RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Detective Masters runs into a merciless blackmailing plot and solves a strange cipher in the course of his exciting fight against the criminals.

The Green Book Magazine, June 1918, with "The Red Billiard-Ball Mystery"

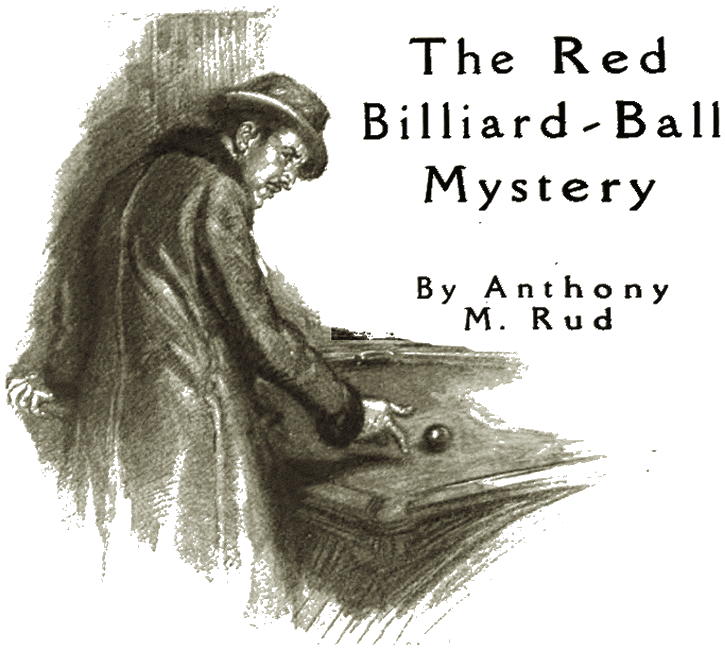

The man with the hooked nose threw the red ball about the table.

I RARELY invaded Jigger Masters' quarters. The chief reason for this was that my friend had invited me only once. I knew that he disliked company or even casual acquaintances, as a general rule, but because he had taken to dropping into my studio nearly every day, I felt that I could exempt myself from the restrictions to a certain degree.

I went because I really was becoming curious. As I said, Jigger had been dropping in to smoke a stogie with me while I painted. He would drape his long legs over the arms of one of my cane rockers and sit for an hour or so, hardly speaking a word. Usually I was busy, and I think that was why he came, for he seemed to concentrate better with another person in the room, provided that other person also was intent upon some task.

There is an urge to adventure in me, though, which lets me work only a certain period of days. Then I must go out and walk the sidewalks looking for diversion, even if it is but a mild flirtation with a little Italian girl at one of the fish-carts of Hester Street. I make romance out of little, and people pictures I am going to paint with the personalities I rub elbows with on these rambles, and so I am tolerant of my weakness.

The adventures I had enjoyed in Masters' company, however, had made these genre incidents tame in comparison. Just as long as Masters visited my studio regularly, I knew that there was nothing in the wind. But the moment I missed him, my imagination got busy, and I could see him gallivanting off on the most lurid cases, leaving me to bite the ends of my brushes in unsatiated excitement. I just had to visit him to ease my own mind.

I found him hunched over his hideous teakwood desk, with his bony elbows jammed down upon a chart of some kind. His person was in as bad disarray as his desk. The latter had a multitude of small reference-books piled about, some opened to a place, some opened and turned over, while others were just sprawled among the ash-trays, looking as if they had just fallen from the top of the unsteady heap at one corner.

Masters himself was clad in an atrocious flesh-colored fuzzy bathrobe, under which he wore the sloppy semi-attire often affected by bachelors during the hours they do not expect visitors. His wild shock of black hair was uncombed, and it had become so snarled that a pencil, poked into it, stood at an acute angle upward near his left ear.

"Glad to see you, Bert," he rumbled in a far-away tone, reaching up an aimless hand to mine without lifting his eyes. "Just the man I wanted to see! Sit down!" He leaned over and pulled up a straight-backed chair near to his own swivel seat. I obeyed silently, for I knew from the blankness of his expression that he had been intent upon some problem when I interrupted.

"There isn't any game of billiards that you play with just one ball, is there?" he queried, abandoning his concentration suddenly and wheeling about to face me.

I shook my head slowly, trying hard to think of the different pastimes I had played and seen on the green cloth. "No, I don't believe so," I answered. "The nearest to that I can name is golf-pool; that takes a cue-ball and one object-ball."

"No, this is played on a regulation billiard table. Say, Bert, if you saw a man with a cue and just one red ball, shooting earnestly away at the cushions with that one red ball, stopping his shots, trying them over, and sometimes helping them along when they do not go exactly as he desires—"

"I'd say he was practicing the use of English, or testing the cushions or just plain nutty," I broke in.

Masters nodded almost imperceptibly, but his wide mouth curved in a smile. "And if you saw him doing that same thing day after day? And if he never seemed to have any difficulty getting a 'gallery' to watch him? And if sometimes one of the 'gallery' stepped up and did the same thing for a few minutes?"

That surely was a puzzler. I hesitated. "Well, Jigger," I replied, "if I saw that myself, or some one else asked me that, I should simply recommend the services of an alienist for the crowd. However, I know that you think there must be something more back of it than just foolishness. What's the idea, anyway?"

Masters shrugged his hunched shoulders and then straightened slowly in his chair. "Well," he began quizzically, "are you looking for another chance at being knocked over the head?"

"You bet!" I don't know what it is about the man, but whenever I am in Masters' company, I would contract to attempt most anything. He inspires rashness, but confidence at the same time.

"Not cured, eh?" He smiled. "Well, that's just what this case is, a prime chance to get knocked over the head. There were many pleasant possibilities in the Tong case which you helped me on last, and this is at least as dangerous. If the Chinks had done for us, at least they would have thrown our bodies out in an alley somewhere; we would have been picked up and given decent burial. Here—well, it might be an old cistern or sewer, or most anything."

"What they do with me after I'm dead doesn't concern me!" I said shortly. "What we can do to them first is more to the point."

"Good old Bert!" exclaimed Masters. He pointed out of the window to the sidewalk below. "There comes a chap who can tell us a great deal about this case—more, possibly, than he will tell, though I don't know about that."

I followed his finger just in time to see a fat, squattily built man walk hurriedly to the doorway below.

"Giordini is his name," announced Masters as we were waiting for the elevator to bring him up. "He's a fruit-merchant—not a peddler, but a wholesale fruit-dealer. Basil Bennett sent him to me."

The visitor's appearance, even more than Masters' warnings, brought home to me the fact that the case was serious. The Italian appeared nearly numb with apprehension; yet he seemed sustained somehow by a desperate courage that was far from the blind rage I half expected to see in his face. He was built with unnecessary strength, a mission style of man whose very muscles hampered their own accomplishment. Jet-black hair, smoothed with some oil and parted so precisely that the white scalp showed through in startling comparison, emphasized the pallor of his countenance. The full lips were firm, however, and the black eyes did not waver, although they glanced questioningly from one to the other of us.

"Mr. J.M.? Which of you is he?" he asked without the trace of a Latin accent.

Masters bowed. "This is my friend and collaborator Mr. Hoffman," he said, indicating me. Giordini acknowledged the introduction with a curt nod.

"I know a little already of your case, Mr. Giordini," Masters continued, "and I have persuaded Mr. Hoffman to assist me in the investigation." I flushed a trifle at the implied compliment, but if I had been inclined to become egotistic, the doubtful glance of the Italian would have finished that.

"With you it has been a simple case of attempted blackmail, has it not?" inquired Masters.

"Yes, blackmail with a threat of my life attached," responded Giordini quietly. "Twenty thousand dollars is their price."

"And you take them seriously?"

I thought for an instant that the Italian was not going to answer at all, for Masters' half-bantering tone met a very frigid reception.

"I have good reason to know!" our visitor retorted finally, in a tone of restrained exasperation. "Do you remember Kalipoulos, the Greek?" Seeing Masters' nod of assent, Giordini continued: "He paid these men five thousand dollars first, then ten thousand the second time; the third time they asked for twenty thousand. He refused. They killed him with a bomb inside ten days!

"With me they have not been so gradual. Foolishly enough, I paid their first demand, five thousand dollars. Life is sweet—I have no other excuse. Now they ask twenty thousand. If I pay, it will then be fifty thousand, and finally they will kill me anyway. I shall go no further. I know they will get me, for I have seen six men refuse to obey; not one of the six is alive!"

"Is the band a part of the Black Hand organization?"

Giordini shook his head slowly. "No," he said.

"How do you know?" Masters' question was sharp, incisive.

The Italian sat motionless for fully ten seconds before answering. "I—I suppose there is no logical reason why I should not tell all I know," he admitted finally. "No secret is as dear as life. I know that this is not Black Hand work, because there is not, strictly speaking, any such thing a Black Hand in this country. Murderers and robbers sometimes use the signature to throw off the police, but there is no real Black Hand like in Sicily and Sardinia."

"Do you know that for over a year you have been watched as a suspect in the matter of this organization?"

The black eyebrows shot up, and Giordini licked his lips before answering. "Indeed!" he managed to articulate. He recovered composure speedily, though, and the ghost of a grim smile curved the corners of his mouth. "You learned very little, didn't you?" he asked.

Masters disregarded the question. "You are not on trial, Mr. Giordini. In fact, we are trying to save your life, and I think we can do it if you will be entirely frank with us."

Giordini nodded. "I am foolish," he said. "Once I was implicated in a criminal act with that same crowd, and I have tried to conceal it even when I knew the police knew it. I called for the money the first time from Kalipoulos; I could not help myself. Any Italian in the city would have done the same thing, for to disobey an order sent in one certain way means death—and quickly, too! I was ordered to do what I said. I was to pay the money over to a man I met in front of a certain café. I did just as I was told, and that is all I know."

"All but one thing," amended Masters. "How did you know that the order came from these men, and what do they call themselves?"

Giordini shrugged one shoulder. "I know no name," he said. "All I know is that when a man comes with a message, and that man carries in his coat pocket a red billiard-ball—well, he may be bluffing, but it is not worth while trying to find out!"

"A red billiard-ball!" exclaimed Masters, and his eyes met mine. "So that's the way they let themselves be known! Just one more thing, Mr. Giordini. Do these men always use bombs in killing their victims?"

"So far as I know. You see, a bomb is easily hidden in the clothes; it is a sure way, if you are experienced in throwing it, and it can be used in so many different ways."

"Yes, indeed, many different ways," agreed Masters. The queer dullness was creeping into his eyes. "I guess that will be all, Mr. Giordini," he said. "For the present, though, I guess you'd better keep away from your store.

"Give him a key to your studio, Bert," he commanded. "Stay up there until you hear from us."

I obeyed, and gave Giordini instructions as to how to enter the place from the rear. The Italian bowed to us both, and departed.

INSTANTLY Masters sprang to his feet. "Well, let's see how

good a pool-room bum you can make yourself in five minutes!" he

commanded. He threw open the door of a capacious closet at one

corner of the room. Clothes of all descriptions hung therein. I

selected a ragged old soft shirt and a suit of black serge which

rain and years of wear had spotted with all the hues of the

spectrum. Masters donned corduroy trousers and a flannel shirt,

tying a bandanna about his neck. He slipped two revolvers into

the pockets of his trousers and gave a pair of the weapons to

me.

"I don't think we'll need them just yet," he said grimly, "but they'll be useful before this is over."

I clasped the butts fondly. "Well, bring on the targets; I'm ready!" I answered.

Masters opened the door without a word. I followed him down into the street. "Bennett has been watching this place for months now," he went on after we had walked ten minutes in silence. "If it were merely a case of getting a few of the murderers, he could have landed them at any time—at least he could have had a dozen or so suspects; but there is a brain at the head of all this, a man really worth capturing. He knows enough of the superstitious fears of the illiterate to give them an organization bound together by secrecy and a symbol. What the red ball means I confess I don't know yet."

We had come to the edge of the great Italian district. I knew it fairly well from my many rambles in search of material, but Masters confused my sense of direction by his many turnings up streets and alleys. Our steps slowed, and Masters assumed a swaggering slouch which I endeavored to imitate.

We turned in at a pitch-dark doorway in a ramshackle building which housed, on the ground floor, a saloon. Worn stairs led upward to a landing where a sickly gas-jet gave a weak, one-sided flame.

There was another door with the inscription: Pool, 2½c a Cue. We entered. Eight or nine youths were sitting about, smoking and talking, but no one was using a table. The conversation ceased as if it had been gagged, and all of the men turned their eyes upon us.

Masters swaggered over to a table, pulled a cue from the rack and called for a set of balls in good street-Arab Italian. The man at the counter was in no hurry to give them to us; I felt his eyes burning into me. I knew that Masters, in spite of his blue eyes, might easily pass for an Italian, but I didn't look the part at all.

Finally we got our balls, however, and started playing a banging game of straight-rail billiards. Masters did not attempt to make many points, and I took his lead, purposely missing many easy shots—for the purpose of prolonging the game, I imagined.

AFTER fifteen minutes or so, the men seated about the other

side of the room resumed their conversation, this time in subdued

tones. They seemed to have lost interest in us, for now and then

they glanced at the doorway. Masters was leading in points,

thirty-five to thirty-three, when a new development occurred. A

well-dressed Italian entered.

He scrutinized us carefully, and though I saw this out of the corner of my eye, I did not dare to look straight at him. I guess he sized us up as harmless, however, for he sidled over to the waiting group and sat down. Another consultation concerning us evidently took place, for there was some whispering, but Jigger and I kept methodically on with our game. Jigger won, and then we started another.

About this time I got a good look at the newcomer. He was rather tall for an Italian, and dressed in a velours hat and a fur-collared overcoat. His nose was hooked, and above it a stubby black mustache occupied his whole upper lip.

He arose finally, and walked to the billiard-table nearest the crowd. Then he took out of his pocket a red billiard-ball! This so excited me that I miscued my next shot completely, but Jigger went on methodically. He did not seem to be watching, but I saw the queer faraway expression coming into his eyes as the man with the hooked nose threw the red ball about the table. The latter did not use a cue, but simply slammed the ball against the cushions, caught it, and threw it again, time after time.

"Make a long run now!" Jigger whispered to me as I stepped up for my turn. I did my best, but that run of thirty-one was an example of the worst cheating I ever did; four times I missed by a narrow margin but went right on as if each miss had been a carom.

The thirty-one put me out, and Jigger, with a curse, threw down his cue upon the table. He "crabbed" volubly about the luck which had won the game for me, and as we went up to pay the check, I saw that he really was excited, though not over the billiards.

THE moment we emerged on the street, Jigger turned sharply to

one side. "Do two things just as quick as you can!" he rasped.

"Call Basil Bennett and have him send a squad just as quick as he

can. I can't tell him just where, but tell him to find me

somewhere in the Italian district. Then take a taxi and go to

Giordini. Get him to give you five thousand dollars, or some sum

like that. Give him a receipt for it, and tell him he can have it

back. No, wait a minute! I'd better do that. I'll have Bennett

find you. You watch for this hook-nosed chap. When he comes out,

follow him, and don't get caught! If you wait around on the

street beside the house he goes into, Bennett will take

charge."

"But the crowd up there?" I cried. "What will they be doing?"

"You just leave them to me!" retorted Masters. "You watch old hook nose!" With that he was off, striding at a rapid rate.

DESPITE the adventure involved, I had no real hankering for

the assignment, for it seemed as if I were more or less out of

it. The real action would come when the pool-room gang was

corralled; I felt sure of it.

As time went on I grew nervous. The well-dressed Italian had not appeared, and I felt that I was becoming quite an object of interest, sauntering up and down a sidewalk crammed with foreigners. I purchased a bag of pistachio nuts and ate these.

Twenty minutes more passed before my quarry appeared. Then he strode down into the street, seemingly in a great hurry. He made his way up the sidewalk, looking to neither the right nor the left. I had to hurry also in order to keep him in sight, for he dodged in and out among the other pedestrians and up alleys and byways that reeked of Ghetto filth.

Suddenly he jumped into a doorway, and I stopped, at a loss whether to follow him or just to watch the house as Jigger had told me. The latter course did not seem extremely profitable, for the house was a wooden tenement, probably honeycombed with corridors leading to entrances far beyond my sight.

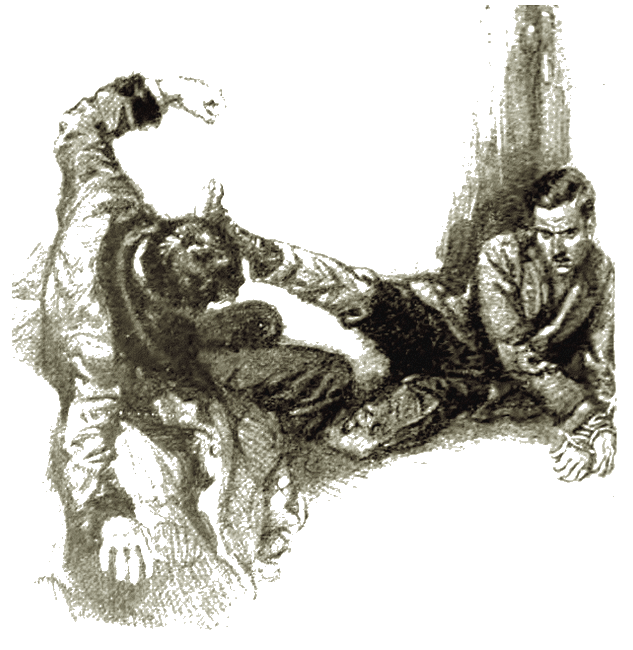

The matter was decided for me, however. Before even I had time to turn around, two men hit me from behind and threw rather than pushed me through the same doorway that Hook-nose had used. Something heavy descended on my head, and then ensued a period of semi-consciousness in which I felt dimly that I was being carried up a long flight of stairs.

I do not believe it could have been more than five or ten minutes before I opened my eyes, but when I did, I found myself in a different world, a world that no one could dream existed from the unpromising exterior of the tenement. Rich rugs covered polished hardwood floors: divans of wicker held velours pillows which I envied; and there were soft floor- and table-lamps of the same shade of old rose as the rugs and the velours. Tobacco-smoke, rich as incense and too pungent for the eyes, filled the air.

My first distinct sensation was of this smarting. I opened my eyes, to look squarely into the face of the hook-nosed chap I had followed. The moment he saw I was awake, he gave a sharp order in Italian, and two men lifted me, propping me against the door. They crossed my wrists, binding them together with oiled rope, and fastening the knot to a bracket on the door which seemed set for just such a purpose.

All was quick and businesslike. When the two had finished, they departed immediately, leaving me to face my quarry, who now had become my captor.

"Well, what did you want of me?" Hook-nose seated himself on the edge of a divan near to me as he spoke. His voice was not unpleasant, but it rang with a steely quality that I did not like just then.

I was too slow in answering to suit him. "Answer!" he growled abruptly, frowning. "Who was with you, and what did you want?"

"I was alone," I said, uncomfortably conscious that it would be hard to lie convincingly to this man. "I am a painter, Albert Hoffman by name, with a studio—"

"Never mind that!" my auditor exclaimed. "I just want to know before I kill you, why you followed me."

"But I am trying to tell you," I persisted. "I was walking along the street looking for a male model, when I saw you disappear into that pool-room. I waited for you and then followed you, but you went so fast that I—"

"Lies! All lies!" Hook-nose interrupted, motioning me to stop. "You were up in that pool-room when I got there! I saw you. What were you doing there?"

I was silent, for when it comes to inventing a plausible story under pressure, I am worse than useless.

Hook-nose drew his revolver. "I shall probably kill you anyway," he said indifferently, "but if in five minutes you have not made up your mind to tell me all about that tall companion of yours—well, you'll not have to think any longer." He took out a thick-cased gold watch and snapped it open.

FOR the first minute I strained vainly at my wrist bonds. The

oiled rope was sound, however, and I could not make it give half

an inch.

"One minute!" announced Hook-nose.

A sudden idea came to me. My legs were not tied. During the time I had spent in Paris I had picked up a little of savate, and had learned not to despise the shoe as a weapon in rough-and-tumble fighting. I measured the distance away Hook-nose's face was as he looked at his watch, and then strained at my bonds to see if I could gain a little in a horizontal direction. To my dismay I saw that my enemy was just too far away! If I tried I should certainly miss him, and then all would be over.

Seconds were precious. I could not seem to think. In despair I allowed myself to sink forward, bowing my head and bending my knees. It was a poor imitation of a fainting-spell, but it had just the result I desired. Hook-nose saw me wavering, and leaned forward about five inches to see better whether or not I was shamming. That very instant I raised my foot in a swift upward kick. My shoe-toe caught Hook-nose an inch or so back of the point of the jaw, and the bones crunched like sticks of rotten wood. He dropped back in a lump upon the divan, and I knew he never would trouble me again.

My shoe-toe caught Hook-nose an inch or so back of the point of the jaw.

That was but half the problem, however. I still was tied tightly, and at least two more of the gang were near at hand, probably in the next room. How could I release myself?

After ten minutes of struggling I found the solution. The tips of the fingers of my right hand would just reach the opening of my left hip pocket. This was the pocket in which I usually carried my matches and my handkerchief. The handkerchief, of course, was useless—but the matches!

Madly I pulled and worked at the lining of the pocket with my finger-tips, and at last I grasped the box of safety matches! Cold sweat started on my forehead once, for I nearly dropped the box, trying to open it. I succeeded, however, and lighted a match. It then was but the work of a few moments to burn through the rope which held me.

I jumped to the side of Hook-nose and searched him rapidly. An automatic was my reward. And I found it not an instant too soon, either, for while I still was stooping over, the door, burst open and two of the chaps I had seen in the pool-room rushed at me.

I wheeled and let the first one have it from the automatic, but he hit me head on nevertheless, falling to the floor, but at the same time covering up the revolver until the second had grappled with me.

He pushed me back over the body of Hook-nose until in desperation I gave way completely, rolling to the floor. He came with me, but before he could seize my trigger-hand again, I had finished him.

Not knowing whether or not more were coming, I leaped up and latched the door. Then I listened, but there was not a sound in the whole building, so far as I could tell.

I walked to a telephone and called up the station. "Can you get hold of Basil Bennett right away?" I demanded. "This is J.M. talking!" I was in no mood to quibble about exact truths just then.

"Yes!" came the excited answer. "He's been looking for you for half an hour. Where are you?"

"I—I—" I stopped; for the first time I realized that I had not the faintest idea where to tell Bennett to come. "I don't— Oh, yes!" I shouted "Tell him to come to telephone number 48920-J. He'll know where that is!"

Then came a terrible period of waiting, not over ten minutes, I suppose, but intolerable to me because I got to thinking of what had happened to Jigger Masters in the intervening time. He had had a harder assignment even than mine—at least I know he thought so when he sent me after Hook-nose.

I passed a few minutes looking over the men I had overcome. I had little or no sympathy for them; if I had not got them, they would have killed me. However, one of my last assailants was not dead, the chap who had been first in the rush through the door. He was moaning in pain, so I did what little I could to stanch the blood which was pouring from his wound and make him easy. The bullet had plowed through his chest, and I knew he had not long to live—so I did not make any attempt to bring him to consciousness.

At that moment I heard a familiar whistle outside, and glancing from the window, I saw the flash of blue uniforms. At the same time came the tramp of heavy feet in the corridor outside.

"This way, Bennett!" I yelled, throwing open the door.

A squad of policemen entered. I pointed out the bodies of the three men to a sergeant, and then ran out to look for Chief Bennett himself. I found him just entering the house.

"Jigger Masters?" I said, my lips barely moving.

"Why, no! Isn't he here? I thought that the phone-call—"

I WAITED to hear no more. I raced back to the room in which I

had left the squad of twenty, and then without even waiting for

Bennett's permission, I ordered them all to follow me. "J.M. is

in trouble!" I cried. "Come with me!"

A dozen or so of them really did come, and the whole squad of us set forth on a dog-trot. The events of the past half-hour had so fogged my brain that I was by no means sure of my whereabouts. I dodged up alleys and down streets, the police at my heels, seeking always for some familiar landmark to guide me back to the pool-room.

Through sheer luck, I guess, more than sense, I headed straight for it. Without wasting a second in reconnoitering, I sent two of the police to the back of the building, bade two remain in front and led the rest up the narrow flight of stairs, past the one-sided gas-jet.

When we walked into the pool-room, a strange sight met my eyes. Huddled about the same billiard-table was most of the group I had seen there previously. The part that made my hair stand right straight on end was the fact that in the center, watched by a score of hostile eyes, Jigger Masters was performing with a red billiard-ball!

Watched by a score of eyes, Jigger Masters

was performing with a red billiard-ball!

The police all drew their weapons, and a resounding order to surrender was bellowed forth; but the gang had other ideas. Masters alone raised his hands and retreated to the wall. Every other man dodged for the shelter of a pool- or billiard-table, and then ensued one of the nastiest fights I ever took part in.

I got two of the men before my automatic refused to work, and then, just as I was trying hastily to reload, a stray bullet nipped me just above the knee.

It was all over a second or two later, however. The police had only two live captives, and both of these were wounded. Three policemen lay on the floor, while several others nursed slight wounds like my own. I joined Jigger Masters, who had sat down grimly and disgustedly in one of the wall chairs.

"Well, you got here just about in time again, Bert," he said in greeting. "It would have served me jolly well right if you'd never come, though. I've messed up this case worse than Bennett himself could have done!"

"Why, what's wrong?" I asked innocently. "Haven't you got the whole bunch here?"

"Here!" he echoed ironically. "Yes, I feel very happy about that! Any hick policeman could have done that much any time within the last six months! The chap I was after, though, was that bird with the hooked nose, Costello! That was the first time I ever saw him here; usually he sends a messenger instead of coming himself. And now!" His deep voice held worlds of self-condemnation.

I could not keep the secret any longer; so I related my part of the action, even to the fight in the tenement. When I told him that Costello was dead, he rose up solemnly and took off his hat. "Bert," he said, "you're a gem! You have saved me from— Oh, thunder, I wish I knew some way so that you would get all the credit for this, old man!"

"Never mind that!" I said brusquely, for if there is anything in the world I would hate to be, it is a newspaper hero. "Just find me a bandage to put on this little cut of mine, and then tell me all about your part of it."

Masters did so, cutting up a handkerchief and tying it about the tear. Then he helped me down to a taxi.

On the way back to his apartment I had time to question him.

"Oh, my part was easy," he said. "I foozled it badly, though. I intended that Basil Bennett should find you and surround the house or tenement that was used for headquarters for the gang; and then about the time that part of it was concluded, I would have the rest of the gang walk right into the trap. Bennett tried to carry out his part, but was prevented by your disappearance. I intended to get Giordini to carry up a sum of money to that gang in the poolroom—"

"Why, for heaven's sake?" I queried, for this part I had been supposed to perform at first had seemed cryptic to me.

"So that I could make a clean roundup of the whole gang at once," replied Masters. "At least, that was my idea. I thought that if the money was paid to those men, they would go in a body to Costello, in order each to get his share. It didn't work, though, because Giordini absolutely refused to take the chance involved."

"Tell me what all that red-ball foolishness was about, then," I interrupted. "What were you doing when I found you—I mean when the police broke in?"

"I was just telling them a few lies," responded my friend sheepishly. "I was telling them, by means of the red ball, that Giordini had paid in his twenty thousand, and that if everybody wanted his share, he should go right up and see Costello."

"Telling them by means of the red ball?" I echoed.

"Oh, yes! I forgot that you didn't know. All that shooting at the cushions, and throwing the ball about, was a cipher! The men were talking by means of a cushion alphabet!"

I waited in wonderment, for it was far from clear to me yet.

"You see," continued Masters, "while you were beating me at billiards, I figured out the cipher. Giordini's statement that all messages were accompanied by a red billiard-ball gave me the clue. I thought immediately of a message when I saw them throwing it about. I managed to solve it while you were making your phony run of thirty-one points.

"It really was simple—or I guess it became simple after a little practice. The left-side cushion was numbered one, the far end-rail two and the right-side cushion three, while the near end-rail counted four. The letters of the alphabet were numbered from one to twenty-six. All you had to do was to add the numbers of the cushions hit in any one shot, take that letter and then continue shooting till you had finished the message."

"Good land!" I exclaimed. "That sounds intricate to me!"

"It is, when you try it," Masters admitted. "I would have been successful except I made too many mistakes. I was too confident; those chaps—probably because of years doing it—reeled off the shots so easily that I thought I could do it right away. Well, I guess it was lucky you came over to my apartment this morning, Bert! I wouldn't have lasted more than ten minutes longer!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.