RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

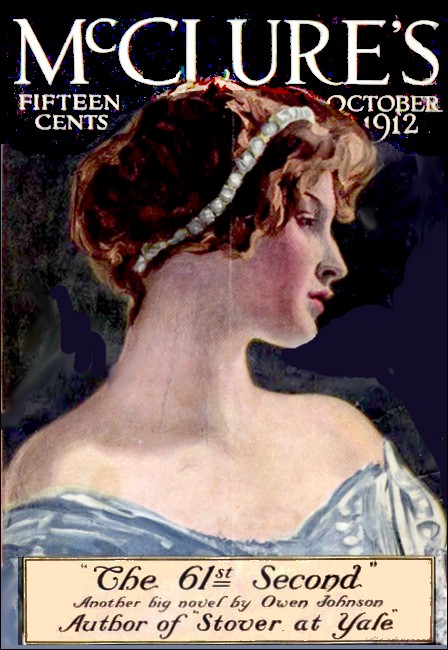

McClures, October 1912, with "The Mystery of the Double Eagles"

In the 1910's and 1920's American periodicals published numerous articles and stories by and about "America's Sherlock Holmes"—William John Burns (1861-1932), the detective and Secret Service agent who founded Burns Detective Agency and served as head of the FBI from 1921 to 1924. (See Wikipedia).

Arthur B. Reeve's contributions to the "Burns opus" include the following articles in the series "Great Cases of Detective Burns," published by the monthly magazine McClures in 1911-1913.

• "The Mystery of the Double Eagles," McClure's, Oct 1912

• "The Mysterious Counterfeiter," McClure's, Feb 1913

• "The Conspirators," McClure's, Mar 1913

The source file used to make the RGL edition of "The Mystery of the Double Eagles" contains several illustrations by William Oberhardt (1882-1958). These are not in the public domain and have been omitted.

—Roy Glashan, 24 April 2020

Note: Names, dates, and places are, for obvious reasons, either changed, concealed or omitted in this amazing revelation of how William J. Burns thwarted one of the cleverest crooks who ever tried to beat the government at its own game of guarding the millions of dollars in one of the large branch mints.

"THIRTY thousand dollar shortage discovered at the mint. Require ablest and best talent in the government service."

Never had the Secretary of the Treasury received a more alarming message than was flashed to him some ten years ago from the Director of the Mint himself. Consider for a moment what this simple telegram meant, coming from the Director at a time when he happened to be visiting one of the leading branch mints of the country.

From the massive granite and sandstone exterior of the great United States treasure-house to the minutest electrical device, the mint bespoke national security and national strength. It was supposed to represent the utmost progress in protective systems and mechanisms of the time—safety raised to the nth power.

The very external aspect of the mint seemed to say to the world that such a thing as theft was impossible. Huge doors proclaimed by their very ponderosity that it was their sole duty to guard the nation's treasure. Guards were stationed at every remotely vulnerable point. Apparently, nothing that human ingenuity could devise was lacking. From the moment the bullion entered on the various processes until it returned again to the outside world as gold coin, all sorts of delicate tests, checks, and balances had been devised to protect the government. No bank is so exact, no record is kept so clean, as in the United States money mills. Every ounce of metal, every penny of coin, must be accounted for in variably before the cashier of the mint can call his day's work done.

Consider this, also. Far from the street lay the great vaults where the mass of money was guarded with vigilance surpassing that bestowed on almost any other house of treasure. In this secret realm no visitor could enter. Millions were stacked ceiling-high where public curiosity could not see them, though it might dream futilely of the fabulous wealth behind the impregnable walls. Sentinels, mechanical as well as human, defended it at every avenue of approach. Not even the officials, except those immediately identified with that particular department of the mint, might be permitted to enter the proscribed zone.

Guarding the vaults were doors of armor-plate, swung on the latest kind of concealed hinges, locked by massive combination locks with time-lock attachments, proof against fire, against earthquake, against burglars. Against burglars? Six heavy bags of five thousand dollars each in double eagles were missing! There was the telegram, which the Secretary hurriedly turned over to the chief of the Secret Service:

"THIRTY THOUSAND DOLLAR SHORTAGE DISCOVERED AT MINT. REQUIRE ABLEST AND BEST TALENT IN THE GOVERNMENT SERVICE."

If that could happen once, what would prevent its happening again? If it could happen with thirty thousand, why not with three hundred thousand—with three million? The message was enough to send shivers up the spine of the Treasury Department, despite the torrid temperature of Washington at the close the fiscal year on June 30.

The chief of the Secret Service did not pause to read the message twice. There was just one man in the service at the time to whom all such difficult and knotty cases were turned over. He handed the telegram to Burns.

As he was whirled across the country the great detective spent the hours gazing at scenery that he did not see and turning the matter over in his mind. This much he knew. Some one trusted and high in the government employ itself had gone wrong. Fifteen hundred double eagles had been taken by some one on the inside. A black stain on the amazingly clean record of the mint in handling billions upon billions of dollars must be erased. Even before he arrived on the scene, Burns knew that this must prove a historic case.

BURNS began first what he calls his "secret investigation." When he arrived on the scene, he did not let a soul know who he was or why he was there until he had looked the ground over. He began by placing everybody who was in a position to know anything about the crime under suspicion, and then, by what is known as the "process of elimination," arriving at the possible suspects. He looked over the mint itself where the loss had occurred, investigated the methods of conducting business throughout the day, absorbed everything that might or might not prove evidential. After going over the mint thoroughly, he watched carefully for days how business was transacted, the number of clerks around, all sorts of things, until he might almost have been learning to run the mint himself.

Let us say, for the purposes of this story, that the superintendent of the mint was Mr. Atchison—"Mr. A." Atchison enjoyed the distinction, at the time, of being the ablest man who had ever held the position anywhere in the country. He was a large, fine-looking man, middle-aged, with a clear eye, a hearty voice, and a grip of the hand that left you with no doubt as to the power of the man behind it. He was known as a man of the greatest integrity and honor, extremely careful in the conduct of the affairs of the mint, a man who had shown great interest and intelligence in keeping up the good record of efficiency which had been set for the institution under him.

The chief clerk, "Mr. B.,"—or let us call him Mr. Braden,—was also a man of high character and standing in the community. He had come to the mint on the recommendation of some of the most influential men in that section of the country, had risen from the position of cashier until now he was assistant superintendent. He was a tall, rather spare, engaging chap, who by the sheer force of an attractive personality had won for himself membership in some exclusive clubs of the city, though he lived with his family in the suburbs. There was something about Braden of that solidity which one sees in the successful commuter—grave, but not aloof, capable, methodical, a man who had raised himself in the world and felt a pardonable pride in his position.

Mr. Colton,—or "Mr. C."—the cashier, also bore a reputation for the highest integrity. Colton was one of those men whom, if he had come to the ordinary man and had asked a little favor, the ordinary man would have been proud to accommodate. He would have felt a little flattered merely by having been asked. Colton was still young, ambitious, and eager to get ahead, and his position as a church member and a leading citizen in the section of the city where he lived stamped him as a "comer." He was respected highly by those who knew him, and his appointment as cashier a year before had been only what they expected.

In fact, all three, Atchison, Braden, and Colton, as well as the other employees, seemed impeccable. Many of the two hundred- odd employees had records of long and faithful service in this mint, some of them as high as forty or forty-five years. Men who had worked there from ten to thirty years were common among them.

And yet, when the Director of the Mint from Washington had been present for the government in its usual settlement with the various mints in the country, he had found that this particular branch mint showed a shortage of thirty thousand dollars.

More than that, investigation had disclosed the fact that the shortage was in the vault of the cashier. The Director had made absolutely sure that the cashier was actually short before he had wired the facts to the Secretary of the Treasury; there was no question about it. In this mint there were several large vaults, belonging to the assayer, the receiver, the coiner, the melter and refiner, and the cashier. It was Colton's vault alone that had been found to be short.

There was a time-lock on the vault, too, and no person had the combination except Colton. The only copy of it was in a sealed envelop, and that was to the custody of Atchison, to be used only in case of accident or the sudden death of the cashier. There was no evidence, as yet, to show whether or not the copy of the combination sealed in the envelop had ever been tampered with. Therefore the discovery of the shortage was all the more sensational.

Burns went over the life and habits of Colton, the cashier, with a microscope. Apparently he was a man of the best record and connections, just the sort one would pick out instinctively as the man through whose hands all the money that was to be paid in or out should go. All this time Colton betrayed not the slightest outward symptom of uneasiness, although he knew that the shortage had been found, and must have suspected that he was being watched. What a surprise it would have been to the community to know that everything in Colton's vault down at the mint was not correct!

There was another peculiar coincidence in the situation, too. For instance, on the day the shortage was discovered, it had happened, as it so often happens in such cases, that Colton had been ill, very suddenly taken with a bad case of tonsillitis. Thus it had been that the cashier was not present when the shortage was discovered. But the superintendent and the chief clerk had been there.

Many things about the mint interested Burns. For example, the system of accounts was somewhat intricate, in order to secure absolute accuracy in handling such large sums of money. Just to illustrate with what minuteness business was done, there were reports in weight in standard ounces of metal, its cost value and the nominal value of the coin made from it, the number of ounces being multiplied by the value of one ounce of metal at the time, worked out to the millionth of a cent. That was in order to arrive at the "seigniorage," the profit the government makes in coining metals.

All accounts of various departments ultimately went through one office, where they were compiled and sent to Washington daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly, and annually, according to the nature of the reports. Finallv, at the close of the fiscal year two officers were detailed by the Bureau of the Mint to examine the accounts, weigh the bullion, count the coin in hand, and report the results of this examination to the Bureau in Washington. Everything was done with scrupulous exactness and precision.

There was nothing of this mass of detail that escaped Burns in his hunt for the criminal who set these checks and balances in defiance. He noted everything, such as the "delivery" every morning, as it is called, when the coiner delivers to the superintendent the coin that has been made the day before in his department, which is then placed in the vault in the cashier's office. Representatives of the assay department, of the superintendent and of the coiner, had to be present at the "delivery." The coin had to be receipted for to the coiner, and brought in sacks on trucks to the cashier's room, where each sack was counted, and weighed in the presence of the three men, tied with a stout string, and sealed with a lead seal stamped with the superintendent's name, secured so that if the sack was tampered with it could be seen.

A glance at the conduct of a mint is a romantic revelation of a fairy world where gold and silver are the stock in trade, as in other more sordid businesses it is mere iron pig or bolts of cloth. For instance, a citizen with gold to sell, a miner perhaps, would go to the receiving-room. There he would find a long counter on which was a scoop into which he would dump his dust, nuggets, or old gold. Back of this counter he could see desks and tables, interspersed perhaps with trucks actually loaded with real gold bars, a fortune casually wheeled about like a sack of oats.

It is not a part of this particular story, though it is a romance in itself, bow the gold is carefully weighed in the weighing-room next to the receiving-room, the various processes through the laboratory of the assay department in the basement, the assay furnaces, the delicate scales and weights of the adjusters, the melting and refining department, the settling and silver reduction tanks, the ingot melting-room, the rolling-room with its long, gleaming strips of rolled gold, the annealing- furnaces, the coiner's department with its coin-presses, the milling- and reeding-machines, the weigh-room with its ingenious counting-boards—a long process, ending with the cashier's vault hiding its mystery of the missing double eagles. Mystery it was, too; for so carefully were all these processes carried out that, with a wastage allowed by law of one thousandth to the melter and only half that to the coiner, the infinitesimally small amount of only six or seven per cent of even this legal wastage occurred.

But it was in none of these departments that Burns knew he must look for the thief. Altogether, there were as many as seventeen watchmen, of whom twelve worked at night, eight on the inside and four on the outside. No clue to the mystery was coming from them,—at least at the start,—and Burns still was going alone and single-handed in his quiet study of the situation. Each watchman, he observed, had a certain station on the different floors and a specific round to make each half hour, ringing a bell to notify the man at the door that he had attended to his duty. Failure to ring the bell caused investigation. In certain rooms, such as the refinery, no watchman ever might go alone. They had to go in pairs. There was also a system of electric alarms throughout the building, so that everyone might be notified in case anything went wrong at any point. A word about the mint itself. It was a huge square building of granite and sandstone, with a long and impressive flight of steps leading up to the main door under its massive Grecian columns. On two sides of the building ran street-car lines.

It was the general lay-out of the interior of the building that, the more Burns pondered over it, proved to play a large part in the solution of the crime. Entering the front door, the visitor looked down a wide corridor before him, crossed at right angles at the end by a transverse corridor running the width of the building from right to left, after the manner of many large public buildings. Directly before him, at the far end of the main corridor, was the door of the cashier's office, the office being at the backof the building and extending from the center to the right wing, along the far side of the transverse corridor. It was in this right wing, at the back, that the cashier's vault which had been rifled was located.

To the right of the main corridor as one entered, in the front of the building, and consequently lying opposite the cashier's office along the transverse corridor, was the numismatist's room, where coins and medals were kept in a museum. To the left, as one entered this main corridor, was the office of the chief clerk, Braden, with a door leading into the main corridor, as well as another leading into the transverse corridor. This office extended from the front of the building to the transverse corridor. Next to and communicating with it was the office of the superintendent of the mint in the very left-hand front corner of the building, opening into the long transverse corridor.

Opposite these two offices, which occupied the entire front of this wing of the mint, and ranged along the other side of the transverse corridor, was the receiving-room at the extreme end, opposite the superintendent's office; the weighing-room, opposite the chief clerk's office; and then the cashier's department, extending through the other half of the back of the building. All three of these departments, the cashier's, the weighing, and the receiving, communicated with one another.

BURNS' first and most natural query had been: Was it possible to manipulate the books? That proved to be easy to settle, in spite of the intricate system. And it was settled quickly in the negative. No, the books were perfect. According to Colton's own accounts, there was a thirty-thousand-dollar shortage!

Even the cashier himself could not conceal, or had not concealed, the fact that there ought to be thirty thousand dollars more in gold pieces in the vault than there actually was. Blazoned in damning figures on the books themselves was the mystery of the missing double eagles.

Here Burns began his clear and clever reasoning. With an instinct that led him unerringly to the heart of the matter, he quickly came to the conclusion that it was absolutely impossible for anyone to have taken the money in business hours, during the day. The next question was: If the money had not been taken during the day, how was it possible to manipulate the time-lock after the cashier's vault had once been closed?

Burns then tackled the time-lock on the cashier's vault, and he soon discovered that he was on the right trail. Someone had filed the dog-locking device so that it could be operated by one who knew the combination, hidden in Colton's mind and sealed in the superintendent's envelope. It made no difference whether the time-lock was set or not. It was out of business. When it was apparently set it really did not lock the combination. No one ever discovered it, for no one ever tried to open it out of hours, except the thief.

The time-lock was taken to a jeweler, and later a government expert—one of the best in the country—was summoned from Washington. Burns and the expert found that the thief had bent a little arm in the time-lock in such a way that it did not strike the proper part to lock the tumblers. The arm had been bent first with the idea of rendering the time-lock inoperative, so that the thief might return at night, work the combination, and so get into the vault. Later, apparently, he had bent the arm farther down in order to be able to work the combination after two days, say on Sunday or a holiday. But he had cracked the nickel, as Burns and the expert discovered, had found that filing the dog-locking device was sufficient, and had bent the arm back again.

Next Burns devoted his attention to the vault itself. He found that at this time and for several months it had been congested with money. All the stationary pigeonholes or receptacles for the sealed bags, each compartment holding a bag of gold with five thousand dollars in it,—in one section in fives, in another eagles, and in another double eagles,—were full. Therefore, in order to put more money into the vault, two trucks had been pushed up against the east side of it, entirely out of the way. Of course there was no likelihood of wanting to use the money on the trucks or in the pigeonholes back of them. There were plenty of other bags that could be readily got at for any usual demand. These trucks remained stationary until the final accounting, and, in all, some three million dollars accumulated on them.

In counting over the bags, keeping the amount on the trucks separate from the bags in the pigeonholes, the men who did the work found that the three million was intact. Some of the men who helped to carry out the gold remembered, however, six vacant holes near the floor, behind the place where the trucks generally stood. Burns was now getting closer and closer to the truth.

He had already learned from the superintendent how the shortage had been discovered when he and Braden had been counting the money in the vault the day Colton was sick.

Braden had just written down some figures when Atchison leaned over. "There is a shortage of thirty thousand here," said the superintendent keenly.

"No, I think not," replied Braden, continuing to figure; "or perhaps it is due to the cash drawer; or there may have been a mistake in the count."

"Not a bit of it, Braden," replied Atchison promptly. "That count is right."

Count and recount as they might, there was no straightening of it out. There was the mystery at the start, and that was as far as anybody had got when Burns arrived at this point. The money was gone—that was all there was to it. No one believed that it had been spirited away, but then, no one knew what to believe.

"I satisfied myself thoroughly," says Burns, "that it was not even possible to bring the money out into the cashier's office in the daytime, then hide it until night. Every afternoon, before the doors were closed, the cashier and the chief clerk counted every dollar, and, in the presence of the cashier, every day the O.K. of the chief clerk was placed on the cash."

Burns went out and took a turn or two up and down the street; then stood in the shadow of the high Doric columns, thoughtfully revolving the matter over and over in his mind. For it is his theory, in every important case, to put himself in the place of the thief. Point-blank he asked himself, "If I had access to this mint at night from the time of the chief clerk's O.K., and after the mint is closed, to midnight, what possible chance would I have to steal thirty thousand dollars?"

The more he thought of it, the clearer it became, until finally he put the case hypothetically this way: "In order to do that, it is necessary to have entrée to this mint at night under proper pretext, to have entrée to the cashier's office at night under proper pretext, to be able to carry a valise or suitcase in and out of the mint at night under proper pretext. If I had this entrée I could then go ahead. It would then be necessary to manipulate the time-lock in such a way as to render it inoperative. I should also have to know the combination of the vault.

"If that were all true, then I could come into the cashier's office at 4:30 p.m., when the clerks had all gone. At that minute the watchman on that floor, who is as regular as clockwork, has lighted the lights in the cashier's office and has left on his rounds, not to return for twenty-eight minutes. That would give me a chance to open the vault."

Burns then sauntered in and traced out the hypothetical course. Someone, he continued to reason, came in at half past four, opened the vault, took out one or two sacks,—never more, for they weighed nearly thirty pounds,—and carried them out. Then he hid them in a box-counter in the cashier's office under some empty coin-sacks.

Instead of going out to the main corridor by the natural way, he must have gone on through the weighing-room to the receiving- room. In this way he would be out of sight of the watchman who was always at the main door in the main corridor, looking right down to the cashier's office. In the receiving-room he would then have to climb a counter, and could leave by a door opening into the transverse corridor. Directly across from this door, only ten feet away, was the office of the superintendent. This office had a door opening into the office of the chief clerk. If the gold were hidden, it might be done up in some sort of package and carried out that night or the following day. Probably the thief returned at, say, eleven o'clock at night, when there was a shift of watchmen. He must come in, go to his office on a plausible pretext, get the two sacks hidden in the cashier's office, and in that fashion make his get-away.

This was clear and clever reasoning, and it told Burns much. But it did not catch any criminals—because, as you see, the route taken by the thief involved the offices of Atchison, Braden, and Colton, all three. Burns had his suspicions, and the reader probably has his. At any rate, Burns' were right. It was a question of building up the evidence.

BURNS was now ready to come out of cover and begin his "open investigation." Up to this time he had been lying low, but he had now reached a point where certain phases of the case could be inquired into only by his coming out. For instance, he had not yet even been introduced to Braden, though he had been watching everybody and everything in and about the mint.

"I have never met you, Mr. Burns," said Braden one day soon aiterward, "but I think 1 ought to introduce myself. I'm glad to know that you've been detailed on this case, for I've heard and read a great deal about you."

Burns shook hands, and as he did so he noted Braden's clear, steady gaze into his own eyes. And that is something for any man to do; for, if there is one thing above the many that impress you about Burns, it is those boring steel points of eyes of his which cut into your very soul like a bit and seem to strike home at what is lying hidden there.

"I'm satisfied," Braden added, "that you'll find the thief, and if there's anything I can do to aid you, command me."

"Thank you, Braden," returned Burns; "I'll be glad to call on you later."

It is always easier to pick criminals and pile up evidence in predigested detective stories than it is in real life. Burns had made up his mind into the open, but there were still some small matters that he did not quite fully see. So it wasn't long before he decided to take advantage of the chief clerk's considerate offer.

"You're the best-posted man in this mint on the conduct of the business and things in general," wheedled Burns, to start with. "Now, Braden, as man to man, give me the benefit for a moment of your intimate knowledge. Tell me, how do you yourself think it in reason possible for any person to steal that money? Of course, there must be some person whom you suspect. Who is it?"

For the first time Braden was reluctant to speak. It was quite obvious to Burns that he had his suspicions, and also his reluctance was quite as obvious.

"Yes," he parried; "but you know yourself, Mr. Burns, that it is a serious thing for one in my position to condemn a man on suspicion, and, and—well, I should hate to do it."

"But you must do it," urged Burns, with a becoming show of warmth; "it is your duty."

Braden still hesitated, but it was evident that a name was all but bursting from his lips. Burns pressed him. Finally, with reluctance, he whispered the name of the cashier.

"Yes—Colton," mused Burns. "There was nobody in a position to do it except the cashier. But then, Braden, can't you see the utter futility of anyone like Colton expecting to be able to get away with it? What puzzles me is how he could manage it."

"Well, I've figured out several ways. For instance, there are a number of large depositors who do a good deal of business with the mint. One concern alone does from $50,000 to $200,000 a year. There might be some mix-up there."

After going over the drafts and the action that had to be taken on them by the chief clerk himself, as well as each step in the delivery of the money, Burns readily convinced Braden how impossible it was for Colton to do anything in that way.

"Well, then, how about this?" suggested Braden, his reluctance all gone now. "The cashier, when he is filling a truck in the vault with his assistant,—you know, he is never alone,—could surreptitiously miscount the sacks when the other fellow was off guard, and place a couple of extra bags on the truck. Then, as it was going through the office, he might secretly shove off the sacks, hide them, and later get off with them."

"But there are too many clerks around," objected Burns. "No; you'll have to do better than that."

"Well, how about this?" pursued Braden, thoroughly warmed up to the detective job. "Why couldn't he have the other man stand in with him,—put on, say, two extra sacks,—and then later the two of them divide up?"

Burns picked that to pieces, too, until even Braden had to admit the folly of Colton's dreaming of such a thing. Then he began a little quizzing on his own account. "Braden," he asked casually, "while you were counting the cash with Colton every day, why did you fail to look behind the trucks in the vaults? It was your duty not to take for granted that everything was there. It was your duty to count all, all—not part, no matter what Colton said. It was your business to see whether the pigeonholes behind the trucks were filled or not. Now why didn't you discover the shortage before?"

The chief clerk shrugged his shoulders. "1 took it for granted that they were all there," he answered weakly.

Right here Burns stuck a pin. The failure to look back of the trucks each day showed conclusively one of two things: either someone was outrageously derelict, or he purposely avoided finding the abstraction of the bags.

"Why," continued Burns, "what was the use of counting at all, if you overlooked half a million dollars or so hidden by the two trucks?"

"I didn't think it was necessary to look behind there," reiterated Braden more strongly. "I trusted Colton, and—oh, say, here's another possibility that has occurred to me. Why couldn't he have taken out two sacks, put the money on the cash- table in the vault, and then carried in something—anything, potatoes maybe—to fill up the empty sack before he put it back?"

"Impossible," ejaculated Burns skeptically. "How could he seal it?"

"Well," exclaimed Braden, somewhat nettled, "if you explode all my theories, I must confess I have no others to offer. I can't see how else could have done it. What's your own theory?"

Burns briefly outlined the case he had worked out.

"Impossible," interrupted Braden. "Why, the time-lock was on, Mr. Burns. He couldn't come back and open it. No; there are no other theories if you reject those I—"

"Think it over," cut in Burns, turning on his heel.

Burns stuck to his theory, too. He went to the men who, covering the period from the previous settlement to the discovery of the shortage, had been on watch. He asked them if they had ever seen any one there after the mint was closed. Some said they never had; others said they had on a few occasions. But all said that whomever they saw never carried a package, a valise, or a suitcase in or out after the mint was closed.

If that were true, then the whole theory that Burns was working up fell to the ground. The men went further and assured him that every package had to be shown to the man at the door. That also exploded the theory. But Burns did not believe it was true.

He took the men one at a time, and finally found that there was really only one whom he knew must have been the man on duty when the package or grip, whatever it was, was carried in and out. He took this man aside, and told him directly, bringing his cutting eyes into play again, that he suspected him of being part of the conspiracy to loot the mint. That was startling news to the doorman, and he did some quick thinking as well as vigorous asserting of his innocence. Burns told him that he had stated positively that no one had ever gone in or out with a grip, whereas Burns knew better—that some one had.

The watchman looked at him blankly; then a new light seemed to come over his face. There was no fake about it. He had forgotten, but now he actually remembered that an officer of the mint several months before had brought a suitcase one night after seven o'clock, and, with his office door open, had disrobed almost in the presence of the watchman, put on a dress suit, and had gone out to attend a reception. About eleven o'clock he had returned, taken off the suit, put it back in the suitcase, and taken it away with him. This happened on several occasions. But he had taken nothing out except the suit. The man was sure of that. So was Burns, up to a point.

This, then, was an important clue. The man had taken nothing at all until, say, the last few times. It was all cleverly done to "educate" the watchman to see him going in and out with a suitcase at night.

THE trail was now hot. One day Burns went to the cashier himself. "Colton," he demanded, without any warning, "who changed that lock on the vault?"

"Why," replied Colton thoughtfully, "when I became cashier about a year ago the combination had to be changed. It must have been done by a locksmith."

At once Burns began to trace this assertion down through the labyrinth of fact. It didn't take him long to find that the accounts showed no charge whatever for the services of a locksmith.

Burns confronted the cashier with this fact from his own records. Then Colton said he had made a mistake. He now recalled that when he had assumed his duties, he had asked the chief clerk, whom he succeeded as cashier, what to do about the combination.

"Oh," said Braden, "there isn't any need of getting a locksmith; I'll help you change it."

Together the cashier and the chief clerk had set the combination. Burns made the cashier show him exactly how he claimed it was done.

It seemed that there were four numbers in the combination, the first and last being fixtures, so that only two had to be set by Colton himself. According to Colton, Braden had stood in a certain position while he had tried to fix the second number after the first fixture. As often as he tried, he failed. Something was wrong with the tumblers. At last Braden had said he thought he saw what was wrong.

"Upset it, Colton," he had ordered, "and begin all over again. I'll tell you when the tumblers catch. First the fixture. There.

Now try again. Four turns to the right, remember, and set it wherever it happens to be. There—slowly—no—whoa!—a little more, there. The tumblers catch all right. Set that number down, whatever it is. Now twice the other way—and set it at just whatever it is when the tumblers catch—there."

Burns continued to ponder the matter. Suddenly the truth flashed on him. There were only two numbers to be set, since the first and last were fixtures. In some way, Braden had made scratches on the back of the lock which would indicate to one who had made them where the combination was being set by someone else on the other side. One scratch was at twelve, the other at ten. Twelve and ten were the second and third numbers in Colton's combination. From the position which Colton said Braden had assumed, Burns saw that Braden could manipulate the tumblers so that whatever number Colton set the combination at would prove a failure. Then, after Colton had tried again and again and failed, Braden had worked the scheme of telling him that the tumblers caught at the twelve and then at the ten. They caught because Braden did not manipulate them at those points. Braden had forced a card on Colton!

"Now," reasoned Burns, "that filing of the dog-locking device could all have been done a year ago, when Braden himself was cashier. Therefore Colton's story is quite plausible, and he might not have noticed it, since he would have no occasion, if he were honest, to discover that the time-lock was inoperative after he thought he set it."

More than that, it was found that Braden had often been found, when he was cashier, working over the lock, which he always said was out of order.

Piecing his case together bit by bit like a mosaic, Burns next investigated to determine who had arranged that the watchman should be so occupied that his place was vacant for twenty-eight minutes in the afternoon when he started on his rounds to light the gas. The superintendent told him that Braden had said that by a rearrangement they could do with one less watchman. The scheme seemed so well worked out that Atchison had said it was all right.

The mystery was gradually clearing itself up. Braden had first filed the dog-locking device, then he had worked Colton for the combination. The next step was to "educate" the watchman to see him go in and out at night with a suitcase. There was still no chance to get away with anything unless the vault was congested. Braden had accomplished this as cleverly as he had the shifting of the watchman. "Mr. Atchison," he had said, "of what use is it to unseal and seal the other vaults every time we have a little gold to put in or take out? Now, if we take two trucks and put the extra money on them we shall no longer have to break the seal of another vault, but we can put the trucks right into the cashier's vault."

Thus the complete case finally unraveled itself. Step by step, Braden had been working toward a robbery since he himself had been cashier; step by step he had been weaving a web about Colton which should involve him. It was a diabolically clever scheme. It squared with the facts so far. Would it square with new facts?

Patiently Burns set about ferreting out new facts. Hr questioned every man who might by any possibility have seen anything. From start to finish he found that he had erected an iron-bound, rock-foundationed cae. Colton was innocent.

One night, several months before, four watchmen just going on duty happened to be sitting in the main corridor, with the regular man at his accustomed position at the door. One of them recalled that another was reading from the newspaper an account of the St. Patrick's Day celebration.

"What's that noise I hear in the cashier's room?" he asked.

"It's the chief clerk," replied one of the others.

A moment or two later he thought he heard a noise in the weighing-room.

"What's that?" he asked quickly again.

"Don't know," replied a third. "Keep still. I want to hear about the parade. Go on."

The man who was reading resumed. Just then, from his place near the corner of the main corridor and the transverse corridor, where he was sitting with his chair tilted back against the wall, the first watchman who had heard the noises cAaught a fleeting diagonal glimpse down the transverse corridor, as of someone crossing it. A few minutes later Braden came out of his office with a suitcase. He was white as a ghost. He had had a big scare thrown into him by the presence of five watchmen.

The man on the tilted chair thought the man at the door would stop him. But he didn't; instead he merely nodded. He had been "educated."

Another link in the chain Burns was laboriously forging. Out on the big stone steps, that night, Braden had chanced upon one of the outside watchmen. The man had hurried up to help him with his suitcase. "No, no, no." insisted Braden. The man was equally insistent. But Braden won, and jumped on a street-car going to the ferry.

More than that, on the street-car he had had a dispute with the conductor, who wanted to shift the suitcase out of the aisle. The conductor, having once before had words with him, took out a note-book secretly and jotted down in it the date and time with the words, "That crank from the mint," in case the "crank" should lodge a complaint with the company.

At the ferry another watchman, going home, noticed him carrying a suitcase wrapped about with a newspaper as if to hide something bulging. Even the conductor on the other side of the ferry remembered Braden's taking a car home.

Even more than that, it was found that, a couple of weeks before the annual counting of the money, Braden had taken his family several hundred miles on a visit, while he had gone by another route, quite evidently for the purpose of hiding the money.

Here was a chain of evidence whose every link clanked ominously as Burns had forged it since that offer of assistance. You recall that offer of Braden's? "It is my theory," says Burns, "that every criminal leaves a track. This fellow left deep furrows. Any man who is a student of criminology and human nature could have at once detected that Braden had overshot the mark. He looked too straight. He was too persevering in it. It was so marked. I was satisfied beyond question that he had come to me for a purpose. But he had put his foot in it. Then, again, when I asked him of his suspicions, he acted as if he told the name of the cashier reluctantly. Any person sufficiently versed in the investigation and detection of crime could have seen that he had no compunction of conscience whatever. He promptly named the cashier as soon as it was decent to do so, and I apparently acquiesced."

The case was complete. Burns was ready to act.

One day, when he knew Braden was at his club, he called.

Tell him I can't come out now," Braden sent out.

"Go back and tell Mr. Braden it is very important," Burns ordered the boy.

"He says he is sorry," reported the boy, "but he's in a conference."

Burns entered. There was Braden sitting, smoking and joking, with a number of prominent men of the city. He jumped up apologetically. "Beg pardon, Mr. Burns," he said, "but I didn't understand it was you."

"Well, Braden," whispered Burns, drawing him aside, "I've got the thief."

"You have? Good! Let me congratulate you, old man. Never doubted you'd do it. When did you get him?"

"Just now."

"Indeed? Who is he?"

"You."

THIS is the point where a short-story detective quits with the capture of the real criminal and the vindication of the innocent suspected man. But Burns was just beginning.

"Say, you're joking," protested Braden coolly.

"Not much," reiterated Burns sharply.

"You saw those men in there?" hissed Braden, changing his tactics. "They are some of the most powerful fellows in the city. They can make and unmake people. I can make you lose your job, Burns."

"All right; go ahead, Braden," persisted Burns doggedly. "But you're going with me first."

"You're making a big mistake."

"I'll take a chance on that, but I'll take you, too."

Then, for two days and two nights, there was a battle of wits in Burns' room in the hotel, where he took Braden a virtual prisoner.

It was a dramatic situation, these two men facing each other, with the heart of a great city pulsing about them, and yet alone, each straining at the last ounce of mental power in him. They were "sitting in" a game in which the stakes were Braden's freedom and reputation against justice. Burns knew that, even with a plain open-and-shut case, there were so many slips in a jury trial that only overwhelming evidence would do.

Each eyed the other's every move keenly. Cool and calm and conscious of his power, Burns played his cards. Braden, desperate, deliberate, stood pat. Nor was it an ordinary player who faced Burns. Braden kept his head. He smoked sparingly, drank lightly, and slept almost with one eye literally open, weighing every word of his opponent, watching every action of the detective, and asking himself over and over and over again, "I wonder just how much he does know?"

For Burns had been busy flashing a dark lantern on the shady spots in the man's life.

Now, in that hydraulic fashion of his, which has squeezed many a confession out of the most recalcitrant of criminals by the sheer weight of the evidence, he was adding pound after pound of pressure.

He went over the whole case, from the discovery of the shortage, through the various steps down to the now cleared up mystery of the missing double eagles. Braden denied it without the flicker of an eyelash.

Burns drew two cards. He told Braden how he had unearthed the fact that twice before he had been using money that belonged to the government, how he had worked the schemes, how he had covered them up, and how, twice, he had had to get up out of a sick-bed to make good on these "loans" and prevent discovery.

Still Braden did not throw down his cards. Burns finessed. He told him how he had even worked out a scheme to defraud the government, involving checks on the New York sub-treasury. He told him how he had imitated the signature of Atchison so perfectly that even Atchison could not have picked a flaw in it. He told him how the scheme had fallen through because Braden could find no one whom he could trust in New York to work the scheme from that end.

Hour after hour, Burns increased the hydraulic pressure of the facts he had dug out. Would Braden be able to resist?

Burns went back into the man's life before he had come to the mint. He told Braden that he had also been a defaulter in one position, that he had hypothecated warehouse receipts in another. He told him how no one had dared prosecute him on the latter two charges.

All this and more he rammed into Braden. But at the end of the forty-eight hours of mental dueling in the hotel room Braden was still standing pat.

Yet there is nothing of the bloodhound about Burns after he has run his man to cover. "I see what's the matter with you," he finally remarked to Braden, never raising his voice. "You're afraid to talk frankly because you think I'll trick you into an admission. Now, I'll agree on my word as a gentleman that anything said between us will not be used against you. We can discuss your case freely."

There could be no doubt that Braden was cornered at last. He was beaten, baffled, betrayed by the facts at every point, weak, nervous, yet still game.

At the end of the second night he asked desperately: "If I give back the thirty thousand, will you let me go free?"

Burns had begun to feel for the man in his power. But there are "some things no fellow can do."

"No," he answered; "you'll have to go to court and plead guilty. But I'll get the Department of Justice not to press the two minor cases where you misused government funds, since you afterwards made restitution."

Braden was visibly weakening.

Just then a Secret Service man came in with an evening paper. In spreading headlines it told of the confession of a man who had stolen $228,000 in gold bars from a smelting company. The paper seemed to be roasting the man, not for the theft, but for confessing.

Braden read it attentively.

"That's what they'd say about me," he remarked thoughtfully, as he laid the paper down. "No; do your worst—I won't say another word."

With that, Braden closed up like a clam.

So began a long battle for justice against this clever crook. First he was convicted and sentenced for two years each, on the two minor charges of misusing government funds. But for the theft of the thirty thousand dollars he was tried, and after a bitter fight the jury disagreed. Again he was tried, and again the jury disagreed. Braden's "most powerful fellows in the city" were powerful enough for that.

It was after the second failure to secure a conviction that Burns returned to Washington. James M. Beck, who as federal District Attorney in Philadelphia had prosecuted the hundred- dollar Monroe-head counterfeit case, was Assistant Attorney- General then, and on that day was acting Attorney-General.

"It's too bad we didn't get a conviction," remarked Mr. Beck.

"Well," explained Burns ruefully, "you see, the government is too penurious in conducting its cases to watch the jury. If we had had money enough to keep off the jury-fixers we would have won."

Mr. Beck simply reached for his pen.

"I'll make out an order for the money," he said. "You go back there; we'll hire new lawyers as special district attorneys and keep the jury safe this time."

Then began a final battle royal with the jury-fixers and the corrupt attorneys who were fighting for Braden and the gang with which he was friendly. By the way, his own attorney was afterward sentenced for fourteen years in another matter, and several of the "big fellows who could make and unmake people" have also been unmade themselves.

Braden got nine years altogether. The debacle of this clever crook was complete. The mint breathed easier. Burns had cleared up and fought to a finish the alarming mystery of the missing double eagles.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.