RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Green Book Magazine, August 1918, with "The Giant Footprints"

Detective Masters undertakes his most hazardous quest in this striking mystery story.

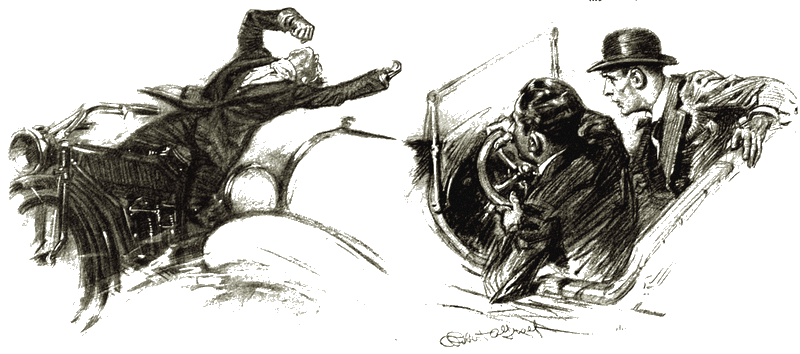

I hurled the thing back through the window. From

the street below followed a terrific concussion.

I HAD finished painting the Illman group, and I was itching for excitement and change, but even I did not suspect that Jigger Masters would have so much of it ready and waiting for me. It was my third visit to his apartments—and it came near being my last.

"Come in! Hold your hands above your head! Walk slowly, or I'll empty this automatic into you!"

This was my greeting. Masters sounded determined and gruff; so I chose to obey. Pushing the door wide open with the toe of my shoe, I crossed the threshold in the desired attitude, albeit grinning disrespectfully into the mouths of two very capable pistols.

"Don't let one of your fingers twitch!" I cautioned.

"Fool!" exploded Masters, putting down the weapons and rising awkwardly from his defensive position behind the desk. "From now on, when you break in on me, either knock or whistle! I'm shooting first and asking questions afterward nowadays!" He yanked out his swivel-chair and spread his lean anatomy over the seat and arms, jerking his thumb in the direction of the only other chair he possessed, a sway-backed contraption of wood and wicker.

"May I take them down now?" I queried in mock trepidation, seating myself gingerly. I was inclined to make light of the heroics in spite of my knowledge of my friend's constitutional seriousness.

"Yes," acceded Masters gruffly. "You'll need them if you stay."

Crash!

The pane of glass in front of me splintered to bits as a heavy, round object caromed from my chest to my knees. Involuntarily I seized it, and my eyes popped nearly from their sockets. It was a hand-grenade with the smoking fuse burned nearly to powder! With a convulsive movement I hurled the thing back through the window. From the street below following a terrific concussion that smashed in the rest of the glass of the window.

As I jumped to the jagged opening, I had a momentary glimpse of a struggling horse in the midst of a black, round cloud of smoke. At that second Masters dragged me back.

"There may be more coming," he said in a calm tone.

I faced the window hurriedly. "Nice quiet little nest you have here! What is it all about, anyway?"

He pressed one of the automatics into my hand and wheeled about. "Time enough to explain later! Come on!" To my surprise, for I had not suspected the existence of any other doors than the one through which I had come,—he pushed aside the tawdry gilt mirror which hung on the east wall, revealing a spiral staircase, black and musty-smelling.

After feeling my way down at his heels for what seemed an interminable distance, I heard him fumbling with a lock. Then came a click, a creak, and I saw a narrow aperture of light below, and Masters' eager face in silhouette.

"If you see anyone with immense feet, cover him!" he admonished. I had a queer, shivery thrill at this, but as he stepped out into the court and closed the iron door, I had no time for questions. Masters swung out immediately toward the street, with me on his heels.

A crowd had gathered already, and was packed four or five deep around some object on the pavement. After a minute's elbowing, Masters and I got close enough to see that it was a horse, lying huddled on the asphalt. Apparently the bomb I had thrown had exploded directly beneath its feet, for the animal was horribly distorted and mangled. Its owner, a Greek fruit-peddler, had been so overcome by the catastrophe that he was unable even to loosen the traces, but sat on the pavement, alternately bemoaning his loss and cursing in his native tongue.

After a quick survey of the crowd, which seemed to be the ordinary riffraff that always gathers about a street-accident, I saw Masters motion to me. I followed him to the outside of the circle, where he stopped a moment to jot a memorandum in his notebook.

"That was meant for us," he whispered. "I'll send the poor devil a check to cover the loss of his horse; guess I owe that much of a votive offering to my god of luck. Say!"

He stopped dead in his tracks and faced me, a frown of beginning exasperation wrinkling the folds of loose skin on his forehead. Gripping me by the arm, he led me back slowly toward the apartment-building we just had quitted. "I—I must confess, Hoffman," he said at length, "that I was a trifle rattled. Did you, by any chance, notice that bomb particularly before it left your hands?"

I smiled wryly. "Yes, I saw that it was lighted. That was all. Then I think that I must have started to pray."

"But did you notice anything else?" persisted Masters. "I couldn't swear to it now, but it seems to me that there was a piece of string—"

"White string, about a foot long!" I interrupted. "Yes, I remember it now."

Masters nodded shortly, and the corners of his wide mouth drew down a fraction of an inch. I knew the expression; it was his way of expressing disgust. In a weaker man the same feeling would have called forth curses.

WITHOUT further parley he turned in at the door of the

apartment-building adjoining ours, and after ringing the bell

held a short conversation with the janitor, and entered.

Three flights of stairs led us to the top floor, and there we found a ladder. This was built against the wall and reached to the ceiling. Above it was a trapdoor leading to the gravel roof. Without a word Masters climbed, threw open the trap and jumped out.

I followed in time to hear him utter an exclamation of satisfaction. "See this, Bert!" he cried, picking up a long bamboo fishpole from the gravel. Three feet of white string still dangled from the end.

"This is the way he sent us our little present. He tied it to the pole, lighted the fuse and then swung it out across the space between the apartments. When he thought the fuse was about gone, he oscillated the pole. The weight of the bomb threw it through the window-glass and at the same time broke the cord.

I shuddered at the remembrance of the missile landing in my lap. "He didn't miss his calculations by very much!"

"No," answered Masters abstractedly, "not very far, but a miss is—"

He did not finish. I saw him take a hand-lens from his hip pocket and bend down to the gravel. Without speaking, he examined the surface of the roof for nearly ten minutes. Finally, as he had worked his way nearly to the edge of the roof, I heard him chuckle.

"Yes, it's the same one," he muttered half to himself. "See here, Bert: you won't believe it, but I've got his footprint! Look through this glass!"

As I followed directions, he pointed with his index finger at a slight breaking of the surface where a bit of sand mingled with the gravel. As I squinted through the lens, his finger traced a line that led far backward.

"Not all that!" I exclaimed, remembering with a nervous thrill that Masters had spoken of immense feet. "All that!" he answered emphatically. "That's the size of the fellow's foot, whether you choose to believe it or not!"

"But that is nearly two feet!" I gasped. "No living person wears shoes that size."

Masters smiled mysteriously. "No, even I will admit that! Although this medium does not show it well, the person who threw that bomb was without shoes; the print is made by a bare foot, sixteen or seventeen inches long!"

In spite of my knowledge of Masters' lack of exaggeration, I scarcely could repress my incredulity.

"Did you read anything of the Stanwood murder?" he inquired tartly.

I shook my head, glad of the slight shift of topic. "When I am painting, Jigger, I read nothing but the editorials and the sporting-page. Regular news gets me too excited. I must have missed it—the Stanhope affair, I mean."

"Stanwood," corrected Masters. He turned to the trapdoor. "I'll tell you all about it on the train, if you care to come along. I'm going to the suburbs for a short trip."

"Count me in!" I cried cheerfully. The prospect of more real excitement was entirely too much for my prudence.

AN hour later, as we pulled out of the station, Masters

drew a clipping from his pocket. "This will give you the fully

decorated facts," he remarked, handing it to me.

I unfolded the sheet, and a scarehead story I had skipped in the daily paper met my eye.

GHASTLY MURDER AT ASBURNHAM

MILLIONAIRE STANWOOD FOUND

WITH HEAD NEARLY SEVERED

SUSPECT GIANT NEGRO

A barefooted fiend, wielding a razor-edged knife, last night committed one of the most brutal murders on record in New York State. Lester Maxwell Stanwood, the millionaire broker and clubman, was the victim.

According to the stories told by the servants at Cheshire Hills, the Stanwood country estate where Stanwood was staying preparatory to leaving for his summer outing with his wife and family in the Berkshires, Stanwood had seemed uneasy and irritable at the dinner table on the evening preceding the crime. He had instructed Segrue, the gardener, to fasten the huge iron gates and to loose his two huge mastiffs, Justinian and Theodora. He had spent an hour after dinner directing the packing of his trunks, and then had retired to his study and closed the door. He had appeared twice after that before the servants retired, once to ask Merkel, the house man, if anyone had attempted to see him, and the second time to make sure that his orders in regard to the gates and the dogs had been followed. Then he had gone back to his room, and nothing further had been heard from his part of the house.

In the morning Merkel attempted to waken Stanwood at nine o'clock, but found the room empty and the bed undisturbed. Alarmed, he had made directly for the study, where he found Stanwood slouched on the floor in a pool of his own blood, and with his head partially detached from his body by some edged instrument.

Merkel had aroused the household by his terrified screams, and then had fled, carrying his tale of horror to the Asburnham police station. A detail was sent out immediately to the scene of the crime, and a posse organized to search the surrounding woods for the murderer, for suicide was plainly out of the question.

Sergeant Hadley, in charge at Asburnham, visited the Stanwood home with Becker, a plain-clothes man. The first and most important clue they discovered was a set of footprints leading from the pool of blood directly across the rugs and bare floor to the doorway. The peculiar and immensely important fact about these footprints is that they were made by an abnormal foot—sixteen inches long from heel to big toe, and shaped more like the hand of a gigantic simian than like an Aryan foot. Becker pronounced it immediately the foot of a giant negro.

"That's far enough," broke in Masters, seeing that I had

read the essentials. "The rest of it is mere imagination."

"That is horrible, grotesque!" I exclaimed, handing back the clipping. "There isn't any creature living to-day which possesses a foot sixteen inches long, is there?"

Masters smiled enigmatically. "I told Hadley that, but both he and Becker swear by all that is holy that we are looking for a giant."

"Well, it's spooky enough to give me the creeps!"

"Yes," said Masters slowly, "it does seem that way. The footprints were there all right, and plain enough—too plain!"

"What do you mean by that?"

Masters shook his head. "It looks like a signature, Bert! If I hadn't seen the print in the gravel back there in the city, I wouldn't believe anyone had such feet. I'd call it either a deliberate blind or else the seal of a revenge."

"Had Stanwood any enemies?"

"Yes, one at least. His name is Parker; he lived on a farm back about three miles from Asburnham, but he disappeared a day or two before the murder occurred. He seemed to have had mysterious monthly conferences with Stanwood at which they often quarreled violently."

"Fairly obvious, then, I should say."

Masters looked as nearly uncomfortable as lay within the realm of possibility for him. "Ye-e-s, it does," he admitted. "In the ordinary course of things Parker will, of course, be apprehended. He then will tell some wild story to account for his flight—"

"Or confess to the murder," I interrupted.

"No, he won't!" said Masters gravely but decidedly. "I'll admit to you, Bert, that I have led Becker, Hadley and the constables of a half-dozen towns to believe that I want Parker for Stanwood's killing, but I haven't the slightest idea in the world that Parker is guilty! I want to have him safely lodged in jail almost entirely for his own sake!"

"Then you're afraid this demon is after him too?"

"I have every reason to suspect that is the case. Parker may be safe where he is hiding, but I'd much rather have him locked up in the Tombs. I don't exaggerate, Bert, when I say that this criminal—or 'S' as I know him—is one of the most diabolical plotters it has ever been my misfortune to encounter. I think he has just cause for revenge against both Stanwood and Parker, and the experiences I have had with him thus far lead me to believe that he has an extraordinary ability."

"How did you hear of him first?"

Masters smiled. "I invented a fairy tale. You see, when I got to Asburnham, Mrs. Stanwood and her two daughters had arrived. She is a fussy, society-loving old lady, and the girls are just as finicky. They were properly horrified at what had occurred, of course, but were not at all enthusiastic about an inquest and an investigation of the case. They professed themselves willing to have the police take charge, but were going to bar me from the premises. I pointed out to the chilly Mrs. Stanwood the one strange fact about the whole thing—namely, that through it all the two huge mastiffs had roamed at large on the fenced-in grounds, and that no one could have entered or left without first silencing the dogs or being attacked. I showed her that the dogs were unharmed; the servants testified that the animals had made no noise; and I hinted darkly that the murderer must therefore have remained inside the house. Rot, of course, but you should have seen those women depart! They scarcely were willing to wait for their hats!"

"I can't quite see—" I began.

"How this has to do with the mysterious 'S'?" Masters smiled. "The only thing I could get out of Mrs. Stanwood that seemed to pertain in any way to the murder was the fact that she had known her husband just twenty-three years, that he had come to New York from the West, and that she knew nothing about his life previous to that time. This made me slightly curious, and when I had a chance, I made for his study.

"There wasn't a thing there, however. It seemed that Stanwood's life began—so far as the records were concerned—at the time of his marriage. I found jottings of all kinds, mostly of financial deals, but nothing that I could fasten upon as furnishing any motive for murder.

"I didn't note it particularly then,— I'll tell you now to simplify matters,—but the name of this man Parker occurred nine times in the records, which I have little doubt were incomplete, at that.

"But my prize find was not in the study. I rooted around in every part of the house, and at last I located a small wall-safe in the attic. I asked the servants about it, but they knew nothing; so I used oxyacetylene on it. This was all it contained:"

Masters drew from his breast pocket a small, battered notebook that once had been covered in bright red leather but now was shabby, stained and peeled from long and rough usage. Wondering just what the contents would reveal, I opened it. Page after page of the first part had been written with a soft pencil; time and rubbing had made it absolutely indecipherable. Even after I reached the fresher pages, I could make out little, however. "Left Hon. May 16th with S. and P." was the first entry that seemed at all intelligible. Then came masses of figures that resembled vaguely the entries in a ship's log, though done roughly and evidently by an amateur.

"We're coming to Asburnham," broke in Masters. "I'll simplify it for you. Over here a few pages 'P' becomes Parker. 'S' never has his name spelled out. They refer to 'Oysters' five or six times. 'Arrived K' appears with a date that I can't make out. And over here at the back is an interesting entry, 'Left in sloop with P. S emptied revolvers but no damage.'

"As far as I can figure," continued Masters, speaking rapidly, "they were engaged in some queer enterprise off Oahu or Hawaii in the Hawaiian Islands somewhere. It sounds like pearl-fishing, only I never heard of any pearls coming from there. At any rate, they made money somehow, and then sailed off, leaving 'S' and the others behind. That part seems clear enough. There are a lot of other entries that I don't understand, however. They run like this, 'Four Kanakas,' and then 'Suspect B. He looks funny,' and then 'The whole bunch. Me for the States.'—"

"Sounds like a conspiracy," I ventured.

Masters shook his head. "There are just two men alive who can tell us about it, and they are Parker and 'S.' If I'm not mistaken, we won't have to wait many hours out here before we get hold of one or both of them."

"Are we going to Cheshire Hills?" I queried, rising as the train slowed down.

"Just for a moment. We'll get one of the Stanwoods' cars and go out toward Parker's house."

AN unpleasant surprise was in store for us at Cheshire

Hills, however. What must have been a beautiful country house was

now ablaze from basement to garret.

Masters gave one low cry of surprise, but instead of making for the little crowd who were vainly trying to subdue the flames, he caught my arm and made me run with him to the garage.

"He thought to destroy all the evidence!" Masters growled. "He beat us here. There, take the big car! It's a Peugeot."

I swung open the huge doors. A whirl of the starter, and the magnificent motor responded. Masters swung himself into the seat beside me as the car bounded forth on the gravel roadway.

"First turn to the right!" snapped Masters. "Then keep on as far as the Pontypridd Pike. Hang the speed-limits!"

It was my very first attempt at driving a car with four speeds; my little four-cylinder runabout could do only a chaste thirty-five miles an hour, but I knew the gear-shifting and the general details, and the magnificent machine under me almost ran itself. We reached thirty-five in the course of two hundred yards, and it did not impress me at all in the excitement of the moment.

"Let her out!" commanded Masters tersely, gripping the fore door and the back of the seat and leaning forward.

I complied, stepping on the gas until the smooth, silent motor in front of us transformed itself into a rushing tornado of Herculean endeavor. A bicyclist far ahead heard the cannonade of our approach and backed his flimsy machine far into the grassy ditch at the side of the road. In a sort of exalted bravado I jammed my left foot on the cut-out as we swirled by, and the answering super-salvo thrilled me to the very bone.

"Seventy-eight—eighty!" yelled Masters, almost in my ear. "Slow down now: First crossroad to the right!"

Reluctantly I removed my foot from the accelerator, and the big racer quieted down to a more ordinary rate of speed. The pike showed up before us a white lime-streak in the midst of fields of green, with a sparse line of poplars following its length into the distance.

"Now don't go over forty!" commanded my companion as we turned the corner. "I want to see the landscape."

He did not seem to be interested in the landscape, however, as we rushed along at the stipulated speed, but kept his gaze fastened on the roadway ahead.

"He may have escaped—I was slow," muttered Masters aloud to himself. I did not answer, but smiled grimly at the thought of our mad rush across fields and fences and the subsequent ride at race-track speed. If that were what he termed slow!

"That's where Parker lived until a month ago," commented Masters, indicating in a general way a cluster of cottages that stood near a heavy wood by the side of the pike. He has disappeared com— My God! It was Parker!" he exclaimed suddenly. "See that car?"

Far forward on the road I saw a small automobile drawn up at the side of the wood, and I slowed as we approached. Masters had drawn his revolvers and opened the fore door, ready to make a running attack. The car proved, however, to be empty.

"Stay here!" he commanded. "If he tries to get to the flivver, shoot—and shoot straight!" With that, Masters sprang from the running-board, climbed the fence and made off through the woods toward the cluster of cottages we had seen.

I felt distinct misgivings, in view of the threat that our quarry had made on Masters' life; yet I could do nothing but obey. Sliding out of my seat, I drew my revolvers and waited, facing the fence over which Masters had disappeared.

TEN passed before Masters reappeared; I had begun to get

very uneasy. Finally he came to the fence, however, and beckoned

to me. I saw that his face was set and grave.

"Another murder!" he announced when I joined him. "I am going back and run over the ground a little more thoroughly. We have plenty time to get our man now."

"But isn't he after you too?" I queried anxiously, after we had passed into the wood and were threading our way through the thick brush.

"No, I don't think so!" he responded slowly. "I think his work is done, and I don't believe he will seek me out any further."

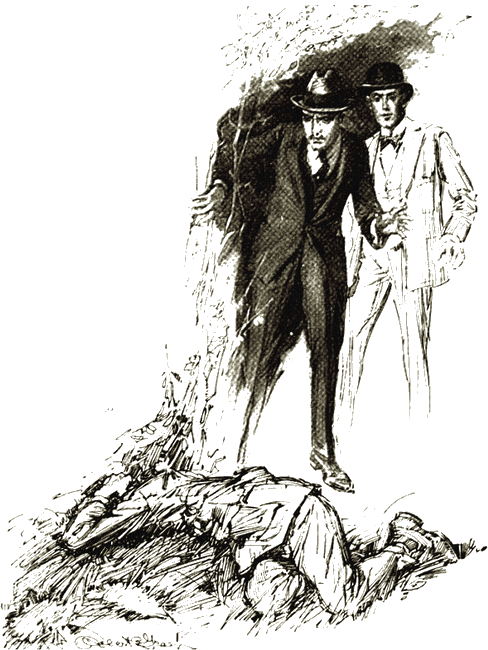

We came suddenly upon the scene of the tragedy. In a tiny glade carpeted with luxuriant grass upon which the sunlight fell checkered from the foliage overhead, lay what had once been a man. He lay crumpled up in a hideous heap on the grass, and simply saturated in his own blood. I made as if to straighten him, for I was curious to see his features, but Masters stopped me.

In a tiny glade lay what had once been a man.

"It's just the same as the other," he said. "Only this time the murderer took the head off completely!" He pointed to the shrubbery a few paces beyond. There on the broken shaft of a sapling was transfixed a hideous, severed human head, smeared with the stains of fresh blood!

I started back with a gasp of horror, for though in my adventures with Masters we had encountered many repellent sights, nothing quite so grotesque, horrible and disgusting had occurred.

"Why, the face is smiling!" I cried, overcome for the moment.

Masters made some inarticulate comment and knelt beside the body.

"Here's 'Exhibit B,'" he said, indicating a bare spot near the pool of blood.

I pulled myself together and knelt down to look. As I followed Masters' pointing finger, I felt the icy chill of fear course down my spine! I veritably believe that my hair came as near to standing on end as lies within the possibilities. Printed plainly in red on the brown of the earth was the spoor of a gigantic human foot!

"It's nearly two feet long!" I cried aghast, feeling in my veins the curdling that the sanest man feels when he rubs elbows with unexplained horror. "Surely no man alive has feet like that!"

"No, you are right!" responded Masters slowly and gravely. "And look here again!"

This time he lifted the decapitated body and showed me the neck. "This has been done by some instrument that we never have run across before," he said, pointing to the ridges in the tissues. "The head was not struck off with a knife or hatchet, for the ridges run in concentric circles around the neck!"

"A strangler!" I cried, thinking of the bands of East Indian thugs that I had read of in my boyhood days.

"Something like that," agreed Masters, "—only it looks as if the cord used was really edged steel wire. I think he used it looped like a lariat, threw it over the head of his unsuspecting victim and then proceeded in the double process of choking him and sawing off his head."

A premonitory faintness seized me; so I turned abruptly. "Who—who is the murdered man? Do you know?" I asked.

"Yes, I thought of course you knew. It's Parker."

"Parker! Then he would have been better off in jail, after all!" I flashed back one last glance at the grim scene as we started through the brush. "How did this murderer ever find out that you were after him?" I asked.

Masters smiled oddly. "I think now that the story I told Mrs. Stanwood must have had more truth in it than I imagined! I can see no other way to it than that 'S' was in the house at the time I got the notebook. He probably thought discretion the better part of valor, with others in the house, and so followed me and the notebook."

NOTHING more was said as we traversed the last rod of

brush. I kept a wary eye upon the thickets as we passed through,

more than half expecting an assailant at any moment. It was not

until we came to the road and the little car again, however, that

I made any discovery, and that was unexpected. Just as I was

going to take my seat at the wheel of the Peugeot, I chanced to

glance at the road, near the deserted machine.

"Jigger!" I broke in sharply. "Look here!" I took his arm and led him a few yards down the road to a point where the white dust lay thick on the macadam road. I pointed out to him a strange hole, about one foot in length, scratched in the dust and macadam at right angles to the road itself. Two feet in front of this a firm, staggered track began which several times in the first twenty yards became double.

"He left in a motorcycle!" I said, a little pride unconsciously creeping into my voice at my discovery. "Carried in the back of his automobile, probably."

Masters gave a low whistle. "Bert," he said, "this is an amateur criminal we are after, but he could give pointers to the best of them!"

"Shall we follow?" I queried, excited.

"Yes!" answered Masters abruptly. "There are several crossroads to watch," he said, running up to the car. "Our only clue now is the track of his new tires. I'll ride on the bumper!"

Thus we started out, with Masters holding his place by clasping the lamp-brackets, and leaning forward the better to watch the flying macadam. I drove slowly at first, and then as realization dawned upon me that our quarry could not possibly carry his cycle up the high embankments that rose on either side. I let out the Peugeot. Masters must have suffered terribly from the speed and his cramped position, but he gave no sign.

As the first cross-pike came into view, Masters held up his hand. I understood, and throttled down the car to eight miles an hour. Masters jumped to the ground and hastily examined the crossing. I heard him give a yell of exultation, and stopped.

"Down this road!" yelled Masters, and I backed and turned around. As I threw in the clutch again, he jumped into the seat beside me.

"I'm on familiar ground now," he said. "Selkirk is the first town—fourteen miles. Drive like the devil!"

AS we sped onward I reviewed the probabilities. Masters

evidently did not expect the murderer to turn again. We would

doubtless find him stopping at Selkirk. It was long past

lunch-time, and we might easily find him at the hotel.

Twenty minutes later we swung into the main street of the little town and made for the hotel. Just as we did so, a figure jumped from the piazza, mounted a red motorcycle in the street and was away like a flash.

"There! There!" cried Masters, but I needed no stimulus other than the sight of that red flash. The fever of the manhunt was thrumming through my arteries, and our giant machine never felt the spur of a more enthusiastic driver.

Selkirk gaped vacantly as we swept through at sixty miles an hour, but fast as we were going, the red streak before us was traveling still faster.

"Let her out! Let her out!" cried Masters, almost beside himself.

I gritted my teeth, clung to the wheel with all my strength, and gave her the last ounce of gas and the last notch of spark. I had no eyes for the speedometer; all I could see was the winding ribbon of road that seemed to be shot under us as from a casting reel, and the red clot far in front. The fenders began to rattle with the terrible strain, but slowly I saw the red dot coming close, closer.

It all happened in an instant. With a rush we caught up to the cycle. A goggled face turned toward us; a gauntleted hand was raised; and a bullet nicked the glass wind-shield before us. Perhaps it was the speed that had gone to my brain, or perhaps the closeness of the shot had something to do with it, but something snapped inside of me, and like the driver of an ancient Juggernaut I turned in the big Peugeot and smashed into the speeding motorcycle from behind.

I turned in the big Peugeot and smashed

into the speeding motorcycle from behind.

Metal ripped. I had a vision from the corner of my eye of a body hurtling through the air, and then I had my own hands full stopping the big car. We careened into the ditch, which luckily was shallow and grass-grown at that point. We bounded against a low fence of crossed timbers, but at that point I swerved the wheels toward the road again, and by sheer luck we managed to make it safely. Fifty yards farther on I brought the car to a stop, and Masters, revolver drawn, stepped unsteadily out.

An hundred yards back we found him—I almost said it. The collision and the force of his own speed had hurled him clear of the timber fence and far out into the plowed field. He was unconscious but still breathing when we got there.

Masters, to my surprise, held me back when I went to touch the huddled form, and handed me a pair of rough gloves.

"Put these on first!" he commanded, and though such action seemed incomprehensible to me, I obeyed.

"You'll see why!" was Masters' terse comment.

And I did! To my dying day I shall never forget the horrible sight that greeted my eyes when we straightened out the victim of my driving! The man, unconscious yet, seemed broken to a pulp. Both arms were smashed so badly that the bones were protruding through the skin, and one leg was doubled up under him.

Beside him on the ground lay two huge affairs, grotesquely resembling bare human feet, yet made to slip over shoes like a pair of rubbers. They were fashioned from solid rubber.

"The sixteen-inch feet!" I cried.

"Yes, and that's not all," said Masters, moving one of the inert arms with his toe. I looked and saw that the arms both ended at the wrists! To one was attached a clever mechanical hand, while the other ended in a strong, three-pronged hook.

His face was ghastly white, except for a purplish discoloration around the corners of the mouth and the eyelids, but the neck was tightly bandaged.

Masters bent over and thrust his hand into the side pocket of our victim's jacket. He drew it forth slowly and impressively, holding a thin steel wire about five feet in length. It was looped just as Masters had predicted, and was evidently the instrument that had caused the death of Stanwood and Parker.

"Well, you got me, didn't you. Mr. Sleuth-hound?" Masters and I jumped as if we had been detected in some illegal act. The cold black eyes were not opened widely, but there was not the slightest pretense of unconsciousness.

MASTERS' hand went for his revolver, and at that a

flicker of a smile played over the hideous features of the man on

the ground.

"Afraid of me even when my back is broken, eh? Well, I don't know as I blame you. I pretty near got you once."

"Yes, that bomb!" Masters smiled grimly.

"But I don't care now," continued the man more weakly. "I did my job up just as I wanted to do, and it had to be either you or some other cop." I saw Masters wince at the unwelcome appellation.

"I suppose you want my story before I cash in?" The two of us nodded, for there seemed not the slightest doubt that the man was passing quickly.

"My name's Shackleford—Shackleford of Tía Juana, Mexico. That was where I was born and raised…. Oh, but I'll get on; you don't care about that part. You're interested in my arms and feet, and in Stanwood and Parker, eh?

"Well, I don't care much how you play it up now, 'cause I'm going, but those weren't murders. That was justice—slow and insufficient justice, too!

"There were three of us, Stanwood, Parker and myself—that was long before Stanwood was the respected gent that lived at Cheshire Hills. We were all 'fore the mast on the tramp steamer Alexandria—a South Sea bummer. At Honolulu we all deserted.

"We had gotten hold of a Kanaka who told us some yarns about the enormous pearls we could get up near one of the smaller islands—Kauai, it was. It sounded good to us; so the three of us took advantage of the disturbed state of affairs in Honolulu—one of the tin-pan kings was just then getting deposed—and stole a small boat from the harbor, and with our friend—Bhalanoku was his name—made for Kauai. Well, we got a few pearls, just diving for them ourselves, but they were enough to make us want more. We fitted up an expedition with the money we got from them, and went back.

"Thirty-two days we worked the second time, and I guess in that time we cleaned up the whole bed. Anyway, we weren't finding any more oysters. We were ready to go back—for more than one reason: We had found out in the meantime that Bhalanoku was losing his hair and his finger-nails! You know what that means in the tropics.

"A kind of terror hit the whole bunch of us, for when leprosy gets into a camp of Chinks and Kanakas, it ain't long before all of 'em have it.

"Well, to cut it short, Stanwood and Parker beat it that night, with all the pearls, leaving me and Bhalanoku and all the others to rot there on Kauai! You see what it did to me!" Shackleford smiled grimly, and his eyes fell on his wrists.

"It was three months before I could get away from the island, and in that time I got it too. The crew we had brought with us were for killing Bhalanoku and myself, but I reasoned with them, showing them how we could make it share and share alike if we could find some more pearls. Well, we found a few more, and then we walked the shore-line until we came to Lamai, a little settlement on the west coast.

"There I left the rest of them and took a fishing schooner for Hawaii.

"I couldn't trace Stanwood and Parker, but I knew that they'd get to the States as quickly as they could; so I traded in some of my pearls for money for transportation, and came on myself."

HE smiled in ghastly fashion. "My one wish in the world

since that time has been to find Stanwood and Parker: If I'd

known how to go about it, I'd have given them the leprosy too,

but I saw I couldn't do that; so I laid my plans differently.

It's meant over twenty years of searching, but eight weeks ago I

located them. You know the rest, I guess." His voice sank

lower.

"But why did you go through all the nonsense about the huge feet?" asked Masters.

"Two reasons," came the terse answer. "Back at Kauai I used them to scare the natives with when they threatened insubordination. I knew I could scare the hick police with them. Then, I can walk better in them now," he added dryly. "You see, I don't own toes any more, and the long things keep me from stumbling. If I'd had sense enough to kill you when you were at that Stanwood place, I'd be free now. But why should I want to be free, anyway?" The voice sank lower with weakness.

"You pretty nearly did for us," vouchsafed Masters. "My friend here caught your bomb and threw it out the window just before—"

"I wish it had gone off!" snarled Shackleford with sudden venom; but then his voice trailed off in a weak cry. "There is a flask of whisky in my hip pocket—if it isn't broken. Would you—"

"Just a second!" interrupted Masters. "There are a few things I want to know first. What were Parker's relations with Stanwood, and how did you get past the dogs that night at Cheshire Hills?"

Shackleford sneered weakly. "Oh, Parker spent the gold he got for his share, while Stanwood made himself rich by good investments. I guess Parker bled him, though. The dogs? Even the young lions Stanwood kept on his place couldn't stomach me. They met me at the gate, and I thought I'd have to poison them, but they only smelled at me and backed away. They had sense. Now please, may I have the whisky?"

"How did Stanwood know you were coming?" continued Masters with apparent callousness.

"I wrote him!" gritted the prostrate victim through clenched teeth. "Please, won't you let me have the whisky?"

I waited to hear no more, for in spite of myself I pitied this horrible wreck, and wished to do as much as I could in easing his last moments. As I fished in his pocket, I thought Masters made a motion as if to stop me, but I pretended not to notice.

I uncorked the flask and held it to his lips. He drank the draught greedily; a shudder shook his mangled body, and he lay still.

"What the deuce!" I cried. "It killed him!"

Masters seized the flask. "I suspected something of the kind," he said, holding the flask gingerly to his nose, "but I couldn't see that it made much difference now. Cyanide in the whisky!"

"But if—if he were dying?" I protested. "Why should he commit suicide?"

Masters shrugged his shoulders. "There are many strong men," he remarked, "who would rather finish it than drag through unnecessary pain. It's just as well. He had played his string to a finish."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.