RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

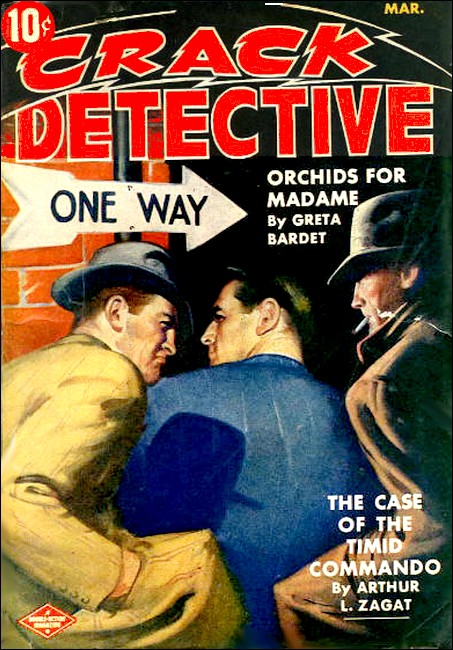

Crack Detective, March 1943, with "The Case of the Timid Commando"

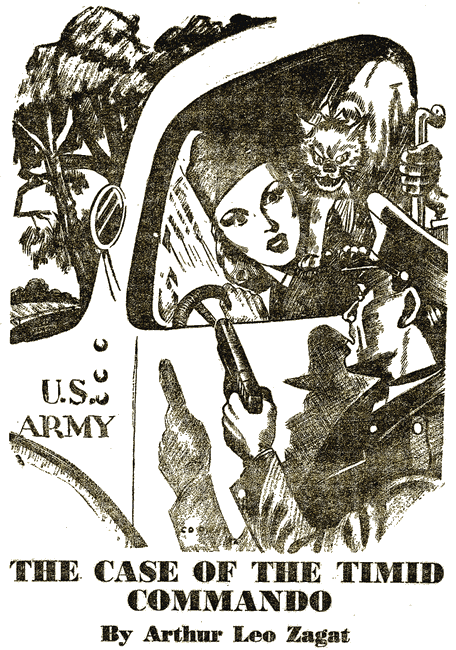

B. & B. Detectives, and their cat, Sinbad, solve the

mystery behind a fighting man's sudden loss of nerve.

IT was a veritable behemoth of a truck, blunt-nosed, a dull olive-green; it stood in the camp road as ugly as the Puritan's concept of sin. Passing soldiers looked at it—looked again and whistled softly. "What a dream!" one exclaimed; another, "Mama! Ain't she somethin' to write home about."

The feminine pronoun did not refer to the truck, even though it bore the insigne of the American Women's Voluntary Services. Pronoun, and admiring remarks, appertained to the occupant of its driver's seat.

Trim in gray-blue uniform, canoe-shaped cap perched jauntily on hair the mouth-watering shade of sage honey, tip-tilted little nose impudent over a damask-rose dab of mouth, Betty Marvin was for once oblivious of male adoration. Her eyes, cornflower blue, were riveted anxiously on the door of the long, low building before which the truck had been waiting an hour.

Beside her, a furry bundle the exact color of her hair heaved, uncurled and became a huge cat stretching lithe muscles. "Mrreow," it commented in a deep-chested baritone, looking up at its mistress with eyes blue as her own.

The girl stroked the cat, but her gaze remained on the door with the stencilled words, Medical Detachment. "All right, Sinbad." Her voice was silver. "They'll be through with him soon." A silver wire stretched almost to breaking. "We'll soon know—" It caught in her throat.

The door was opening.

Ben Marvin came out of it and across the board sidewalk slowly, as if he were very tired. Sunlight glinted from his lieutenant's silver bars, struck into sharp relief the weary lines cutting into his dark, sharp countenance. His uniform was impeccable, his black mustache needle-pointed and intransigent as always, but his left leg dragged a little, its knee stiff.

A silvery little laugh greeted him as he reached the truck. "Pay me," Betty chuckled, her tenseness gone. "One hard, round quarter."

"Yeah," Ben grunted. "You win," He put the coin into her soft palm. "They marked me unfit for duty for another month. A month," he repeated bitterly, "Ten cents gets you another quarter the division's overseas by then."

"It's a bet," The girl reached for a gear lever. "Come on, Ben. Hurry. I've got to get Helen Lisbeth back in her stall before the Gorgon discovers I drove her down here." A series of backfires announced the motor had come alive. "She'd love the chance to chuck me out on my—"

"Betty!"

"Ear," she finished sweetly, "Well?"

Ben climbed a little awkwardly to the high seat. "Not that I'm afraid of Mrs. J. Hall-Morris," Betty giggled, "since I found out her bee-orgeous silver hair's a wig." Cogs clashed. "It's lucky, Ben."

"That Mrs. Hall-Morris wears a wig?"

"No, silly." The truck lurched into gargantuan motion. "That you don't have to go back to the army right away. 'Cause I just bought the most beautiful leather blotter-pad you ever saw."

"A leather—What the devil for?"

"Your desk, To keep your spurs from scratching it. If you wore spurs."

BEN pulled in a long, reluctant breath but the pain had eased

from his face. "If you think I'm going to hang around that

triple-be-damned office—"

"It isn't. It's a lovely office and it's ours. 'B.& B. Detectives.' Remember how proud we were when the painter lettered that on its door. And someone might even bring in a case—Oh, look!" Betty braked so abruptly Ben was within an ace of being thrown from his seat, "Look at those soldiers."

The road had brought them to a wide, grassless plateau, where men in baggy battle uniforms, their faces and hands blackened, were sorted off in pairs, industriously endeavoring to commit mayhem on each other regardless of the rules of Queensbury or even those of common decency, "What are they doing?"

"They're playing Puss-in-the-Corner, honey," Ben said sweetly, "to see which ones get ice cream for dessert tonight."

"Benjamin Rowland Marvin! If you expect me to believe any such nonsense—I know very well there's plenty enough ice cream to go around —Oh," she broke off. "That man." Betty's fingers went to her lips. "There. Something's wrong."

"Wrong's right," Marvin agreed. "That's Art Lanning, and—What the hell?"

The soldier had jumped suddenly back from his antagonist, stood rigid now, left fist clenched hard against his temple, right arm stiff along his flank, its sooted fingers working convulsively. His eyes, seeming all whites, stared unnaturally large from his face's black mask and his voice, thin, tortured, came clearly across the field.

"I can't. I can't do it."

"You blasted yellow...." A burly non-com pounded stiff-legged toward the man. "You lily-livered...." An officer caught the sergeant's arm. "Hold it, Jackson." A second lieutenant. "Hold everything, I'll take care of this."

Ben started down off the truck. Out in the field, the lieutenant was saying, "Okay, Lanning." Gently. "What's it all about? What's got into you?"

A shudder ran through the man but he came to attention, saluted. "I don't know, sir." He spoke dully, "All of a sudden I kind of got a picture of me really sneaking up on a guy and breaking his back with that hold and it was like someone conked me with a sledge-hammer. I—" His voice thinned again, was edged with hysteria. "I couldn't do it. Not even to a Jap or a Jerry, I couldn't—"

"Settle down, Lanning." In the background, Sergeant Jackson was bellowing the rest of the detail back to work. "Get a grip on yourself."

"Yes, Lieutenant Corbett."

Corbett sighed. "That's a little better. Now go to your quarters and stay there. I'll have a little talk with you later."

"Thank you, sir." The private was stockily built, rock-jawed, young. He looked the kind that doesn't know what nerves are. He saluted, about-faced smartly enough but stumbled as he started away and went across the field in the curious, blindly groping manner of a sleepwalker.

CORBETT watched him—turned to a tap on his arm.

"Lieutenant Marvin." His bronzed face lighted with genuine

pleasure. "I hadn't heard you were back with us." He remembered

to salute. "I suppose you're taking over the platoon."

"No, Dick." Ben returned the salute, put his hand out for a friendly clasp. "I'm still on the inactive list—look. What's got into Lanning? He's the last man in the platoon I'd expect to put on an act like that."

"Or I." Corbett shook his head. "I've always figured him the toughest hombre of the lot and the Lord knows they're all plenty tough or they wouldn't be detailed to this special Commando course." His hand fisted at his side. "He started to soften up about ten days ago, but this is the climax. Guess I'll have to transfer him out."

"That won't repair the damage." Marvin was looking past the second lieutenant, to where Jackson was roaring at the other men, on the verge of apoplexy. "Look at the rest of your gang. They're just going through the motions. They're thinking of what Lanning said and it's taken all the oomph out of them."

"Yeah." Corbett pulled the edge of his hand across his forehead. "That sort of thing's infectious. But what the devil can we do about it?"

"Find out what's ailing Lanning and straighten him out. That'll cure the others."

"Sure. But how? I—Hold on! I can't get anything out of him, but I've seen him confabbing with old Frazier over at the Red Cross shack. I wonder if—"

"Got it." Ben twisted, was limping back to the truck. "Come on, Bets. We've got places to go and things to do."

"The Gorgon," Betty wailed, but as Ben resumed his seat beside her she asked, "Where to, me lud?"

"The south end of camp. Take that first turn to the left...."

THE white-haired man with the Swiss Cross on his lapels said,

"Yes, Lieutenant Marvin. I know what's bothering Private

Lanning," and stopped.

A muscle knotted in Ben's gaunt cheek. "It's something you can't pass on to me because I'm his officer, and it would be marked up against him."

"No." Frazier pursed thin, sexless lips. "No, if that were so I should not even admit he had talked to me. His troubles do not concern the army at all."

"The hell they don't." Marvin blazed. "They're only ruining a damn good soldier and sapping the morale of the platoon I half killed myself making the best in the division. Listen, mister!" Tersely, he related the incident that had brought him to the Red Cross Field Director. "Now tell me again this is none of my business."

"Your business, lieutenant," Frazier smiled thinly, "is leading your men in battle. The life they've left behind them, the welfare of their loved ones, is ours. We've built a vast organization that reaches into every city and village and rural community in this land to handle that job." His fingers drummed on the edge of his desk. "I think we've been fairly successful thus far."

"Yes," Marvin admitted grudgingly. "You have."

"But I confess," Frazier went on, "that in this case I find myself on the horns of a dilemma." His hand dropped to a drawer, pulled it open. "Arthur Lanning received this letter from his wife about a fortnight ago. On Friday, the twenty-fifth, to be exact."

The writing on the folded sheet of notepaper was neatly formed, the lines forthrightly straight:

Art darling:

There's something I'd like to talk to you about. I'd come down to camp but we're shorthanded and I oughtn't even to miss one shift at the plant, especially with what I do there. Maybe you could get a weekend leave and we could have one of our good old pow-wows.

Something awfully funny happened the other day. I was riding to work....

MARVIN gave it back. "Nothing in this to send a man

haywire."

The rest of the letter dealt with the sort of inconsequential trifles that mean so much to a husband separated from the wife he loves and who loves him, and nothing to anyone else. It was signed, very simply, "Your Mary."

"No," Frazier agreed. "Lanning put in for leave and it was denied. He wrote his wife to tell her so. She never answered that letter."

There was no emphasis in the way he said it, but a chill prickle travelled Ben's spine. "It got lost in the mail," he suggested.

"Perhaps. But it is hardly possible that Lanning's second letter would also meet the same fate. When that brought no response, he came to me."

"Yes?"

"I followed our usual procedure, had our local Red Cross chapter send someone out to make a discreet investigation. The three times our worker called, Mary Lanning was not at home. She had not reported for work since Saturday, the twenty-sixth, when she drew her last pay. We have been unable to locate anyone who has seen her since she left the Atlas Chemical Company's building, that night."

"You have been unable to locate—" Ben Marvin's jaw ridged. "Didn't it occur to you that this ought to be reported to the police?"

"Naturally." Frazier adjusted a fountain-pen stand that needed no adjustment. "But that is up to Arthur Lanning, not to us."

"And he—?"

"Refuses to bring the police into this affair, refuses to permit us to. I offered to tell Colonel Fosdick the circumstances, secure a furlough for him so that he can search for his wife himself. He has refused to permit me to do that. Nor will he tell me why."

"No?" Little light worms crawled in the blackness of Marvin's eyes. "What do you want to bet he'll tell me?"

"Oh look here, lieutenant. You can't—" Frazier didn't finish the sentence. He had no one to whom to finish it. Ben Marvin had slammed out of the little office.

"Okay, hon?" Betty smiled down at him. "Are we going home now?"

"You're going home," Ben grinned back at her. "I've got a little matter needs attending to here."

"Then I stay too."

"Unnh, nnh. If you think I'm letting you hand the Gorgon her chance to give you the old heave-to—"

"The Gorgon can go to—to blazes."

"Amen. And you can get going. Pronto!"

The smile died from the girl's lips and under her lucent skin pallor spread. "Are you giving me orders, Lieutenant Marvin?"

"I'm telling you to start this truck back to where it belongs." Black eyes caught, held, cornflower blue ones and there was sudden, silent but intense conflict between them. Abruptly Ben's voice was fuzzy, deep-toned. "Please, Bets."

"That's better," she sighed, and her smile was back. "'Bye honey. Don't do anything I wouldn't do."

Gears clashed. "That isn't restricting me very much," Marvin grinned, and a salvo of backfires drowned his words. The behemoth roared away and pain twisted Ben's face as he bent, grabbed his left knee with both hands and squeezed hard.

"Damn," he murmured. "Damn it to hell," and straightened and moved off, hobbling now like a spavined horse.

As Ben entered the barrack's room a soldier sprang from a cot, stood at attention in undershirt, shoeless. "At ease," the lieutenant smiled and looked past the relaxing man. Two long rows of neatly made cots stretched either side the room, alternating head and foot. There was no one else in sight. "Where's Lanning, Gordon?"

The private's eyes went blank. "I don't know, sir." He fumbled with the arm bandage that explained his own presence here. "I don't know," he repeated, needlessly.

Marvin's eyes came back from the wall above the fourth cot on the right, where a pack hung from one hook but the one next to it was empty. "I take it you don't know," he said and then surprise flared into the soldier's face as the officer's hand went to his own collar, deftly unpinned silver bars. "Get it, Gordon?" Ben asked, warm-toned. "This is between you and me and these walls."

"Yes, sir." Gordon seemed dazed. "Yeah. I get it."

"Art Lanning's gone over the hill, hasn't he?"

THE fellow's mouth opened, closed, opened again, and then the

dam broke. "Gees," he blurted, "He come in here lookin' like the

wrath uh God. I don't think he heard me ask him what was up. The

way his eyes looked, blind kind of, I don't think he even saw me.

He just marched to his bunk and grabbed his holster from the hook

there and stomped on into the latrine in back."

It was Ben's turn to look confused. "The latrine?"

"Yes, sir. You climb out the window in there when the sentry's the other end of the post and you can make it to the woods without his spotting you. We—I—," Gordon swallowed, decided to go the whole hog. "I've got away with it more'n one night when the sarge wouldn't gimme a pass to town."

"I see." The corners of Marvin's mouth twitched. "Well, you'd better not try it too often. I'd hate to see you hauled up before a summary court on charges." The twinkle of humor vanished. "Look here. I've got to get Lanning back on the reservation before he's hauled up on worse charges than just being A.W.O.L. Have you any idea which way he went?" The private spread his hands helplessly. "You go through them woods about a half mile and you come out on the Post Road. You can get a hitch there 'most anywheres."

"Almost anywhere," Ben Marvin repeated, his brow knitting. "And he's had plenty of time to reach the highway...."

"'YOU take the high road,'" sang Betty Marvin as she hurled

the huge A.W.V.S. truck along the wide ribbon of concrete, "'and

I'll take the low road.'" The great blonde cat was once more

curled on the seat beside her. "'And I'll be in Scotland afore

you—' Isn't it weird, Sinbad, to see the Post Road all

empty like this?"

"Mrreow," Sinbad agreed, lazily blinking his extraordinary blue eyes.

"Since camp, we've just seen that one army car that whizzed past us. It's the war, you know. Civilians can't get gas or tires unless—Oh," she broke off. "There's a soldier now, thumbing a ride."

He'd stepped out of the bushes ahead, already lifting his arm to signal her. Fighting the ponderous brake, Betty looked puzzled. "Funny, Sinbad," she murmured. "It almost seems like he's been hiding in there, looking over the cars that come along before showing himself." The truck skidded to a halt and the soldier came up on its steps.

"You going through to the city?"

His nostrils quivered and the quick look he shot into the truck's interior was somehow harried. "The big city, I mean."

"Yes." The soldier was bareheaded and there was soot along the hard line of his cheekbone, as if he'd washed hastily. "Come on al—I know you!" Betty exclaimed. "You're the soldier who—You're Private Lanning." Lanning's mouth greyed, went thin, straight. "What about it," he demanded, flatly.

"You shouldn't be—Your lieutenant sent you to your quarters. You ought to be—" The girl's voice died and she was staring into the black mouth of a revolver clenched suddenly in Lanning's fist. "What—What's that for?"

"For being too blasted smart." The soldier's pupils had shrunk to pinpoints. "You—" The gun pounded, ripped a hole in the truck roof as he was hurled back off the step by a blonde, spitting fury of enraged cat that had exploded from the seat.

There was a soft, sickening thud in the road, a yowl of jungle fury. "Sinbad!" Betty cried, scrambling down. The cat, arch-backed, enormous with bristled fur, lashed a sinuous tail above the soldier's prostrate form. "It's all right, Sinbad. He can't hurt me now. He's harmless."

A long scratch, just beginning to bleed, raked from the tip of Lanning's left ear to the point of his jaw. It was the only visible souvenir of the feline's attack, but he lay very still, very white in the road. Reckless of Sinbad's deep-chested growl, Betty sank to her knees and probed a tawny scalp, her fingers anxious.

SHE let breath filter from between her lips. "Not broken,

Sinbad. He just cracked the back of his head on the concrete and

knocked himself out. He'll be—"

A thrashing in the bushes twisted her to them in time to see Ben burst out, breathless. He saw her. "Betty!" hobbled to her. "Bets, honey. I heard the shot and—You're all right, Bets? You're not hurt?"

"Only my pride, Ben, the way I blurted it out." Her smile was rueful. "'I know you,' I prattled. 'You oughtn't to be here. You're Private Lanning and—'"

"Lanning!" Marvin stared at the stunned man, really seeing him for the first time. "I'll be everlastingly —That's whom I was tracking through the woods. He left a trail plain as Broadway and—What happened, Betty?"

She told him. "He wasn't going to shoot me, Ben. I'm sure he wasn't. He—"

"Hold it, Bets, He's coming back to us."

Lanning had stirred, groaned. His eyelids fluttered open and he looked up, dazedly at first, then with sudden terror as he made out Ben's uniform. He thrust a spread palm against the concrete, shoved to a sitting posture, "Easy," Marvin murmured. "Take it easy, Lanning, I'm not going to turn you in."

"You—you're not—"

"Not unless you persist in acting like a blasted idiot." Ben let himself down, gingerly, to the truck step. "You were on your way to look for your wife, weren't you? For Mary."

"Mary!" The name was an oath, the way Lanning mouthed it. "Hell no! I'm out after the son of perdition she run off with."

"Mary hasn't run off with anyone," Marvin told him. "She loves you too much for that. A hell of a lot more than you deserve."

The soldier stared, Adam's apple working. "Mary loves—What the blazes do you know about it?"

"I read her last letter to you, Lanning. Frazier showed it to me."

"Her letter—" Lanning laughed, curtly. Bitterly. "Yeah. Sweet as honey it was. And phoney as hell."

"Not phoney." Ben denied, gently. "No woman living could fake a letter like that if she didn't love, the man she wrote it to."

"That's what I thought." The soldier was fumbling in a pocket of his battle uniform. "Till I got this and thought it over." He brought out a dingy, crumpled envelope, thrust it at Ben, "Here, Since you've stuck your nose this far into my affairs, you may as well shove it in all the way." He'd long gone beyond distinctions in rank. "Go on, read it."

"I will."

Betty read it too, over his shoulder.

Maybe it's none of my lookout, but being as how you're a soldier I can't help it, I got to tell you. You better get a furlow and come home and ask your wife Mary what she's up to, running around with a greasy little foreigner and going away with him weekends and all.

I think it's a shame she's acting like that when her man's fixing to die for his country.

A Neighbor.

Ben's lips curled with disgust but it was Betty who exclaimed, "How filthy!" She twisted to Lanning. "Don't tell me you put any stock in that—that garbage!"

The soldier had plucked his revolver from the road-bed, was struggling erect. "Maybe it's garbage," he snarled, "but she's gone off somewhere, ain't she? And she didn't go alone." His hand tightened on the gun-butt. "I don't know where to look, but I'm gonna find them, and—"

"No," Ben said, "I'm going to find her for you. If she's alive—"

"If—!" Lanning went corpse-gray. "What do you mean?" His fingers dug into Marvin's shoulder, bruising. "What makes you think Mary's not alive?"

The lieutenant lifted his head to look into the man's face, his slender frame otherwise motionless. "Nothing," he said blandly. "Not a thing. But the thought of her dead hit you smack in the solar plexus, didn't it? The thought of Mary dead, the woman you love so much you were willing to let her go with someone she'd learned to love more than you till the vermin that crawled out of this filth ate into your brain and ate away your love for her." The smile under his needle-pointed mustache was faintly mocking, but his eyes pitied the man. "And made you forget something else, your duty to the uniform you wear."

Ben came to his feet as the soldier's hand dropped from his shoulder. "You're going back to your bunk, Lanning, the way you came—"

"No!"

"And I'm going to find Mary for you," Marvin went on, very quietly, "I'll give you my solemn promise, Lanning, that if I find she went away willingly, with a lover, I'll not only tell you where they are, but see that you get long enough leave to go to wherever they are. Is that fair enough?"

"Yeah." Arthur Lanning's face was the color of putty. "Yeah. It's fair enough."

"Okay. Now, go back to the barracks, I want to ask you some questions...."

THE A.W.V.S. truck pounded down a narrow street of drab

apartment houses, one cut above tenements. "The Gorgon must be

throwing eleven different kinds of fits by now," Betty chuckled.

"I wish I could see her, Ben."

"Yeah—Watch it, Bets. There's four-nineteen, about the middle of the block."

She eased the behemoth to the curb, braked, turned to Ben. "Okay. What now, Sherlock?"

"Now we—Uh, uh." Marvin pulled back from peering out and up from under the roof, "A dame's leaning out of a window up in the third floor."

"So what?"

"And she's got a pillow planted between the sill and her—er—chest."

Betty looked bewildered. "I still don't see...."

"That cushion means she parks there by the day, watching the street."

"Like a few thousand other women in this town that haven't anything better to do with their time, even if there is a war on."

"True, my sweet," Ben agreed. "But this one's leaning out of a third floor window and the Lanning flat is on the third floor—"

"Dear, remember."

"Precisely. Nevertheless, we shall make a slight change in our projected tactics. Listen closely, oh light of my life and consolation of my declining years—if any. Listen to my words of wisdom."

There followed a low-toned colloquy, after which Betty swung lithely down to the sidewalk, crossed alone to the brownstone stoop and climbed it.

The usual row of letter boxes was set into the vestibule wall, brass cubbies faced by tiny glass windows below them, name-plates and under these a row of push-buttons misshapen by many years of thrusting fingers. The girl found the framed slip that said, Lanning 3R, peered into the box above it.

She could make out a white envelope, 'Soldier's Mail—Free' scrawled in the corner where the stamp ought to be. Her eyes narrowed. Then her forefinger jabbed a button, not Lanning's. The one next to it, over which the nameplate read, Ralston, 3F.

She rang once more before the hall door's latch clicked. As she pushed the heavy portal open, Ben arrived at her side. "Mamma's alone in the flat," he murmured. "She had to pull in from the window to answer your ring."

"Yes—Ben. I've been thinking all the time the reason Mary Lanning wrote her husband to come to her was because she wanted to see him again, to help her make up her mind between him and someone else, I thought that when he wrote he couldn't come, that decided her. But I was wrong."

"How'd you make that discovery?"

"She never read his first letter. She was gone before it came. It's still in the box. I could read the postmark through the glass."

"Interesting." They were climbing steep stairs, their feet silent on the carpeted treads, their voices barely audible. "But—Oh, oh. Here's where I stop." They were midway of the flight between the second and third floors, and above them hinges were creaking. "You remember your little speech, don't you?"

The hall door of the third floor, front, flat framed a big woman in a cheap and dingy house dress. "Yes?" Weary eyes, the irises a blurred brown, peered at Betty. "What is it?"

"Mrs. Ralston?"

SHE must have been pretty once; now her straggly hair was the

color and texture of hay that's lain in the hot sun too long, and

the skin at her throat was loose, wrinkled. "Jen Ralston's my

name."

"I'm from the A.W.V.S., Mrs. Ralston." Betty's smile was ingratiating. "One of your neighbors has applied for a certain highly confidential position and I've been assigned to investigate her. I thought you might be able to tell me something about her."

"I can't." The door started to close. "I ain't lived here but a month and I don't know nothing about nobody."

"Oh," Betty interjected, hastily. "You can't help knowing about her. She lives right here on your own floor."

The door stopped moving. "Mary Lanning, you mean?"

"Mary Lanning. You can help me, can't you?"

Mrs. Ralston gnawed an under lip on which rouge was splotchy. "When'd you say she applied for this job?"

"I didn't say." The girl still smiled blandly but in the hollow of her throat a pulse fluttered. "Because I don't know, exactly. But it must have been yesterday or the day before, because we didn't know about this thing till then."

"Yesterday...." The faded brown eyes were peering out past Betty, into the shadows that shrouded the stairs and the woman seemed to be listening for something. "Come in, miss. Come on inside where we can sit an' I'll give you an earful about that—about Mary Lanning."

The flat door closed on the two women. For a moment there was musty vacancy in the stairwell, then Ben Marvin appeared on the landing. His sombre gaze rested on the door of 3, front, for an instant and there was satisfaction in it, and perturbation too, but he shrugged and moved to the rear, to the door of 3, rear, sunk in the gloomy rectangle of a deep embrasure.

Metal clinked tinily. Metal scraped on metal. Breath whispered against the edge of tight teeth and a lock-bolt rattled. Hinges whispered. A vertical streak of light slitted the murk. It widened, silhouetted a slender form in officer's uniform, narrowed again and vanished.

Ben Marvin crossed a minuscule foyer, entered a living-room neatly in order. A window was open inches, a net curtain stirred with the breeze. The furnishings were in as good taste as instalment furniture ever is, but dust lay, a thin film, everywhere.

A confession magazine lay open on the seat of a chair. Gloves and a newspaper were thrown carelessly on a small table. The room looked lived-in, but there was the dust and the dead, empty silence brooding in the flat.

A door in the farther wall let Marvin into a short hall that ended in a bedroom. A window was open here too. A closet was open and gaps in the huddled row of dresses within it, empty hangers, a sequined evening dress huddled forlorn on the wardrobe floor, told a story of hasty departure underlined by dresser drawers pulled half open, trailing filmy pink rayon.

The double bed was made up, but its candlewick spread was rumpled, and a chair had been overturned, scuffing up a Wilton scatter rug—Ben stiffened.

Splotching one edge of the rug and spreading over the shellacked floor was a stain. A dark red stain, dried, flaking at the edge.

"Looks like something violent happened here," he muttered, "and," glancing at the dresser, the closet on whose hat shelf was a vacant space just large enough to have contained a suitcase, "and not to Mary Lanning." He bent, picked at the edge of the stain with a fingernail, sniffed the bit of dried stuff this brought away. An odd, satiric smile touched his thin lips. "Yes," he whispered. "It looks very much like it."

His eyes were black agates....

THE Ralston flat had a smell of uncleanliness, of last week's

greasy cooking, of dirt swept under carpets. "I ain't nosy by

nature," Jen Ralston babbled, "but when a married woman has a

greasy little foreigner comin' to her flat night after night, an'

stayin' to all hours while her own man's in the army, then I got

to take notice."

Betty squirmed uneasily in the upholstered chair, resisted a desire to scratch. "I—Maybe you're not being fair. Maybe this man is her brother."

"Brother, my eye. An' that ain't all. One Saturday night, about two weeks ago it was, she had him in there an' all of a sudden there was a lot of noise, like they were throwing chairs at each other or something, an' it stopped all of a sudden." The Ralston woman leaned forward in her chair. "After awhile," she said low-toned, "Mary Lanning come out carry in' a suitcase an' went downstairs helter-skelter, like she was runnin' away from somethin', but the wop, or whatever he is, never come out at all."

"He didn't!" Betty's eyebrows went up. "I suppose you told the police."

"Who? Me? Say, any time you catch me givin' the cops a rumble—" Jen Ralston cut off as a key rattled in the hall door. "That's Jim," she exclaimed. "I knew he'd be along pretty soon." She sounded relieved.

And curiously triumphant.

The door slammed shut. Heavy footfalls crossed the foyer. A man, not tall but heavily built, face broadly moulded, stopped short in the living room entrance, eyes too small, too wide apart questioning the girl's presence.

"This lady's been askin' about Mary Lanning, Jim." Mrs. Ralston lifted to her feet. "She says she put in for a job with the A.W.—with her bunch, yesterday." Betty was up too, throat dry with sudden, unreasoning panic. "Yesterday, or the day before yesterday, she says."

"Oh yeah?" The man was moving slowly, ponderously, towards Betty. "Yesterday, huh?" The woman was moving toward her too, from the other side and it was as if the two stalked her, mercilessly.

The girl swallowed her cud of fear, contrived a little, careless laugh. "It doesn't matter, Mr. Ralston. Really it doesn't." She turned to the woman. "You've told me all I need know. Thank you." She started toward the foyer, but the man blocked her off.

"I'm gonna do you a favor, honey." His great hand, closed on her arm. "I'm gonna let you talk to Mary Lanning herself." Betty was rigid, as the woman pawed her, searching for a weapon, but there was no earthly use resisting. "Get your duds on, Jen," Jim Ralston said. "Looks like we got to move out uh here—fast."

THE car was a sedan, so old its body squeaked, but its motor

was smooth and powerful. The sedan was so old the layers of

safety glass in its side windows had separated, blurring them so

that anyone outside would have to look hard inside to see that

the slim girl in the back seat was blindfolded and gagged.

As the motor sent the sedan surging through endless meanderings, Betty Marvin tried to shut out the unwashed smell of the woman beside her, tried to forget the feel of the gun in her side as they'd descended the stairs, close together, and crossed the sidewalk to the car. Tried desperately to conceal the fear that sheathed her tantalizing young body with ice.

And at long last the sounds that drummed Betty's ears changed pitch, so that she knew they'd entered an enclosed space, and a door thudded, somewhere outside and the car stopped. Seat springs creaked, up front and the front door squeaked open, slammed shut. Clumsy fingers fumbled at the handkerchief that blinded Betty, pulled it away. Yellow light probed her aching eyeballs, dazzled them.

She heard a wheezy chuckle as the fingers removed her gag. Her vision cleared and through the windshield she discerned that she was in a low-ceiled small room cluttered with old tires, old license plates, empty oil cans. Obviously a private garage attached to some suburban home, but what sort of people lived here that these things had not long ago been turned in for war use?

A door in a sidewall was opening. Jim Ralston came through, thudded to the sedan, pulled open the car-door on Betty's side.

"Come on."

"Where?"

"Come on," Ralston said again and reached in to drag her out. The girl recoiled from the rough paw. "Don't touch me! I'll come."

She stumbled out and, aware that the woman followed, obeyed Ralston as he motioned her to the door out of which he'd come.

THEY went into a kitchen whose blinds were drawn, making it a

place of dim glints, of fearsome shadows. They went across the

kitchen into an entrance hall out of which a gloomy staircase

lifted, and straight ahead a street door was tight shut and

bolted. "Jim," Jen whispered, "Does he want me, Jim?" Something

like terror quivered in that whisper. "Do I have to go in

there?"

"He didn't say so."

"Then I'm not. I'm going upstairs."

"Okay with me," the man shrugged and turned to a wide archway to one side of the hall, pawed aside the heavy plush portières that filled it, beckoned Betty through.

Her throat was tight, aching. Her heart pounded till she wondered it did not break through her rib cage.

Black shades were drawn down tight over deep-embrasured windows but on a ponderous, oblong library table in the center of the breathless room a lamp threw light downwards on the mahogany surface, on the curled lash and ominously heavy handle of a riding crop lying there. Going toward the table, the girl was aware of a shadowy presence seated in the blackness behind it, of the pale oval of a face otherwise undefined.

"Ohhh," she exclaimed, disappointedly. "You've forgotten the candles."

"The candles?" The voice from the darkness was startled. "What candles?"

"We always have candles at my sorority's initiations. They're really very effective."

"Indeed?" At the table now, she could make out the speaker more clearly, painfully thin, head too long, too narrow, long nose sharp-bridged and mouth straight-lipped, cruel. "This is hardly a sorority initiation?"

"Oh, isn't it? When I saw all this hocus pocus I thought it was. What are you up to, then?"

"I'll ask the questions, if you don't mind." The voice was high-pitched, effeminate in a skin-crawling way. "Who sent you to look for Mary Lanning?"

Betty rubbed her thumb along the table's edge, looked at its ball. Her pert nose wrinkled. "Dust," she remarked, disgustedly. "You ought to speak sharply to your maid." She turned to look for Ralston, found him standing spraddle-legged before the archway. "Isn't it terrible, the sloppy way they work nowadays? But then, I suppose you've got to be satisfied with what you can get these days, with the war factories—"

"Young woman!" Exasperation, threat, were mingled in the sharp exclamation. "I asked you a question. Answer it."

"Must I?"

Fingers stole into the pool of light, long white fingers that seemed boneless. "I think you had better." The fingers touched the whip's weighted handle. "Yes, I should advise you to." They fell away into the shadow again.

"I see what you mean. Well," Betty shrugged. "If I must, I must. Here's the way it was. This morning, about eleven o'clock, I heard a tapping on the door, I went and opened it, and who do you think was there?"

"Go on."

She leaned forward, confidentially, left hand on the mahogany surface to support her. "A little green man, ten inches tall—" Her right flashed to the whip's lash, swung its heavy handle at the questioner's dodging head. It thudded dully on bone and a heavier thud signalled a fallen body as the girl whirled.

Ralston's mouth gaped stupidly but as the girl started for him, his paw went under his lapel and before she could get to him slid out again, clenched on a gun-butt. She leaped. The whip cracked on his wrist, thumped the revolver to the floor—

In that instant her foot caught a rug hold, threw her. Twisting to save herself, she lost the whip, hit the floor on hands and knees and saw legs plunging to her, looked up and saw a face contorted with pain and rage, saw a great paw reaching down —Betty threw herself at those legs, hit them with her shoulder just below the knees.

NOT with weight or strength, but the momentum of Ralston's

charge, lightly checked, sent him over her, sprawling, and Betty

lifted almost in the same motion, scooped up Ralston's revolver

by its barrel. Fingers clutched her ankle, tugged, and she was

falling again.

Desperate, she flung the gun down, smashed it into a furrowed temple. The clutch on her ankle relaxed and she twisted, catlike, found firm footing again, reached and tore the portières aside, darted through them.

To her left was the street door, bolted, but her way to safety. Betty turned to her right, to the stairs, went up them.

They led to a long hall, lighted by a window at the far end to the right. There were four doors, all closed—no, five, counting the transomless one at the end of the hall to the left. This was opening, on a white gleam of bathroom tile and Jen Ralston came out.

She stopped short, eyes widening at sight of the girl. "What—?" she gulped. "How—?"

"Hello," Betty smiled, stepping to the nearest door. "This is the room he said Mary Lanning's in, isn't it?"

"No, that one." The woman pointed. "But—"

"Thanks." Betty cut her off and was turning the knob before Jen's slow mind could comprehend something was radically wrong with the picture. The door wasn't locked, to the girl's immense relief. She pulled it open, went through, pulling it shut behind her.

"Ohh!" A girl not much older than Betty herself jumped up from an armchair near the window, "You—" She was black haired, not pretty but wholesome. Her red-rimmed eyes found Betty and their pupils widened. "They—They did it." Her lips twitched. "I didn't think they'd dare."

This cryptic greeting had Betty speechless for once. Mary Lanning held out her hands, wrists together. "Go ahead. Put them on."

"Put what on?"

"The handcuffs, of course. You always handcuff a murderess, don't you?"

Betty shook her head violently, as if to clear it of cobwebs. "Who's a murderess?"

"I am. I killed him, and that makes me a—" Mary caught herself. "Aren't —aren't you a policewoman?"

"What makes you think—Oh! This uniform. Take another look, Mary. See these letters on my shoulder."

"A.W.V.S." Mary Lanning's voice cracked. "A. W.—Oh, I get it." Her little jaw was stubborn, abruptly, her eyes stubborn. "He's trying to get it out of me another way, is he?" Her tone was shrill-edged with hysteria. "Well, it won't work. I wouldn't tell him, and I won't tell you."

"Wait. Wait a minute." Betty was again bemused. "What are you talking about? What is this you won't tell me?"

"How much of number seven I put into the vats, at the plant. Did you really think you could wheedle it out of me after I refused to tell him, to pay him for hiding me from the police?"

A great light dawned on Betty. "Your job at the Atlas plant was to measure out some chemical to put into what they're making there for the army, something that has to be measured exactly or it's no good, so how much you put in is the one secret that really needs to be kept."

"Yes." The black-haired girl was puzzled now. "Didn't you know that?"

"And they're spies. They've been trying to get it out of you."

"It was him first. Frank Morse. I met him at a dance the Employees' Recreation Club gave and he was nice at first. He was a gentleman. Always remembered I was married and didn't cheat, and he'd just say hello passing me in the halls, or maybe once in awhile treat me to a soda at lunch. There was nothing wrong about that, was there?"

SHE was like a child, asking it, so that Betty's throat ached

for her as she said, "No. Of course not."

"Then that Saturday night he rang my bell, and he said he had something to talk about with me, something important, was inside before I could think to say no. He came in and he said he knew where I could get a lot of money just for telling about number seven, and I told him to stop fooling, that he knew darn well I wouldn't tell it for all the money in the world.

"He kept on at me, and I told him to get out and he wouldn't go." The girl seemed unable to stop. She was talking as if to herself, as if she'd told the story over and over to herself, sitting here alone, so often that it seemed now to her that she was merely doing it once more, forgetting she had a listener. "So I said to him then, that I wasn't going to listen to him and I went into the bedroom. And he followed me in and made a grab at me, and I hit at him and—he must have tripped or something, because he fell down and hit his head on the chair, and he was all over bloody." The black-irised pupils dilated with remembered horror. "He was blood all over him and he lay so still and I didn't know what to do."

"You poor kid."

"I—I was just going to go out and 'phone for a doctor or the police or something when the doorbell rang. It was that Mrs. Ralston, from in front. She said she'd heard me scream. Was something wrong? And then she saw the blood on me, and I had to tell her what had happened."

"Whereupon she told you," Betty put in, "that the best thing for you to do was run away and hide."

"Because no one would believe my story of how a man came to be in my bedroom in the first place. Art wouldn't believe it. He'd think I—that I was—"

"She talked fast, rushed you into packing and skipping out before you had a chance to think straight—"

"She said she had a friend who'd be glad to help me, and her husband had his car downstairs, and—"

"You killed him, damn you!" The interruption, packed with choking rage, came from behind Betty. "You've killed my Jim." She wheeled to it, to Jen Ralston in the doorway, her face livid, Ralston's revolver jutting black-barreled from her shaking fist. "And I'm going to kill you."

"Wait." Betty Marvin stared transfixed at the black barrel, at the black little hole in its end out of which death leered at her, point-blank. "Your Jim isn't dead. He's only—"

"Don't lie to me. I've been downstairs and I saw—get away from that window, you!" The woman was mad with grief and rage. "Get away before I put lead in you too." But the gun was steady now, holding Betty impaled on its threat, "Jim's dead," the woman told Betty, tiny muscles crawling wormlike under her flabby skin, "and you're going to—" A thunderous crash below, cut her off.

Betty started forward, was held by the lifting gun, by Jen Ralston's hating eyes. "Bets!" Ben Marvin shouted, below. "Betty. Where are you?"

"Here! Upstairs here, Ben. Hurry!" but she knew it was no use. "Hurry, Ben." The unexpected shout had relaxed Jen Ralston's trigger finger an instant but it was tightening again. Before Ben could hobble up the long flight—

"Damn your soul to hell," the woman cursed her, and knuckles whitened—A yellow streak flashed to Jen's shoulders, a spitting, yowling feline clawed her. She staggered, struck at it, screaming, and Betty had her hands on the gun, was wresting it away and Ben was there somehow, was pulling Sinbad from the bleeding, gibbering female and a sick darkness welled up into Betty Marvin's brain.

She slid down and down into oblivion.

SHE weltered back to consciousness. She lay outstretched on

the bed and Ben hovered anxiously above her. "Hello." she smiled

wanly. "Hello, hon."

"Hello," he grinned back, the tenseness draining from him, "Feeling better?"

"Lots better." She struggled to sit up. "But how did you get here, Ben?"

"Followed you of course. In Helen Lisbeth. Like I told you I would if that fake slip-up about Mary Lanning's applying yesterday worked out the way I thought it might. If these people knew she couldn't have done that, they'd realize you were—"

"Yes. Yes. You explained all that before. But what I meant was how did you get in this house. The door was bolted."

"Oh! When I saw Mary's face at the window, her mouth open for a scream, and saw her pull back before she got it out, I knew something had gone haywire and I had to get to you fast. So I ran the truck across the sidewalk and battered the door from its hinges. Much quicker than using skeleton keys."

"I'll say it was. And I certainly did need you fast." Betty looked down at the furry bundle curled on the foot of the bed. "You and Sinbad. Ben."

"What?"

"Did I? Did I kill that awful Jim Ralston?"

"Of course not. You only stunned him. He's safely tied up down there, with his wife, if that's what she is, and the master-mind, waiting for the F.B.I. to come and gather them in. You didn't kill Ralston any more than Mary killed that fellow in her bedroom."

"Any more than I—" The black-haired girl snatched at Ben's sleeve. "What do you mean by that, Lieutenant Marvin? I saw him lying there, with blood all over—"

"Not blood, my dear," Ben grinned. "Ketchup, squeezed from a rubber ball as he fell."

"Ketchup?" Mary stared at him as if he'd gone insane. "Did you say ketchup?"

"Precisely. It's still on your floor there, dried up but as red as when it was still wet and looked like blood. That's an old trick, Mary, used by confidence men since the Civil War. It's usually worked on some big shot from a small town, out for a good time in a city where no one knows him. There are a lot of variations, but the classic is getting the sucker in a poker game, staging a fake fight and making him think he's killed someone accidentally, then blackmailing him out of his last dollar. The technique's the same as was used on you. The seeming killing. The supposed friend talking fast and furious, hustling the sucker away before he has a chance to gather his wits, and so on. Only what they wanted to extort from you wasn't money but the secret your employers thought enough of you to trust you with."

He put his arm around Mary's shoulder, looked deep into her eyes. "You've shown yourself worthy of that trust, my girl, but I think you should be prouder of the trust your husband reposed in you."

"Art?"

"Art Lanning. He never doubted you, not for a moment, even when these spies sent him an anonymous letter telling him you'd run off with a lover, to keep him from asking the police to hunt for you." On the bed, Betty's lips formed the word, 'liar,' but her eyes were shinning. "It's a wonderful thing, the faith he has in you."

"Yes," Mary whispered. "It's a wonderful thing." Then she had Ben's hand between both hers. "How can I thank you, Lieutenant Marvin? How can I ever thank you for what you've done for me?"

"I haven't done anything for you," Ben smiled. "Whatever I did, it was to straighten out one of my men, to make him back into the soldier he used to be."

Betty Marvin looked down along the bed into cornflower-blue eyes that blinked at her. "We didn't do anything, Sinbad. We just came along for the ride." And then she jumped up, consternation in her voice. "Oh, my Lord!"

Ben whirled. "What is it, Betty? What's the matter?"

"The Gorgon, Ben. She'll be furious...."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.