RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Charles Gilson (1878-1943)

Dust Jacket of "The City of the Sorceror,"

Hutchinson & Co., London, ca. 1924

Cover of "The City of the Sorceror,"

Hutchinson & Co., London, ca. 1924

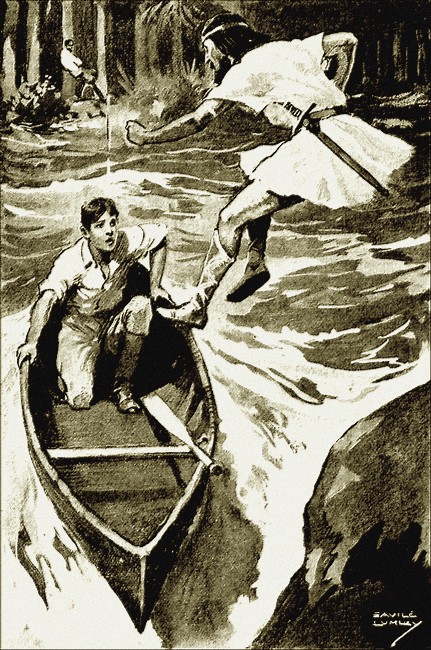

Frontispiece.

He landed lightly in the canoe.

JOHN FOUNTAIN, seated in the bows of the canoe, tapped the bowl of his pipe against the gunwale. The red-hot ashes sizzled in the water.

"A pipe won't draw in a climate like this, he observed. "Wet as a vapour bath!"

"And hot as an oven," threw in the boy seated in the stern.

Fountain was silent a moment, his eyes glancing quickly from one bank of the river to the other, the fingers of his right hand gripping the small-of-the-butt of his rifle.

"I've had twenty years or more," said he, "of this flaming, fever-stricken continent; and I reckon I know Africa better than any man who ever lived—with one possible exception."

"Who's that?" asked the other.

"Henry Tremayne," said Fountain. "Never heard of him, Neil? Because you're young. Tremayne came here in the early days, when no white man had ever crossed the Zambesi, before the Great Lakes had been discovered, and the head waters of the Congo were believed to be the Nile. He was a wonderful man, in his way, was Tremayne. He had a positive genius for learning Kaffir languages; he knew as much about witchcraft as a Niam-Niam witchdoctor, and he understood the art of making friends with such as cannibals and pygmies. He made one expedition after another into the heart of the interior; and time and again he came back to civilization with never a scratch, and maps that he had made and specimens of metals, plants and such like. He was fever-proof, too. Once or twice we travelled together, and I never knew him to be sick for a day."

"Now you speak of him," said Neil Ranson, "I remember my father telling me about him. Tremayne was in Mashonaland when we were up there, buying cattle. But that was about seven years ago, when I was a boy of ten."

"He was a genius," said Fountain, as if to himself. "That's what he was. Tremayne looked like a sort of viking. He was well over six feet four in height, and broad in proportion, with a great sandy beard that covered his chest. And yet, though he was a Hercules to look at, all his interests in life were scientific. He was a naturalist and botanist, a geographer and scholar. Different kind of man to me. I've never been anything but a big game hunter."

"And what happened to him?" asked Neil.

Fountain shrugged his shoulders.

"I was going to tell you that," said he. "You know the saying, a pitcher may be taken to the well too often. Tremayne was last seen on the Kasai. He's believed to have gone alone into the Great Forest, where a man may be starved to death or flayed alive. That was three years ago, if I remember right, and nothing has been heard of him since."

Young though he was, Neil Ranson was already inured to a life of hardship and adventure. As quite a small boy, he had trekked into Mashonaland with his father, a transport rider who had made a small fortune out of cattle-trading, until the fatal rinderpest, or cattle disease, had ruined him—soon after which he had died, broken in spirit, his constitution undermined by malaria.

And John Fountain had found the boy in the wilderness, with no possessions in the world but a trek-wagon and a herd of goats. Fountain was a lonely man, a wanderer by instinct. He had grown grey and withered in the tropics. In some ways he lived the life of a primitive savage, the predatory man who lived by hunting. From the very first he had taken to the boy, though he was the last person in the world to give expression to any sentiment or emotion.

"You had better come along with me," he had said. "I'm kind of solitary; and it's a good thing to have someone to talk to at the end of the day's march when the camp-fire's alight."

And so these two had sojourned together for eighteen adventurous months, whither Fate and the current of the unknown rivers they traversed determined to take them.

The boy sat regarding thoughtfully the dark, impenetrable jungle through which the river flowed. Beneath gigantic trees, around the trunks of which innumerable creepers were interwoven, was an undergrowth so thick and tangled that it was as if they were encompassed by inaccessible and massive walls.

The river itself was broad; the current swift, swirling in eddies around islands in midstream. In the comparative cool of the evening, the canoe drifted rapidly, without the help of a paddle, save that which Neil used for steering.

A thick mist hung upon the surface of the water, and myriads of insects—gnats, mosquitoes and gigantic dragon- flies—droned with a sound like the constant humming of a top.

Whither they were going they knew not. It was enough for Fountain that they journeyed in comparative comfort into territory hitherto unexplored. The hunter's sharp grey eyes shot quickly from one bank to the other. He knew from experience that, at that hour of the day, he might at any moment get a shot at a buffalo or a rhino that had come down to the river to drink. John Fountain loved the wild, because danger and excitement were as necessary to him as food, because the one thing he never wanted to know was what would happen to him next.

The boy—as was natural enough—was of a more romantic turn of mind. The Great Forest, into which at that time few white men had ever ventured, where dangers were said to lurk unseen in almost every thicket, appealed to him with the fascination that must always attend the mysterious.

For weeks they had not seen a human being. They had been alone with Nature. By night, when their camp-fire burned, the silence was like that of the grave. By day, the sun beat down upon them with such fierce intensity that their great pith helmets felt like bands of red-hot iron.

Fountain was burnt as brown as a Hottentot. He was thin, too, as a rake, his skin like parchment, tight-drawn upon his cheek- bones. For the last few weeks he had allowed his short, crisp, grizzly beard to grow; whilst his clothes, like those of the boy, were in rags and tatters.

He looked like a tramp, and would have resembled a corpse had it not been for his extraordinary eyes, which glittered with life and animation. He was as sharp-sighted as a vulture, and a rifle- shot who seldom missed his mark. Quick to act, quicker still to think, he was never at a loss in a crisis.

As the sun went down beyond the tree-tops of the forest, a great black bank of cloud, irregular in outline like a mountain range, stood forth across the horizon to the north.

"Do you see that?" said Fountain, with a jerk of his thumb. "A storm's brewing. And we'll get the worst of it. There'll not be a dry rag on our backs to-night, my son."

"There's lightning, too," said Neil, who well knew the meaning of a tropic thunderstorm.

In the half light of sunset, the black clouds had opened. A huge rift had been dazzlingly illumined by a flash that was almost blinding.

"It's bearing down upon us like a tidal wave," said Fountain. "We had best find shelter if we can before it's dark."

Very carefully, as if it were something fragile and precious, he laid his rifle in the bottom of the canoe, and snatching up a paddle drove the blade into the water. The boy followed his example, with the result that almost at once they were driven downstream at the rate of almost fifteen miles an hour.

No other word was passed between them during the next few minutes, when at sunset darkness closed in upon the valley with such suddenness that great curtains might have been drawn across the sky. In a few minutes day had been converted into night.

Presently, the man spoke again.

"We're gathering pace," said he. "We're shooting down-river like an arrow. Neil, there's danger ahead!"

The last words he had almost shouted; for, even as he was speaking, the canoe had given a sudden bound forward, seeming to lift itself clear of the water like a leaping fish.

Though they could no longer see either bank of the river, they could tell by the rush of air in their nostrils and the angry swirl of the waters that they had found dangerous rapids, where, at any moment, they might be wrecked, dashed against one of the rocks or islets in mid-stream.

And at that very moment, as if the great forces of Nature were upon a sudden leagued against them, the storm came down upon them with a flash of lightning that illumined the glittering surface of the water and the giant trees of the forest, that was followed almost immediately by a deafening peal of thunder.

"Back-paddle, Neil!" Fountain shouted. "Back-paddle for your life! Sure as death, there's a cataract ahead!"

The boy, not slow to obey these orders, used all his strength and weight, whilst Fountain himself worked until the perspiration poured off him.

However, all their efforts served to do little more than to diminish the velocity at which they were travelling to destruction. The best they could hope for was to hold their own sufficiently to gain either bank; and this is what Fountain strove to accomplish, though every time he swung round the bows, the current straightened the canoe again, and sent her onward on her downward course.

By this time the thunder was even more deafening and continuous, though the lightning served a useful purpose, and, indeed, gave them presently a gleam of hope. For, by the light of a flash that endured for many seconds, Fountain made out the dark outline of an island, lying not two hundred yards in front of them, and almost on their course.

"If we can reach that, we save ourselves!" he cried, before his voice was drowned by another crash of thunder.

Neil Ranson felt already as if he had been placed upon the rack. Every muscle was strained; every joint and limb was aching. Desperation, however, lends a strength of its own. The boy had peered into the darkness; he had pictured to himself the great cataract in front of them, the black, foam-flecked rocks, the rush of tumultuous waters descending into a whirlpool where no swimmer could ever hope to live. He had imagined the canoe swept into eternity, whilst peal after peal of thunder rang the death knell of John Fountain, the little wizened hunter who for twenty years had faced savage beasts and still more savage men, pestilence and poison, who had grown grey and wrinkled in the wilderness.

It was these thoughts that gave Neil, as we have said, strength beyond his own. With clenched teeth, unconscious of exhaustion, he took advantage of each flash of lightning to keep the canoe headed for the island.

Fountain shouted at the full power of his lungs during one of those brief intervals of silence that were as intense as they were brief.

"Stick to it, my lad," he cried. "Your strength as well as mine is needed, if we're to come out of this alive!"

From out of the darkness came a shriek, long-drawn and piercing—a shriek that was terrible to hear. It was a cry of hopelessness, of unutterable dismay, of terror.

Echoed from the forest trees, carrying far upon the rushing, headlong waters of the river, sounding clear as a clarion in the silence between the thunder-claps, it was like the voice of a lost, tormented soul, crying its anguish in the midst of a dark, chaotic Underworld.

And then, yet another blinding flash made the scene as bright as day. For a few seconds it was as if the whole sky was ablaze.

"Look there!" cried Neil. "Look there! What's that?"

Fountain never answered—or if he did, his voice was drowned by the thunder. The lightning ceased quite suddenly. All was darkness again—impenetrable, inky blackness. But both had seen enough. They had seen more than they were able to explain.

A small canoe had shot past them—a flying, phantom canoe—in which they had seen distinctly the figure of a man, or else a ghost, standing upright, with arms uplifted high above his head.

Neil's brain was in a whirl. Half blinded by the lightning, half deafened by the thunder, he found himself hurled into the very vortex of a mad, raging world of terror, in which fled phantoms—a ghost that had cried out in a heartrending, piteous voice that was horrible to hear.

THEY had neither time nor inclination at that moment to solve the mystery of the phantom canoe that had flashed past them like a wraith. It was a time when even the fraction of a second meant the difference between life and death, between salvation and disaster. The island, they knew, was but a little way before them. When the next flash of lightning came, they would be given their last and only chance. If they did not gain the island, they would be swept past it to immediate destruction.

Every moment now the current of the rapids grew more swift, the waters more raging, more difficult to combat. Already the canoe was out of hand and their paddles all but useless in that violent, raging flood.

Neil Ranson heard Fountain's voice again.

"Stick to your guns!" he cried. "When the light comes, let her have it! It will be the end of things if we fail."

A moment after, the island was revealed, not fifteen yards away. Yet the current was like the rush of opened floodgates, and their fate was in the balance.

In the gleaming light Neil caught a glimpse of Fountain's face. His eyes were screwed, his teeth clenched, whilst the veins stood out upon his forehead like lug-worm casts on sand. With the strength of a desperate man, resolved to make one final, frantic effort to save his life and that of his young companion, he swung the canoe round, broadside-on to the stream.

She was caught like a cork by the flood, heeled half over, and was well-nigh swamped. Quick as thought, Fountain again plied his paddle, groaning as a man will do who exerts himself to the utmost.

It was as if the canoe pirouetted as a dancer does, spun round like a top. And then, with a thud that stretched both Fountain and the boy full length upon their backs, she lay beached upon a strip of sand in which her bows had been driven like a spade.

Darkness was again announced by rolling, reverberating thunder—thunder immediately above them. Fountain was on his feet in an instant. Groping in the darkness, he seized Neil by an arm and dragged the boy ashore. Though they were out of immediate peril, presence of mind was as necessary as ever.

"Haul her high and dry!" he cried. "If we lose her we're lost!"

Using their combined strength, they hauled the craft clear of the water, and, whilst they were thus employed, the black clouds above them opened with the greatest thunder-clap of all, and there descended a deluge.

It was as if the rain came down in one continuous sheet. It was not rain as we know it in temperate climes. They might have found themselves in the centre of a water-spout.

There was no wind. It was as if there was nothing to breathe but water, beneath the weight of which they could hear the branches of trees breaking with sharp reports like minute- guns.

And as the rain descended, the storm passed over to the south; the lightning became less vivid and occurred at longer intervals.

"We must make the canoe fast to a tree," said Fountain, "and give her all the rope we can. I've no idea how high the island stands above the level of the river; but you can take it from me that, after rain like this, the water will rise by feet, and the island may soon be flooded."

Fortunately they had on board a long tow-rope; for there had been times when they had employed friendly natives to tow the canoe—which contained all their supplies and ammunition—when they had found certain reaches of the river where the current had been too strong for them. The end of this tow-rope they now tied to the stoutest tree they could find, giving the canoe enough play on the rope to float free should the rising river completely submerge the island.

By this time a few stars had appeared in a clear sky of deep violet-blue. They discovered that the island was like a hog's back, reaching an altitude of quite twenty feet, and all along this central ridge were palm trees, many of which had been damaged severely by the storm.

And now they could hear for the first time the roar of the waterfall, but a little way below them—a dull, continuous sound, like the persistent beating of a great drum. Straining their eyes in this direction, they could see the vague outline of certain black rugged rocks, so far as they could judge, upon the very brink of the cataract, dividing the flood into many separate waves that swept downward to the lower rapids beyond.

As Fountain had predicted, they were drenched to the very skin, and there was no chance of drying themselves before sunrise. Nor could they light a fire, for there was not a dry stick upon the island.

"Neil," said Fountain, "prevention's better than cure. I prescribe quinine for both of us, to keep the fever out of our bones. And then we'll see what we can find to eat."

They searched the canoe for the medicine-chest and some sun- dried hippopotamus-meat which had been cooked the day before. This was unpalatable fare, but they were both well-nigh famished after their exertions.

"There'll be no sleep for you and me tonight," said Fountain. "We had best go for a walk to keep the blood moving in our veins."

He took the boy by an arm, and walked him to the other end of the island along the top of the ridge.

They found their place of refuge to be not much more than two hundred yards in length; and one might be disposed to think that it was a dull walk, in very truth, in the tropic starlight: from one end of the island to the other, and then back again, until by the end of an hour they had walked four miles at least.

But all the time Fountain talked to the boy. He told him tales, as he had often done before, of the forest and the veld, of the Great Lakes and the unknown snow-capped mountains in the heart of the interior; stories of wild men and hideous little dwarfs—the Batwa pygmies of the forest.

And then the moon came out—a glowing, crescent moon, hanging like a lantern above the tree-tops of the dark forest.

And the moon revealed what the starlight had never shown them. They stood together, still arm in arm, gazing down-stream from the lower extremity of the island.

They stared in mute amazement, like men who cannot believe the evidence of their eyes. They saw the smooth, swift water, gleaming like polished steel, and far down the river they could see the white foam in the rapids below.

The flood was already at its height. Many of the rocks were half submerged. The island itself had diminished considerably in area. But one huge rock, in the very centre of the cataract, stood forth like a fortress in the tide, black against the white surf down-stream.

And standing upon this rock, full in the moonlight, was the mystery of the falls—a sight that held them speechless and bewildered. They saw what appeared to be the figure of a man—and such a man as neither had ever seen before—one whose personal appearance, even the very garments he wore, caused them to believe they were dreaming.

FOR this man was no painted, half-clothed savage of the wilderness. He had neither the coarse, blunted features of the negro, nor was he even dark of skin. So bright was the moonlight, now that the storm was passed, that they were able to see distinctly every detail of one whom they believed at first to be a ghost.

He wore a white, skirted coat that reached almost to his knees, whilst round his waist was a girdle fastened with a bright metal clasp that glittered like silver. His hair was long and straight, and cut in a straight line level with his ears, and there was a kind of band across his forehead. Though he was too far away for them to see his features, as they found out afterwards, he was thin-lipped and his nose aquiline, more like that of a Jew than a negro. Moreover, he carried at his waist a short broadsword with a triangular point and a hilt in the shape of a cross—such a sword as had novel been fashioned in any forest forge.

In view of the peril of his situation and the mystery as to how he had got there, they could not believe at first that this was in reality a living man; until, upon a sudden, he raised his arms and cried out to them for help in some strange language that not even Fountain could understand.

Fountain gripped Neil Ranson by an arm and spoke in a voice that trembled with excitement.

"Tell me, Neil," he asked. "I've never been much of a reader of books. But, I fancy, I've seen pictures of people who dressed something in that style in bygone times: the Carthaginians or Egyptians—but, I tell you, I'm no scholar and never was."

There was no doubt that the man was endeavouring to attract their attention. They could not mistake his wild, almost frantic, gesticulations.

"He wants us to go to his help," said Fountain; "but, so far as I can see, no power on earth can save him. If the river rises higher, he'll drown like a rat before our eyes."

"Why," cried Neil, as the thought suddenly occurred to him, "this must be the man who came past us, more than an hour ago, when the storm was at its height!"

"That's right enough," said Fountain; "but how he managed to save himself in these rapids is little short of a miracle!"

"He must have jumped," said Neil, "at the very moment when his canoe was being swept over the cataract."

"Then he's as sure-footed as a mountain goat," the other answered; "and more than that, luck was with him, too. He could never have done it in the darkness. The lightning gave him his chance at the eleventh hour."

"It was the lightning that saved us, too," said the boy. "Had that flash not come when it did, we would have been swept past the island."

The man before them still cried out frantically for help. He could do nothing for himself, for the rock upon which he stood was not more than six yards across and wet and slippery with spray. He stood at his full height at the parting of the waters, with the rushing waves on either side of him, the cataract thundering at his back. It is hard to conceive a situation less secure.

Fountain turned away with a sigh. The very sight was alarming.

"We can do nothing!" said he. "We're powerless! Yet it's no easy matter to stand by in idleness when a man dies by inches. Even if the flood subsides, so far as I can see, he must starve to death. We can never hope to reach him."

"What about the tow-rope?" Neil cried, as the thought flashed into his mind.

Fountain whistled.

"I had forgotten that," said he. "You're right, my son! I believe the rope's long enough."

"Can we hold the canoe against the current?" asked the boy.

Fountain thought for a moment.

"We can twist it round the trunk of a tree," he answered. "He's in a dead-line down-stream. But you will have to go down in the canoe, taking both paddles with you. And even then it will be as much as the two of you can do to paddle against the stream, though I give all my weight and strength to the tow-rope."

John Fountain was a man with whom action followed thought. No sooner had he decided what to do than he lost no time in doing it. Selecting one of the stoutest trees that grew upon the island, they passed the tow-rope round it, and then carried the canoe to the water's edge. With Neil Ranson on board, she shot out upon the current to the limited extent of the rope, which Fountain grasped with both hands, placing a foot against the trunk of the tree to prevent it from slipping.

The boy found himself swinging in midstream, like the pendulum of a clock, about halfway between the island and the crest of the waterfall. So restless was the canoe that he was obliged to grip the gunwales tightly to prevent himself from being hurled overboard, whereas the rope itself creaked beneath the heavy strain that was brought to bear upon it.

Foot by foot, almost inch by inch, Fountain paid out the rope, letting it slip slowly around the tree, and still keeping his left foot firmly pressed against the trunk. Gradually the boat was lowered toward the cataract, as Fountain himself had described it, like a bucket into a well.

The rope chafed and grated against the soft bark of the tree, through which presently it had worn a deep groove to the harder wood beneath. Neil had received orders to shout with all his lung-power when he was within reach of the castaway; for, if he did not warn Fountain in good time, the canoe would be dashed to atoms against the rocks.

As he approached the edge of the cataract, Neil could not fail to realize the extreme peril of his situation. Fountain had been positive that the rope would take the strain—for the canoe was light—yet the boy was compelled to recognize the possibility that it might break at any moment, in which case he would be swept downward to the rapids below, where he could never hope to survive. There was also a danger that the canoe would be swamped; for the bows that met the full resistance of the current were no more than a few inches above the surface of the swirling, seething water.

But, great as the crisis was, though his life hung as upon a thread, the boy was rooted in amazement at the personal appearance of the mysterious stranger of whom he had now a better view.

The man stood motionless, like a marble statue, his arms folded upon his chest. He was straight of back and straight of limb, and held his head proudly. Now that he saw that a valiant attempt was being made to rescue him, he was quite calm.

Had it not been for his long black hair, he might have been a white man; for not only did his skin appear to be light in colouring, but he was unquestionably handsome. He was tall and slimly built; and, unlike a negro, both his hands and feet were small.

The canoe had been lowered stern foremost, the tow-rope being attached to the bows. And when she was not more than two yards from the rock, Neil gave the word to Fountain to let out no more rope.

"Jump!" cried the boy. "Jump for your life!"

The castaway at once realized what he was wanted to do. He crouched low, and almost before Neil was aware of it, had landed lightly in the body of the canoe.

An emergency which the boy had thought would be fraught with peril was over in an instant. The man had regained his balance in a manner that was little short of miraculous, and was now seated in the bows to trim the canoe.

Neil thrust the spare paddle into his hand and cried out to Fountain.

"All's well!" he shouted. "Pull for all you're worth!"

And now began a struggle in which all three put forth all their strength. In the canoe itself, Neil Ranson and the stranger wielded their paddles with desperate energy, to make what headway they could against the full strength of the stream. On the island Fountain strained and heaved until the perspiration poured off him.

The rope had been passed but once around the tree in the form of a loop; and this loop was prevented from slipping backward, allowing the canoe to lose headway, by Fountain's whole weight, assisted by his foot, which he kept against the trunk.

Whenever he heaved at the end of the rope, the loop slid around the groove in the trunk, already made smooth by friction. He was never able to haul in more than a few inches at a time; but every inch he gained was never lost, and there were intervals when they could pause to recover their breath.

It was a struggle between three men and the current of a flooded, swollen river. On the one side there was the weight of many tons of water; but on the other there was that divine intelligence which has made man what he is—and which conquered in the end.

Though it had taken but a few minutes to lower the canoe to the waterfall, more than an hour elapsed before Neil and the stranger were safe on shore. They beached the canoe high and dry; and then the stranger spoke:

"White man," said he to Fountain, "I bring you news of one of your own tribe."

Both Fountain and the boy let out a gasp. They could not believe what they had heard. They found it difficult at first to realize that this man had spoken in English.

"My own tribe!" Fountain exclaimed. "Who are you? And what do you know of my tribe?"

"I have a message," said the other in a strange, jerky accent, "a message from one whom you may know. His name is Tremayne."

IT must not be thought that the stranger could speak good English. Though he knew many words, he strung these together in so quaint a fashion that he was at times almost incomprehensible, whereas his pronunciation was difficult indeed to understand. The conversation that follows is not so much what he said as what he meant to say.

He told them his name was Idina, and that he came from a valley that was called Khandara, where there was a great city in which there lived a people ruled over by a queen whose name was Zarasis, who was as beautiful as the moon.

"My country," he declared, "is as old as the gods themselves. We came from the north. We have legends that tell of the ancestors of our Queen, who lived upon the banks of a great and sacred river."

Fountain turned to Neil.

"We've all heard rumours of a white race in the heart of the continent," said he; "and now I know it."

"When we were on trek," said Neil, "my father always carried in our wagon a few books, which I have read over and over again. One of these was the Bible, and another was a translation of Herodotus. In the Old Testament we read of traders who came from Ethiopia, where there must have been civilized countries, for Solomon had a throne of ivory and talents of gold. And Herodotus tells us of the deserters from Egypt who went down to the sources of the Nile and were never heard of again. Why should not these men have been the pioneers of a nation that has lived for centuries buried from the outer world?"

"Don't ask me, Neil!" said Fountain. "I'm no scholar, as I've said. You know more about that kind of thing than I do."

Turning to Idina, he questioned the man more closely.

"Two years ago," said the stranger, "there came into our land a white man who was great and strong and brave. He came alone, unattended by servants or companions. He was like no man that we had seen before. He was taller by a head and shoulders than any of our people; and the hair of his head and of his beard was the colour of sand, wonderful to behold.

"And therefore," he continued, "there were many of us who thought him a god. He was admitted into the presence of Queen Zarasis; and her woman's heart went out to him, for she had never beheld such a man."

"That I can understand well enough," Fountain cut in. "Tremayne had a personality that affected everyone he met."

"And he was wise," said Idina. "He was of great service to us. He taught us many things we did not know. He knew more of the stars than our astrologers; when we were sick, he knew better how to cure us than our sorcerers. He told us there were not many gods, but one God; and therefore he was hated by the priests."

"Is he still alive?" asked Neil eagerly.

The man bowed his head.

"He still lives," said he, "but as a prisoner. He has been cast into a dungeon by Punhri, the High Priest, who is jealous of his power. Until the coming of the stranger, Punhri was a power in the land of Khandara."

"And has Tremayne no friends in your country?" Fountain asked.

"He has many friends," replied the other. "I am his friend, or I would not be here, I would not have journeyed all these miles through a savage country, with news of him whom we call the White Wizard, the god with a beard of straw. The Queen loves him. And Dario, the Captain of the Host, has sworn to serve the Queen."

Fountain turned to Neil.

"It looks," said he, "as if Tremayne's in a bad way. There can be no mistaking what this fellow means. Tremayne has been living for three years or more in this buried city. If I know anything about him, he has learned the language."

He was interrupted by Idina who, becoming palpably excited, went on with his story.

"The White Wizard," he declared, "is in the power of Punhri, a sorcerer skilled in the black arts, famous for his magic. All fear him, for he is merciless and gifted with the 'evil eye'. Even the Queen herself dare not oppose him. It was the Queen who sent me out into the wilderness. I left her bowed down with grief, a prisoner in her own palace, weeping for your countryman, whose slave she is, though a queen."

Tears had actually come into Idina's eyes. He was in some ways more like a woman than a man. There was a gentleness about his manner and in the tones of his voice that one would not have expected to find in a youth who looked a warrior, who was tall and strong and straight of limb.

"It was the Queen who sent you on your errand?" Fountain asked. "Where did she send you? What did she ask you to do?"

Idina threw out his hands with a helpless gesture.

"It was our only chance," said he. "The White Wizard has a friend in Dario who commands the army, whose sword and whose strength alone protect the sacred person of the Queen from the wrath of Punhri. I serve under Dario, and it was at the Queen's command that I came into the forest across the mountains that encompass Khandara, to see if I could find men who belonged to the same race as the prisoner, that they might hasten to his help."

"And you have found us!" said Neil Ranson.

"You saved my life," said Idina simply. "Had it not been for you, I must have remained upon that rock until the tide rose to drown me, or I was so weak from exhaustion that I would have fallen to my death."

Fountain in the meantime had risen to his feet. He was not listening to what Idina had to say, but paced to and fro restlessly, like a man in a dilemma.

"Neil," said he, coming to a sudden halt, and gripping the boy by a shoulder, "you and I must decide once and for all whether or not we take the plunge. Can we leave Tremayne alone, a prisoner in this unknown city? Or shall you and I venture there, and see what fate holds in store for us?"

The boy never hesitated a moment. He believed John Fountain to be the greatest man on earth.

"I'll follow you," said he. "If you decide to go there, I'll come with you willingly enough."

Fountain held out a hand.

"Shake," said he. "It's a bargain, Neil, for good or ill. Idina shall guide us. You and I will behold with our own eyes this city of Khandara."

IT would be tedious to describe in detail a journey that took them more than a month. Idina guided them by the sun and by the stars toward the north. Leaving the river valley, where they left their canoe, they were many days in the forest; and when, at last, they came forth again into the sunlight they were all but skeletons, half starved to death, their clothes torn to ribbons.

Night after night, when they talked together at the camp-fire, Idina told them of Khandara, a city as wonderful as Memphis or as Thebes. And he described the gods that he worshipped—Osiris, Isis, Horus, and some score of others—the gods that had once been worshipped on the Nile. The citizens of Khandara were a cultured people, skilled in the arts, great masters of architecture, who could both read and write, making use of hieroglyphics little changed since bygone times.

Punhri—so Idina said—was the declared enemy of the Queen. He could not dethrone Zarasis, for she ruled by divine right, herself a divinity, the descendant of Osiris. But there was little else he dared not do. He disobeyed, and even cancelled on occasions, the royal commands. He thwarted the Queen at every turn. He allowed her no hand in the government of her kingdom, and saw to it that any who defied his authority were put instantly to death.

All this had Queen Zarasis borne in patience and without protest during the ten years that she had reigned—for she had become Queen on the death of her father when she was but a child of twelve. But now the High Priest pitted himself against her upon an issue which was to the Queen more than all her realm.

"I myself am a centurion in the royal bodyguard," Idina said, "the commander of a hundred men. I am therefore often on duty in the palace, where I have seen with my own eyes that Queen Zarasis loves the white man."

"And what of Tremayne?" asked Fountain. "What has he to say to it?"

Idina smiled.

"He has looked upon the Queen," said he. "He has seen that Zarasis is beautiful as moonshine upon lilies. If the Queen had her own way, she would place the White Wizard upon her throne; she would make him king of Khandara. Instead of which he has been thrown into a dungeon, where he lies awaiting the pleasure of Punhri, whose heart is like the heart of a poisonous snake."

Fountain turned to the boy.

"We'll get there too late to help Tremayne," said he. "He will have been put to death, murdered in his prison."

Idina, who every day was becoming more proficient in the English language, understood what had been said.

"I do not think so," he replied. "There are certain things that even Punhri cannot accomplish. The Queen has sworn an oath that she will worship daily at the shrine of Horus, that she will not paint the nails of her fingers, until the prisoner is set at liberty. Dario is with her. The royal bodyguard to a man would die for her. If any harm befalls the White Wizard, it will mean civil war."

Dario he described as the greatest warrior in the country, one who in battle gave no other order to his men than to follow where he went. His dazzling golden armour was for ever in the forefront of the fight; and he was scarred by wounds he had received in wars against savage forest tribes.

Punhri, the Sorcerer, on the other hand, held power by dint of his magic and what was called the "evil eye." There was no one who was proof against his subtle influence; all were afraid of him, save only Dario.

Because of these long nightly talks they felt, as they drew nearer to their destination, that they would not arrive as strangers in the city of Khandara.

At last they came forth from the forest upon an open, park- like country where they were able to make greater progress, often marching as many as thirty miles a day. This eventually became an open plain where herds of antelope abounded and where nothing grew but long, rank grass that waved in the wind like rye.

They did not want for food in these days; for, though they had left all their shotgun ammunition and such surplus stores as they could spare in the place where they had hidden their canoe, they had brought with them three rifles and their revolvers, dividing the ammunition for these equally between the three of them. Indeed, with the exception of the medicine-chest, they carried little else but arms and ammunition.

It took them three and a half days to cross the plain, which rose upon a gentle gradient to a higher altitude. Before them, wonderfully distinct in that clear atmosphere, was a great range of mountains, many of the peaks of which were snow-capped, that extended in a semicircle across the northern sky.

It was the convex, or outer, side of this semicircle they approached; but, as they drew nearer, they perceived in the far distance even higher peaks, which Idina described as belonging to the same rugged range.

He told them that these were the Mountains of Khandara, which formed a kind of fortress barrier around the valley where his people had lived for centuries. Many of the crags were so high above sea-level that they were often under snow.

Within this valley, which was more than fifty miles across, was a rich plain where there was a lake, upon the south side of which stood the city of Idina's people. The whole valley was cultivated: maize, corn, melons and ground-nuts being grown at different levels.

As they began the ascent of the lower slopes of the range, they realized for the first time how truly inaccessible to the outside world was the forgotten civilization that lay beyond. For the chasms, the great ravines and precipices that lay before them were, indeed, formidable; and there is little doubt that, if they had not had Idina to guide them, they could never have found a way across.

The man led them along narrow shelves of rock but a few feet across, a yawning abyss on one hand, a sheer cliff upon the other, rising to the very clouds.

Half-clothed as they were, after the steaming, stifling heat of the tropic forest, they were perished by the cold. By night, in the freezing starlight, when the moon shone bright upon the snows above them, they found it impossible to sleep; and yet, so perilous were these crevices and crags that it was only by daylight that they dared venture to climb.

They gained the summit upon a certain evening when there was no cloud to be seen in the sky. The tooth-shaped, snow-capped peaks were on either side of them, when they looked down upon what was, indeed, a wondrous sight.

In the clear evening light they beheld a plain, well-wooded save where it had been given over to cultivation. This plain was almost circular, embracing an area of near upon three thousand square miles, and, although the far side of it was shrouded in the evening mist, the mountain range beyond was clearly visible at a distance, perhaps, of sixty miles.

Near the centre of the plain, though somewhat toward the south, there was a lake as blue as Como, shaped roughly like the ace of hearts.

From that altitude the water was like a mirror, smooth as glass. Scattered upon the lake were islands; and on nearly every one of these were two or three great buildings, square, flat- roofed palaces with many windows, white in the sunshine, as if they had been built of marble.

But the greatest wonder of all was the city itself lying, as it seemed, upon the margin of the lake, but a little way below them. For here were temples and mansions, palaces and gardens, wide streets and open squares, great obelisks and gigantic statues, hundreds of feet in height, of strange, heathen gods.

"Behold!" Idina cried, with pride ringing in his voice. "Behold, the city of Khandara!"

BY the following evening they had gained the wooded country at the foot of the northern slope, which was very different in character from the steep ascent upon the other side. For it was no more than a gentle gradient where they could walk upright and without danger, though it was sometimes necessary to be careful.

Idina conducted them to a grove of gigantic yew trees, where there were also junipers and witch-hazels; and here they camped for the night, lighting no fire, however, for fear that they might attract the attention of the peasants whom they had seen working in the fields.

"You must remain here," said Idina, "until to-morrow night. Before daybreak I will return with news. On no account must you show yourselves, but remain hidden all day long. I go my way into the city to find Dario, who will befriend us."

"And then?" Fountain asked.

"I must warn them of your coming," said the man.

"But how are we to get into the city without being seen?" asked Neil. "It is surrounded by a great wall; and, surely, all the gates are guarded?"

"I know of an underground passage," Idina answered. "This leads from a secret entrance in the outer wall to the interior of the palace itself, beneath which are catacombs where the bygone monarchs of our race are buried. Formerly this passage was used by the priests, who were not permitted within the palace, who offered sacrifices by day and night for the souls of the departed. These rites are no longer observed; the passage is therefore never used; but Dario has the key."

Soon after that, Idina set forth alone upon his journey, whilst Fountain and Neil were glad enough to avail themselves of an opportunity to rest. Not only did both sleep soundly during the greater part of that night, but they dozed continually throughout the heat of the day. The arduous journey they had accomplished through the forest and across the mountain range had utterly exhausted even Fountain, who was as hard as nails. They had endured the extremes of temperature. They had passed through tangled, almost impenetrable thickets; they had waded knee-deep in quagmires, where they had been attacked by leeches; they had climbed mountain crags where the slipping of a foot would have meant instant death; and Neil Ranson had reached that state of physical fatigue when it is impossible even to think.

The evening of the next day found them refreshed and rested. There was a stream in the wood near by where they could quench their thirst as often as they liked; but both were conscious of the pangs of hunger before nightfall.

It was about one o'clock in the morning when Idina returned, approaching so silently through the wood that he took them by surprise.

"Come," said he, in a quiet voice, "Dario, the Captain of the Host, sends you greeting. At the same time he warns you that once you pass the city walls, you take your lives in your hands. He cannot be answerable for your safety."

"For that," said Fountain promptly, "we care little. Our main concern is to know whether Tremayne is yet alive?"

"Not a hair of his head has been touched," replied Idina. "The High Priest has tried every means to persuade the Queen to sign his death warrant."

"And she refuses?" asked Neil.

"She declares," said Idina, "that she herself would rather die. But, my friends, there is no time to lose. It is necessary that we enter the city before daybreak. Dario himself awaits us at the outer wall."

They followed a kind of bridle path that led downhill toward the lake. In the moonlight, as they drew nearer the city, they could see the towers and minarets of Khandara standing forth under the starry sky. The moonlight shimmered upon the surface of the water, where the palaces upon the islands resembled fairy castles. It was a land of wonders and amazement. It was like the city of a dream. As they came within sight of the great, massive walls, they could hear the night-watchmen, stationed upon the turrets, calling the hour from post to post.

But when Neil Ranson beheld Dario, the Captain of the Host, the boy was lost in admiration. For this mighty man of war reminded him of one of the paladins of old.

He was deep of chest and broad of shoulder; his bare, hairy arms were like those of a Hercules. In his golden armour, glittering in the moonlight, he was a soldier every inch. As Shakespeare has it, he was "bearded like the pard," and his face so disfigured with sword-cuts and white, horrid scars that he looked like a bulldog that is for ever fighting.

He saluted the strangers by raising his right hand above his head, and then addressed them in his own language, Idina acting as interpreter.

"Welcome to Khandara!" said he. "You are brave men upon a braver mission. I have orders to conduct you to the Queen."

"She will see us to-night?" asked Fountain.

Dario bowed. "We repair to the palace by way of an underground passage that is never used," said he. "We will be met by Didorian, the Queen's chief maid-in-waiting. I saw the Queen myself last evening. She gladly welcomes you, not only as honoured guests, but on behalf of the white man who is a prisoner in the castle."

Fountain, as he often liked to declare, was essentially a practical man. He had no wish to act in the dark.

"To gain admittance to the palace seems simple enough," said he; "and I have little doubt that we can escape from the city by the way we came, should that be necessary. But what concerns me most is the future. What are we to do when we are once inside the palace?"

Dario threw out his great hands.

"We are the children of the gods," said he. "Osiris watches over us; it may be that Anubis awaits us at the gate of the tomb. Destiny is ruled by the stars."

John Fountain shrugged his shoulders.

"Lead the way," said he. "My friend and I will follow."

Holding to the shadow of the city wall, they came presently upon a soldier whom Dario had posted at the entrance to the passage. This man carried a long spear and wore a square-cut beard, like the Captain of the Host himself, who opened with a key a little door in the wall that was no more than two feet square, through which they were obliged to crawl on hands and knees.

The soldier going before them with a lighted torch, they walked for a mile or more along a dark and narrow tunnel, until they came at last into a series of catacombs, where they entered one chamber after another, all alike inasmuch as the walls were adorned with various pictures and designs.

And then, a final spiral staircase brought them into a chamber that was magnificent to see. It was of marble, and in the centre of the floor was a great bath where a fountain played. At the top of the steps that led down into the bath was a couch, the ends of which were most wonderfully carved to resemble the heads of lions.

From the farther end of this great room a lady came toward them. She was but a girl in years, and very beautiful and slender. She was clothed in a tight-fitting garment that was caught about her knees, and around her head was a silver bangle.

When she saw the two Englishmen, she prostrated herself before them, actually going down upon her knees—for in this country it was the custom for the women to pay homage to the men.

When she had risen, she addressed them, Idina interpreting her words.

"Didorian, at your service, sirs," said she. "The Queen has bidden me conduct you into her presence."

"She is awake?" Idina asked.

"I left her sleeping," replied the lady. "Every day now she seems to grow more weary, more heavy of heart. The very fact that you are the friends of one whom we all admire will rejoice the heart of Zarasis."

"Is the Queen to be disturbed?" Idina asked.

Didorian smiled.

"Her commands were that I should take you to her the moment you arrived."

"Then, lead on," said Dario. "Go before us, and acquaint the Queen that we are here."

Following Didorian, they crossed the great room of the Bath, and entered a smaller chamber the pillars in which were painted all the colours of the rainbow. And here was a door with a great golden knocker, fashioned like the head of a hawk.

Didorian knocked three times, each time louder than before; and then, receiving no answer, she somewhat timidly turned the handle.

"Zarasis sleeps," she whispered. "Wait here. I will awaken her."

Silently she opened the door and passed into the room beyond, which was but dimly illumined by a single lamp burning upon a marble pedestal.

And then, upon a sudden, those without heard her give a faint shriek that was little more than a gasp.

Dario took a step forward, to meet Didorian upon the threshold. In the glaring light of the outer room the lady's face was like ash. Clasping her hands together, in the utmost state of alarm, she addressed herself to the Captain of the Host.

"The Queen is gone!" she cried. "She is not here!"

"Not here!" Dario exclaimed. "Impossible!"

"It seems so," she answered in a weak, faltering voice. "I left her sound asleep not three hours ago. And now—the Queen is gone!"

DARIO strode into the inner room, followed by the others. When more lamps had been lighted they found themselves in a magnificent chamber, the entire ceiling of which was of carved tortoise-shell. Incense burned before an image of the great god, Horus, the special deity that was supposed to watch over the fortunes of the Queen; and near a window was a wide couch, the cushions upon which were crumpled and bore the imprint of a human body.

"She slept there but a while ago!" said Dario. "And yet she is not here now."

"There is another door," exclaimed Didorian. "The door that leads to the garden. She never passed through the Room of the Bath, for I have never left it, and I have been awake all night."

"We must find her!" cried Idina. "There is black magic at the root of this!"

Like men who but vaguely understand what they are about, Fountain and Neil Ranson accompanied the others down a long corridor and a flight of steps, until at last they came forth into the palace garden.

They searched everywhere, and yet could find no trace of Queen Zarasis, until at last they came to the gate where two sentries were on duty, from whom they learned that the Queen had actually passed through the palace gates on foot and unattended, but a few minutes since.

"Fools!" cried Dario, when he was recovered from his amazement. "Fools, not to have reported it to the officer of the guard."

The men protested that they had not dared oppose the Queen; but Dario was not disposed to waste valuable time. Never before in the history of the nation had the reigning monarch walked alone and unattended in the public streets.

He turned quickly to Idina and ordered him to tell the two white men to return at once to the palace with Didorian, since it would be disastrous if they were seen in the city.

"Beyond doubt," cried Dario, "Punhri, the Sorcerer, has cast a spell upon the Queen."

Without wasting further time, and accompanied by Idina, he hastened into the street, whilst Didorian conducted Fountain and Neil back to the palace, where they awaited in grave anxiety in the great Room of the Bath.

The lady Didorian was in such distress that, from time to time, she brushed the tears from her eyes. Fortunately, however, they had not long to wait, for presently Dario returned.

The Captain of the Host walked, not looking where he went, but gazing down into the face of the woman whose hand he held in his.

She wore a robe like that of Didorian, save that it was made of more beautiful material; and the circlet around her head was of silver studded with gems, from which pendants hung down on both sides to below her ears. Around her neck was a necklace of great precious stones, of varied colours, and there were bracelets upon her arms above the elbows.

But it was her face that held both Neil and Fountain rooted in admiration. Her beauty was wonderful; but her expression, her whole deportment and demeanour, were even more remarkable.

For she walked as one who walks in sleep. Her eyes were wide open, and yet she did not appear to see anything. She moved slowly and with precision, though without looking where she went. The very paleness of her countenance suggested that she had been thrown into a trance.

Idina followed close upon her heels. He had the appearance of one who was both excited and alarmed.

"Of a certainty," he cried, "there's Black Magic here! Queen Zarasis has been bewitched."

"'Tis Punhri!" exclaimed Didorian. "This is the work of the Sorcerer. I know it."

Dario's hand went swiftly to the hilt of his sword—a sword so long and heavy that an ordinary man would have required two hands to wield it.

"Have you proof of that?" he asked, turning to the lady.

"Night after night," she answered, "I have seen him from the palace roof. He lives, as you know, not far from here; and of late it has been his custom every night, after the moon has risen, to appear upon the roof of his house, where he stands quite motionless, as immovable as a Sphinx. And then, upon a sudden, he throws up his hands toward the heavens, with the action of one who implores the assistance of occult and hidden forces."

"I can well believe it," said Dario. "The villain is a master of magic, as I know to my cost. There was a time when one of my most trusted officers fell under his influence. He had no will of his own; he could do nothing but obey the unspoken commands of Punhri."

"Day by day," said Didorian, "I have seen his evil power gradually work itself upon the Queen. She is afraid of him. She told me once that she felt herself to be no more than a feather on the wind. She drifted, despite herself, toward some dreadful and mysterious fate."

The Captain of the Host clenched his teeth, which showed ivory white in the blackness of his beard. With a ring his great sword leaped from its scabbard.

"Were I sure that were the truth," he cried, "though it cost me my eyesight, with this sword would I smite off Punhri's head!"

It was Didorian who now proved that she had not lost her woman's common sense.

"Of what avail, great Dario," she asked, "are hot words? Our first care is for the Queen; and it remains for us to find out, if we can, what mischief is afoot. Punhri has surely a reason for having cast a spell upon Zarasis, for having willed her to leave the Palace at so lonely an hour?"

The captain stroked his beard. For a moment he stood silent. Then, upon a sudden, he snapped a finger and thumb.

"I have it!" he exclaimed. "We'll snare the jackal! Do you, Didorian, dress yourself in the Queen's clothes, cover your face with a heavy veil, and leave the palace gates for the house of Punhri. Walk, as Zarasis walked, like one who dreams. There may be no need for you to speak; or, if you must, your voice might be mistaken for the Queen's. Bold as he is, he would never dare to snatch the veil from your face. Whilst you are with him, you should be able to find out what wickedness he means."

Didorian, as she listened, grew pale, and before Dario had finished speaking she had thrown herself down upon her knees, her hands clasped before her.

"Dearly as I love Zarasis," she cried, "this is more than I dare do! I tremble at the very sight of Punhri; I fear his evil eye. Nor dare I walk abroad in the streets at dead of night. What you propose, brave Dario, would only end in disaster. My heart would fail me at the eleventh hour. My duty, surely, is with the Queen herself?"

"You may be right," growled the Captain with a shrug. "I have lived my life with warriors, not women. Attend to the Queen. She sorely needs your aid."

Without another word Didorian led Zarasis back to her chamber.

As for the others, they remained without, in the Room of the Bath, where Idina supplied Neil and Fountain with a meal of cakes of wheaten flour and maize, luscious fruits such as pomegranates and the juice of prickly pears crushed in cream skimmed from goats' milk, whilst he explained to them the conversation that had taken place between Dario and the maid-in-waiting.

And it was then that Neil Ranson decided upon a course of action as rash as it was dangerous. Though he had been but a few minutes in the palace of Khandara, he was already a staunch partisan on the side of Queen Zarasis. He was determined to prove at the very outset that both he and Fountain were ready to risk their lives for right and justice.

"I am no taller than the Queen," said he, "and could be made to seem as slender. Why should I not be dressed in her clothes and veiled? Why should I not find my way to the house of the Sorcerer, if I am told which way to go? I have seen the Queen, and I know well how to act as if I were in a trance. Dario has declared that, being in a trance, I need not speak, but I can see through my veil all there is to see."

The Captain grasped the boy by both shoulders.

"Do you mean this?" he cried.

"Every word of it," said Neil. "I can promise nothing, except that I will do my best."

Dario burst into laughter.

"It is agreed," he cried. "I see now that there have come to Khandara those who will bring Punhri to his knees."

Not willingly did John Fountain assent to this. If he said nothing either for or against what had been suggested, it was because for the first time in his life he was at a loss to explain or to understand the situation in which he found himself.

Idina repaired to the Queen's chamber, knocked upon the door, and borrowed from Didorian a robe that the Queen often wore. When Neil was clothed in this, Didorian dressed the boy's hair, which had not been cut for weeks, and fastened around his forehead a golden circlet, in the front of which was the hooded head of a cobra fashioned in jade. Beneath this she had disposed a heavy veil that completely masked Neil's face. And when she stepped back and regarded her handiwork she clapped her hands like a child.

"It is the Queen herself!" she cried.

The boy was accompanied to the gates of the palace by his three companions, and there Dario gave orders to his astonished sentries to allow the Queen to pass. And Neil Ranson found himself alone in the wide, dark streets of the city of Khandara.

NEIL had already received definite instructions from Idina, who had told the boy to follow the main street, at the end of which was the palace gate, until he came to a square where there was a great obelisk guarded by two sphinxes that faced the east. He was to turn from this square toward the left, when, after walking a distance of about two hundred yards, he would come upon another, though a smaller, square, in which he could not mistake the palace of Punhri, for a flight of stone steps led to the portico, upon either side of which was a great image of a Sitting Scribe, as evidence that within lived one of the wise men of the land.

Arrived at his destination, Neil would be obliged to use his own discretion. He had a difficult part to play, but he must play it skilfully, or else his life would be forfeited.

Mingled feelings played havoc with the boy's imagination as he wended his way along the wide, straight street. He beheld Khandara for the first time in his life, and he saw it in the moonlight, at an hour when the streets were more or less deserted. He encountered only two or three wayfarers, men bare of foot who slunk past him stealthily, like cats, and then turned to regard him in amazement.

He walked as quickly as he dared until he came to the larger square, that impressed him more than anything he had yet seen, for it was crowded with the statues of goddesses and gods, all graven in a white stone that made them appear in the moonlight an army of colossal ghosts. And in the midst of these was a tall tower, sharp-pointed, rising more than two hundred feet into the air.

Neil, obedient to his instructions, took the main street to the right, and came in a little while upon another square, where the moonlight fell full upon an imposing building at the head of a flight of steps.

Here were the Sitting Scribes; and this place was therefore the palace of the Sorcerer. Growing more fearful every step he took, his heart beating violently, Neil ascended the steps slowly, keeping his body as motionless as he could, as if he walked in his sleep.

As he approached the doorway he faltered. Having no means of knowing what kind of reception was in store for him, he had made no plans. He had not the least idea what he was going to do. And then, very swiftly, and yet quite silently, the door before him opened.

He found himself in a wide hall, or passage, the floor of which was of mosaic. This hall was lighted by ornate metal lanterns suspended upon chains. And the light from these was red—a dull, ruby red—which, together with the strange intoxicating smell of incense with which the atmosphere was charged, gave the boy the immediate impression that he had found his way into a temple.

For the moment, however, he was overawed by the appearance of the man in whose presence he found himself. Punhri, the Sorcerer, the greatest man in the kingdom of Khandara, stood before Neil Ranson, whom he believed to be the Queen, for he bowed low, extending his arms before him.

And then he straightened, and laughed in his curled, square- cut beard.

He was somewhat above the middle height and very thin. His long hair, black as jet, hung down to the nape of his neck, where it was cut in a straight line. His eyebrows were dark and well defined, meeting upon the bridge of a nose that was like the beak of a bird of prey. In his eyes there was something terrible —a strange, metallic glint. They were like the eyes of a serpent.

Very deliberately he raised his hands and made a few passes before the boy's face, after the manner of a mesmerist. Neil was at once vaguely conscious of a sensation as if he were falling under the influence of an anaesthetic. At the same time, he could not fail to notice Punhri's hand, the fingers of which were long and claw-like, whilst upon many were rings in which were set gigantic emeralds and rubies.

He spoke in a deep voice; and although Neil could not understand a word, there was no mistaking the man's meaning, for he immediately turned upon his heel and walked slowly down the passage, at the end of which he ascended a narrow flight of stairs.

The boy followed, still like one in a trance. Indeed, the very atmosphere of the place and the personality of this extraordinary man made him feel that he might, at any moment, completely lose possession of his willpower.

They entered a little room at the head of the staircase, where the walls were draped with fantastic curtains that bore many strange, cryptic designs and mystic symbols. Here, too, was an oil lamp that burned with a bright-red glow upon a pedestal, at the foot of which, upon a slab, was a great crystal that reflected many beautiful prismatic lights.

There were several tables in this room, upon which were skulls and bones and little images of human beings made of clay and stabbed with golden pins. There was a huge lizard, too, more than three feet in length, that, as they entered, darted swiftly across the floor.

Punhri went straight to a small central table upon was which a roll of papyrus covered with hieroglyphics. Without a word, he thrust into Neil's hand a stylus, and with a gesture intimated that the Queen was to sign her name to the death warrant of the prisoner.

Suddenly aware of this, acting upon the impulse of the moment, Neil drew back, and cast the stylus upon the floor. And a moment after he believed that his last hour was come, for Punhri stood before him, his eyes ablaze with wrath, his arms stiff and quivering at his sides.

For a moment there was silence. They stood facing each other. And then the Sorcerer, with a loud cry that might have been an oath, seized Neil by a wrist and dragged him across the room.

He flung open a door, through which he hurled his victim. The door slammed. Neil heard the key turn sharply in the lock.

He found himself in comparative darkness, in which, coming from the red light of the outer room, he could not at first see a yard in front of him. A moment elapsed before he realized that he himself was now a captive—a prisoner in the house of Punhri, the Sorcerer.

IN a moment Neil's eyes had grown accustomed to the semi-darkness of the room. It was a bare, unfurnished chamber with a dome-shaped roof, and in one wall was a window about eight feet from the ground through which the moonlight streamed.

He realized at once that there could he no escape, unless by way of this window. Never in his life had he been so alarmed. Though he had seen Punhri for little more than a minute, he dreaded the man, whose appearance was sinister and forbidding.

Neil approached the window, to find at once that his movements were hampered by the tightness of the skirt he wore. Hitherto he had walked with short strides, imitating as well as he could the actions of a sleepwalker; but now, when he would jump to the level of the window-sill, which was well above his head, he saw that he must have the free use of his limbs, that he could do nothing in a woman's gorgeous dress that was caught tight around the knees.

The dress was of the very finest silk, into which had been interwoven threads of gold that shimmered in the light at every movement. Neil Ranson caught the hem of the skirt in both hands, and with a jerk tore it, ripping it upward, so that he had now the free use of his legs. With a rush he sprang and caught the window-sill, hoisting himself from the floor.

And here two details are of importance in regard to the architecture of Khandara. In the first place, these wonderful people had not yet invented glass, and, so far as the windows of their houses were concerned, glass was quite unnecessary, for the climate was never cold, and when it rained—as if often did—a kind of shutter was lowered, made of wood, that well served its purpose. Secondly, the roofs of the houses were flat, and these were often used as gardens, palms and tropical shrubs being planted in great earthenware pots arranged in rows.

Neil, seated upon the window-sill, found himself at a perilous height above the ground. The foundations of the house itself were well above the square in which it stood, and the long staircase Punhri and the boy had ascended had lead direct to the uppermost storey.

This window looked down upon the roofs of the neighbouring houses. In the moonlight the Royal Palace could be seen at no great distance, whilst the great obelisk, that was like Cleopatra's Needle, arose from the central square.

Level with the window-sill was a narrow ledge of masonry about two feet in width, which appeared to surround the entire building. Standing upon this, and grasping the woodwork of the shutter, Neil Ranson took in his surroundings.

The parapet of the roof was no more than nine or ten feet above him. But, from a position so precarious, he dared not jump, though he soon satisfied himself that the wooden shutter was strong enough to take his weight.

As swiftly as he could, and yet with extreme caution, he climbed until he was within reach of the parapet. He had always been as active as a monkey, and having a good head for heights, presently he found himself upon the roof of the building.

Here were neither plants nor palms, nor had any attempt been made at decoration. There was a table and a chair, and upon the table were many strange astrological instruments, which conveyed nothing to Neil.

The roof was square, and the boy had no need to walk round the parapet more than once to discover that he could not possibly hope to escape by way of the outer wall.

There were, however, at the eastern extremity of the roof, two stone images of those quaint dog-headed creatures whose duty—according to the ancient Egyptians—was to entrap the souls of human beings in a net. And between these was a flight of steps that led downward to the interior of the house.

As may be imagined, Neil dreaded to return, but he could not fail to see that he had no alternative. He must descend the stairs, trusting to providence that he would not be discovered, and that he would be able to find some way of escape.

The steps were in utter darkness, for they were spiral and therefore shut out from the moonlight. And this, in one sense, was fortunate, for the boy had not gone far when, to his utmost consternation, he heard footsteps approaching. Someone was ascending.

The central pillar around which the staircase turned was not round, but shaped like a figure of eight. In consequence of this, the steps were wider in some places than in others. And holding his breath, standing stiff and upright, Neil squashed himself into this central recess, where in fear and trembling he awaited the approach of the newcomer.

Someone passed quite near to him—so near, in fact, that he was brushed lightly by a flowing robe. A few moments after the man must have come forth upon the roof, for Neil heard the deep voice of one who spoke aloud—a voice that he recognized at once as that of the Sorcerer himself.

He waited no longer. Something like sheer terror possessed him. He was resolved to escape, if he could, whilst there was time. Punhri, at any rate, was out of the way.

Reaching the bottom of the steps, he found himself in a great room that he had not seen before, which he presumed to be upon the ground floor. Here were several doors, and, opening one at random, he entered a long, bare chamber where several men were asleep.

These were no doubt the High Priest's servants, for they wore little or no clothing, and lay upon rough beds of rushes. There was light enough to see every detail of the place, since the uncurtained window admitted the full rays of the moon.

Neil remained quite still long enough to satisfy himself that all these men were sound asleep. On tiptoe he then crossed the room and vaulted lightly to a window, where he discovered to his intense relief that he was not more than seven feet from the ground.

He dropped into a narrow thoroughfare, where, without thinking where he was going, he set off running as fast as he could.

He had not gone far before he came to a sudden halt. He did not know where he was. He could not find his way back to the palace unless he first found the smaller square in which stood Punhri's house. He therefore retraced his steps until he saw one of the great statues of the Sitting Scribe. And now, recognizing where he was, it took him not more than a few minutes to race to the Palace gates.

There he found Dario awaiting him, with whom also was Idina.

"You have returned in the nick of time," said Dario. "We have anxiously awaited you. In half an hour it will be daylight, and the streets thronged with people."

"Have you discovered anything?" Idina asked.

"I have found out much," replied the boy. "I have entered the house of Punhri. The Queen was thrown into a trance that she might sign the death warrant of Tremayne."

The Captain laughed loudly in his great black beard.

"We'll pay Punhri back in his own coin!" he cried, when he had heard the whole story from Idina. "He has cast a spell upon the Queen; he has dared to place her under lock and key; and it will seem as if she has been spirited away. We will cause Punhri to believe that this is the work of the White Wizard, the man whom above all others he hates and fears, of whom he is vilely jealous."

Dario could not continue speaking. Laughter compelled him to hold his sides. He clapped his great hands upon the golden breastplates of his armour.

"This is the greatest joke that ever was!" he roared.

But Idina was of a more serious turn of mind than this blunt, boisterous soldier.

"Naught can be a joke," said he, without a smile upon his face, "where Punhri is concerned. The High Priest is a sorcerer who can at any moment summon to his aid all the imps and devils of the Underworld."

FOR the next few days Neil Ranson and Fountain were housed in secret in a suite of rooms in the Royal Palace, and here they were given all the luxuries that the city could provide.

Dario, the Captain of the Host, took the wise precaution of swearing to secrecy every one of his men, all of whom were quartered in the palace itself. It was believed, also, that the palace servants could be trusted, and it seemed improbable therefore that the secret could leak out. And all this while Henry Tremayne was held a prisoner in the great Castle, built upon one of the largest islands in the lake.

During these days the two royal guests had many talks with Dario and Idina. They were all agreed that some attempt should be made to set the prisoner free; but exactly how they were to set about an enterprise so hazardous it was not easy to decide, for it was possible to approach the Castle only by boat, whilst the place itself was strongly guarded by the civic soldiers, or militia, all of whom were in favour of Punhri and in opposition to the Queen.

The Sorcerer had already played his cards with an exceeding cleverness. There can be little doubt that the High Priest aimed at the throne. He had, therefore, caused a rumour to be bruited abroad that the Queen was bewitched, that she had fallen under the evil influence of the White Wizard, whom, for that very reason, he held a prisoner in the Castle. Unfortunately, Neil Ranson, disguised as the Queen herself, had been seen at dead of night in the city streets. This unheard-of occurrence was soon the common talk of the people, who were rapidly coming round to the belief that the Queen was, indeed, possessed of an evil spirit, and therefore incompetent to rule.

Punhri, in making his plans, had overlooked nothing. Whilst using every effort to bring the Queen under his hypnotic influence, he had caused certain soothsayers to predict in the market-place and at all public meetings that very shortly a great calamity would befall the nation, that a dynasty that had survived for centuries would suddenly come to an end.

The laugh was no longer on the side of Dario. It was a very serious and wrathful warrior who conferred nightly with John Fountain and Neil.

"Every day," said he, "Punhri becomes more powerful. Soon he will take it into his own hands to put to death the White Wizard to whom we owe so much, though by the law of the land no one has the power of life and death but the reigning monarch."

"We must rescue him," said Fountain, "and lose no time about it."

Dario shook his head.

"Were I to attack the Castle with the guard," said he, "I could rescue the captive in less than an hour. But it would mean civil war. Not only the people, but the priests, too, would be against us."

Idina now spoke deliberately, with his eyes fixed upon the floor.

"Let no such calamity fall upon Khandara but as a grave necessity," said he. "Listen, I have a friend who is in the priesthood, who serves in the Temple of Isis, and from him I have heard that Punhri will shortly revive a cruel and horrible ceremony which has not been practised among our people for many years."

"What will he do?" asked Dario.

"He is about to restore a foreign god who long ago was worshipped in Khandara. The Sorcerer, as the High Priest of the nation, will announce the Feast of Moloch."

"The god of Fire!" exclaimed Neil.

"That is so," said Idina, "though how you should have heard of Moloch I cannot tell, for he is a god who demands a human sacrifice; and, if Punhri brings him back into the land, you may depend upon it he will declare to the priests and to the people that Moloch must be appeased for generations of neglect."

John Fountain sprang to his feet.

"I see what you're driving at!" he cried. "The Sorcerer proposes to restore this barbaric custom, since he can think of no other way of getting rid of Tremayne."