RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

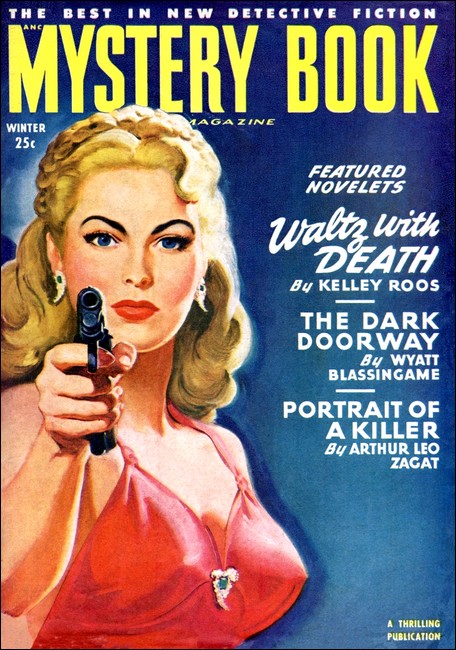

Mystery Book Magazine, Winter 1950, with "Portrait of a Killer"

Beth twisted. The gun-crack was sharp in her ears.

Fred Garlin was surprised to find that

Detectives Rand and Winslow were

luscious cover-girls—but he was due to be amazed by the

deadliness of their kiss!

HE was heavy set, his hatless hair grizzled, and something very like fear glimmered in his gray face. Holding the door open, he peered uncertainly about the office.

It wasn't a very big office. It was just about large enough to hold two varnished pine desks with their swivel chairs and a chair apiece for clients, and an olive-green filing case. Everything was very new and very neat, including the flowered chintz slipcovers on the chairs and the matching drapes at the single big window.

Behind one of the desks sat a girl with hair the color of pale honey and eyes the deep blue of cornflowers. The one behind the other desk was not precisely a girl. She was crowding thirty, the type called "wholesome."

There was no one else.

The man's eyes fumbled back to the lettering on the door's frosted glass half panel:

RAND & WINSLOW

CONFIDENTIAL

INVESTIGATORS

"I guess I've made a mistake," he apologized. "I thought—well, I stepped into the lobby downstairs to get some cigars at the stand and noticed the new name on the directory and I thought it meant you were private detectives."

"That's what it means," the blonde girl smiled. "That's exactly what it does mean. Do come in."

"Thank you, but I can't wait." He looked both disappointed and relieved, like someone who's been told the dentist is busy. "I'll come back some other time when Mr. Rand or Mr. Winslow is in."

"Oh," the blonde girl exclaimed, her eyes rounding. "There isn't any Mr. Rand. Or any Mr. Winslow either. You see, Mr—?"

"Garlin. Fred Garlin. I own the Crown Haberdashery across the street next door to the bank."

"Really!" The way she said it, he might have announced that he was president of the Standard Oil Company. "It's a lovely store, Mr. Garlin. Really lovely."

"Thank you, miss. I must get back to it. I—"

"What my friend was about to explain," the dark one broke in, rising, "is that we are Rand and Winslow." Her voice was deep for a woman's, but somehow warm and pleasant. "She is Beth Rand and I'm Martha Winslow."

"And we're the detectives," the blonde girl added.

UP out of her chair, too, the blonde girl was graceful in a

pale blue sweater that revealed intriguing curves and a gray

skirt that did not reveal nearly enough of shapely legs sheathed

in smoky nylon.

"We thought confidential investigators would look better on the sign," she explained.

"I see," Garlin muttered, edging out. "But I left my clerk alone in the store and he's new and doesn't know the stock. I've got to hurry back."

"You can spare another moment or two," Martha Winslow said, coming toward him. She was squarely built, almost chunky in her decorous black dress, but she was as feminine in her way as Beth Rand. "You came up here because you need help, didn't you?"

"Yes." He couldn't close the door in her face. "Yes, I suppose I did."

"But you've decided not to ask us for it, now that you've discovered we are women." There was the faintest hint of rebuke in her smile. "May I remind you that as a youngster it was your mother you always went to with your troubles, and she always helped you. And now your wife—"

"I have no wife," Garlin broke in. "She passed away ten years ago when Larry—when our son was only twelve." A muscle knotted at the corner of his jaw. "I don't think this would have happened if she were alive."

Martha's eyes widened, but only slightly. "Exactly," she said. "Your mother and your wife were the ones you relied on for help, and they never failed you. They were women, Mr. Garlin. What makes you so sure two other women cannot help—Larry?"

His gray face was startled. "How do you—What makes you think it's Larry—?"

"Who's in trouble? I know it is. When I reminded you of your dead wife, you thought of him, and that he was only twelve when you lost her." There was deep understanding, and compassion, in her tone. "And then you said that if she'd lived this might not have happened." Her hand on his arm urged Garlin toward the chair beside her desk, and he did not resist. "You've been blaming yourself for whatever it is that's happened to him. You've been thinking that she would have done a better job of bringing him up than you have."

"I had to be in the store all day," he said drearily. "Six days a week." Letting Martha press him down into the chair, he sighed. "He would be in bed by the time I got home. I never had a chance to be a real father to him. But he always was a good boy."

"Of course," Beth exclaimed, looking at him from the middle of the floor. "Of course your Larry was a good boy."

"A little wild, perhaps. He used to get into quite a good deal of mischief when he was little, but nothing really bad."

Resuming her own seat behind the desk, Martha murmured, "All small boys worth their salt get into mischief and some of them keep on when they grow up, only then it gets them into trouble." She straightened her desk blotter. "Please close the door, Beth, and lock it so nobody will interrupt us while Mr. Garlin tells us about the trouble his son Larry has got himself into."

The interruption came before the blonde girl could quite get the door shut, but it was only momentary. It took the form of a T-shirted urchin who appeared in the doorway and handed her a folded newspaper.

"Here's your Courier, Miss Rand. It just come an' I brung it right up, the way you said I should."

"Oh thank you, Jimmy," she smiled. "You're sweet to remember." Then she had the door closed and was coming toward Garlin. "Your son's the handsome young man I saw in your store yesterday, isn't he? The one with the curly red hair."

"No. That was Ben Cavell, my new clerk. Larry's hair is black, like his mother's." Watching Beth perch herself on the other end of Martha's desk, the old man sighed. "He wasn't in the store yesterday. I don't know where he is. I haven't seen him or had any word of him since last Wednesday."

"And this is Tuesday," Martha observed placidly. She straightened her desk blotter and asked, "What are you afraid the police might find out about your son if you reported to them that he disappeared almost a week ago?"

Garlin stared at her, his blue-veined hands twisting at the ends of the chair's arms.

"We can't help you," she said, "unless you tell us. You can, you know, rely on us not to betray your confidence."

THE heavy-lidded, tired eyes moved to Beth's face, studied it.

They saw a tip-tilted, saucy nose, velvet lips a little parted,

breathlessly. They saw a blunt and resolute small chin and a

clear, frank look. Fred Garlin sighed again.

"Yes," he said, "I can rely on you. I can tell you."

Larry, he told them, had returned from the Army some months ago unhappy that all his onerous training had wound up only in years of dreary occupation duty. He'd refused to go back to college, had refused to pick up with the old friends he'd lost track of. Taking over as clerk in his father's store, he'd made a trio of new acquaintances who, to the old man's mind, were worse than none at all.

"Walt Durstin," Garlin named them, "Henry Strang and Phil Fator. My best customers, but—well, all through the war they'd be around for weeks and then disappear, and when they showed up again they'd be rotten with money. They told me they were in the merchant marine but all the time ships were being sunk right and left nothing ever happened to them and after V-J day they kept right on the same way and spent even more than before.

"Larry brushed off my warnings. He spent his lunch hours with them and most of his evenings, in the bar of the Continental Hotel where they live, and he talked a lot to me about the adventurous life they led and how he'd like to ship out with them."

"Maybe that's what he did," Beth suggested. "Maybe he did ship out with them without telling you."

Garlin shook his head. "No. They're still around, and when I got hold of them Thursday noon, in the Continental Bar, and asked if they knew why Larry hadn't come home, Durstin told me they hadn't the slightest notion."

"He told something more," Martha Winslow murmured. "I can see it. Something that frightened you."

The fear smoldered in Garlin's eyes. "Yes," he admitted. "Durstin told me that if I knew what was good for Larry, I would go back to my store and keep very quiet about not knowing where he was. It wasn't so much what he said, but the way he looked saying it, that made me afraid."

"Afraid," Martha nodded, "that if you asked the police to hunt for your son, they would discover he was involved in something criminal."

The long, whispering breath Garlin pulled in was assent enough. "And so you want us to try and find him for you."

"Can you?" the tortured question came. "Can you find Larry without bringing the police into it?"

She was silent for a long minute, two pairs of pleading eyes on her. Then, "We'll do our best, Mr. Garlin."

The old man's sigh was one of relief now, and Beth's eyes were two shining blue stars. Martha asked a few questions that elicited nothing more significant than what they'd already heard.

"It would help," she wound up, "if we had a picture of your son."

"The only one taken since he grew up is on my desk in the store. I'll send it up to you." Garlin hesitated. "What—what are your charges, Miss Winslow?"

"Twenty-five dollars a day," Martha smiled. "And expenses."

"And we really ought to have a retainer in advance," Beth added. "Like a lawyer, you know."

"Naturally." The old man dug out of the inside breast pocket of his coat a well-filled wallet. "Will a hundred dollars be all right?"

"Quite." Martha took a card from the desk's long top drawer. "I'll write your receipt on this. It has our phone number on it. Please call us at once if you have any word from Larry or about him."

"I certainly shall," Garlin said, rising.

BETH went with him to the door, shut it and pirouetted across

the floor, her arms flung wide in elation.

"Our first client, Martha! Our very first and it was wonderful the way you made him actually beg us to take his case. Wait till Bill hears about it." She reached the desk and snatched up the newspaper, started flipping pages. "He'll be twice as glad he wrote about us in his column."

"He did what!" Martha exclaimed. "Oh, Beth. How could you?"

"I didn't, Martha. I didn't even know about it till Bill told me last night that it was going to be in the Courier today." The blonde girl flattened pages on the desktop. "Here it is."

It was a double column, mastheaded "THE WAY I SPELL IT" and by-lined, Bill Evans. A small cut was inset of a school slate on which was sketched, white lines on black, a roundish face, spectacled and good humored. But what the firm of Rand & Wilson read was the first three paragraphs of text:

THE WAY I SPELL IT this Tuesday, October 13th, is s-h-a-m-u-s-e-t-t-e. The feminine gender of Shamus—Okay, teacher. Private detective to you.

Our fair city now boasts not one but two of said shamusettes. How come? Well, up to when they were busted to civilians the gals were Corporal Beth Rand and Sergeant Martha Winslow, of the WAC. They'd been attached to Military Intelligence and, meeting again recently, they figured that since they'd once learned how to be pretty fair sleuths, why not make a living out of it now?

They mean business, students, and that's not spelled m-o-n-k-e-y b-u-s-i-n-e-s-s.

"The way I spell Evans," Martha said indignantly, "is a-p-e."

"Bill's trying to help us, Martha." Beth looked as if she were about to cry. "He has faith in us, which is more than you can say of that flat-footed cop you're carrying a torch for."

"Is that so?" the older girl flared. "Dan Teller may not like what we're doing, but you know darn well he'd give us a hand any time we need—Which reminds me. We need him right now." She jerked the phone to her, dialed a number. The burr of the ringing signal cut off and she said, "Lieutenant Teller, please. Detective Lieutenant Dan Teller."

The receiver emitted sundry clickings, rasped harshly. "This is Martha, Dan. I—"

A minor hurricane exploded at the wire's other end.

"I don't like it either," Martha murmured meekly, "but it's in the paper and that's that. Tell me, Dan, what do you know about a Walt Durstin and his pals? We've got a case that involves them, and—"

The tornado blasted again. Subsided. "I see. Look. Why don't you come to dinner tonight and we'll talk it over? ... Good!" Martha cradled the instrument.

"What did he say?" Beth asked eagerly.

"That no girls in their right minds would get mixed up with a trio like that and that if we don't drop the case he'll personally see to it that our licenses are revoked."

"He wouldn't dare!" Beth blazed. "He—" She broke off, her eyes widening. "Would he, Martha?"

"Maybe he would if he could. But he can't." A wistful smile tugged at the corners of the dark girl's mouth. "Still I kind of love the big lug, and he's really in a stew about this."

"That's why you promised to talk it over with him. But you didn't promise him we wouldn't do anything about it till we did."

The smile broke through. "No, Beth. I did not."

Beth's sudden grin was impish. "I'm awful hungry all of a sudden, Martha. And I've heard they serve the most luscious Business Men's Lunch at the Continental Bar. What say we go there, right now?"

"At eleven-thirty! What an unearthly —The Continental!" Martha broke in on herself. "You know, Beth," she chuckled, "every once in a while I suspect that you do have a brain behind those lovely plucked eyebrows of yours. Well, what are we waiting for?"

"For me to fix my face," Beth Rand replied demurely. "My father always said a good mechanic makes sure his tools are in A- one condition when he goes on a job." Going to her desk to collect the requisite paraphernalia, she added, "We'll pick up Larry's picture on the way."

THE Crown Haberdashery was all glass showcases and chromium fixtures. Far back the vista was repeated in a partition that was one vast mirror. Near it a bleached walnut desk was huge enough to furnish lumber for both of those in Rand & Winslow's little office. The desk's leather-backed swivel chair was shoved against the mirror as though its occupant had jumped up to wait on a customer and sent it skidding back.

But no one was in the store—except Martha Winslow and Beth Rand. They came to an uneasy halt where a green crown was inlaid into gray linoleum midway of the floor's length.

"Do you think he went out, Martha?" Beth's voice was very low, barely more than a whisper. "Do you think he went to lunch?"

"Leaving the door unlocked and no one to watch the shop?"

Martha got moving again. Plodding noiselessly toward the rear on her low heeled, stub toed black oxfords, she reached the desk and stopped there. Beth came up beside her, high heels clicking. Martha took hold of the blonde girl's arm with fingers that trembled a bit and with her other hand pointed to the dull black cash register that crouched at one end of the plate glass desktop.

The register's drawer jutted out, open. There was some silver in the change compartments but the longer ones that should hold bills were empty.

"That explains it," Beth whispered. "When Mr. Garlin came back here from our office he found that his new clerk had run off with the money and he was too excited to lock the door when he went to report it to the police."

"Why didn't he phone them?" Martha gestured to the telephone at the desk's other end. "Why did he—?" Her fingers tightened on Beth's arm. "What's that?"

The dull thud came again, from the mirror. Someone was pounding the partition it formed, from behind. Martha went around the desk's end, saw her reflection jump as the mirror was jarred by another thud. She pawed at it and could find no joint. A curious, choked gurgle pulled her around to Beth, rigid just behind her, one sweatered arm angling stiffly out and down toward the desk's dark kneehole.

It was large, that hole. It was large enough easily to contain that which had been crammed into it, and to have concealed it, had not a blue-veined hand slipped into light.

"I kicked it," Beth whispered. "I came around behind you and I kicked—" She took hold of the desk's edge and peered in under. "It's Mr. Garlin, Martha."

The heavy set form was doubled up, sidewise to them, and the gray head was jammed down on bent up knees. Back behind the ear they could see the grizzled hair was darkly blotched by an ooze of fluid that had not yet quite dried.

Beth put her pocketbook down on the floor. She found the wrist of the dangling arm with her fingertips and held them there. The muffled thump thudded twice more against the partition. Beth released the wrist, picked up her pocketbook and straightened, her eyes blue ice in the still, white cameo of her face.

"He's dead." Martha put into toneless words what she read in Beth's face. "You phone the police while I find the clerk. That's who—Oh, I see."

She'd spied the swinging door in the sidewall that obviously was the way to get behind the partition. She reached it and pushed it inward and stepped into a narrow, dim space, a landing from which stairs slanted down on her right to a dark basement.

On her left, however, was a brighter opening and it was through this that the pounding came to her. Turning that way, she found herself in a shallow back-room cluttered with packing cases and piles of cardboard boxes. It was dingily lit by an iron- barred window high up in its rear wall. The wall at this end was the unplaned wood of the partition's back and looking along it Martha saw ankle-lashed legs kick at it.

Copper colored wisps of hair protruded from the plaid wool muffler that was wound around the head and over the eyes of the man who lay on his back and kicked at the partition, his arms twisted under him.

HE stopped kicking as Martha knelt and pulled down over his

chin a necktie, a softly glowing emerald, that held a gag in his

mouth. She dug out the wet wad of silk handkerchiefs and he made

incoherent noises, trying to talk. Tugging at the blindfolding

scarf, she said, "You're Ben Cavell, aren't you? Mr. Garlin's

clerk."

"Yes," he got out. His face was long, narrow, and the eyes that blinked dazedly at her were almost effeminately long-lashed. "What," he gasped, "what did he do to the boss?"

"He?" Martha shoved at him, rolled him on his side, his back to her. "Who?"

"I don't know," Cavell husked as she went to work on the russet tie with which his wrists were bound behind him "I—Mr. Garlin was waiting on a customer and I had my back to him, putting away some gloves that had just come in." The tie was of some rough textured fabric that refused to slip. "First thing I knew anything was wrong was when something hard jabbed my spine and someone said, 'This is a gat, bub. Freeze.' I froze, all right, and then this soft stuff was winding over my eyes. Then hands turned me around and the gun prodded me in back here. The guy didn't say anything. He just gagged me and tied my wrists and shoved me down on the floor and tied my feet."

The clerk's voice was thin, quavering. "I heard him walk away," he continued, "and then I heard the cash register ring. When the front door slammed, I started hitching myself toward the partition here and when I heard the door open again I started kicking at it."

Martha wondered why she had not heard Beth dial the phone, why the blonde girl was not coming back here to her.

"Why did he blindfold you?" she asked. "You'd seen him when he came in, hadn't you?"

"Yes. Yes, I had, I suppose." Cavell sounded uncertain. "But I couldn't tell you what he looked like except that he was kind of short. You know how it is in a store. A customer comes in and if somebody else goes to wait on him, you don't give him a second look, so he's just kind of a blur to you."

"Even if he's someone you know?" Martha persisted. "Even if he's a regular customer, like Mr. Durstin?"

The clerk jerked under her hand. He must have heard, an instant before her, the pound of heavy footfalls behind Martha. She went cold all through as a deep-chested voice growled:

"What the devil put it into your head that I had anything to do with this mess?"

The man who loomed above her was huge, but his was a hugeness of bone and muscle, not fat. His brown hounds-tooth suit was beautifully cut, his tie a swirl of harmonizing burnt umber and his wide brimmed hat a darker shade of brown. The face shadowed by the hat's brim also was brown, the leathery brown to which sun and wind tan skin. It was all broad planes and there was in it a dark and frightening violence.

Her fingers still mechanically working at the knot, Martha fought the terror that clasped her throat, but before she could speak, the menace faded out of Walt Durstin's countenance, was replaced by a taunting smile.

"Just where did you get the strange notion that I had anything to do with this stickup?"

"But I haven't." The knot had yielded and Martha scrambled erect, leaving Cavell to free his ankles himself. "Mr. Garlin once mentioned your name to me as that of a good customer, and I merely used it as an example." And to distract Durstin from the weakness of this excuse, she countered with a question of her own. "How do you know this is a stickup?"

"What else could it be? I come in to look at some gloves Garlin told me he'd be getting in today and nobody's in the store. I see the cash register's been cleaned out and then I hear voices in back here and come in and you're untying Ben." The big man's hands spread in a gesture that indicated it was obvious. "Where, by the way, is Fred Garlin?"

Martha bit her lip, remembering. "He's outside there," she said. "Under his desk. Dead."

"The devil you say!" Durstin heaved around and lunged back the way he'd come and Martha, following, heard the red-haired clerk's feet stumble clumsily after her.

The door to the store's front already was swinging shut on its spring when she got to it, but she batted it open again and saw the big man stooping to peer under the desk.

Saw only him. Beth was nowhere in the shop.

AS Martha reached the desk's nearer end, Durstin straightened

up, let his masked look slide past her to Ben Cavell.

"All right, Ben," he said. "Get that sick calf expression off your phiz and go lock the front door before your lunch hour trade starts barging in on us."

He watched Cavell get started past the gleaming showcases, turned to Martha. "You called this in to the cops yet?"

"I didn't have time." She plucked the phone from its cradle, slashed the dial around.

The ringing signal burred in her ear, cut off and a gruff voice said, "Police Headquarters."

"Lieutenant Teller, please. Tell him Miss Winslow's calling and it's important."

The diaphragm clicked. Durstin was looking at her, silent, his face as still as Beth's had been when she'd announced that Garlin was dead. Martha recalled what had brought her and Beth here in the first place and she let her eyes rove the desk's plate glass top. Between the phone at this end and the open register at the other were only an ebony fountain pen set with an electric clock between the two upslanting pens, a pile of what looked like bills, face down, and a scratch pad with some doodlings on its top sheet.

The angle at which the light from above fell across the glass made distinct its fine powdering of dust, and in the dust, just beyond the pen set, was a line about six inches long where none had gathered.

"For Christmas sake," Dan's voice rumbled in her ear. "What is it this time?"

She swallowed, said, very calmly, "Murder, Dan. I came in here to the Crown Haberdashery about those three ties I asked you about this morning, and I found the proprietor had been murdered."

"The three ties? Why so cagey?"

"In the Graymore Building, near Third and Jefferson. The clerk wasn't hurt, just tied up, and there's another customer here, a Mr. Durstin, so I'm not afraid to wait till you get here."

"I got you! Hold the fort, kid. I'm practically there now."

Martha hung up, fumbled open the bag that hung by a strap from her shoulder. "I—I must look a sight!"

Durstin ripped a sheet from the scratch pad and started tearing it across and across as she dabbed at her cheeks with the lambswool pad from her compact. Cavell stumbled back to them, his pupils dilated. His mouth worked and words spewed from it.

"I could have been killed too. I don't understand why I wasn't."

"You didn't see the holdup man," Durstin said. "Garlin did."

"Yes. He could identify—" The red-thatched head jerked to the muffled wail of a siren.

Through door glass Martha saw a green roadster veer out of traffic. It halted, slantwise to the curb, and two uniformed patrolmen leaped from it.

"Your Lieutenant Teller's radioed a prowl car here," Durstin growled. "Go let them in, Ben."

Cavell started away from them again and the big man started to stuff into the side pocket of his jacket the shreds into which he'd torn the scratch sheet.

"Look at that mob!" he exclaimed. "You'd think they'd popped out of the sidewalk."

The clerk hadn't reached the door yet, but the pavement out there already was black with a shoving crowd and noses flattened, white with compression, against the windows' plate glass. Out of the corner of her eyes Martha saw Durstin pull his hand out of his pocket again, the bits of paper still in it, and throw them into the wastebasket someone had moved out of the desk's kneehole to make room for the corpse.

Ben Cavell opened the door, let in a yammer of excited voices, and the two policemen.

Now Martha Winslow could let herself try to think what Beth could possibly be up to.

AS Beth Rand had started to reach for the telephone a flutter of falling white had caught her eye and she'd glanced down to see what dropped from her pocketbook. Then she was bending to pick up the tiny scrap of stiff paper that had stuck to the bag's turquoise plastic when she'd put it on the floor, freeing her hand to feel for the dead man's pulse.

A rectangle with two cut sides and two torn ones, it was even smaller than the jigsaw puzzle pieces she loved to fit together into a picture. But it was big enough to hold a date, ink-written in Martha Winslow's meticulous small script: 13 Oct W.

Staring at it, Beth became aware that the thuds against the mirrored partition had ceased. She heard Martha's voice through it and a man's voice answering, and knew by their timbre that Martha did not need her. Her narrowed gaze went to the desktop on which a father had said his son's photo stood.

It was not there. That fact became another piece of the design that was forming behind the penciled blonde lines of her eyebrows.

The pieces of this puzzle would not, like colored bits of plywood, wait for her to pick and fit them into a picture. The picture these pieces would make when assembled was the portrait of a murderer and he—they?—would in feverish haste be hiding those pieces that still were missing. Would be destroying them. Larry Garlin was one of the missing pieces. He was the key piece that, above all others, must be put out of reach of those who would try to solve the puzzle.

Martha had told her to call the police, but that would mean interminable questions, delay that well might be fatal. If some customer came in, she'd have to call the police. Even to go back behind the partition and tell Martha what she'd decided would waste critical seconds.

Beth made up her mind. She left the store. She passed the bank next door, and turned the corner. From a tower clock somewhere the first stroke of noon welled through traffic roar, and the office buildings past which she hurried began disgorging their lunch hour crowds.

At the end of the long block the gray granite steps of the old Continental Hotel, still holding its ancient site against the incursion of trade, were clustered with girls and women waiting impatiently for their luncheon companions. Just beyond the steps was the booth-like, decorous street entrance to the Continental Bar.

Narrow, high-ceilinged dimness within held the malty aroma of beer and the spicier tangs of whisky and gin. Only a few men as yet stood at the long and ponderous mahogany bar. Farther back the room widened and there waiters hovered among round tables, for the most part still unoccupied. A short, rotund man came toward Beth, sparse hairs pasted across his pink scalp, the shape of a professional smile painted on his heavy jowled pink face. He met her opposite the far end of the bar, and planted himself in her path.

"Sorry, miss," he said regretfully but firmly. "Ladies are not served here."

Her blue eyes rounded. "But you're wrong. You must be wrong, because Larry told me to meet him here. 'Any time, Beth,' he said. 'Any time you feel like letting me buy you the best lunch you ever ate, you'll find me at the Continental Bar.'"

SHE could feel the eyes of the drinkers on her, knew without

looking what their expressions, their thoughts, were.

"It isn't that I need him to buy me a lunch," her artless prattle continued. "Honestly it isn't. Any time I want a fellow to take me to lunch, or to dinner if it comes to that, there're dozens who'd jump at the chance. Only I haven't heard from Larry for days and days and when I went in his store this morning to buy some handkerchiefs for my boss, old Mr. Garlin told me—"

"Maybe I can help you out, girlie." The man who'd stepped over from the bar was about Beth's own height, hawk nosed, oddly bleak about the thin mouth so that the grin he tried to make winning was anything but that. "I'm a friend of Larry Garlin's."

"Are you?" Beth's tone intimated doubt, intimated that she was not a girl to be picked up by any Tom, Dick or Harry. "Are you really?"

"I can vouch for that, miss," the pink-faced man said. "This gentleman is Mr. Fator. Mr. Phil Fator."

"Oh yes!" She was all genial warmth again. "You're the ship captain or bos'n or something who tells him all those thrilling stories. Larry thinks an awful lot of you and—and Mr. Strang and Mr. Durstin. He really does."

"We think a lot of the kid ourselves," Fator said, grinning.

The pink-faced man said, "Excuse me," in a relieved tone and went toward a group coming in from the street, big men, well- dressed, the "executive type."

"We think Larry's pretty swell," Fator was saying. "He—What did you say your name is?"

"Beth Rand." Her fingers went to his sleeve. "I'm worried about him, Mr. Fator. I really am. On account of what he told me last time I saw him. He told me—"

"Look," he broke in. "Why don't we go to the Washington Room right here in the hotel and talk about it while we have lunch? It's right across the lobby, you know. Right out this door. Come on!"

He was moving toward the side door he'd indicated, his shoulder pressing her toward it, deftly, but they had to pause to let some of the newcomers pass. One of them stopped, grinned broadly.

"Hi, Phil. Long time no see."

"Not since last night," Fator responded, dryly. "You forget quick, Oscar."

"Can you blame me?" Oscar's admiring look was on Beth, but Fator ignored the obvious hint, and the other fell back on a question he quite evidently had no real interest in. "What do you like in the fourth at Jamaica?"

"Flyaway. She's a good mudder and it's raining in New York, according to the Courier." A tiny muscle flicked in Fator's sallow cheek. "Be seeing you, Oscar."

He got Beth to the side door and pushed it open. They crossed the noise and bustle of the crowded lobby.

A bellhop wandered by intoning, "Mr. Ingermann. Call for Mr. Charles Inger-mann."

Fator slowed, said, "I just got a brain wave. Why don't I have lunch sent up to my room and we can talk there without a bunch of nosenheimers butting in. How do you like that?"

Beth made the slowing a complete stop. "I don't," she said. "Not that I'm not sure you'd be a perfect gentleman, but it wouldn't look nice if somebody who knows me saw me going to your room with you."

"There's nobody here knows you. They'd have said hello or waved or something by this time." His hand fell away from her arm and slid into his coat pocket and bunched there. "And your picture wasn't in the Courier. So, ex-Corporal Elizabeth Rand, there's a gimmick in my pocket says you're coming upstairs with me."

BETH'S smile didn't fade. "You wouldn't dare use it here. With

all these people around, you wouldn't stand a chance of

escaping."

"Maybe not." Fator was smiling too, crookedly, and little worms of light were crawling in his black pupils. "But somebody might get hurt if they tried to stop me. That kid with the doll, looking at the souvenirs on the cigar stand over there might get hurt or maybe that cute gal whose guy's brushing fluff out of her coat collar. You never can tell who'll get in the way of lead when it starts spraying around."

Breath whispered out between Beth Rand's red lips. "All right," she sighed. "I came here asking for it, and I guess I've got it. All right, Mr. Phil Fator, I'll go up to your room with you."

Steering Beth into an elevator that had just emptied, Fator snapped to the white haired operator. "Take off, Tom. Fast."

The gate clanged shut and the cage leaped upward with only the three of them in it. Fator's hand—his left, the right still was sunk in his pocket—touched the old man's gnarled one and something green passed between them. Tom leered at Beth, chuckling knowingly.

"You don't have to worry about your old man, darling," Fator said. "Tom here has an awful good forgettery."

The car eased to a stop. Its gate rattled open, clanged shut again, and no one was in the long, door-lined corridor down which they moved. Beth wet her lips with the tip of her tongue.

"You didn't have to bribe Tom to forget your bringing Larry Garlin up here," she said. "He wouldn't remember just another man in a crowd."

"Tom wasn't on—" Fator caught himself, but she'd found out that she'd been right in her guess. "You better skip Larry, sweetheart," he was saying. "You better start worrying about yourself."

"I am. Really I am, but you're worrying about me too, aren't you? About what to do with me. After all, the men in the bar saw me leave there with you and they'll remember."

"That," he murmured, stopping her at a door that had the number 611 on it, "will be taken care of. There are ways. Go on in," he directed. "It ain't locked."

It was a typical hotel suite living room. Heavy maroon drapes hung at the two windows, maroon broadloom on the floor was worn in spots and ponderous armchairs were upholstered in a dark green, hard napped plush. The odor of stale tobacco smoke was explained by the butts overflowing a heavy bronze ash tray on the oval table that centered the room. On a simulated mahogany writing desk against the wall to Beth's left, beside a phone, a newspaper was spread, open to the sports page.

A door in that wall was shut, as was another in the one to her right. The lock of the hall door clacked and Beth came around to Fator. He had his gun out now, a dull black revolver and a little smile of triumph hovered about his thin lips.

"HERE comes the big brass," grunted the policeman who'd stayed just inside the store door.

The one who'd herded Martha Winslow and the two men away from the desk at the rear said, "They sure made a fast run."

The sirens that were wailing outside moaned to silence. The crowd surged, opening a path from the curb. The cop at the door unlocked it and the first man to enter was almost as big as Walt Durstin, but his tweed suit did not ride his frame as neatly as the latter's brown one did, and there was not the same feel of suppressed violence about him.

As the others crowded in after him, he glanced anxiously about the store, saw Martha standing alone near a showcase on the right. He came thudding hard-heeled to her.

"You all right, Marty?"

She answered, equally low-toned. "Quite all right, Dan, but awfully glad you're here," and then her voice was sharp with surprise. "Why, here's Bill Evans! How in the world—?"

"This bozo phoned me practically in the middle of the night," Evans grinned, "to raise Hell about those paragraphs I gave you gals." His chubby frame and round shape made him look even younger than the six years difference between his age and Dan Teller's hard-bitten thirty-three, but there was an expression of ageless worldliness about his brown eyes. "I offered to buy him lunch and spell out for him the meet uses of publicity, and had just gotten to his office to pick him up, when you called. So," he shrugged, "I came along, figuring this thing might make a follow-up in tomorrow's column."

"You put any more about Marty in your column," Dan growled, "and I'll skin you alive." He touched Martha's cheek with the tip of a thick finger. "They want me back there, hon. I'll talk to you soon's as I get the chance."

Her eyes followed him as he strode off to where a little knot of men had clotted behind Garlin's desk. Several were uniformed cops, but she recognized Detective Sergeant Joe Fusco, of Homicide, and the warming realization came to her that this wasn't Dan's bailiwick, which was Gambling and Narcotics. He must have arranged with Lieutenant Moe Abrams to let him take over this call because she was involved in it.

"Where's Beth?" Bill Evans was asking. "Up in the office?"

"No, Bill." Martha looked for Durstin, located him across the store, leaning disinterestedly against another showcase. The red haired clerk beside him was not nearly as calm, not by far. He was chewing on his knuckles, his eyes wide and scared. They weren't near enough to overhear her, though, nor was anyone else as Martha went on, guardedly.

"I'm very much afraid Beth is busy getting herself in a mess."

"That would be nothing new for our Beth."

"No, but this time she's really got me worried. It's this way, Bill. Just before he was killed, Mr. Garlin employed us to hunt for his son Larry, who's disappeared. We came here to get a photo of the boy, a photo his father said was on his desk. It wasn't. It's missing, and I think Beth got the same idea I have, that this means what happened here is tied right in with our case. One of the three men Mr. Garlin thought might have some connection with Larry's disappearance is over there. Walter Durstin. The others are—"

"Henry Strang and Phil Fator." Bill's grin was gone. "I've heard things about that threesome and nothing good. Your guess is that—?"

"Beth's gone over to the Continental Bar, where Mr. Garlin told us they hang out, to try and wangle some information out of them about Larry."

"And that could be not pretty," the chubby chap nodded. "Why not get Dan to chase a couple of dicks over there to pick Beth up?"

"I can't." Martha's teeth caught at her lip. "I'd have to tell Dan why, and that would be breaking a promise we made to a dead man. Beth could hardly have found that threesome yet, Bill." She was reassuring herself more than him. "And even if she has, what could possibly happen to her in a hotel crowded with the lunch hour rush?"

"Nothing much." But his round face was worried. "I'll go get her out of there."

A PHOTO bulb flashed in the rear, and Dan detached himself

from the group, was walking with a plain-clothesman Martha knew

as Harry Lane toward Cavell.

"Oh, Lieutenant," Bill called. "I just remembered I've got to see a man about a trolley car. I'll ring you later and get the lowdown on this."

The policeman opened the door for him and locked it after him and Martha went across to listen to what the clerk would tell Dan.

It was the same story he'd told her. The only thing he added, in answer to a question, was that there hadn't been much in the till.

"We always start with fifty in bills for change, but I don't think we took in more than twenty or twenty-five this morning."

"Making about seventy-five in all," Dan grunted. "Darn little to kill a man for."

"If," Durstin put in, "that is what he was killed for."

Dan glared at him. "Meaning what, mister?"

"Meaning," the big man responded, imperturbably, "that Garlin's son's been missing about a week and for some reason the old man was scared boneless to report it to you."

Martha saw Dan's head jerk to her, saw comprehension come into his florid face, but that didn't matter so much as her shock of surprise that Durstin should bring this into the open.

"Last Thursday," Durstin was saying, "Garlin told me Larry hadn't come home, wanted to know if I had any idea where he was. I told him I didn't and I reminded him that his son was a big boy now and had a right to treat himself to a night out without asking papa's permission. I pointed out that his making a fuss about it would be apt to make trouble between them."

It was, factually, very nearly what the old man had told them, but Durstin had given it a very different flavor.

And he'd beaten Martha to the punch.

"I found out my explanation had been a mistake," he went on, "when I came in here Saturday and Garlin said he hadn't yet heard from the kid. That was different, I said. I said it was high time he got the police on the job, and that was when he let it slip that he was afraid to. I got the idea that someone had got to him in the meantime and put the fear of the devil into him."

In the back of the shop the technicians had finished taking their photos and making their measurements and the uniformed policemen were hauling the corpse out from under the desk so the medical examiner could go to work on it.

"Did Garlin," Dan asked, "say anything to you about hiring a private detective to look for his son?"

Massive shoulders shrugged. "Not to me."

Dan looked at the clerk. "How about to you?"

Cavell's mouth opened, but nothing came out, and his pupils pulsed like those of a woman on the edge of hysteria. Was it delayed reaction, perhaps, from his experience? Durstin seemed to think so. He touched the clerk on the shoulder with a gentleness somehow incongruous.

"Answer the man, Ben," he said. "Tell him the truth. Did Garlin say anything to you about hiring a private eye?"

The youth found his voice. "Yes. He did say something like that when he stepped out, around ten o'clock."

Between them, Martha decided, they'd released her from her promise to the murdered man.

"It was us he hired, Dan," she said. "As you've already guessed. That's how I happened to find the body." She was free now to ask for help. "I was here to get a picture of Larry Garlin that the old man had told us he had on his desk. It wasn't there. I don't see it anywhere, but I've a hunch the killer didn't want us to get it and," she pulled in breath, "and that it's still somewhere in the store. Could you spare someone to look for it?"

DAN was angry. She knew by the way the veins stood out at his

temples that he was very angry, but he merely grunted and turned

to Harry Lane.

"See if you can turn it up."

"It's in a frame," Martha said, recalling the mark in the dust on the desk. "About six inches wide and probably nine inches tall. If I were you, Mr. Lane, I'd look for it on or near the basement stairs."

The plainclothes man nodded and went off.

"I gather, Miss Winslow," Dan rumbled, "that you were the first one in here after the killing."

"That's the way it seemed."

His dark eyebrows arched. "Only seemed?"

"Well I saw no one come out and there was no one in front here when I entered. I'd just noticed that the cash register had been rifled when I heard someone banging on the partition back there. I went back and found Mr. Cavell on the floor, tied and gagged and blindfolded. The first thing I did was to get the gag out of his mouth and he started telling me what had happened. Then Mr. Durstin came up behind me."

"Check," the latter interjected. "I'd come in to look at some gloves Garlin had promised he'd have for me today and like Miss Winslow I was puzzled that no one was out here. Then I heard the voices behind the partition."

The pit of Martha's stomach was fluttering, but she managed to keep her voice steady. "You should have seen someone out in front here, Mr. Durstin. You should have seen my partner, Beth Rand. We came in together and I'd left her at the desk, and there wasn't time enough for you to have come all the way through the store and into the back-room without your at least having met her at the door. You were already in the shop when we came in, weren't you?"

Cringing inwardly from the violence that flared into the big man's face, she went on, a bit breathlessly, "You were in that back room, tying Mr. Cavell up, when you heard the street door open and close. Beth's high heels clicked on the linoleum, but my flat ones didn't make a sound loud enough to carry through the partition and we spoke too low for you to hear us. You thought only one person had come in and darted down those basement stairs, figuring the customer would go back there to Mr. Cavell when he started kicking and that would give you the chance you needed to slip out and get away clear.

"It would have," she continued, "but you heard me mention your name to the clerk, and you had to find out why I suspected you, so you came back there to me instead."

"Pretty," Dan Teller rumbled. "Very pretty, Marty," and Martha knew she was forgiven. He rounded on the glowering Durstin, asked, with mock politeness, "Do you mind if we frisk you for your rod?"

Not waiting for an answer, he nodded to a wiry detective and the latter stepped in, started pawing the big man's body. Dan moved closer to Martha.

"Maybe I was wrong, kid," he said, too low for anyone else to hear. "Maybe you'll make a first class shamus yet," and a glow of gratification at the accolade warmed her.

But it faded as the detective's hands fell away from their search and he reported, "No gun, Lieutenant. He's clean."

Cavell's thin squeal pointed up what that meant. "The killer had a gun. He stuck it in my back. I swear he did."

"Okay," Dan Teller said heavily. "So he ditched it we'll turn it up."

But suddenly Martha knew that they would not.

BETH RAND'S fingers tightened on her bag, but there was no fear in her voice as she said, "You're not going to shoot me, Mr. Fator. You'd be silly to, because somebody would be sure to hear it, and even if they didn't, what would you do with my body? So I don't understand why you brought me up here."

He made his eyes wide. "I told you, didn't I? I told you it's a good place for us to talk."

"About what?"

"About you hunting for Larry Garlin, shamusette."

"He's here, isn't he? In a room behind one of these doors. Which one?"

It didn't work. He didn't glance at either door.

Standing about a yard and a half from her, the gun hanging at his side, he merely said, "Maybe he is. Maybe he's somewhere else. Wherever he is, he don't want his old man to know. He don't want him to know so bad that it's worth a nice piece of change to you and your partner if you'll tell Fred Garlin you've located Larry and he's okay, but he don't want him to know where he is."

This was a piece that didn't fit into the jigsaw pattern. It meant that Fator knew Mr. Garlin had hired them to look for his son, but he didn't know the old man was dead.

"Why, Mr. Fator? Why doesn't Larry want his father to know where he is?"

She didn't expect him to answer that, and he didn't. He said, "Five hundred bucks, sweetheart. Five hundred'll buy you and the sergeant a lot of swell clothes."

"That's what you think," Beth flared, indignantly. "Have you tried to buy any women's clothes lately? Why, this little rag of a sweater, just nothing at all, cost me eighteen eighty- nine."

"Sucker," he observed. "They must have seen you coming." He grinned and went on, "Five hundred still ain't hay, baby. That's all you get. You take it, or else."

Beth giggled.

"What's so funny?" he demanded.

"You. You use all the right words from the gangster movies, and you even look right." She giggled again. "What would you do if I whistled?"

"Maybe you'd like to try?" Whitish pits had bloomed at the wings of his nose and the light worms were squirming again in his eyes. "This ain't a movie," he said, flatly. "This is for real. Here's a couple of things you can whistle about, if you want to. Like you saw, this time of day there ain't anyone in the hall to hear a gun go off, and the rooms both sides of this one belong to us, so no one in them will pay a pop any never mind. There's a trunk inside it'll be easy to fix so that with you stuffed in it, it'll sink fast when we cart it out of here and dump it in the river. As for Tom, for fifty bucks he'll remember, in case anybody should ask him, that he took you down in his elevator, alone."

"You've got it all worked out, haven't you?" Beth still was smiling, but she held her pocketbook in both hands against her, and the fingertips with which she held it were white with pressure. "You really have."

"That's right. I really have. So are you playing along with us, or would you rather stop playing with anybody, ever again?"

Beth managed a shrug. "I haven't much choice, have I? The only thing for me to do is—this!"

Her arms lashed out and hurled the turquoise bag into Fator's face, and in the same instant she leaped toward and past him, but she'd seized his gun-wrist and carried it with her, forced it in now toward his spine as she pivoted to his back, hooked a leg across in front of his shins and levered his arm up.

THE neatly calculated application of momentum and fulcrum

required little strength to throw Fator forward, his feet out

from under him. Beth's two hands, clamped on his wrist, held it

from following, and it was his own falling weight that tore

shoulder ligaments from bone and wrenched a shrill scream from

him.

She let go his wrist and watched him finish his fall, then gaped down in something like awe at his caught-fish floundering.

"I did it," she gasped. "I really did it. They made us practice it and practice it back when I was in the WAC, but I never believed I could do it for real." And then the walls of the room started to drift around her and the floor to slant up, and she had to grope for the back of an armchair and hang desperately on to it.

"Mustn't," she told herself in a little girl voice. "Mustn't faint. Got to go and find Larry. He's in—"

The voice died in her throat as the door in one of the side- walls came open.

"That was a cute stunt," drawled the tall, thin man in shirt sleeves and no tie, who'd opened it. He pushed long fingers through his black hair. "I'll remember not to let you get near enough to use it on me."

Beth swallowed, made the room stop whirling about her. The man in the doorway seemed older than twenty-two, what with the pallid skin drawn tight over a narrow, angular skull, but he did have black hair and he was here.

"Are you Larry Garlin?" she asked him.

His hand dropped from his head and his satiric smile faded. He seemed suddenly wary as he asked, "How'd you figure out I was here?"

"I wasn't sure, but I thought you might be. On account of the picture."

"What picture?"

"The one of you that wasn't on your father's desk in the store." If only Fator would stop moaning, on the floor there between them, she could think more clearly. "Your father told us it was, but it wasn't, and I decided that must mean you were still alive and somewhere we might run into you and recognize you. Otherwise there wasn't any good reason why it should have been taken away by the man who killed your father, and—"

"Killed!" The exclamation was a groan. "The fool!" And then the gaunt shape in the doorway was silent, was motionless except for the hand at its side that closed slowly to a joint-spread fist.

"Ohhh," Beth wailed, repentant. "I'm sorry. I meant to break it to you gently, but it slipped out. I'm dreadfully sorry."

He stared at her, but his eyes were unfocused. Blind. Phil Fator still moaned on the floor there, and the sound seemed a reflection of the bereaved son's agony.

"Who did it, Larry?" Beth asked. "Not Mr. Fator. He obviously didn't know about it. Was it Mr. Durstin or Henry Strang?"

He didn't answer, but his hand writhed open again and a sort of ague ran through his lank body, shivered it into motion. He prowled into the room and bent and picked up the gun Fator had dropped. Straightening, he looked down at the moaning man for a long and terrible moment and then, very deliberately, kicked him in the head.

That stopped the fellow's moans, but it brought one to Beth Rand's throat instead. Just one.

After that, in the room, in the corridor outside the room's locked door, there was no sound.

Beth's throat was tight, so tight that it hurt. She massaged the hurt with icy fingertips and that eased the tightness enough so that she could ask:

"Why? Why did you kick him, Larry?"

HE looked at her and he saw her now. His long arm hung

straight down, the revolver black at the end of it. His tongue

licked lips gone gray.

"You wouldn't have lived long enough to spend the five hundred he was trying to terrorize you into taking." His voice was flat. Dead-sounding. "What he wanted was to get you to walk out of this hotel, alone, so he couldn't be hitched to the bullet in your brain, but he would have followed you, and you wouldn't have got far. You knew that, didn't you?"

"I guessed it was like that," Beth said. "It was plain he wasn't talking for—for you. If you really didn't want your father to have people looking for you, all you'd have had to do was phone him and say so." She glanced at the instrument on the writing table across the room and said, "I could have taken the money and played for a chance to call the police from the lobby, but I was afraid of what he'd do to you in the meantime, knowing I'd traced you here. I'd better call Martha now and tell her I've found you."

She pushed away from the chair to which she'd been clinging all this time and started toward the phone.

"Wait!" The sharp command pulled her around and the gun had jerked up. "We haven't got time for that." The febrile urgency in his voice was frightening. "Strang'll be coming back any second now. We've got to get out of here fast."

He turned to the hall door, twisted back again. "No. We might run into him. There's another way out. In there." His gun gestured to the door he'd come out of. "Quick!"

Beth hesitated an instant, was about to say something, but the gun motioned again and she thought better of it. She went through the door into a narrow passage on which a bathroom opened, faltered at the edge of a bedroom heavy with the odor of sleep and very dim with drawn blinds. A shaded lamp on the headboard of the nearer twin bed spilled a sharp half-cone of light on a propped-up pillow and the garishly colored cover of a detective story magazine that lay open, face down, on the rumpled spread.

Coming from the brightness of the living room, the bed-lamp's light made the other bed seem almost black to her, but she had an impression that its blanket mounded darkly.

Before she could confirm this the voice behind her spoke.

"Go on," it commanded. "Straight ahead," and she was moving again, past the ends of the beds, toward a door directly opposite the end of the passage in which padding footfalls followed her.

SHE reached that door and grasped the knob, was aware that the

footfalls had stopped.

"Open it," the voice ordered. She did. She stared at a rank of men's suits, a bathrobe, neatly hung from a rod that ran across the top of a deep closet.

"Don't turn," the voice behind her ordered, the fever hot in it. "I'm not taking any chances with those judo tricks of yours."

Beth did not turn.

Her hand dropped away from the knob and fumbled to her suddenly constricted midriff.

"I couldn't fool you, could I?" Distorted by stiff lips, her words sounded like a stranger's even to her own ears. "I couldn't trick you into letting me phone for help." The corner of her mouth twitched and she asked, "What are you going to do with me?"

WALT DURSTIN also knew that they would never find a gun that belonged to him at this store. His eyes were laughing at Martha, tauntingly. Then they slid past her, narrowing, and she turned to find out why, and saw Detective Lane approaching. In his gloved hand was a rectangular, flat package wrapped in paper that was smudged with gray dust. "That the picture?" Dan demanded.

"Could be, sir. I found it where Miss Winslow said to look, wedged in between the side-rail of the cellar stairs and the brick wall, halfway down."

"Open it up."

Lane put the package down very carefully on top of the showcase by which they stood. He fished out a penknife, slit the dabs of Scotch tape that sealed the paper folds and used the point of the knife to lift them. Glass glittered in the light. Dan grabbed Ben Cavell by the elbow, dragged him over.

"Is that young Garlin?"

The photo was of a young man in Army uniform, a sergeant's triple chevrons on its sleeve. Shown full length, his stocky frame gave promise of becoming as heavy set as the older Garlin's in middle age, and already the resemblance was unmistakable in the broadly oval, somewhat petulant countenance.

"Well," Dan growled. "Is it?"

"I—I don't know," the clerk stammered. "I never saw him. I only started working here last Saturday."

But Durstin volunteered, "It's Larry all right, and I can tell you how this picture got where it was. I just remembered that as I went through that door my foot hit something on the landing and I heard it skid down the stairs."

"And a gremlin caught it," Dan grated, "and stuffed it in between the side of the stairs and the wall. Well, we'll soon find out who that gremlin was. You don't seem to know it, Mr. Durstin, but we can bring up fingerprints on paper these days as easily as we can develop them on glass."

A muscle knotted in the big man's leathery cheek, but what his comeback would have been Martha was not to know. Just at that instant a gangling, shabbily dressed little man shambled up to the group, wiping his hands with a Kleenex that had been soaked in some pungent antiseptic.

Dan rounded on him, demanded harshly, "Okay, Doc. Let's have it."

The medical examiner peered at him through thick lenses. "Death occurred from forty-five to ninety minutes ago, Lieutenant. The cause was trauma of the cerebral tissues resulting from a compound fracture of the sinistral occipital—"

"Meaning his skull was bashed in," Dan interrupted, "at the back on the left side. By the usual blunt instrument. I suppose."

"With somewhat sharp edges, from the way they lacerated the capilliferous epidermis." The twinkle in the physician's pale eyes was enormously magnified by his glasses. "Cut the scalp, to you. I've given the removal ticket to Sergeant Fusco, so if you've nothing more to ask me—"

"I have," Martha exclaimed. "I have a question to ask you, Doctor, if I may."

He peered at her as if she were some unique entomological specimen. "You may ask, young lady. Whether I shall answer is another matter."

"Naturally. Look there, Doctor." She pointed to a wall- section, a few feet toward the rear, that was built up of long, narrow drawers. "The way the clerk's told it to us, he was putting away some gloves in those drawers and Mr. Garlin was waiting on a customer right behind him. That's what you said, Mr. Cavell, isn't it?"

Cavell's Adam's apple worked up and down in his throat. He nodded, wordlessly.

"There isn't room," Martha went on, "for three men behind that showcase. If the killer had come around behind it, you would have known it, but you told me that the first you knew anything was wrong was when he stuck his gun into your back. If that's so, he must have hit Mr. Garlin from in front of the case. What I'd like to ask you, Doctor, is if you think that with that wide case between them, one man could have struck another at the back of his skull hard enough to fracture it."

"Hmmm." The physician rubbed a meditative thumb along his jaw. "I dare say he could." Martha's heart sank. "That is, if he had an arm about four feet long and fitted with an extra elbow joint. Otherwise no."

"Got it!" Dan grunted. He heaved around to Cavell. "There never was any gun in your back. The two of you worked this kill together and then staged a phony holdup to cover it. With Durstin out of here and you blindfolded, you would both have been in the clear, since you couldn't describe the bandit if you hadn't seen him." He thrust his face almost into the clerk's. "Which one of you was it kept the old man talking while the other slugged him from behind?"

"With what?" It was Durstin who asked that, the taunting smile back that had been on his face when Martha first had peered up into it from her knees. "The way you've got it figured, neither of us ever got out of the shop, so where's the blunt instrument that cracked Garlin's skull?"

"In here somewhere. We'll find it if we have to rip the place to pieces. I—" Dan choked, whirled to Sergeant Fusco, who'd tugged at his sleeve. "What the devil are you butting in on me for? Don't you see I'm busy?"

"Yes, sir," the swarthy detective responded, imperturbed. "But this is something you ought to know, Lieutenant. Right now."

"What is it?"

"Just that we've got what killed the old man, and it ain't what you'd rightly call an instrument at all."

MARTHA saw Durstin's hand go back behind him to the showcase

front, saw his palm rub the glass. "What I mean," Fusco

continued, "is we noticed that one leg of that swivel chair back

there looked a little cleaner than the other three, like it had

been washed. So we looked it over good and underneath the end of

that leg, right where the caster is screwed to it, we found a

speck of blood and a hair stuck to it. A hair, sir, that matches

the stiff's. And the way that leg end's shaped matches the dent

in the skull."

Fusco's face was impassive, his tone respectful, but an evasive something about him was saying, plainly, "This is what happens when an amateur takes charge of a homicide case. If Lieutenant Abrams was here, he wouldn't have made the fool of himself that you have."

Dan understood. His skin went four shades darker with suffused blood and his neck corded. Martha wanted to say something to help him over the bad moment, could think of nothing, but Walt Durstin saved her the trouble.

"Okay," Durstin said. "I was dumb enough to think I could get away with a fast one, but I was wrong. I was in here when Garlin cracked his skull on that chair leg. It wasn't murder. It was an accident."

That pulled Dan around to him, master of the situation once more. "That's where you're wrong, mister. Dead wrong." He grinned, triumphantly. "If you knock a man down and his head hits something, even if you don't mean it to, and he's killed, the law still calls it homicide."

"Agreed." The big man actually appeared to be enjoying this. "But I didn't knock Fred Garlin down. I wasn't anywhere near him when it happened, nor was Ben Cavell. Ben was putting those gloves away, out here, and I'd just come in the door."

"He just slipped, huh. He just committed suicide by banging his head on that chair leg, and you didn't want anybody to know he'd done the Dutch so you staged all this hocus pocus to make it look like murder."

"No." Durstin's smile deepened. "Someone was scuffling with the old man when he fell and was killed, and it's that someone we tried to cover up. But he didn't have any intention of harming Garlin, so—" he spread his hands—"Ben and I may be guilty of obstructing the police investigation of a death, but we're not even accessories to a homicide, because there was no homicide."

"Who," Martha asked, her heart pounding, "who was scuffling with Mr. Garlin when he was killed?"

"His son, Miss Winslow. Larry Garlin. And by this time he's where you and the police put together will have Satan's own time finding him."

"Now we're getting somewhere!" Dan Teller grunted. "All right, Durstin. Since you've decided to stop lying, suppose you tell us exactly what did happen here."

"I'll be delighted to," the big man responded, still amused. "Larry's being missing was on my mind this morning so I decided to come around before lunch and find out if there had been any news of him. As I come in the door who should I see but the youngster himself, back there at the desk squabbling with his father."

Martha wasn't listening to this. She was going back past the showcases with their brightly colored displays, past the long wicker basket into which policemen were putting a body, but Durstin's deep voice followed her.

"I'd got to just about here," he was saying, "when Larry yelled, 'Give it to me, curse it!' I see he's grabbed this package and is trying to pull it away from the old man, but Fred Garlin's hanging onto it and the youngster's pulled him half up out of his chair. The next moment the kid wrenches it loose and his old man flops down, but he kind of misses the chair seat and it goes skidding back and he keeps on down, grabbing at air. Then the desk hides him from me."

BEHIND that same desk Martha upended the wastebasket. Wadded

circulars spilled out of it and crumpled envelopes, and the

ripped halves of a catalogue. And, in a miniature snowfall, some

tiny shreds of paper.

"There's a nasty sounding crunch," she heard Durstin saying, up front. "I get to Larry and his eyes are like two black holes in his chalky face and he yammers at me, 'I couldn't let him give my picture to the police, Walt. I couldn't.'

"I shake some sense into him and he tells me why. He's in a tough jam and has to skip town, and if you cops get hold of his photo, every hick constable in the country will have it, so he'll be sure to be picked up when the thing breaks. Well, I've got no use for you bulls, and I like the youngster, so I tell him to get going. I tell him I'll take care of the old man—neither of us know yet that he's dead, think he's just knocked out—and ditch the photo, and between us we'll cover up for him.

"Larry's broke. That's why he's taken the chance of dropping in here, for getaway money. I scoop out what's in the till and hand it to him, and that's what gives me the idea of faking a stick-up when the kid's gone and I find out I've got a corpse on my hands.

"I pound it into Ben's head that he's in as bad a spot as I am and that if we work it right we can both get out of it. We would have got out too—" Durstin let a note of bitterness come into his tone—"if it hadn't been for that blasted she- shamus and her questions."

"That she-shamus," Martha murmured, returning, "is still asking questions. What she'd like to know now is why you tore into little pieces a certain receipt she herself wrote this morning."

The big man went still, abruptly, his jaw ridging. "What receipt?"

"The one I gave Mr. Garlin for his hundred dollar retainer. On our business card. Why—" Martha pressed him—"did you tear up that card?"

"I don't know what you're talking about."

Martha looked at Dan. "Didn't you say a few minutes ago that you can develop the fingerprints on the paper the photo is wrapped in?"

"Right!"

"Then you can also bring them out on the little pieces of card I just spilled out of the wastebasket back there. If you do, you'll find Mr. Durstin's prints on them, overlaying any others."

She turned back to the latter and resumed, wearily. "Back then when I was calling Lieutenant Teller, it struck me as odd that you should be ripping up a sheet from the scratch pad. That was the act of a neurotic, and you obviously were far from one."

He'd fought so hard and so shrewdly that she was almost sorry for him, but she reminded herself of how a grizzled head had been jammed ruthlessly down on bent knees.

"Just now it came back to me how when the prowl car arrived you'd started to stuff the pieces into your pocket, but pulled your hand out again and threw them into the basket instead, and I decided to go see if you'd thrown something more in with them. You had. The bits of our business card that if they'd been found in your pocket would have given the lie to the story you already were concocting behind that mask of yours."

Martha put her hand on Dan's sleeve and the contact gave her strength to go on. "There was some truth in that story, but very little. Mr. Garlin would have told us if you'd advised him to ask the police to hunt for Larry. You lied about that and you lied about Larry's being in this store today. Larry would have no reason to tear up the card his father was copying our office number from, onto the wrapping of the photo, because he'd have no reason not to want the police to find that card and through it learn from us what the old man had told us. To learn—" she made it clearer—"that even if Fred Garlin's death was an accident it came about as a result of his son's being kidnaped, and so under the law is murder.

"The man who did have that reason was you, Walt Durstin."

Someone exclaimed, "I'll be darned," and someone else, "She's got him."

But it was Dan's voice Martha heard, rumbling, "Good girl." Saying, almost humbly, "You've been a mile ahead of me from the start."

She could not let that pass. "Only because I knew some things you didn't," she said. "You've been leading him on beautifully, Dan, letting him hang himself with his tongue, but you hadn't heard the old man tell us how Mr. Durstin looked last Thursday when he warned him not to report Larry's disappearance to the police."

He must have looked as he did now, his mask crumbling once more to let the terrible violence of him show through.

FROM the corner of her eye Beth Rand saw on the inside surface of the closet door a shadow of a shadow that told her the gun behind her was lifting. Her hands were pressed to her slim waist as though in some way they could stop the shot that would come from behind.

And as though words could stop the man from firing it, she was saying, "You're making a dreadful mistake. The penalty for kidnaping may be only ten years in prison, but for murder it's death."

"I know," the voice behind her agreed, the fever hot in it, "but Walt Durstin's my partner in this thing and he's killed a man." This, then, must be Henry Strang. "In this State, that tags me for the chair too, and so I've got nothing to lose any more, and maybe my life to gain." The sound in the pause that intervened was very like a sigh. "Get into that closet, Elizabeth Rand."

That was why he'd brought her in here. He was taking no chances of his shot's being heard by someone passing through the corridor. The closet would muffle the sound of his gun and afterward he need only shut and lock its door to make of it a vertical coffin, and he would have gained precious minutes for his escape.

Beth bit her lips and stepped into the cubicle. The clothing with which it was filled blinded her, rasped her cheeks, wrapped around her. She twisted.

The gun crack was sharp in her ears.

The look of surprise on Strang's face was almost ludicrous. His gun thudded down and he folded down after it, slowly, as if his joints were melting.

Beth stepped out of the closet, her hand bruising itself on the butt of the small, flat automatic it held. Her pupils dilated, pulsing, she stared down at the huddle on the floor. A dark stain crept from the gash diagonaling across Strang's left temple, but his nostrils fluttered and his breast rose and fell shallowly. She had not killed him. Her snap shot had come within a quarter inch of missing him entirely.

Her mind fumbled back to the pistol range in the Pentagon Building, to Master Sergeant Roberts, who would have bawled her out for so poor a shot. There was a whimper in the room, and it did not come from Strang.

A chill, prickling pucker at the nape of her neck, Beth looked for its source. Her eyes found the bed whose headboard did not hold a lighted lamp, found the black-haired head that lay on its pillow, eyes that were smoot-smudges thumbed into a face pallid as the pillow staring at her.

"Where?" a shadow voice whispered. "Where did the gun come from? You didn't have it when you went into the closet. Where did you get it from?"

"From here." She touched the waistband of her skirt, where the sweater bloused over it. "When you need one, you need it in a hurry, and you can't get it out of a pocketbook in a hurry. So," she said, starting to move toward the bed, "I sewed a little pouch in here for mine and when he made me get in there, I had the chance I'd waited for to pull it out. I've known he wasn't Larry Garlin ever since he kicked Mr. Fator. You are, aren't you? You're Larry."

"Yes," he answered, trying to push up, so feebly that Beth exclaimed, "Don't! You're sick, aren't you?"

"No."

BUT as she reached the head of the bed, the youth sank down

again. "They told the chambermaid I was sick, but I'm not. I'm

just full of dope." A wan smile brushed his colorless lips.

"Which is better than being dead, I guess. Phil wanted to kill me

and slip me out of here in a trunk, but Hen said it was too risky

and Walt said if they doped me and kept me here I'd come in handy

when they finished the job."

"Walt Durstin?"

"None other. He's got a mean temper, but he sure can think up the angles." Durstin, Beth thought, is still left. He may be coming back here any minute. I ought to get Larry out of here quick. But the drug-thickened mumble held her. "This one sure is a beaut. They're going to keep me till they pull the job and then they're going to take me aboard ship with them as a sick Spaniard going home. No one'll blame them if Señor Whoozis gets delirious some night and climbs out a porthole. See? I'll have disappeared, so it'll be me the cops'll look for, and they'll be in the clear."

That's why Durstin took the picture, Beth thought. If the police broadcast it after some big crime, they couldn't get Larry aboard any ship without risking his being recognized.

"They told me I was lucky," he maundered on. "They were going to let me in on their last big job because they needed my help.".

"For what, Larry? What did they need your help for?"

"To let them into the store nights, so the cop on the beat would think I was taking inventory or something. I said I wouldn't have any part of it, and Walt came back with okay, that wouldn't stop them. They knew Dad wouldn't play with them, but any clerk he hired to take my place would be glad to pocket a couple of grand just to cover them a couple of nights while they dug a hole through the cellar wall."

No. Oh, no. It didn't make sense. He was just dreaming it up. "Why ever would they want to dig a hole through your cellar wall?"

"Because—" The youth's lids were drooping. He was sinking back into the narcotic-induced cloud out of which her shot had pulled him. "Because it's —the back wall—of the bank's vault—next door."

His eyes closed. "Larry!" Beth cried in sudden panic. "Wake up, Larry!"

It had no effect. He was dead asleep, but she had to get him out of here. She had to get him out before Durstin came, even if she had to carry him.

She thrust her automatic back into its improvised holster, got her arms around his torso and struggled to lift him. His head came up away from the pillow, his shoulders, and he was very heavy in her arms, but that wasn't what held Beth suddenly motionless, her head turning to where the passage from the living room opened into this room.

A form appeared there, stopped there at the edge of the room and hung, rather than stood, on widespread legs. Phil Fator. Hate flared into his bruise-blotched visage as his agonized eyes laid themselves on Beth. His right arm was dangling useless, but his left crooked up to jab a gun at her.

"Okay, shamusette," he husked. "You're tricky, but you ain't smart. You forgot a guy can come out of a knockout, an' you forgot he can have another rod cached in his bunk." His mouth twisted grotesquely. "Yeh, you're tricky, but you've busted your last arm."

AT that precise instant, back in the Crown Haberdashery,

Martha Wilson was thinking that there was something almost

admirable in the way Walt Durstin seized the black wrath that had

flared into his face and forced it down again beneath the

surface.

"Quite a coincidence, isn't it—" Durstin made a last effort to extricate himself from the trap that had closed on him—"that I happened in here at exactly the right moment to catch Fred Garlin with your card on his desk?"

She shook her head. "It was no coincidence. You'd hurried here to try and bulldoze him into telling the detective he'd hired that he'd heard from Larry and so there was no need to go on with the case. You knew he'd hired a detective because while he was in our office Ben Cavell here had telephoned you what he said when he went out."

She saw Sergeant Fusco move to Cavell, handcuffs glinting. "It was your terrible temper, Mr. Durstin, that betrayed you. It not only sent you into the back-room to me when you heard me mention your name, but it was what made you struggle with Mr. Garlin for the picture and then tear the card into little pieces before you even looked to see what his fall had done to him."