RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

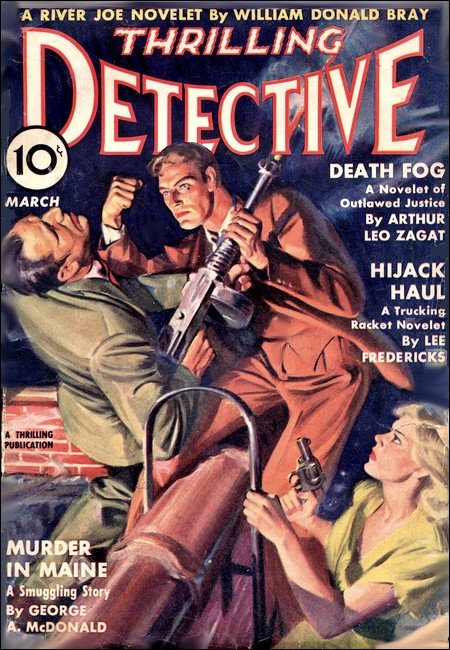

Thrilling Detective, March 1939, with "Death Fog"

Luke Cass, crippled beggar, pits himself against a fearsome fiend of crime.

A gruesome nemesis leaves his sinister brand on helpless and terrified victims!

BY night Satan's Stewpot was a place of slinking shadows, of furtive whispers. Its tawdry buildings rarely showed any light, and those in the few stores struggled with small success to penetrate the dirt-crust on their windows. The only brightness came from the saloons whose bars were always thronged.

These high spots were much alike, their air layered with blue smoke and thick with the reek of stale beer, raw alcohol, unwashed bodies and foul breaths. Small round tables studded their sawdust-mucked floors. A sodden derelict was usually asprawl on the pitted marble top of one of these, spittle drooling from his lax mouth. At another always could be found a knot of blue-jowled men, low talk seeping from the corners of their unmoving mouth's, their eyes tiny and heavy-lidded and predatory.

And somewhere in one of these lairs, or hobbling from one to another on a sidewalk scarcely wide enough for two to pass, would—in all likelihood—be Luke Cass, the beggar.

Luke Cass

Luke Cass hitched painfully along on scuffed shoes curiously malshapen. His scrawny figure was covered by a collection of grimy fabrics too ragged and ill-fitting to be called garments.

His head was thrust a little ahead of his ungainly body, eyes hidden by black goggles held to his ears with rusted wire, mouth and chin concealed by an inch-long brown stubble. His right arm was bent at a stiff angle, its fingers manipulating a sturdy and smooth cane which served as a third leg for him. His left hand protruded from its tattered sleeve, a taloned claw cupped for the pennies that only infrequently dropped into it.

The beggar was as much a part of the Stewpot's sleepless night as the pallid beams of its lamp posts, and as unregarded by its denizens. He was such an accepted fixture, they never wondered why he didn't ply his whining trade in the more prolific precincts to the south. Satan's Stewpot never questioned where he went when, with the shadows, he vanished at dawn.

Eternally vigilant as were the groups at the barroom tables lest they be overheard, their sly converse did not halt at his mumbling approach. If they stumbled over him in the street they kicked and cursed him, and forgot him in the next instant.

What he did was of no concern to them. Not even when, as now, he sidled into some pool of shadow and did not reappear.

It was with the murk of a narrow passage between two blinded, silent tenements that Luke Cass merged himself tonight. At once he was rigid, a vague blotch against one slimy brick wall, the palm of his good hand pressed hard against its ancient, crumbling mortar.

Taut as wet gut, he was evidently waiting for something or someone, and waiting despite some deadly peril the alley's Stygian depths might cloak. Evidently whatever it was he awaited would come from above, for his goggle-masked eyes peered upward, probing the black loom of a wall down which crawled, unseen, a rusted, creaking fire-escape.

Within the black gut where Luke Cass kept his furtive rendezvous was brooding silence, and darkness relieved only by a jagged-edged long bar of murky sky-glow far overhead. From the street he had left came the shuffle of ill-shod feet, coarse voices, the tire-purr of some auto hastening through these ominous purlieus, the nearest subway's rumble.

He knew that street scene too well. Out there a shrew berated her sheep-faced paramour, a bent old woman scuttled from the side door of a saloon with a bottle of gin tucked under her black shawl, hard-visaged and slit-eyed men prowled....

A gurgling scream, somewhere high up, froze the street! Something black and huge hurtled down from the rooftop Cass had been watching. It smacked the sidewalk with a sickening squash.

The thing had arms and legs. It had something that once had been a head. It squirmed silently for an instant before the life was utterly gone from it. But what was far more terrible to those few witnesses who gaped, shuddering, was that from the smashed cadaver, from its clothing burst apart by the impact and from its pulped flesh, curled tendrils of gray vapor like wisps of smoke.

Or of fog.

Fog! This was the word that gasped from knotted throats whose owners were still motionless in a long, awful moment. Not a word, a name, the way it was husked. "The Fog!" A name that was fear incarnate. "The Fog!"

This once-human splotch on the flagstones was not only a slain man to them, it was the latest manifestation of an inescapable terror that had held Satan's Stewpot in its grip for weeks. It was the latest victim of one elusive madman, intangible as that whose name he had assumed, but whose evil transcended even the evil that simmered in this hell's caldron of the city's lowest slums.

A grin, bleak and terrible, twisted Luke Cass' lips. Before there was any movement at all out in the street, he twisted, leaped with an amazing agility to the vertical bottom ladder of the fire-escape by which he had waited, and was climbing it with astounding swiftness, with astounding noiselessness.

A RUSH of feet from below reached his ears—police

whistles, raucous shouts. And abruptly shrilling through the

turmoil a cry, high-pitched, pent with grief unutterable. A

scream torn from some anguished feminine breast.

"Tim!" it wailed. "It's my Tim. I knew it. I knew The Fog would get him before he had a chance to tell...." The cry cut off suddenly.

Flashlights flickered in roof-top darkness. The sounds from the street below were muted by height; the clangor of the morgue-wagon bell, the murmur of the crowd, some policeman's gruff command.

"Get back! Get back, for gosh-sakes!"

Up here another policeman growled, "Hell, this is a lot of baloney. The skipper's nuts if he thinks the guy what done that is waitin' up here for us to come and get him."

"Yeah," his companion responded. "He knows that, too. But we got to go through the motions."

"We got to! You notice he ain't up here."

There was an undertone of uneasiness in the cop's voice. "You notice he ain't takin' no chances."

"What do you mean?" the other demanded sharply.

"You know damn' well what I mean. It's The Fog had that done. If he was up here now, waitin' for us—"

"Wish he was. I've got six slugs in this gat that's achin' to find a billet in him."

"Your six slugs and mine too wouldn't do no good against that devil. He—what's that?"

"What?"

"There," the first officer breathed. His flash beam was a long finger of light, trembling almost imperceptibly. Its broad tip touched the building's cornice, came to rest on a crumpled shape huddled against its rise.

"It—it ain't movin'."

"No." The monosyllable was followed by a breath-hiss of relief. "It ain't movin'." The beam shortened as the officers thudded heavily across the tin roof.

They stood above that which the light had found. In the vivid spotlight of their torches it was a contorted form, utterly still. The fingers of one outflung hand were clenched on the hilt of a sheath-knife, whose steel was dulled by blood almost dry. A single eye glared, unseeing, out of a brutish face. Where the other orb should have been was only a dreadful pit whose edges were jagged and torn, a pit filled by a scarlet, viscous fluid.

"It ain't The Fog," the second cop answered the unspoken question in both their minds. "It's just one of them toughs hangs around Dan Salter's joint. Name's Lou Tolan."

"Look," the other choked. He was pointing to the slain killer's forehead, to a circular stain that might have been stamped on it by the cork of an ink bottle except that it could never be washed out, and that it was the exact shade of a sunflower's petal.

"Gawd!" the other squeezed out. "The Yellow Spot! He's put it over on The Fog again."

AT this exact instant Luke Cass thrust open the vestibule door

of a tenement halfway down the block from that on whose roof the

patrolmen were making their gruesome find. He hitched painfully

down a broken stoop and hobbled toward the murmuring crowd at the

mouth of the alley.

From somewhere within the cluster came a soft sobbing. Cass managed to insinuate his malformed body among those close-pressed ones, started to inch his way through them. No one paid more attention to him than to curse him for jostling them and shove back against his shoving. Somehow, after each such brief tussle the beggar was nearer the inner rim of the throng.

He reached it, his further progress blocked by a policeman's broad back. Within the cleared space there were other cops, one resplendent with a gold shield and gold-braided cap. A goateed little man in civilian clothes held a physician's black bag in his hand and wrinkled his nose with distaste at the odors that assailed it. Two men were lifting a long wicker basket to the back of a black-sided truck. Dark droplets dripped from that basket, and there was a trail of small splotches across the sidewalk to the stain on the flagstone.

Standing above that stain was a still, slender figure, that of a girl. The gingham frock clinging to her slim-waisted body was darkly stained too, at the knees, over the soft curve of her breast, and the long, tapering fingers that pressed at her sides were reddened. Cass did not need to be told that Mary Doan had knelt beside a smashed corpse, had cradled a shattered head tight against her bosom. Her eyes, fastened on the basket sliding into the morgue-wagon, were great, dark wells of agony in a white, transparent countenance too fine of feature, too ethereal in quality, for this suburb of Hell. The police captain moved to her. "Look here, girlie," he said, some effort at gentleness in his ordinarily harsh tones. "I know it's tough to have your brother go like that, but you've got to help us get the fellow who did it. You know something about what's behind this, don't you?"

Mary gave no slightest hint that she had heard.

"It was The Fog had him thrown off the roof, wasn't it," the officer tried again. "Tim was tied up with The Fog, and you know how. Tell us what you know and you'll be helping us get the man that had your brother killed. You'll be helping us save other girls' brothers."

A shudder quivered over the girl's tight, drawn face. She wheeled.

"All right," burst from her lips. "I'll talk. Tim worked for The Fog."

Something black dropped between her and the captain, a black ball that burst open. Gray vapor spurted from it, a fog-like cloud!

Mary's mouth was open as the mist eddied on the sidewalk, but no words came from her lips. There was stark terror in her eyes.

"Who threw that?" the officer yelled. "Who? Get him, men! Get the whole damn crowd!"

HE cops plunged toward the watchers, clubs upraised, gnarled fingers reaching. But the denizens of Satan's Stewpot were too quick for them. The throng broke, became a fleeing, caterwauling scurry of forms through the dimness. Black alleys swallowed them, gaping cellar doorways engulfed them.

Momentarily the sidewalk was deserted, leaving only the black-sided truck against the curb, Mary Doan, one small fist clenched against white lips, and Luke Cass, whom even the cops ignored.

The beggar jerked into awkward motion. Perhaps it was because he slipped on that which stained the flagstones that he brushed close to the girl as he passed her and limped away.

The baffled policemen returned. The captain made another effort to question the sister of the murdered man, but was met only by close-lipped silence, by eyes in which fear crawled.

"Listen, you," he grunted. "I've got a damned good mind to run you in. I—"

"Captain!" a cop interrupted. "Finnerty's yelling down from the roof. He wants us to come up there."

"Maybe they've got..."

Mary Doan heard no more. The police were pounding away from her. The morgue-wagon was rolling away. And there was something crisp in the pocket of her frock. It was only a piece of paper, but there was writing on it.

Tim would want you to finish what he started. What the cops can't do, I can. Be at the northeast corner of Twenty-first and Boulevard at ten tomorrow. Get into the Buick sedan that will stop opposite you, and you'll have your chance.

There was no signature. But underneath the final sentence there was a round stain. The stain was yellow as a lemon's skin.

Mary Doan looked down at the sidewalk. Wisps of gray vapor still clung to the flagstones from that warning black ball. But beside them was a dark patch of clotted blood.

The girl's fingers tore the paper across and across, till it was in flakes scarcely bigger than the head of a pin. As she walked slowly away she let those flakes sift from her hand into the gutter slime.

MEANTIME Luke Cass was drifting toward the waterfront. When

anyone was in sight his pace was a painful hobble. When some

smashed lamp, some alley into which he skulked, afforded him the

cloak of impenetrable night it was a swift, soundless run. He

seemed to be in the grip of some dreadful urgency, seemed bent on

some mission with which the events just related had

interfered.

He reached the edge of Satan's Stewpot at last. From the covert of a high truck-loading platform he peered out at the wide, cobbled expanse of the thoroughfare along the wharves that was a hurly-burly by day, but now was dark and lifeless.

Only in that first instant! A small leaf in the high wall of a pier door came open. Three shadowy figures issued from it, flitted across the street, vanished in the shadows before Cass could get moving.

The sound from his throat was a muttered oath. He moved now, flinging himself across the cobbles to the small door the prowlers had left open. He was through it; the door closed behind him. There was light abruptly, a thin pencil beam of light that flicked through the blackness from a slender cylinder in his fingers.

The space was closed in by a board partition that squared it off, but there was no ceiling, only, far above, the trussed roof-girders of the pier. There was a wicket window in the partition. Beneath it there was a small safe.

The door of the safe hung open. There was no evidence of it having been forced open, but it was empty. A few papers had spilled out of it onto the floor.

Cass' light moved a little, found something else on the floor. Something lay outstretched, in the form of a cross. A man, jaw stubbled by gray grist, lay staring with luster-less eyes shaded by shaggy white brows. The man's arms were out-flung, level with his shoulders. They were held that way by spikes driven through the palms of the hands into the rough boards below. There were spikes through his ankles, holding his legs stiffly outstretched.

A watchman's clock lay in a pool of blood on the floor beside its crucified owner. The blood had poured from his throat that was slashed across so that a second mouth gaped there, the severed gristle of his windpipe making a blue, tubular tongue for it. But that had not been done till the torture of his crucifixion had wrung from the old man the combination of the safe he would never guard again.

Stray gray tendrils, like fog, still curled up from the corpse.

LUKE CASS' flashlight clicked off. Street glow outlined the

oblong of an opening door for an instant, was blotched by a

black, malformed silhouette.

The beggar darted across the waterfront street, plunged once more into the noisome dimness of Satan's Stewpot. Once more he seemed driven by some dreadful urgency, by some obscure purpose to a definite objective.

It was another alley he sought, another lightless gut between two sordid tenements like that in which he had awaited a rendezvous when murder had broken. He attained it at last, dived deep into it. Abruptly he halted. His lowered hand fingered greasy-wet brick, was rasped by the horizontal sill of a basement window, drifted still lower to find grit-filmed glass and wood softened by rot.

There were small sounds now, the scrape of a metal blade, an almost inaudible splintering, a slither of fabric against wood. And there was no longer a furtive figure in the alley.

A dot of light, the end of his pencil-thin beam, danced in cellar gloom. It flicked over a pile of broken lumber, touched foundation stones on which the whitewash was long overlaid by gray grime, found and momentarily held on a railless flight of worn wooden steps, then vanished. After a moment the steps creaked slightly under his cautious weight.

Luke Cass reached the top of the ladder-like stairs. Over his head he felt the rough under-surface of a trapdoor. He palmed it, listened intently.

A rumble of voices was barely perceptible. The beggar's hand pressed upward against the wood. The door was ponderous, but there was unexpected strength in the slow, steady thrust against it. It lifted so slowly that one might have counted fifty before, overhead, a yellow filament threaded the dark to show that its edge had risen above the floor.

WITH the light, words came through the crack "...keeping

Con." The trapdoor's slow movement stopped. "He ought to be here

now. Maybe he got nabbed."

"That would be okay by me if he wasn't carryin' the loot," another voice grunted. "Me, I didn't like the idea of splittin' up after we cracked the pier crib."

"That was the way the orders was given us, and that was the way it had to be done. Con won't run out on us, even if he has got five grand in his kick."

"Maybe not. But he'd damn soon squeal to save himself from the hot squat if he's pinched."

"Not much, he wouldn't," Cass heard. "He'd wait for Stryker to spring him."

"Damn Stryker! I'm gettin' sick of that lousy mouthpiece! Maybe the other lawyers that play with us is gettin' picked off by the law, and maybe Stryker's got an in so he won't be. But he cuts in on every job, and then if he's got to go to bat for us, he cops our divvy, too. Ain't that a helluva note? It's us turns off the lays, even if he does cook 'em up and—"

"Cripes!" the other cut in. "You know well's I do that rat ain't the one does that."

"The hell I do! I'm not goin' for that bunk no more about The Fog. There ain't no such guy. He's just a boogey Stryker made up to—"

"Shut up!" It was a gasp of pure terror. "If The Fog's listenin'—"

"How could he be? We're alone."

"He could be in this room right now and we wouldn't see him." The voice was a husk forced through a clamped larynx. "He could be miles away and still hear every word we say. How d'you think he knew Tim Doan was fixed to stool on him? Tim didn't tell no one but his sister, and she sure didn't spill it."

"So Stryker says. Maybe he wasn't gonna rat at all. Maybe he was bumped just to throw the fear of The Fog into us."

"Yeah? You heard what his sister said just before she was warned. Ain't that enough for you? Take it from me, you don't know where The Fog is and you don't know who he is, but he's the devil himself, or his brother."

"Well, I—" began the other.

"You'll button your mouth tight if you don't want to be picked up some night, stiff as a board with The Fog's smoke on you. You'll keep mum and take yer orders, and listen, you ape. This ain't no time to be runnin' out on The Fog even if he'd let you. Stryker tipped me this even-in' the thing we been waitin' for is about ready to spring—that big job that'll set this town on its ears. Do you want to be in on that, or would you rather be pushin' up daisies?"

A chair scraped, as though someone were hunching it closer.

"The big job," the malcontent whispered. "What is it?"

"I dunno. Stryker wouldn't crack, but his face got gray-like when I asked him, and there was green around his mouth. He was scared even thinkin' about it. And anything that scares that baby...."

There was a moment of silence, as the speaker's voice trailed off. Then the one called Lou was talking again, the fear in his tones almost obliterated by lip-licking greed.

"Yeah. If we keep stringin' along with The Fog we'll have more cush in our kicks than a cokie thinks he's got after a double snifter. There ain't nobody can stop that moke, whoever he is."

"No one? How about—" The heretic stopped, as though reluctant, or afraid, to utter the name in his mind.

"How about who?" the other growled. "Spit it out."

"The Yellow Spot, that's who. That's the guy can beat The Fog, and he knows it. Why else was the word passed that the bloke who bumps him, and proves it, gets ten grand? He—"

The light-thread in the cellar ceiling was blotted out, the overheard voice cut off to an unintelligible rumble, as Luke Cass lowered the trap without sound. Now he crouched, rigid, atop his perch.

From somewhere in the basement had come the scrape of stone on stone. As the beggar listened, the slight sound came again. An oblong of paleness relieved the intense gloom. It was blotched by a black, squat silhouette.

Stone scraped once more, and then the blackness was solid. But there was sound within it now, the hiss of breath, the thump of unhurried footfalls. Those sounds were between the eavesdropping beggar and the window he had forced, between him and the door by which the other had entered. Escape, unseen, was impossible.

The footfalls came on towards the stairs. Abruptly their rhythm was broken by the thud of a shoe against some obstacle, the silence by a ripped oath. An instant's hush ended in the scratch of a struck match.

A flame blossomed within a yard of the stair foot, and the darkness fled, unveiling a bestial face. The face lifted to the steps, twisted with surprise, the shaggy-eaved eyes dilating, the thick lips opening.

Cass swooped from his aerie, his cane stiffly downheld, ferrule first, straight for the intruder. A shrill yell met him—was cut off.

The match arced away and went out as a soft, sickening thud sounded against the floor. For a moment something gurgled in the dark, and something threshed. A rush of feet hammered overhead.

UKE CASS leaped for the cellar wall. He hooked the crook of his cane over the window's high sill. As though propelled by some gigantic spring he was up the wall and out through the aperture like an agile rodent.

The trapdoor slammed open. Two men, one burly, the other a weazened runt, hurled themselves down the stairs.

They found only the twisted form the beggar had left behind, gruesome in the shaft of light now streaming down upon it, making a macabre stage of that fetid basement.

The body was prostrate and utterly still. Its throat was gashed open, as a watchman's had been not long before, but this was a jagged wound ripped into flesh by the sharpened steel ferrule of a beggars cane. And on the corrugated brow of the twisted corpse there gleamed...

"The Yellow Spot," the bigger man jabbered, his utterance thick because his lips were bloodless and suddenly numb. "Oh Gawd! The Yellow Spot!"

The sky was paling into the chill grayness of the false dawn. On the breast of the river, sluggish between ebb and flow of the tide, swirled mist-wraiths like phantoms out of the sleeping city's nightmares. But Luke Cass' night was not yet ended.

At the southward edge of Satan's Stewpot, where the avenues become wide and straight, was Gratton Street. Here the ivy had withered from the pitted granite façades of once stately homes now overhung with the tawdry signs of small, starveling businesses.

AMONG these houses there were a few that through the

restriction of some testament or the nostalgia of some oldster

for the vanished, golden days, remained dwellings.

In the areaway beside one of these, the beggar crouched. For a long minute his hidden eyes peered out into the dead vacant street. They came back slowly, noting the steel-shuttered windows of the first floor. They shifted to those of the second story, so high up in the smooth wall that only a fly might hope to reach them.

Luke Cass did a curious thing. He took his thick cane in his grimy hands, held it horizontally before him, twisted at the handle. The crook turned, came off.

The cane was revealed as a hollow tube from which Cass now drew length after length of steel rods, exceedingly slender, exceedingly strong.

He replaced the cane's handle, used it to hang the amazing stick on the rope he used for a belt. Then he screwed the rods together, length by length, testing each joint swiftly but meticulously. When he finished he had a single length of slim steel that measured almost thirteen feet.

From somewhere in his rags he produced a sharp-pointed steel hook, screwed it to one end of the contrivance he had put together. He slid the device down the areaway till he could grip the other end. Then he was lifting the bending steel into the air.

It went up, scraping faintly against the wall, till it was vertical. There was a snick as the hook bit home on a wooden window-sill above. Cass leaned his weight on the end below, testing the security of that bite.

It held. The beggar put his apparently malformed feet against the wall, got a firm grip on the rod. He lifted. Leaning outward from it, he was literally walking up that wall which afforded neither hand nor foothold. Foot over foot on the brick, hand over hand on the joints of the rod, he was scaling it.

In a moment there was no one in the areaway, no one on its bordering wall against which the thin, long rod was all but invisible. But on the wide sill of a second-story window lumped a dark, ungainly shape.

The window was half-open for the night, the drapes beyond its deep embrasure drawn aside to admit the air. To admit sight and hearing, too, of the spy crouched outside.

The growing dawn, pressing into the room beyond, was dimmed by its lofty space. There was still light enough, however, to make out the head indented in the pillow of the four-poster bed.

It was quite bald, this head, and hairless except for stiff, stubbled brows. The lids were bluish and so flat one knew the hidden eyes were deeply sunken. The nose was thin-nostrilled, sensitive as the thinly chiseled mouth. The chin just hinted at weakness. Into the sere skin of that face lines were deeply etched, not only by the years but by suffering and remorse, and by an abiding fear.

"Stryker!"

The man was asleep and he was alone, but that voice was in his bedroom, hollow, resonant.

"Stryker!"

"Yes. Yes, Master." The eyelids that had been closed were wide open now; Curt Stryker was completely awake at once. He stared at the blank, lofty ceiling, gripping the coverlet as though for assurance that the voice was reality and not a dream, though he had heard it often before. Terribly often. "Yes, I am listening."

"Listen carefully." Some quality in the tones robbed them of direction, so that where they came from was impossible to determine. "There is something that must be done at once. You will find the instructions in the usual place."

"I understand."

"You will find there also the final orders for the enterprise toward which you have been building our forces. As soon as the other has been attended to, you will proceed to distribute detailed instructions to all our men. You must act quickly, for you have only twelve hours to do what is needed."

"Twelve!" Stryker gasped. "So soon, then?"

"Yes. Our tools are sufficiently tested, the inept and the untrustworthy discarded. This morning the last threat to our success will be removed, and we strike tonight at midnight. That is all."

"Master!" The lawyer shoved thin elbows hard against the mattress, shoved himself up to a sitting posture. "Wait!" The blanket fell from his bowed shoulders, his pinched chest. "I've obeyed you, served you faithfully. But this terrible—Master! Do you hear me?"

There was no response.

Stryker pulled in a long, quivering breath. He was out of the bed, was tottering across the floor to the window.

Never before had he dared to do this, never before dared even this much. But this time his need was so great. He reached the window, leaned out over its sill, a cry trembling on his white lips.

There was no one to call to. There was only the vacant areaway and the street beyond, flushed with the lurid glow of sunrise but empty of life.

Not quite empty. A solitary figure limped across the end of the alley. But this could not be The Fog. Not this beggar hobbling along on scuffed, misshapen shoes, his halting gait eked out by a thick, scarred cane; this cripple whose black goggles stamped him as almost blind.

CURT STRYKER turned back into his bedroom, his face a gray

mask. His hand made a small gesture of despair as he shuffled

across the chamber to a door behind the bed, a door that led into

his office.

From the twisted alley's of Satan's Stewpot daylight had driven its denizens to their foul crannies, so there was no one to see Luke Cass as he hurried through them, back to the piers. The little knot of policemen clustered at a small door in the larger one of a great wharf building, their faces haggard with what they beheld within, paid scant attention to him as he scuttled across the cobbled street and ducked into a space between that pier and the next.

He was like a huge gray crab clambering along the piles at whose base the water lapped. He vanished between two of them, crawling under the floor of the wharf.

After an interval, a speedboat roared south up the river. It had come unseen from beneath the pier where Luke Cass had disappeared. But the man who stood at its wheel was tall and straight and slender, his frame lithe, his young face bronzed, blond hair streaming back from a high, thoughtful forehead. Never, by the wildest imagining, could he be linked with the beggar called Cass.

The landing raft to which that speedboat veered was the appurtenance of one of those huge cooperative apartment houses where only the very wealthy live. Its uniformed attendant tipped his visored cap with unusual deference.

"Good morning, Mr. Foster," he said.

"It's a very good morning, James." Lloyd Foster's flashing smile was heart warming. "The fishing was the best I've had yet. But I'm certainly ready for a cold shower now."

He hurried into the house.

The glare of the morning sun was tempered by the luxurious drapes smothering tall windows whose thick plate-glass muffled the avenue's traffic roar to a discreet murmur. In the Federal Club's breakfast room liveried waiters moved noiselessly, deftly serving the men at the tables, the old men who were smug with the consciousness of their membership's high privilege.

They stirred with vague resentment when the velvet portières at the entrance parted and Lloyd Foster appeared between them, scanning the room with a faintly mocking smile.

He was a member, by right of birth. A Foster was one of the founders of the Federal, to have a Foster on its rolls was one of the Club's unbreakable traditions. He was, beyond doubt, a gentleman. It was his virility that irked the old men; the sinewy strength his impeccably correct garb could not conceal, the disquieting frankness of his clear, level gaze. He had so much they never had had, or once having, had lost. There was a general sigh of unacknowledged relief when, the brief scrutiny ended, Foster turned and moved out of their sight.

Alton Flinder dabbed at his mustache with his napkin, threw it on the table and rose. He moved toward the door with a grave dignity, his well-set-up figure unbowed by age, his luxuriant white mane a veritable crown for his leonine head.

One of the men at a table for two leaned across it.

"Flinder's troubles seem to be over," he murmured to his companion. "One of the house committee told me last night that he's up to date in his dues and charges at last."

"It's a disgrace that they ever posted him," his vis-a-vis growled. "The oldest living Federalist and head of the city's finest family. The Club's his whole life. I think he'd drop dead if he were ever suspended for arrears."

"They say he came to the end of his family fortune some time ago, except for some real estate that isn't salable. But they must have been wrong."

N the marbled lobby Flinder looked about him, as puzzled as his dignity would permit. A gray-haired flunky came up to him.

"Mr. Foster is in the House Committee room, sir," the servant murmured.

"Thank you, Charles," Flinder nodded. "The young pup wants my advice about a connection with a law firm," he remarked gratuitously. "It's about time he quit kicking around and went to work."

"Yes, sir. It's too bad his father passed away so long before he was admitted to the bar, or he'd have come into a marvelous practice. I remember as if it was yesterday when Mr. James—"

"Yes. Yes, indeed," Flinder smiled icily and departed toward the indicated room.

Lloyd Foster rose as he entered.

"If you'll throw the latch, sir, no one can interrupt or overhear us."

The older man obeyed the suggestion, but his lips pursed.

"What is all this secrecy?" he demanded, frowning. "First you phone me for an appointment at the unearthly hour of eight-thirty, then you want this door locked." He pulled back the chairman's high-backed chair, sank carefully into it. "And all this after you have avoided me for weeks. I am seriously perturbed, young man. As your father's friend, I expected to be your counselor and guide."

Foster grinned disarmingly. "I'm sorry sir. I've been so busy."

"With your polo and your speedboat," the old man snorted.

"No. With something else a great deal more important. You undoubtedly know that seven criminal lawyers whose activities were more criminal than legal have recently been disbarred. That was on anonymous evidence supplied to the Grievance Committee. It was I, sir, who unearthed that evidence."

Flinder blinked. "You! I don't understand."

"I'll tell you about it some other time." Foster glanced at his wrist watch. "I have an important appointment at ten. But I've got to say this much. I've got on the track of something a devil of a lot bigger than the criminal lawyer racket, though it's tied up with it—something almost impossible to believe. There's a man behind it who's hell on wheels, but I'm going to stop him or be stopped."

He paused for a moment, the smile still on his face, but the blunt line of his jaw curiously hard, his blue eyes icy.

"You can help me, sir," he went on. "There's a lawyer named Stryker about whom I want all the information I can get. I have a hazy memory of hearing Dad speak of him as a member of this club. If he was, you would know him and be able to tell me about him."

"Stryker, did you say? Curt Stryker? The name seems quite familiar. Oh, yes. I have it now." And Flinder's brow darkened.

"Curt Stryker is the lamentable last survivor of one of the city's first families. He was, in fact, at one time a member of this club. He inherited a depleted fortune, lost what was left speculating in an effort to recoup, and in order to maintain his scale of living became involved in a serious breach of professional ethics.

"Because a Stryker and a Federalist could not be permitted to be disbarred, we saved him from that disgrace, but he was requested to resign. Since then—no one here has had any interest in following his career."

"Just what was the nature of his —er—breach of ethics?"

"Sir!" Flinder rose, his cheeks puffed, his mane bristling with outrage. "You forget that the details of the resignation of a member from the Federal Club are never discussed by gentlemen. I am afraid, sir, that I may have already said too much, and lest I be tempted to further indiscretion I bid you good-day."

"Now, Mr. Flinder—" Foster began, and found that he was talking to a back that was strutting away from him. By the time he reached the door and the lobby outside, Alton Flinder was retreating in good order to the lounge.

"I hope that your talk with Mr. Flinder was of some material aid to you, sir," the voice of Charles murmured in the young man's ear.

"Enough to pay for listening to the old windbag, eh?" Foster grinned irreverently. "Well, hardly." A thought seemed to strike him. "Say, Charles, you've been around here since the 'El' was knee-high to a grasshopper. Remember a member called Stryker who was bounced out on his ear?"

"Of course, sir. Mr. Curt Stryker."

"I have just been informed that gentlemen do not discuss the details of a Federalist's descending to the status of an ordinary mortal. Perhaps, since neither of us is a gentleman, you can tell me something about it?"

"I can tell you all about it, sir." Charles looked injured at having his encyclopedic acquaintance with the affairs of the club and its members questioned, and Foster looked exceedingly interested.

"Proceed, Charles," he said. "Proceed. You have before you an audience such as has been the dream of tale-tellers and gossips from the dawn of time. But make it snappy. I've got to be at Twenty-first and Boulevard at ten sharp."

AT nine-forty Lloyd Foster bounded down the wide brownstone

steps of the Federal Club and into his dark blue sedan. The

starter whirred, the motor roared into life. The car sped

north.

Foster smiled to himself grimly. "With that," he whispered, "and what I'll get out of the girl, I'll smash The Fog!"

At nine fifty-five the sedan was panting at Twenty-fifth Street and Boulevard, held there by a red light while its driver was glancing anxiously at his watch. At nine fifty-nine it was caught in a jam of traffic at the southeast corner of Twenty-first Street, caught long enough for the red light there to turn against it.

Foster bit his lip, peered through the stream of released trucks and cars at the opposite corner. There were two white spots alongside his nostrils and a visible pulse throbbed in his temple. The subway kiosk there disgorged a glut of passengers. They swirled away. Mary Doan, pathetic in a sleazy black dress, her face sheet-white and haggard, was standing at the curb, looking anxiously about.

Lloyd Foster's toe was on the gas pedal. The red light went out, the yellow showed. A man came alongside of the girl, stopped close to her, the corner of his tight mouth twitching as if he were saying a low word. A black limousine darted around the corner, hid them from sight.

The green came on, but for an instant a huge van blocked off Foster's car. It moved out of the way, and the blue sedan was fairly spurting across the intersection. But Mary Doan was gone from the corner!

Foster ripped out an oath, heeled his accelerator pedal hard. The black limousine was at mid-block, roaring away. The light at Twentieth was green when it reached there, was still green when the sedan, fifty feet behind, reached there.

A police whistle shrilled. Foster yelled something at the traffic cop, twisted to avoid running him down. A stone hurled from nowhere hurtled through Foster's open window, caught him squarely on the forehead. His numbed hands could not twist the wheel, the sedan catapulted into a towering lamp post.

The impact crashed blackness into Lloyd Foster's skull. The traffic cop, springing to that terrible mess of crushed steel heard a mumble of words meaningless to him.

"The Fog," it sounded like. "The Fog's got her."

"THE Fog," Lloyd Foster heard himself mumble, "has got me licked."

The red hot pain in his shoulder and chest was duller now, a throbbing ache rather than searing pain. He must have passed out for a while. He was in bed. But not his own bed. Instead of silk, some harsh fabric lay against his skin, and the pillowcase against his cheek was not fine linen. His eyes opened.

Yellow light lay against an enameled wall, its corners curiously rounded. He was far higher from the floor than any normal bed should stand. The floor was concrete, painted a sickly blue-gray, and there was a smell of medicines in his nostrils, pungent, unpleasant.

"Good evening," a feminine voice said, mechanically cheerful. A face swam into range of Foster's vision, a pointed, sharp face topped by a nurse's cap. "How do you feel? Not too bad, I hope. Doctor Ball said you'd lost a lot of blood."

This was a hospital! All that had happened flashed back to memory. "Where is this?" Foster asked quickly.

"The Riverview Hospital, Mr. Foster. But you must be quiet."

The Riverview. That was one bit of luck. But by the artificial light this must be night. Good Lord!

"What time is it?" was his next query.

"Ten-fifteen."

TEN-FIFTEEN! And it was at ten in the morning that Mary Doan

had been snatched. What had happened to her in the twelve hours?

Had The Fog...?

"Get my clothes." The patient pushed himself up to a sitting posture. "Hurry. I've got to get out of here."

Maybe for some reason The Fog hadn't killed her. Pray that it was so. No, don't pray. Act! Find her. But how?

"I can't give you your clothes. They're locked up in the patient's storeroom. Lie down, Mr. Foster. Please lie down or I'll have to call the superintendent," said the alarmed nurse.

"Call him. I know he can't keep me here against my will. Call him. Tell him I want to sign a release and get out of here."

Even that would take time, and there was so little time to spare. Where was Mary to be found? And there was that other thing—that which was to happen at midnight—to be stopped. At midnight, and this was already after ten. Impossible. But he'd already accomplished the impossible more than once. Stryker was the key to both, the only key.

"Go call the superintendent. Please." Foster flashed his smile on the nurse, the engaging smile no woman had been able to resist. "See," he said, lowering himself to the pillow. "I'm behaving myself. Please go call the super."

"Well..." she yielded. She turned, went out of the room. With the closing click of the door Foster was out of bed, was dashing across to the window, the short hospital nightshirt flapping against his thighs.

The Riverview's private pavilion lay, he knew, along the waterfront. If only—he reached the window, leaned out. Yes. This was the river side of the building, and this room was only on the second story. There was a wide, cobbled yard below, and beyond it the dark of the tide.

Foster's one bare leg went over the sill, then the other. He twisted lithely, was hanging by his good arm from the sill, was groping with the other and his toes for a hold on the hospital's wall.

He found it, a deeply chiseled groove between the courses of the great granite blocks.

He was going down, his face tight-drawn with the pain in his breast. There was a warm trickle beneath the bandages. His wound had reopened, and he was bleeding. It didn't matter. Nothing mattered except Mary and stopping The Fog.

He attained the yard and darted across it, the stones bruising his soles, to the river edge. His luck held. There was an outboard-motored rowboat tied to a ring in the retaining wall, some interne's plaything. Now, if only this bleeding didn't weaken him too much.

The fetid dark of the river lay, heavily over one of the great piers just west of Satan's Stewpot. Out in the blackness there was the thrrr of an outboard motor. It slowed to a put-put-put, died away.

The water lapped greasily against the piles supporting the pier. There was a thud, down there. A blurred shape that had somewhat the size and shape of a boat rubbed against the piles, found an opening and disappeared within them. After a moment there was a faint luminosity in the water, as though somewhere beneath the pier floor a light had been turned on. In perhaps five minutes it blanked out, but shortly afterward a shadowy figure might have been seen to appear, seemingly from nowhere, in the cobbled waterfront street at the pier's land end.

ATAN'S STEWPOT bubbled that night like an evil brew. There was a strange hush in its saloons. At their tables no groups were gathered in tight-lipped conference. At the most there would be two, their talk muttered and intent.

More often than not one of the two was Curt Stryker. Wizened but dapper, his bald head covered with a square-sided, flat-topped gray derby, his thin neck swathed in a white ascot, the lawyer seemed almost a phantom out of the past. In his face there was no more expression than on the walnut's wrinkled shell it resembled, except that his eyes, points of blue steel, bored deep into the eyes of his hearer.

Those eyes would flick, briefly, at anyone's approach, and at once there would be a dead silence until the intruder was beyond possible ear-shot.

Whatever business had brought Curt Stryker to Satan's Stewpot, it was accomplished shortly after ten o'clock. By ten forty-five he had returned to his house of faded elegance on Gratton Street, the home where he lived alone and maintained his office, unattended save for the ministrations of a crone who came in by the day to make his bed, sweep his floors, and prepare his frugal meals. This solitary existence had been going on for more years than either of them cared to recall.

BIDDY MCCARTHY had been gone for hours, of course, when

Stryker reached the house. The place itself was dreadfully,

almost ominously, silent, its fortress-thick walls shutting out

the never-sleeping murmur of the city.

Stryker sighed, mounting the stairs, and his mask of imperturbability dropped from him. He was suddenly just a tired old man, a man chained to living against his will. He reached his office door, entered, clicked on the light by a switch just within its massive frame.

He froze, became motionless, his thin nostrils flaring. His hand, still on the switch, began trembling.

Always he entered here thus, always with the terror tearing at him that someone had been here in his absence, had unearthed his secret.

His fearful look darted about the spacious chamber, to the tall, arched window like that in his bedchamber next door, to the center of the room where a massive table was strewn with yellowed documents and dog-eared law-books, to the great roll-top desk whose high back rather oddly faced the room.

Nothing was disturbed, nothing displaced by so much as a hair's breadth from its accustomed position. The gray film that had spread over the lawyer's face receded.

But he seemed still unsatisfied. His fingers dropped from the switch. He went across the floor to the desk. He passed its end, went around it and was screened from the room. But he did not turn to the desk, did not unlock its corrugated shutter and roll it back, did not touch the drawers. He went on, to the wall beyond that was hidden from observation by the desk's high bulk.

There was a faded design of small conventional figures on the wall paper. The old man's palsied fingers touched one, another, then a third of these. Something rasped in the floor beneath his feet. He knelt there, still in the shadow of the desk, curiously meticulous as to on which boards, uncarpeted here, he placed his knees. His palm pressed down on the floor between them.

A foot-square section of the wood moved downward under that pressure. The lawyer pushed sideward then and the panel whose jointures had previously been invisible slid under the floor.

Revealed was a cubic receptacle, its sides of rusted iron anciently wrought. This was an ancient house and it held secrets not all of which Curt Stryker had unearthed.

He peered down into the metal recess. A sheaf of papers lay within. His veined hand reached down, slowly, tentatively, fingers close together. Their tips lowered beneath the level of the floor, stopped as they were brushed by a feathery touch.

Breath hissed in relief from between the old man's teeth. The network of fine filaments, invisible in the dimness, that stretched across this cache was intact. No one had broken these delicate seals, no one had read the papers they guarded.

No one but himself. He had read them. He had obeyed the instructions inscribed on them. Curt Stryker recalled what those instructions were....

The cubicle was closed again at last, and Curt Stryker was on his feet. He was pacing the floor, unconsciousness no longer needed to reveal the agony in his face. It was all too evident now in the writhing of small muscles under the skin, in lips so tight-pressed they were a narrow ghastly line, in the gleam of tortured eyes.

"That girl—sweet, innocent.... I gave the orders. I!" His agony spoke aloud. "And the rest—the horror at midnight."

He glanced at a clock on the wall. "Not quite eleven yet. If only I had the courage! If for once, once only in my life, I could play the man...."

And then fear groaned, mocked him. "But how fight a phantom, a voice?" He reached the window, stared out of it and down, as though he could see through the sidewalk, through the earth beneath, into the steel-lined tube from which came the faint rumble of a subway train.

"Hundreds of people," Curt Stryker whispered huskily, and shuddered. "Slaughtered—"

Sound stopped him, the distant, deep-toned bong of a tower-clock to the north. Bong. As if from some brazen gong of doom the sound welled to him out of the night. Bong. He was counting the slow strokes; four, five, six. If he thought about them he would not think about that other thing... seven, eight, nine... that dreadful thing... ten... his own weakness had made possible....

Bong. The eleventh stroke hammered on his brain. There were no more. Eleven—that was all. But when that clock again struck the hour....

"Eleven o'clock," Stryker whispered. "They're starting out, from Satan's Stewpot. Too late to stop them. Everlastingly too late! The devil's mess I've brewed over the fires of avarice and terror has boiled over at last ... oh, God!"

Too late! With this realization, strength left the tortured man. His knees were buckling under him. By a tremendous effort he shoved himself around, staggered toward a chair near the bedroom door, and halted.

That door was opening!

SLOWLY, without a sound, that door was opening, and Curt

Stryker could not move. He remained there in the center of the

room, held by a nightmare paralysis while the dark portal came

inward, slowly but inexorably, till at last it was fully open and

his bulging, terrified eyes beheld the apparition.

The figure of a beggar unshapely in moldering rags, a beggar masked by huge black goggles and an inch-long brown stubble of a beard stood there. A beggar who leaned heavily on his thick, crook-handled staff.

It was Luke Cass. But was it? There was something different, something grisly and appalling about this inexplicable apparition.

"Who—" Curt Stryker gasped. "Who are you? What are you?"

The strange being did not answer. Not in words, but his arm lifted, his right arm that held the cane, moved sideways so that the end of the staff's handle struck the wall beside the door, and dropped again. Stryker's eyes followed.

On the faded paper had appeared a circular stain yellow as brimstone from the uttermost depths of Hell! And a scream stirred in Curt Stryker's breast, but his throat clamped on it and would not let it pass. The scream passed away and words rasped out instead:

"What do you want?"

Cass had a voice now, a voice that was harsh and dreadful.

"What have you done with Mary Doan?" it demanded.

"I don't know." The old man's hands went to his scrawny neck. "I—I dare not tell you."

"You dare not refuse. I am stronger than The Fog who first forced you to obedience by fear of punishment for your long-ago crime which was concealed by men who shrank from the disgrace upon their caste the publication of that crime would have made. The Fog holds you now by terror of punishment for the newer crimes he has compelled you to commit by that threat.

"But I know! I am the Yellow Spot. The law you know how to defeat with your tricks, but I am Justice outside the Law. My punishment is merciless and swift. Choose, but choose quickly. Speak, or—" and the cane lifted with a slow threat that was the more awful because its tenor was unknown—"die!"

"Don't!" The old man's voice was a shrill scream in that throbbing room. "Don't! I'll tell. Mary Doan is—"

An orange streak of light flashed across the room! Stryker's face became a splash of red, and he toppled. The wall opposite the bedroom door gaped. A filmy swirl, gray as fog, issued out of it, became a tall flutter of gray and misty draperies in the room. A gray-gloved hand jutted forth. The revolver it held, thick-snouted with a silencer, swung to bear point-blank on Luke Cass.

The beggar's arm swept up and back, launched his thick cane like a javelin, straight for the intruder. It crossed the flash of the revolver's missile, sharp ferrule first, and lanced arrow-like into the Fog's gray robes. The deadly criminal uttered a muffled cry and went down.

The beggar's arm swept up and back, launched his thick cane like a javelin.

But Cass was down, too, on hands and knees in the doorway. Blood was welling over his grimed forehead, welling down over his eyes. His head rolled on its shoulders, steadied. He managed to get a hand up to that blinding, crimson veil, somehow rubbed it from his sight.

HE saw the forms of these two men he had fought so long and so

bitterly. Curt Stryker was contorted on the floor, his lower jaw

shattered by The Fog's bullet. He saw the gray, crumpled mass of

the demon who had launched that bullet, his own strange weapon

projecting from it. The Yellow Spot groaned.

With one dead, the other dying and speechless, Mary Doan's doom was sealed. The secret of the projected crime at midnight was safe from him. He had failed.

"The Fog," Cass muttered thickly. "At least, I'll know who he was."

He began crawling painfully across the floor. It heaved beneath him like a ship's deck in a heavy sea. He was weak, so weak.

Bong. From somewhere came the muffled stroke of a tower-clock, marking the half-hour.

"Eleven-thirty," the crawling beggar said, more loudly. "There might still be time if only I knew—"

He broke off at the sound of a bubbling gurgle. His head twisted aside as he stared at Curt Stryker. Like a scotched snake that refused to die, the renegade lawyer was crawling, squirming incredibly over the Kashan rug! The rug's ruby color was darker and moistly glistening where he passed, making a trail toward the gloomy roll-top desk that dominated the shambles of the room.

Cass was very still for a moment, marveling at the grisly sort of strength which animated the gory form that should be a corpse, wondering whence it came. What sudden bursting of long-chafing chains, what surge of long-stilled conscience energized Stryker? For Luke Cass knew, suddenly and certainly, why Curt Stryker staved off death and what his purpose was, but he could not see how it would be achieved.

He turned to follow that grisly figure behind the desk. The first shock of his own wound was by this time gone, and though still weak he managed to gain his feet in time to aid Stryker when the old man reached the wall at last and showed by his feeble gestures that he wanted to be lifted erect against it.

The fingers that sought and found three figures in the faded design on that wall left red smears upon it. Then Stryker was down again, with infinite effort shifting his knees till they rested on two certain boards of the ancient flooring, was pressing a crimsoned hand on the wood between, all the while gurgling horribly.

A foot-square panel of that wood yielded to his pressure, shifted a little to the side—and the man that shifted it collapsed upon it, no longer a man but a corpse.

LUKE CASS half-ran, half-tumbled down the stoop of the house

on Gratton Street and reeled across the sidewalk. A nighthawk

taxi wheeled into the curb.

The cabbie stared at this scarecrow that hailed him. He saw a beggar whose face was a scarlet mask, the cold sweat of pain mingled with the gore.

"Drive me to Tenth and Boulevard," Cass croaked. "Fast as you can go." Before the cabby could refuse, he tore a bill in half, thrust one fragment into the driver's reluctant fingers. "The rest is yours if you get there before midnight. That's ten minutes."

The taxi man stared at the numerals, 20, on the half-bill.

"Mister," he said, "pile in. I'd drive you to hell and back in ten minutes for that."

UNCHED in the back of the rocking car, Luke Cass could visualize the scene toward which it sped, the details of the picture etched on a screen in his pounding brain. He had read the papers in Stryker's private cache with desperate speed, but he had not missed a word.

The scene the words painted for him was a long tunnel of steel and concrete with four sets of rails gleaming softly in the spaced glow of signal lights. At midnight the subway trains were jammed with men, women, children, returning from the theater, from dances, parties—a gay and carefree throng with lights in their eyes and songs on their lips. And jewels in their ears and on their breasts and fingers, money in their pockets. Not much to each perhaps, but the total on any train meant rich loot for the taking if any person could devise a way of taking it. The Fog had.

In the long stationless stretch where the tracks ran under the Boulevard from Second Street to Twentieth, the subway was alive with dark forms. They were hidden in the niches in its walls provided for the trackwalkers' safety; they melted into the dark pillars that support the tunnel's roof. One by one, from several stations, they had drifted unobserved to this point.

Between the tracks ran a deep trough designed for drainage. Full length in this trough lay a black-clothed man, almost invisible against its dinginess. His arm was outstretched and his hand was upon the lever of a switch whose signal light had been tampered with so that when he threw the switch the light would still show green.

A train rushing at full speed upon it, its engineer unaware of danger, would be sure to leave the rails. Catapulting cars would crash against the pillars, piling against the walls of the tunnel. There would be darkness, screams, death.

In the confusion of that holocaust the waiting horde would reap their harvest.

But there was more than this to the horror The Fog had planned for the midnight now only four minutes away. Gagged and lashed to a pillar which the wrecked train inevitably must strike was a girl's slender figure. Mary Doan's death would accompany the death of those other hundreds, but about her smashed body would curl tendrils of gray mist, emblem to The Fog's cohorts and to the world of how he dealt with those who would betray him.

"Faster!" Luke Cass croaked to his driver. "Faster!"

The careening taxi wheeled a corner into the Boulevard, straightened on screaming tires for the run south, and all the maniac could say was, "Faster!"

The lighted hands of a tower-clock were barely a minute apart, and there were still five blocks to go. Street signs flicked past. Seventh, Eighth, Ninth...

"Here she is," the driver yelled above the screech of his brakes. "Tenth Street."

The roar of the approaching subway train was deafening in the tunnel. A scream beat against Mary Doan's gag. The fingers of the prone man in the trough tightened on the switch-lever for the pull.

And light struck down at him from above. With the light a shadow dropped, apparently riding a thick cane like a witch on a broomstick.

IT happened so quickly the others were aware only of a flash

of blackness across a sudden glimmer of light. They leaned out

into the thunder of the doomed train.

And the nearest saw, on the brow of the one who lay in the trough, a brilliant yellow spot! But almost at once these nearest thugs saw nothing at all.

The cars blasted past the rest, their thunder dazing them, the flash of light from the windows blinding them. When they were gone safely there was a leaping, striking black shape among the ghouls, a shape that lashed at them with a whirling cane that stabbed like lightning.

"The Yellow Spot!" someone shrieked. "Beat it, guys! It's the Yellow Spot!"

There was scarlet panic then among the ghouls that had waited to rob the dead and dying, a scurry of terrified feet, and a howling. And above it all was the crunch of smashing skulls, the screams of those into whose flesh a flashing ferrule stabbed and jerked out to stab again.

There was, at last, a lone, black figure who cut free from the pillar to which she was lashed, a chestnut-haired girl who had fainted. Luke Cass, alias the Yellow Spot, tenderly lifted Mary Doan in his arms.

"Cripes," the taxi driver up in the street muttered. "That guy didn't give me the other half o' that double sawbuck. Maybe I better take a look."

He shoved out of his seat, lumbered around to the door of the taxi's passenger compartment, and opened it. The interior of the cab lit up.

The other half of the twenty was on the seat with a collection of curious objects.

There were tattered trousers and a ragged jacket. There were two malformed shoes. There was a pair of black goggles whose temples were twisted rusty wire, and a matted clump of brown hair that when shaken out proved to be a short false beard. Luke Cass had apparently disintegrated.

AT eight in the morning after these events Patrolman George Daley,

just coming on beat, was startled by a shrill scream from an

upstairs window of the home of Curt Stryker on Gratton Street.

"Murder!" came the words. "Murder! Police!"

He looked up to see the wrinkled face of the old crone known as Biddy almost cut in half by her gaping, toothless mouth. And Daley took it on the run for the house, mounting the stairs two at a time. When he reached the room from which Biddy was screaming he found murder indeed, but it had been done hours before, as the clotted, brown condition of the blood that was everywhere attested.

The blood came from two corpses. One, half his face shot away, Daley knew as Curt Stryker. The other was curiously involved in a mass of gossamer gray draperies.

The cop bent to this one, pulled the netting away from where he figured its head must be. The stuff tore, revealed a face already blackening.

"Gawd," Daley exclaimed. "Gawd, I know this guy. It's Judge Alton Flinder. Guess I'd better get the Homicide Squad on this case quick."

The swarming detectives of Homicide found some curious things in that house. There was, for instance, an opening in the wall between the office and Stryker's bedroom that could be closed by a sliding panel. When they investigated that aperture they found rotted old steps that went down within the thick walls of the ancient mansion, to join, in its basement, a tunnel. The passage went under the yard behind, under another yard and into the basement of a house on Apex Street whose deed was registered in the name of Alton Flinder.

In that passage the detectives found, among other things, cans of a chemical that when opened emitted gray, fog-like vapors.

On the wall near the entrance door, one observant officer discovered a circular yellow spot. But no one paid that much attention.

At eight o'clock that same morning, James, Lloyd Foster's valet, tiptoed soundlessly into his young master's room to raise the shades. He checked himself, recalling what in his early morning daze he had forgotten. Foster was in the hospital.

A gentle snore from the bed whirled him to it. His master lay there, sound asleep. The blankets had fallen back to show that the bandages on his left shoulder and chest were brown and stiff with dried blood. There was a new and angry wound across his forehead. But on his lips there was a peaceful smile.

It must have been James' exclamation of surprise that woke his employer. The latter's eyes opened.

"Don't pull up the shades, James," Foster smiled sleepily. "I'm not getting up. I'm going to sleep all day."

"Very good, sir. And shall I rouse you at the usual hour tonight?"

"No, James. I'm going to sleep all night."

The valet's grave visage wrinkled into a smile. "May I hope, sir, that this is a permanent arrangement, that your nocturnal absences have come to an end?"

"You may hope, James, but it won't do you much good. My job hasn't ended yet. There's still work ahead of me."

"Very good, sir." The valet's tone gave the lie to his words.

"Oh, James," Foster stopped him as he turned away. "Don't make any noise around the guest bedroom. There's a young lady in there who needs sleep as much as I do."

"A young lady, sir?"

"Yes. I think she's going to help me with that work I still have to do. And maybe with some other plans, too."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.