RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old boy's magazine cover

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an old boy's magazine cover

DINNERS in celebration, and at the conclusion, of football matches are, at the Universities, not infrequently calculated to inspire the temperance advocate with horror. When, by reason of the train service, one is compelled to dine at five, after having played football till four, one is very tired, and one is also very, very thirsty. Wherefore, as it is not good to slake an ungovernable thirst with Oxford champagne, the last half-hours on these occasions are undoubtedly festive. Then it is that the speeches are made.

A Cambridge College, celebrated no less for its excellence in field sports than for its habit of embracing the slightest opportunity for a display of conscientious hospitality, had that afternoon lost their annual Rugby football match to an equally celebrated College at Oxford. The rival teams were now improving the occasion in the dining-hall of an hotel. The necessary speechifying had apparently finished, and there remained a delightful twenty minutes in which one might pledge all in sight for every conceivable reason, when the Oxford Captain, a man with a clear-cut, sensitive face, very handsome, and surprisingly sober, rose to his feet.

"Gentlemen," he said, "you've not quite done with me yet; I've got one more toast—no heel-taps, mark you—to propose. I want you to drink to the health of Mr. Geoffrey Seaton, who has to-day done the College the honour of getting his international cap. And I may say, that though he was ploughed three times in smalls, took four shots at mods, and stands no earthly chance of ever getting through a final school at all, we all feel sure that however intoxicated he may be at present, it'll take a good many Welshmen to stop him on Saturday. Gentlemen, Mr. Seaton—Geoff, old chap, good luck."

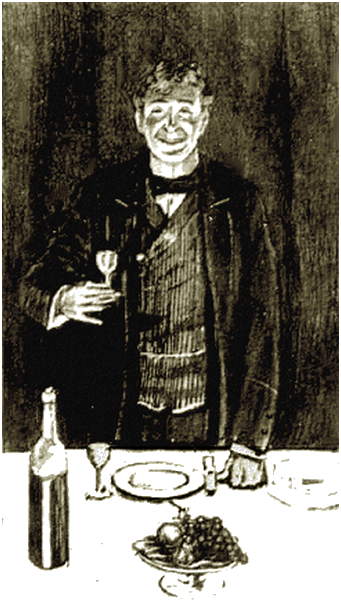

For some minutes there was indiscriminate noise, through which an expert in these gatherings could make out the semblance of the chant of "He's a jolly good fellow." When it was done, and the fallen heroes safely re-anchored in their chairs, the object of so much congratulatory uproar was pushed into an attitude that was upright in intention but somewhat lopsided in execution, and stood, six feet two of length by twelve stone six of good bone and muscle, swaying gently with a smile of supreme content. His seat was close to the curtained end of the room, and the bright light of the candles threw his face into a relief like that of an actor behind the footlights. The massive curve of his great shoulders was only dimly outlined against the sombre background.

"Thanks very much," he said, "I thank you all and I drink to you all, and if there was time, I'd drink with each one of you separately. And that, gentlemen, is all you will get out of me if you yell 'Speech! Speech!' till the trump of doom."

He stood for a minute, glass in air, beaming at the faces that laughed back at his—a genial and fascinating personality. Then he drained his glass, and, sitting down quickly, promptly replenished it.

He stood for a minute, glass in air.

A little clean-shaven, fat man, a light of the dramatic club, who made no secret of his intention to be one day a real actor, sang them the tale of the "Cobler's Sister of Bicester," and her amatory disasters. They all howled the chorus, and in the intervals of howling, drank heavily and with manifest enjoyment. A roar of general conversation followed the singing.

Fifteen young men from Cambridge and a like number from Oxford, all fresh from the public schools, have perforce many friends in common and much to say.

Seaton was thoroughly in his element as he leant back in his chair, chatting to the Cambridge men on either side, shouting an intermittent conversation with Pearce, the Oxford Captain, at the head of the table, and keeping up a running fire of chaff with every one else.

He was a very popular man, and he had that afternoon set the seal on his popularity by scoring as brilliant a try as the Parks had ever seen. Also, a telegram had come from the Rugby Union, according him his international Cap for the match against Wales, an honour which, in the opinion of Oxford, should have long since been his.

His parents were rich, and he was lounging happily through his undergraduate life, excelling in every outdoor sport, and receiving more invitations to dinners and wines for every night than he could possibly accept in a week. His ambition was to be at the top of the tree in every outdoor sport, and though he made no pretence at all to read, he was a general favourite with the Dons, who salved their consciences by regularly threatening to send him down, a threat which he knew perfectly well they would never put into execution.

It is not nice at seven o'clock in the evening to be compelled to break up a pleasant dinner, but the Great Western Railway waits for no man, and Dons at Cambridge are prone to regard the alleged missing of a train as an excuse for absence not above suspicion. It is even better to puncture your tyre, but in this case, do not, as the foolish, walk in the morning under the Dean's windows in a frock coat and top hat. Pearce, at last, aided by the Cambridge Captain, herded the diners, an unwilling flock, through the doors. Seaton had waited for him, and with one Howells-Martin, who completed a trio of fast friends, they walked together in to the hall of the hotel.

A girl was sitting in the window of the hotel office on the left—a pretty girl with masses of fluffy fair hair and a complexion that looked very brilliant over the white chiffon collar of her dress. She looked hard at Seaton, and coloured with pleasure as he crossed the hall to speak to her.

"Oh, Mr. Seaton," she said, "you've been taking too much again. I do hate to see it."

"Don't talk rot, Kitty; I'm as sober as a proctor in the morning,—I'll be back in an hour, and you'll see."

"I hope I shall," said the girl, with a little pout, as he hurried into the street, and swung himself into the waiting omnibus with a parting wave of the hand.

AFTER a commendable imitation of pandemonium on the platform,

and after Seaton had been with difficulty extracted from a saloon

carriage, through the window of which he had been loudly

proclaiming his intention to go and live at Cambridge for ever,

the train was started.

Pearce stood for a few moments with Seaton, whose cheers shook the roof, and watched it steam slowly round the curve till the flickering tail-lights disappeared into blackness. Then he took his arm. "Come on, old chap," he said, "and for heaven's sake shut your mouth. The proctor-men'll be here in a minute, they're dead keen to stop station-ragging."

Even as he spoke there came a vision of white ties in a doorway, and the majesty of the law, in the person of a little plump Don and three lusty henchmen walked in to the glare of the lights.

"This way," called Pearce, "down the subway," and he pulled Seaton after him. Martin followed, and in another minute all three were in the open air at the other side of the station.

"Lucky escape, Geoff," said Martin. "It would never have done for you to be progged again."

They walked up Queen Street, Seaton, who was quite drunk, singing the refrain of the "Cobbler's Sister" at the top of his voice.

At Carfax there was a great crowd, and as far as they could see, Corn Street, the High, and St. Aldate's were black with people.

"What's the fuss about?" said Martin.

"The Prince, of course," answered Pearce; "don't you remember he was to stop and dine in Oxford on his way back to town. You two had better come up to my rooms for a bit, we can come out later and see him go."

Pearce lived in New Inn Hall Street, and as they made their way there, jostling against the groups of undergraduates and townsmen, he had great difficulty in preventing Seaton, who was very much excited, from picking a quarrel with every man whom they met. It was a great relief to get out of the noise and riot of the town, and it was an additional relief to Pearce when at last he had got Seaton safely into his rooms. He was a difficult man to manage when in his cups, and another serious breach with the authorities would almost certainly have resulted in his being sent down. They sat down in the cushioned window-seat and let the cool night air play upon their faces. It was very quiet and still in the little side street, and the moon high in the sky cast sharp black shadows on the Union gardens below. Seaton was the first to move. "I must have another drink," he said, and lurched towards the table. Martin got up and going to a cupboard found a bottle of brandy and some glasses.

To Pearce, as he sat alone and watched the fine white glory of the moon, the conviction came, so suddenly that it was pain, that this life was very foul and ugly. He heard the swish of the syphon and Seaton's gurgle of content as he drained his glass, and turning back into the room, he saw Martin chuckling over some doubtful joke in a pink paper. Seaton and he had come up to Oxford together from the same public school, where they had been great friends, and the friendship had lost none of its warmth in the larger life of the University. Both were athletes and popular men, but while Seaton was content to make success in games the chief aim in his life, and to partake joyously in all the coarser pleasures that offered themselves, Pearce was cast in a finer mould, and often, after a night of drunken folly, something very like remorse would come to him in the morning. Martin was different, and though on the best of terms with the athletic set, took no part in games himself. He would often say that the duties of the croupier at roulette were sufficient physical exercise to keep him in thoroughly good condition. Instinctively a gambler and essentially a viveur he was a very well-known figure in the faster side of the University social life.

"You're a fool to get blind like this Geoff," said Pearce coming forward into the room. "You'll have to lie pretty low if you're going to be anything like fit for the Welsh match."

"Nonsense," was the answer. "You know I can stand a night like this five times a week if I like, or if you don't know you ought to by now."

"Oh, Seaton's all right," said Martin. "He's one of those lucky beggars who can run about a footer field like a racehorse, drink till all's blue, and wake up in the morning with an eye as bright as a girl of fifteen—wish I was myself."

"Well, I suppose you ought to know," said Pearce; "you're considered an authority on drink, aren't you? All I know is that I can't burn the candle at both ends myself, and I'm considered pretty strong."

"Oh, shut up preaching, Pearce," said Seaton, getting up from his chair with a yawn; "it doesn't suit you. Meanwhile let's make a move, if I stick here much longer I shall sleep."

"If you'll come into College, we shall find some roulette in Smith's rooms," said Martin.

"Oh, I don't feel like a gamble," said Pearce, "and I can't stand the sort of men you meet at Smith's. Lord knows where he picks 'em up. Let's go for a stroll."

As they went out of the house, a newsboy passed, displaying a large lettered contents bill—"Full account of the Prince's visit to Oxford."

"I'd forgotten all about it," said Pearce. "Come on, you men, we'll see him go."

As they passed out into Corn Street, they found that the noise of the streets had become very loud, and that there was a distinct note of anger in the shouting voices. Patrols of police were trying to keep order in the crowd, and mounted constables sat uneasily on their horses at every corner. They reached Carfax just in time to see a closed carriage drive quickly past and then the centre of the road that had been kept clear became at once alive with men. Left to itself the crowd of noisy undergraduates would have soon dispersed, but the large force of police that had been imported for the occasion made the error of mistaking a mere rowdy demonstration for a possible riot and were trying to deal with it as such.

"This will be serious in a minute or two," said Martin.

"Yes." answered Pearce under his breath. "Le Feore of the House told me there might be a bit of a rag. Let's get Seaton home or he'll commit a breach of the peace. Come on, Geoff," he went on aloud, "let's go and see Smith."

But Seaton was not to be persuaded. "I wouldn't miss such a chance of a rag for the world," he said; "this looks like being a rare old-fashioned town and gown. I'll come into the Clarendon for a drink, and then we'll go all round the town."

THEY made their way to the hotel with great difficulty and

stopped for a moment at the entrance of the courtyard, waiting

for an opportunity to gain the steps leading to the main door,

which were blocked by a dense crowd.

"If any more of these damned little townees run up against me, one of 'em will get a thick ear," said Seaton as he wrenched himself into the open space of the yard. As he spoke there was a shouted order and the mounted police began to trot their horses down the street. The crowd gave way on all sides and a gorgeous young haberdasher, who was clumsily rioting in joyous imagination that he was behaving like an undergraduate, was sent spinning across the pavement. He tripped across Seaton's leg, and recovering himself with an oath, struck violently with his stick at the latter's hat. The stick fell heavily across Seaton's eyes, half blinding him for the moment; then with a roar of anger he rushed at the young man and struck him repeatedly about the face and body with his clenched hands.

"Leave him alone, you fool, you'll kill the poor devil," shouted Pearce, struggling vainly to hold Seaton's arms.

Martin pushed the young tradesman aside, "Be off, you little fool, can't you see whom you're quarrelling with?" he said.

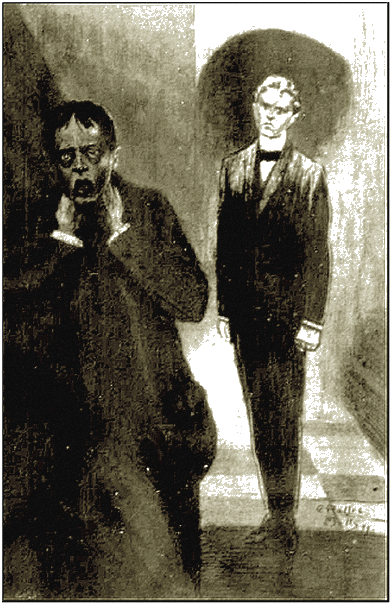

Mad with anger and with his face streaming with blood, the young man aimed another vicious blow with his stick, and then, turning, ran down the court. Seaton, in whom drink had excited a savage fury, totally at variance with his usual genial good-nature, tore himself from Pearce, and, catching the wretched young man in a few strides, jerked him round with his left hand while with his right he struck him very heavily on the apple of the throat. The young man staggered backwards, and putting his hands quickly to his neck, leant for a moment, almost still, against the wall, his eyes rolling slowly in their sockets. Then all at once his feet began to shuffle, and, tripping like a drunken man, he slipped clumsily to the ground and lay huddled on his side. The blood gurgled from his throat and spread in a thin lake over the flagstones.

Leant for a moment, almost still, against the wall.

The tide of riot rushed past and they were left to themselves in the little court. It was quite silent now but for the clatter of the dishes that the waiters were removing from the room where earlier that evening, they had dined so joyously. "Get Seaton away at once, into College, anywhere," said Martin; "I'll stay here."

WHEN he was alone, kneeling over the body, he felt with his

hand for the beating of the heart, but it needed no expert to

tell him that life in the huddled thing was extinct, and he

shuddered with a sick fear as he found himself for the first time

in his life face to face with death. He peered into the face, and

the skin, where it showed between the streaks and splashes of

blood, was white and drawn, while the wide open, staring eyes

were full of terror.

For several moments he knelt there, powerless to think or act, till suddenly the courtyard became all full of light. A waiter had come to the big window and drawn up the blind before closing the shutters. Martin heard him humming the refrain of "The Cobbler's Sister" as he stood fumbling with the bolts. All at once he realised the danger of his position and stumbled to his feet, his hand, as he raised himself, splashing into the pool of blood. Then, thrusting his dripping fingers deep into his pocket, he hurried out of the court.

The rioters had been cleared from that part of the town and there were but few people in the streets, but Martin read suspicion in every face that passed, and in his pocket his hand was damp and nerveless. The roar of the distant crowd that came to him over the house-tops seemed sinister and threatening; as he turned out of Corn Street, he was running quickly. Instinctively he had gone towards his own rooms, but the fear of being alone with his awful knowledge stopped him on the doorstep.

Noise, society, and drink he felt that he must have, and he remembered the roulette party in Smith's rooms.

The porter saluted him with a cheery good-night as he stepped through the little wicket in the College gate, and added. "Mr. Pearce, sir, told me to say that he was with Mr. Smith, and would you come up at once."

Smith lived high up in the further quadrangle, and as Martin climbed the stairs he could hear a noise of singing and the jingle of a vamping accompaniment. The room was crowded with men who had come for a gamble after the football dinner. The roulette wheel and the green cloths still lay on the table, but the game was over and the players were all standing and sitting round the piano, where a sandy-haired youth gave imitations of popular music-hall singers. Seaton, glass in hand, sat on the table, and his voice was loud and cheery as with closed eyes he bawled the choruses of the songs. Every one's back was turned to the door and Martin entered unnoticed. He crossed quickly to the bedroom, and, tearing off his coat, began to wash the bloodstains from his hand, scraping frantically at his fingers with pumice-stone.

Almost directly the door opened, and Pearce was beside him.

"I saw you come in," he said. "What's happened? Is the chap all right?"

"He's stone dead," answered Martin. "Oh my God, it was awful! I left him lying there. My hands are all covered with blood; do look at my coat, and see if there's any on the sleeve. It's that chap in Gaskell's shop—the tall one; I could only just recognise him. What does Seaton think? Does he think he only hurt the man, or what?"

"He's blind drunk now," said Pearce, "and doesn't remember anything. What on earth we ought to do, God only knows. Of course, it's manslaughter, if not worse. Do you think any one noticed?—did any one see you there?"

"A waiter came to the window, and I got frightened and cut," answered Martin. "But I don't think he saw me. Even if he did, my back was towards him, and he couldn't have recognised me. No one even passed by the court after you had gone. It's lucky we were dressed, and not wearing any colours."

"Every one knows Seaton," said Pearce. "If any one actually saw it done, he'll be arrested to-morrow; but there was such a riot that I really don't think that a soul knows but ourselves. We had better suppose so for the time, at any rate. Let's get Seaton to bed, and we'll talk the thing quietly over by ourselves. We must get some definite plan settled to-night. Put your coat on, and come out into the other room. I can't see any mark on the sleeve."

In the sitting-room, the singer had exhausted his reminiscences and the men had fallen into talk of the rioting, each trying to make prominent his own particular share in the adventures of the night.

"Never had such a time in my life," a fat, chubby-checked boy, who was very carefully dressed, was saying. "I couldn't stand the crowd—much too rough, and smelt awful—so we all went up to Parkhurst's rooms in Queen's, and squirted the 'Bobbies' like blazes with syphons—used about four dozen."

"Tubby would be safe," said a big man with a fair moustache; "he thoroughly understands the art of battle from a distance. I got left by myself, and had rather a thin time. I wanted some one like Geoff with me. By the way, Geoff, where did you get to? We lost you when the Proggins came. You seem to have been in the wars, too. Where did you get that black eye?"

"Some little brute of a counter-jumper swiped me with his stick," said Seaton. "I don't think he got much change out of it; I was damned drunk, but I remember hitting him pretty hard. Old Pearce took me away—he's been watching me like a mother all the evening."

"I'm going to take you away once more," said Pearce. "It's getting on for twelve now, and you've got a good way to go."

The clock struck the quarter as he spoke, and most of the party got up, and began searching for caps and gowns. Martin found Seaton's, and with several other men they groped their way down the dark staircase into the quadrangle.

"That blasted porter's been pretty sharp with the lights to-night," said Seaton, as he stumbled at last on to the gravel. "If some one gets killed on these stairs, he ought to swing for murder. Good night, Smith," he shouted up to the window. "Don't forget lunch to-morrow."

The porch was very full of men, entering and leaving the College, and congratulations to Seaton were shouted from all sides as they passed out of the gate.

Seaton lived in Wellington Square, and during the ten minutes of their walk no word was spoken by either of the men. They got him quickly to bed, and, leaving him sleeping quite peacefully, were soon back at Pearce's door in New Inn Hall Street. Martin lived on a lower floor of the same house, and after delaying for a moment to open some letters, he followed Pearce upstairs.

About four o'clock they went to bed, having decided that, till the morning brought them news of what was known, no definite plans could be made. They lingered in silence for a moment on the staircase, and shook hands as they said good night—a thing they had never done before, save at the beginning and end of a term. The common possession of this dreadful secret seemed to make the friendship of the two men a deeper and more serious thing.

THEY breakfasted together early, and began to anxiously turn

over the pages of the different London papers that they had

ordered. The visit of the Prince was dealt with at length in each

instance, but the subsequent rioting was disposed of in a few

words.

"Here it is," said Pearce. "Thank Heaven they don't know anything yet. It just says that a young tradesman was found dead near the 'Clarendon.' We shall have to wait for the afternoon's Review for anything more. I wonder if the police suspect any foul play. It must have been so obvious that the man was killed by a blow struck in anger."

"Whatever they think or do," said Martin, "we've got to go and tell Seaton at once; I wonder how on earth he'll take it."

They had to pass Gaskell's shop on their way, and the proprietor, who knew them, and was standing in the doorway, began to talk about his assistant's death. He had been told early that morning, and had already seen the dead body at the Town Hall, and called on the young man's mother. He was very much distressed, and talked excitedly of the prompt measures that were being taken to discover the murderer.

The horror of their situation was painfully increased by the shopkeeper's story, and their hearts sank as they entered Seaton's sitting room.

Breakfast had not yet been brought up, but sounds of footsteps in the bedroom told them that he was dressing.

"Come in, you men, whoever you are," came in genial tones from within; "I shall be ready in a minute."

"Come in, you men, whoever you are."

They went in, and found Seaton, who had just finished his bath, swinging a pair of Indian clubs which he manipulated with an easy grace. He was dressed only in a pair of flannel trousers, and the shapely curves of his shoulders and great muscles of his arms gleamed white in the sun that streamed through the window. His eye shone joyously and his fingers closed tight and firm on the clubs that circled rhythmically round his head.

"What's the row?" he said, catching sight of the two men. "What are you pulling those long faces for? Come to tell me that I mustn't get blind if I want to play footer, I suppose. Well, I'm going to be very good till after the match. Get yourselves drinks and buck up, you haven't got to train—well, I know Martin will, if you won't, Pearce."

He put down the clubs with a bang, and slipping on a thick sweater, opened the door and shouted for breakfast.

Five minutes later he was swallowing the kidneys and bacon as if nothing stronger than milk and soda had passed his lips on the evening before.

"Geoff," said Pearce suddenly, "do you remember the fight you had last night?"

"Rather," said Seaton; "look at the bruise over my eye. I knocked the man about a bit, didn't I?—I remember you pulled me away."

"You killed him," said Pearce.

"Killed him, don't talk rot," said Seaton.

"The man died almost at once," said Martin, "I was with him. It's in all the papers this morning, but at present no one but ourselves knows who did it; we've come to talk it over with you."

Seaton was silent for a moment, then broke into a loud, harsh laugh. "Serve the beggar right," he said; "I hope it'll be a lesson to some of his friends."

"Good God, man, don't laugh," said Pearce, "don't you realise the awful thing you've done? Don't you know it's manslaughter or perhaps murder, and prison and ruin for you if you're found out?"

"I shan't be found out," said Seaton. "You say that only you two know, and you won't give me away. I'm sure no one else would ever suspect me of being a murderer. If the man had a wife or a mother or any one to support, they can be compensated anonymously. I don't mind paying."

"I'm damned if I listen to talk like that," said Pearce, getting up from his chair. "Simply through your cursed drunkenness, you've killed a fellow-creature and caused God knows what misery, and you sit there and laugh and talk about paying as if you'd broken a window. Think of your own mother—and your girl. Oh, it's horrible, too horrible for words. I'm going; come along, Martin. If you get into a more decent state of mind, you'll find us in College."

When Seaton was alone, he sat for a long time at the table, tapping nervously with his fork on a plate. The piece of kidney which he had been raising to his mouth when Pearce blurted out the news was still stuck on the prongs, and intently he watched it grow stiff and wrinkle. He found it very hard to think calmly. He could only stare uneasily at the familiar things in the room while a jumble of thoughts raced through his brain, leaving an impression of vague, uncertain terror. What Pearce had told him seemed so utterly incredible. He could not bring himself to believe that he to whom life had hitherto been so pleasant a journey could really be a criminal wanted by the police. Curiously enough no sense of remorse entered his mind, his mood was wholly one of wild, unreasoning anger against the ill-luck that had brought him into this dangerous position.

He cursed aloud, the words coming jerkily from his lips; and he was relieved as his voice broke the oppressive silence. Martin's glass, filled with brandy and soda, stood where he had left it untasted on the table, and as Seaton drained it the warm glow of the spirit in his throat brought back to him the power of reasoning and thought. It was extraordinary. This man, whose kindly and generous good nature had so endeared him to all is friends, became, under the influence of the first real trouble that had crossed his life, hard and callous. He felt that the world which had been so kind to him was now in a sense his enemy, and a look of bitter resentment and cunning came into his eyes. He felt able to think now, and walking quickly up and down the room, he made his plans for the future. He realised that in the scuffle of the riot it was extremely unlikely that any one but Martin and Pearce should have seen the thing done, and he felt quite sure that however great their horror at his deed, he was quite safe from any possibility of arrest through their agency. It was now Thursday, and the Welsh match was to be played at Cardiff on the Saturday. He had arranged to go down on Friday evening with a man from Birmingham who was also playing. Martin and Pearce had decided to go with them, and after the match they were going on to Hereford to stay with Martin's uncle, to whose daughter Seaton was engaged to be married. They were to come back to Oxford on the Monday. He wondered if they would come with him now. He felt quite sure that Martin would not tell his cousin, and he was confident that the girl loved him far too well to be persuaded into breaking off the engagement for no definite reason.

He felt so sure of his safety that he laughed again, and went into his bedroom to finish his dressing.

A MAN who lived in the next house, and who was training for

the 'Varsity sports, came in and suggested that they should walk

together to Shotover; and almost immediately they started. They

lunched quietly at a country inn, and it was dusk before they

came back over Magdalen Bridge into the High Street.

The newsboys were shouting in noisy groups round the College gates, selling many copies of the Review to the men who passed in and out.

Seaton had almost forgotten the occurrence of the night before, in the pleasure of the quick walk and the joyous feeling of absolute health and strength. Even now he found it hard to bring to mind any details of his drunken fight, and the whole thing seemed to him like the misty remembrance of a bad dream that he had had many nights ago. He bought a paper, and then, as his eye caught the heading, "Shocking Fatality during the Rioting.—Suspected Foul Play," all his earlier anger and resentment against his ill-luck came back to him. The man he had been with all day had gone early to bed the night before, and knew nothing of the disturbances in the streets, or the death of Gaskell's assistant. Their talk had been entirely confined to athletic matters, and Seaton felt that he could not bear to spend the evening among men who would be certain to discuss and speculate about the murder.

His companion solved the difficulty.

"Come back and feed with me in my digs," he said. "You won't mind a training dinner, will you? And we'll both get to bed early."

Seaton looked into his own rooms on the way, and found a note from Martin.

"Dear Geoff," ran the letter,

"I do hope that by now you have come to a better state of mind. Of course, you must have been a little insane for the moment, to have behaved as you did this morning. Preaching comes ill from my lips, but I feel I must say quite plainly that your way of taking the whole horrible affair has disgusted both Pearce and myself. But we can talk it over at Cardiff. If I don't see you before, I will meet you at the station, as we had arranged.

"Yours, W. H. M."

He threw the letter angrily into the fire, and went to his

friend's room to dine. After the meal, excusing himself on the

score of training, he went home early to his rooms, and sat

thinking. This great handsome fool was conscious of no emotion

but a sulky impatience at the chance of fortune. He was bitterly

angry with the circumstances that had brought the affair about,

but there was no single trace of sorrow in his coarse, dull

brain.

LIFE had always been so singularly smooth to this man, all his

material wants had been so abundantly satisfied that he had

become little more than a great muscle. His usual jolly, careless

temperament was simply the result of perfect health and smiling

fortunes; and this sudden blow showed him what he was—a man

whose body had killed his brain, a creature whose blood was too

thick and rich, an example of that "healthy devotion to athletic

sports" which, while it certainly produces a giant, unfortunately

often insists that he shall be a fool.

In the morning he went down to Cardiff by himself in a cruel and evil temper. He did not want the companionship of his friends. In the afternoon he walked to Penarth and sat on the sea front, and the fresh, cold wind from the Channel blew the gloom from his mind for a time.

When he got back to the Queen's Hotel, he found that the English Committee and most of the team had arrived; and an hour later, as they were sitting down to dinner, Pearce and Martin walked into the coffee-room.

Dinner was a pleasant meal, and in the excitement of meeting so many friends Seaton became his old genial self once more. They all sat on after the table had been cleared, and the talk ran incessantly on football, and the prospects of the next day's match. It was a conversation of experts, sharp, clipped, and allusive; and to a man who knew nothing of the game, the talk that aroused so deep an interest in every one present would have seemed a meaningless jargon. In such a gathering Seaton was at his best; there was little present to remind him of Oxford, for Martin, who abhorred football shop, had taken Pearce to the billiard-room. The grim vision of the dead man in the Clarendon yard was chased from his mind by the all-important consideration of football matters, and, in tale and jest, of matches lost and won, he held his own with them all.

AS he walked on to the field next day, the roar of applause

that greeted the English team roused all his old lust of combat

and pride of strength. He started with some of the men to run

down the field, and pass the ball to each other; and the spring

of the turf, and the absolute freedom of his football clothes,

made the blood burn in his veins. There was a high wind that

bugled as it rushed through the trees at the other end of the

ground, and he stopped and sniffed it joyously, as he threw out

his chest and braced his muscles.

A man in the crowd who knew him shouted some words of encouragement, and Seaton waved his hand genially. He felt that at last he was his own man again.

The game was hard fought, and Seaton was conspicuous by the daring and roughness of his play. The vigour of his tackling cost Wales the services of a half-back early in the game; and when, shortly before the end, he followed up his own kick, and threw the full-back so violently that his shoulder was broken, he was cautioned by the referee, while hissing from the crowd was plainly audible.

It was left to him to win the game, for when England were one point behind, and there was but little time left for play, the Welsh backs started a round of passing when close to their own goal; and Seaton, intercepting a wild throw, ran round behind the goalposts. The cheers that greeted the try were mingled with groans, for the violence of his play had made him very unpopular with the crowd; and as he lay where he had fallen with the ball, close to the barrier, a burly collier from Llanelly leant over the railings, and, shaking his fist at him, cursed him vigorously.

The hostility of the crowd was again apparent when, some minutes later, the victorious fifteen left the ground, and the other players were at some pains to protect Seaton from its violence.

The exhilaration of the game, in which he had used his vast strength so freely, had brought Seaton to a more equable temper. This great dull animal required just such a violent tonic to subdue the sulky fever in his brain. As, like some huge broad-flanked bull, he had charged his opponents, or thundered away from them on the sodden turf, the body that he loved so well had, in its own fatigue, brought rest to his brain also.

HE enjoyed the dinner in the evening, and when, full of meat

and wine, and an insolent joy in his own prowess, he walked out

into the streets, one saw what an absolute cad the fellow

was.

His manner was abominable. He would roughly elbow men from the pavement, and stare intently at any girl that passed, displaying, to his own and his friends' perfect complacency, the sight of a drunken and boorish young man, with the strength of a Hercules and the conceit of a chorus girl who has managed to marry a gentleman's son. In this mood, together with one or two of the Welsh team—thick-set men with clear eyes and a beautifully-poised walk—he paraded the lighted streets of the town. His swaggering carriage and clumsy jests upon the passers-by delighted his Welsh friends, who emulated him in the foulness of his remarks, and punctuated each dirty little witticism with bursts of falsetto laughter.

They went into several public-houses, and in one of them found a knot of low-browed, evil-looking men discussing the match of the day. Seaton, as he swaggered in, was immediately recognised, and the men began to jeer among each other. At last one of them—a big, black-browed rogue, egged on by his companions—stepped out from among them, and, winking them to observe what he should do, looked Seaton up and down with a grotesque imitation of the other's manner.

"'Ullo, mister, sir!" he said, amid roars of approving laughter. "Look 'ere, young fellow-my-lad, a bit of stick over your snitch 'ud do you no 'arm."

Seaton, who was drinking at the time, looked at his adversary, and, putting down his tankard, flung a black insult at him with a vulgar jeer, and then, throwing back his head, laughed long and loud.

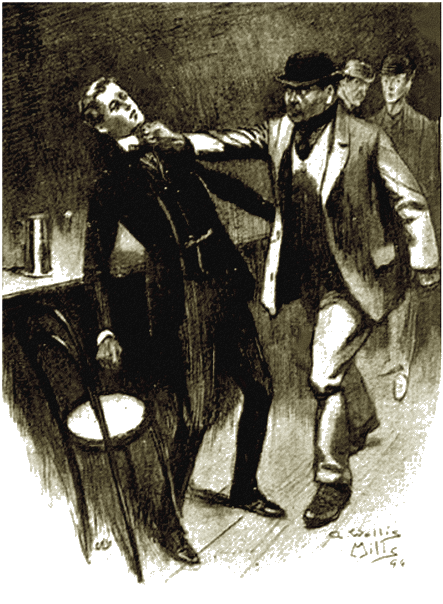

The man trembled with rage for a moment, and then swiftly struck him a crushing blow right on the apple of the throat.

Struck him a crushing blow.

Seaton went down, limp, like a sack of wet grain. He was perfectly conscious, and his eyes were open, showing him a ring of red and terror-stricken faces. He could hear nothing whatever, and the silence was as intense as in some deep tomb. His brain alone retained the memory and sound of the man's last words. He felt no pain at first, until suddenly he became conscious of a bitter, warm taste welling up in his mouth, and knew that blood was pouring from it. Then cruel fingers of steel seemed to gripe the apple of his throat, and crush it into pulp. The agony was fearful, and all the time he could think. Then there was a rapid sensation of suffocation, and as he felt his heart running down, and his brain working irregularly with clicks and stoppages, he remembered the night in Oxford with singular and vivid distinctness, and knew that he himself was dying as his own victim had died. The agony came to him in great spasms, and he knew, with clear distinctness, that in a minute he would be dead. He could not fight against the tightening finger on his throat. Then his pain went suddenly, and the room flashed away from him, and instead he saw, within a yard of his own face, the white visage of a young man with sandy whiskers. The mouth was twisted into a grin, the eyes were open and protruding, and blood was coming from them. Then came darkness, and an intense, numbing cold, through which he could hear the voices of the crowd quite distinctly, though they seemed very far away.

He felt as though he was dropping rapidly through many waters, and as his life died out, like the glow from an incandescent wire, he could still hear little voices in the dark.

Then came silence.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.