RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

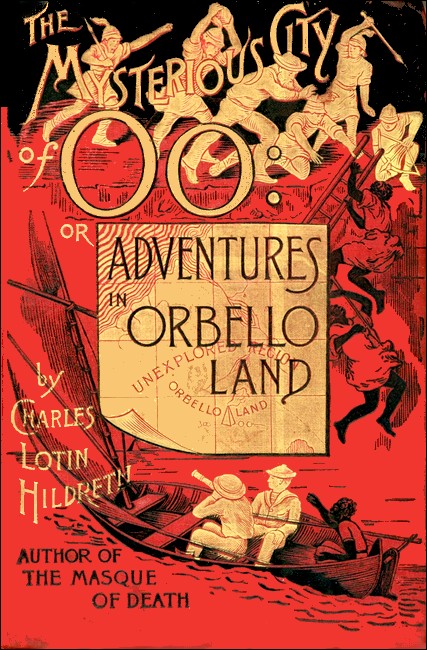

Belford Clarke Company, Chicago, 1889

Federick Warne and Co., New York, 1893

W.B. Conkey, Chicago, 1889

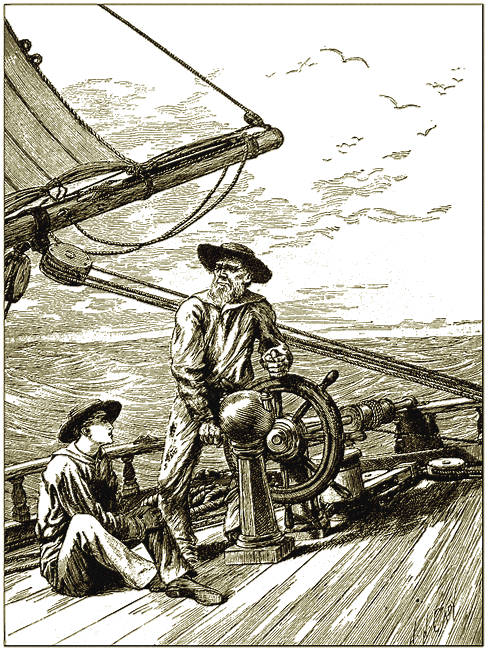

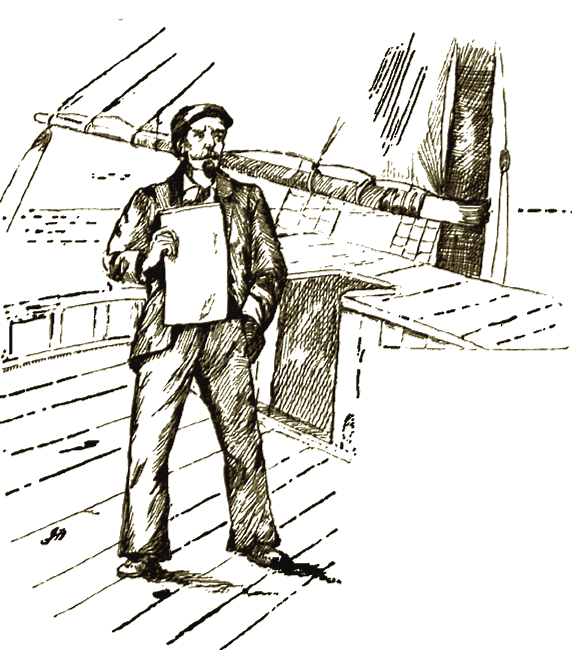

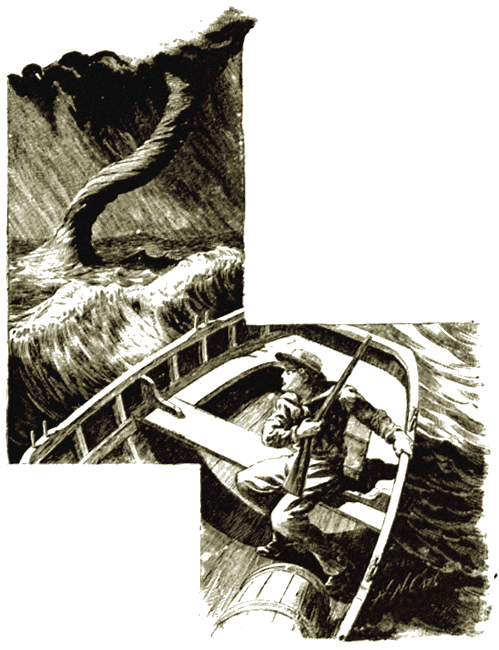

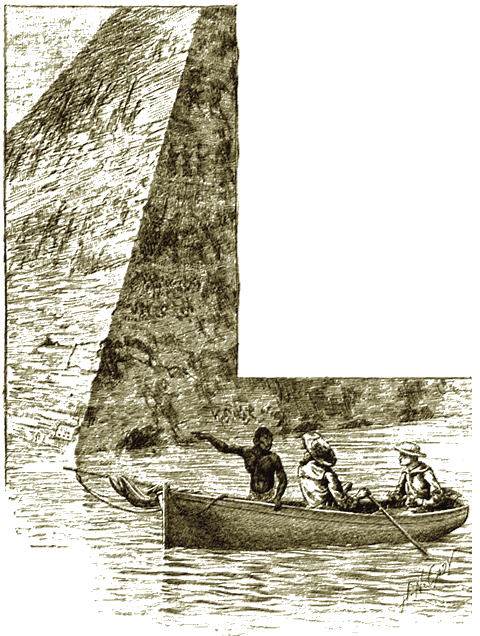

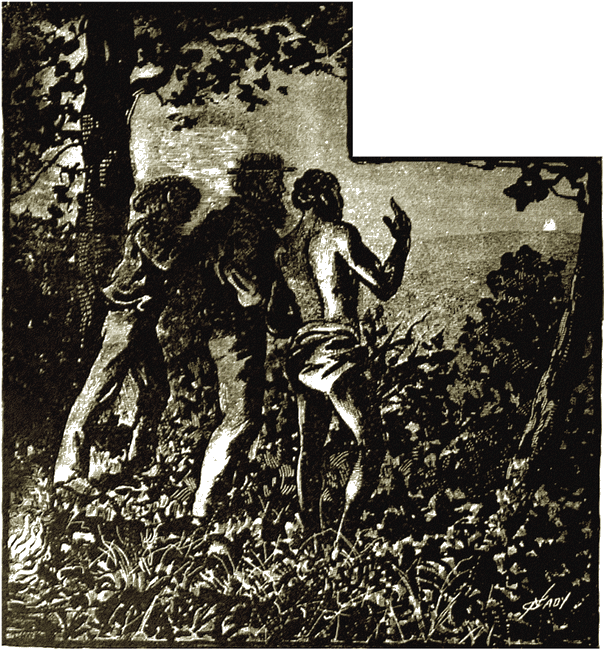

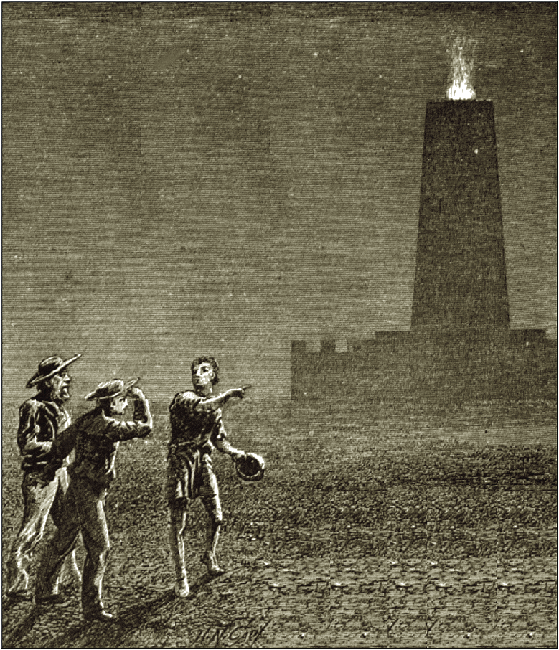

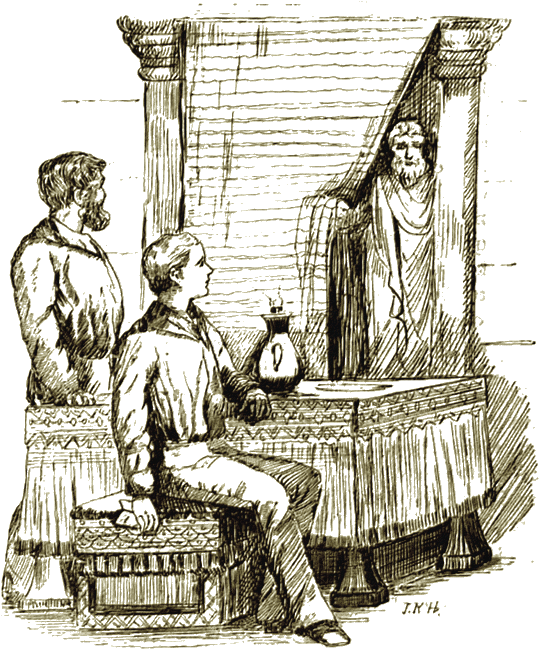

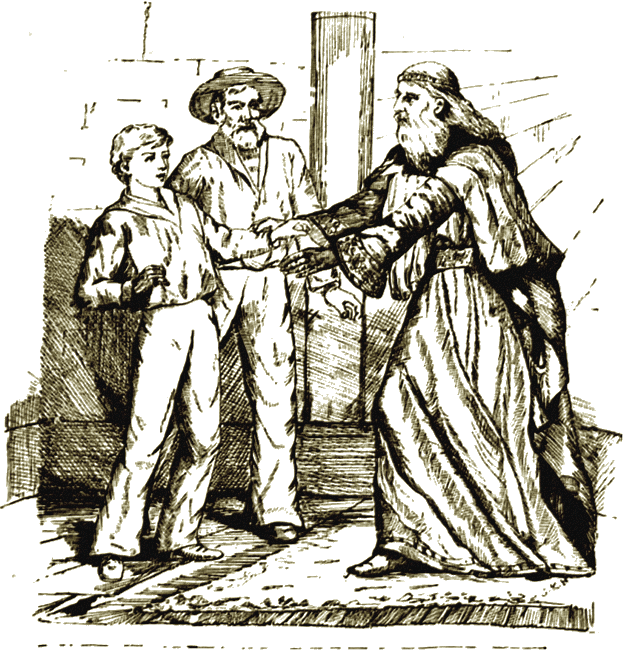

Frontispiece

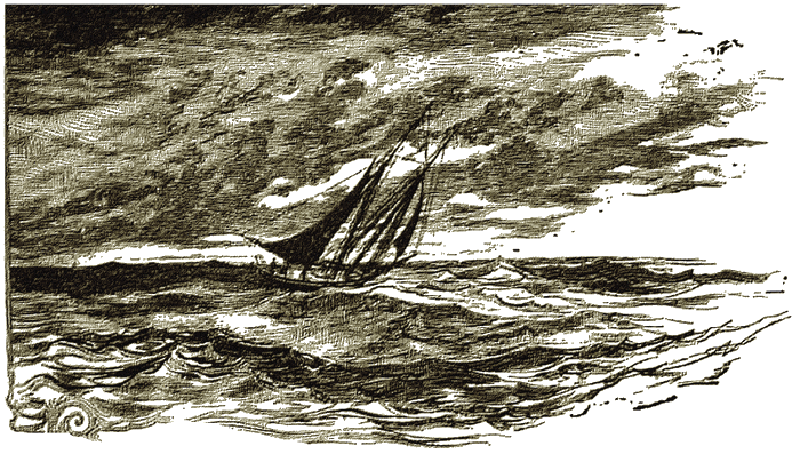

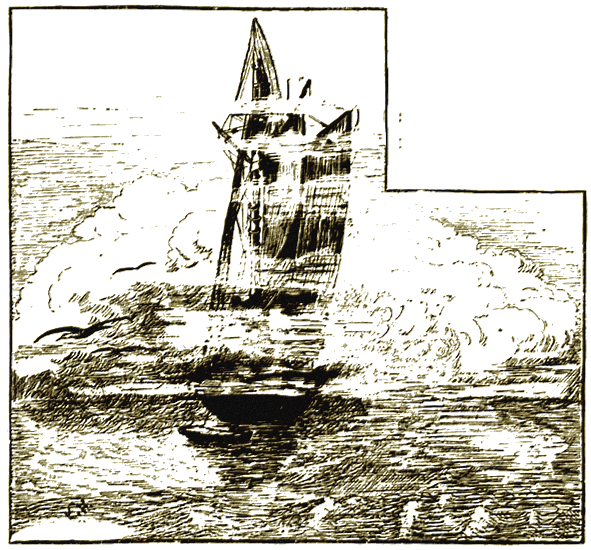

DAYLIGHT was breaking dimly through wild-looking clouds upon a world of tumultuous waters. One of those dangerous storms which, in the tropics, spring out of the heated regions of the air with sudden and devastating violence, had been raging all night. Toward morning the tornado had abated somewhat, but it was still blowing hard and the sea ran in short heavy swells, bursting into frothing ridges of snowy foam. Riding the waves with the lightness of a water-fowl, her tall spars bending gracefully to the sharper gusts of wind, a vessel under single-reefed mainsail and jib was beating slowly toward the northeast.

She was a handsome boat of four or five hundred tons, schooner-rigged, with slender masts and spars and a spread of canvas which would have served a still-water yacht. Indeed from the beauty of her lines, the plentiful display of brass-work in her fittings and her polished hard-wood rails, hatches and stanchions, it was evident that she had, in fact, been designed originally for a yacht. The purity of her decks and her general air of neatness and good order now, proved that if she were not still in use as a pleasure boat, she was at least engaged in some very light and cleanly trade. From certain signs about her a sailor would have declared that she was of American build and that she had been many weeks at sea.

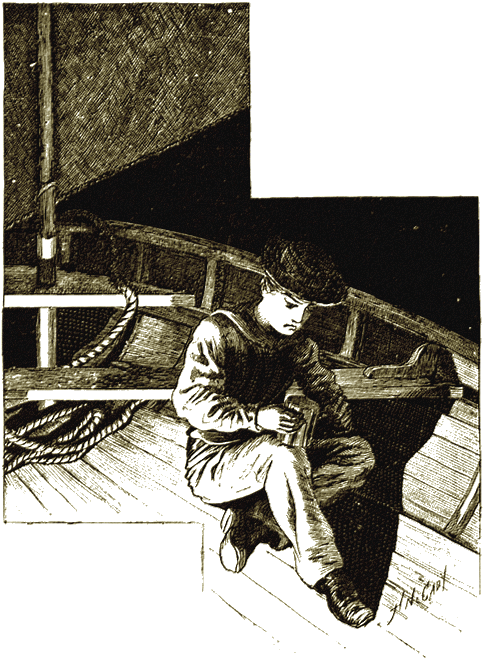

The crew, exhausted with their labors during the night, had gone below, and the watch on deck consisted of the man at the wheel and a boy of fifteen, who sat at a little distance, regarding his companion with an expression of anxious inquiry.

He was a handsome, manly-looking lad, with brown curling hair and bright gray eyes. Though his hands were soiled by labor and his clothing was poor and patched in a dozen places, he was plainly much above the class to which cabin-boys ordinarily belong. His face, bronzed and darkened by exposure to the weather, though frank and sincere, wore a thoughtful and troubled look not natural in one of his years.

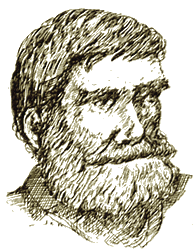

The man at the wheel was about fifty years of age, short of stature, but so powerfully built about the shoulders and back as to present an almost comical appearance, as he stood balancing himself to the swaying of the vessel upon a pair of legs, which for girth, at least, might have supported a sizable elephant "There is plenty of me," he was in the habit of remarking, "only I grew sidewise instead of up and down, d'ye see?"

His face was rugged and weather-beaten and looked more like a piece of rough red ox-leather than anything human. His eyes were small, keen and set deep among a net-work of wrinkles and creases, giving him an expression of perpetual good-humor and joviality. Good-humor was, in fact, his chief characteristic, though upon certain occasions he might manifest a decidedly combative disposition. Such occasions, however, were very rare, for he had an unlimited belief in his own muscular powers, and it was his firm conviction that he was more than a match for any three men living. Consequently he considered it both unfair and unmanly to notice provocations from individuals whom he could utterly demolish if he chose.

The baptismal name of this personage was Benjamin Barker, commonly abbreviated to Ben Bark. It was all the same to Ben. "Names don't signify," he observed philosophically, "calling a marlinespike a monkey won't make it climb a backstay. So what's the odds?"

At the present moment Ben's features had assumed an unnatural gravity. His huge hand, tattooed with certain nautical emblems, gripped the spokes of the wheel as if it would crush them to pieces, in the agitation of some unaccustomed emotion. From time to time he glanced mechanically at the compass before him, then his eve sought the boy's face again with a perplexed and troubled look.

There had been a long silence between the two, but the sailor at length, broke it by saying in an unsteady voice,

"So lad, you are bound to leave the ship, are you?"

"Yes," replied the boy, with a flush in his brown cheek. "I have borne all I can bear. I will submit to the captain's abuse and ill-treatment no longer. He is my relative, but if I were a vagabond whom he had picked up out of the gutter he could not use me more shamefully."

"Will you desert, lad?" asked Ben.

"Yes," answered the boy, "and you will help me, Ben."

"I don't know about that, Rollin," replied Ben, shaking his head gravely, "desertion is agin all seamanship and mostly is a sneaking business. I did so hope you were going to stick by the ship and make a man of yourself, instead of going back ashore and degrading yourself into a common landsman."

"But what can I do, Ben? You see my position here."

"I don't blame you, boy, no I don't. You have had hard usage, that's a fact."

"And you will help me to get away, Ben?" asked the boy eagerly.

The sailor looked down at him a moment without replying, his rough features expressive of deep feeling.

"I'm a fool, a regular marine!" he ejaculated at length. "But d'ye see, lad, when a man takes a liking at my age it's a hard matter to beat agin it and face the situation in a sensible and seaman-like fashion.

"What is it, Ben?" enquired Rollin, arising and laying his hand affectionately upon Ben's broad shoulder. "What have I said to hurt your feelings?"

"No, lad, no," said Ben, shaking his head, "it's human natur' that's to blame, d'ye see? Man and boy, I've sailed the sea thirty-five years, never coming to anchor for any length of time and consequently never forming no family ties. But it's human natur' to form ties of one sort or another, and when a man gets to my age he grows hungry-like for something or somebody to look after and take care on. When you came aboard, lad, I was just in that state that I took to ye powerful, and I did hope we might sail in company for the rest of my voyage of life."

Much affected by his rough friend's emotion, the boy remained silent and Ben continued,

"But, as I said afore, I'm an old marine. A gentleman's son like you, can't mess with a common 'fore-master like me and I should have known better. But it goes right hard with me to think of losing you."

"I am glad to hear you talk so, Ben," cried the boy, seizing one of his friend's great hands and pressing it warmly. "But I must desert, Ben, or I shall go mad."

"Shall I pitch into him, yonder?" asked Ben, nodding his head mysteriously toward the cabin hatchway. "I know it's downright mutiny, but I'll do it if you say so."

"No, no, Ben," answered Rollin quickly, "it would only make matters worse. He would put you in irons and abuse me more shamefully than ever. No, help me to get away quietly. It is all I ask or desire."

Ben Bark fixed his eyes mournfully upon the compass and remained silent.

"Ben," said the boy suddenly, "where are we now?"

The sailor raised his head and gazed thoughtfully over the wide expanse of tossing water.

"Last night at sunset we were less than fifty miles off the west coast of Australia. The gale blew from the southward all night and shifted round to the eastward at daybreak. As near as I can guess, we can't be far from Cape Leveque, at the mouth of the Darke river."

"Ben," said the boy again, with an earnest look, "were we not almost in this very spot six months ago?"

"Aye, lad," responded the sailor, returning his look.

"And have we not been in this neighborhood three times before, while I have been aboard the ship?"

"Mayhap, lad, mayhap," answered Ben slowly.

Rollin remained silent, with his chin supported upon his hand, for some minutes.

"Is there any large town upon this coast, Ben?"

"I never heard of any, boy."

"And there is nothing but swamp and desert and uninhabited country along the whole west coast, eh Ben? No port at which a vessel could take in or deliver a cargo?"

"Not unless it was to trade with naked savages for a cargo of crabs and mud-fish," was the reply.

"Then why are we here?" persisted the boy.

"Why," said Ben, avoiding the boy's eye, "seeing that the captain laid the course and the crew obeyed orders, it is quite natural that the ship should be where she is."

"You are joking, Ben," responded the boy reproachfully. "Is it not true that there is no town along this whole coast and no apparent reason why a ship should ever come here? Is it not true that we have spent the best part of this voyage cruising in these waters, never landing except at some uninhabited island? And at such times does not my cousin always go ashore alone and spend hours away from the ship by himself, returning more gloomy and silent than ever? Is it not true that while we are in these waters he is more abusive and savage toward me than at other times? Is not all this true, Ben? Answer me."

"Well," said Ben reluctantly, "if I was put upon oath, lad, I should have to say that you are about right."

There was a long silence between the friends, each seeming to be occupied with painful thoughts.

"Ben," said the boy at length, "was it not somewhere on this coast that my father was lost?"

The sailor started and glanced about him apprehensively. Before he could reply a stern voice from the companionway put an end to the conversation.

"Aft there! Send that shirking boy forward, Ben Bark, and mind your eye with that wheel. The sails are shaking now."

"Another time, Ben," whispered the boy, as he turned to obey the harsh summons. "You are on the middle watch to-night. I will try and steal out and come to you. Meanwhile not a word of my plans."

"Mum as a barnacle," replied Ben, in the same tone. "Poor lad, poor lad!" he muttered, as he watched the boy's retreating figure. "Strange things come to pass in this world. Here we are on the very spot where it happened, with his son on board. Is there a fate in it, I wonder?"

TO judge from his manner and look, Captain Chadwick was not in the most amiable frame of mind possible. He had come on deck during the conversation recorded in the last chapter, holding a sea-chart in his hand. His eye wandered from the chart to the stretch of heaving water eastward, then to the spars of his vessel, and a heavy frown settled upon his features.

Captain Chadwick was not an ill-looking man, as far as face and form went, being of medium height, with broad shoulders and active though not powerful frame. His hair was short, slightly grizzled and curly. His face was clean-shaven, with the exception of a moustache which shaded a stern, firm set mouth. His eyes were black and piercing as a hawk's, with an expression hard to describe, but producing an unpleasant effect upon the beholder. Altogether he was a man one would be likely to distrust and avoid, without exactly knowing why.

He continued to examine the chart and the ocean at intervals, for some moments, his face growing darker with each glance. Although the Swallow had weathered the storm without the slightest damage and was then sailing upon a safe course, with plenty of sea-room, the captain seemed savagely displeased with the state of affairs generally.

Detecting Rollin in conversation with Ben Bark at this moment, his frown grew even blacker, if possible, as he gazed at the boy. Calling him forward in an angry tone, he ordered him to go below and summon the first mate upon deck.

That officer appeared promptly.

"Good-morning, Mr. Tobias," said the captain, abruptly. "What do you think of the weather?"

Mr. Tobias glanced aloft at the spars, then at the water and replied,

"Why, sir, it is as favorable as can be. The storm has blown itself out and the ship is as sound as a nut."

"Will the wind hold in this quarter, think you?" asked the captain in the same abrupt tone.

"To my mind it has a flavor of south in it, sir," responded the mate. "The wind seldom holds long at east in these latitudes."

"Then we are likely to sight land before dark?"

"We ought to make land from the mast-head before sunset," replied Mr. Tobias.

"What part of the coast should we make on this course?" enquired the captain.

"To my mind it will be one of the Buccaneer islands, sir, somewhere off the mouth of the Darke River."

The captain walked away a few steps, with his head bent thoughtfully and returned again. Presently he addressed his subordinate again.

"We will hold on until we are within three miles of the shore and drop anchor for the night. I shall land in the morning, alone. You will see that no other person aboard this ship holds any communication with the shore while we are in this neighborhood."

The mate looked at his superior with some surprise, but interposed no objection.

"Very well, sir," he responded gravely. "Your orders shall be obeyed."

"The wind is shifting already, Mr. Tobias," said the captain, as the breeze, which had been blowing steadily, changed to irregular puffs and the water assumed a more broken and disturbed appearance, "shake out the reefs and get more sail on the ship."

The mate retired and the captain continued to pace the deck, with contracted brows and downcast eyes.

His meditations were interrupted by a light step behind him, and turning about, he saw Rollin standing beside him.

"What do you want?" he said harshly.

"Mr. Tobias reports that your directions have been obeyed," answered the boy. "He asked me to speak to you as I passed."

"Very well," responded the captain, "now get below and help the cook clean the ship's coppers."

Rollin's cheek reddened. After a moment of hesitation, he said,

"Are you sure you really mean that, cousin?"

"What is that?" asked Chadwick, sharply. "What are you talking about?"

"I wanted to give you a chance to remember, cousin," answered the boy quietly, "that I did not come on board the Swallow to do such work as that."

"Pray, what did you do me the honor of coming for, then?" retorted Chadwick, sarcastically. "Perhaps a suit of broad-cloth and a seat at my table would be more to your taste."

"It would certainly show better taste on your part," answered Rollin, "and it would certainly be nearer to your promises."

"Do you offer insolence to me, you young vagabond?" said Chadwick, angrily.

"I don't mean to be insolent, cousin," answered the boy, "and I am no vagabond. If I am poor, ragged and dirty, the fault is not mine but yours."

"That will do," said his cousin, coldly, "I wish to hear no more. Go below and attend to your work.

"But I have something more which I wish to say," responded Rollin, without moving. "When you sent for me and offered to take me to sea with you, you told me that my duties would be light and that I should be taught navigation and fitted to become an officer. How have you kept your word with me, cousin?"

His relative looked at him with lowering eves, seeming astonished as well as enraged at the boy's boldness.

"If you imagined that you were to live in idleness at my expense," he said, "you were greatly mistaken. I allow no drones aboard my ship."

"I am not a drone, cousin, as you well know," replied Rollin. "I am willing to work; I do work far beyond my strength. And what do I get in return? Ill-usage, poor food, and rags."

"You would have been starving or stealing, if I had not picked you up out of charity," answered the captain harshly. "Instead of being grateful you are impertinent, you young beggar."

"Grateful!" repeated the boy, "for what? for being treated like a drudge on a ship that was once my father's?"

"The less you say about that the better," said the captain, with a dark look. "I should have thought that you would not be very anxious to call your father to mind."

"You, of all persons in the world, should say least against my father," retorted Rollin indignantly, "for you alone have benefited by his disgrace and death."

"What do you mean to insinuate, you young scoundrel?" cried Chadwick, white with rage.

"I mean that I am convinced that if justice were done, my father's name would not have been dishonored and you would not now have it in your power to abuse his son."

"Why do you suspect me?" asked Chadwick, glancing about him anxiously and speaking in a lower tone. "What was there in my actions to justify suspicion?"

"Time will show," answered Rollin. "When you returned from that last voyage, you told us the story of my father's disgrace and death and you showed us papers which gave you the right to all of his property. But child as I was, I did not believe your story. I do not believe it to-day."

"And you do me the honor to believe that I was in some way responsible for your father's mishap—no, give it its true name—his crime?" Chadwick spoke quietly, but there was a dangerous gleam in his eyes.

"At all events," responded the boy, "I am convinced that sooner or later I shall know the truth. And," he added, looking steadily at his relative, "I am convinced that it will be a bad day for you, cousin, when the truth is known."

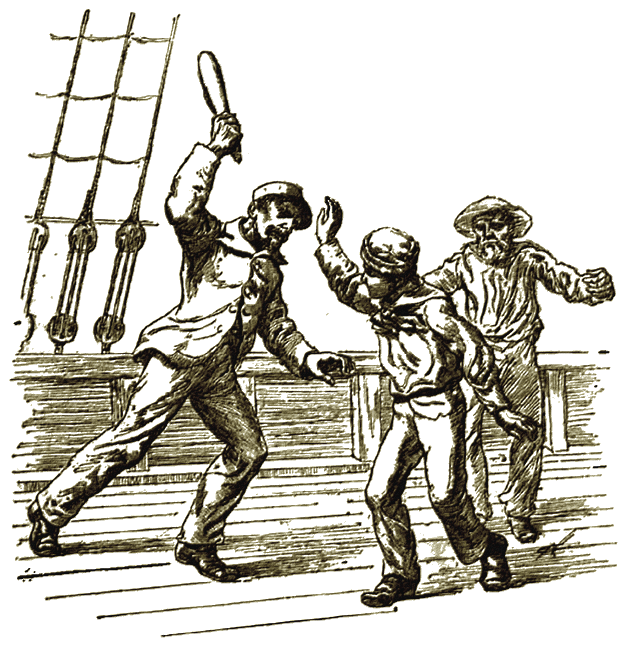

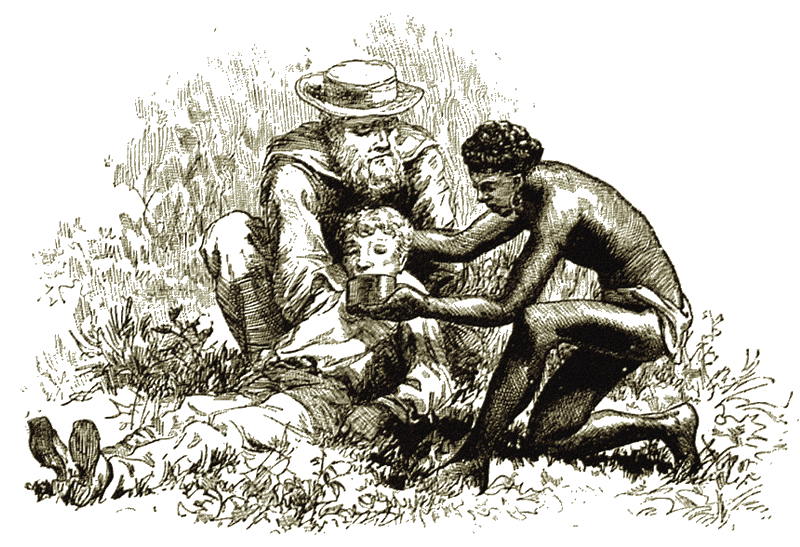

Chadwick was silent He was deadly pale and his features were frightfully distorted. Casting a furtive glance around, he suddenly seized a hand-spike lying upon the deck, and before the boy could divine his intention, struck him a powerful blow upon the head.

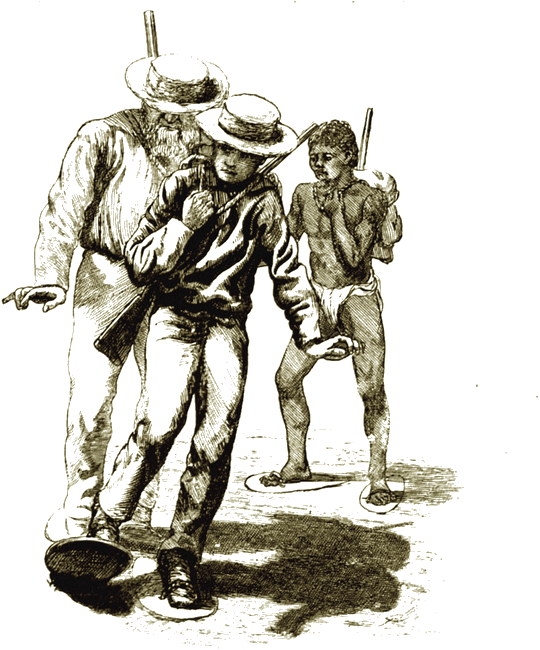

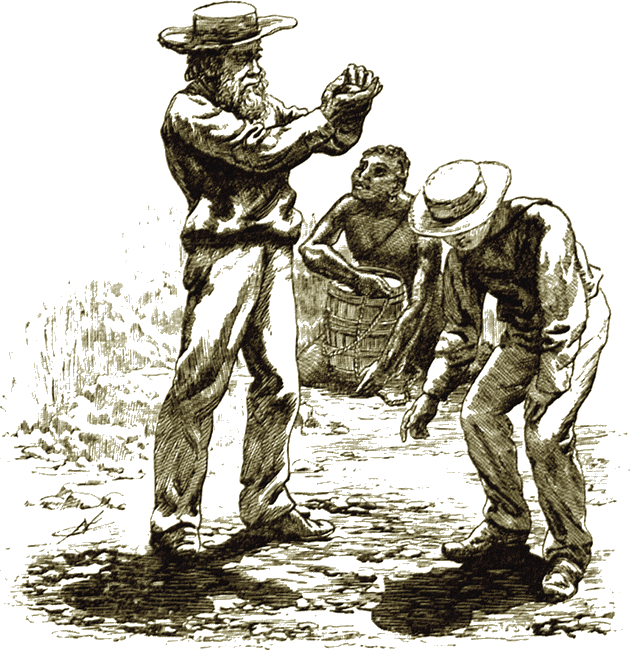

Fortunately for Rollin, his thick sea-cap deadened the force of the blow and the heavy instrument merely cut the skin upon his forehead. Apparently maddened by his own act, Chadwick was about to repeat the blow with better aim, when the hand-spike was suddenly wrenched from his hand behind and Ben Bark's deep voice said quietly,

"No, no, captain; think better of it. Remember the little chap can't stand the battering that tough old timbers like yours and mine can bear. I'm sure, now, if you think it over, you'll take a sort of more sensible view of it, d'ye see?"

Chadwick turned with a furious ejaculation, and struck Ben a heavy blow with his clenched fist. Ben merely shook his head, without offering to return it.

"Well, well, Captain," he remarked, without the smallest trace of anger, "if you must open fire on somebody, better on me than on the little chap. Because I can stand it, d'ye see? I know my duty, Captain, and though as ready at a scrimmage as most men when its equal and fair, I hold it to be unseamanlike to strike my superior officer. So if you will let the boy go, you may take it out of old Ben and welcome."

"If he dares stir a foot until I order him to go," shouted the infuriated Chadwick, "I will brain him on the spot."

"Well, well," said Ben, with a sigh, "I s'pose there must be exceptions to all rules. I did think to sail out my voyage in this here life, without disobeying orders, or treating my commander with disrespect. But circumstances alters cases. So here goes."

So saying, the sailor threw his powerful arms round Chadwick and, despite his struggles, held him helpless as an infant.

"Now, lad, go below as fast as you can," he said, "and stay out of the way till the captain has had time to reflect. As I said afore, when he comes to himself, he will see the philosophy of what I have been telling him."

The crew, attracted by the scuffle, had gathered from all parts of the vessel and now stood looking on the strange scene with wonder.

"Mutiny!" shouted Chadwick, "will you stand by and see me assaulted? Lend a hand here, will you?"

"Yes," said Ben, shaking his head, "I suppose that's what it is, just mutiny and nothing less. But it was the choice of two evils, d'ye see, mates? Ben must draw the enemy's fire, or the little chap's hold be stove in. Now, then," he added, seeing that Rollin had disappeared, "I'll take the stoppers off the captain's arms."

"Put him in irons," commanded Chadwick in a low, hoarse tone, when he was free again.

"I'm agreeable," said Ben. "Irons is according to rules and regulations made on purpose for such like cases. So bring along your bracelets and lay old Ben Bark by the heels."

The manacles were put upon the sailor and escorted by the mate and carpenter, Ben went cheerfully below, while Chadwick continued to pace the deck with a face more dark and threatening than ever.

THE Swallow, under easy sail, ran smoothly and rapidly before a brisk, southwest wind. At two o'clock land was sighted ahead, and before sunset the coast, which proved to be a low barren island, was not more than six miles distant.

After examining it long and attentively through the glass, the captain ordered the course of the vessel to be changed a couple of points, and as the wind had become lighter, more sail was set.

The Swallow was now in the broad bay, into which the Darke River empties, known as King's Sound. The island was soon left on the larboard quarter; at sunset the schooner was hove to at a safe distance from the land, and the captain announced his intention of going ashore in the morning.

Meanwhile he seemed to have forgotten both Rollin and Ben Bark, together with the disgraceful scene of the morning. Rollin had continued to perform his duties, without crossing his cousin's path; and as for Ben, lodged in a dark corner of the hold, with irons upon his limbs, he was not in a position to give the captain much trouble.

Most persons in Ben's situation would have employed themselves either in bemoaning their fate, or pondering schemes of vengeance. Ben did neither. His good humor was inexhaustible.

His mind, however, was not altogether at ease. He considered that he had done his duty in protecting Rollin, but he also admitted that in laying hands upon his superior officer he had been guilty of a serious breach of discipline.

He interrupted his reflections to search in his pocket for his plug of tobacco. By reason of his irons, this was a matter of considerable difficulty. By dint of hitching and straining, however, he at length accomplished his object, and, rolling his quid luxuriously into his cheek, he continued, half aloud,

"This little chap, what I have took to so powerful, is a puzzler. If he deserts on this coast, the savages or the fever or starvation will do for him. If he stays aboard, who's to say that the captain won't serve him as he served his—Avast there, Ben Bark! Put a stopper on that jaw of yours, will you? unless you want to perwide a meal of wittels for the sharks afore your natural time. Well, well Ben, the best you can do is to see what turns up and make the most of it."

Having reached this satisfactory conclusion, Ben's mind seemed greatly relieved. Making himself as comfortable as possible in his narrow quarters, he deliberately went to sleep. It will be seen by this that Ben was a practical philosopher, possessing that most admirable of faculties, the ability to make the best of a bad job.

The hours passed slowly away. The groaning of the ship's timbers and the creaking of the spars, were sounds too familiar to the sailor's ear to disturb his slumbers.

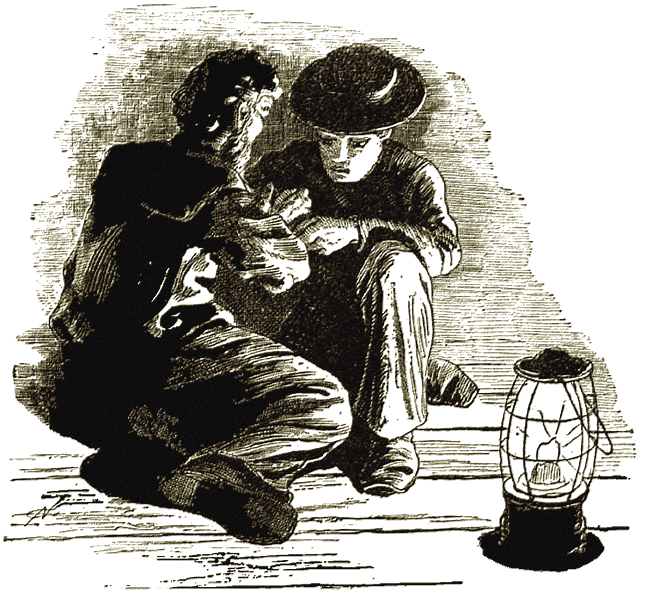

He was awakened at length, however, by a low knock upon the bulkhead near him.

"Who's there?" he called.

"Hush! it is I, Ben," answered a voice, which he recognized as Rollins. "Don't speak until I get in where you are. I have found a hole in the partition and I am making my way through."

Ben waited in silence, until he felt the boy's hand upon his shoulder.

"I am afraid you will be found out and punished for coming here," whispered the sailor.

"No fear of that," replied Rollin. "It is near midnight and the captain is in his cabin. I have brought a lantern, which I am going to light, and better than that, I have found the carpenter's keys and I am going to take off your irons."

In another moment the smoky glare of the lantern illuminated Ben's prison. Selecting the proper key, Rollin unlocked Ben's manacles and threw them aside.

"Now," said he, silting down beside his friend, "let us talk. First of all, how can I thank you for what you have suffered on my account?"

"By just saying nothing at all about it," was the sailor's reply.

"Ben," said the boy abruptly, "I am going to leave the Swallow to-night. Will you help me?"

"Have you thought it over, careful like?" asked Ben, seriously. "Do you know that if you leave the ship here you will be alone in a wild country, more than a thousand miles from any white settlement?"

"So much the better," answered Rollin quietly. "It is just here, on this part of the Australian coast, that I wish to be. If I had not come here in the Swallow, I should have found some other way. Ben," added the boy, laying his hand upon his friend's arm, "you were one of the Swallow's crew when my father was her owner?"

Ben assented silently, with an uneasy look at the boy's face.

"Ben," said the boy again, after a pause, "are there any people in the slave-trade now-a-days?"

"Yes," he replied, with the same uneasy look. "Some Arabs and Malays run slavers on the coast of Africa, and among the islands still. It is a dangerous trade and means hanging if caught."

"Are there any white men in the trade, Ben?"

"Some few Portuguese," was Ben's reply, "if you can call such yellow varmints white men."

"Ben," said Rollin in an almost inaudible voice, "my father was accused of being a slave-trader."

Ben bowed his head, without replying.

"But you do not believe it, do you, Ben? You knew my father. He was a good and honorable man. Tell me, Ben, that you do not believe it."

The boy spoke in a low, trembling tone, and there was an expression of deep trouble in his young face.

"No," replied the sailor solemnly. "I do not believe it, lad; for it is a lie, a cruel, cowardly lie that will look black agin' the names of them that invented it, on the great day of reckoning, when all log-books are overhauled by the Captain up aloft."

"Ben," said the boy, grasping his friends huge hand, "I am going to try and clear away the disgrace upon my father's name. I am only a boy, I know, but it is a good cause and I shall succeed, I know I shall. Will you help me?"

"Best let it be, lad," responded the sailor gravely. "It's a dangerous business."

"I know what I have to expect." replied the boy firmly, "my mind is made up. If you will help me, I shall be grateful all my life. If not, I must do my work alone."

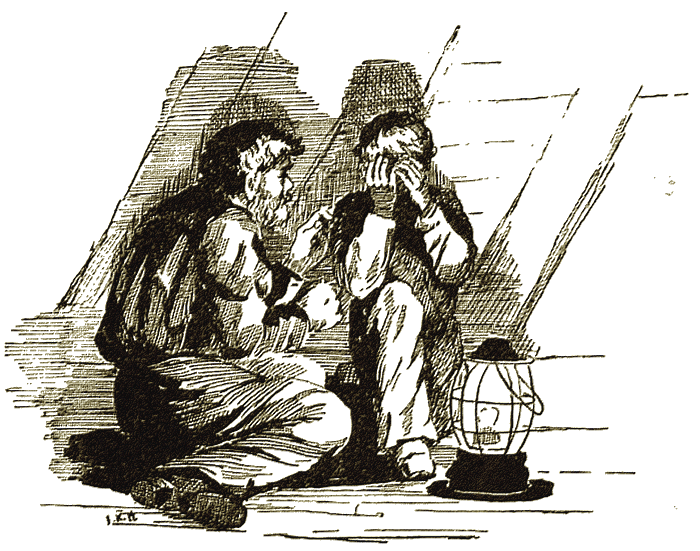

The sailor made no reply for some time, but sat with his eyes cast down as if in deep thought.

"Rollin," said he, presently, "I had meant to carry my thoughts and suspicions with me to the grave. But since you have come aboard, my mind has been troubled with many misgivings as to what my duty calls upon me to do. If there had been any real proof, it would have been another matter. But it's like sailing in the dark in unknown waters. You can neither shake out your reefs not let go your anchor. However, I will tell you what I know and mayhap your young eyes can see light where old Ben's are pretty much blind."

Rollin listened breathlessly, while the old seaman spoke, bending his head closer to him so as not to lose a word.

"I was one of the Swallow's crew," continued Ben, "when your father made his last voyage in her. She was not a regular trading vessel, but what she was cruising for in these waters, no one knew besides your father. He never opened his mouth, unless it may have been to his first mate, Chadwick. Whatever it was, he was very earnest about it. He was always looking into bays and rivers hereabouts and making long journeys inland. He had learned the native lingo, and would invite crowds of the black fellows aboard to talk with them."

"On that same last voyage," continued Ben, "I fell through a hatch and broke a leg, and was laid by the heels in my hammock for the rest of the cruise. After a while, as I lay there, it began to grow upon me as how there was something wrong going on aboard the ship. What it was I could not guess, but whatever it might be, I was sure that Chadwick was at the bottom of it."

"Yes, yes," murmured Rollin, "I knew it."

"He was very thick with two of the crew, hard-looking, hung-dog fellows as ever I set eyes on. My hammock had been slung outside of the mess-room, between decks. Often when the rest of the crew were above, Chadwick and his two cronies would slip into the mess-room and hold long talks together. There was a plank partition between us and they always spoke cautious, but now and then I caught a word which set me thinking."

"One night," continued Ben, glancing about him uneasily, "as I lay turning my doubts and forebodings over in my mind, I heard the sound of voices in the cabin, followed by the scuffling of feet on the deck overhead. The men were all asleep below, except the watch, which, as I called to mind, was them same two hard-looking friends of Chadwick. The trampling of feet seemed to move across the deck toward the starboard quarter. Then there was a creaking of blocks as if a boat were being lowered. A horrible suspicion made my hair stand up and my flesh creep."

The boy's hand, which held the sailors, tightened its grasp, and for a moment the two friends sat looking at each other with pale faces.

"Forgetting all about my leg," said Ben, after a pause, "I started to get out of my hammock. The bone had just begun to set and it gave way beneath me. I fell back in a faint and for many a long day I was out of my head with the fever that followed. When I came to myself again I was told your father—There, lad, there! Don't take on so, that's a good lad.

Overcome by the emotions excited by the sailor's story, Rollin had covered his face with his hands and was trembling violently with grief and horror.

"Go on, Ben," he said, at length, raising his head and brushing the tears from his eyes. "Tell me all. I can bear it

"There is but little more to be told, lad, replied Ben. Your father disappeared without leaving a trace behind him. Chadwick's two friends talked around among the crew that your father had intended to turn the Swallow into a slaver and run a cargo of black fellows to the African coast. He had tried to get Chadwick to go into the scheme with him, they said, but he had not only set his face agin' it, but had threatened to stir up the crew and deliver him up at the nearest civilized port. That frightened your father and that same night, in fear of the consequences, he jumped overboard and drowned himself."

Rollin drew his breath hard between his set teeth.

"Oh my poor father! he muttered.

"Whether the men believed the story or not, they had the good sense to keep mum. When we reached Cape Town the crew was paid off and discharged. Chadwick's two friends went up into the country and bought sheep-walks, which, considering that there was only about sixty dollars apiece in wages justly due them, I take to be a suspicious circumstance."

"I see," said Rollin, bitterly, "they were well paid for putting my father out of the way."

"Just so," assented Ben. "As for me, I stayed with the Swallow. The ship was like home to me and I could not bear to quit her. It was borne in upon me, likeways, that I must stay, I don't know how. Perhaps there was a fate in it. At all events I stayed and here I am. Now, lad, you know all that old Ben knows."

There was a long silence between the friends. The boy sat with his head resting upon his hand, while the old seaman looked at him with a strange mixture of affection, perplexity and trouble in his rugged features.

"Ben," said Rollin, raising his eyes at length, "do you believe that my father was—?"

He paused with a shudder.

"Made away with?" answered Ben, "not a doubt of it."

"And what was Chadwick's object?"

"Why, did you not say that he got hold of your father's property? Ain't that object enough? Ain't all the black deeds that men do, for the sake of money?

"That was not his original object," replied Rollin, quietly, "He had another and a more important one.

"Aye, lad?" said the sailor, in surprise. "How do you make that out?

"And he failed, said the boy.

"Did he, lad?" responded Ben, in still deeper perplexity. "Well, mayhap. But you have outsailed me now. I haven't an idea of what you are driving at."

"Ben," said Rollin, with a suddenness that caused the sailor to start, "what is Oo?

"Oo," repeated the sailor, with a puzzled air, "now lookee, lad, if it comes to the rigging of a ship, or a general notion of navigation, I might tell you the difference betwixt bolt-rope and a back-stay, or sailing close-hauled and going free, but when it comes to Latin or Hebrew or any of them foreign languages, you might as well ask the figure-head of this ship as Ben Bark.

"It is not Latin," answered Rollin gravely, "nor any language that I have ever seen in books. But I want to know what Oo means? I must know! If it is a place, I must go to it."

The sailor sat gazing at his young friend, as if he were not quite certain that he had not lost his senses.

"Look," said the boy, drawing a small tin case from his breast pocket, I have found something which puzzles and frightens me, because it seems so strange and yet seems to mean so much. I am sure that when I understand it I shall know what this mysterious Oo is. And Ben, he added solemnly, "when I know what Oo is, I shall know what became of my father. See!"

And opening the case, he displayed a singular object before the astonished eyes of the sailor.

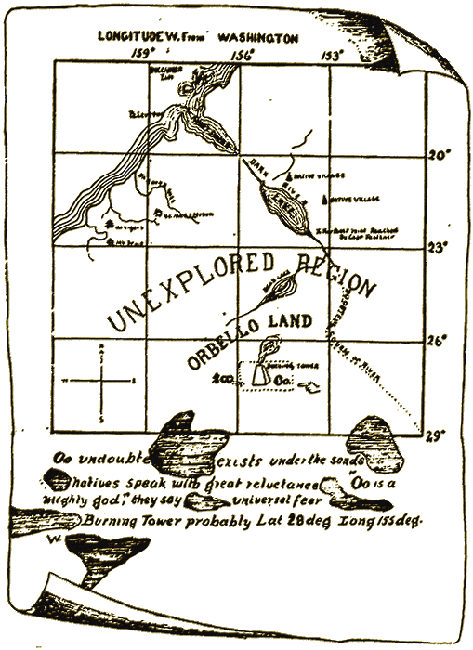

THE object which Rollin exhibited to his bewildered friend was a small piece of the bark of some tree, flexible as cloth and of a yellowish white color. It was stained in places, and with the battered tin case which had contained it, showed signs of hard usage.

The boy spread it out carefully upon his knee and by the light of the smoky lantern, the old sailor saw that it was a kind of rude map or chart, with some lines of indistinct writing beneath it. It was roughly drawn and the ink which had been used, to all appearance the juice of some wild berry, was much faded.

With their heads close together and scarcely breathing in the intensity of their interest, the two friends bent over it in silence a long time.

"Well," said Ben at last, with a deep sigh, "I have seen a many charts in my time, but I never run foul of anything like this here. I make neither head nor tail of it Do you, lad?

"Only a very little," replied the boy, "but enough, as I told you, to satisfy me that it has something to do with the mystery of my father's fate."

Ben glanced from the chart to the boy's face, with an air of great perplexity, but said nothing.

"Ben," said Rollin, laying his trembling hand upon his friend's arm, "since I have had that piece of bark I have come to believe a strange thing. It is that my father is not dead."

"Not dead!" echoed the sailor, aghast, "what do you mean?

"Listen, Ben," continued Rollin. "What you have told me just now about my father makes me still more certain that I am right. You told me that my father made many voyages in the Swallow on this coast, never stopping at any port or taking any cargo. Is that true, Ben?

"Exactly," replied Ben, "just so, lad."

"He made long journeys into the country and never told any one where he went or what he went for. Every one on board the Swallow knew that he had some object in which he was greatly interested, but he never revealed it Is that true, Ben?

"Exactly," replied the sailor, as before, "just so."

"On that last voyage you suspected that my Cousin Chadwick had some bad design against my father. You believe that he and his two ruffians took my father away in the boat by force that night, and did something with him, accounting for his disappearance by the wicked story of the slave-trade. This is true, too, is it not, Ben?"

"Word for word," answered Ben, "couldn't be truer, lad."

"Where was the Swallow on that night, Ben?"

"Hove to off a little island in King's Sound, near the mouth of Darke River."

"About six miles from the mainland, which runs out in a long point, and is hilly and covered with trees?"

"Aye, aye," replied Ben, "I know the spot well."

"We passed that island to-day," said the boy, "and we are now hove to off the wooded point. When we passed the island I saw Captain Chadwick examining it with the telescope. Do you know why he did that, Ben?"

The sailor shook his head.

"Because he thought it possible my father might be still there.

"Still there!" said the sailor with a gasp.

"Yes, Ben," replied Rollin. "Chadwick and his two men look my poor father to that island in the boat that night and left him there. Alone on that barren place, six miles from the mainland and many hundred miles from any town, was he not as completely out of the way as if he were dead?"

"True, lad, true," muttered the sailor, thoughtfully. "I believe you are right."

"It was not my fathers property which he was after, at that time," continued the boy, "though he took that later on, when his real object was baffled. Do you know what that object was, Ben?"

The sailor shook his head.

"It was Oo," said Rollin, laying his finger on the chart.

"It was Oo," repeated Ben, mechanically.

"My father had discovered something about this Oo which made him very anxious to go to it. Chadwick found out my father's plans and resolved to turn them to his own benefit. But my father had some clue or secret about this Oo which Chadwick has failed to obtain, so that his crime has done him no good."

The sailor gazed at his young friend, with admiration and astonishment depicted in his rugged features.

"Think of that, now," he said. "Well, I always said you had the making of something great in that little head of yours."

"But Oo must be something very wonderful," added Rollin, smiling affectionately at the old sailor, "for Chadwick is still determined to find it. That is why he continues to cruise on this coast and make journeys inland, as my father did. Like me, he is not sure that my father may not have escaped from the island and be still alive. So he is always nervous and frightened. This, perhaps, accounts for his ill-nature to me, which is always worst when we are on this coast, as you have noticed, Ben."

"Remorse, lad," responded the sailor, sententiously.

"That clue or secret," said Rollin, "which Chadwick committed a crime to obtain, I found by chance one day while I was cleaning the cabin, behind a book-shelf. It is this very map, Ben."

"I always said there was a fate in it," replied Ben, solemnly.

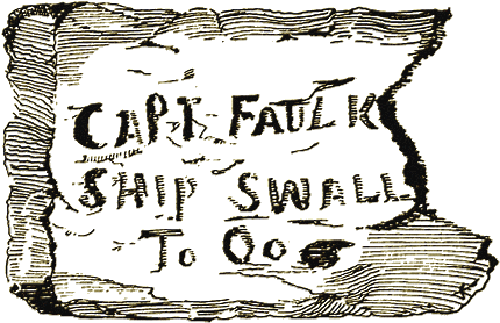

"This map was drawn by my father while he was on one of his expeditions into the country. See, he says here—'Farthest point reached by Capt. Faulkner.' And here upon the back," said Rollin, turning the piece of bark over and pointing to some almost illegible lines of writing upon it, "he says, 'Another failure. Reached this place with incredible hardship. Food exhausted, everything stolen by the natives. I must again return to the ship without success.' Here under the map he says, 'Oo undoubtedly exists.' But what is 'Oo,' Ben? Is it a town, do you think?"

"Why, that can't be, for he says there, 'Under the sands'," answered Ben, slowly spelling out the words. "And there again, 'Oo is a mighty god,' meaning that the black heathens say that much, which just goes for nothing at all, seeing that they lie by nature."

"And what does he mean by the 'Burning Tower,' Ben? See, here is a picture of it, and beside it the word 'Oo,' in a dotted square.

"He gives the latitude and longitude of that there Burning Tower, whatever it may be," said Ben, "and since Oo, whatever that may be, is near it, you have the position marked out all ship-shape, latitude 27 degrees south, longitude 154 degrees west.

"And here is another strange thing," responded Rollin, pointing to a curious sign in the square adjoining that which contained Oo and the Burning Tower. "What do you make of it?

"It looks like some insect or varmint without legs," was Ben's perplexed answer. "But it can't be that.

"No," replied the boy, "for there is something like the mark which stands for dollars beside it. There is a mathematical sign, which we used in school, made by placing two circles or zeros side by side and touching each other. It represented infinity."

"So you make it out to mean an infinity of dollars? said the sailor, studying the symbol with renewed curiosity.

"Something like that, at least. A great quantity of money, or the place where it may be found. Perhaps a rich mine. Yes, that would account for Chadwick's persistent attempts to reach Oo, which you see is near it.

"Right, lad. Such a man would sell his head for money. His soul he can't sell, that having been mortgaged long ago to some one we are not called upon to mention, d'ye see?"

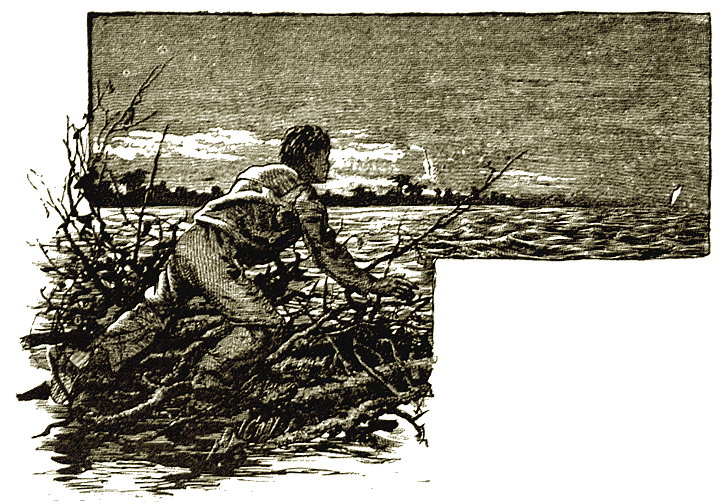

"Ben," said the boy, emphatically, arising and putting the chart carefully in his breast-pocket, "my father was a very strong man and very learned. He was not the person to stay upon that barren island and die there. He found means to reach the mainland."

"But if he is alive, lad, where is he now? asked Ben, anxiously.

"He is at Oo, Ben," was the prompt reply. "I am going there to find him. Will you go with me?"

The old seaman was silent for a moment, evidently in deep and uneasy thought.

"It's desertion, flat desertion," he muttered at length, "unseamanlike and agin' your principles, Ben Bark, as you have always stood up for. Deserting your ship is like going back on your word, and that is lubber's work." He scratched his head nervously. "But there, agin', is this little chap what I have took to so powerful. I can't let him go and get his little hull stove in among them blessed heathen. It's another puzzler, Ben, and the puzzlingest kind of a puzzler at that."

The boy watched his friends face anxiously, while the struggle between his affection and life-long prejudices went on in the old seaman's mind.

"Well," said Ben at length, sighing deeply, "I can't get the kinks out of the matter nohow, so I will just cut the rope and say I'll go with you, lad.

"Thank you, Ben; thank you," responded the boy warmly. "Now let us lose no time. By the greatest good fortune the captain had the boat, which he intends to go ashore in himself to-morrow, lowered and stored with everything necessary. There are oars and a sail, arms and ammunition, and a quantity of food and water. I put in more myself after dark, so there will be enough to last a long while. It could not be better if we had done it all ourselves.

"Fate," muttered the sailor. "I said there was fate in it from the first."

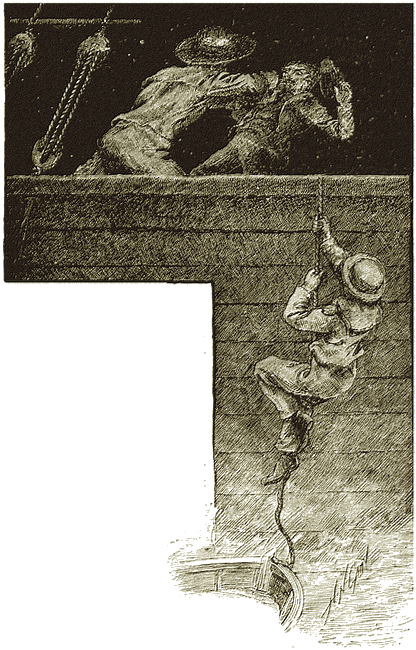

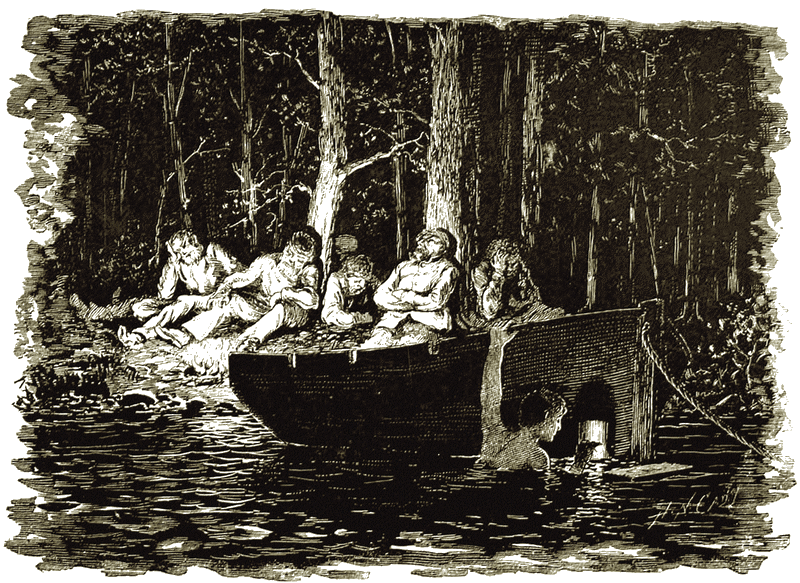

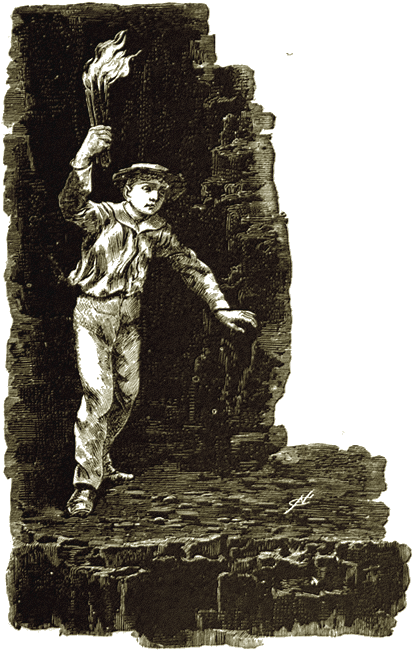

Extinguishing the lantern, the two friends made their way cautiously through the opening by which the boy had entered, and after much difficulty succeeded in gaining the deck of the vessel undiscovered.

The night was dark, though clear, and the stars were shining brilliantly in the deep blue of the sky overhead. A light breeze was blowing from the southward, and the vessel, with her bows to it and her sails loose, was riding the long, easy swells, without advancing. Not far distant, on one hand, an uncertain outline of deeper shadow indicated the position of the land. On the other, the undulating surface of the water melted away imperceptibly into the sky.

The two men who constituted the watch on deck were dozing near the stern, and the friends managed to creep to the forward gangway, where the boat lay alongside, without arousing them.

As they were on the point of lowering themselves into it, Ben turned, and looking back over the vessel said, in a low, regretful tone,

"A sweet boat she is, and it goes hard with me to leave her in this marine's fashion."

"Come, Ben," responded the boy, warningly; "if my cousin discovers us now neither of us will ever see Oo. You can judge by what we know of him what our fate would be."

"Yes, lad, yes," said the sailor; "Oo is the word now, whatever it may mean. And that little chart of your father's lays the course us two is to sail by hereafter."

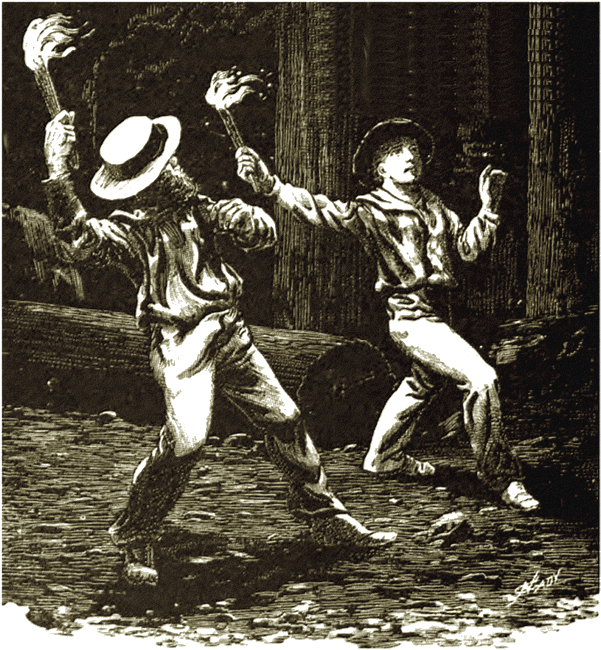

Neither of the friends had detected a dark form which had been crouching in the shadow of the bulwark in a listening attitude, while they had been speaking. But now, as they were in the act of descending into the boat, it darted forward and seized Ben by the shoulder. It was Captain Chadwick.

There was something so menacing in his swift, tiger-like movement that the boy shrank back with a shudder. Not so Ben. Large and heavy of frame and far from quick of perception ordinarily, this was one of the emergencies in which his presence of mind and extraordinary muscular power served him to good purpose. With the rapidity of thought he caught Chadwick by the throat with one hand, effectually preventing him from uttering a sound, while with the other he dealt him a stunning blow upon the forehead.

Lowering the helpless and unconscious form of their enemy to the deck, he signed to the boy to enter the boat, and quickly following him, cut the rope and pushed off.

All this had passed so swiftly and silently as not to have attracted the notice of the dozing men on the vessel's deck.

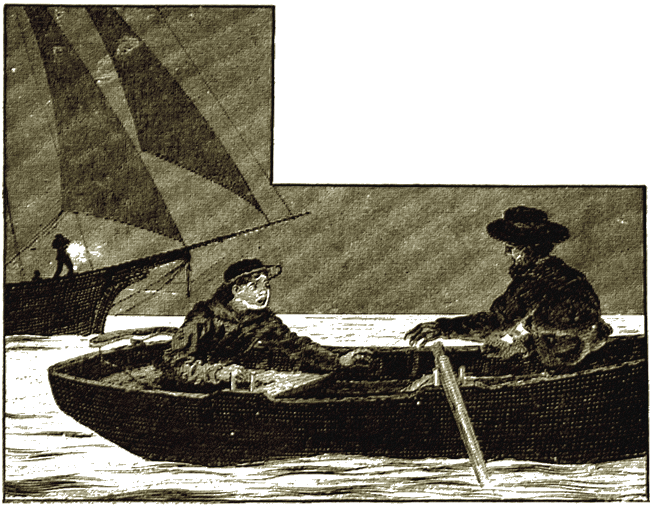

When they were at a safe distance from the vessel, Ben took up the oars and began rowing quietly.

"There," said Ben, philosophically, "I call that job neat and artistic, lad."

"I hope you did not strike him too hard, Ben," responded the boy, anxiously.

"Never fear," said the sailor, coolly; "it will be a matter of carrying his head in a sling a few days, that's all. If he will only have the kindness to lay quiet in the scuppers, where I put him, for an hour or so—Hark," he added, leaning forward to listen, and speaking in a disappointed tone, "I do believe I didn't hit him hard enough, after all."

A dull, confused sound came over the water from the direction of the ship and lights flashed out along her deck.

"Yes, yes," muttered Ben, "he has come to himself and in ten minutes will be after us. Row is the word now, lad, and forward to Oo!"

PROPELLED by Ben's vigorous arms, the boat was soon more than half a mile distant from the Swallow, But the creaking of the cordage, and the flapping of canvas, proved that she was being rapidly prepared for pursuit.

Rollin Faulkner was a boy of great natural courage and determination, but the consciousness of imminent danger and the strangeness of his position pressed heavily upon his heart. With a relentless enemy behind him, before him a wild country peopled by savages and full of unknown perils, and around him a lonely waste of water, gloomy and weird in the pale starlight, he might, indeed, be excused for the feeling of despondency which oppressed him now.

But the thought of the wrongs he had suffered and the great object before him soon renewed his firmness, and he grasped the helm of the boat with a resolution to face the situation boldly.

"Here she comes," muttered Ben, suddenly, as a dull rushing sound came over the water, indicating that the vessel was now in motion, "pointing dead this way, too.

"They will never find us in the darkness, said Rollin.

"There is good eyes and good night-glasses aboard that ship," replied Ben, "and a man who would give his right arm to get us back.

"You think that Chadwick overheard our conversation on the deck?" asked the boy.

"Certain, replied the sailor.

"Then he knows that we are bound for Oo, and that I have my father's chart with me. In that case, Ben, he will pursue us to the bitter end. But," said the boy, with compressed lips, "I will never give myself up while I live—never!"

"Right, lad," responded the sailor; "nail the colors to the mast and go down with them flying, if need be. But it ain't come to that yet, and I have faith in your luck, boy.

"Hush! what is that? interrupted Rollin, warningly.

"The Swallow," answered Ben, in a low voice, "lie down in the boat and she may pass without sighting us."

As he spoke, the tall shadow loomed up close to them, revealing the sails and spars of the vessel against the lighter background of the sky. It was a terrible moment for the two friends, as crouching breathless in the bottom of the boat, they watched the huge mass bearing swiftly down upon them.

For an instant it seemed certain that they were discovered, for the vessel came so close to them that they could distinctly hear the men on deck talking, and the sighing of the breeze through the rigging. But she passed on, and melting into the darkness, disappeared from sight.

"Is she gone? asked Rollin anxiously, as Ben arose and resumed the oars.

"For the present," replied Ben, "but we are not done with her yet. Chadwick will stand on as far as he thinks we can have possibly gone, and then come about and look for us on the other quarter.

"The land is not far off," said Rollin, "had we not better go ashore and hide among the woods? We should be safe there.

"That would be the same as giving up the cruise altogether," answered Ben. "Without the boat and wittles and water in that there wilderness, we should be like two turtles on their backs. And what is more, we should never set eyes on Oo—if there is any Oo—nor your father, either. Have you thought of that, lad?

"You are right, Ben," replied the boy, "It was a cowardly thought on my part. But what shall we do?

"Pull hard and take the chances," answered Ben, glancing at the stars. "We have three hours yet to daybreak, and by that time we shall be in the Darke River.

"Hist! whispered the boy, pointing out a dark object, which seemed to rise out of the water and approach them swiftly.

"The Swallow again!" said Ben.

This time the vessel passed at a considerable distance, and was soon lost to sight again the darkness.

For nearly an hour Ben rowed on steadily and the Swallow did not reappear. In spite of their better judgment the two friends began to hope that their enemy had either given up the pursuit, or had gone so completely astray as to give them no further trouble.

And now the sea, which had hitherto worn the dull grayish black appearance, common to it on clear, dark nights, began to assume a singularly mottled look. Here and there spots of pale hazy whiteness would gleam out brightly for a moment and then melt away.

The boy observed that every now and then the sailor would glance at the water on either side of the boat, with a dissatisfied exclamation, as if greatly displeased.

"What is it, Ben? he asked anxiously.

"Look, replied the sailor, dashing the blade of his oar into the water, so as to cause it to be violently agitated. The boy saw that each blow was followed by a thousand glittering sparks, flashing and dancing below the surface.

"Why, those are only phosphorescent little animals in the water and perfectly harmless, he said, in some surprise.

"Harmless!" ejaculated Ben. "Would the sun be harmless if it happened to be shining now?

"No," replied Rollin, "for it would betray us to those on board the Swallow."

"Well, wait a bit," growled Ben, "and see if them harmless little pollyglobbles in the water don't do the same for us."

Even as he spoke, a brilliant glow lighted up the water, spreading out far around them on every side. It was as if the full moon were shining, except that the lustre was of a greenish tinge and fluctuated with the motion of the waves. The two friends could see each others face's plainly, and at times the glow was so powerful that a pin might have been picked up by its aid.

This remarkable phenomenon is common in the tropics, and is caused, as Rollin said, by innumerable phosphorescent animals of minute size, which in certain conditions of the atmosphere, rise from the depths of the ocean and display themselves upon the surface. The two friends had often witnessed it before, but never so brilliantly as to-night.

The sailor's eyes, roving keenly around the horizon, became suddenly fixed with a heavy frown.

"Yes, yes," he muttered, "there she is, and I was fool enough to think he had given up the chase."

Following the direction of Ben's gaze, Rollin saw the Swallow about two miles distant, plainly visible in the phosphorescent glow, like a vessel afloat in a sea of fire.

She was headed away from them when they first saw her, but a few moments later she came about and lay with her bows toward them, bending over gracefully with the wind aft her quarter.

"A lovely boat she is," muttered the sailor, with a sort of angry admiration in his voice. "She comes in stays like a French dancing-master. Look at her now! nodding her foremast pennant like a little gal with ribbons in her hair."

"Do you think they see us? asked Rollin, with his eyes fixed anxiously upon the advancing vessel.

"Not yet," lad, replied Ben. "You see her nose lies to windward of us. But it won't be long before they do.

"Ben," said the boy, determinedly, "I would sooner risk starvation in the wilderness or falling into the hands of the savages, than give myself up to Chadwick again."

"So would I," answered Ben, "the worst kind of a snake would be innocent alongside of that pison varmint now."

"Then let us make for the land," responded Rollin, "and take our chances."

"I believe you are right," said Ben, after a moments thought, "it's our only hope now. Round with her, lad."

In accordance with this resolution, the boat was headed for the land, which was less than two miles distant, and the sailor bent to the oars with a vigor which made the frail vessel quiver.

Meanwhile the Swallow was advancing rapidly, but as she had not altered her course, it was evident that the boat had thus far escaped the keen eyes of Captain Chadwick. Moving in a direct line for the shore, and thus quartering the vessel's path, if she would but hold on her present course for a few moments longer, the fugitives might hope to get into shallow water, and thus baffle pursuit.

But suddenly the sailor, whose eyes were fixed upon the vessel, uttered a low growl of anger. Turning, Rollin saw that the Swallow's head now pointed directly toward them, while several of the lighter sails were being hoisted to increase her speed to the utmost. At the same moment a flash of flame broke from her side, followed by the report of a gun.

"Aye, aye," muttered the sailor, "we know you see us, without wasting powder to tell us so. That means stop! as well as a cannons mouth can pronounce the word, lad.

"I know it," answered the boy, between his teeth. "Faster, Ben, faster."

The sailor complied, putting all of his vast strength into the work, and the water hissed and bubbled around the boat as she flew through it. But, in spite of his utmost efforts, the pursuing vessel gained upon them visibly. She was now so near that the figure of her commander, illuminated by a lantern which had been hung in the rigging, was plainly visible to the occupants of the boat. Ben Bark smiled grimly, as his eye rested upon the large swelling which his fist had raised upon the captain's forehead, not at all improving the malignant expression with which he gazed at the two friends, now completely in his power.

"Heave to, there!" he shouted, "or I will cut you in two.

"Can't do it, Captain," replied the sailor, his respect for his superior officer struggling oddly with his anger. "Sorry I can't obey orders, and what's more, sir, I'll knock the daylights out of that ugly head of yours, captain or no captain, if you lay the weight of a rope-yarn upon the boy."

The ship swept by within a dozen oars' length, and as she passed, the captain raised a musket which he carried, and fired.

His intention had been merely to frighten the fugitives into surrendering, and he had aimed wide, but with a loud cry, the boy fell forward upon his face in the bottom of the boat.

With a roar like a wounded lion, the sailor dropped the oars and sprang to the boy's side.

"Oh you lubber, you cowardly lubber!" he shouted, in a voice full of rage and grief, shaking his fist at Chadwick, who, thunderstruck at the effect of his shot, stood staring at the motionless form of the boy. "You have killed the lad, as you did his father, you murdering ruffian."

Whatever evil he might have ultimately designed for the two friends, their open destruction had formed no part of Chadwick's plans. Astounded and unnerved, he ordered the Swallow to be hove to at a short distance from the boat, and as the pursuit was now over, he directed the lighter canvas taken in.

Meanwhile the sailor had been anxiously searching for the wound which the boy had received, mingling groans of sorrow with vows of vengeance upon the head of his enemy.

Suddenly, while he was thus engaged, the phosphorescent glow which had illuminated the scene, melted away in an instant, leaving all in darkness. The position of the ship, which had been almost as plainly visible as at noon-day, was now marked only by the lights in her rigging.

At that moment, Ben, whose face was close to the boy's, heard the latter whisper, clearly and distinctly,

"Row, Ben, row for your life!

"What—how?" exclaimed the sailor, dumbfounded, "what, lad, are you—?"

"Sound as a dollar," replied Rollin, rising to his scat and resuming the helm, "the ball did not come within twenty yards of me.

"And you really are not hurt, lad? asked the sailor, in a tremulous voice, which proved how deeply he had been affected by the supposed death of his young friend.

"Not a scratch," responded Rollin, grasping the sailor's hand warmly. "It was a ruse, Ben. I calculated that Chadwick would heave to when he imagined he had killed me, and that would give us a long start before they could get way upon the ship again. Don't you see, Ben?"

"Yes, yes," assented Ben, taking up the oars, "you were born for a commander, lad. But you gave me a turn, I can tell you. I was sure there was an ugly hole in your little timbers."

"We have fooled them completely," said the boy, with a low laugh. "Turn her head away from the shore and pull for all you are worth. It will take them a good while to discover the deception. When they do they will be sure that we have landed. At all events they will lose time in trying to find out. Meanwhile we shall be far away from here, eh, Ben?"

"Aye, lad," replied Ben, with great admiration, as he began rowing vigorously, but with caution, in a direction opposite to that in which they had been previously moving. "Thanks be to you for that same clever roose of yours, and," he added, reverently, "to the Great Commander aloft for taking pity on us and dousing them phosphorescent little pollyglobbles at just the right moment We shall win yet, lad. We shall win yet."

THE next half hour was full of anxiety for the two friends. Should Chadwick suspect the deception which had been practised upon him, he would immediately renew the chase with more determination than ever, and, as they had reason to know, with every chance of success.

But as the moments went by and the lights in the rigging of the Swallow remained stationary, the fugitives began to breathe more freely, A boat had been lowered from the ship, and by the lantern which she carried, her course could be marked as she moved to and fro on her futile search.

Presently she was seen to abandon her erratic course and make directly for the shore.

"There they go on a fools errand," said the sailor, with a quiet chuckle; "not finding us where they saw us last, they suppose we have gone ashore, and they are going to waste another half hour or so hunting for your dead body and my live one. Couldn't be better, lad. I do believe that we have seen the last of them."

The boy shook his head doubtfully. "Chadwick knows that I have that chart," he said, "and he will follow us across Australia to get it, or I am wholly mistaken in his character."

"Well," responded the sailor, "a stern chase is a long chase, you know, lad, and we shall be in the river by daybreak, barring accidents. Once there, it will be sharp eyes that will find us."

The Swallow's lights had by this time dwindled to mere red points, and that upon her boat had entirely disappeared. The fugitives had gained a start of fully four miles, by means of Rollin's clever ruse, and their boat was now among the short, rough swells caused by the mingling of the outflowing current of the river with the deeper water of the Sound.

Resting upon his oars for a moment, the sailor bent forward and gazed steadily into the darkness astern.

"Aye, aye, I thought so," he said, beginning to row again, "he has doused his lights."

"What do you make of that, Ben?" asked the boy.

"That he has found us out and is in chase again. He has put out his lights so as to be able to sneak upon us unseen. However, that won't do him much good, for we shall have daylight soon. And we shall need it, too."

The boy detected an accent of uneasiness in the sailor's voice.

"What is it, Ben?" he inquired, "some new danger?"

"Why, lad," responded Ben, "there is a small matter of a bar across the mouth of this river which kicks up a pretty lively swell. I had forgotten about that."

"You mean that there is danger in attempting to pass it?" said Rollin.

"Well," answered the sailor, "compared with that horse-marine Chadwick, the worst bit of water on earth is innocent and harmless. But I will admit that it is an ugly place, lad."

"But it can be passed?" said Rollin.

"Why, yes," was the reply, "it's bound to be a tough job, but with a cool head to steer and a pair of strong arms to pull, it may be done, lad."

"Very well, then," said the boy, quietly, "I shall try to keep the one and you certainly have the other. So pull away, Ben, and let us do our best."

"Aye, aye, lad," returned the sailor, "man or boy, no one can do more."

The first cold, pale glimmerings of dawn were now beginning to appear in the east. One by one the stars faded, leaving the one large planet of morning glittering in the widening arch of the coming day. Gradually the dusky surface of the water and the misty outlines of the distant land came into view, indistinct and uncertain in the imperfect light.

And now, faint and ominous as the far-off mutterings of a thunder storm, a low booming sound was borne to the ears of the occupants of the boat.

"The breakers," said Ben, answering the boy's inquiring look.

As the fog lifted slowly from the water, the two friends, gazing anxiously around them, saw the phantom-like form of the Swallow, less than three miles astern. She was still pursuing, though with a degree of caution which proved that her captain was thoroughly acquainted with the dangers of the shallow channel in which she was sailing.

But before them and still nearer, the fugitives beheld a more immediate peril, and one which would try all of their resources of courage and skill to overcome. To all appearance, it was a wall of snow, ten feet high, curving away on either hand for more than a mile. But as the light increased this wall of snow was seen to be in constant and violent agitation. Bending over upon itself, and every now and then throwing fountains of spray high in the air, its deep booming was like the voice of a waterfall.

It was the line of breakers, where the vast volume of water flowing out from the river rushed over the shallow sands at its mouth. Always a dangerous spot in the mildest weather, the recent storms had increased its hazard a hundred-fold. And even the stout heart of the sailor sank as he gazed at it.

Hemmed in by an implacable enemy behind and an almost impassable barrier before, for the first time Rollin felt a sensation almost like despair steal over him. But one glance astern, where the Swallow lay, renewed the boy's failing courage, and grasping the helm with a steady hand, he motioned the sailor to go on.

Here and there in the line of foam were darker spots, marking the places where the water was least agitated. Toward one of these Rollin directed the boat's course.

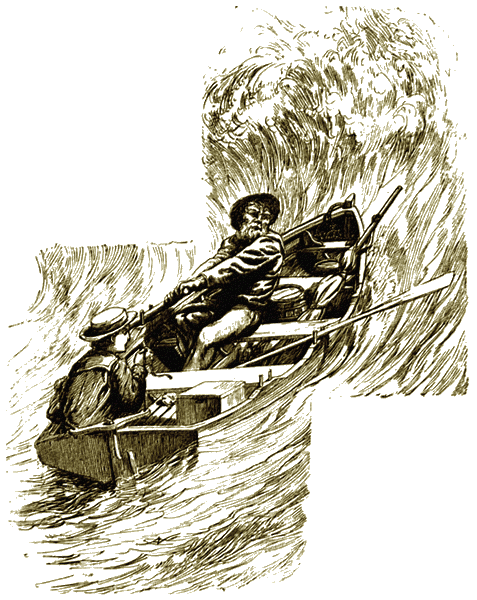

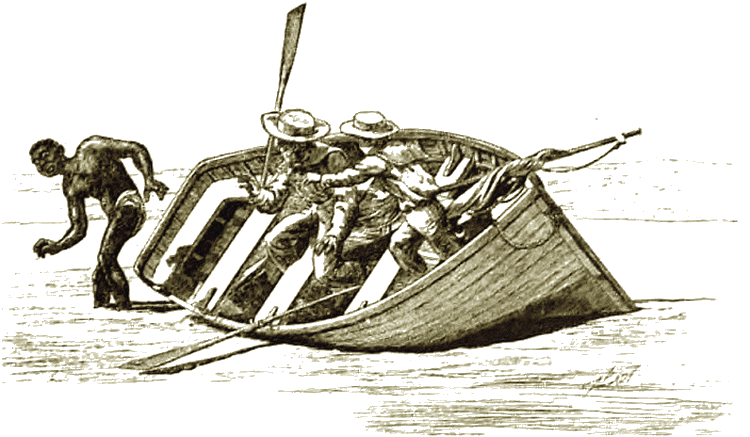

Pitching and tossing, so that the sailor had great difficulty in keeping his oars in the water, the boat approached the roaring, boiling surf. In another moment she was seized as by a giant's hand and hurled bodily forward. As she was carried onward, the force of the current swung her bow around. To meet that mountain of surging water, broadside on, meant certain destruction. This the boy was quick to perceive.

"Larboard oar!" he shouted, "larboard oar! hard! for your life, Ben!"

Planting his feet against the gunwale, he threw his weight upon the helm.

"Hard to starboard with her!" he cried again, "or we are lost!"

Throwing the whole of his mighty strength into his arms, the sailor tugged at the oar, until it bent like a reed. Had it given way, or had a thole-pin snapped at that juncture, all would have been over in ten seconds.

Fortunately, no such accident happened, and under the united efforts of the sailor and the boy, the boat yielded in time, and with a headlong swoop, plunged into the surf. For a moment the friends were literally under water. It poured over them in torrents, filling the boat to the gunwales, roaring around them with the noise of a thousand tempests, and burying them completely out of sight in a mad whirlpool of foam.

And during that awful moment neither of them drew breath, for both were convinced that it was their last on earth. Utterly helpless in the very jaws of destruction, they could only cling desperately to the frail vessel which bore them, and await whatever destiny might be in store for them.

At length, with a last violent shock, they were uplifted and flung forward into the calmer water beyond the bar. But though safe for the moment, they were by no means out of danger yet. A hundred yards ahead, another white wall, twisting and tossing in wild upheaval, betokened a second line of breakers which must be passed.

Dashing the water out of his eyes, the old sailor glanced around and comprehended the new danger.

"Bail!" he shouted, seizing a tin pail which lay in the bottom of the boat. "We must free her from the weight of this water, or she will swamp."

Working with the energy of despair, the two friends managed to relieve the boat of the greater part of the water she had shipped, before she reached the second line of breakers. They had barely time to spring to their places at the oars and helm when she was among them.

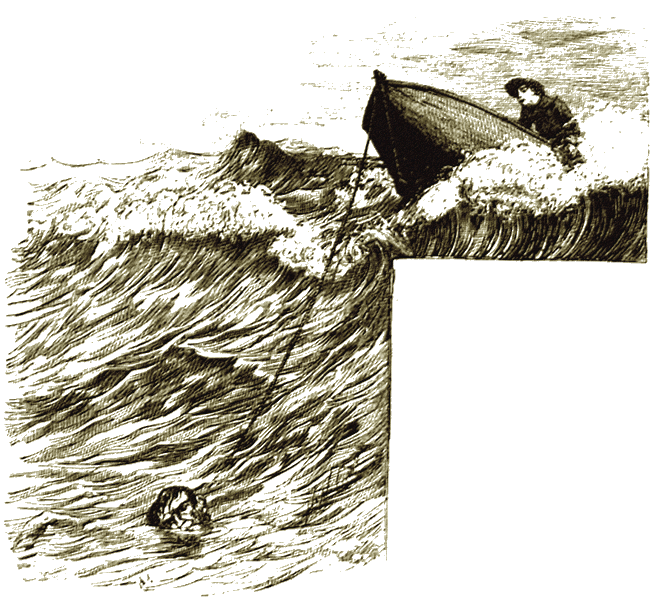

Though apparently less formidable than the outer barrier, the inner line of breakers was even more broken and angry. In spite of their frantic exertions, the boat again swung broadside to the surf and instantly filled, careening gunwale under. With a sick feeling at his heart, the boy closed his eyes and waited for the next billow which must surely overwhelm them.

As he did so the boat rocked violently and then righted a little. Opening his eyes, he uttered a cry of terror and despair. Ben had disappeared!

In another moment, however, the boy saw him, with the painter of the boat between his teeth, battling gallantly with the waves. With a last hope of saving the boat, the brave sailor had plunged overboard, and was trying to drag her through the breakers, at the imminent risk of his life.

Utterly helpless to assist him, the boy sat gazing at his friend, as, borne aloft upon the crest of a wave, or buried out of sight beneath it, he swam slowly on. Only a man possessed of his gigantic muscular power could have lived an instant in that maelstrom.

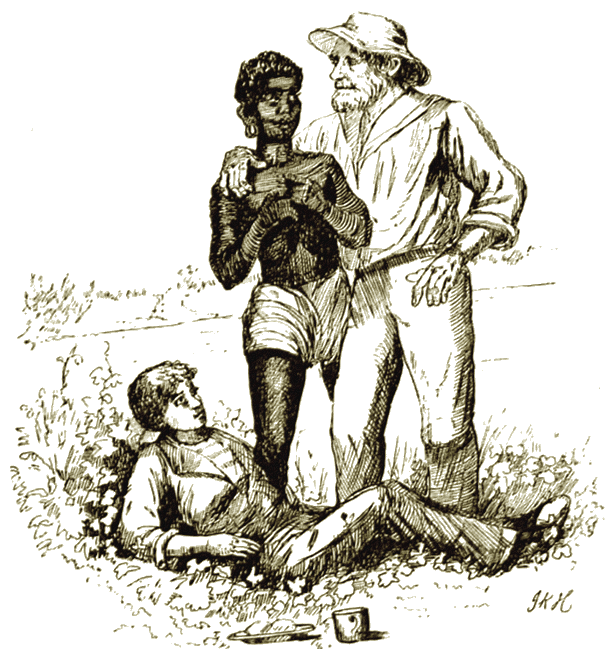

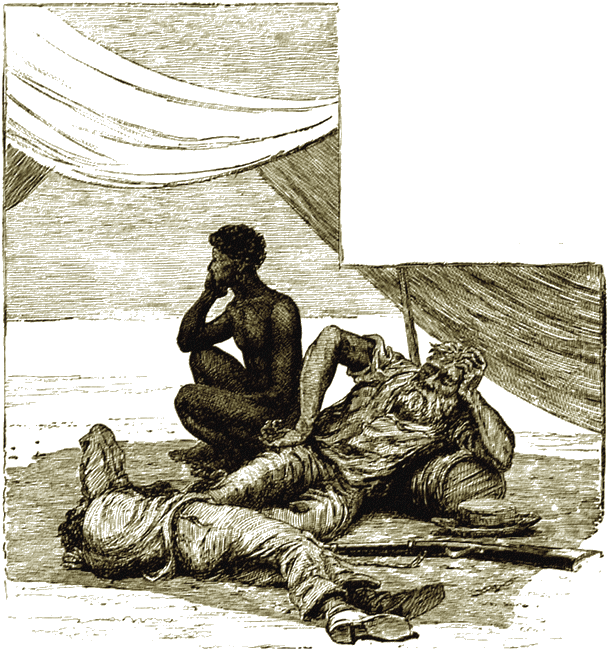

At length, with a final plunge which nearly threw the boy out of the boat, she shot forward into calmer water. Exhausted by his almost superhuman exertions, the sailor had only strength to climb into the boat and throw himself into her bottom, where he lay very pale, with closed eyes.

Alarmed by his livid features and blue lips, Rollin knelt beside him and chafed his cold hands. Gradually, however, the color returned to the sailor's face, and with a deep sigh he sat up and looked around with a bewildered air.

"Oh, Ben!" said Rollin, reproachfully, "how could you do it?"

"The boat was sinking, lad," replied Ben, seriously, "and I knew that once among those breakers you would be pounded to death in a twinkling."

"And you risked your life to save mine?" said the boy, in a trembling voice.

"Why," returned the sailor, argumentatively, "it's a matter of profit and loss, as the landlubbers say. If anything was to happen to you, the rest of old Ben's cruise in this here world would be in lonely waters, lad. So you see it was a matter of mere selfishness on my part, after all."

"People call that kind of selfishness very noble, Ben," replied Rollin, smiling.

"Do they, lad?" said the sailor, quietly. "They have queer names for things on land. So we won t say no more about it."

"All right, Ben," replied the boy, "but I shall not forget all I owe you."

"That there little swim has given me the appetite of a shark," said Ben, evading the boy's gratitude for an action which he evidently regarded as a mere matter of course. "What do you say to piping to breakfast?"

The boy consented, and while Ben continued to row, busied himself in preparing the meal, of which both stood in great need. A supply of tins of preserved meat and other eatables formed a part of the boat's cargo. Stored in watertight lockers, the food was found to have escaped damage from the breakers, and Rollin soon had a substantial repast of biscuit, ham, and tongue spread out upon a thwart between them.

"I call this here comfortable," observed Ben, taking a huge bite of bread and ham. "With a clear conscience and a hold full of good wittles, a man can face most of the troubles of life without flinching. Now if we are called upon to beat to quarters again, we shall be prepared to show the enemy a bold front."

"Do you think they will try to pass the breakers after us?" asked the boy, his bright face clouding over at the thought.

"Well," replied Ben, "I think they will not try it for at least twelve hours to come. By that time the effects of the storm will have subsided, and with a heavy, eight-oared boat they ought to come over dancing."

"And by that time we shall be a good many miles up the river, eh, Ben?" said Rollin, somewhat reassured.

"Aye, aye, lad," replied the sailor, cheerfully, "make your mind easy. Now, seeing that my old timbers are a bit strained after last nights work, I am going to ease them off for the matter of a half hour before we set sail again."

Disposing himself comfortably in the bottom of the boat, the sailor drew out his pipe, filled it, and began smoking with every appearance of satisfaction.

Though greatly fatigued himself, the boy was still too much excited to imitate his example. Besides, the consciousness that the danger was by no means past, but merely suspended for the time, did not tend to reassure him. He lacked the coolness which long experience had taught the sailor, whose philosophy it was to make the most of the present and to let the future take care of itself.

Therefore while his friend lay quietly smoking, Rollin sat gazing around with anxious and watchful eyes. The white wall of foam, which they had just crossed with so much danger, was plainly visible, and its dull, incessant roar was borne faintly to his ears on the gentle morning air.

Everything was so quiet, the water was so smooth, and the sun so warm and bright, that in spite of his forebodings, the boy felt a drowsiness stealing over him. Suddenly his half-closed eyes, which had been fixed upon the line of breakers, opened wide with a look of doubt and alarm. He sat upright and gazed breathlessly at the object which had startled him.

"Ben! Ben!" he cried, in a tone of terror, "look! look!"

The sailor sprang to his feet. Following the direction of the boy's pointing finger with his eyes, for a moment, Rollin saw his ruddy cheek grow pale and his lips compress themselves tightly.

Throwing aside his pipe, he seized the oars and began rowing with desperate energy.

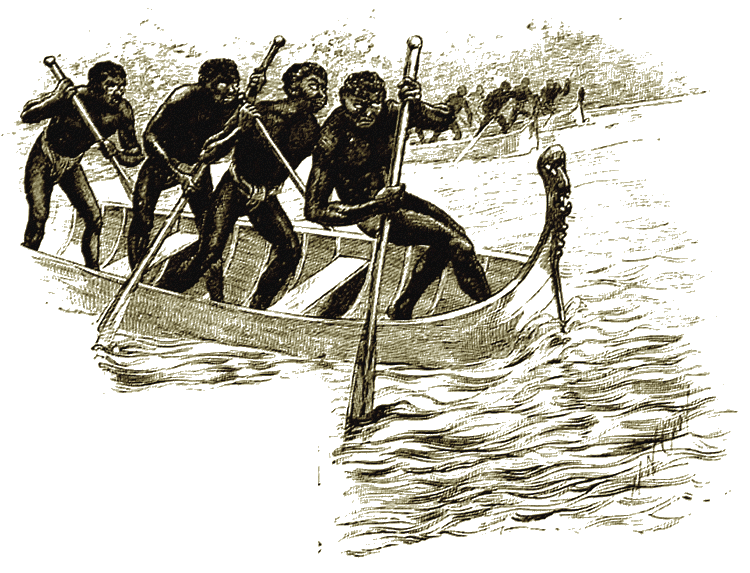

THE character of the object which had startled our adventurers was plainly evident even at that distance. A large boat, pulling eight oars, was rising and falling upon the breakers; now lost to sight and again poised upon the crest of a wave. Who commanded it and the purpose upon which it was bent, the friends never for a moment doubted. Chadwick was again in pursuit of them.

In the bitterness of his determination to capture them, he had not been willing to wait until the subsidence of the breakers should render the passage safe and easy, but had resolved to make the attempt immediately at all hazards. Thus Ben's calculations of a twelve hours' start were upset, and the pursuit at once assumed a critical aspect.

Despite her weight and number of oars, the Swallow's boat was evidently experiencing much of the danger and difficulty which the smaller boat had met with. More than once she seemed upon the point of foundering, and only escaped by the most violent exertions on the part of her crew.

Meanwhile the two friends were making the most of the delay, and when at last the Swallow's boat succeeded in getting over the barrier, the smaller boat was a good three miles away and about the same distance from the mouth of the river.

The broad sheet of calm water inside the reef narrowed gradually on either hand, until it reached the true mouth of the river, which was little more than a hundred and fifty yards in width. It was toward this point that the fugitives were directing their course. The banks of shallow tropical streams, like the Darke River, are always more or less fringed with tall reeds and overhung with luxuriant vegetation. If, therefore, the friends could gain the shelter they were aiming at, sufficiently in advance of their pursuers, their chances of escape would be greatly increased.

As we have said, when the Swallow's boat finally got through the breakers, that containing the friends was about three miles ahead and about the same distance from the mouth of the river.

Now, though much the lighter and smaller of the two, the escaping boat was in reality fitted for four oars and had been built for capacity rather than speed. Hence, even with Ben's great strength, she was no match for her pursuer.

From the rapidity with which the Swallow's boat came on, it was plain that Chadwick's liberal bribes and promises had overcome any favorable feeling toward the friends, which may have previously existed in the minds of the rough men who composed her crew.

With the perspiration streaming down his face and the muscles starting out upon his brawny arms, the old sailor labored grimly on, like an angry Hercules. Struggle as he might, however, the space between the two boats decreased visibly, until less than three hundred yards of clear water separated them.

They were now but little more than that distance from a long, low point of land, covered with dense shrubbery, which must be rounded in order to enter the river. Though the hope of escape was well nigh extinguished in the hearts of the fugitives, Ben put forth his last resources of strength and rowed furiously, while, incited by the voice of Chadwick, who was steering, the crew of the Swallow's boat bent to their oars with redoubled energy.

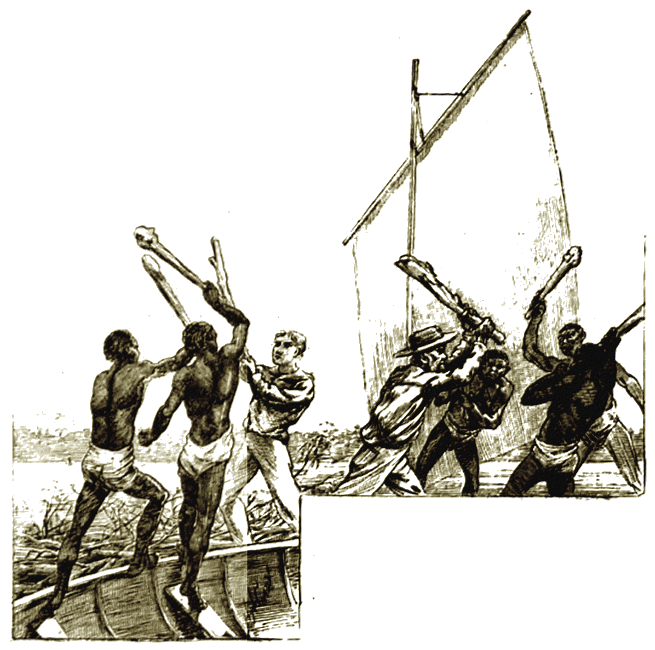

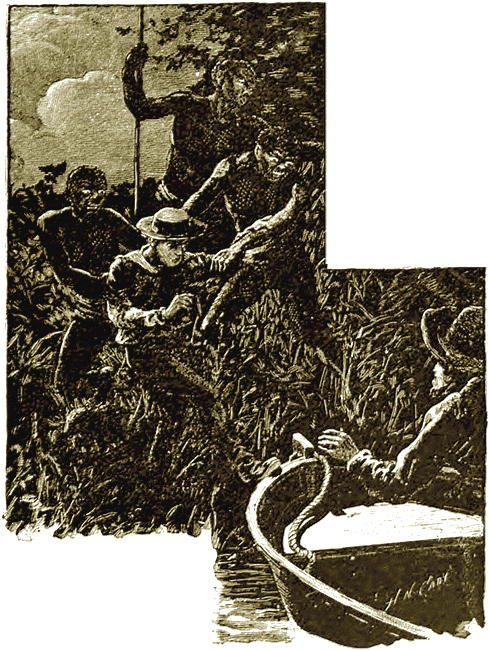

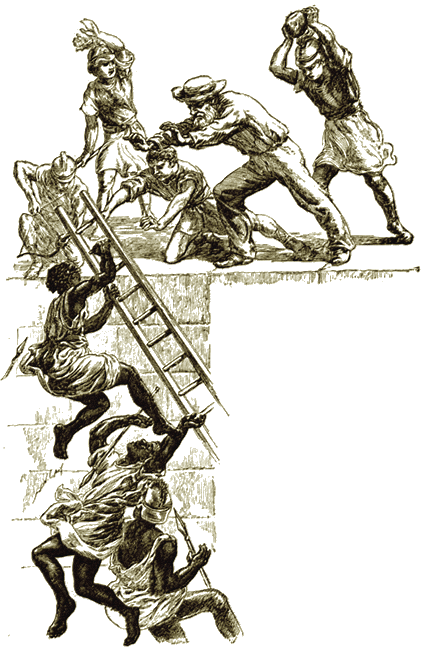

The two boats rounded the point of land within two oars' lengths of the steep wooded shore, and so close together that the bow oarsman of the larger boat could have touched Rollin with his outstretched oar.

As we have said, the old sailor possessed an unlimited belief in his own prowess, and desperate as the odds looked, he was by no means ready to admit that he was not a match for the whole of their pursuers together, in a hand-to-hand combat.

"Stand by to keep way on the boat," he said, between his teeth, "while I floor them one after another."

Even as he spoke, the two boats touched. The man in the bow had arisen to seize the gunwale of the smaller boat, when a tremendous blow on the side of the head sent him sprawling among his companions.

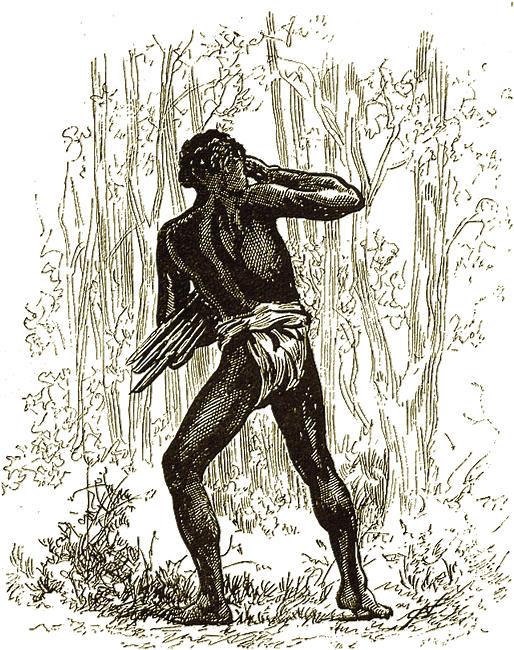

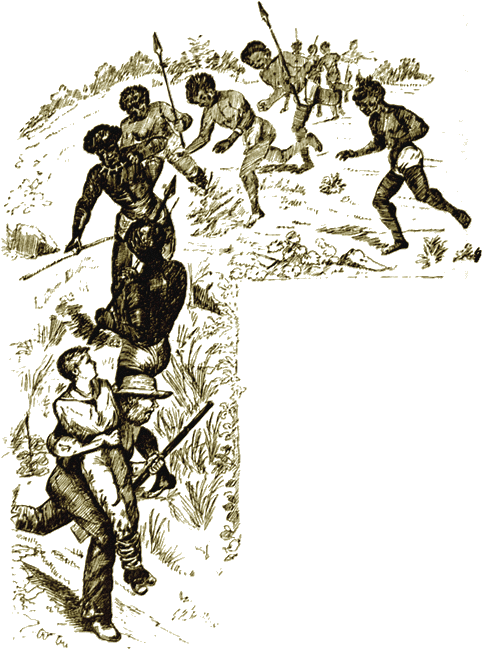

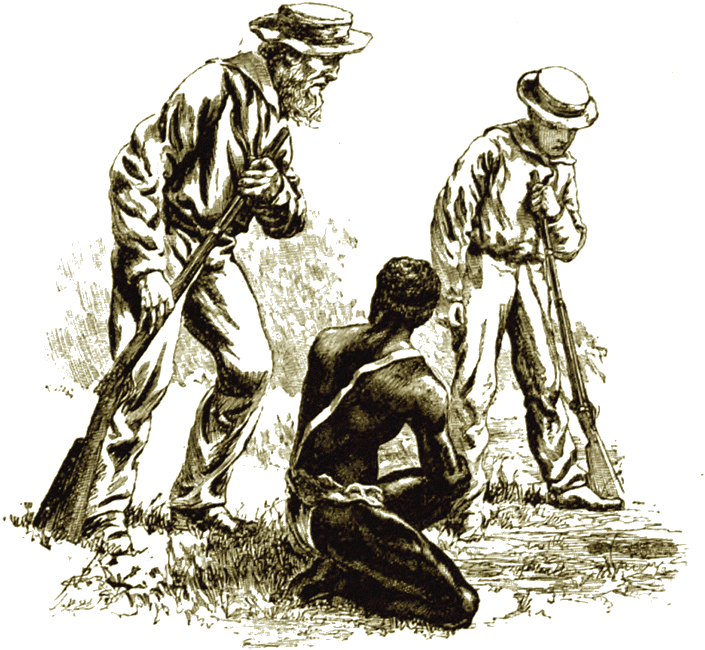

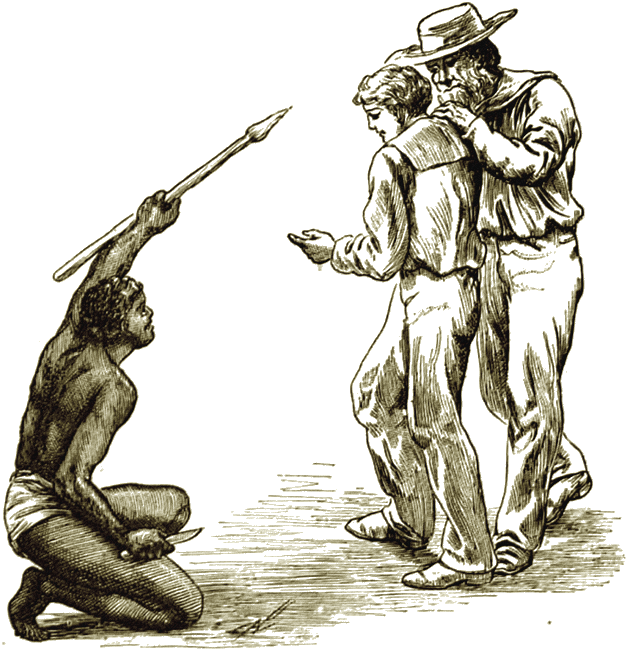

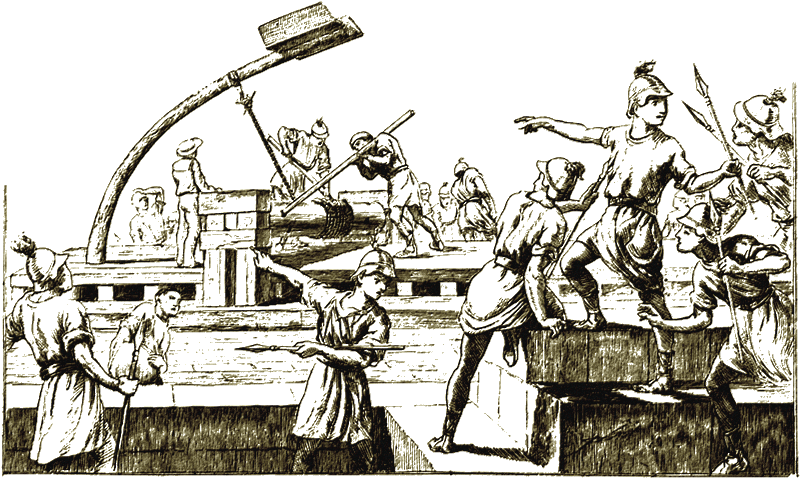

But it was not Ben who had administered the blow. A score of naked, dusky forms sprang out of the shrubbery, and with unearthly yells attacked the crew of the Swallow's boat, who, utterly surprised and unprepared, received considerable damage before they could arouse themselves for the defence.

For some reason, probably because the larger boat seemed the more valuable prey, the savages had directed their whole attention to it, while the two friends had been allowed to pass unharmed.

Recovering from their surprise, the crew of the Swallow defended themselves with spirit; fighting with oars, clubs and boat-hooks. Many a black fellow went howling and disabled from the melee; but others took their places, swarming about the boat in the water, or discharging their missiles from the bank. Shouts, cries and yells and the sound of weapons falling upon naked backs or uncovered heads arose from the confused mass of black and white combatants.

Astounded at the sudden and unexpected turn of events, the two friends sat motionless in their boat, at some distance, watching the strange battle with a variety of emotions. Though the whites were their enemies, and but a moment before they had been prepared to oppose them with all their strength, they could not witness their danger now without a strong impulse to assist them against their black foes.

The old sailor's eyes flashed and his fingers clenched with the ardent desire to take part in the combat. But it must be confessed that it would have made no great difference to Ben which side he fought on. So long as he could be in the thick of it, it would not have been a matter of much importance to him whether his fist encountered a white head or a black one.

"No, no," he muttered, shaking his head, "it won't do, Ben, it won't never do. Though it do seem hard to stand off and watch a fine sight like that there, and not take your natural share in it. Well, well," he added with a sigh, as he resignedly took up the oars, "we must learn to make sacrifices, I suppose."