RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old travel poster (circa 1920)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old travel poster (circa 1920)

Charles Gilson (1878-1943)

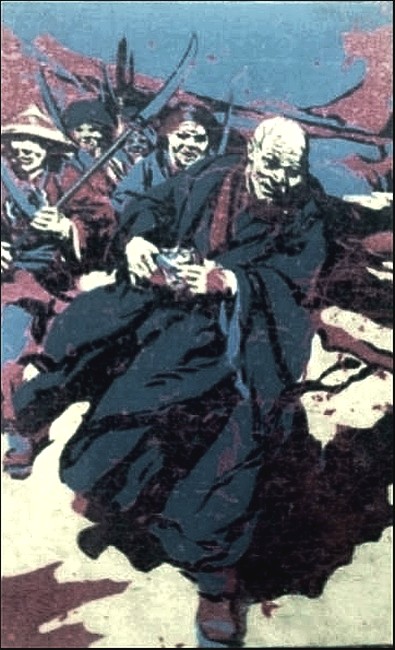

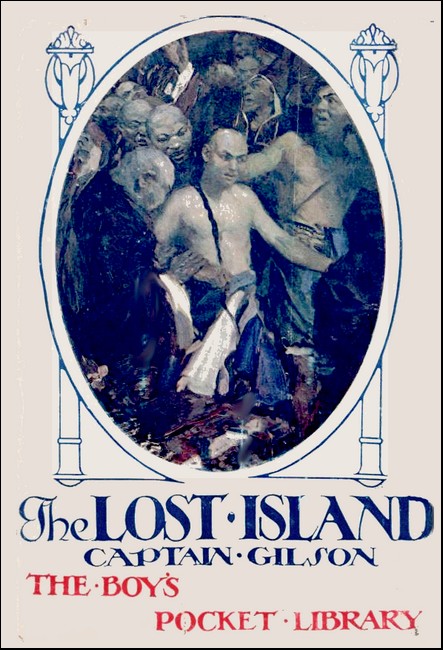

Book Cover: "The Lost Island,"

Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1911

Dust Jacket: "The Lost Island,"

Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1917 edition

Title Page of "The Lost Island"

The man who was to have summoned the East to arms rolled over upon his side.

"The Lost Island" was the first story I ever wrote. It appeared four years ago in serial form in The Captain, to the editor of which magazine I am indebted for my introduction into this particular field of literature, as well as for much encouragement and advice that did me good. The story, as it now stands, is revised and considerably enlarged.

I found, on sitting down to the task of revision, that in these four years I have learnt—not a great deal, perhaps,—but, at least, something concerning the use of my tools. That much was inevitable, and is so, in every case, with the man who sedulously follows a business that he loves. It is the same at school, with cricket and football, as well as irregular verbs; it is the same with a plumber, and also a writer of books. The precise length of time it takes to gain proficiency must be in inverse ratio to the love one has for one's work. And of this much we may be sure: that if a pleasant task is badly done, all we lack is experience which it is very easy to gain. —C.G.

Of The Daring Adventures Of Thomas Gaythorne

And Of The Origin Of The Secret Society Of Guatama's Eye

IN the same year that Napoleon Bonaparte crowned himself Emperor of the French, a party of Jesuit fathers set sail from Canton, and, at the imminent risk of falling a prey to the pirate junks which then cruised the Long River, penetrated into the heart of the province of Kwangsi. Thence, leaving the river valley, they proceeded on foot across the uplands of Nan-Ling, and came upon the great city of Chung-King, which stands at the head of the Yangtse rapids. From Chung-King they went north, as far as the Pe-Ling mountains; and then, turning to the west again, they crossed into the region of the great lakes of Amdoa, where at that time no white man had ever been.

Among this party was an Englishman, of the name of Thomas Gaythorne, who was no more a Jesuit father than his appearance warranted. He was a wrinkled, hardened, little man; old in face, but youthful in his limbs. He was dressed as a Chinese, and had grown such a pig-tail as became the envy of the villagers they passed upon the road. On this account he found no difficulty in passing himself off as a celestial: the more so since he could speak both the Cantonese and Mandarin dialects with equal fluency, besides having a remarkable knowledge of Sanscrit and many of the hidden languages of Central Asia.

The history of Thomas Gaythorne will never now be written. Had he lived, he perhaps might have written it himself, though it is more than likely he would not. For he was above all else a silent, undemonstrative man, who took more readily to action than to words. It was rumoured that he had crossed into China from Burmah; had journeyed to the very end of the Great Wall, and had even served with Chinese pirates on the Malay coast and against the Dyaks of Borneo. But how much of this is true no one will ever know. For, when he returned to England and married, he told his wife next to nothing; but remained seated at his fireside, with his thoughts on the other side of the world, and never a word upon his lips.

It is difficult to conceive why such a man married at all, and certain it is that his marriage met with but indifferent success. His life had been too full of wild adventure for him to become easily domesticated; and a feeling of restlessness took hold upon him, and in the end altogether got the better of his judgment. He disappeared in the night, before his son was ten months old, and shipped again to the China Seas, with no other luggage than a brace of pistols, which had lain in the drawer of his writing-desk, and a miniature painting of his wife.

He had not been long in Canton when he fell in with the Jesuit fathers, who were only too glad to avail themselves of his services. He guided them to the lower slopes of the Pe-Ling mountains, but then found himself in a land in which even he was a stranger, and they were forced to rely on the information of the inhabitants. They had reached the plateaux of Central Asia, a country of far-reaching plains, terminated by great blue mountain ranges.

Day after day the little party travelled on through this bleak and savage country, until finally they came upon a wide lake, surrounded by a forest of maple trees. Breaking through the forest, they discovered a ruined Joss-house, or Shama temple, on the shore. In the centre of the lake was an island upon which stood a Lama Monastery, four storeys high and solidly built of mountain stone, with a tall pagoda tower at its southern extremity.

Here the fathers decided to remain, taking up their headquarters at the Joss-house. The valley was to some extent cultivated, and more thickly populated than most of the surrounding country. The inhabitants appeared quite friendly; and the Jesuits immediately set about preaching their gospel and exploring the district, of which they made those excellent maps upon which the Royal Geographical Society relies to-day.

They even gained the good-will of the lamas themselves, who frequently came across from the island to visit them. It was by Gaythorne that the monks were chiefly attracted; they marvelled at his knowledge, and would remain for hours seated around the little Englishman, while he enlightened them upon the doctrine of Buddha, as preached in Upper India and in the countries to the south.

They made no attempt to conceal their admiration of all this learning; and Gaythorne, encroaching on their friendship, again and again asked to be allowed to visit the Monastery itself. This, however, was more than could be granted to a European: it was strictly forbidden by monastic law; and each time their refusal was more definite.

But Gaythorne was not a man to accept complacently such a denial. He possessed both an inflexible will and a high contempt for danger. Accordingly he purchased a stock of wares in jade, bronze and ivory, and disguising himself as a Manchu pedlar, rowed boldly across to the Monastery.

He was admitted into the outer courtyard without question. He spoke the northern dialect to perfection, and had stained his skin to the dust-coloured hue of the tribes north of the Great Wall. But, unfortunately for him, this was not sufficient to disguise his identity; and, while bargaining for the sale of his goods, he was recognized by an evil-looking priest, of the name of Tuan, whom he had often seen at the Joss-house.

He was instantly made a captive, and led before Dai Ling, the Head Priest. He proffered nothing in his defence: he knew enough of the lama brotherhood to be sure that his doom was sealed; and when sentence of death was passed upon him, he received it without a word.

Soon after daybreak on the following day, he was led into the quadrangle of the Temple, where he was to be beheaded, beneath the shadow of a great image of Buddha, sixty feet in height. He was ordered to strip himself to the waist; and this he did, perfectly calm and self-possessed, showing the monks that an Englishman could meet his death even as stoically as a Mongol.

Suddenly, as he bowed to receive the stroke, an exclamation of surprise broke from the whole assembly. The executioner paused in his work: every eye was fixed upon the back of Gaythorne's left shoulder, where he had carried a red star-shaped mark since the day of his birth.

This, as every lama knew, was the sign of a particular line of Buddha's apostles. The thought flashed upon the little man's mind in the hour of his greatest need. He rallied the credulity of the monks, calling upon them mockingly to take the life of one of the patriarchs of their own faith, under the very eye of the Buddha himself.

Thereupon arose a great deal of high talk, during which every one in turn closely examined the mark. The Mongolian priest, Tuan, with a few others, was for going on with the execution; but the majority, including most of those who had visited Gaythorne in the Joss-house, believed the sign, and thus accounted both for the Englishman's learning and his presence in their midst.

The Head Priest, who was a benevolent old man, agreed with the majority; and it was finally decided that Gaythorne should be kept a prisoner-at-large within the gates of the Monastery.

Thus he remained for nearly two years, buried alive upon an islet in the centre of an unknown continent.

But he soon settled down into the life of the monks. He worked with them in their studies, and chanted at his little desk in the great Temple, on the right hand of Dai Ling himself. Whenever the Temple bell rang for prayers, the European priest, Thomas Gaythorne, with his shaven head bowed in reverence, was always among the first to be seen hurrying across the courtyard. He wrote philosophical treatises which were much admired among the brethren, and are, in fact, even to-day universally read throughout the Chinese Empire. He became "teacher," and instructed a school of "novices" in the advanced doctrine.

In course of time, this pious behaviour gained for him the respect of many of the lamas, especially of Dai Ling, the Head Priest, who came to regard him almost in the light of a son. This meant much to the prisoner. For Dai Ling had almost supreme power: he was a Khutuktu, or Archbishop; that is to say, he ranked next to the two great lama-popes, and was supposed to hold office by virtue of divine incarnation.

Gaythorne himself was presumed to be the re-embodiment of the soul of a former saint. But such honour was claimed by most of the senior lamas; and there were many who were diffident in believing the testimony of the birth-mark, by reason of Gaythorne's nationality.

Tuan's eyes especially were ever upon him, for the Mongolian priest remained openly hostile. Gaythorne knew that he would be able to do nothing against the fierce anger of the lamas, should the tide ever turn against him; and therefore, with a growing mistrust of Tuan, and being thoroughly weary of his long imprisonment, he was more than anxious to be gone. Escape through the locked and guarded gates was, he knew, impossible. But chance, at last, gave him an unlooked-for opportunity.

Among the dusty archives of the Monastery a boy acolyte, or novice, sent thither upon an errand, found a fascicle of papers, written in an unknown language. He took it to his teacher, who, being able to make nothing of it, showed it to Dai Ling himself.

The Head Priest had never seen the document before. It was written in one of the dead languages of Central Asia, Sanscrit in root though very different in form, containing many words derived directly from the Persian. However, he could decipher enough to recognize it as a translation of one of the most famous monographs of the great philosopher, Ačvaghosha.

The discovery was one likely to influence the whole of Asia. For no trace of either the original or any other translation had ever before been found. The monograph was known to be of the greatest importance, being frequently referred to in the writings of contemporary and subsequent sages.

The difficulty was to get it put into Chinese, and that within the Lake Monastery itself, so that Dai Ling and his priests might reap the credit of such a work.

When the Englishman said that he could translate it, the old Head Priest actually embraced him in his delight. Though Gaythorne was ignorant of the language itself, he said he knew all the sources whence it was derived, and could, even at a glance, glean some notion of the meaning of the characters.

Gaythorne waited patiently until Dai Ling was at the height of his eulogies, and then played his trump-card for freedom, with that boldness which appears never to have left him. He promised to translate the document on one condition alone: that Dai Ling would not only set him free, but grant him, as a reward, the precious "Casket of Heaven," from the shrine of the sanctum of the Temple.

This Dai Ling could not do without the consent of the Council of the Monastery. The superior priests were therefore called together; and Gaythorne was summoned before them. Tuan was furious; he suggested that Gaythorne should be forced to do it under penalty of torture. But, for this, Dai Ling loved his prisoner too well, and the other priests had seen enough of the Englishman's spirit to know that such threats would have no effect. The little man stood boldly before the Council, and swore that for no other reward would he ever write a word. He was as shrewd as he was brave. When he saw that the priests wavered in their decision, he reminded them that perhaps another copy would some day be found, in one of the numerous libraries of the Buddhist vihāras, and the credit of the translation would accrue to another Monastery.

Therein he touched a keen chord—the jealousy of rival priesthoods. They agreed; and Gaythorne knew that he held their affections too deeply to fear treachery from any, save Tuan. Yet he took the precaution to secure a written agreement from Dai Ling, signed by the Head Priest himself and stamped with the red seal of the Lake Monastery, wherein it was stated that—"'The Casket of Heaven,' containing the gem commonly known as 'Guatama's Eye,' was the rightful property of Thomas Gaythorne and his heirs." This was to be handed over to him on the completion of the translation.

He was allotted a small chamber, high up in the southern tower, where he could work undisturbed. His food was brought him daily by an acolyte, beyond whom he saw no one for months. With Chinese pertinacity he worked for his freedom, yet taking pride in the composition, and fashioning rare Chinese characters with the ease and rapidity of an expert.

One night, exhausted by a hard day's work, he flung himself down upon his matted couch to sleep. He was never able to do much more than fifty characters a day, owing to the extreme difficulty of translating a language with which he was only partially acquainted; and this day's work had been more mystifying than usual. He was soon fast asleep, and had probably been so for an hour or two, when, without actually opening his eyes, he gradually became conscious that he was awake and that there was a light in the room.

Without any movement of his body, he looked up from under his lowered eyelashes, and beheld seated at the table, before the pages of his manuscript, the stooping figure of Tuan.

The light from an oil-lamp was shaded from the sleeper's eyes, and fell full upon the sinister countenance of the Mongolian priest, who was busily engaged in writing, an ink-box at his elbow. Clearly, Tuan was copying the day's work; doubtless he had done so night by night for some time past. The whole of his perfidy was apparent. Once he had a private copy of Gaythorne's work, it only remained for him to destroy the Englishman's translation and then accuse Gaythorne of failing in his task, hoping thereby to bring upon him sentence of death. As Gaythorne regarded the priest's villainous face, he had little doubt that Tuan would not scruple even to murder him, if opportunity occurred.

Now Thomas Gaythorne may have been impetuous enough to have run away from his home, but he had never passed unharmed through all the adventures of his life had he acted rashly upon such occasions as these. Tuan, as most pure Mongolians are, was of large and muscular frame, and stood a good head taller than the Englishman. Also, Gaythorne saw that the priest carried a naked sword at his girdle.

Closing his eyes, he set himself to think. Surprise was beyond the question, since Tuan had taken care to place himself facing the sleeper. If he continued to feign sleep, informing Dai Ling on the morrow, Tuan would only deny the accusation, and no direct proof, beyond word against word, could be brought against him. Most men would have been content with this; but Gaythorne, who had the heart of a paladin, resolved to take Tuan red-handed.

A large sam-shu bottle of blue china stood near the bed. Gaythorne snored loudly, and turned upon his side, as a sleeper frequently does, and in doing so, extended his hand to within a few inches of the bottle. Tuan looked up from his work and eyed him maliciously for some minutes. Gaythorne, continuing to breathe heavily and slowly, appeared to have again sunk into the deepest slumber.

Tuan, turning once more to his copying, was in the act of trimming his pen, when suddenly the sam-shu bottle caught him fair between the eyes. He sprang to his feet with a cry of pain. But, before he had time to recover his senses, the little man was at his throat like a terrier, and had flung him heavily backward. In a second Gaythorne whipped the sword from the priest's waist, and with one blow stunned him with the hilt.

Tuan's cry had aroused the priests who slept in the tower, and, one after the other, they came hurrying up the steps. At Gaythorne's request, Dai Ling was immediately sent for; and, when the old man arrived, Gaythorne made Tuan's treachery known to them all. There was no doubt of his guilt: the copied manuscript lay upon the table; and, upon the order of the Head Priest, the culprit was immediately thrown into the dungeon of the Monastery.

On the following morning, Tuan was brought before the Council. Dai Ling spoke savagely and to the point. Tuan had merited death, he said; and if he put it to the vote, he had little doubt that such would be his sentence. Yet he was minded to spare him that he might continue to live in disgrace—an unfrocked lama priest.

So Tuan was dismissed from the Lake Monastery; and the great, grim walls knew him no more. The priest-ferryman, who rowed, him to the lake shore, told Gaythorne that words of vengeance were upon the lips of Tuan when he went out into the world. But Gaythorne only laughed, and went back to his work in the tower.

At last the task was ended; and a grand meeting of the whole brotherhood and undergraduates was called in the great hall of the Temple. Dai Ling, in the priestly robes of his high office, took his place at his raised desk, the superior priests ranged beneath him in order of seniority. When they were all assembled, a chant, in deep guttural notes, supplemented by the high alto of the acolytes, swelled through the dimness of the Temple nave. The priests of the Devil Temple near by sounded the great brass trumpets—some of them thirty feet in length and supported on swivels—that all evil spirits might be scared across the water. And then, when all was silent again, the little wizened Englishman, with a scroll of papers in his hand, stepped boldly into their midst.

In a clear voice, that carried to the innermost recesses of the hall, where eight-year-old acolytes listened with open mouths, he read the word of Ačvaghosha, the greatest teacher of the Mahāyāna.

No other Englishman ever did the like of that which Thomas Gaythorne did. He held them breathless from beginning to end. Once or twice he paused in the reading; and looking up to see what effect it had had, he heard a deep, long breath, slowly drawn in on every side. Then he felt his blood rush wildly through his veins; his eyes glistened with pride, in the half-light of the Temple hall. The bravest men are often those who have the keenest sense of the dramatic: they will risk their lives for effect, even though they have no other audience than themselves. Perhaps Gaythorne was one of these; and perhaps it was of such a moment he had dreamed, when he sat silent at the fireside in his little home in England.

When he ended in Ačvaghosha's words: "Such is the doctrine: may its merit be spread throughout the world," a great shout went up from the assembled monks. One and all, they realized the gift that had been placed within their hands, and rushing from their places, they closed around Gaythorne, calling him a benefactor to the human race and nearly suffocating him in their enthusiasm.

Then Dai Ling raised up his voice, and all eyes were turned towards him. He spoke with eloquence, for the moment was one of inspiration. He said that the Englishman had done a great work. Day and night had he toiled; and with their own ears had they heard the product of his labour. The new doctrine would spread like fire throughout Asia; and all eyes would be turned to the Lake Monastery, as the source from which it sprang. Then he went on to say how the Englishman had asked for the "Casket of Heaven" as a reward; and no single voice was raised in protest.

So Gaythorne handed over the scroll to his old friend, the Head Priest, who received it on behalf of the Monastery, and then dismissed the gathering.

The monks went rapidly to their quarters, talking excitedly of the treatise. The superiors discussed its various aspects in a learned manner; and even the little acolytes made pretence to have understood.

When Dai Ling and Gaythorne alone remained in the Temple, the Head Priest, without a word, motioned Gaythorne through the brass-bound door into the inner sanctum.

And there, at the feet of a little golden Buddha, lay the "Casket of Heaven." Years ago—no one knew how—it had found its way to the Lake Monastery from Upper India. It was about the size of an ordinary travelling clock and made of beaten Indian silver. A great deal of its value lay in the precious stones with which the sides and lid were studded. Rubies, emeralds and diamonds adorned the outside; but inside, in the centre of the convex bottom, was set the greatest sapphire of the world, known as "Guatama's Eye." Each of the smaller gems would have fetched a good price in the markets of the civilized world; but the value of "Guatama's Eye" was beyond estimation.

When Gaythorne took the Casket from Dai Ling, his hands trembled. No one will ever know what dreams of avarice were in his mind. Certain it is that from that moment he had but one desire: to cross the wide world again and return to his wife and child, the master of untold wealth.

He secured the sealed Agreement from the Head Priest; and, with this in his possession, left the Monastery a few days later. The brotherhood bade him an almost tender farewell; and he was even in a way sorry to leave them. But the joy of being free in the world again soon got the better of this feeling; and, as he rowed himself across the lake in the bright sunshine of the day, his spirits rose by leaps and bounds, and he burst into an old song that had been all the rage in London in the days of his youth.

He landed near the ruined Joss-house; but the Jesuits had apparently long since gone, and no sign of them remained. He remembered how he had there disguised himself as a pedlar, and rowed over to the Monastery with a fast-beating heart. He marvelled at all that had passed since then, and clasped the Casket tight beneath his cloak to assure himself that it was not all, even then, only a dream.

At the first village he was directed to the nearest Prefect, whom he found in a small walled town, or hsien, at the base of the Pe-Ling mountains. The Prefect had no objection to granting him a passport, provided he paid for it, which, owing to Dai Ling's generosity, he was fortunately able to do. On the receipt of additional remuneration, the Prefect granted Gaythorne the services of four soldiers, armed with great Yunnan swords.

Thence he marched due south; and finally reached the Yangtse Valley, some miles below Chung-King, through which town, it will be remembered, he had passed with the Jesuit fathers.

That night his party camped upon the banks of the swollen river. Near at hand, a dilapidated sampan, or Chinese river boat, lay moored, apparently without an owner, straining at its painter with all the strength of the current.

Soon after they had arrived the sun sank behind the hills. Gaythorne, dead tired with a long day's march, lay down and tried to sleep, using the Casket, wrapped in a rug, as a pillow. But the roar of the rapids sounded incessantly in his ears; the mosquitoes buzzed around him, stinging his face and hands, and, in the hot damp atmosphere, after the freshness of the highlands, he found sleep impossible.

He was lying with his eyes wide open, thinking of the great fortune that lay beneath his head, when he heard a twig snap sharply, close behind his ear.

He immediately jumped up, and awoke the soldiers; and at the same moment, a party of men, shouting wildly and brandishing swords in the air, rushed into his little bivouac. By the faint light of the moon he could see that they were for the most part turbaned brigands from Honan, the fighting province of China; but among the foremost, and presumably the leader of the band, he recognized the tall form of the Mongolian, Tuan.

What followed was the work of seconds. The escort, seeing themselves outnumbered, took to their heels, leaving Gaythorne to face his assailants single-handed. His pistols were loaded; but they were beneath the rug with the Casket. As he stooped down to seize them, Tuan, with a shout of triumph, dealt him a blow with his sword. The stroke missed his head; but the weapon buried itself deep in his shoulder. He fell back with a groan; while Tuan, guessing where the Casket was, threw aside the rug, seized the treasure, and disappeared with it into the darkness.

Gaythorne had now no other hope than that of saving his life. The swords of the bandits were on every side, closing him in upon the river bank. Yet, face to face with death and wounded as he was, his presence of mind never deserted him. With his last remaining strength he sprang into the sampan and loosed it from its moorings.

He had but gone from one danger to another, wherein death was almost equally sure. The bubbling, seething torrent swept the cockle-shell of a boat down stream, on the breast of its foaming tide. The sampan twirled and twisted like a top, and flew onwards in the darkness of the night, sometimes springing like a salmon clear of the surface of the water, sometimes burying itself, almost to the gunwales, in the plunging stream. The boat contained neither rudder nor oar; and, even if it had, such would have been of little use. It lay at the mercy of a mad, remorseless river. Gaythorne remembered the rocks, scattered in mid-stream, and, with the blood dripping from his wound, awaited his fate, clinging to the arched matting which projected across the stern. And then his hold gradually became less firm; his head grew dizzy from the incessant pirouetting of the boat; his knees gave way from under him; and he fell beneath the matting in a faint.

When he came to himself, it was broad sunlight, and a Yangtse fisherman was bending over him.

"Where am I?" he asked.

"Chung-Shan," came the reply.

He had been dashed down fifteen miles of one of the most dangerous reaches of the rapids, in an unserviceable sampan; and had yet survived.

"How did I get here?" he asked, with a voice weak from loss of blood.

"Your sampan came past me, and I caught it," answered the fisherman, with Chinese brevity.

At that, the whole truth came back to him; and the brave little man, whose face had never before been known to show any signs of weakness, became drawn and haggard-looking. His lips quivered for an instant; and then he buried his face in his hands.

It cannot be said that he wept, but he remained thus for some time, motionless and silent. As has been said, he was by nature an undemonstrative man, but, for all that, perhaps, seeing the end so near, he may have prayed.

When he had finished, the fisherman bound up his wound, after a clumsy fashion of his own. Yet the office was kindly meant; and Gaythorne thanked him, and offered him all the money Dai Ling had given him if he would take him down to the coast.

The fisherman willingly agreed, and set sail that very afternoon, shooting the rapids in his two-masted junk with the skill of one who earned his bread upon the great treacherous river, while Gaythorne lay in the prow, and rapidly fell into a burning fever.

By the time they had reached Woosung, little of life remained in the once sturdy frame of Thomas Gaythorne. A packet, flying the red ensign of England, lay anchored in the roads; and Gaythorne, in a voice that was hardly audible, asked the fisherman to row across, and bring one of his countrymen over to see him.

He had not seen a European for two years; and a faint smile spread over his face when he recognized in the captain of the ship an old friend, Evans by name, with whom he had once sailed. The captain had brought his medicine-chest; but the little he knew of medicine was sufficient to tell him that no human aid could now save Gaythorne's life. And Gaythorne himself owned as much. He gave Evans the address of his home in England, the miniature painting of his wife, and a scroll of paper, covered with fantastic Chinese lettering and sealed with a great red seal. He asked the captain to give his wife these, and tell her of his death; and, after that, he never spoke again.

Thus ended the adventurous life of the little wizened hero. No one, until quite recent years, ever realized what he accomplished. Evans raised his cap respectfully in the presence of death, and the fisherman counted out the money Gaythorne had given him; but neither knew, either then or afterwards, that the man they had seen die was the richest in the world. Evans buried him on the shore; but they have built the terminus of the short railway-line to Shanghai over the spot. So that no trace of his grave can now be found.

This story was the origin of one of the greatest secret societies of all China. The Lake Monastery soon heard of the murderous onslaught of Tuan—for news travels fast in a land of a rural population—and no pains were spared to track the culprit. The Lama Brotherhood, from Canton to Peking, were set hot upon his scent; and, when one of his hired Honanese ruffians was caught, Tuan, finding the whole Chinese Empire too small to hold him in safety, managed to sell one of the jewels of the Casket, and chartering a junk on the profits, sailed for the Southern Seas.

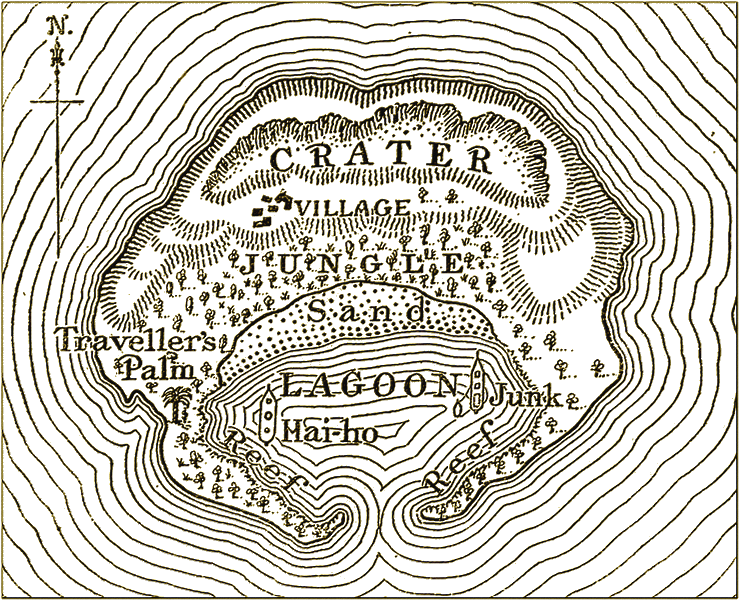

But the lamas soon learnt of his escape, and interrogating the sailors upon their return, heard that Tuan had been landed on an island in mid-Pacific. One of the sailors drew up a rough chart of its position, attaching a full description of the place. It was described as being half mountain and half coral-reef, the latter forming a wide lagoon on its southern side; the reef and the low-lying parts of the island were thickly covered with cocoa-nut trees, and the mountain, which was evidently an extinct volcano, was described as resembling "a broken bowl." The island had not appeared to be inhabited, but doubtless Tuan had there hoped to fall in with an Australia-bound ship, and thus cut off all trace of his whereabouts. However, since the chance of sighting a stray ship in such solitary waters was indeed remote, three junks were fitted out at the expense of the Monastery, and sent in search of the lost Casket; for the lamas believed that the sealed Agreement had perished with its owner, and were not above keeping the whole matter a secret, in case the Casket should be found. But, in course of time, the junks returned empty handed, having searched the South Pacific in vain; and all hope of ever finding Tuan was ultimately abandoned.

The sailors of the junks and the Honanese brigands had already guessed something of the truth of the story of Thomas Gaythorne and the loss of Guatama's Eye. There was no way out of the matter—if the credit of the Lake Monastery was to be taken into consideration, both in the matter of the real authorship of the translation and in the event of the Casket being found—but to bind them all over to secrecy; and thus it was that The Secret Society of Guatama's Eye came into existence.

When Dai Ling died, he was buried with much pomp and circumstance in the Temple of the Monastery; and his memory was honoured throughout the length and breadth of China.

Nevertheless, the Secret Society continued to live; and as all secret societies in China invariably do, in course of time greatly increased its numbers. Successive head priests became ex-officio presidents of the society, holding possession of the chart of the island, where the Casket of Heaven was supposed to be. Since the chart had been proved to be inaccurate, emissaries of the society were set to watch the yearly publications of the British Admiralty, revised upon the observations of H.M. surveying ships in the Southern Seas.

But no record of the Lost Island ever appeared until many years afterwards, when David Gaythorne, great-grandson of Thomas, accompanied by a gigantic Irishman, ran up the steps of the Admiralty and formally reported its existence, giving its position, by longitude west and latitude south, with such convincing exactitude, that the Admiral commanding the Australian station was then and there ordered to dispatch a cruiser to discover it officially, although the whole story had then for six weeks been the talk of all the world.

Of A Minor Discussion And How The Mate Settled It

NEARLY a hundred years had elapsed since Thomas Gaythorne breathed his last among the mud-flats of the lower Yangtse Kiang. There had been three successive Gaythornes since then:

Firstly, his son, who entered the army, rose to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, and fell in the foremost of the fighting at the Alma.

Secondly, his grandson, the manager of the Plymouth branch of a well-known bank, who pricked the vanity of his superiors by taking upon himself more responsibility than they were willing to grant him. Consequently, when, through no fault of his own, he was deceived in the matter of a large advance, the bank, considerably out of pocket over the transaction, were pleased to dispense with his services. He was an abnormally proud man (as all the Gaythornes were), and before he died, made good the whole deficiency out of his own pocket, thereby leaving his wife and child in somewhat straitened circumstances.

Finally, David Gaythorne, great-grandson of Thomas and son of the bank manager, a bright-eyed school-boy of some sixteen years of age, who was seated with his friend, Robert O'Shee, first mate of the steamship Airlie, on the hatch of the after well-deck, upon a certain sunny afternoon in August.

The ship lay at anchor in Plymouth Sound, biding her time to sail; and the soft breeze, that sent the little pleasure yachts skimming out to sea, washed the water monotonously against her bows and, from time to time, stirred the drooping ensign on the poop.

The boy played uneasily with a rope end, keeping his eyes lowered upon the deck. He seemed strangely serious for one of his years, and in none of the best of moods.

"I want you to do me a favour," he said at last.

"'Tis as good as done," said the mate, with a slight Irish brogue.

"I'm not so sure about that," answered the boy. "Wait till you've heard."

"Faith, then, 'tis a difficult task you'd be after setting me, Davy."

"No, it's not. I only want you to say to some one else what you have, time and again, said to me."

"Bedad, you're serious enough about it. Ye don't happen to want it in writing, by the way?"

"No, I don't," was the sharp reply.

"Then let's hear what it is at all, before I'm tired of listening."

The boy hesitated for a moment; and then began:

"You have often told me stories of sea life," he said.

"I have."

"Well," continued the boy, raising his eyebrows inquiringly, "I suppose you would never have done that if you were not—in a way—fond of the sea?"

"Wait a bit now! Would I say that?"

"I've always taken it for granted."

"You see, Davy, me boy," said the mate, "the sea and mesilf are old acquaintances; and 'familiarity breeds contempt,' as Shakespeare said, or was it his fraternal inimy, Francis Bacon?"

Davy could not help smiling.

"Then I am to take it you have an absolute contempt for the sea," he said ironically.

"Not at all, faith! There are very few prettier things than a sunny day up the Mediterranean, homeward bound. But bedad, Davy, 'tis not always homeward bound that we are, to be sure. The sea can be dangerous at times."

"For instance?" asked the boy.

"Coming under the lee of Socotra, say, full in the face of a south-west monsoon, on an ink-black night, with never a light to guide ye."

"Oh, so you fear a storm," said Davy, assuming a sneer.

The mate regarded his young companion with a puzzled look.

"Faith, you're in an ugly mood, Davy," said he. "What is it you're after?"

"I should have thought there was a kind of satisfaction in steering a ship safely through a difficult passage," the boy went on, ignoring his friend's question.

"There ye've hit it!" cried the mate, bringing his huge palm down upon his knee. "Ye've hit it! 'Tis the pride of it!"

The boy smiled. With all the diplomacy of his great-grandfather he had turned the conversation into the very channel he required. And this was no difficult matter with O'Shee. The mate was a sailor, and, as will subsequently be proved, he had a good deal of the hero in him; but, above all else, he was an Irishman, readily impressionable, and in many ways more of a boy than his young companion, in spite of the fact that O'Shee stood six foot six in his bare feet and had the frame of a Hercules.

"Then, at least, there's satisfaction in a sailor's life?" prompted Davy.

"Never a doubt of it!" cried the mate.

The boy's demeanour suddenly changed.

"Then why, I should like to know," he demanded, "have you told my mother different?"

O'Shee was thunderstruck: he saw trouble ahead.

"I've only told her what she wanted to know," he explained.

"And what was that?" asked the boy, taking him up sharply.

The mate tried hard to collect his thoughts.

"She asked me once if the food was good on sailing-ships," he stammered.

"And what did you say?"

"I told her the truth, faith: that pickled pork and ship's biscuits, that would break the tooth of a tiger, weren't the height of delicacies."

"Yes," said Davy sourly. "And what else did you say?"

"She asked me if the work was hard, and I said it was, when a ship called at many ports and the days had to be spent on cargo duty and the nights on watch—which don't permit of overmuch sleep and barely time to snatch a meal in between whiles."

"Great Scott!" exclaimed the boy. "And you told her all this! I wish to goodness I had never taken you to see her."

And so had O'Shee at the time. For Davy, with an immense pride, had dragged his gigantic friend before his mother, a very unwilling guest and painfully shy. But, in an incredibly short time the good lady had put O'Shee at his ease, with a view to questioning him later on upon the sailor's life that her son seemed so anxious to lead.

The above conversation was the result, which came to O'Shee something in the nature of a blow. For he remembered very well that he had said much in his fanciful stories of sea-life to fire the imagination of the boy; while, at the same time, he had shown the mother a very different aspect of the same question. He feared the worst, and saw at once that he himself was alone to blame.

"Davy, what have I done wrong?" he asked meekly.

"Done!" cried Davy, who had worked himself into a white heat. "Why, you have shut me up in a lawyer's office for the rest of my life. How would you like to sit on a high stool in a stuffy room, with a pen behind your ear scribbling?"

Something very like a sob escaped the boy's lips. The mate heard it, and looked guiltily repentant.

"I wouldn't like it at all at all," he owned. "At any rate, that's what you have done for me.

"Let's put our heads together and see what can be done."

"What can be undone, you mean," cleverly suggested Davy.

"I can't tell her what isn't true," said the mate.

"I don't want you to. Only you know well enough a sailor's life isn't all pickled pork, ship's biscuits and cargo duty," said Davy, in disgust. "What about the foreign countries you have told me about, and the whales and icebergs and sharks and water-spouts and—"

"Be quiet, for the love of Hiven!" cried O'Shee. For now indeed did he see what a rupture he had unconsciously brought about between the mother and son.

He questioned Davy, and finding there had been one or two scenes of a semi-dramatic character, which reflected none too highly to the credit of Master Davy, was more than anxious to put matters right if he could.

At that moment, in his warm Irish heart, he deeply sympathized with the boy, whose hopes and aspirations he fully believed he had scattered to the winds; and he rashly promised to give Mrs. Gaythorne a very different account of all that he had previously said.

The admission had no sooner left his lips than nothing would satisfy Davy than that, then and there, they should both go up to the house. O'Shee tried to procrastinate; but it was of no use. Davy had him ready primed, with glowing stories of a life on the ocean wave, and minute instructions as to how to act towards his mother, and he would by no means consent to be put off for even an hour.

They accordingly rowed ashore, and found Mrs. Gaythorne seated behind her tea-tray.

O'Shee's determination left him the very moment he entered the room. Perhaps the good fellow's conscience smote him unexpectedly; for to recommend the merchant service to a spirited school-boy, with an inveterate love of adventure, and to a lonely widowed mother, as an occupation for her son, seemed now two very different things. O'Shee appeared painfully self-conscious and shifted uneasily in his chair.

Davy waited in patience; but never a word passed the mate's lips.

The silence became prolonged; and O'Shee, feeling it incumbent upon him to say something, racked his brains in vain.

Suddenly, he opened out brilliantly, like a multi-coloured star-rocket in a darkened sky.

"Have ye ever killed a monkey, Madam?" he asked.

Mrs. Gaythorne confessed that she had not.

"Then allow me to congratulate ye. 'Tis the next thing to homicide—they die so human-like."

Whereupon he upset his tea-cup, and began blushing prodigiously, blush following blush on the weather-beaten face like the guns of a royal salute.

The tea came to an end; yet the mate said nothing more, and finally rose to go.

"Go on!" said Davy, in a stage whisper, nudging him violently in his great ribs. But he might as well have bombarded a Spithead fort with a pea-shooter, for all the effect it had upon O'Shee.

"Go on," he said again, with desperation.

"Go on at what?" cried the mate almost fiercely.

"Tell my mother what you think of life in the merchant service," prompted Davy, as it were, displaying his guns.

O'Shee's face lit up, after the manner of a man who has suddenly guessed a riddle. He lost his self-consciousness, and broke into a broad and beaming smile.

"Faith, Madam," said he. "'Tis the life of a dog!"

Whereby he shattered Davy's chances for ever, and merely endorsed all that he had previously told the mother.

Davy followed him out into the little garden, shaking with anger and on the verge of tears.

"You promised! Oh, you promised!" he cried.

"I know I did," said the mate. "I promised for your sake, Davy."

"And you broke it!"

"Aye, I broke it for hers."

Which was exactly O'Shee all over.

Of Uncle Joe The Pirate

AT first, Davy was highly offended with his old friend, who, he imagined, had grossly betrayed him. But he turned the matter over in his mind in the silence of the night, and came to the conclusion that after all O'Shee was right and had but reminded him, in his own artless way, that he had acted somewhat selfishly throughout.

Accordingly, being anxious to make it up, and filled with an inordinate desire to bathe from the ship's side, he went down to the Airlie, two days later, and found no one but Ah Four, the Cantonese cook, on deck.

"Where's Mr. O'Shee?" he asked.

"Gone bottom-side," answered the Chinese, meaning that O'Shee had gone below.

Davy went to the head of the after-companion, beneath which the mate's cabin was situated.

"Are you there?" he asked timidly.

"I am, bedad," cried the mate, appearing from the alley-way in his shirt-sleeves.

The man was indeed a giant. As he stood on the lower deck, his head was on a level with the top-step of the companion-way. In addition to his great height, he was more than proportionately broad, though his shoulders sloped at a steep angle—a sure sign of concentrated strength. The muscles stood out on his great forearms like plaited rope. The extraordinary length of his arms was particularly noticeable; they hung down to his knees, like a gorilla's, and were terminated by a pair of enormous fists.

The two recreations of this man were butterfly-collecting and the composition of humorous songs, which bore a marked resemblance to each other. He took an especial pride in his verses; and by the simple process of repeating the same line several times, he was able to produce typewritten songs of prodigious length in testimony of his genius. On moths and butterflies he was more or less an authority. He had started his collection when he first went to sea as a boy, and had conscientiously continued it in his manhood. There was something incongruous in the great arm that could have felled an ox, wielding a butterfly-net with all the unmingled pleasure of a child.

O'Shee had never been known to hit a man in anger. Like most strong men he was particularly sparing of his strength. And well for him that such was the case, for most assuredly, had he ever struck at a man, he would have stood in the dock for manslaughter.

There was one story in particular, illustrative of his prowess, which spread like wildfire in the ports, and made men ceremoniously polite to the first mate of the Airlie. Once, when the swollen current of a China river had loosed a coasting vessel from its moorings, O'Shee had uprooted the mooring-post upon the "bund," that had taken nine coolies half a day to plant. His action saved the ship; for there had been no time to untie, and the drifting vessel was bearing straight upon the Airlie, stern foremost, with her engines stopped. He had handled the post as a man moves a peg in a cribbage scoring-board; and after that, no man dared argue long with O'Shee, except McQuown, the captain, who stood five feet two and was rude to every one on principle.

"Afternoon, Davy," said the mate, smiling. "I thought I'd see ye again before long."

"I've come to apologize," said Davy. O'Shee's smile grew wider.

"And what is me darling of a boy after apologizing about?" he asked.

"I did wrong to ask you to take my part against my mother," said the boy.

O'Shee became radiant with pride and delight at Davy's frankness.

"What have I always said?" he cried. "There's not another boy like ye between Kinsale and Kobe!"

"Oh, rot!" said Davy. "But I was awfully rude to you. I wonder you didn't give me a licking on the spot."

"Why, to be sure, to save mesilf the trouble of picking up the remains."

Davy laughed heartily; and the two were once again the best of friends.

"I say," said Davy, "can I come and bathe from the ship to-morrow afternoon?"

"McQuown's not onboard at present, and I hardly like to give you permission on me own," said the mate. "You see, the little man is particularly fond of jumping down me throat, like a wasp into a mug of beer. Bedad, I'll shut me teeth on him one of these days!"

"Yes," said Davy. "He doesn't seem a very polite man."

"Man, did ye call him!" cried the mate. "Faith, 'tis an insect he is: I could put him in me watch-pocket, and never so much as know I'd got him aboard."

"You've sailed together long enough; you ought to understand one another by now."

"Bedad, we do. I see him in the mornings: 'Good-morning, sorr,' say I, with no shadow of doubt about the 'Sorr' part of it. 'Morning,' says he, though frequently he don't even say that much. And that is the whole of our conversation for the day."

"Interesting!" said Davy.

"Aye; and a bit monotonous when you're sailing to the China Seas on a tramp at nine knots a day."

O'Shee, who was one of the easiest men in the world to get along with, was singularly unfortunate in his captain. McQuown was a man who made a friend of no one; and no one made a friend of him. He was small in stature; and had a mind to match: his sole desire in life seemed to be to display his authority on every possible pretext. He had a large hooked nose and a heavy moustache which completely hid his mouth; his eyes were a pale watery blue, due to solitary drinking, which probably also accounted for the misanthropic view he took of life. The mate hated him.

"Come," said O'Shee to Davy, "I'll give ye a song, to get the thought of the little vermin out of me head."

He went into his cabin, and brought out an accordion, somewhat meretriciously adorned with painted flowers.

Seating himself on the companion, he drew out a few chords by way of tuning up. At the same time his expression became that of a man who is suffering the most intense physical pain.

"What shall it be?" he asked.

"Anything you like," replied the boy.

O'Shee considered a while, and then, in a perfect hurricane of a voice, that had neither tone nor training nor anything else to recommend it, burst suddenly into the following refrain, seeming to rely for effect upon a most colossal lung-power and the broadest Irish brogue:—

"Me Uncle Joe, the Poirate, wanst jined a fishing rout.

They all forgot their fishin' rods; but Uncle brought the

stout.

Me Uncle brought the stout, me bhoys, and passed it freely

round;

Ontil they all wint sound aslape and ran the boat aground.

They grounded on an oisland, near the Hade av Ould

Kinsale,

And woke again in China. Faith, the oisland was a whale!

The oisland was a whale, me bhoys, that wint to Far

Cathay,

Around the Horn and north again, a thousand moiles a day.

They faisted on the blubber, and the oil they had to

drink:

They got so fat and heavy that the whale began to sink"...

"Bedad, it's a Camberwell Beauty!" cried the mate, instantly breaking off in his song and throwing the accordion aside. He seized Davy's cap from his head; and dashed down the deck after a gaily-coloured butterfly that fluttered among the derricks.

"Faith, 'tis as delicate as it's rare!" cried O'Shee. "Kape still, for the love av Hiven, whoile I catch ye now!"

His Irish accent became more pronounced in his excitement, as he danced about in pursuit of the insect.

At last, the butterfly settled under the poop, and Davy's cap immediately closed over it.

"Thanks be to the Saints," gasped O'Shee. "Davy, into me cabin, me bhoy! You'll see a white bottle on the table, against the tobacco-jar, which is on the bed."

In spite of this lucid explanation of its whereabouts, Davy managed to find the bottle, and watched O'Shee slip the butterfly into it, with the fingers of an expert. Then he followed O'Shee into his cabin, where the mate pulled out one of the glass-topped drawers of a cabinet, containing many thousands of butterflies and moths from every part of the globe. O'Shee pinned down the newly-captured Camberwell Beauty, spreading its wings with little minute pins so deftly, that Davy wondered how the great thick fingers could manage such delicate work.

"Faith, 'tis a daisy!" said O'Shee, looking at the butterfly in admiration before he replaced the drawer.

"It is indeed," said Davy.

"There's another here," said O'Shee, "but 'tis an inferior specimen. They are all British butterflies in this case. I keep 'em grouped according to what the books call the 'habitat' of the bastes. I've been over twenty years at it," he went on. "And, bedad, I take as much pleasure in it as a bride in her trousseau, if the truth be told."

Davy could not help smiling. If O'Shee had collected tigers, instead of tiger-moths, it would have seemed so much more appropriate.

"Now will you finish the song?" he asked.

"No. The captain has just come aboard; and he don't approve of secular music," added O'Shee, with a wink. "I'd best row ye ashore."

They went on deck again, and met McQuown at the head of the gangway.

He regarded Davy with a glance of unfeigned disapproval.

"My young friend would like permission to bathe from the ship's side," said O'Shee.

"Why?" asked the captain abruptly.

"For the novelty of it," said the mate.

"He wishes to turn my ship into a bathing-machine for the sake of a novelty," said McQuown.

"With your permission," answered O'Shee.

"Let him do what he likes," said the captain testily; and he passed down the deck.

O'Shee smiled, and took his young friend affectionately by the arm. The sun had sunk nearly to the level of the sea. They stood upon the main deck, looking out across the water; and side by side, a strange pair they made. Suddenly O'Shee turned towards the boy.

"I hope your lady mother is well?" he asked.

"Perfectly," answered Davy.

"Bedad, I am glad to hear it. Will you give her my best respects? As for the song, I'll finish it another day. There are nineteen verses in all."

He held Davy firmly by the lapel of his coat.

"'Tis me own composition," said he. "And I'm proud of it. Faith, 'twould do credit to Sir Gilbert O'Sullivan himself!"

The Mark

DAVY had another friend on board the Airlie; and this was old Daniel Mason, the so-called ship's carpenter, and the only European member of the crew, who were for the most part Lascars from the Malabar coast.

In reality, old Daniel combined the duties of quartermaster, assistant-boatswain, master-at-arms, sailmaker, and handy man-of-all-work; but he was called "the carpenter" for short.

He was an eccentric old gentleman, and was supposed by the ship's officers to be entirely mad. He had never been known to go ashore. When the vessel was in port, it was his custom to sit all day, sailmaking, in the darkness of the forecastle; he never came on deck except when duty called him. O'Shee had often rated him on the point.

"Dan," said the mate one day, "you ought to be on deck more, and get the air."

"Beg pardon, no, sir," replied the old man. "I don't go on deck unless you orders me."

"Why not?" asked the mate.

Dan laid down the sail at which he had been stitching, and answered slowly, as a man who quotes from memory:

"Because," said he, "when I goes on deck, I sees the shore; an' when I sees the shore, I wants to go ashore."

"Well, why don't you?" exclaimed the mate. "You can always get leave; but you never ask for it."

"I'll never go ashore no more," said Dan persistently.

"Because why?" roared the mate, getting to the end of his patience.

"For two reasons, sir. Fustly, because there's more whisky ashore than there is aboard; and, lastly, because there's only two kinds o' men: them that's tempted and them that ain't."

Such philosophy was too much for O'Shee; and after that, old Dan was allowed to pursue his solitary sailmaking in peace. In fact, all he cared for was tobacco, which he used to chew in great quantities, and an old Martini rifle, that he had got from a West Coast native in exchange for two ducks. This he kept regularly oiled. He used to take the greatest delight in threatening the Lascar sailors with it. If they were too long over any given piece of work and Dan was in charge, he would hasten off to the forecastle and get the rifle, levelling it, unloaded, point blank at their heads. This invariably had the desired effect, and the frightened seamen, who were never quite sure whether Dan was serious or not, worked as if for dear life until the job was done and the old man had taken the weapon back to its rack in the forecastle.

It was an open secret that old Dan was quite well-to-do. But he was by no means the orthodox hoarder of gold; he had become rich not through any special love of saving money, but simply and solely because he had no use for it. Since he had neither wife nor family, nor any needs (beyond the very cheapest tobacco), and made a principle of never going ashore, he had no chance of spending his pay, but allowed it to accumulate in a tin box, which he had handed over to O'Shee for safe keeping.

One day O'Shee came to Dan, as usual, in the forecastle.

"Dan," said he, "the bank's full."

"Then, Mister O'Shee, the next time you go ashore would you be so kind as to buy me another one?"

The mate good-naturedly did as he was asked; and in course of time the second box became filled, and was superseded by a third.

The fact that the carpenter was such a rich man gave him additional interest in Davy's eyes from the very first. But, in time, he came to like the old man for his own sake; and Dan no less readily took to the boy, and on more than one occasion disproved himself a miser by breaking into the tin box and buying sundry small presents for Davy from the native merchants who came on board in foreign ports.

Davy came on board the day after he had made it up with O'Shee, his towels and bathing-dress wrapped around his neck.

He found O'Shee and Dan upon the deck, deliberating on a question of repairs to an awning.

"Bedad, you're not likely to go home wet at all," said the mate.

"I brought my own towels as I knew you don't use them, and I thought you might not have any on board," retorted Davy, darting immediately out of reach of the mate.

"Did ye now," said O'Shee. "Come, I want to whisper something in your ear."

Suddenly, the mate shot out an arm, and seized the boy in his grasp. "Shall I pull your head off or break ye in two?" he cried.

Davy struggled in vain to be free. O'Shee held him over the bulwarks with one hand. "If I drop ye in you can dry your clothes in the ingine-room and go home in the towels."

Davy was finally deposited in a sitting position on the deck.

"Come and have a swim," he said, when he had sufficiently recovered himself to speak.

"No," replied the mate.

"Why not?" asked Davy. "It's a beautiful day."

"And I'll not jump into the water, when I can't swim, because it's a beautiful day," answered the mate.

"Can't swim!" exclaimed Davy. "I never heard of a sailor who couldn't swim before. Why, supposing the ship sank."

"Faith, I'd just row ashore," said O'Shee.

"But supposing it sank in a storm at sea?"

"And if it was mid-Atlantic, would you personally swim to Sandy-Hook or Kinsale Harbour?"

This argument was unanswerable; and Davy laughed it off.

"Where can I undress?" he asked.

"In my cabin," said the mate. "'Twould be more decent than the main-deck, I'm thinking."

Davy went below; and a few minutes afterwards a splash aft announced that he was in the water. He swam round to the gangway steps, and there imitated the diving boys of Colombo and Aden, of whom he had often heard from O'Shee.

"Hab-a-dive! Hab-a-dive, sir! Hab-a-dive!" he cried ceaselessly.

O'Shee threw pennies into the water; and Davy secured them as invariably as his little black rivals in the East, tucking them away in the corners of his mouth and repeating his monotonous call.

They had spent some time thus, when they were joined by a fourth party, Ah Four, the Chinese cook, who came on deck to watch the fun, polishing a copper kettle.

Ah Four was a little man, with a bad cast in his eye, which gave him a particularly foxy appearance. Like most Cantonese of the "boy" class, he was exceedingly tidy in his dress: his long white coat was scrupulously clean, and the fore-part of his head was shaven close. He stood regarding the swimmer with a countenance utterly devoid of any sort of expression.

Davy, who had been long enough in the water, ran up the gangway steps, and stood dripping on the deck.

"Dan, we'll have to swab the main-deck at sunset to-day," said O'Shee. "Master Davy—"

His sentence was cut short by a loud exclamation from Ah Four.

They all turned suddenly on the cook. But Ah Four's face was again expressionless, and he was still energetically polishing the kettle.

"The heathen's dimented," said the mate, going for'rard; while Davy went aft to change.

But, had there been any one on deck at the time who understood the Cantonese dialect, he would have interpreted Ah Four's exclamation in the following words:

"The Mark! The Mark!"

How Ah Four Recognized The Seal

ON the following day the Airlie moved into dock, in order to take on the remainder of her cargo; but although Davy continued to go down to the ship daily, he had little chance of another talk with O'Shee. The mate was kept almost continuously at work, bellowing his orders above the noise of the derricks and the rattle of the donkey engine and pacing up and down like a caged lion at feeding-time.

When the cargo was all shipped, Davy thought that at last O'Shee would be free, and he appeared on the wharf in full expectation of hearing the remainder of the fortunes of "Uncle Joe the Pirate." However, he found the owner and his wife, accompanied by McQuown and the mate, making an official inspection of their property. They were an imposing couple, and could have been identified as the owners at the extreme range of a lunar telescope. Their name was Higgins. He was over-fed, and she was over-dressed; and they both apparently suffered from over-estimation of their own importance. Moreover, Mrs. Higgins's curiosity seemed insatiable; she positively deluged the captain with Hows and Whys and Wherefores, until McQuown (to whom politeness never came by nature) became abrupt and openly rude. But had he been even more so, the good lady would never have noticed it; for she shot questions at him as suddenly and rapidly as the explosions of a Chinese cracker, neither waiting for an answer nor seeming to require one.

Davy's patience became finally exhausted; and he turned towards home in none of the best of tempers. He was anxious to see as much of his friend as possible, for the ship was timed to sail in three days. It would be nearly six months before the Airlie would be back in Plymouth Sound, and at Davy's age, six months was a monstrous time.

As he passed through the town, they were lighting the street lamps, and knowing thereby that he was late, he was hurrying on his way, when, suddenly, at a corner, he came upon Ah Four, the Chinese cook.

He had had no previous intercourse with the Chinese—though he knew him well enough by sight—and was for passing on with a friendly nod of recognition, when, greatly to his surprise, the cook stepped sharply before him.

"Good-evening," said he, in tolerable English, though clipping his words short, as his nation are wont to do.

"Good-evening," replied Davy.

"I very much like talk with you," said Ah Four. (He pronounced it "velly.")

"Indeed?" said Davy. "Then we had better talk as we walk along."

But Ah Four showed no sign of moving.

"Talk walk all same time no can do," he said.

"Why not?" asked the boy.

"Because this belong number one pidjin."

Davy laughed. He had heard O'Shee talk "pidjin English" to the cook, and was minded to try his hand at it.

"What for you wantchee talk number one pidjin?" he asked.

"All come proper time," answered Ah Four. "You first please answer three questions."

The Chinese drew close to him, and squinted up into the boy's face, his little almond eyes twinkling with expectation.

"Your name?" he whispered.

"Gaythorne," answered Davy. "David Gaythorne."

"Your paternal grandfather's name, Thomas?"

"My great-grandfather's was. But how did you know that?"

"I know plenty more. That same man die China side."

"Yes," said Davy, now fully mystified.

"You have mark here," said the cook, touching Davy on the back of his left shoulder.

Davy nodded.

"Your father have all same mark?"

Ah Four's knowledge of the English language did not admit of the correct construction of an interrogative sentence; but he was able to convey the idea of a question both in the intonation of his voice and by wrinkling up his forehead until his eyebrows nearly disappeared in the blue shaven fore-part of his head.

"I believe all my father's family have always had that mark," answered Davy.

"Your great-grandfather all same," asserted Ah Four.

"I suppose he had," said Davy.

"I say so," said the cook. "I know."

Davy eyed him in astonishment. The cook was evidently perfectly serious; except for the little cross-eyes, that danced with animation, Ah Four's face was as of stone. The cruel, thin lips, stained brown by the opium habit, were firmly closed, and the corners of the mouth drooped slightly, with an expression far from humorous.

There was something in his self-confident air which annoyed Davy. The boy remained silent for some time, regarding this human enigma with a puzzled look, and then burst out suddenly, almost in anger:

"Look here," said he. "How do you know all these things?"

Ah Four glanced furtively up and down the street, and then, catching the boy's arm, drew him suddenly towards him, bringing his mouth close to Davy's ear.

"I belong Member Secret Society of Guatama's Eye," he whispered.

"What's that?" said Davy, more perplexed than ever.

"I talk you presently. You hear all—all! Then you belong rich man."

It was now quite dark. The street in which they stood was deserted. The light from an adjacent lamp fell full upon the face of the Chinese cook. It was not a face just then that one was likely to forget; above all, it was not a face to trust. Davy knew it, yet the mystery in the thing tempted him to see it to the end.

"What is this secret?" he asked.

"You," replied the cook.

"I! I—am a secret!"

"You, if you have the Agreement."

"What Agreement?"

Ah Four for the first time became almost excited. He turned suddenly on the boy.

"You no have got Chinese paper?" he cried in alarm. "Paper all over Chinese writing?"

He said "liting," but that was immaterial; his voice shook while he said it.

"No," answered the boy.

"Think!" cried Ah Four impatiently. "Paper with large red seal. You no have got things belong Thomas Gaythorne?"

Davy was beginning to think the cook mad.

"You have got picture Thomas Gaythorne's wife?" continued Ah Four, raising his eyebrows again, with undoubted anxiety in his look.

"Yes," said Davy. "We've got that."

"Ah," exclaimed Ah Four, with a sigh of relief. "Then the paper come safe to England too. You must have seen!"

Then Davy suddenly remembered that once, when searching the lumber-room at the top of the house, he had found a long scroll of paper covered with Chinese characters in an old box, that was smothered in dust and smashed beyond repair. Ah Four instantly saw the look of recollection that lit up the boy's face.

"You have got!" he cried excitedly. "Where?"

"I threw it back into the box—as far as I remember," said Davy.

The cook seized his arm, and by main force dragged him rapidly up the street towards his home.

"Come," said he. "Come."

Davy had no alternative; and in a few minutes they had reached the house. A lamp was visible through the curtains of the front room, where his mother had doubtless awaited his return for some hours.

Davy had intended to go straight up-stairs to the box-room, where he knew the paper to be. But his mother's ears had long been intent upon his coming.

"Is that you, Davy?" she called.

"Yes, mother," answered the boy, half reluctantly appearing at the door.

"Come!" she said. "Your supper has been waiting a long time."

"I can't, mother," answered Davy. "I must go out again."

The whole manner of the Chinese cook had from the first filled him with curiosity, and then with a determination to see the matter through.

Mrs. Gaythorne looked up in surprise.

"Go out again!" she repeated.

"Yes, I must," said Davy earnestly.

"Where?"

"Mother, don't ask me! I don't know myself, as a matter of fact. I'll be back as soon as I possibly can. I promise you that."

Since Mrs. Gaythorne had opposed Davy's will more than she usually cared to do in the matter of his going away to sea, she regarded a concession on several other occasions as more or less incumbent upon herself.

"Well, if you must, you must, I suppose," she said. "Only whatever you want out of doors this time of night I am sure I can't think."

But before she had finished the sentence Davy had closed the door, and was gone. One glance assured him that Ah Four was still in the street; and then, taking a candle from the hall table, he ran hurriedly up the stairs.

The door of the lumber-room was unlocked; he entered and placed the candle on a box. The dust lay thick on everything, and a great cobweb was stretched across the door; for the Gaythornes' travelling days were done, and the room was seldom visited. He remembered exactly where the paper was, and throwing aside an armful of old tattered uniforms (that had once belonged to his grandfather—the Crimean hero) he dived among the lumber. In a few seconds he came upon the broken box, and throwing it open found the scroll, where he had carelessly thrown it many months before.

A moment afterwards he had rejoined Ah Four in the street.

The cook snatched it from his hand, rolled it open, and pointing to the red stamp at the bottom, cried: "The seal! The Great Seal of the Lake Monastery! Ah! Master! Master! you belong rich man for evermore!"

Davy stared at him in amazement. They were quite alone, for the street was all but deserted. A sea-mist had fallen across the town, and the lamp-lights were all but hidden in the haze. A solitary pedestrian, who had passed down the road, had been visible only as a shadow, though his hurrying footsteps had sounded sharp and clear on the asphalt pavement until they died away in the distance.

All this—the blurred lamps, the damp mist and the lonely passenger—was so thoroughly in keeping with the general aspect of the boy's daily life that he found it hard to reconcile with tales of secret societies, Lake Monasteries and hidden treasure.

Yet Davy was of a breed to whom adventure came naturally enough. When he had recovered from his first surprise, he calmly turned the question over in his mind. Clearly, even if the whole story was a fable, Ah Four at least believed it; he could see no reason why the cook should deceive him.

"You must tell me all from the beginning," he said.

"Not here," replied the cook. "Street talk no good. Come this way, I know good place."

Accordingly the two set off, Ah Four leading the way to a poorer part of the town, which consisted for the most part of public houses and sailors' lodgings, and was frequented solely by seafaring men. After turning down many little alleys and by-ways, none too respectable and none too clean, he turned in at the door of a small inn, above which was suspended the following advice: "Live and Let Live."

The Chinese entered as one who knew the place; and passing the small public bar, where a group of drunken men-of-war's men were quarrelling among themselves, he went straight to a little dark back-parlour, ordered a packet of cigarettes and some port wine for himself, and a ginger-beer for Davy, and then securely locked the door.

There they remained for close upon an hour, and when they came out again the boy's face was flushed with excitement. Moreover, there seemed to be nothing more to be said, for they immediately separated without a word, each hurrying on his way.

Like A Thief In The Night

FOR the next three days Davy gave the Airlie a wide berth. O'Shee wondered at the boy's absence, but had no time to go ashore and inquire for him. As the time of sailing drew nearer the mate grew more anxious, consoling himself however with the thought that had anything happened to Davy he most certainly would have heard. He therefore expected his young friend almost every hour; and as he went about his work on deck, his eye was frequently cast toward the shore.

Yet Davy never came. Once he did actually set off for the ship; but, half-way there, his heart failed him, and he turned back. Something evidently lay heavily upon the boy's mind. His mother had noticed it from the first; and though she had thought it best to hold her peace, she watched intently every action of her son.

On the third night after his interview with Ah Four, Davy sat by the fireside, an opened book upon his knee, and throughout the space of half-an-hour he had never so much as turned a page. His chin rested on his hand, and he sat silent, gazing into the fire. His mother's eyes had been upon him for some time.

"What are you thinking about, Davy?" she asked.

The boy looked up, as vacantly as one awakened from sleep.

"I was thinking of many things," he answered. And then, in an altered voice: "Mother, do you know anything of Thomas Gaythorne?"

"Very little, Davy," she answered, surprised at the question. "He was a very extraordinary man in many ways, I believe. He ran away from his wife before they had been married two years. So he could not have been a good man."

"Perhaps," said Davy, "he ran away that he might come back a richer man."

"I don't think so, Davy. You see, he had spent all his life roaming about the world; and he owned, in a letter he wrote his wife, he only left her because he found he could not resist the temptation of going back to his old adventurous life."

"I expect," said Davy vaguely, "it was in his blood. But, tell me, didn't he say he was going in search of something?"

"I don't think so. And anyhow he should have told his wife first."

"Perhaps he knew that she would never have let him go," said Davy.

"Perhaps so. And it would have been better for him had he stayed at home; for he only lost his life and gained nothing."

"Yes. And gained nothing," slowly repeated the boy, in a tone so serious and unusual that his mother regarded him in bewilderment.

She hardly recognized her son. She afterwards associated his behaviour on this occasion with the evening upon which he had left his meal untouched and gone out again to the street. But she was quite unable to explain it all. She trusted implicitly in her son; and, for once, Davy offered her no confidence.

They rose to go to bed, and went up the stairs together, with hardly another word. As was her custom, she accompanied him to his bedroom, and kissed him fondly in wishing him good night. In undemonstrative boyhood a mother's kisses count for little or nothing. It is in after years that a man remembers them, like jewels he once owned and lost.

Davy was no exception to the general rule. The affection was all there, deep enough; but, by the false idea of manliness conceived by the average English boy, he deemed affection a manly thing to hide. He seldom returned his mother's kisses with any warmth, and sometimes never at all. But, on this night, of his own accord, he placed his arm around her, and held her tenderly and strongly, as if for all the world he had but then and there sprung suddenly into manhood, and it was she who had to place her trust in him. He was already taller than she; and he bent down and kissed her fondly, again and again, as he had never done before. For her part, as she hurried from the loom, her woman's instinct warned her of danger ahead; and tears, half of fear and half of love, sprang unbidden to her eyes.

It was long before she slept. Far into the night fearful imaginings held her wide awake. She grew feverish with her thoughts; and, as often as she shook them off, she heard Davy moving in his room, which brought him back again to her mind. She pictured him in one danger after another. Sometimes he was confronted by a peril that she herself was powerless to prevent; at others, she flung herself in his way, snatching him up in her arms as though he were still a child, and rushing with him out of the way of harm. At last, weariness overcame her, and she sank into a slumber, in which her former thoughts became but dreams, with Davy always in their midst.

As for Davy himself, he had noticed the tears in his mother's eyes as she left his room. He stood for a moment irresolute; then he went to the window, and, flinging it open, leaned out and looked into the night. He remained thus for some time; and then, opening a drawer of his dressing-table, he took out the Chinese Agreement that he had shown the cook. He studied it for some minutes; and though he could have had no notion of the meaning of the strange, fantastic characters, this seemed to hold him to his purpose. For he rolled it up, put it into his pocket with a determined air, and forthwith, sitting down at a little table, began to write. It was a letter to his mother. His lips were tightly pressed; but, nevertheless, big tears dropped, one by one, from his eyelashes as the pen scratched blindly on.

The letter written, he packed a Gladstone bag with such things as he thought that he might have need of. And this done, he took out his money, and counted it: he had precisely two shillings and twopence. He smiled, though his tears were hardly dry—and then blew out the light.