RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

HE two men in Room 390 on the tenth floor were not happy. It was an hour since their talk had ended in a weak tempest of invective, and the situation remained as uncompromisingly blank as ever. Also, there were exactly seven cents in the common purse, the whisky stood at zero in the bottle, and the mercury in the thermometer bid fair to knock a hole through the top of the tube. It was, by the testimony of the daily papers, "one of the hottest summers that have ever visited this city."

Men worked in their shirt-sleeves throughout the fourteen floors of Michigan House, and the two occupants of 390, Floor 10, stood in a like comfortable negligé at separate windows of their office. To sit waiting in the dingy room was unbearable; and the visible presence of the outside world brought at times a more cheerful companion to the thoughts that held sinister parliament within them. Far below, through the thin mist that out-ran the evening, the city of Chicago rolled northwards in octagonal blocks to where the sudden blue of the lake took on the prospect to a silvered streak of horizon.

The windows were set high in the monster building, so high that, save directly underneath, where the men and the cars mingled like tiny black dots and cubes under the microscope, the streets were only visible as narrow channels traced among the roof-tops. A busy hum came up from the town, a hum aggravatingly suggestive of the ceaseless making of money—money that the two men in the room could by no means obtain.

A busy hum came up from the town.

It was the grizzled old man with the tired curve in his shoulders who broke the silence.

"I kin see," he said, and his voice came dryly from the back of his throat, "houses fur miles and miles, in which houses, sonny mine, air thousands of folk with no call ter blaspheme agin the Almighty."

He turned from the window, and a rippling wave of humour drove some of the creases of despair from his weary face as he looked towards his companion.`

It was five long minutes, while the city purred outside and the elevators jangled incessantly past the doorway, before the young man faced inwards to the room.

"Oh, can you see," he snarled; "well, my gifted old sightseer, it would be a sight more to the point if you could cock your eyeball on some one—James Norrie for choice—coming quick with money for the spinnin' of my little wheel. Look again, old man, and good luck to your eyesight." He walked towards the table, two yards of thick bone and good muscle, with a queer light in the blue eyes, a light that had made men leave the poker table, and once a woman catch her bonnet by the strings in the very article of throwing it over the mill.

His father—for they were father and son, Curtiuses of decent stock from Maine—jerked the gum into his other cheek, and, settling it with a thrust of the thumb, answered sharply:

"Darn your wheel, and you too, you great long loon; how long am I to waste bad names on you? Stick to your mechanics, I say, and leave the worldly wisdom racket to your old father. Hullo! visitors for Curtius and Co. By the Lord! it is Norrie."

The door had flung suddenly open to admit a young man of an exceedingly proper appearance. He was English, with the flamboyant insularity of the Englishman from home, and at intervals he cast a look of apology over the patent Americanism of his clothes.

"Yes, it is Norrie," he said; "Norrie whose visits are so few and far between, if not I fear, so attractive as angels' visits; but this time"—he struck an alarmingly theatrical attitude—"I come to save the State."

Stepping forward, he whipped a black bag from behind him with the flourish of a conjuror, and banged it down among the littered papers on the table.

"I am very glad to hear it," said Mr. Heber Curtius the elder, "the State wants it; and Joan, I reckon Joan'll be along soon?"

John Curtius laughed harshly.

"Joan is well?" he drawled, and his lips curled sneeringly over the words.

The little man flushed, and his aplomb died from him.

"I am glad to say, gentlemen, that the incident of Joan is at an end. I come on the best of business. Look at these, gentlemen, and these." He fumbled in his bag, and jerked notes in little packets on to the table.

Two months ago Lames Norrie had drifted across the path of the Curtiuses, and, fired by the schemes of the adventurers, which certainly were, in the language of John Curtius, "colossal," had been big with promise of capital. Then distraction, in the shape of Joan, a wisp of a brown-eyed girl, with shapely legs that flung skywards a shade higher than those of her companions of the Eldorado Quartette, had intervened; so that the Curtiuses sat moodily apart, living on the unsatisfactory food of hope as doled out by the errant Norrie at irregular intervals.

The sight of the unlooked for money wiped the care from the men's faces, as the sponge cleans a slate; neither spoke, but both watched intently the fountain of greenbacks that spouted from the bag. His task ended, the little man looked up with a smile.

"Money to make the wheel go round, eh, John?" he queried.

"That's so,"—John Curtius' voice shook with excitement—"by gum, that's so; this day a very few weeks, Mr. Norrie, a tenth floor single-room office don't show the door-plate of Curtius, Norrie and Co."

"Then," shouted the old man, his back straightening with a jerk, "in the face of my words, my most insultin' words, you two air loony enough to believe you kin bluff a roulette swindle like John's yonder in the face of the American public." He jerked out his sentence with an emphasis that culminated with a scream of consonants in the penultimate word. "Sonny, there'd be shootin' round that table inside an hour's gamblin'. I don't hold with it, Mr. Norrie, and I was playin' draw poker before you were born. Thirty-five years' experience, sir, gives a man leave to talk big about gamblin'."

"Oh! stuff an' nonsense." It was not hard to know, as he spoke, that the younger Curtius was usually at the helm of the joint enterprises. "Rubbishin', hogwashy nonsense," he went on, "we aren't in the forties now, and we don't propose to play our gamble in minin' camps. Here's one of the neatest swindles the world's yet seen, and Heber Curtius afraid of his public. Mark me, dad, it's this infernal caution of yours that's landed us, stony broke ne'er-do-wells, in Chicago; and where it may land us in the end, the Lord above knows only!"

"Gentlemen, please"—the suave English of Norrie came as oil on the troubled conversation—"there is no need to quarrel, I have not only brought the money, I have brought a plan of campaign as well. There is a good deal of sense in your father's arguments, John; people are too inquisitive in America. Now listen, and if I may, I'll send for whisky—no dry man can talk through this heat. Can I get a boy?"

"I'll tell the elevator kid," said Heber; and, going to the door, he shouted hoarsely.

"I hope your other idea's as good as that one, Mr. Norrie," he said, when the boy had gone. "Holy G——! I was dry."

"Listen then," the little man went on: "I was once, before the unfortunate occurrence, now, I have reason to believe, forgotten, an undergraduate at Cambridge; very shortly I am going to become an undergraduate at Oxford,—so is John—and the roulette wheel shall be not the least important item in our baggage."

"And me?" queried the old man.

"Oh, you shall be in it, Mr. Curtius, I've got a big part for you. Oh, how you will like the undergraduates! Simple—and you an American professional gambler. You'll hardly credit how simple they are. And lots of money, and they love to gamble, and when they've lost everything, they'll borrow more to lose; but as for thinking about concealed electric batteries, why, they'd never dream of it. Do you follow me, gentlemen? It is at Oxford that John's little wheel is going to make the first of its fortunes."

John Curtius was sprawled over a wicker chair, listening with an air of amused intolerance. "Well," he said, speaking slowly with an exaggerated emphasis, "I am not personally a gambler by trade. I have not run a mile in a boom city street with the gunshots spoilin' the sidewalk around my heels."

The old man shivered, it was one of his least happy reminiscences; also, when it rained, his left leg jogged his memory.

"Nor," continued the young man, spitting elaborately against the stove bars, "have I ever written a reverend gent's name across a thirty-cent bill-stamp." It was Norrie's turn to shiver.

"These references, John, are in doubtful taste, they are also beside the point."

He coughed deprecatingly, the signature of the Dean of Trinity had been a terrible failure.

"All I wanted to point out"—the voice of John Curtius could be unpleasantly sarcastic—"is that I am not myself a gambler, wherefore I make no comments. If there is better money to be got in Europe, I back down, but I should like to meet the man in this up-to-date brainy continent who could spot anything shady in my little invention. Let me show you again."

"Oh, let the blame thing rest, sonny, we know its workin' by heart; Mr. Norrie has struck the right nail. Play it in the old country, we are safe; play it here, there'd be shootin'—and you'd make a tidy target, John. Say on, Mr. Norrie," and Heber cleared a sitting space for himself for the table.

"Oh, I back down," said John, "and here's the whisky; put it there, kiddy, and if any one wants Curtiuses', you've never heard of any—see? Now, Norrie, spit out your plot, you're driver this trip."

NORRIE'S scheme was simple. He was to enter the University at

one college; John Curtius, as a young American of large fortune,

at another. Heber Curtius the elder would be the concealed

manipulator of the machine, and would, as far as possible, be an

invisible partner. The gambling would take place in Norrie's

rooms, in which John, as a casual acquaintance, was to lose large

sums. A sufficiency of the right sort of players could be, Norrie

asserted, most easily discovered.

As the money required for the preliminary stages of the adventure had been obtained—they did not press Norrie as to the means of its acquisition—there was no need for further delay. Tickets for the voyage were taken that same evening, and as, three days later, the "City of Paris" surged into the swell, while Sandy Hook faded below the horizon, two of the partners in this novel enterprise were conscientiously employed at the poker table in the handsomely appointed smoking-room of the vessel.

THE voyage passed without remarkable incident, and within but

a few hours of the record passage. John Curtius, who was never

tired of asserting that he was a gambler by chance, but by no

means from choice, eschewed the smoking-room and became a great

favourite among the engineers, who, by some fortunate chance,

were not one of them Scotch. He had all but converted the chief

to his theory of aerial navigation, when the appearance of the

English coast concentrated the worthy fellow's thoughts on his

wife and children at Fratton. Norrie, however, and old Heber

Curtius stuck perseveringly to their métier; and though

the really remarkable frequency of four aces in Mr. Curtius'

hands excited some unfavourable comment among jealous passengers,

the two confederates stepped on to the quay at Southampton with a

comfortable addition to their capital.

As some time must of necessity elapse before arrangements could be completed for Norrie's and John Curtius' début as undergraduates of Oxford, they took rooms in a secluded portion of Chiswick, and in the energetic carrying out of the many essential preliminaries, the days passed quickly and happily enough. The matter of the necessary matriculation presented the greatest difficulty. Norrie broached the subject somewhat suddenly. "It will be necessary," he announced one morning at breakfast, "that we renew our acquaintance with the classics and the elementary mathematics, for there is an examination ahead."

John Curtius threatened a return to America; but eventually his fears were overcome, and, with the assistance of a clergyman in reduced circumstances, from whom he took daily lessons, he became an apt and even interested pupil. Meanwhile, Norrie, who was a real expert in handwriting, set about preparing the testimonials that were to be their passports into the University. Heber Curtius, who was perforce idle, made many expeditions about the Metropolis. He had formed, in a West-end bar, a chance acquaintance with a Mr. Caradoc Milnes, an author, and his father, whom the young man jokingly alluded to as Uncle Fiddeyment, a very pleasant, laughable old fellow with an intimate knowledge of life in London. He became Mr. Curtius' cicerone in many an exciting ramble.

The affair proceeded in a most satisfactory fashion. The testimonials, of which Norrie was justly proud, were accepted without a murmur. John Curtius invented an elaborate arrangement for concealing notes about the person, with the aid of which they both easily satisfied the examiners, and on a fine morning in the late Spring took possession of their quarters in Oxford.

They had decided to wait for the Summer Term, for, according to Norrie, the undergraduates were accustomed to devote that portion of the academic year almost entirely to idle amusements.

Both the young men had obtained permission to live out of College, and Norrie, whose rooms were to be the scene of the enterprise, had obtained a really magnificent suite of apartments in the Cornmarket.

A few days were spent in making preparations for the working of the machine. John Curtius' roulette wheel was in appearance exactly the same as those commonly used in private houses, in which the numbers are so arranged that the reds alternate with the blacks, the even with the uneven, and those over eighteen with those under eighteen. Its peculiarity lay in a device by which either the red or the black, the high or the low, the even or the uneven, could be magnetised at will. The ball was composed of steel, with but a thin coating of ivory, so that it was certain to finish its journey in one of the magnetised compartments. The speed at which the ball and the disc travelled were amply sufficient to effectually conceal any slight impetus or deflection in the course of the ivory sphere. However, as an additional safeguard, the conspirators had determined to have lights reflected brightly on to the tables, leaving the wheel somewhat in shade. The players were to sit about three sides of a long table, and the wheel was to be placed on a small table at the end. Beneath the floor, and by means of the legs of the small table, electrical communication was established with the next room, in which, observant but unobserved, Heber Curtius was to work at the direction of Norrie, the croupier, whom he could see through a minute slit in the wall. The manner in which he laid his hand upon the table was to indicate which of the sections of numbers the croupier desired to be magnetised. In this way Mr. Norrie and Messrs. Curtius were able to take a bank at roulette, against which a syndicate of millionaires would have been impotent of success.

IT was a notable night in their history when, the trial trip

of the apparatus having most admirably succeeded, they went out,

all three together, to enjoy a dinner at a restaurant in the

town. A fortunate chance in the conversation brought the name of

Fiddeyment Milnes from Heber Curtius' lips; and, at the sound, a

tall gentleman, of a very winning manner, started up from an

adjoining table and approached them. It was not right, he

explained, that mutual friends of Uncle Fiddeyment's should

remain strangers to each other; and, excusing his intrusion on

these grounds, he proffered an invitation to his rooms, where he

was giving a party for baccarat and other card games. Here was

luck, indeed; here were fish to be caught, with scarce the

trouble of casting a line. The three accepted at once, and during

the evening made a number of friends. Invitations to other card

parties followed, at which the pleasant manners of Mr. Norrie and

the quaint eccentricities of the two Americans attracted the

friendship of many.

When, at last, it was judged advisable to open Norrie's salon, his invitations were eagerly accepted. To cement the position, Mr. Fiddeyment Milnes, who enjoyed an extraordinary popularity among undergraduates, was asked to Oxford on a visit; and James Norrie's parties became so rapidly fashionable, that all conditions of young men intrigued to have the entrée. To accept Norrie's abundant hospitality at dinner, and, subsequently, to be seen at the gaming table in the Cornmarket, conferred that term a cachet of social position. Roulette, save for the smallest stakes, was of rare occurrence in the University; but the high play and elegant surroundings gave Mr. Norrie's salon all the flair of a continental casino, and it was proportionately attractive.

They were merry parties. Uncle Fiddeyment was pressed into service as croupier, and, a stalwart grog ever in front of him, maintained an incessant flow of the cheeriest witticisms. At the wheel, Norrie, alert and urbane, threw the fatal ball, and piled the winnings in the copper box at his elbow; while Heber Curtius, behind the wall, attended to the switches with the conscientious regularity of a signalman in his box. John Curtius lost large sums of money nightly, and invented surprising histories of his adventures on the Pacific slopes.

They were merry parties.

The money rolled in in surprising quantities—you would not have thought there were so many sovereigns in the University. The possible interference of the authorities was, at first, a cause of alarm to some; but as the weeks passed, and no vision of proctorial dignity ever darkened the door, all fears were gradually allayed. It was certain that Heber Curtius might often be seen in the saloons of the town, jovially conversing with men of a large carriage, and that these conversations frequently ended with a quick passage of hands and a distinct clink of coin; but he made no public mention of his expeditions.

The fame of the parties spread even to London; and Mr. Caradoc Milnes, with his rich friend Mr. Cormorant, would often organise Saturday-to-Monday parties for the purpose of gambling at Oxford.

Norrie was completely happy. He was making money easily and quickly, and, what was the more pleasurable to him, he was doing it in the society of gentlemen. He shuddered when he remembered some of his associates in America. There seemed no reason why the gambling salon should not be continued for many Terms to come: and he had settled down into a lazy, careless life that exactly suited him.

IT was on the Monday morning of the sixth week of Term that an

element of disquiet appeared in his life. While walking, as was

his custom, in the High Street before lunch, he was startled by

the pronunciation of his name in a melodious female voice.

Turning rapidly, he was confronted by a young lady of great

personal charm, and most elegantly dressed.

"I thought I recognised you, Jimmy," she said, "though it must be, let me see, ten years."

"Eleven and a half," corrected Norrie, with all the composure he could muster.

"Well, a very long time since the night that you came to me with the tale of your troubles."

"And you lent me the money to go away. I have never forgotten, Agnes. For all these years—hard years, many of them—the memory of your kindness has been my dearest possession. But I am an outcast now; I do not seek my old friends."

"Oh, the world has forgotten."

"And you, Agnes?"

"And I have forgiven. You were very young, Jimmy, and, perhaps, not altogether to blame. Well, let us leave the past. What are you doing in Oxford? I have come down for the eights."

"And Mr. Wagstaffe, your husband, is he with you?"

"Edward is dead."

They walked some way in silence.

"Yes," she continued, "I am a lone, lorn widow, rather solitary with all my money. I am quite alone here, save for my maid. I often come to Oxford; the sight of these boys puts months of fresh youth in me."

"If you are alone, Agnes, and you are not going to treat me as an outcast, may I see more of you? I should like to talk over old times, some old times."

THEY lunched together that day, and subsequently, save when

the business of the gambling called him, Norrie was rarely absent

from Mrs. Wagstaffe's side. In times gone by he had loved her

with a mad, boyish passion, and during all the years of exile the

love had slept but fitfully; the presence of her image in his

heart had been the most cruel part of his punishment. To be with

her again, to find the prettiness of the girl mellowed into the

gracious beauty of the woman, and above all, to and that he was

forgiven, seemed almost too much happiness to be true.

It was four days before he dared frame with his lips the words that were constantly shaping in his heart. Then, one fair summer's afternoon, as they sat, heedless of the roar of the races in the river beyond, in his punt beneath the trees that fringed a breakwater, she consented to be his wife.

Almost from the hour that he had first met her in the "High," he had determined to be done with the gambling. The thought of his ill-gotten gains seemed to choke the love phrases on his lips, the possibility of detection and shame, hitherto the faintest shadow on his life, became an ever-menacing spectre. The constant fear lest some evil chance might tear him from the realisation of the one dream of his life made him very sure that he must run no risks.

As, in silence, too happy for speech, he drove the punt slowly homewards, past the long line of glittering barges, he made up his mind that to-night should see him call the last coup at roulette. Agnes had suggested that their life might be happier abroad, and with the coming of to-morrow he meant to definitely throw the sinister cloak of the old life from his shoulders.

He dined with Agnes at her hotel, and about nine o'clock, the hour usually agreed on for the gambling, set out for his own rooms.

He dined with Agnes at her hotel.

The sky had become overcast and threatening, it was surprisingly dark for the time of year, and as he paused on the steps of his lodging the lightning flickered behind the spires and towers of the colleges, and a deep growl of thunder ended with a sudden tempest of rain.

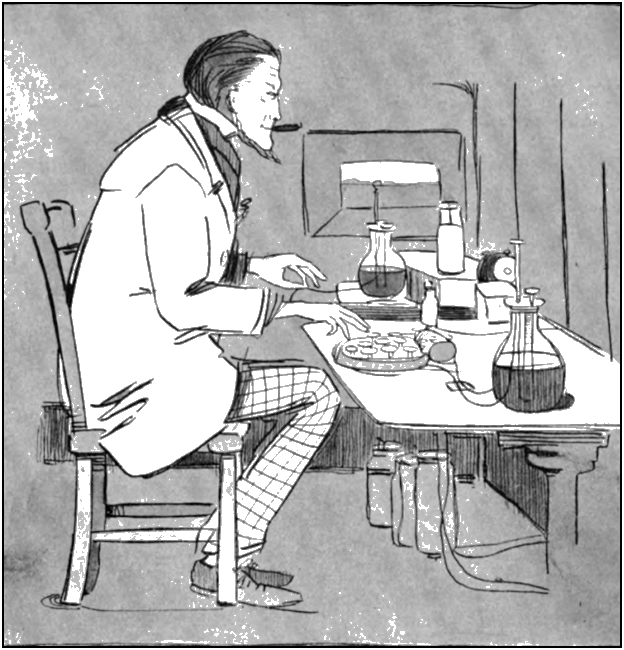

He passed upstairs, surmising from the empty dining-room that the play had already commenced. Coming to the door of the little room, where Heber Curtius played on the fatal wires, something drew him to visit the old man.

...played on the fatal wires.

He opened the door with his pass-key, and sat a few moments in silence, watching the puckered, observant eyes of the old gambler, and the ready fingers resting on the tiny key-board. The chatter of the players, and the monotonous clanking of coin came plainly through the slit in the wall. At intervals he heard the "Make your game!" and then the winning number called in John Curtius' hard, unsympathetic voice. The room was almost dark. Fear of detection forbade a light, but no blind shielded the window, and a street lamp lent a fitful glimmer. In the street below a few undergraduates, their gowns twisted about their necks, were hurrying home through the storm.

As Norrie looked down Broad Street, a great open flare of lightning rose up behind the buildings and seemed to stay there, burning like magnesian wire. Every detail of the room stood confessed. It seemed to Norrie like a forewarning of vengeance, a search-light sent from hell to make patent their sin. The old man whispered to him, "This is dangerous work on a night like this, Mr. Norrie. Try and get the game stopped early. I'm taking my life in my 'ands here."

Norrie went on tip-toe across the room, and, making a silent exit, entered with a forced hilarity among the gamblers. The scene was a mixture of gaiety and sadness. The boisterous good humour of Uncle Fiddeyment, and the easy bearing of those who had money to spend, and found this a pleasant way of spending it, were partly infectious. Many a young fool, who was busy throwing his life chances into the fire, roared a drunken appreciation of the old man's wit.

It seemed to Norrie, as he stood behind the players, that never before had he realised the utter sordidness of it all. The play was ruling higher than usual, and the gains of the bank were heavy. The boy at John's elbow, Norrie knew well, had sacrified all for the gambling. His lectures had been unattended, his books had lain untouched throughout the Term. The result of his final schools, on which depended his future livelihood, was horribly easy to guess. About the table sat other boys in like case. Again and again Norrie thanked heaven that to-morrow he left for London. He would take his winnings up to the present moment, withdraw his capital, and the Curtiuses might go on if they liked.

He felt a little afraid of announcing his withdrawal to John, and watched him apprehensively as he stood by the wheel, a sinister instrument of fate, joking harshly with some of the players. Outside, the wind screamed like the music of an orchestra of the damned, and there was continual slamming of the hall door as man after man availed himself of this genial haven. Among others came Caradoc Milnes and Cormorant, just arrived from town and clamouring for drink and play.

Norrie stood by the sideboard and assisted in the business of the whisky decanters and the syphons. As each hour chimed from the clock he felt the load lighten on his shoulders. At eleven o'clock he had become almost cheerful, knowing that in another hour the play must stop. He sat on a raised window seat, close by Cormorant, and chatted about London and the theatres.

About half-past eleven, a young man, who had always complained loudly of his losses, rose unsteadily to his feet and stood at John Curtius' elbow. Norrie watched him uneasily; he saw danger in the angry lines of his face.

Curtius turned to him.

"Had enough, Evers," he said, "why didn't you back that run?"

"Oh, damn you and your runs," the boy answered, "this board's uncanny, I can't play against it—why, look at the ball jumping. Oh, I say! look at it; it went in and came out again. I'll swear it did!" Norrie turned pale, and gripped the cushion of his seat; the slightest breath of suspicion terrified him. He hoped that Heber Curtius would hear, and have the sense to stop working the wires; several men were already looking into the wheel. They were talking, but the noise of the wind and the incessant thunder was so loud that their words did not reach him. The man who had spoken had drawn a little back, and was fumbling with his waistcoat pocket. Something glittered in his hand, and to Norrie's unspeakable horror he saw that it was a compass. He knew that if the wires were still in use the deception must be instantly detected, and, stumbling to the floor, he lurched across the room, meaning to simulate drunkenness and upset the roulette wheel. In the ensuing confusion he trusted to luck to conceal any apparatus.

Before he got near the table, he saw the boy's face light up and words shape on his lips. He quickened his step and shouted to divert attention, when the house shook as if it was the sport of an earthquake. There was a noise like the screaming of the wind through all the telegraph wires in the world, an unearthly glamour of light, and then the room was in darkness save where flames burst from the floor and the further wall. There was a horrible smell of burning flesh. The gamblers fought savagely to reach the door, and alone, unmoved, Uncle Fiddeyment sat on in his chair.

"There is plenty of time, Norrie," he said. "Do not risk your life at that door; look at Cormorant and Caradoc, I had thought better of them."

The fire was quickly subdued by the engines, and three charred bodies were carried out of the house. The boy with the compass, and the two Curtiuses had been struck dead by the lightning.

AftEr the funeral, Norrie left Oxford with Mrs. Wagstaffe, and

three days later they were married at a registry office in the

presence of Uncle Fiddeyment and Charles Cormorant, whose limp

had entirely left him, owing, he asserted, to being partially

struck by lightning.

Norrie lived happily with his wife for many years in the various continental cities of fashion, but he was never able to forget that fearful scene when he had stood on the brink of ruin, and the roulette wheel had in the very nick of time veritably called down fire from Heaven to silence the mouth of its accuser.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.