RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

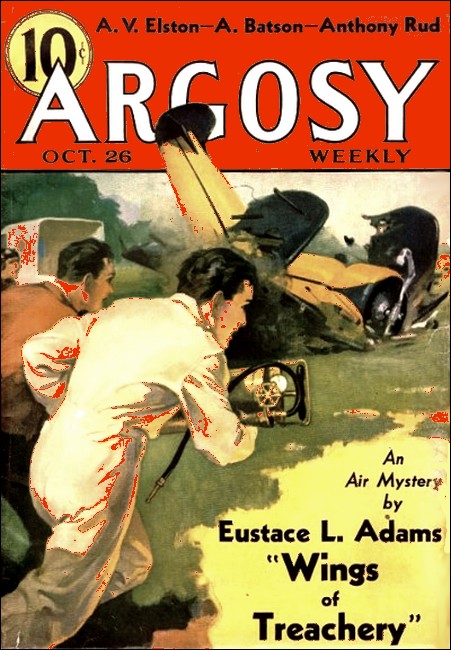

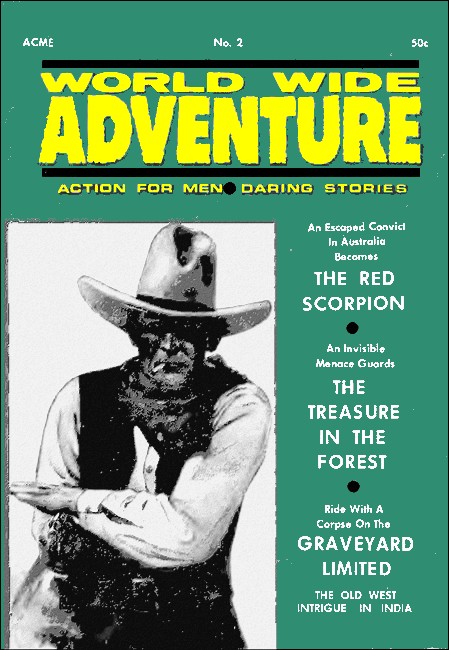

Argosy, 26 October 1935, with "The Red Scorpion"

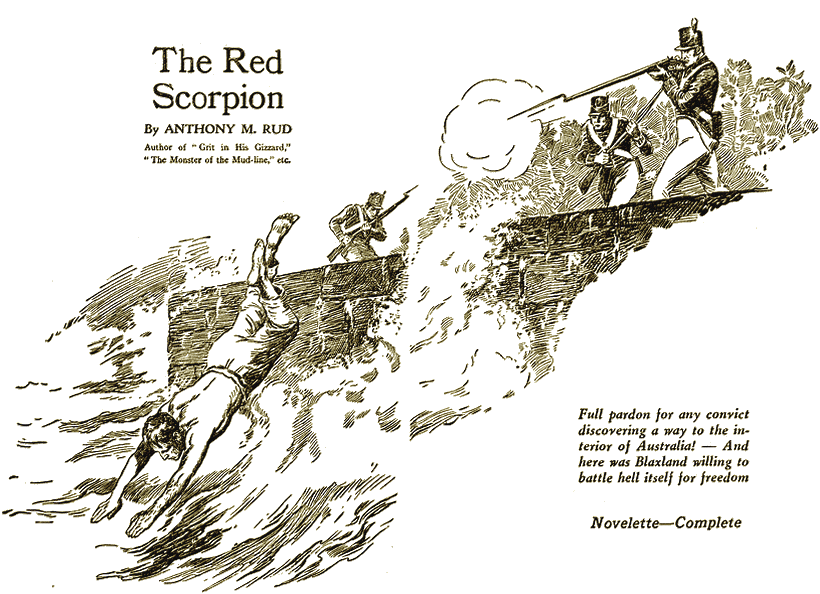

Blaxland hoped to swim out of sight.

Full pardon for any convict discovering a way to the interior of Australia!—

And here was Blaxland willing to battle hell itself for freedom.

"JOHN MacARTHUR has lost eighty-one fine wool sheep from starvation this blasted month. There is not enough flesh on all the sheep still living to give all of our thirty thousand souls one mouthful apiece. In other supplies, there cannot be more than two weeks' supply even if we let the convicts starve!"

General Lachlan Macquarie, Governor of New South Wales, following the unfortunate Captain William Bligh of the Bounty, closed his browned right fist. He rarely raised his voice, though he was a man of strength. The work of undoing Bligh's mismanagement, and building a colony back of Fort Jackson and Botany Bay, had taken three harsh years. Now drought, and the failure of the food ships from England, made it seem that famine and horror were to be his only reward.

Lord Bathurst of England shifted uncomfortably and frowned. He had been a visitor at Sydney four months longer now than he had expected to stay. The great sheep station he had intended to establish with John MacArthur was impossible—unless some way could be found through the impassable barrier of the Blue Mountains to the interior. So far, all attempts to cross the mountains had failed.

"There are two ships from England overdue," he said, shaking his white-powdered periwig. "One of them—"

"Three are overdue, my lord," said Macquarie grimly. "The Balmoral Castle, with six hundred convicts in her hold, has been expected this fortnight. If she arrives first—"

His mouth set in a harsh line, but the blue eyes were misery-filled. The utter impossibility of making this strip of infertile land, fifty miles at greatest width, sustain a convict colony of twenty-eight thousand exiles, had been proved to him. And each year, England sent out food ships laden with the absolute minimum in rations for all.

Then one of four such ships failed to reach Australia...

Lord Raley, Charles Butterworth and two others of the council spoke indignantly concerning England's responsibilities.

But all such talk was futile. Lord Bathurst rose to his feet.

"Gentlemen," he said impressively, "I believe in the great sea which lies in the interior of this continent. It must be similar to our Mediterranean. The fact that the Nepean River and those other small rivers cutting through bottomless gorges in the mountains seem to flow uphill strikes me as bosh."

"Ah, but that is proved!" sputtered Butterworth, his pince-nez falling from his broad, fat nose. "The great engineer, Fitzgerald—"

"Was mistaken. That is all!" Bathurst finished bitingly. "Water seeks its own level always." He glared at them all, from the full height of his five feet four inches.

"But they all flow away from the ocean!" Butterworth contended feebly.

Bathurst, full of a new idea, did not answer this, which of course was demonstrable truth.

"I believe, gentlemen," he said, "that a way over or through the mountains can be found! Yes, in spite of those fifteen-hundred-foot gorges and blank walls or rock, and in spite of the rapids and falls of the rivers!"

"So many have tried," sighed Loren Raley, a white-haired, pink-faced old man who had hoped to be Bligh's successor as governor—and who had vegetated in Sydney when his hopes exploded in his face.

"Let more try!" snapped the diminutive lord. "I am giving up my plans and going back to England—when I can. But I shall endeavor to leave my name as a true friend of Australia, not just as one who came, saw, and was conquered. I shall—"

Here ensued a strange interruption. From the smoke-cured rafters overhead, something heavy, segmented and armored fell to the eucalyptus boards of the governor's table with a rattling crash.

ALL the men arose swiftly, backing away. It was a huge red scorpion with a forward-curved tail, and claws as big as those of a crayfish, opening and closing in anger. It was the only deadly creature thus far known in the whole of Australia, save only the crocodiles of the yet unknown Cape York.

Raley fumbled out the big pistol he wore; but Macquarie motioned him to put it away. Taking up a long-bladed paper-knife, the governor leaned forward. The thin blade whizzed side-wise through the air. There was a click—and the scorpion was still there, waving its tail as though nothing had happened. But the end segment, containing the deadly sting, had been separated from its body!

Saying nothing, Macquarie picked up the now harmless creature, as one might pinch the back of a crayfish, and tossed it out of the low window to the grass in the yard.

"Its claws will suffice, so it will not starve," he said laconically. "Better off than we. Ah, yes, my lord, you were saying?"

Bathurst shook his powdered head. "I am glad this is not a superstitious age," he said dryly. "Our forefathers would have thought that an omen of disaster and death. We moderns have learned that omens and witchcraft, all of the black arts, exist only when someone believes in them."

This was entirely too modern for some of the council, who exchanged alarmed and doubtful looks; but no one spoke.

"So the crux of my proposal is simply this: I shall leave with the governor a sum of five thousand English pounds. This is to be given unconditionally to the man or men who succeed in discovering a way across or through the Blue Mountains, to the interior of Australia!"

The sharp intake of breath from all of the council could be felt in the ensuing seconds of silence. Money being worth what it was at the time, 1813, this was generosity comparable to the offer of a hundred-thousand pound prize today. Many of the councilmen began to frown and ponder ways by which they themselves might win this great wealth.

But Lachlan Macquarie was on his feet, something like a vision reflected in his blue eyes. He thanked Bathurst for all of Australia, and then added briefly an inspiration which had just come to him.

"I shall add to my lord Bathurst's munificent offer," he said, "any five square miles of Australia lying beyond the mountains, to belong to the prize-winner and his heirs forever. Also," and here and there councilmen noted his dour look, "I shall ask each month, from now on, for a volunteer explorer from among our convicts! Each will be outfitted and loosed in the foothills of the mountains. If any wins through, and returns to show the way, he will receive full pardon as an English subject, in addition to the two grand prizes mentioned!"

There were open murmurs of protest at this; for already Lachlan Macquarie had made a name for mercy toward convict exiles, and the ordinary settlers did not approve. The governor, receiving a man from a prison ship, sentenced to two years in chains and banishment forever, struck off one year of the sentence when the prison ship took six months or more to reach Australia.

He argued hard-headedly that six months in the hold of a prison ship meant enough punishment for any crime, even murder or treason. And so the factions which had benefited from the high-handed measures of Bligh and his autocratic predecessors constantly were complaining to the king of Macquarie's methods.

"Gentlemen," broke in the governor sharply, "do you realize we are starving? Do you know that there are scores of intrepid men sent here for political reasons who would charge the jaws of hell itself for a chance at liberty? Let us say no more. I shall hope one of you, or another of our settlers, may win. But win we shall and must! The mountains strangle—"

The door swung slowly open, and there stood a retired petty officer of the British Navy, a brass spyglass under his arm. His bronzed face had grayed in curious fashion.

"Yes, Littleton?" asked Macquarie with impatience.

"A ship!" croaked the oldster. "A ship!"

Excitement brought them all to their feet instantly. A ship meant food for all, or—

"And by her black tops'ls, sir-r, it would be the Balmoral Castle, bearing us six hundred more of them convicts, sir-r!"

OF the six hundred and eighty-three convicts sent from Yarmouth on the Balmoral Castle, four hundred and eighty-nine arrived at Botany Bay. Nearly two hundred died and were tossed overboard during the prison ship's stormy seven months of passage.

The living remainder were scarecrows, caricatures, maniacs, sullen imbeciles—almost anything but the rebellious, crafty, or anti-social creatures they had been in England. Unshaved, unshorn, most of them wearing the filthy rags which had been their only clothes for more than half a year, all of them with sores from their shackles, many with horrible chronic diseases that the worst of them had brought along, this belching forth of human prisoners was a sorrier spectacle than if they had come at Gabriel's trumpet from the relatively clean privacy of their own graves.

Many, of course, had deserved punishment. Almost as many, though, were victims of the political and social upheaval in England, due to Napoleon's victories on the Continent, and England's truculent hesitations. In those uneasy days it was high treason to fight over even a strictly private matter.

The slow, staggering crawl of these half-dead men, still chained together as they came to the shore to which they had looked forward as a blessed end of the worst of their trials, was the more pitiable now—for the shore guards who took them in charge took no pains to conceal the fact that all the newcomers were bitterly unwelcome.

Buffets and curses were given for nothing, until Lachlan Macquarie observed one such incident. Mouth set in sternness, he stepped forward, halting the line. He gave brief orders, and the offending guard, to his horrified astonishment, found himself in the shackles and place of the man he had struck!

This lasted only until they reached the prison, half a mile distant. But there were no more uncalled-for brutalities in public.

The dandified but genuine Bathurst had come out with Macquarie to view the new prisoners. The nobleman was stricken dumb by the awful plight of these wretches, a few of whom he recognized because of the sensations their arrests had caused before he left England.

There was Wharton, the branch bank manager from Sussex—the fellow who had calmly admitted his defalcations, claiming that he had spent the money as he went along, and that nothing was left. Of course he had not been believed, since the missing funds reached the staggering sum of a quarter million pounds. The bank had offered him terms on his charges, it he would disgorge. Bathurst wondered if he had done so in the end.

There was the saturnine Dr. Lethridge, known to be a murderer. He had been held, his trial postponed, because the police were still searching for the corpus delicti of a young woman. Evidently they had not found it, after all, or the medico would have gone to the gallows at Dartmoor.

There was the English Nihilist, Simcoe, who had wangled his way into the House of Commons, only to—

That second the thoughts of Lord Bathurst whirled. He almost staggered back, lifting one lace-cuffed arm as if to ward off a blow. His slightly protuberant eyes bulged farther. He gasped, and for a second no words at all would come. Then—

"Blaxland! You!" he screamed in horror and dismay.

The whole line halted, even the guards staring, forgetting their tasks. There in front of the English peer a tall, tattered and filthy specimen slowly straightened from a stoop of apathy. It was shocking to see that this was a youth no more than twenty-two or twenty-three years of age at most, though his sunken, bloodshot eyes came from their glaze of numbness to a wild gleam like that of a caged tiger.

His eyes were almost all of his face that could be seen. His hair was flaming copper in spite of the dirt. It was long enough to reach his shoulders. His face to the cheek bones bristled with a rather coarse six-inch beard of the same color. Out of this tangle came the one feature Bathurst instantly had recognized—the hawklike, imperious Blaxland nose.

Though not of royalty, and not of great wealth any longer, the Blaxlands traced their ancestry back to Pepin the Short—and were prouder, perhaps, than Bathurst himself.

GEORGE CECIL BLAXLAND said nothing. His blue eyes flamed; for he knew well that Bathurst had come to the Antipodes chiefly to avoid seeing a Blaxland marry the winsome miss they both had courted. Now the peer would have a clear field, no doubt.

Incoherent, driven by emotions no doubt as mixed as the snuff he blended according to the secret formula bequeathed by Charles Fox, Bathurst ran forward and seized the arm of the unfortunate youth, demanding the reason for the chains and the banishment. At the time Bathurst himself had left England this young lieutenant of the London Guards seemed to have a happy future assured. The sweetest belle of the London season had plighted her troth to him.

The guards, awakened to their duties, would have interfered; but Lachlan Macquarie himself signaled quiet. In view of what Bathurst was doing for Australia in her need, they could not grudge him a few moments' breach of iron discipline.

The convict shook off Bathurst's arm. Inside that copper-red head pride and bitterness surged up in an engulfing hate of man and circumstance.

"Unclean! Unclean!" he gritted savagely, mocking the cry of a leper at Jerusalem's gate. "A private insult. A duello on the Mall at dawn. And I am condemned to three more years of chains and a lifetime of exile!"

"Wh-what—who was it?" stammered Bathurst, appalled.

"My superior officer, Captain Vivian Laidlaw."

Now Bathurst really understood. Laidlaw had been the hero—or villain—of many a court scandal. He had killed three men in pistol duels; and each time London sighed and marveled that one who needed killing so badly should have such skill with weapons. Now he had met one more skilled or more lucky; and probably one highborn lady wept her heart out for the scoundrel, and demanded vengeance on the survivor.

"I—I surely can do something about it—for you—" stuttered the peer. "You do not deserve this. I—"

Blaxland leaned toward him. The grim slash of a mouth scarcely parted, as he spoke so the others could not hear.

"I ask nothing for myself!" he said. "Be good to Elspeth and teach her to forget. Good-by!"

As if he had commanded the file of convicts, all started the weary forward shuffle then, and Bathurst was left to his snuff and his generous impulses—and his thoughts of Elspeth Stuart.

Macquarie came then, questioning. Bathurst told him of Blaxland, imploring kindly treatment for the young man until such time as he, Bathurst, could set in motion an application for full pardon.

As for himself, an immense impatience had seized the English lord. He would not wait for a cleaner ship. He would return to England immediately upon the Balmoral Castle.

THAT meeting with Bathurst, who had been a friend of his father and then his own rival, was a rebirth for Blaxland. The nightmare of the prison transport was finished. The stiff jolt of finding right here in Australia, able to gloat on his misery, the forty-year-old London fop whom he had vanquished for the favors of Elspeth Stuart, straightened him up from apathy and the numbness of despair. It was like an unexpected and agonizing plunge into ice water.

The effect upon red-headed George Blaxland was savage indeed. He had been resolved upon ending his misery at the first chance; and had nothing but curses for the fate that let the men chained on both sides of him in the Balmoral Castle's hold both succumb to the spotted fever which passed him as immune.

Now he tensed his tall, magnificent body, and swore grating, inward oaths that he would fool them all. He would serve his time until a chance came for escape. Then he would take it, no matter what the risk. To spend three years in chains was out of the question.

Almost the first word he heard in the prison was the announcement of the Bathurst and Macquarie prizes for the discovery of a way through the Blue Mountains. Once each month a convict who was willing to chance hardship or death was to be offered an opportunity to explore. If he failed he would have to return to complete his sentence; but great prizes were to be the rewards of success.

Under Macquarie, the bare barracks of prison buildings had been cleansed regularly. That much of mediaeval horror had been lilted; but the cells, each housing two convicts were large enough just to admit two stacked bunks of boards and straw, and leave a space eight feet by three at the side for all the rest of life for two men.

Even at night each convict wore a leg shackle, to which was attached a fifteen pound round shot and a short length of chain. This was a hideous torture to the one who had to accept the top bunk, since the bunks themselves were narrow and barely six feet long. A sleeping convict in the top bunk could not afford a nightmare, or he was likely to find himself yanked out to the floor suddenly by the fall of the heavy round shot!

Blaxland had only a few minutes in which to make the acquaintance of his cellmate, a pig-eyed, pale creature named Moebus, serving the last of a deportation year in chains for repeated offenses of a statutory nature.

One glance at the bestial face had made Blaxland shudder and turn away in dismay. To be shut in with this witless animal! It curdled the blood in his throat.

Immediately, however, he was taken out of the cell. His mane of hair was chewed short by the dull scissors of a prison barber. Then his beard was cut, and clippers brought him to a strange pallor both of cheeks and scalp.

Next he was sent, with four more new prisoners, to the pool. This was a sea water tank where once a month the convicts bathed. Here he dove and swam, lathered himself from head to toe with the green soft soap provided in a round tub.

On the ocean side, the breakers, driven by the January trade winds out of Samoa, were splashing spray thirty feet above the sea wall. White horses rode the crests of rollers as far out on the ocean as eye could reach.

Blaxland saw. The horror of a return to the narrow cell, with that insensate, bestial creature as an only companion, was unendurable. Now with the cleansing and the cold plunge, something akin to the old vitality was coursing his veins. His head came up in a defiance to fate.

"Better to die clean, and trying!" he said to himself.

He walked about, as if selecting a place in the pool for his final dive. A guard with flintlock musket and fixed bayonet accompanied him closely, only too willing to kill one or more of these prisoners who had come to take the bread from his own mouth.

SUDDENLY Blaxland whirled. There was almost a smile on his wide mouth as he caught one arm of the guard before the latter could bring down his weapon from shoulder.

A jerk with all his strength—and yelling his anger and alarm, the uniformed soldier took an involuntary header into the bathing pool, musket and all!

Over on the other side a second guard swung his musket and fired pointblank. Too hasty. The ball whistled past Blaxland's ear. He poised, waved a hand, and dove squarely into the slate colored side of a roller about to break against the sea wall!

The attempt was not wholly unreasoned. Visibility was poor; Blaxland hoped to swim out far enough so that he would be lost to sight of those on shore. Then he would attempt to parallel the shore, certain that the prison guards would hesitate long before launching a small boat in this sea. If he could stick to it long and far enough, he would slip ashore and hide somewhere until night. Then he would try to steal clothes and some sort of outfit.

What he would do then, in this parched land where even the masters of the penal colony were themselves near to starvation, had not seemed important—as it was not. Blaxland knew he was doomed to fail, ten seconds after his white body clove the water. He was tossed, smothered, well-nigh thrown back to be battered into a bloody mass against the sea wall.

A strong swimmer since early boyhood, Blaxland fought with all his strength in the smother of waters, and succeeded only in keeping away from the sea wall until it ended, and the shoreline of Port Jackson stretched to receive him.

A dozen guards now were there waiting. Occasionally one shot, though there was manifestly no need. Grimly Blaxland swam until the last of his strength, depleted by the months on the prison transport, suddenly left his arms and legs. Exhausted, turning blue in the face, he was lifted high by the next breaker and flung into the shallows, there to be turned over and over like a log of dead wood, until the guards waded out and caught him by the arms.

He knew nothing more until the first stinging bite of the knout across his back brought him to pain and a sort of consciousness. Spread-eagled, arms and legs shackled, he was hanging upright on the gallows-like whipping post.

Thirty strokes, administered with gloating satisfaction by the ape-like Matt Henry, executioner of the prison. His arms, toughened by years of the sledge and anvil previous to convict days, made his knout-wielding a matter of blood and stripes.

Blaxland came awake with a scream in his throat, but he throttled it into a choking gasp; and thereafter—even when he fainted and came back after the last stroke, to find buckets of sea water being sloshed over his prone figure on the ground—his slash of mouth tightened and he made no further sound.

The sea water bit into the welts on his back. When they urged him upright he was naked, and so weak two guards had to drag him to the solitary cell which would be his portion for a month.

There was one net gain from it all. He saw no more of the degenerate, Moebus.

LACHLAN MACQUARIE, who might have stopped or ameliorated this punishment, knew nothing at all of the occurrence. The prison warden had full charge of such minor details; and he knew nothing of Blaxland save the bare statement that he had been convicted of treason, cashiered from His Majesty's army, sentenced to three years in chains and banishment from the British Isles for life.

Ironically enough, though his fare was scant and he saw no human being save two surly guards, Blaxland much preferred his solitary confinement to the companionship of Moebus. Heavily chained, he spent nearly double the usual time in sleep, making up much of the exhaustion of the past months. During waking hours he forced himself to exercise systematically, gradually bringing tone to his long, supple muscles, in spite of the bad air and food.

"Sometime there will come a better chance," he told himself grimly. "I'll be ready!"

He tried hard to apply for the chance to make the explorer's attempt through the constricting barrier of the Blue Mountains, but the guards would not even transmit the message. This month a convict named Fessenden was chosen. He was given a light pack of equipment, knife, hatchet, flint and steel, and provisions for ten days. He was escorted out to the foothills near where now is Parramatta, and earnestly bidden Godspeed by Lachlan Macquarie himself.

The eighth day following, one of John MacArthur's sheepherders found him crawling on hands and knees. One leg was broken from a fall, and he was dying of thirst, having been unable to reach water after his accident in a rocky gorge.

Restoratives failed; and he died the next morning. This had a sobering effect upon the candidates for the prizes. A number of the more timid settlers who had been getting ready to try drew in their horns. Only a Lieutenant Wentworth, with a comrade, started out—taking with them a palpably absurd amount of impedimenta, which they were forced to cache before they had penetrated the mountains a distance of one-half mile.

A food ship did come then from England, which relieved the terrible stringency; but the rations in her hold were weevily and almost inedible. They had been what chandlers called "guff" in the first place; and the stormy, overlong sea passage made them truly foul. Just the same, the big colony at Botany Bay received them with prayers of thanksgiving.

Bathurst had sailed with the prison transport. He had struggled with his feelings and his conscience in respect to Blaxland. In the end he had sworn to himself to do something for the youth on reaching England; but he had sensed that Blaxland himself would misconstrue any prison visit, thinking it false pity. So he did not even leave a message.

Lachlan Macquarie, as soon as the lists of convicts with their sentences were put before him, commuted all the terms by a deduction of five months. He paused, frowning, with his quill pen hovering above Blaxland's name. But he put off action there, meaning to have a talk with the convict. The press of the food ship's arrival put the matter out of mind for the time being.

Deaths among the convicts who had just arrived numbered at least two each day during this month. One scarlet week at the last of the month eighteen succumbed to the various weaknesses and diseases contracted during the voyage.

The soil was clay and gravel, iron hard. The feet of the splendid Merino sheep raised by MacArthur and others had trodden the surface into dust; but below that the drought had an even harsher grasp. Burying the bodies of dead convicts had become a nightmare task.

CHISHOLM, warden of the prison, tried sinking them in the bay; but two days later the crab-mutilated carcasses were disgorged upon the beach and had to be buried anyway.

So convicts were told off as burying squads. It was punishment duty that all abhorred; so that was why George Cecil Blaxland was chosen. Chisholm had not yet been informed that any favors were to be given this red scorpion of a man, desperate and dangerous. So with a hoarse-voiced bull of a man with a black-beard, a veritable Hercules who had fought his way bareheaded out of an English prison only to be recaptured three days later, Blaxland was set to digging a long trench which would hold the bodies of four convicts.

Three guards with muskets and fixed bayonets kept careful watch over their toil. Both these men were known to be willing to accept the most desperate odds; and it was strange that all three guards, getting one startled look into the cold blue fire of Blaxland's eyes, counted him the worse of the two.

The black-bearded fellow, whose name was Moss, grumbled in his barrel chest with every grating spadeful he turned, occasionally bursting forth in an inarticulate, coughing roar like that of a caged lion being tormented.

Blaxland swung a pick methodically, glad of this form of exercise. He had sized up the situation, and decided that nothing offered a promise of escape; so he worked well and quietly. Good conduct might cause vigilance to be somewhat relaxed in the future.

But fate sets off its fireworks without regard to the auspiciousness of occasion.

Two of the guards, half alert, stood behind Moss. The third guard, who happened to be the same irascible fellow whom Blaxland had hurled into the bathing pool, stood directly behind the red-haired convict, his bared bayonet never more than twenty inches away from the gleaming muscles of Blaxland's bare shoulders.

This guard wanted only a shadow of an excuse. His teeth emitting faint grinding sounds, he waited. Just one false gesture with that pick, and Blaxland would have twelve inches of triangular steel rammed into his backbone...

Gorilla-like, Moss touched off the fuse. Like a grouchy old bear he had grumbled, roared, and subsided, only to break forth again. Everything about this job infuriated him, especially the cool, efficient fellow convict with whom he was paired.

Moss had no thought of escape. But as a half hour passed he began to find it impossible to restrain his churlish temper.

He suddenly erupted. One roaring cough, and he straightened from the trench, lifting a spadeful of clay and gravel and flinging it straight into the face of his astonished fellow convict!

Then as if crazed by this partial letting-off of steam, he scrambled forward out of the trench, swinging his spade high over his head, with the intent of braining Blaxland then and there.

The two guards behind him fired simultaneously; and the heavy musket balls tore through Moss's chest from behind. He pitched forward, red froth bubbling from his lips, and slowly slid back into the half-dug trench. He would be violent no more, but would be accorded the place of honor in this grave he had helped to dig.

That was the least important part. Surprised by the shower of clay and gravel, which an upflung arm barely kept from his eyes, Blaxland staggered back two steps.

That was almost the chance the irascible guard behind him had been looking for. Not a chance to kill the prisoner, perhaps, but a good chance for a measure of vengeance. With a satisfied snarl on his lips, he thrust forward the bayoneted musket, jabbing the keen steel four inches into Blaxland's thigh.

"Back to work, ye slother!" he snarled. "If there's fightin' to be done—"

The double report of musketry cut short his words, and that instant Blaxland, involuntarily leaping at the pain in his leg, half-whirled. The knowledge flashed through the red-head's brain that two of the three guards had fired their muskets, and would not be able to reload for at least forty seconds. Here was a chance for escape, with only one man barring the way!

All that inspiration had come in one-tenth of a second after the report, Blaxland's mind working like chain-lightning. With not even a hesitation, the action seeming continuous, he gripped the pick handle in his right hand and swung it sidewise with all his strength—against the grinning guard who had pricked him!

Even then the convict had kept his head. He turned the double-pointed pick sidewise, so that while the guard was smashed from balance, and would nurse a broken forearm as well as an augmented inner fury, it was not murder.

The guard screamed in a high-pitched voice, falling to the ground and dropping his musket.

Instantly Blaxland stooped, seized the musket—useful only for the bayonet which could be detached later—and with pick in his other hand he turned and sprinted with all his speed for the quarter-mile distant scrub which encroached from the foothills of the mountain barrier.

By the time the two other guards had shouted the alarm lustily, and had reloaded their firearms, the bell atop the main administration building was tolling the message of escape.

Lachlan Macquarie found out, just a few minutes later, that the convict he had intended to appoint to a light task of some description about the offices had disappeared after overcoming an armed guard.

"But we'll get him in a week," promised the aroused prison warden. "And this time I'll have Matt Henry cut him to pieces with the knout!"

The governor frowned at this threat, but he said nothing. After all, prison discipline had to be maintained; and probably this red scorpion, as the guards called him, was far more of a villain than the sensitive Lord Bathurst imagined.

THE eastern side of the Blue Mountains is vertical chaos, as far as travel is concerned. In physical appearance it is something like northwestern British Columbia in the Cascade and Coast Ranges. Soil is thin or non-existent, and rock is everywhere.

Canyons with sheer rocks for faces, and a multitude of seepage waterfalls lacing down the forbidding cliffs, run everywhere. The mountains themselves are only about 3,500 feet in height; but the canyons actually drop below sea level, and the contrasts are appalling.

A thin, discouraged mallee scrub exists part way up the mountains. Below that, in seasons of rain, there is grass and some other vegetation. Above that on the eastern side, nothing.

The bottoms of the gorges look from the heights as though strewn with roses. The truth is terrible. Tangles of prickly pear impenetrable to man or horse have grown there ten feet deep. What seem to be roses are the bright red fruit of this plague plant.

Tough goanna lizards six feet in length live there. The kookaburra or laughing jackass flutters, and yells his strident derision.

Apostle birds in their invariable groups of twelve sit around and debate momentous affairs between their meals of pear fruit.

They are harried, like so many savants tormented by urchins in their deliberations, by scores of cheeky little bower birds, who exist to annoy. Noisy minahs (soldier birds) squawk as they fly; and the tiny kangaroo mice come out to dance under the hot moon.

But none of these creatures is acceptably edible for man. True, goanna flesh has been eaten by starving men—just as the chuckwalla of the American deserts and the rattlesnake have been eaten in pinches—but the goanna is coarse of flesh, and is said to taste like sheep dip.

George Blaxland gained the first clumps of mallee—dwarf and tired looking eucalyptus—which dotted the dusty sheep range back of the town of Sydney and the convict barracks. Here was the first crucial test of escape. Thirty-four miles of rolling, somewhat broken, but almost shelterless land lay between him and the first gorges of the mountains. The small streams here had dried up months ago. He would be pursued immediately, probably by the prison's prize pair of blacktrackers imported from Van Dieman's Land.

Once out of sight, the fugitive detached the bayonet and flung away the musket. The eighteen inch triangular needle of steel was a splendid weapon for close personal combat, but a lot of grinding and honing on stones would have to be done before it could serve as a knife.

"Maybe I can make a spear and use it for a point," reflected Blaxland, slowing his dogtrot now to a long, distance-eating stride. Behind him the bell tolled the alarm, and there were faint noises of activity in and about the barracks; but so far there was no dust of a pursuing party in the still, dry air.

A dull, rolling rumble caused him to look up, startled. Far ahead there, above the height of the mountain barrier, a black storm cloud was rising. Its opaque heart was split asunder by the crooked tines of forked lightning. A storm coming! It had not rained for eight months in Sydney; and with the other newcomers, Blaxland had rather taken for granted that it never did rain. If the mountains only did not condense all the moisture now in those clouds—why, he would be safe from pursuit!

More than that, the sheep raisers and farmers would be so overjoyed at rain, that they would forget all about the escape of one probably crazy convict, fled to perish in the wild gorges of the Blue.

Just the same, Blaxland cut away at an angle from the straight line of flight, and sought a high, rocky ridge. Here his footprints did not show at all to an untrained eye; and with help of wind and perhaps rain, he hoped they would be too scant sign for even blacktrackers. These strange but highly skilled natives had the reputation of being able to follow cold and invisible spoor, where even bloodhounds were at fault.

Though he never once saw them, at almost this very moment of afternoon they were put on his track. They followed for perhaps two miles—and then deluging rain descended. Chisholm, the warden, and the guards with him, then called back the backtrackers.

"We'll pick him up sooner or later," said the warden grimly. "Ain't a bit of use taking too much trouble, with those mountains for our outside prison walls. Can't get away anywhere, can he?"

WITH which unanswerable argument the case rested—insofar as the convict settlement was concerned. All sheep stations and farms were warned to be on the lookout for the desperate red-head, who would be driven by famine to some attempt at breaking and entering; or perhaps to a holdup. A reward of ten pounds was posted George Cecil Blaxland, dead or alive—a contemptuous gesture, indeed, toward a man whose ancestor was that warrior king of the Franks, the father of Charlemagne...

The heavens opened and a cloud-burst smote the thirsty land. For two hours, as Blaxland trudged doggedly westward, blinded now by the sheets of water that sluiced into his face, the eight inch layer of dust underfoot still clogged on his feet in rubbery mud-balls. Then gradually it changed into a slithery, homogeneous mire, treacherous for footing, but not so heavy. The dry washes and old stream beds became rivulets.

In the blue-black twilight of a thunderstorm sunset they were brimming rivers, hastening with their new loads of silt into the mysterious heart of the mountains, bound for that mythical inner sea of Australia in which the best theorists of that day sincerely believed.

Blaxland made good progress. Just before total darkness came he found an empty hut used as a line camp occasionally by sheepherders. Here he flung himself down upon a heap of dry and brittle branches which had served someone as a bed, and slept.

He awoke with the rising sun slanting into his face through the door-less doorway. Refreshed but ravenously hungry, he knew he had to work fast and reach some kind of a base where he could lie hidden. First, however, he had to have food and at least a sketchy outfit if he would survive.

"I'll never be taken alive!" he said aloud. "Better to starve, or to fight it out to the end."

Still carrying the pick, and with the unsheathed bayonet thrust backward through the waistband of his trousers, he started on westward, seeing a height of land from which he could see the ocean and the town of Sydney—and also from which he might glimpse an outlying farm which it would be possible to raid.

The mountains seemed no more than a mile or so distant in the clear, refreshing morning that followed the storm. Everywhere the ground steamed; and in a miraculously short while the earth, so dead with the long drought, would be sending up new shoots of grass and other verdure. In three days the whole dry valley would be carpeted with flowers and for the time being the drought would be forgotten.

A half hour later the fugitive reached the summit of a bald rock shaped like the prow of a great rusty ship; and from here he scanned all of the ground between himself and Botany Bay. There was no evidence of pursuit, and he turned about, satisfied.

There was no building or sheep station in sight, barring only the empty shack in which he had spent the night. But over the long brown crest of a ridge to northwestward, Blaxland discerned a column of smoke which meant human beings.

On the side of the slope, as he climbed, he encountered the gaunt figures of a small band of Merinos. His eyes narrowed as he looked at them. They would have to serve, if he could not get other food soon, though the starved creatures looked as though there would be no meat at all upon them. The thought of raw mutton made him grimace; but the fare of the prison transport had cured him of squeamish nonsense forever.

WHEN he reached the crest of the ridge he took one look—and instantly dropped prone. Almost directly below him, in a sheltered elbow of the higher ground, nestled a one-room cabin of the type later to be known derisively as a gunyah (native name for a hut). Extensive sheep pens looked well kept, however; and Blaxland guessed this was one of the small outfits which had copied the idea of John MacArthur.

Smoke still rose from the clay chimney, but no one was in sight. Quietly the fugitive withdrew, then made a half-mile circuit, descending to the valley and approaching the cabin from the direction of the pens.

Though Blaxland gave the matter no thought, he was a truly fearsome object when he dropped the pick and came forward crouching toward the blind side of the cabin. His clippered cheeks and scalp looked on fire with an unholy orange-copper glow. Arms and chest, except for what looked like a fallen Vandyke of red hair just over his breastbone, were almost spectrally white.

And if one caught a glimpse of his back and shoulders, they were ribbed white in crosswise scarifications, like a washboard.

The prison dungarees had shrunk from the rain, and were halfway to his knees—and tight about the thighs. He was barefooted, of course; but since reaching Sydney the soles of his feet had toughened. He was not troubled on the plains, though before he could hope to win through the Blue Mountains he would have to get adequate boots somehow.

Fortune had decided to smile on him for a change. He had chanced upon the habitation of one Pete McCulley, who was a hermit sheep raiser through the unanimous though tacit vote of his neighbors—and of the townsmen and settlement officials as well.

McCulley was a black Scot, six feet three of stature, and with brows that made one jet smudge across his low forehead. He had been branded in Glasgow with the block T, which warned every chance acquaintance that he was a twice-convicted thief. So when he had tried the same game in Liverpool, they gave him short shrift. They cut off his left ear, sentenced him to a year in chains and perpetual banishment from the British Isles.

He had owned some property, though, and so when his chains were struck off and he was free to become an Australian colonist he obtained the money and invested in a band of sheep. The venture had not done well; and yet Pete McCulley's larder was always well stocked, and there were always jugs of white rum buried under the floor his cabin.

When Pete rode in on his rare trading visits, other men watched him warily, for he was always quarrelsome. He had trained his long black hair to cling wetly to his forehead, covering the T-brand. Yet everyone knew it was there, just as they knew that Pete McCulley would remain a wrong 'un as long as he lived.

This morning, the branded hermit was ferocious of temper. He had slept badly, awakening with an attack of shakes before dawn. These had been cured with several swigs of raw rum; but now that he was dressed and up, he felt sleepy again. There could be something done now with the remnant of his herd, since a few days would see the spinifex and more tender grasses green on the hillsides. But Pete let his damper burn while he sat with his head in his hands.

With a curse he threw it out of the door.

The billy was boiling with an extravagant handful of tea in it. He swilled down a pint tin cup of it, cooled and laced with rum, and then momentarily felt better. Stretching, he raised clenched fists and hammered them on the low roof. Then he walked to the open door—only to bring up with a growl of wonder as a pink-headed apparition came from nowhere and thrust the point of a long, keen dagger against his stomach!

"Hands up! Hold them there and back up!" commanded George Blaxland, wishing he had a pistol so he could carry through this act in approved highwayman style.

"Huh!" grunted McCulley, still doubting his eyes. "Who are you? And what d'you think to gain from any stand-and-deliver on a lone sheepman? I have no money—"

"Gold's of no use to me," said Blaxland. "Turn about."

Rapidly he ran a hand over the giant's anatomy, searching for weapons. There proved to be a long knife in the right boot, but otherwise McCulley was unarmed. Tossing the knife out of the door, the intruder reached around to unbuckle the hermit's belt, intending to use this to bind the giant's wrists.

THAT was the Scot's opportunity, and he made use of it. Suddenly bending forward away from the knife point, he thrust back one leg in a raking motion. Surprised, and with no intention of doing more than threaten with the bayonet anyhow, Blaxland found his own legs swept from under. He fell heavily, dropping the bayonet. And with a roar of malicious triumph, the branded hermit swung completely about and dove for him on the floor, great arms extended for the bear hug of the rough-and-tumble battler.

A fencer of fair skill, and champion of his form at Eton at schoolboy fisticuffs, Blaxland was agile for a six-footer. He partially dodged the diving lunge, and slammed over a terrific right hook to McCulley's ear as the latter descended.

As a result the surprised hermit found his forehead and nose smashing down to the floor, while his death grip on the robber did not materialize satisfactorily. McCulley scrabbled awkwardly on the floor, rising to his knees, pawing for the clinch which never had failed to bring him a chance for gouges, bone-breaking, and final victory over an opponent.

He got Blaxland's corded but slender left wrist. But just then the fugitive slammed the heel of his open palm squarely into McCulley's nose. Blood spurted. The blow, even more effective than the impact of a clenched fist, blinded the hermit with pain. His grip on the wrist loosened.

Instantly then Blaxland wrenched free, and came to his knees, then to his feet. One backward step, then a crouch and a powerful uppercut punch as McCulley staggered up to go blindly for him, and there was a crunching impact which no one could mistake.

Even Blaxland knew this was enough. He stepped back. The giant's arms fell limply to his sides. The black irises of his eyes turned skyward. Then he swayed forward slowly, still erect, and fell forward as a ladder falls, striking with a concussion which shook the flimsy cabin.

For a moment then Blaxland feared seriously that he had killed the man—and murder of a free settler who had done nothing to him was not in the convict's calculation. A short examination was reassuring enough, however. McCulley lived. His jaw was canted sidewise, broken, so he would be miserable and vengeful enough, but his heart beat strongly. In a quarter hour or thereabouts he would awaken and start planning a murderous reprisal.

One glance at the branded T on the hermit's forehead removed Blaxland's last qualm. This was necessity, of course, and he would have despoiled anyone of the outfit he had to have; but it eased conscience to know that the victim was a man who had stolen from other men.

Just as the man on the floor groaned and stirred for the first time, Blaxland quietly left the cabin. On his feet were stout boots, a trifle large but of excellent quality. He wore a flannel shirt, brown corduroy trousers with the ends tucked into the boots, and a broad leather belt from which depended a pistol, McCulley's knife in sheath, a filled powder horn, a leather pouch of bullets, and a sack containing flint and steel.

On his shoulders rested a light pack containing condiments, flour, sugar, tea, salt pork, a coil of light rope, and a haunch of boiled mutton wrapped in cloth.

Noon found him sixteen miles to westward, in the foothills of the Blue Mountains, apparently unpursued.

Dropping his pack, he lighted a fire for tea and damper.

Australia's first bushranger had taken to the mallee.

ALONE. The first day or two, finding a deep niche in a canyon wall where he could cut branches and fashion a hidden shelter which would serve as a base camp, the verve and inspiration of escape from chains held up Blaxland's spirits.

Then came inevitable reaction. His first gallant attempts to thread the mazes of canyons, or climb more than a little way toward the high ridge to westward, met with the same rebuffs all the exploring parties—from those of Bass, Governor Hunter, Bareiller and Caley, up to this last unfinished attempt by Lawson and Wentworth—had suffered.

Scaling these vertical rock walls was impossible in most places. Threading the faces of the cliffs, hanging always above a sheer drop to the terrible prickly pear beds below, got nowhere. Each time Blaxland thought he was making progress he came to a dead end and was forced to retrace his steps.

He became moody, thinking of the sweet girl whom he always would love but who doubtless would forget him, after a few days of tears, in the gaiety of London and the attentions of—Bathurst.

"Damn Bathurst!" he gritted aloud, but then he shook his head. The English lord had an excellent reputation; a widower, he had devoted himself to serious things, instead of following the rakehell course too common among his kind.

His courtship of Elspeth had been a dignified and flattering affair; and probably the only reason he had lost out in the first place to the redhead had been the latter's impetuosity. Now it was certain in Blaxland's mind that Elspeth would become Lady Bathurst. Separated forever by the width of a world, and the insuperable barriers of disgrace and banishment from the youth she had loved, that certainly was the common sense solution. Yet what real man ever yielded the first love of his hot-blooded youth to common sense and resignation?

All the while his brain was saying one thing, Blaxland was planning, hoping, striving to overcome in some fashion the insuperable odds. Ten days of complete failure dragged by, and his provisions were almost gone. He had shifted his base camp twice, working gradually northward; out so far even the most reckless climbing and arduous clambering along the rocky falls of the Nepean River had been fruitless. It began to look as though these thousand-foot cliffs extended without a break—save for the roaring torrents which no man could wade or navigate—the entire bow-shaped length of the Blue Mountains.

Blaxland had browned and toughened. His shoulders were broadening, his stomach growing flat and plated with muscle. He stooped a little from so much climbing where hands were ever more valuable than feet.

He had resolved upon another raid for supplies—other than mutton, which he had killed and eaten whenever he needed fresh meat. So far three of John MacArthur's lambs never would bring wool to the shearing shed; but a straight diet of lamb or mutton palls quickly on any palate.

There was a somewhat larger cabin some two miles to the east. Blaxland resolved to raid it the following night; but that raid was to be postponed, for an unexpected reason.

At sunrise the outlaw emerged from his cave camp to see the smoke of a campfire about half a mile to the west—and higher into the mountains than he thus far had been able to penetrate.

It was the base camp of Lawson and Wentworth, though he did not know that. He set himself the task of climbing and reconnoitring—only to discover to his bitter disappointment that reaching that high shelf from which the smoke arose was a job for two men with ropes.

One man alone could not hope to attain it—at least, not from the approach Blaxland tried. There might be another route through another of the canyons which crossed and crisscrossed back in a bewildering maze.

That must have been the case; for just as Blaxland was turning back he froze, gripping a projection of rock with one hand. Down there, just the other side of a narrow rock divide from the spot of his own camp, he glimpsed a man's figure.

In this lonely land any man at all was a cause for wonderment. But this one, scrambling down over jagged boulders, leaping short distances, climbing rapidly when an obstruction intervened, held the bushranger's rapt attention. Where under God's canopy did he think he was going in such an all-fired hurry?

Then right there in plain sight the ant-like figure halted. He seemed to shove mightily against the brown rock. A piece of it swayed, then rolled over, revealing a black dot which Blaxland guessed to be the mouth of a cave.

The human ant bent down and disappeared.

THEN minutes later, as the bushranger still watched, the man reappeared. He was carrying something on his back now, and hastily he retraced the difficult course he had come. In fifteen minutes he was out of sight, even though Blaxland slid and crawled down to try to follow his path. "Going back to that high camp another way," decided the watcher. "And down there's his cache..."

This raid upon the cave and the provisions, ammunition and tobacco he found plentiful there was an entirely different thing to Blaxland than the armed robbery of the T-branded sheepman, McCulley—though both crimes would be entered against his score as heinous.

Setting his jaw sternly against sentimentality, he helped himself to all he could carry, making a dent in the surplus which the two men had been unable to carry with them into the higher camp.

On leaving, however, he hesitated. With pencil, on the top of a packing case, he scrawled a message:

I expect to pay for all this provender if I win through alive.

G.C. Blaxland, Bushranger.

He had coined a word which would resound through Australian history for the next hundred years.

With sufficient essential food now for many days, Blaxland shifted his camp a mile farther to the north. He saw the approach this other explorer had used, and passed it. Leaving the river behind (one stream or another always had seemed the obvious means of attacking the problem of the mountains), he skirted a low, brown ridge. Then on impulse he halted. What could lie on the western side of this hogback which by dint of some hard climbing he surely could surmount?

Making a temporary cache of provisions, he set forth; and two hours later he attained a better coign of vantage than he had won at any time previously. Over at his left and ahead, hidden from view, was that camp of the other men which sent up smoke at regular intervals. They did not seem to be moving forward; and the truth which Blaxland could not guess was that a minor misfortune—a shower of rock dust in Lawson's eyes, causing inflammation—had made them wait three days.

The night Lieutenant Wentworth, visiting their cache again, made the infuriating discovery that they had been robbed by some unknown person named Blaxland. He carried the news over to the nearest sheep station, whence in due course it was reported to the prison warden and Lachlan Macquarie.

If the guards were able to capture the self-styled bushranger now, he certainly would be hanged; and even for the sake of Bathurst the governor would not interfere.

With the clue of his known presence on foot in the broken country near the cache, the prison warden, Chisholm, sent a squad of guards converging from a wide fan formation and closing in on the mountains at this point. It did not seem possible that Blaxland could escape; and the theory was that he had holed up in one of the few caves of the region, probably one where there was some seepage water available.

But in spite of the fact that they bivouacked right there, and searched each day from sunrise till dusk, they failed to catch a glimpse of the badly wanted man.

Blaxland had seen them first. Unable to go back now, even to raid again when these provisions were used, he faced grimly to westward. There on those heights he would find triumph—or death.

A FULL week of elimination and failure dragged past. Blaxland had found no way to scale the vertical cliffs, and so had devoted himself to exploring three branches of canyon all of which elbowed at various angles but kept a general westward direction.

The northernmost of the three led him fully two tortuous miles. He climbed along the side, above the deadly cactus waiting to spear and entangle him the bottom of the gorge, only to find himself in a cul-de-sac at the end, faced with cliffs of brown sandstone and scaling shale. He had to turn back, jaw set grimly.

Two more chances—perhaps.

On the second canyon side he suffered a fall, bruising one shoulder, arm and hip painfully. But he gritted his teeth and kept on. Time now was getting precious—time and food. Over there somewhere he realized that a pair of determined rivals were assaulting the heights. They might well be succeeding where a man alone could only fail. If they won through first, then all for which he had gambled would be lost, and his own life forfeited without recourse.

In desperate striving where dogged resolution holds a man to a task called hopeless there almost always is a further urge which becomes a sort of madness. Blaxland knew his love was hopeless. Yet through these days when brain as well as tendons seemed strained to the bursting point, he cherished the illusion that up there ahead the sweet face of Elspeth Stuart watched him, smiling with confidence.

"I'll win, and find you somehow!" he repeated aloud many times, refusing to think of the disgrace and the twelve thousand miles of distance that lay between.

The second branch canyon promised more, once Blaxland passed the first precipitous elbow. It angled back to the south, but there was a branch from it going due west. The sides of this looked more shelving and broken. If only he could descend to the bottom of the gorge, hack a way through the cactus, and gain that branch canyon!

The whole of the first day he spent in approach and reconnaissance, finally sleeping right there on the edge of the cactus without returning to his base camp. Time enough to go back for supplies, beyond the cold damper and water he had brought along, when he made a start through the prickly pear. It towered over him there in the bottom of the gorge, and a strong odor, ranker than any recognized perfume, hung in the heated air.

With sunrise he was up, and hacking a sort of tunnel through which he could crawl across the gorge on hands and knees. It was slow work, for as soon as he had cut an amount of the thorny stuff, it was necessary either to carry it back and out, or else to thrust it piece by piece into the tangle at the sides of the tunnel.

He made one trip back, dragging all he could bind in his rope, when a startling interruption occurred. Up there high to the south, crawling along a shelf of rock—backward into the same canyon he had been traversing—came two human figures linked together by a rope.

His two rivals in this exploration!

Instinctively Blaxland, thinking then perhaps these might be prison guards instead of the explorers, went back into the mouth of his cactus tunnel. He lay down, watching upward, and in a few moments realized that he had not been seen. These were the explorers, and they followed this canyon back the way Blaxland had come. They appeared to be having a terrible time up there, three hundred feet above the cactus gorge, hauling themselves one by one along a broken shelf, helping each other across gaps...

And then it happened!

One of those human ants appeared to slip a distance of about one inch—on the scale, that is, of Blaxland's vision. Instantly there came a puff of brown dust up there on the side of the cliff.

A rumble of falling rock, faint at first, then mounting to a roar.

Scaling away unevenly, hundreds of tons of the cliff face slid down the eighty degree angle and crashed into the cactus, not a hundred feet from Blaxland!'

"God pity them!" was the horrified exclamation wrung from the bushranger.

FOR a half minute he could see nothing, for the brown dust like chemical fumes hung against the cliff side. But then a wind came and it moved sidewise slowly, like a curtain being drawn—and Blaxland scrambled out to his feet, a prayer and a curse of wonder on his lips.

There perhaps sixty or seventy feet below the vanished shelf, two motionless figures dangled and swayed above vacancy. Their rope, attached to both men's belts, had caught upon some precarious projection, halting their fall!

One moved a little. The other was limp. Evidently the shock and the falling rocks had killed or knocked out one, and hurt the other badly.

Blaxland wasted no time. Within a space of seconds he was at the most favorable spot of approach, and climbing the gritty rock face like a human fly climbs the face of a building. When he chanced an upward look he could see one of the two men writhed a little, lifting an arm, then letting it fall. If only he did not move enough to displace the rope!

The first hundred feet offered three spurs or shelves where Blaxland could relax and take his bearings. He saw then that he had to go far to the side, then follow what looked like a fissure or shelf slanting upward until it was directly under the dangling men.

Twenty minutes later, with both victims of the fall quiet now, he was about fifty feet to one side of the point where the rope had caught, and a little above it. He shuddered to see that the rope had hooked across what appeared to be a rock anvil. The base was wide and heavy enough, but the projection looked as though it could not hold the weight. And the rope was out within a foot of the projection's tip!

In a cold perspiration for all his exertion, and trembling, Blaxland at last crawled to the anvil base. Here he rapidly unwound his own rope from his waist, peered over to gauge the distance to the narrow, slanted shelf below, and then coolly looped his rope under the other in such wise that both loose ends remained in his own grasp. Then sitting astride the anvil, praying that it could stand just one more stress, he eased off the caught rope, and strained until the veins came out like cords in his neck, at the jerk which ensued.

The anvil held, however; and a few seconds later Blaxland breathed in relief. Both limp bodies were on the shelf, and he pulled free the end of his own rope.

From here he had to ease the victims one at a time, to the bottom of the gorge, where he examined them. One man, he who had writhed at the end of the rope, suffered with a broken ankle and cave-in ribs on the right side. He also might have internal injuries from the jerk of the belt, for he too was unconscious now.

The other man was gory of scalp and face, and unconscious with concussion. Both might live, but they would have to have better help than the bushranger could offer.

All the rest of that long winter's day was taken in the task of moving both men back to Blaxland's base camp, and there applying restoratives and rude bandages. The man who identified himself in a husky whisper as Lieutenant Wentworth, came to full consciousness, though he seemed the more badly injured of the two. Lawson was the other's name, and his concussion was serious.

When night came, Blaxland told them he would go for help.

"I'm squaring up the robbery of your cache," he told Wentworth grimly. The soldier answered nothing, but followed him out of the small circle of firelight, with wondering eyes.

Insult was heaped upon injury as far as the sheep hermit Pete McCulley was concerned, that night. The self-styled bushranger robber who had made him stand-and-deliver after a bruising fight, returned and held up Pete again with the latter's own pistol!

Pete, awakened from a sodden sleep, fairly foamed at his bandaged mouth. The scoundrel was wearing Pete's boots and corduroy trousers, too! But there was nothing for it; Pete had tasted Blaxland's mettle once, that was enough. Full dressed as he always slept, he arose, growling threats, and preceded Blaxland out into the night.

Back at the camp the bushranger curtly explained. These two were important men in Sydney. Pete must go instantly and bring a doctor for them, and competent help. Blaxland motioned him off into the darkness.

"Remember, Pete McCulley," he said in grim conclusion, "I hold you responsible. If harm comes through your neglect, I shall return in the night some time for you!"

With an involuntary shiver, the sheepman set off for the nearest settlement. He had horrors enough that came in the night, without adding this bloodthirsty bushranger to them.

Blaxland moved fast. He gathered a pack of essentials, bade two unfortunate explorers farewell, and set out in the night. When he had gone far enough toward the cactus tunnel in the gorge, to feel safe from night searchers, he turned in and slept.

At the first streaks of dawn he was up and away, omitting a breakfast fire this time for fear of pursuit. But there was no pursuit. Care of the wounded men claimed all the attention of the helpers Pete McCulley brought. And Blaxland trudged on, reached the canyon where he had started to tunnel through four hundred feet of prickly pear—and found, miraculously, that the tunnel now was unnecessary!

The landslide from above had rolled out over the bottom of the gorge in a long triangle which almost crossed; and under the shale and sandstone the prickly pear had been crushed flat and buried. Blaxland reached the further side, and a side shelf of rock on which a wagon could have traveled, with no more than a slight struggle of a few moments with thorns!

"It's an omen!" he told himself joyously, seeing how the way mounted now, curving about and going steadily toward a V-notch in the blue wall of mountains. "This is the Bathhurst Road to Eden!"

THERE in the notch of the Blue Mountains the lone white man stood and looked down upon the western slope, and upon the great plain stretching across mallee, desert, mulga and jungle a full two thousand miles, to far-away Northwest Cape on the Indian Ocean.

A breathless wonder filled him, a wonder that grew and grew as he slowly descended. Here was a land of giants, of abundant rainfall, of queer wild creatures that squatted on their hind legs like a kangaroo mouse, and leapt—good Lord how they leapt!

The first three big kangaroos Blaxland saw frightened him worse than he frightened them; but soon he realized that they were not dangerous if undisturbed. He kept on. At night he camped, and the next day kept on. He meant to hold the V-notch in sight at his back, but to penetrate a little distance for the sake of killing some fresh meat, and of getting an idea of the country.

It was a mallee scrub, but what mallee! Here the eucalyptus, no more than twenty feet high back at Port Jackson, really reached its glory. It was here the only tree on Earth taller than the California sequoia, and deepest green of its luxuriant foliage.

Other trees of immense size were the collibans, the cypress pines, bloodwoods, ironbarks, with kurrajons and other species of bottle trees crowding the spaces below quite as milkweed, pitcher plants and goldenrod crowd the footing in lesser forests.

Almost at once Blaxland got into trouble. A small joey hopped up to him, unafraid, and he seized it—without meaning it any harm, but out of sheer curiosity and a wish to look at it closely. That act nearly cost him his life.

Out of the forest hopped a huge old man kangaroo, chattering fury. One of these will seize a man, and disembowel him with a stroke of a powerful hind leg. But this time Blaxland let go of the joey, dodged, and then when the old man came again, let him have it with the pistol, through the chest. The big kangaroo fell kicking; and Blaxland's meat problem was solved for the little time he had a meat problem.

Making camp right there, he skinned the big wallaby, roasted and ate his fill of the tough meat. In the morning he would start back for his triumph—and his pardon at the hands of Lachlan Macquarie. The route he had come would be difficult but by no means impossible for men on foot. Immediately the way was surveyed and known, however, the prison governor could detail a thousand convicts to road building. In a year, two years, there would be wagon teams hauling settlers into the new country...

The Bathurst Road! Blaxland saw enough to make him supremely happy, even though he could not envision the beautifully engineered, broad concrete highway of the future, with its stream of high-powered cars threading in a couple of hours the barrier of the Blue Mountains which had balked all man's efforts but his own, for more than forty years.

Alas for dreams of immediate pardon, of a ship back to England—and of Elspeth Stuart. Too filled with his own achievement to be sensitive in the manner of those who claim a telepathic sixth sense, Blaxland gloried in the great gum-trees which towered above his little camp—and did not suspect that before sunset two score of immensely tall black figures, naked and unadorned save for white striping which made them look, in the dusk, like animated skeletons, peered with fear and wonder at this strange apparition from another world.

To the savage Parrabarras this being, with hair and face the color of the storm sunset, and skin as pale as the browned, dry grasses of the plain, was undoubtedly a species of bunyip (monster)—if, in truth, he was not Molongo or another of the chief demons of the scrub, in person. He seemed rather undersized to them, who share with the Kimberley blacks and the Aruntas of the western plains the distinction of being the tallest human beings in the world; yet why should not Molongo or Old Mooldarbie himself appear in any guise he happened to fancy? Surely this fiery hair belonged to a demon!

AT sunset the blacks silently withdrew, since they fear the dark and hide from it in their wurleys. But with the first streaks of gray in the sky they were up, chattering and excited. From a distance of a mile or so the awakening white man heard a council or corroborree.

Blaxland had been kept awake part of the night by the slinking dingoes, who wanted the carcass of the kangaroo. This morning he shrugged, and started preparations for breakfast and a quick return.

He was not to make it. The far-off clamor of corroborree ended. Some fifteen minutes later Blaxland looked up with a twinge of horror in his heart, to find himself circled by more than eighty painted black warriors, completely naked, and armed with spears, waddies, and queer looking black elbows of darrah wood he soon would learn were specimens of that queerest of all weapons, the boomerang.

He quietly stood up, hand on his pistol, looking desperately for a chance to fire and run for it. The chance never came. The circle of blacks slowly closed—not without some of the more timid members edging away to the back of the braver ones.

They closed. Careful not to harm this demon, they nevertheless urged him along, and Blaxland finally saw it was necessary to acquiesce. He accompanied them; and in the village of the Parrabarras there was feasting and rejoicing. Had they not a captive demon who undoubtedly would cast evil spells upon all enemies of their tribe? They would keep him forever...

And Blaxland, finding himself guarded in a special wurley, offered everything a god or demon should have—save liberty—was forced to make the best of a terrible happening.

Months passed. The chill months of summer faded, and autumn—the spring of the Antipodes—arrived, bearing with it another drought and a specter of famine. This was the December when so many of the colonists surrendered, packing up their goods and crowding into Port Jackson to await the coming of the first food ship on which they might return. If they had to be paupers and starve, they preferred doing so in the land of their birth. There was no future in farming or sheep-raising in this dreary land hemmed in by the throttling circle of the Blue Mountains.

On the day before Christmas, when all thirty thousand of the colonists and convicts had been on half rations a fortnight, the food ship did come. Something like a riot occurred when all of the waiting, desperate ones tried to go on board with their effects before even the cargo could be landed.

IN the confusion two passengers came ashore—a heavily veiled young woman, and her brother who acted as her escort. These were the two Stuarts, and they bore with them the King's pardon for a convict named Blaxland...

"I regret exceedingly, Miss Stuart," said Governor Macquarie gravely, "that I can do nothing for you and your brother. Lord Bathurst's efforts for Blaxland have been wasted. He is gone—probably dead. It is perhaps the best thing, after all," he concluded with a touch of grimness, "since in that case he cannot be tried for breaking prison, and for robberies committed after his escape!"

He started up then, as did Ronald Stuart, for the girl—borne up through all the trials of the long voyage by the hope of having her fiancé restored to her—had fainted. All in vain. The name of George Cecil Blaxland was stricken from the prison rolls; but three counts, two of them capital charges, remained against him if he ever should return.

The second day following, a grim, stubborn man set forth on horseback to ride the parched sheep range. John MacArthur would never surrender. He saw ruin now, unless rains came almost instantly. Yet he should hang on until his last Merino sheep died of hunger.

In the broken hills of his western range MacArthur reined to a stop. Just ahead there was a slow moving cloud of dust—a band of sheep? He knew of none which should be here.

Then as he rode forward he came upon the most startling sight ever to come to the eyes of a Port Jackson setter. Here were seven almost naked men, six of them glistening black and so tall* that their heads reached even with his horse's ears!

[* Many of these natives are seven feet tall.]

The seventh man was shorter, not much more than six feet—and he was white!

Spellbound, MacArthur sat there, hand on his pistol. He saw the white man turn and harangue his six companions in a guttural language unknown. The six spearmen halted, casting lowering glances at the horse and its rider. A horse, of course, was an unknown species of bunyip, to them.

Then Blaxland strode forward. He was the color of Burley tobacco, from the sun, and his red hair and beard had grown long in eleven months of his captivity and wandering with the nomad Parrabarras. Yet he had a quiet assurance in his manner.

"Sir," he said in a rich, resonant voice, "I bid you carry the news to Governor Lachlan Macquarie that Blaxland, the bushranger, has returned to show him to the road to the interior of this continent! And to claim the full, free pardon promised for success in penetrating the Blue Mountains!"

MacArthur had to know more. Who were these blacks? How had Blaxland managed to control them?

The ex-convict told his story briefly. He had learned the tongue.

The tribe had wandered, and after nine months he had gained ascendancy over them, through use of his pistol and through knowledge they did not possess of some simple cooking, and medicine. He had induced six of the finest warriors to accompany him as a bodyguard back into the land beyond the mountains. He had promised that they should return safely...

The presence of the blacks was incontrovertible proof that Blaxland had done as he said. So, bidding them go to his home and refresh themselves, the excited sheepman galloped away. His brain was filled with plans for taking the remnants of his sheep bands through the mountains to this wonderland of luxuriant pasturage. Perhaps he could make the grade, after all!

EARLY that evening Lachlan Macquarie, Chisholm, the prison warden, and thirty armed guards came. They were accompanied by all the vehicles and riding horses available at Port Jackson. And miles back of them hundreds walked who could not ride. The news was the most exciting that ever had reached Botany Bay.

One sight of the giant blacks with Blaxland, and Lachlan Macquarie was convinced. He took the bushranger with him and several of his council and listened while Blaxland gave a brief chronicle of his eleven months beyond the law.

Lawson and Lieutenant Wentworth were there, the latter to corroborate a part of the tale, and also to grip the hand of the man who had saved them from a miserable death.

In conclusion Blaxland showed a red-marked map he had made on rough paper hammered out of the pith of the nipa palm. This showed the route, and also two large rivers. One of these flowed to the northwest and seemed to end in great marshes—as far as the Parrabarras had wandered in that direction.

The second river flowed to the southwest, and was a mighty stream with a swift current—probably flowing to the fabled inland sea, as Blaxland believed.

After a study of the route which would become the Bathurst Road, the governor looked at two rivers. He smiled. He took up a quill pen and wrote one word beside each river. He was naming them. Wentworth, looking over shoulder, could not restrain a chuckle.

With the simple vanity of a great man, the governor had named the southern river the Lachlan, and the northern stream the Macquarie!

"Your black warriors will not molest my men when we go to prove this claim?" he asked. "Not that I doubt, but a road which we can use is an imperative necessity."

"I am chieftain of the Parrabarras," said Blaxland quietly. "I guarantee that they will be friends."

"A sort of king of the mallee," grinned Wentworth.

But now Lachlan Macquarie had his dramatic moment. "In respect to yourself, Mr. Blaxland," he said momentously. "Of course you broke prison, and committed certain robberies in order to secure provisions for your exploration. Ahem!"

Here he looked about, with not the ghost of a smile. The bushranger slowly paled, and his hand stole to the butt of his pistol. Was this respected governor going to go back on his word? Had all this striving been in vain?

"However," continued Macquarie ponderously, "I give you a full and free pardon for your prison break, and for those robberies committed afterward I cannot, I grieve to say, pardon you now for the treason you committed in England."

"What?" cried Blaxland sharply. "That was the proclamation you—"

Here Macquarie permitted himself a beginning smile. "I cannot pardon you—because the pardon was granted in England full five months agone! Wentworth, will you ask the king's messenger, bearing the pardon, to step into this room? "

The lieutenant obeyed. To the open doorway came Elspeth Stuart, clad in the duty veils of her journey from Port Jackson. Her eyes were filled with tears of happiness, though, and she had freshened her cheeks.

"Blax!" she said, in her well-remembered, husky, throbbing whisper. She lifted her arms, inviting him...

World Wide Adventure, Spring 1968, with "The Red Scorpion"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,