RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a Victorian print

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a Victorian print

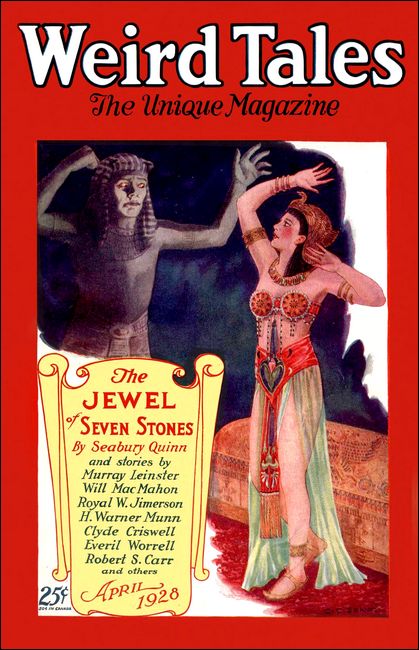

Weird Tales, April 1928, with "The Spectral Lover"

BARNEY came back to me last night! Something aroused me from my sleep. And when I opened my eyes I saw Barney at the foot of the bed. I could not see him clearly, but Just a vague outline, through which the furniture showed distinctly. He was like a filmy vapor which seemed to grow a trifle denser. Then he disappeared.

I had not slept well. The news of Barney's death had shaken me. Although I did not love him, I think I liked him. Perhaps it was his overbearing mastery which held me. He would command, and I seemed unable to refuse. Time and again I vowed to myself to break with him. I scolded myself for being his slave. But as soon as he appeared, my will-power was gone. It made me afraid of him, terribly afraid.

"You've got to be true to me," he often said. "If anything happens to me I'll come back for you."

That made me shudder. "But, Barney," I would reply, "I don't love you. You know that. I—I—like you, but not—not—like that."

Then he looked at me with those stern and piercing eyes and repeated: "You belong to me, Nell. What I have I hold. And if anything happens to me I'll come for you. Remember that! I'll come back for you!" And when he spoke like that and looked at me so compellingly, my resistance just seemed to evaporate.

I'd have no thought of my own, only that he meant what he said and would carry out his promise.

This morning, as I write this, all seems a ridiculous dream. How could there be spirits? Or, if so, how could a spirit have power over flesh and blood? No, I will not think about the matter. Barney's words meant nothing; they are futile. Why should I feel troubled?

Of course, that he was killed makes me feel somewhat sorry for him. But I could not mourn him. I don't foci that I lost someone dear to me. If anything, I feel rather relieved that he is gone.

Wednesday.—He came again last night. What does it mean? This time his image was a trifle more definite.

Thursday.—Barney was more distinct last night. I couldn't sleep after that.

They noticed something at school today. That is, they noticed I didn't feel well. The principal called me in. "Miss Martin." she said kindly, "I'm afraid you're ill. Yon look very tired. Better go home. I'll manage to have someone take your pupils today and tomorrow. You go home and rest well over the week-end so that you can come back Monday feeling perfectly fit. Perhaps it might be well for you to see a doctor."

I cried a little and could barely thank her. Mother was surprised to see me home in the middle of the morning. She doesn't understand. I couldn't explain to her. I'm afraid I couldn't explain to anybody.

Friday.—Barney spoke to me last night. "I've come for you, Nellie," he said.

I was terrified and hid myself under the covers. But I could see him right through the blankets and counterpane. He was beckoning me.

I shook my head at him. I shivered all over, but I couldn't say a word. My throat seemed paralyzed.

Oh, what is the matter with me? Here I am supposed to rest—that's what the principal excused me for—but I haven't slept a wink the last two nights, and I am restive and nervous. Yet, whenever I lie down for a moment, Barney's image seems to stand before me; I see his threatening—no, commanding—eyes; I seem to feel him urging me, calling, compelling.

Ah! It isn't fair! Barney, could you really have loved me? Then why do you wish to destroy me?

Saturday.—Barney struggled with me in the night. I could nearly feel him, as if he were real. He seemed substantial, although I knew all the while that he was only a disembodied spirit. But how strong! And what terrible will-power! He was all will. And I fought him. Oh, I feel so weak! I seem to lack all strength to live—and I do not want to die!

Ah, Barney! You wanted me to be true to you, though I never promised that! Did you really love me? Is it the way of true love to take the life of that which it cherishes?

Sunday.—I made up my mind that I would say "No!" very definitely to Barney. Today I feel as if an evil spirit has visited me. I have read of vampires—how they steal up on their victims at night, and suck the blood and with it all the life-giving strength. After such an experience the victim must feel somewhat as I feel today—listless, enervated, altogether broken.

Barney spoke to me. "You must come, Nellie. It's better if you come willingly. If you don't it will be the worse for you. My will is greater than yours. You know that."

"No, I will not go," I answered. "I don't want to go. I don't want to go with you, Barney. I never loved you. You—you have—have terrified me."

So I spoke my refusal. But it was all in vain. His eyes seemed to bore into mine, two terrible magnets which pulled and pulled, and against which I fought weakly. It was horrible! I shudder when I think of it. I could feel my strength, the little I had left, oozing out of me. I felt as if I were being dissipated into thin air just as a tenuous vapor disappears under a gentle breeze. I wanted to pray, but had not even will enough to form a single word.

I must have fainted. For when I awoke it was broad day and Mother told me she had been calling me for horn's. She chided me. "A regular sleepy goose." If Mother only knew!

Monday, February 21.—Mrs. Martin called me in this afternoon to see her daughter, a school teacher. The girl was supposed to return to her work today, but her mother had been unable to wake her.

Examination showed a weak and irregular pulse. I gave her an injection of adrenalin. Miss Martin is a very pretty girl, although at the moment her face appeared drawn, with a somewhat haunted look. Her weight seemed normal, skin color rather good. No signs of digestive or other disturbance.

While I made an examination, Mrs. Martin busied herself at Nellie's little writing-desk, and there she found her daughter's memoranda of her experiences. I have copied them into my diary; they constitute an astonishing' record.

The injection seemed to improve the cardiac rhythm, but I was unable to rouse the girl. This fact, together with what I read in her journal, prompted me to have her transferred to the hospital.

Tuesday, February 22.—Brent, the intern, came to me with an astonishing tale. And yet not so astonishing in view of what I already knew.

It seems that the nurse called him to Miss Martin's room during the night to administer a sedative. Miss Martin had sat up and talked wildly, pleading with someone named Barney. "Asked him to let her live, and the like!" said the nurse.

"Darned puzzling case, Doctor," Brent offered. "Nurse nearly climbed out of her boots in fright. Said it wasn't the usual fever talk of patients but something quite different. Well, Number 24 is still asleep. Gave her a big dose." With that he went away, whistling shrilly.

Too bad there is a hiatus in Nellie's account! It would be of interest and help a lot to read in her own words what she experienced Sunday and Monday nights.

-The laboratory technician's results were now available and I proceeded to study these. Nothing indicative! If anything, they were the results one might expect from a normal person. Certainly nothing physically wrong. To check up matters once more I went to her room to question her. She was still asleep, her reflexes low and indefinite, altogether lethargic.

After a careful examination I looked for Father Ryan, the venerable hospital chaplain. As usual, I found him surrounded by a number of nurses who were jesting and putting catch-questions to him. I just heard one of them ask, "How long should a woman's skirts be, Father?"

"Above two feet," was his prompt answer.

I drew him away from the laughing group. "Look here, Father Ryan," I said. "I know you're something of a soul specialist. You priests Warn a lot more than physicians of the kinks and quirks that make up the human animal."

He gave me a sidelong glance. "All of which means?"

"I have a peculiar case on hand which puzzles me completely. It's a mental case; of that I am positive! I think you could help me. Only, she's not a Catholic and—"

"If she's a good Protestant," he interrupted, with a twinkle in his eyes, "she's probably a better Catholic than many Catholics I know of. But tell me about her before I see her."

I took him to the office and showed him the memoranda she had written. "That's the sum and substance of it all," I remarked after he had read the lines. "I ought to add that last night she nearly—well, the attending nurse saw nothing herself, but Miss Martin spoke to whatever she saw. Nurse said she thought her patient would die. Got a good bit frightened herself."

"Hm! You've examined her?"

"Physically? Yes. Blood count O.K. No fever. Normal in every respect, except strength. Hang it! Looks as if that ghost or spirit or whatever-it-is is trying to absorb her—as if it were trying to suck the life from her body. She's frightfully weak. Little vitality, and virtually no resistance. Yet nothing really the matter with her."

"Ah! This Barney—Dr—what's-his-name?—Barney Lapeere—how was he killed?"

"Humph! He was killed by—himself. He really committed suicide. Jumped from the top of a building. They kept that part from her."

"And do you happen to know why he ended himself?"

"Not particularly. There was a rumor that it was about a woman."

"Oh! Are you sure about that?"

"No. In fact, I do not recall who told me about the matter. But—hm, let me inquire among the nurses! A hospital, you know, hears all the scandal that never gets into the papers."

"To be sure," he smiled. "The scandal that not even the papers dare to print." He paused thoughtfully. "Will you try to find out all you can about the man, Doctor? Particularly about this—Dr—scandal you mentioned."

"Oh," I said in surprise. "Do you see some relation?"

"Not that exactly, Doctor. What I am looking for is some connection I can break. Offhand it looks like an autohypnosis, I should say. If we can break in on that, it may be that we can save her. Well, you try, Doctor. I'll drop in to visit her. But whether you find anything or not, I think I'll spend the night at her bedside."

"Good!" I remarked. "And I think I'll be there also. I'll have Brent, the intern, circulate among the nurses and then see you with the budget he collects. And if I pick up anything myself during the day I'll let you know of it. Adios!"

Wednesday, February 23.—An operation and a series of office and outside calls kept me busy till late. So it was near midnight when I returned to the hospital, fin-mediately I made for Miss Martin's room. Father Ryan sat beside the bed watching the girl; somewhat farther, near the door, sat two nurses.

"How is the—?" I began to ask. But the priest made a warning gesture and placed his finger across his lips.

I tiptoed over to the bed to look at the girl. She was exceedingly pale, the pallor emphasized by the very black hair. Her lips were moving slightly, although she uttered no sound.

A questioning glance at the chaplain. "Her lips started moving just before you dropped in," he whispered. "But see!" He pointed to the girl.

Between faintly moving lips came a very small voice. "You have come for me, Barney?" it breathed, the tones barely audible, yet the words distinct.

A pause. And then, "Must I come?"

I was watching her carefully, yet was conscious that Father Ryan had got up and was now peering intently at her features. As I watched, the face took on a paler shade—a colder hue, one might say.

Again a murmur, "I am coming," and she seemed to rouse herself.

It is difficult to describe that moment. I could swear that she lay there absolutely motionless. Yet I got the impression that she had gathered herself as if to leave the bed. There was no visible movement, yet I felt action. I sensed struggle, without being able to perceive any physical evidence of it.

It was then that the priest spoke. "Stop, Nellie!" he cried sharply, his glance fixed on her closed eyes. And with careful syllabification, "You—must—not—go! Barney—was—not—true—to—you! Barney—killed—himself!"

Nellie lay motionless, her face quiet, her lips no longer moving. In a quicker cadence, but still stressing every syllable, the priest resumed. "Barney Lapeere demanded your faith, Nellie, but broke his own for another woman. Nellie, do you hear me? Barney—Lapeere—killed—himself—over —another—woman!"

And then he seized her hands and began to draw her gently but steadily into a seated position. "Come, Nellie!" he said. "You are alive! You are well!"

There was a faint sigh, a flush mounted to her cheeks, and her eyes fluttered open. But it was not surprise that showed in her glance—it was anger!

"Oh! The coward! The abominable wretch!" she whispered.

"It is true, Nellie," said the chaplain. "He has gone now."

This was an assertion, and the girl did not contradict it.

"You will live, child. Go to sleep now. You must rest a lot. It was a cruel experience that you have survived, but it is past and you will live. Remember that."

As he spoke she fell back to her pillows and gazed at the priest with surprise, which slowly turned into an expression of childlike trust. She smiled gently, her eyes closed, and she began to breathe deeply and regularly.

"Better give her food," said the chaplain to the nurse. "Lots of food—milk with eggs, and the like. I think she'll take the food, even while asleep."

I nodded my assent to the directions, and the nurses left for the kitchen. Meanwhile I drew the priest aside and asked him, "Look here, Father Ryan, you might tell me exactly what's what. No bed for you till you've explained!"

"Very well. Has it ever occurred to you that people die because they have lost interest in life?"

"Of course. Every physician knows that."

"Well, if people can live because they have an interest in life, why can't a person die because said person has an interest in death?"

"Oh!"

"But Nellie had no real interest in death, you must admit. That was clear from what she w-rote. She thought she had; but if I could prove to her that it was not a true interest, then she would not think of dying—at least, not dying as yet. Such thoughts are all very well for an old war-horse like myself, but hardly proper for a lively and healthy young creature."

"You are talking in abstract terms, Father Ryan," I scolded. "Kindly get down to concrete facts."

"Very well, very well. In this case it was a dead person that seemed to compel her interest. So I destroyed that interest and gave her life."

"I see that. But how?"

"If you please, Doctor! Let me follow my own reasoning. Offhand one might say it was a clear case of autohypnosis. But I am not so sure of that. Whence came her interest in dying? It was not natural with her. For she explicitly states over and over that she did not love the man, that she did not want to follow him, that she did not want to die. Hence that interest did not originate within her, but was supplied by some extraneous source. Her memoranda make clearly evident what that source was: it was Barney Lapeere."

"Of course. Then your method was to overcome Barney's influence by proving that he was unfaithful."

"Not quite that. Let me tell you something about Barney. Your man Brent is something of a genius. He managed to compile quite a bibliography in a few hours. This Lapeere was undoubtedly a hypnotic person. More than one person remarked the influence of his glance, especially on women. For a young man (he was only twenty-three) he had a remarkably long list of escapades, unsavory or savory, as you look at it." Here the chaplain smiled wryly. "The last months, while he was ostensibly courting Nellie, he had an affair which turned out rather bad. Instead of facing things, he committed suicide. Most of these Don Juans have a yellow streak. They have courage to make love, and that is all."

"Quite true. But admitting that," I urged, "what bearing—?"

"Pshaw," the chaplain interrupted. "Don't you see it yet? The man worked on her fear. It's a case where one will supplanted another or at least dominated it completely. Nellie was aware of that much herself. Also, there was post-hypnotic suggestion, only till now I had never thought that it could last after the death of the hypnotist. But here—well, it was fear that he worked on. She was afraid of him; that's clear from her notes. Men die of fear. What can one expect in a woman who has been half-hypnotized, whose will has been constantly sapped, and into whose mind a pernicious idea has been implanted? Here it was the idea of coming for her: she feared just that. And he seems deliberately to have emphasized that over and over, as if consciously or unconsciously, he were preparing for a gruesome experiment. It was this dominating influence, strong in life, and just as strong or stronger in death, that I had to break down. That's what I gathered from the data given by Brent and by Nellie herself."

"I see. Given a hypnosis, how can it be broken?"

"Yes. It meant that I had to find some way of attacking him. Here is my logic: A decent girl admires two virtues in men, courage and loyalty—loyalty to others and courage to face the consequences of an act. She did not love him. She protested that over and over. Still, she felt his power, but only because she considered him an honorable man. Like most of us, she believed that strength of will is based on tumor.' Hence, show her that the man was dishonorable, and his control over her would be gone. They should have told her the truth when he killed himself. All this would not have happened."

"I agree with you there. Father Ryan," I said. "So your method then was to arouse her jealousy?"

"Her what?" he demanded, as if astonished. "I thought you had seen deeper than that. Doctor. You seem to be thinking of the well-known fact that every woman, even the best of them, likes to believe that she is admired for herself alone, and that the professed admiration is restricted to herself. At any rate, she will feel kindly toward the admirer. That's one of your ideas, isn't it? The second is that of the 'woman scorned.' Oh, I know you men! Someone once got off a sonorous line that 'hell hath no fury like a woman scorned,' and since then this funny humanity believes that it must be true for every woman, first and last. If an admirer turns on a woman she will hate him. Bah! Hence you infer that I called Nellie's attention to Barney's disloyalty in order to arouse the jealousy that supposedly is never very deep beneath the surface of any woman."

"Well, isn't that exactly what you did?"

"Oh, the conceit of these men! And you, too, Doctor! There were two things I said to her: that Barney had killed himself and that he was not true to her. The other woman never bothered her. The fact was that she realized that he had been dishonorable, and further that he was a coward, and therefore had neither courage nor loyalty. My words directed her full attention on Barney. She did not think of herself at all, only of Barney; that is, what, the truth did to Barney's image. Before then it was a picture of strength, of power, which she feared, but respected. The other and true image is that of a cowardly weakling, strong only in pursuing women, and in nothing else. An idol deflated; what longer should she fear? The moment that sank into her consciousness, that moment the hypnosis was ended. With the destruction of fear, she was free—and well!"

"Hm, you may be right," I remarked.

"Of course I am right. Think it over. It was the fear of Barney I attacked, of Barney as a powerful but honorable man. Jealousy had nothing to do with it. She feared him, remember that. And there you are!"

With that I left him and went back to the patient. I found her sleeping soundly, her pulse strong and regular, a delicate flush on her cheeks. Hm! Maybe the priest was right. And, in his words, there you are!

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.