RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

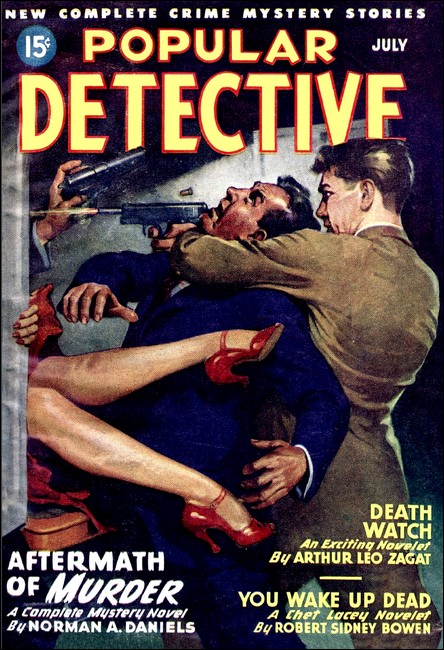

Popular Detective, July 1947, with "Death-Watch"

Straightening up, I swung Garder's automatic to-

ward the man and managed to squeeze the trigger.

Don Lanham and Judith Moore Put Up a Fight

to the Finish to Smash a Murder-Frame Wide Open!

ON a high-school instructor's salary, taxis are a luxury. This afternoon, however, I was in a hurry and hailed one. As a direct result of the time thus saved I was to kill a man and come within a second of dying myself with a bullet in my brain.

The driver had the radio on. It was exquisite torture to my already jumping nerves and so I asked him to silence it. He reached for the dial but before he had time to turn it, a breathless voice said: "We interrupt this program to bring you a special news bulletin."

"Hold it! Let's hear this."

"The body of Rand Harlow," the voice continued, "sixty-three year old bachelor, well known in Southport financial circles, was found at about one-thirty today in a room in the National Hotel, on the outskirts of the city. Mr. Harlow had been strangled. Chief of Detectives Joseph Martin reveals that the killer is known. An early arrest is expected. We return you now to Lola Lee—"

The radio clicked off.

"That 'killer is known' line gives me a swift pain," the cabby growled. "The cops always pull that bluff."

I could have told him it was not a bluff—that barely ten minutes ago the killer had just avoided capture by an escapade that still had me trembling.

Twenty minutes ago, William Moore had stood before me in my just-emptied classroom, long-limbed, lean in plaid flannel shirt and Navy pea-coat, tiny muscles knotting his jaw as he waited for me to speak.

A long slant of sunlight from the open window had struck into brightness on his lapel the gold button that was the symbol of the covert conflict between us. I bitterly envied Moore his right to wear that button, a right that had been denied me by the injury to my knee. He resented my soft years as a civilian, resented me as the personification of the puling discipline which, at twenty, he must share if he were to make up for the years of education he had lost.

Fumbling with some papers on my desk, I wondered if this was to be the crisis of that unacknowledged antagonism.

"I don't understand you, Moore," I said. "I asked you to stay after class so that we might talk over why your work has slumped so badly. Yet you would have walked out with the others just now, if I had not called you back. Do you mind telling me why?"

He merely looked at me, bony face expressionless, somber gray eyes fixed on my face.

In spite of his sullen defiance, there was something boyish about him that tempered my irritation.

"Look," I tried again. "All I want is to help you."

"You can't help me."

It was a desolate, lonely cry that had been wrested from him.

"Why not give me the chance?" I asked, smiling. "I have helped lots worse cases through advanced algebra."

"Algebra! Why, I could lick that stuff without half trying if only—" He broke off, lips tight and stubborn again.

"If only what, Moore?"

HE wasn't listening to me. Head canted, he suddenly was like some wild creature scenting danger. What had alarmed him? Those footfalls in the hall?

Moore whirled, was at the nearest window, and in a single lithe leap, had vaulted to its sill and vanished. Four stories up!

For a ghastly instant I awaited the thud of his body on concrete below, heard instead a thrashing of ivy outside that window. It came to me that he had gone not down but sideways—along the ledge that runs beneath these fourth-floor windows.

The hall door opened. The man who came in was middle-aged, sharp-featured but ordinary in his gray suit. He kept his hat on his head and, after a single quick glance around the room, strode to another door in the wall behind me and jerked it open.

He glimpsed the supply closet's cluttered shelves, turned to me.

"Where is William Moore?"

I resented the fellow's manner. "Obviously not in this room. Class was dismissed some time ago."

"I know. The kids coming out said you were keeping Moore in."

"Most interesting," I observed coldly. "Would you mind very much telling me who you are?"

"Not at all." My sarcasm seemed lost on him. "Name's John Garder." He turned the flap of his coat and uncovered a badge pinned to the cloth beneath. "City Police. Now suppose you tell me how long ago this Moore left here and where did he go."

What had made me answer him as I did? The antagonism his brusqueness had aroused? Instinctive aversion to being an informer, common to most Americans? Most of all, perhaps, the boy's cry for help, still fresh in my ears? Whatever the reason, I had unthinkingly responded with a half truth that had all the effect of a lie.

"I kept him only a minute or two and I did not ask him where he was going. Why? What do you want him for?"

The detective pulled the hall door open, paused, smiled thinly.

"Murder," he said. "The murder of a helpless old man."

The door closed behind him before I had been quite sure I heard him right....

"I FEEL kind of bad." the cabby mumbled. "I've rode this Harlow around town plenty. Nice old guy. Good tipper, but always in a sweat to get where he was going. Every time I'd get stuck in traffic he'd pull out this gold watch he had, half as big as my fist it was, an' tell me how many minutes we was losin'. Wonder how he come to be in that National Hotel. I know the joint. It's a dive way out there near the city dump."

I HAD hobbled to the door and pulled it open, but by that time Garder had reached the staircase and disappeared. Realizing that if I left the room unguarded, Moore could come back through it and escape in the other direction, I snatched up from my desk a brass-bound ruler to use as a weapon, went on to the window and leaned out.

I looked to the right. I saw the ivy that frothed greenly up over the foot-wide stone ledge and streamed up the wall. Only the ivy. Not William Moore.

Horrified, I looked down and down to the gray stone courtyard. Nothing down there either, no sprawled body. But up here, six feet away along the narrow ledge, was another open window. Of course. While I had held up the detective, the youth had clambered along the ledge, climbed in through that window and gotten away. This was now clear. And it was also clear that I. Donald Lanham, mathematics instructor at Southport High School, was accessory after the fact to a murder.

I had violated my oath as a public servant, my duty as a citizen. No one need ever know this, but I could not live with myself until I atoned. But how? What could I do that the police could not do better? Well, there was one thing. The youth's family hardly would cooperate in the hunt for him, but if I went to them as his teacher, ostensibly concerned with the slump in his work and wondering, say, if it were not due to his after-school habits or companions, they might let slip some hint that would set me on his trail.

This I had determined to do. Returning to my desk, I had taken a record card out of the file in the top left-hand drawer, had read the heading:

Name: Moore, William (veteran)

Parent or Guardian: Moore, Judith (sister)

Home Address: 417 Sande Street

Telephone: None (In emergency only, call neighbor, Fair 196)

"Here's your Sande Street, mister," the cab driver once more broke in on my recollections. "What was that number you said?"

"Four-seventeen. I'll get off here."

THE meter read eighty-five cents. I gave him a dollar, climbed out, and started down the block of four-story brick flats, drearily alike as so many fence palings. A pack of urchins played stick-ball in the asphalted gutter, a half-dozen slatternly women tended baby carriages and down at the far corner a man read a newspaper behind the wheel of his parked sedan. Another man, thin, narrow-faced, lounged against the doorpost of Number Four-Seventeen.

He turned and peered at me as, in the vestibule, I found and pressed the pushbutton under the letter-box slit that held the name MOORE. The door-latch clicked and I went through into a dim hallway. Somewhere above I heard a door open. Nerving myself for the role I had to play, I started climbing the carpeted stairs.

One of two doors on the third floor landing was open and a slender girl in brown skirt and frilly white blouse peered expectantly out from it. She seemed much younger than the record card's "parent or guardian" had led me subconsciously to expect.

"Miss Moore?" I asked. "Miss Judith Moore?"

"Yes." Tawny ringlets clustered about her face, the brow broad, the chin firm and capable. "I am Judith Moore. And you are Mr. Donald Lanham, Bill's teacher. He's shown me your picture in the school magazine." She smiled warmly but I had a vague impression that she was not quite glad to see me.

"Do come in."

I went past her into a sun-filled living room whose worn furniture reminded me of my grandfather's parlor. My eye was caught by three framed photographs on the black onyx mantel, one of young Moore in petty-officer's uniform, the others faded portraits of a mustached man and a sweet-faced woman.

"Our father and mother," Judith Moore explained. "They died together in an auto accident when Bill was six and I nine. We were brought up by an aunt but she also passed away, so there's just the two of us now."

Perhaps it was natural for her to tell me all this, but I felt somehow that she was pleading with me. "Won't you sit down, Mr. Lanham? You must be tired after climbing all those stairs."

"Thank you." She has already noticed my infirmity, I thought wryly as I took the high-backed chair she indicated. She seated herself and waited for me to speak.

I fiddled with my Homburg hat. "Your brother's marks have fallen off badly, Miss Moore, after a good start. He seems to have lost interest. I came here in the hope that you might help me find out just what his difficulty is."

The girl's hand pleated a fold in her skirt. "No," she said quietly. "That is not why you came." My hat slipped from startled fingers, fell to the tiles. "Bill is in trouble."

"What—what makes you say that?"

"First there was the man who came here a little while ago, looking for him. I told him Bill was in school. Now you come here. And this morn—" She pulled that back with a little gasp, went on hastily. "Please be honest with me. What has my brother done?"

Murder, I reminded myself. Aloud I said:

"What happened this morning?"

"This morning?" Her lips had paled. "Whatever do you mean?"

"You know precisely what I mean. I caught that slip of the tongue." I rose. "You asked me to be honest with you. Why don't you return the favor?"

Suddenly I detested myself for the part I was playing but I blundered on. "I would like to help you, but I cannot unless you are frank with me."

"I do need help." She ran her hand over her hair. "But—can I trust you, Mr. Lanham?"

"Yes, Judith, you can trust me." I meant it. Heaven help me, in that moment I meant it sincerely. "Tell me what has you so upset."

She hesitated. "It's really a long story and—Oh! There's the downstairs bell." I heard it too, somewhere in the rear of the flat. "It isn't Bill." A frightened question had come into her eyes. "He'd use his key."

The distant ringing came again, longer and more imperative. "I suppose I'd better answer it?"

"Yes," I agreed, regretfully. "You better had." I watched her vanish into a dark doorway at right angles to the entrance from the outer hall. The bell stopped ringing. I remembered my hat, stooped to pick it up from the tiled hearth, steadying myself against the painted iron plate that covered the space under the mantel. And then a most curious thing happened.

The plate grated inward at one side, disturbed by the pressure of my hand. A runnel of powdered mortar sifted out, at the corner, onto the tiles. Abashed, I reached down to scrape it back, felt grit-covered metal, caught a golden glint. On impulse I slipped fingers farther into the aperture and scrabbled the metal object out.

It was a watch, a huge, old-fashioned "hunting case" watch such as my grandfather used to wear on a heavy gold chain across his vest.

Straightening up, I inadvertently pressed the stem and the lid flicked open. Letters were engraved on the polished inner surface.

I stared at the spidery, cursive script, chill prickles scampering along my spine.

ELIHU UNIVERSITY

Trustees' Award for

General Excellence to

RAND HARLOW

Class of 1886

There was a sharp rap on the hall door.

TARTLED, I clicked the watch's lid shut, dropped it in the side pocket of my coat. The rap repeated, sharp, insistent. Where was the girl? Now an impatient hand was rattling its knob. Still no Judith.

It was nonsensical for me to stand goggling at that door. What was I frightened of?

I pulled the door open—took a step backward, throat parching. John Garder came in, smiling thinly.

"Yeah," he purred. "I figured you were the little guy with the game leg Jim Corbin said rang the Moore bell."

"Corbin?" I repeated.

"Our man downstairs." The man who had lounged against the doorpost. I should have known they would not leave this house unwatched. "Just what are you doing here, professor?"

"Not professor. Plain Mr. Lanham. I—I came to have a talk with young Moore's sister about his marks."

"Sure." The detective seemed amused. "You came here to talk about his marks right after I'd told you he's wanted for murder. Or was it to bring his sister a message from him, maybe? Like where he's hiding out."

I licked dry lips. "Moore gave me no message for his sister or anyone else."

I did not expect to be believed, nor was I.

"Look, mister. In this state helping a killer makes you an accomplice. It puts the noose around your neck too." Garder put a friendly hand on my arm. "Don't let him make a sucker out of you. I'm willing to forget what you done so far if you'll tell me where he is."

I gulped. "I don't know."

"Okay!" His bruising fingers tightened on my biceps. "I gave you your chance." His voice chilled. "Now come with me for a little talk with the chief."

And the murdered man's watch was in my pocket!

"Wait!" If I told Garder exactly what had happened in school and why I was here, he might decide he would be wasting his time with me. "Listen."

"Decided to be sensible, eh. Okay. Where's Moore?"

"I haven't the least idea."

"Then anything else you got to say, you'll say it to Chief Martin. We'll take the sister along too. Where is she?"

"Somewhere in back, there. When we heard you ring, she went back there to tick the latch for you."

"Oh, yeah?" The detective's eyes narrowed. "Nobody ticked for me, mister. A fat dame came along and let me in with her key."

No wonder Judith Moore had not appeared. It was she, not her brother, who was using me as a cat's-paw. She had guessed who was ringing and had fled, leaving me to deal with the police.

"Okay," Garder said. "Let's go look. You first, mister, and don't try any funny business."

The long hallway was dim as I hobbled toward the rear of the flat, but not as dark as it had seemed from the living room's brightness. I went past an open door that breathed the powdery perfume of feminine cosmetics, started to pass another.

"Hold it!" Garder snapped. I halted. He was staring into a bedroom, a thoroughly masculine room.

The bed was neatly made, books on a table near the window that held a student lamp were in apple-pie order, but the top drawer of the dresser was pulled half out and one scarlet suspender-strap trailed limply over its edge.

"Looks like somebody was hunting for something in a tearing hurry," Garder muttered. "Okay, get going. Let's see what else."

Ten feet farther on, the passage ended in a wood-paneled dining room. Straight ahead a wide window framed backyard clothes-poles and in the wall to my right a swinging door was tight shut. I started toward it, was halted by the detective.

"Just a minute. Didn't you say you were both in the parlor when I rang?"

"I did. We were."

"How'd you hear a bell in the kitchen from that far away, with this door closed?"

"I can't guess."

"You been telling me plenty that don't make sense." His hand came out from under the flap of his coat and there was an automatic in it; flat, ugly. "If this is a trap, mister, you get the first slug in your backbone. Go on to that door but don't open it till I give you the word."

I REACHED the door and laid my hand on its glass push-plate. The detective shouldered the wall beside me. "Set," he murmured. "Shove." Skin crawling, breath suspended, I pressed inward. The slit widened. I saw a gas-range against the opposite wall, then a sink came into view and an enamel-topped kitchen table in the center of the linoleumed floor. "No one in there."

"Open it all the way. Way back against the wall."

"This is as far as it will go." My scalp tightened. "Something's holding it. Something soft. Alive!"

"Uh-huh," Garder grunted, jabbed his gun at the door. "Come out of there!" he ordered, hoarsely. "Come out or you get a slug right through the wood!"

The only response was a queer, muffled thump on the floor. I looked down.

"Okay," the detective growled, "Here it comes."

"No!" I yelled. "Don't shoot. Look!" I pointed down at the high-heeled shoes visible just beyond the bottom corner of the door.

I went around the door, went down to my knees beside Judith who was propped there against the wall, blindfolded with a dish towel and gagged with another, strips torn from still a third binding her ankles.

"I'll be doggoned," the detective grunted, above me, but I was jerking the blindfold from her eyes, pulling down with trembling fingers the muffling cloth from over her mouth.

"Are you hurt, Judith?" I asked.

She shook her head but winced. Her arms were pulled behind her, obviously bound that way. "You are," I insisted, lifting her away from the wall to get at her wrists.

"I—I don't think so." she said, thickly. "The only place I hurt is the back of my neck where he hit me."

I saw the bruise under the tawny tresses at the base of her skull.

"Who hit you?" Garder demanded.

"I don't know. I didn't see." The girl shuddered. "You're the man who was here before, looking for Bill."

"Right," he acknowledged.

"Mr. Garder is a police detective, Judith," I put in, as I worked at the knot that held her wrists. "Tell him what happened here."

"I'll try to." There was dazed bewilderment in her tone. "It all happened so fast and just a sudden, awful feeling that someone was behind me. Before I could turn this blow fell against the back of my neck and I blanked out."

Her hands came free. She rubbed that angry bruise. "I don't know how much later it was that I came to, all tied up and blindfolded. Right after that I heard someone coming, stealthily. The footsteps went on past me, across the linoleum and then I heard someone whispering, and the door opened again and thumped my side. I held still, scared to death—"

"How long after?" Garder interrupted. "How long after that other guy went through here?"

"Not more than half a minute."

The intruder must have been in the flat all the time we were talking in the living room. He had heard us start down the passage and darted away right ahead of us.

"He had plenty of time to get what he was after," the detective mused. "And he's safe now. Through there." He jerked his head at the open window that framed the iron bars of a fire-escape railing. "The way he came in. Over the roofs from most anywhere in the whole square block." His brooding gaze followed Judith as I helped her to her feet. "We've got a man down in the backyard. We figured the big jumps between the buildings would stop anyone from coming over the roofs, but we forgot they wouldn't be likely to stop a sailor."

"A sailor!" the girl exclaimed. "You mean you think it was—"

"Your brother," Garder finished as she caught herself. "Right. That's why he knocked you out with a rabbit punch that wouldn't hurt you too bad. That's why he hopped you from behind and then blindfolded you, so you wouldn't know it was him. He took a big chance coming here, but he had to. There was something here he had to get."

"Something?"

"Yeah. What do you think it was, Miss Moore?" He seemed to crouch, catlike. "Do you think it was, maybe—a watch?"

It was me who started but he was watching Judith.

"A watch?" She was either a supreme actress or it meant nothing to her. "Oh, I see now. You suspect my brother of stealing someone's watch."

"Not exactly."

"Then what?" she blazed. "Why all these insinuations? It seems to me you should be doing something about catching the thug who attacked me in my own home instead of persecuting me and my brother. I ought to report you to your chief."

"You'll have a chance to do that," John Garder sighed, bolstering his gun. "I'm taking you to him. Let's get going."

THAT was that. The only hope I had left of extricating myself from my predicament was the meager one that I might somehow get rid en route of the thing that tied me and Judith Moore to murder.

"What are you chuckling about," the detective demanded. "What's so funny?"

"Nothing," I replied wryly. "Just a thought that crossed my mind." The ironic meditation that from a single, impulsive lie I had come, in an hour, to thinking like a criminal. But, as my students would have put it, I didn't know the half of it yet.

I waited with Judith on the sidewalk while a few paces away Garder held a whispered conference with the narrow-faced plainclothesman, Corbin. A gray club coupé, distinguishable in no way as a police car, stood at the curb. The scene had not changed. The peddler still watched from his cart at one end of the block and the black sedan still was parked at the other, its driver apparently dozing. He and the peddler also were detectives, I decided.

Corbin nodded. Garder came to us, pulled open the car door.

"Okay, climb in. You first, Mr. Lanham. I want you next to me."

That effectively disposed of my plan to throw the watch over the side when some emergency of driving distracted his attention. He closed the door on Judith, went around to take his own place behind the wheel. We started off.

O ONE spoke. I was too weary to talk. But I did observe, in the rear-view mirror, that the black sedan also was in motion and that it obviously was trailing us. Garder was taking no chances.

I wondered, dully, how he had gotten word to its driver to follow us. It seemed a little odd, too, that the sedan should stay so far behind.

The coupé's jump seat was narrow and I was fairly close against Judith and this was, for some reason, oddly disturbing. We jounced over some car tracks. Her hand slipped from her lap, fell against mine. She did not withdraw it and I discovered that my fingers somehow had closed over it. I am, perhaps, over-conscious of my infirmity. At any rate, this was a new sensation and, I had to admit, a definitely pleasant one.

We turned another corner, into an unpaved road that ran between vacant lots. Far behind, I glimpsed the black sedan. We were running now between a high gray embankment and a flat marsh that extended to the horizon. There was no evidence that any other car ever traveled this lonely road.

My thoughts were as desolate as the landscape. Since Bill, it had come to me, had searched for the watch in his bedroom he did not know it was hidden in the mantel. That must have been done by Judith. Did she know its connection with murder? I did not want to believe that she did. There was no reason why she should. Had she heard that brief news flash?

"Judith," I broke the long silence. "I do not remember seeing a radio anywhere in your flat."

She stared bemusedly at me. "Radio? Oh! We haven't got one. On account of Aunt Emily."

"Aunt Emily?"

"Father's sister, who brought us up. She never had money enough for one but she pretended she couldn't abide them. So even after I started working I didn't buy one. And after she passed away it was wartime and there weren't any decent ones to be had."

"I see." I saw a great deal more than she knew she had shown me. I saw a devoted gentlewoman bringing up her orphaned niece and nephew on a pittance and concealing from them her poverty. I saw the girl realizing the true state of affairs but denying her knowledge lest she hurt the older woman's pathetic pride.

It was a sad, familiar pattern.

"Some idiot's in a devil of a rush," Garder muttered. "Listen to him come!" I suddenly was aware of the sound that reached out to us from behind, the thrum of a speeding car.

I saw the black sedan hurtle into sight around the curve back there. It overtook us, was edging toward us, was crowding us into the ditch. Garder braked. The sedan rocked to a halt an instant later, but the detective already had his automatic out.

"Up!" Garder barked at the sedan's swart-faced driver. "Get 'em up fast."

The fellow's hand went up past his head.

"What's the big idea?" he whined through the open window. "This ain't no stickup. I just wanted to ast yuh was this the way to—"

Something popped flatly as orange-red flame lanced slantingly down through his window. Garder's gun dropped and the detective folded down over his wheel, shuddered and was still.

"Bull's-eye!" the black car's driver observed, lowered a revolver into sight. "How was that fer shootin'?" His teeth showed in a thick-lipped grin. "I had to grab Betsey off the ceilin', where I had her taped."

I was speechless, it was Judith who lashed out at him. "You shot him down like a dog!"

"That's right, sister." The grin left his face and his eyes were diamond-hard as they moved to me. "An' if yuh don't want the same dose, pal, yuh'll toss over that watch. The one in yer pocket."

I stared at him. "How did you know?"

"I know." He shrugged to the rear end of his seat and his gun jabbed at me, ominously. "Yuh gonna give it to me or do I take it off yer corpse?"

"Oh, I'll give it to you and good riddance." I fumbled a hand into my coat pocket. I stiffened.

"It isn't there," I gasped. "It's gone!"

The revolver jerked up.

"Wait!" I croaked. "It dropped out when I got in. I remember hearing something thump. Let me look." I slipped down to the floorboards before the thug could object, pushed head and shoulders beside the front seat below Garder's lifeless body.

"I see it! I've got it!"

"Let's have it then."

THE corpse screened me but, glancing up between a dead leg and a dangling arm, I saw that the killer had leaned out, ready to reach for the watch. I pulled back to my haunches, in the same movement brought up my hand, Garder's automatic clutched in it, and somehow squeezed the trigger.

He was too close, too broad a target for even a tyro to miss. The bullet jolted into his chest, straightened him up. I pumped another, heard it chug into him. Slowly, so slowly my brain had time to photograph for future nightmares the stunned surprise on his face, he slid down below the car window sill.

The automatic dropped from my nerveless hands. A cold shudder ran through me and nausea twisted at my stomach. "I—I had to," came from between my chattering teeth. "I had to k-kill him b-before he killed us. We saw him shoot Garder down like a dog and he dared not let us live to tell about it. You see that, Judith?"

"Yes, Don. I see it." Her voice was suddenly shrill-edged. "I can't bear to look. Let's get out!"

The car door opened and I heard her scramble out.

"Judith!" I squirmed to my feet, was after her as she went around in back of the car and caught her. "Judith."

"Oh, Don!" She was ghastly pale, her eyes great, dark pits. "Don."

Her need calmed me. "It's all over now, Judith." Somehow I had my arm around her, was drawing her to me. "All over." I held her close, as I had never held any woman before. "There's nothing to be afraid of any more."

"Safe," she sighed, her head on my shoulder. As I held her, I was thinking of the implication of what had just happened. The only way the thug could have known I had the watch in my pocket was from her brother. He had heard me in the living room, had watched me find it, slip it into my pocket. He had heard Garder say that he was taking me to Chief Martin, had slipped out and gotten word of this to the man who waited for him in the black sedan.

It was Judith's brother who had sent the killer after us. After her.

She drew gently away from me. "What do we do now, Don?"

"Do? What else but find a phone and report this to the—" I caught back the word "police." What they would find here would look as if Garder had been killed in an attempt to rescue us from him. That would make us, in the eyes of the law, as guilty of his death as the actual slayer. True, the thug was himself dead but the bullets in his body were from the detective's automatic. Garder's first shot might not have been instantly fatal, the sedan's driver might have fired his own gun simultaneously with Garder's second. Difficult to believe but not as incredible as that I had snatched up the detective's automatic as he fell and killed his slayer with it.

The actual story would involve telling them about the demand for the watch and that would implicate Judith in Harlow's murder. Or would it? I must know.

"What is it, Don?" she was asking. "Why are you looking at me so queerly?"

My hand dipped into my pocket. "Look, Judith. This is what that fellow wanted from me." I brought out the ancient timepiece. "Did you ever see it before?"

"Yes." A tiny muscle twitched in her cheek. "Often. When I was a little girl and mother would take me to see Uncle Rand, he would let me play with it."

"Rand Harlow is your uncle?"

"Mother's really. My grand-uncle. I—I haven't seen him since she died."

"But it is not as long as that since you last saw this watch, is it? You are not surprised that I have it. When that thug demanded it from me, you guessed that I had found it where you hid it this morning. Right?"

"Yes." I could barely hear her. "I found it on Bill's dresser this morning. Why did that man want it, Don? Why did he want it desperately enough to kill for it?"

"I cannot imagine. But you know why you hid it. Why did you?"

"I was afraid that Bill—" Her head dropped and her hands twisted.

"That Bill had done what, Judith?"

"I didn't know." She lifted her face. "Please believe me, Don. I didn't know and I don't know now." I did believe her. "Bill is so bitter against Uncle Rand," she went on. "Even as a youngster when he found out how poor Aunt Emily was, what a struggle she was having bringing us up, he hated Uncle Rand because rich as he was, he never gave Aunt Emily any help. When I wrote him that Aunt Emily had died, worn out at last, Bill wrote back that Uncle Rand had killed her. And when I lost my job, last week, he said he was going to—to the old buzzard, he called him, and make him understand that he owed something to his only relatives."

"Did he?"

Judith shook her head. "He tried to, but Uncle Rand wouldn't see him. He was terribly upset over that, and so—so when I found Bill had the watch which Uncle prized, I didn't know what to think, Don. I—I was waiting for him to come home. When that detective came instead, looking for him,—that's when I hid it."

Her hand went out to me. "What's Bill done, Don?"

"I don't know. Judith." This was literally true. "What I do know is that because we haven't been frank with the police, two men are dead, one of them a detective who was only doing his duty. We are going to stop that sort of thing, right now. We are going to make a clean breast of everything and take the consequences if there are to be any."

"Whatever you think best, Don," she agreed meekly.

"All right. The Boulevard is about two miles from here. We can find a telephone there. But we are not going to take this watch with us." I got a clean handkerchief out, wrapped it around the timepiece. "It has caused too much trouble already. Please bury it somewhere in those ashes and mark the place so that you can find it again easily."

"Yes, Don."

She took it from me and went off. I returned to the cars and made sure that both men really were beyond help. That was why I had asked Judith to hide the watch instead of doing it myself, to spare her the distress of watching me fumble with their bodies.

I am no physician but I did not need to be one to know that there was no life left in either.

UDITH rejoined me and we started off. Her arm in mine, we went along the meandering road. For a long time neither of us spoke, not, in fact, till we had neared the Boulevard. "Don, you said before that we haven't been frank with the police," Judith said. "That means you too."

"Yes, it does." I had to tell her then about the incident in my classroom and so, inevitably, about the news flash. She took it better than I expected, just tightening her hold on my arm.

"Bill did not kill Uncle Rand," she said, very quietly.

"I certainly hope not."

"I'm sure of it, Don. Not only because I know my brother could not do a thing like that, even in anger, but because it stands to reason that he wouldn't have left uncle's watch lying around for anyone to find."

"But he did sneak back for it, didn't he? Perhaps—Oh!" I broke off. "That's why Garder was driving us this way. I wondered."

The curve around which we had been plodding ended at the edge of the Boulevard and there, directly across the wide highway, was a three-storied, drab structure with a gabled roof and a sagging porch. Weatherbeaten lettering proclaimed that it was the Atlantic Hotel!

There was a parking lot beside it, but no other building as far as I could see in either direction. We went up on the porch and through open double doors into the rancid aroma of stale beer. A few disconsolate club-chairs and a long wooden settee stood around on the bare gray floor of the lobby.

A wide staircase rose along the left hand wall and a dirt-streaked pendulum clock on a pillar said it was eleven minutes to five. Under the slant of the stairs was a battered counter from behind which the only occupant of the room, a stoop-shouldered small man in a gray alpaca office coat, peered questioningly at us.

I wondered, as we went across to that counter, what Rand Harlow could possibly have been doing in this "dive," as the cab driver so aptly had described it.

"No room," the clerk said before I could say anything. "We're full up."

"We do not wish a room," I told him. "We would like to speak with Mr. Martin, the detective in charge of investigating the death of Rand Harlow. Kindly tell him that Miss Moore and Mr. Lanham have some important information for him."

"Oh." The idea penetrated. "About the killing?"

"Precisely."

He licked wet lips. "Mr. Jones!" he called.

"Okay, Jenkins." A second man appeared through an open door in the partition behind him. "I heard." He was tall, wiry, his hard-muscled face the same still mask that Garder and Corbin had worn. Cold eyes examined me, flicked to Judith, came back to me. "Step in here please and I'll go call the chief."

I moved aside to let Judith precede me, followed her into a small room. The door clicked shut behind us. Judith stopped short. She looked around.

"Don!" she whispered. "This place scares me."

"Scares you?" A heavy desk against the inn's rear wall was of polished mahogany and its top held a blotter pad with corners of pink onyx, an ash tray and combination fountain-pen holder and clock of the same finely grained stone. Light from a fluorescent fixture in the ceiling glowed softly on low, deep-seated arm chairs upholstered in red leather, as was a couch against the inner wall, and maroon broadloom covered the floor. "It is certainly amazingly luxurious, especially by contrast with that down-at-heels lobby, but—uh-huh! I see what you mean."

Except for the door behind us and another opposite, the walls were unbroken.

"There's no window." Judith breathed, white-lipped. "It's like a cell. I—I feel stifled, Don." She twisted, snatched at the doorknob, turned it—stiffened.

"Locked," I said for her. "Jones locked it!" But she had darted across to the other door so fast that by the time I had hobbled to her she already had tried it and was turning to face me, her back against it.

"You didn't expect that detective to leave us unguarded?" I managed to say nonchalantly.

"What's that, Don?" She pointed to a three-inch square of blue paper on the floor beside the desk. Judith snatched it up, glanced at it. I heard her gasp. Then she held it out to me. "Look!"

A long number was stamped at the top of the bit of paper, in red. Beneath this was printed,

SOUTHPORT CLEANERS & DYERS—

STORE NUMBER THREE.

On dotted lines still farther down were scrawled in pencil:

"Dress—No belt," and "75c" and "Moore—417 Sande."

"It's for the dress I asked Bill to leave at the cleaners on his way to school," Judith said. "He was here, in this room, some time this afternoon."

"Less than half an hour ago," said a soft, lisping voice. "It was rather—untidy—of us not to notice that slip drop from his pocket when we searched him."

JONES shut the door from the lobby as soundlessly as it had opened. But it was not he who had spoken. The fat man who had, and who now padded toward us would have been dubbed by my irreverent students, "Mr. Five-By-Five." He appeared almost as broad as he was tall, which was about up to my shoulder. His enormous pink visage had two tiny blue eyes, a miniature nose and a small, rosebud mouth.

"Please make yourself comfortable. Miss Moore." He waved an amorphous hand at one of the red leather chairs, "and Mr.—Dr—"

"Lanham," Jones said.

"Ah, yes. Mr. Lanham. Will you sit down?"

Neither of us moved.

"No? Well, you will pardon me if I do. I had a rather trying day."

The fat man turned the desk's matching swivel chair to face us, wedged himself into it. Jones came over to me. His hands spread, thrust under my armpits, ran down my sides, slapped my pockets. It was done so unexpectedly, so deftly, that before I quite realized I was being searched, he was grunting, "Not on him, chief. He's clean."

He started toward Judith. My hands fisted, I moved to stop him.

"No, George!" the fat man said. "There's no need of that, I am sure." He tented pudgy fingers, gazed benignly at her. "Miss Moore will give me her uncle's watch without that."

"I haven't got it, Mr. Martin. I hid it!" Judith pulled in breath, her pupils dilating. "He'd have no reason to think either of us had that watch, and he wouldn't ask for it first thing. You're not Mr. Martin. You're not—either of you—police. Who are you?"

The fat man drooped lids over those china-blue eyes of his.

"My name is Barker, Miss Moore. Stanley Barker." He seemed more amused than taken aback. "Chief of Detectives Martin and his cohorts finished their business here at about four and left, taking with them the late, unlamented Rand Harlow in a wicker basket."

"There are no police in this hotel to interfere with our little tête-à-tête." He smiled blandly. "And so, my dear, you would be very wise to give me your uncle's watch without any further argument."

"I tell you I haven't—Bill!" Judith's hand went up appealingly. "It's after five now and you said he was here only a half-hour ago. Where is he?"

"Safe. Whether he remains so rests with you. Unless you tell me where that watch is, I shall turn your brother over to be tried and hanged for murder."

Her face hardened, was as impassive as her brother's had been, standing before my desk.

"Mr. Barker," she said, tonelessly. "Bill did not kill Uncle Rand."

"Perhaps not." Barker shrugged. "But the police believe that he did. A young man was seen to enter Harlow's room last night. Sounds of a quarrel were heard. The young man left hurriedly. The management became alarmed about noon today and entered with a master key to find him fully dressed, strangled to death. When the police searched that room, they found there a high school algebra textbook with your brother's name and address on its fly leaf, and in the dead man's wallet they found a threatening letter, signed, 'Your unloving grandnephew, William Moore.'"

"Threatening?"

The fat-drowned eyes veiled themselves again. "Let me see. I think I can recall a significant passage. Ah yes.

"'This is the last time I am asking you politely to see me and talk this over. If you give me the brush-off again—remember I've just come back from a place where guys know how to be really tough.' That's the case against your brother, Miss Moore."

"A flimsy case that can be upset by just one person who saw Uncle Rand alive after Bill left. One of the other hotel guests, for instance."

"Quite so. But beside Rand Harlow, the only other guests last night were Mr. Jones and myself." Why then had the clerk told me the place was full? "Besides us and your brother, the only persons in the house were Jenkins and the porter who also acts as bellboy and chambermaid. We have all made statements to the police and we all are prepared to identify William Moore as the young man who was here last night."

Barker paused, smiled. "Your brother will hang, my dear, if he is caught. I can save him from being caught. My price is Harlow's watch. It seems very little to pay for a young man's life."

Judith was haggard. "Yes," she agreed. "Very little. But still too much to pay for a life spent hiding from the law, a life of exile and eternal fear. I don't believe Bill is a murderer. I won't tell you where that watch is hidden."

"I think you will." The enormous body heaved, was up out of the chair. "There is no one to interfere in this hotel." He moved ponderously toward Judith as, eyes wide now with terror, she backed from him. "I intend to have that watch, Miss Moore." The wall stopped her. "Where is it?"

SHE slid along the wall and Barker prowled after her, a tiny bubble of spittle at the corner of his rosebud mouth. She reached a corner of the wall, and was penned in it. His huge arms came up to reach for her.

Somehow I was there, left hand seizing a monstrous shoulder, my right fist for his pink expanse of cheek.

The blow fell short because an iron arm, suddenly across my throat from behind, had jerked me backward. Fingers clamped my left wrist, forced my hand down and up again behind my back. Strengthless in Jones' chancery, half-throttled. I saw that I had pulled the fat man momentarily off balance. In that instant Judith had slipped by him, was darting across the room.

She reached the desk, snatched something from it, whirled and hurled it. The onyx clock ploughed into Barker's paunch with a sickening chunk. He doubled up, eyes glazed, and kept on going down, to land, a grotesque, still heap, on the floor.

Jones thrust me from him. Gasping for breath, fighting for balance, I heard:

"Okay, you witch," he growled. "Now you get what's coming to you."

I got feet under me in time to see his gun appear and arc up, to pointblank aim at Judith. I grabbed the weapon in both hands, forced it down, held it.

Blows pounded my skull, pounded darkness into it. The revolver was wrested from my grip and despair followed me down, down into oblivion.

CAME up out of nothingness, through weltering dark, to awareness of pain, to recollection of dread and terror, violence and despair. A sob came from the pale blur that hovered over me, that cleared and became—Judith's face!

She knelt beside me on the heaving floor and just beyond her lay Jones, prostrate, motionless.

"Judith," I said. "You all right? He didn't—"

"Shoot me? No. You kept him busy long enough for me to pick up the clock again, run around behind him and stun him. Stand up, Don." Her arm slid under my shoulders, tried to lift me. "We must get out of here before they come to."

Somehow, with her help, I was on my feet, my head spinning. I stumbled beside her toward a black oblong in the wall beyond the still mound, Barker, who was breathing stertorously, his eyelids beginning to quiver. That rectangle was the door opposite to that by which we had entered, and it was open.

"How?"

Judith understood. "Barker's keys. I searched his pockets for them." She shuddered. "I was afraid to try the lobby. That clerk is out there, and maybe others."

We went through on to hollow-sounding wood and I was feeling much stronger by now. A brick wall was straight ahead and wooden steps went down from the landing to the left. The light faded and shadow swallowed us as Judith shoved the door shut. I heard keys clink and the thud of a bolt shot home.

"Locked," she whispered, somewhere in the dark. "Let's go."

"Careful." My fingertips found a handrail. "Where are you?" My other hand reached out, found her cold fingers.

"Come on." My foot found the landing's edge and we started down, step by groping step. "I hope this isn't the only way out of the cellar."

"It can't be. It mustn't—" Judith's hand tightened on mine, pulled me to a stop. "Listen," she breathed.

I strained to hear. Nothing—Yes! Somewhere in the tar-barrel murk below there was a sound. A muffled thump, oddly familiar. It came again. Where had I heard exactly that sound before? Again. I remembered.

"That's the way your tied feet sounded behind the kitchen door. Someone is tied up down there, as you were."

"Someone? Bill!" Her hand jerked from mine and she was gone. "Look out!" I called, as loudly as I dared, but the only response was her heel-clicks on wood, then on stone or concrete. I heard her thud into something, whimper. I heard her call, low-voiced, cautious:

"Bill. Where are you, Bill?"

The thumps came faster. I stepped off the last tread onto the hardness of concrete, hesitated.

"Bill. It's Judith, Bill." I couldn't tell where in this blind nothingness her voice came from. "Where are you. Bill?"

If I only had a flashlight or matches, even! But I do not smoke. Was there a switch down here at the bottom of the stairs? My fingers found the wall, trailed harsh brick, touched corrugated metal, followed the cable to a small metal cylinder, a tiny lever projecting from it.

I thumbed the lever. Click!

Grimy light spilled down from a bulb overhead, and from other bulbs further on. I blinked at what they revealed. No wonder sound was muffled here. Instead of cavernous space I saw wooden cases piled up to a beamed, low ceiling, case after case in long tiers that left an aisle along the nearer wall, other aisles opening into it.

From some far distance a siren wailed, muted. A motorcycle policeman trailing some speeder on the Boulevard, I thought. If only I could get our cry for help out to him.

"Don!" I heard Judith exclaim from somewhere nearby. "I've found Bill. Here he is."

"Quiet!" I warned, hobbling down the transverse corridor. "Want them to hear us?" I saw her kneeling at the end of a side passage, beside a recumbent form, bound and gagged as she had been. Bill's gray eyes widened with surprise as I came up and his excited sister got his gag loose.

"Knife." he sputtered. "In my pants pocket." Then: "How the devil did you two find me?"

"We'll talk later!" I snapped. "Our business now is to get away before those two thugs up there recover consciousness. Find that knife and cut your brother's lashings, Judith, while I hunt for an exit."

I hastened back to the aisle along the wall, turned in what I estimated was the direction of the building's rear. An end case in one of the tiers I passed was broken open to reveal long, flat packages wrapped in salmon paper. Bolts of cloth! Cloth, hundreds of cases of it in the basement of a lonely inn far out on the outskirts of the city. Why?

And I remembered, answering myself, a newspaper headline read—yesterday? Last Sunday? Whenever I had read it, I could see it clearly:

CITY CENTER OF TEXTILE BLACK MARKET

Huge Profits Bring Back Prohibition Lawlessness,

OPA Enforcement Agent Warns

I went past the last pile of cases and there, right ahead of me, black against the gray cellar masonry, was the door I hunted, an iron door fitted closely in an iron frame. But the elation that had flared up in me died away. Fastening that door to its frame was a thick-shanked, heavy padlock.

Of course. There was a fortune in cloth here, at black market prices. It had to be protected against theft.

THE key to that padlock would not be among those Judith had taken from Barker. It had no key. It had only a combination dial.

Above me, in the hotel lobby, there was a sudden trampling of feet. Barker and Jones had revived. They were getting help to make sure of overwhelming us when they came down here. They could take their time. We were trapped.

Judith and her brother joined me. I gestured at the door and its lock, unable to speak.

"Yeah," Bill Moore grinned. "I saw them lock it when they brought me in through here." The sullen brooding was gone. He was more alive, more vibrant than I had ever known him to be. "Okay. Let's get busy."

"Busy? Doing what?"

"Fixing a fort out of these boxes. They're as good as sandbags any day." He was back at the nearest tier, shoulder braced against the top one of the three huge cases that piled atop one another forming its vertical end row. "Come on, give a hand shoving this stack around!"

I saw what he had in mind. Doing this would form a barricade behind which we would be safe for a while at least.

"Hurry up! We haven't got all night, you know."

Judith and I added our small strength to his. It was enough. The stack grated around, heave by heave, till he panted.

"Avast!" he panted, at last. "We've got to leave ourselves room to squeeze in."

Except for the narrow slit between wood and stone through which we had done this, we now were surrounded on two sides by the foundation walls in one of which was the door, on the other two by three-foot thick, bolt-filled cases that would stop anything less than artillery.

"If we only had a gun," I said wistfully.

"We have, Don." Judith held a revolver up to my startled gaze. "Jones's. I stuck it in my skirt pocket while I was trying to get you to come to."

"Good for you, sis!" Bill took it from her. "They can come now. We're all set."

Set for how long. I asked myself drearily. We had only one gun, six cartridges at the most, against many ruthless killers. There were no neighbors to hear the shots and interfere. We were set—Yes! Set for death.

"I don't hear anything," Judith whispered from where she peered out over her brother's shoulder. "I don't hear them." Neither did I. There no longer were any thuds on the ceiling, any sound of movement anywhere. "Why don't they come?" the girl quavered. "What are they up to?"

"Easy, sis." Moore reached back, patted his sister on the shoulder. "Easy does it. They're playing the same game the Japs used to, laying quiet till we get good and jittery. Then they'll come at us screaming. The way to beat that game is to keep your mind on something else." His cool, confident tone eased me somewhat. "How did you two ever get here together? Did you go to school looking for me, Judy?"

"No, Bill. Mr. Lanham came to the flat."

"That was after that incident in the classroom, Moore," I explained.

"Oh, yeah. That reminds me, Mr. Lanham. I ought to thank you for covering me up the way you did, even if it did get me in a jam."

"Got you in a jam," I snorted. "How do you make that out?"

"Why, after I heard you tell that dick I'd scrammed, I couldn't show you up as a liar by coming back in, could I? The reason I forgot you'd asked me to stay after class was because I'd made up my mind to go to the cops and tell 'em everything that happened here last night."

Judith's eyes sought mine, appalled. "He did kill the old man after all!" they seemed to say.

"Who I thought it was I heard in the hall," her brother was saying, "was one of Uncle Rand's goons. I'd spotted him hanging around outside the school lunch hour. I ducked him, but I was scared plenty.

"Well, after I heard you pull that phony on the dick, I slid out through the next room and beat it downstairs figuring I'd wait outside for him. I get out on the sidewalk and who steps up alongside of me but this Jones again. He's got a gun in his pocket which he jams against my side and marches me into this black sedan that's standing at the curb.

"The guy behind the wheel starts it moving as soon as we're in, and Jones bats me across the mouth with the back of his hand when I start asking him what the big idea was. We come out here, not by the Boulevard but by some other road and they take me through some bushes out back and in through this cellar and upstairs to that office there. This fat buzzard, Barker, is in there.

"'Your uncle wants his watch back,' he says."

Bill's face was grim as he continued:

"'I haven't got it,' I tell him. 'I left it on the dresser in my room at home.' 'Search him,' Barker says. They go through me but of course they find nothing. 'Okay,' Barker says. 'Tie him down in the cellar while you two go and find out if he's telling the truth.'

"When I try to protest, all that brings me is another crack in the puss."

"You didn't know!" Judith broke in, suddenly radiant. "You didn't do it!"

He jerked around at that, stared at her. "Didn't do what?"

"Kill Uncle Rand. He was found dead in a room upstairs. Murdered."

"Murdered!" Bill looked stunned. "Why, he was all right when I left him last night. Is that what that dick wanted me for? As a witness?"

"Not exactly," I put in, forestalling his sister. I was not as sure as she that he was wholly innocent. "You did see Harlow last night, obviously, here. How did you come here, of all places, to see him?"

Moore didn't answer that.

"We're forgetting about watching for those goons," he muttered, staring through his lookout slit. I waited for him to go on but he remained silent, half-crouched, the knuckles of his fist white with its pressure on the gun butt.

For a long minute we hung there, listening tensely. The hush somehow was more ominous, more sinister, than any imminent threat of attack could have been.

"I remember," Judith exclaimed. "That call for you on Mrs. Perskin's phone last night. You wouldn't tell me who it was from, Bill. You just grabbed up your pea-coat and went out. It was Uncle Rand, wasn't it, telling you to meet him here?"

"Sure," her brother grunted. But he did not go on.

Judith touched his shoulder. "Look, Bill," she said gently. "I've told Don about Aunt Emily and everything. He's our friend. You can talk to him as you would to me."

"Okay, if you say so, sis. I'll spill it all."

Harlow, he went on, had said over the phone that he had been thinking matters over and had decided that blood was after all thicker than water. If Bill would come to him at the Atlantic Hotel, he might have an interesting proposition for his nephew. No one must know about this though, not even Judith.

Arriving here, young Moore had been ushered into the strangely luxurious office and had been surprised to find there not only his grand-uncle but three others; Barker, Jones and another man named Halsey who from his description apparently was the driver of the black sedan, the man I had killed.

"The layout didn't look right to me." Bill observed. "I remembered what Aunt Emily once told us about Uncle Rand having made his money out of bootlegging in the old prohibition days, so I wasn't surprised at what his proposition turned out to be."

It was that the young man should join the gang in their black market operations. "I thought of how my buddies are being rooked for their civvies so these buzzards could cash in and I got kind of sick to my stomach. I didn't sound off though. I was scared, mighty scared! Nobody knew I was there and they'd told me plenty more than was healthy for me to know, so all I said was I'd like a chance to think it over."

Breath whistled from between his teeth. "Sure felt good when Uncle Rand said all right, I could let him know tomorrow night—today, that is. I get another scare though, when he calls me back.

"'Just a minute, young man,' he says. 'Whether or not you decide to come in with me I want you to have something that will remind you that time is money.' He unhooks this watch from his vest chain and hands it to me. Then he says something else queer: 'But there is one adage you might do well to ignore. The one that says never look a gift horse in the mouth.'

"I don't stop to ask him what he means," the youth ended. "I just get away as fast as I can. I'm so jittery I don't even wait outside for the bus but start walking down the Boulevard towards town. When it comes along. I get on and come home. But I wish I knew what that monkey business with the watch was all about."

"I think I know," Judith answered. "It explains why he asked you out here in the first place, and—" but she was cut off by her brother's abrupt whisper:

"Cut it! Here they come!"

He tensed, his gun hand lifting, and I heard the stealthy scrape of feet on the cellar stairs. They came off the wooden steps, and whispered toward us, slowly, hesitantly on concrete. Queer. There seemed to be only one pair of them.

"Trouble with this position," Bill muttered, "there's no field of fire. I can't see—" His gun clicked sharply. "That's near enough!" he called. "Stop there!"

"Shhh," a hiss silenced him. "They'll hear us! This is the clerk. Jenkins."

Even in his whisper I could detect the extent of his terror. "I want to get out of here."

"In a pig's eye you do!" Bill scoffed. "What's the trick?"

"No trick. I swear. I want to get away from those terrible men. Listen: the combination of that padlock is two—Start at two, turn right to four, left full circle and stop at eleven."

MOORE glanced back at me, eyebrows raised quizzically. "I'll try it." I whispered. The dial shook under my fingers. Two. Clockwise to four. Counter-clockwise a full turn. Eleven. And the shank clicked free!

"That did it," I muttered, pulling the lock out of the hasp. "He didn't lie."

"But I still don't trust him. Don't open that door yet. Maybe they're laying for us outside. We can't have this light behind us—Hey you! Jenkins!"

"Yes?"

"Go back and turn off that switch. After the light goes off, stay there till you count a hundred or you'll get a lead slug in your brain. We'll leave the door open for you."

"All right—all right." Feet pattered away.

"He's frightened." Judith whispered. "The poor little man is really terrified. Bill. I'm sure he's not playing a trick on us."

"We'll soon find out."

Sudden darkness enveloped the cellar.

"Get that door open, Mr. Lanham." Hinges grated and cold air gushed in. It was full dark outside.

"Hold it," Bill pushed past me. "Wait here a second, you two, till I see." He went up steps, stooped, blackly silhouetted against night sky. "Okay," his murmur drifted down to me. "Coast seems clear. Come ahead but keep low."

I took Judith's arm. Stone treads were under our feet, then cinders crunched. Yellow luminance from windows above us spread across the parking lot at the rear of the hotel, just touched the vague bulk of standing autos. Bill materialized beside us.

"Let's go. If we can make the Boulevard we'll be okay!"

White light leaped at us from between two cars, blinded us.

"Drop it!" a gruff voice ordered. "Drop that gat and hoist them, fast!"

Behind us, the cellar door clanged shut.

HE blue-nosed revolver beside the small sun from which that white light flared held us motionless.

"You rats should have figured we'd be covering the back," grated the vague silhouetted figure with the gun. Other forms closed in on us from around the corner of the building. A window grated open, high above us.

"What's going on down there?" someone called down.

"I've got 'em, Chief," our captor replied. "They come up out of the cellar." Guns glinted in the hands of the men who surrounded us. Brass buttons glinted.

"Police!" Judith sobbed. "Oh, thank heaven! They're police!"

"Bring them into the lobby," the voice from above called down. "I'll meet you down there."

The lobby was now crowded with burly, iron-jawed men, some in civilian dress, others in uniform, but all grim-faced. A policeman's fingers dug fiercely into my biceps and William Moore was held as ungently by another, while Judith was watched warily by a squat and alert-eyed detective.

"The mistake you made," Chief of Detectives Joseph Martin said to me, "was to forget no one ever walks along that road past the ash dump." He stood straddle-legged before us, gray haired, leather-visaged, thin lipped. "Or hardly anyone. After the first of the afternoon dump trucks came to that mess you left back there, and it was easy enough to follow your footprints."

A small sound in Judith's throat pulled my eyes to her face and then in the direction she was looking, toward the hotel desk. Barker and Jones were leaning against it and beside them, gray and insignificant, was Jenkins. Anger pounded at my skull, thickened my throat and I could not restrain a bitter taunt.

"The mistake you made, Jenkins, was to expect the police to shoot us down first as we came up out of the cellar and ask questions afterward."

"Shut up!" growled the policeman holding me.

"Go on, Mr. Lanham," Martin said, softly. "Tell me what you're driving at."

"What I'm driving at is that while you were searching for us upstairs, leaving this lobby empty, that fellow, Jenkins, slipped down to the basement and told us how to get out, hoping that as we came up the steps we would be silenced by bullets."

"Bosh!" This came from Sutton, the detective who had been waiting out there. "Nobody went down in the cellar. Nobody could have gone through that door there without my seeing him."

"Granted. But he didn't go that way. He came down to us through—" My pointing finger hung, startled, in midair. There was no door for it to point at—no sign of any opening in the partition behind the counter!

"Go on," Martin said again. "Through where?"

"That's why you didn't search the cellar first." And why it had been so long before anyone had come after us. I could guess now exactly what had happened. "Those three were all in the lobby here when you arrived, weren't they?"

"Yes."

Of course! Jenkins had heard the police sirens, had dragged the other two out of the office before they had arrived. "Barker and Jones were unconscious or perhaps just coming to. They told you that they had found us hiding somewhere in the hotel, had tussled with us and lost. Right?"

"Right," the detective agreed. "They insisted you had stolen a car and escaped but I knew you couldn't get past the road blocks we've had set up ever since noon to trap Moore so I figured you still were somewhere in the joint. We would have looked in the cellar immediately if they hadn't told us the only entrance was from outside and that door was locked tight."

"Yes. They had to keep you out of there at all costs, for more reasons than one. But they knew you would eventually insist on going down there so they watched their chance to send Jenkins down to us, through—Mr. Martin—through a concealed door in that partition."

Martin turned to the little gray man, eyes slitted. "Okay, Jenkins. Get it open."

The fellow's legs seemed rubber under him as he tottered around the end of the counter, pawed at the partition. I couldn't quite see what he did but abruptly there was a vertical slit in the wood and then the door had opened and we were looking through into the luxuriously appointed, windowless room. "Look at that, George!" Barker exclaimed. "Imagine our living here all this time and never knowing about that hidden room."

"My stars!" Jones picked up the cue. "I never would have thought it."

"You can dispense with that," I told them, wearily. "Miss Moore and I will testify that you were in there with us."

"And so will I," Bill Moore added. "This afternoon and last night both. And what's more, your fingerprints must be all over the place. You can't get away with it. You're tied up to the racket, but good."

"Tied up to what racket?" Martin demanded. "What's this now?"

"They are textile black-marketeers," I answered him. "That inner door you see leads to the basement, which is chock full of illicit fabrics."

BARKER came a step forward, his pudgy hands spread wide.

"I must admit he is right." His soft, lisping accents had not lost their sinister quality for me. "That is why we did not tell you about that room when you were here before, Mr. Martin. There was no point in doing so. It had nothing to do with Harlow's death."

"That wasn't smart," the detective chided him. "It wasn't even legal. You were risking a charge of concealing evidence." He looked around. "Falcon, you and Sherry better look over that office, just to keep the record straight." The two plainclothesmen he addressed moved to obey and Martin turned back to Bill. "So you admit you were here last night, do you?"

"Sure, I was here. What of it?"

"Why did you kill your uncle?"

"Me kill—" The youth's jaw dropped.

"There are the murderers!" Judith broke in. Her hand pointed at Barker and Jones. "Those two." Tawny hair disheveled, face grimy with cellar dust, she was still magnificent. "They killed Uncle Rand and fixed things so Bill would be blamed for it, and I can prove it."

"She is insane," Barker observed, coolly, almost compassionately. "The poor girl has gone mad."

I almost believed that myself, for Judith had clawed open the buttons of her waist and was thrusting her hand in under the pale blue, lacy under things thus revealed.

"Maybe my uncle was insane too, Mr. Barker," she flung at him, "when he suspected that you meant to kill him and gave Bill a message accusing you. You found that out too late, didn't you? That's why you've been so desperate to get hold of this watch, where Uncle Rand hid it."

She had brought it out from somewhere in the frilly, intimate regions where she had delved.

"I didn't hide it in the ashes, Don," she told me. "There was nothing to mark the place with and I was afraid I would forget where it was."

"Let me have that," Chief Martin demanded. He took it, clicked the lid open and read the inscription. "Yes," he sighed. "This is Harlow's all right. We wondered why we couldn't find a watch in the room where he died. How did you get it?"

While she told him the whole sordid story, helped out by Bill and me for our parts, he was busy working at the watch.

Finally he grunted, started unscrewing the back.

"It was only after Bill told us what Uncle Rand had said, when he gave it to him, that I guessed what it was all about," the girl explained. "'Look a gift horse in the mouth,' he said. This was the gift and he meant that Bill should look in it."

The back cover came off in Martin's hand. There he found a folded tissue-paper. Jones started for it but a policeman shoved him back.

Martin scanned the almost microscopic handwriting with which the tissue was covered, looked up, his face mask-like.

"This is a list of about fifty names and addresses, Miss Moore, with numbers after them. See." He held it up so that we all could see. "It hasn't a thing to do with the murder."

All the animation, the triumph, drained out of Judith and her face was suddenly haggard.

"I'm sorry." The detective seemed genuinely so. "It still looks like your brother clouted his uncle over the head and then choked him to death. There is too much testimony that puts William Moore in that room up there. Not only the testimony of the four men, these three and the fellow who was killed in the road, which might be discredited now they are revealed as black marketers, but that of the book we found under the bed up there."

"What book?" Bill asked.

Martin's eyes moved to him. "Your algebra textbook, with your name in it. I suppose you will claim that was put there as part of the frame."

"Sure, I do. I took it along last night to study on the way here. I put it on the desk in there and forgot it when I left."

The detective shook his head. "I'm afraid that won't wash. It's plausible, but so is the story that you left it upstairs. You might be telling the truth. I don't know. All I know is that book's going to hang you."

Judith moaned. "Don! You said you wanted to help us. Can't you think of something?"

"Gosh, Mr. Lanham," her brother added his plea to hers. "If you only could."

Grimy light fell across his bony, angular face, glinted on the golden button in his lapel. I looked back from him to Judith, remembered how her hand had closed trustingly on mine, recalled how I had held her to me back there on the desolate road and how the road had no longer been desolate. I turned to Martin.

"May I see that list, please?"

"You can look at it," he said, "but in my hands."

I READ the names: The Acme Dress Company. The Superior Shirt Company. Women's Fripperies, Inc.

"You said this had nothing to do with the murder, Mr. Martin. It has everything to do with it. It's the motive."

"How do you mean?"

"That's a list of manufacturers who are desperately in need of textiles and will pay almost anything to obtain them." I glanced at Barker. "They are Harlow's customers, aren't they? The ones to whom he sold the merchandise you have stored down in the basement. He handled that part of the operation and kept the list secret from you."

I was guessing wildly, but this was the way it had to be. "He did the collecting too, and kept the lion's share for himself. You might have gone out and found other customers yourselves, but with the Federal operatives hot on your trail you didn't dare. So you killed Harlow for that list, and found that he didn't have it.

"You guessed what he had done with it, that he had suspected what you were up to and gotten Bill out here and given him the list hidden in the watch. 'Time is money.' You'd heard him say that and now you guessed what he meant and went all out, to the point of murder, to get the watch back, but it was too late."

Barker did not answer. He did not have to. The sick look in his tiny eyes gave him away. I turned back to Martin.

"That's the answer. They killed Rand Harlow for that list."

"Maybe." He was obdurate. "But you haven't proved it. It still looks like Moore."

"Good grief, man!" I exclaimed. "I wasn't here when they did it. I can't produce an eyewitness!"

"Hey, Chief," someone called from the office, one of the men Martin had sent in there. "We've got something." He appeared in the doorway. "There's some dried blood on one foot of this swivel chair in here, way underneath, and a couple of gray hairs are stuck to it. I'll lay ten to one they match up with Harlow's."

"So will I." Martin wheeled, strode to Barker, crowded him against the counter. "You told us Harlow went upstairs about ten o'clock, as well as he'd ever been. You and Jones and Jenkins swore to that, didn't you?"

"Y-Yes."

"You lied. You hopped Harlow in there after young Moore left. He slipped, or was tripped, and gashed his head against that chair leg. Maybe you finished him in there or maybe you carried him upstairs and finished him off there. Which was it?"

"Neither." Barker licked his lips. "I don't know anything about it." But Martin had whirled to Jenkins.

"You! Which was it?"

The little gray man's chin quivered, his lips were the color of his hair.

"I-I—" His terror was not pretended now. It was very real. "I don't know."

"You better know. You better remember, and fast. You swore with the others that you saw Harlow walk up there under his own power. That makes you as guilty as they are, even if you were out here in the lobby while they killed him." The detective's finger jabbed the scrawny breast-bone. "You'll hang with them unless you come over on the side of the law. You'll hang, Jenkins, hang by the neck till you're dead. Is that the way you want it?"

The bony jaw waggled as if it belonged to a mechanical statuette, the springs gone awry. "No!" Jenkins squealed. "No, I'll talk. I'll tell you how it was."

He did. His evidence was to hang Jones and Barker, gain him commutation to a ten-year sentence. But that was to come months later. By that time Bill Moore had graduated with honors, was doing well as a freshman in State U. He insists that this is because he gets help with his math from his brother-in-law.

Yes, Bill can have his discharge button. I've got his sister. Judith is my wife.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.