RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

BOUT a year ago most of the Parisian newspapers contained an obituary notice of Paul Vavin, the art critic. In the places where people talked about art—indeed, in all the côteries which prided themselves on being a little more cultured than their neighbours—his name and work were known. He had more or less, one might say, invented a new attitude towards pictorial art.

His writings were quite ephemeral, and even now are forgotten; but he had a success of novelty which extended over some months; and a year ago, when he died at Envermeau, his decease excited considerable comment.

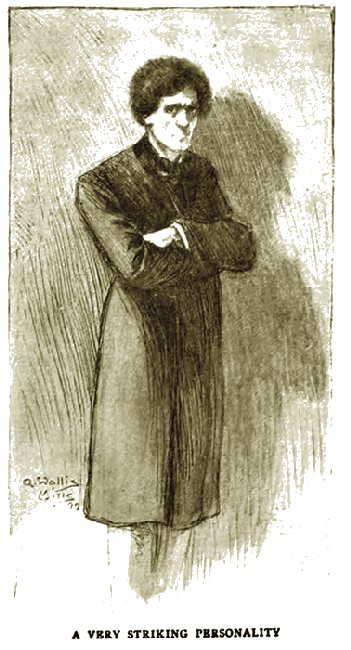

A very striking personality had possibly something to do with this: for by his personality, even more than by his writings, Vavin had made his impression in Paris. The photographs that were published in several illustrated papers at the time of his death gave no true idea of his appearance. He was one of those people who, to use the slang of the dark room, "do not take well," and his portraits were always egregious failures. His figure was well known upon the Boulevards. Despite a distinct stoop, he still looked very tall, his great emaciation doubtless adding to the impression. His face was long and thin, and of an extreme pallor, and there was something repulsive in the hard line of his almost lipless mouth and the undue prominence of his lower jaw. His masses of curly black hair—hair in which there was something irresistibly suggestive of negro blood—only served to accentuate the unhealthy paleness of his complexion. His eyes gave more index to his character and habits of life than did any other feature.

They were large and dark, reminding one of pieces of black glass, and, generally, they were dull and lifeless to a degree that was unnatural. At rare moments they blazed into a light that pointed to but one estimate of his mental condition. In fact, a few weeks before he died his friends and intimates perceived that his continued debaucheries were at last having an abnormal effect upon his temperament. His writing became more fantastic in its views; and the ugly, the grotesque, and the wicked in art began to throw him into that terrible dream glamoui which fascinates and possesses so many of the younger generation in France. Vavin was no more evil in is life than most of his contemporaries, and no more distinguished in his work. He was a type of the character that results from a morbid and vicious life; and it is only the facts attending his death, which he desired should be made public, that invest him with more interest than twenty other young Parisian decadents one could name.

That he was sincerely, truly penitent, Father Gougi (through whose instrumentality the facts have been made public) vouched for; and though the ordinary man cannot but regard such a sudden, death-bed repentance with some suspicion, the wish that the incidents of Envermeau should be told to his friends seems to point to some spirit of contrition. The horror of such a life as Vavin led was well matched by the horror of what he saw before he quitted it; for, living an abnormal life, his punishment also was abnormal.

Whether he really saw what he professed to see, or whether his shattered nerves merely presented to his brain a terror which had no existence, it is not within the province of this account to decide. In either case the warning is as strenuous. It is sufficient to say that the story has had the effect of pulling up at least one young French writer, who was rapidly travelling on the way which would have led him to a frightful insanity and a lingering death.

Paul Vavin, at the time the following events occurred, was in the full enjoyment of an easily-earned celebrity. He wrote on art matters for several newspapers; and in his criticisms he found, or professed to find, some fantastic and grotesque meaning in nearly all the work which he reviewed.

This, of itself, would not have been sufficient to command success if it had not been that there was undeniably something in his writings which succeeded in giving the people who read them an uneasy feeling that he might possibly be right. When he found an ugly meaning in a beautiful thing, he was clever enough to invest this theory with some probability; and he accordingly found some fame, and a great deal of money, in providing Parisians with a new sensation. He taught them, in fact, to imagine corruptness. The money he earned at his trade he spent in every vicious indulgence.

ONE morning in the summer of '97 he went to the offices of a

newspaper for which he did a great deal of work, to decide with

the editor the subject of his next article. It was about the time

that the poster, as an artistic factor in modern life, had become

generally recognised. M. Lautrec in France, and the Beggarstaffs

in England, had conclusively proved to the public that the poster

was to be regarded as a serious endeavour, and all Paris was

interested in the subject of "Affiches." Just at the moment two

artists—who worked together in much the same way as Messrs.

Pryde and Nicholson—had achieved an extraordinary and

triumphant success. Beaugerac and Stein—for those were the

names of the two artists—had made an enormous sensation.

Discarding the many-coloured posters of most of their co-workers,

they drew only in sombre tints, and with he utmost economy of

means. Their posters did not attempt to be pictures, or anything

like pictures, and at once the public saw that they were good

posters. Stein and Beaugerac neither painted nor drew: they

"arranged masses"—that was all.

Strangely enough no journal had as yet been able to obtain an interview with these two men, who consistently declined publicity. It was known that they lived and worked somewhere near the great forest of Arques in Normandy, but that was all. Their views on artistic matters could only be guessed at by their work. Vavin himself had written one or two highly eulogistic notices of their productions, in which he had succeeded in finding out nothing of their personal opinions, and they had declined several requests for interviews. On this particular morning, however, the editor cf Le Vrai Salon informed him that he had received a letter from Stein which at last acceded to his proposals for an interview, and which asked that M. Vavin, in preference to any other critic, should be sent to visit them.

"Will you undertake this?" he said to him. "The opportunity is one which will not occur again, and will give you the chance of turning out an article which will be very widely read and commented upon. I need hardly say that I am excessively pleased at our success."

"Certainly I will go," said Vavin; "nothing will please me better. But, nom d'une pipe! where in France is Envermeau?"

"Envermeau," said the editor, "is a village in Normandy, on the edge of the forest of Arques. It is eight or nine miles inland from Dieppe, and to get there, as far as I can find out, your best way will be to go straight to Dieppe, and then drive to the village. The name of the house is 'Le Maison Noir.'"

"I go," said Vavin, "to-morrow. Today I drink. Come now to Père Santerey's and taste absinthe, my friend. All Paris is abroad, and if the nasty yellow sun were put out and the gas lamps lit, I should be even happy. But come—buvons!—déjeuner will be the better for it."

THEY went out together into the glorious sunshine, and sat for

an hour under the awning of the Café Llamy, just opposite the

great gate of the Louvre. The watering´-carts had laid all the

dust on the white roads, and, despite the sun, the air was

delightfully fresh and cool and alive with musical sounds. The

little boys with their long-drawn shouts of "La Presse! La

Presse!" the merry beat of drams as a company of little blue

soldiers went marching by, the tinkling of the ice in the flagons

of amber- and honey-coloured beer, all went to make up a

mise-en-scène that had a most gay and joyous influence. M.

Varnier, the editor, was a man peculiarly alive to the promptings

of colour and sound, and he leant back in his little chair

smoking his Caporal and drinking his beer, intensely

enjoying this moment of physical ease.

Vavin looked ghastly in the bright daylight. He resembled some figure at a bal masqué, which should only be seen in artificial radiances. As he talked extravagantly to the editor, waving his long bony hands to emphasise his remarks, he attracted a good deal of attention, and his cup of happiness was full when he heard a man, who had come out of the big Magazin du Louvre opposite, say to his wife: "Look! there's Paul Vavin."

After a time, Varnier went away to déjeuner, leaving Vavin, who could not eat, alone. He sat there for another hour, drinking without cessation, and then, his potations having induced in him for an hour or two something almost like the energy of an ordinary man, set out for the Boulevard, where he should see his friends and exchange some of the gossip of the day.

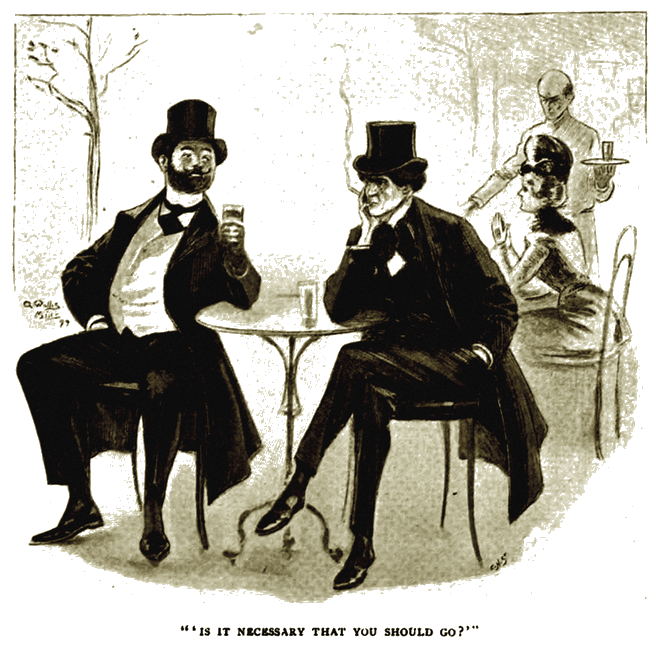

THE first person he met was Dotricourt, the perfect

boulevardier. Dotricourt was said, in Paris, to be the absolute

type of the flaneur. He had brought lounging to a fine

art, and, fortunately possessed of a moderate income, he loafed

happily through life. His knowledge of every one who had done

anything was extensive and valuable.

He could tell you something of almost anyone about whom you might be seeking information, and to the journalists of Paris he was a constant and never-failing resource. A creature of good nature and bad company, he was absolutely free from prejudice, and all the time he could spare from the study of life he spent in neglecting its obligations. Withal, although he had never been heard to say a good thing of anyone, he had never been known to do anyone any harm. He himself, when taxed with his omissions or the futility of a method of life which, while it annoyed others, certainly pleased himself, would bow and say, "Je suis Dotricourt—flaneur!" and consider that the discussion was at an end. Vavin saw his fat little figure standing by a kiosk on the pavement, talking to the girl who was selling newspapers.

When they were seated at the café, Vavin told Dotricourt of his mission the next day, and asked him if he knew anything of Beaugerac or Stein, who they were, and what manner of life they lived. The flaneur looked curiously at the other before he made any reply.

"Is it necessary that you should go?" he said.

"Yes, I must go; the opportunity is too good to be missed. I shall entirely hold the field. It is naturally a nuisance. But why do you ask that?"

"Well, I wouldn't go; that is all," said Dotricourt.

"You are talking in riddles, and the Boulevard is no place for sphinxes. Tell me what you mean."

"If I did you would only laugh. I have the greatest reluctance to tell you, owing to the way the information came into my hands. I must beg of you not to press me."

"But, my friend, this is unfair. You solemnly warn me against my proposed journey and then leave me in doubt and suspense as to what you mean. I really must insist on knowing."

"Soit," said Dotricourt, "I will tell you; and with a quick glance round he leant forward and whispered in the other's ear. Vavin started, and quickly made the sign of the cross. Then he emptied his glass and began to laugh.

"Poof!" said he, throwing out his right hand. "Look at the son; listen to the people of Paris. Can you and I believe the things in the Paris of to-day? Bah! leave such imaginations to the priests who invented the devil, and Huysman who invented his worship. We are not on the level cf those little journals written for cocottes who love to fill their empty little heads with horror. We are men. Louis, two coffees, and bring me the brandy in the bottle."

He leant back laughing loudly, an unpleasant sight, with his long pale face and wicked mouth. Dotricourt shrugged his shoulders.

"As you will, Paul," he said, "for my part, though, I do not think about things which appear incredible; I am wise enough to allow that they may possibly exist. But, as you say, we are men; Paris is here, let us enjoy it, you and I. You do not start till to-morrow, you say?—good. To-night we will be merry with some friends of mine in the Quartier, who after three years of penury nave sold a picture well and are giving a feast to all the world. There will be Filles d'Angleterre and Grogs américaines. Shall it be so?"

"Parfaitement," said Vavin, giving the true Boulevard twang to that useful and long-suffering word, and about nine o'clock they went to the feast, which by midnight degenerated into the usual orgy of the Quartier Latin. It was the last time Vavin degraded himself in this world.

ABOUT midday next morning, ill and tremulous, he took the

train for Dieppe.

It was a perfect day for a journey—serene and sunny, a day in which the blood raced in one's veins from the pure joy of living in a beautiful world. The sky was like a great hollow turquoise, and all along the line the sweet cider-orchards of Normandy were a mass of pink and cream colour. Vavin noticed none of these things. He was reading some abominable little gutter-rag, and as far as his throbbing nerves and aching head would allow him, he enjoyed its scurrility. He rolled and smoked innumerable cigarettes of black tobacco, inhaling the smoke deep into his craving lungs, and from time to time drank some cognac from a flask. There was something peculiarly revolting in the fellow, and he seemed a blot on the beautiful day God was giving to France.

As they left Rouen, and the giant spire of the cathedral flashed away behind, stark in the warm sky, his head sank on his breast, his lower jaw dropped, and he fell into an uneasy sleep. He was awakened at Dieppe by the stopping of the train and the invigorating sea air upon his face.

He determined that he would wait an hour or two, before he drove to Envermeau, and see what celebrities were on the Plage or in the Casino. Dieppe was alive with gaiety and colour, and the Casino Terrace was crowded with well-dressed people of different nationalities. Down below, the green sea with its pearl and yellow lights leapt under the slanting sun-rays. Everything was gay and delightful, for every effort of Nature and Art combined to make it so. There was a good band playing on the Terrace, and as Vavin sat there idly, feeling the better for his sleep, his sluggish blood began to stir within him and something of the light-heartedness that was in the very air entered into him also.

The light was very long and the sweet melancholy of a summer's evening was stealing over land and sea when he got into a carriage and slowly mounted the steep hill past the Octroi station, which was surrounded with market-carts full of the produce of the countryside. He cursed his luck as the carriage came out into the long high road. He would much rather have been in Dieppe and spent a bright evening in the Casino, where there was a dance, or sitting in the Café des Tribunaux with some congenial friend. The peace of the woods and fields found no echo in his heart, and the delicate sound of the breeze, as it rustled among the quivering leaves of the roadside poplar trees, fell on his ears with no meaning.

He had not always been so. In his early youth he had listened to the voices of wood and hill and torrent and found some responsive echo in his own heart. He had known something of the poetry of life when he was a boy. But Paris, with its life full of evil sensation, and a strenuous greediness after every material pleasure, had killed his delicate emotions, and as he rode towards his death Nature's last message came to him unheeded. As, in a dull and petulant mood, he sat in the carriage, he was a striking example of the mere "folly" of debauchery. When he arrived at last at the little village of Envermeau he stopped at the cabaret the "Pannier d'Or," and inquired about the road to the Maison Noir. The house, the landlord told him, was on the very outskirts of the wood, and there was no road to it that a carriage could traverse.

It was, however, added the patron, an easy way, and Jean the stable-boy could carry his bag if he intended to stop there for the night. Vavin had been proffered the hospitality of a bed by the artists in the letter they had written to Varnier, and accepting the offer of a porter he stepped into the inn and ordered a cognac. He sat there for a few minutes smoking a cigarette, and he noticed that the inmates of the house seemed to be in some trouble.

The landlord's face was white and drawn, with the look of one who had not slept, and the eyes of his wife, a buxom Norman girl, were red with weeping. The few peasants who were in the place, drinking a rummer of beer after their work in the fields was done, talked in subdued tones, and now and again ventured a word of sympathy to the host and his wife. An air of gloom and also of expectation seemed to hang over the place, and every chance foot-step on the road outside attracted instant attention. At last a firm tread was heard upon the flags, mingled with the clank of metal against stone, and the village gendarme entered.

"Ah, Pierre!" said the woman with a catching of the breath. "You have heard something, have you not? You have found her? Tell me you have!"

"No, Marie," said the man, "not yet, I do not know anything yet; but courage! They are all out on the countryside. They will find her by night; no harm can come to her. The little one is asleep in the wood, that is all, and our Good Lady will watch over her tenderly, you may be sure. She is certain to do it—our Lady. Père Gougi is even now upon his knees in church, and you know he has great influence with the Blessed Dame. So courage, Marie and Michel! I will find your little Cerisette before moonrise. Even now they may have found her—all the boys are beating through the wood. How we shall all laugh to-night, shall we not? It will be a good excuse for a carouse. Au revoir!" And, twirling his heavy moustache and throwing back his head with a confident gesture, the worthy fellow clanked out into the street. His firm and cheery voice, and the official air which his uniform gave to his utterances, had a reassuring effect upon every one.

"Eh bien, c¸a ira," said one rustic to another, "Pierre will find little Cerisette, he has a wonderful mind. What he does not know I would not give a dried apple for. He is bon garc¸e;on is Pierre."

The sorrowful mother herself seemed a little comforted, and Michel turned to Vavin and said:

"Ah, yes, m'sieu, we shall find her soon if Father Gougi prays for her; it will be all quite right soon, only, m'sieu, you may conceive that we are a trifle disturbed. Our little girl is only three years old, and it's a bad thinking to know the poor little mite has lost herself with evening falling."

Vavin was rather touched, a sensation that surprised him as it came.

"Oh. you will find little Cerisette tonight," he said kindly, "and look you, to-morrow I will come and make her acquaintance with a handful of bonbons, and then she will not be frightened by my ugly face. And now give me a stable-lad to lead me to the Maison Noir, for it grows late, and before dark I must be there. Good-night and good fortune; the angels will watch over Cerisette."

HE went out into the street with something like tenderness in

his heart; and the simple love of the peasant and his wife, and

their belief that the Mother of God would keep watch and ward

over the little wandering child brought a mist before the eyes of

the boulevardier. One is glad now to think that he was a little

touched. He walked down the village street with the stable-lad

trudging by his side, and, as they passed the church, the

curé came out, a kindly and venerable old man, and bowed

politely to the stranger.

The way went past the village mill, over a little bridge leading to the cornfields which skirted the wood, which was beginning to show black against the rosy western sky.

"Is it far?" Vavin asked the guide.

"But some fifteen minutes from here," said the boy. "Monsieur will not be in the least fatigued. The châlet is on the edge of the wood."

"And what are they like, the artist gentlemen who live there?"

"I have never seen them," said the boy, "but they do not come 10 mass, and they do say in the village that there is something strange about them. There it a big one and a little one, and M. Michel says that the big one is like Satan himself. But I do not believe him. M. Michel is a stay-at-home and does not know about things. I have been to Rouen and he never has, and I have been up the tower of the cathedral and seen the figure of Jeanne d'Arc in the market-place. I am very experienced, m'sieu. I think it is foolish to believe all that one hears. I never do it, I would rather see for myself."

As he spoke they came upon a small common, dotted with furze and leading to the edge of the wood. In the fading light Vavin could see a tall house, surrounded by walls, some four hundred yards away.

"Is that the place?" he enquired.

"That is it, monsieur."

"Then I will trouble you no longer. Give me the bag. Here is a five-franc piece for you; remember what you have told me. Take nothing on the evidence of other people. Trust nobody but yourself. It is the only way. Good-night."

The lad took the coin with profuse thanks, and, with a genial "Dormez bien," went back away through the fields. Vavin could hear him singing as he went. Then, while he drew near the house, the world grew silent as the night crept upon it. In the wood an owl hooted and a fox gave tongue, but the sounds seemed to be outside the stillness and unable to break it. The last dying fires of the day gleamed in the west, and in the front rose the tall, lonely house, sharply outlined in a silhouette.

He was within some sixty paces of the place when the profound stillness was broken by the musical notes of a bell. The bell gave three or four beats—like the Angelus—and simultaneously, from a curious squat chimney on the roof, came, a single, sudden puff of purple smoke, which hung for a moment, like a little cloud, over the house, and then slowly dispersed. Everything became silent again. It was just as if some one had thrown a handful of powder—some incense one might have fancied it to be—on a furnace at the bottom of the chimney.

The sudden, extraordinary occurrence arrested Vavin's steps, and he stood still in a great surprise. There was something disturbing in the whole thing. The melancholy hour, the lonely house, and the dark, mysterious forest beyond, all seemed to be in keeping with the sudden tolling and the puff of smoke. It was all unreal and fantastic, and for a moment he felt inclined to turn back and seek the safe companionship of the inn.

"It is like a drawing by Karl Boinbaum," he muttered: and then, ashamed of his uneasiness, he walked resolutely up to the house, skirting the wall till he came to a door. There was a bell-handle let into the wall, and, pulling it vigorously, he waited. The peal reverberated loudly some distance away. He listened for nearly two minutes, waiting for the sound of footsteps; but there was an absolute silence. No dog barked, no doors shut, there was no sign that any life was near the place. He resolved to give another pull, and at the precise moment when his hand touched the handle and be was about to grasp it, the door opened noiselessly, and a voice said:

"Will Mr. Vavin be pleased to come inside?"

It was very startling. There had been no indication whatever that any one was there; and the fact that the door had opened at the exact moment when his fingers touched the handle of the bell seemed theatrical and unreal. It was like some mechanical trick. He did not like it.

The person who had so startled him was a tall and very stout man, dressed as a servant. There was nothing unusual about him, except the singular smoothness of his large, clean-shaven face, which was unmarked by a single wrinkle.

"My masters expect you," he said, taking Vavin's portmanteau and leading him across the garden which stood round the house.

The place did not look nearly so gloomy on the other side of the high wall. The garden was laid out in parterres of bright flowers, and the white gravel paths were trim and neatly kept. At this hour, just as the dew was falling, the earth gave out a pleasant, moist smell; and the perfume from this old garden of mint and marigold and mignonette lay in strata of fragrance on the still evening air. The house itself was less attractive—a tall, white erection, with little to break the monotony of line and colour but the green Venetian shutters on either side the windows. At the left side of the building was a large chapel-like edifice, jutting out to meet the wall, and, from the position of its windows and skylights, Vavin could see that this was the studio. It was here, also, he noticed that the squat chimney from whence the smoke had come was placed, and he caught a hasty glimpse of a copper bell hanging from a joist which projected from the gable. He bad just time to notice these things when they arrived at the door, which was standing open, leading into a lofty hall somewhat sombre in its furniture and dark decorations.

"M. Stein and M. Beaugerac will be with you in a few minutes," said the man. "They are at present engaged in the studio. Monsieur will, no doubt, not object to wait in the study."

The room in which Vavin found himself was furnished with a good deal of luxury and an obvious attention to the little details of comfort. It reassured him at once. Some delightfully-bound books lined the fireplace wall, the mantelshelf bore pipes, cigarette cases, and all the little personalia of a bachelor establishment, and the chairs were soft and roomy. There were a good many drawings scattered about the walls—drawings of that esoteric morbidity that Vavin loved; and the walls were further decorated with a good many African curiosities. There were long, cruel-looking knives, horns of roughly-beaten copper and bronze, and a little drum of serpent skins.

He noticed also, displayed upon a shelf, a thing which he recognised at once, though he had never seen one before. It startled him, for he knew that there were, probably, only two more in Europe. He took it up, examining its shining steel and leather, with a little shudder at the horrible instrument of which so much had been said and written. He could not understand its presence here, for even in the darkest places of the West African coast the instrument was rare. It interested him to see it, and the fascination it exercised was in itself a pleasing sensation. It would be a great tale to tell when he went back to the Boulevard, he reflected—how he had seen and handled that devil-knife. He would be able to describe the real appearance of it, and to confute many morbid minds who were in the habit off dwelling on the thing.

He had just put the frightful object down when he heard voices and footsteps in the hall. He listened curiously, unable to account for the strangeness with which one of the voices fell upon his ear. The two men outside, whom he concluded were his hosts, were giving some directions to the servant, and the voice of one of them, though it spoke in a cultured manner, and in excellent French, had a curious and indefinably unfamiliar ring.

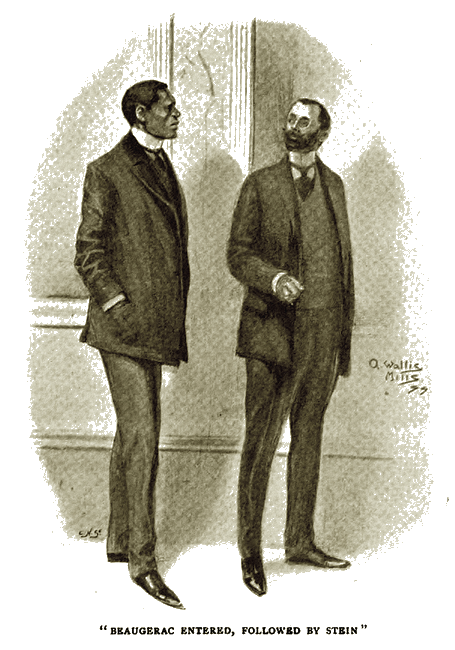

The mystery was soon explained, for in a minute or two the door opened and Beaugerac came into the room, followed by Stein.

Beaugerac was a youngish-looking man with an impassive face and close-cropped black hair; but his companion attracted Vavin's instant attention. With a start of inexpressible surprise he saw that Stein was no less than a negro, of full black blood. More than six feet high, and enormously broad, he was a splendid specimen of a man, and his almost coal-black face and thick, yellowish lips proclaimed him of a family which had known no alien admixture of race. Stein was very well dressed indeed, and his manners and conversation were those of a well-bred gentleman. He spoke French without a single trace of foreign accent, and he talked with the ease and poise of a citizen of the world. To Vavin it was extraordinary to find this great negro—who one might have imagined with a head-ring, and a spear in his hand—a person of the most assured and cultured cleverness, and a man who would obviously dominate any society in which he might be found.

He greeted Vavin very courteously, and after a well-served dinner they went into the studio to see some of the posters the artists were engaged on. The studio was very large and lofty. A poster-artist cannot work in a small space, because it is necessary that he should be able to get some distance away from has work to judge the effect that it will have upon the hoardings. It was bare of furniture and lighted only by a few lamps. The walls were painted a dull maroon, the sad colour presenting nothing to take the eye away from the affiches which hung upon it.

One end of the place was entirely cut off from the rest of the room by some heavy black curtains, and above them, for they did not quite reach the roof, a dull glow, as from a fire or from shaded lamps, threw monstrous purple shadows among the joists and beams. The place was full of shadows and curious light effects, and in the uncertain illumination it was difficult to see it in its entirety.

The two artists unrolled poster after poster for Vavin to see and judge upon. Their work was extraordinary in its appropriateness and strength.

Everything was done in flat tones, and the central idea in each production was the importance of the silhouette as a means of expression. Their Dusé poster, for instance, was done entirely in black, brown, and purple, with more than half the lines omitted, and yet the arrangement was so good that the merest hint of an intention was sufficient to produce all the effect of a finished and considered production. There could be no doubt about it; Beaugerac and Stein were head and shoulders above their contemporaries. They were the greatest living exponents of their particular branch of art. Their work, Vavin saw, could not be called decadent. It was too strong in conception and execution for that. There, was, however, he could not help feeling, something sinister about it. These vast pictured creatures, seen so closely, wore a cold-blooded and cruel aspect, and, examined at close quarters, their features, which on the hoardings were so effective, had an air of stupid and sombre malignancy that struck coldly upon his nerves. The impression was heightened by the shadowy studio and the active figure of the great negro as he went hither and thither with the long canvas rolls in his arms. Vavin wanted to be back again in the comfortable sitting-room; there was a chill in this place. Some influence he could not account for was filling his brain and laying cold fingers upon his heart. Beaugerac said very little, and the silence and his occasional sudden jarring laughter was also a disturbing element. Stein was, he thought, too suave and smooth in his manners to be pleasant. The critic felt lonely and ill at ease, and the words Dotricourt had whispered in his ear came vividly to him again and again.

A few days before, Vavin had seen that Mann, Rogers and Greaves, the great English firm of cocoa makers, who had shops in all the big French towns, had advertised that they were about to publish a poster by his hosts. Accordingly, as the memory came to him, he asked them if he might see it. When he made the request, Stein was over on the other side of the studio and Beaugerac was standing near him, but Vavin's words made them wheel round suddenly, and Beaugerac said something in a quick undertone.

"I am really very sorry," said Stein at length, "but most unfortunately the cocoa poster is packed up in waterproof ready to be sent off to-morrow. What a pity you didn't come a day sooner! Then you could have seen it. These things always happen like that, don't they? I can show you some of the sketches though. Suppose you go hack to the study. I will bring them to you. Beaugerac, show M. Vavin back, and I will join him in a few minutes."

Vavin went back to the study, and was left alone. It struck him, as he sat waiting, that there had been something insincere in Stein's remark about the cocoa poster, and he wondered why it had not been shown to him. There seemed to be no very adequate reason he thought. The room was very hot, so he got up and opened the window. As he went back to his seat he noticed, with a start of surprise, that the thing which had been lying there on the bracket had disappeared. The circumstance was strange and he could only conjecture that the instrument had been left there by accident in the first instance. He had hardly settled in his seat, and was feeling in his pocket for some matches, when he heard for the second time the sudden tolling of the bell. It roused his curiosity, already very active, to an almost unendurable pitch. His conversation with the artists had merely enlightened him as to their views on art, and he had been unable, try as he would, to learn anything of their past history. He had asked Stern in what ateliers he had studied, and had been met with the suave: "Oh, all over the world, my friend. I have never stayed long in one place. I am cosmopolitan." Both his hosts had seemed determined to reveal nothing of their careers. This unusual reticence, together with the attendant circumstances—the sombre studio, the African devil-knife, the unexpected sight of the negro—told him with more and more potency that something was wrong about the place and its owners. The musical notes of the bell, which ceased as suddenly as they begun, put the finishing touches to his uneasiness and curiosity. He rose up again quickly, and going noiselessly through the hall, went out into the warm starlit night, determined to find out what this sudden tocsin foreboded.

He went quietly towards the studio, treading upon the borders of the flower-beds to avoid making any noise upon the gravel. The studio was quite dark, save for one faintly-illuminated window at the end. This window he knew, from its position in the wall, must be behind the black curtain which hid one end of the room. As he approached it he noticed a faint aromatic odour in the air, like the smell of incense.

The window-ledge was some seven feet from the ground, and a small projecting buttress at its foot assisted him to raise his head above the level for a few seconds. As he did so, the light flickered up, and he was able to see with some distinctness what was going on inside. On the wall at the end a great poster was hanging; the design, as well as he could make out, consisted of a large head. In front of the poster stood a table of some dark material, though he could not see what it was. Beaugerac he could not see, but Stein was standing by a brazier full of burning cinders, which was fixed in the wall under a large iron pipe communicating with the chimney. The red light fell on his face and hands, and he appeared to be doing something to the fire. He watched for as long as he could maintain himself in the difficult position, and then with no more information than when he started, quietly returned to the study.

All that he knew was that Stein and his partner had something that they wished to conceal, and that in all probability they had lied to him about the poster.

He had not been long seated when they came in, carrying some drawings.

"We had an awful difficulty in finding the sketches," said Stein; "they had got mislaid. We hadn't any light but the little fire which we use for mixing pigments, and I nearly broke my shin over a table, and nearly hung myself with an old bell-rope, which they used when this place was a school. Very sorry to keep you waiting, but I hurt myself rather badly. All the negro races are very sensitive in the leg-bones, and a blow which to you would be nothing is agony to me."

His easy manner and the simple explanation, in some sort, reassured Vavin, and he looked at the sketches with great interest. The design for the poster was simple, consisting of the bust of a negro, which filled nearly all the space, the lower part of the body being out of the picture. The lettering was in bold, crimson characters. The figure was sketched in two browns, with as few lines as possible. Even in the small sketch one could see the enormous power of the thing, and it was easy to imagine the effect the great twenty-foot poster would have in the streets. The face of the figure was so cunning and malignant, such immeasurable wickedness lay in it, that his attention was caught and held as if in a vice.

"You see," Beaugerac said, "our idea, in the first instance, has been to have a single unbroken mass which the eye can readily understand. Then, the idea of a poster being to attract attention, we have made the face as repulsive as possible."

"He is a wicked boy, is he not?" said Stein, leering at the foul thing, and as he did so, himself looking not unlike his own creation. "He would play some fine blood-games if he were alive. What? He would kill his mother, and make a set of dice out of her knuckle-bones, for ten centimes! There is something interesting in his face, yes?—he is cunning, I think?"

Vavin shuddered. Foul as his own imaginings sometimes were, he felt cold to see this great soft-voiced negro nodding and mouthing at his own creation.

"Satan himself has not such a face," he said. And then a strange thing happened, for even as he spoke three or four sudden beats of the bell rang out upon the air. Beaugerac jumped up with an oath, and then suddenly sat down again, and Vavin could see round the corner of the table that the fat hand of the negro was gripping him tightly by the knee.

"O dear, dear me," said Stein quickly, "that stupid cat has got locked up in the studio again. What a nuisance! I'll go and let it out, or it will be upsetting something and hurting itself. I won't be a minute."

Despite his assertion, he was away half-an-hour, while Vavin kept up a fitful conversation with Beaugerac, who was distrait and dull.

When Stein came back he explained that he had found the cat, which had upset a pot of white paint, and that he had had a great deal of trouble in removing the stains from his hands.

ABOUT eleven Vavin went to bed, in a highly-strung and nervous

condition. His room was at the head of the stairs, and had a

window which looked out into the courtyard of the studio. While

he was undressing he could not forget the face upon the poster.

It filled all his brain and dominated him, and, as he lay awake

in the silence, fear came and whispered strange things into his

ear.

About two he awoke from a fitful slumber, and, finding himself hot and covered with perspiration, he got out of bed and went to the window, intending to open it wider.

As he came to it he heard a slight movement in the court below, and peering down he could just discover a large grey mass moving across it. The object came right up to the wall and seemed to enter the house at the door just below him. Simultaneously a faint light appeared in the doorway of the studio opposite. The light grew brighter as some one holding it came nearer to the door, until he saw Stein and Beaugerac standing in conversation on the step. The monstrous shadows thrown by the candle did not at first allow him to see their faces, but with a quick pulsing of his heart he noticed at once that in his hand Stein carried the instrument he had seen in the study.

A sudden flicker of the candle which Beaugerac held showed him that they were gazing expectantly at the wall just below him. Beaugerac was smiling.

Fearful that he would be seen, he shrank noiselessly away from the window, and as he did so, he distinctly heard in the passage outside his room the sudden cry of a child awakened from sleep.

He opened the door and crept out.

At the other end of the passage a door stood open and a light shone out towards him. He could hear something moving about in the room, and there was the sound of heavy breathing.

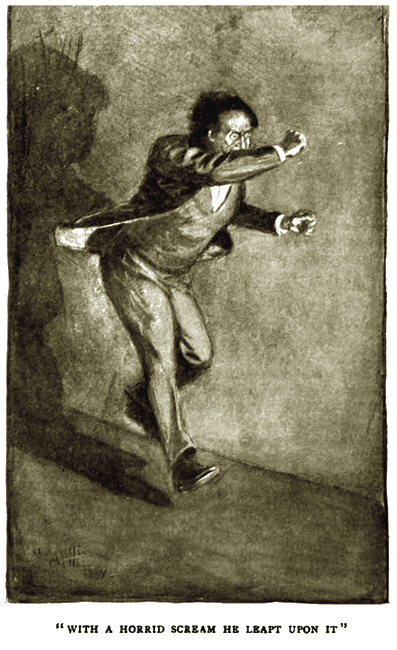

Hearing footsteps approaching the door, he sank into the deep embrasure of a window. The footsteps came slowly along the passage towards him, and then this is what he saw. The black figure of a man, larger than human figure ever was, was walking past him, holding a candle in one vast hand. In his right arm he held a little white-robed girl of two or three years of age, and his face was, line for line, the face of the great poster.

The little child lay quite still, with staring, open eyes, and the thing was bending its head and looking into her face, lolling out its tongue and rolling its great eyes.

It had just got to the head of the stairs when Vavin was seized with a frightful and uncontrollable wave of passion and hatred for the cruel, bestial thing.

With a horrid scream he leapt upon it, snarling like a dog, and then he was conscious of the shouting of a great company of people, a sensation as of rapidly falling through black water, and nothing more.

HE died the next day in agonies of terror, yet not before he

had had a long conference with the priest, who gave him

absolution.

Before his final paroxysm Père Gougi told him that when the villagers had burst into the house they found little Cerisette white and still at the bottom of the stairway. Stein and Beaugerac had disappeared and were never seen again in Normandy.

It was afterwards discovered that a long package had arrived in the Rue des Martyrs—the Paris office of Messrs. Mann, Rogers and Greaves—with a letter accompanying it from Stein, saying that he sent the completed poster. When it was opened the great sheet of canvas bore nothing but some scarlet lettering.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.