RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

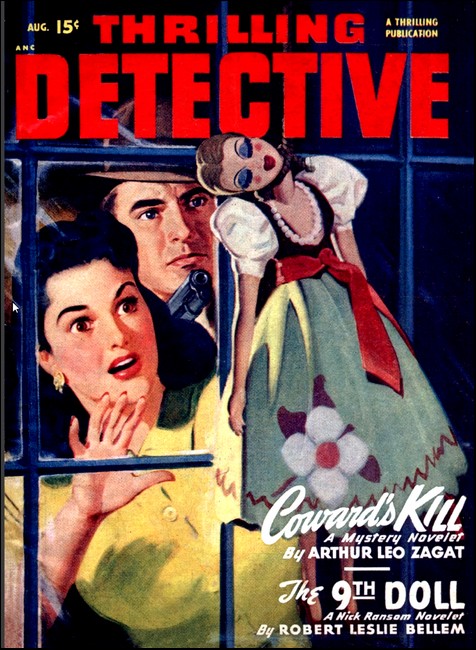

Thrilling Detective, August 1948, with "Coward's Kill"

When gambler Ted Storme meets "Feet" Dorgan, underworld

boss, he faces big odds in an impromptu game with death!

IF the man who stood at the long bar on the mezzanine of Tom Goslin's Biarritz Casino on Long Island was aware that he was marked for death, he gave no evidence of it. Long-limbed, lithe in his impeccable dinner suit, he was young, about twenty-five or -six, but his narrow, bony face was an expressionless mask as he watched a fly that had got itself half-drowned in a spill of cordial and crawled along the blue-mirrored bar top, its wings sticky and useless.

From some three or four yards away, in the buzzing, convivial crowd along the counter, a girl eyed him owlishly.

"Why, Jock?" she asked her baldish, rather obese escort. "Why's he all alone? Why's everybody not talking to him?"

"That, Mimi my dove, is Storme." Jock Haddon, Broadway character about town, seemed to think it was a complete answer. "Ted Storme."

Even Mimi Barton recognized that name, though she was more familiar with another variety of "bohemians," those she knew in Greenwich Village where she was making her home, while playing at learning "art." It had been on the impulse of the moment that she had come to the Biarritz with Jock Haddon, for she was sure a girl could not learn too much about all kinds of people in New York. And now she was learning plenty.

As Jock mentioned the name of the gambler, Ted Storme, Mimi's violet eyes widened.

"The man they say never loses a bet!" she exclaimed.

"Darned near," Haddon agreed. "Too near for the wise mob he's run ragged since he hit Broadway about six months ago. Those pretzels can't figure out if he's so straight they crack up trying to fit their curves to him, or if he's the slickest operator who ever came to town."

"From where, Jock? From where did he come?"

"You ask him that, or anything else personal, and he'll freeze you so hard they'll wrap you in wax paper and label you Birdseye."

"Not me, he won't." Mimi tossed her honey-hued clipped curls. "Watch me go to work on him." She started away, was dragged back by a sudden, fierce grip on her arm. "Keep clear of that bird," Haddon said huskily, black lights flickering in his too-small eyes. "Stay away from him unless you're looking for trouble."

"Trouble?" The girl wrenched free and faced him, her body taut in the shimmering white sheath of her strapless frock. "From you?"

"No, not from me. I'm on to your little tricks. I mean bullet-trouble." He glanced fearfully at their neighbors, dropped his voice to a murmur. "Storme took ten thousand from Feet Dorgan in the floating crap game last night and Dorgan got the notion he did it with a pair of educated ivories. That bird's blazing hot, what I mean, and anybody near him's liable to get burned with him. Look, honey, the lights are dimming. Let's get to our table before Jennie Wrenn comes on."

"Hang Jennie Wren. I like your Ted Storme and I'm going... Oh-h-h!" Mimi stopped short. "Someone's starting to talk to him. Is he one of Dorgan's—?"

"Torpedoes?" Haddon stole a quick look, shrugged. "I never saw him before, but that don't mean anything. Could be he's some out-of-town gunsel Feet's imported to iron Storme out."

"No-o!" Mimi moaned. "Oh no, Jock. He's too nice."

Then the rush to get to the tables carried them down the short flight of carpeted steps from the mezzanine.

WITH the crowd gone, one could see the innumerable tiny silver

bees—B for Biarritz—that studded the bar front, blue

mirror-glass like its top, and the dozen larger, golden ones that

were poised along its inner edge to conceal plebian beer taps.

But it was the living fly at which the man who had ranged himself

beside Ted Storme jabbed a gnarled forefinger.

"Pertinacious little cuss, ain't he?"

"Very."

Storme's eyes, the color and seeming hardness of chilled steel, flicked to the speaker and flicked instantaneously away. The glance had photographed every detail of the gaunt, leather-textured countenance, including the healed bullet-trough that angled down from beneath grizzled hair. A bier man, taller than Storme and solidly built, the stranger obviously was ill at ease in a tuxedo as obviously newly bought.

"Hades nor high water," he drawled, "ain't a-goin' to keep that jigger from gettin' to the back edge of this shelf."

"Not the back," Storme corrected. "I've been watching that fly for five minutes. If and when it leaves the top of this bar it will be over the front edge."

The big man's face hardened. "I think he'll go over the back, and down in Brazos County we back our opinions with our cash. What do yuh say, stranger?"

"Suits me." Storme produced a well-stuffed wallet. "For how much?"

The Texan looked at the fly again. It was still crawling toward the back of the bar.

"For one thousand," the challenger said.

He brought out of his trouser pocket a roll of bills almost as thick as his fist, started counting fifties down onto the blue mirror. A bartender moved nearer, started polishing the bee-hidden draught arm opposite them. In the shadows at the far end of the counter a thin, ferret-faced chap stiffened, black eyes glittering.

"Nine-fifty," the big man finished his count. "One thousand. There yuh are, stranger." The roll he thrust back into his pocket but little reduced in diameter. "Cal Carroll don't back water for nobody."

Storme covered the money with ten hundreds. Applause splattered from the big room behind him and he turned to look.

Far across the now dimmed room blue satin curtains swirled apart to unveil a stage high-banked with men in yellow satin monkey-jackets, their instruments glinting as they blared an entreaty to Richard to open the door.

A spotlight noosed a microphone staff that grew upwards at the stage's front, center, with brilliance. A roly-poly little man trotted into the bright disk, brown derby canted back on plastered-down hair, loudly checked coat and pants ludicrously too tight.

From somewhere in the dark a whisky-slurred voice called, "Hi, Sam Slats!" Others shushed it.

Behind Ted Storme's back the fly suddenly stopped short, inches from the bar's rear edge and flattened itself down on the glass.

"Come on!" the barkeep whispered. "Come on, baby. There's two grand rid-in' on your back."

In the room Sam Slats took hold of the mike rod, his round, goggle-eyed face bisected by a clown's grin.

"Thanks for the greeting, customers, but you ain't fooling me. I know you didn't come here tonight to listen to my gags. You came to be present at a great event in the history of the American stage—the return from retirement of that tiny songstress, that diminutive interpretress of musical classics who won the hearts of your fathers and your grandfathers with her own inimitable voice."

He turned to the left, held out both arms in a gesture of welcome.

"Ladies and gentlemen. I give you the one, the only Jennie Wrenn!"

And was butted out of the spotlight by the spangled pink buttocks of an enormous female who had galloped from the stage's darkened right wing.

Applause thundered as she loomed above it, blonde-wigged, flabby-jowled, and threw kisses, using both bare, bulging arms. On the mezzanine the barkeep swore softly as the fly started moving again, slantwise across the bar toward its front.

Storme came around, smiled without humor.

"You lose, my friend."

"Not yet," Carroll grunted. "It can still turn back."

"It can, but I don't think it will."

"Okay, Mr. Storme. I've got another thousand says different."

"No."

"No?" The Texan stared unbelievingly. "It's a fifty-fifty bet, ain't it?"

"Precisely. That is why I won't make it."

The bartender snorted disgustedly. Below the balcony the applause faded and from the stage Jennie Wrenn said, "Hello suckers!" She laughed girlishly. "Your warm greeting brings tears to my eyes, and that reminds me of the fellow who came back from a month in Florida all tanned but with his eyes red and puny. When his partner asked him how he got that way, he told him about the blonde he'd met on the beach—"

She went on with the smoking room yarn, but on the mezzanine the fly reached the bar's front edge, went over it and dropped to the floor. Storme picked up the sheaf of bills.

"The drinks are on me," he said, expressionless as before. "I'll have mine as usual, Jim."

The barkeep looked at Carroll.

"Give me the same," the Texan growled, and then to Storme, "Yuh win, but yuh'd a won twice as much if yuh was a real sport."

"I'm not a sport." Storme stowed his winnings in his wallet, dropped two singles on the bar. "I'm a professional gambler. I don't risk my money on any proposition that doesn't give me a percentage in my favor." Oddly enough, now that the issue was decided he seemed gripped by a tenseness that had not been in evidence before. "I told you I'd been watching that fly for five minutes. In that time it approached the rear of the bar three times and turned back each time because it was frightened by the reflection of the big golden bee in the mirror."

Carroll's jaw dropped. "I'll be everlastingly hornswoggled." He reached for the tall glass the bartender had set in front of him, gulped a swallow, choked on it, and stared at the white liquid left in the tumbler, on his raw-boned features a mixture of disgust and amazement. "C-cow juice," he spluttered. "Milk!"

A FAINT smile touched Ted Storme's thin lips but did not ease

their grimness.

"In my business, Carroll, I can't afford to drink anything stronger. If I'd been doing so tonight, for instance, I might not have noticed the single time you forgot to call me 'stranger' and used my name instead."

The audience whooped as Jennie Wrenn and Sam Slats engaged in Webersfieldian slapstick.

"Yeah," the still-faced Texan acknowledged. "Yuh was pointed out to me." His right hand dropped into the side pocket of his coat and made a bulge there. "I got some business with yuh ought to be done where it's more private." He looked down along the room's side wall to a small door over which a red light burned. "I reckon that gives out on the car-parkin' corral. S'pose we go thataway."

"Very smart," Ted Storme murmured. "If we left the front way, the coatroom girls and the doorman would see us together and they might remember afterward. Down there everybody's looking at the stage." He finished his drink, turned down the empty glass. "Let's go," he sighed. "Let's get it over with."

AM SLATS ducked a buffet from Jennie Wrenn's big hand.

"Hey, Jennie!" he panted. "Maybe the customers'd like to hear you sing the 'Gay Caballero.'"

"Aw, no." Pink-spangles wriggled in embarrassment. "Not that!" Lavish grease paint could not hide the crowsfeet under mascaraed eyes, nor the unlovely loose skin at an aged throat. "I couldn't. Ruhlly I couldn't."

"How about it, folks?" Slats appealed across the footlights, and affirmatives roared back at him out of a clatter of silverware on Tom Goslin's bee-sprinkled chinaware.

Jennie nodded to the orchestra leader. The strains of the bawdy tune blared out.

The scent of expensive perfume was heavy in the big room that was lit only by shaded electric candles topping the porcelain beehives on each table.

"Jock," Mimi whispered to her companion. "Isn't that Dorgan over there?"

Haddon let his look slide to the table, next but one to theirs, toward which she jerked her dimpled chin.

"Yes," he said. "Yes, that's Dorgan all right."

"I don't see why everybody's so scared of him," Mimi said. He was a little man all sleek tailored curves, his face round and apple-checked under a mane of snow-white hair gleaming silkily in the dimness. "He looks like Santa Claus."

"Some Santa Claus," Haddon muttered. He took the girl's dimpled chin in the V of his thumb and forefinger. "If you're getting ideas about Dorgan, skip it. He's a wolf that eats up honey-sweet little gals like you for dessert."

"Jock!" Mimi gasped. "Look over there, by the wall."

He turned, saw the lean figure that moved smoothly along blue silk drapes, and the taller form that kept close alongside.

"Ted Storme and that other man, Jock," Mimi said. "That... What was it you called him? That gun—"

"Gunsel." Haddon was a little pale around the gills. "Taking Storme out."

"There's another one, Jock!" whispered the girl. "Sneaking along behind them."

A spray of light from a canted candle shade fell across the weasel face of the thin-bodied individual who'd lurked in the shadows at the end of the bar.

"Him I know, Mimi," said Jock Haddon. "That's Gull Foster, of the Dorgan mob. Guess Feet's taking no chances on his imported killer slipping up."

"Killer!" The girl's pupils dilated. "Jock Haddon, how can you sit there so calmly when ... We've got to do something, Jock! We've got to save... Ohhh! They're going out that side door to the parking lot and that Foster's hurrying to catch up. Jock!"

"Keep still, you little fool! Do you want ... Oh, Christopher!"

Mimi had pushed up out of her chair. Haddon grabbed at her, but she evaded him, was running toward the steps leading from the mezzanine....

Ted Storme went through the side door just ahead of Carroll, stepped to one side as the Texan came through. Storme's rock-hard fist flailed to the big man's midriff, another to the jaw which the first blow had brought down within reach. Carroll sagged, folded down on the threshold, but before he had stopped falling Storme already was feet away along the building's wall.

Glare from a naked three-hundred-watt bulb over the attendant's booth at the entrance glinted on car windows but toward the casino's rear a small shed made a patch of Stygian black. He reached this cover, glanced back as a sudden burst of sound came from within the larger building.

The door out of which he had come was slitted open again. "Gull" Foster squeezed through, shut it softly, stared down at the limp, sprawling Carroll. Traffic sound seething past the high black hedge that divided the lot from the highway was threaded by the shrilling of a traffic cop's whistle. A woman's voice cried out thinly.

Foster peered through the rows of parked cars, started toward them, hesitated, then turned back and bent over the stunned Texan. But a thud of running feet from the gate leading to the lot jerked the black-polled little thug erect again.

His gesture of his hand toward his lapel was paralyzed by a hoarse bellow.

"Reach, you! Grab air or I'll let some into you!"

A burly cop pounded toward him, revolver out. Foster's arms lifted.

"It's okay, Officer," he said suavely. "My friend here had a snootful and I brought him out here and he passed out. I was just lookin' after him."

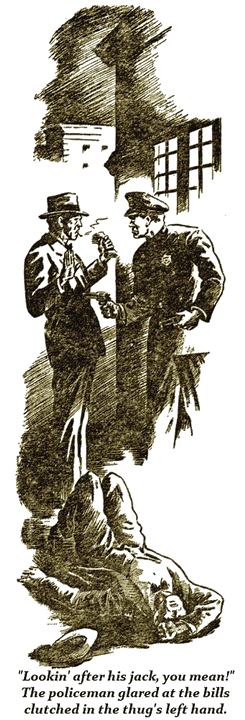

"Lookin' after his jack, you mean."

The policeman glared at Cal Carroll's plethoric bill roll which was clutched in the little thug's raised left hand, jabbed his gun muzzle into Gull Foster's midriff, slid his own free hand under the tuxedo jacket's flap and brought out a flat, lustreless automatic.

"All right, punk," he growled. "Let's have your wrists."

FOSTER held them out and nickeled silver clicked around them

just as the gray-haired parking lot attendant limped up.

"Hey, Grady! Hey! I seen you dive past me and ... How'd yuh know what was goin' on?"

"Gal in a white dress comes sailin' out uh the Casino to where I'm direct-in' traffic, peaceful-like, and tells me someone's bein' bumped in here." Officer Grady plucked the roll of bills from his prisoner's reluctant grasp. "Listen to them horns blattin' out there on the crossin'! I ought to be out there an' I ought to be takin' this lush-roller into the house, and I ought to be doin' some-thin' about this stew he was friskin'. Now how—"

"Yuh don't have to do nothin' about me, mister." Cal Carroll sat up, dazedly rubbed his jaw. "I'm not stewed. Not on milk, but—" He gulped, his eyes focusing on Foster. "Hey! Where's—"

"Your cash? Here." The cop held it out but jerked it away from Carroll's reaching hand and shoved it into his own pocket. "Sorry. Got to hold it for evidence. You'll get it back from the magistrate in night court, after yuh've signed a complaint."

"What complaint?" The Texan lumbered erect, big hands fisting. "Yuh can turn this pipsqueak loose, Officer. I'll take care of him myself."

"Nix," Grady refused. "Nothin' do-in'." He turned to the lot attendant. "Yuh got a phone in that booth of yours, Pop, I can call the house for a squad car from?"

He pulled at the chain linking Foster's wrists and the little group got moving. Quickly it was hidden from Ted Storme by the black bulk of a limousine. Storme smiled thinly in his cover.

"I better get distance between me and here before Dorgan puts some more of his hoods on me," he muttered.

He drifted along the wall of the shed in whose shadows he had crouched, got past its corner—and stiffened. A sound half-heard, a feel of movement in the shadows, sheathed his body with iciness....

On the sidewalk before the wide, white-painted steps that climbed to the front entrance of the Biarritz, Mimi touched the back of Jock Haddon's hand with a finger.

"I couldn't, Jock," she said pleadingly. "I just couldn't let him be killed without trying to do something to stop it."

"So you ran out here to call copper." Haddon's face was the color of yeast. "With Feet Dorgan himself watching you, three tables away. Here." He shoved a bundle of electric-blue velvet at Mimi. "Here's your wrap. If you've got any sense at all you'll grab a taxi and keep going right out of this town, but whatever you do, keep away from me. Do you hear?" His voice became a snarl. "Keep away from me. I don't want that snake after me."

He wheeled away, stumped stiff-legged back up the stairs.

"Jock!" the girl sobbed, the gleaming wrap trailing from her arms. "Oh, Jock."

And then what was left of color drained from her small face as the revolving door through which Haddon had vanished disgorged a little man with snow-white hair, a Santa Claus tummy that bulged his starched shirt-bosom, and twinkling, bright blue eyes.

The doorman flipped an obsequious finger to his cap visor.

"Your car, Mr. Dorgan?"

"No, thank you, Bill. I'm not leaving. I just want to speak to that young lady."

"Feet" Dorgan started down the stairs toward Mimi and she knew it was no use to run. No earthly use....

The sound that had held Ted Storme rigid came again. A tight sob. Vague reflection of light from the casino's white-painted side showed him its source. Apprehension drained out of him, was replaced by amazement as he stared at the little girl, scarcely thigh-high to him, whose small grimy face was tear-strained as she twisted in distraught little hands a knee-length plaid dress.

"Hello," he said softly. "Where did you come from?"

Enormous eyes lifted to him in the dimness. The child's lips quivered.

"Don't be afraid of me, sweetheart." Storme's low voice was gentle. "I'm not a boogie man. I'm only Ted, and if you'll tell me what's the matter I'll try and help you."

THE big eyes studied him with vast solemnity. What they saw

seemed to content the waif. She spoke, all in one breath.

"I'm Susan, and Mom's awful sick and I took a nickel from her pocketbook and came on the bus to tell Gram, and the man won't let me in."

He squatted down, but even then his head was above hers.

"What man won't let you in where?" he asked.

"The man with the gold flies on his collar. In the Bee—Beer ... In that place. I told him Gram works there but he chased me away and I sneaked in this lot and hid, and then the cop came after me Don't let him get me, Ted!" She snatched at his sleeve in sudden panic. "Don't let the cop get me!"

"Whoa! Whoa up, Susan. The cop wasn't after you. He was after a bad man and he caught him, but the cop's still out there by the gate so I guess we better talk low so he won't hear us. Now, look. Are you sure your Gram works in the Biarritz?"

"'Course I am. She gave me the paper from the agency for my treasure box, with the address on it and what bus to take, 'cause this is the first time she's working since I was little."

The corner of Storme's mouth twitched at that. She was no bigger than a minute now. About eight, he judged.

"Mom an' me were so happy Gram had work again," she want on. "That we romped in bed like we used to, and all of a sudden Mom got all white and fell down on the bed and wouldn't answer me." A sob caught in the tad's throat.

"Steady." Storme drew the warm little body to him. "Steady, honey."

"It's Mom's heart, Ted, and Gram wasn't there to make her better, and I didn't know what to do."

"Why didn't you call a neighbor?"

"I didn't dass't. We don't dass't talk to the neighbors or—or anybody 'cause if we do. They might find us."

There was so much of fear implicit in the eerie statement that the nape of Storme's neck prickled.

"They? Who?"

"The—the bad men who took Daddy away."

The police? But why should an old woman and an ill one and a child be hiding from the police?

"Well. Susan," Storme said, "in that case we'll just have to get Gram. Look. Go around in back of this big house here and you'll find the door to the kitchen. You go in there and if you don't see your gram—"

"In the kitchen? What would Gram be doing in the kitchen?"

"Isn't she a cook or—or something?"

"A cook!" There was in the way Susan said it a child's scorn for an adult who is being more than ordinarily stupid. "'Course not. Gram's vohdvil's greatest star!"

"What's her name?" Storme demanded. "What's your gram's stage name?"

"Jennie Wrenn."

"Jennie—" Muted by the casino's wall, the ribald strains of the "Gay Caballero" were just ending in a muffled storm of applause. "Good Lord, I can't let you hear ... Listen, Susan!" He caught back what he'd been about to say. "Your Gram can't be bothered while she's working, so I'll tell you what. See that cream-colored convertible over there—the one with the top up? That's mine. I'll ride you home in it and we'll get a doctor."

"No. I've got to go in there and get Gram.

"You can't honey. It—it's a bad place for little girls."

"Then you go get her for me."

"I wish I could. Susan. I certainly wish I could, but there's a man in there who ... Well, I don't, dass't go in there."

"You promised, Ted." The child's look was accusing. "You promised if I told you what was the matter you'd help me."

The skin of Storme's face tightened over its bones and his lids narrowed.

"So I did. I did promise you." His look drifted to a door in the side wall of the Biarritz, much nearer its rear corner than the one from which he had come. "All right. I'll get your gram for you." He lifted erect. "You go and sit in my car till I come back, and remember to keep very, very quiet."

His head turned to the black hedge along the parking lot's outer border, beyond which a police car's siren wailed to silence.

N the sidewalk in front of the Biarritz Mimi heard the wailing of the police car siren behind her, but she didn't turn. Watching shiny patent leather pumps come down the stairs toward her she was thinking, with strange inconsequence, that they were too small to explain why their owner was called Feet Dorgan.

# Quote

"How small your feet are," said Little Red Riding Hood.

"The better to walk on your grave with, my dear."

Quite suddenly blue eyes in an apple-checked moon of a face were twinkling merrily into hers.

"Jock Haddon's a heel." A small red mouth murmured the words. "But that's no reason you should have to go home so early." Pudgy fingers were clammy-cool on the hot skin of Mimi's arm. "Come and join my party, my dear."

Mimi's tongue-tip licked her lips. "I ... Thank you, but—but I'm not feeling well."

Behind her the police car's siren moaned again, going back the way it had come and Dorgan was looking past her, his eyes suddenly the color of an ice-covered lake under a winter sky.

She turned to look, too, saw a green and white car sliding by and in it two policemen and Gull Foster and the big man who had taken Ted Storme out of the Biarritz, but not Storme. He must be ... No! The cops wouldn't be taking those two away so quickly if they killed Storme.

"The best medicine for what ails yon," Dorgan purred, "is a glass of Veuve Cliquot."

The cold fingers on her arm urged Mimi toward the steps and she was climbing them beside the man people called Feet for no reason she could figure out.

They went through the revolving door, past the check-room. Mimi saw Jock Haddon at the bar and he spied them and choked on his highball. Dorgan jerked a chin at him.

"That phony's going to find out he's made one wrong play too many," he said, loud enough for Jock to hear.

Jock's glass slipped from his hand and spilled, and scared as she was Mimi couldn't help laughing at the way his eyes bugged out of his head.

On the stage Jennie Wrenn and Sam Slats were swapping jokes and everybody at the tables was laughing. The fingers on Mimi's arm stopped her and Dorgan said:

"Here she is, folks. Say hello to—er—"

"Mimi," Mimi filled in for him.

The two men at the table looked up at her but the big brunette sitting there, her dusky-red mouth bitter, just kept on looking at the stage.

"That's Bert Judson," Dorgan said, nodding at the younger man, a slim fellow, his close-shaved jaw bluish with hair under the skin. "And the bald-headed shrimp is Judge Ashton Lee."

"A judge!" Mimi exclaimed. "A real judge?"

"No." Lee's voice was as pale as his dough-hued face. His eyes were big and scary behind thick glasses, and his smile made Mimi feel crawly. "Just a lawyer."

"The best mouthpiece in ten states," Dorgan said. "The statuesque Juno there is Norma Wayne. Be nice to Mimi, Norma. She isn't your rival—yet."

"I'm not worried." The brunette's voice was almost as deep as a man's, and the slow, velvet-lipped smile that went with it was like a slap in the face. "I know too much about you, Henry Dorgan, for you to put me on the skids."

"Watch it, Norma." The blue-white frost was back in Dorgan's eyes and his voice was suddenly deep-throated. "You'll pull that line once too often. Maybe this is the time."

Mimi would have been paralyzed had he spoken to her like that, but Norma merely shrugged her gorgeous shoulders, picked up a champagne glass and sipped from it. Mimi sank into the chair a fussy waiter had brought for her.

"Oh, Judge," Dorgan said, "I'll have to take care of that little proposition by myself. Something's come up you'll have to get busy on right away."

The lawyer got up and Dorgan took hold of his lapel, moved with him into a clear space nearby.

"Guess some of the boys got into a jam," Mannie ruminated. "Well, Lee will spring 'em. He's some fixer."

Mimi was fascinated by the way the lawyer's long, thin fingers kept writhing over one another while he talked with Dorgan. He nodded, went away toward the wide stairs to the mezzanine, and Dorgan came back to the table and sat down. He didn't say anything, just sat there chuckling to himself and listening to Jennie Wrenn singing a song about two sailors and a girl and what happened when her father came home unexpectedly.

Bert Judson took a napkin-wrapped bottle out of the silver bucket on a stand beside him and spilled champagne from it into the fresh glass the waiter had put in front of Mimi. She drank it in a hurry and her nose tickled, but she began to feel a little better.

Outside, Ted Storme peered in through the half-inch slit he had opened between the stage-door and its jamb. The corridor inside was crowded with chorus girls waiting to go on, so he dared not enter yet.

APPLAUSE died away and Sam Slats and Jennie Wrenn ran off. The

orchestra swung into "The Flight of the Bumblebee," played fast,

and girls poured out onto the stage. They wore head-dresses of

black fur with great glittering glass eyes and feelers of black

ostrich feathers fastened to them so that they looked exactly

like bees' heads. Shimmery wings fluttered from the girls'

shoulder blades. Three not very big patches of yellow silk was

all the rest they wore.

They started dancing and buzzing. "Look, kids," Mr. Dorgan said to his party, "I've got something to attend to backstage." He got up. "Take care of Mimi, Bert. Don't forget I want her to be sitting right here when I get back."

"She'll be here." Judson chuckled. "Don't worry. Boss. She'll be sitting right here at this table."

"Make sure that she is."

The fat little man started walking away but somebody called him over to a table and he stood talking to the people there. Norma Wayne's maroon-enameled fingernails tapped the side of her glass. Her black-lashed, brooding eyes moved to Mimi.

"Look, youngster," she said. "If you're doing this just to spite the boy friend, my advice is to get right up and get out of this."

"Nix," Bert growled. "Lay off that stuff." He filled Mimi's glass again, and his own. "The smartest stunt you ever pulled, sweetheart, was to run out on that Haddon heel the way you did and look such a cute trick doing it."

"Did I, Bert? Did I look cute?" Mimi took a big swallow of champagne and wished Jock could hear this. "Was that why Mr. Dorgan came after me?"

"Why else? You don't think Feet Dorgan chases every skirt he puts his peepers on, do you?"

"Tell me, Bert. Why do they call him that? Feet?"

Judson's smirk faded and he looked uncomfortable.

"I'll tell you, Mimi." Norma said, lighting a long, rose-tipped cigarette. "People who cross Harvey Dorgan have a way of turning up with the soles of their feet burned to a crisp." A slow smile grew around the cigarette between her dusky lips. "See?"

The champagne glass chattered against Mimi's teeth. That lawyer, she thought, has gone to take care of Gull Foster and the big gunsel from out of town. He would find out who had sent the cop in to the parking lot to save Ted Storme and when he came back he would tell Dorgan. Feet Dorgan.

Dorgan had told Bert Judson to keep her there and he would. She would still be here when Judge Lee came back.

The noise of the band beat against Mimi's ears, beat into her skull. The bee-girls came dancing down off the stage, were dancing among the tables to give the Biarritz's customers a closer view of their "art"—and their flesh. Bert unwrapped the napkin from the bottle and held it up against one of the spotlight beams that followed the dancing girls around.

"There's just about one drink left," he decided. "How's for you killing it, Norma?"

"Swill it yourself, Bert." The brunette dragged her sables around her. "I've got to see a man about a dog." As she got up, her bag, a hie? one of platinum mesh as fine as hair, thumped against the table edge as though it held something heavy. "That is, of course, if you have no objection."

Bert shrugged, filling his own glass. "The boss didn't say nothing about keeping you here."

"That's right. He didn't." Norma was taller than Mimi had expected, and her lustrous black gown sheathed a figure Hedy Lamarr might well envy. "Maybe that will turn out to have been a mistake."

She glided away toward the mezzanine. Something about the way she moved reminded Mimi of the black panther she once had seen in the zoo.

"Huh!" Judson muttered. "She's sure taking it hard."

"Taking what hard?"

"Feet's going for you."

"For me!" Bubbles of laughter pricked Mimi's tonsils. Or was it the champagne? "Where do I shine in with her?"

Bert blinked at her owlishly. "Nowheres," he replied, frankly. "But you're not a bad piece of fluff and the boss is ripe for a change. The way he stepped on Norma before, when she cracked wise, was the tip-off she's on the skids. Well"—he shrugged—"it's no buttons off my vest. Here's to crime, kid."

"Down the hatch."

Mimi drank. It didn't do any good. She was still cold. Awfully cold. Judson's glass tipped over as he put it down, and his grab for it only knocked it over. He was pretty high. Mimi got an idea.

"If you'll order up another bottle, Bert," she said, "I'll come around there and sit by you."

How was she going to work this? If she could only think. If the drums would only stop pounding at her head!

HE pound of drums was wall-muffled in the backstage corridor, ill-lit and redolent of grease-paint and body-sweat. Ted Storme had flattened himself against a plyboard partition, shielded by the half-column that jogged out of it. He had heard the chorus girls rush out and had slipped in here, but Sam Slats had come into the passage with Susan's gram and gone into her dressing room with her. They were talking now, just the other side of this thin wall. Storme could hear them almost as well as though he were inside.

"I'm through," Jennie Wrenn was saying, her voice husky with fatigue. "I haven't got it any more, Sam."

"Through?" the roly-poly little clown snorted. "Through, she says she is and her just after rolling the town's toughest audience in the aisles."

"With what? With a line of burlycue hokum makes me feel dirty all over. Urrgh. If I wasn't at my wit's ends how to buy groceries for Vi and Susan I'd have slapped the script in Tom Goslin's mug."

"Shucks, Jen, the Goose has got to give the customers what they want. Say, I didn't have time at that rush rehearsal to ask you how that red-headed daughter of yours is."

"Bad, Sam." A sigh quivered through the plyboard. "That pump of hers ... I've had her all over—Boston, the Mayos at Rochester, every place I heard there was some doc knew something about tinkering with busted tickers."

"And no soap, eh?"

"Not even suds. Worst of it's the way we've dragged little Susan around ... Is that lassie a sweetheart, Sam!" Warmth came into the dreary tones. "I... If anything ever happened to her, I'd cut my throat."

"Yeah. I guess you would. Say, all that running around and doctoring must have cost you plenty. So that's where the sock you retired on went to."

"That's where it went to, old-timer. Didn't take long. Five years. And now if you don't get out of here and give me a chance to rest, you'll find yourself doing a single on the two a.m. show. Go on now. Take a powder."

Ted Storme squeezed hard against the wall as the door just beyond the jog opened and shut again. Sam Slats' footfalls plodded away down the hall and another dressing room door creaked open. Storme started out, pulled back behind the column again, his throat drying.

The last man he wanted to see had come into the corridor, down there at the other end. Feet Dorgan.

He glanced back toward the entrance and decided he couldn't make it unobserved. The fat man's heels clicked on bare wood as he neared. Storme held his breath, his body taut. Dorgan was just the other side of the pillar when he stopped coming on. Jennie Wrenn's door rattled open, was shut again.

"You!" The woman's voice inside the room was startled. "Get out of here!"

"I'm disappointed, Jennie," Feet Dorgan purred. "I expected a warmer greeting after all these years."

"Warm? Hot's the word for what I ought to give you! A red-hot poker for choice." Despite the bravado of the words, Storme detected a quaver of something like fear. "Are you getting out, or do I have to call Tom Goslin to throw you out?"

"Go ahead and call him. See if hell throw out his angel."

"His what?"

Dorgan chuckled. "The Goose is just fronting for me. I own ninety per cent of the Biarritz."

"You own—" Heavy breathing came very distinctly through the thin ply-board. "So that's how—"

"Art Rand got you booked into here. Five hundred for the week, with options. You snapped it up, figuring you could grab a quick stake and drop out of sight again before I got track of you. Where you made your mistake, Jennie, was using the old name."

"I had to use it. It's the only thing I've got left to sell. But I—"

"Didn't give Art your home address, told him you'd come to the office to check on whether he'd found a job for you. You thought you could keep covered that way."

"I'm still covered. If you think you can make me tell you where Viola is—"

"I know I can. And you do, too, old gal. You haven't forgotten why they call me Feet Dorgan."

A SHARP inhalation. "No, I haven't." The sound of it told

Storme it was said through stiff, suddenly white lips. "How could

I forget when every time Vi's heart acts up it reminds me how it

got that way?"

"You shouldn't have let her go to the morgue," Dorgan chided. "The police would have accepted your identification."

"Ben Castle was her husband. I had no right to keep her away." Jennie Wrenn checked herself. "But that's water under the bridge five years ago. Suppose you do locate Vi, what then? You'll be no nearer finding out where Ben cached them numbers racket collections he gypped you out of."

"I won't be, eh?" The fat man's tone was still suave. "We got it out of Ben, just before the cops hopped us and I had to put lead into him, that he'd told her where he hid it. She knows where that seventy-five thousand is, and she's going to tell me."

"Not in a million years she won't."

"So you think."

"So I know, Dorgan. Listen. Last week we didn't have a cent left in the house and I dam near went on my knees to Vi, begging her to go get a little of that money, just enough to keep us from starving. She wouldn't. She said—get this, Feet Dorgan! —she said eating food with the money that cost Ben his life would be like eating a piece of Ben himself. Someway that swag, wherever it is, has come to mean Ben to her. Do you think she's going to turn Ben over to you? Do you think you can make her! Viola Castle's got the best protection against your cute little tricks anyone could have, a heart that'll conk out the minute you start on her. You didn't think of that, did you?"

Ted Storme relaxed, the cords in his neck aching as though they had been taut for hours.

"Maybe," Dorgan was saying slowly, "I didn't. Or maybe I remembered something you seem to have forgotten." He paused, and the suspense was agonizing. "Such as that your daughter Viola has a daughter of her own."

Silence again in that dressing room, for ten pounding heartbeats in which the blare of the band from the stage outside was somehow obscene.

Then, "No!" Susan's gram moaned. "No! Not even you can be that low."

"Can't I?" Storme heard as he stepped around the pillar, closed fingers on a chipped doorknob and started to turn it with slow, infinite precaution against any sound that might warn the man who was saying, "For seventy-five grand I can be ... Stop! Get back, you old—"

A gunshot's flat pound cut off the sudden, startled shout. Inside the room a heavy body thudded to the floor. A single saxophone brassily declared, "That's All-ll," and the muffled music stopped....

People started to applaud as the show ended on the saxophone's brazen, "That's All-ll." Mimi clinked her glass against Bert Judson's. "Here's to crime," she giggled.

"Drink 'er down, Bert ol' top."

"Mudinyereye," Bert mumbled, and emptied his class, but Mimi once more managed to spill hers into the silver ice bucket between them without his noticing.

The handclaps gave way to a rapping of little wooden hammers on tabletops, a clatter of silverware on plates. Judson's hand fumbled for the bottle, didn't quite make it, dropped to his side. The music started to play again and the applause to die down. Bert Judson looked blearily at Mimi, slumped over on the table, and cushioned his head on his arm.

Her throat got so tight she could hardly breathe. The bee-girls were on the stage again, dancing an encore, but all Mimi saw was eyeball-white glittering between Bert's almost closed lids. She put her hands on the table-edge to push up.

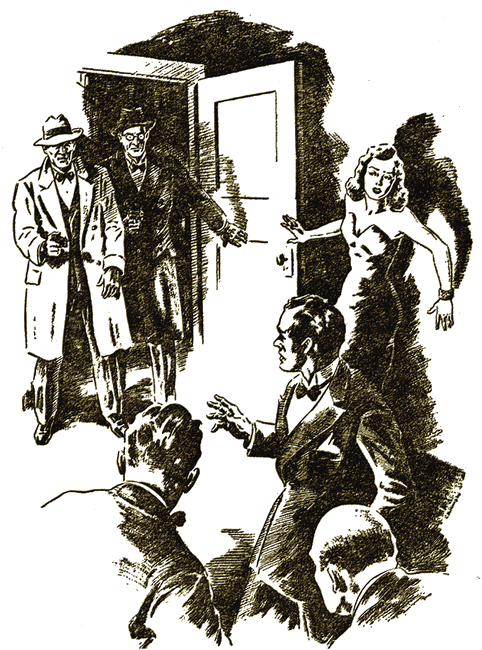

"Where's Dorgan?" a languid voice asked. Ashton Lee goggled down at her through his thick glasses.

MIMI'S mouth opened but she couldn't make words come. The bald

little man had on a dark-blue top-coat and his pallid fingers

writhed on the brim of a Homburg hat that matched it in color.

His look went to Bert, came back to her.

"Where's Dorgan?" he asked again.

"He—he went backstage."

Lee's fingers stopped writhing, but the way they crumpled the hat's brim was worse.

"How long ago?"

"Right after you left."

"Norma go with him?"

"No. She went to the—"

Before Mimi could say where the lawyer was on his way toward the door at the end of the stage, Mimi got to her feet, plucked up her wrap and started the other way, toward the front door.

She wanted to run, but she couldn't. Her legs felt as if she were wading through water up to her waist but she got to the mezzanine stairs somehow; somehow climbed them. She kept going, however, through the lobby, through the revolving door, down the wide entrance stairs. She stopped short at their foot, terror flaring into her eyes as she spied the traffic cop she had sent into the parking lot to save Ted Storme talking to the slim, black-haired killer Jock Haddon had told her was Gull Foster.

The cop saw her. Pointed to her. Gull nodded and started coming across the gutter.

TEPPING into the grimy dressing room, Ted Storme's brain registered the fat body sprawled on the uncarpeted floor. But not Jennie Wrenn. Dorgan, a splotch of crimson marring the silken white of his hair above the stare of his sightless eyes. The actress, her huge, pink-spangled bulk backgrounded by the black rectangle of an open window was straightening up from a feral crouch, and her hand held a pearl-handled revolver. A woman's weapon, but still deadly at this close range.

"Hold it," Storme said quietly as he pulled the door shut. "I'm on your side. I know you had good reason to kill him."

"Reason to kill him?" she repeated dully, apparently too dazed to be startled or afraid. "But I didn't. I didn't have anything to kill him with."

"What's that in your hand? A powder-puff?"

She looked down at it, a sort of horror coming into her face.

"I ... It came in through the window." Her features were ghastly under their mask of make-up. "I—" She stared up again at Storme, pupils dilating. "I started for him and he yelled, 'Stop!' and there was a crack and this flew in through the window." Her brow knitted. "Some—someone must have shot him from outside."

"And threw the gun in here to fix you in a kill-frame." Storme said, and moved swiftly across the room. "Which you've made perfect by putting your prints on it." He reached the window, leaned out. "State you're in I'd lay a hundred to one you're not lying, but I'm the only one who'd believe you." He looked out on the casino's dark back yard. The kitchen, a one-story addition, loomed blackly to the left. "Your only chance to beat the frame is to find the real killer and you haven't a whisper of a—"

The rattle of the door knob, behind him, cut him off. Storme vaulted over the sill, lighted catlike and twisted, peered in over the sill in time to see the door shut again behind a shiny-pated little man in a dark-blue topcoat, eyes monstrous behind thick, round lenses.

"Lee!" Jennie Wrenn breathed, her back to the window. "Ashton Lee!"

Light glittered on Lee's glasses as he looked at the gun in her hand, looked at Feet Dorgan's body. A flicker of obscure satisfaction passed across his pallid countenance.

"I advise you to plead self-defense, my friend," he said. "Dorgan attacked you, you shot him to save your honor. We should not find it difficult to convince a jury."

"We?"

"My testimony as to what I saw and heard as I entered can either substantiate that story—or send you to the chair." Teeth showed in a bland—and sinister—smile. "I'm sure your daughter will not compel me to the latter regrettable alternative by refusing to tell me where she hid the money Ben Castle stole from—"

Running feet thudded in the corridor.

"Quick!" Lee snapped. "Tell me where she is."

"I'll burn in perdition first!"

"You'll burn, Jennie, but not in—" Knuckle raps cut him short, and someone called urgently, "On stage, Jennie Wrenn! They're yowling for you and Slats!"

"No!" the lawyer screamed shrilly. "Don't shoot me too! I didn't—"

The door burst open, let into the room a heavy-set, shirt-sleeved man.

"What the devil?" he barked, and gagged as he spied the corpse but kept on going, plucked the gun, from the woman's hand. Then he wheeled to Lee.

"She was going to shoot me, Tom!" the lawyer was jabbering. "She shot Dorgan and she was going to shoot me!"

"Shut up, you yellow pup." Tom Goslin looked disgusted. "Your hide's safe now." He turned back to the woman. "Gosh, Jennie! If you had to do it, why'd you have to do it in here?"

"I didn't, Tom! I—"

"Save it, old gal. Save it for the cops. It breaks my heart to have to turn you in, but what can I do? Okay, shyster. You got the nerve to stay in here and keep an eye on her while I go phone the Law?"

"Yes. Yes, of course." Ashton Lee gave a good imitation of a man just reprieved from death and still shaken. "As long as you've got her gun."

Goslin went out. Lee smiled.

"You should have accepted my offer while you had the chance, Jennie Wrenn," he said.

Storme saw the old woman's hand squash on the window sill behind her.

"You'll have to tell the police where you've been living with your daughter," Lee said, "and they'll tell me, and so I'll have my chance for a little talk with her."

"Maybe." She was still undefeated. "And maybe Viola won't be there when you get there. Maybe somebody will beat you to her and take her where you can't find her."

TED STORME knew that this was meant for him. His countenance

was gaunter than ever, his mouth more bitter when he reached the

cream-colored roadster in the parking lot and slid in under the

steering wheel. Susan sat up.

"Where's Gram?" she asked.

"She can't come just now, honey."

"But you promised. You promised you'd bring her to me."

"I did, and I'll keep that promise." His tone had all the solemnity of a vow. "But Gram's act's onstage." The motor purred to life under the long hood and the car was moving. "Whatever happens, the show must go on."

"Yes," the child sighed. "Yes, I know. The show must go on."

The roadster nosed out of the lot but paused briefly at the cut curb to let a black and red taxi roll past toward the main entrance to the Biarritz. The taxi blocked Gull Foster off from Mimi, stopped right in front of her and she grabbed at its door handle, wrestled it open.

"Help me!" she sobbed to the man inside. "Please help—"

Her throat locked. He was the big gunsel she had seen taking Ted Storme out of the casino to kill him.

Foster came around the back of the cab.

"Gotcha, you little stool pigeon," he snarled.

Strong fingers grabbed Mimi's wrist, pulled her into the taxi and a leg shot out of the door, planted a big foot on Foster's face. He flew backward but Mimi didn't see where he landed because the door slammed shut.

"Get after that yaller car afore we lose it and you're out a sawbuck!" the Texan yelled.

The cab leaped into fast motion, skidded around in a U-turn that piled Mimi in the far corner of the seat.

"If that doodlebug don't quit gettin' in my hair," she heard, "he's liable to get hurt. What was he pesterin' yuh about?"

Mimi's heart bumped her ribs. It came to her that the cop had only just told Foster about her and that this one don't know why he was after her. "Oh," she said, straightening up. "He made a pass at me and I didn't like it, and he didn't like that."

And then her breath caught again. The roadster they were trailing was rounding a curve in the highway ahead. Light from a car coming this way lit up the face of the man who was driving it, and she saw who he was.

Ted Storme!

The roadster straightened out of the curve.

"Gram's in trouble," Susan said with conviction.

Storme's nostrils pinched. "What makes you think that?"

"Your sayin', The show must go on.' That's what good troupers always say when they're in despr'it trouble. You can tell me about it, Ted. Gram always tells me when there's trouble. She says facing it is half the job of licking it."

She had courage, this chestnut-curled tot. "All right, honey. I'll tell you. The people you've been hiding from have found your grandmother."

There was darkness now on either side of the broad concrete highway, a darkness in which the wind from the roadster's speed roused a rustle of unseen shrubbery. Susan's whisper was no louder than that rustle.

"What are they going to do to Gram?"

"She'll be all right till I can figure out how to help her. How to clear her from the murder-frame! I promised I'd bring her back to you and I always keep a promise, but I'm sure she wants me to take care of your mother first."

"Gram would. That's the way she is."

"So I thought."

This road was a main artery down the Island's North Shore. Far ahead lights made a glow over the clover-leaf intersections where the routes to the various bridges to the city sorted out.

"Gram didn't have time to tell me where you live, Susan," Storme said, "and I've got to know it now because I've got to know which road to take."

Storme's fingers tightened on the steering wheel. The orange blink of a "silent policeman" flitted past. A closed hot-dog stand was a black mass drifting by in the night.

"We live on East Ninety-third Street," Susan said. "Near the old brewery by the river."

There was a lift in Ted Storme's voice as he observed, "That means over the Triboro Bridge and down the East River Drive."

The world in which he moved might hate him but he had won the trust of this clear-eyed child. He was too elated to notice the red and black taxi that followed him, far behind.

THE house where Susan lived was one of a dismal row of

identical five-story tenements fronting the narrow side street,

empty and desolate at past two in the morning. A pinpoint of

light burned in the vestibule, but the hall within was unlighted,

and uncarpeted stairs ascended from dimness to obscurity.

Climbing them, Ted Storme breathed the odors of vermin-riddled wood and moldering plaster, of cabbage and Parmesan cheese and garlic, of sweat-rotted clothing and unaired bedding and unwashed bodies, all merged in the miasmic aura of poverty. From behind scabrous doors came snores, a sick infant's fretful whine—

He stopped short, hand tightening on the child's hand he held. Below, the vestibule door had creaked open.

His tautly listening ears heard no entering footsteps, no human sound below there.

"Come on, Ted." Susan tugged at him. "We've got to go all the way up."

"I thought your mother had a weak heart."

"She never goes out, and the top floor rear's the cheapest rent."

"I see."

They got going again and reached the top landing at last. The door to which Susan pulled Storme and opened shut them into darkness ominously silent save for a pit-pit of water from some leaking faucet.

Her hand disengaged itself from his. He heard her patter way from him, heard a chair scrape, and blinked in the dazzle from an overhead fixture. The child climbed down from the chair she had mounted to reach the pull chain.

"Wait here while I see if Mom's decent," she whispered, and went across the room toward a closed door.

This was a kitchen. At least it held a gas range, a sink and gray slate laundry tub, and an old-fashioned ice-box, but there was also a round dining room table at its center, oilcloth covered. Along one wall was a cot bed and a rickety bureau with innumerable photos stuck around the mirror's ill-fitting frame.

"Mom," Susan called, opening the door. "Are you decent, Mom?"

O answer. Storme started toward the child, chiding himself for letting her face alone what might be inside that room. "Mom!"

A bedspring creaked, releasing the breath that hung on Storme's lips, and as the crumpled plaid dress was swallowed by darkness the shadow of a voice came from within.

"Susan! Susan, baby. Where have you been?"

"To the—to where Gram's working. You had a spell and I went to get her to come home and make you better, but she couldn't come."

"You shouldn't have gone all that long way. I just fainted dear, and ... Who's in the kitchen?" Terror flared into the faint voice. "Whose shadow's that on the floor?"

"Ted's, Mom. Gram sent him to take care of you."

"Light the light, Susan," the mother's voice said, and then more loudly, though still feeble, "You in there! Why are you hiding from me?"

"Not hiding, Mrs. Castle." Storme went through the door into abrupt brightness. "Merely waiting until Susan told you I was here."

This room was almost filled by the double bed on which Viola Castle lay. The deep-toned green silk of lounging pajamas, threadbare but still somehow reminiscent of luxury, outlined the terrible emaciation of her long body. Her disordered hair was a crimson flame about a hollow-checked, triangular face sharpened by suffering, and out of which gold-flecked brown eyes as large and terror-filled as a doe's at bay laid themselves on his face.

"I don't know you," her blue-tinged lips whispered.

"No reason why you should." The hand that Susan had taken was only skin and long, delicate bones, but its nails were meticulously cared-for. "You've never seen me before and the first time I ever even heard of you was tonight, when your little daughter told me about you. So"—Storme smiled reassuringly—"you see you've no reason to know me, certainly none to be afraid of me."

"You—you're not—"

"One of Dorgan's gang? No." There was no time for finesse. He would have to chance the effect on her of what he must tell her. "But I've got some bad news for you. Er—How about your going out in the other room for a while, Susan, while I talk to your mother?"

"No!" Viola Castle's free hand flung up. "No! She won't leave me alone with you."

Storme shrugged. "Very well. She'll have to hear, then. Listen, Feet Dorgan is dead, and your mother is under arrest for killing him."

"Did—did she?"

"No, but she's going to have a hard time proving it, and in the meantime what's left of his mob are hunting you. She found a way to ask me to take you and Susan to a place where you'll be safe from them."

"You're lying!"

"Why should I?" His eyes were on the flutter of heart blood in the dreadful hollow of the woman's throat. "To kid you into telling me where that money is hidden? You wouldn't tell that to your own mother to keep your child from starving." The fingers of the upthrown hand spread with startlement. "To eat food bought with it, you told her, would be like eating your husband."

"You know that," she whispered. "You could know it only from her."

"Precisely. Please believe me, Mrs. Castle. Please believe me that your mother sent me to protect you from your enemies. Please come with me to my own quarters, where you'll be safe from them."

"Let's, Mom," Susan broke into the momentary pause. "Let's go with Ted. He's nice. He's good and kind and—and we can trust him, Mom. I know we can."

"The instinct of a child," Storme urged, low-toned. "You're her mother. You should know how right it must be."

Viola Castle's eyes were still large-pupiled but, studying him, some of the fear went from them.

"Very well," she sighed. "We'll go with you."

"Good."

They decided there was no need to take time for her to change. It would be enough if she put on stockings and shoes while Susan packed the battered suitcase she hauled out of a closet. Storme discreetly withdrew to the outer room, half-closing the door between, and tried to stem his impatience by looking at the photos that encircled the speckled dresser mirror.

THE autographs sprawled across them evoked echoes of Homeric

laughter out of times past. Eva Tanguay. Pat Rooney. "From Eddie

Leonard to a great-hearted trouper, Jennie Wrenn." Great-hearted

was right. He had an odd fantasy that these old friends of hers

were asking him something and in his mind he answered them.

"I won't let her down. She wants me to take care of those two she loves first, but when I've got them safe in my home I'll do my best for her." A muscle twitched in his cheek and his head twisted to the sound of footfalls in the hall just outside.

The dark door rattled with a touch on its knob.

Before Storme could get there it was opening. The light showed him Cal Carroll, tall and sinister in the widening slit, left hand on the knob, right hovering near his tuxedo's side pocket.

"I got tired waitin' for yuh downstairs," the Texan rumbled. "So ah come on up."

Storme recalled hearing the vestibule door open and Susan's telling him that they were going to the top floor, rear.

"Quite a climb, isn't it?" Storme said.

Did Carroll's not coming right on up after him mean he was unaware of the Dorgan mob's interest in the Castles? Likely. He was, after all, an out-of-towner, probably imported for the single job of murder.

"Okay," he sighed, trying it out "Let's get going."

But Cal Carroll shook his head. "No need to go anywhere," he said. "I can give yuh what I've got for yuh right here."

"The devil you can!" Ted Storme grunted, bunching muscles for a struggle he had no chance of winning but which might make enough noise to arouse the house and so bring at least temporary safety for Susan and her mother. "You—"

Once more breath caught in his throat. Carroll had stepped aside and a girl was coming in through the door ahead of him, her honey-hued short hair tousled, her violet eyes drowsy, her bright blue velvet wrap parted on a white shimmer of satin.

"This is Mimi," the Texan said, pushing the door shut.

Storme's mouth twisted. "Brought a witness along so you can be sure of collecting?"

"Collectin'?" The big man looked puzzled. "For what?"

"The job you came here to do, of course."

"I don't get yuh."

"I do, Cal." The girl put a hand on his arm. "He thinks the same about you that Jock and I did, like I told you in the cab. He thinks Dorgan hired you to kill him."

"Jumpin' Jehoshaphat! I clean forgot," Carroll chuckled. "Shucks, son. I never heard of this Dorgan maverick till Mimi here told me about him, and as for gunnin' for yuh, I ain't had a shootin' iron on me for more years than you're old."

"No? Then what was it you put your hand on in your pocket when you invited me to walk out of the Biarritz with you?"

"In my ... Leapin' bullfrogs! So that's why yuh slugged me. Here!" The Texan's hand went into that pocket, came out with something it thrust at Storme. "This is what I've been huntin' yuh for ten months to give yuh."

It was an oval piece of porcelain not quite big enough to cover a man's palm. Its edges were chipped and the colors in which a young woman's face had been painted on it were faded, but the eyes that looked out from under the piled-up pompadour of a bygone era were wistful, the mouth sad and sweet.

"She looks like you," Mimi said.

"My mother." Ted Storme murmured, the hand that closed over the miniature trembling a bit. "Where did you get this, Cal Carroll?"

"She gave it to me the day she told me she'd decided between me and my best friend." New lines seamed the older man's leathery skin and his eyes were bleak as his voice. "That night I shook foot loose from where I figgered I wasn't wanted any more, bein' that kind of fool, and lost track of 'em. Long afterward I cashed in big, but I found out there was one thing I couldn't buy with money, and that was the only thing I wanted—somebody that belonged to me and me to them. I started out to backtrack 'em and found out—"

"Skip it," Storme snapped. "What you found out is my business and no one's else." But some of the hardness had gone out of his tone and his expression. "What I want to know, right now, is why you didn't tell me all this at the Biarritz bar instead of—"

Carroll laughed whole-heartedly.

"Wranglin' yuh into that fool bet?" he said. "I wasn't none too shore yuh was the Ted Storme I hoped yuh was, and that was the only way I picked to check. When yuh turned yore back on that fly like it was two bits yuh had ridin' on it instead of a thousand iron men, I knew ah'd come to the end of the long trail." Carroll chuckled reminiscently. "That minute I could have been standin' in front of Peg Dillon's honkytonk watchin' Rod—watchin' yore pa stake a hundred-thousand-barrel oil well on a scrap between a doodlebug and three ants and never turn a hair when he lost."

"He told me that story once." Storme was at last convinced the bronzed out-lander was what he said he was. "But you must know hundreds about him that I've never heard." His gray look drifted to the bedroom's half-closed door. "They'll have to wait, though, till—" He checked, slid an arched-brow glance to Mimi and away again.

Carroll caught it. "The lady's all right, Ted. If it wasn't for her, might be neither of us would be here. She saw that Foster doodlebug trail us out of that honkytonk and run out in front."

"She's the girl in white who sent the policeman into the parking lot?"

"And has been havin' an all-fired rough time of it ever since. This Dorgan ranny got hold of her."

"Dorgan wasn't so bad," the girl protested. "It was Foster and Bert Judson and that awful Judge Lee."

Storme's nostrils pinched. "You were with Feet Dorgan's party?"

"Not at first. I went there with Jock Haddon, but afterward I was at their table."

"I want to talk to you." Excitement pulsed in Ted Storme's voice, repressed but electric. "You're coming along to my place with ... Excuse me."

He whirled, thudded heavy-heeled into the bedroom. Viola Castle was up, supporting herself by a hand on the bed's footboard, her flaming hair neat, orange-red rouge livid on her ashen lips.

"You heard?" he flung at her.

"Yes, Ted. They sound all right."

"This mess may be working out better than we had any reason to hope. Hey, look. You can't make it down all those stairs, the state you're in. I'll have to carry you."

"Will you, Ted? I—I think I'll like that."

Her frail body was no weight at all in his arms. Hers went around his neck and her cheek nestled against his with a child's sigh of contentment. But Susan was troubled.

"What about Gram, Ted? You promised you'd bring her home to us."

"That I did, honey, and I'm beginning to hope now that I may be able to keep that promise."

It was Carroll's turn to look bewildered when they came out into the kitchen, Storme carrying a woman in green pajamas with a shabby coat thrown over them, a little girl lugging a valise almost as big as herself.

"No time to explain now, Cal," Storme said. "I'll tell you about it in the car. Grab that bag and come along."

"Yuh're Rod Storme's son, all right," the Texan chuckled as they started out and down the stairs. "That kind of sing-in' note in yore voice. He used to get it, just like that, when he was on the prod. 'Come along, Cal,' he'd say, his eyes as gray and hard as diamond bits. 'Come along. We got a job to do.'"

AL CARROLL sat with Mimi and Ted Storme in the gambler's almost monkishly ascetic living room. The sleep of exhaustion had overtaken Susan even before they had reached here and they had persuaded her mother to lie down with her in the bedroom.

"Two minutes after this Ashton Lee gets to that police station, I was wonderin' if they wasn't goin' to jug me for the crime of bein' robbed," Cal was saying. "Shucks, I says. Give me back my roll and I'll call it a day. Lee shakes hands all around and beats it out in such a tearin' hurry he don't even wait for Foster, and that doodlebug grabs a cab and takes out after him, so I got to wait till another one comes along."

"Lee got back to the Biarritz in time to walk in on Jennie Wrenn four or five minutes after Dorgan was shot," Storme said. "But I'd like to know how much earlier he got there."

"Don't tell me yuh're figgerin' he may be the one done the shootin'."

"Well, think it over. We can discard any theory that some enemy of Dorgan's just happened to be prowling around in the lot behind the dressing room and just happened to see him through that lighted window. The killer must be someone who knew Dorgan had gone backstage, and where. And look at Lee's behavior when he walked in there. He showed no surprise at finding Dorgan a corpse but went right at the old lady, foisting on her a self-defense plea that would avert suspicion from the real murderer and at the same time give him a lever with which to extract from her or her daughter a lead to the seventy-five thousand dollars which incidentally, is motive enough for any killing."

"Look, Mr. Storme." Mimi leaned forward eagerly. "Judge Lee didn't know Dorgan was going backstage till just before he went back there himself. I know, because he asked me where he was, and that must have been right the very minute Dorgan was being shot."

"Was it?" Storme's fingers drummed on the arm of his chair. "Mimi—do you remember the music ending with a single saxophone phrase that sounded like, 'That's All'?"

The girl's effort to recall screwed up her pert features till she resembled some pigtailed tad in a classroom.

"I don't... oh, yes, now I remember. There was just that one sweet sax singing, 'That's All-ll.'"

"Good. Now was that before or after Lee showed up?"

"Before. I'm sure it was before. Bert Judson was just drinking his last glass of champagne and then he passed out, but the people were clapping and yelling. I almost cried because T was afraid they'd wake him up, but they didn't and I started to get up, and just then Judge Lee was there, looking down at me through those awful glasses."

"That ties it up." Storme looked triumphant. "I heard that saxophone too, a half-second after the shot and I'd had time to get into the room and talk with Jennie Wrenn before Lee appeared."

Carroll seemed nuzzled. "Just what does that prove. Ted?"

"That he had time to establish an alibi. Look. He and Dorgan must have planned to talk to the old lady together, before he went to the police station to fix things for Foster. He rushed back as soon as he could, but instead of coming in through the front entrance he went backstage. Remember, he still had his coat on when he talked to Mimi and he'd have had a tough time getting past the checkroom girls that way. He drove into the parking lot and went around in back of the casino, spied Dorgan where he knew he would be and blasted him. He threw his gun into the room, and dived into the Biarritz through that same fire exit we came out of."

"Gee, Mr. Storme!" Mimi exclaimed. "You're wonderful. The only one I could think it might have been was Norma."

"Norma?"

"The brunette I told you about, the girl Dorgan told she might be cracking wise just once too often. Even I was scared the way he looked at her, almost as scared as Jock was when he heard Dorgan say about him, 'That phony's going to find out he's made one wrong play too many,' but Norma didn't turn a hair. She was burned up, though, I could tell that. And then she went to the powder room and never came back. And the way her bag bumped against the table, I was sure she might have a gun in it."

Carroll chuckled. "Don't I recall yore sayin', Ted, that the murder gun was little and pearl-handled? A woman's weapon."

"Or the kind a man might carry if he didn't want the fit of his dress clothes spoiled by a bulge."

"Mebbe. But Lee wasn't wearin' dress clothes."

STORM acknowledged that to be true. "Nevertheless," he

insisted stubbornly, "this murder—the shot from the dark,

the way Susan's grandmother was framed for it—isn't the act

of a jealous woman or even a frightened one. It's the work of a

cowardly rat, and that description fits Ashton Lee. With ten

times Feet Dorgan's brains he played second fiddle to him for

years. He cooked up all the ingenious rackets for which the

Dorgan mob is notorious and was content to take the crumbs Feet

handed him. Why? Because he was terrified of Dorgan. He was

afraid with every cowardly fibre of his rotten soul of Dorgan's

ways of beating down opposition, his ways of extracting

information."

He pulled in a breath, gray eyes glowing. "By this time Feet Dorgan's on a slab in the morgue, Jennie Wrenn is in a cell, and Ashton Lee is at home. I'm going to talk to Lee tonight. And I'll bet you the thousand dollars I won from you, and a thousand more, that I'll extract from him the information I'm after."

Mimi's chair fell over as she came up out of it.

"You're not—" Her fingers were at her mouth, her face greenish. "You're not going to burn his feet!"

"What do you think?" Storme's nostril's flared, his eyes were gray agate, and his mouth straight-lined, grim. "Do you think I'd stop at that?"

The girl stared at him horror-stricken, but abruptly Carroll was chuckling.

"Got yuh, Ted. Calm down, gal. He's just a-goin' to run a whangaroo on him. Laughin' hyenas, son, I shore would admire to watch yuh in a good hot game of no limit poker."

"You'll get the chance to tomorrow night—if I'm still around. Even rats are dangerous when they're cornered." Storme came lithely erect. "I'm going to ask you to stay here, Cal, and keep an eye on Susan and her mother. Mimi, I'll drop you wherever you say."

"Hold on." Carroll lifted to his feet. "Where do yuh think yuh're a-headin'?"

"To Lee's apartment up on Fifty-first street. That's dangerous, I know, but I can't bring him here, not with the Castles here, and there's no other place I can find at this hour where I can be sure of not being interrupted."

"Yes there is, Mr. Storme." Mimi was herself again. "I live alone in an old-fashioned flat with thick walls you can't hear anything through. You're welcome to use that if you want to."

"Sounds like just what the doctor ordered, but I hate to drag you into this."

"I'm in it already, ain't I?" Her pointed little chin seemed suddenly to take on new firmness. "You're going to use my apartment."

"Okay. Where is it?"

"East Eighth Street. Two-twenty-one. The ground floor, on the right as you go in."

"Check."

Storme strode to the phone on a small desk between two monkscloth-draped windows, and dialed a number. The ringing signal's burr was cut off by an irritated rasp.

"Storme calling," the other two heard him say. "Ted Storme. I know it's four-thirty in the morning, but you want to see me tonight."

The watching two saw a grim smile lick his tight gambler's mask.

"I said you want to see me, Judge Lee. That is, you do if you want to beat Feet Dorgan to the seventy-five grand Ben Castle cached five years ago."

Mimi was startled. "Dorgan's dead," she whispered. "Why does he say that?"

Carroll spread his hands. "Dunno, unless he's got some reason for wantin' to know has it been on the radio yet."

Evidently it had not, for Storme was saying, "I'll be hanged if I'll split it with a guy who's put his hoods on me to burn me down, but I can't get at it without one of you helping, so you're in luck." And after a pause, "Like the devil I'll come there! You're coming to me, Lee. Alone ... Of course you don't know where I live, and you're not finding out now. You'll meet me at two-twenty-one East Eighth Street in half an hour. The ground floor, right. Walk right in. The door will be unlatched."

Storme dropped the instrument into its cradle, turned. "Okay, Mimi. Let's have the key."

She snapped open the rhinestone-studded little envelope strapped to her wrist, fumbled in it, then looked up, eyes widening in dismay. "I—I haven't got it. I gave it to Jock when we started out and he never gave it back!"

"That's nice. That's just fine."

"Oh, that isn't so bad. There's a way of opening my door without a key. But I'll have to go along and show you."

"I don't like that. You—" Storme caught himself. "It's only ten minutes from here. Can you drive a car?"

"No, I can't."

"Then this is what we'll do. Cal will come along and drive you back here after you've let me in. We'll have to take a chance on leaving those two alone here for twenty minutes. Let's go...."

AT THE turn of the century, the four-story, brownstone house where Mimi lived had been the home of some wealthy family. Now it had been cut up into small, furnished suites but it still preserved some of its ancient dignity. The entrance hall was wide and high-ceilinged, the dark mahogany staircase was baronial in its proportions.

Mimi led the men to a door deeply embrasured in a marble niche.

"A boy I used to know found out how to do this one time when we had a scrap and I locked him out. You push in on this loose part of the jamb, see, and down hard on the knob."

The door swung open silently, let them into a narrow, dark hall.

"Just a second," the girl whispered, "and I'll light up for you."

As she moved away, Ted Storme pressed the latch-button to hold the bolt back, pulled the door shut. There was a moment of tar-barrel blackness, a click. Yellow luminance struck from beyond the wall-comer that concealed Mimi. A low, startled scream came from within the unseen room.

"You've kept me waiting a long time."

It was a man's voice, blurred with drowsiness. "I fell asleep."

Storme relaxed as he heard Mimi's voice, not frightened but indignant.

"You've got a nerve, Jock Haddon, using my key to get in!"

"I had to, kid. I couldn't go home till I'd told you how sorry I am I acted like such a heel, back on Long Island."

"Get out of here, Jock. Get right out!"

"Give me a chance, honey. Please give me a chance to tell you. You can't blame me for going off my trolley with the rep Feet Dorgan has, and when I saw he'd nabbed you—gosh, Mimi! I clean lost my head. All I could think of was to pour a couple drinks down and then beat it out of there, but soon's I hit the sidewalk I got thinking how you've been so sweet to me and all, and what do I do the first sign of trouble? I ditch you."

"Listen, Jock—"

"You listen to me," the fellow pleaded. "Let me finish. I was still too scared to go back in there but I remembered I had your key so I grabbed a cab and come straight here."

"Straight here Haddon?" Storme asked, stalking into the stuffy room. "Are you sure of that?"

LOOD draining from his sensuous lips, the fellow in Mimi's apartment goggled at the sudden apparition. "Storme!" he squeezed from his dew-lapped throat, "Wh-hat are you doing here?"

"I'm asking the questions, Haddon."

Storme was past Mimi, standing rigid in the center of the room. "I asked you if you came straight here from the Biarritz bar, without making a detour."

"I don't know what you're driving at," Haddon said surlily.

"You lie." Storme advanced on him slowly, menacingly, and behind Storme Cal Carroll entered, slipped an arm around the girl's waist. "You know exactly what I'm driving at. You wouldn't be here if you didn't."

Jock Haddon backed from the slowly advancing, ominous figure. "Not after hearing what Dorgan said as he passed you with Mimi," Storme accused. The wall stopped Haddon and he flattened against it, yellowed cheeks quivering. "What was it again, Mimi?" Storme asked, not turning his head. "The exact words?"

The girl licked her lips.

"Tell him, sweetheart," Carroll rumbled. "Tell him."

"He—he said, 'That phony's going to find out he's made one wrong play too many.'"

"That's it," Storme sighed. "You heard him say that, Haddon. It meant to you that you were fingered for a rub-out because you'd let your girl try to save me from his torpedoes, and you were terrified. But you're not terrified any longer or you wouldn't have come here to whine your way back into Mimi's good graces. No. You'd be putting as much distance as you could between yourself and Feet Dorgan's torpedoes. Right?"

There wasn't any answer. There was no sound at all save Jock Haddon's hoarse, heavy breathing.

"Why did you have the courage to come here?" Storme's relentless inquisition was resumed. "Why are you no longer afraid of Feet Dorgan? I'll tell you. You know Dorgan is dead. That hasn't been put on the radio yet, so you couldn't know it if you'd come straight here from the Biarritz bar. I'll tell you how you know. Before you left the bar you saw him go backstage and when you left it you went around in back of the casino. Standing there in the dark, you saw him come into a lighted dressing room and you shot him through the window and threw your gun into that room to frame Jennie Wrenn with the killing."

"You devil!" Jock Haddon squealed. "You were watching me."

Cal Carroll swore softly and Mimi whimpered, but Ted Storme's expression was as granitic as before.

"No, Haddon, I wasn't watching you. But that was a rat's crime and you're a cowardly rat, and cornered rats can be vicious. I realized that Dorgan's threat might have terrified you beyond terror, might have given you enough of the courage of desperation to grab the opportunity to strike back at him. But that kind of courage doesn't last, so I gambled that if I accused you of the crime you wouldn't have nerve enough to deny it."