RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

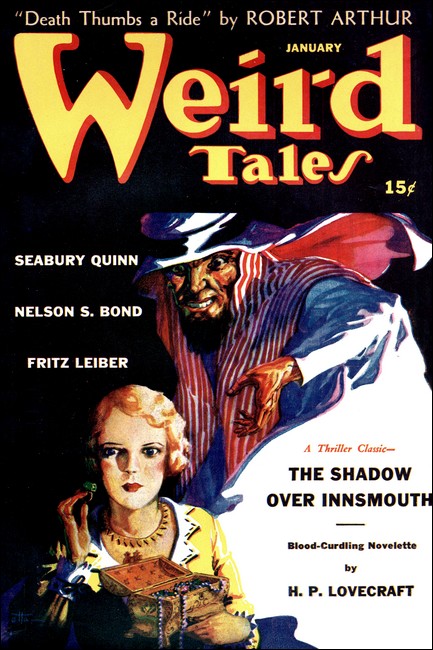

Weird Tales, January 1942, with "Table for Two"

Thought you heard something? Don't be silly. It was

just the sea you heard—just the foam on the ebb tide...

THE table where he sat was at the very edge of the terrace

below which the sea foam whispered, and in the farthest corner

from the leaf-arched entrance. Most of the couples who came here

would accept it only if no other were available, for the music

reached here only faintly, the rustling bulk of an oleander bush

blocked their view of the dancing, and the waiter's eye was hard

to catch.

He smiled, thinking how it was for these very reasons they two had always met here, because in this fragrant shadow they could be alone together—be almost safe from discovery.

So many evenings, this long summer, he had waited here for her as he waited now, that the waiter did not come near him, did not even glance at him. The waiter knew that he would not order until and unless she came, slender and graceful, her face scarf-hidden till she unveiled it for his kiss.

Nights almost beyond counting he had waited here for her, never certain that she had been able to slip away from old Forsythe, who owned her. But tonight was different. Tonight he was certain that she would come. And this was the last night that she would have to come to him furtively, the last night they would have to part secretly, she returning to the great stone house on the hill, he to the lonely shack on the dunes where rusted the typewriter whose clacking had brought her to his open door, that morning so long and long ago.

He had thought her a child when he'd looked up and seen her, sun bright on tumbled, russet hair framing a small face, pert-featured yet somehow wistful, laughter in hazel eyes somehow like sun-glint on the surface of deep, dark waters.

He had not thought her a child long.

Yes, tonight was different, a night for farewells. A muted sadness was in it, in the sough of the tide and the wind-rustle of the bushes. Summer's end. The strains of In the Vienna Woods seemed to come from a far distance. Forms glimpsed through the oleander's dark foliage were dim. The noises of the place; laughter from the tables, crunch of feet on gravel, shuff, shuff of dancing; seemed strangely hushed.

He pulled the edge of his hand across his forehead. Sound, sight, seemed to be fading as the summer was fading. Time itself seemed to be slipping from him. He could not, for instance, quite recall coming to this table beneath which the sea foam whispered, very near now because it was full tide.

No wonder in that. No one could be quite normal after—after what he had done. He could recall that clearly enough. Too clearly. As though it were happening now—

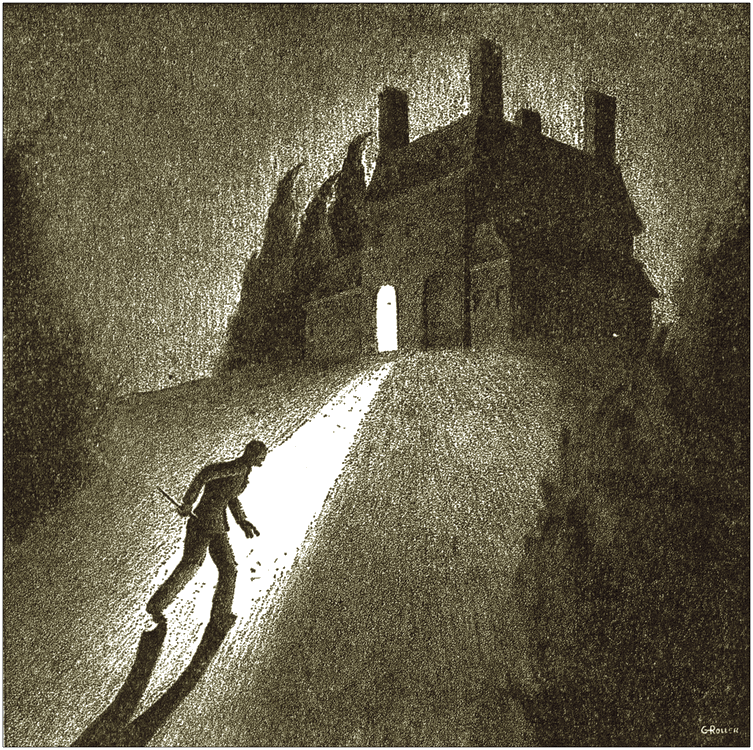

He was creeping, in the early dark, toward the single lighted rectangle that broke the gloom of the great stone house on the hill. His palm was sweaty, gripping the knife he'd kicked up out of the sand. He was afraid, but he was confident too. It all was working out exactly as he had anticipated when she had told him that Forsythe was sending her to the city to prepare for their return, and that she would dine before starting back. That the servants, all but the chauffeur who was to drive her, were to attend a dance in the village.

His palm was sweaty, gripping the knife he'd picked up out of the sand...

Their butler had argued that Forsythe should not remain alone.

Two nights ago someone had been seen prowling about the rear of

the house, last night a cottage on the shore road, and so on. But

the old man irascibly had insisted on having his own way, as he

always did.

Remembering how these matters had made a pattern at the center of which was the salvaged knife, he reached the tall French window that stood open to the lawn and peered around its edge.

Hamlin Forsythe, shrunken and gray-faced and thin-lipped, was sunk deep in an arm-chair too big for the dried-up body, so big that its wing hid all but the narrow shoulders, the hairless head—That head lifted, turned, and gray, hard eyes looked straight at him!

A voice like the rustle of dried leaves. "Don't stand out there. Come in."

He obeyed, hiding the knife behind his back. He halted just inside, barely two feet from the old man.

The latter looked at him with the utterly dispassionate curiosity of a scientist examining an unfamiliar specimen. "So you have come here."

"Yes," he replied, hoarsely, surprised that he could speak at all. "I have come."

"Well," Forsythe sighed. "I am ready for you." The old man's hand came up above the covert of the chair's side and the revolver in it was shining, huge. In the split second before it could fire, his knife flailed for the scrawny throat—

"Darling."

She was slipping into the chair across from him, even that small movement informed with singing grace. "Heart of mine." He had her hands in his, was leaning across the little table to put his lips on hers.

Hands, lips, were icy. "You are cold, my very dear."

"Yes. I am cold." In the dimness he could not see her as clearly as he would have liked, but he could make out that she wore a hat, that her slenderness was still clad in an afternoon suit. "Desperately cold."

"You are exhausted. You came straight here from that long drive. I'll order a drink to warm you."

"No, lover." A swash of water ran along the terrace wall, the turn of the tide. "I may stay only a moment, to say good-by."

"Not good-by, my dear. Not in a moment nor ever again. Let me tell you—"

"There is something I must tell you," her shadow-voice stopped his. "While I was in the city, I spoke to our family physician—No, not for myself. Hamlin had been in to him for an examination, Wednesday, and I wanted to know why he had not received the report of certain laboratory tests.

"He had. Doctor Garter had written him. He had received the letter yesterday morning, and he had not shown it to me because—because what it told him was that he had perhaps six months more to live."

"Six months," he whispered.

"Not possibly any more. I drove right home, without stopping for dinner and so drove into the grounds just as you were stepping in through that window. I jumped from the car and ran to stop you, voiceless, and I was right behind you when he fired. Hamlin saw me. And that is why we must part, forever."

"Part—" He remembered the shot now—

"I am sorry, sir," the headwaiter said, right above her. "But this is the only table I have left."

A boy and girl were with him.

"You fool! Don't you see us?"

Heeding that cry not at all, the man pulled out a chair—

The chair in which she'd been sitting only an instant before.

Sinking into the other chair at the table for two, Bob Cortland looked startled, suddenly. He glanced around, turned back to the girl, his brow corrugated. "Maybe I'm nuts, kid, but I thought I heard someone, right here, whisper, 'Good-by'."

"Silly." Mary Hamlin's laugh was silvery tinkle. "It was just the sea you heard, Bobbie. Just the foam on the ebb tide."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.