RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

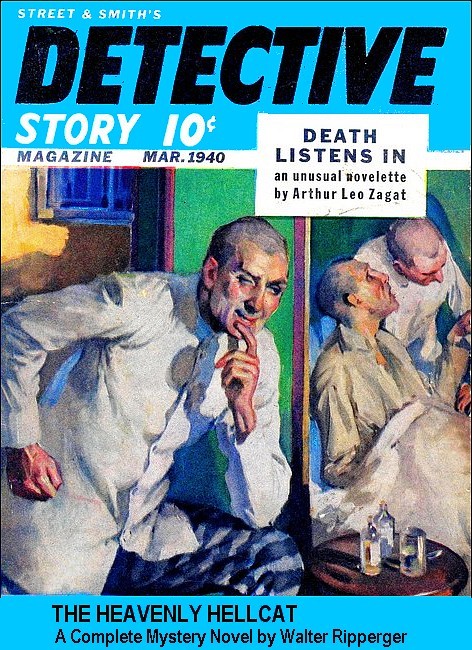

Detective Story, March 1940, with "Death Listens In"

WOLF FESDEN had served eight years in Lornmere Penitentiary, and so no one knew better than he that its reputation as the toughest prison in the State was, if anything, an understatement. Yet he deliberately contrived to have himself nabbed driving a stolen car down Sea City's principal thoroughfare, deliberately contrived to have himself sentenced to another long stretch at Lornmere.

Fesden was a veteran crook, as hard as armor plate, as shrewd and cunning and elusive as the gray killer for which he was nicknamed. This self-planned sentence was only one step in his great scheme. The next was to manage being placed in Cell 6, Row C, of Lornmere's Northeast Cell Block. This took some doing, but eventually he brought it off. Now he was Evar Galt's cellmate and he started right in worming the old man's secret out of him.

Galt proved a harder nut to crack than Fesden had figured. The weeks dragged into months and the months piled up into years and he was still at it.

Many a night, lights out and the keeper nowhere near, Wolf Fesden's long fingers itched to clamp on Galt's scrawny neck and choke the information out of him. Then the thin, sexless voice would start babbling again about the old fool's daughter Mary, about what a time she was having to keep herself and her three brats alive, and Fesden would settle back to listen to the blasted yarn all over again.

He heard it so many times he could rattle it off in his sleep. How Mary's husband Joe, "as fine a lad as ever lived," had been crushed to death under one of Pierce Ramsdell's limousines. How Mary couldn't get to first base with her suit for damages. "No lawyer would take it," Galt would whine. "She went to a dozen and they all said the same thing. 'It was your husband's fault; there was no negligence on the part of the chauffeur.' But they all lied. The truth of the matter is, they were afraid of going up against Ramsdell. They were afraid of what he'd do to them, with his money and his power." He knew, Evar Galt did, all about how everyone feared the tycoon, for wasn't he butler in Ramsdell's very own house?

"Look," Fesden said the first time his cellmate got to this point. "Whether the lawyers were right or not, seems to me with all his millions your boss could've done something for her, seeing she was your daughter."

"He didn't know Mary was my daughter. How could he? Her married name was different from mine. And even if it hadn't been, that would have meant nothing. I was only a servant to him, not really a human being but a kind of machine." There was no resentment in the old man's voice; he was simply explaining something that to him was self-evident. "The only time he would have been really aware of me was if I made some mistake in performing my duties, and I never did. I was the perfect servant.

"Yes," Galt went on, "I'd served them more than twenty years and I was the perfect servant. Which was why, morning after opening night at the opera, madame didn't think twice about sending me to put her jewel box back in the bank vault, like I'd done hundreds of times." He chuckled toothlessly. "She handed me half a million dollars' worth of Ramsdell's jewels in a casket no bigger than one of those big cameras the news photographers use and I remembered how my Mary and her little ones were faced with starvation and misery because of what Pierce Ramsdell had done to Joe, so this time I didn't take the jewels to the bank."

The blithering ass was nabbed right off, of course, but before he was caught, he'd managed to cache the loot. Nothing could get out of him where, not the cops' grilling, not Ramsdell's bullying or daughter Mary's tears. Not even the insurance company's offer not to prosecute if he'd give up the jewels.

The story had been all over the Sea City newspapers. Wolf Fesden had read everything printed about it, his mouth drooling as he studied the pictures of the stuff that was lying hidden somewhere, the secret of where known only to Evar Galt. When Fesden read about Galt's being sentenced to Lornmere, he had remembered how first-termers nearly always spilled their guts to the first con who would listen, and the Great Scheme had started bubbling in his brain.

The old man was anxious enough to talk. Night after night he would blabber his yarn—till it came to telling where he'd cached the jewels. Then a crazy glitter would come into his rheum-rimmed eyes. "When I get out of here," he'd mumble, "I'll go get them. Ten years isn't too long for Mary to wait when there's comfort, luxury, at the end of them."

Just about here he'd have a coughing fit, and when it was over, Wolf Fesden would go to work on him again. He would tell the gasping old man there was no need for Mary and the kids to live in want till he got out. The cunning crook would point out, over and over, that while Galt's letters, his monthly talks with his daughter, were watched for any tip-off to the whereabouts of the jewels, a code message in his, Fesden's communication would never be spotted. Again and again he would tell Galt about his imaginary friend on the outside who would go get the stuff and fence it and give the money to Mary, keeping only a quarter of it for his trouble.

Always the answer was the same. "Maybe. Maybe you're right. Maybe I'll let you arrange it for me. I've got to think about it." And Fesden's fingers would curl to fit Evar Galt's neck.

The only thing that stopped those fingers from taking hold of Galt's neck, from squeezing till the bleary eyes popped out, till the wheezing breath stopped forever, was a picture that would come up in Fesden's mind. Of an ugly, heavy-built chair dominating a bleak bare room. Of a man strapped in that chair, his body arced and straining agonizedly against the straps, a tiny wisp of smoke spurting out from under the contraption that covered his head and face.

The picture would rise between Wolf Fesden and Evar Galt's corded, thin neck, and a cold sweat would break out all over Fesden and his fingers would uncurl, and he'd start again trying to wheedle his secret out of Galt.

MORE than three years that sort of thing went on in Row C,

Cell 6, night after night, night after night. Then, one mid-winter night, Galt's coughing spell kept on and on till suddenly

the scarlet blood gushed out of his mouth, all over him, and they

took him away to the hospital.

That morning Wolf Fesden laughed silently to himself as he swabbed blood from the cell floor. This was the break he'd been waiting for. Galt would never live to leave Lornmere. He'd know that, soon enough, and he'd know that if he didn't tell somebody where the jewels were, Mary would never get a chip of them. Fesden was going to make sure he would be that someone. He started right off pulling wires for assignment to the detail of hospital trusties.

It took over a month and when Wolf Fesden got his way at last, he found that another trusty, a convict by the name of Bert Corbett, had gotten the inside track with Galt.

A tight-mouthed, poker-faced fellow was this Corbett, kind of young to be in long enough to be made a trusty. Fesden didn't remember ever having seen him around the yard or the workshops, either this stretch or the one before. But then Lornmere was a big place and no one could know all of the more than two thousand convicts it held, so that didn't mean anything. What bothered Wolf Fesden was the way Corbett hung around Evar Galt's bed, the way he'd give the old man an extra alcohol rub whenever he had the chance, or sneak some extra tit-bit to him from Doc Lowrey's lunch tray in the kitchen.

If it weren't that Dr. Lowrey made the trusties alternate among the three wards—the surgical, medical, and tuberculosis—for night duty, Fesden would never have had a chance to talk to Galt without Corbett hanging around somewhere within earshot. So when Fesden's turn in the T.B. ward came, he'd get the other patients bedded down and snoozing and then he'd bump the old man's cot or drop something on him, to wake him up.

Galt's eyes would open, down at the bottom of their bluish sockets, and they'd look at Fesden for a minute. Then they'd close again, tired-like, and no matter how long he sat there whispering, they'd never open.

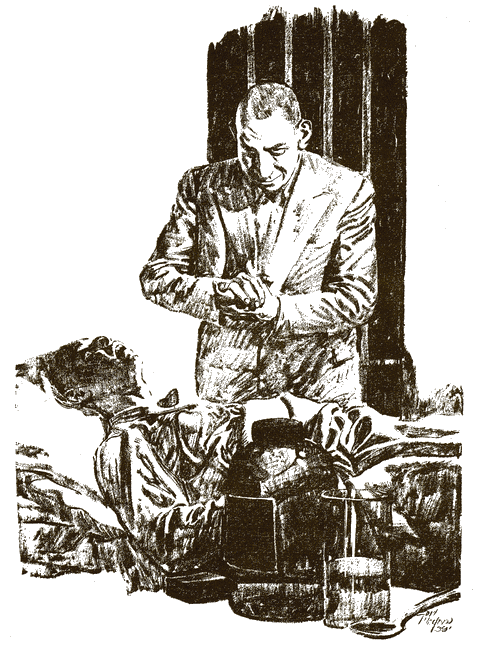

"You're going to die," Fesden would whisper. "You're going to die soon, Galt. You can't ever go get the jewels yourself. If you don't tell me where they are, they'll stay buried and Mary will never get anything out of them."

"You're going to die soon, Galt," Fedsen whispered.

"You can't ever go get the jewels yourself."

THE first few months Fesden wasn't any too anxious for Galt to

come through, because he needed time to build a new set-up for

the next step in his Great Scheme, his break-out.

Lornmere was surrounded by two great walls. The cell blocks and the shops were all within the inner one, a pile of grim, gray granite surmounted by a fence of barbed wire. The outer wall was twenty feet high to the other's fifteen. Between the two there stretched a fifty-yard-wide strip of concrete sun-washed by day and brilliantly flood-lighted by night. The prison hospital, where Fesden and Galt now were, stood in this space and the only other structure that occupied it was the administration building.

Only the barbed wire protected the top of the inner wall, but the outer one was studded by little stone towers that gave it the appearance of some medieval battlement. From within these, armed guards constantly watched every inch of the outer wall and of the space between them.

The guards were changed every four hours of the twenty-four, so as to make certain they would be on the alert. They worked in eight-hour platoons and the patrol of each platoon not on the wall at any one time was held on reserve in the one-story guardhouse that formed one side of the tunnel-like main gate, about a quarter of it projecting into the space between the walls. The towers could be reached only from within this guardhouse, by a steel ladder that rose from the roof of this projecting part.

Wolf Fesden got the guards of the four-to-eight-a.m. patrol into the habit of coming over to the hospital kitchen for coffee right before they took their stations on the wall. He did one other thing during those first few months he was a hospital trusty. From the doses that were intended to bring healing sleep to the prison-crazy patients who composed more than three quarters of those in the medical ward, he stole, grain by grain, enough veronal to fill a discarded pillbox he cached behind the kitchen sink.

After these two matters were accomplished, Fesden had nothing to do but wait till he was alone with Galt in the dim half-light of the sleeping T.B. ward, so that he could wake up the old man and whisper to him.

For all the response it made, the head on the pillow might have really been the corpse's skull it kept looking more and more like.

The thing began to get Wolf Fesden.

He couldn't sleep any longer. Whether he was on day shift or night shift, he kept prowling the hall all the time he was off duty, kept prowling into the T.B. ward. But the worst times were when he was night orderly in the medical ward tending the convicts the prison had turned into raving maniacs, because those nights he knew Bert Corbett was in with the lung cases. With Galt.

Evar Galt came to be nothing but a skin bag of bones, more dead than alive except when he started coughing. Wolf Fesden began to get a queer idea that when he gave the old man his morning sponge-off, he could look right through the hot, dry skin, could look right into the big holes in Galt's lungs and see the little bugs that were eating away what was left of the old man's lungs and his life.

And then, one night when he was on duty in the medical ward, he thought he could hear the bugs swarming inside his own skull for one terrible second.

Fesden got rid of that feeling right away. But he knew what his getting it meant. He was going stir-crazy!

He was still all right, but if he didn't get out of here, quick, he wouldn't be all right long. He had to get out! He had to get out of here tonight and leave Galt to die with his secret locked between his thin, blue lips.

Galt wouldn't die with his secret! Fesden had figured that long ago, and he knew he was right. When Galt knew he was about to die, he'd tell someone. He'd tell... he'd tell Bert Corbett.

No! No, damn it!

Not after the four years he'd spent trying to worm that out of the old fool. Not after all he'd gone through. If Galt didn't tell Wolf Fesden, he'd tell no one.

Fesden remembered the bottle on the stool by Galt's cot, the bottle of stuff to stop the coughing spell the old man always got around five in the morning. Doc Lowrey had said never to give him more than ten drops in a half glass of water. There was morphine in the colorless mixture, and a little too much would put the old man to sleep permanently.

Fesden knew just what he was going to do! He'd go around there, get talking to the guy on duty in there, watch his chance to kick Collucci's cot, near the door. Collucci always started coughing like mad when he was waked up sudden, so while the trusty was fussing with him, Fesden would have a chance to dump a big gob of the morphine mixture in the water glass that would be waiting ready on Galt's stool.

This done, Fesden decided, he would go down to the kitchen and start boiling the coffee for the guards. He'd take the little pillbox of veronal from behind the sink and spill it in the coffeepot, and he'd make the coffee extra strong so the guards wouldn't notice the taste of the veronal. And then... and then he'd wait till half past four and walk out of Lornmere. As he was going over the wall, the trusty would be putting ten more drops of the morphine mixture in the glass—would be giving Galt the dose that would finish him and his secret together.

Murder? Sure. But he'd be in the clear. If they tumbled, it would be the other trusty would catch hell. Abruptly Fesden's lank jaws opened in a silent, wolfish laugh. He'd just remembered who was on duty in the T.B. ward. Corbett! That made it perfect.

He stopped laughing and went out of his ward, and went down the hall to the door of the lung room— and stopped in that doorway, his mouth going dry, his eyes slitting.

A green screen was around the head of Evar Galt's bed! That meant Galt was kicking the bucket! Tonight! And not only that, there was a sound of voice from inside the screen. Bert Corbett was in there, and Galt was talking to him!

WOLF FESDEN went down the length of the T.B. ward, the thick soles of his prison shoes making no sound on the concrete floor. He reached the screen and went down on one knee, and laid his ear against the green burlap.

"The devil you're dying," he heard Corbett say. "I just put the screen around you to keep the light out of your eyes."

"Don't... try to... deceive me." Galt's voice was a mere shadow of a voice, as if he were a ghost already. "I'm... dying. I'll never... leave this place... alive."

How could he get Corbett out of there?—Fesden thought frantically. How could he get to the old man, to tell him this was his last chance to talk, his last chance to take care of Mary? If that didn't work, he'd tell him he'd snatch the kids, he'd snatch Mary, he— By Moses! He'd terrify the old fool into spilling—

Wait! What's this Corbett was saying?"—Good news today, and I want you to know it. My parole's coming through. I'll be out of here in a week."

"Glad—" That ghostly shadow voice again. "You've been... kind... eased my last days."

"Tried my best, but it wasn't much. Look, Mr. Galt. If there's anything I can do for you when I get outside, give your daughter a message or anything, I'll be happy to—"

"Message?" the dying man gasped, and Wolf Fesden stopped breathing. "To... Mary? Thank Heaven! Bert... lift me... nearer you."

"Sure." Creak of rusted spring, rasp of harsh cotton sheet on harsh prison nightshirt. "There. That better?"

"Kind... so kind—" Galt's voice was now so faint that Fesden, listening finger to chin, had to close his eyes to hear it. "Listen, lad. Tell Mary... Mary Lane... 230 Morris Street... tell her... Frog Creek Railroad... Bridge... west side... north abutment ... dig... dig—" That rasping was a long sigh as an old man's last breath left his wasted body. It was the scrape of harsh sheets as skin-bagged bones settled down into them.

FESDEN was on his feet and out of the ward, his clodhopper

shoes on the concrete floor as silent as his lank-jawed laugh.

Stir nuts, was he? Screwy, was he? But Evar Galt had told him his

secret at last, and that Corbett had heard it, too, didn't matter

in the least because Corbett wouldn't be out of Lornmere for a

week. By that time Wolf Fesden would be a thousand miles away

from the railroad bridge over Frog Creek, just outside Sea City,

and the jewel case no bigger than a camera would be with him.

Brewing the coffee in the hospital kitchen, pouring the pillbox full of veronal into the pot, Fesden kept silently laughing to himself. Only a second he stopped laughing, when the thought struck him that if he put in too much of the white powder he might kill the guards instead of just putting them to sleep. Then he remembered that he'd worked it out, experimenting with the stir nuts.

The guards came tramping in, the six of them, and Fesden kidded around with them, and he thought it was very funny that the coffee they, were drinking to keep them awake was going to make them fall into a sleep from which they wouldn't wake till morning. He even picked up Jim Carroll's rifle, and squinted through its sights, and knew he could shoot with it as well as he'd shot when he was a sniper in the War.

They tramped out. Fesden started watching the clock over the stove for the half hour to pass that he figured he'd have to wait till the guards were safely asleep in the towers.

It got quiet in the hospital kitchen, so quiet that the clock's ticking was like a fast little hammer, tapping his skull.

There were footfalls walking along the hall outside! Hell! Doc Lowery had come in for a late look-around, like he sometimes did.

The knife drawers were locked, but Fesden snatched up a heavy wooden potato masher. He switched off the kitchen light and opened the kitchen door, soundlessly.

In the dim light from the ward doors he saw a slender figure going toward the front end of the hall. Not Doc Lowery! White coat, striped trousers—it was Bert Corbett. What was he—

Corbett stopped at the phone on the wall just inside the door of the hospital, the emergency phone they used to call Doc from his house outside the walls in case he was needed in a hurry. Fesden grinned with relief. He ought to have known. Corbett was calling the Doc, of course, to tell him that Galt had passed out.

Doc would grunt sleepily, say: "All right. Wash him up and I'll sign him out in the morning." He always—

"Doc?" Corbett said into the phone "Galt's gone, Doc.... No. I got the dope out of him, the last moment." Wolf Fesden's skin got tight across his forehead. "Yeah," Corbett said. "Yeah. I'm sure glad this job's over. I'll never let myself in for another one like it."

He was a lousy dick! A plant! Fesden went down the hall, his feet making no sound. "Look, Doc. Will you get me a line through to—No. I guess I'd better not risk spilling it over the phone. Tell you what. You phone Mr. Boswell for me. Tell him to get me out of here first thing in the morning." Fesden was right behind him, the potato-masher's handle gripped tight in a sweating hand. "Thanks, Doc. Thanks for everything. Night."

Bert Corbett put the receiver back on its hook. Fesden swung the masher against the back of the detective's shaved skull hard. So hard the bone crushed in like papier-maché.

Wolf Fesden dropped the wooden mallet on the crumpled heap at his feet. His gaunt jaws opened in the noiseless, yellow-fanged laugh that had given him his moniker. Nobody was going to get Corbett out of here in the morning. Nobody was ever going to get him out of here. And he wasn't ever going to tell anyone Evar Galt's secret.

A MINUTE later Fesden was out of the hospital. He walked

briskly, but unhurriedly, toward where the end of the guardhouse

jutted out of the outer wall. There were no windows there, but

there was a little door and he was watching it. There was a

chance, the barest chance, that door might start to

open—

His spine prickled with the sensation of eyes on him! He didn't move his head, but his own eyes slid sideways, focused the low bulk of the administration building. A single window was alight in the dark wall, a yellow rectangle black-striped by the cage of bars over it. The light silhouetted the form of a man standing in the window, peering out at him. The deputy warden!

Fesden's throat went dry, but he didn't hurry his pace, didn't change his direction. He still had twenty feet or so to go, and he had to get across those, at least, before things started to pop. There was a good chance he might make it. He had the white coat of a hospital trusty, and only cons with the best of conduct records rated that. If he acted like he had every right to be doing this, the warden might figure that one of the guards on the reserve patrol had phoned for him to bring over some bicarb for indigestion or creosote for a bum tooth.

Fifteen feet more. Ten feet. Fesden's long legs ate up the concrete and still no yell. Nothing. Five feet. Now! He veered into black shadow in the angle the projecting side of the guardhouse made with the wall—bounded to the corner.

His toes found roughness of stone. His back found stone behind it. He was hitching up the wall angle, knees and back as a mountaineer ascends some Alpine "chimney," as he himself had done so many times to reach some second-story window left unlocked because it was "impossible" for a thief to reach it. His shaven head came above the guardhouse roof, into the light again—

An incoherent yell broke the prison silence. Fesden gained the roof, leaped for the iron ladder, was climbing it with monkey-like swiftness. "Escape!" the warden shouted. Fesden threw a glance over his shoulder, saw him leaning out against the bar cage, saw his arm clawing for a gun.

"Escape!" the warden yelled again. There was rattle of door bolts below Fesden as he reached the wall's top, leaped into Tower 1, at the head of the ladder, snatched a rifle from the hands of the sleeping guard, was out again in the open. The hinges of the guardhouse door creaked as it started to open. The warden's arm flung out through the window bars, pointing out Fesden and aiming his revolver in the single act.

The pound of that revolver, the rifle's sharper crack, were one sound. Fesden heard whistle of futile lead past him, saw the warden slump in the bar cage, heard shouts, thud of running feet beneath him.

The reserve guards! They'd opened the door too late to see the warden point. They'd never think of looking up here. Wasn't the wall covered by the men in the towers?

They were pouring across to surround the administration building, to skirt the hospital, looking for the killer. Fesden put the rifle down on the runway, let himself down over the outer edge of the wall.

He hung by his hands an instant, glancing narrow-eyed down at the next tower, where the wall turned. Tough luck, he thought, that bloke had to look out of the window just at the wrong time, so he'd had to bump him. But it could have been lots worse. The guy could have been a better shot, or the wall could have been built straight up and down instead of sloping out a little, like this.

Fesden let go. He slid down, keeping hands and face away from the rasping granite. That threw him away from the support of the slight slant, but his free fall was only about eight feet, and he landed in soft grass. He leaped to his feet at once and darted across a wide belt of close-cropped turf to the black mass of bushes and second-growth trees beyond it.

Dew-wet leaves, twigs, slapped his face. Then he'd gone far enough in so that the illumination from the wall no longer made bright spangles in the darkness. He slowed, worked deeper into the thicket, only a slight rustle betraying his movements.

The pale glimmer of three slender birches gave Fesden his direction. The earthy smell of leaf mold was in his nostrils and there were sudden scutterings about him as small woods creatures were disturbed by his passage. A glacial boulder, moss-covered, blocked his way. Instead of going around it, Wolf Fesden dropped to his knees, shoved against it with his hands, muscles straining across his back with effort.

A low moan began, back where he'd come from. It increased in volume, swiftly, till it was the enormous howl of Lornmere's siren. The boulder started to roll, moved more quickly, was stopped by a hummock of earth behind it. Fesden's steady hand felt in a hollow in the ground where the big rock had rested, found the suitcase-sized metal box he had buried here four years ago.

The siren probed the night with its howl, rousing the countryside. Under it lay the roaring chug of the prison's big pursuit cars, filling with armed men. For fifty miles around State troopers were rushing to bar the crossroads and warn late-traveling autoists not to let themselves be stopped between towns on any pretext. Householders were waking to double-lock doors, windows. A radio operator's drone was broadcasting Fesden's description and teletype wires were carrying it to the police of seven States so that they could watch the entrances to their cities for him.

Wolf Fesden knew every mesh of the net that was being thrown around him, but his hands were unhurried as he peeled off the adhesive tape that sealed the box against rot and mildew. He lifted the lid, propped it open on its hinges. In spite of the tape, a musty odor came up out of the box, and the inside of the lid's edge felt sticky with mold.

A pallid searchlight beam scythed the sky, then slanted down to lay its glare on the river. The siren howled, deep-throated, heart-stopping. Fesden calmly stood up, unbuttoned his white coat and shrugged out of it, ripped open the buttons of his striped convict pants. The roar of the pursuit cars rose to a muted thunder that surged away down the road that led from the penitentiary. He sat down on his discarded clothing, noted that the sound of one of the cars stopped moving, backfired to silence. That would be the one that would lurk where the highway curved out of sight of the walls, waiting to shoot him down if he came out on it from the thicket. He unlaced his clodhopper prison shoes, swiftly but deftly.

From the direction of the howling siren, bushes started to rustle with the movements of the keepers assigned to comb them. Wolf Fesden reached into the box, took a hairy wig from it. He adjusted this to his shaven poll, recalling how many hours he'd practiced doing this just right in the dark. He found a flannel shirt next, corduroy trousers.

Flashlights flickered like fireflies in the Stygian foliage. Men called to one another hoarsely, something in their voices betraying the fear that was denied by their bluster. The threshing, wide-spaced line came on slowly, relentlessly, to flush Fesden and drive him out into the glare of headlights on the road.

He rose, fully dressed, bent, put his betraying prison garb into the empty tin box, closed it. Straightening, he went around behind the boulder, shouldered it down again over the hole.

The night throbbed with the incessant howling of Lornmere's siren. It filled the air with alarm— and covered whatever small noises Wolf Fesden made as he pushed in between two interlacing bushes and waited.

Trees, bush leaves, abruptly became a black, shimmering pattern against light that struck through into the small clearing around the boulder. Wolf Fesden stiffened. A bluish-barreled revolver pushed a low bough away from in front of a heavy-jowled, wet-streaked face topped by a uniform cap. A keeper shoved through the bushes into the little opening.

He pulled in breath, wiped his forehead with the edge of his left hand, the beam from the flashlight it held darting across the leafy ceiling over him. Fesden's long arm shot out. The keeper's mouth gaped open, but before the shout could come out, the stone in Fesden's fist crunched against his forehead. The convict caught the flashlight as it fell from numbed fingers, caught the keeper's body in his other arm and let it down gently to the ground.

Instantly, he pushed into the shrubbery, moving noisily in the same direction as, but dropping farther and farther behind, the line indicated by the rustlings and the winkings of the other torches. After a minute or two, he clicked his own light off, stopped, stood taut, listening.

The noises the cordon of hunters made kept moving on through the thicket. Fesden laughed silently, slipped off to the right, toward the river.

Guards scanning the wide waters with the searchlights, intent on spotting a swimmer or a small boat, never thought to look directly beneath them, where a tall, gaunt shadow flitted along the base of Lornmere's towering outer wall. Police at the ferry to Ashley, a mile to the north, saw no reason to stop or question any of the roughly clad, yawning workmen who trooped past them and aboard the morning's first boat.

One of the workmen was tall enough to match the description of the escaped prisoner, but he was hatless. While this Wolf Fesden might have procured some civilian clothes somewhere, he couldn't have grown a thick shock of hair overnight, could he?

"YOU'RE a murderer!" J. Latham Boswell, looking in pajamas and bathrobe like anything but the vice president in charge of Claims and Recoveries of the Sea City Burglary Insurance Co., licked fat lips and goggled at the man who'd called him that.

"You killed Bert Harris the day you sent him to Lornmere to pigeon Galt, under the name of Bert Corbett," John Porter went on, low-voiced, gray eyes accusing, knotted small muscles ridging his blunt jaw. "That was no job to hand to a youngster just breaking in." His undersized, deceptively slender frame quivered with rage. "It's a wonder he lasted as long as he did with that gang up there." The only hint about him that he was the singular bright star of the company's private detective force was the puckered bullet scar over his left temple that was not quite covered by hair as black as midnight.

"What could I do?" Boswell excused himself. "When Dr. Lowery telephoned me that Galt had been taken to the prison hospital, you were out on the coast, remember, and Bill Haynes was tied up with that big drug theft. I couldn't pass up a chance to wipe out a five-hundred-thousand-dollar loss for the company, could I?"

"What was the hurry? You could have waited—"

"I thought Galt might be easier to inveigle into talking before he got over the first shock of realizing he was going to die in prison. After Harris was up there, it was inadvisable to replace him with a more experienced operative. But I didn't get you here at six thirty in the morning to discuss my mistakes. We still have our duty to the company, John. To the stockholders. We're not licked yet. If we act shrewdly, we may still be able to recover the Ramsdell jewels. Shrewdly and quickly."

A pulse throbbed in the detective's temple. "You mean—"

"I mean that it is obvious this Fesden overheard Galt reveal the hiding place to Bert Harris, and killed the latter to silence him, since otherwise the murder would be reasonless. Beside our man, the escaped convict has killed two others and so there is no possibility that we could induce the authorities, were he to be apprehended by the police, to consent to an amelioration of his sentence in exchange for restitution of the Ramsdell loot. But we have certain contacts with the underworld, as you know better than I, that might enable us to beat the police to Fesden, and if we can reach him—" He spread his pudgy hands wide.

"We can make a dicker with him," Porter filled in the hiatus, his mouth thin and color-drained. "If he'll turn over the Ramsdell loot, we'll help him get away. Is that what you're getting at?"

"Of course not." Boswell's fat-drowned little eyes were shocked. "I wouldn't dream of making the company accessory after the fact to multiple murders. I simply have in mind that we might persuade Fesden that it is to his best interest to cooperate with us. With fifty thousand dollars, say, at his disposal he would be able to retain an outstanding attorney, employ alienists, perhaps, to substantiate an insanity defense. Now do you understand?"

"I understand," John Porter responded, his voice lower even than before, his tone milder, "that you're so putrid you stink. That swell lad isn't cold yet, up there on a slab in the Lornmere morgue, and you're hot to strike a bargain with the man who caved in his skull. I've put over many a lousy deal for you, but this one's beyond my limit."

"My dear John," Boswell protested. "How could you do me such an injustice after all the years we've worked so closely together? You are the last man I would have suspected not to comprehend that it is precisely because of my great grief for Bertram Harris that I am so anxious to recover those jewels. He gave his life for them, John, like a soldier on the field of battle. It is incumbent on us, the living, to succeed where he has so nobly failed, to see to it that he has not made the supreme sacrifice in vain. Merely executing Fesden will not atone for Bertram's death, We—"

"You're a buzzard," Porter broke in, "bloated fat on offal a self-respecting rat would stick up his nose at. You don't mean a word of what you're saying. But you happen to be right, damn you. Bert knew he might get a knife in his back, any minute, if he gave himself away, but he stuck to his job. He'd want it finished, and I'm going to finish it for him. Not for you or your blasted company, but for Bert Harris. Not your way, Boswell, but mine."

AT about three o'clock that same day, Wolf Fesden was climbing

a long green hill, his pulses hammering. A little before noon, he

had dropped off the train from Ashley at Millville, had tramped

the final seven miles toward Sea City, along back roads, through

fields. He was tired, dead beat, and not only because of the

long, arduous walk. Even though he had kept telling himself that,

disguised as he was and at this distance from Lornmere, no one

could possibly suspect him, every yard he had progressed, every

inch, had been a matter of taut nerves, of wary watchfulness.

This was the last hill. When he got to the top of it, he would look down on Frog Creek. On the railroad bridge at the base of whose abutment Evar Galt had cached a fortune four years ago.

He wouldn't be able to dig it up right away, of course. Walking south as he was, the railroad skirted this narrow hill to his left. To his right ran Harding Boulevard, whose bridge, he recalled, crossed Frog Creek less than a hundred feet west of the railroad trestle. Between was flat land, nothing to hide him. He'd have to wait till dark. But he'd at least take a look now. He had to. Hadn't he gone through four years of hell just to find out where to look?

He came to the brow of the hill, pushed aside a bush that obscured his view. Then his breath caught in his throat! A vein swelled in his temple, swelled till it was about to burst.

The yellow of freshly dug earth gashed the green banks below him. A steam shovel hissed and swung its crane like some gargantuan, prehistoric monster. Men, laborers, swarmed on the banks of Frog Creek just below him, their backs rising and falling, their spades and pickaxes flashing in the sun!

Digging! A hundred men were digging, down there! They couldn't possibly miss—

Abruptly, Wolf Fesden breathed again. They weren't digging anywhere near the north abutment of the railroad trestle. The nearest of them with a full seventy feet away from it.

He saw, now, a little to the right of where they worked, a temporary wooden structure over which the stream of motor traffic surged. What was being built there was a new bridge for the highway. The excavation was close, too damned close, to Galt's cache, but it was far enough away for safety.

Wolf Fesden's lean jaws opened in his silent laugh. This was a break, a real break. He started moving again, climbing down to that beehive of activity. He didn't have to skulk around in the bushes now till night. He could go down there, sit calmly on the creek bank overlooking the excavation. The laborers would think him some poor fellow out of work, watching and envying them. The cops patrolling the highway, scanning every car and truck for the prisoner escaped from Lornmere, would figure him, if they noticed him at all, as a sub-engineer or city inspector overseeing the construction.

DUSK lay gray against the big windows of J. Latham Boswell's

office, on the nineteenth floor of the Sea-view Building in

downtown Sea City. John Porter, bluish pouches under his eyes,

his face deeply lined with weariness, dropped the telephone

instrument into its cradle, said: "That's that. The police

haven't a trace of Fesden."

Boswell spread his pudgy hands wide. "We're through, then. The fellow is five' hundred miles away from here and getting farther all the time."

"No." Porter's lips hardly moved as he spoke. "He's somewhere in Sea City, or close by."

"How do you arrive at that conclusion?"

"Very simply." The puckered scar on the detective's brow seemed to pulse with a life of its own. "Galt didn't have time to get very far with the jewels before his arrest, so Fesden had to come back here to get them. Even if he had nerve to come right into town by train, he couldn't have reached here before noon. Say they were in some spot he could get at without waiting for dark, we still have to allow him another hour to collect them. By that time I'd flown up to Lornmere, spotted the dug-in footmarks around that stone in the woods where the keeper was killed, unearthed the tin box under the boulder and discovered the brown wig hairs stuck in the mold on the under side of the box lid."

"And instructions had gone out," Boswell broke in, "over the police teletypes, for the searchers to stop every man of approximately Fesden's height, in cars or truck or on trains within reaching distance of Lornmere, and make certain he isn't wearing a wig. I see what you mean, John. If Fesden is on the move, he would have been picked up by now. He is hiding somewhere in Sea City till the hue and cry dies down."

"And I'm going to find him before the night is over." John Porter wheeled away from his superior's desk, pounded stiff-legged toward the office door. "I'm going to find and bring the Ramsdell jewels back here and cram them down your fat throat, and that's going to cost you fifty thousand dollars, but Fesden doesn't get a cent of it. What Wolf Fesden gets," he flung over his shoulder from the doorway, "my dear boss, is the hot squat."

DUSK settled down into the excavation above which Wolf Fesden

sat. The steam shovel emitted a long blast from its whistle and

the laborers started to stack their shovels. A muscle twitched in

Fesden's cheek, but he didn't stir from the position he'd assumed

three hours ago.

Three interminable hours. Fesden laughed silently, thinking how the whole State had been looking for him and here he'd been all the time, hiding safely right out in the open. Suddenly his jaws closed with a click. What was this? A big bus had stopped on the road, just where the new cut branched off, and was disgorging men in overalls, in flannel shirts and corduroy trousers like his, dozen of men carrying lunch boxes. They were pouring down into the cut, were meeting the stream of laborers coming up out of it. Lights came on, blazing big lights. Strung on poles that he had not noticed before, they laid their brilliance on Frog Creek's greasy surface, sent their brightness all the way to the abutment of the railroad bridge!

What was going on here? He had to know. He had to know right away. He leaped erect, angled across the grass, grabbed the arm of a swarthy, unshaven Italian.

"What's the idea?" Fesden demanded hoarsely. "What are those lights for?"

"Wachyoo t'ink? Dissa breedge, she gotta be feenish' quick before get col', concrete freeze. We worka t'ree shift, alia day, alia night."

All night! "How long?" All night it would be bright as day around that abutment. "How long before it's finished?" How long before he could dig up the jewels?

The laborer shrugged. "Maybe wan week, maybe two. I don'ch know." He wrenched away from Fesden.

One week. Maybe two. Not long, after four years. But too long, terribly too long, when you're wanted by the cops of a whole State, of a whole country!

When you're wanted for murder!

The Italian threw a frightened glance over his shoulder at the tall man standing on top of the cut bank, standing motionless and staring after him. "I t'ink," he muttered, "I t'ink dat feller, he got the evil eye."

WOLF FESDEN sat on a rickety chair, powerful hands fisted on knees, and stared at a sagging, dirty-sheeted bed, stared at broken-plastered walls that were so close together they choked him.

The room was no bigger than a cell at Lornmere and the smell of it was worse. A black shade was down over the window, day and night. The unshaded bulb that hung from the ceiling on a cord crusted with fly-specks was never out. The door was so thin it didn't stop sounds from the hall, whenever there were any, and its paint was raddled with cracks. It was kept locked always. All color except that of dirt had long ago faded out of the carpet and it was full of holes. It was strewn with newspapers that Fesden had crumpled angrily into balls, and smoothed out, and crumpled again angrily when even a second reading and a third had failed to reward him with the item he had to find.

The item that would tell him the new highway bridge over Frog Creek was finished at last. That the lights were out and the laborers gone.

His name was in a couple of those papers, his rogues'-gallery picture, under it a caption beginning, "Five Thousand Dollars Reward." Fesden's upper lip snarled away from his teeth, thinking of that. If Gimpy Morgan— But no. Gimpy wouldn't turn him in for five grand, or for a hell of a lot more than that. The underworld has its own ways of handling a hide-out keeper who double-crossed one of his customers even if there wasn't altogether too much money in this business for him to kill it for the sake of any thinkable reward.

Look at what Fesden was paying Gimpy. Twenty-five dollars a day. Just for this lousy room, and the crummy grub the Dummy brought three times a day. He couldn't even get a bottle of liquor. A soused lamster might get noisy, and this house was a place of silence. Of whispers.

"Here's the rules," the one-legged hide-out keeper had told Fesden that first night, "and if you don't do what they say, you get thrown out of here, pronto. You check any heater or shiv you got with me. You stick in your room except when you got to go to the bathroom. When you got to' do that, you first knock twice on your door, to make sure there ain't nobody else in the hall, and you knock once when you get back, and you don't go out in the hall if you hear anyone else give the two knocks till you hear the one knock that says all's clear. You don't want nobody to see you and nobody wants you to see them.

"You don't drink and you don't start no rumpus. When you get ready to go, you let me know and I'll get you out a way no cop can pick you up. Meantime, you hand me twenty-five bucks every morning, when I bring your breakfast." He'd only brought Fesden breakfast the first morning, after that the Dummy had started coming. "Anything else," Gimpy Morgan had finished laying down the law of the hide-out, "is extra."

Extra was right. Fifty cents for the Morning Chronicle. Fifty cents for the Evening Star, Twenty-six dollars a day Fesden had been paying out for eight days now. Good thing he'd put a big enough wad in the tin box he'd buried under the boulder in the thicket outside Lorn-mere, four years ago. He had enough to stay here a month, if he had to.

If he had to stay here a month, he'd go nuts. Cripes! A month in here was worse than a year in Lorn-mere. You had guys to talk to, up there at Lornmere. You had things to do. You didn't just sit alone in a smelly little room. You didn't hear footfalls outside your door and go to the door and listen to them, listen to the sounds of men you wanted to talk to and didn't dare, knowing that even if you took a chance on it they wouldn't dare talk to you.

Up at Lornmere you scoffed in a big mess hall with two thousand other guys. You didn't eat greasy chow off a rusty tray. You weren't alone all day and all night. You didn't wait all day for the Dummy to bring you your tray, not because you wanted the food on it, but because you would see a human face for a few minutes, even if it was a face with a mouth that hung open, drooling, a dirty face with no sense in it at all, an idiot face with empty gray eyes and dirt-crusted, never-combed black hair that didn't quite hide the puckered scar on its forehead.

Up at Lornmere you didn't snatch the morning paper out of hands with black-edged fingernails and search furiously through it and not find what you're looking for, and then start waiting endlessly for the Dummy to come back with the evening paper. You didn't pace up and down, up and down your cell at Lornmere, your heels catching in the holes in the carpet, or sit like this on a rickety chair and stare at walls so close they choke you. You didn't listen, hour after hour, for the Dummy's shamble along the hall—

There it was!

Fesden jumped up and got to the door in a single long stride. He unlocked it and pulled it open, and the Dummy shuffled in, bent and dirty-skinned and vacuous-eyed, his idiot smile wet with saliva. Fesden slammed the door shut and grabbed the Star, his hands trembling as he spread it on the bed and leafed it over, page by page, his eyes burning as they read a headline and jumped to the next one.

The Dummy shambled on across the room, and put the tray on the paintless table against the wall next to the black-shaded window. He made little clucking noises with his useless tongue while he pawed paper napkins off the thick dishes.

Wolf Fesden's mouth was dry, suddenly. He snatched the rustling sheet up so the light would be better on it, and read the item over again, the two short paragraphs at the top of Page 11:

BRIDGE FINISHED IN RECORD TIME

Stone & Lambert, contractors for the new bridge that will carry Harding Boulevard over Frog Creek, announced today that the job had been completed six days before the deadline set by the highway commission. All that remains is the installation of the lighting system by the municipal electric department.

Formal opening of the new facility will be delayed till this is completed, but by tonight all of the contractor's equipment will have been removed and the site cleared—

A dish rattled and Fesden looked over the top of the newspaper

sheet.

The Dummy was looking at the back of the newspaper and in the instant their eyes met, the gray ones weren't empty!

The veil of vacuity dropped over them at once and they slid away. The Dummy started scuttling toward the door. He seemed to be moving quicker than he ever did before. He seemed to be in an awful hurry.

Of course he was! He'd seen what page of the paper Fesden had been reading. He'd seen where the item was that had got him so excited. He was in a hurry to go point it out, in another paper just like this, to Gimpy Morgan. Gimpy Morgan had figured out why Fesden paid a buck a day for newspapers!

"Here you," Fesden yelled, and started after the Dummy, his long arm reaching for him. The Dummy's toe caught in a hole in the rug and it -tripped him, and he squealed like a stepped-on pup as he went down.

He hit the floor and rolled, and Wolf Fesden was atop him, knee in his chest pinning him down.

"What's the hurry?" Fesden demanded, through tight lips. "What's your blasted hurry?" The Dummy made little mewling noises, his dirt-ingrained hands scrabbling to reach Fesden's knee and to push it away. "What—"

The word caught in Fesden's throat. The Dummy's scraping fingers had torn his shirt and through the rent there was gleam of metal, gleam of a silvery badge pinned to the Dummy's undershirt. "Private Detective," Fesden read, embossed on the metal. And the end of a half circle of embossed letters, "—ance Co."

All of a sudden the room was very still. Fesden stared down at the badge and then his eyes moved to the Dummy's face, and it wasn't an idiot's face any more, and the gray eyes were wide with terror.

"A shamus, eh," Fesden lipped. "A filthy insurance dick." His fingers curled and started moving, slowly, very slowly, toward the Dummy's straining neck. Slowly, but ready to clamp on any yell for help. "All right, wise guy, say your pray—" His right hand flashed sidewise and grabbed the Dummy's left hand, that was sliding out of a hole in his shirt, under the armpit, clutching a knife.

The Dummy squealed, and his thin body arched up, with unexpected strength, to throw Fesden off. Fesden struck at it with the knife that was somehow in his own hand, struck at the Dummy's breast and felt the blade slide in, to the hilt.

The meager form slumped, lay still.

"Lift them," a hoarse voice said, above Wolf Fesden. "Lift your mitts quick or you get lead in you!"

WOLF FESDEN'S head jerked around to the voice. A revolver, looking as big-muzzled as a cannon, snouted at him from the doorway and behind it was the dark-clothed, ungainly form of Gimpy Morgan. Fesden's hands went up over his head.

Morgan hitched in over the threshold, his artificial leg thumping the floor, pulled the door shut behind him. Between slitted, granular lids his tiny, bloodshot eyes looked down at the Dummy's still form, looked up again at Fesden's face.

"Nice," he grunted through thick, bluish lips. "Very nice. I thought I told you to check your shiv with me. I thought I told you there wasn't to be no rumpus here."

Fesden found his voice. "He was a shamus, Morgan. An insurance company dick, spotting me for some swag I copped before my last stretch. Look at that badge he's got pinned to his shirt."

"A dick," Morgan repeated huskily. "Holy— So he was." Under its three-day stubble of beard, his gross-featured gorilla face was taut-lined. "He sure put it over on me."

"I just tumbled to it," Fesden went on. "So I had to bump him." His elbows bent, starting to let his hands down. "I had to—"

"Keep 'em up!" Morgan ordered, his revolver jabbing forward. Fesden obeyed. "So you had to bump him," Gimpy went on. "In here. You didn't think maybe you ought to tip me off an' let me attend to him, did you?"

"I... I—"

"You didn't think that his office knows he was in here, an' that when he don't show up they'll be after me wantin' to know what's happened to him. That don't make no difference to you. You're sittin' pretty. You slit a dick's heart and you scram... and you leave me holdin' the bag." Gimpy Morgan grinned, showing yellow, rotted tusks, but there was no grin in his little eyes. "So you figure. But me, I figure different."

"What—" Fesden whispered through dry lips. "What do you mean?"

"I mean that it's you is gonna take the rap for this, not me. See? I run a crummy flop house, maybe. Maybe I don't ask no questions from the guys I rent rooms to. But when some kill-crazy screwball slices the heart out of my porter, then I gotta play with the law."

"You... you're not going to turn me in," Fesden gasped. "Gimpy, you can't! You'll be marked lousy and—"

"The hell I will," the other snarled. "Nobody's gonna mark me lousy for sliding out from under a murder rap. I'll be plastered with a fine for running an unlicensed rooming house, maybe. Maybe I'll even draw a stretch for harboring guys that's wanted. But for no filthy twenty-five bucks a day am I takin' a chance on a kill rap. No, mister. That rap you take all by yourself. The murder rap. The hot squat."

The hot squat! The ugly, heavy-built chair in a grim bare room! The agonized body straining against straps! The tiny wisp of smoke spurting from under the helmet that covered its face!

Wolf Fesden pulled the edge of his hand across his eyes to wipe away the picture, lifted the hand again before Morgan could growl, "Get 'em up."

"Look," Fesden said. "Look, Gimpy. You just said you wouldn't take no chance on getting smeared with a kill rap for twenty-five bucks a day. But how about twenty-five grand? Would you take that chance for that?"

The left corner of Morgan's mouth twitched. "Quit your kiddin'. You ain't got it. You ain't got twenty-five hundred. I—"

"I've got it, Gimpy. I've got a hell of a lot more. Listen to me. I'll come clean. You know why this dick was after me? You know why he didn't turn me in for the killings up at Lornmere and be done with it? Because he was after the Ramsdell swag. Five hundred grand in diamonds and pearls and emeralds. I know where it's cached, Gimpy. I can put my mitts on the stuff as soon as it gets dark enough. It's a half a million worth, but it won't bring only about a hundred grand from the fences. Play with me, Gimpy, and I'll split that with you, twenty-five—seventy-five."

Morgan blinked. "The Ramsdell swag... I remember. Hey! You're not kidding me, are you?"

"May I be struck dead right here if I am."

"And you'll split— Nope. No twenty-five-seventy-five. Make it fifty-fifty and it's a go."

"Gripes—"

"Fifty-fifty or I turn you in."

"O.K. You take care of ditching this stiff and get me out of here, and after I fence the swag, I'll send you your—"

"Nix," Gimpy growled. "I'll ditch the stiff all right, but I go along with you to pick up the loot, and we split it right off. I'll do my own fencing."

"Oke," Fesden gave in. "Have it your own way."

"It's a deal," Morgan growled. Then: "Get up and back to that chair and sit down in it."

"What—"

"Sit down there. I'm tyin' you to it till we're ready to get going. I'm not takin' no chances of your takin' a run-out powder on me."

There wasn't any use arguing further. Wolf Fesden sat down in the chair and put his arms around behind its back and Morgan lashed their wrists together with some wire he had in his pocket. Morgan put his gun away and lashed Fesden's ankles to the legs of the chair with some more wire. Then he lumbered over to the body on the floor, picked it up as if it had no more weight than a baby, and slung it over his shoulder.

He rapped twice on the door, waited a half minute, opened it. He turned in the doorway, showed yellow fangs in a meaningful grin, said:

"Ta-ta, feller. I'll be seein' you about midnight."

Gimpy Morgan lumbered out with that limp burden dangling over his shoulder. The door closed behind him. Wolf Fesden's lank jaws opened in a silent, sinister laugh.

THE new highway bridge glimmered pallid in the darkness, but

between its abutment and the north abutment of the railroad

bridge it was so dark that Wolf Fesden could barely make out

Gimpy Morgan's black bulk moving beside him. The only way he

could be sure they were working their way along the bank of Frog

Creek was by the greasy lapping of its water and the odor of the

oil that floated on its surface.

"How far are we going?" Gimpy growled.

"Just to' the near leg of the railroad bridge," Fesden whispered. "We don't even have to go under it." He shifted to his other shoulder the coal shovel they'd brought along from the hideaway. "But we may have to do plenty of digging. That damn pier is pretty wide."

"For what's buried there I'd dig plenty," Gimpy answered, and started going faster.

Fesden let him get ahead. High concrete loomed over them, grim against the city's glow in the overcast sky. Wolf Fesden took a good grip on the handle of the shovel, lifted it to bring the cutting edge of the scoop down on the unguarded head bobbing just in front of him—

The shovel handle wrenched out of his grip, thudded to the ground as he whirled. A low voice said:

"Not so fast, Fesden, unless you want a bullet in your belly."

Light of a hand-torch flared from behind and laid Wolf Fesden's shadow across the slender body of the man who'd said that. The shadow didn't conceal the glint of the automatic that snouted point-blank at Fesden, and there was no shadow on the man's face.

A blunt grim jaw. Eyes the gray of chilled steel. A puckered scar under black hair. The Dummy! The dick he'd stabbed to death, not three hours ago!

"No," John Porter said, "you didn't kill me. That was a stunt knife you twisted out of my hand, as I meant you to. Any pressure on its point and the blade slides back into the hilt."

"You... you," Fesden gibbered. "You—" He couldn't get any more out.

"I knew you'd holed up in one of the regular crook hide-outs," the little detective went on genially. "The cops don't know them, but we insurance dicks do, because we often swing deals to recover stolen property through their keepers. I let word get around of what we were ready to pay for a tip-off to you, which was plenty, but even that wouldn't have gotten Morgan to talk if I hadn't promised him you wouldn't be nabbed in his dump, or anywhere near it. He knew he could trust me, and he worked with me.

"It was easy to figure out that you were watching the papers for something that would let you know it was safe to go after the Rams-dell stuff, so I waited till you would find it. When I saw that you had, tonight, I let you tumble to what I was and tricked you into thinking you'd killed me. Morgan was set to do the rest when he heard me squeal— Oh, Gimpy. That was swell acting."

"Who couldn't act," Morgan said, "when he's getting fifty grand for the job?" Chuckling, he drifted off into the night.

Fesden was manacled to a steel-reinforcing rod that came out of the north abutment of the railroad bridge over Frog Creek. John Porter was digging for the casket Evar Galt had buried there four years ago. But Wolf Fesden was not watching Porter. He was staring at the pale glimmer of the new bridge over which a road ran out of Sea City and ran north, always north, till it came to Lornmere Penitentiary. Till it came to the grim, gray granite walls within which stood a heavy-built chair, a chair wired for death.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.