RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

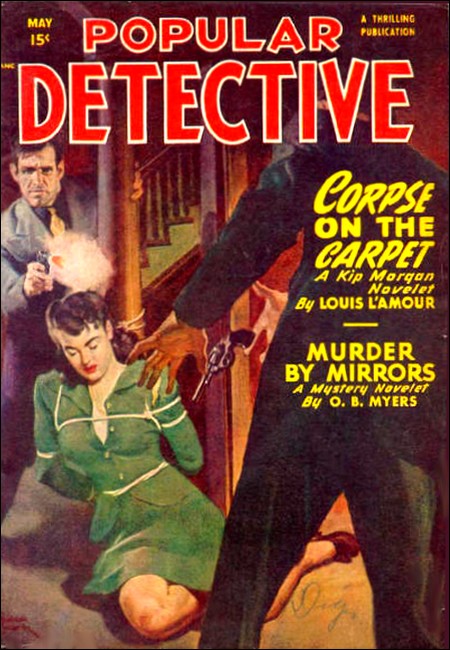

Popular Detective, May 1948, with "Walk Softly, Death"

Rifles held taut across their bodies, they hurried into the grass, pursuing Vic.

A jail cell held the answer to the murder of Vic's policeman

father, and the price of learning it would be—Vic's own life!

THE Police Academy stank of liniment and sweat, leather and rubber. They'd set up long rows of camp chairs facing the platform at the east end of the gym and another, single row on the platform. Most of the young men who filled the chairs, lean and eager in their brand new uniforms, listened attentively to the high-sounding phrases that the Mayor was mouthing, but Vic Dunn let them slide past his ears only half heard.

His dark eyes somber in his narrow bony face, Vic looked at the row of the Department's top brass seated on the platform. The Commissioner. Chief Burnham. The captains who headed the Headquarters squads. But one man who should have been up there was missing...

"And no one regrets more than I," the Mayor was saying, "that he is not here to pin on his son's breast the badge he himself wore so long and with so much honor. I give you, as a symbol of the selfless service to which you dedicate yourselves today—Captain John Dunn, slain in the performance of his duty."

Vic's hand moved to his breast pocket. Under the harsh fabric he could feel the letter which he had first read in a billet overlooking the Via Corso.

This is the last letter I'll be writing you, son. It's going to be swell to talk over my puzzles with you again, like we used to.

I've been struggling with one tough case this past year, but just today I turned up something. On second thought I'll save telling about it until you get back. I hope it's soon.

Vic Dunn made it as quick as the Army's slow-grinding mills would allow, but it hadn't been quick enough. His father had been slain in the performance of his duty, by a shot out of a dark alley, the very night this letter was postmarked. There was another paragraph in it:

What's this tomfoolishness about your not coming on the Force because your college education would be wasted on police work? That's the bunk. It might have made sense back when I started pounding pavement, but not in these days...

CLATTERING applause brought Vic back to the gym.

The Mayor had finished, was stepping back from the lectern, and Chief Burnham, white-haired, hawk-nosed, came forward.

"Rise!" he barked.

Vic Dunn was one of ninety who sprang up and to attention as a single unit.

"Raise your right hands and repeat after me the following oath..."

"I, Vincent D...unn, do swear faithfully to support..."

Then he was one on a long blue line moving to the platform and up on it. The Mayor's bald pate was level with Vic's chin as he pinned on the shining badge, mumbling congratulations.

"Thank you, sir." Vic said.

Commissioner Carlin's eyes were dead marbles in bags of loose skin, his hand limp.

"Congratulations."

"Thank you, sir."

The line moved haltingly past gold-braided uniforms and more handshakes, more mechanical thank yous. The last in the row was Dan Staine, captain's bars on his collar, his hair iron gray above a gaunt, finely netted face. Otherwise he was the same as when he would stand chatting with John Dunn where their beats met and a tow-headed lad stood by, adoring.

Staine said nothing but Vic's fingers still ached from his grip when the blue line carried him down off the platform and along the gym wall to a desk where a clerk handed each man a slip of paper. The line broke as friends looked for one another to compare the assignments marked on the slips, but no one looked for Vic and Vic looked for no one.

He stood mask-faced, blood pounding in his temples, as he stared down at the slip the clerk had handed him, at the single, incredible word which was under his name:

RESERVE

It meant—no assignment. It meant—go home and wait till we send for you. It meant—you made a poor probation. You just squeezed by.

That was a lie. Maybe he hadn't showed up as best of the class but he certainly hadn't been anywhere near the worst. Someone had fouled up the detail. First thing tomorrow he'd go down to Central Office and get it straightened out.

Meantime, there was nowhere to go but home—two rooms and a kitchenette that seemed even more desolate than when he'd returned to them a year ago.

When he got there, Vic stripped off his new uniform and hung it in the bedroom wardrobe, next to the worn and wrinkled one with gold-encrusted sleeves and a bullet-hole in its breast. He reached for a pair of gray slacks—then twisted about startled, as a phone rang in the outer room. It was the first time that bell had rung in months.

HE padded out to the instrument, plucked it from its cradle.

"Yes?"

"Patrolman Dunn?"

"Correct, sir."

"You know who this is?"

"Certainly. You're—"

"Cut it," the recognized voice snapped. "Don't say my name, just listen. I want you at my house tomorrow night at one A.M. sharp. The back door. Don't shave from now on, wear your oldest cits, stripped of identification. Make sure no one knows where you're going and no one sees you come here. Understand?"

"I understand, sir."

But, hanging up. Vic understood only that Captain Dan Staine had given him an extraordinary invitation. An order, rather. His tone had made that clear.

He padded back to the bedroom. In the closet he found the assignment slip in the uniform's side pocket where he'd thrust it.

He tore the slip across and across, and across again.

THE dim, deserted street seemed far narrower than Vic Dunn recalled it out of childhood memory. The block of two-story brick houses was shorter and dingier.

All the houses were exactly alike. No light showed from them and the driveways between them were black. But as Vic plodded past the third house from the corner his furtive sideward glance caught the red spark of a cigar's tip within an open first floor window and the blob of a face.

Why should Captain Staine be waiting for him in the dark?

The thrum of a powerful motor grew louder ahead. The car that came toward Vic was a low-slung convertible, cream-colored in the pale glow of a street lamp. As it passed him, he made out only that it had two occupants. The car slowed behind him, as if to stop at the Staine house, then resumed speed. Vic turned just in time to see the vehicle slide around the corner.

The street was empty again. Vic darted into the down-slanting alley between the fifth and sixth houses, reached its inner end and then paused, peering out.

Fifteen years had changed nothing here either. The wide concrete space between the rear of the houses and the line of garages facing them still was uncrossed by fences. Short wooden flights still dropped from shadowy back doors and battered cans were set out awaiting the morning collection.

In motion again, Vic kept as close to the walls as the cans would permit. Even though the windows above him were dark, some sleepless person might look out and see him.

He passed the fifth house, was passing the fourth, when he spotted the shadow crouched against the wall of the third house.

Staine?

Staine hardly would be furtively sliding open a basement window of his own home. Sucking in his cheeks, Vic sneaked as soundlessly as possible across the intervening space. He clamped his right hand on the prowler's right elbow from behind, and slid his left in under the fellow's left armpit to come up and back again behind the neck for an unbreakable hold.

"Gotcha," he grunted.

But then he let his grip go lax. For suddenly he realized he had encountered rounded, feminine softness. In that shocked instant, the captive twisted free and darted away.

VIC recovered, leaped after the fleeting shadow. He cracked his shins on an unseen garbage can. Its cover was still clattering when he reached the driveway alongside Staine's house, but the alley was empty.

Vic knew that before he could reach the street, his quarry would have had time to conceal herself in any one of a half-dozen vestibules. To search for her would be futile. Then the sound of a lock clicking turned his head back to Staine's rear door.

A tall shadow emerged from that door and paused on the landing. Vic went back there, up the stairs. He stepped past Captain Staine into a narrow, dim entry that at once went black as the door was closed.

"Why," Captain Staine demanded in a tight, low tone, "didn't you blow a siren and make sure the whole block knows you've arrived? Or are you going to tell me a cat made that racket?"

"No, sir. I did. I caught someone trying to break into your cellar. A woman."

"A woman?" The low voice was startled, but stayed low. "A young woman?"

"I couldn't see." Vic remembered her flower-like fragrance, not like that of any flower he could name. "But she felt young."

"Felt?"

"I grabbed her from behind, but she slipped out and got away."

"Some cop!" Oddly enough, the comment held no rebuke, rather a hint of relief. "All right. Let's go where we can talk."

"But aren't you going to do anything about her?"

"No."

Years in the Army had taught Vic not to argue with a superior. But he was filled as never before, with a premonition that trouble lay ahead.

E allowed Staine to lead him past a staircase, mounting out of a shadowy foyer, into a small dark room at the front of the house that reeked with tobacco despite a half open window.

Staine pulled a black shade down over the window and switched on a light that revealed a leather couch, a deep club chair upholstered in the same worn, brown leather and hollowed to the shape of uncounted buttocks. In one corner was a roll-top desk and a battered swivel armchair.

Obeying his host's gesture, Vic sank into the leather chair, watching Staine settle into the one at the desk. Staine fumbled a cigar out of the box on the littered writing surface and carved the tip.

Back of the cigar box was a photo, framed in tarnished silver, of a sweet-faced woman. The hair was drawn tightly back and the high-boned, black-net collar that clasped a proud neck recalled to Vic the face of his own mother.

They'd been friends, his mother and Myra Staine. Both were long gone. The Staines had had a daughter too. Ellen. That was all Vic could remember of her, her name. She'd been about five when Mom had died and he and Dad had moved away to the flat on the other side of the city.

That had been the last Vic had seen of the Staines, the old warmth between John Dunn and Dan Staine had already cooled. Why, Vic wondered now. Was it because his father had been promoted to lieutenant while Staine remained a sergeant? Did the caste system banning intimacy between officer and non-com also prevail on the police force?

Staine wheeled in his chair, his cigar drawing to his satisfaction, and studied Vic's face.

"Curious to know what this is all about, Dunn?"

"Naturally."

"Well, the first thing I've got to tell you is that while, as far as anyone in the Department or out of it knows, you're unassigned, actually you're on my squad."

Vic's pulse jumped. Staine's squad was Gambling and Narcotics, and a cop wasn't put on that till he'd amply proved himself.

"Don't run away with the idea," Staine quickly added "that I picked you because you're John's son. If anything, that was against you. I needed a man who hadn't been seen all over town in police uniform and who wouldn't be missed if he dropped out of sight, without explanation, for a week or a month. A rookie, in other words, who's got no family, no chums, especially no gal. You're the only one in the batch who fits. Or have I missed something?"

"Not that I know of, sir. I lost touch with the friends I had before I went into the Army. I haven't made any new ones. I take care of my flat myself, so there's no housekeeper to ask questions. I can't think of anyone who'd know, or care, whether I was dead or alive."

"Good." Staine's gnarled fingers drummed on the end of the chair arm. "In this job I have in mind for you, you'll be against a smart bunch—and one that plays for keeps. You could get hurt. But you don't have to do it if you don't want to."

"You know the answer to that, Captain."

"Sure, but I had to say it. Okay, here's the setup. About two years ago—"

Staine stopped, twisted toward a whisper of sound in the hallway. Then a girl appeared in the door, her dark hair framing an oval, pert-featured face. Her drowsy, blue eyes widened as she caught sight of Vic.

"Oh-h-h," she gasped. "I'm sorry."

She started to turn away, but Staine's rasped, "What's wrong, Ellen?" pulled her back. "Why are you awake?"

"Some noise out in the yard woke me and I couldn't fall asleep. Then I heard someone moving around down here."

She must be twenty, Vic figured. But she seemed much younger standing there in bare feet.

"I—I was frightened," she said. "I tried to tell myself it was nothing, just the house whispering to itself like it does late at night, but it wasn't any good, and I finally got up and went to your room to tell you and you weren't there. Then I saw light down here, so I came down."

"To tell your old man it was time for him to turn in?" There was affection in Staine's voice, but something else too—a reserve. "Look here, Ellen." Now it was very stern. "I want you to forget you saw anyone here tonight. I want you to be sure to say nothing about it to anyone. Understand?"

"Yes, father." Her voice was demure. "I understand." Her blue eyes slid back to Vic. "I'll be careful."

She couldn't have any idea who he was, Vic knew. Even if the thirty hours' stubble on his face hadn't masked it effectively, she hadn't seen him since he was eight and she only five.

"Please come up to bed soon, father. You need your rest."

"I'll be up as soon as I can. Good night, puss."

"Good night."

STAINE'S look stayed on the doorway from which she'd vanished, and Vic was glad of that. For through the tobacco reek he'd caught the fragrance of that flower he could not name, and which he'd smelled a short while before, out in the yard.

Perfume was sold by the hundreds of bottles in dozens of shops, he reminded himself. It added up to nothing that two girls used the same scent, particularly a new and therefore popular one.

"As I was saying, Dunn," the captain resumed, "We're up against a tough outfit. No one has ever succeeded, no one will ever succeed in completely cleaning up the illicit sale of narcotics. It can, however, be held to a negligible minimum except for sporadic flare-ups that invariably are traced to an organized gang. Ordinarily it's easy enough to quell these flare-ups by picking up a few peddlers and backtracking from them to the heads of the gang. Some time ago it became evident that such a mob was operating, but with a difference. Nearly two years have gone by and we haven't got to first base against them."

"You mean you haven't nabbed their sellers?"

"We've pulled in a half-dozen," Staine growled. "They're addicts themselves, as per usual, but holding out the stuff from them to make them sing has netted us exactly nothing. Either they don't know their sources, or they're being slipped their snow—cocaine—right in their cells. That would seem screwy, too, except for one thing. On three occasions we've sent out good cops to try and wangle into the mob. Each time—" Staine drew the edge of his hand across his corded throat. "So quick," he added, as a chill prickled Vic's spine, "that the only answer is someone on the force, maybe on the Narcotics Squad itself, tipped the mob off about them."

"That's why you're so determined no one should know you're putting me out to try the same stunt?"

"That's why, except that I'm switching the angle." Smoke trickled from his thin, grim lips. "We know the junk's being peddled in the City Workhouse. If we can find out how it's getting in there—"

"We can backtrack to the main mob," Vic broke in, eagerly. "So I'm going in there undercover to find out. Which is the reason for the old cits and the no shave."

"Right." The older man nodded. "A little dirt on you and you'll make a first-class bum, except for that belt and those good shoes. I've got an old trunk strap will do for the one, and a pair of shoes I use fixing the furnace ought to get on you with room to spare. Getting you into the Workhouse is easy enough. The hard part will begin once you're in. We can't trust anyone to help you, not even the warden. You'll be on your own."

Excitement leaped in Vic's veins, but he kept it out of his voice. "I'll manage."

"You'd better."

Twenty minutes later, in the dark back entry of the house, Captain Dan Staine reached for the door to let Vic out.

"Hold it a minute," Vic said. "There's one thing more I need to know."

"What's that?"

"My father was head of the squad, wasn't he? They made you a captain and gave you the squad after he died. That was about a year ago, and this drug mob's been operating almost two."

"Right."

"Then—" Anger clogged Vic's throat momentarily. "Then I want to know what you meant when you said my being his son was against my being picked for this job. What were you hinting at?"

"You young idiot!" Staine's hand gripped Vic's forearm, fingers digging in. "There's one thing you've still got to learn. That a cop's judgment, like a doctor's, is apt to be warped if his emotions get tangled up in a case."

"His emotions?"

"Like love. Or hate."

Hate? John Dunn had written, I've been struggling with one tough case this past year, but just today I turned up something... And that night he had been ambushed.

"I understand, sir," Vic murmured. "I'll watch myself."

"See that you do." Dan Staine's hand dropped away. The knob rattled and the door opened.

VIC DUNN watched the crabbed hand move a pen across the ruled sheet. The desktop was ruled too, by the long, thin shadows of the iron bars that caged the window through whose crust of dirt the gray afternoon light seeped.

"Name?"

"Nudd. Joe Nudd. N-u-d-d."

"Home address?"

"Allen's Alley."

The gray head didn't look up, but the tired monotone said, "Look, bud. You're gonna be in this coop thirty days. You can make it easy for yourself or you can make it tough, an' crackin' wise is one way to make it tough. What's your home address?"

"Put down Pleasant River, Nebraska." Vic knuckled the desktop, bending his elbows to bring his head down nearer to the gray one. "You sound like a right guy." It couldn't be heard two feet away. "Tip me to the cock o' the roost here."

The hand pulled over the list the patrolman from the Black Maria had turned in. Drunk and disorderly, the hand wrote.

Vic belched the dead-cat taste of "block an' fall" whiskey (you drink a shot, walk a block an' fall), felt the dull ache at the back of his skull where a nightstick had thudded.

No visible means of support. The pen stopped there, as if pointing.

"I got what it takes," Vic murmured. "The bones were good to me last night, and what they gave me's ditched where no bull nor no screw'll spot it."

"Okay." It was the same lipless undertone Vic had used, far more secret than a whisper. "You'll be contacted." And aloud, "That's all, Nudd. The door on the right. Next."

Vic shambled through the stench of disinfectant, the sour smell of unwashed bodies, to the indicated door. A turnkey opened it, and it passed him into a larger room lined with open-faced cubicles in which men were stripping.

Vic smelled steam, the pungent sting of strong soap, heard the sound of rushing water. This was good. This was what he needed, to scrub away the stink of the water-front dive, the crawling itch of the Stockade in the Police Court basement, the stink and itch of the Black Maria that had brought him here.

The city couldn't afford to clothe its transient guests. After your bath and a shave that left your skin raw, and after a rough-handed doctor had invaded your ultimate privacies, you received back the clothes you'd come in and put them back on, hot from the delouser. Then a blue-jowled guard, someone called Josh, conducted a half-dozen of you down a long corridor and up a flight of rutted stone steps.

Josh stopped on the first landing and sent the others in through a door where another keeper took them over. But he motioned to Vic to climb another flight. They went through a similar door there and when Vic saw that the iron cots lining the walls of the big, sun-flooded dormitory had mattresses in addition to the drab blankets he'd seen folded at the ends of naked springs in the dim room below, he knew that the word he'd dropped at the reception desk already had been passed back.

"That's your bunk," the keeper said, jabbing a thumb toward one midway of the wall. "The latrine's down there." The thumb indicated a closed door at the rear of the room.

"Where's everybody?" Vic asked.

"In the shops," Josh replied. "You'll get your assignment in the morning. If you smoke in here, keep your butts off the floor."

"Suppose you ain't got anything to smoke?"

"Canteen in the mess hall sells cigarettes before and after chow."

"And if it's something else beside smokin' you need, what then?"

Josh's brutish face went blank. "I wouldn't know, mister."

He turned, and, plodding out of the room, started down the stairs. Vic shrugged, went past battered tables and unpainted chairs that ranged the room's center.

The door at the rear hung on spring hinges and it was so warped that almost an inch of light showed between its vertical edge and the jamb. Through this slit sound came, a thud, a rasped oath, a thin and terrified squeal.

"No, Matt. No. I didn't go to slop yuh."

"That helps." The second voice was low, slow, but it held an undertone of cold fury. "That takes the muck off my pants." His eye to the slit, Vic saw a man in a brown suit viciously gripping the shoulder of a weazened little man whose face was big-pupiled, and blue-lipped.

"No," the little man squealed again, as the brown shoulders hunched and the hand came up, flat palmed and driving edgewise for the old man's Adam's apple.

Vic thrust the door open and it hit the man in brown hard. Following the door through he saw the man had been knocked against the sidewall.

"Gee," he exclaimed, wide-eyed. "Gee, pal, I'm sorry."

"Sorry!" The fellow snarled and leaped for Vic.

HEN Vic stepped to meet him. He grabbed a wrist in a steel clutch and pulled it back and up behind twisting shoulder blades.

"Easy," he drawled to the back of the man's blond head. "Take it easy, fellah, or you'll bust a gasket."

His captive made no effort to break the hold. It would have snapped his arm if he had. Beyond him, amazement and an unholy joy were replacing the terror in the old man's rheumy eyes.

"Beat it," Vic growled at the oldster. "Take a powder." And then, when the old fellow had shambled out with his mop and pail, Vic spoke again to the man in brown. "What's the idea jumping me? You figure I could see through that door?"

"No."

"Oh, so you hop every new guy regardless, just to show him you're cock o' this roost and intend to stay that. Well I ain't ambitious, so suppose we leave it at that. What do you say?"

"Suits me."

"Swell."

Vic let go and stepped back. The man turned to him. He was almost as tall as Vic, chunkily built, his hair an odd silvery blond and cropped to follow the squarish shape of his head. In a brown rayon sport shirt, wool slacks of a deeper shade of brown, he seemed completely out of place in this galley. Until, that is, one noticed his eyes, the irises almost colorless, the pupils pinpointed.

"My handle's Nudd," Vic said. "Joe Nudd."

"I'm Matt Rawley." He looked down at the dark spatter near one neatly pressed trouser cuff. "That blasted ape! If he slops me again, I'll cripple him." The pale eyes raised to Vic's. "He bumped me while I was getting an earful of what you was asking the screw." And then, with apparent irrelevance, "How's the weather outside?"

"The weather?" A muscle knotted at the point of Vic's jaw. "Well, I'll tell you. It looks like snow, I hope. That's what I go for. Snow."

Rawley let his thin lips relax. "Sleigh-riding comes high—in here."

"How high?"

"Well-ll, if you left a sawbuck under your mattress before you go to chow, it could turn out you was right about the weather. And if I was you I'd put another one with it for luck."

"Luck?"

"You'll need some when they start handing out the jobs to you new birds. Of course—" the blond man shrugged—"if you like stoking furnaces or maybe cleaning latrines like Pop Morse, that's up to you." His thin smile licked his lips again and he shoved out through the door.

Vic watched the door swing back and forth and come to rest. Then he turned away to find a cranny of the washroom where he'd be hidden from anyone else who entered. Here he pulled out of its loops the wide trunk strap Staine had given him to use as a belt, bit off a knot in the stitching along its edge, and separated the leather layers with his thumbnails.

The pocket thus opened revealed, among other things, a couple of grimy tens folded lengthwise. Vic hesitated, decided to extract a pair of fives instead. He replaced the makeshift money-belt, went back out and across to the cot the keeper had said was his. He spread the blankets, took off his shoes and lay down.

The only sound in the big room was the thump of the long-handled brush with which the weazened old man, Pop Morse, was sweeping the floor and the rustle of the magazine Rawley was reading, as he stretched on his own cot in the choice corner between two windows.

Rawley obviously was the kingpin of this domain, the privileged prisoner to whom no rules applied, the contact between those inmates who could pay for favors and the guards who sold them. The important question was whether, he was tied directly to the narcotic ring outside the Workhouse or if in this, too, he was merely the go-between for some guard or clique of guards.

The brash way Rawley had opened negotiations indicated that this would not be easy to determine. Rawley was no fool. He had a vile temper, but he'd brought it under control the instant he'd realized the sort of man with whom he had to deal. He was smart and he was dangerous. Well, Vic yawned, there was plenty of time to figure out how to outsmart him.

Weariness welled up in Vic and he closed his eyelids, but somewhere at the blurred edge of sleep a face formed in his thoughts, oval, pert-featured, framed by black ringlets that contrasted oddly with naive blue eyes. Whether Ellen Staine had been the girl at the basement window or not, her father had thought she was. That was why he'd done nothing about investigating.

Something bumped Vic's cot and Vic, opening his eyes, became bemusedly aware of a wrinkled gray head bobbing rhythmically nearby.

It was Pop Morse. The old man was sweeping between the cots. His brush tumbled Vic's shoes.

"Cripes," he mumbled, not looking at Vic. "Cripes these kickers is crummy. What size you wear?"

"Eleven D. But what—?"

"I can rustle you a pair of new ones by tomorrow night."

"I could use 'em." So even this bleared derelict had a racket. "What will they stand me?"

"Not a red. They don't cost me nuttin' an' I owe 'em to yuh for the way you set that snake back on his heels."

Before Vic could protest, the old man was shuffling away, pushing his brush ahead of him.

ODD. Where did he intend to steal the promised footgear? How could he be as sure as he seemed to be of laying hands on the right size? The Workhouse didn't supply clothing, so he couldn't have in mind raiding a storeroom. Maybe there was a shoemaking shop.

There was none, Vic learned at chow, by asking a number of discreet questions of his neighbor in the clattering mess-hall.

"Then how would a guy get himself some new kicks if he needed 'em?"

Red Neal, squat, broken-nosed, ate a mouthful of greasy stew. "He could get a money order from the office an' write away for 'em. Or mebbe he could get some pal on the outside to buy 'em an' have the store mail 'em to him."

"Why that? Why couldn't his friend mail 'em himself, or bring 'em to him?"

"Because you ain't allowed to get no packages in here unless they're mailed in right from some store or comp'ny or some big place like that. Not even Matt Rawley ain't, that's how strict that rule is."

The dormitory was crowded and noisy when Vic returned to it and went to his cot. Watching his chance, he slid a hand under its mattress unobserved. The two bills he'd left there were gone. In their place were three papers folded as a pharmacist folds his prescription powders. He retired to the washroom's precarious privacy and opened one of the papers.

It contained about as much white powder as would cover two nickels. There were only traces of the glistening flakes that earn for cocaine its designation of snow. He tasted the powder. It was mostly sugar! Yes, "sleigh-riding" came high in here. The three decks of this "cut" stuff he had bought for ten dollars would last even a moderate addict not more than a couple of days.

That suited Vic. Night after next he'd leave another ten in his cot and spot who made the exchange. By that time he would have worked out a way of doing the spotting.

THE next morning brought Vic Dunn something else he'd purchased with a ten—assignment to the Workhouse office. The clerk in charge of this inner room was a horse-faced civilian named Ben Green.

He set Vic to work copying old records onto five-by-eight cards.

From the table where Vic sat he could look out into the larger room where most of the institution's business with the outer world was transacted and where its daily grist of prisoners was admitted.

Through the door he could see a short stretch of cobbled yard, the high granite wall that enclosed the grounds, and the iron-barred gate in the wall with its arched top and sentry boxes.

About six feet within the outer door a meshed metal screen ran across the room from wall to wall. Neither new prisoners, guards nor civilian personnel were permitted to pass through the door in this screen without being searched. Visitors did not penetrate it at all, but were directed to a narrow entry at the side where they conversed with the inmates through another, similar screen and under a keeper's watchful eye.

These precautions, as well as the regulations regarding packages about which Neal had told Vic, were unusually stringent for a municipal house of correction.

Obviously they had been instituted to cope with the illicit introduction of narcotics into the Workhouse.

Yet the drugs were getting in.

THE principal occupation of Ben Green, the clerk in charge of this inner room, seemed to be playing endless games of solitaire. The principal occupation of the three other prisoners, who with Vic inhabited the inner office, seemed to be swapping stories that would have made a marine sergeant blush. Vic tried a couple of the filthiest he knew but they were received with marked unacclaim. He was glad enough to immerse himself in his footless-seeming job of copying the records, and was relieved to discover that one of the advantages of working here was that you were released some twenty minutes before five-thirty, the hour when the other inmates ended their labors.

Vic's co-workers apparently were domiciled elsewhere. He was the only one who climbed the stairs to the top-floor dormitory. Pop Morse met him on the landing, stopped him with a palsied hand.

"How are yuh, boy? Had any trouble?"

"Who'd make me any?"

"That snake Matt Rawley, of course. He ain't forgot what you done to him." Red-rimmed eyes peered fearfully down the stairs. "Nor I ain't neither. The shoes are on the floor of my closet back there." His eyes shifted to a hitherto unnoticed door at the rear of the landing. "But don't let him know I give them to you."

Before Vic could answer, the old man had turned away and was scuttling down the stairs.

The closet had a stench of foul rags and rancid soap powder. Holding his breath, Vic fumbled among brooms, wet mops, grease-smeared pails, and brought up a pair of black oxfords still gleaming with their original factory polish.

"Pretty neat," remarked someone behind him and he wheeled to it. Matt Rawley stood there. "What are they?" Rawley asked. "Jon Maclins?"

Vic turned the shoes over and stared at the familiar trademark of the "plant to wearer" chain whose shops were almost as plentiful in the city as gas stations.

"Yeah. They're Maclins."

"What did Pop soak you for them?"

Pop had warned him not to let Rawley know the source of those shoes, but caught taking them out of Pop's closet, Vic couldn't very well deny their origin.

"Twelve bucks," Vic said, recalling that Maclin's single price was five-ninety-five, "Did I get stuck?"

"You didn't get no bargain." Rawley's pale eyes were expressionless, but muscles moved in his sallow cheeks. "Next time you want anything like that, ask me."

The flat tone gave no clue as to whether Rawley intended this as an offer or a warning.

"Thanks, Matt," Vic grinned, choosing to take it as an offer. "I'll remember." And then, "Look. There's a couple or two things around this dump I'd like you to wise me up about. How's for our chewing the fat while I get into these new kickers?"

"Some other time, pal," the blond man murmured. "Just now I got to see a man about a rat."

Matt Rawley's feet made no sound, descending the stairs.

OUR years of war had endowed Vic Dunn with the ability to wake, completely alert, at any predetermined instant. He opened his eyes now to moonglow, striped by the shadow of bars, to foul air, to choked snores and whimperings that were somehow less human than bestial.

Lying motionless, he examined the cots that stretched to the room's rear, the mounded, dark forms on the cots across the room. Satisfied, at last, that no one else was awake he rolled over, as if in restless sleep, and inspected the other side of the dormitory. He peered with special intentness at Rawley's bed. After a long while, he slid out from under his blanket and padded swiftly out to the stair landing.

The moon did not reach here, and there was no other light, so Vic trailed fingers along the dormitory wall. He managed to find the closet door, which he'd left not quite closed so that he'd have no need to turn its knob.

He could not, however, keep its hinges from rasping. But in a breath-locked instant of listening he heard only the low, barely perceptible rumble of the city night and an unbroken chorus of snores.

Grasping a wire he had worked loose from his cot spring, he reached through a tangle of broom and mop handles to the wall, which was the wall separating the closet from the dormitory. The wire found a crack in the wall, slid between mouldering laths, bit at old plaster.

When Vic shut the door again, a pinpoint of moonlight starred the cupboard's black back wall. In a line with that tiny hole was the cot to which someone would come, tomorrow evening, to exchange three decks of cut cocaine for a ten dollar bill...

THE next day, Vic continued at his job of copying records. The same sour, dusty smell lay heavy in the office. The same yellow ledger pages were brittle under his hand. Ben Green, the clerk, played the same interminable solitaire on his desk. Dink Marvin, Rod Landers, and Shorty Allison mumbled their leering yarns, not quite the same but no more appetizing.

At about ten, Dink Marvin went into the outer office, to a phone booth there. No one tried to stop him. No one made any attempt to listen in on him.

That, Vic thought, was pretty nice. When he was ready to leave there all he'd have to do would be to call Dan Staine and get him to spring him.

Marvin came out of the booth, slouched toward the reception desk, and was hidden by the intervening wall. Vic finished a card, took another from the pile of blank ones, turned a page of the big book from which he was copying police records. Suddenly, his name, Dunn, leaped out at him from the grimy page.

But it was not quite his name, "Ptrlmn. John Dunn, arresting officer," it read. He looked for the date.

"Hey, Ben!" Marvin exclaimed, his voice interrupting. "D'juh hear about Pop Morse?"

"Yeah," Green grunted. "I heard."

"Why'ncha tell us?"

The horse-faced clerk put a red card on a black one, counted off three from the deck in his hand.

"Why should I? You bums is all alike to me. One goes, another—"

"What about Morse?" Vic broke in. "What's happened to the old man?"

Green looked around at him, face muscles tightening.

"What's it to you?"

Vic came up out of his chair. "What happened to Pop Morse?" he repeated, huskily. He took a stiff-kneed step toward Green. "I want to know."

"Okay, okay, you don't have to get het up about it. He was found in the alley behind the kitchen this morning."

"Found?" I got to see a man about a rat, Matt had said. "Dead?"

"You'd be dead too if you took a tumble like that."

"Like what?"

"Twenty feet to concrete, from that ledge that runs back of the mail-room windows. Back of his skull was busted in and his neck was broke. Way they figure it, he crawled out on that ledge during mess and tried to snare something out of the mail-room between the bars. They say he was killed right off, even though nobody found him till they started changing guards, midnight."

"But he was right behind the kitchen, you said. Didn't anyone hear him fall? Or yell?"

"Nope. Guess he was too scared to yell, slipping off like that."

Vic pulled in breath. "Or—maybe he didn't slip off. Maybe he didn't fall."

He knew it was a mistake as soon as he'd said it. The others stiffened.

Ben Green growled, "Just what do you mean by that, Mister Nudd?"

"Nothing." He twisted his lips into an apologetic grin. "I guess I just got knocked off my trolley for a second." He was here to do just one job, he had no right to let anything interfere with it. "I kind of liked the old goof, even if he was crummy."

"Crummy's right," Dink Marvin agreed. "I heard he hadda puts rocks on his blankets to keep 'em from walkin' away."

The laugh Marvin's remark brought eased the tension and Vic made himself join in it, but returning to his work, he thought of what Captain Staine had told him. A cop's judgment was apt to be warped if his emotions got tangled up in a case. The very first chance he'd had, he'd proved Staine right.

DISCOUNTING Rawley's sinister-sounding remark, Morse's death well might be the accident the authorities had pronounced it. The mail-room was where the old man had procured the shoes Vic had on his feet. He apparently was in the habit of stealing from the mail-room, and had tried it once too often.

But how had he been so certain he could supply Vic's exact size?

Vic made himself stop thinking about it. Whether Morse had died or been murdered, it had nothing to do with his mission. That mission was coming to a head tonight when, hidden in the broom closet, he would spot through the peephole in the dormitory wall whoever it was that made delivery of the "snow" he had ordered from Rawley this morning. That would be at suppertime. But he'd have to lay the groundwork for his absence from the mess hall, so he could hide in the broom closet.

Lunch, slices of a leathery substance that posed as ham, soggy bread, and a tepid liquid that was supposed to be coffee, gave Vic a chance to expound in precise and picturesque detail what "these here slops" were doing to his digestive system.

"If I ain't feelin' no better by tonight," he announced, "I'm gonna pass up chow. I'd rather have an empty stomach than put any more of this poison in it."

Back in the office there were more cards, more yellowed pages. Along about mid-afternoon, there came a sharp whisper from the outer room.

"Watch it, Ben! Company."

By the time Vic looked up, Ben Green had swept his cards from the desk and was busy filling in some form.

"That's only our file and record room," a deep-chested voice said, just outside. "Nothing to interest you."

"But I want to see absolutely everything, Warden Johnson." That voice, lilting and youthful, was somehow familiar. "I'm sure you don't mind."

The owner of the voice was through the doorway then, and stopped just within the threshold. She was long-limbed, slender, her head canted in the silver-gray fur of her jacket's collar. It was Ellen Staine. Her dark hair was windblown, her eyes a deeper blue than when Vic had last seen them blurred with drowse. Those eyes found him, passed on—came back. Ellen Staine's brow puckered and her dusky lips parted. But a voice interrupted. "Come on, kid. You're wasting time." The man whose impatient exclamation forestalled what Ellen had been about to say was about thirty, his mouth sensuous. "I want you to see the shops before they close down."

"And the cells too, Tom. I especially want the warden to show us the cells."

"There are none, Miss Stone," the warden said. "We've dormitories here." He was portly and pompous. "And I'm sorry but our rules do not permit the dormitories to be visited."

Tom laughed. "Rules be hanged, George. You make them and you can break them."

His hand urged Ellen out of the room and Vic relaxed, listening to his voice trail away.

"You needn't bother sending anyone with us. I know my way around this joint..."

That had been close, much too close for comfort.

"Some babe," Shorty Allison was murmuring. "What wouldn't I give for a chance to—"

"Who's the gink with her?" Vic said. "He acts like he owns the dump and the warden thrown in. Who does he think he is?"

"Search me," Shorty shrugged. "How about it, Ben? You know him?"

"I've seen him around." Ben Green fumbled in the drawer into which he'd thrown his cards, and brought them out again. "How's about you birds layin' off the yakatayakata an' doin' some work in here for a change?"

"Aw, keep your socks on," Dink growled. "So you don't know who the gink is, so what?"

But Vic wondered if this were the real reason for the horse-faced clerk's reticence. And, gazing blankly out the doorway where Ellen had stood for a pulse-stopping instant, he wondered about the warden's calling her "Miss Stone." It sounded, to be sure, very much like "Staine," and the error was natural enough—except that Warden Johnson should be too familiar with the veteran police officer's name to make the error.

Had the girl been introduced to him as Miss Stone? If so, why?

The outer door opened. Past a shawled woman who peered in, uncertain, timorous, Vic glimpsed a car parked just within the wall's iron gate, a low-slung, cream colored convertible. It could be—it undoubtedly was—the same car that had passed him two nights ago, slowed as if about to stop at the Staine house but picked up speed and purred around the corner.

THE car must have stopped that night where the long, unfenced stretch of backyards opened into the side-street. It must have dropped Ellen off and she'd darted to a basement window of her own home, to enter that way, so that the father, whose cigar she'd seen glowing in the room facing the street, would not know she was returning. Ellen didn't want him to know she'd been out with the semi-criminal, the cheap politician he'd forbidden her to see.

She had not deceived Dan Staine, but he'd chosen to let her think she had. Well, Vic told himself, that was of even less concern to him than Pop Morse's misadventure. Ellen would not, he felt sure, betray him. Nevertheless, an inexplicable dull depression settled down on him, rode him the rest of the afternoon. When work was done, he hurried up to the dormitory.

He would have plenty of time, Vic figured, to deposit under his mattress the ten he'd extracted from his trunk-strap money-belt and conceal himself in the broom closet before his dormitory mates showed up. The only trouble with that plan was that, as he turned from his cot, Matt Rawley entered and called to him.

Vic's face muscles tightened, but by the time he'd reached the blond man he'd contrived a smile.

"Hi, Matt. What's up?"

"I hear you been griping about the grub."

"You don't miss much, do you?"

"Nope." The corner of Rawley's thin mouth moved, as if in a one-sided smile. "Is it worth a fin to you to eat decent the rest of the week?"

"Guess so."

"Gimme."

Vic dug a five out of his pocket, handed it over. Rawley ran a palm over his hair.

"Okay," he said. "I'm washing up and then we'll go down. You're eating with me."

He was stuck. He couldn't get out of this in any way that would not awaken the suspicions of even a moron.

Following the blond man downstairs and across the filling mess hall, he found himself at a table near the entrance to the kitchen.

The food was about the quality served in a roadside diner, and so was infinitely superior to what was being handed out at the other tables. Two men Vic hadn't noticed around before shared it with them. Carl Tarr, tall, cadaverous, with a pickpocket's eel-like fingers and the habit of looking anywhere but at what those fingers were doing. Joe Grant, squat, broad-shouldered, his nose flattened, his ears shapeless lobes.

Their conversation consisted of grunted demands for salt, bread, and the sickly amber salve that passed for butter. Vic considered making some excuse to leave the table, gave up the idea. He joined Rawley in a second cup of coffee—real coffee—and returned to the dormitory with the blond man still beside him. He watched a hot round of stud, yawned, drifted to his cot and sat down on its edge.

He slid his fingers under the head of the mattress, touched paper. The paper wasn't folded. He drew it out, cupped in his hand, and glanced down at it. It was his own ten dollar bill.

It seemed to Vic that the big room had suddenly hushed, that everyone in it was watching him. He forced himself to look at them.

But no one was paying any attention to him, not even Matt Rawley, banking a game of twenty-one at the last table, near the washroom door.

Rawley, apparently, had forgotten to pass along his order. Or it could mean that there had been some other slip-up which had nothing to do with Vic's being what he was. The one thing he could not afford to do was ignore it. That would be sure to arouse suspicion. Or confirm suspicions that were already aroused.

HE rose, ambled out into the aisle and down toward the blond man.

"Nudd!" someone called, hoarsely, from behind Vic. "Joe Nudd."

Vic stopped, turned, and saw the blue-jowled keeper who'd originally brought him here, the one called Josh.

"Okay, Nudd," Josh said. "Get your stuff."

"What stuff? What I own, I got on me."

"Come along then. We're moving you to another dorm."

Was Staine pulling him out of here? Or—?

"What's the big idea?"

"Orders. Get going."

Vic went ahead of the guard, out to the landing, and down two flights of stairs. He turned left into the dim, empty corridor, but Josh stopped him.

"This way, Nudd," Josh said. "We're going across the yard."

The keeper unlocked the heavy oak door opposite the foot of the stairs, pulled it open, and Vic stepped outside.

He heard the door thud shut, and then wheeled at a curious, crunching sound.

The keeper was falling, limp as a sack. Carl Tarr stood over him, a stubby blackjack dangling from his hand. An arm grabbed Vic from behind, clamped on his throat and dragged him back, bending his spine over a knee that jabbed into his kidneys.

"Easy, Joe," Tarr murmured. "Take it easy or you'll snap his backbone. That ain't the kind of mark we want showin' on a corpse."

HOKING, helpless, Vic Dunn watched Carl Tarr come closer.

"The way it will look, copper," Tarr said, "is that you conked the screw, tried for a powder over the wall, missed, an' come down with a crack that spilled your brains."

His long arm rose, paused to measure the blow of the blackjack dangling from his pallid fingers.

Vic grabbed for the man who was holding him from behind. Getting a hold, he kicked out with both feet at Tarr in front of him. The blow caught Tarr in the midriff. At that instant Vic jerked back his head against the top of Grant's skull.

The throttling arm released Vic and he fell. But he twisted up immediately. The man who had grabbed him from behind was Joe Grant, the pugilist. Vic let fly a fist at his fat-layered solar plexus, straightened him with a short-armed jolt to the jaw. Then he swung about toward Tarr.

He needn't have bothered. Tarr was sliding down along the door to which Vic's kick had hurled him, his hands convulsively pressed to his abdomen, his face frozen in agony.

Joe Grant, too, was down. Down and out.

Vic snatched up the blackjack that had fallen near his feet. Darting around the corner of the building out of which he'd stepped into a death trap, he headed across an open space to the looming barrier that closed the yard.

It had been the instinct, the habit and training accumulated in a dozen commando raids that had saved him. But he knew his swift and silent victory did not mean that he'd cleared the way to go on with his mission but that his mission had ended in failure. Tarr had called him "copper." He was known to be a police agent. He could accomplish nothing more here.

All he had found out was something his antagonists did not bother to hide, that Matt Rawley was the contact man for the dope ring. He didn't know even whether Rawley was part of the main ring. Nor had he uncovered the slightest hint of how the drugs entered the Workhouse. He'd failed completely and if he didn't get out of here, at once, there would almost certainly be another attempt on his life.

He could, of course, raise the alarm, tell what had happened, reveal to the prison authorities that he'd come in here secretly, without the warden's knowledge or consent. But that would tip off Warden Johnson that he was mistrusted by the police. If the warden was in any way involved with the mobsters it would send him—and them—to cover. He had no way of contacting Staine, the office was closed, and he could not reach the phone booth there. What was that Tarr had said? "The way it will look is that you tried for a powder over the wall."

Could that mean that there was a way to get over the wall unseen? Was that the way the cocaine was smuggled in?

Vic turned to study the forbidding barrier in whose shadow he crouched.

The ancient mortar had crumbled out from between the wall's granite blocks, had left finger and toeholds amply sufficient for one who'd climbed the smooth concrete of a Siegfried Line bastion under fire. Yes, he guessed he could reach the top all right.

But there he would come into the bright beams that were laid along the top of the wall from booth-like shelters at each corner. Not so much as a rat could cross through that brilliance if the guards were alert. Were they? The sentry boxes themselves were dark. Vic grunted, and abruptly moved along the wall toward the nearest corner.

He reached it and almost without pause started climbing. Behind him, somewhere, someone shouted and there was a sound of running feet. Vic gained the wall's summit, hung there precariously, his eyes just above the capstone.

The floodlight lamps, he saw now, were bracketed to the sides of the sentry box just below the sills of its wide windows. Beneath those windows, narrow but not too narrow, lay strips of blackest shadow. Squirming across at the foot of a booth, a man could not be seen by its occupants, and would be concealed in darkness from the guards at the next corner.

He pulled himself over the edge. A loud bell exploded above him, was cut off as someone lifted a receiver.

"Yeah," a bored voice drawled, then was taut. Shocked. "The devil you say!"

"What's up, Jim?" another voice asked. "What—?"

"Breakout," the first one snapped, paused, spoke again. "Cap says if we spy him trying to cross—shoot to kill! He's bashed in Josh Rosling's skull and near bumped a couple of prisoners who tried to stop him. He's—" But Vic was too far down the wall's outer face to hear any more.

HE dropped off into waist-high, lush grass. Light lashed out to his left, struck out of darkness the lonely side road that curved across untenanted swampland to the Workhouse gate. The light spread toward Vic but he was moving in a swift crawl through the miniature jungle of reeds and rushes, outdistancing it. Once more he was fleeing through the unfriendly night, his nerves and stomach knotted in expectancy of a shout of discovery, a screaming bullet.

Whether someone had stumbled on Tarr and Grant and their victim, or Tarr or Grant had recovered consciousness and raised the alarm, it made little difference. Vic was only one witness to the truth. They were two to swear that it was he who'd slain the guard and knocked them out when they rushed to Josh Rosling's aid. They were convicts, true, and he an officer, but how could he explain why, having witnessed a murder and overcome the killers, he'd fled the scene?

He'd not even have the chance to explain. If he tried to surrender, the guards, panicky, revengeful for the death of a comrade, would obey the order he'd heard repeated, "Shoot to kill."

A new sound started. The prison's whistle was raising the alarm for a murderer, for a man known as Joe Nudd. Vic's only safety was to beat that hunt, to make good his escape. Joe Nudd could vanish then, reappear only when the stage was set for his testimony that would convict Tarr and Grant and Rawley for their killings.

He was, Vic realized, indistinguishable in the weeds. He stood up cautiously and peered back. The Workhouse windows were all ablaze. A searchlight's bright ray lanced from a tower atop the main building and scythed the blackness. Yellow light abruptly slitted the wall's looming blackness, widened. It was the gate opening. Motor thunder drowned the whistle's ominous hoot and a packed black car surged out onto the road.

It slowed after a hundred feet, dropped a passenger, repeated this twice within the next two hundred feet, then roared out of sight toward Western Boulevard, a half-mile distant. The men it had left behind were clearly outlined by the light behind them as, rifles held taut across their bodies, they hurried into the grass.

The fools, Vic thought. If he had a gun he could pick them off one by one and they'd never know what hit them.

A police car's siren wailed, long-drawn, threatening, from the direction of the boulevard. Another siren wailed fainter, more distant. The net, he knew, was closing in on him. Nevertheless, a queer sense of elation tingled through his veins. This was a game he knew.

THE yellow flame of a bomb-flare danced at the edge of Western Boulevard, its light flickering on the low thicket of bushes which lined the wide concrete highway's ditch. Another flare burned at the center of the highway, a third on its opposite shoulder. A green squad car was parked between the line of flares and a signpost ten feet away whose arrow, pointing up a side road, bore the words, City Workhouse.

"What gets me, Mart," remarked one of the two uniformed policemen who sat on the squad car's running board, "is why the devil that bozo goes an' bumps a screw just to get out of doin' a thirty-day stretch. He must be nuts."

"Or junked to the eyeballs."

"Junked?"

"Sure. That coop's lousy with the stuff. They say even if a guy ain't a hop-head when he gets sent in there, he's sure to come out itchin'. Watch it, Stan. Here comes a truck."

The first speaker stood up and moved out into the roadway, waving a flashlight. The enormous trailer-truck that roared toward him slowed and stopped. From the truck's high cab the driver called down.

"What's up, flatfoot?"

Stan's light hit him in the face. "You pick up a rider anywheres along here?"

"It would cost me my job if I did. 'No riders' the company says and that's me, 'No riders.'"

Mart moved along the truck's side, between it and the ditch, his torch-beam flickering on the truck's transmission shafts, airbrake hose, axles, black struts mossy with grease and road dirt.

"Say, Mac," the driver asked. "What's this all about anyway?"

"Guy broke out of—" Stan cut short at his partner's voice from the trailer's rear.

"How about opening up back here an' giving us a look inside?" his partner was calling. "You don't have to get down, fellow. Just give me the key."

"I ain't got it, copper," the truck driver said. "Looka that sign back there."

Mart's flashbeam hit the brass plaque. It read:

THIS TRAILER PROTECTED BY EKCO THIEFPROOF SYSTEM.

LOCK AND ALARM UNDER CONTROL OF DRIVER.

Mart clicked off the flash.

"Okay, Stan," he called "Let him go."

Stan stepped back. "Go on," he said to the driver.

He turned off his own light and the shadow of the trailer was black over the road's ditch and the bushes that lined it. The roar of the tractor's motor covered the rustle of the bushes. Gargantuan wheels turned. Tractor and gigantic trailer surged past the squad car, past the arrow pointing to the Workhouse and pounded on toward the city's center.

Choked by gas fumes, pelted by pebbles from the roadbed, Vic Dunn clung desperately to the grease-blackened struts beneath the trailer's belly.

ONE-TIRED, Vic sat slumped in the old leather chair in Captain Dan Staine's little room.

"I dropped off when they stopped for a red light on Rand Avenue," he finished, "and dodged here by the back streets." He watched gray smoke trail from Staine's cigar, feed itself into the fog that had filled the room as he talked. "The first piece of luck I've had is not being picked up for a vagrant." He rubbed at the grease on his trouser knee and added, miserably, "I've sure turned out to be an A-number-one dud."

Staine's wrinkles seemed etched more deeply, but his gray eyes were expressionless.

"Where you went wrong was boring that hole in the back of the broom closet. This Rawley spotted you. He didn't let on, but that was what knocked over the pushcart. He laid for you, and—"

"No," Vic interrupted. "He wouldn't have let me live through the night if he'd known I was a cop. He wouldn't have dared let me hear about Pop Morse's death after he had pulled that line about seeing a man about a rat. Rawley was telling me he was going after the old man, and he couldn't guess I'd let it get by as an accident."

"I'm not so sure it wasn't, Dunn. Why should Rawley go to murder just because Pop Morse was muscling in on one of his rackets? He'd beat him up, maybe, but not kill him. It doesn't make sense."

"No, it doesn't. But—" Vic cut off. "Or maybe it does," he mused. "There's one way it would. That's if these shoes were tied in somehow with the drug traffic. If—" He bent suddenly, tugged at the laces of a mud-clotted oxford. "Hold it. Hold everything. I think I've got a hunch."

The shoe came off. His trembling fingers explored its lining, its sweaty inner sole. He turned it over, tugged at the rubber heel. It came away—too easily.

"And the hunch pays off." Vic came up out of his chair, thrust the shoe at Staine. "Look."

The leather base to which the heel had been attached was a mere shell. It had been carved out to the insole, leaving a rim only just wide enough to hold a single arc of nails.

"There's your answer, sir. That's how the coke's getting into the Workhouse."

A gnarled hand took the shoe from him. "Yeah. Looks like you've got it. They can pack a devil of a lot of snow into a couple of heels hollowed out like this."

"And they probably did the cutting inside, with sugar swiped from the mess hall and ground to a powder." The whole setup suddenly was clear to him, sharply defined. "They only need to mail in a couple of pairs a week, each package addressed to a different inmate. It doesn't matter which inmate because the addressee doesn't know anything about it. Rawley's got someone planted in the mail-room to intercept the gimmicked shoes and dig out the junk."

"And then," Staine took it from there, "he tacks the heels back on and the so-and-sos sell the shoes as a sideline—"

"The devil they do! The heels might come off or wear down to the cavities and somebody'd start asking questions. What they do is cache them somewhere till they can get rid of them, and that—" Vic's eyes were sultry—"is how poor old Pop Morse stuck his neck out. When Rawley caught him giving—or selling—this pair to me he realized the old man had gotten into that cache and he jumped to the conclusion Pop knew a lot more than I think he did."

"So he had him rubbed out, and when you raised a holler about it this morning, he decided he'd better shut you up too."

Wrong, Vic thought. He'd said nothing that would indicate to Rawley he was a policeman. But Ellen had said something to her escort about having seen Vic before, in her father's den, and had been overheard by some accomplice of Rawley's.

"Maybe," he stalled, still reluctant to tell Staine of his daughter's visit to the Workhouse. It would serve no purpose other than to disturb the father and make trouble for the girl. "It doesn't make much difference though, does it? What's important is that this is the break for which you've been waiting two years."

"But you say these shoes are mailed direct from the store."

"From the Maclin store, Captain. Rawley knew they were Maclin shoes before he could see them clearly. That means some Maclin clerk's tied in with the mob."

"Hmm." Staine puffed smoke. "Makes sense," he decided. "But we're still not far along. There are fifteen or twenty Maclin shops in the city, and I can't pull a tail on everybody who works in all of them."

"You don't have to, sir. Those chain stores all keep very careful records of everything they sell. They're sure to have records of their insured parcel post shipments. You can put one man on looking over those sheets and when he turns up the one shop that's making a lot of shipments to the Workhouse, you can concentrate on its employees."

Three perfect smoke rings whirled into nothingness. "Good enough," Staine said. "But you'll have to have an excuse for looking at those sheets, or you'll tip our hand. There's that hatchet murder down in New York. It was spread all over the tabloids this morning. You could say they found a Maclin shoe on the leg they fished out of the Hudson River and we've been asked to trace if it came from here. How's that sound to you?"

Vic grinned happily. "It sounds good."

"That's it, then. You'll get at it in the morning." Dan Staine stubbed out his cigar, pushed erect. "Get that other shoe off. It's evidence. And come on upstairs to clean up. The thing you need now is a decent night's sleep. But the way you look now, you'd never get home. The first harness bull you passed would remember there's a general alarm out for one Joe Nudd and pick you up."

WALKING the three blocks to Rand Avenue, the neighborhood business street along which ran his homeward bus, Vic decided his head felt as though someone were pounding it with a felt-padded hammer, his arms as though invisible weights were suspended from them. Captain Staine was right, he needed sleep. Terribly. He stopped for the bus. The avenue was still noisy with traffic, its sidewalks thronged, its store windows blazing. A jeweler's clock said that it was not quite half past ten.

It must have been about seven then when he'd started down the Workhouse stairs with Josh Rosling. Three and a half hours ago. Yes, a lot of things could happen in two hundred and ten minutes. He ought to know that. He'd seen a hundred men die in a tenth of that time. He'd seen a town won and lost and retaken in an hour.

Where was that bus? He looked up the street for it, blinked at a blaze of blue and scarlet neon halfway up the block. JON MACLIN, it spelled. GOOD SHOES FOR MEN.

A car was just stopping in front of that store. A low-slung, cream-colored convertible. Its door opened and a girl stepped out. She went between two parked cars and across the sidewalk, a package under her arm.

Vic Dunn's brow furrowed. It was not at all extraordinary that Ellen Staine should patronize a shop so near her home. What was strange was that she should enter one where only men's shoes were sold, and that the car which had brought her should not wait, but glide into motion again, merging with the seething traffic stream.

If Vic's exhausted brain had been functioning properly, he might have done it differently. As it was, he simply walked up the block and into the store.

A double row of yellow chairs ran back to back down the center of the carpeted floor between walls solid with shoebox fronts. Two harassed-looking clerks were squatted on their little stools before customers only slightly less harassed. A partition cut across the rear of the store and a slender, skirted figure was just going through its door.

Vic went down along the row of chairs, sank into the one at the very end. The door in the partition had swung half-shut. It was lettered, NO ADMISSION, and in smaller characters at the lower right-hand corner of its frosted-glass half panel, H. FASSET, Manager. A man's voice, meek, tired-sounding, came from behind it.

"Yes, miss. What can I do for you?"

"These shoes." She sounded excited, a little breathless. "A friend of mine bought them here this afternoon for his—for someone in the City Workhouse. But when he took them there he was told they couldn't be accepted unless they were mailed direct from where they were purchased. I wonder if you could possibly—"

"Take care of it for you? Surely. If you'll just let me have the name."

"Morse. Andrew Morse. M-O-R-S-E. In care of—"

"Yes, I know the rest. The postage will be nine cents, and ten for insurance. Nineteen in all, miss."

"I think I've the exact change..." Coins clinked. "...Eighteen. Nineteen. There you are." Ellen laughed, embarrassedly. "You must think my friend's terribly stupid."

"Oh, not at all, miss. This sort of thing happens all the time. Not so much here but when I was assistant manager of our Morris Street store there was hardly a week went by—Just step this way, please, and I'll write you a receipt. As I was saying, in our Morris..."

The voice became only a mumble of sound.

"I'm sorry, sir." One of the clerks had rushed up to Vic, distractedly waving a pair of black oxfords. "I'll be with you in just a minute, but you'll save time if you'll be good enough to take your right shoe off in the meantime." He rushed off, muttering, and Vic bent, started fumbling with his laces.

The next moment, the flowerlike fragrance whose name Vic did not know trailed across his nostrils, and then a pair of trim ankles, nylon-sleek legs, twinkled past him. He knotted his laces again, heard the street door thud shut. He got up then and went back through the door in the partition.

A little man, bald, spectacled, turned to him from a shelf-like desk that was bracketed to the sidewall on the left. Vic thrust past him, got hands on the wrapped shoebox that lay on the shelf.

"Is this the package that young lady just left?" he asked.

"Why, yes." The manager goggled at him. "Has—has there been some mistake?"

"Maybe." Vic tore the paper from the box, knocked off its lid. He pawed at the cordovan brogans nested in it. He pulled one out, and wrenched at its heel. "If I'm right—"

The heel held—then came away, and white flakes puffed from a cavity in the leather to which it had been nailed, danced glistening in the light.

"I am right, mister," Vic said fervently. "You don't know how lucky you are that I caught this."

The cocaine had been placed in the shoes while they were out of the store. Fasset would have mailed them to the Workhouse in all innocence, would not by morning have been able to identify the girl who'd brought them there. "This sort of thing," he'd said, "happens all the time," and that made it very clear how the narcotic smuggling was being worked, and that it was done without any Maclin clerk's complicity.

Ellen Staine was one of those working it. Wide-eyed, naive, Captain Staine's daughter had betrayed him to Matt Rawley's killers, had betrayed three good cops to death, perhaps a fourth—perhaps John Dunn.

"I—I don't understand," the manager quavered. "What—" He choked off.

Vic turned to him, and stiffened. Beyond the little man another man shouldered shut the partition door, planted his back against it and brought out from under his coat's flap a snub-nosed automatic.

"All right you two," he said softly. "Freeze."

He was the man with the sensuous mouth whom, in the Workhouse office, Ellen had called Tom. Too late, Vic realized that the driver of the convertible must have kept a lookout after he had dropped the girl. The driver had spotted him, had watched him follow Ellen into this store.

HE shoe store manager quaked. "Don't shoot," he cried. "I'll get the money out of the safe."

"Cut!" the intruder snapped. "You'd like this to be a stickup, but it ain't." His free hand pulled a gold-colored badge from a vest pocket, put it away again. "I'm the Law. Detective Sergeant Layden, City Police." His eyes, brown agates, moved to Vic. "And you're Joe Nudd, wanted for murder." The eyes dropped to the shoe in Vic's hand. "Looks like I've hit the jackpot."

"Looks like it," Vic agreed. "The fellow might be a cop at that, and an honest one, played by the Staine girl for a sucker."

"So what?"

"Pack those shoes up and don't try any funny business. My trigger finger's nervous."

He was smart. He was keeping six feet back. Vic shrugged, turned and put the shoe and its heel back in the box, very carefully. He wrapped the paper around it.

"Where's the string, Mr. Fasset?"

"Never mind that, Dunn," Layden put in before the little man could answer. "Pick it up and let's go. Both of you."

"No," Vic said wearily. "I don't relish the notion of taking a ride with a lead meal at the end of it. If you're going to iron us out, you'll have to do it here."

Heat lightning flickered in Layden's eyes and the knuckles of his gun-hand whitened, but Vic went on, smoothly.

"You're too smart to do it, though, Layden. You know you could get me and Fasset, but the clerks outside would hear the shots so you'd have to blast them too, and Rand Avenue's too jammed with traffic for a quick getaway."

"Wise guy," Layden grunted. "I—"

The doorknob behind him rattled and the door itself started to open, was stopped by his back.

"Eleven o'clock, Mr. Fasset," someone called through the opening. "Time to quit."

The automatic swayed to the manager. "Stall them."

Fasset licked his lips, got out, "Just a minute, Ned. We're talking business."

The door clicked shut and Layden prowled away from it, past the clothes-hung hooks on the wall opposite the desk to a stack of wooden cases against which he leaned.

"Get rid of your clerks," he murmured, "or I'll have to. Shots in here won't be heard out in the street."

His gun was concealed in his coat-pocket, but he could shoot through cloth and he still was too far away for anything but a frantic gamble on which Vic had no right to bet three lives beside his own.

"We've got to play along," he told the whimpering Fasset, "Tell your clerks we're brass hats from your Central Office discussing changes in operation. Tell them we're going to be here quite a while yet but there's no reason for them to stay around."

"Now you're on the beam," the gunman said. "Now you make sense. Talk up, Fasset."

The manager sounded almost natural, relaying the message. Layden watched the clerks as they exchanged store coats for street clothes, but they were too dulled by their long day, too eager to end it, to notice anything wrong. Acting the big shot from the High Command, Vic told them to turn out the lights in the front of the store as they went out.

"And throw the latch on the street door. We don't want any customers barging in."

Vic sighed with relief when they were gone. He would have felt better if he could have got the bespectacled little man safely out as well, but that couldn't be done.

"Thanks pal," Layden grinned, his gun in sight again. "Thanks for fixing it for me." The shot was a flat blow against Vic's eardrums and Fasset squealed like a stepped-on puppy as he sprawled sidewise and down.

An iron case-opener Vic had snatched from the shelf-desk cracked Layden's wrist and Layden's second shot pounded harmlessly into the floor. Then Vic leaped at him. The flash of his hand was too fast to see, but the killer crumpled, hit the floor with a dull thud and rolled atop his gun. Scarlet fluid filled the cup between his nostrils and pouted upper lip, streamed down over the round of his cheek, dwindled to a trickle as Vic, kneeling, pressed temporal arteries with the balls of his thumbs.

He turned his eyes to where Fasset sprawled atop a shambles of crushed cardboard boxes, his glasses gone.

"Okay, Fasset. Knot a couple of shoelaces together and give them to me. Step on it. This judo's tricky stuff and I've got a lot of questions to ask our friend here before he cashes in."

The little man's mouth spewed sounds that had no meaning, then made words.

"Laces. I'm dying and you want—"

"The devil you're dying. That pain is in your bottom where I kicked you out of the way of his lead. Pull yourself together and get me those laces."

NOOSED tightly around Layden's forehead, the black cord stopped the blood flow. His pulse was feeble, but steady.

"He'll do," Vic decided, "till we can have a doc look him over. But I don't think he'll be passing himself off as a cop again for a long time."

"How—how did you know he wasn't a cop?" Fasset jittered, hovering over him. "He showed his badge, didn't he?"

"He knew that stuff in the shoe was cocaine. If he was a police detective, he wouldn't have left here till he had one of your clerks phone Headquarters to get the Narcotics Squad here to take over, search the premises for more. And he wouldn't have tried to take the two of us out of here single-handed. That badge—well, let's look at it." He fumbled the metal shield out of the unconscious man's pocket.

It was a police badge. It was the badge of a sergeant of detectives and on the back was engraved the name, Thomas Layden.

His face a tight mask, Vic rose. He stepped to a telephone at the far end of the shelf desk.

"I've got a confidential police call to make," he said. "Please go outside and sit down way up at the front of the store, where you can't hear me."

THE little man looked as if he were going to refuse, but he did not. He stumbled through the partition and out into the darkened store. Vic got his hands on the phone, dialed a number. The ringing signal burred twice and cut off and he heard, "Police Headquarters. Information."

"This is the Gray Squirrel Inn," Vic said. "We've a gentleman here asking us to cash a check for him. He says he's a police detective and he has a badge all right, but the Hotel Association's warned us about a confidence man out West who's been using that stunt to pass rubber checks, so I'd like to verify his credentials. He says his name is Layden. L-A-Y-D-E-N. He's about five-ten, brown hair, brown eyes."

"Yeah," the voice said. "That's Tom Layden. He's a detective all right, on the Gambling and Narcotics squad. Give him what he wants, mister."

"Thanks." Vic hung up, stood with his hand on the hard rubber. He should have called Captain Dan Staine. He should call Staine now, but something was keeping him from doing it. What? He remembered. Layden had dropped a single word that didn't fit into the pattern which otherwise was so clear. Because of that word, Vic had to find out something before he called Dan Staine.

He went back to the unconscious man, squatted down and loosened the cord around his temples. The clotted blood in his nostrils stayed dry. Vic slipped the lace off altogether, and used it to lash Layden's wrists. He got up and found another pair of laces. From a metal first aid box that hung on the wall beside the clothes rack he got a roll of adhesive tape. He bound Layden's ankles with the laces, tore a length of plaster from the roll and stripped this over the renegade detective's lips, pocketing the rest of the roll. He retrieved the automatic from under the man's body, saw Fasset's glasses, miraculously unbroken, and picked them up. He went out through the partition and along the row of chairs toward the manager.

Fasset saw him coming and scrambled up, exclaiming, "You—! I just realized that, with that kick, you saved my life at the risk of your own. You didn't know he'd shoot at me first."

"Think nothing of it," Vic smiled. "That's what I'm paid for. Here's your specs. You see, I'm a real cop, not a phony like that guy in there, and it's my job to protect citizens. How good a citizen are you, Mr. Fasset?"

"I—well, I try to be a pretty good one. Why?"

"Because I need your help and it's going to take nerve. How about it?"

The little man fumbled his glasses into place. "What do you want me to do?" he asked, quietly.

"I've got to go somewhere and tie up a loose end of this case before that thug's confederates find out what's happened to him. There are reasons I can't give you why I can't call in outside help. What you can do for me is simple. Just watch him and that shoebox till I get back. Here." He gave the little man Layden's automatic, showed him how it worked. "You won't need it, but you'll feel safer having it. Okay?"

"Okay."