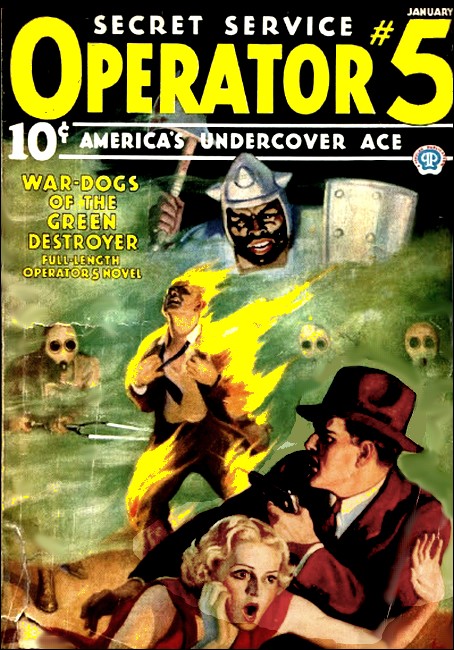

Operator #5, January 1936, with "Orders to Hell"

Burt McFey had to hi-jack those war plans—or see America doomed. What if a pal were dead, a riot fomented, a gauntlet of Tommy-guns run? What if Burt McFey leaked like a sieve from bullet wounds, and stared, eye to eye, into Death's grim face?

MAJOR RAND, head of the United States Counter-Espionage

Service, paced nervously up and down the little office, five

floors above the street. He stopped every few moments at the

window to focus the powerful pair of field glasses in his hand

upon a building two blocks away, on the opposite side of

Broadway.

The windows across the second floor of that building carried the legend in small, dignified lettering:

CONSULATE OF THE TURANIAN REPUBLIC

The major frowned, lowered his glasses and turned back into

the room to face the lean, hawk-faced young man who was watching

him intently from a chair beside the mahogany desk. "I'm afraid

Littleton will never make it, Burt. He's a brave man, but he's

not used to this kind of work. I'm afraid they've spotted

him—"

He stopped, swung back toward the window, and raised his glasses again. "I'm afraid I've sent Littleton to his death."

Burt McFey, ace operative of the United States Counter- Espionage Service, arose from his chair beside the mahogany desk, came over to stand at the window beside the major. "You should never have put him on the job, Major Rand, if you'll forgive my saying so. You knew I was returning from Turania today. Why didn't you wait?" There was an intensity of feeling in the lean McFey's voice that he appeared to restrain with an effort.

"Jerry Littleton is only a kid, Major. How could you sacrifice a boy's life like that—?"

Major Rand exclaimed hoarsely: "Stop it, Burt." His face was gray, and there were dark wells of unhappiness in his eyes. "Do you think it gives me any pleasure to know that I've sent a young fellow like Littleton to risk his life on a fifty to one chance? God! I wish I could have gone myself. But the job had to be done, and he was the only one available."

The major put his hand on Burt McFey's shoulder. "Don't you understand, Burt, that it may mean the salvation of our country to get hold of the papers out of the Turanian Consulate's dispatch bag? Turania has something up her sleeve, Burt—or else she's never have the nerve to act the way she has. Do you think one lone, little, South American country could ever consider declaring war on the United States unless she had an ace in the hole?"

Burt McFey stared moodily out of the window. "Of course not. And I couldn't get within a mile of the War Office down there."

"Yet you wired me that the cabinet was voting on a declaration of war!"

"That's right."

Major Rand took a deep breath. "And you reproach me for risking one man's life to discover what their secret is. What is one man's life against that of the nation? You and I, Burt, we would gladly die if we could—"

McFey lowered his eyes. "I'm sorry, Major. You're right. Only I hate to see—"

He was interrupted by the ticking of the telautograph machine on the mahogany desk. The major stepped quickly across to the desk, clicked a button, and watched the automatic pencil write a message upon the white paper in the machine—a message which was being transcribed just as it was being written from espionage headquarters in Washington. This latest equipment made it possible to transmit authentic messages in the quickest possible time.

The words being written on the sheet were in code, but both the major and Burt McFey could read it as it appeared without the aid of their code book:

Confidential dispatch: Miguel Alcolar, Dictator of Turania, refuses to interview our ambassador at Santa Morenas. Presents note demanding that we surrender person of Burton McFey. What has he done? We suspect that Turanian Consul, Ginández, in New York, is planning some sort of coup. Can you discover what it is?

The signature that Major Rand and Burt McFey saw signed to the

message was that of the Secretary of State.

Burt raised his eyes from the telautograph to meet those of the major. The two men stared at each other, not speaking, for a long minute.

"God, Burt," the major breathed, "what did you do down there to make them want you so badly?"

Burt McFey laughed shortly. "I found out what they were doing; I got through the military lines they've established around the new air base down there at Santa Morenas. I counted their battle planes. You know, they've been buying parts and motors secretly all over the world."

The major nodded. "Yes?"

Burt McFey's mouth was a thin, hard line. "Major Rand, that air base at Santa Morenas covers an area of thirty square miles. They have hangars strung out along the eastern and western borders of the base, spaced a thousand feet apart. There are a hundred and fifty hangars along each side—three hundred in all. And each hangar accommodates four planes. Twelve hundred all together!"

Major Rand stared almost unbelievingly. "Twelve hundred planes! That is greater than our own effective air force. Can they mean to attack us in the air? They haven't got the pilots—"

"They haven't, major," Burt told him. "I saw plenty of mechanics, but only a handful of pilots. Those planes must be a blind for some other plan—"

Major Rand nodded somberly. "That's why I sent Littleton. The consular messenger arrives today, and Littleton's going to hold him up in the hallway. He's got to do it unofficially, of course. We could never explain to Washington that we had rifled a diplomatic pouch—even though the fate of the nation was at stake." He said it bitterly, and his tired eyes reflected an immense repugnance to the work he was doing.

Burt took the glasses from the major, focused them on the building of the Turanian Consulate. He said: "Turania wants me badly, major. I burned ten of their hangars at the Santa Morenas air base—forty planes destroyed—and I escaped in the commandant's own ship, which was being warmed up at the line. If I surrender, it may avert a break between Turania and the United States for a few days—long enough for you to find out what they have up their sleeve—"

The major interrupted him in a flat voice: "I won't do it, Burt—"

"Yet you sent Littleton—"

"That was different. You're the most valuable man I have. Littleton was the only one available. Aside from any personal feelings, I can't spare you. I won't do it."

"All right then," Burt said grimly. "I'm going over to the consulate and wait outside. Maybe I can give Littleton a hand."

The major said reluctantly: "All right. But keep under cover. Ginández and the rest of the Turanian crowd don't know you're back in the States yet. What they don't know won't hurt them."

Burt McFey nodded shortly, went out through the small outer office, past the big double switchboard that served the battery of phones on the major's desk.

Out in the street, he lit a cigarette, started up in the direction of the Regal Building where the Turanian Consulate was located, keeping on his own side of the street.

He was almost abreast of the building when he saw the little man dart out of the entrance. He threw away his cigarette and started across at an angle so as to meet the little man at the corner.

IT was eight o'clock, and the theatre crowd was beginning to

jam Broadway. Traffic moved at a snail's pace even with the green

light, and Burt had little difficulty threading his way among the

crawling automobiles. He kept his eye on the little man who was

pressing through the throng, holding a long manila envelope

clutched tightly in his left hand. The little man's right hand

was in his jacket pocket. Burt's eyes, swinging for a moment back

to the Regal Building, saw two dark-complexioned, bony-looking

men come out, stand in front of the building looking in both

directions. One of them was standing directly in front of the

brass plate which, Burt knew, read:

CONSULATE OF THE TURANIAN REPUBLIC

There was a big black limousine at the door, which Burt knew to be a consular car.

He was almost three-quarters of the way across the street when one of the bony men spied the little man with the manila envelope. He called his companion, and the two of them started in pursuit.

The little man looked behind, saw them coming, and seemed to cast about desperately for some refuge. No one in the passing throng sensed the swiftly approaching tragedy, except, perhaps, Burt McFey.

Burt saw the little man reach out and drop the manila envelope into a large, white refuse-can at the corner, provided by the City. Then he turned, snarling, at bay, just as the two bony men closed in on him. His hand came out of his pocket with an automatic, and flame belched from it in staccato explosions.

The passing crowds melted away in sudden, panicky terror. One of the bony men dropped in his tracks, lay still. The other had produced a heavy revolver which he raised, and fired at the little man. The little man staggered, went to his knees with blood spurting from his chest; and with his last remaining ounce of strength, he squeezed the trigger of his automatic.

The slugs went wild, ricocheted against the pavement. The bony man stood still, took deliberate aim, a cruel grin on his face. And it was then that Burt McFey fired. He fired a single shot from the automatic in his coat pocket. It caught the bony man in the right shoulder and sent him reeling toward a store front.

Burt darted to the side of the little man, asked eagerly: "Littleton! How are you, old man?"

The little man looked up at him with glazing eyes. He recognized Burt, managed to gasp: "Done for, Mac. The plans—in the—"

"I saw you, Littleton," Burt broke in. "Take it easy, old man."

His mouth snapped shut, his eyes became bleak and gray. Littleton was dead...

He arose from beside the body of the dead man as the crowd, the danger over, began to press in on all sides. The traffic officer from the corner was pushing through, and along the curb the bright, shiny limousine with the Turanian crest on the door had pulled up close. A hatless, gaunt man got out, and the chauffeur preceded him in an effort to get close to the body.

Burt McFey, standing inches above any one else in the crowd, saw that there was another group of people about the body of the man whom Littleton had shot. Of the one Burt himself had hit in the shoulder, there was no trace.

No one in the crowd suspected Burt of having any part in the shooting; they thought he was a passerby, just as themselves. And Burt took advantage of that, melted into the throng as the uniformed officer barged into the small, cleared circle about Littleton.

The hatless man from the limousine reached Littleton's body at the same time. He said to the officer: "This man was a thief. He stole from the consulate a so important paper. You must find this paper for me!" And he stooped, searched along the sidewalk, aided by his chauffeur.

The policeman evidently knew him, for he said: "If he had the paper on him we'll find it all right, Mr. Ginández. Don't worry."

Burt McFey edged back toward the rear of the crowd, his mouth a grim line. Littleton had died in the service of his country. He was a hero. Yet he lay there lifeless, and was called a thief; and no one came forward to dispute the accusation...

THE Espionage Service, thought Burt, was like that. It took

everything that a man had, and gave him nothing in return but the

inner knowledge of the worth of what he was doing. Littleton had

met his death in action. Burt himself might be next—in an

hour, a day, a week—and when the end came it would be the

same; perhaps there would not even be another to say a short

prayer for him as he was even now doing for Littleton.

He backed away from the crowd, entered a small cigar store on the corner, stepped into the telephone booth. From here, he could still get a clear view of the white trash-can into which Littleton had dropped the manila envelope that had cost his life.

Burt McFey inserted a nickel in the slot, dialed a number which did not appear in any telephone book, and which had never been committed to paper by anyone. When he got his connection he merely said: "Twenty-one talking," and waited.

In a moment he was connected through to Major Rand. The major asked anxiously: "What happened? Where are you? I couldn't get a clear view of things from here; the crowd—"

Burt said tonelessly: "I arrived too late to be of any assistance to your friend, sir. He has—left for the West."

There was a moment's silence. The gray-haired, tired-eyed man at the other end knew well enough what that meant. He coughed, said huskily: "You know how I feel about that. I shall do what I can. Did he—"

"He delivered the—package, sir, at a spot near here. The other people are close by, and I may need some help to get it."

"I'm sorry," the major said. "I haven't got a man available. This business has caught me short-handed. It's an emergency that no one foresaw. I've been compelled to spread my men thin, and there isn't another besides yourself left in the city. You'll have to do it yourself, twenty-one, somehow—and for God's sake, don't slip up. You understand? You mustn't fail! I'll be here constantly at the phone."

"I understand, sir," Burt said. "I'll do the best I can."

He hung up, stepped out into the street again. He held his hand low over his coat so as to hide the burnt hole in the cloth through which he had fired the single shot.

The crowd had thinned, and a precinct lieutenant had taken charge. The limousine with the gaunt man was still there, and Burt noted through narrowed eyes that there were half a dozen small, bony men, like the two who had pursued Littleton, lounging about the corner. The envelope had not been found, and they were morally certain that Littleton had not had an opportunity to pass it to anyone else; therefore they were watching the spot like hawks. It would be impossible to go up to that trash can, take out the envelope, and depart without being caught. Burt McFey made himself as inconspicuous as possible, edged across the corner with the moving crowds that were being shuttled around the two bodies by a squad of patrolmen.

He walked south on Broadway, and from where he was he could see the moving electric sign on the Times Building, which flashed the latest news to the public as fast as it occurred. His eyes followed the moving strip now to read:#

TURANIAN CONSULATE ROBBED ON EVE OF DELICATE NEGOTIATIONS WITH WASHINGTON... VALUABLE PAPER STOLEN FROM DIPLOMATIC POUCH IN HALLWAY BY THIEF WHO IS KILLED ON BROADWAY WHILE MAKING ESCAPE... TURANIAN CONSUL DEMANDS INVESTIGATION... DECLARATION OF WAR MAY BE HASTENED BY INCIDENT...

Burt took his eyes from the moving news sign. War with

Turania. It sounded ridiculous on the face of it. Yet he knew

that war was almost certain, knew also that the little Central

American republic, recently formed by secession from two other

countries, followed by bloody civil war and the accession of a

dictator, had something up her sleeve that made victory certain.

Rumors had leaked through, but nothing definite; rumors of a war

plan that was irresistible—that would beat the powerful

United States to its knees within twenty-four hours. It had been

Littleton's job to get that envelope out of the pouch...

WELL, Littleton had done his part. Now it was up to Burt McFey

to do the rest. It might be that the envelope contained nothing

of importance; it might be that the rumors amounted to nothing.

Yet, Turania was blustering; seeking a quarrel; there must be a

reason for it. That envelope had to be recovered.

Burt turned casually, started back toward the corner. Those men were still on watch. One was leaning against the trash can, all unaware that the thing he sought was under his elbow. The morgue wagon had pulled up at the curb, as well as an inspector's car from headquarters. The police were working quickly, efficiently, to clear the street, so that the early theater-goers should not find their path to an evening's pleasure obstructed by tragedy.

Burt's mouth was drawn into a bitter line. How easy it seemed to just go up to the inspector, say: "That envelope is in the white trash can. It contains plans that may mean the ruin of our country. I will take it, and we can open it. If the envelope contains only harmless material we will return it."

How simple! And how impossible! Diplomatic immunity is the hardest shell in the world to crack. Until war was actually declared, the property of the consul of Turania was inviolate. It was an old game, diplomacy, and the rules had grown with the world. Thousands of men had died because of those rules, and Littleton would not be the last.

Burt McFey turned the corner into the side street, and his eyes lit with sudden inspiration at sight of the white-wing wheeling a hand-truck along the curb, sweeping rubbish into it from the gutter. The street-cleaner was working fast, evidently in a hurry to get through and go home.

Burt stepped up to him, said: "Say, friend, how would you like to make ten dollars?"

The street-cleaner looked up at him suspiciously. "What you want, mister?"

Burt took out a crisp ten-dollar bill, flashed it before the other. "Come over here with me. I want to talk to you." He motioned toward a dark alley between a theater and an office building.

The street-cleaner said: "Nix, mister. You get to hell outta here or I call a cop!"

Burt sighed, put away the bill, and palmed his automatic, showed it to the other. "How would you like to get a slug in your belly?" he asked. "Will you come quiet, or will I give it to you?"

The street-cleaner gulped, glanced around for possible help. Dozens of people were passing. All he had to do was raise his voice. But the sight of the black muzzle of Burt's automatic staring at him was too much. He gulped, said: "I come along, mister. But I got not'in'. I poor man."

Burt said: "This isn't a holdup. You won't be hurt if you don't raise a fuss."

He took the other's arm, led him into the alley, down toward the back where the light from the street hardly penetrated at all. "Now," he said, "all I want to do is change clothes with you for five minutes. I'll bring back your uniform and give you ten bucks. Okay?"

"You gonna get me in trouble?" the white-wing asked. He was still eyeing the gun fearfully.

"No. You can forget all about it after I bring back your clothes."

"I do it," said the white-wing. "You gimme the ten bucks first?"

Burt gave him five. "You get the other five when I come back—provided you keep your mouth shut while I'm gone."

They hurriedly changed clothes, and Burt left him in the alley with the injunction to keep quiet. Then he went out to the curb, took the broom and hand-truck, and pushed it around the corner to Broadway, stopping every now and then to sweep up some rubbish along the way.

At the corner where the rubbish-can stood, two or three policemen were still about, and the watchers from the embassy still kept their posts. Ginández, the man from the limousine, had left. But the others still maintained their hawk-like vigil.

Burt approaching the trash can, said to the swarthy man who was leaning against it: "Excuse, mister. I gotta clean up."

The man scowled at him, but moved away. Burt heaved at the can, dumped the contents into his hand truck, and wheeled it away under the eyes of the watchers.

AS he moved around the corner, he dared not look behind him,

but he expected every moment to hear a hail. Nothing happened.

The man whom Burt had shot had seen Littleton throw the envelope

into the trash can, but Burt was gambling that that man would

still be unconscious, unable to communicate his knowledge...

Around the corner, Burt thrust his hand into the truck, seeking the manila envelope. It had been at the top of the can, and was consequently at the bottom of the truck. Burt had to dig far down before he felt its hard edge, fished it up.

He was close to the alley now, where he had left the white- wing. He paused to slit the envelope, and eagerly scanned the single sheet of paper enclosed in it. It was written in the Savarese code, which Burt and Major Rand had succeeded in breaking only a few days before. The number of letters in the third word of the first line, by their respective numbers in the alphabet, indicated key words in the next five lines. It was the word following each of these key words that constituted the message.

Decoded, it resolved itself into a set of instructions, worded in Spanish. Burt's expert knowledge of the language made it easy to translate the message thus:

From: General Miguel Alcolar,

commanding Turanian Air Expeditionary Forces.

To: Señor Enrique Ginández—

At nine-thirty Eastern Standard Time, the first formation of robot planes will arrive over New York, directed by radio wave from Santa Morenas Airdrome. Since the sphere of control from Santa Morenas will not permit of accurate direction of bombing, you will take over control from the radio- direction headquarters in New York at exactly nine-thirty Eastern Standard Time. The second formation will arrive fifteen minutes later, and thereafter the formations will appear over New York at fifteen minute intervals until the full thousand planes are at your disposal.

From New York, you will direct the robot planes to the important centres of industry in the Eastern United States, turning over control to our radio-directional sub- headquarters as follows:

Two hundred planes to Chicago.

Two hundred planes to Pittsburgh.

Two hundred planes to Bangor, Me.

One hundred planes to Washington, D. C.

You will retain the first three hundred planes for destructive work in and around metropolitan New York. The embassy is to be deserted at nine-fifteen sharp, Eastern Standard Time, as Turania will wire a formal declaration of war to Washington at that time.

You will continuouslyYou will continuously direct the bombings by the robot squadrons until every key spot marked on the map in radio-control headquarters has been destroyed. At ten-thirty you will cease bombing, and await the result of the ultimatum which Turania will wire to Washington. Be prepared to resume bombing if the ultimatum is not accepted, holding the plane squadrons in flight over the nearest body of water. You will receive further instructions by radio from Santa Morenas.

Signed: ALCOLAR.

BURT raised his eyes from the missive. Robot planes! That was

the secret of Turania. No wonder he had seen no pilots at Santa

Morenas. Alcolar, the Dictator of Turania, was using the latest

developments of science—planes directed by radio-control.

To arrive at New York by nine-thirty, they must have started

hours ago from Santa Morenas. They must be on their way now.

Without pilots, they could fly in the very teeth of the anti-

aircraft guns along the border—for if they were shot down

their loads of explosive would cause death and destruction

wherever they fell!

Alcolar had planned well. Within an hour, the United States could be crippled, its key industries wrecked. Cities could be destroyed. A tortured populace would storm Washington by telephone and telegraph, demanding peace—peace at any price. Victory lay within the grasp of Turania. No doubt Alcolar could still direct his squadrons of robot planes from Santa Morenas, even if Ginández did not take over control in New York. His bombings might not be so accurately placed, but they would yet cause untold destruction, the loss of thousands upon thousands of lives.

Burt crumpled the message in his strong hands, started for the alley to free his street cleaner. But he took only a single step, stopped short. A suave voice behind him said: "Be pleased to stand still, Señor McFey!"

Burt turned slowly, saw the gaunt face of Enrique Ginández staring at him from the rear window of the consular limousine. Two other men were in the car beside the driver, and they both had long-barreled revolvers trained upon Burt.

Ginández smiled tightly, said: "I see that Counter-Espionage is furnishing you with a new type of uniform, Señor McFey. Ver-ee handsome. Ver-ee handsome indeed!" His eyes traveled over the white jacket and trousers that Burt wore. "May I invite you to enter my car?"

Burt said: "Hello, Ginández. Did you want this paper?" He raised it, so that it was close to his mouth.

Ginández said quickly: "Do not swallow it, Señor McFey. My men could shoot you before it reached your mouth. And besides, that would do you no good. I already know its contents. That note is but official confirmation of previous instructions. Please to enter the car at once, or my men shall be compelled to kill you—which would be extremely regrettable."

Burt said: "All right, Ginández. You win."

He stepped over to the limousine, entered through the door which one of the men held open for him. He was seated between Ginández and one of the small men, while another sat on the collapsible seat in front.

Almost at once the limousine got in motion, headed east for a block, then north.

Ginández said gloatingly: "That was a so clever trick, Señor McFey—to attire yourself as a cleaner of streets, so that you might retrieve the envelope. It fooled my men completely. Fortunately, I saw you go around the corner, and recognized you, or else I, too, would have been fooled."

Burt grunted, said nothing. He glanced covertly at the swarthy man with the gun who sat at his left. The man was left-handed, and held the revolver across his chest, poked into Burt's ribs.

Ginández went on: "Our great Chancellor, Miguel Alcolar, will bestow high honors upon me for capturing you, Señor McFey. He is anxious to teach you that it is most unwise to destroy Turanian airplanes."

He gently disengaged the paper from Burt's hand, glanced at it. "Nine-thirty! The instructions remain unchanged. We will be just in time. You shall witness the destruction of your country, Señor McFey, then, perhaps, you will receive the personal attention of our Dictator when he marches into New York."

The man on the collapsible seat in front turned around at a word from Ginández, and ran his hands over Burt's person, took the automatic from him.

The limousine turned west at Fifty-seventh Street, sped across to the Hudson River, then swung north for another block or so and pulled up before a low, shed-like structure built along the water's edge. A sign, barely legible in the dark, read:

PAN-AMERICAN YACHT CLUB

Powerful wireless antennae rose from the roof of the structure.

Ginández got out first, and then Burt, urged by the two swarthy men with the guns. They marched into the building after the door had been opened to Ginández' peculiar knock.

INSIDE, there was a dim light which revealed a long row of

machines that resembled switchboards. Before each of these boards

sat a man with earphones, his hand on the handle of a long

pointer. By moving the handle an inch, each operator could bring

the end of the pointer in contact with a metal cap from which two

wires ran into the body of the board. Each of the boards was

numbered, and Burt saw that there were thirty of them, fifteen on

each side of the room. At the rear was a small platform upon

which stood two uniformed guards with submachine guns.

A man in the uniform of the Turanian army came forward as they entered, eyed Burt quizzically, and saluted Ginández stiffly. "Beg to report, sir," he said in Spanish, "that the detonating operators are all at their stations. Our directional finders report that the first formation of robot planes is approaching the battery. We are waiting for you to take over control."

Ginández said: "That is excellent. Tell them not to remove their earphones. I will be ready to order the first detonation in ten minutes. That," he added with a sardonic side glance at Burt, "will be at Governor's Island. Our reports show a full Army Corps is stationed there." He heaved a mock sigh. "Poor soldiers. But it will be an easy death for them. They will never know what happened to them!"

He lead the way toward a staircase at the rear, and the two swarthy men prodded Burt along with their revolvers. Upstairs, they passed another guard with a sub-machine gun, who saluted and let them pass.

Ginández said to one of Burt's captors: "Take Señor McFey into the small room at the end of the hall, Consello. Keep close watch over him. And remember that he is a dangerous man. If he should attempt to do anything that you disapprove of, I advise you to shoot to kill. Our Dictator will be disappointed at not having him alive to deal with—" he shrugged his shoulders—"but if Señor McFey knows our Dictator, he may himself prefer to die by a bullet rather than wait."

He smiled nastily, turned and entered a room at the left. Burt got a glimpse into it before the door closed, saw a huge panel set in the far wall, before which sat a dozen men. The equipment was similar to that in radio broadcasting station, except that there were no glass enclosures.

The door closed behind Ginández and the other swarthy man, and Burt was left in the corridor with Consello.

Consello prodded him in the back, said in Spanish: "Let us go. You heard what the master said. You will be less trouble to me dead than alive."

Burt said nothing, walked down to the end of the corridor, and entered the small room at the end. It had a single window facing on the river, a small desk, several chairs, and a couple of smoking stands that stood upon the floor on wide round bases.

From outside came the dull reports of artillery. Burt knew what that was—anti-aircraft guns were swinging into action. The strange horde of planes must have come up along the coast, out of sight of observers. Now they were spotted, and the long- range guns were going into action; the commanding officers of the artillery not knowing what sort of invasion this was, not knowing that every plane they brought down would carry death with it.

Burt noticed the man, Consello, staring at him. He was dark, with close-cropped black hair, and small eyes set far apart below a low, flat forehead. He was following Ginández' orders, and not taking any chances; for he held his revolver steady, trained on Burt's stomach.

Burt said in Spanish: "Is it permitted that one should smoke?"

The other grinned crookedly. "One may smoke. But the one who smokes will be I." He backed away a step or two, fumbled in his pocket for cigarettes, produced one, then got a match.

Burt watched him keenly, trying to disguise the tautness of his body. Outside, dull reverberations of artillery fire came to his ears as he kept his eyes on Consello.

The swarthy man lit the match by striking his fingernail across it, then applied it to his cigarette. For a moment, the flame obscured his sight, and in that second, Burt McFey reached out with a lightning-like motion, seized the heavy brass smoking stand beside him, and swung it in the air.

Consello's revolver crashed, Burt felt a hot stinging scorch high up across the left side of his chest. He was thrown to the left by the shot, but it did not affect the deadly precision of the blow he had already aimed at the other's head.

The smoking stand crashed down with a sickening thud upon Consello's skull, and the man went down under it, a bleeding, gory mess...

BURT reeled for a moment, felt an overwhelming sense of

nausea. But he saw a vision of a horde of planes swooping out of

nothingness upon a defenseless nation, and bit down hard on his

teeth so that the muscles of his jaw bulged. He fought back that

wave of nausea, stooped and seized the revolver, tore open the

door of the room.

At the far end of the corridor, he saw the guard with the sub- machine gun swinging toward him, and he snapped a single shot from Consello's revolver that caught the guard above the heart. The man had hardly hit the floor when Burt was beside him, gripped the sub-machine gun, and swung toward the door of the room he had seen Ginández enter.

The sound of the shots had aroused those down below, and Burt heard shouts, heavy feet on the staircase as he twisted the knob, crashed into the room. The dozen men at the panels, with their backs to the door turned, sat transfixed at sight of the sub- machine gun. Ginández half-rose from the huge desk near the window at which he sat, and the swarthy man beside him, who accompanied Burt in the limousine, reached to his shoulder- holster for a revolver but stopped as Burt swung the sub-machine gun in his direction.

Burt closed the door behind him, felt for the key and locked it just as a rush of feet sounded in the corridor outside.

Ginández shouted in Spanish to the men at the panels: "Matadlo! Kill him!"

Several of the men sprang from their chairs, and guns appeared in their hands. Burt's mouth tightened into a thin line. He hated to do this; it was massacre. But it was the only way. He pressed the trip of the machine gun, fanned it around the room, and a stream of lead mowed down that row of men at the panels as if they had been stalks of wheat before a scythe.

He swung to the left in time to see the swarthy man with his revolver out, and he kept his finger down on the trip until the drum was empty.

Ginández and the swarthy man were practically cut in half...

Burt sprang across the room to the desk, glanced down at the map which was set into the top. It was a map of the eastern United States, and upon the surface of the desk was a lever that moved over various sections of the map. The pounding on the door increased, and Burt heard a voice order:

"Bring up the machine guns. We will blast him out." The Spanish words sounded strange and far away, as if coming from another world...

Burt bent and studied the map. He was bleeding like a stuck pig, and the white suit was saturated with blood. Sharp, cutting pains raced across his chest. His brain was reeling with nausea and weakness. From the distance the dull thunder of the anti- aircraft guns continued. In the corridor they were bringing up machine guns to blast him out. Within the room with him lay more than a dozen men whom he had just mowed down. Yet Burt McFey steeled himself to study that map, forced his jumbled brain to think about that swarm of robot planes coming like eagles to swoop down upon the city.

Dimly, as in a fog, he noted that the big lever was pointing to a spot on the map that resembled Manhattan Island. To the right of Manhattan on the map was a blue expanse that was the Atlantic Ocean.

Not knowing whether or not he was doing the right thing, Burt swung that lever so that it pointed out over the ocean.

Then, with all his remaining strength he brought his fist down on the lever, so that it bent. He tried it again, found that it could not be moved, and grinned through his pain...

He staggered to the window, climbed over and out, dropped into the water below just as a hail of lead tore through the door of the room.

His entire left side was numb now, and he felt like going to sleep in the water. About him, the river was rapidly being stained a deep red. He turned over on his back, managed to float the few feet to the jetty upon which the house was built. He found a short ladder leading up from the water, struggled up it and dropped, panting, in the shadow of the building...

TO his dimming senses, there came an ominous, steady, dismal

droning of motors. Glancing skyward, he discerned the huge air

armada—hundreds of planes that literally filled the sky;

with not a pilot in any of them.

And even as he watched he saw them veering out eastward toward the ocean, flying squadron by squadron in perfect echelons of Vs.

The coast-guard guns were still thundering, but the planes were so high that the barrage failed to reach them.

From the room above, there sounded more bursts of machine gun fire.

Burt watched the dark armada with glazing eyes, saw the last of them sailing out of sight to the East.

And from the street along the waterfront came the shrill sound of sirens as a riot car pulled up opposite the yacht club building, brakes squealing. Uniformed men, each carrying a short- muzzled Thompson gun deployed from it.

Burt forced himself to his feet, waved to the officers, a red, dripping, bloody spectre in the night.

"United States business!" he shouted as he reeled toward them. "Shoot to kill. Those men in there are enemies of the—"

He staggered, fell unconscious as a fusillade poured from the house.

The uniformed men took to cover, opened up with machine guns, riddling the wooden structure. Another riot car came to their assistance, and the battle waged for minutes, with Burt McFey lying there in the mud between the two fires...

IT was an old, gray-haired, tired-eyed man in the uniform of a

major of intelligence who crawled out after him, dragged him back

under fire.

And it was into the ear of Major Rand that Burt McFey later babbled deliriously in the hospital—babbled of a thousand eagles flying out to sea, and of a little lever, and of the souls of a dozen men whose bodies he had cut in half with a machine gun.

The major sat by his bedside far into the early hours of the morning, listening with a set face and dim eyes, waving away impatiently the nurse who came to tell him that Washington was calling on the phone, that the Secretary of War himself was at the other end.

And at last, when Burt McFey came out of it, the major heaved a deep sigh, and wiped his eyes with the back of his hand.

The attending surgeon probed and felt, and took pulse and consulted the chart, and at last said: "He's safe, Major. A good rest and he'll be all right again."

Major Rand looked down and his eyes met the eyes of the patient. "Burt," he said matter-of-factly, "they're going to give you a Congressional Medal of Honor."

And Burt McFey, lucid for the first time in twelve hours, exclaimed: "Holy Mackerel, Major! I've got to find that white- wing. I owe him five dollars and a new suit!"