RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vitage travel poster

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vitage travel poster

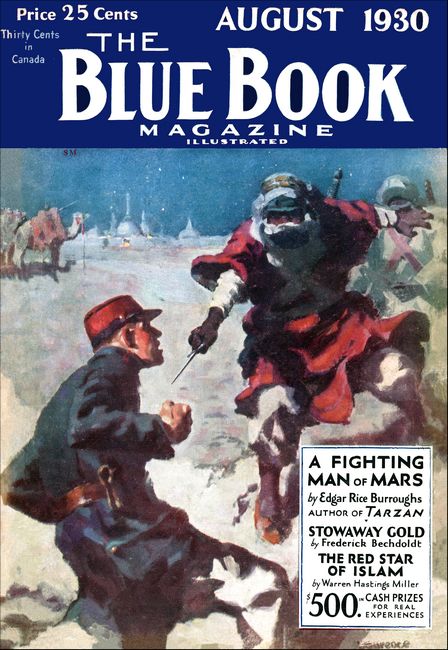

The Blue Book Magaine, August 1930, with "Desert Gesture"

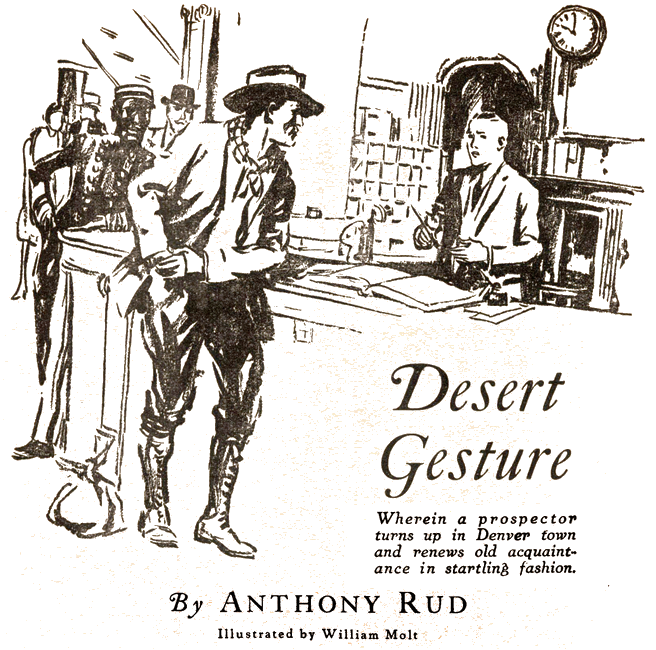

MOJAVE paid no seeming heed to the curious glances and half smiles vouchsafed him on his eastward train journey to Denver. His desert-seared countenance could not unbuckle a blush, no matter how hard the inside of him tried to produce that symptom of embarrassment. Yet when he left the train, he dragged a neat pack—his only luggage—back of him down the aisle of the Pullman, instead of strapping it across his capable shoulders.

Out in the steamy air of the train-shed, cool as yet with early morning, he looked about him calmly before going ahead. His eyes, which some Denverites would have called the color of London smoke—or others likened to a break in the steel of a prospector's drill—took in the scene without a hint of fluster. He never before had glimpsed a red-cap, but now he saw them busy with the luggage of the other passengers. He watched a coin change hands. He understood. He spoke to one, holding up a silver dollar as if to flip it into the air from his thumb knuckle.

"Show me where to cache this for a while, an' then the way to a hotel," he commanded. "Can you catch?"

"I sho' can, boss!" exclaimed the surprised negro; and did. Then he lifted the pack, revising mightily his first-look opinion of the desert man.

Mojave Corlaes had passed through Denver once before, as a youth of fourteen—eighteen years before. That time he had sported cut-down and patched bib overalls, and had been barefooted, for the time had been summer. Now he wore a scuffed buckskin vest, a faded pink shirt which originally had been red, scuffed brown corduroys, run-over brogans which once had been tan, and a carefully brushed black felt, greenish around the band.

But there were other differences. These began to appear when the desk clerk at the outdated Rexford Hotel regarded this baggageless customer with a dubious air. "Cash in advance?" he questioned.

"All right, son," said Mojave, nodding. He brought out a roll of bills—a concession to portability he had made, on advice of the shrewd lawyer he had left back in Arizona—and dropped a sizeable one on the counter, then signed his name in a big, firm hand, on the register, while he waited for change. "No, I aint goin' up. Mebbe there'll be some packages come; send 'em up, will you?"

"Of course. Certainly, sir! Anything, more I can do to help out? The management always—"

"Knows its onions plumb from seeds to sets," the prospector finished for him. "Yeah, I reckon." The hint of a smile crept into the fine network of wrinkles about the smoky eyes. "It's all right, sonny. I know I look tough. This aint my town, though. I got some business that wont keep. First off an' right now I got to go to the Miners' and Traders' National Bank. Whereabouts might I find it?"

The clerks eyes swept upward to the yellowed face of an eight-day clock. "It doesn't open until nine—nearly two hours yet.. But it's—" He came out from behind the counter and led the way to a big bay window overlooking the sidewalk, giving minute directions. "If you want to deposit valuables in the meantime, however, the management provides—"

"That?" queried Mojave, jerking a thumb toward a small black-lacquered safe which reposed in the back wall above the level of the counter. He grinned, lifting the bottom flaps of his vest. Exposed then was the black wood butt of a special .38 revolver—with drop and balance gauged by some unknown genius, to the .45 frame—"the best shootin'-iron the world ever saw!"

FROM the hotel-man then, after a brief grin for a safe any

miner could drill out of a wall and walk away with in ten

minutes, Mojave secured two other addresses, and the directions

for getting to both places. He went first to the restaurant

address. And there he found a big place in the very heart of the

business district of Denver. But it was dark, locked. Outside, at

a window fronting the street, there was a tempting display of

pastry and other delectables. Also a menu card, "Flapjacks à

la Mojave—40c." Above the two-page printed item was a

placard:

THE BLUE HERON

LUNCHEON, TEA AND DINNER

STELLA BURDETT: PROPRIETOR

"Doesn't open till about eleven-thirty," vouchsafed a Denver policeman who had halted to look at this strange person—a desert rat trying to get into a tea-room at quarter after seven in the morning!

"Thanks!" grinned Mojave. "I get up too early for this town—jest got in on the train from Arizona. They tell me guns is barred here, unless you get a permit. Now, I got a gun on me, but I shore need a permit. I'm carryin' a certified check—mebbe it's good, too—for a whole lot of money. D'you s'pose I could get a permit right quick?" He fished down in his pocket and brought forth the two ten-dollar gold-pieces, which with some smaller currency had been given him in change by the hotel clerk. Mojave passed them over to the officer, who took them deftly, and grinned.

"You look honest, feller," he said, suppressing part of a chuckle. "Tell the truth, we aint lookin' for guns—much. I'll fix you up. You aint gunnin' for nobody?"

"Not me," smiled Mojave. "I'm just aimin' to pertect something I'm carryin'—until yore blamed Miners' and Traders' National opens!"

"Well, I'll get you a three-day permit. Is that long enough?"

"Officer," said Mojave, "if I'm in this man's town three whole days, it 11 be because I'm a corpse, havin' shot myself from plumb disgust!"

He winked as he said it. And as the policeman was nearing fifty, he knew Mojave's kind. With a clear conscience a few minutes later, he went back to the station-house, slipped a new ten-dollar gold-piece to the sergeant, and then mailed the permit to the hotel address the prospector gave.

Mojave, his steps slowing, started for the bank where he would find out the first of his troubles—find out if he had been bilked. The lawyer had said no.

But it was not yet time, he remembered. He plunged into a white-front restaurant, and there consumed a large orange, then another, then three orders of buckwheat cakes with syrup. And coffee. For breakfast dessert he had a third whole orange, not peeled. He ate that orange in his hands, scraping it in sugar. He had not even guessed how starved he had been for fruit like this. Nine years on the arid Mojave!

"I AIM to open a checkin' account, an' a savin's account,

too." The prospector stood in the marble-walled, vaultlike room

of the big bank. He was up before the polished brass grille of

the receiving teller's window, inwardly a little awed at the

magnificence, but showing none of that awe in his rough-hewn

countenance.

"Certainly, sir. Step this way." The teller came out of his cage, and opened a door leading to a booth in which stood chairs and a glass-topped desk.

The prospector found himself writing on little cards. He inscribed his own name thrice, then looked up. "This checking account is for me," he said. "But the other aint. It's all right if I write another name?"

"Certainly. The other person will have to drop in some time and leave specimen signatures—or send them in a letter, if he isn't in town."

Mojave nodded. He had a little difficulty about writing that name; but did so finally, in spite of a hard ring which seemed to have formed in his throat for the purpose of choking him. Then he reached down, brought up his rawhided roll of bills, and slowly peeled off ten of the largest. "That's for the savings," he said.

Behind his glasses the teller's eyes twitched ever so little at sight of the bills—and then widened as he read the name of the person who was to get this money.

But he was not a talkative sort. When the prospector drew from a wallet a folded yellow slip of paper and endorsed it, placing it atop the cards bearing his own signature, the teller looked at it closely, examining the certification.

"If that's all right—they told me it was—" began Mojave after a moment. To him checks were a new departure; and what differentiated a certified check from one of the ordinary sort was a mystery still.

When he walked out of the bank fifteen minutes later, however, Mojave Corlaes had a thorough working knowledge of a checking account. The bank teller had exerted himself in behalf of a new, and what looked like a startlingly profitable account.

MORE than two hours to kill. The striped pole of a barber-shop

caught Mojave's eyes. He descended to the basement shop. There

keen steel, liquid soap, and perfumed lotions were applied

lavishly. Mojave grinned at the dude who grinned back at him from

the looking-glass when he got up; and then frowned when he

attempted to put on his battered felt hat—with this new

style of haircut it came down over his ears.

Half an hour till twelve. The hat bothered him. He saw a sign: "Bensen and Williams, Outfitters to Men." He went in rather hesitantly, intending to buy a new hat—cream color preferred. He succeeded in making that purchase; but when he emerged from the store at ten minutes of one o'clock, that broad-brimmed hat was the only article of apparel which hinted that he was not of the city, quite conversant with its newest modes.

But though he felt queer—rather light and floppy—in his new attire, a brisk walk of three blocks brought back some of his assurance. No one paid him any attention now; he observed that. He stopped and bought a cigar; it was ten cents now instead of five, he noted. Prices had gone up to beat the band during the past nine years!

EVEN now he did not head straight for the tea-room. The

show-window of a jewelry store drew his eye. He stopped in front

of it, gazing fascinatedly at the gems and silver spread upon the

purple velvet. "Gosh!" he breathed softly. "What would a woman

like, d'you s'pose?"

Finding no answer to his question, he obeyed a sudden impulse, and entered. The store was almost deserted at this hour; an urbane clerk appeared before him on the instant.

"What's the finest single piece of jewelry you got in the shop?" Mojave asked abruptly.

"What's the finest single piece of jewelry

you got in the shop?" Mojave asked abruptly.

"The finest—eh?" The clerk paused, tapping his finger ends slowly together. His eyes searched the features and dress of this strange customer. The glance noted little details—the coppery tan of skin, the awkwardly tied bow tie, the slight discrepancy in the fit of a Norfolk jacket across a pair of shoulders widened by years of pick, drill and single-jack. "Just what sort of jewel were you seeking? A diamond, perhaps?"

"Nemmind the kind just now. I'm jest askin' one question. What is the best yuh got—an' how much is it?"

"W-why, I—I suppose you mean the Whitehall pearls. They are perfectly matched—sixty-four of them—" A slight stutter had attacked the salesman. His right foot moved an inch nearer the burglar alarm below the counter.

"How much?"

"Why—Dr—thirty-five thousand dollars is the price."

"And will you take a certified check on that there bank across the street?" Mojave jerked a thumb toward the granite pillars of the Miners' and Traders' National.

"Why, certainly. Surely—"

"All right. I'll be back, pronto."

With that, Mojave turned on his heel and crossed the street between the taxi-cabs. Twelve minutes later he re-entered the store, found his man, and shoved across the counter a blue stamped and mystically initialed check for thirty-five thousand dollars. "Jest give a paper statin' I got that much account here," he requested.

"But—don't you want to see the pearls? To take them—or have them delivered somewhere? I thought—"

"Mister," said Mojave quietly, "thinkin' aint yore long suit today, I reckon. It aint any trouble to you if I don't take yore goods for two-three days, is it?" A flash from the deep, smoky eyes put an edge to the demand. "I jest want a receipt for a sorta deposit, so's I or somebody else with the paper kin come in an' buy—up to thirty-five thousand."

The matter was adjusted then. Mojave would have to send a written order, if some one beside himself came in to make the purchase. Otherwise it was all splendid, lovely, perfectly delightful; they were duly grateful for his patronage. The clerk had regained his savoir faire to a certain degree. Nevertheless he mopped tiny beads of perspiration from his forehead with a monogrammed silk handkerchief, when the plate-glass door swung closed behind the customer. There had been a large and suspicious bulge over the right hip of that desperate-looking visitor!

NEARING the Blue Heron, Mojave slowed. Somehow his knees felt

weak, and the palms of his calloused hands had grown clammy.

"Mebbe she don't want to see me—" he muttered thickly

below his breath. This man, whose lean one hundred and ninety pounds

of bone and muscle showed three bullet scars and a puckered knife

slash received in separate, deadly combats, found his eyes

focusing vaguely, his steps faltering, at the thought of

entering—a tea-room!

But there was a fierce ache deep within him, and that drove him on. He entered, ascended eight steps, gave his hat to a blonde-haired girl in a bright blue uniform—good Lord, pants, she wore!—and walked slowly into a rather dim room, lighted only by small rose lamps on what seemed a thousand tiny tables. Men and women. A subdued hum of conversation. Up there somewhere out of sight, the weird nasal whine of an oboe, accompanied by strings and muted brass.

A waitress took charge of him. She wore a blue dress, thank goodness! She led him to one side, where a deep seat ran all the way around the wall. Deftly she lifted away the small table, then replaced it as he sat down. A menu card was handed to him. A bus boy presented him with ice water, a basket of bread, two thin and icy pieces of butter, and an array of silver utensils sufficient for many complete courses.

Mojave's misery increased. For the moment he was tongue-tied, and he could not read the menu for a swimming of his vision. After a few moments, during which time he stole furtive glances the length and breadth of the restaurant—no, Stella wasn't there; of course she wouldn't be—the smiling waitress returned.

"And yours, sir?" she questioned, pencil on pad.

Mojave looked up, and was reassured. "Sister," he said, for he suddenly trusted the look of pert decency about her, "I'm jest off the desert, where I been nine years. I reckon I'll start in slow. Jest bring me somep'n light—an' a lot of coffee. I leave it to you."

She laughed, dimples appearing in her cheeks. "Ill treat you right, pardner!" she responded. "Are you real hungry?"

"Not for food. I can eat—but I came here for another reason. Is Stella—Miss Burdett—anywheres about? I—I'm aimin' to see her."

"I don't know; I'll see." She tripped away.

Five minutes later a somewhat older, rather stern-faced woman came from the offices in back, and was guided to Mojave's table. She looked at him with a piercing scrutiny. "Miss Burdett does not come here usually until five or six of an afternoon. Is there anything I can do for you?" she questioned. "I am the manager of the Blue Heron."

"Why—no—ma'am—that is, unless you kin tell me where I'll find Ste—Miss Burdett. I—"

"That really is hard to say," the woman responded with distant courtesy. "Miss Burdett owns four restaurants—the Pink Poodle, the Cock and Bull, the Spotted Fawn, and this one. She may be at any one—or at her city office in the Wallack Building. She—"

Of a sudden Greta Myers, the manager, broke off. She suddenly had connected up—or thought she had—a vague familiarity in the features of this stranger, with something else. She looked again, more intently. She leaned forward over the table.

"Tell me, do you know Miss Burdett well?" she demanded.

"I—used to," fumbled Mojave. He did not like those black eyes which bored into him. What was the matter with the woman, anyway?

"Then wait here a minute." Miss Myers strode away, threading the maze of tables, patrons and servitors with an ease and grace not seemingly compatible with her curveless figure.

BACK in the office—the office Stella Burdett had used

as headquarters when she first launched into large-scale

restaurant operation—the angular, stern-looking Miss Myers

stared up at a framed picture just above the glass-topped desk.

The picture did not belong to Miss Myers; a duplicate of this

photograph—a glossy print copyrighted by a large photo

agency—hung above the office-desk five places in the city

of Denver. The photo showed a desert prospector cinching a pack

on a patient burro—or so the caption on the picture

alleged. Actually that burro, once the property of Mojave

Corlaes, had been well termed "sweated dynamite done up in

orneriness."

Miss Myers stared. She shook her head, and her thin lips dragged downward. It was the same man, no doubt of it! With a grimace of acknowledged neglect, she looked at the withered tip of Spanish dagger blossoms which slanted behind. She was supposed to renew this every day or two, but it just had slipped her mind. Miss Myers was unromantic—on the surface at least.

One finger touched a buzzer. "Send out for a tip of Spanish dagger right away. Go to Halleck's. If they haven't got it, bring six of their best American beauties. Hurry!" she directed. Then she lifted the receiver of her telephone, calling her employer.

Four minutes later, as Mojave was chewing disconsolately at the fragment of a bread-stick, the forbidding-looking Miss Myers came down the aisle and stopped. She leaned over. "Miss Burdett will be here to see you in fifteen minutes—or less!" she snapped, looking quite as though she would bite off the head of poor Mojave for far less than the price of a bread-stick.

Then she left. She had been fully determined to tell him about the photograph in the office. But at the last minute habit had been too strong. Miss Myers stalked away, a flush coming up to burn the sallow of her cheeks. Damn men! Damn herself! Stella Burdett had known what she was doing, after all. What a man he looked to be!

Food was nothing. It had stuck in his throat for fifteen minutes, twenty. The tall man could not sit still. He carved deep and savage dents in the tablecloth with a dull silver knife. He choked over canapés Lucullus, which tasted faintly of fish—though he liked fish, ordinarily.

There had been a drink served. It was yellow-greenish, in a small glass. And it had some funny-looking thing sunk to the bottom. Mojave knew it was liquor, by the smell; but he was sizing up a dry Martini cocktail for the first time in his life. And this, too, was the first olive in his narrow gustatory career.

Now he reached out, nearly crushing the fragile glass, raised it to his lips, and gulped. Tingly and queer—not bad. The small green prune—ugh! He pretended to cough—leaned over, spat it out.

"Damn such stuff!" he muttered, wiping his mouth with the tiny napkin. He looked up—and there was Stella. She was holding out a hand to him, silently.

NINE years! It does much to the soul of a man who is alone in

the desert—and likewise to a woman who waits for him.

Mojave was a fool in some city ways, and some woman's ways.

Slowly, an inch at a time, his own two hands came up. But he no

more than clasped her hand the briefest of instants.

He saw now that she was not the girl with a pick, old Burdett's daughter, whom he then had loved—that half-wild, snappy-tongued young girl in rags whom he had loved.

Here was a more slender, more perfectly formed woman, impeccably groomed. Where had been a scrawny neck, a flat chest like that of a boy—oh, God! She wore a droopy hat that became her; a light gray, filmy summer dress, V-necked. Mojave, with the last of his supposed courage oozing out through his heels into the floor like a vagrant electric current, knew that across the table from him now stood one of the most beautiful women in the world. Her features had become more fine. Her eyes were dreamy—had lost their antagonism, somehow. She had rounded out—and at the same time had seemed to grow more tall and slender.

Stella said not a word. Her hand, and the message in her eyes, she thought enough. As most women do, she undervalued the love of the man, and overvalued his knowledge of women. Tears had sprung to the eyes of Mojave—and he was as hard-boiled a specimen as the desert had produced for many a year.

"I reckon—I'm sayin' hello—an'—good-by," he stated painfully. With clearness he saw now how utterly idiotic his notion had been—thinking Stella would still be the bright, alive, but well-nigh uncultured girl she had been nine years before.

"Oh, no, you're not, my friend," denied Stella, a smiling mask coming up quickly before her eyes. "After nine years—well, I demand at least three or four days! Isn't that my due, even if you don't care about me much any more?"

"Oh, Lord, yes! Stella—"

"Please don't tell me you have forgotten it! I—well, Mr. Prospector, have you got the stake you promised—the ten thousand dollars? You always were a stubborn cuss."

Stella spoke lightly, yet she waited. If the man had come back to her like a coyote with his tail between his legs, she believed she would send him packing—even though she had waited for him nine long years. Not that she needed capital. Her restaurants could be sold any day for big money. But the man had left her when she first loved him, swearing that he would wring ten thousand out of old Mojave. He had been stubborn as a mule. She had derided his belief. Now he was back—after saying he never would look at her again until he had made this stake. Stubborn. She had written him ten or a dozen letters, telling him she had more than the stake he named—once or twice actually pleading with him to come back.

Silence. Some of the letters had come back, after weary months.

Mojave never had received a single one of those missives. He had possessed no headquarters, no postal address, until quite recently.

"I—made it," he answered, fingers searching for the brown-covered bankbook, then coming away in haste. He could see for himself that this was no present for a woman like Stella had become.

"Oh, I'm so glad!" There was no doubt of her sincerity and delight. She came and sat beside him on the bench. "You really did find another Yellow Aster? Tell me about it!"

"No, not gold. Tungsten. A lot of it. You know, since the war—it's gone up. Twelve dollars a pound, now, and still going up—"

Mojave's lips moved. Haltingly, dryly he told a fractional part of that magic romance of the desert. Out there in the arid wastes he had come upon a mountain of heavy ore—ore which assayed tungstic acid sixty per cent to the unit. They were piping water out forty miles—because tungsten somehow tempered steel, and steel now was needed in vast quantities.

Stella knew nothing of tungsten. Twelve dollars a pound did not sound to her like treasure, daughter of a gold prospector as she was. Inwardly she supposed that Mojave's search had netted him little more than that determined stake—a sum so pitifully small now in these days of rapidly advancing prices.

BUT she smiled, cajoled him, played the part of brilliant

hostess—little suspecting that through each succeeding

minute the man's heart sank lower in his boots. In turn she told

how a few thousand dollars, inherited from an uncle of hers, had

established her in business. She did not say how enormous that

business had become almost overnight; how the name of Stella

Burdett, with her new and enormously popular style of restaurant,

had come to be a front-page newspaper commonplace in this city of

quick action.

For Mojave, however, the money meant nothing. He was glad for her—and sorry for himself that he had not found her on the verge of starvation! It was the woman herself. At thirty, and almost without a vestige of formal education, she had made herself, outwardly at least, a thorough aristocrat. If there were signs pointing otherwise, Mojave could not see them.

The man ate no more. He finally drew out the little bankbook, keeping a broad thumb over the name on the page, and exhibited the entry—$10,000. "Jest so's yuh wouldn't think I was lyin', Stella," he said huskily. He was conscious that his hand—his peerless gun-hand!—was trembling like that of an old man afflicted with the palsy.

"You don't imagine I wouldn't take your word, Bill?" she asked softly. He had never been Mojave to her. "But your luncheon—don't let me—"

"I couldn't eat bacon an' beans! Not even them any more!" he said positively.

"That's your superlative, still?" she laughed, noting from the corner of her eye the untouched breast of "Stubbleduck" (Chinese pheasant) au Châtelaine, on his plate.

"Stella, I—well—you see—hell, I want to do something. I made more'n that stake I showed you. I want to—I want to give yuh a present—jest somep'n to remember me by. You know—"

He was floundering desperately now, and his eyes avoided hers. Inwardly sensitive for all his poker face and steel-corded muscles, he was in abject misery; only a determination as hard as his own mountain of tungsten drove him on. Stella was as high above him as the bright blue star of evening; yet—

Somehow he made her understand. Her hazel eyes had clouded a little with a look of pain, delight, amazement. She was used to reading men. His trouble was not that he had ceased to love her, but that he loved her too greatly! Too greatly that is, for even a modicum of common sense; it is doubtful that any woman ever has thought herself loved too much.

And suddenly her vivacity, every shred of her pose of hostess—nearly real with her now—departed. She was not even smiling. Oddly quiet, she went along the aisle, seeing none of the men, hearing none of the greetings from her customers—

WITH Mojave she descended to the street. He seemed to have a

definite goal farther up the street. He had. It was the jewelry

store with the purple velvet draped show-windows. They entered.

And with almost suspicious celerity, a clerk separated himself

from an undecided customer back at the wrist-watch counter, and

made for them. It was the same clerk.

He came—and made a sign with his right hand. The store, detective sauntered out, and down toward the entrance.

Mojave noticed none of this. He nodded abruptly to the salesman, tossing him a small, wadded paper, the receipt. "Stella," he said. "I'd 'a' got yuh somep'n, only I know yuh'd rather pick it out. Anything this shop's got. Mister, among other things, show her those pearls." The last was addressed to the man behind the counter, on whose countenance had appeared the slightest trace of a knowing smile.

Stella looked at him. "Do you mean," she asked in a queer tone, "that you want to give me whatever—I—I want in this whole store?"

Stella looked at him. "Do you mean," she asked in a queer

tone,

"that you want to give me whatever—I—I want

in this whole store?"

"Yeah. It's already paid for. All yuh got to do is pick it out." Mojave was staring out at the cold, gray majesty of the bank pillars across the street. He could not bear to look at her any more.

The woman's eyes flicked at the salesperson inquiringly. "I shall bring the Whitehall pearls immediately," he said.

"Don't bother," said Stella. She drew Mojave a little away. "Bill," she said with a queer rush of breath, "instead of one big present, would—would you let me pick three smaller, but not so expensive ones?"

"A hundred, if yuh want 'em," said Mojave. "Honey—" Only that last word was not articulated. Somehow his throat was strangulated.

Stella had turned back. She went swiftly along the counter, tap-tapping a little finger signet on the glass. Before the superb display of ring sets she stopped. "Size seven and a quarter. That one!" she whispered, pointing to a one-carat square-cut diamond solitaire deep set in platinum, resting beside a chased platinum band ring.

She looked back; Mojave had not moved. Head erect and shoulders squared, he was faced away—a million miles away. Though Stella could not guess, the man was gazing through the blue-black veil of desert darkness toward a sinking evening star—the blue planet Venus. Not to touch a star—

So Stella fitted the ring, and found the size perfect. She took the box with it and its fellow. She went to Mojave. "We're all fixed," she said, touching his arm. "I have two of my three presents—and you have some change coming, big man!"

"Leave it there, till you want somep'n else. It's yores," answered Mojave quietly. "I've owed you more'n you ever will know, Stella. Life from now on ain't wuth a damn; but it has been—out under the desert stars! I've—" But there speech deserted him.

"Come on out," bade Stella Burdett. She distinctly did not like this; and she would put an end to it if she could. God, what dumb creatures men were!

"You didn't even ask me what I selected for my two-out-of-three presents," she reminded him, when they were on the sidewalk.

"It don't matter, Stella," he said. "I hope you'll be wearin' 'em, to remember me by. I—I jest aint good enough for you, girl. I know it."

"Bill," she said softly, a smile—and years of longing—in her eyes, "if I ever wear these to 'remember you by,' I surely wont have a chance to forget—will I?" And she snapped open the box, holding up to his gaze a diamond engagement solitaire—and a thin chased band of platinum.

Mojave's lips moved, though no sound came from them at first. "They's a God in heaven. They's a God—" were the words he framed soundlessly.

"You haven't asked me what was the third present I wanted," she said, pretending to pout, though the rejoicing in her eyes would not be quelled.

"Oh, Lord, my sweet, tell me quick! I—"

She smiled at him. And in her eyes was the delight and understanding that for her had been kept the best of all men. "It's something I've had—but never given, Bill. A kiss! With you here, all the rest of this—" she gestured at the busy street and the people who looked at them inquisitively—"is the last mountain range in the Mojave!" She came a step closer and lifted her arms, to place them about his neck.

With a cry that was no word, Mojave flung his arms about her and pressed his lips on hers.

THAT afternoon late, Elbert Pettingill, of the branch jewelry

store of Dayson, Moore, Incorporated, brought a paper to the

store manager. "That was our crazy man!" he said.

In a preferred position was a tale of how one William (Mojave) Corlaes, the desert rat, had sold his group of claims on a tungsten mountain, to a British-American syndicate, for the sum of six hundred and forty thousand dollars.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.